Abstract

Wave propagation in complex media has long been a captivating research topic with diverse applications. The accurate determination of scattering matrices (S-matrices) is crucial for the effective characterization of wave scattering phenomena in such media. This paper presents a detailed exposition of the formulation of S-matrices for two-dimensional acoustic complex media in a multimode waveguide, using channel and point bases. We explore the conversion relationships between these bases and the factors affecting their accuracy and reliability. The effectiveness of the proposed methods for extracting S-matrices is validated by numerical simulations on a complex medium consisting of randomly arranged cylinder scatterers. We successfully achieved acoustic wave focusing in both bases via wavefront shaping. We also reveal that the non-unitary characteristic of the conversion relations is linked to the absence of open channels in the point basis. Our results establish the theoretical and methodological foundation for further study of multiple-scattering phenomena in acoustics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wave propagation in complex media undergoes multiple scattering1. Multiple-scattering waves possess rich degrees of freedom that can be harnessed for diverse functionalities2,3,4,5. Notable examples include coherent perfect absorption6, laser performance enhancement7, targeted energy delivery8, manipulation of complex fields9,10,11,12,13, and wave-based analog computation14,15. However, multiple-scattering waves are substantially more difficult to control compared to ordered waveforms, such as plane waves or Gaussian beams. The scattering matrix (S-matrix) is a powerful tool to handle the transport of waves through complex media. An S-matrix is a connection between input and output waves16,17,18,19. It simplifies the multiple-scattering transport to a linear operator. This enables the description of wave characteristics using linear algebra, which forms the basis for the development of wavefront shaping techniques20,21,22,23. The S-matrix possesses essential information about the system relating to the Green’s function2,5,24, as the two can be converted into each other, and the Wigner–Smith operator2,25,26,27 related to the gradient of the S-matrix is also related to the density of states. At the same time, it has been shown that the zeros and poles of the S-matrix can reflect the system’s topological properties28,29,30. By exploring the properties of S-matrices, significant progress has been made in the control of light and microwaves in complex media8,11,12,26,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. As an important branch of wave physics, acoustics studies the propagation of sound waves that are not only ubiquitous in our daily life but also play important roles in numerous scientific and engineering scenarios. However, until now, the control of multiple-scattering acoustic waves has not experienced the same degree of development—only a handful of works exist for ultrasound in open environments16 and controlling reverberating sound fields in rooms using active acoustic metamaterials and metasurfaces10,12,13. To date, there is no systematic exposition of the S-matrix in the context of acoustic waveguides, nor has the conversion relationship between the two matrix bases been found. Therefore, rigorous derivation of these methods and formulas is essential for future acoustic research involving complex media in waveguides.

In this paper, we present the mathematical formulation of the acoustic S-matrix of a complex medium in a two-dimensional (2D) acoustic multimode waveguide. Two different forms of S-matrices are presented, which are based on different choices of bases: channel basis (or waveguide mode basis) and point basis (or point-to-point basis), respectively. The definitions of these bases are similar to those used in optics and microwaves2,5, and they will be given later. The conversion relations of S-matrices in different bases are also derived. Based on the non-unitary property of the conversion matrix, the differences between the two transmission matrices in exciting open channels are analyzed, and it reveals the reason why the point basis transfer matrix cannot be directly used to excite open channels. Additionally, we provide numerical methods for extracting S-matrices in the channel basis and the point basis. The validity of our results is demonstrated by a case study that numerically synthesizes a wavefront that focuses through a complex medium.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In the Results section, we first give a brief introduction to the theory of 2D acoustic waveguides. Then, the channel-basis and point-basis S-matrices are formally derived, followed by a detailed discussion of the basis conversion relations, which is the core result of this paper. We then validate the conversion relations by considering focusing through a random medium. We then focus on the non-unitary characteristics of the conversion relations by considering the cause of the absence of an open channel in the point-basis S-matrix. Lastly, we wrap up with a miscellaneous discussion.

Results

Acoustic S-matrices for multimode waveguides

Our discussion starts with the theory of acoustic waveguides. The waveguide is formed by sound-hard boundaries on both the \({xy}\) and \({xz}\)-planes, extending infinitely in the \(x\)-direction, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The waveguide has a uniform rectangular cross-section with a height of \(H\) in the z-direction and a width of \(W\) in the \(y\)-direction. The height (\(H\)) is chosen to be smaller than half the wavelength of the sound wave being considered, such that the sound field is approximately uniform in the \(z\)-direction. The sound field in the waveguide can thus be treated as two-dimensional (2D). In this study, sound waves are confined within the waveguide by sound-hard boundaries, resulting in the presence of only guided modes. The number of these modes is determined by the waveguide’s lateral size (as detailed later). Since acoustic waves are scalar longitudinal waves, there are no bulk modes or transverse electric/vertical (TV) modes like those found in electromagnetic waves. In the absence of scatterers, sound propagation within the waveguide is described by a 2D Helmholtz equation

Here, \(P\) represents the pressure field in the frequency domain, \({k}_{0}=\omega /{c}_{0}\) is the magnitude of the wavevector, \({c}_{0}\) is the speed of sound, and \(\omega =2\pi f\) is the angular frequency. The solution of Eq. (1) can be expressed as a series of waveguide modes

where \(n\) is a positive integer that represents the modal number, and \({A}_{n}\) and \({B}_{n}\) are the complex amplitudes of the \(n\) th mode. The \(x\)-component wavevector for the \(n\) th waveguide mode can be determined using \({k}_{n}^{x}=\sqrt{{\omega }^{2}/{c}_{0}^{2}-{\left({k}_{n}^{y}\right)}^{2}}\), with \({k}_{n}^{y}=\left(n-1\right)\pi /W\) as the y-component wavevector. In this paper, we focus solely on modes where \({k}_{n}^{x}\) has a real value, indicating propagating waves. The positive (negative) sign in front of \({k}_{n}^{x}\) in Eq. (2) denotes the left-propagating (right-propagating) waves. The distribution in the \(y\)-direction of the \(n\) th waveguide mode, \({\varPsi }_{n}\left(y\right)\), is given by

valid for all positive integers \(n\). Two fundamental differences between acoustics and optics (or electromagnetism) are immediately obvious here. First, owing to the longitudinal nature of acoustic waves in fluids, \({\varPsi }_{1}\) is a plane-wave mode that does not have a cutoff frequency. Second, sound-hard boundary conditions dictate that the pressure fields peak at the boundary in the normal direction (\(\pm \hat{y}\) in Eq. (3)), so \({\varPsi }_{n > 1}\) are cosine functions. These waveguide modes are both normalized and orthogonal, satisfying

where \({\delta }_{{mn}}\) is the Kronecker delta symbol. The requirement for \({k}_{n}^{x}\) to be real constrains the total number of propagating waveguide modes to

where \({\lfloor} {\cdot} {\rfloor}\) denotes floor operation, i.e., rounding down to the closest integer.

Next, the scattering medium occupies a region of \(0\le x\le {L}_{{\rm{sc}}}\), as shown in Fig. 1a. Unlike an empty waveguide, different propagation modes in the waveguide will be mixed due to the influence of the scattering medium. The explicit form of the S-matrix depends on the chosen basis. One common choice of basis is called ‘the channels’, which are associated with waveguide modes

Here, the superscript L(R) denotes the left (right) lead. It should be noted that this decomposition slightly differs from the waveguide modes described in Eq. (2) due to the additional normalization factor \(\sqrt{{k}_{n}^{x}}\), whose purpose is to ensure equal energy flux in different scattering modes (see Supplementary Note 1 for more details). These adjusted waveguide modes are usually referred to as the scattering channels. The amplitudes of incoming and outgoing scattering channels are represented by the column vectors \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}={\left({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}}},{{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{R}}}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}={\left({c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}},1},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}},N},{c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{R}},1},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{R}},N}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{out}}}={\left({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{L}}},{{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}}}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}={\left({c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{L}},1},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{L}},N},{c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},1},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},N}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\), respectively. The channel-basis S-matrix \(\left({\bf{S}}\right)\) is defined as

where the dimensions of \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{out}}}\) are both \(2N\times 1\) and the S-matrix has dimensions of \(2N\times 2N\). This indicates a total of \(2N\) scattering channels on the left and right leads of the waveguide. The entries \({S}_{{mn}}\) specify the scattering amplitude from the \(n\)-th incoming channel to the \(m\) th outgoing channel.

It is useful to lay down some general properties of the channel-basis S-matrix. In the absence of loss and gain, the total outgoing energy flux must equal to the total incident energy flux, that is \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{\dagger }{{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{out}}}={{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{\dagger }{{\bf{S}}}^{\dagger }{\bf{S}}{{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}={{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{\dagger }{{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}\). Therefore, the channel-basis S-matrix must be unitary

where \({\bf{I}}\) is the identity matrix of dimensions \(2N\times 2N\). Additionally, in the presence of time-reversal symmetry, there is \({{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{* }={\bf{S}}{{\boldsymbol{\psi }}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{* }\). Here, the superscript ‘\(*\)’ represents the conjugate. Substituting this relationship into Eq. (8) leads to \({{\bf{S}}}^{* }{\bf{S}}={\bf{I}}\). Therefore,

This implies that in this context, the S-matrix is a symmetric unitary matrix. The S-matrix can be expressed as a combination of four block matrices

Here, the diagonal blocks, \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}}\), correspond to the reflection matrices for left and right incidence, respectively. The off-diagonal blocks, \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) and \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{R}}}\), correspond to the left-to-right and right-to-left transmission matrices, respectively. Naturally, these block matrices are also transpose invariant, i.e., \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}={{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\), \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}}={{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\), \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}={{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\). The traces of \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}{{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\), denoted as \(T\) and \(R\), are

where \({\tau }_{n}\) and \({\rho }_{n}\) are the eigenvalues of \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}{{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\), respectively. \(N\) is the total number of propagating waveguide modes in the system. Obviously, \(T+R=N\). Singular value decomposition can be applied to the transmission matrix in the channel basis as \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}={\bf{UD}}{{\bf{V}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{N}{\sigma }_{i}{{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{i}{{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{i}^{\dagger }\), where the unitary matrices \({\bf{U}}\) and \({\bf{V}}\) (of size \(N\times N\)) contain the left (\({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{i}\)) and right (\({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{i}\)) singular vectors of \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\) as columns, respectively. The singular vectors have a norm of 1, and any two left (or right) singular vectors are orthogonal. The matrix \({\bf{D}}\) is a diagonal matrix with the diagonal elements being the \(N\) singular values \({\sigma }_{n}=\sqrt{{\tau }_{n}}\), arranged in descending order. Hence, there exists the relationship \({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}{{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}={\bf{V}}{{\bf{D}}}^{2}{{\bf{V}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}={\bf{V}}{\boldsymbol{\tau }}{{\bf{V}}}^{{\boldsymbol{\dagger }}}\), with \({\boldsymbol{\tau }}\) being a diagonal matrix with \({\tau }_{1},{\tau }_{2},\ldots ,{\tau }_{N}\) as diagonal entries. According to random matrix theory, \(\left\{{\tau }_{n}\right\}\) obeys a bimodal distribution \(\rho \left(\tau \right)=\frac{{{{\ell}}}_{t}}{L}\frac{1}{2\tau \sqrt{1-\tau }}\) as the number of channels approaches infinity, where \(L\) is the thickness of complex medium along the waveguide, \({{{\ell}}}_{t}\) is the transport mean free path2. The effective number of open channels can be estimated as \({N}_{{\rm{eff}}}\approx \frac{3}{2}\left\langle T\right\rangle\), which means the effective number of channels contributing to the transmitted field40.

The channel-basis S-matrix has been widely applied in theoretical analyses due to its advantageous characteristics. In addition, in Supplementary Note 2, we provide a detailed explanation for retrieving the channel-basis S-matrix through numerical simulations.

The S-matrix can also be expressed in the point-to-point basis, or simply the point basis, denoted as \({\bf{S}}^{\prime}\). On this basis, the S-matrix connects the input and output physical fields at a set of coordinate points2,19,39. In this paper, \(M\) points are strategically selected at the boundaries \(x=0\) and \(x={L}_{{\rm{sc}}}\) on both sides of the scattering region, totaling \(2M\) points. The selection of points follows two rules: First, the condition \(M\ge N\) must be satisfied to ensure that the point-basis S-matrix captures all channel information. Second, all points must be symmetrically distributed with respect to the centerline. This symmetry ensures accurate conversion between the point-basis and channel-basis S-matrices (see Supplementary Note 4). For simplicity, the sequence of y-coordinates of the points on both leads is chosen to be the same, and given by \(\{{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\ldots ,{y}_{M}\}\), which can be expressed as

where, \(1\le p\le M\). The separation between two adjacent points is \(\Delta y=W/M\), with \(W\) representing the width of the waveguide. Monopole sources are placed at each point for excitation, with each monopole source emitting a field governed by the inhomogeneous Helmholtz equation \(\left({{\boldsymbol{\nabla }}}^{2}+{k}_{0}^{2}\right)P=Q\delta \left({\boldsymbol{x}}-{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}\right)\). Here \(Q\) denotes the source strength with units of Pa, and \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{{\boldsymbol{{\prime} }}}=\left({x}^{{\prime} },{y}^{{\prime} }\right)\) is the position of the monopole source. The resulting scattered sound pressure \({P}_{{\rm{sc}}}(x,y)\) is recorded at \(2M\) points to construct the output vector, i.e., \({{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{{\rm{out}}}={\left({{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{L}}},{{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}}}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}={\left({P}_{{\rm{sc}}}(0,{y}_{1}),\ldots ,{P}_{{\rm{sc}}}(0,{y}_{M}),{P}_{{\rm{sc}}}({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{1}),\ldots ,{P}_{{\rm{sc}}}({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{M})\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\). The point-basis S-matrix reads

This equation, \({{\bf{S}}}^{{\prime} }\) relates the set of monopole source \({{\boldsymbol{Q}}}_{{\rm{in}}}={\left({{\boldsymbol{Q}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}}},{{\boldsymbol{Q}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{R}}}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}={\left(Q(0,{y}_{1}),\ldots ,Q(0,{y}_{M}),Q({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{1}),\ldots ,Q({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{M})\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\) to the scattered sound pressure \({{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{{\rm{out}}}\) at the 2M points. Naturally, \({{\bf{S}}}^{{\prime} }\) generally does not exhibit unitary properties. The dimension of \({{\bf{S}}}^{{\prime} }\) is \(2M\times 2M\), which can also be expressed in a block form as

where the diagonal blocks correspond to the reflection matrices under left (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\prime} }\)) and right (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\prime} }\)) incidence, and the off-diagonal blocks correspond to the transmission matrices from left to right (\({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}^{{\prime} }\)) and from right to left (\({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{R}}}^{{\prime} }\)). All four blocks are \(M\times M\) in dimension.

Conversion of S-matrices between channel and point bases

The theoretical foundation for this conversion lies in the connection between the system Green’s function and the S-matrix. The Green’s function describes the response of a system to a point source or point perturbation. In the case of wave propagation within a waveguide containing multiple scattering media, the Green’s function can be used to calculate the sound field at any point in the system, given the source and boundary conditions. Once the sound field is determined by Green’s function, it can be decomposed into scattering channels. Thus, the conversion of channel-based and point-based S-matrix is achieved. The detailed description is presented in Supplementary Note 3.

Here, we focus only on converting the left-incident reflection matrix (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\)) and the left-to-right transmission matrix (\({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\)) from the channel basis to the point basis. The conversion relations are the same for the case of incidence from the right side. To simplify the expression, we omit the subscript ‘\({\rm{L}}\)’. Same as the previous section, the \(x\)-coordinates of the input and output planes are \(x=0\) and \(x={L}_{{\rm{sc}}}\), which also serve as the reference zero phase surface for the left and right ports, respectively. This choice aligns with the definition of the scattering channels as presented in Eq. (6). It is worth noting that this choice of the zero-phase plane also simplifies the relationship between the S-matrix in the channel basis and the point basis. Since we are considering the left-incidence case, we first assume that a monopole source with strength \(Q{(0,y}_{q})\) is placed at the left boundary of the scattering region with coordinates \({(0,y}_{q})\), and then the scattered sound pressure \({P}_{{\rm{sc}}}\left(x,y\right)\) is detected at positions \((0,{y}_{p})\) and \(({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{p})\), denoted as \({P}_{{\rm{sc}}}(0,{y}_{p})\) and \({P}_{{\rm{sc}}}({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{p})\), respectively. According to Eqs. (13) and (14), we can define the entries of the point-basis reflection matrix \({\bf{r}}^{{{\prime} }}\) as \({r}_{{pq}}^{{\prime} }={P}_{{\rm{sc}}}(0,{y}_{p})/Q({0,y}_{q})\), and the entries of the point-basis transmission matrix \({\bf{t}}^{{{\prime} }}\) as \({t}_{{pq}}^{{\prime} }={P}_{{\rm{sc}}}({{L}_{{\rm{sc}}},y}_{p})/Q({0,y}_{q})\). They can be expressed using the Green’s function. The Green’s function for the empty waveguide (Please refer to Supplementary Note 3 for details) can be expanded using the waveguide modes

where \(G\left(x,{y;}{x}^{{\prime} },{y}^{{\prime} }\right)\) represents the response at (\(x,y\)) by excitation at \(\left({x}^{{\prime} },{y}^{{\prime} }\right)=(0,{y}_{q})\), and \({\varPsi }_{n}\left(y\right)\) is the \(n\) th waveguide mode as defined in Eq. (3). It follows that the sound field excited by a monopole source at \((0,{y}_{q})\) can be expressed as

Then, we can express the left incident field as

The left incident field can then be straightforwardly expressed using the scattering channels

Here, the summation is truncated at \(n=N\) to omit the waveguide modes that are evanescent in \(x\). The expression of \({a}_{n}\) is obtained by computing the inner product of \({P}_{{\rm{in}}}\left(0,y\right)\) and \({\varPsi }_{i}\left(y\right)\), that is

We arrive at

The coefficients of the left-outgoing waves in scattering channels are given by

where \({r}_{{mn}}\) is the reflection coefficient from the \(n\) th to \(m\) th channels. Therefore, the left scattered pressure

By substituting Eq. (21) into Eq. (22), we obtain

Here, we have defaulted \(Q{(0,y}_{q})=1{\rm{Pa}}\). To simplify, we define matrix \({\mathbf{\Phi }}\) with entries \({\varPhi }_{{nq}}={\varPsi }_{n}({y}_{q})\), having dimensions \(N\times M\). According to the orthogonality condition, \({\mathbf{\Phi }}{{\mathbf{\Phi }}}^{{\rm{T}}}=\frac{M}{W}{{\bf{I}}}_{N\times N}\). We also define a diagonal matrix \({\bf{R}}\) with entries \({R}_{{mn}}=\sqrt{{k}_{m}^{x}}{\delta }_{{mn}}\), having dimensions \(N\times N\). Here, \({k}_{m}^{x}\) is the x-component wavevector for the \(n\)-th waveguide mode. Furthermore, we introduce a transformation matrix \({\bf{K}}=\frac{{\bf{1}}}{{\bf{2}}}\left(1+j\right){{\bf{R}}}^{-1}{\mathbf{\Phi }}\), with its entries given by \({K}_{{mp}}=\frac{1}{2}(1+j)\frac{{\varPsi }_{m}\left({y}_{p}\right)}{\sqrt{{k}_{m}^{x}}}\) and a dimension of \(N\times M\) (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). Eq. (23) can be rewritten in matrix form as

where, \({\bf{r}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}^{{\boldsymbol{{\prime} }}}\), respectively represent the reflection matrix in the channel basis and point basis. Similarly, we can obtain similar formulas for the left-to-right transmission matrix in the point basis (\({t}_{{pq}}^{{\prime} }\)) as

where \({t}_{{mn}}\) is the transmission coefficient from the \(n\) th to \(m\) th channels. And we arrive at

We remark that the dimensions of \({\bf{t}}\) and \({{\bf{t}}}^{{\boldsymbol{{\prime} }}}\) can be different, so the matrix \({\bf{K}}\) is generically a rectangular matrix.

The conversion from point to channel basis is equivalent to obtaining the pseudo-inverse of \({{\bf{K}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\), which is \({\bf{J}}={\left({{\bf{K}}}^{* }{{\bf{K}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\right)}^{-1}{{\bf{K}}}^{* }=\left(1-j\right)\frac{W}{M}{\bf{R}}{\mathbf{\Phi }}\), such that \({\bf{J}}{{\bf{K}}}^{{\rm{T}}}={{\bf{I}}}_{N\times N}\). (The pseudo-inverse matrix of a column full rank matrix \({\bf{A}}\) is given by \({\left({{\bf{A}}}^{\dagger }{\bf{A}}\right)}^{-1}{{\bf{A}}}^{\dagger }\). \({{\bf{K}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\) has a dimension of \(M\times N\) with \(M\ge N\), and it is column full rank41). The entries of \({\bf{J}}\) are \({J}_{{mp}}=\left(1-j\right)\frac{W}{M}\sqrt{{k}_{m}^{x}}{\varPsi }_{m}({y}_{p})\). Similarly, it can be shown that matrix \({\bf{K}}\) is the pseudo-inverse matrix of \({{\bf{J}}}^{{\rm{T}}}\), as \({\bf{K}}{{\bf{J}}}^{{\rm{T}}}={{\bf{I}}}_{N\times N}\). Consequently, the conversion from point basis to channel basis is given by

It is important to note that this conversion is accurate only when the number of points \(M\) is sufficient (\(M\ge N\)) and they are selected symmetrically about the central line of the waveguide, i.e., with locations following Eq. (12). For further details and a proof, please refer to Supplementary Note 4 and Note 5.

We remark that an implicit assumption for the accurate conversion is that the effect of evanescent modes is negligible. The channel basis, by definition, considers only propagative modes and ignores any evanescent modes. But the point basis can indeed pick up evanescent modes from the scattering. So, the measurement plane needs to be sufficiently far (\(> \lambda /2\)) from the scattering media for evanescent modes to be negligible.

Focusing using acoustic complex media

This section presents a numerical case study of focusing spatially modulated acoustic waves through a complex medium. The purpose of this case study is to validate the basis conversion relations and to demonstrate the application of S-matrices in channel and point bases.

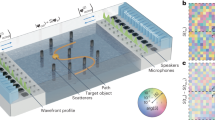

The complex medium consists of 100 rigid cylinder scatterers, each with a diameter of 0.02 m, randomly distributed within a 2D air-filled waveguide of width \(W=1\,{\rm{m}}\) (see Fig. 2a, b). The sound frequency employed is \({f}_{0}=8500\,{\rm{Hz}}\), corresponding to a sound wave wavelength of approximately \({\lambda }_{0}=0.04\,{\rm{m}}\), so the waveguide sustains 50 propagative modes, i.e., the number of channels is \(N=50\). The complex medium occupies a rectangular region of \({d}_{{\rm{sc}}}\times W\) in the waveguide, with \({d}_{{\rm{sc}}}=0.50{\rm{m}}\) extending along the \(x\)-direction. To safely neglect the evanescent waves, the measurement planes are positioned at a distance of approximately \({l}_{{\rm{air}}}=0.25\,{\rm{m}}\approx 6{\lambda }_{0}\) away from both the left and right-hand sides of the complex medium. The separation between the two measurement planes is \({L}_{{\rm{sc}}}=2{l}_{{\rm{air}}}+{d}_{{\rm{sc}}}=1\,{\rm{m}}\). For simplicity, the number of sampling points is chosen to be equal to the number of channels, i.e., \(M=N=50\). Our calculation indicates \(T\approx 18.60\), and the effective number of open channels can be estimated as \({N}_{{\rm{eff}}}\approx \frac{3}{2}\left\langle T\right\rangle \approx 28\), while the remaining \(N-{N}_{{\rm{eff}}}=22\) channels are classified as closed (i.e., \(\tau \approx 0\) for them)19. Given these parameters, the transmission mean free path2 is estimated to be approximately \({{{\ell}}}_{{\rm{tr}}}\approx 0.18\,{\rm{m}}\). Additionally, the scattering mean free path of the complex medium can be estimated about \({{{\ell}}}_{{\rm{sc}}}\approx 0.16\,{\rm{m}}\) (see Methods for details).

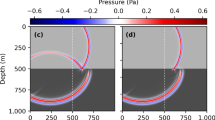

a Illustration of the problem setting. b Amplitude of the total pressure field in a complex medium illuminated by an acoustic plane wave, revealing a speckle-like sound field distribution, with a local magnification inset. c Real parts of the transmission matrices in the channel basis (upper left panel) and the point basis (lower left panel), respectively. The transmission matrix is then transformed into the point basis (channel basis) through basis conversion, as shown in the lower right panel (upper right panel).

In Fig. 2b, the scattering behavior of a plane wave is depicted, showcasing the notable distortion of the wavefront due to the presence of the complex medium. The transmission matrices are directly acquired in both the channel and point bases, and the real components of these matrices are depicted in the left two panels of Fig. 2c. Then, the channel-basis transmission matrix is transformed into the point basis using Eq. (26). And conversely, the point-basis transmission matrix is transformed into the channel basis using Eq. (28). The corresponding results are shown in the right two panels of Fig. 2c. Excellent agreement is seen. This successful alignment validates the accuracy of our basis conversion relationships.

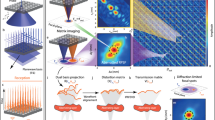

Next, based on the transmission matrices in the two different bases, we use the technique of inverse filtering42 to synthesize acoustic wavefronts to achieve focusing through the complex medium. The target is to generate one focal spot at a distance \({L}_{{\rm{f}}}=0.2{\rm{m}}\) away from the output plane. The wavefield (\({P}_{{\rm{f}}}\left(x,y\right)\)) at the output plane (\(x={L}_{{\rm{sc}}})\) is chosen as43

Expand this equation using the channels

Here, \({c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},n}\) represents the output channel coefficients. By multiplying both sides of Eq. (30) by \({\varPsi }_{m}\left(y\right)\) and integrating across the cross-section, with the orthogonality, we arrive at

Utilizing the relationship \({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}}}={\bf{t}}{{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}}}\), where \({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}}}={\left({c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},1},{c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},2},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}},N}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{c}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}}}={\left({c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}},1},{c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}},2},\ldots ,{c}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}},N}\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\). Therefore, we can express the amplitudes of the incident channels as

where the matrix \({\bf{t}}\) is the same as shown in Fig. 2c. The resulting focusing effect based on the channel basis can be observed in the upper panels of Fig. 3b, c.

a Demonstration of the focusing principle. b Focusing effect using channel basis (upper) and point basis (lower) with a logarithmic colormap. c Sound pressure distribution in the focal area shown with a linear colormap. d, e Amplitude and phase distributions on planes A and B, respectively. Plane A, situated 0.1 m from the input plane, is excluded from the input plane due to infinite pressure from the monopole excitation of the point-based method. Plane B represents the focal plane, where red lines indicate the results in channel basis, and blue lines represent the results in point basis.

A similar focusing can be obtained using the point-based transmission matrix. To this end, we discretize the output wavefield (Eq. (29)) at a set of discrete points \(\left\{{y}_{1},{y}_{2},\ldots {y}_{M}\right\}\), obtaining the point-basis output vector \({{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{{\rm{out}}}^{{\rm{R}}}={\left({P}_{{\rm{f}}}\left({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{1}\right),{P}_{{\rm{f}}}\left({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{2}\right),\ldots ,{P}_{{\rm{f}}}\left({L}_{{\rm{sc}}},{y}_{M}\right)\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\), which is the result of a set of monopole sources \({{\boldsymbol{Q}}}_{{\rm{in}}}^{{\rm{L}}}={\left(Q\left(0,{y}_{1}\right),Q\left(0,{y}_{2}\right),\ldots ,Q\left(0,{y}_{M}\right)\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\) at the input plane \((x=0)\), given by

The focusing effect based on the point-basis method is shown in the lower panels in Fig. 3b, c.

Examining the results in Fig. 3b–e, excellent agreement is seen between the results obtained using the channel and point bases in both the overall field map and the pressure distribution on various planes. The slight degree of discrepancy in Fig. 3d, e will diminish with the further increase of the number of channels and sampling points.

The open channel of the transmission matrix

Here, we compare open channels in the two types of bases and analyze their differences in transmission efficiency. According to the theory of random matrices, channels with transmittance close to 1 almost always exist in complex media. However, these channels are typically excited only within the transmission matrix in channel basis (\({{\bf{t}}}_{{\rm{L}}}\)). The open channel (full transmission) takes the first right singular vector \({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{1}\) as the input wavefront, which is associated with the largest singular value \({\sigma }_{1}\), and its transmittance approaches unity in the channel basis. This results in the first left singular vector \({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{1}\) as the output wavefront, i.e.,

Equation (26) describes a mapping from channel to point basis, noting that

Due to the varying propagation wave vectors across different modes in multimode waveguides, \({\bf{R}}\) is not a unitary matrix, and \({\bf{K}}\) is also non-unitary (see Note 5 in the Supplementary Information for details). Consequently, the conversion alters the magnitudes of the singular values, which may also shuffle the order of the singular vectors. To be more specific, when \({{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{1}\) is the first right singular vector of \({\bf{t}}^{\prime}\), the corresponding channel coefficient is not necessarily the first right singular vector \({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{1}\) of \({\bf{t}}\) (or proportional to it). Therefore, using the singular vectors associated with the largest singular value for excitation, the transmission matrix in point basis generally cannot achieve full transmission (see Note 6 in the Supplementary Information for details).

Here, we employ the same complex medium utilized in the focusing to validate this conclusion. In Fig. 4, we present the acoustic fields generated by a left-hand side input vector with the first singular value of the transmission matrices in the two bases. In the case of channel basis, this is an open channel with a singular value > 0.99 (Fig. 4a). Total transmission is seen. In contrast, in the point basis scenario, the maximum singular value is only ~0.32, so transmission is much weaker (transmitted flux ~0.56) and there is notable reflection (Fig. 4b). Consequently, open channels generally cannot be obtained using the point basis.

Discussion

In this study, we present the mathematical foundation for establishing S-matrices for acoustic wave propagation in complex media in 2D. The S-matrices are constructed in two different bases, the channel basis and the point basis. The conversion between S-matrices in the two bases is rigorously derived. The effectiveness and accuracy of our results are demonstrated through a case study of focusing through a complex medium.

In practice, the S-matrix comprehensively provides the information of the multiple scattering media, which enables a wide array of applications and functionalities. The focus demonstrated in our work is just one simple example. However, obtaining the complete S-matrix usually requires measurement of sufficient accuracy and a good signal-to-noise ratio, which can be challenging in experiments. In comparison, the time-reversal method22,31,44,45,46,47, as a different approach, does not require a complete characterization of the medium, which is easier to implement but is less flexible in achieving diverse functionalities. These methods complement each other and shall be used selectively or collectively for the best possible results.

By providing a systematic description of the acoustic S-matrix in acoustic waveguides, our work provides the foundation for future research in acoustic complex media and acoustic wavefront shaping. We anticipate our results will be useful for future studies on controlling multiple scattering of acoustic waves in complex or random media. The results can be further generalized to handle acoustic multiple-scattering propagation in three dimensions. By including higher-order, non-propagative waveguide modes as channels or by further refining the spatial sampling rate of the point basis, it is also possible to modify the theory for handling evanescent waves.

Methods

Numerical simulation

Finite element simulations were performed with the pressure acoustics module and the Livelink for MATLAB module of the COMSOL Multiphysics software. The sound speed is \(343\,{\rm{m}}/{\rm{s}}\), and the acoustic impedance of air is \(411.6\,{\rm{Pa}}\,{\rm{s}}/{\rm{m}}\). The retrieval methods for the S-matrices in channel and point bases are described in detail in Supplementary Note 3.

The scattering mean free path

The scattering mean free path in the two-dimensional region was estimated using both a simplified theoretical method and a more detailed computational approach. Initially, the theoretical approximation was calculated using the formula \({{{\ell}}}_{{sc}}=\pi A/L\), where \(A\) is the area available for sound wave propagation and \(L\) is the total length of all scattering boundaries48. The rectangular region containing \(100\) scatterers, \(A\) was calculated as 0.4686 m2 (the area of the rectangular region minus the total area of all the circular scatterers) and \(L\) was calculated as 9.283 m (perimeter of the rectangular region plus the total perimeter of the scatterers). This gives an approximate mean free path of 0.1586 m. To refine this estimate, the ray tracing module of COMSOL was employed, which statistically estimates the mean free path by tracking scattering events and path lengths in the simulation. One hundred simulations with randomly distributed scatterers were averaged, resulting in a mean free path of 0.1597 m, aligning closely with the theoretical estimate. The simulations considered only the scattering region, defining both the rectangular and scatterer boundaries as acoustically hard, without accounting for losses.

Data availability

The data that generated the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Sheng, P. Introduction to Wave Scattering, Localization, and Mesoscopic Phenomena. (Springer, Berlin, New York, 2006).

Rotter, S. & Gigan, S. Light fields in complex media: mesoscopic scattering meets wave control. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015005 (2017).

Cao, H., Mosk, A. P., & Rotter, S. Shaping the propagation of light in complex media. Nat. Phys. 18, 994–1007 (2022).

Cao, H. & Eliezer, Y. Harnessing disorder for photonic device applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9, 011309 (2022).

Vynck, K. et al. Light in correlated disordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045003 (2023).

Slobodkin, Y. et al. Massively degenerate coherent perfect absorber for arbitrary wavefronts. Science 377, 995–998 (2022).

Cao, H., Chriki, R., Bittner, S., Friesem, A. A. & Davidson, N. Complex lasers with controllable coherence. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 156–168 (2019).

Bender, N. et al. Depth-targeted energy delivery deep inside scattering media. Nat. Phys. 18, 309–315 (2022).

Kaina, N., Dupré, M., Lerosey, G. & Fink, M. Shaping complex microwave fields in reverberating media with binary tunable metasurfaces. Sci. Rep. 4, 6693 (2014).

Ma, G., Fan, X., Sheng, P. & Fink, M. Shaping reverberating sound fields with an actively tunable metasurface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6638–6643 (2018).

del Hougne, P., Fink, M. & Lerosey, G. Optimally diverse communication channels in disordered environments with tuned randomness. Nat. Electron. 2, 36–41 (2019).

Wang, Q., Del Hougne, P. & Ma, G. Controlling the spatiotemporal response of transient reverberating sound. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 044007 (2022).

Zhang, H., Wang, Q., Fink, M. & Ma, G. Optimizing multi-user indoor sound communications with acoustic reconfigurable metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 15, 1270 (2024).

del Hougne, P. & Lerosey, G. Leveraging chaos for wave-based analog computation: demonstration with indoor wireless communication signals. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041037 (2018).

Matthès, M. W., del Hougne, P., de Rosny, J., Lerosey, G. & Popoff, S. M. Optical complex media as universal reconfigurable linear operators. Optica 6, 465 (2019).

Aubry, A. & Derode, A. Random matrix theory applied to acoustic backscattering and imaging in complex media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 084301 (2009).

Popoff, S. M. et al. Measuring the transmission matrix in optics: an approach to the study and control of light propagation in disordered media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 100601 (2010).

Popoff, S. M., Lerosey, G., Fink, M., Boccara, A. C. & Gigan, S. Controlling light through optical disordered media: transmission matrix approach. N. J. Phys. 13, 123021 (2011).

Gérardin, B., Laurent, J., Derode, A., Prada, C. & Aubry, A. Full transmission and reflection of waves propagating through a maze of disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 173901 (2014).

Bohm, J. & Kuhl, U. Wave front shaping in quasi-one-dimensional waveguides. in 2016 IEEE Metrology for Aerospace (MetroAeroSpace) 182–186 (IEEE, Florence, Italy, 2016).

Yu, Z. et al. Wavefront shaping: a versatile tool to conquer multiple scattering in multidisciplinary fields. Innovation 3, 100292 (2022).

Lerosey, G. & Fink, M. Wavefront shaping for wireless communications in complex media: from time reversal to reconfigurable intelligent surfaces. Proc. IEEE 110, 1210–1226 (2022).

Resisi, S., Viernik, Y., Popoff, S. M. & Bromberg, Y. Wavefront shaping in multimode fibers by transmission matrix engineering. APL Photonics 5, 036103 (2020).

Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995).

Rotter, S., Ambichl, P. & Libisch, F. Generating particlelike scattering states in wave transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 120602 (2011).

Ambichl, P. et al. Focusing inside disordered media with the generalized Wigner-Smith operator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 033903 (2017).

Horodynski, M. et al. Optimal wave fields for micromanipulation in complex scattering environments. Nat. Photonics 14, 149–153 (2020).

Fulga, I. C., Hassler, F. & Akhmerov, A. R. Scattering theory of topological insulators and superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 85, 165409 (2012).

Fulga, I. C. & Maksymenko, M. Scattering matrix invariants of Floquet topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 93, 075405 (2016).

Guo, C., Li, J., Xiao, M. & Fan, S. Singular topology of scattering matrices. Phys. Rev. B 108, 155418 (2023).

Mosk, A. P., Lagendijk, A., Lerosey, G. & Fink, M. Controlling waves in space and time for imaging and focusing in complex media. Nat. Photonics 6, 283–292 (2012).

Katz, O., Small, E., Bromberg, Y. & Silberberg, Y. Focusing and compression of ultrashort pulses through scattering media. Nat. Photonics 5, 372–377 (2011).

Vellekoop, I. M. & Mosk, A. P. Focusing coherent light through opaque strongly scattering media. Opt. Lett. 32, 2309 (2007).

Popoff, S., Lerosey, G., Fink, M., Boccara, A. C. & Gigan, S. Image transmission through an opaque material. Nat. Commun. 1, 81 (2010).

Sarma, R., Yamilov, A. G., Petrenko, S., Bromberg, Y. & Cao, H. Control of energy density inside a disordered medium by coupling to open or closed channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 086803 (2016).

Cao, H., Sarma, R., Bromberg, Y., Yamilov, A. & Petrenko, S. Control of optical intensity distribution inside a disordered waveguide. in Frontiers in Optics 2016 FW2D.1 (OSA, Rochester, New York, 2016).

Jeong, S. et al. Focusing of light energy inside a scattering medium by controlling the time-gated multiple light scattering. Nat. Photonics 12, 277–283 (2018).

del Hougne, P., Lemoult, F., Fink, M. & Lerosey, G. Spatiotemporal wave front shaping in a microwave cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 134302 (2016).

Horodynski, M., Kühmayer, M., Ferise, C., Rotter, S. & Davy, M. Anti-reflection structure for perfect transmission through complex media. Nature 607, 281–286 (2022).

Vellekoop, I. M. & Mosk, A. P. Universal optimal transmission of light through disordered materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 120601 (2008).

Hogben, L. Handbook of Linear Algebra. (CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, 2014).

Tanter, M., Aubry, J.-F., Gerber, J., Thomas, J.-L. & Fink, M. Optimal focusing by spatio-temporal inverse filter. I. Basic principles. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 37–47 (2001).

Wang, Q., Fink, M. & Ma, G. Maximizing focus quality through random media with discrete-phase-sampling lenses. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 034084 (2023).

Tanter, M., Thomas, J.-L. & Fink, M. Time reversal and the inverse filter. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108, 223–234 (2000).

Montaldo, G., Tanter, M. & Fink, M. Real time inverse filter focusing through iterative time reversal. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115, 768–775 (2004).

Bacot, V., Labousse, M., Eddi, A., Fink, M. & Fort, E. Time reversal and holography with spacetime transformations. Nat. Phys. 12, 972–977 (2016).

Montaldo, G. et al. Telecommunication in a disordered environment with iterative time reversal. Waves Random Media 14, 287–302 (2004).

Akkermans, E. & Montambaux, G. Mesoscopic Physics of Electrons and Photons. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the support from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1404400), the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RFS2223-2S01, 12300925), and the Hong Kong Baptist University (RC-RSRG/23-24/SCI/01, RC-SFCRG/23-24/R2/SCI/12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. initialized and supervised the research. H.Z. performed theoretical analysis and numerical simulations. T.D. contributed to the numerical simulations and proofread the formulas and the first draft. H.Z. and G.M. analyzed the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Delaporte, T. & Ma, G. Scattering matrices of two-dimensional complex acoustic media. npj Acoust. 1, 17 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00020-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00020-x