Abstract

Bird sound recognition poses challenges due to complex, overlapping spectral patterns. We propose a novel framework that combines multi-scale texture-aware modeling with interpretable deep learning. Central to our method is the Directional Laplacian of Gaussian Network (DLoGNet), a convolutional architecture with learnable orientation and scale parameters to capture directional acoustic textures. Additionally, we design the Frequency Band Recalibrated Spectrogram (FBRS), which adaptively selects energy-dense sub-bands via wavelet packet decomposition. Experiments on real-world datasets show that our method outperforms conventional CNNs, RNNs, and attention-based models in both accuracy and class separability. Visualizations of learned filters and t-SNE embeddings support its interpretability and effectiveness. This study highlights the importance of directional and multi-scale features in acoustic signal understanding and offers a robust solution grounded in the principles of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), providing interpretable directional features and visual insights into model decisions for bird species identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, bird sound classification has emerged as a crucial task in ecological monitoring and biodiversity conservation, playing a vital role in applications such as species population surveys, habitat assessment, automatic wildlife monitoring, and environmental impact studies1. Through initiatives such as Xeno-canto, the Macaulay Library and various citizen science platforms, the global audio archives of natural soundscapes continue to grow the ability to automatically and reliably identify bird species from their vocalizations has transitioned from a niche research area to a fundamental tool in conservation biology and ecological research2.

From an acoustic perspective, bird sound classification presents significant challenges. Bird vocalizations are not merely simple signals but are rich, multidimensional phenomena composed of varying frequency modulations, rhythms, harmonic structures, and species-specific calling patterns3,4,5. These acoustic features can vary dramatically not only across species but also across individuals, geographic regions, and behavioral contexts, making bird sound recognition a highly complex pattern recognition problem.

Traditionally, bird sound classification systems relied on handcrafted features such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs)6, spectral centroid7, bandwidth, and pitch contours8, extracted from short-time audio frames. Although grounded in acoustic and perceptual principles, these features are often fed into shallow classifiers such as support vector machines (SVMs)9, random forests (RFs)10, or k-nearest neighbors (k-NN)11. For example, Han et al.12 used MFCC as an acoustic feature and ECOC-SVM as a feature processor and discriminator to achieve high-precision bird recognition. Revathi et al.10 performed RF-based decision-level fusion of multiple perceptual features with filter features of different frequency scales, which significantly improved recognition reliability. More feature extraction techniques and integration with machine learning can be found in the review work by Priyadarshani et al.13 However, such approaches struggle to capture the nonlinear, hierarchical nature of bird vocalizations and often fail to generalize well across diverse and noisy natural environments. The advent of deep learning has profoundly transformed bird sound classification research. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)14, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)15, and their hybrids16 have demonstrated strong capabilities in modeling raw waveforms, spectrograms, and other signal representations, often achieving substantial improvements over traditional methods. Recently, newer architectures such as Transformers17 have also demonstrated competitiveness. Furthermore, attention frameworks are increasingly being introduced into traditional architectures to enhance recognition accuracy18. Das et al.19 point out in their review that machine learning techniques, including both conventional and deep learning approaches, can reduce noise and identify species or even individual birds by their calls. However, despite these advances, most deep learning models remain inherently opaque, offering little transparency into the decision-making process.

In ecological applications, scientific validation, interpretability, and trust are paramount, and this black-box nature of deep learning models poses significant limitations. Understanding what acoustic features a model “hears” and “uses” to distinguish bird species is critical, not only for scientific validation but also for broader adoption in conservation initiatives20. Models that provide no insight into their reasoning can undermine confidence, hinder scientific discoveries, and limit their utility in policy-making or automated monitoring systems. Moreover, the choice of signal representation fundamentally shapes model behavior21. Bird vocalizations, being highly nonstationary and structured across multiple temporal and spectral scales, demand effective time-frequency analysis22. Standard approaches like the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT)23, the Constant-Q Transform (CQT)24, and the Wavelet Transform (WT)25 offer various trade-offs between time and frequency resolution. While these representations (e.g., STFT, CQT, WT) provide mathematically consistent time-frequency resolution, they lack adaptivity to the energy distribution observed in bird calls. This can lead to over-representation of irrelevant bands and under-representation of species-specific acoustic structures, such as modulated syllables or harmonics concentrated in ecologically important frequency ranges4,25. The challenges of the opacity of deep learning models and the limited interpretability of standard time-frequency representations highlight a key gap in current research on bird sound classification: the urgent need for frameworks that not only provide high classification accuracy, but also interpretable outputs that are consistent with known ecologically informative acoustic patterns (e.g., harmonics and frequency contours in bird vocalizations) through convolutional response and Grad-CAM visual validation.

To address this issue, we present a novel framework that combines multi-scale texture modeling with interpretable deep feature extraction. First, to reduce the opacity of standard deep models, we design directional filters with explicitly learnable parameters (orientation θ and scale σ) that can be visualized and interpreted in relation to spectrotemporal structures in bird calls. Second, instead of relying solely on abstract feature hierarchies, our model leverages biologically inspired directional convolution, enabling feature maps that correspond to intuitive acoustic events (e.g., ascending chirps or horizontal harmonics). Finally, through parameter visualization and class activation mapping, our model supports inspection of internal decision logic, thereby advancing explainable deep learning in the bioacoustics domain. In parallel, we propose a new time-frequency representation called the Frequency-Band Recalibrated Spectrogram (FBRS). This representation leverages wavelet packet decomposition and energy-guided sub-band selection to construct a sparse yet informative input, aligning the spectral resolution of the model with the actual energy distribution in bird sounds. Through the integration of these components, our method offers both high classification performance and feature-level interpretability. Furthermore, we validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach through extensive experiments and visualizations, including parameter inspection, convolutional activation analysis, and t-SNE projection of the learned embeddings.

Results

Data and pre-processing

The dataset used in this study is sourced from Kaggle, available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ayush5556/bird-sound-dataset. It contains recordings of bird vocalizations from 22 different species. Each audio sample is non-uniform in length and recorded at a sampling rate of 32 kHz. For the purposes of this study, we selected a subset of eight bird species: Barn Swallow (barswa), Black Crowned Night Heron (bcnher), Black Winged Stilt (bkwsti), Blyth’s Reed Warbler (blrwar1), Common Greenshank (comgre), Common Kingfisher (comkin1), Common Moorhen (commoo3), and Common Rosefinch (comros). These species were chosen based on the clarity of their vocalizations and their representation within the dataset, ensuring sufficient diversity and complexity for the classification task.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of data augmentation techniques can effectively enhance classification performance26. However, the development and exploration of such methods are beyond the scope of this work. Similar to the work of Evangelista et al.27, in this study, each original audio sample was segmented into fixed-length clips of 5 s to augment the dataset and standardize the input size for the model.

Nevertheless, due to the inherent variability in the original recording durations, the final number of samples per class was not uniform. For species with abundant recordings, we randomly retained 3000 generated samples to maintain balance and prevent overrepresentation. For species with fewer available recordings, all generated samples were preserved. The final distribution of samples across the selected bird species is summarized in Table 1. This preprocessing strategy ensures that the dataset remains sufficiently large and diverse while controlling for extreme class imbalance, which is critical for reliable model training and evaluation.

Model setup and implementation details

All models were implemented using PyTorch 3.12, and training was conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4060 GPU (8GB). The proposed DLoGNet was constructed by stacking five directional convolutional modules, each containing four learnable orientation-specific kernels, followed by a global average pooling layer and a fully connected classifier. The activation function used throughout the network was ReLU, and batch normalization was applied after each convolutional block to improve training stability.

As input, we used the proposed FBRS, which was generated from 5-s audio segments sampled at 32 kHz. The FBRS was resized to a fixed resolution of 128 × 128 before being fed into the network. All comparison models were trained using the same input representation and under identical hyperparameter settings for a fair comparison. We trained each model using the cross-entropy loss function, optimized with the Adam optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 0.0001, and a learning rate scheduler with a decay factor of 0.9 was applied every 10 epochs. Each model was trained for 50 epochs with a batch size of 32. To avoid overfitting, we employed early stopping based on the validation set accuracy.

To evaluate model performance, we adopted the following four commonly used metrics: (1) Accuracy rate (AR): the proportion of correctly classified samples among all test samples. (2) Precision rate (PR): the ratio of true positives to the sum of true and false positives, averaged over all classes. (3) Recall rate (RR): the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives, averaged across classes. (4) F1-Score (F1S): the harmonic means of precision and recall, providing a balanced evaluation of both false positives and false negatives.

where TP, FN, TN and FP represent true positive, false negative, true negative and false positive respectively.

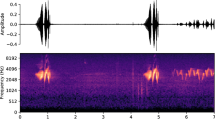

Part I: signal time-frequency analysis

All time-frequency analyses in this study were conducted using MATLAB software. Taking the sample XC134349 from the barswa (Barn Swallow) category as an example, Fig. 1 illustrates the waveform (time-domain) and its corresponding frequency spectrum (frequency-domain) within the first 5 s. In the time domain, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 1, the signal exhibits a series of intermittent amplitude modulations, with relatively low energy at the beginning and gradually increasing towards the later stages. This pattern is characteristic of natural bird vocalizations, where sequences of chirps or syllables are produced at varying intensities. In the frequency domain, depicted in the right panel of Fig. 1, the energy distribution is predominantly concentrated within the range of 0–8 kHz, with a notable peak around 3–5 kHz. The spectral amplitude decreases rapidly beyond 8 kHz, and negligible energy is observed above 10 kHz.

To select the appropriate number of decomposition levels L, we conducted experiments with L = 6, 7, 8, 9. Figure 2 illustrates the FBRS results under different values of L, while Table 2 presents the corresponding classification accuracy using DLoGNet. The results indicate that while performance slightly improves with higher decomposition levels, the accuracy gains tend to saturate at L = 8. Considering both recognition performance and computational complexity, we selected L = 8 for this study.

Figure 3 presents a visual comparison between the traditional STFT (Fig. 3a), CQT (Fig. 3b) and Mel-Frequency Spectrogram (MFS)28 (Fig. 3c) representation commonly used in bird sound analysis and the proposed FBRS (Fig. 3d). STFT and CQT can hardly characterize valid information, the energy in the former cannot be focused, resulting in poor frequency localization, while the latter is limited by the filter distribution to show only limited time-frequency information. The MFS captures the general time-frequency structure of the bird vocalizations. However, several limitations are evident: the overall contrast between signal and background is relatively low, the energy distribution across different frequency bands appears blurred, and fine-grained structures (such as the harmonic stacks and rapid frequency modulations typical of bird calls) are not distinctly highlighted. This could potentially hinder the ability of deep learning models to extract meaningful discriminative features.

In contrast, the FBRS representation in Fig. 3d demonstrates several clear advantages. First, the background noise is substantially suppressed, resulting in a higher signal-to-noise ratio. The vocal elements, especially in the 1–8 kHz range where most bird sounds are concentrated, appear more distinct and sharply defined. Second, the energy patterns across different frequency bands are better separated and enhanced, allowing for finer localization of salient acoustic events. Third, FBRS maintains a better balance between time and frequency resolution, preserving both the temporal continuity and the spectral richness of the signal. Overall, the FBRS offers a more informative and cleaner input representation, which is expected to facilitate more effective feature extraction and classification by downstream neural networks. These improvements highlight the potential of FBRS to serve as a superior alternative to conventional MFS-based inputs in bird sound recognition tasks.

To further validate the superiority of the proposed FBRS, we conducted comparative experiments using two different network architectures: a standard 5-layer CNN29 and the proposed DLoGNet. For each architecture, we evaluated the classification performance using both the traditional MFS representation and the FBRS as input features. The corresponding recognition accuracies are summarized in Table 3. When using the standard CNN, the recognition accuracy with MFS inputs is 85.09%. When the input is replaced by FBRS, the accuracy improves to 87.82%, representing a notable increase of 2.73%. Similarly, for the DLoGNet, the recognition accuracy rises from 87.40% with MFS to 91.18% with FBRS, yielding an improvement of 3.78%. We also observed that DLoGNet exhibits a consistent performance advantage over CNN even when using the conventional Mel spectrogram (MFS) as input, achieving an accuracy of 87.40% compared to 85.09%. However, the performance under MFS input remains inferior to that of other state-of-the-art models reported in Table 4. This indicates that the full benefit of DLoGNet is only realized when paired with a more informative representation such as FBRS, which better complements its directional and multi-scale feature extraction capabilities.

Figure 4 illustrates the two-dimensional t-SNE projections of the learned high-dimensional representations extracted from the fully connected layers of CNN and DLoGNet under different input conditions. In Fig. 4c, the CNN model exhibits noticeable class overlap and irregular dispersion. Several categories (e.g., Class 0, Class 1, and Class 4) are highly entangled, indicating that CNN struggles to generate distinctly separable feature embeddings even with FBRS. In contrast, Fig. 4d reveals a significantly improved separation between classes in the DLoGNet feature space. Most clusters (e.g., Class 2, Class 3, and Class 6) form compact and clearly delineated regions, while the inter-class boundaries are more pronounced. This suggests that the directional filters and frequency-sensitive architecture of DLoGNet enable more discriminative and geometrically meaningful representations. Notably, even those classes that were previously entangled in CNN (such as Class 0 and Class 4) become more distinguishable under DLoGNet. To further clarify whether these improvements are attributed to the model structure or the input representation, we included Fig. 4a, b, which visualize CNN and DLoGNet with MFS input. A comparison between (a) and (c), and (b) and (d), demonstrates that the FBRS input improves clustering quality for both models, indicating its contribution to better frequency-localized representations. However, the performance gains are even more prominent when DLoGNet is used, underscoring the importance of directional feature extraction.

These consistent performance gains across both shallow and deep architectures highlight the effectiveness of FBRS in providing cleaner and more discriminative feature representations. In particular, the improvements are more pronounced in the DLoGNet, which is specifically designed to capture directional and structural features. This suggests that the enhanced signal clarity and frequency band separation provided by FBRS can be more effectively exploited by architectures that emphasize local and orientation-sensitive feature extraction. Overall, these experimental results demonstrate that FBRS not only improves baseline classification performance but also enhances the ability of more advanced models like DLoGNet to realize their full potential in bird sound recognition tasks.

Part II: analysis of proposed model superiority

In this subsection, we conduct a comprehensive set of comparative experiments to evaluate the performance of our proposed DLoGNet model against a variety of well-established baseline and competitive models. The selected models include: (1) CNN29: a standard convolutional neural network commonly used for time-frequency audio classification tasks. (2) LSTM30: a recurrent neural network architecture capable of capturing temporal dependencies in sequential data. (3) CNN-LSTM31: a hybrid model that combines the spatial feature extraction ability of CNNs with the temporal modeling capacity of LSTMs. (4) EfficientNet32: a lightweight and scalable convolutional model known for its efficient parameter usage and competitive performance across image-based tasks. (5) VGG-1633: a deep CNN architecture with uniform convolutional layers, frequently used as a strong baseline in audio and image classification. (6) Transformer34: a self-attention-based model that captures global context and long-range dependencies, increasingly popular in audio analysis tasks. (7) MDF-Net35: a recent network architecture designed for fine-grained acoustic pattern learning, particularly in bioacoustic or environmental sound classification tasks.

Figure 5 presents FBRS spectrograms for eight representative bird species. The results demonstrate that FBRS adaptively highlights distinct acoustic patterns in each species, for instance, broadband chirps, tonal syllables, or harmonic bands, while maintaining a coherent structure across samples. This species-aware adaptivity reflects the ecological and perceptual diversity of bird calls, and enhances feature discriminability. These FBRS will be used as inputs to each of the competition models. All models were trained and evaluated under the same experimental settings for a fair comparison, including identical input features, training procedures, and evaluation metrics. The four primary metrics used for performance assessment are AR, PR, RR, and F1-S. The experimental results are presented in Table 4.

DLoGNet achieves the highest overall performance, tying with the Transformer in terms of AR and F1-Score (91.18% and 91.16%, respectively), and slightly outperforming all other models in recall and precision. CNN-LSTM, VGG-16, and MDF-Net show competitive results, indicating that both temporal modeling and deep CNN-based structures are effective for bird sound classification. The Transformer model, although non-convolutional, performs on par with DLoGNet, validating the strength of self-attention in handling sequential acoustic patterns. Standard CNN and LSTM models achieve relatively lower performance, which highlights the limitations of using either spatial or temporal modeling in isolation. The consistently high performance of DLoGNet across all metrics demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed directional and interpretable convolutional architecture in capturing structured acoustic features relevant for bird vocalization classification. These results collectively emphasize the utility of DLoGNet as a robust and interpretable solution for fine-grained acoustic recognition tasks, outperforming or matching even state-of-the-art architectures across all major evaluation criteria.

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrices of all models evaluated in this study. These visualizations offer detailed insight into how each model performs across the eight bird species, beyond aggregate accuracy metrics. Among all models, DLoGNet (Fig. 6a) shows the most distinctive diagonal dominance, indicating a strong alignment between predicted and actual classes. Misclassifications are minimal, and even in classes that are acoustically similar (such as class 3 and class 7), DLoGNet demonstrates excellent separation. For example, in class 5 and class 6, which exhibit overlapping frequency patterns, DLoGNet reduces confusion significantly compared to other models. This highlights its capacity to extract localized directional cues and structural patterns in bird vocalizations, thanks to the integration of directional LoG kernels. Furthermore, the model appears robust not only in identifying distinct species but also in maintaining stability across classes with relatively low inter-class variance.

In contrast, the standard CNN and LSTM models (Fig. 6b, c) exhibit more dispersed misclassifications, especially in acoustically dense regions such as classes 4–6. Their reliance on either purely spatial (CNN) or temporal (LSTM) features limits their ability to resolve fine-grained spectral differences. The CNN-LSTM hybrid model (Fig. 6d) improves upon its component networks by reducing confusion in several classes, yet still falls short of DLoGNet’s consistency and precision. EfficientNet and VGG-16 (Fig. 6e, f), while achieving relatively high accuracy, exhibit moderate confusion in classes with subtle vocal differences. This suggests that deeper or more parameter-efficient CNNs alone may not fully capture the directional properties of bird sounds. Transformer and MDF-Net (Fig. 6g, h) both show strong performance, with confusion matrices that resemble DLoGNet’s in clarity. However, DLoGNet matches or exceeds their classification precision with a more interpretable and specialized architecture tailored for structured acoustic signals.

To further investigate the behavior and internal mechanisms of the proposed DLoGNet, we visualized the learned parameters θ (orientation) and σ (scale) from each directional LoG convolutional layer. Table 5 summarizes the values of the four directional angles (θ1 to θ4) and the corresponding scale parameter σ. Across all layers, the θ values are distributed approximately around the canonical orientations of 0, \(\pi /4\), \(\pi /2\), and \(3\pi /4\), with slight variations induced by data-driven learning. This indicates that although the network was initialized with standard directions, it effectively fine-tuned the orientation parameters to better align with the dominant edge or structure directions present in bird vocalization spectrograms. Notably, θ1 in deeper layers (e.g., DLoG-4 and DLoG-5) deviates slightly from 0, suggesting that even low-frequency directional filters are adjusted to capture nuanced diagonal trends. The mid-range θ values (e.g., θ2 ≈ 0.77, θ3 ≈ 1.56) remain relatively stable across layers DLoG-2 to DLoG-4, indicating consistent detection of oblique patterns throughout the hierarchy. These directions likely correspond to typical ascending or descending chirp trajectories in bird sound spectrograms. The scale parameter σ shows a clear increasing trend from DLoG-1 (1.2955) to DLoG-4 (1.4161), suggesting that higher layers tend to learn broader receptive fields. This is consistent with the hierarchical nature of deep networks, where deeper layers are expected to capture more abstract, large-scale patterns. Interestingly, DLoG-5 exhibits a slight decrease in σ, potentially reflecting a refinement stage that re-focuses on mid-scale frequency modulations. To evaluate the consistency of the learned orientation and scale parameters, we repeated the training process five times under identical settings but with different random seeds. Figure 7 shows the parameter values of the final DLoG layer. The results indicate that while minor fluctuations occur, the directional spread (θ1 to θ4) and scale σ values remain highly stable across runs, supporting the reproducibility of the interpretability-related features.

Figure 8 visualizes the convolutional responses from the first DLoG layer, corresponding to four learnable orientations. Each subfigure represents the output feature map generated by one of the four DLoG kernels when convolved with a spectrogram input. As shown in the figure, each directional filter produces distinct activation patterns, highlighting different structural aspects of the bird vocalization signal: (1) Top-left (Direction ~0°): the filter emphasizes vertical structures, such as sharp onset harmonics or sudden changes in frequency. These features often correspond to transient events or tone bursts typical of chirps or short calls. (2) Top-right (Direction ~45°): the convolution output captures diagonal upward trends, which align well with ascending frequency modulations frequently observed in species with gliding or rising syllable trajectories. (3) Bottom-left (Direction ~90°): this orientation highlights horizontal components and smoother frequency bands. It is particularly responsive to steady or slowly varying tonal segments, capturing the sustained portions of bird calls. (4) Bottom-right (Direction ~135°): the filter reacts to downward-sloping patterns, effectively detecting descending chirps or harmonic decays. These patterns are especially important for distinguishing certain species with descending syllabic contours. Importantly, the outputs reveal that each DLoG kernel focuses on a distinct directional structure in the spectrogram, allowing the model to comprehensively encode orientation-specific information. This behavior closely mirrors the principles of biological vision systems, where orientation-selective neurons in early visual cortices play a critical role in edge detection.

Each subplot shows the response of a directional DLoG kernel to a bird spectrogram input: a ~0°, highlighting vertical structures; b ~45°, capturing ascending modulations; c ~90°, enhancing horizontal harmonics; and d ~135°, detecting descending contours. The filters demonstrate distinct sensitivity to orientation-specific acoustic patterns.

To further illustrate how the network makes classification decisions, we present Grad-CAM visualizations for CNN, VGG-16, and DLoGNet in Fig. 9. The heatmaps reveal that DLoGNet focuses on coherent spectral structures that align with characteristic vocal patterns, such as chirps or harmonics, whereas CNN and VGG-16 exhibit more dispersed or less interpretable attention. This result highlights the decision transparency and structural awareness enabled by the directional convolution mechanism in DLoGNet. These interpretability tools allow us to qualitatively assess whether the model focuses on spectrotemporal regions that are biologically meaningful for species identification, such as stable harmonics or high-energy burst segments.

Discussion

In this study, we introduced a novel deep learning framework for bird sound recognition that combines multi-scale texture modeling with interpretable architecture design. Specifically, the proposed DLoGNet incorporates DLoG convolutions, enabling the network to extract orientation- and scale-sensitive features from time-frequency representations. Complementing this, we developed the FBRS, which adaptively highlights informative spectral bands based on energy distribution from wavelet packet decomposition. Extensive quantitative experiments validate the effectiveness of our approach. Compared with baseline models, DLoGNet with FBRS input achieved the highest classification accuracy of 91.18%, outperforming CNN (87.82%), LSTM (87.64%), CNN-LSTM (90.41%), and EfficientNet (89.82%). Additionally, DLoGNet demonstrated competitive or superior performance compared to VGG-16 (90.52%), Transformer (91.18%), and MDF-Net (91.16%) across multiple metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score. Furthermore, t-SNE visualizations of feature embeddings confirmed that DLoGNet learns more compact and separable clusters across classes, while convolutional output maps illustrated the directional selectivity and layer-wise feature refinement achieved through DLoG filters. The learned parameters (θ, σ) showed consistent multi-scale behavior, reinforcing the model’s capability for hierarchical texture extraction.

The experimental results and visual analyses presented in the preceding sections demonstrate the effectiveness and interpretability of the proposed DLoGNet architecture for bird sound classification. By integrating DLoG kernels into a deep learning framework, DLoGNet achieves competitive performance across multiple evaluation metrics while simultaneously offering transparent and functionally grounded feature representations. The model not only performs well in quantitative terms but also exhibits meaningful behavior in parameter visualization and convolutional feature mapping, making it more trustworthy for use in ecological monitoring applications.

Nevertheless, some limitations remain. First, while the directional and scale parameters enhance model flexibility, they introduce additional computational overhead compared to standard CNNs. Future work could explore parameter-sharing strategies or efficient kernel approximations to reduce the model’s runtime complexity. Second, the current framework relies heavily on time-frequency representations as inputs, which may not fully preserve the raw waveform characteristics or temporal dynamics. End-to-end extensions that learn directly from raw audio or combine time-frequency and waveform features may further enhance performance and generalizability. Although the model’s interpretability is demonstrated through visualization techniques, future work will involve collaboration with ornithologists to evaluate whether the attention patterns and frequency emphases identified by the model align with biologically and behaviorally significant features of bird vocalizations.

Methods

General framework

Figure 10 presents the overall framework of our proposed intelligent bird sound recognition system. The pipeline begins with acoustic signal collection, where real-world bird vocalizations are recorded using mobile or field devices. These raw audio signals are then forwarded to an intelligent signal processing platform, which forms the core of the system.

Within this platform, the signals undergo time-frequency transformation, producing spectrogram representations that capture both temporal and spectral characteristics. The transformed features are subsequently passed through a specialized deep neural network for feature extraction and classification. The system outputs the identified bird species, which can be displayed in real time on user devices. Beyond real-time identification, the platform also supports expert-guided analysis and model refinement. Experts can examine model outputs and intermediate feature maps to gain biological or acoustic insights. Meanwhile, researchers and developers can use these insights to iteratively improve the network architecture, thereby enabling a feedback-driven model optimization loop.

More interpretive time-frequency analysis

Bird vocalizations are inherently nonstationary signals, exhibiting rapid modulations, temporal discontinuities, and energy concentration in specific frequency bands. These properties make time-frequency representations more suitable than raw waveforms for modeling such signals. In this study, we propose a novel representation, which builds upon wavelet packet decomposition (WPD) and incorporates perceptually guided, energy-driven sub-band selection. Unlike standard WPD applications, FBRS is tailored to the acoustic structure of bird calls, adaptively retaining only the most ecologically meaningful frequency components. The computational flowchart and pseudo-code are shown in Figs. 11 and 12.

Given an input signal x(t), we first decompose it using an L-level wavelet packet tree. Each node in the decomposition corresponds to a sub-band with fixed frequency resolution. For any wavelet packet series \({D}_{J}x(t)\), it can be decomposed into the orthogonal sum of the following WPD components according to Eq. (5).

where \({w}_{n}\in {L}^{2}(R),n > 0\), it can be defined as follows:

where \({w}_{0}=\varphi (t)\) (scale function), \({w}_{1}=\psi (t)\) (wavelet function).

For each terminal node, we define its energy as:

where \({x}^{k,m}(i)\) denotes the discrete signal of the subspace signal \({x}_{{2}^{k}+m}\). The normalized energy is then computed as:

This normalization ensures fair comparison across bands. Subsequently, we sort the energy values in descending order to identify the most relevant sub-bands:

where \(sort(\cdot )\) represents the descending sorting operator.

Due to the hierarchical nature of wavelet packet trees, two sibling nodes (e.g., node 10 and node 11) must be processed jointly. This “symbiotic constraint” ensures the completeness of inverse reconstruction. When a child node is selected based on energy, its sibling is simultaneously paired to form a full-band filter, and their parent is marked as consumed. As shown in Fig. 11, the iterative procedure involves: (1) Selecting the most energetic node-pair; (2) Reconstructing their parent signal; and (3) Updating the filter frequency resolution accordingly. Let the minimum frequency resolution after decomposition be:

where \({f}_{s}\) is the sampling rate. After each iteration, the active node set is updated, and filters \({H}_{1}(f),{H}_{2}(f)\)… are formed. The maximum number of iterations is strictly less than L, improving computational efficiency.

Once the signal is passed through the constructed adaptive filter bank \(\{{H}_{i}(f)\}\), we compute the frequency-domain energy response:

where \(P(k)\) is the power spectrum matrix of the input signal.

The logarithmic amplitude spectrum compresses the dynamic range of the frequency-domain signals, equalizes the amplitude differences in the frequency bands, and also improves the computational stability. The final FBRS is calculated as follows:

The advantages over uniform presentation can be summarized as follows: (1) Weighting of irrelevant or low-energy bands is discarded or reduced. (2) Band selection follows the actual energy structure of the signal rather than a fixed frequency partition. (3) Each filter can be traced back to a wavelet packet node, allowing one to understand the structure of the resulting spectrogram from a physical point of view. In this study, the wavelet packet decomposition for FBRS construction is performed using the Daubechies 16 (db16) wavelet, with the number of decomposition levels L set to 8. This setting provides a fine-grained spectral resolution and has shown reliable performance across diverse bird vocalization patterns.

Deep learning model with more transparency

CNNs are widely used for time-frequency analysis in audio classification, learning local patterns related to energy, rhythm, and frequency transitions. However, standard convolutional kernels are primarily sensitive to intensity, limiting their ability to capture structural or directional features. To overcome this, we propose the DLoGNet, which replaces conventional filters with DLoG kernels that respond to oriented curvature and frequency-edge structures, enabling both functional specificity and interpretability.

The Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG)36 function is a classical image processing operator used for blob detection and edge enhancement. It is defined as the second spatial derivative of a Gaussian-smoothed signal:

where \(G(x,y;\sigma )\) is a two-dimensional Gaussian function defined as:

Combining the 2 equations above gives the full expression:

Although the standard LoG performs well in edge detection, its isotropic property (i.e., responds equally to all directions) leads to limitations in capturing structural changes in specific directions36. For this reason, a directional derivative version of LoG is proposed in this paper, which makes the filter more sensitive to gray scale changes in a specified direction by introducing a second-order derivative operator in any direction. Let the direction vector be:

Then the second order derivative along the direction \(n\) can be expressed as:

where \({H}_{G}\) is the Hessian matrix of the Gaussian function:

In summary, the following equation is obtained:

A schematic comparison of LOG and DLOG is given in Fig. 13. The DLoG proposed in this paper achieves sensitive enhancement of structural changes in images in any direction by introducing a controllable direction second-order derivative operator based on standard Gaussian smoothing. The method not only possesses good theoretical interpretability, but also enhances the feature extraction capability in the form of low parametric quantities in deep neural networks, which is particularly suitable for the recognition task of directional structures such as edges, patches, and line textures.

More importantly for DLoG, the angle \(\theta\) and scale \(\sigma\) parameters can be set as learnable parameters in the neural network, so that the model can adapt to the optimal direction and scale during the training process to improve the feature expression ability and model performance. During the training process of the neural network, according to the chain derivation law, \(\sigma\) and \(\theta\) are updated as follows:

where lr is the learning rate.

In the proposed DLoG, the kernel is fully differentiable with respect to both the orientation angle \(\theta\) and the scale \(\sigma\) parameter. The derivatives are explicitly formulated, enabling end-to-end learning of directional and scale-sensitive features. The partial derivatives of \(\sigma\) and \(\theta\) in DLOG can be expressed as follows:

Bird vocalization spectrograms often contain curved and sloped structures that correspond to pitch changes, syllable contours, or harmonic transitions. Standard convolutional kernels are isotropic and cannot distinguish between horizontal, vertical, or diagonal patterns. As shown in Fig. 14, in contrast, the proposed Directional LoG filters act like specialized “acoustic edge detectors” that can highlight frequency rising patterns (e.g., ascending chirps), falling contours (e.g., glides or descents), and even horizontal harmonics. By learning the optimal direction (θ) and scale (σ), the model can adaptively focus on the spectral geometries most relevant to species identification.

Based on the directional sensitivity and scale-adaptive properties of the DLoG kernel, we propose a novel network architecture, termed DLoGNet, for feature extraction and classification tasks. The DLoGNet is constructed by sequentially stacking multiple basic DLoG convolution modules (BDCMs) to form a deep hierarchy of directional and scale-aware feature representations, followed by a fully connected classifier for decision making.

The structure of BDCM is illustrated in Fig. 15. Each BDCM consists of four directional branches, corresponding to initial angles of 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°. These angles are not fixed, rather, they are learnable parameters that are optimized during training, allowing the network to dynamically adapt to the most discriminative orientations in the data. In each branch, the input feature map X is first processed by a DLoG kernel with a learnable orientation θ and scale σ, formulated as:

Subsequently, multiple DLoG features with different orientations are spliced to form multiscale texture features, and to reduce the risk of losing important low-frequency information during directional convolution, we introduce a skip connection that concatenates the input feature map with the directional DLoG outputs before further processing. This residual concatenation helps preserve fundamental acoustic components and enriches the combined representation by retaining both unfiltered and directionally enhanced structures.

After processing through all directional branches, a standard 3×3 convolution is applied to the DLoG features to enhance local context modeling and nonlinearity. The final output Y is as follows:

The overall architecture of DLoGNet consists of five consecutive BDCMs, each responsible for progressively capturing higher-level structural patterns in the input signal. The structure and parameters of the DLoGNet used in this study are given in Table 6. Mathematically, the output of the i-th DLoG convolution module can be represented as:

After passing through the DLoG convolutional stack, the final feature map \({Y}_{5}\) is globally pooled and fed into a fully connected (FC) layer for classification:

The predicted class probabilities are then obtained by applying the softmax function:

The complete DLoGNet thus embodies two key principles: (1) Progressive directional feature extraction through a deep hierarchy of learnable DLoG filters. (2) End-to-end learning of orientation and scale parameters (θ, σ) alongside classification weights, allowing the network to adaptively emphasize semantically relevant structures.

The overall training objective is to minimize the standard cross-entropy loss between predicted and true labels:

where C is the number of target classes, \({y}_{c}\) is the ground truth label, and \({\hat{y}}_{c}\) is the predicted probability for class c.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Zhang, L., Towsey, M., Xie, J., Zhang, J. & Roe, P. Using multi-label classification for acoustic pattern detection and assisting bird species surveys. Appl. Acoust. 110, 91–98 (2016).

Clark, M. L. et al. The effect of soundscape composition on bird vocalization classification in a citizen science biodiversity monitoring project. Ecol. Inform. 75, 102065 (2023).

Stein, R. C. Modulation in bird sounds. Auk 85, 229–243 (1968).

Dooling, R. J. & Prior, N. H. Do we hear what birds hear in birdsong?. Anim. Behav. 124, 283–289 (2017).

Beckers, G. J., Suthers, R. A. & Cate, C. T. Mechanisms of frequency and amplitude modulation in ring dove song. J. Exp. Biol. 206, 1833–1843 (2003).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Xie, J., Zhang, J. & Zhu, R. DFEFM: fusing frequency correlation and mel features for robust edge bird audio detection. Avian Res. 16, 100232 (2025).

Zottesso, R. H., Costa, Y. M., Bertolini, D. & Oliveira, L. E. Bird species identification using spectrogram and dissimilarity approach. Ecol. Inform. 48, 187–197 (2018).

Xie, J. & Zhu, M. Handcrafted features and late fusion with deep learning for bird sound classification. Ecol. Inform. 52, 74–81 (2019).

Rai, P., Golchha, V., Srivastava, A., Vyas, G. & Mishra, S. In 2016 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT) 1–5 (IEEE, 2016).

Revathi, A. & Sasikaladevi, N. Robust sound-based bird classification using multiple features and random forest classifier. Int. J. Speech Technol 28, 117–127 (2025).

Vaca-Castano, G. & Rodriguez, D. In 2010 IEEE Workshop on Signal Processing Systems 466–471 (IEEE, 2010).

Han, X. & Peng, J. Bird sound classification based on ECOC-SVM. Appl. Acoust. 204, 109245 (2023).

Priyadarshani, N., Marsland, S. & Castro, I. Automated birdsong recognition in complex acoustic environments: a review. J. Avian Biol. 49, jav-01447 (2018).

Campos-Cerqueira, M. et al. A pipeline for identification of bird and frog species in tropical soundscape recordings using aconvolutional neural network[J]. Ecological Informatics 59, 101113 (2020).

Gupta, G., Kshirsagar, M., Zhong, M., Gholami, S. & Ferres, J. L. Comparing recurrent convolutional neural networks for large scale bird species classification. Sci. Rep. 11, 17085 (2021).

Adavanne, S., Drossos, K., Çakir, E. & Virtanen, T. In 2017 25th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO) 1729–1733 (IEEE, 2017).

Tang, Q., Xu, L., Zheng, B. & He, C. Transound: Hyper-head attention transformer for birds sound recognition. Ecol. Inform. 75, 102001 (2023).

Noumida, A. & Rajan, R. Multi-label bird species classification from audio recordings using attention framework. Appl. Acoust. 197, 108901 (2022).

Das, N., Mondal, A., Chaki, J., Padhy, N. & Dey, N. Machine learning models for bird species recognition based on vocalization: a succinct review. 117–124 (Information Technology and Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2020).

Heinrich, R., Rauch, L., Sick, B. & Scholz, C. AudioProtoPNet: an interpretable deep learning model for bird sound classification. Ecol. Inform. 87, 103081 (2025).

Gao, L. & Guan, L. Interpretability of machine learning: recent advances and future prospects. IEEE Multimed. 30, 105–118 (2023).

Lin, C., Hsiung, W. & Liu, M. In 2016 39th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP) 319–322 (IEEE, 2016).

Pahuja, R. & Kumar, A. Sound-spectrogram based automatic bird species recognition using MLP classifier. Appl. Acoust. 180, 108077 (2021).

Permana, S. D. H. & Bintoro, K. B. Y. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite (COMNETSAT) 52–56 (IEEE, 2021).

Hsu, S.-B., Lee, C.-H., Chang, P.-C., Han, C.-C. & Fan, K.-C. Local wavelet acoustic pattern: a novel time–frequency descriptor for birdsong recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 20, 3187–3199 (2018).

Moreno-Barea, F. J., Jerez, J. M. & Franco, L. Improving classification accuracy using data augmentation on small data sets. Expert Syst. Appl. 161, 113696 (2020).

Evangelista, T. L., Priolli, T. M., Silla, C. N., Angelico, B. A. & Kaestner, C. A. In 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia 223–228 (IEEE, 2014).

Hu, S. et al. Deep learning bird song recognition based on MFF-ScSEnet. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110844 (2023).

Indumathi, C., Diviyalakshmi, K. & Mahalakshmi, R. Bird sound identification system using deep learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 233, 597–603 (2024).

Umarani, M., Meyyappan, S., Vallathan, G. & Karthi, G. In 2024 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Green and Sustainable Technologies (ICCIGST) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Wang, X., Ren, C., Yu, T. & He, S. in 2023 38th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC) 576–581 (IEEE, 2023).

Ansar, W., Chatterjee, A., Goswami, S. & Chakrabarti, A. An EfficientNet-based ensemble for bird-call recognition with enhanced noise reduction. SN Comput. Sci. 5, 265 (2024).

Bhatlawande S, Khire N, Kinge M, et al. Scene recognition and image caption generation[C]. In AIP Conference Proceedings. 2754, 160003 (AIP Publishing LLC, 2023).

Zhang, S. et al. A novel bird sound recognition method based on multifeature fusion and a transformer encoder. Sensors 23, 8099 (2023).

Xie, S. et al. MDF-Net: a multi-view dual-attention fusion network for efficient bird sound classification. Appl. Acoust. 225, 110138 (2024).

Gunn, S. R. On the discrete representation of the Laplacian of Gaussian. Pattern Recognit. 32, 1463–1472 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This research was partly supported by China Scholarship Council (Nos. 202406280198 and 202406280271).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both R.Q. and J.H. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript, with R.Q. focusing on the implementation of the code and J.H. on the collection and analysis of data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, R., Huang, J. Towards accurate bird sound recognition through multi-scale texture-aware modeling. npj Acoust. 1, 22 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00025-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00025-6