Abstract

Wildfire events have increased in severity in recent years, contributing to environmental changes and posing risks to Air Quality (AQ) and public health. Evaluating their chemical composition is critical for mitigating the impacts of biomass burning. In this study, thirteen fire events, sampled during the 2019 FIREX-AQ field campaign in the US, were evaluated. The aircraft in-situ data with fuel type assessments revealed the dominance of flaming combustion, with modified combustion efficiency values exceeding 0.9. The abundance of light-absorbing carbonaceous species (LACS) was investigated alongside correlations between gas and particle-phase emissions, identifying potential indicators of the dominant in-plume organic aerosol (OA) chemical regimes. The majority of the examined plumes were classified as aged. Their composition reflected a balance between OA oxidation-driven condensation and dilution-driven evaporation, with dilution-driven evaporation emerging as the prevailing chemical process. The evaluation of combustion phase and dominant chemical regimes of OA via main fire tracers and LACS underscore the importance of these species to plume characteristics and evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Warmer and drier climatic conditions have led to increases in severe and extreme fire events over the past years, also affecting public health1,2. During such events, biomass burning emissions emit primary gaseous and particulate species, trace metals and vapors3. Key gaseous species include carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3) and methane (CH4), which are primarily (CO2, CO, and CH4) emitted during biomass burning and secondary formed inside the generated fire plume (CO and O3)4,5,6,7,8. In addition, organic species, water-soluble and non-water-soluble, comprise a significant portion of primarily emitted compounds, including light-absorbing carbonaceous species (LACS)9. The chemical and physical evolution of fire plumes is determined by the chemical interactions, fuel type and topography3,5,10.

LACS species, specifically black (BC) and brown (BrC) carbon, have a pivotal role in the chemistry and radiative balance of fire plumes. During daytime, their absorptive capacity influences the Earth’s energy balance leading to a warming effect11,12,13,14,15. Specifically, BC and BrC strongly absorb in the ultraviolet and visible spectra; however, exposure to sunlight can lead to BrC photobleaching, reducing its light-absorbing capacity11,13,14. During nighttime, the in-plume oxidative processes are shifted due to the lack of sunlight. Formation of secondary OAs, including LACS, via oxidants present during nighttime (e.g, O3 and nitrate radicals (NO3)) can increase the light-absorption capacity of aerosols16,17,18.

The formation of organic species, including LACS, is influenced by the fuel type and moisture, which in turn governs the combustion phase of the fire plume: flaming and smoldering19. Efficient burning typically leads to more complete combustion of organic, resulting in less complex chemical constituents (e.g. more CO2). In contrast, inefficient burning results in incomplete combustion and the formation of persistent species (e.g., BC), secondary OAs, and increases harmful pollutants19. High volatile organic loading, leading to secondary OA formation, is typically emitted through biomass burning of woody lands, due to high lignin and cellulose quantities19. Peat- and agricultural-originated smoke plumes have high particulate carbon content and trace metal loading compared to other fuel types, while grass-originated fires typically burn more efficiently and emit fewer secondary OA precursors than wood-fuel fires20,21,22,23. In addition, moist, dense peat fires are dominated by smoldering combustion, whereas the majority of non-peat wildfires have an associated combustion phase (flaming:smoldering)5,19. Defining the dominant flaming and smoldering combustion phases of a fire is achieved using gas-species correlations and ratios, and by calculating the modified combustion efficiency (MCE \(\ge\) 0.9 means flaming combustion)19,24,25. Flaming combustion is associated with high CO2, water vapor and organic species loading, and can be the dominant combustion phase of freshly generated plumes5,26,27.

Inside fire plumes, the OA evolution is determined by two competing regimes, which determine their chemical evolution, physical characteristics and downwind transport: oxidation-driven condensation and dilution-driven evaporation28,29,30,31. In fresh plumes, oxidation and condensation are key processes, while as the plume ages, dilution and evaporation become more prominent28,30,31. Enriched plumes with high OA mass concentrations present rapid condensation compared to dilution, regardless of their age32. The shift between the two regimes governs the formation of LACS. Specifically, the dispersion of the plume reduces the semi-volatile organic compounds concentrations, leading to their evaporation from the particle to gas phases and thus, reducing the total mass of LACS33,34. The regime shift towards oxidation-driven condensation can lead to a net increase of BrC, due to the availability of semi-volatile organic species for oxidation, leading to BrC formation33.

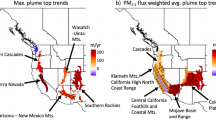

In this work, we utilize the collected gaseous and particulate fire plume emissions collected during the Boise Deployment of the 2019 Fire Influence on Regional to Global Environments and Air Quality (FIREX-AQ) field campaign (Figs. S1–S4), focusing on the concentrations of CO2, CO, O3, water-soluble organic carbon (WSOC) and LACS. The vegetation (fuel) type is assessed alongside the chemical emissions to determine the dominant combustion phase of thirteen fire events. Two methods, using the gaseous and particulate emissions, and LACS separately, are used to examine indications of the in-plume OA dominant chemical regime. This work provides a detailed analysis of key fire tracers that influence plumes’ fate and highlights the importance of considering the fuel type and LACS with respect to dominant in-plume processes.

Results

Flight trajectories

Seven flights from the Boise Deployment (BD) were investigated, showing variation in flight trajectories, plume heights and ecosystems. The flights analyzed were deployed from the western point of the campaign from Boise, Idaho (ID). Figures S1–S4 present the flight trajectories and heights, categorized by fuel type. In the majority of the flights, the plume sampling heights (highest points reached) were between 1 and 13 km, following a continuous sigmoid pattern. Flight time in the smoke zone corresponds to in-plume sampling (average height of 4 km), while lower and higher heights provide information on near-surface (below the plume) and background (above the plume) air. Fresh plumes are sampled downwind of the fire source, where the primary chemical composition is present. The measured time since emissions provided an aged plume assessment35,36,37,38. Plumes with ages less than 2 to 3 h are typically considered fresh, while plumes greater than 3–6 h old are considered moderately aged and plumes greater than 6 h old classified as aged, with significant chemical evolution3,19,39.

Figure 1 shows the estimated age and height (highest points) of the examined plumes. During the BD, two flights capture 0.1–1.0 hr and 0.1–2.0 hr old (fresh) plumes corresponding to the Sheep (Fire number 1: F#1) and Ridgetop (F#5) fires (Fig. 1, Table 1) (see Methods). Five plumes are categorized as moderately aged include: North Hills (F#3), Lick Creek (F#5), Lick Creek (F#6), Williams Flats (F#7) and Horsefly (F#7), with an average plume age of 3 h. The fresh plumes had corresponding heights ranging between 1 and 11 km, while the moderately aged plumes ranged between 4 and 13 km. Aged plumes, with ages up to 55 h, were observed from Shady (F#2), Tucker (F#3), Barren Hill (F#4), Left Hand (F#4) and William Flats (F#6) with plume heights between 5 and 11 km. The Tucker fire (F#4) evolved during sampling from a moderately aged to an aged plume.

Panel a presents these parameters for the Sheep fire, panel b for the Shade fire, panel c for the North Hills fire, panel d for the Tucker fire, panel e for the Barren Hill fire, panel f for the Left Hand fire, panel g for the Ridgetop fire, panel h for the Lick Creek fire, panel i for the second sampling of the Lick Creek fire, panel j for the Williams Flats fire, panel k for the second sampling of the Williams Flats fire, and panel l for the Horsefly fire. Note, the y axes are not the same. The age of each plume is presented, as described in Table S1. The age and height of the plume were linked to the dominant combustion phase of each examined fire.

Light-absorbing carbonaceous species

Figure 2 shows the BC concentrations of each examined fire plume. Fire plumes with low BC loading (<1.4 μg m−3) include Sheep (F#1), North Hills (F#2), Barren Hill (F#4), Left Hand (F#4) and Lick Creek (F#5) (Fig. 2), while for Lick Creek (F#6) there was no measurement. Plumes with a moderate BC range (2.0–20 μg m−3) include Shady (F#2), Tucker (F#3), Ridgetop (F#5), Williams Flats (F#7) and Horsefly (F#7). The fire plume of Williams Flats of F#6 (originally sampled on August 3rd and subsequently sampled on August 6th during F#7) smoke plume contained BC levels on the order of 10 μg m−3, with the highest concentrations of 34 μg m−3. Low concentrations can be attributed to mixing during aging of the plume, indicating sampling at the edges of the plume (see Section S4).

Panel a shows the BC loading for F#1 fire plume, panel b for F#2 fire plume, panel c for the F#3 and F#4 fire plumes, panel d for the F#5, F#6 and F#7 fire plumes, panel e for the F#8 and F#9 fire plumes, panel f for the F#10 and F#11 fire plumes, and panel g for the F#12 and F#13 fire plumes. The shadings correspond to the duration of sampling during the flights. The F# abbreviations refer to the number of flight corresponding to the sampled fire and the shorthand corresponds to low (L), moderate (M) and high (H) BC loading. The different colors represent the corresponding fire plume and are used for direct comparison with the species examined herein. All examined times are in UTC time zone. Note, the y-axes are not the same.

Figure 3 presents the water-soluble brown carbon absorption (WSBrC) at the absorption wavelength of 365 nm. Apart from three fires (North Hills (F#3), Ridgetop (F#5) and Williams Flats (F#7)), the WSBrC increases as the BC increases, indicating primary emissions. North Hills (F#3) and Williams Flats (F#7) had WSBrC absorption coefficient of up to 10 Mm−1, while the corresponding BC concentrations were low to moderate (\(\sim\)1–4 μg m−3). In addition, Barren Hills (F#4) plume contained WSBrC with absorption coefficient of up to 2.8 Mm−1 and average BC of 0.2 μg m−3, while the third-in-order sampled fire plume during the same flight (Left Hand) contained WSBrC with absorption coefficient of up to 1.8 Mm−1 and average BC of 0.4 μg m−3. However, both plumes had overall low LACS content. Notably, although the sampled plumes during flights #2 (Shady) and #5 (Ridgetop) reached high BC loading (up to 20 μg m−3), their WSBrC absorption coefficient was less than 1.5 Mm−1. This can possibly be attributed to mixing of BC and BrC with background air that leads to coating of BC by BrC, offering a protective shield (shielding effect) and thus reducing the BrC absorption, particularly at shorter wavelengths40. Specifically, upon mixing of BC with BrC, the latter can form a coating layer at the BC core, blocking incoming light. This leads to a reduction of the BrC absorption, particularly at shorter wavelengths, due to alternation of the optical path and absorption efficiency through coating40. The observed low levels of LACS were due to mixing with background air that corresponded to sampling at the edges of the plume.

Panel a shows the WSBrC absorption coefficient for F#1 fire plume, panel b for F#2 fire plume, panel c for the F#3 and F#4 fire plumes, panel d for the F#5, F#6 and F#7 fire plumes, panel e for the F#8 and F#9 fire plumes, panel f for the F#10 and F#11 fire plumes, and panel g for the F#12 and F#13 fire plumes. The shadings correspond to the duration of sampling during the flights. The different colors represent the corresponding fire plume and are used for direct comparison with the species examined herein. All examined times are in UTC time zone. Note, the y-axes are not the same.

Water-soluble organic carbon

Water-soluble organic carbon (WSOC) contains WSBrC and is typically a weak light-absorbent, in contrast to WSBrC. Significantly high concentrations were observed during the sampling of Shady (F#2), Williams Flats (F#6) and Horsefly (F#7), with maximum and average levels at 240 and 32.4 μg m−3, 510 and 102.3 μg m−3, and 290 and 68.2 μg m−3 (Fig. 4). These fire plumes were also characterized by high BC loading (non-soluble fraction). Notably, Williams Flats (F#6) and Horsefly (F#7) plumes had WSBrC absorptivity of up to 10 Mm−1, while in the Shady plume the absorptivity reached up to 1.3 Mm−1. Low WSOC content was measured during sampling of the Sheep (F#1) (< 3.0 μg m−3), North Hills (F#3) (<6.0 μg m−3), Tucker (F#4) (<1.0 μg m−3) and Left Hand (F#4) (<5.0 μg m−3) plumes. Such low WSOC abundances are attributed to mixing with the background air, as observed for the case of LACS, indicating sampling further away from the center of the plume (see Section S4).

Panel a shows the WSOC concentrations for F#1 fire plume, panel b for F#2 fire plume, panel c for the F#3 and F#4 fire plumes, panel d for the F#5, F#6 and F#7 fire plumes, panel e for the F#8 and F#9 fire plumes, panel f for the F#10 and F#11 fire plumes, and panel g for the F#12 and F#13 fire plumes. The shadings correspond to the duration of sampling during the flights. The different colors represent the corresponding fire plume and are used for direct comparison with the species examined herein. All examined times are in UTC time zone. Note, the y axes are not the same.

Gas-phase species

Carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations were measured continuously during each flight (Fig. S5). Minor variations were observed in most of the examined plumes in the order of 5–10 ppm, with typical concentrations ranging between 405 and 420 ppm. During the sampling of the fires, Shady (F#2), Tucker (F#3), Williams Flats (F#6) and Horsefly (F#7) the CO2 concentrations reached up to 480 ppm. The fluctuations in CO2 levels were not significant, as typically CO2 can range from 102 to 103 ppm in fresh plumes and is stabilized as the plume ages5,19,41. At low-light conditions, which typically corresponds to high-smoke conditions and/or nighttime sampling, vertical mixing is reduced due to stabilization of the atmospheric boundary layer42, leading to the observed small variations in CO2 concentrations. Under high-light conditions, typically during daytime, the relative in-plume CO2 stability is attributed to minor chemical transformation and diurnal boundary layer dynamics. Specifically, the convective boundary layer deepens and entrains cleaner air from the above layers. This results in dilution of elevated in-plume CO2, while marginally changing its concentration5,19,41,43.

Similar to CO2, methane (CH4) remains fairly stable in fire plumes due to its limited chemical transformation, attributed to high concentrations of competing in-plume species5. Specifically, reactive species, such as volatile organic compounds, compete with CH4 for reactions with radicals and oxidants and, when present in high concentrations inside the fire plume, lead to limited CH4 chemical transformation and thus CH4 chemical in-plume stability5. Measured CH4 levels ranged from 1.8 to 2.6 ppmv (Fig. S6), with concentrations above 2.0 ppmv typically coinciding with fire plumes that also exhibited elevated CO2.

In contrast, carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations varied significantly during in-plume sampling (Fig. S7). The lower concentrations (50–230 ppbv) recorded during sampling correspond to F#4, including the fire plumes generated by Barren Hill, Tucker and Left Hand, with Tucker plume maintaining CO levels at an average of 80 ppbv. The Tucker fire plume of F#4 was categorized as aged (Fig. 1, Table 1), due to the plume age range of 15–55 hr. In addition, this fire plume was sampled during F#4 on a second consecutive day, following the initial sampling in F#3 on the 29th of July, when CO concentrations spanned from 50 to 2700 ppbv, revealing a freshly (up to 2700 ppbv) evolved to moderately aged plume (average of 85 ppbv) (re-ignition) (Figs. 1 and S7, Table 1). The re-ignition of the sampled fire plume during F#4 was characterized by relatively stable CO concentrations (Fig. S7), indicating ongoing but less intense combustion activity. The smoother temporal CO profile of F#4 plume, compared to F#3, revealed a stable emission profile. F#6 Lick Creek fire plume also contained low CO values (<300 ppbv), which was attributed to the elevated sampling height (7–8 km), compared to the rest of the sampling plumes.

Due to its direct connection with CO, ozone (O3) concentrations were increasing with decreasing CO concentrations (Fig. S7 and Figure S8), via radical oxidation. These increases, on some occasions, were marginal revealing a constant profile of O3. Relatively stable O3 levels were observed for aged plumes, due to nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions decrease, which subsequently reduced the potential for O3 loss via reactions with NO44. Average O3 levels inside the plumes ranged between 30 and 80 ppbv, while increased levels (up to 180 ppbv) were measured in-between plume sampling. During these time blocks the aircraft was cruising at >8 km heights, where O3 is typically boosted due to production and transport mechanisms16,43.

Combustion phase characterization

Land-cover-driven fuel characteristics of the examined ecosystems played an important role in identifying the dominant combustion phase of the investigated fire events. To further elucidate the chemical regimes of OA, we employed two complementary methods targeting a) both main gaseous compounds and dissolved organic species, and b) LACS. This integrated approach, detailed below, provided essential insights into prevailing combustion phase and OA chemical regimes across the examined fire events, laying the foundation for understanding their atmospheric impacts.

Six major fuel types were identified in the examined fire plumes (Sections S3 and S5): a) shrubland, b) savanna, c) understory, c) grassland, d) forest, and e) mixed-fuel. The identification of the dominant combustion phase relied primarily on MCE, and secondary on correlations of examined gaseous and particulate species (Fig. 5 and S11–S15). High in-plume CO concentrations are typically indicative of smoldering combustion, whereas elevated BC concentrations are associated with flaming combustion. A high CO2:CO ratio reflects rapid dilution of CO relative to CO2, and/or oxidation of CO to CO2 during plume aging. Therefore, when the MCE is <0.9, a high CO2:CO may also reflect secondary chemical processing in addition to the combustion characteristics at the emission source. In contrast, when CO2:CO ratio is low and MCE \(\ge\) 0.9, the plume could have undergone dilution, resulting in CO2 approaching background levels rapidly, while CO remains elevated longer, skewing the CO2:CO ratio to lower values and reflecting a smoldering dominant plume. Since MCE is calculated using excess mixing ratios (in-plume levels minus the background), it represents the relative amount of oxidized carbon (CO2) vs partially oxidized carbon (CO). Thus, MCE is less sensitive to dilution than the CO2:CO ratio and constitutes a more reliable metric when other parameters yield conflicting conclusions about combustion phase19,42,44.

Panel a presents a Shrubland fuel type case and panel b an Understory case. Parameters of all fuel types are presented in Figs. S11–S15. Panels (i) show the MCE, (ii) the CO-O3 correlation, (iii) the CH4:CO2 ratio and (iv) the CO2:CO ratio. All examined times are in the UTC time zone. The understory system’s complexity led to continuously varying MCE, which is depicted with rapid changes.

During flights #1, #3 and #4, the Sheep and Tucker fire plumes were categorized by Shrubland fuel types (dominant type–see Section S3 and S5), with MCE values > 0.9 (Figs. 5 and S11 and Figure S12), indicating that flaming was the dominant combustion phase, which is typical of rapidly-burning mixed shrubland-grassland fuel types burning under very high danger conditions24,25. Additionally, the correlation of CO with O3 and the ratios of CH4:CO2 and CO2:CO further supported the dominance of the flaming phase. Specifically, a positive correlation was observed between CO and O3, the CH4:CO2 ratio showed marginal changes, and the CO2:CO ratio was high (>2000)19,45,46. These indicators are consistent with characteristics of flaming combustion domination10,19,32,47. Notably the Tucker fire (F#3) presented with a wide range of MCE values, restricting the ability to identify a single dominant combustion phase. The CO2:CO ratio was generally high (>10), which was indicative to dominance of flaming combustion. However, in such cases, dilution and aging are key processes that influence the abundances of chemical species insider the plume. A high CO2:CO ratio reflects rapid dilution of CO relative to CO2, and/or oxidation of CO to CO2 during plume aging. Therefore, when the MCE is <0.9, a high CO2:CO may also reflect secondary chemical processing in addition to the combustion characteristics at the emission source.

During the BD, the North Hills (F#3) was classified as a Savanna ecosystem and the Shady (F#2) fire was classified an understory fire, (Fig. S11, Section S3 and S5). In both fires, the MCE varied, with values above and below 0.9, revealing mixed-phase (both flaming and smoldering) combustion. The correlations of O3 and CO did not show a clear tendency, with observations showing either an increase of CO at constant O3 concentrations or the opposite. The CH4:CO2 ratio exhibited marginal changes, while the CO2:CO ratio varied across low (<10) to very high values (>2000), especially in the understory system. These variations are reflective of the diverse fuel types and environmental conditions present in these systems. Additionally, the absence of a consistent pattern in examined gaseous and particulate species (Figs. 2–4 and S5–S9) supports the conclusion of mixed-phase combustion in these fire events.

Ridgetop (F#5) and Williams Flats (F#6) were classified as grassland fuel-type fires, with short-lived plumes. Combustion parameters (Fig. S11 and S13, section S5) revealed simultaneous flaming and smoldering combustion, especially evident in the Williams Flats fire during F#6. Although this fire plume was relatively fresh compared to the Ridgetop (F#5) (Fig. 1, Table 1), it exhibited a wider range to MCE and a distinct positive correlation between CO and O3. Additionally, there was a notable increase in CO concentrations at constant O3 levels. These observations include hallmarks of a mixed-phase combustion. Interestingly, this fire’s water vapor content was elevated (Fig. S9), similarly to the moderately aged Ridgetop fire plume, and in combination with its age allowed for simultaneous flaming and smoldering combustion19. In contrast to Williams Flats fire plume, Ridgetop was mainly dominated by flaming, as the MCE was \(\ge\) 0.9 (Fig. 5). Compared to shrublands, grasslands typically have a thin-diameter, uniform and horizontal structure, generating rapid ignition with fast spread and frequent flaming-dominate emissions and alternating flaming to smoldering combustion, dependent on fuel moisture48,49.

The forest categorized fire plumes, Left Hand (F#4), Lick Creek (F#5 and 6), Horsefly (F#7) and William Flats (F#7), were separated in flaming and mixed-phase combustion, due to the range of MCE and the CH4:CO2 ratio increases (Figs. 5 and S13, Section S5). This variability underscores the heterogeneity of forest fuel combustion and burn dynamics. Lick Creek (F#5) and William Flats (F#7) had low BC, relatively low CO and high WSOC content. In addition, the wide range of MCE values, positive correlation between O3 and CO and mainly high CO2:CO ratio, indicated mixed-phase combustion (Fig. S14). The combustion parameters for the rest of the forest fires showed clear domination of flaming combustion (Section S5).

Similar to Forest lands, mixed-fuel lands typically present a mixed-phased combustion (Fig. S11 and Figure S15), due to diverse fuel availability. The Barren Hills fire (F#4), classified as a mixture-fuel fire. During this flight the DC-8 aircraft sampled west, while the smoke had eastward direction, leading to sampling of a downwind mix of Tucker and other fires close to that direction. Sampling indicated dominance of the flaming phase (Fig. 5), with an MCE \(\ge\) 0.9, CO-O3 positive correlation and CO2:CO ratio \(\ge\)2000.

Therefore, it is observed that for the BD investigated fire plumes, purely smoldering-dominated fires (e.g., peatlands) were not sampled during FIREX-AQ. Although the fuel types differed, flaming combustion dominated the majority of examined plumes. The combination of combustion parameters presented herein allowed for efficient identification of the dominant combustion phase, with MCE constituting the key combustion parameter.

Discussion

The combustion phase association with the chemical composition of fire plumes determines the primary OAs emissions and thus influences the dominant OA chemical regimes. Two methods were used separately and in combination to determine the dominant OA chemical regimes of the examined fire plumes. While the parameters have been used independently to characterize OA chemical pathways, to our knowledge, their combination and the use of these two methods constitute a new approach in in-plume OA chemical regime identification.

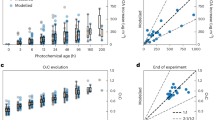

Although in-plume OA mass change provides direct evidence regarding the dominant regime, the investigation of combustion phase, particulate constituents and gas-species correlations during plume sampling provides necessary insights into OA dominate regime. Typically, fresh flaming combustion plumes are dominated by oxidation-driven evaporation28,30,31. Dilution-driven evaporation is often observed when smoldering dominates, due to insufficient time for oxidation, leading into a net decrease of OA mass shortly after emission due to evaporation50. These metrics constitute the initial method (method 1) of determination of dominant OA aerosol regime in this work. Figures 6 and S16 show calculated metrics that assist in determination of the OA regimes of selected fire plumes of each fuel category.

Panels a and b present the cases of Sheep and Left Hand fires, respectively. Change in CO and WSOC as a function of flight time (i), O3-CH4 correlation (ii), O3:CO ratio as a function of flight time, and (iv) RH during the sapling for selected fire plumes of a sheep and b left hand Figures S16 and S17 present the metrics for the rest of the examined fire plumes. The correlation between O3 and CH4, along with the O3:CO ratio, provided notable indications of the dominant in-plume OA regime. All examined times are in the UTC time zone.

Method 1 utilizes metrics (Figs. 6 and S16–S19) targeting the levels of WSOC, CO and RH, correlation of O3-WSOC and O3-CH4, WSOC:BC and O3:CO ratios and total carbon emissions (TCE). Evidence of simultaneous presence of both OA chemical regimes were observed for fresh, moderately aged and aged plumes. Specifically, Ridgetop (F#5–fresh plume), Tucker (F#3-aged and 4-moderetely aged) and Barren Hills (F#4-aged) plumes were characterized by varying evolution of WSOC, absence of correlation between O3 and WSOC, relative stability of O3:CO ratio and high RH. These metrics provided evidence of balance between oxidation-driven condensation and dilution-driven evaporation of OA. In Shady (F#2) and Williams Flats (F#6), spikes in WSOC concentrations (>200 μg m−3), relatively stable O3:CO and high CO levels, indicated dilution-driven evaporation as the main contributor to OA evolution. However, in this case as well, the two regimes existed simultaneously.

Two fire plumes, Sheep (F#1) and (F#4) presented with distinct OA chemical regimes (Fig. 6). Specifically, the Sheep fire plume (F#1), classified as a fresh plume of shrubland fuel dominated by flaming combustion, initially exhibited stable WSOC levels, low and stable RH, and no O3-WSOC correlation, all characteristics of dilution-driven evaporation (Figs. 6 and S17). However, the notable increase of WSOC and RH as the plume sampling progresses, along with increasing WSOC:BC ratio led to a shift towards oxidation-driven evaporation of OA. The elevated WSOC shows production of secondary OA via condensation, due to the presence of soluble species that condense into the particle phase28,30,31. Even though the Sheep fire is a flaming-dominat combustion plume, a two-phase OA evolution was observed due to dynamic interplay between evaporation of primary organic aerosol (POA) and formation of secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Specifically, a fresh flaming plume initially loses OA mass, due to dilution with ambient air, leading to evaporation of semi-volatile primary OA constituents. However, as the plume progresses and oxidation occurs, secondary OA is formed via condensation of oxidized vapors into particles. This condensation compensates for the loss of OA mass due to evaporation, resulting in domination of oxidation-driven condensation51,52. This dynamic interplay explains the observed lack of correlation between O3 and WSOC and the small increase of O3 with respect to CH4.

In contrast, the Left Hand fire (F#4), classified as an aged plume and dominated by flaming combustion showed a the transition from oxidation to dilution. Figure 6 presents a decrease in O3:CO ratio and RH, after an initial increase, and a positive O3-CH4 correlation as well as an increase in CH4 concentration at relatively constant O3 levels. In addition, O3 concentration logarithmically decreased with increasing WSOC concentration, while the WSOC:BC ratio dual direction with time (increase and simultaneous plateau), indicated initial oxidation-driven condensation of OA followed by dilution-driven evaporation, with the dilution-driven evaporation being more prominent. This is indicative of flaming combustion and aged plumes3,29,52.

Interestingly, the TCE (Fig. S20) generally decreased (up to 95%) as the plumes aged, indicating that dilution governed the OA fate as the plumes moved downwind. Exceptions include Shady (F#2) and Lick Creek (F#5). Shady (F#2) shows continual TCE change, with alternations as the plume aged. One potential reason for this could be more TCE was emitted at the time the fire was burning during those initial emissions. At 6-hrs old, the plume reached a 2-fold TCE lower peak of TCE, reaching 0.1 tC s−1 (Fig. S18). Thus, these alternations could be either attributed to sampling inside the plume (peaks of TCE) and at the edges of the plume (low TCE), or to alternation of OA regimes. The consecutive high TCE (0.2 tC s−1) followed by the decrease at 0.1 tC s−1, indicates balance of the two OA regimes and domination by dilution-driven evaporation, especially at \(\sim\)6 h. In contrast, the TCE of Lick Creek (F#5) were relatively stable for the initial 3 h, when TCE increased exponentially as the plume aged (Fig. S18). The TCE increase in combination with high WSOC and low WSBrC and BC (Figs. 2–4, Figure S18), reveal an interplay between the two OA regimes with major contributor dilution-driven evaporation, also supported by the increased CO concentrations (Fig. S7) and the absence of correlation between O3-CO (Figs. S16 and S17).

Due to the varying trends observed in method 1 and to evaluate the dominant OA chemical regimes, a second method (method 2), using the LACS concentrations was implemented, complementing method 1. The evolution of BC concentrations and WSBrC provide additional insights into the dominant OA regime, as decrease in WSBrC absorption and increase in BC loading inside the plume reveal the dominance of dilution-driven evaporation53,54. Figure S21 depicts the evolution of LACS concentrations and absorption during the sampling of the BD fire plumes. In the plumes of Sheep (F#1), North Hills (F#3), Tucker (F#3), Tucker (F#4) and Williams Flats (F#7) LACS exhibited relatively stable trends or marginal changes, restricting the evaluation of the dominant OA regime using these species. In contrast, the Shady plume (F#2) presented with variable BC levels and a marginal WSBrC absorption increase (with <1 Mm−1 absorption), consistent with dominating dilution-driven evaporation regime. Marginal decrease in average BC levels and relatively stable WSBrC absorption at 2.6 Mm−1 at the Barren Hill (F#4) plume, further suggested the dominance of dilution-driven evaporation of OA.

Ridgetop (F#5) and Horsefly (F#7) plumes were characterized by initially an increase in average BC concentration followed by a decrease during sampling, while the WSBrC absorption was initially relative stable (with marginal increase) and decreased significantly as the sampling progressed (Fig. S21). This indicates switching of the OA regimes within the plume. However, the balance between the two regimes was unclear. Interestingly, the average LACS trends were opposite for the cases of Left Hand (F#4) and Williams Flats (F#6). For the former, the two species increased in concentrations and absorptivity, while for the latter, a decrease was observed. Williams Flats (F#6) had higher WSBrC absorptivity (up to 10 Mm−1) and an order of magnitude higher average BC concentrations, indicating significant contribution to OA evolution from both oxidation-driven condensation and dilution-driven evaporation. The Left Hand OA evolution is likely dominated by dilution-driven evaporation, according to the LACS concentrations, which were in agreement with the findings of method 1.

Comparing the chemical species correlations and ratios method (method 1) with the LACS evolution method (method 2), revealed a general agreement in the identified OA chemical regimes. The combination of these methods provided key indications on the dominant OA chemical regimes of the fire plumes. Two fire plumes, Shady (F#2) and Left Hand (F#4), were identified as OA dilution dominated. Both plumes were aged, which likely enhanced dilution with background air. Notably, dilution can decrease in-plume temperature, shifting the gas-particle partitioning of available semi-volatile species and potentially enhancing condensation; thus, altering the regime and creating a new chemical balance. Both regimes were identified in the majority of the examined plumes, but their balance could not be conclusively evaluated.

Although these methods provide clues on the chemical mechanisms and dominant OA regime, the absence of linearity of OA processes, in-plume variability and measurement uncertainties lead to difficulties in determining the balance of in-plume OA regimes16,55. Both chemical processes (condensation and evaporation) often occur simultaneously, as observed in the examined fire plumes. The suppression of sunlight, due to heavy smoke, led to denser plumes and slower oxidation16, where dilution-driven evaporation becomes more prominent. Fuel type influences the initial chemical composition of the plume, determining the volatility of emitted organics, which in turn affects the OA evolution3,29. The use of the two methods showed no direct link between fuel type and the dominant OA regimes. This is likely attributed to the age of the plumes and uncertainties in the measured concentrations of the initial emissions. Specifically, the extent of dilution prior to sampling added difficulty in isolating the dominant OA regime.

The dynamic and complex chemical composition of fire plumes and the continuous alternation of chemical regimes, complicate the identification of dominant chemical pathways. However, the combined use of greenhouse gases, ozone, water-soluble organic carbon, total carbon emissions and LACS provided a comprehensive framework for evaluating dominant OA chemical regimes, especially during high-smoke conditions when in-plume photochemical activity is limited and shifting in OA regimes and plume dynamics become more pronounced. Building on this foundation, our follow-up study focuses on a targeted analysis of reactive, oxygenated, gaseous and particulate species measured during the 2019 FIREX-AQ field campaign.

Methods

FIREX-AQ 2019 filed campaign

The FIREX-AQ campaign was conducted in the western United States during mid and late summer (July–September). The aim of the campaign was to examine wildfire emissions, using aircraft instrumentation and mobile laboratories. Four aircraft were used: the DC-8, ER-2 and two Twin Otter. Details of the campaign are presented in Warneke et al.56. In this work, we focused on the DC-8 measurements, as presented below.

Data usage

The data utilized were collected by the DC-8 Airborne Science Laboratory. Seven flights and thirteen fire plumes were investigated focusing on the Boise (ID) Deployment. CO2 concentrations were obtained during the campaign by using the Non-dispersive IR Spectrometer (LICOR 700; 0.25 ppm accuracy and 0.1 ppm precision at CO2 < 500 ppm, and 2% total error at CO2 > 500 ppm) of the NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC). CO and CH4 measurements were obtained using the LaRC Diode Laser Spectrometer (CH4–20 ppbv uncertainty; CO-2 ppbv uncertainty). The Diode Laser Hydrometer from the NASA Langley Research Center provided measurements of water vapor (H2Ov: 5% uncertainty) and RH (15% uncertainty). O3 measurements were collected via the Ozone-Induced Chemiluminescence instrument of NOAA ESRL Chemical Science Division (2\(\sigma\) uncertainty). The NOAA Single-Particle Soot Photometer (SP2) of the ESRL Chemical Science Division was used to measure BC at 550 nm (20% uncertainty when bypassing the dilution system from flow to mass calibration and 40% when sampling behind the dilution system). Two methods of BrC and WSOC quantification were used as described in Zeng et al.57. In this work, we utilize the data obtained from the extraction of SAGA filters. Specifically, 15 mL aliquots in water were extracted, dried and re-extracted in 15 mL of methanol. The aliquots were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and then they were injected through a 2.5 m path length Liquid Waveguide Capillary Cell to measure the light-absorption, at wavelengths of 300–700 nm, by the Ocean Optics USB4000 spectrometer. Trajectory analysis was performed by the Florida State University Team to estimate plume rise and age.

Data analysis

In the present work, data available in the NASA Data Archive from the DC-8 Airborne Science Laboratory were retrieved and analyzed, focusing on BC, BrC, WSOC and trace gases (CO2, CO, CH4, O3). All data was used in accordance with the guidelines provided in the data archive (https://www-air.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/ArcView/firexaq).

Specifically, for the case of BrC, it was extracted from filters, and the raw data were further processed to obtain the absorption as:

Absorption = (Raw data)*(Volume of extraction liquid)/(Volume of collected air)/(Optical path length)*ln(10).

The data used were corrected using blank filters. The optical path length was 2.5 m. In addition, the absorption Ångström exponent (AAE) (equation [1]), for each fire plume, was calculated to correct the absorption (babs) by higher wavelengths (550 and 700 nm), as recommended. The data presented herein were corrected by the wavelength 550 nm to avoid baseline drift, as instructed by the data guidelines. Subsequently, the AAE was implemented in equation [2] to obtain the corrected absorption for the wavelength of interest (i.e., 365 nm). The AAE values for each flight in chronological order were 3.4, 6.2, 5.6, 4.2, 4.5, 5.2 and 6.2, respectively.

where babs is the absorption (Mm−1), AAE is the Ångström exponent, \({\rm{\lambda }}\) is the wavelength (nm), and cs is the constant resulting from the integration solution of equation [2].

Plume age and height

The average estimated age range was used to characterize of the plume age (i.e., fresh, moderately aged and aged) were achieved considering the average estimated range. The age was estimated considering DC-8 measurements of latitude, longitude and altitude, and the upwind trajectories computed using HYSPLIT and compared with GEOS satellite data. Wind speed corrections were applied, and the age was calculated as the average age of the considered meteorological datasets, omitting any unrealistic values. The examined plumes’ presented age values spanned across fresh and aged categories. To characterize the plume’s age, the average age during the sampling time was considered. Thus, the reported characterisation refers to the main age classification of the examined plumes.

The plume heights were estimated using HSRL data. Parcel initial locations were taken from aircraft location data. Aerosol parcels were modeled back to the point of emissions to determine age or wind/environment. The plume height to trajectory altitude was determined as the difference between the trajectory altitude at the measurement location and the surface altitude. The highest point of the plume was subsequently estimated as the sum of the trajectory altitude and the plume height above the trajectory altitude.

Detailed information is provided in the NASA Data Archive (see Data availability section).

Modified combustion efficiency

MCE was used as a metric to determine the combustion phase of the fire plumes:

When MCE is \(>\)0.9 the dominant combustion phase is flaming, while when MCE < 0.9 the dominant phase is smoldering19,24,25. Typically, low MCE within the range of \(\sim\)0.65–0.85 corresponds to smoldering combustion and MCE = 0.95 suggest strong flaming combustion. Pure flaming combustion is achieved at MCE = 0.99, while at MCE = 0.9 a roughly equal contribution of flaming and smoldering occurs19,24,25.

Data availability

All initial data used in the present study are available at the NASA Data Archive (https://www-air.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/ArcView/firexaq). The data availability is “open access” and falls under the FIREX-AQ policy and NOAA/NASA protocols. The processed data generated in this work is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Reid, C. E. et al. Health impacts of wildfire smoke. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1334–1343 (2016).

Voulgarakis, A. & Field, R. D. Fire influences on atmospheric composition, air quality and climate. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 1, 70–81 (2015).

Hodshire, A. L. et al. Aging effects on biomass burning aerosol mass and composition: a critical review of field and laboratory studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10007–10022 (2019).

Saunois, M. et al. Global methane budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 17, 1873–1958 (2024).

Andreae, M. O. & Merlet, P. Emissions of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Glob. Biochem. Cycles 15, 955–966 (2001).

Voulgarakis, A. et al. Interannual variability of tropospheric composition: the influence of changes in emissions, meteorology and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 2491–2506 (2010).

Crutzen, P. J., Lawrence, M. G. & Pöschl, U. On the background photochemistry of tropospheric ozone. Tellus 51A-B, 123–146 (1999).

Alvarado, M. J. et al. Investigating the links between ozone and organic aerosol chemistry in a biomass burning plume from a prescribed fire in California chaparral. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6667–6688 (2015).

Choi, M. et al. Light-absorbing black carbon and brown carbon components of smoke aerosol from DSCOVR EPIC measurements over North America and central Africa. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 10543–10565 (2024).

Jaffe, D. A. & Wigder, N. L. Ozone production from wildfires: a critical review. Atmos. Environ. 51, 1–10 (2012).

Lee, H. J. et al. Effect of solar radiation on the optical properties and molecular composition of laboratory proxies of atmospheric brown carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10217–10226 (2014).

Zhong, M. & Jang, M. Dynamic light absorption of biomass-burning organic carbon photochemically aged under natural sunlight. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 1517–1525 (2014).

Zhao, R. et al. Photochemical processing of aqueous atmospheric brown carbon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6087–6100 (2015).

Andreae, M. O. & Gelencsér, A. Black carbon or brown carbon? The nature of light-absorbing carbonaceous aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3131–3148 (2006).

Ditas, J. et al. Strong impact of wildfires on the abundance and aging of black carbon in the lowermost stratosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E11595–E11603 (2018).

Decker, Z. C. J. et al. Nighttime and daytime dark oxidation chemistry in wildfire plumes: An observation and model analysis of FIREX-AQ aircraft data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 16293–16317 (2021).

Su, J. et al. Seasonal and day-night variations in carbonaceous aerosols and their light-absorbing properties in Guangzhou, China. Atmosphere 14, 1545 (2023).

Decker, Z. C. J. et al. Box model analysis initialized with aircraft observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 2529–2538 (2019).

Akagi, S. K. et al. Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4039–4072 (2011).

Christian, T. J. et al. Comprehensive laboratory measurements of biomass-burning emissions: 1. Emissions from Indonesian, African, and other fuels. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4719 (2003).

Stockwell, C. E., Veres, P. R., Williams, J. & Yokelson, R. J. Characterization of biomass burning emissions from cooking fires, peat, crop residue, and other fuels with high-resolution proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 845–865 (2015).

Wang, T., Meng, K., Fu, P. & Huang, W. Crop residual burning correlations with major air pollutants in mainland China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1–14 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Inventory of atmospheric pollutant emissions from burning of crop residues in china based on satellite-retrieved farmland data. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 30, 266–278 (2020).

Hsieh, Y. P., Bugna, G. & Robertson, K. Thermochemical properties of PM2.5 as indicator of combustion phase of fires. Atmosphere 9, 1–14 (2018).

Wu, Y. et al. The role of biomass burning states in light absorption enhancement of carbonaceous aerosols. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Atkinson, R. & Arey, J. Gas-phase tropospheric chemistry of biogenic volatile organic compounds: a review. Atmos. Environ. 37, 197–219 (2003).

Tomsche, L. et al. Measurement report: emission factors of NH3 and NHx for wildfires and agricultural fires in the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 2331–2343 (2023).

Pankow, J. F. An absorption model of gas/particle partitioning of organic compounds in the atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 28, 185–188 (1994).

Garofalo, L. A. et al. Emission and evolution of submicron organic aerosol in smoke from wildfires in the western United States. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 1237–1247 (2019).

Robinson, A. L. et al. Rethinking organic aerosols: Semivolatile emissions and photochemical aging. Science 315, 1259–1262 (2007).

Donahue, N. M., Robinson, A. L., Stanier, C. O. & Pandis, S. N. Coupled partitioning, dilution, and chemical aging of semivolatile organics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 2635–2643 (2006).

Akagi, S. K. et al. Evolution of trace gases and particles emitted by a chaparral fire in California. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 1397–1421 (2012).

Palm, B. B. et al. Spatially resolved photochemistry impacts emissions estimates in fresh wildfire plumes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095443 (2021).

Sedlacek, A. J. et al. Using the black carbon particle mixing state to characterize the lifecycle of biomass burning aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14315–14325 (2022).

Veira, A., Kloster, S., Wilkenskjeld, S. & Remy, S. Fire emission heights in the climate system - Part 1: Global plume height patterns simulated by ECHAM6-HAM2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 7155–7171 (2015).

Veira, A., Kloster, S., Schutgens, N. A. J. & Kaiser, J. W. Fire emission heights in the climate system - Part 2: Impact on transport, black carbon concentrations and radiation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 7173–7193 (2015).

Kahn, R. A. et al. Multiangle imaging spectroradiometer global aerosol product assessment by comparison with the aerosol robotic network. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, (2010).

Peterson, D. A. et al. Wildfire-driven thunderstorms cause a volcano-like stratospheric injection of smoke. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 1–8 (2018).

Jaffe, D. A. et al. Wildfire and prescribed burning impacts on air quality in the United States. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 70, 583–615 (2020).

Feng, X. et al. Can light absorption of black carbon still be enhanced by mixing with absorbing materials?. Atmos. Environ. 253, 118358 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Chemical tomography in a fresh wildland fire plume: a large Eddy simulation (LES) study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, 1–21 (2021).

Selimovic, V. et al. Aerosol optical properties and trace gas emissions by PAX and OP-FTIR for laboratory-simulated western US wildfires during FIREX. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 2929–2948 (2018).

Seinfeld, J. H. & Pandis, S. N. Atmospheric chemistry and physics: from air pollution to climate change, 3rd Edn. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development vol. 40 (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2016).

Urbanski, S. Wildland fire emissions, carbon, and climate: emission factors. Ecol. Manag. 317, 51–60 (2014).

Urbanski, S. P., Hao, W. M. & Nordgren, B. The wildland fire emission inventory: Western United States emission estimates and an evaluation of uncertainty. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 12973–13000 (2011).

Yokelson, R. J. et al. Emissions from biomass burning in the Yucatan. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 5785–5812 (2009).

Voulgarakis, A. et al. Global multi-year O3-CO correlation patterns from models and TES satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 5819–5838 (2011).

Vallet, L. et al. Soil smoldering in temperate forests: a neglected contributor to fire carbon emissions revealed by atmospheric mixing ratios. Biogeosciences 22, 213–242 (2025).

Owsley-Brown, F., Wooster, M. J., Grosvenor, M. J. & Liu, Y. Can the remote sensing of combustion phase improve estimates of landscape fire smoke emission rate and composition?. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 6247–6264 (2024).

Grieshop, A. P., Logue, J. M., Donahue, N. M. & Robinson, A. L. Physics Laboratory investigation of photochemical oxidation of organic aerosol from wood fires 1: measurement and simulation of organic aerosol evolution. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1263–1277 (2009).

Hodshire, A. L. et al. More than emissions and chemistry: fire size, dilution, and background aerosol also greatly influence near - field biomass burning aerosol aging. Atmospheres 124, 5589–5611 (2019).

June, N. A. et al. Aerosol size distribution changes in FIREX-AQ biomass burning plumes: the impact of plume concentration on coagulation and OA condensation/evaporation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 12803–12825 (2022).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380–5552 (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Enhanced light absorption by mixed source black and brown carbon particles in UK winter. Nat. Commun. 6, 8435 (2015).

Hodshire, A. L. et al. Dilution impacts on smoke aging: evidence in Biomass Burning Observation Project (BBOP) data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 6839–6855 (2021).

Warneke, C. et al. Fire influence on regional to global environments and air quality (FIREX-AQ). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, 1–62 (2023).

Zeng, L. et al. Characteristics and evolution of brown carbon in western United States wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys 22, 8009–8036 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Glenn S. Diskin for the archive CO2, CH4, CO, and H2Ov data, Ilann Bourgeois, Jeff Peischl and Tom Ryerson for the O3 archive data, Rodney Weber for the BrC and WSOC archive data, Joshua P. Schwarz and Joseph M. Katich for the BC archive data, and Christopher D. Holmes for the plume age and rise archive data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.D. and A.V. conceptualized this work, A.S. and E.G. provided the original ecosystem data, E.D. conducted the data collection and analysis, E.D. wrote the original draft, and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dovrou, E., Soja, A.J., Gargulinski, E. et al. Decoding clues on dominant combustion phase and aerosol chemical regimes via key tracers of fire plumes. npj Clean Air 1, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00032-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00032-7