Abstract

Amid growing concerns over the persistence of organic contaminants, this study examines the influence of land-use patterns on their distribution in the Oconee River watershed, Georgia. Surface water samples from five sites across urban, recreational, and forested areas of Georgia’s Oconee River watershed were analyzed for 22 organic contaminants, including pesticides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Contaminant concentrations varied, with Acenaphthene (max: 19,462.04 ng/L), Chrysene (max: 984.10 ng/L), and Naphthalene (max: 2428.06 ng/L) being predominant. Atrazine (max: 171.04 ng/L) and Malathion (max: 114.99 ng/L) were the most detected pesticides. Land use and land cover significantly influence organic contaminant distribution, with higher levels in forested and urban areas. Risk Quotient (RQ) analysis confirmed no contaminants surpassed the critical threshold, though cumulative exposure may pose long-term risks. The study emphasizes the need for targeted monitoring and regulatory efforts to safeguard water quality in river systems influenced by diverse land-use practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Various parameters related to land use (LU) and land cover (LC) and anthropogenic activities drive the deterioration of the ecological health of freshwater ecosystems1. These parameters include habitat degradation, the introduction of invasive species, and pollution from numerous chemicals2,3,4,5. Freshwater systems are facing increasing contamination from anthropogenic chemicals that are released into the environment. This is one of the major environmental problems today, with more than one-third of Earth’s renewable freshwater being used for agricultural, industrial, and domestic purposes—activities that often contribute to water pollution with a wide range of synthetic compounds. The chemical pollution of natural waters has become a global public concern because its long-term effects on aquatic life and human health remain largely unknown6,7,8,9,10. Among these contaminants are emerging organic contaminants (EOCs), which encompass a diverse range of chemicals used in various anthropogenic activities or newly introduced in commercial processes or industrial applications10,11,12,13. This broad category can include compounds found in cosmetics and perfumes that do not naturally decompose as they move through urban sewer systems to wastewater treatment plants, where they often remain unaffected or only partially degraded. This means they can eventually be discharged into local rivers. EOCs can also be partially metabolized pharmaceutical products, degradation byproducts of various man-made organic compounds, new pesticides on the market, cleaning products, or reagents and byproducts from industrial processes. The continual advancement of analytical techniques and the emergence of new technologies have made it possible to detect these compounds in aquatic environments, whether they are new chemicals or previously existing ones that have gone undetected. The list of EOCs is extensive, with some estimates reaching over 50,000 compounds14. Due to their wide-ranging origins, EOCs can have unpredictable environmental and ecotoxicological impacts, driving the need for extensive monitoring and continuous research11,15,16. Regularly published reviews and analytical trends highlight the latest findings in this rapidly evolving field10,12.

Numerous studies have highlighted the profound impact of land use and land cover and anthropogenic activities on riverine water quality, particularly surface water, across diverse geographic regions. Agricultural activities have been closely linked to the deterioration of surface water quality in the Songhua River Basin, China, emphasizing the role of nutrient runoff and chemical pollution17. In the Suquía River, Argentina, LU/LC and land cover changes were found to significantly influence the chemical composition and ecological health of surface waters18. Similarly, poor agricultural management practices have been identified as key contributors to pesticide contamination and nutrient over-enrichment in the surface waters of the Acacias River basin, Colombia19. The dynamic impacts of LU/LC on water quality were further explored in the Huaihe River Basin, China, where seasonal variations revealed that urbanization exacerbates surface water pollution during specific periods20. In the Ganges Basin, India, in Mun River Basin, Thailand, and also in Rio Grande, widespread contamination from persistent organic pollutants (POPs) indicated the significant influence of LU/LC on surface water quality, posing exposure risks to both ecosystems and human populations9,21,22,23,24. Collectively, these studies indicate that land use and land cover patterns are a primary driver of surface water quality changes, necessitating advanced monitoring techniques and sustainable management practices to mitigate pollution risks. Table 1 contains the detailed overview of global studies on land use and land cover impact on surface water quality.

The present study aims to conduct a broad-spectrum quantitative analysis of various emerging organic contaminants across riverine system of Georgia, focusing on the Oconee River watershed. A recent publication, based on extensive temporal sampling, analyzed whether the North Oconee River in Georgia presents a significant environmental risk25.

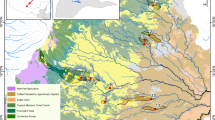

The Oconee River watershed, originating in Hall County, Georgia, is a significant hydrological system that spans approximately 5330 square miles and supports a diverse range of water uses. The river’s headwaters comprise the Middle Oconee and North Oconee rivers, which flow for 55–65 miles before merging near Athens to form the Oconee River26 (Fig. 1). This river flows freely for about 143 miles before joining the Ocmulgee River to create the Altamaha River, after being impounded by two major reservoirs: Lake Oconee and Lake Sinclair. The watershed also supports municipal, industrial, agricultural, and energy uses, providing drinking water for over 281,000 people through 14 surface water intakes. It is home to substantial agricultural activity, with nearly 20,000 acres of irrigated farmland and numerous animal operations, which contribute significantly to water demand. The watershed’s hydrology is further shaped by over 5000 small impoundments, influencing both water availability and quality.

This watershed is crucial to the study of emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in riverine systems due to its extensive industrial, agricultural, and municipal water usage, which can introduce pollutants27,28. While there has been significant research on regular water quality monitoring, there is a gap in understanding the occurrences of overall organic contaminants in such a diverse system. Given the reliance on the Oconee River for drinking water and the presence of various potential contamination sources, there is a pressing need for research on the presence of such contaminants within the watershed. This research is essential to address the risks posed to human health and ecosystems, providing insights into pollution control and sustainable water management practices.

This study focuses on an in-depth examination of the quantitative evaluation of organic compounds within the North Oconee River and Oconee River watershed in and around Athens-Clarke County, Georgia, USA (Fig. 1). The research addresses two key questions:

-

i.

At what extent organic contaminants are commonly found in the waters, which is a critical drinking water source for the region?

-

ii.

What factors influence the distribution of organic contaminants in the study area?

Results and Discussion

Extent of organic compounds in riverine system of Georgia

A total of 15 compounds were detected in all locations and in 90% of the sampling events. The sampling events varies between five sampling locations. FT has 8 sampling events, followed by SC (7), WTP (6), OR (4), and RM (3) (Table 2). The Table 2 provides detailed data on the concentrations of various contaminants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides, and other organic compounds, across different locations and sampling periods. Some compounds, including 4,4 DDT, aldrin, α-BHC, dieldrin, endrin, heptachlor, and lindane, were all recorded at below detection limit (Table 2, Supplementary information Table: S2–S6).

In FT, the concentration trends suggest significant inputs of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and pesticides. Acenaphthene, anthracene, and naphthalene exhibited elevated levels, with acenaphthene reaching up to 14,945.09 ng/L, indicating possible urban stormwater runoff or industrial sources. The relatively high concentrations of atrazine (mean: 133.55 ng/L) and methoxychlor (mean: 475.57 ng/L) suggest persistent domestic wastewater and stormwater influence. Interestingly, the high standard deviation for PAHs like anthracene and fluoranthene points to variable episodic discharges, potentially from the stormwater influx. Nicotine was also present at notable levels (mean: 426.74 ng/L), indicating anthropogenic contributions, possibly from wastewater effluents. These patterns underscore the combined influence of urbanization and industrial activities in this region.

In the RM site, Acenaphthene levels remained high (mean: 13,164.66 ng/L), indicating sustained urban stormwater input. PAHs such as anthracene (mean: 937.28 ng/L) and fluoranthene (mean: 843.45 ng/L) were prevalent, highlighting combustion-derived pollution. Atrazine (mean: 131.36 ng/L) and methoxychlor (mean: 458.95 ng/L) suggested continuous domestic wastewater influence. Interestingly, nicotine levels (mean: 547.12 ng/L) were similar FT, implying a contribution from the direct discharge of stormwater runoff for both locations.

In WTP, contaminant levels were generally lower than in FT, but some compounds, particularly PAHs, remained prevalent. Acenaphthene and anthracene concentrations were lower than in FT (mean: 9173.18 ng/L and 2660.77 ng/L, respectively), suggesting a dilution effect or reduced input sources. Atrazine (mean: 94.04 ng/L) was present at a lower concentration than in FT. Interestingly, benzo[β]fluoranthene exhibited a higher mean concentration (45.37 ng/L) compared to FT, suggesting a more localized source, possibly linked to vehicular emissions or fuel combustion residues. The presence of malathion (mean: 14.07 ng/L) aligns with expected pesticide use, though its relatively low variation suggests a more stable input. The data suggests that WTP has a diverse range of pollution sources, but likely experiences dilution from hydrological factors. WTP is strategically located at a point where the river, before a steep elevation drop, experiences a sudden change in flow dynamics.

In SC, overall contaminant levels were notably lower, with acenaphthene and anthracene concentrations dropping significantly compared to FT and WTP (mean: 631.71 ng/L and 1362.79 ng/L, respectively). The lower atrazine levels (mean: 11.78 ng/L) indicate minimal agricultural runoff in this area. A striking feature of SC’s data is the significantly lower presence of endosulfan, methoxychlor, and benzo[β]fluoranthene, which may indicate effective degradation, sedimentation, or source control in this environment. However, naphthalene (mean: 1139.70 ng/L) still remained prominent, suggesting contributions from atmospheric deposition or legacy contamination. The overall data points to reduced pollutant loading, likely due to natural attenuation processes and the absence of major anthropogenic inputs.

In OR, contaminant concentrations were markedly higher than in all other sites, with acenaphthene reaching a maximum of 19,462.04 ng/L, suggesting intensive industrial or urban runoff sources. The substantial levels of anthracene (mean: 4610.96 ng/L) and benzo[β]fluoranthene (mean: 137.32 ng/L) indicate strong combustion-related pollution. The consistently high levels of atrazine (mean: 158.42 ng/L) and methoxychlor (mean: 2128.67 ng/L) support the likelihood of sustained agricultural activity contributing to pesticide presence. The elevated nicotine concentrations (mean: 1429.78 ng/L) further reinforce the role of wastewater contributions. The data suggests that OR is a hotspot for both industrial and agricultural contamination, potentially requiring targeted mitigation strategies.

The data shows significant differences in the concentrations of various compounds at different sites, indicating distinct environmental or operational conditions (Supplementary Table 1–6). For example, acenaphthene concentrations are highest at OR which is located downstream suggests potential localized sources of pollution or variations in contamination levels compared to other sites. Similarly, compounds like anthracene and fluoranthene show significant fluctuations, possibly indicating differing pollution sources or degradation processes at each location. Variability in other compounds, such as nicotine and methoxychlor, further highlights the diverse impacts across the sites. Overall, these observations suggest that localized factors, specifically LU/LC, might have a significant impact on the presence and concentration of pollutants, underscoring the need for site-specific investigations to understand the sources and mechanisms of contamination.

The presence of nicotine at FT and WTP locations suggests urban contamination, with the highest concentration recorded at 2428.059 ng/L in FT in February 2024. This points to urban stormwater runoff, possibly from fresh tobacco smoke product waste, as a significant contributor to water contamination. Additionally, atrazine, a commonly used agricultural herbicide, is found in varying concentrations across locations, peaking at 171.040 ng/L in OR in April 2024, highlighting the influence of agricultural runoff, particularly in areas near farming activities. Notably, 4,4 DDT was not detected in any samples, suggesting limited recent contamination due to its long-standing ban in many regions. However, the intermittent presence of lindane in OR indicates ongoing but limited usage or residual contamination from past applications. The presence of these pesticides, particularly in industrial and agricultural zones, underscores the persistence of legacy pollutants despite regulatory efforts.

The spatial distribution of contaminants, with OR consistently showing the highest concentrations, indicates the significant impact of agricultural activities on local water quality. The chord diagram illustrates a clear relationship between LU/LC and the presence of organic contaminants in river water (Fig. 2). The thickness of the chord represents the magnitude of the connection between pesticide concentration and land-use. The data show that organic contaminants are most abundant in OR, compared to those in urban or recreational areas. In contrast, rivers in urban areas, such as those sampled surrounding Athens at WTP, RM, and FT, also showed significant contaminant levels but mostly lower than those in forested regions. The lowest concentrations were observed in recreational areas like SC, which suggests that LU/LC practices associated with recreation might be less impactful on contaminant levels compared to forested and urban areas. This gradient in contaminant abundance aligns with the chord diagram’s representation, highlighting that land use and land cover significantly influences the presence and concentration of organic contaminants in river water.

Chord diagram representing the relationships between organic contaminants across different sampling sites. Ace- Acenaphthene, Ant - Anthracene, Atr - Atrazine, Benz-a - Benz-a-anthracene, Benz.b - Benzo-b-fluoranthene, Chr - Chrysene, End - Endosulphan, Flthene - Fluoranthene, Fluor - Fluorene, Mal - Malathion, Meoxy - Methoxychlor, Nap - Naphthalene, Nic - Nicotine, Phen - Phenanthrene, Pyr – Pyrene.

The boxplot analysis represents significant variation in organic contaminant concentrations across distinct land-use categories such as forest, recreational, and urban, highlighting the impact of anthropogenic activity on environmental pollution (Supplementary Fig. 1). The application of the Kruskal-Wallis test indicates statistically significant differences for many of these contaminants, underscoring the influence of land-use patterns on contaminant distribution.

Higher contaminant concentrations in forested areas compared to urban and recreational zones can be attributed to several natural processes and land management factors. One key reason could be potential atmospheric deposition and adsorption. Soils in forest areas tend to be rich in organic material, which can trap pollutants more effectively than in urban or recreational settings. Alternatively, as per the previous report of Athens Clarke County, most of the present forest area are young forests and those areas used to serve as agricultural farmland before 195029. The present contamination at OR specifically the PAHs possibly be the legacy contaminants from previous LU/LC. Moreover, the location of OR is far more downstream than other locations. As contaminants move through waterways, downstream areas often experience higher concentrations due to the cumulative effects of upstream pollutant sources. Urban environments consistently exhibit higher concentrations of organic contaminants, with large interquartile ranges and pronounced outlier’s indicative of intermittent high-level pollution events than that of recreational settings. These elevated levels are likely attributed to increased human activity, including vehicular emissions, industrial processes, and stormwater runoff. Methoxychlor (p = 0.03), naphthalene (p = 0.0014), and nicotine (p = 0.03) demonstrate particularly higher concentrations in urban areas, reinforcing the association between urbanization and pollutant accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Recreational areas, though intermediate in contamination levels, exhibit concentrations more closely aligned with urban environments, likely due to human usage and proximity to urban centers. The statistical significance of these findings emphasizes the necessity for targeted land-use management strategies to curb the spread of organic contaminants, particularly in urban areas where pollutants are most concentrated.

Impact of land-use on organic contaminant distribution in watersheds

The principal component analysis (PCA) and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plots specify clear distinctions in contamination levels across different sites, particularly between SC and OR. These two sites exhibit the greatest separation in terms of dimensions 1 and 2 on the PCA plot, which correlates with their differing levels of organic contaminants. Specifically, the OR site, located along the Oconee River, shows significantly higher contamination compared to SC, which is associated with Lake Chapman. This suggests a higher pollution load in the Oconee River downstream, likely influenced by the surrounding LU/LC and activities (Figs. 3 and 4; Supplementary Figs. 2–4).

In contrast, the SC site, appears as a distinct entity in both the PCA and PCoA plots respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). While SC may have some interaction with the North Oconee River, such as during heavy rainfall, it is mostly considered a separate water body with its own contamination profile. The organic contaminants detected in SC are the lowest among the studied sites, further reinforcing its distinct status. Physicochemical parameters from different LU/LC indicated a clear distinction between river and lake (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Water treatment plant (WTP), river mill (RM), and firefly trail (FT), all located along the North Oconee River, exhibit similar contamination levels and cluster closely in the PCA plot. These similarities suggest that these sites are subject to comparable environmental factors and pollution sources. However, OR stands apart from these sites, as it is situated downstream of the North Oconee River, which receives more pollution load, likely due to the cumulative impact of upstream activities and runoff.

The PCoA plot also supports the finding that SC, as lake water, has a separate contamination profile compared to the other four sites along the North Oconee and Oconee rivers. The separation of SC from the other sites highlights its unique contamination dynamics, possibly due to limited interaction with the rivers except during wet periods.

Additionally, the chord diagram further emphasizes the influence of LU/LC on contamination levels. The proximity of WTP, RM, and FT in the PCA plot suggests that similar land-use patterns and human activities, such as urban runoff, industrial discharge, or agricultural practices, are contributing to their contamination profiles. In contrast, OR, located further downstream, bears the brunt of accumulated pollution, underscoring the importance of land cover and its impact on water quality across different watershed sites.

Identifying potential sources of organic contaminants

The analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in water samples revealed significant variations in PAH concentrations, which provide insights into their potential sources. The ratios of Flu/(Flu + Pyr) and Ant/(Ant + Phe) were calculated to assess the origins of the PAHs, and the results strongly indicate a pyrogenic origin. Specifically, an Ant/(Ant + Phe) ratio greater than 0.1 is indicative of pyrogenic PAHs, suggesting that the PAHs are primarily derived from the incomplete combustion of organic matter, including coal, petroleum, and wood (Fig. 5)30,31.

The Flu/(Flu + Pyr) ratio exceeded 0.5, which further supports the presence of pyrogenic PAHs. This is consistent with the Benzo[α]anthracene/(Benzo[α]anthracene + Chrysene) ratio, which was also above 0.35, reinforcing the conclusion that the PAHs present in the studied regions are predominantly of pyrogenic origin. The prevalence of pyrogenic PAHs across various locations, regardless of LU/LC, suggests that these compounds are more common than petrogenic PAHs in the sampled environments. Petrogenic PAHs, typically derived from unprocessed coal or crude oil, form over geologic time scales at low temperatures and are less likely to be the primary contributors in this context. In contrast, pyrogenic PAHs are closely linked to anthropogenic activities such as forest fires, garbage incineration, and vehicle emissions. The dominance of pyrogenic PAHs highlights the significant impact of human activities on PAHs distribution in the environment.

The analysis of organic contaminants across all sites showed that 15 out of 22 organic compounds were consistently detected, highlighting persistent contamination issues. Six organic contaminants—4,4’-DDT, aldrin, α-BHC, endrin, dieldrin, heptachlor, and lindane—were not detected, possibly due to their ban on usage in the United States. Variability in concentrations, notably higher levels of acenaphthene and anthracene at OR, suggests localized sources of pollution or differences in contamination intensity. These findings emphasize the widespread and persistent nature of these pollutants in the studied environments. However, none of the contaminants showed a concentration higher than the drinking water permissible limit by USEPA. Land use and land cover play a critical role in contaminant distribution, with agricultural and forest sites such as OR showing elevated levels compared to recreational areas like SC. This correlation underscores the impact of LU/LC practices on water quality. The chord diagram and PCA analysis illustrate how agricultural runoff and urban activities contribute significantly to contaminant levels, indicating that LU/LC management is crucial for mitigating pollution. The analysis of PAHs indicated a dominance of pyrogenic sources, primarily from anthropogenic activities such as incomplete combustion of organic materials. This suggests that human activities, including forest fires, industrial emissions, and vehicle exhaust, are major contributors to PAHs pollution. In contrast, petrogenic sources were less prevalent, reinforcing the significance of pyrogenic sources in these regions.

Chemical indicators for assessment of organic contaminant load

Each node in the network diagram (Fig. 6) represents an organic contaminant detected in the study, and the edges (lines connecting the nodes) represent significant correlations between these contaminants. The size of each node indicates the average concentration of the organic contaminant detected across the samples, while the color of the edges represents the strength of these correlations (bluer colors have a higher correlation). Malathion, in particular, identifies as the most connected contaminant in this network, indicating its significant role in determining the occurrence of other organic contaminants within the studied system.

The color of the edges represents the Pearson correlation coefficient. The higher the correlation coefficient between two organic contaminants, the bluer the color of the node; the lower the correlation coefficient, the yellower the color. The Pearson coefficient considered for this co-occurrence figure is >0.7. The size of the nodes represents the average concentration of the organic contaminant across all the samples.

The edges connecting these nodes vary in color, reflecting the strength of the correlations between contaminants. Bluer lines represent stronger correlations, while yellower lines indicate weaker correlations. These variations in correlation strength provide insight into the complexity of interactions between contaminants. Strong correlations may imply that these compounds are released together or undergo similar transport mechanisms in the environment, while weaker correlations may suggest more independent behavior.

Malathion, represented by a highly connected node, is central to the network, showing correlations with many other contaminants such as fluoranthene, acenaphthene, anthracene, methoxychlor, and benzo[α]anthracene. This high degree of connectivity suggests that malathion may be influencing or co-occurring with these compounds due to shared environmental pathways or sources. For instance, malathion, a widely used organophosphate pesticide, could be entering the environment through agricultural or stormwater runoff and subsequently interacting with other organic contaminants. The significant correlation of malathion with multiple contaminants indicates that its presence might serve as an indicator for broader contamination issues in the study area. Since malathion is a known environmental pollutant with agricultural practices and domestic origins, its widespread correlation with other organic compounds could point to either agricultural practices or pesticide use for domestic purposes, such as for gardening, as major contributors to the contamination profile observed across the study area.

The network also shows distinct clusters of contaminants that are strongly interconnected. For example, contaminants like anthracene, benzo[α]anthracene, and chrysene form a closely related group. These compounds are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), typically associated with industrial activities or fossil fuel combustion. The clustering of these contaminants suggests that they may share common sources or exhibit co-occurrence due to similar environmental processes, such as deposition from industrial emissions or incomplete combustion byproducts entering the water system. Malathion’s strong correlation with this group of PAHs implies potential overlapping contamination sources. Agricultural areas may be exposed to both pesticide applications and industrial or urban runoff, leading to the co-occurrence of these compounds. Additionally, this clustering indicates that efforts to monitor or remediate one contaminant could also address others in the group, especially in areas where mixed sources of contamination are suspected.

Another important aspect of the network diagram is the identification of isolated groups, such as the pair of naphthalene and phenanthrene, which are not connected to the larger network (Fig. 6). This isolation indicates that these two contaminants do not share significant correlations with the other detected contaminants. Such isolation could suggest that naphthalene and phenanthrene are influenced by distinct sources or processes that differ from those affecting the more interconnected contaminants in the network. For instance, these compounds may originate from localized contamination events or specific industrial sources that are not contributing to the broader contamination patterns observed in the study. This network diagram provides valuable insights into the relationships between detected organic contaminants in the environment. The central role of malathion, along with its significant correlations with a variety of other compounds, suggests that it could serve as an indicator of broader contamination trends. Monitoring malathion could help track the presence of other organic contaminants, making it a useful target for environmental monitoring programs.

The clustering of certain contaminants highlights the potential for shared sources or similar environmental pathways, offering guidance for source tracking and mitigation efforts. For instance, contaminants in the same cluster may originate from industrial emissions, urban runoff, or agricultural activities, requiring coordinated management strategies to address multiple contaminants simultaneously. Additionally, the presence of isolated pairs, such as naphthalene and phenanthrene, suggests that certain contaminants may behave independently in the environment. These isolated compounds may require separate investigation to identify their specific sources and to understand why they are not correlating with the broader contaminant network.

Assessing site-specific contaminant exposure and ecological risk

The risk quotients (RQs) calculated up to 3 decimal points for various organic contaminants across the five sampling sites (FT, WTP, SC, OR, and RM) indicate site-specific variations in potential ecological risk. OR stands out with elevated RQs for acenaphthene (0.025), anthracene (0.171), atrazine (0.003), fluoranthene (0.045), and methoxychlor (0.106), suggesting higher contamination levels that may pose environmental risks, although none exceed the critical threshold of 1 (Table 3). Pyrene, a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAHs), shows consistent presence across all sites, with RQs ranging from 0.001 at SC to 0.006 at FT, suggesting a widespread, though low-level, contamination. The RQs below 1 generally indicate a low risk of acute toxic effects at all sites, but the cumulative exposure to multiple chemicals should not be overlooked, as even sub-threshold contaminants can interact and lead to long-term ecological impacts.

The elevated RQ values observed at OR may be linked to specific local activities or land-use patterns that contribute to higher contaminant loads. Atrazine, commonly associated with agricultural runoff, shows the highest RQ at OR, potentially pointing to nearby agricultural operations or pesticide use. Fluoranthene and acenaphthene, both PAHs, are likely derived from combustion processes or industrial discharges, which could explain their relatively high levels at this site. The detection of methoxychlor at concentrations of concern suggests legacy pollution or ongoing low-level inputs. The widespread occurrence of pyrene at multiple sites reflects the pervasive nature of PAHs pollution, often tied to vehicular emissions and urban runoff. While no individual RQ exceeds 1, the presence of multiple contaminants warrants further investigation into their combined effects on local biota and ecosystems since bioaccumulation and biomagnification can significantly increase the risk.

The detection of organic contaminants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pesticides, and nicotine, highlights persistent contamination risks in the Oconee River watershed. Variations in contaminant concentrations across sites underscore the influence of land-use practices, with forest areas showing elevated levels of contaminants compared to recreational and urban zones. The presence of pyrogenic PAHs, particularly those associated with incomplete combustion processes, suggests that human activities like industrial emissions, forest fires, and vehicular exhaust are primary contributors to water contamination. The network diagram shows that Malathion is a key contaminant with widespread correlations to other organic compounds, indicating its potential role in shaping the contamination landscape. Its connectivity highlights the potential for common contamination sources and pathways, particularly those related to agricultural and industrial activities. Understanding these connections can improve environmental monitoring efforts, support targeted remediation strategies, and ultimately help protect water resources from a wide array of contaminants. The clustering of PAHs suggests shared sources, reinforcing the need for targeted land-use management strategies. The analysis of contaminant networks and land-use relationships illustrates the complex interactions between pollutants and their potential sources.

The findings emphasize the need for improved regulatory policies and environmental management to mitigate the input of these contaminants into water systems. Monitoring and remediation strategies should focus on both the localized sources of pollution and the broader environmental impact of agricultural, industrial, and urban activities on water quality. While none of the contaminants exceeded the USEPA drinking water limits, the cumulative effects of these pollutants on the ecosystem and human health remain a concern. The study underscores the need for continuous monitoring, stringent regulation, and comprehensive watershed management practices to protect Georgia’s water resources and ensure long-term environmental and public health safety. The detected levels of contaminants, such as PAHs, pesticides, and nicotine pose potential risks to both environmental and human health. High concentrations of PAHs and pesticides can lead to adverse effects on aquatic life and potentially enter the human food chain through contaminated water. Regulatory measures should focus on reducing anthropogenic emissions and managing runoff to mitigate contamination. Continued monitoring and risk assessments are essential to protect water quality and public health, ensuring that contamination sources are effectively controlled and managed.

Future work will focus on increasing the number of data points, particularly at the confluence of the North Oconee and Middle Oconee Rivers, which merge to form the Oconee River. This additional sampling will help bridge existing data gaps and provide a more comprehensive understanding of contamination trends at this critical juncture. Moreover, further data collection along the Middle Oconee River will enhance our ability to evaluate how LU/LC influences water quality dynamics across the entire watershed. Expanding the spatial and temporal scope of sampling will allow for better seasonal trend analysis and long-term impact assessments. Strengthening regulatory frameworks and promoting sustainable land-use practices will be essential in mitigating contamination risks and ensuring the long-term health of the Oconee River watershed.

Materials and Methodology

Conducting a broad-spectrum assessment of the organic compound levels in the Georgia’s riverine system, we focused on five sampling sites across North Oconee River and Oconee River watershed (Table 4). All the sites were strategically selected due to its proximity to diverse LU/LC pattern spanning from urban, recreational and forest, making it susceptible to stormwater runoff. The study spanned eight sampling events from August 2023 to April 2024 (Table 4).

Sample collection and preservation

Water samples were collected using two distinct methods to ensure efficient and accurate sampling across all sites. At four locations FT, WTP, SC, and OR—a telescopic sampler equipped with a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) beaker attached to a stainless-steel rod was used, facilitating sample collection from a distance. However, at the RM site, a custom-designed PVC water collector was employed due to the significant height of the sampling platform above the river, which made it impractical for the telescopic sampler to reach the water surface. The use of two different sampling methods was necessary to accommodate site-specific conditions while maintaining uniformity in sample handling and storage, ensuring consistency and comparability across all collected samples. All samples were placed in 1 L amber glass bottles that had been pre-baked at 300 °C for 4 hours to ensure cleanliness. To measure key water parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), conductivity, total dissolved solids (TDS), turbidity, and salinity, a HANNA HI9829 probe (manufactured by Hannah Instruments in Smithfield, RI, USA) was used (Supplementary Table 1). Calibration was performed with a quick calibration solution prior to taking readings, which were then logged into a database. To maintain sample integrity, the collected water was stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator and processed within 24 hours of collection for further analyses.

Extraction of water samples

Water sample extraction involved the use of solid phase extraction (SPE) to extract compounds for subsequent quantitative analysis (modified from Duttagupta et al., 2020b; Duttagupta et al., 2024; and Basapuram et al., 2024)17,21,22. Before moving forward with the extraction procedure, samples were filtered with 0.45 µm Nylon-66 filter paper (47 mm dia.) followed by injection of 20 µL of 5 ng/mL naphthalene-d8 (>98%, Millipore Sigma®, St. Louis, MA, USA) as an internal standard. The samples were extracted through OASIS HLB (Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance) cartridges (6 cc Vac Cartridge, 150 mg Sorbent per Cartridge; Waters, Milford, MA), which were pre-conditioned with 5 mL of methanol. Cartridges were washed with 5 mL Type 1 ultrapure water three consecutive times. Extracts were eluted using 5 mL of dichloromethane (DCM) for nicotine and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and 5 mL of each acetone and hexane for pesticides30,32. The eluent was transferred into a clean test tube containing 5 g of sodium sulfate anhydrous to adsorb excess moisture in the extract. The supernatant was concentrated to 200 µL using controlled nitrogen purging. 20 µL of extracts were taken in a 2 mL GC amber vial and re-constituted up to 1 mL with 100% DCM for nicotine and PAHs and 100% hexane for pesticides. The samples were stored in −20 °C freezer until analysis.

Instrumental analysis

Quantitative targeted analysis was conducted using 8860 GC, 5977B MS Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (Agilent technologies ®) in in SIM mode with specific m/z for 22 analytes (SI: S1, S2 and S3)

Quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC)

The external calibration curves were generated using six standard solutions for each analyte, with concentrations of 0.05, 1, 10, 50, 100, and 500 ng/mL. An isotope-labeled internal standard, naphthalene-d8 (99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), was included in all solutions. The average recovery of the internal standard for each sample was mentioned in Supplementary Tables 1–6. The limit of detection (LOD) for each analyte was measured (Supplementary Table 1). The concentration of analytes in water sample was converted to ng/L. All used glassware were pre-cleaned and baked at 300 °C for 4 hours. Extracted water samples were stored in −20 °C until analysis. Ultra-purified type 1 water with resistivity of 18.2 MΩ.cm (ELGA® water purifying system, Woodridge, IL, USA) was considered as a laboratory blank.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were carried out in R and R Studio33. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the Euclidean distance based on the concentration of organic contaminant across different samples was performed using the phyloseq package34. Before conducting PCoA analysis, min-max scaling for each analyte was conducted. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using factoextra and Factominer packages35,36. A chord diagram for representing the distribution of different organic contaminants across different systems was made using the circlize package in R37. For the chord diagram, min-max scaling was done for each analyte, and then mean of each analyte was taken for each land use and land cover. Boxplots were made to analyze the differences in concentration of organic contaminant across different systems. The Kruskal-Wallis test for significance was used to determine whether the overall changes were significant, whereas the Wilcoxon test was used to find the pairwise significance. Co-occurrence network analysis was performed considering the concentration of organic contaminants across all the samples. The Pearson correlation coefficient among different organic contaminants was calculated using the cor() function in R. Based on pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient with correlation values > 0.70 were used for the construction of a co-occurrence network using Cytoscape 3.10.238.

Risk quotients (RQ) for contaminant exposure assessment

In this study, the risk quotient (RQ) was calculated to assess the potential ecological risk of some of the organic contaminants in freshwater systems. The RQ determined by dividing the measured environmental concentration of a contaminant by its established toxicity threshold, such as LC50 (lethal concentration for 50% of the population, following aquatic model) or the no observed effect concentration (NOEC)39. The following Eq. 1 was used to calculate RQ.

The measured average concentration in the water sample (ng/L) represents the exposure level of each contaminant at the sampling sites. The toxicity threshold (LC50 or NOEC) reflects the level at which no significant adverse effects are observed in aquatic organisms. An RQ value greater than 1 indicates that the exposure concentration exceeds the threshold for potential adverse effects, suggesting a high risk, while an RQ less than 1 suggests a low risk of harmful impact. This approach allows for a comparative assessment of risk across different sites and contaminants. Ten organic contaminants were selected for the risk quotient analysis based on available toxicity threshold data.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Ormerod, S. J., Dobson, M., Hildrew, A. G. & Townsend, C. Multiple stressors in freshwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 55, 1–4 (2010).

Assessment, Millennium Ecosystem. Ecosystems and human well-being: wetlands and water. World Resources Institute, 2005.

Dudgeon, D. et al. Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol. Rev. 81, 163–182 (2006).

Vörösmarty, C. J. et al. Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467, 555–561 (2010).

Carpenter, S. R., Stanley, E. H. & Vander Zanden, M. J. State of the world’s freshwater ecosystems: physical, chemical, and biological changes. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 36, 75–99 (2011).

Schwarzenbach, R. P. et al. The challenge of micropollutants in aquatic systems. Science 313, 1072–1077 (2006).

Kolpin, D. W. et al. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in US streams, 1999− 2000: A national reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 1202–1211 (2002).

Richardson, S. D., Plewa, M. J., Wagner, E. D., Schoeny, R. & DeMarini, D. M. Occurrence, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity of regulated and emerging disinfection by-products in drinking water: a review and roadmap for research. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 636, 178–242 (2007).

Duttagupta, S., Mukherjee, A., Bhattacharya, A. & Bhattacharya, J. Wide exposure of persistent organic pollutants (PoPs) in natural waters and sediments of the densely populated Western Bengal basin, India. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 137187 (2020).

Mukhopadhyay, A., Duttagupta, S. & Mukherjee, A. Emerging organic contaminants in global community drinking water sources and supply: A review of occurrence, processes and remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107560 (2022).

Lapworth, D. J., Baran, N., Stuart, M. E. & Ward, R. S. Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: a review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ. Pollut. 163, 287–303 (2012).

Richardson, S. D. & Ternes, T. A. Water analysis: emerging contaminants and current issues. Anal. Chem. 86, 2813–2848 (2014).

Metcalfe, C. D., Miao, X. S., Koenig, B. G. & Struger, J. Distribution of acidic and neutral drugs in surface waters near sewage treatment plants in the lower Great Lakes, Canada. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 2881–2889 (2003).

Hug, C., Ulrich, N., Schulze, T., Brack, W. & Krauss, M. Identification of novel micropollutants in wastewater by a combination of suspect and nontarget screening. Environ. Pollut. 184, 25–32 (2014).

Lapworth, D. J., Gopal, K., Rao, M. S. & MacDonald, A. M. Intensive groundwater exploitation in the Punjab: An evaluation of resource and quality trends, British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/14/068. 45pp (2014).

Meffe, R. & de Bustamante, I. Emerging organic contaminants in surface water and groundwater: a first overview of the situation in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 481, 280–295 (2014).

Li, S., Zhang, J., Jiang, P. & Zhang, L. Linking land use with riverine water quality: A multi-spatial scale analysis relating to various riparian strips. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1013318 (2022).

Paná, S. et al. The multiscale nexus among land use-land cover changes and water quality in the Suquía River Basin, a semi-arid region of Argentina. Sci. Rep. 14, 4670 (2024).

Rojas-Peña, J. I. et al. Assessing the Impacts of Land Use on Water Quality in the Acacias River Basin, Colombia. Water 16, 1903 (2024).

Mu, M. et al. Effects of land use on water quality at different spatial scales in the middle reaches of Huaihe River. J. Freshw. Ecol. 38, 2176373 (2023).

Yadav, S., Babel, M. S., Shrestha, S. & Deb, P. Land use impact on the water quality of large tropical river: Mun River Basin, Thailand. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 614 (2019).

Shukla, A. K. et al. Population growth, land use and land cover transformations, and water quality nexus in the Upper Ganga River basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 4745–4770 (2018).

Regier, P. J. et al. Water quality impacts of urban and non-urban arid-land runoff on the Rio Grande. Sci. Total Environ. 729, 138443 (2020).

Punja, V., Pathak, V., Shukla, S. P. & Tripathi, R. P. The impact of land use/land cover change on water quality in the Middle Ganga Region: A review. Top. Catal. 67, 1024–1037 (2024).

Basapuram, G., Duttagupta, S. & Dutta, A. Detection and screening of organic contaminants in a riverine system of Georgia using non-targeted analysis. Environments 11, 89 (2024).

Brook, G. A. & Luft, E. R. Channel pattern changes along the lower Oconee River, Georgia, 1805/7 to 1949. Phys. Geogr. 8, 191–209 (1987).

Fisher, D. S. et al. The relationship of land use practices to surface water quality in the Upper Oconee Watershed of Georgia. For. Ecol. Manage. 128, 39–48 (2000).

Conners, D.E., Eggert, S., Keyes, J. & Merrill, M. Community-based water quality monitoring by the Upper Oconee Watershed Network. In Proceedings of the 2001 Georgia Water Resources Conference, pp 706–709 (Georgia: Athens, 2001).

Severens, K. A. Portrait of Historic Athens and Clarke County, University of Georgia Press, Athens, ©2009 590–591 (1993).

Duttagupta, S. et al. Role of aquifer media in determining the fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the natural water and sediments along the lower Ganges River basin. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 55, 354–373 (2020).

Yunker, M. B. et al. Assessment of natural and anthropogenic hydrocarbon inputs using PAHs as tracers. The Fraser River basin and Strait of Georgia (1987–1997), 1–143 (Vancouver, B.C, Canada, 2000).

Duttagupta, S. et al. Influence of tobacco product wastes in a protected coastal reserve adjacent to urbanization. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 199, 115929 (2024).

RStudio Team. RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA Available at: http://www.rstudio.com (2015).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217 (2013).

Kassambara, A. & Mundt, F. Package ‘factoextra’. Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses. 76, 10-18637 (2017).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–8 (2008).

Gu, Z., Gu, L., Eils, R., Schlesner, M. & Brors, B. circlize Implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics 30, 2811–2812 (2014). Epub 2014 Jun 14. PMID: 24930139.

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Technical Overview of Ecological Risk Assessment: Risk Characterization. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-science-and-assessing-pesticide-risks/technical-overview-ecological-risk-assessment-risk. Accessed 18 Apr. 2025.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Environmental Management, under Award Number DE-EM0005228, granted to the University of Georgia Research Foundation. The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to Ms. Rose West, Nature Division Administrator at the Athens-Clarke County Leisure Services Department, for granting permission to collect samples from the North Oconee River at the Greenway near the Firefly Trail in Athens, as well as at Sandy Creek Beach Park near Lake Chapman. The authors also wish to express their gratitude to Mr. Tiger Brook for his assistance in obtaining water samples from the North Oconee River near the J.G. Beacham Water Treatment Plant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; G.B.: Formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing – review & editing; W.C.: Resources, writing – review & editing; A.D.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duttagupta, S., Basapuram, G., Cottrell, W. et al. Landuse and land cover shape organic contaminants distribution in the Oconee River watershed in Georgia. npj Emerg. Contam. 1, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00002-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00002-4