Abstract

Multimodal artificial intelligence (MMAI) is redefining oncology by integrating heterogeneous datasets from diagnostic modalities into cohesive analytical frameworks for more accurate and personalized cancer care. We highlight MMAI applications across the patient journey and clinical research, discuss outstanding challenges, and the need for guidelines and regulatory frameworks. By converting multimodal complexity into clinically actionable insights, MMAI is poised to improve patient outcomes while reshaping the economics of global cancer care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

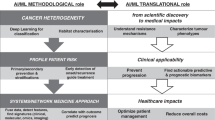

Cancer manifests across multiple biological scales, from molecular alterations and cellular morphology to tissue organization and clinical phenotype. Predictive models that rely on a single data modality fail to capture multiscale heterogeneity, limiting their ability to generalize our understanding across patient populations. Multimodal artificial intelligence (MMAI) approaches integrate information from diverse sources, including cancer multiomics, histopathology, clinical records, and others, enabling models to exploit biologically meaningful inter-scale relationships (Fig. 1)1.

MMAI approaches enhance predictive accuracy and robustness by contextualizing molecular features within anatomical and clinical frameworks, yielding a more comprehensive representation of disease. Such models are more likely to support mechanistically plausible inferences, improving interpretability and clinical relevance2,3. MMAI presents an opportunity to advance cancer management, from prevention and early, accurate diagnosis to prognosis, treatment selection, and outcome assessment (Fig. 2)1.

As artificial intelligence (AI) models become increasingly integral to the cancer care continuum, rigorous evaluation of their transformative potential, implementation barriers, and future directions is imperative. Here, we highlight clinical applications of MMAI, including examples of pioneering clinical research in personalized oncology care, as well as ethical and practical considerations for widespread implementation of MMAI.

Prevention and early detection

Personalized prevention strategies

AI facilitates personalized disease prevention by identifying high-risk individuals and recommending tailored lifestyle measures, from neurodegenerative and infectious diseases to oncology4. For example, epidemiological MMAI models from the UK Biobank integrated clinical, lifestyle, and polygenic risk variables to identify cardiovascular disease among patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (area under the receiver operating curve [ROC–AUC] 0.85)5. Additionally, MMAI models integrating clinical and demographic variables identified patients with onco-hematological diseases who are likely to develop severe COVID-19, offering an opportunity for additional prevention strategies6.

These examples highlight the potential of epidemiological MMAI models to analyze population health data to predict disease risk factors and suggest targeted patient monitoring and chemoprevention strategies.

Screening and risk stratification

MMAI-based predictive capabilities have enabled targeted screening and risk stratification, allowing earlier intervention that may improve patient outcomes. MMAI algorithms can stratify cancer risk at various stages of the patient care pathway. A study of >5000 patients showed machine learning models, using clinical metadata, mammography, and trimodal ultrasound, were similar or better at predicting breast cancer risk compared with pathologist-level assessments7. Models such as Sybil AI demonstrated up to 0.92 ROC–AUC in predicting lung cancer risk from low-dose computed tomography (CT) scans, and could be incorporated into CT screening programs without disruption to current clinical workflows8. Given their potential, multimodal screening programs are needed to ensure external validity and equitable applicability. Project MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI), co-founded by Nvidia, is an open-source, PyTorch-based framework providing a comprehensive suite of AI tools and pre-trained models for medical imaging applications9. In breast cancer screening, MONAI-based models enable precise delineation of the breast area in digital mammograms, improving both accuracy and efficiency of breast cancer screening programs10. For ovarian cancer, deep learning models developed with MONAI enhance diagnostic accuracy on CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans11. In lung cancer, MONAI facilitates the integration of radiomics and patient demographic data within deep learning models, leading to improved risk assessment and screening outcome accuracy compared with Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) classification12.

AI-enhanced early detection

Deep learning models can enhance the sensitivity of cancer screening and early detection programs by detecting subtle tumor features on medical imaging. In a meta-analysis, AI-guided colonoscopy increased adenoma detection rate by ~10%13, and emerging AI-assisted liquid biopsy models are able to identify cell-free DNA (cfDNA), potentially revolutionizing non-invasive early detection14,15.

Following early detection, timely and accurate diagnosis are needed to optimize treatment plans; integration of AI tools into clinical workflows is therefore being explored in primary care for early identification of patients with lung and ovarian cancers16.

Diagnosis and prognosis

AI diagnosis in pathology and radiology

In digital pathology, numerous AI-assisted diagnostic approaches have been published, a meta-analysis of which achieved 96.3% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity across common tumor-type classifiers17. Furthermore, lightweight architectures, such as ShuffleNet, can infer genomic alterations directly from histology slides (ROC–AUC 0.89), reducing turnaround time and cost of targeted sequencing across solid tumors18.

AI-powered imaging systems enhance tumor detection, lesion characterization, and disease staging. In radiology, multiple US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved AI applications now assist in identifying breast lesions on mammograms and pulmonary nodules on CT scans19,20. When combined with clinical metadata in multimodal models, prognostic accuracy and survival prediction improve further, as demonstrated by F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography images in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)21.

Prognosis and outcome prediction

MMAI can integrate imaging, histology, genomics, and other biomarker and clinical data to forecast progression and therapy response. Stanford’s MUSK, a transformer-based AI model, achieved improved accuracy for melanoma relapse and immunotherapy response prediction (ROC–AUC 0.833 for 5-year relapse prediction) compared with existing unimodal approaches22, and Pathomic Fusion, a multimodal fusion strategy combining histology and genomics in glioma and clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma datasets, outperformed the World Health Organization 2021 classification for risk stratification23. Furthermore, a pan-tumor analysis of 15,726 patients combined multimodal real-world data and explainable AI to identify 114 key markers across 38 solid tumors, which were subsequently validated in an external lung cancer cohort24.

AstraZeneca’s ABACO, a pilot real-world evidence (RWE) platform utilizing MMAI, applies similar principles at scale to identify predictive biomarkers for targeted treatment selection, optimize therapy response predictions, and improve patient stratification in patients with hormone receptor–positive (HR+) metastatic breast cancer25. Another example is the TRIDENT machine learning multimodal model, which integrates radiomics, digital pathology, and genomics data from the Phase 3 POSEIDON study in patients with metastatic NSCLC26. These models yielded a patient signature in >50% of the population that would obtain optimal benefit from a particular treatment strategy (hazard ratio [HR] reduction: 0.88–0.56, non-squamous histology population; 0.88–0.75, intention-to-treat population)27. These advances underscore the benefit of MMAI-powered models for refining precision medicine strategies beyond current standard-of-care frameworks.

Personalized treatment and patient management

AI-driven precision oncology

In precision oncology, treatment selection is compounded by numerous small molecularly defined subgroups and an expanding arsenal of targeted therapies. Characterizing patients within these subgroups requires the integration of high-dimensional data, including hundreds of variables per patient. For instance, molecular diagnostics may assess gene mutations, copy number variations, and expression levels, while imaging data provide spatial and morphological context that reflect tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment28,29. The complexity of these multimodal datasets renders traditional decision-making tools insufficient. Thus, MMAI models can support clinicians by providing personalized treatment recommendations that consider the intricate interplay of diverse data types and therapeutic options.

Benchmarking efforts demonstrate the promise of MMAI in this space. The Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment and Methods (DREAM) drug sensitivity prediction challenge assessed the ability of AI models to predict drug response using multiomics data in breast cancer cell lines, revealing that multimodal approaches consistently outperform unimodal ones in predicting therapeutic outcomes30. In breast cancer, multimodal models based on the TransNEO, ARTemis, and PBCP studies showed that response to treatment is modulated by pre-treated tumor ecosystems31. An MMAI patient stratification model used data from five Phase 3 prostate cancer trials to predict long-term, clinically relevant outcomes, with 9.2–14.6% relative improvement compared with a validation set based on National Cancer Center Network risk stratification32. Furthermore, in metastatic NSCLC, the TRIDENT initiative identified mutational signatures of patients likely to benefit from combination treatments27.

Remote monitoring and AI-assisted symptom management

AI-powered telehealth platforms and wearable sensors may facilitate real-time patient monitoring, enabling early detection of treatment-related complications, and AI-driven chatbots can alleviate physician workload, improve patient engagement, and reduce emergency hospital visits33,34,35,36. For example, a UK pilot study using a chatbot approach to triage patients with gynecological malignancies receiving chemotherapy achieved an unscheduled emergency visit adjusted incident ratio rate of 0.3135.

AstraZeneca’s RWE platform, ABACO, incorporates MMAI into real-world continuous monitoring, linking treatment outcomes to dynamic AI-driven insights to enhance patient management25. Thus, through multimodal integration of remote patient monitoring and conventional data streams, the platform can capture complementary physiological and contextual information, thereby improving predictive performance and enabling more precise, timely clinical decision-making. This may enable oncologists to proactively adjust treatment and management plans specific to each patient, thereby minimizing adverse events.

Quality of life beyond systemic treatments

Ensuring maintenance or improvement of quality of life beyond systemic treatments is challenging to address. QUALITOP followed 1800 patients treated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T) cells, using AI models to link adverse events with health-related quality of life scores37. The recent inclusion of electronic patient-reported outcomes offers a new modality that, once integrated into the multimodal workstream, can inform patient-centered care.

Drug development and clinical research implications

AI-accelerated drug development

AI-driven drug discovery platforms (e.g., BenevolentAI) analyze large-scale molecular datasets to identify promising drug candidates38. Although the sample size is limited, AI-designed molecules are now estimated to progress to clinical trials at twice the rate of traditionally developed drugs, and early reviews suggest a success rate of 80–90% for Phase 1 clinical trials, which is substantially higher than the industry standard39. Machine learning models could expedite target identification and lead optimization, thereby significantly reducing timelines for new oncology drug development.

Enhancing clinical trial efficiency

AI optimizes clinical trial recruitment by matching patients with studies based on tumor biomarkers, improving enrollment efficiency. Eligibility‑matching engines reduce manual screening time, while real-time adaptive randomization informed by MMAI analytics reallocates patients toward superior arms earlier40,41.

The MMAI ABACO framework may facilitate patient enrichment strategies, leading to more efficient and precise drug trials based on RWE25. The TRIDENT initiative has the ability to optimize biomarker-driven patient selection and synthetic control arms, which may reduce trial costs and accelerate approvals27. These AI-driven comparator cohorts (‘digital twin’) have the potential to reduce reliance on traditional randomized control groups and are validated in chronic graft-versus-host disease42; they are also being spearheaded in rare diseases and oncology43,44.

MMAI may offer an ethical and efficient alternative in oncology, particularly for targeted therapies in rare cancers and in supporting clinical trials where patient recruitment is challenging. Overall, by integrating the synthetic control arm methodology, the clinical trial process may be further streamlined, ensuring robust regulatory submissions and improved decision-making in drug development (Fig. 3).

Boosting patient recruitment

Using AI to streamline patient recruitment into clinical trials has enabled physicians to assess and manage patients’ conditions faster. GatorTron, a large language model for electronic health records (EHRs), achieved state-of-the-art performance in early identification of patients with a potential diabetes diagnosis by extracting phenotypes for trial across 290 million clinical notes45. Trial Pathfinder, an AI algorithm developed using retrospective real-world data from 61,094 patients with advanced NSCLC, was created to simplify the exclusion and inclusion criteria of clinical trials. Evaluation of clinical trial criteria with Trial Pathfinder suggested that 17% more patients could qualify for second-line trials46.

Although challenges are expected in integrating MMAI in clinical practice, such models have great potential to enhance patient identification and support patient equity.

Benefits to the healthcare system

Data availability and curation

A persistent barrier to MMAI lies in fragmented data silos. Initiatives such as the EU Health Data Space Regulations and the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s CancerLinQ illustrate a trend toward ‘radical interoperability’ based on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) and Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) standards for large-scale analytics47,48. The TRIDENT initiative exemplifies how a well-curated Phase 3 dataset (~2.2 TB of imaging and omics [Colin, T. 2025; personal communication]) can fuel externally validated MMAI models27. Adequately regulated or federated learning frameworks may further allow algorithms to train on ‘distributed nodes’ without centralizing patient‑level data, thus preserving privacy while expanding sample diversity.

Treatment efficiency and cost-effectiveness

Escalating investment and risk-taking when developing new targeted drugs and immunotherapies make oncology one of the fastest-growing cost lines for health systems worldwide49,50. MMAI could mitigate this pressure by improving the fit between patient and therapy, shortening diagnostic turnaround times, and generating evidence that payers can use to structure value-based contracts (Fig. 4).

Interoperable data result in system‑level gains

Deploying MMAI on harmonized datasets (e.g., FHIR-OMOP standards) means that radiology, digital pathology, genomic feeds, and others are analyzed together rather than in silos. A hospital‑wide return on investment (ROI) analysis of an AI radiology platform estimated a 5‑year ROI of 451% (791% when radiologist time savings were monetized), equivalent to 145 working days of imaging workflow saved. These savings accrued to providers through resource productivity and payers through improved care and potential reduction in litigations from missed diagnoses51.

Better diagnostic capability reduces overtreatment

A proof point is provided by genomic assays in node‑negative, HR+ breast cancer: the Oncotype DX Recurrence Score spared chemotherapy for low‑risk patients and, in a UK cost‑utility model, delivered an incremental gain of 0.17 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) while reducing lifetime costs by £519 per patient52. MMAI platforms extend this principle by blending digital pathology with radiomics and clinical variables and identifying a respondent patient signature, as demonstrated by TRIDENT27, with the potential for improved QALY gains in high-benefiting patients.

Diagnostics and targeted treatment shift the cost‑effectiveness frontier

ctDNA represents an additional data layer that can be combined with clinicopathological features, digital pathology, and radiomic features to identify targeted interventions. A good example is ctDNA-guided adjuvant therapy in the DYNAMIC trial (455 patients with Stage II colon cancer), whereby a liquid biopsy minimal residual disease signal plus clinicopathological data led to a reduction in adjuvant chemotherapy use from 28% to 15% and achieved a similar 2‑year recurrence‑free survival (93.5% vs 92.4%)53. In practical terms, four patients needed to be tested to spare one from unnecessary chemotherapy and its toxicity.

The aforementioned strategies lead to superior health economic outcomes, meaning enhanced health results coupled with reduced costs. This underscores the potential for MMAI approaches to tackle the substantial challenges that healthcare systems encounter due to budget constraints, while striving to improve patient outcomes.

Payer engagement

MMAI outputs are machine-readable, version-controlled, and linked to outcomes registries and leveraged by frameworks, such as the ABACO RWE platform25. This facilitates:

-

Performance‑based agreements – payment triggers only when the algorithm‑predicted benefit is realized

-

Dynamic pricing – drug discounts tied to MMAI‑quantified responder fractions

-

Global portability – models can be federated; low‑ and middle‑income countries can adopt validated algorithms without exporting data, therefore broadening access while preserving sovereignty

Collectively, these mechanisms realign incentives toward maximizing health. Prospective medico‑economic evaluations are now a prerequisite for AI biomarkers to obtain broad reimbursement, ensuring that cost‑effectiveness is embedded from the outset54.

Health equity

We believe that consciously designed MMAI can help narrow global cancer care inequities. For example, AI-enabled telepathology services used in several sub‑Saharan countries demonstrated concordance rates of between 70% and 95% compared with traditional methods of diagnosis55. Implementation of AI-driven digital microscopy diagnostics for Papanicolaou tests to detect atypical cervical smears in resource-limited settings achieved high levels of sensitivity and specificity56, with potential to include other modalities and reduce time to treatment and outcomes. These examples are particularly relevant as they target a region with fewer than one pathologist for every 1,100,000 people57. Similar gains are reported for teleradiology networks in Southeast Asia, where AI tools for chest X-rays are mitigating radiologist shortages by enhancing diagnostic image analysis and triaging priority reporting by radiologists58.

With context‑appropriate infrastructure, AI models, and now MMAI, can further support health systems, especially in regions with limited resources. A challenge for health equity that needs addressing is the need for models to be trained in cohorts that are representative of the full population; otherwise, there is a risk of augmenting inequalities.

Challenges and future directions

AI adoption in oncology necessitates seamless integration between its development and its deployment into EHRs and clinician workflows. Ensuring transparency, explainability, regulatory compliance, and overcoming the ‘black box’ – or unknown – working mechanism by gaining clinician trust through education on AI technologies is paramount59. In the context of MMAI for clinical decision support systems (CDSS), the derivation of robust, minimal, and independent predictive signatures, rooted in biological plausibility, is indispensable for ensuring transparency, interpretability, clinical utility, and adoption.

Furthermore, ethical concerns surrounding data privacy, decentralized data sharing, and regulated/federated learning nodes, broader stakeholder involvement, and their governance demand urgently harmonized guidelines and security measures for proper scalability.

Data and regulatory framework, and stakeholder engagement

MMAI relies on extensive patient data; frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act60 focus on data privacy, ownership, and secondary use, ensuring the patient and the patient’s interests are respected. Although regulatory AI-specific guidance has been published, including the European Medicines Agency’s reflection paper on the use of AI in the medicinal product lifecycle61 and FDA’s Good Machine Learning Practice principles62, there is urgency to address scalability and geographic challenges, while facilitating a homogeneous global framework for multi-stakeholders to work toward a common goal63,64,65. We acknowledge the need for establishing collaborative platforms where researchers and industry experts, from healthcare providers to regulatory agencies, the pharmaceutical industry to governments, the technology industry and medical devices, patient groups, and policy makers, can all share findings, best practices, and case studies demonstrating AI’s benefits. Cross-stakeholder engagement is key for MMAI to thrive.

Federated learning

Federated learning is a transformative approach in healthcare, enabling the development of AI models across multiple institutions without the need to centralize sensitive patient data66,67.

Although federated learning has been explored for drug discovery, its benefits are comparatively greater and have materialized in MMAI applications for CDSS. In pharmaceutical research and development, federated learning faces additional challenges beyond privacy: safeguarding of proprietary information such as molecular structures, compound libraries, experimental protocols, and intellectual property. Consequently, the cost-benefit ratio of federated learning is likely less favorable in pharmaceutical research and development compared with in CDSS. Novel paradigms such as swarm learning, which decentralize both data and model orchestration through blockchain-based peer-to-peer governance, are beginning to overcome some of these challenges68. These decentralized architectures reduce reliance on a central server, mitigate single points of failure, and enhance trust and auditability — features particularly valuable in cross-institutional clinical collaborations68. Furthermore, hybrid models combining transfer learning with privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, or secure multiparty computation are expanding the frontier of what can be learned from distributed data69. These innovations make federated approaches not only more robust and secure but also more scalable and adaptable to the heterogeneity of real-world healthcare systems.

Bias management

AI can reveal latent biases but also perpetuate them if left unchecked. Prevention approaches include automated feature selection, adversarial debiasing, and cross-modal consistency checks. Although randomized clinical trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard, post-hoc analyses are often required to determine subgroups of patients with greater response rates and regulatory purposes. Subgroups are commonly determined based on mono- or bivariate analyses, with specific features sought to show a treatment-modifying effect70. Multivariate analyses are important to determine complex interdependencies of covariates that identify patients most likely to benefit from treatments; however, they can be time-consuming, cause delays in trial readouts, and lack the robustness needed for regulators and payers.

MMAI is best viewed as a complementary analytical layer that can generate hypotheses and support personalized subgroup analyses based on multivariate features, with further potential to identify minimal, independent features that are meaningful to treatment outcomes. A shift toward a priori inclusion of MMAI hypotheses within RCTs could transform future trial design, leading to more personalized trials without the need for post-hoc analyses and their associated perception of bias.

To be adequately assessed and incorporated into clinical practice, a new hierarchy of MMAI evidence modeling is needed (i.e., incorporating real-world data, synthetic controls, and continuous learning systems).

Conclusion

Advances in MMAI offer a unique opportunity to revolutionize oncology by enhancing early detection, refining diagnostics, optimizing trial efficiency, expediting drug development, and personalizing treatment strategies. Initiatives that harness insights from Phase 3 clinical trial data or that are powered by RWE exemplify how MMAI can translate into tangible clinical benefit. While challenges remain, including the necessity for a robust regulatory framework and a collaborative healthcare ecosystem, the potential to predict risks and outcomes from screening to treatment selection through the AI-driven integration of clinical and biological datasets is poised to fundamentally transform oncology and clinical care. This transformation promises considerable benefits for individual patient outcomes, marking a new era in precision medicine.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Lipkova, J. et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell 40, 1095–1110 (2022).

Wu, Y. & Xie, L. AI-driven multi-omics integration for multi-scale predictive modeling of genotype-environment-phenotype relationships. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 27, 265–277 (2025).

Mohsen, F., Ali, H., El Hajj, N. & Shah, Z. Artificial intelligence-based methods for fusion of electronic health records and imaging data. Sci. Rep. 12, 17981 (2022).

Chen, S., Yu, J., Chamouni, S., Wang, Y. & Li, Y. Integrating machine learning and artificial intelligence in life-course epidemiology: pathways to innovative public health solutions. BMC Med. 22, 354 (2024).

Sharma, D. et al. Machine learning approach to classify cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the UK Biobank cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e022576 (2022).

Assaad, S. et al. Artificial intelligence-driven identification of onco-hematology patients who may develop severe COVID-19. Ann. Oncol. 34, S551 (Abstract 846P) (2023).

Qian, X. et al. A multimodal machine learning model for the stratification of breast cancer risk. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 9, 356–370 (2025).

Mikhael, P. G. et al. Sybil: a validated deep learning model to predict future lung cancer risk from a single low-dose chest computed tomography. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 2191–2200 (2023).

Nvidia. Project MONAI. https://docs.nvidia.com/clara/monai/index.html (2024).

Larroza, A. et al. Breast delineation in full-field digital mammography using the segment anything model. Diagnostics 14, 1015 (2024).

Adusumilli, P., Ravikumar, N., Hall, G. & Scarsbrook, A. F. A methodological framework for AI-assisted diagnosis of ovarian masses using CT and MR imaging. J. Pers. Med. 15, 76 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Concordance-based Predictive Uncertainty (CPU)-index: proof-of-concept with application towards improved specificity of lung cancers on low dose screening CT. Artif. Intell. Med. 160, 103055 (2025).

Shiha, M. G. et al. Artificial intelligence–assisted colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. iGIE 2, 333–343 (2023).

Chung, D. C. et al. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 973–983 (2024).

Klein, E. A. et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1167–1177 (2021).

Gupta, V., Kayayan, E. N., Zhang, J., Falakaflaki, P. & Gupta, G. Using AI and clinical knowledge to find missed lung and ovarian cancer patients. ESMO Open 9, 102382 (Abstract 5P) (2024).

McGenity, C. et al. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. NPJ Digit Med. 7, 114 (2024).

Kather, J. N. et al. Pan-cancer image-based detection of clinically actionable genetic alterations. Nat. Cancer 1, 789–799 (2020).

Taylor, C. R., Monga, N., Johnson, C., Hawley, J. R. & Patel, M. Artificial intelligence applications in breast imaging: current status and future directions. Diagnostics 13, 2041 (2023).

Liu, J. A., Yang, I. Y. & Tsai, E. B. Artificial intelligence (AI) for lung nodules, from the AJR Special Series on AI applications. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 219, 703–712 (2022).

Oh, S., Kang, S.-R., Oh, I.-J. & Kim, M.-S. Deep learning model integrating positron emission tomography and clinical data for prognosis prediction in non-small cell lung cancer patients. BMC Bioinform. 24, 39 (2023).

Xiang, J. et al. A vision-language foundation model for precision oncology. Nature 638, 769–778 (2025).

Chen, R. J. et al. Pathomic fusion: an integrated framework for fusing histopathology and genomic features for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 757–770 (2022).

Keyl, J. et al. Decoding pan-cancer treatment outcomes using multimodal real-world data and explainable artificial intelligence. Nat. Cancer 6, 307–322 (2025).

Razavi, P. et al. Prediction of real-world progression free survival (rwPFS) using a multimodal machine learning (ML) model for patients with HR+ HER2- metastatic breast cancer (mBC) undergoing first line (1L) treatment with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) and endocrine therapy (ET). J. Clin. Oncol. 43, e13088 (Abstract) (2025).

Johnson, M. L. et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: the Phase III POSEIDON study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1213–1227 (2023).

Skoulidis, F. et al. TRIDENT: machine learning (ML) multimodal signatures to identify patients that would benefit most from tremelimumab (T) addition to durvalumab (D) + chemotherapy (CT) with data from the POSEIDON trial. Ann. Oncol. 35, S842–S843 (2024).

Esteva, A. et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 25, 24–29 (2019).

Pentimalli, T. M. et al. Combining spatial transcriptomics and ECM imaging in 3D for mapping cellular interactions in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Syst. 16, 101261 (2025).

Costello, J. C. et al. A community effort to assess and improve drug sensitivity prediction algorithms. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1202–1212 (2014).

Sammut, S.-J. et al. Multi-omic machine learning predictor of breast cancer therapy response. Nature 601, 623–629 (2022).

Esteva, A. et al. Prostate cancer therapy personalization via multi-modal deep learning on randomized phase III clinical trials. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 71 (2022).

Alzghaibi, H. Adoption barriers and facilitators of wearable health devices with AI integration: a patient-centred perspective. Front. Med. 12, 1557054 (2025).

Yammouri, G. & Ait Lahcen, A. AI-reinforced wearable sensors and intelligent point-of-care tests. J. Pers. Med. 14, 1088 (2024).

Huang, M.-Y., Weng, C.-S., Kuo, H.-L. & Su, Y.-C. Using a chatbot to reduce emergency department visits and unscheduled hospitalizations among patients with gynecologic malignancies during chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Heliyon 9, e15798 (2023).

Abbas, S. A., Yusifzada, I. & Athar, S. Revolutionizing medicine: chatbots as catalysts for improved diagnosis, treatment, and patient support. Cureus 17, e80935 (2025).

Vinke, P. C. et al. Monitoring multidimensional aspects of quality of life after cancer immunotherapy: protocol for the international multicentre, observational QUALITOP cohort study. BMJ Open 13, e069090 (2023).

Serrano, D. R. et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in drug discovery and drug delivery: revolutionizing personalized medicine. Pharmaceutics 16, 1328 (2024).

Jayatunga, M. K., Ayers, M., Bruens, L., Jayanth, D. & Meier, C. How successful are AI-discovered drugs in clinical trials? A first analysis and emerging lessons. Drug Discov. Today 29, 104009 (2024).

Chow, R. et al. Use of artificial intelligence for cancer clinical trial enrollment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 115, 365–374 (2023).

Rosenthal, J. T., Beecy, A. & Sabuncu, M. R. Rethinking clinical trials for medical AI with dynamic deployments of adaptive systems. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 252 (2025).

Li, G., Chen, Y.-B. & Peachey, J. Construction of a digital twin of chronic graft vs. host disease patients with standard of care. Bone Marrow Transpl. 59, 1280–1285 (2024).

Brasil, S. et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) in rare diseases: is the future brighter?. Genes 10, 978 (2019).

Kolla, L., Gruber, F. K., Khalid, O., Hill, C. & Parikh, R. B. The case for AI-driven cancer clinical trials – the efficacy arm in silico. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1876, 188572 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 194 (2022).

Liu, R. et al. Evaluating eligibility criteria of oncology trials using real-world data and AI. Nature 592, 629–633 (2021).

Hussein, R., Gyrard, A., Abedian, S., Gribbon, P. & Martínez, S. A. Interoperability framework of the European Health Data Space for the secondary use of data: interactive European Interoperability Framework-based standards compliance toolkit for AI-driven projects. J. Med. Internet Res. 27, e69813 (2025).

Potter, D. et al. Development of CancerLinQ, a health information learning platform from multiple electronic health record systems to support improved quality of care. JCO Clin. Cancer Inf. 4, 929–937 (2020).

Elshiekh, C., Rudà, R., Cliff, E. R. S., Gany, F. & Budhu, J. A. Financial challenges of being on long-term, high-cost medications. Neurooncol. Pract. 12, i49–i58 (2025).

Managed Healthcare Executive. Global spending on cancer drugs to increase to $409 billion. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/global-spending-on-cancer-drugs-to-increase-to-409-billion (2024).

Bharadwaj, P. et al. Unlocking the value: quantifying the return on investment of hospital artificial intelligence. J. Am. Coll. Radio. 21, 1677–1685 (2024).

Berdunov, V. et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Oncotype DX Breast Recurrence Score® Test in node-negative early breast cancer. Clinicoecon. Outcomes Res. 14, 619–633 (2022).

Tie, J. et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in Stage II colon cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2261–2272 (2022).

Ligero, M., El Nahhas, O. S. M., Aldea, M. & Kather, J. N. Artificial intelligence-based biomarkers for treatment decisions in oncology. Trends Cancer 11, 232–244 (2025).

El Jiar, M. et al. The state of telepathology in Africa in the age of digital pathology advancements: a bibliometric analysis and literature review. Cureus 16, e63835 (2024).

Holmström, O. et al. Point-of-care digital cytology with artificial intelligence for cervical cancer screening in a resource-limited setting. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e211740 (2021).

Fleming, K. Pathology and cancer in Africa. Ecancermedicalscience 13, 945 (2019).

Chandramohan, A. et al. Teleradiology and technology innovations in radiology: status in India and its role in increasing access to primary health care. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 23, 100195 (2024).

Shreve, J. T., Khanani, S. A. & Haddad, T. C. Artificial intelligence in oncology: current capabilities, future opportunities, and ethical considerations. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 42, 1–10 (2022).

Farasati Far, B. Artificial intelligence ethics in precision oncology: balancing advancements in technology with patient privacy and autonomy. Explor. Target. Antitumor Ther. 4, 685–689 (2023).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Reflection paper on the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the medicinal product lifecycle. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-use-artificial-intelligence-ai-medicinal-product-lifecycle_en.pdf (2024).

U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Good machine learning practice for medical device development: guiding principles. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/good-machine-learning-practice-medical-device-development-guiding-principles (2025).

Loftus, T. J. et al. Federated learning for preserving data privacy in collaborative healthcare research. Digit. Health 8, 20552076221134455 (2022).

Rinaldi, E. et al. International clinical research data ecosystem: from data standardization to federated analysis. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 309, 133–134 (2023).

Casaletto, J., Bernier, A., McDougall, R. & Cline, M. S. Federated analysis for privacy-preserving data sharing: a technical and legal primer. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 24, 347–368 (2023).

Rieke, N. et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 119 (2020).

Kaissis, G. A., Makowski, M. R., Rückert, D. & Braren, R. F. Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 305–311 (2020).

Warnat-Herresthal, S. et al. Swarm Learning for decentralized and confidential clinical machine learning. Nature 594, 265–270 (2021).

Salem, M., Taheri, S. & Yuan, J.-S. Utilizing transfer learning and homomorphic encryption in a privacy preserving and secure biometric recognition system. Computers 8, 3 (2019).

Grouin, J.-M., Coste, M. & Lewis, J. Subgroup analyses in randomized clinical trials: statistical and regulatory issues. J. Biopharm. Stat. 15, 869–882 (2005).

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Katrina Rimmer, PhD, and Jacqueline Harte, BSc, of Helios Medical Communications, part of Helios Global Group, and was funded by AstraZeneca in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.D.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. D.R.: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. B.G.: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. G.R.: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. B.T.L.: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. P.R.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. T.D.M.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. T.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A.R.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. J.S.R.-F.: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. P.M.: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. T.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. T.D.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. H.N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. R.M.: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. P.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.D., G.R., B.T.L., T.D.M., Tr.G., A.R., J.S.R.-F., Th.G., H.N., and P.A. report employment by and stock ownership/shareholder for AstraZeneca. D.R. is an employee of NVIDIA, a Member of the STFC Innovation & Business Board, and a Member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Zimin Institute for AI Solutions in Healthcare; D.R. is a minority shareholder of AstraZeneca and NVIDIA. A.M. reports employment by and stock ownership for AstraZeneca and stock ownership for NVIDIA. T.D. reports employment by AstraZeneca. B.G. reports employment by NVIDIA. P.R. has served as a consultant and/or advisory board member, or received Honoraria from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Lilly/Loxo, Prelude Therapeutics, Epic Sciences, Daiichi-Sankyo, Foundation Medicine, Inivata, Natera, Tempus, SAGA Diagnostics, Guardant, and Myriad; P.R. has received institutional grant/funding support from Grail, Novartis, AstraZeneca, EpicSciences, Invitae/ArcherDx, Biothernostics, Tempus, Neogenomics, Biovica, Guardant, Personalis, and Myriad. P.M. and R.M. report employment by SOPHiA GENETICS.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dellamonica, D., Ruau, D., Griffiths, B. et al. The AI revolution: how multimodal intelligence will reshape the oncology ecosystem. npj Artif. Intell. 1, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44387-025-00044-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44387-025-00044-4