Abstract

An effective parameter identification method is critical in hydraulic transient simulation for pipeline condition assessment. Existing studies neglect the hydraulic spatiotemporal dynamic characteristics and multi-frequency updating characteristics of simulation parameters, resulting in unsatisfactory interpretability and simulation accuracy. In this study, a knowledge-discovery and embedded intelligent framework is proposed to identify optimal friction and capture the multi-frequency variation of friction for accurate hydraulic simulation of liquid pipelines. Particularly, the proposed framework identifies optimal friction by transforming conventional evaluation criteria in optimization theory-based methods based on quantified representations of hydraulic spatiotemporal dynamics. By leveraging underlying physical principles of hydraulic transients, an enhanced neural network is proposed by reforming forward and backward propagation for an efficient surrogate of parameter identification. Subsequently, the proposed framework achieves a multi-frequency parameter refreshment under both pseudo-steady and transient conditions. In this way, a synchronous and flexible online simulation is achieved by integrating knowledge-discovery identification with knowledge-embedded modeling. By comparing to representative squared-error-based method, the efficacy and accuracy of the proposed framework are demonstrated experimentally and numerically on real-world cases. The results suggest a promising application of the proposed framework for industry pipeline simulation and process optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pipeline systems have become the most economical and energy-efficient method for transportation and distribution of liquid media1, for instance in urban water supply systems2,3 and petroleum products pipeline systems4,5. In practice, the frequent switching of operation conditions (pump startup, power outage, and shutdown)6,7 makes the hydraulic transient process often present in pipeline systems. With the inevitable aging of the pipeline system and deferred replacement for the aged pipelines, the extreme pressure levels during the transient process may lead to pipeline failure, and even explosion accidents8.

Generally, developing and installing high-precision sensors is an effective way to monitor the hydraulic states (pressure and flowrate) in the pipeline. Nowadays, sufficient multi-source operation data are stored in the Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) system to conduct visual presentation and real-time analysis of pipeline systems9. Nevertheless, due to the high cost of installation and maintenance, the high-precision sensors are often disturbed sparsely in pipeline systems10, resulting in a large non-detection zone. In practice, high-precision sensors are mainly installed at the products distribution points, pipeline inlets, and outlets11. Therefore, deriving efficient simulation tools to estimate the transient hydraulic states is a crucial prerequisite for risk assessment12,13, planning14 and optimization15,16 of pipeline operation.

Based on mass and momentum conservation principles17, one-dimensional water hammer partial differential equations (PDEs) can be derived to represent the hydraulic transient process. Since there is no analytical solution method currently available18, over the past decades researchers have focused on developing numerical discretization methods to estimate the physical quantities of interest, including Method Of Characteristics (MOC)19, Finite Different Method (FDM)20 and Finite Volume Method (FVM)21. In practice, the wave propagation characteristics imply uncertainty of PDEs coefficients22, such as friction, wave speed, and pipe-wall viscoelasticity. These coefficients are pivotal in affecting the computational precision of transient flow PDEs. Unlike other coefficients that remain relatively constant and can be determined through expert’s experience, the friction coefficient is time-dependent and strongly coupled with hydraulic transients. Therefore, the friction coefficient is employed as a lumped parameter, serving to encapsulate simulation discrepancies induced by slight inaccuracies in multiple parameters. Calibration of this parameter enables the simulation results to more accurately reflect the actual hydraulic behavior23.

As a prevalent paradigm of parameter identification, the optimization theory-based method, which identifies unknown pipeline parameters by matching observed signals with the associated numerical models, was first proposed in 1994 by Liggett and Chen24 for leakage detection and friction identification. Optimization theory-based methods can be primarily categorized into two types, mathematical statistical-based methods23,25 and evolutionary optimization-based methods26,27,28, with the latter currently being the mainstream approach due to superior stability and convergence performance. Nevertheless, the current optimization theory-based methods rely on the minimization of squared errors (SE), which only represent the statistical differences between the estimated and observed values. On the often hand, parameter variations reflecting the underlying patterns of spatiotemporal hydraulic dynamics (nonlinear time-delay characteristics and wave-propagation characteristics) are overlooked by conventional objective function. This reduces the physical interpretability and restricts the accuracy of hydraulic simulation, especially during a fast transient process. Furthermore, the cumbersome iterative process requires numerous evaluations of PDEs, which are associated with huge computational time, leading to the incapability of parameter dynamics synchronous extraction29. Then, high-precision flowrate instruments for parameter identification may be compromised by the prohibitively high maintenance costs and their installation-limited deployment to specific locations. Low-cost instrumentation necessitates more frequent meter proving, exponentially escalating verification workloads and operational expenditures30.

With the development of data storage capacity and computational power31, data-driven methods32, such as Nonlinear AutoRegressive neural network with eXogenous inputs (NARX)28, long short-term memory (LSTM)33, and Kriging method34,35 have been utilized for a fast computational pipeline hydraulic simulation. However, some of them only focus on hydraulic parameter prediction in pipeline inlets and outlets, failing to estimate states in non-detection zones. Most importantly, the absence of hydraulic laws in the training process may cause physically unreasonable results under unseen operating conditions and high dependency on sample diversity36. Due to the frequent and diverse variations of pipeline operating conditions, purely data-driven models generally exhibit limited generalization performance under new conditions, leading to limited practical application. Although the innovative physics-informed neural network (PINN) can achieve interpretable and accurate pipeline hydraulic simulation37, it requires burdensome training times, sometimes extending to several hours, thus restricting application38.

Recently, a pioneering technique called data-driven discovery of PDE, which derives the structure and coefficients of differential equations that govern system dynamics from data, has advanced the modeling, simulation, and understanding of complex dynamical systems39,40. This offers an insightful inspiration of parameter identification in a liquid pipeline, as it also attempts to uncover the coefficient in the PDE that governs hydraulic dynamics. Nevertheless, due to the simplifications inherent in one-dimensional flow assumptions, the complex hydraulic characteristics in special pipeline regions (dead ends and bends), and numerical discretization errors, the dynamic variations of variables in observations may not fully conform to the governing equations. Consequently, uncertain residuals can arise when applying these equations to observational data. In large-scale systems, monitoring data are typically available from only two or three sensor points, which cannot support the scientific discovery that relies on dense spatiotemporal data for differential operations. This highlights the necessity of exploring how scientific discovery can be refined in light of the specificities of industrial systems.

To fill the gap of current studies, this study proposes a knowledge-discovery and embedded intelligent framework for interpretable parameter identification and accurate hydraulic simulation, intending to open up an innovative perspective of effective and practical real-time liquid pipeline simulation. This work first designs a spatiotemporal dynamic discovery (PDEC-FIND) algorithm to achieve an interpretable identification of the friction coefficient. PDEC-FIND transforms the minimization of derivative residuals of observational data into minimizing the derivative residuals between the observational and simulation matrices. Thus, the bottleneck whereby simplified governing equations in industrial systems are not always satisfied when applied to process data can be overcome. Meanwhile, by combining the observational data from two spatial locations with extensive simulated values generated using the candidate friction, it addresses the gap for dense spatiotemporal measurements to compute partial derivatives. The proposed algorithm effectively addresses limitations of existing optimization theory-based approaches: poor interpretability and transient-condition fidelity degradation. Results suggest that PDEC-FIND demonstrates promising accuracy and generalization in friction identification with different pipeline and liquid properties. Subsequently, a knowledge-embedded autoregressive neural network (KE-ANN) is proposed to serve as an efficient flowrate-free surrogate of parameter identification. By designing a dual-layer physics-informed neural network to endow hidden layers with explicit physical interpretability, KE-ANN overcomes the shortcomings of purely data-driven models with insufficient generalization capability and accuracy under unseen operating conditions. To enforce a high compliance of the neural network with hydraulic laws, a physics-guided three-stage training strategy is developed to guide the backward propagation. Eventually, a condition-adaptive simulation framework, which captures synchronous variation of friction across pseudo-steady and transient conditions, is proposed for accurate real-time hydraulic simulation.

In particular, this study offers three methodological contributions:

-

(i)

As far as we know from the literature up to date, the first spatiotemporal dynamic discovery framework is designed for interpretable parameter identification. The proposed algorithm tackles the poor interpretability and transient-condition fidelity degradation of existing approaches, thus achieving accurate hydraulic simulation of liquid pipelines in practice. Most importantly, when dealing with industrial process data, PDEC-FIND mitigates the challenges faced by conventional scientific discovery methods, including the non-negligible residuals in governing equations and the high dependence on densely sampled spatiotemporal observations.

-

(ii)

A knowledge-embedded autoregressive neural network with physics-informed forward and backward propagation is developed to achieve an efficient flowrate-free parameter identification surrogate technique. The proposed neural network can overcome the insufficient generalization capability in unseen conditions of the purely data-driven models. The proposed dual-layer network can endow the hidden layer with explicit physical interpretability. The physics-guided multi-stage training strategy can constrain the model products within the solution space of transient flow laws.

-

(iii)

A condition-adaptive simulation framework, which captures multi-frequency variations of the friction coefficient, is proposed to facilitate synchronous updates with observed hydraulic parameters and accurate hydraulic simulation in practical conditions.

Method

Problem description

The transient flow in a liquid pipeline complies with fundamental laws of mass and momentum conservation. As expressed in the Section A of the Supplementary Information, through equation derivation, the continuity and momentum equations that characterize hydraulic dynamics can be obtained. Then, the MOC can be employed to compute the numerical solutions of the governing equations and obtain a mathematical function that relates flowrate and pressure to time and space41. In this way, by arbitrarily defining any two quantities of flowrate and pressure at the inlet and outlet boundaries at time t + 1, the hydraulic parameters along the pipeline at time t + 1 can be obtained. Considering that the pressure transmitters at pipeline ends acquire better stability in measurement precision than ultrasonic flow meters, the monitored pressures are used as inputs and boundary control conditions to drive the hydraulic simulation42. To begin with, the simulation process can be expressed mathematically in Eq. (1):

where \({X}_{t}=[{H}_{0,t},{H}_{1,t},...,{H}_{M,t},{Q}_{0,t},{Q}_{1,t},...,{Q}_{M,t}]\) represents the system state matrix at t. \({U}_{t+1}=[{H}_{0,t+1},{H}_{M,t+1}]\) denotes the boundary control conditions at t + 1, \(F(x)\) is the state update function. Generally, Δt in engineering practice is often set as 1 s for real-time online simulation, and Δx is determined by wave speed and Δt.

To identify the friction coefficient and obtain the optimal hydraulic states, the present parameter identification methods solve the inverse problem by minimizing the SE between estimated (\({Q}_{i,t}^{est}\)) and observed (\({Q}_{i,t}^{obs}\)) flowrate values (Eq. (2)) over a time interval T:

It is implied that the objective function (Eq. (2)) only reflects the statistical differences between estimated and observed flowrate, neglecting the central role of the friction factor in governing the hydraulic spatiotemporal dynamics. Additionally, the observed flowrates may be hard to acquire because the installation of high-precision instruments with high costs is confined to designated pipeline nodes (product delivery nodes, pipeline ends, etc.). Widespread ultrasonic flowmeters require more frequent meter proving due to the more frequent accurate drift, imposing recurrent calibration burdens and operational expenditures elevation. More importantly, existing parameter identification methods are performed by using the data from a fixed interval, like 20 min, and apply the identified parameter to the subsequent interval28. This will bring deviations for hydraulic simulation, especially in the transient process, where hydraulic dynamics change within s. Consequently, this study aims to target in development of an interpretable evaluation function in Eq. (2) and designing an efficient real-time simulation framework to capture the pipeline hydraulic dynamics.

Data-driven knowledge-discovery and embedded framework

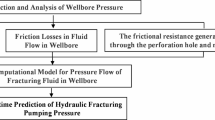

In this section, a data-driven knowledge-discovery and embedded framework (Fig. 1) is proposed, which is composed of three functional modules:

-

(i)

Module 1: A Spatiotemporal Dynamic Discovery algorithm, abbreviated as PDEC-FIND, for interpretable identification of the optimal friction coefficient by modifying the objective function based on spatiotemporal derivative residuals;

-

(ii)

Module 2: A Knowledge-Embedded Autoregressive Neural Network, abbreviated as KE-ANN, for identifying the present friction coefficient under given boundary control conditions and previous hydraulic characteristics;

-

(iii)

Module 3: A Condition-Adaptive Online Simulation Framework for efficient and observed-flowrate-free hydraulic simulation in real-time by executing multi-frequency friction identification.

Module 1: a spatiotemporal dynamic discovery algorithm

In the water hammer PDEs, the friction coefficient is highly relevant to the Reynolds number \(Re=\rho Qd/Av\) (Re is the Reynolds number, v is the viscosity, d is the pipeline inner diameter)43. During the transient condition, the hydraulic parameters undergo rapid changes over s, which in turn lead to variations in the friction coefficient. Consequently, identifying the optimal friction coefficient at present plays a central role in accurate hydraulic simulation.

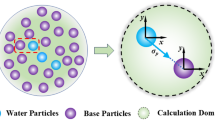

As depicted in Fig. 2, the initial condition of state estimation is regarded as a pseudo-steady condition. Therefore, initial hydraulic states along the pipeline can be obtained by Darcy’s friction law as \(H(x,t)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{L\times m}\) and \(Q(x,t)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{L\times m}\), where L is the pipeline length and m is the total time of pseudo-steady condition. Assuming that the time interval of parameter identification is denoted as T. Given the boundary control conditions in the ith time interval \(H(x,t)\), with \(x\in \{0,L\}\) and \(t\in [(i-1)T+1,iT]\), and the hydraulic states \(H(x,t)\) and \(Q(x,t)\), with \(x\in [0,L]\) at the last time step of (i-1)th time interval, the state matrices can be estimated through hydraulic simulation introduced in Section “Problem description”, as expressed in Eqs. (3) and (4):

Given that widely installed ultrasonic flow meters at pipeline ends hold satisfied measurement precision after meter proving, the observed flowrates are obtained from calibrated ultrasonic flow meters. By replacing the flowrate at the boundaries in the estimated flowrate matrix with the observed values, the reference state matrices can be obtained (Eqs. (5) and (6)):

When the friction coefficient used for hydraulic simulation is in good agreement with the actual spatiotemporal dynamics, the estimated flowrate matrix and the reference flowrate matrix are expected to be as identical as possible. Noteworthy, the proposed algorithm is not limited to constructing the reference matrix solely from inlet and outlet flowrates. Among the four boundary options of inlet and outlet pressure and flowrate, any two can be selected as boundary conditions, while the remaining two can be substituted accordingly. Thus, the same identification capability can be achieved. Therefore, the partial differential terms of each of the estimated (\(H\) and \(Q\)) and reference (\(H\) and \(\tilde{Q}\)) matrices elements in both the time and space domains are discretized by using the finite difference scheme to obtain the residual of water hammer PDEs, as represented from Eqs. (7) to (10):

Here, ∇ is the gradient operator concerning head and flowrate, calculation process of derivatives can be found in Section B of the Supplementary Information. \({\varPhi }^{est}\) and \({\varPhi }^{ref}\) are a closed library consisting of partial derivatives and constant terms for estimated and reference matrices. \({F}_{1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times 4}\) and \({F}_{2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times 3}\) with \(N=L\times T\) being the total number of collocation points, are the residual terms of momentum and continuity equations corresponding to the estimated state matrices. In contrast, \({G}_{1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times 4}\) and \({G}_{2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times 3}\) are the residual terms of PDEs corresponding to the reference state matrices. Only when the friction coefficient matches the actual value, the spatiotemporal derivatives of the estimation matrices and the reference matrices are identical, thereby making residual terms equal. As such, an evaluation function is suggested to be designed to quantify the differences in spatiotemporal derivative residuals. In this way, the novel objective function can be reformulated as Eq. (11):

where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are hyper-parameters that can be adjusted to improve the convergence effect. Solving this optimization process can lead to an optimal friction coefficient \({f}^{\ast }\) and corresponding hydraulic states \({H}^{\ast }(x,t)\) and \({Q}^{\ast }(x,t)\), especially the non-detection zones along the pipeline. In this way, evaluating differences of spatiotemporal derivative residuals based on Eqs. (3)–(11) endows inherent physical interpretability to parameter identification, which is conspicuously absent in existing methods. The conventional scientific discovery approach uses the objective function of minimizing Eqs. (7) and (8) to uncover the coefficient. However, there are still uncertain residuals even if the coefficient of governing equations conforms to the observed hydraulic dynamics. Therefore, relying on the traditional method cannot obtain the accurate friction, even though the residuals of Eqs. (7) and (8) converge to zero. To compute partial derivatives, conventional scientific discovery methods require observations at most spatial locations are available. Nevertheless, due to the unaffordable cost of installing and operating the instrument, only observations at the pipeline inlet and outlet are available. Consequently, during the iteration procedure, PDEC-FIND integrates predefined friction into PDE simulations to estimate pipeline hydraulics. Then, the partial derivatives of the simulated matrix are constrained to approximate those of the reference matrix.

To solve the optimization problem in Eq. (11), the PSO algorithm is applied (other evolutionary algorithms, like GA, can also be used). Noteworthy, if the friction coefficient calibration is performed in the first time interval, the candidate friction coefficients will be initialized randomly. Otherwise, the candidate friction coefficients are created based on the optimal solution in the previous time interval and recognized operation conditions, as expressed in Eq. (12):

where \({f}^{i}\) is the initialized candidate friction coefficient at the ith time interval and \({f}_{opt}^{i-1}\) is the optimal friction coefficient at the (i-1)th time interval. Finally, the PDEC-FIND algorithm is executed periodically to refresh the friction coefficient to ensure the state estimation model matches the pipeline hydraulic dynamics accurately. In summary, the core enhancement of PDEC-FIND lies in advancing the objective function in optimization theory-based methods through quantifying hydraulic spatiotemporal dynamics differences to represent the time-delayed and wave-propagation characteristics. The proposed algorithm effectively integrates data-driven scientific discovery with the transient hydraulic behavior of liquid pipeline systems. Consequently, by replacing the objective function (Eqs. (7)–(11)) in Fig. 2 as SE (Eq. (2)), the conventional evolutionary optimization-based method can be acquired.

Module 2: knowledge-embedded autoregressive neural network

Although Section “Module 1: A Spatiotemporal Dynamic Discovery Algorithm” creates a novel parameter identification algorithm, the precise flowrate cannot always be obtained due to the post-calibration accuracy degradation of ultrasonic flow meters. Additionally, the real-time application potential of PDEC-FIND is restricted by significant computational time (several min). Consequently, this subsection intends to develop an efficient and flowrate-free surrogate to achieve the same purpose as PDEC-FIND.

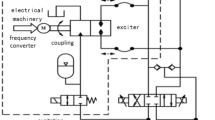

(a) A physics-informed dual-layer neural network

According to the Reynolds Transport Theorem, liquid properties and present flowrate sequences are core factors affecting the present friction coefficient. Given that the present flowrate sequences are unknown, as they are not the boundary control conditions, the previous hydraulic states and present pressure sequences are expected to estimate the present flowrate sequences and achieve a flowrate-free parameter identification. Consequently, a customized dual-layer neural network architecture is proposed, as depicted in Fig. 3. In the first layer, the present pressures are input, and the predicted present flowrates are taken as physics-informed hidden states. Then, in the second layer, liquid properties are input as hidden features to identify the friction coefficient. In this way, the proposed neural network embeds physical knowledge into the hidden layers during forward propagation, thereby improving interpretability compared with conventional data-driven approaches.

Each network layer applies an autoregressive neural network as the baseline to extract time-delay characteristics in the hydraulic parameter. Specifically, the estimated boundary flowrate from (i-1)T to iT and observed boundary pressure from (i-1)T to (i + 1)T are regarded as input features of a hydraulic feature extraction network to estimate the flowrate from iT to (i + 1)T, as expressed in Eq. (13):

where \(ML{N}_{1}\) is the multilayer neural network in the first layer and \({\theta }_{1}\) is the trainable parameters in the neural network of the first layer. \({Q}_{0,t}\) and \({Q}_{L,t}\) represent the flowrates in the pipeline inlet and outlet. \({P}_{0,t}\) and \({P}_{L,t}\) represent the pressures in the pipeline inlet and outlet.

After the first network layer is trained, the estimated present flowrate sequences are feature-wise concatenated with previous flowrate sequences. Subsequently, the friction coefficient at the ith time interval is selected as input of the parameter identification network to capture time-delay characteristics. Then, the density and viscosity of the transported liquid are input to an fully connected (FC) layer to obtain the hidden features and identify the friction coefficient at the (i + 1)th time interval. The forward propagation process of the parameter identification network is expressed from Eqs. (14) to (16):

where X represents the input matrix consisting of liquid properties elements. \({\theta }_{2}\) is the trainable parameters in the neural network of the second layer. \(({W}_{fc},{b}_{fc})\) and \(({W}_{o},{b}_{o})\) are the weights and biases in the FC layer and output layer, respectively.

(b) A physics-guided multi-stage training strategy

It is implied from the transient hydraulic laws that there exists a spatial relation of the flowrate in different locations. Therefore, the predicted flowrate in pipeline inlet \({\hat{Q}}_{0}\) is input into the FC layer and rectified linear unit function (ReLU) to obtain the flowrate correlated feature (\({{Q}^{{\prime} }}_{0}\)). Subsequently, a flowrate relation constraint (Eq. (18)) is developed to evaluate feature distribution similarity and induce distributional congruence between predicted outlet flowrate (\({\hat{Q}}_{L}\)) and correlated feature44:

where \(P(\bullet )\) represents the probability distribution. W and b are the trainable weights and bias, respectively. As such, the coupling loss function of the first training stage can be formulated as in Eq. (20):

where \({Q}_{L}\) and \({Q}_{0}\) are the observed flowrate in pipeline outlet and inlet.

To train the second network layer, the mean squared errors (MSE, Eq. (21)) between identified and observed coefficients are used to adjust the weights and biases:

where \({\hat{f}}_{i+1}\) is the observed friction coefficient. \(\oplus\) represents the feature-wise concatenation. After the second network layer is trained, the dual network layers are co-fine-tuned by mapping previous hydraulic states and present pressure sequences to present friction coefficient. In this way, the physics-guided backward training process can be achieved to enhance the generalization ability. To end with, an observed-flowrate-free neural network with high physical interpretability can be executed to identify the friction coefficient efficiently with a given pressure boundary and an estimated flowrate boundary.

Module 3: condition-adaptive online simulation framework

As a crucial factor that affects the accuracy of hydraulic simulation, the dynamic variations in frequency of the friction coefficient differ under transient and pseudo-steady conditions. In pseudo-steady conditions, only slight variations in the friction coefficient are observed within timeframes ranging from min to hours. On the contrary, the friction coefficient undergoes second-scale dynamic variations during transient operations, especially in rapid transient processes. Optimization-based methods, including PDEC-FIND, which calibrates the friction coefficient with a fixed time interval, are facing a serious limitation of substantial phase delays during transients. Furthermore, it is imperative to address the issue of unreliable and discontinuous acquisition of high-precision instrumental measurements.

As depicted in Fig. 4, by integrating knowledge-discovery friction identification with knowledge-informed modeling, the proposed framework consists of two modules, named offline model training and online hydraulic simulation. Generally, reliable flowrate extraction is achievable for calibrated ultrasonic flow meters, which are widely installed at the pipeline ends. Subsequently, the optimal friction coefficients at different time intervals can be acquired by performing PDEC-FIND based on measurements from pressure transmitters and calibrated ultrasonic flow meters. Then, the hydraulic states at pipeline ends and the friction coefficients are gathered to train KE-ANN. In that way, the trained KE-ANN can be applied to identify friction coefficients without the ultrasonic flow data.

Generally, data acquisition is performed at a 1 s sampling frequency. After obtaining the observed pressure, the operation conditions are recognized by monitoring pressure fluctuation amplitudes against established threshold values. If the pressure fluctuation exceeds the threshold value, the operation condition is determined as the transient condition; otherwise, a pseudo-steady condition is recognized. In this study, a threshold of \(|\varDelta P/P| > 3 \%\) over five seconds is selected. Parameter identification under different operation conditions comprises different time intervals. Specifically, the time interval at the transient condition is set as 30 s, and 5 min under the pseudo-steady condition, respectively. Then, two different friction coefficient databases need to be generated by PDEC-FIND with time intervals being 30 s and 5 min. Subsequently, when the cumulative sampling duration exceeds the preset time interval, the observed pressure and estimated hydraulic states are used as input to KE-ANN to obtain the optimal friction coefficient for the present interval; otherwise, the friction coefficient from the previous interval is adopted for real-time simulation. For pipeline transient, a 30 s-interval friction coefficient calibration is implemented via pre-trained KE-ANN, enabling high-frequency parameter refreshment. For pseudo-steady condition, pre-trained KE-ANN is executed every 5 min. Finally, the optimal present friction coefficient is input to the simulation model for accurate state estimation.

Results

Experimental setting

In this section, several real-world liquid pipelines with different properties are taken as examples to verify the effectiveness and generalization of the proposed framework, as shown in Table 1. All four pipelines possess the same elasticity modulus (2.07 × 1011 Pa). Particularly, as depicted in Fig. 5, pressure data from two high-precision sensors located at pipeline inlets and outlets are used to serve as the input of the state estimation model to estimate the pressure and flowrate at Δx km intervals every second. The observed flowrate from two calibrated ultrasonic flowmeters installed at pipeline inlet and outlet is used to execute PDEC-FIND and flowrate simulation verification. Observed pressure at three valve chambers along the pipeline is applied for pressure simulation verification. The sampling frequency of flowrate and pressure is 1 second.

The suitable network parameters (Table 2) are determined by trial and error. Noteworthy, the hydraulic feature extraction network features an input layer with 180 neurons and an output layer containing 60 neurons when the time interval is 30 s. In contrast, the number of neurons in the input and output layers is 1800 and 600, respectively, when the time interval is 5 min. Additionally, the parameter identification network features an input layer with 123 neurons when the time interval is 30 s and 1203 when the time interval is 5 min. In this study, the proposed neural network model is deployed on the PyTorch framework.

To balance the iteration performance and efficiency of PDEC-FIND, the total number of iterations is set to 80, with 60 candidate coefficients evaluated per individual iteration. As for KE-ANN, the total number of training epochs is selected as 3000, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001. To prevent the neural network from overfitting, an early stopping method with a maximum number of iterations being 300 is adopted.

Noteworthy that the pipeline transient processes examined in this study are induced by flow variations at the pipeline inlet delivery point and the upstream trunk line. Specifically, in Case 1, the transient source is an increase followed by a decrease in the upstream trunk line flowrate. In Case 2, the transient source is a reduction in the inlet delivery point flowrate. In Cases 3 and 4, the transient sources are increases in the inlet delivery point flowrate.

Evaluation and analysis of the proposed PDEC-FIND algorithm

Interpretability analysis of identification results

As shown in Fig. 6, PDEC-FIND is performed with time interval being 30 s to acquire the calibrated friction coefficients of different cases. As in the prevailing research practice24,28,34, the identified friction and objective functions are visualized to illustrate the convergence behavior. It is implied that the friction coefficient is highly relative to the hydraulic parameters, and represents a strong phase synchronization with the flowrate and pressure dynamics. Especially, under conditions of marked instabilities of pressure and flowrate, the friction coefficient manifests abrupt dynamic variations during a short period. This reflects a significant physical interpretability of the proposed PDEC-FIND, which quantifies the differences of transient hydraulic dynamics caused by variation of friction coefficient from the perspective of spatiotemporal derivative residuals.

Results analysis of different time intervals

To carry out a visualization evaluation on how time interval of PDEC-FIND affects the simulation fidelity, the inlet and outlet flowrate estimation results of PDEC-FIND with time interval of 30 s, 1 min, 2 min and 5 min are compared, as shown in Fig. 7. Additionally, to demonstrate the significance of parameter identification, the state estimation model based on MOC without parameter calibration is also used as comparative model. Apparently, rapid pressure fluctuations within a short timescale induce sharp variations in flowrate. Among these, the MOC method yields the highest deviation from the observed curves. Furthermore, it is suggested that the differences in simulation deviations under different time intervals are extremely significant during the transient process, especially the rapid transient dynamics. Among these, the estimated flowrates with time interval of 30 s are closer to the observed flowrates than those of other time intervals. From the results during the transient process from 300 s to 650 s and from 2900 s to 3500 s, it is revealed that the deviations between simulated and observed values increase progressively when the time interval becomes larger. As the identification interval increases, the simulation model becomes less capable of effectively capturing the friction coefficient variations caused by such short-term transient dynamics, thereby leading to consecutive peaks in the simulated results that deviate from the measured values. Estimation deviations of PDEC-FIND with various time intervals during pseudo-steady conditions are not significant, since the actual hydraulic dynamics do not exhibit rapid variations over short periods. Consequently, PDEC-FIND with time interval of 30 s is carried on in the following experimental comparisons.

a Flowrate simulation of MOC and PDEC-FIND with different time intervals for case 1. b Flowrate simulation of MOC and PDEC-FIND with different time intervals for case 2. c Flowrate simulation of MOC and PDEC-FIND with different time intervals for case 3. d Flowrate simulation of MOC and PDEC-FIND with different time intervals for case 4.

To provide a quantified comparison of PDEC-FIND with different intervals, the mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) of transient and pseudo-steady conditions are calculated in Table 3. The MOC method has the highest simulation error during both transient and pseudo-steady operation conditions. It is seen that statistically slight differences in simulation errors with different time intervals during pseudo-steady conditions can be observed. On the contrary, the differences in simulation errors become significant under transient processes. Inlet flowrate simulation with the time interval being 30 s achieves a reduction of MAPE by 61.5% compared to that of the flowrate simulation with the time interval being 5 min in Case 1.

The comparisons of pressure simulation results at three valve chamber locations are depicted in Fig. 8. It is noted that the simulation accuracy increases as the time interval decreases, which also corroborates the conclusion drawn earlier. Among all comparative methods, PDEC-FIND with time intervals being 0.5 min acquires the closest simulated curves to the observed curves than other models.

a Pressure simulation of PDEC-FIND with different time intervals at three locations for case 1. b Pressure simulation of PDEC-FIND with different time intervals at three locations for case 2. c Pressure simulation of PDEC-FIND with different time intervals at three locations for case 3. d Pressure simulation of PDEC-FIND with different time intervals at three locations for case 4.

Effectiveness analysis of the proposed spatiotemporal hydraulic dynamic quantification

Noteworthy, most evolutionary optimization-based parameter identification methods primarily differ in their iterative strategies and evolutionary mechanisms, while the underlying objective functions remain essentially the same. Therefore, this study does not delve into the parameter identification approaches using various existing optimization algorithms, but rather focuses on analyzing the identification results derived from different objective functions. Therefore, the SE-based method, which replaces the objective function of the evolutionary process in PDEC-FIND with SE, is selected as the comparative model to demonstrate the advancement of the proposed spatiotemporal dynamic discovery framework. PSO algorithm is adopted for these two comparative methods with the same identification interval being 0.5 min. As shown in Fig. 9, it is seen that the flowrate estimated by SE-based method is relatively farther from the observed curves than that of PDEC-FIND. By leveraging the representation capacity of time-delayed and wave-propagation characteristics, the flowrates estimated by PDEC-FIND are closer to the observed curves than those of the SE-based method. Overall, the proposed PDEC-FIND algorithm achieves the flowrate estimations closest to the observed curves compared to the other models. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced during transient processes, where PDEC-FIND achieves more accurate hydraulic dynamics reconstruction and a significant improvement in simulation accuracy. For instance, in Case 3 (1000–1300 s), where flowrate changes exceed 7% within a second, the SE-based method shows significant deviation, whereas PDEC-FIND retains high fidelity in capturing hydraulic dynamics. Residual errors and MAPEs of the parameter identification methods are depicted in Fig. 10 and Table 4 reflect a similar conclusion.

a Comparison of flowrate simulation between PDEC-FIND and the SE-based method for case 1. b Comparison of flowrate simulation between PDEC-FIND and the SE-based method for case 2. c Comparison of flowrate simulation between PDEC-FIND and the SE-based method for case 3. d Comparison of flowrate simulation between PDEC-FIND and the SE-based method for case 4.

a Comparison of relative residual errors between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 1. b Comparison of relative residual errors between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 2. c Comparison of relative residual errors between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 3. d Comparison of relative residual errors between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 4.

The wave propagation characteristics cause drastic pressure fluctuations at all pipeline locations during transient operations. As such, pressure simulation results at three valve chamber locations are visually compared during the transient process, as depicted in Fig. 11. Overall, pressure curves simulated by the proposed PDEC-FIND algorithm are the closest to the observed pressure curves, particularly when severe pressure fluctuations occur. For Case 1, rapid pressure variation occurs from 480 s to 600 s, and the pressure curves simulated by SE-based method exhibit the most significant deviation. For case 3, pressure varies from 5.8 MPa to 5 MPa during the period from 1175 s to 1200 s, PDEC-FIND still acquires the closest simulation results to the observed values. A similar conclusion can be drawn in other cases. This implies the fact that by quantifying the spatiotemporal hydraulic dynamics to represent the variations of friction coefficient, the proposed method is expected to have a better capacity for discovering the pressure transient characteristics. A more intuitive visualization of pressure simulation residuals across various time steps is presented in Fig. 12. Obviously, SE-based method demonstrates the highest maximum instantaneous error and the largest cumulative deviations. PDEC-FIND achieves nearly zero pressure simulation residuals at each time step. Table 5 provides quantified comparisons of pressure simulation between SE-based methods and PDEC-FIND. It is seen that the proposed method achieves the lowest simulation errors with average residual being 0.0013 MPa, 0.0011 MPa, 0.0034 MPa, and 0.0042 MPa in the four cases. By leveraging the powerful capability of spatial-temporal derivative for characterizing system dynamics, PDEC-FIND reduces the pressure simulation residuals by 90.4%, 74.4%, 89.9%, and 53.3% compared to SE-based method in the four cases.

a Comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 1. b Comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 2. c Comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 3. d Comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 4.

a Residuals comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 1. b Residuals comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 2. c Residuals comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 3. d Residuals comparison of simulated pressure at three locations between SE-based method and PDEC-FIND for case 4.

Reliability analysis on different boundary conditions combination

Results comparisons from subsections 3.2.1 to 3.2.3 all use the pressure at pipeline ends as control boundaries. Current studies show that the pipeline pressure is more sensitive to the friction dynamic than that of the flowrate. Additionally, the measurement accuracy of certain pipeline instruments is not always stable, and occasional malfunctions may require switching between different simulation boundary conditions. Consequently, this subsection testifies to the simulation accuracy on flowrate-pressure boundary condition. Specifically, the inlet flowrate and outlet pressure are set as boundary conditions to acquire the hydraulic simulation results. Then, the observed inlet pressure and outlet flowrate are used to construct a reference matrix. As depicted in Fig. 13, the simulated pressure and flowrate are in close agreement with the measured values, with only minor discrepancies. This demonstrates that the proposed algorithm can yield reliable friction identification and corresponding hydraulic simulations under different boundary conditions.

a Visualization comparison of hydraulic estimation under flowrate-pressure boundary condition for case 1. b Visualization comparison of hydraulic estimation under flowrate-pressure boundary condition for case 2. c Visualization comparison of hydraulic estimation under flowrate-pressure boundary condition for case 3. d Visualization comparison of hydraulic estimation under flowrate-pressure boundary condition for case 4.

Evaluation and analysis of the proposed online simulation framework

To illustrate the significance of executing condition-adaptive real-time parameter refreshment, the proposed online simulation frameworks with different neural network models are compared with the conventional simulation framework with a fixed time interval (5 min). Noteworthy, the basic benchmark NARX model is used to replace the identification function of KE-ANN to demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating hydraulic transient laws. The friction coefficients and hydraulic parameters from cases 1 and 2 are used to train the neural network, and cases 3 and 4 are used to verify the flowrate estimation accuracy. This makes a nearly 5:5 split ratio of training and testing sets.

As depicted in Fig. 14, the conventional simulation framework obtains the highest deviations from the observed flowrates compared to the other methods. It is seen that due to inherent phase delays in parameter identification, the real-time state estimation based on online parameter identification with a fixed time interval cannot capture high-frequency variations in friction coefficient during the transient process and yields estimations that deviate significantly from observed hydraulic states. By performing condition-adaptive parameter identification, the proposed framework is expected to perform multi-frequency friction coefficient calibration under various operational conditions and estimate the hydraulic state accurately in real-time. From comparisons of residual errors depicted in Fig. 15, the significant simulation deviation induced by parameter identification latency is further corroborated. Furthermore, the proposed framework achieves a more flexible flowrate-free state estimation than the conventional framework, and can be extended to scenarios where precise reference flow measurements are inaccessible. The online framework with the enhanced KE-ANN produces the closest flowrate estimations to the observed flowrates. For instance, during the transient process in Case 4 from 150 s to 700 s, the green flowrate curves estimated by the framework with NARX represent higher deviations when hydraulic parameters reflect larger fluctuations. Particularly, the flowrates estimated by the framework with NARX still show higher disagreement with the observed curves during the pseudo-steady condition, which indicates a worse generalization in identification performance of NARX under unseen training samples. This emphasizes a critical limitation of purely data-driven approaches, that the model generalizability is heavily governed by the spectral richness of the training datasets. Table 6 shows the quantified results of flowrate estimation by different simulation frameworks. Overall, the proposed framework with KE-ANN achieves the smallest estimation errors under both pseudo-steady and transient conditions, with a reduction of MAPE being 68.4% and 71.4% for inlet flowrate estimation with respect to the conventional framework.

Comparisons of pressure curves predicted by various frameworks during fast transient process are provided in Fig. 16. Overall, online framework with KE-ANN obtains the closest pressure curves to the observed curve among other frameworks. For Case 3, from 1170 s to 1275 s, the transition of operating conditions induces severe pressure oscillations throughout the pipeline, with peak-to-peak amplitudes attaining nearly 1 MPa during the 10 s transient period. During this period, the hysteretic behavior of the identified friction coefficient in conventional framework leads to the most significant discrepancy concerning the observed curves, while the online framework with NARX exhibits secondary-level deviations. By leveraging high-frequency parameter update and an explainable friction identification neural architecture, the framework with KE-ANN produces near-perfect fits to observed curves. The same conclusions can be drawn in other cases. The residual errors visualization in Fig. 17 shows that the traditional framework simulations display both the maximum instantaneous error amplitudes and the highest integrated error over the entire domain. The framework with KE-ANN achieves minimal residual errors across all experimental locations in various case-study pipelines. Table 7 shows the average absolute residuals of pressure simulation between different online frameworks. It is seen that the proposed online framework with KE-ANN achieves the most accurate pressure simulation with respect to the other frameworks, with a residuals reduction of 91.0% and 87.7% compared to the conventional framework, and 78.0% and 80.7% compared to the framework with NARX.

Discussion

In this study, we present a prospective paradigm of discovering and embedding implicit spatiotemporal hydraulic dynamics to facilitate interpretable parameter identification and precise online pipeline hydraulic simulation, providing support for effective safety management and operation optimization of liquid pipelines.

By leveraging the powerful capacity of characterizing the hydraulic dynamics differences, our approach develops the partial derivative residuals along spatial and temporal domains of system state matrices. Then, a spatiotemporal dynamic discovery algorithm is proposed to transform the conventional objective function based on partial derivative residuals. In this way, the optimal friction coefficient is discovered to estimate hydraulic states accurately. The proposed algorithm effectively mitigates the challenges faced by conventional scientific discovery methods when applied to industrial process data, including the non-negligible residuals in governing equations and the high dependence on densely sampled spatiotemporal observations. It also tackles the limitations faced by squared-error-based methods that struggle with performance degradation, especially under transient conditions with turbulent fluctuation.

Results on real-world cases indicate that the pipeline transient process harbors prominent variations of spatiotemporal hydraulic dynamics essentially, and PDEC-FIND achieves the most accurate hydraulic simulation. Unfortunately, existing SE-based identification method can only extract the time-series statistical relations in hydraulic states at only pipeline ends, but neglect the spatial-temporal coupling dynamics in system state matrices. The proposed algorithm unlocks a series of opportunities in interpretable thermo-hydraulic dynamic discovery in liquid pipelines stemming from its fundamental capability to handle: (i) similar PDE formulations governing transport phenomena, and (ii) comparable spatiotemporal dynamic behaviors. Benchmarked against the conventional SE-based parameter identification method, the proposed algorithm demonstrates an average of 64.7% (inlet flowrate) and 58.65% (outlet flowrate) MAPE reduction for transient flowrate simulation. For pressure simulation, the proposed algorithm achieves a reduction of 90.4%, 74.4%, 89.9%, and 53.3%.

By designing a physics-informed dual-layer network architecture and a physics-guided multi-stage training strategy, the physical knowledge is embedded into the forward and backward propagation to improve generalization capability and enforce physically reasonable results. Then, a knowledge-embedded neural network is developed to serve as an efficient observed-flowrate-free surrogate of parameter identification. Compared to the conventional end-to-end NARX model with a purely data-driven training process, the enhanced neural network effectively addresses the insufficient generalization capability and accuracy under unseen operating conditions. Subsequently, a condition-adaptive online simulation framework is proposed by leveraging the strengths of the neural network for multi-frequency parameter refreshment and observed-flowrate-free parameter identification. Results of online simulation indicate that by dynamically adjusting identification strategy and time intervals, our approach resolves the persistent issue of phase delays in identified parameters that plagues conventional methods. Furthermore, the integration of hydraulic laws in the neural network enhances the forward and backward propagation, thus providing better generalization and effectiveness in unseen conditions. Benchmarked against the conventional framework, the proposed framework demonstrates 68.35% (inlet flowrate) and 52.15% (outlet flowrate) MAPE reduction in Case 3, further improving to 71.37% and 82.08% in Case 4 during transient conditions. For pressure simulation, the proposed online framework reduces residuals of 91.0% (Case 3) and 87.7% (Case 4) compared to the conventional framework.

Our approach represents a transformative perspective for industry process simulation by establishing a self-improving loop—discovering hidden physics information and feeding it back to refine simulations. However, there still exist some potential limitations. For example, the water hammer PDEs are simplified from a three-dimensional flow model into a one-dimensional model due to the high computational cost, which brings unavoidable computational errors in simulation. Additionally, the simplified governing equation of hydraulic transients cannot reflect the complex dynamic variations of friction resulting from high-frequency pressure waves. The computational accuracy of temporal and spatial derivatives is sensitive to measurement noise, even the white noise in observation data. Consequently, our future work will focus on seeking an efficient mathematical resolution method for multi-dimensional hydrodynamic interaction tensors and a frequency-dependent model to characterize the multi-parameter variations associated with different frequency components of hydraulic dynamics. Moreover, developing a robust numerical discretization method for calculation of spatiotemporal derivatives should also be the focus of future development, for example, in combination with automatic differentiation in deep learning.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Du, J. et al. Deeppipe: a physics-enhanced adaptive multi-modal fused neural network for predicting contamination length interval in multi-product pipeline. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 158, 111564 (2025).

Duan, H.-F. et al. State-of-the-art review on the transient flow modeling and utilization for urban water supply system (UWSS) management. J. Water Supply.: Res. Technol. Aqua 69, 858–893, https://doi.org/10.2166/aqua.2020.048 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Duan, H.-F., Keramat, A. & Che, T.-C. On the leak-induced transient wave reflection and dominance analysis in water pipelines. MSSP 167, 108512 (2022).

Liao, Q. et al. Innovations of carbon-neutral petroleum pipeline: a review. Energy Rep. 8, 13114–13128 (2022).

Yao, Z., Zhang, Y., Zheng, Y., Xing, C. & Hu, Y. Enhance flows of waxy crude oil in offshore petroleum pipeline: a review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 208, 109530 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Deeppipe: a semi-supervised learning for operating condition recognition of multi-product pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 150, 510–521 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Deeppipe: a hybrid model for multi-product pipeline condition recognition based on process and data coupling. Comput. Chem. Eng. 160, 107733 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Keramat, A. & Duan, H.-F. Formulation and analysis of transient flows in fluid pipelines with distributed leakage. MSSP 212, 111294 (2024).

Du, J. et al. Deeppipe: Theory-guided prediction method based automatic machine learning for maximum pitting corrosion depth of oil and gas pipeline. ChEnS 278, 118927 (2023).

Roshani, G. H., Feghhi, S. A. H. & Setayeshi, S. Dual-modality and dual-energy gamma ray densitometry of petroleum products using an artificial neural network. Radiat. Meas. 82, 154–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2015.07.006 (2015).

Zheng, J. et al. Deeppipe: theory-guided LSTM method for monitoring pressure after multi-product pipeline shutdown. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 155, 518–531, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2021.09.046 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. Deeppipe: theory-guided neural network method for predicting burst pressure of corroded pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 162, 595–609, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.04.036 (2022).

Sun, M. -m et al. Limit state equation and failure pressure prediction model of pipeline with complex loading. Nat. Commun. 15, 4473. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48688-1 (2024).

Sidki, M., Tchernev, N., Féniès, P., Ren, L. & Elfirdoussi, S. Heuristic based decision approach for an integrated slurry pipeline network scheduling in the phosphate industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 269, 126495 (2025).

Liao, Q., Zhang, H., Xu, N., Liang, Y. & Wang, J. A MILP model based on flowrate database for detailed scheduling of a multi-product pipeline with multiple pump stations. Comput. Chem. Eng. 117, 63–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2018.05.002 (2018).

Tu, R. et al. Machine learning application in batch scheduling for multi-product pipelines: a review. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 4, 100180 (2024).

Waqar, M. et al. Pipeline leak detection using hydraulic transients and domain-guided machine learning. MSSP 224, 111967 (2025).

Delgado-Aguiñaga, J. A., Puig, V. & Becerra-López, F. I. Leak diagnosis in pipelines based on a Kalman filter for linear parameter varying systems. Control Eng. Pract. 115, 104888 (2021).

Ghidaoui, M. S., Zhao, M., McInnis, D. A. & Axworthy, D. H. A review of water hammer theory and practice. ApMRv 58, 49–76 (2005).

Chaudhry, M. H. in Applied Hydraulic Transients (ed M. Hanif Chaudhry) 65-113 (Springer New York, 2014).

Hwang, Y.-H. & Chung, N.-M. A fast Godunov method for the water-hammer problem. IJNMF 40, 799–819 (2002).

Ye, J., Do, N. C., Zeng, W. & Lambert, M. Physics-informed neural networks for hydraulic transient analysis in pipeline systems. Water Res 221, 118828 (2022).

Wang, X. & Ghidaoui, M. S. Identification of multiple leaks in pipeline: Linearized model, maximum likelihood, and super-resolution localization. MSSP 107, 529–548, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.01.042 (2018).

Liggett James, A. & Chen, L. C. Inverse transient analysis in pipe networks. J. Hydraul. Eng. 120, 934–955 (1994).

Kang, D. & Lansey, K. Demand and roughness estimation in water distribution systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 137, 20–30, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000086 (2011).

Malekpour, A. & She, Y. Real-time leak detection in oil pipelines using an Inverse transient analysis model. J. Loss Prev. Process Indust. 70, 104411 (2021).

Zhang, C., Gong, J., Zecchin, A., Lambert, M. & Simpson, A. Faster inverse transient analysis with a head-based method of characteristics and a flexible computational grid for pipeline condition assessment. J. Hydraul. Eng. 144, 04018007 (2018).

He, L., Wen, K., Wu, C., Gong, J. & Ping, X. Hybrid method based on particle filter and NARX for real-time flow rate estimation in multi-product pipelines. J. Process Control 88, 19–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprocont.2020.02.004 (2020).

Zhang, C. & Shafieezadeh, A. Nested physics-informed neural network for analysis of transient flows in natural gas pipelines. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 122, 106073 (2023).

Zhang, X.-Z. Calculation and measurement of the magnetic field in a large diameter electromagnetic flow meter* *Based on “Calculation and measurement of the magnetic field in a large diameter electromagnetic flow meter” by Xiao-Zhang Zhang, published in the proceedings of the ISA Emerging Technology Conference, September 10-13, 2001, Houston, TX. ISAT 42, 167-170 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-0578(07)60123-2 (2003).

Zheng, J. et al. A hybrid framework for forecasting power generation of multiple renewable energy sources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 172, 113046 (2023).

Du, J. et al. A hybrid deep learning framework for predicting daily natural gas consumption. Energy 257, 124689 (2022).

Xu, Z., Ying, Z., Li, Y., He, B. & Chen, Y. Pressure prediction and abnormal working conditions detection of water supply network based on LSTM. Water Supply 20, 963–974, https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2020.013 (2020).

Yin, X. et al. A high-accuracy online transient simulation framework of natural gas pipeline network by integrating physics-based and data-driven methods. ApEn 333, 120615 (2023).

Wang, X. Fast computation of inverse transient analysis for pipeline condition assessment via surrogate modeling with sparse sampling strategy. MSSP 162, 107995 (2022).

Du, J. et al. Deeppipe: a two-stage physics-informed neural network for predicting mixed oil concentration distribution. Energy 276, 127452 (2023).

Du, J. et al. DeepPipe: a multi-stage knowledge-enhanced physics-informed neural network for hydraulic transient simulation of multi-product pipeline. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 42, 100726 (2024).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. JCoPh 378, 686–707 (2019).

Schmidt, M. & Lipson, H. Distilling free-form natural laws from experimental data. Sci 324, 81–85, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1165893 (2009).

Bongard, J. & Lipson, H. Automated reverse engineering of nonlinear dynamical systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9943–9948, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0609476104 (2007).

Goslinga, J., Massinon, R. V. J. & Blackadar, D. C. in PSIG Annual Meeting PSIG-8607 (1986).

Temperley, N. C., Behnia, M. & Collings, A. F. Flow patterns in an ultrasonic liquid flow meter. Flow. Meas. Instrum. 11, 11–18 (2000).

Chaudhry, M. H. In Applied Hydraulic Transients (ed M. Hanif Chaudhry) 35-64 (Springer New York, 2014).

Du, J. et al. A theory-guided deep-learning method for predicting power generation of multi-region photovoltaic plants. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 118, 105647 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52202405), the ARC Linkage Project LP230100083, the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFE0100800), the China Scholarship Council program (Project ID: 202406440090) and the Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (2462023BJRC026). The authors are grateful to all study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. provided the concepts and methodology for the research. J.D. wrote and reviewed the main manuscript text. J.D. and H.C.L. wrote the code framework for the model. J.D. prepared all figures and tables. J.Q.Z., Q.L., J.S., and E.Z. proofread and reviewed the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, J., Li, H., Zheng, J. et al. Towards parameter identification in pipeline hydraulics: integrating data-driven discovery and knowledge embedding. npj Artif. Intell. 2, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44387-025-00054-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44387-025-00054-2