Abstract

Photoacoustic imaging is a promising modality with potentially broad applications. To achieve high-quality images, an appropriate detection technique suitable for the specific application is crucial. This review categorizes detection technologies into two primary methods: ultrasonic transducers and optical sensing. We present their detection principles and recent progress, from conventional to advanced technologies. We finally conclude by providing a detailed classification, outlining the main characteristics of each technique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been a growing demand for comprehensive information about living organisms, ranging from anatomical structures to physiological functions, in both medical diagnosis and research. For these purposes, imaging technology has become an essential tool1. Many conventional imaging technologies, such as X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT), positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), optical imaging (OI), and ultrasound imaging (US), have reached significant performance milestones in terms of imaging speed, resolution, penetration depth, contrast, and sensitivity2. But despite these advancements, fundamental technical limitations of each technology remain. X-ray CT and PET rely on ionizing radiation, which can have potential adverse effects on patients. MRI systems are too large and costly, and the imaging and data processing take a significant amount of time, limiting their widespread or repeated use3,4,5. In the case of OI, light propagation is limited by scattering, resulting in shallow penetration depth and rapidly degrading spatial resolution as the axial depth increases6,7,8. US generally has lower spatial resolution than other imaging modalities, and there is a tradeoff between imaging depth and resolution, which complicates its application. In this context, photoacoustic imaging (PAI), a hybrid imaging modality combining OI and US9, is in an unrivaled position, as it compensates some of the drawbacks of conventional imaging modalities. PAI is a cost-effective, non-invasive, non-ionizing, and agent-free imaging method that can be employed in a wide range of applications without significant restrictions. Moreover, PAI offers the combined advantages of OI and US, achieving high-quality in-vivo images with optical absorption contrast and acoustic spatial resolution1,10,11,12,13,14.

PAI relies on the photoacoustic (PA) effect, which occurs when a short laser pulse is applied to chromophores. The absorbed light energy causes rapid thermo-elastic expansion, and the chromophores contract as heat diffuses during the laser off-time. The laser pulse induces repeated expansion and contraction of the chromophores, leading to the generation of ultrasound (US) waves that reflect the optical and structural characteristics of the target. The initial pressure of the PA wave is determined by the following equation:

where Γ represents the Grüneisen parameter, ηth represents the photothermal conversion efficiency, μa represents the optical absorption coefficient, and F represents the optical fluence15,16. By detecting differences in absorption by biomolecules (e.g., hemoglobin, lipid, and melanin) at selected laser wavelengths, PAI can easily distinguish these molecules. As a result, PAI can, for example, obtain structural information about blood vessels, such as vessel morphology (e.g., vasculature) and blood flowmetry (e.g., blood flow velocity), from the signal of hemoglobin17,18,19,20,21. Furthermore, by extracting the concentration of various chromophores through multi-wavelength laser excitation, PAI can provide label-free functional information (e.g., oxygen saturation, metabolic rates)10,22,23,24. This multiparametric capability has made PAI an essential tool for the complex diagnosis and monitoring of various diseases.

A typical PAI system consists of several key components: an optical source, an acoustic detector, and a data acquisition system (DAQ)25. The optical source provides the necessary optical excitation to generate PA signals, and the beam from the optical source can be shaped for each specific application using optical systems such as focusing lenses or diffusers1. The generated PA waves are converted into electrical signals by various detection methods, and the DAQ processes these signals into usable data. The acquired and digitalized PA signals are subsequently reconstructed into images through image reconstruction algorithms (e.g., delay-and-sum algorithm, Fourier beamforming, etc.). Depending on the application, factors such as the illumination method, the generated signal, and the required image specifications (e.g., resolution, contrast, sensitivity, field-of-view, signal-to-noise ratio, etc.), and system requirements can vary significantly. Consequently, selecting an appropriate detection method to efficiently capture signals is crucial in constructing a PAI system, as it directly impacts the quality of the resulting images. The frequency spectrum of the acoustic wave generated by the PA effect is broadband, and varies according to the structural distribution of the target26. Since undetected portions of the signal can lead to information loss and distortion, achieving broadband detection is a critical aspect of PA detection. In addition, the primary range for practical image reconstruction falls within the US band of MHz frequencies, making medium coupling for efficient energy transfer and impedance matching a key consideration in implementing a PAI system.

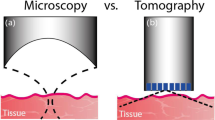

Considering these factors, various PA detection methods have been researched, and this review will discuss them in detail, categorizing them into specific groups (Fig. 1c). We begin with piezoelectric TRs, which convert the mechanical energy of waves into electrical energy and are commonly used in general PAI systems27. Piezoelectric transducers (TRs) can function as a single element to obtain high-resolution images of small regions28,29, or as multi-element arrays to simultaneously capture signals from larger areas. In addition, we explore advanced TR types like piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers (PMUTs), which combine microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology with conventional piezoelectric TRs30,31,32,33,34, and capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers (CMUTs), which detect changes in capacitance caused by the vibration of a flexible membrane35. These advanced TRs offer improved performance with customizable sizes and shapes. We also cover studies that integrate TRs with recently developed technologies such as transparent TRs, flexible array TRs, row-column array TRs. These innovations aim to overcome the limitations of conventional TRs and enhance performance. In contrast to TRs, optical sensing detects PA signals by sensing changes in an optical system induced by acoustic pressure. Optical sensing can sensitively detect broadband signals without the constraints of medium coupling, enabling more precise imaging of microbiological structures. Optical sensing, including Fabry-Perot interferometers, microring resonators, plano-concave resonators, and remote sensing, are discussed with an emphasis on their detection mechanisms and recent applications. Finally, we conclude by providing a comprehensive classification of advancements in PA detection techniques, by organizing the detectable bandwidth, application or imaging targets, and key features of all the detection methods discussed in the review.

Single-element transducer. Reprinted from Hu et al.134 with permission from Elsevier. Reprinted from The Lancet with permission from Elsevier. Multi-elements transducer. Reprinted from Choi et al.79. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. PMUT. Reprinted from Cai et al.83. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. CMUT. Reprinted from Chan et al.135. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. Recent advanced TRs. Reprinted from Park et al.97. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License. Reprinted from Wong et al.103 with permission from Elsevier. Reprinted from The Lancet with permission from Elsevier. Fabry-Perot interferometer. Reprinted from Plumb et al.109. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. Microring resonator. Reprinted from Lee et al.120. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. Remote sensing. Reprinted from Hajireza et al.125. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. Plano-concave resonator. Reprinted from Lewis-Thompson et al.124. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. PMUT piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer, CMUT capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer, TR transducer. Conventional transducer, advanced transducer, and optical sensing. The images are adapted with permission from refs. 79,83,97,103,109,120,124,125,134,135.

Ultrasonic transducer detection

Conventional piezoelectric transducer

Conventional piezoelectric transducers (TRs) are widely used to detect PA signals. Piezoelectric TRs are devices that convert electrical signals into mechanical vibrations and vice versa, relying on the piezoelectric effect27, which is the ability to generate an electric charge in response to mechanical stress. Common piezoelectric materials used in US TRs include polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), lead zirconate titanate (PZT), lead titanate (PbTiO3), and lead magnesium niobate-lead titanate (PMN-PT)36,37,38. Because piezoelectric TRs can function as both transmitters and receivers of US waves, they are suitable for use in both US and PA imaging27,36.

PA studies using conventional piezoelectric TRs can be broadly categorized based on whether they employ single-element or multi-element TRs, depending on their specific purposes. Single-element piezoelectric TRs are typically used in photoacoustic microscopy (PAM), which focuses on high-resolution imaging of relatively small and superficial regions28,29. PAM achieves this by scanning a focused laser beam across biological tissue and detecting the generated PA signals with a single-element TR. The A-line signal acquired by the single element is then used to reconstruct a wide-field image, typically through scanning methods such as MEMS, galvanometers, polygon mirrors, or voice coils39,40,41,42. This approach allows for detailed visualization of microvasculature41,43,44,45,46,47, sub-cellular and cellular structures48,49,50,51, and superficial tissues52,53,54,55. PAM is particularly advantageous for visualizing fine details within a small area due to its high spatial resolution. Further, PAM can be classified into optical-resolution PAM (OR-PAM) and acoustic-resolution PAM depending on whether the system relies on the optical or acoustic focusing. OR-PAM relies on tightly focused optical excitation, providing much finer lateral resolution determined by the focused light size. AR-PAM employs acoustic focusing, which allows for deeper tissue imaging beyond the optical diffusion limit. Acoustic focusing enhances the sensitivity of PAM at deeper structures. On the other hand, multi-element piezoelectric TRs are commonly employed in photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT), where they capture PA signals from larger areas simultaneously. Multi-element TRs acquire PA signals from multiple angles simultaneously and then reconstruct volumetric images using reconstruction algorithms, such as filtered back-projection, time reversal, delay-and-sum, iterative reconstruction, or model-based approaches56,57,58,59,60,61. PACT provides a broader field-of-view (FOV), faster acquisition time, and deeper images beyond the optical diffusion limit, making it highly valuable in preclinical and clinical research. This capability is particularly important for the comprehensive visualization of larger anatomical structures, such as entire organs, and for diagnosing and monitoring the progression of diseases9,11,29,62,63,64,65,66,67,68.

Single-element piezoelectric TRs vary significantly based on their center frequency, which affects spatial resolution and penetration depth29,69,70. Generally, higher center frequencies could offer better spatial resolution but shallower image depth, making them suitable for imaging superficial tissues with finer structures. Conversely, lower center frequencies penetrate deeper into tissues but with lower resolution, making them suitable for deep tissue imaging. High-frequency acoustic waves attenuate rapidly within biological tissues, leading to variations in imaging depth. Also, the lateral resolution and axial resolution of PAM images is derived as follow equations29:

where \({R}_{L,{AR}}\) represents lateral resolution of AR-PAM, \({R}_{L,{OR}}\) represents the lateral resolution of OR-PAM, \({R}_{A}\) represents the axial resolution of both type of PAM, \({v}_{A}\) represents the speed of sound, \(N{A}_{A}\) represents the numerical aperture of the TR, \({f}_{c}\) represents the central frequency of the waves, \({\lambda }_{O}\) represents optical wavelength, \(N{A}_{O}\) represents optical numerical aperture, and \(\Delta {f}_{A}\) is the detection bandwidth of TR. The lateral resolution of AR-PAM is inversely proportional to the center frequency of the detection while the axial resolution is inversely proportional to the bandwidth. The bandwidth is closely related to the center frequency, with higher center frequency TR generally providing a wide bandwidth and thus improved axial resolution. Also, acoustic attenuation in biological tissue can be basically represented by the equation71,72:

where \(A\left(d\right)\) represents the amplitude of the wave at depth d, \({A}_{0}\) is the initial amplitude, and α is the attenuation coefficient. The relationship between attenuation and frequency is given by:

where f represents the frequency of the acoustic wave, and n is a parameter that depends on the tissue characteristics.

Based on these equations, higher frequencies generally improve spatial resolution but attenuate more rapidly, limiting the imaging depth. Depending on the center frequency, a single-element TR can obtain high-resolution images of superficial structures or penetrate deeper into tissues to visualize deeper anatomies. Song et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of deep reflection-mode PA imaging using a 5-MHz spherically focused TR, achieving a penetration depth of 38 mm in chicken breast tissue73. The study successfully observed deep organs such as the spleen and stomach of rats noninvasively. Jeon et al. observed major blood vessels and internal organs through multiscale PAI by switching between 5- and 40-MHz TRs70. The study compared the vasculature in the back regions of rats using two different center frequencies (Fig. 2a). They verified that the 5-MHz TR provided greater penetration depth (10.3 mm), but lower lateral resolution (590 μm) compared to the 40-MHz TR, which offered higher resolution (85 μm) but shallower depth (3.1 mm). By alternating between the 5- and 40-MHz TRs, they successfully obtained whole-body images of small animals, visualizing deep organ structures (Fig. 2b). Kim et al. used a 50-MHz TR to achieve high-resolution PAI of microvasculature in small animals and humans without any exogenous contrast agents41. The PAM system further improved spatial resolution by localizing PA signals from red blood cells, enhancing the lateral resolution to 0.4 to 0.7 μm and axial resolution to 2.5 μm. This super-resolution localization PAM allowed for detailed observation of the microvasculature in small animals (Fig. 2c) and human fingers (Fig. 2d). Aguirre et al. utilized ultra-broadband (10–180 MHz) mesoscopy using a lithium niobate crystal (LiNbO3) TR. They achieved the detailed structural images of the dermis and sub-dermis in psoriasis, assessing the inflammation through label-free imaging69.

a Depth-encoded vasculature images of rat back using 5 MHz and 40 MHz transducers. b Whole-body left sagittal images of a mouse. Reprinted with permission from Springer Nature. Reprinted from Jeon et al.70. c MAP image of mouse ear using super-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. d MAP image of the human finger. Reprinted from Kim et al.41. Available under a CC-BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. MAP Maximum amplitude projection, 1 descending aorta, 2 kidney, 3 spleen, 4 intercostal vessels, 5 cranial mesenteric vessels, 6 femoral vessels, 7 cephalic vessels, 8 brachial vessels, 9 liver, 10 cecum, 11 lateral marginal vessels, 12 popliteal vessels, 13 mammalian vessels.

Multi-element TRs provide a larger FOV and faster imaging speed, facilitating the various preclinical and clinical applications. Linear arrays, consisting of elements arranged in a line, have been commonly used in clinical settings because they are widely employed in conventional US imaging in hospitals (Fig. 3a)74. Linear arrays are particularly effective in multimodal imaging systems that combine PA and US imaging, offering enhanced diagnostic capabilities by providing both structural and functional information. Choi et al. employed a 128-element linear array TR to acquire 3-D PAUS imaging of human feet64. The study achieved high-resolution imaging of the foot’s vasculature, bones, and skin. This multimodal PAUS imaging successfully provided both morphologic and physiological information, including quantitative analysis of vessel density, vessel depth, hemoglobin concentration, and oxygen saturation. The PAUS imaging also successfully provided high-resolution multiparametric imaging of various human body parts, including the neck, wrist, thigh, and instep, with blood vessel anatomies including carotid artery, internal jugular vein, radial artery, and great saphenous vein (Fig. 3b)63,74.

a Clinical PAUS system and a schematic of the handheld scanner. b PAUS imaging at various parts of a human body. Reprinted from Lee et al.74. Available under a CC-BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Schematic of the high-speed 3D PACT system using arc-shaped TR array. d Angiogram of the human breast, side-view MAP (bottom), and cross section images (right). Reprinted from Lin et al.77. Available under a CC-BY 4.0 License. TR ultrasound transducer, FB fiber bundle, CCA common carotid artery, IJV internal jugular vein, RA radial artery, GSV great saphenous vein, SF saphenous fascia, SCM sternocleidomastoid muscle, MF muscular fascia, DAQ data acquisition module.

However, linear array TRs have an inherent limitation, known as the limited-view effect, which arises due to the omnidirectional nature of PA signals11. To overcome this limitation, curved array TRs, including arc-shaped, ring-shaped, and hemispherical arrays, have been developed75,76. These curved arrays minimize signal acquisition loss due to the limited view and achieve optimal image quality. Lin et al. developed a high-speed 3D PACT system using an arc-shaped TR array. The system utilized four 256-element arc-shaped arrays with a center frequency of 2.25 MHz, enabling volumetric imaging with high spatial resolution and deep penetration (Fig. 3c)77. They successfully acquired in-vivo PA images of rat brain vasculature and human breast tissue (Fig. 3d), demonstrating a maximum imaging depth of up to 4 cm for human breast imaging. Merčep et al. presented a hybrid transmission-reflection PAUS imaging platform using a 512-element ring-shaped array TR with 5-MHz center frequency78. They achieved full-view cross-sectional tomography which provides complementary morphological and functional information from co-registered multimodal images, combining PACT, reflection-mode US, and transmission-mode US images. (Fig. 4a, b). In transverse cross-section images, deep organs such as the spleen, aorta, kidney, cecum, pancreas, and liver were clearly visualized along the image plane. They enhanced the image quality by applying the heterogenous speed of sound in water and inside the mouse body, based on estimations from transmission-mode US.

a Hybrid transmission-reflection PAUS whole-body images of a mouse. b Schematic of the hybrid transmission-reflection PAUS imaging system. Reprinted from Merčep et al.78. Available under a CC-BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Schematic of the PAI system using a 1024-element hemispherical array and multiparametric imaging of a tumor. Reprinted from Kim et al.80. Available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. d Depth-encoded rat whole-body image. Reprinted from Choi et al.79. Available under a CC-BY 4.0. e Schematic of spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography using a 512-element spherical array. f Visualization of whole-body pharmacokinetics and the distribution of individual gold nanorods. OA optoacoustic, RUCT reflection ultrasound-computed tomography, TUCT transmission ultrasound-computed tomography, SoS speed of sound, AA acoustic attenuation, 1 sternum, 2 heart, 3 mesenteric artery, 4 liver, 5 spleen, 6 cecum, 7 small intestine, 8 large intestine, 9 popliteal vessel, BV blood vessel. The images are adapted with permission from refs. 78,79,80,81,82. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

Furthermore, several studies have utilized hemispherical array TRs to volumetrically capture PA signals, achieving high-quality images of small animals. Kim et al. employed a 1024-element hemispherical array with a central frequency of 2.02 MHz, capturing dynamic whole-body structural and functional images of living animals (Fig. 4c)79,80. The system achieved a FOV of 12.8 mm × 12.8 mm × 12.8 mm and an isotropic spatial resolution of 380 μm, which facilitates various preclinical analyses such as morphologic and physiological monitoring, pharmacokinetics, and tumor imaging (Fig. 4d)80. Kalve et al. reported spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography (SVOT) using a 512-element spherical TR array with a 7-MHz center frequency (Fig. 4e), achieving real-time 3D PAI with an isotropic spatial resolution of 90 μm and high imaging speed (less than 2 s for a whole-body scan)81,82. The spherical array tracked the kinetics in murine organs. They visualized whole-body pharmacokinetics and the distribution of individual gold nanorods (AuNRs) coated with poly(ethylene glycol) (AuNRP), individual AuNRs encapsulated in micelles, and clusters of AuNRs within micelles (Fig. 4f). The study achieved real-time tracking of nanoparticles at the sub-organ level using spherical TR arrays.

Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer (PMUT)

PMUTs represent an advanced type of piezoelectric TRs that utilize microelectromechanical system (MEMS) technology. Unlike conventional piezoelectric TRs, PMUTs are based on thin piezoelectric film membranes, which offers reduced size, enhanced bandwidth and sensitivity, lower power consumption, and effective acoustic matching, and potential flexibility30,31,32,33,34. The piezoelectric membrane of a PMUT is sandwiched between two electrodes, facilitating the conversion between electric fields and mechanical vibrations. Notably, MEMS-based fabrication process enables the miniaturization of PMUTs, allowing highly compact and integrated US arrays. Cai et al. presented an aluminum nitride-based PMUT array (Fig. 5a)83. The study demonstrated that the high-order resonance modes provide a higher central frequency and wider bandwidth compared to their fundamental mode, which improves the PAI resolution. They performed in-vivo imaging on human finger joints, demonstrating that the system could distinguish vessels at different depths (Fig. 5b). Dangi et al. presented a 65-element linear PMUT array with a first mode resonance between 6 and 8 MHz84. The array acquired a broad PA signal with approximately 89% bandwidth, successfully obtaining B-mode images of pencil lead targets within 8-mm thick chicken breast tissue through linear scanning.

a Cross-sectional view (top) and top view (bottom) schematic of the structure of PMUT. b PAI of a human hand using PMUT. Comparison of the PA images between their fundamental modes. FB frequency band. The images are adapted with permission from ref. 83.

Capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer (CMUT)

The CMUT was first introduced in the 1990s to meet the demand for airborne US TRs capable of operating in the MHz frequency range, where traditional piezoelectric TRs exhibit poor performance85,86. The application of CMUTs was subsequently explored for use in immersion scenarios, highlighting their potential for a broader bandwidth in fluid media87. A single-element CMUT unit consists of tens or hundreds of CMUT cells. Each CMUT cell can be considered a parallel plate capacitor, consisting of a metalized flexible membrane (serving as the top electrode) suspended above a fixed silicon substrate (serving as the bottom electrode), with a cavity between them. In transmit mode, a large DC voltage along with a small AC voltage are applied to the electrodes. This alternating voltage causes the flexible top layer to displace, generating acoustic waves in the surrounding medium. The large DC bias helps to linearize the displacement response to the applied voltage. In receive mode, acoustic pressure modulates the displacement of the flexible membrane while a DC bias voltage is applied to the electrodes. This change in displacement alters the capacitance, inducing a current flow and thereby transducing acoustic energy into electrical energy88.

CMUTs offer several advantages over traditional piezoelectric TRs. Fabricated using photolithography and MEMS techniques, CMUTs can be easily crafted into various geometries and sizes, even for high operating frequencies. This versatility has spurred extensive research into their use in PA endoscopy. Nikoozadeh et al. integrated a phased CMUT array catheter (24 elements, 10-MHz center frequency) with an optical fiber ring catheter for intracardiac US and PA imaging89. The TR had an active aperture of 1.5 mm × 1.1 mm and dimensions of 1.7 mm × 1.3 mm, with the optical fiber having an outer diameter of 8 mm. This dual-modal imaging capability was demonstrated in a wire phantom and mouse kidney tumor models in vivo. Nikoozadeh et al. also developed an integrated ring CMUT array for endoscopic US and PA imaging90. The array is composed of 512-element quadruple concentric rings, and each ring had different center frequencies of 16, 12, 8, and 6.5 MHz. Its volumetric imaging capability was demonstrated using nylon wire and metal spring phantoms. Kothapalli et al. reported in vivo transrectal US and PA imaging of human prostates (n = 20), including 10 cases with intravenous administration of the FDA-approved contrast agent, indocyanine green (ICG)91. A house-made CMUT array (linear, 64 elements, 5 MHz center frequency, 0.2 mm pitch, 4 mm height, 6-dB fractional bandwidth of 80%) was used to integrate the ultrasonic array with an optical fiber bundle in a compact size (Fig. 6a). Intrinsic and extrinsic molecular PA contrasts were visualized in the range of 3–4 cm in in vivo human prostate (Fig. 6b).

a Schematics and photographs of TRUSPA imaging of human prostate with scale bar 23 mm. b In vivo multimodal PET, MRI, TRUS, and TRUSPA imaging of the prostate in a patient with PCa. From refs. 91,94,95. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. c The multi-aperture CMUT array imaging setup and the human plaque tissue sample. d Simulation results on a plaque phantom. Reprinted with permission from Gholampour et al.94. e Coherent compounding results for the imaging configuration based on three (top row), seven (middle row), and fifteen (bottom row) transducers for conventional transmission schemes (left column), S-sequence encoding (middle column), and Hadamard encoding (right column). Reprinted from Gholampour et al.91,94,95 with permission from Elsevier. Reprinted from The Lancet with permission from Elsevier. CMUT capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer, TRUSPA transrectal ultrasound and photoacoustic, P prostate, PCB printed circuit board, PDMS polydimethylsiloxane, ASICs application-specific integrated circuits, R rectum, RW rectal wall, B bladder, AFS anterior fibromuscular stroma, PCa prostate cancer.

CMUT technology offers significant advantages in fabrication, producing high element-count arrays at a low cost. Vaithilingam et al. utilized a 16 × 16 CMUT array (3.48 MHz center frequency, 93.4% fractional bandwidth) to achieve a 64 × 64-element aperture by mechanical scanning and captured 3D US and PA images of tubes filled with ICG and pig blood, embedded in chicken breast tissue92. Gholampour et al. recently proposed a multi-aperture PA imaging technique aimed at enhancing imaging resolution, contrast, and FOV. Their design featured three modules of CMUT arrays placed on a flexible substrate, with open windows in between for light delivery (Fig. 6c). Each CMUT module contained 94 elements and operated at a center frequency of 7.8 MHz. In silico and in vitro studies demonstrated significant improvements in the generalized contrast-to-noise ratio (gCNR) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) on a plaque-mimicking phantom with porcine blood inclusion93. They further evaluated the multi-aperture CMUT array on ex vivo human carotid plaque samples (Fig. 6d)94, proposing an encoding scheme that enhances the SNR without sacrificing the framerate (Fig. 6e)95.

Recent advances in ultrasound transducers

Traditional US TRs are typically opaque, which has led to challenges in integrating PA light sources and acoustic detectors, resulting in lower SNR and bulky probe sizes. To address this, recent research has focused on developing optically transparent US TRs that allow for co-aligned optical and acoustic axes, simplifying and enhancing the integration process. Both piezoelectric material- and CMUT-based TRs have been reported as optically transparent TRs. Chen et al. developed a high-frequency TR with a central frequency of 36.9 MHz and a −6 dB fractional bandwidth of 33.9%, achieving 80–90% optical transmission in the visible to near-infrared (NIR) range. This was accomplished using an LiNbO3 single-crystal piezoelectric material coated with indium-tin-oxide (ITO) electrodes96. Park et al. designed a spherically focused TR having dual center frequencies of 7.5 MHz and 31.5 MHz and >70% transparency in the visible and the NIR ranges. This design utilized LiNbO3, silver nanowires, parylene coating, and nonconductive epoxy for the transparent piezoelectric layer, electrodes, matching layer, and backing layer, respectively97. This configuration enabled through-illumination via the transparent TR, facilitating quadruple fusion imaging of US, PA, fluorescence, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) with inherent co-registration (Fig. 7a, b). Ilkhechi et al. presented transparent linear arrays using CMUT technology with photosensitive benzocyclobutene (BCB) serving as both a structural and adhesive layer, ITO as a conductive substrate, and silicon nitride as a membrane (Fig. 7c)98. They fabricated 64- and 128-element arrays operating at 8 MHz with 70% transparency in the visible range and 90% in the NIR range. Through-array illumination showed significant SNR improvements compared to off-axis illumination of gold wire phantoms, demonstrating real-time imaging capability at higher SNR.

a Schematic of a quadruple fusion imaging system using a TUT. b In vivo quadruple fusion imaging of rat’s eyes before and after alkali burns. Reprinted from Park et al.97,98,100,103,106. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Images of a transparent CMUT array with 64 channels. Reprinted with permission from refs. 97,98,100,103,106. d Photographs of a flexible transparent CMUT array and ex vivo photoacoustic tomography. Reprinted with permission from ref. 101. e Operating principle of row-column arrays. Reprinted from Wong et al.97,98,100,103,106 with permission from Elsevier. Reprinted from The Lancet with permission from Elsevier. f 3D reconstruction of crossed wires in a scattering medium using identity-encoding and Hadamard-bias encoding. Reprinted with permission from refs. 97,98,100,103,106 © Optical Society of America. TUT transparent ultrasound transducer, USI ultrasound imaging, OCT optical coherence tomography, FLI fluorescence imaging, PC personal computer, RF radio frequency, M mirror, FM flipping mirror, ND neutral density filter, C collimator, CorL correction lens, MAP maximum amplitude projection, CNV corneal neovascularization, CMUT capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer, PCB printed circuit board.

Flexible array TRs have emerged as a promising solution for developing body-conformal or wearable PA imaging devices. Roy et al. fabricated a 50-element flexible array using a PZT-based piezoelectric material coupled with a flexible epoxy-based matching layer. This setup demonstrated dual-modal US and PA imaging capabilities in phantoms99. Zhang et al. presented PA images of concave-shaped phantoms with various curvature and ex vivo bovine liver using a flexible array TR100. Ghavami et al. reported on a flexible and transparent CMUT array with a center frequency of 3.5 MHz, an 80% fractional bandwidth, and a maximum transparency of 67% in the visible range. The array was capable of being bent to a radius-of-curvature of nearly 5 mm. Through-transmission and conformal PA tomography were performed on wire targets and an ex vivo chicken breast phantom with an embedded tube filled with bovine blood (Fig. 7d)101.

Row-column arrays have recently drawn much attention for their potential to provide 3D imaging with 2D arrays while considerably reducing costs related to the number of elements and channels. Instead of having an N×N-element 2D array with N2 fully-populated channels, row-column arrays have N top electrodes in rows and N bottom electrodes in columns, allowing N×N elements to be fully addressed with only N transmit/receive and N bias channels (Fig. 7e)102,103. Zemp et al. applied row-column CMUT arrays for PA imaging and introduced bias-encoding to enhance the SNR104,105. They mechanically scanned a 7 × 7 mm die, comprising 40 rows and 40 columns, to effectively achieve an 82 × 82-element aperture. The SNR improvement reached about 3.9 times in a human hair phantom. Ceroici et al. presented 3D PA imaging using a 64 × 64-element row-column array with only 128 channels, minimizing the usual channel count106. By leveraging the bias polarity-dependent phase sensitivity of the array, Hadamard encoding enabled a substantial SNR enhancement from 8.8 dB to 25.3 dB in a wire phantom without compromising imaging speed (Fig. 7f).

Optical sensing

PAI based on conventional TRs has a limited bandwidth, dictated by their center frequency, which restricts the use of generated PA information, adversely affecting the quality of the reconstructed image. Conventional TRs are typically optically opaque, which introduces the misalignment between light-illumination and PA-detection pathways, resulting in low sensitivity and SNRs. Furthermore, they require a coupling medium, such as water or US gel, to facilitate efficient PA-wave transmission from the imaging target to the TR. The optical opacity of conventional TRs necessitates a significant gap between the imaging target surface and the detection surface to accommodate the laser illumination path. This configuration leads to an increased thickness of the coupling medium layer, which can introduce additional acoustic attenuation and potentially degrade image quality.

To address these challenges, the adoption of optical sensing techniques has been proposed107. Optical sensing can obtain broadband signals with higher sensitivity and configure the miniaturized geometry taking advantage of optical transparency. These merits potentially enhance both the versatility and the quality of PA imaging.

Fabry-Perot interferometer

One of the prominent optical sensing techniques in PA imaging is the Fabry-Perot (FP) interferometer-based system. The FP sensor operates by exploiting the interference of light between two parallel mirrors to measure changes in optical path length. When an acoustic wave changes the distance between these mirrors, it results in a shift in the interference pattern, which can be precisely detected. This change reflects the acoustic variations induced by the PA effect, allowing the sensor to effectively capture these signals. This approach offers higher sensitivity and a broader bandwidth with optical transparency, enhancing the imaging quality and process.

FP-based PAI systems offer the advantage of providing volumetric structural and functional imaging of superficial microvasculature with high spatial resolution108. Plumb et al. demonstrated that the FP sensor could rapidly visualize peripheral arteries and microvascular responses to thermal stimuli (Fig. 8a)109. The system was capable of producing detailed images within a 14 × 14 × 14-mm volume within 90 s (Fig. 8b)109. Their study observed significant differences in vascular signals before and after thermal stimulation, demonstrating the system’s sensitivity to vasomotor changes. Czuchnowski et al. integrated adaptive optics into a FP-based PAI system to enhance sensitivity (Fig. 8c)110. By correcting optical aberrations using a deformable mirror, the system achieved up to a 3.5-fold increase in PA-signal detection.

a Schematic of a Fabry-Perot sensor-based PA imaging system. b PA and US 2D images and the corresponding PA MIP images of peripheral limb arteries. Reprinted with permission from ref. 109. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Comparison of PA MIP images between adaptive-optics On and Off. Reprinted with permission from Czuchnowski et al.110, with permission from Elsevier. d Schematic of the total-internal-reflection-based Fabry-Perot (TIR-FP) sensor. e Comparison of PA signals between SPR, PMMA-, and PDMS-based TIR-FPs. Reprinted with permission from ref. 111. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. f Schematic of the dual-modality PA endoscope. g PA 3D images of ex-vivo abdominal organs. Reprinted from Rehman et al.112. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. PA photoacoustic, US ultrasound, MIP maximum intensity projection, MAP maximum amplitude projection. The images are adapted with permission from refs. 109,110,111,112.

To enhance sensitivity and bandwidth, significant developments have been made in the fabrication of FP sensors. Jiang et al. have advanced FP sensor design by minimizing acoustic impedance mismatch and enhancing sensitivity by using a total-internal-reflection (TIR) mechanism at the spacer/water interface (Fig. 8d)111. The TIR-FP sensor employs flexible polymer spacers such as polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), which have acoustic impedances closer to that of water. The PMMA-based TIR-FP sensor achieved a bandwidth of 110 MHz, while the PDMS-based structure provided a bandwidth of 75 MHz (Fig. 8e).

Ansari et al. recently developed a forward-viewing endoscope by utilizing a FP sensor and achieved wide detection bandwidth and high acoustic sensitivity (Fig. 8f)112. The FP sensor, operating within 1500–1600 nm, enables clear imaging of vascular structures through optical scanning via a miniature MEMS mirror. The endoscope demonstrated its effectiveness in PAT and white light imaging of phantoms and ex-vivo mouse abdominal organs, offering high-resolution 3D imaging capabilities (Fig. 8g). This dual-modality approach not only enhances the visual inspection of tissue surfaces but also reveals detailed subsurface vascular anatomy, making it highly suitable for guiding laparoscopic surgeries and other interventional procedures.

Fiber Bragg grating sensor

A fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensor, taking advantages of compact size and electromagnetic immunity, has emerged as another promising optical sensing technique for PAI113. An FBG is a type of optical fiber in which the refractive index of the fiber core changes periodically, allowing it to reflect specific wavelengths of light selectively while transmitting others107. When PA waves induce strain in the fiber, a shift in the reflected wavelength occurs. Measuring this shift precisely allows for the detection of PA signals with high sensitivity and broad bandwidth. Furthermore, by incorporating a π-phase variation at the center of the Bragg grating, a highly reflective mirror-like structure within the grating is created, effectively forming a Fabry-Perot cavity-like structure114. The π-phase-shifted FBGs leverage optical resonance-enhanced readout, significantly improving their performance in PAI applications115.

Liang et al. developed a miniature high-resolution PA endoscope (PAE) for gastrointestinal imaging utilizing the FBG-based sensor (Fig. 9a)116. The 125-μm diameter sensor achieved high sensitivity with a noise-equivalent pressure density (NEPD) of 1.6 mPa Hz−1/2. This PAE system, having a 7.4-μm spatial resolution with a 2-mm endoscope size, demonstrated the ability to monitor detailed vascular structures and related metabolic information of rectal acute inflammation through sO2 changes (Fig. 9b).

a Schematic of the FBG-based photoacoustic endoscopy. b In-vivo PA sO2 images of a rat rectum during acute inflammation (baseline and 90 min. after inflammation induction). Reprinted with permission from ref. 116. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Schematic of the silicon-photonics acoustic detector and photograph of the silicon-photonics chip and the assembled sensor. d Schematic of PA imaging setup. e The PA MAP image of in-vivo mouse ear. Reprinted with permission from117. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. f Schematic of a EER sensor including fabrication steps. g Schematic of PA imaging setup. Reprinted with permission from ref. 118. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. h The 3D PA image of ex-vivo mouse ear. i Photograph of the PDMS-encapsulated microfiber US sensor. j Photograph, PA MAP, and PA 2D images of the mouse brain. Reprinted with permission from ref. 119. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. FBG fiber Bragg grating, PA photoacoustic, sO2 oxygen saturation, MAP maximum amplitude projection, EER Bragg grating-embedded etalon resonator. The images are adapted with permission from refs. 116,117,118,119.

Hazan et al. presented a silicon-photonics acoustic detector (SPADE) for high-resolution based on a π-phase-shifted FBGs in a silicon waveguide coated with PDMS (Fig. 9c)117. The SPADE with a NEPD of 2.2 mPa Hz−1/2 and a bandwidth of 200 MHz performed in-vivo high-resolution PA microtomography with a 25-μm spatial resolution (Fig. 9d, e).

La et al. developed a Bragg grating-embedded etalon resonator (EER), which achieved a wide bandwidth of 160 MHz and a 10.1-μm aperture size118. The etalon structure could replace the millimeter-length Bragg reflectors with a less 100-μm length reflector, which enhances PA-detection sensitivity (Fig. 9f, g). Figure 9h shows the wide bandwidth ex-vivo vascular structure of the mouse ear with a 14-μm lateral and 8.5-μm axial resolution.

Ma et al. developed a transparent microfiber FP sensor with a needle-shaped (Fig. 9i)119. The microfiber sensor sandwiched by a pair of high-reflectivity FBGs forms an inline fiber US-sensitive FP cavity, offering both high flexibility and optical transparency. In in-vivo studies, the sensor successfully imaged vasculature in a mouse ear and brain structures, demonstrating its capability for high-resolution and non-invasive imaging (Fig. 9j).

Microring resonator

Following the advancements in FP interferometer and Bragg grating-based PA systems, microring resonator (MRR) sensors have emerged as another promising optical sensing technique for PAI. MRR sensors operate based on the principle of optical resonance within a microring structure. When acoustic waves interact with the microring, they either modulate its refractive index or change its physical dimensions. This modulation shifts the resonance conditions of the microring, resulting in a detectable change in the output optical signal. This method allows for the precise and sensitive detection of PA signals, making MRR sensors highly suitable for high-resolution and real-time imaging applications. MRR-based PAI systems have successfully imaged microvascular structures, providing detailed insights into blood flow dynamics and vascular structures (Fig. 10a)120. Figure 10b shows ex-vivo images of a mouse brain and in-vivo images of a mouse ear and a tadpole, obtained with a transmission-mode MRR-based PAI with a detection bandwidth of 23 MHz121.

a Schematic of the MRR and MRR-based PA-signal detection. Reprinted with permission from ref. 120. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. b PA MAP images of ex-vivo brain and in-vivo mouse ear. Reprinted with permission from ref. 121. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. c Schematic of a US-sensing chronic cranial window. d PA MAP images of cortical vasculature over a 28-day-period. Reprinted with permission from ref. 122. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. e Schematic of a PA catheter based on a plano-concave resonator. f The PA image of esophageal tissue. Reprinted from Lewis-Thompson et al.124. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. MRR microring resonator, PA photoacoustic, US ultrasound, MAP maximum amplitude projection. The images are adapted with permission from refs. 120,121,122,124.

Li et al. developed a disposable US-sensing chronic cranial window (usCCW) by integrating a transparent MRR122. This novel system was surgically implanted into a mouse skull and provides detailed visualization of vascular structures for PA brain monitoring (Fig. 10c). For about a month, they conducted longitudinal monitoring of the cortical vascular network. Additionally, Fig. 10d shows the observed development of hemorrhage and the growth of new blood vessels.

Plano-concave resonator

Plano-concave resonators have emerged as a valuable optical sensing method that utilizes the resonance of a microcavity for imaging applications. Guggenheim et al. developed a sensing method using a plano-concave optical microresonator123. The sensor was constructed with a polymer microcavity encapsulated within a polymer layer, which detects pressure-induced shifts in the resonant frequency. The plano-concave resonator, with a bandwidth of 49 MHz, captured high-contrast in-vivo images of a mouse ear.

Recently, Lewis-Thompson et al. developed a PA catheter based on a plano-concave resonator, offering a non-contact solution for rapid esophageal imaging (Fig. 10e)124. This all-optical US (OpUS) catheter features a plano-concave resonator for US detection and an optical fiber-based transmitter. Achieving US pressures exceeding 1 MPa and a −6 dB bandwidth greater than 20 MHz, the catheter delivers axial and lateral resolutions of approximately 45 µm and 120 µm, respectively. This system was successfully tested on the esophageal wall of a swine model, where it clearly delineated different tissue layers (Fig. 10f). The high sensitivity and broad bandwidth of the OpUS system make it ideal for detailed tissue imaging, enhancing its potential utility for real-time, in vivo diagnostics during minimally invasive procedures .

Remote sensing

Although the challenges associated with coupling media and limited bandwidth detection have been overcome using optical sensing with FP or MRR sensors, these methods still require that a sensor be attached directly to the imaging sample. The development of non-contact PA sensing utilizing optics is underway to address these limitations.

A PA remote sensing (PARS) method has been developed to eliminate the need for physical contact with the imaging target125,126. This technique detects PA signals via a low-coherence probe beam that measures changes in intensity reflectivity, rather than phase modulations. It captures the elasto-optical refractive index changes induced by PA initial pressure transients. Figure 11a shows the system configuration, where a continuous diode laser with a short coherence length interrogates the reflected light from the sample using a spot co-focused with the PA-excitation beam. The PARS technique also demonstrated its ability to measure in-vivo oxygen saturation by implementing real-time functional imaging using stimulated Raman scattering (Fig. 11b)127.

a Schematic of photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy (PARS). Reprinted with permission from ref. 125. Available under a CC BY 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. b PA MAP image and functional images of an in-vivo mouse ear. Reprinted with permission from ref. 127. © Optical Society of America. c Comparison between UV-PARS and H&E histogram images. Reprinted with permission from refs. 128,130. © 2019 Optical Society of America under the terms of the OSA Open Access Publishing Agreement. d PARS and PARSE images of a porcine bronchus. e H&E histogram image of the porcine bronchus and comparison of the signal amplitudes of PARS and PARSE. Reprinted with permission from ref. 133. © Optical Society of America. PA photoacoustic, MAP maximum amplitude projection, UV ultraviolet, US ultrasound, PARSE PARS elastography. The images are adapted with permission from125,127,128,130,133.

As previously discussed in the conventional PAM section, ultraviolet (UV)-PAM continues to produce advanced results comparable to histopathology, which involves extensive preparation steps such as fixing, sectioning, and staining. However, UV-PAM still requires the use of a medium such as water, which can potentially damage or contaminate live tissue samples. In contrast, UV-PARS microscopy has emerged as a promising alternative, providing histological information through a non-contact method128,129,130,131. It achieved a lateral resolution of approximately 0.7 μm and high SNRs, on par with traditional histological methods (Fig. 11c). Recently, Cikaluk et al. developed a rapid UV-PARS system using a voice-coil stage to effectively scan large sections of fresh tissue, further advancing the potential viability of UV-PARS microscopy in clinical settings132.

Recent advancements in PARS technology has led to the development of PARS elastography (PARSE) (Fig. 11d)133. This novel technique leverages the non-contact, non-interferometric nature of PARS to measure the mechanical properties of tissues, providing an all-optical method to obtain elastic contrast information. Unlike traditional elastography methods, which typically require contact measurements and are limited to certain applications, PARSE utilizes the time-response characteristics of PA pressure to assess tissue elasticity. The study demonstrated the ability of PARSE to differentiate between bronchial cartilage and soft tissue, thereby validating its effectiveness for evaluating elasticity. By offering a 9.5-times greater distinction detection capability compared to conventional PARS imaging, PARSE significantly expands the scope of traditional PAI (Fig. 11e). This advancement opens new avenues for non-invasive, high-resolution elasticity imaging in biomedical applications.

Conclusion and outlook

In this review, we have explored advances in PAI detection techniques, highlighting both transducer-based and optical sensing methods. We present an integrative analysis that compares these techniques across multiple dimensions, including detection principles, advancements, and biomedical applications. We also address the distinct strengths of these methods for applications such as high-resolution imaging, deep-tissue visualization, and non-invasive diagnostics. Finally, we highlight a detailed classification of detection techniques, providing an in-depth comparison of their characteristics, limitations, and suitability for various biomedical applications, offering readers an integrative and practical perspective.

Conventional piezoelectric TRs, utilizing materials such as PVDF, PZT, PbTiO3, and PMN-PT, have been foundational in various PAI applications. These TRs were categorized as single-element and multi-element configurations, each serving distinct roles in PAI. Single-element TRs, primarily used in PAM, offer high spatial resolution for imaging superficial tissues, albeit with a trade-off between resolution and penetration depth, which is influenced by the center frequency of the TR. Multi-element array TRs, on the other hand, are extensively employed in PACT, allowing for larger FOV and deeper penetration, which are crucial for visualizing anatomical structures in preclinical and clinical contexts. A thorough review of the diverse applications of TRs based on their element configurations has been provided, to allow a comprehensive understanding of their utility in PAI.

Beyond conventional TRs, this review explores the advancements of PMUTs and CMUTs. These advanced TRs leverage MEMS technology to offer enhanced sensitivity, customizable designs, and better integration with electronics. PMUTs, with their thin piezoelectric membranes, are particularly noted for their reduced size, effective acoustic matching, and lower power consumption, making them suitable for various imaging applications. CMUTs also offer high sensitivity and wide bandwidth, making them promising for detailed and accurate imaging. However, it is noteworthy that only one clinical trial involving these technologies has been reported so far91. This indicates the area is still in its early stages and will require further development to fully realize its potential in clinical applications. A summary of studies related to transducer-based technologies can be found in Table 1.

Optical sensing has emerged as a powerful alternative to overcome the limitations inherent in conventional transducer-based PAI systems, particularly in terms of coupling medium requirements and bandwidth limitations. Techniques such as FP interferometers, MRRs, and plano-concave resonators have significantly enhanced the sensitivity and bandwidth of PAI systems. FP interferometers, for example, provide high sensitivity and broad bandwidth without the need for coupling mediums, making them ideal for volumetric and functional imaging of superficial microvasculature. MRR sensors and plano-concave resonators, which leverage optical resonance, offer precise and high-resolution in-vivo imaging with high contrast and broad bandwidth. Furthermore, non-contact methods like PARS have expanded the applicability of PAI by eliminating the need for physical contact with the imaging target, thus broadening the scope of traditional PAI techniques. A summary of studies related to optical sensing technologies can be found in Table 2.

Despite these advancements, PAI detection techniques still face notable challenges. Sensitivity remains a critical issue, particularly in detecting weak signals from deep tissues, where acoustic attenuation and noise interference can obscure critical information. Depth penetration is also limited by acoustic wave scattering and tissue inhomogeneities, restricting the ability to visualize internal organs or deep vasculature with high resolution. Furthermore, the cost and complexity of advanced detection systems, coupled with the computational demands of real-time imaging and image reconstruction, hinder widespread adoption. Limited clinical trials, regulatory barriers, and the lack of standardization in PAI systems further constrain their transition into routine clinical practice.

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach. Future advancements are expected to focus on developing high-sensitivity and broadband detectors capable of improving signal quality and resolution across a wide dynamic range. Innovations in low-frequency transducers and adaptive signal processing algorithms hold promise for enhanced depth penetration and reduced acoustic distortion. AI and machine learning are anticipated to play a transformative role in denoising, image reconstruction, and real-time data interpretation, enabling faster and more accurate imaging. Additionally, cost reduction and system miniaturization through MEMS fabrication will make PAI systems more portable and accessible, broadening their applications in resource-limited settings.

The integration of PAI with other imaging modalities, such as ultrasound, MRI, and optical coherence tomography, will further enhance its diagnostic capabilities by providing complementary information. Non-contact optical sensing methods, such as PARS and FP interferometers, are expected to gain traction for their ability to eliminate the need for coupling media and offer high-resolution, non-invasive imaging. Efforts toward standardization and streamlined regulatory frameworks will also be crucial for clinical translation, facilitating the approval and adoption of advanced PAI systems.

Looking forward, the continuous evolution of PAI technology, driven by interdisciplinary research and collaboration, will address these challenges and expand its potential in biomedical applications. The combination of technical innovation, clinical validation, and cost-effective implementation will position PAI as a leading imaging modality, providing unprecedented insights into biological structures and functions across a range of preclinical and clinical contexts.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Wang, L. V. & Yao, J. A practical guide to photoacoustic tomography in the life sciences. Nat. Methods 13, 627–638 (2016).

Oh, D. et al. Contrast agent‐free 3D Renal ultrafast doppler imaging reveals vascular dysfunction in acute and diabetic kidney diseases. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303966 (2023).

Qiu, T. et al. Photoacoustic imaging as a highly efficient and precise imaging strategy for the evaluation of brain diseases. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 11, 2169 (2021).

Gargiulo, S., Albanese, S. & Mancini, M. State‐of‐the‐Art Preclinical Photoacoustic Imaging in Oncology: Recent Advances in Cancer Theranostics. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2019, 5080267 (2019).

Wang, D., Wu, Y. & Xia, J. Review on photoacoustic imaging of the brain using nanoprobes. Neurophotonics 3, 010901 (2016).

Song, J. et al. Near-infrared-II photoacoustic imaging and photo-triggered synergistic treatment of thrombosis via fibrin-specific homopolymer nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 14, 6881 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Bioinspired large Stokes shift small molecular dyes for biomedical fluorescence imaging. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo3289 (2022).

Yoon, S. et al. Recent advances in optical imaging through deep tissue: imaging probes and techniques. Biomater. Res. 26, 57 (2022).

Wang, L. V. & Hu, S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science 335, 1458–1462 (2012).

Yang, J., Choi, S., Kim, J., Park, B. & Kim, C. Recent advances in deep-learning-enhanced photoacoustic imaging. Adv. Photonics Nexus 2, 054001–054001 (2023).

Yang, J., Choi, S. & Kim, C. Practical review on photoacoustic computed tomography using curved ultrasound array transducer. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 12, 19–35 (2021).

Chen, N. et al. Video-rate high-resolution single-pixel nonscanning photoacoustic microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 13, 3823–3835 (2022).

Gao, R., Xu, Z., Song, L. & Liu, C. Breaking acoustic limit of optical focusing using photoacoustic‐guided wavefront shaping. Laser Photonics Rev. 15, 2000594 (2021).

Kim, J. et al. Enhanced dual-mode imaging: Superior photoacoustic and ultrasound endoscopy in live pigs using a transparent ultrasound transducer. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq9960 (2024).

Wang, L. V. & Gao, L. Photoacoustic microscopy and computed tomography: from bench to bedside. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 155–185 (2014).

Gao, R., Xu, Z., Ren, Y., Song, L. & Liu, C. Nonlinear mechanisms in photoacoustics—powerful tools in photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 22, 100243 (2021).

Park, B., Oh, D., Kim, J. & Kim, C. Functional photoacoustic imaging: from nano-and micro-to macro-scale. Nano Convergence 10, 29 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Three-dimensional Hessian matrix-based quantitative vascular imaging of rat iris with optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 23, 046006 (2018).

Chen, T. et al. Dedicated photoacoustic imaging instrument for human periphery blood vessels: a new paradigm for understanding the vascular health. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 1093–1100 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Visualizing tumor angiogenesis and boundary with polygon-scanning multiscale photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics 26, 100342 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Clinical translation of photoacoustic imaging. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1–20 (2024).

Park, J. et al. Opto-ultrasound biosensor for wearable and mobile devices: realization with a transparent ultrasound transducer. Biomed. Opt. Express 13, 4684–4692 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Non-Invasive Photoacoustic Cerebrovascular Monitoring of Early-Stage Ischemic Strokes In Vivo. Adv. Sci. 2409361, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202409361 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Multiplane Spectroscopic Whole-Body Photoacoustic Computed Tomography of Small Animals In Vivo. Laser Photonics Rev. 2400672, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202400672 (2025).

Choi, W. et al. Recent advances in contrast-enhanced photoacoustic imaging: overcoming the physical and practical challenges. Chem. Rev. 123, 7379–7419 (2023).

Ku, G., Wang, X., Stoica, G. & Wang, L. V. Multiple-bandwidth photoacoustic tomography. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 1329 (2004).

Arnau, A. Piezoelectric transducers and applications. Vol. 2004 (Springer, 2004).

Jeon, S., Kim, J., Lee, D., Baik, J. W. & Kim, C. Review on practical photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics 15, 100141 (2019).

Yao, J. & Wang, L. V. Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 7, 758–778 (2013).

Qiu, Y. et al. Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducer (PMUT) arrays for integrated sensing, actuation and imaging. Sensors 15, 8020–8041 (2015).

Muralt, P. et al. Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers based on PZT thin films. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 52, 2276–2288 (2005).

Roy, K., Lee, J. E.-Y. & Lee, C. Thin-film PMUTs: A review of over 40 years of research. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 95 (2023).

Birjis, Y. et al. Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers (PMUTs): performance metrics, advancements, and applications. Sensors 22, 9151 (2022).

He, Y., Wan, H., Jiang, X. & Peng, C. Piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducer technology: recent advances and applications. Biosensors 13, 55 (2022).

Abdalla, M., Ahmad, M., Windmill, J. F., Cochran, S. & Heidari, H. Ultrasound non-destructive evaluation/testing using capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer (CMUT). In 2022 29th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS). 1–4 (IEEE, 2022).

Shung, K. K., Cannata, J. & Zhou, Q. Piezoelectric materials for high frequency medical imaging applications: A review. J. Electroceram. 19, 141–147 (2007).

Li, C., Luo, W., Liu, X., Xu, D. & He, K. PMN-PT/PVDF nanocomposite for high output nanogenerator applications. Nanomaterials 6, 67 (2016).

Paralı, L. The output performance evaluations of multilayered piezoelectric nanogenerators based on the PVDF-HFP/PMN-35PT using various layer-by-layer assembly techniques. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 35, 796 (2024).

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., He, L., Liang, Y. & Wang, L. Wide-field polygon-scanning photoacoustic microscopy of oxygen saturation at 1-MHz A-line rate. Photoacoustics 20, 100195 (2020).

Baik, J. W. et al. Super wide-field photoacoustic microscopy of animals and humans in vivo. IEEE Trans. Med. imaging 39, 975–984 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Super-resolution localization photoacoustic microscopy using intrinsic red blood cells as contrast absorbers. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 103 (2019).

Choi, S. et al. Versatile single-element ultrasound imaging platform using a water-proofed MEMS scanner for animals and humans. Sci. Rep. 10, 6544 (2020).

Yao, J. et al. High-speed label-free functional photoacoustic microscopy of mouse brain in action. Nat. Methods 12, 407–410 (2015).

Mirg, S., Turner, K. L., Chen, H., Drew, P. J. & Kothapalli, S. R. Photoacoustic imaging for microcirculation. Microcirculation 29, e12776 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Deep learning acceleration of multiscale superresolution localization photoacoustic imaging. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 131 (2022).

Zhao, H. et al. Deep learning enables superior photoacoustic imaging at ultralow laser dosages. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003097 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. Motion correction in optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy. IEEE Trans. Med. imaging 38, 2139–2150 (2019).

Kim, D. et al. An ultraviolet‐transparent ultrasound transducer enables high‐resolution label‐free photoacoustic histopathology. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2300652 (2024).

Sun, A. et al. Multicolor photoacoustic volumetric imaging of subcellular structures. ACS Nano 16, 3231–3238 (2022).

Yoon, C. et al. Deep learning-based virtual staining, segmentation, and classification in label-free photoacoustic histology of human specimens. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 226 (2024).

Park, E. et al. Unsupervised inter-domain transformation for virtually stained high-resolution mid-infrared photoacoustic microscopy using explainable deep learning. Nat. Commun. 15, 10892 (2024).

Ahn, J., Kim, J. Y., Choi, W. & Kim, C. High-resolution functional photoacoustic monitoring of vascular dynamics in human fingers. Photoacoustics 23, 100282 (2021).

Ahn, J. et al. Fully integrated photoacoustic microscopy and photoplethysmography of human in vivo. Photoacoustics, 27, 100374 (2022).

Kim, D., Ahn, J., Park, E., Kim, J. Y. & Kim, C. In vivo quantitative photoacoustic monitoring of corticosteroid-induced vasoconstriction. J. Biomed. Opt. 28, 082805 (2023).

Cho, S. et al. An ultrasensitive and broadband transparent ultrasound transducer for ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging in-vivo. Nat. Commun. 15, 1444 (2024).

Huang, H., Bustamante, G., Peterson, R. & Ye, J. Y. An adaptive filtered back‐projection for photoacoustic image reconstruction. Med. Phys. 42, 2169–2178 (2015).

Treeby, B. E., Zhang, E. Z. & Cox, B. T. Photoacoustic tomography in absorbing acoustic media using time reversal. Inverse Probl. 26, 115003 (2010).

Jeon, S. et al. Real-time delay-multiply-and-sum beamforming with coherence factor for in vivo clinical photoacoustic imaging of humans. Photoacoustics 15, 100136 (2019).

Haltmeier, M., Kowar, R. & Nguyen, L. V. Iterative methods for photoacoustic tomography in attenuating acoustic media. Inverse Probl. 33, 115009 (2017).

Dean-Ben, X. L. & Razansky, D. A practical guide for model-based reconstruction in optoacoustic imaging. Front. Phys. 10, 1028258 (2022).

Jeon, S., Choi, W., Park, B. & Kim, C. A deep learning-based model that reduces speed of sound aberrations for improved in vivo photoacoustic imaging. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 8773–8784 (2021).

Choi, W., Park, E.-Y., Jeon, S. & Kim, C. Clinical photoacoustic imaging platforms. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 8, 139–155 (2018).

Kim, J. et al. Multiparametric photoacoustic analysis of human thyroid cancers in vivo. Cancer Res. 81, 4849–4860 (2021).

Choi, W. et al. Three-dimensional multistructural quantitative photoacoustic and US imaging of human feet in vivo. Radiology 303, 467–473 (2022).

Xia, J., Yao, J. & Wang, L. V. Photoacoustic tomography: principles and advances. Electromagn. Waves 147, 1 (2014).

Na, S. et al. Massively parallel functional photoacoustic computed tomography of the human brain. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 584–592 (2022).

Attia, A. B. E. et al. A review of clinical photoacoustic imaging: Current and future trends. Photoacoustics 16, 100144 (2019).

Gao, R. et al. Background-suppressed tumor-targeted photoacoustic imaging using bacterial carriers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2121982119 (2022).

Aguirre, J. et al. Precision assessment of label-free psoriasis biomarkers with ultra-broadband optoacoustic mesoscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0068 (2017).

Jeon, M., Kim, J. & Kim, C. Multiplane spectroscopic whole-body photoacoustic imaging of small animals in vivo. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 54, 283–294 (2016).

Cloutier, G., Destrempes, F., Yu, F. & Tang, A. Quantitative ultrasound imaging of soft biological tissues: a primer for radiologists and medical physicists. Insights into Imaging 12, 127 (2021).

Landini, L. & Sarnelli, R. Evaluation of the attenuation coefficients in normal and pathological breast tissue. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 24, 243–247 (1986).

Song, K. H. & Wang, L. V. Deep reflection-mode photoacoustic imaging of biological tissue. J. Biomed. Opt. 12, 060503 (2007).

Lee, C., Choi, W., Kim, J. & Kim, C. Three-dimensional clinical handheld photoacoustic/ultrasound scanner. Photoacoustics 18, 100173 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Wang, L. Video-rate ring-array ultrasound and photoacoustic tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 4369–4375 (2020).

Gao, R. et al. Restoring the imaging quality of circular transducer array-based PACT using synthetic aperture focusing technique integrated with 2nd-derivative-based back projection scheme. Photoacoustics 32, 100537 (2023).

Lin, L. et al. High-speed three-dimensional photoacoustic computed tomography for preclinical research and clinical translation. Nat. Commun. 12, 882 (2021).

Merčep, E., Herraiz, J. L., Deán-Ben, X. L. & Razansky, D. Transmission–reflection optoacoustic ultrasound (TROPUS) computed tomography of small animals. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 18 (2019).

Choi, S. et al. Deep Learning Enhances Multiparametric Dynamic Volumetric Photoacoustic Computed Tomography In Vivo (DL‐PACT). Adv. Sci. 10, 2202089 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. 3D Multiparametric Photoacoustic Computed Tomography of Primary and Metastatic Tumors in Living Mice. ACS Nano 18, 18176–18190 (2024).

Kalva, S. K., Deán-Ben, X. L., Reiss, M. & Razansky, D. Spiral volumetric optoacoustic tomography for imaging whole-body biodynamics in small animals. Nat. Protoc. 18, 2124–2142 (2023).

Kalva, S. K., Sánchez-Iglesias, A., Deán-Ben, X. L., Liz-Marzán, L. M. & Razansky, D. Rapid Volumetric Optoacoustic Tracking of Nanoparticle Kinetics across Murine Organs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 172–178 (2021).

Cai, J. et al. Beyond fundamental resonance mode: high-order multi-band ALN PMUT for in vivo photoacoustic imaging. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 116 (2022).

Dangi, A. et al. A photoacoustic imaging device using piezoelectric micromachined ultrasound transducers (PMUTs). IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 67, 801–809 (2019).

Schindel, D. W., Hutchins, D. A., Lichun, Z. & Sayer, M. The design and characterization of micromachined air-coupled capacitance transducers. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 42, 42–50 (1995).

Haller, M. I. & Khuri-Yakub, B. T. A surface micromachined electrostatic ultrasonic air transducer. In 1994 Proceedings of IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. 1241–1244 vol.1242 (IEEE, 1994).

Soh, H., Ladabaum, I., Atalar, A., Quate, C. & Khuri‐Yakub, B. Silicon micromachined ultrasonic immersion transducers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 3674–3676 (1996).

Ergun, A. S., Yaralioglu, G. G. & Khuri-Yakub, B. T. Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducers: Theory and Technology. J. Aerosp. Eng. 16, 76–84 (2003).

Nikoozadeh, A. et al. Photoacoustic imaging using a 9F microLinear CMUT ICE catheter. In 2012 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium. 24–27 (IEEE, 2012).

Nikoozadeh, A. et al. An integrated Ring CMUT array for endoscopic ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging. In 2013 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS). 1178–1181 (IEEE, 2013).

Kothapalli, S.-R. et al. Simultaneous transrectal ultrasound and photoacoustic human prostate imaging. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaav2169 (2019).

Vaithilingam, S. et al. Three-dimensional photoacoustic imaging using a two-dimensional CMUT array. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 56, 2411–2419 (2009).

Gholampour, A. et al. Multiperspective Photoacoustic Imaging Using Spatially Diverse CMUTs. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 70, 16–24 (2023).

Gholampour, A. et al. In Opto-Acoustic Methods and Applications in Biophotonics VI. 126310F (Optica Publishing Group, 2023).

Gholampour, A. et al. A multi-aperture encoding scheme for increased SNR in photoacoustic Imaging. Photoacoustics 37, 100598 (2024).

Chen, R. et al. Transparent High-Frequency Ultrasonic Transducer for Photoacoustic Microscopy Application. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 67, 1848–1853 (2020).

Park, J. et al. Quadruple ultrasound, photoacoustic, optical coherence, and fluorescence fusion imaging with a transparent ultrasound transducer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e1920879118 (2021).

Ilkhechi, A. K., Ceroici, C., Li, Z. & Zemp, R. Transparent capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (CMUT) arrays for real-time photoacoustic applications. Opt. Express 28, 13750–13760 (2020).

Roy, K. et al. Body conformal linear ultrasound array for combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging. In 2020 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS). 1–4 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhang, J., Wiacek, A., Feng, Z., Ding, K. & Lediju Bell, M. A. Flexible array transducer for photoacoustic-guided interventions: phantom and ex vivo demonstrations. Biomed. Opt. Express 14, 4349–4368 (2023).

Ghavami, M., Ilkhechi, A. K. & Zemp, R. Flexible transparent CMUT arrays for photoacoustic tomography. Opt. Express 30, 15877–15894 (2022).

Rasmussen, M. F., Christiansen, T. L., Thomsen, E. V. & Jensen, J. A. 3-D imaging using row-column-addressed arrays with integrated apodization - part i: apodization design and line element beamforming. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 62, 947–958 (2015).

Wong, L. L., Chen, A. I., Li, Z., Logan, A. S. & Yeow, J. T. A row–column addressed micromachined ultrasonic transducer array for surface scanning applications. Ultrasonics 54, 2072–2080 (2014).

Chee, R. K., Sampaleanu, A., Rishi, D. & Zemp, R. J. Top orthogonal to bottom electrode (TOBE) 2-D CMUT arrays for 3-D photoacoustic imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. frequency Control 61, 1393–1395 (2014).

Zemp, R. J., Chee, R., Sampaleanu, A., Rishi, D. & Forbrich, A. S-sequence bias-encoded photoacoustic imaging with top orthogonal to bottom electrode (TOBE) CMUT arrays. In 2013 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS). 1197–1200 (IEEE, 2013).

Ceroici, C. et al. 3D photoacoustic imaging using Hadamard-bias encoding with a crossed electrode relaxor array. Opt. Lett. 43, 3425–3428 (2018).

Cao, X., Yang, H., Wu, Z.-L. & Li, B.-B. Ultrasound sensing with optical microcavities. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 159 (2024).

Zhang, E., Laufer, J. & Beard, P. Backward-mode multiwavelength photoacoustic scanner using a planar Fabry-Perot polymer film ultrasound sensor for high-resolution three-dimensional imaging of biological tissues. Appl. Opt. 47, 561–577 (2008).

Plumb, A. A., Huynh, N. T., Guggenheim, J., Zhang, E. & Beard, P. Rapid volumetric photoacoustic tomographic imaging with a Fabry-Perot ultrasound sensor depicts peripheral arteries and microvascular vasomotor responses to thermal stimuli. Eur. Radiol. 28, 1037–1045 (2018).

Czuchnowski, J. & Prevedel, R. Adaptive optics enhanced sensitivity in Fabry-Pérot based photoacoustic tomography. Photoacoustics 23, 100276 (2021).

Jiang, X., Shen, M., Lun, D. P.-K., Chen, W. & Somekh, M. G. A total-internal-reflection-based Fabry–Pérot resonator for ultra-sensitive wideband ultrasound and photoacoustic applications. Photoacoustics 30, 100466 (2023).

Ansari, R., Zhang, E. & Beard, P. Dual-modality rigid endoscope for photoacoustic imaging and white light videoscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 29, 020502 (2024).

Nadeem, M. D., Raghuwanshi, S. K. & Kumar, S. Recent Advancement of Phase Shifted Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor for Ultrasonic Wave Application: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 7463–7474 (2022).

Yaras, Y. S., Yildirim, D. K., Kocaturk, O. & Degertekin, F. L. Sensitivity and phase response of FBG based acousto-optic sensors for real-time MRI applications. OSA Contin. 3, 447–458 (2020).

Shnaiderman, R. et al. A submicrometre silicon-on-insulator resonator for ultrasound detection. Nature 585, 372–378 (2020).

Liang, Y. et al. Optical-resolution functional gastrointestinal photoacoustic endoscopy based on optical heterodyne detection of ultrasound. Nat. Commun. 13, 7604 (2022).

Hazan, Y., Levi, A., Nagli, M. & Rosenthal, A. Silicon-photonics acoustic detector for optoacoustic micro-tomography. Nat. Commun. 13, 1488 (2022).

La, T. A., Ülgen, O., Shnaiderman, R. & Ntziachristos, V. Bragg grating etalon-based optical fiber for ultrasound and optoacoustic detection. Nat. Commun. 15, 7521 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Transparent microfiber Fabry-Perot ultrasound sensor with needle-shaped focus for multiscale photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 30, 100482 (2023).

Lee, Y., Zhang, H. F. & Sun, C. Highly sensitive ultrasound detection using nanofabricated polymer micro-ring resonators. Nano Convergence 10, 30 (2023).

CzaplewskiDavid, A. & ZhangHao, F. High-frequency 3D photoacoustic computed tomography using an optical microring resonator. BME Front. 2022, 9891510 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Disposable ultrasound-sensing chronic cranial window by soft nanoimprinting lithography. Nat. Commun. 10, 4277 (2019).

Guggenheim, J. A. et al. Ultrasensitive plano-concave optical microresonators for ultrasound sensing. Nat. Photonics 11, 714–719 (2017).

Lewis-Thompson, I., Zhang, E. Z., Beard, P. C., Desjardins, A. E. & Colchester, R. J. All-optical ultrasound catheter for rapid B-mode oesophageal imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 14, 4052–4064 (2023).

Hajireza, P., Shi, W., Bell, K., Paproski, R. J. & Zemp, R. J. Non-interferometric photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16278 (2017).

Hosseinaee, Z., Le, M., Bell, K. & Reza, P. H. Towards non-contact photoacoustic imaging. Photoacoustics 20, 100207 (2020).

Bell, K. L., Haji Reza, P. & Zemp, R. J. Real-time functional photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Opt. Lett. 44, 3466–3469 (2019).

Haven, N. J., Bell, K. L., Kedarisetti, P., Lewis, J. D. & Zemp, R. J. Ultraviolet photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Opt. Lett. 44, 3586–3589 (2019).

Abbasi, S., Bell, K. & Haji Reza, P. Rapid high-resolution mosaic acquisition for photoacoustic remote sensing. Sensors 20, 1027 (2020).

Abbasi, S. et al. Chromophore selective multi-wavelength photoacoustic remote sensing of unstained human tissues. Biomed. Opt. express 10, 5461–5469 (2019).

Abbasi, S. et al. All-optical reflection-mode microscopic histology of unstained human tissues. Sci. Rep. 9, 13392 (2019).