Abstract

The widespread use of antibiotics has resulted in their significant release into the environment, with the ocean becoming a major sink for antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). This review synthesizes global data on marine antibiotic contamination, covering sources, occurrence, behavior, and associated ecological and human health risks. Sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and tetracyclines dominate, with sulfamethoxazole most frequently detected (71.1% in seawater, 30.4% in sediment, 47.6% in biota). Peak levels reached 332,440 ng L−1 in seawater, 1515 ng g−1 in sediment, and 3341 ng g−1 in organisms, the highest in coastal China. Antibiotics with low direct toxicity may still drive ARG development. Coexisting contaminants (e.g., heavy metals, microplastics) may enhance impacts. Seafood-related health risks, especially in adolescents, merit attention. Monte Carlo analysis confirms ecological, antimicrobial resistance, and health risks remain significant under realistic exposure scenarios. These findings support global efforts in marine antibiotic pollution control and risk governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental pollution from emerging contaminants is becoming increasingly severe with the growth of the population and the development of industry and agriculture1. Among these contaminants, antibiotics are widely used in human and veterinary medicine to treat infectious diseases, as well as in livestock as growth promoters2. Among pharmaceutical active compounds (PhACs) monitored worldwide, antibiotics are the most frequently detected in both aquatic environments and wastewater. However, the widespread use of antibiotics, along with limited wastewater treatment rates, has led to their frequent detection and persistence across various environmental phases3. Antibiotics in aquatic environments can easily enter surface water, groundwater, and even seawater due to the mobility of water and their “pseudo-persistent” nature, ultimately contaminating drinking water sources4. The concentration of antibiotics in water typically falls within the range of ng L−1 to μg L−1 5, with sulfamethoxazole (SMX), trimethoprim (TMP), ciprofloxacin (CIP), erythromycin (ETM), and clarithromycin (CLM) being the main antibiotics detected. Despite their relatively low concentrations, they can pose considerable ecological and human health risks6. Bioaccumulation of antibiotics in aquatic organisms can induce toxicological effects, potentially disrupting physiological functions and ecosystem stability7. Through trophic transfer, accumulated antibiotics may ultimately enter the human body, contributing to adverse health outcomes8. Furthermore, the persistence of antibiotic residues in the environment exerts selective pressure on microbial communities, accelerating the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARBs) and the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). This process enhances pathogen resistance, undermines the efficacy of antimicrobial therapies, and complicates disease management9. The dissemination of ARBs and ARGs has emerged as a critical global public health concern, necessitating urgent intervention10.

The ocean represents a vast and intricate ecosystem, harboring billions of microbial populations within each liter of seawater11. It provides abundant food resources for organisms on the Earth and is pivotal in regulating the global climate and maintaining environmental health12. Antibiotics originating from industrial activities, livestock farming, aquaculture, pharmaceuticals, and domestic sewage are capable of both local and transboundary transport and ultimately accumulate in marine ecosystems, particularly in ecologically sensitive zones such as estuaries, coastal waters, and semi-enclosed bays6. Marine microbial communities are fundamental to the functioning of marine ecosystems, serving as the basis of the marine food web and contributing to global biogeochemical cycles, including those of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur13. Even at low concentrations, antibiotics can interfere with microbial metabolic activities and alter community structures, posing threats to ecological integrity4. The widespread microbial populations in the marine environment act as global reservoirs for ARBs and ARGs, facilitating their migration, dissemination, and propagation within biological communities13. However, current research on antibiotic contamination in the global marine environment remains limited in several important respects. Most existing studies are geographically restricted to specific regions or focused on individual environmental media, lacking a comprehensive global perspective. Moreover, systematic risk assessments are still rare, particularly with regard to ARGs. The processes governing the transport and transformation of antibiotics across different environmental compartments, the influence of unique marine conditions on these processes, and the interactions between antibiotics and coexisting contaminants, such as microplastics (MPs) and heavy metals, have not yet been comprehensively reviewed. These knowledge gaps constrain our ability to fully understand and address the ecological and human health risks posed by antibiotics in marine environments.

To address these challenges, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of antibiotics in the global marine environment, encompassing their sources, pollution levels, environmental behaviors, ecological effects, and associated health risks. Drawing on an extensive literature review, we systematically summarize the migration and transformation of antibiotics across various environmental compartments, with particular attention to the distinct characteristics of marine ecosystems. The ecological and human health impacts of antibiotic contamination are also examined, including the potential synergistic effects arising from co-occurring pollutants. Furthermore, we conduct an integrated environmental risk assessment that combines ecological risk, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) development, and human health risk, based on a quantitative analysis of global data. Based on the above summarization and analysis, future research directions and control measures to support the protection and management of marine ecosystems were discussed. Overall, the review is structured into six sections: (1) emission sources; (2) occurrence characteristics; (3) environmental behavior; (4) environmental effects; (5) risk assessment; and (6) conclusions and implications.

Results

Sources

Antibiotics used by humans and animals are not completely metabolized, and most are released into the environment in the form of excreta14. Marine environments receive antibiotic contaminants from various sources, including activities across different industries. The emergence and rapid expansion of these pollution sources pose potential threats to marine ecosystems. Therefore, identifying the primary sources of marine antibiotics is of significant importance for reducing antibiotic contamination at its origin. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the sources of antibiotics in the marine environment can be categorized into direct and indirect sources.

The direct sources of antibiotics in the marine environment primarily include atmospheric deposition, discharge from mariculture, and offshore sewage. Atmospheric activity over the ocean is significant15. Thus, atmospheric deposition can serve as a potential source of antibiotics in the marine environment16. Although atmospheric antibiotic concentrations are relatively low, resulting in a limited direct contribution of atmospheric deposition to marine antibiotic loads17, this process remains an important pathway for the long-range transport and global dissemination of antibiotics and their associated ARGs9.

The increasing global demand for aquatic products has driven the expansion of mariculture, making it a significant sector within the aquaculture industry18. To mitigate disease outbreaks and enhance growth rates, antibiotics are frequently incorporated into feed, resulting in their direct release into the surrounding marine environment19. Mariculture farms, predominantly situated in coastal regions, introduce antibiotics into the marine environment primarily through the excreta of farmed animals, following their ingestion via medicated feed. This process represents a significant pathway for antibiotic contamination in coastal waters20. Coastal regions, characterized by high population densities and ecologically sensitive marine ecosystems, are particularly susceptible to the adverse effects of antibiotic contamination6,21. Moreover, nearshore waters are significantly influenced by human activities, with antibiotics from various sources being frequently released directly into these areas along with sewage, thereby intensifying antibiotic contamination22.

Indirect sources of antibiotics are their discharge into marine environments through various land-based activities. These sources include domestic sewage, hospital effluent, industrial discharges, and wastewater from livestock and aquaculture22. Domestic sewage originates from both urban and rural areas23. In urban areas, sewage is typically directed to wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), yet the treatment processes often fail to completely remove antibiotics, resulting in their persistence in the effluent24. In contrast, wastewater treatment infrastructure in rural areas is limited or even absent, and untreated sewage containing antibiotics is often discharged directly into water bodies25.

Hospital effluent is another significant contributor, containing high concentrations of antibiotics due to pharmaceutical waste, drug production, and excreta from patients26. Industrial activities, especially those within the pharmaceutical sector, also discharge wastewater contaminated with antibiotics27. The highest residues of antibiotics (mg L−1) have been detected in wastewater from pharmaceutical manufacturing. In addition, the removal of these compounds remains incomplete in many pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plants (PWWTPs). Limitations in pharmaceutical and industrial wastewater treatment processes, combined with persistently high emissions, lead to the continuous discharge of residual pollutants into the surrounding environment28.

In agriculture, the primary pathways through which antibiotics enter the environment are livestock farms and aquaculture systems29. Livestock production stands out as a significant contributor, with up to 90% of administered veterinary antibiotics being excreted by animals30. Many farms, especially small-scale ones, often lack adequate wastewater treatment facilities, leading to the release of untreated or inadequately treated wastewater into nearby water bodies31. Moreover, animal waste is frequently utilized as fertilizer, inadvertently introducing antibiotics into the soil32.

Overall, the antibiotics discharged into the environment predominantly accumulated in soil and water33. The reuse of wastewater and sludge from various sources can contribute to the accumulation of antibiotics in the soil34. In soil, these compounds may be washed into marine waters via rainfall, infiltration into groundwater systems, and other processes22. In water, antibiotics are transported both locally and over long distances through surface runoff and groundwater circulation, eventually reaching the marine environment. Due to its vast volume, complex ecosystems, extensive pollutant inputs, and role as the ultimate sink in the global water cycle, the ocean has accumulated antibiotic contamination from land-based sources over the long term, ultimately serving as a significant reservoir for both antibiotics and ARGs.

Occurrence

Status of antibiotic contamination in various environmental phases

Statistics on the global marine pollution by antibiotics over the last two decades are presented in Supplementary Tables 6–9, alongside the detection rates of individual antibiotics are shown in Fig. 2. Monitoring antibiotics in the atmosphere remains challenging due to their low concentrations and detection difficulty, which is why studies typically focus on environmental phases such as seawater, marine sediments, and marine biota. However, some studies have reported the presence of ARBs in the atmosphere, highlighting the potential health risks due to the high mobility of airborne contaminants and the possibility of direct human inhalation35,36.

As detailed in Fig. 2a, seawater is the most extensively studied marine environment, with 72 antibiotics detected. Concentrations ranged from non-detectable (ND) to 332,440 ng L−1, with most falling in the level of ng L−1, although some areas showed levels reaching μg L−1 37,38,39. The most frequently detected antibiotics were SAs, FQs, and MAs, with SMX having the highest detection rate (71.1%), followed by TMP at 65.8%, CLM at 44.8%, and both ofloxacin (OFX) (34.2%) and norfloxacin (NFX) at 31.6%. SMX, a widely used antibiotic in medicine and livestock production, is often used in combination with TMP40. The highest concentration of TMP observed was 332,440 ng L−1, recorded near the mariculture zone of Laizhou Bay in the Bohai Sea. In this area, the concentrations of other antibiotics, such as sulfamethazine (SMZ), sulfadimethoxine (SDM), enrofloxacin (EFX), doxycycline (DC), and oxytetracycline (OTC), also reached μg L−1 levels. These elevated concentrations largely result from the discharge of mariculture wastewater37. Remote regions like the Antarctic have also been affected by antibiotic contamination, with CIP detected at concentrations ranging from 4 ng L−1 to 218 ng L−1 41, highlighting the long-range transport and environmental persistence of antibiotics in seawater.

Antibiotics released into the marine environments can adsorb onto suspended solids and subsequently deposit in marine sediments42. A total of 56 antibiotics were identified in sediments. The concentrations range from ND to 1515 ng g−1, with most at the ng g−1 level. As shown in Fig. 2b, SAs, FQs, and TCs were the predominant antibiotic classes detected in sediments. Among the specific antibiotics identified, TMP (39.1%), tetracycline (TC) (39.1%), SMZ (34.8%), SMX (30.4%), EFX (30.4%), and CIP (30.4%) were the most frequently observed. The highest concentration observed was for OTC, with a value of 1515 ng g−1 in sediments from the Southern Baltic Sea, an area influenced by agricultural runoff and tourism43. Even sediments in the Arctic region have shown substantial contamination, with CIP concentrations reaching 685 ng g−1, likely due to the extensive use of CIP in Norway44. The proximity to pollution sources plays a crucial role in determining antibiotic levels in sediments, with higher concentrations commonly observed in areas near densely populated regions, mariculture activities, and WWTPs42,43,45. Besides, the physicochemical properties of antibiotics, particularly their hydrophobicity, influence their interaction with sediments. Antibiotics with higher hydrophobicity (log KOW > 2) tend to exhibit a stronger tendency to adsorb to sediments46.

Marine organisms are capable of adsorbing and accumulating antibiotics, which may subsequently enter the food chain and pose potential health risks to humans47. A comprehensive understanding of antibiotic bioconcentration in marine biota is fundamental for evaluating these risks. Current research has primarily focused on Asian regions, where 45 different antibiotics have been identified in marine organisms, with concentrations varying from ND to 3341 ng g−1. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, SMX (47.6%), TMP (38.1%), sulfadiazine (SDZ) (33.3%), SMZ (28.6%), EFX (28.6%), and CIP (28.6%) were the most frequently detected compounds. FQs exhibited higher concentrations than other antibiotic classes, likely due to their strong bioaccumulation potential in marine organisms48. Among the FQs detected, oxolinic acid (OA) had the highest concentration, reaching 3341 ng g−1 at a mariculture farm in South Korea, where several other antibiotics also reached μg g−1 levels49. Antibiotic accumulation in organisms appears to be tissue-specific. Specifically, FQs predominantly accumulate in muscle, while MAs tend to concentrate in the liver47.

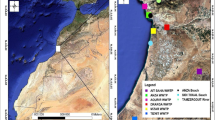

Comparison of antibiotic contamination among countries

Based on the highest detected concentration, the antibiotic contamination in different marine areas across countries was compared (Fig. 3), with specific references in Supplementary Table 6. In global seawater, China (0.06–322,440 ng L−1, mean 2247 ng L−1)37,39,42,45,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 and Costa Rica (2–7425 ng L−1, mean 1281 ng L−1)61 showed the highest antibiotic concentrations. The East China Sea had the largest variety of antibiotics detected, with 43 types, including SAs, FQs, MAs, TCs, and βLs42. In China, the highest antibiotic concentration was found in the Laizhou Bay of the Bohai Sea, where TMP reached 322,440 ng L−1 and SDM reached 42,550 ng L−1 in the seawater, generally higher than other marine areas by 2–5 orders of magnitude37. This is likely due to the proximity of mariculture areas. Similarly, a high level of OTC (15,163 ng L−1) was also detected in the South China Sea39. Costa Rica exhibited high levels of DC (5509 ng L-1) and oxacillin (OXA) (7425 ng L−1), with OXA being detected only in this region, likely due to the presence of sources including WWTPs61. High concentrations of antibiotics were also detected in South Korea (0.196–1626 ng L−1, mean 231 ng L−1)38,46, South Africa (9.5–1167 ng L−1, mean 278 ng L−1)62,63, Fiji (6.3–760 ng L−1, mean 244 ng L−1)64, and Ireland (870 ng L−1 for TMP)65. The lowest antibiotic concentrations were found in Singapore (0.24–6.26 ng L−1, mean 2.98 ng L−1), where mangrove ecosystems, a unique transitional coastal ecosystem, are located66. Despite the low concentration, antibiotics might accelerate mangrove loss as they are vulnerable to stressors like chemical contamination (including antibiotics).

In marine sediments, China (0.02–1260 ng g−1, mean 23.3 ng g−1)37,39,42,45,50,53,57,58,60,67, Iran (2.28–119 ng g−1, mean 27.9 ng g−1)68, Norway (only CIP was detected with a concentration of 685 ng g−1)44, and Poland (1.33–1515 ng g−1, mean 191 ng g−1)43,69,70,71,72 exhibited high levels of antibiotic contamination. The highest concentrations of antibiotics were observed in the adjacent marine embayment of Jin River in southeastern China, with SMX ranging from 38.3 ng g−1 to 1260 ng g−1, due to the impacts of mariculture wastewater45. In Iran, elevated NFX levels (119 ng g−1) in the Persian Gulf are linked to runoff discharges from WWTPs68. In Arctic Norway, CIP was detected in sediments, with its persistence supported by low temperatures and slow degradation rates, posing long-term risks to the Arctic ecosystem44. In Poland, the major antibiotic contaminants are SMX (276 ng g−1), OTC (1515 ng g−1), and TC (449 ng g−1) in the southern Baltic Sea43,71 and OTC (625 ng g−1) in the Gulf of Gdańsk72.

For marine biota, South Africa showed the highest mean concentrations (272–689 ng g−1, mean 481 ng g−1), although SMX was the only antibiotic detected62,73. Interestingly, SMX was also the sole antibiotic found in South African seawater62, underscoring the cross-phase migration of antibiotics from seawater to biota. Significant antibiotic contamination in marine biota was also observed in other countries, including China (0.01–336 ng g−1, mean 25.2 ng g−1)37,47,50,53,57,59,74,75, the United States (US) (0.1–430 ng g−1, mean 92 ng g−1)76,77, and South Korea (0.174–3341 ng g−1, mean 289 ng g−1)46,49. Notably, high levels of NFX (256 ng g−1) and spectinomycin (STM) (366 ng g−1) were found in the Pearl River Delta of China50, and EFX reached 270 ng g−1 in the Laizhou Bay of the Bohai Sea47. The SMZ detected on the California coast of the US reached 430 ng g−1, 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than other antibiotics detected in the US77. South Korea reported the highest concentration in biota, with OA at 3341 ng g−1 in Korean bullheads, far exceeding the maximum residue limit of Korean veterinary drugs (100 ng g−1)49. A concerning observation was the detection of ronidazole (RON) (ND-2.26 ng g−1) in Spain, despite its ban in 1993 due to its genotoxic and carcinogenic properties78, which underscores the persistence of this antibiotic in marine sediments.

China’s marine environments have been the subject of extensive research on antibiotic contamination, with increasing numbers of antibiotics being detected across the country’s four major marine areas (Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea). As one of the largest producers and consumers of antibiotics79, China exhibited higher detection frequencies and concentrations of antibiotics in its marine environments compared to other countries, underscoring the severe antibiotic contamination in these marine areas. Although considerable progress has been made in assessing antibiotic contamination and associated risks in many parts of the world, significant research gaps remain in regions such as South America, Africa, and polar areas. These regions are under-represented, possibly due to limited research funding and infrastructure, less frequent data publication, weaker regulatory frameworks, and logistical challenges associated with sampling in remote or harsh environments. The scarcity of monitoring data from these regions limits our understanding of the global distribution and ecological impacts of antibiotics. Environmental conditions, antibiotic usage patterns, and ecosystem sensitivities may differ substantially in these areas, potentially leading to unique risks that are currently overlooked. Therefore, future studies should conduct comprehensive monitoring and risk assessment in these understudied regions to achieve a more complete and accurate global evaluation.

Due to the lack of continuous and systematic long-term monitoring data, this study is limited in its ability to analyze temporal trends in antibiotic concentrations. Future research should aim to collect and integrate temporally continuous monitoring data, particularly through comparative analyses of the same marine regions across different years or seasons, to better characterize the temporal dynamics of antibiotic contamination and identify potential driving factors. Moreover, data for certain environmental compartments, such as deep-sea sediments and marine biota, remain limited. These compartments should be prioritized in future targeted monitoring efforts. The absence of such data has contributed to a geographic bias in the spatial distribution of antibiotic concentrations in marine biota, which are primarily concentrated in Asian seas. This reflects a broader geographic imbalance in global marine monitoring. Similar biases are also evident in seawater and marine sediment data, with some regions lacking any available information. Such geographic gaps may affect the representativeness of the results at the global scale. Nonetheless, the coastal waters of Asia, characterized by the highest levels of antibiotic production, use, and environmental contamination79,80, serve as a critical reference for high-risk marine areas. To enhance the global relevance and comparability of findings, future research should advance integrated, multimedia monitoring across diverse marine regions.

Environmental behavior

Cross-phase migration and transformation of antibiotics

In marine ecosystems, antibiotics undergo migration and transformation across multiple environmental phases, including the atmosphere, seawater, sediments, and biota (Fig. 4). This cross-phase behavior is governed by a range of physicochemical and biological factors, such as temperature, salinity, and pH value. These factors collectively modulate the partitioning, degradation, and bioavailability of antibiotics, thereby shaping their persistence and potential ecological consequences.

Antibiotics present in seawater can exist in particulate form, enabling their diffusion into the marine atmosphere, where they may contribute to aerosol formation and subsequently return to the ocean through atmospheric deposition16. This deposition occurs via two primary mechanisms: dry deposition, in which airborne contaminants settle onto surfaces in the absence of precipitation, and wet deposition, where pollutants are scavenged by atmospheric precipitation (e.g., rain and snow) and deposited onto the surface81. These processes facilitate the exchange of antibiotics between the atmosphere and seawater.

Antibiotics in seawater can migrate to marine sediments through diffusion and sedimentation processes82. Meanwhile, antibiotics retained in sediments can be resuspended into seawater under environmental disturbances, such as changes in hydrodynamic conditions, temperature, and pH83. Although antibiotic concentrations in seawater often vary over time, they tend to remain relatively stable in sediments, which serve as a major reservoir in the marine environment78. The extent of antibiotic retention in sediments is strongly influenced by molecular properties, with FQs, for instance, exhibiting a high adsorption affinity due to their capacity to chelate metal cations and associate with particulate matter4.

The migration of antibiotics between seawater and marine biota is governed by processes of absorption, bioaccumulation, and metabolic transformation84. Marine organisms, including plankton, nekton, and benthic species, support a variety of microbial communities and enzymatic systems capable of breaking down antibiotics85. Antibiotics that enter the organism, if rapidly metabolized into various metabolites that reduce their toxicity, will exhibit a biodilution effect86. However, antibiotics are not always completely degraded, resulting in a potential biomagnification effect with higher concentrations in organisms of higher trophic levels47. Additionally, benthic organisms can absorb antibiotics from sediments, promoting the transfer of these compounds from sediments to living organisms86.

In regions with high antibiotic concentrations and dense microbial populations, the biodilution effect is likely to prevail, as microbes are capable of efficiently degrading large quantities of antibiotics87. Antibiotics that resist degradation tend to accumulate within organisms over time, resulting in a predominance of biomagnification53. The extent of these effects depends on the particular antibiotic type and the physiological and ecological traits of the organisms involved, including factors such as lifestyle, age, body size, and osmoregulation53,73. Generally, SAs are more prone to biomagnification, while FQs and MAs are often subject to dilution86. The trophic magnification factor (TMF) is a critical metric used to quantify these phenomena, with TMF values greater than 1 indicating biomagnification and values less than 1 indicating biodilution88.

Plastics are capable of adsorbing antibiotics, fostering microbial colonization, and providing both habitats and nutrients for algae89. Therefore, the prevalence of plastic in the ocean may contribute to the increased accumulation of antibiotics in algae. Given that algae are primary producers, the presence of antibiotics in these organisms could result in a wider dispersal of these compounds across the marine ecosystem90. Nevertheless, the effects of plastics and other pollutants on the behavior of antibiotics in marine environments remain an area that requires further research.

In general, antibiotics experience intricate processes of migration and transformation across various marine environmental phases, eventually accumulating in sediments91. As a result, marine sediments may serve as potential reservoirs for antibiotics92, whereas seawater functions as a medium that facilitates the movement and transformation of these compounds within the marine ecosystem.

The adsorption and degradation of antibiotics

Adsorption and degradation are key processes determining the migration and transformation of antibiotics in the marine environment93. Adsorption can be either physical or chemical22. Physical adsorption takes place when intermolecular forces create adsorption sites on the surfaces of particulate matter, whereas chemical adsorption involves the formation of chemical bonds between antibiotic molecules and environmental molecules93. For example, antibiotic molecules can form complexes or chelate with organic matter, metal ions, or other substances present on the sediment surface94. The efficiency of adsorption depends on the specific type of antibiotic. FQs and TCs tend to have a stronger affinity for adsorption, whereas SAs and MAs are less likely to adsorb95.

Degradation can reduce the concentration and toxicity of antibiotics. It includes hydrolysis, photolysis, and biodegradation50. Hydrolysis often occurs alongside other degradation processes, increasing the polarity and hydrophilicity of antibiotics, thus promoting further biodegradation20. Hydrolysis occurs when water molecules interact with specific hydrolyzable groups in antibiotic molecules, leading to bond cleavage and the formation of new products96. Hydrolysis can be either biological or chemical. Chemical hydrolysis forms new compounds by replacing functional groups with H+ or OH− ions in water97. In contrast, biological hydrolysis is the breakdown of complex organic compounds by water, catalyzed by biological catalysts, such as enzymes97. Antibiotics like TCs, MAs, and βLs are highly susceptible to hydrolysis98,99, while SAs exhibit low hydrolytic activity, and FQs resist hydrolysis93.

Photolysis is driven by light, and it breaks down antibiotics by altering their chemical structure and reducing their activity100. Photolysis usually requires specific light sources and environmental conditions, such as ultraviolet (UV) light or the presence of photocatalysts101. In the ocean, photolysis mainly happens in surface waters where UV light is strongest, but it rarely occurs in deeper waters or sediments102. The susceptibility of antibiotics to photolysis depends on their structure. For example, TCs are highly susceptible to photolysis, while FQs are much less affected by this process95.

Biodegradation is more common than hydrolysis or photolysis, occurring when microbial metabolism triggers chemical reactions that deactivate antibiotics103. Antibiotics containing short-chain or unsaturated aliphatic groups are generally more biodegradable than those with long-chain or aromatic structures104. FQs are more resistant to biodegradation compared to other antibiotics due to their fluorine atoms and aromatic structure105.

In short, adsorption and degradation play key roles in determining the fate of antibiotics in the marine environment93. Adsorption helps retain antibiotics on particulate matter, while degradation is crucial for lowering antibiotic concentrations and reducing their potential toxicity20. These processes collectively affect the migration, transformation, and ecological impact of antibiotics in marine ecosystems.

Unique characteristics of the marine environment and their impacts

The marine environment differs significantly from freshwater systems, due to its unique physicochemical and ecological properties, such as salinity, temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO) levels, oxidation–reduction potential (ORP), electrical conductivity, biodiversity, and hydrodynamic conditions106. These interconnected factors collectively influence the transport, transformation, and ultimate fate of antibiotics in marine ecosystems, shaping their bioavailability, degradation pathways, and persistence.

High salinity in marine environments can lead to osmotic stress in microbial cells, resulting in water loss, suppressed enzyme activity, and hindered antibiotic degradation107,108. High salinity may also promote the adsorption of cations onto sediment surfaces, thereby reducing the binding sites available for antibiotics109. For instance, the adsorption of TC by marine sediments has been reported to decrease with rising pH and salinity, potentially altering its partitioning between seawater and sediments110. However, some studies have also reported a positive correlation between salinity and the adsorption of SMX by marine sediments111, indicating that antibiotic structure influences its interaction with salinity and sediments.

Salinity also impacts the solubility of antibiotics in seawater112. Increased salinity can lower solubility, leading to the aggregation of antibiotics into larger particles, which are less accessible for microbial degradation113. Salinity may also affect the hydrolysis rate of antibiotics20, though additional research is needed to fully understand this relationship. MPs in marine environments can adsorb antibiotics and ARGs, but studies have shown that the concentration of antibiotics and ARGs on MPs declines as salinity increases114. This phenomenon may be attributed to the inhibitory effect of high salinity on hydrogen bond formation115.

Additionally, salinity can influence pH levels. Increased concentrations of salt ions may lead to a decrease in pH, thereby accelerating ocean acidification116,117. Such acidification may impede antibiotic degradation by decreasing their bioavailability and modifying the composition of dissolved organic matter (DOM)118,119. It has been reported that the uptake and bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals in aquatic organisms increases with rising pH levels47,120. Therefore, a decline in pH could limit the transfer of antibiotics from seawater or sediments to aquatic organisms.

Marine ecosystems typically exhibit higher biodiversity than terrestrial freshwater systems121. High biomass levels consume DO, while elevated salinity reduces oxygen solubility, collectively leading to lower DO concentrations in seawater compared to terrestrial freshwater systems122. Numerous studies have shown that reduced DO levels could hinder the degradation of antibiotics52,123,124. ORP is a key parameter influencing the redox reactions of antibiotics125, with high ORP generally promoting antibiotic degradation126,127. A decrease in DO is generally accompanied by a reduction in ORP128. In deeper seawaters and sediments, reduced DO and ORP may facilitate anaerobic biodegradation, but it occurs at a much slower rate compared to aerobic biodegradation, leading to the accumulation of antibiotics in these environments129.

The temperature and light exposure in seawaters exhibit considerable variation with depth. Surface seawaters are typically warmer and receive more light than deeper seawaters112. Although increased precipitation during summer enhances seawater flow, facilitating the dilution and dispersal of antibiotics52, antibiotic concentrations were generally higher in winter than in summer due to the accelerated degradation driven by stronger sunlight and higher temperatures in summer33. Thus, it can be inferred that the lower temperatures and reduced light availability at greater depths may hinder the biodegradation of antibiotics, potentially contributing to their accumulation in deeper seawaters and sediments. These environmental gradients may lead to depth-dependent variations in the behavior of antibiotics with notable differences in concentration among surface waters, deeper waters, and sediments112.

Overall, the unique marine environments shape distinct antibiotic dynamics. However, the complex interaction among various environmental factors makes it difficult to establish direct relationships between antibiotic behavior and any single factor. Therefore, systematic research is needed to comprehensively understand the impact of marine-specific environmental conditions on antibiotic behavior.

Ecological and human health effects

Adverse effects on marine organisms

Antibiotics released into the marine environment can be toxic to aquatic organisms, interfering with essential biological functions such as algal growth, photosynthesis, and reproduction in species like Daphnia magna28. These lower trophic level organisms are essential for primary production and nutrient cycling, contributing to the overall stability of the marine ecosystem121. For instance, antibiotics such as levofloxacin (LVX) and NFX could significantly suppress the growth and enzymatic activity of microalgae130. The introduction of exogenous antibiotics and ARGs in regions like the Bohai Sea could alter the bacterial community composition, altering microbial-mediated sedimentary processes91. Antibiotic contamination combined with ocean acidification could lead to neurological disorders in marine organisms such as scallops131.

Antibiotics can also cause genetic damage and interfere with larval development. For instance, antibiotics like SMX and CLM could compromise the immune system of zebrafish (Danio rerio), increasing their susceptibility to viral infections132. Antibiotics such as SMZ, EFX, DC, and FF could impair lipid metabolism in zebrafish larvae133. Ocean acidification and the naturally high salinity of marine environments may enhance the toxicity of antibiotics to marine organisms134. For example, antibiotic contamination and ocean acidification collectively could induce apoptosis of scallop (Argopecten irradians) cells135.

Marine organisms can absorb antibiotics both directly and indirectly, such as through the consumption of phytoplankton or small organisms that have assimilated these compounds136. It has been reported that the bioaccumulation factors (BAFs) of NFX, dehydrated erythromycin (ETM-H2O), and roxithromycin (RTM) could exceed 5000 L kg−1 for certain offshore fishes, indicating significant bioaccumulation potential137. Trophic amplification of enoxacin (ENX) has also been observed in coastal coral reef fish food webs, with a TMF of 2.75137. These indicate that antibiotics can bioaccumulate through marine food chains and webs, potentially endangering higher trophic level organisms.

Marine ecosystems host a diversity of microorganisms, and the presence of antibiotics can drive the emergence of ARBs and the dissemination of ARGs. This poses a global public health challenge by complicating the treatment of previously manageable infections and increasing healthcare costs138. The increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance raises concerns that the development of new antibiotics may fail to keep up, potentially undermining infection treatment efforts139. It has been reported that the ARGs of βLs, TCs, and multiple other antibiotics are widespread in marine environments, especially in mariculture areas, with approximately 20% of them posing emerging risks140. Beyond antibiotic discharge, human activities can also affect the expression of ARGs by altering nitrogen, phosphorus levels, and seawater temperature13, highlighting the role of anthropogenic factors in shaping ARG dynamics in marine environments.

Negative impacts on human health

Antibiotics in marine ecosystems pose significant health risks to humans, primarily through two pathways: dietary exposure and the dissemination of ARBs and ARGs. The consumption of seafood has been identified as a critical pathway for human exposure to antibiotic residues141. It has been reported that some antibiotics can transfer and bioaccumulate through the food chain, increasing the human exposure risk when consuming contaminated seafood50. It was estimated that about 4.02 kg of antibiotics are transferred annually via marine fishery catches for human consumption142. It was found that the HQ in Hailing Bay could reach 3.1% due to exposure to ETM through shrimp consumption (considerable health risk: 1% < HQ ≤ 5%)83.

The human microbiome consists of a diverse array of beneficial microorganisms and plays a vital role in sustaining human health143. Exposure to antibiotics via seafood, desalinated seawater, or marine aerosol may disturb the human microbiome, leading to potential digestive and immune system issues143,144. Microbiota imbalances can promote the overgrowth of harmful bacteria and opportunistic pathogens, leading to a range of diseases145. The presence of ARBs and ARGs can worsen these problems by making infections harder to treat146. The emergence of “superbugs” has become a major global public health challenge147. It was estimated that 4.95 (3.62–6.57) million deaths in 2019 were associated with bacterial AMR148.

Synergistic environmental risks of antibiotics and coexisting contaminants

In marine environments, antibiotics frequently coexist with other contaminants, including heavy metals149 and plastics114, as well as phage viruses150. These coexisting contaminants can interact through complex physicochemical and biological processes, potentially leading to synergistic effects that exacerbate both ecological disturbances and human health risks151. Heavy metals, for instance, can promote the spread of antibiotic resistance by co-selecting ARGs, thereby increasing the risk of multidrug-ARBs149,152. This has been demonstrated by the positive correlation between the abundance of ARGs and metals revealed in previous studies153,154,155.

MPs are now widely distributed in global marine environments156. They can selectively adsorb and enrich antibiotics, ARGs, and microorganisms, acting as carriers for these contaminants114. It has been demonstrated that MPs can increase the accumulation of antibiotics in marine organisms and alter microbial community structures157. The coexistence of MPs and antibiotics has been found to promote the growth of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), and cause severe infections in humans158. Additionally, MPs can exacerbate the toxic effects of antibiotics by inducing oxidative stress, resulting in cellular damage in marine organisms115.

Phages are among the most abundant microorganisms in marine environments159. They can regulate bacterial populations and influence microbial community dynamics160. Phages can carry certain ARGs, facilitate the horizontal transfer of these ARGs between bacteria through transduction161, and accelerate the spread of plasmid-encoded antibiotic resistance162, thereby promoting the spread of resistance. Phages can also create selective pressure on bacteria in combination with antibiotic contamination, leading to a more rapid emergence and propagation of resistant strains150.

In summary, the combined effects of antibiotics and other contaminants create a complex pollution issue in marine ecosystems. The interactions between these pollutants require further investigation, as their collective impact may pose a greater threat to both ecological systems and human health than individual contaminants alone. Understanding and addressing these synergistic effects is crucial for protecting marine biodiversity and ensuring public health.

Risk assessment

Ecological risk

The ecological risk of antibiotics in seawater and marine sediments was assessed by examining three trophic levels of organisms (algae, invertebrates, and fish). The RQ values of antibiotics for these trophic levels in seawater are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The ecological risk posed to marine ecosystems is influenced by various factors, including their toxicity, physicochemical properties, and persistence134. Based on existing data, antibiotics tend to be more toxic to organisms at lower trophic levels, such as algae, than to those at higher trophic levels, like fish2. As a result, algae face significantly higher ecological risks from antibiotic contamination compared to invertebrates or fish. However, uncertainty remains due to potential long-term effects and possible biomagnification through food chains and webs, which may lead to higher levels of exposure and increased toxicity over time for higher-level predators.

In seawater, 41.7% of antibiotics posed a moderate or higher risk to algae, with 29.2% classified as high risk. SMX, SDM, TMP, OFX, EFX, NFX, CIP, OA, RTM, ETM-H2O, CLM, ETM, spiramycin (SPM), CTC, OTC, TC, DC, amoxicillin (AMX), penicillin G (PCG), ampicillin (AMP), and salinomycin (SLM) were of particular concern, with CIP in False Bay, Cape Town (RQWater-Algae = 92.4) presenting the highest risk. For invertebrates, 23.6% of antibiotics posed a moderate or higher risk, with 6.94% (SMX, TMP, NFX, DC, and SLM) identified as high risk. The antibiotic with the highest risk to invertebrates was DC in the coastal waters of Costa Rica (RQWater-Invertebrate = 11.1). Similarly, for fish, 15.3% of antibiotics posed a moderate or higher risk, and 5.56% posed a high risk, with NFX in the coastal waters of Costa Rica again showing the highest risk (RQWater-Fish = 15.1). The Costa Rican coastal waters demonstrated a particularly severe ecological risk, where multiple antibiotics simultaneously posed high risks to algae, invertebrates, and fish, underscoring the urgent need for targeted management in this region61. In marine sediments, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the ecological risk was notably lower than in seawater. For algae, 9.62% of antibiotics posed moderate or high risk, with 5.77% categorized as high risk, including SMX, OTC, and OA. The highest-risk regions for sediment pollution include the Southern Baltic Sea in Poland (OA and OTC posed high risk)43,71 and the Jin River estuary in China (SMX posed high risk)45, where stricter antibiotic controls are necessary. For invertebrates, 3.85% of antibiotics posed a moderate risk, but no antibiotics presented a high risk. Fish were exposed to minimal risks from sediment-bound antibiotics, with only NFX and chlortetracycline (CTC) posing low risks.

The mixed ecological risk assessment, illustrated in Fig. 5a, b, was conducted to evaluate the synergistic pollution caused by multiple antibiotics coexisting in the same marine environment. The mixed risk quotient (RQ) values (MRQMEC/PNEC and MRQSTU) in seawaters ranged from 0.02 to over 178, indicating that the majority of marine areas (81.6%) faced high mixed ecological risk, particularly in 12 countries and regions, including China, Korea, Russia, and the Antarctic. In marine sediments, the mixed ecological risks were considerably lower, with MRQMEC/PNEC and MRQSTU values ranging from 0 to 3.49. Approximately 39.1% of marine areas faced moderate or higher risk, notably in the Jin River estuary45 and the Southern Baltic Sea43,71.

While this assessment offers valuable insights into the ecological risks of marine antibiotic contamination, it does not fully consider the potential long-term cumulative effects of continuous antibiotic exposure163. The potential amplification of ecological impacts due to the coexistence of other contaminants, such as MPs and heavy metals164, was also not included. Future research should focus on chronic exposure and the interactive effects of multiple contaminants. This is essential for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term ecological risks of antibiotic contamination.

Risk of developing AMR

Globally, the concentrations of most antibiotics in seawater remain below the AMR-PNEC values. However, in some regions, concentrations of certain antibiotics surpassed the AMR-PNEC threshold, indicating a potential risk for AMR development (Fig. 5c). Twelve antibiotics, including SMX, TMP, EFX, CIP, azithromycin (ATM), TYL, OTC, TC, DC, cefalexin (CEL), OXA, and metronidazole (MET), posed a risk for AMR development across 13 marine areas spanning 10 countries or regions, such as China, South Korea, Poland, Spain, South Africa, and Antarctica. Notably, the risk of AMR development due to TMP in Laizhou Bay of the Bohai Sea in China was the most severe, followed by the risk associated with OTC in the Marine aquaculture farms surrounding Hailing Island and in the South China Sea.

Importantly, certain antibiotics with relatively low ecological risk, such as ATM, CEL, and MET, still show potential to promote AMR. This highlights that even antibiotics posing minimal threats to marine ecosystems from a toxicity perspective may contribute to the rise of AMR, underscoring the need for comprehensive risk assessments for antibiotic contamination that integrate both ecological and AMR-related risks.

Traditional ecological risk assessments that rely on RQ methods do not fully address the risks due to the development of AMR165. However, the emergence of AMR is a major risk associated with antibiotic contamination166. It has been reported that many AMR genes can persist even in low antibiotic concentrations, indicating that even sub-lethal doses of antibiotics in marine environments may still contribute to the development of resistance167. Therefore, it is essential to integrate various assessment approaches to better understand and identify high-risk antibiotics, enabling the development of more effective environmental management and regulatory policies.

Health risk

The human health risk assessment was conducted by integrating exposure parameters and the ADI values for each antibiotic across different age groups—children, adolescents, and adults—based on seafood consumption patterns (Supplementary Fig. 4). For most of the antibiotics assessed, health risks were relatively low. However, 11.4% of the antibiotics, including SMX, EFX, OA, RTM, and CLM, presented moderate or higher health risks. Notably, OA posed a high health risk to all age groups. These antibiotics require stringent control measures to mitigate potential health risks.

Further analysis of health risks based on seafood consumption across different age groups (Fig. 5d) revealed that adolescents (6–18 years) had the highest health risk, followed by children (2–5 years), and lastly, adults. This finding contrasts with other studies that have reported increasing health risks with age. The discrepancy arises from the differences in the food items analyzed. While other studies focused on drinking water or edible fish168,169, this study specifically investigated seafood consumption. Children aged 2–5 years consume less seafood on average (29.05 g day−1) compared to adolescents (80.55 g day−1) and adults (91.6 g day−1). Additionally, while the seafood consumption between adolescents and adults is relatively close, adolescents’ lower body weight (mean 40.1 kg) makes them more vulnerable to higher antibiotic exposure compared to adults (mean 60.6 kg). Thus, adolescents, particularly in high-risk marine areas, should be prioritized for health risk mitigation.

It is worth noting that in recent years, 60% of the areas with HQS-SUM greater than 0.1 (moderate or higher risk) were predominantly in Asian seas. In high-risk areas such as the Bohai Sea37,47 and Pearl River Delta50 in China, as well as various mariculture farms in South Korea49, the overall seafood consumption risk (HQS-SUM) reached or approached high-risk levels across all age groups. Among these regions, South Korean marine farms49 exhibited the highest combined health risk, with the consumption of all seafood types, except crab, reaching a moderate risk, while the overall combined health risk from consuming all types of seafood reached a high risk level. This is because the extensive use of veterinary antibiotics in these regions has led to significant residues in both seawater and seafood, which are subsequently transferred to humans through seafood consumption134. These highlight the urgent need for strict regulation of antibiotic use in aquaculture and marine farming. The health risks associated with different seafood types are ranked as follows: fish > mollusks > shrimp > crab. This suggests that reducing the consumption of fish and mollusks could be an effective strategy for minimizing human exposure to antibiotic residues in high-risk areas.

In light of these risks, strict national standards on residue limits must be enforced, and effective withdrawal periods should be established to ensure antibiotics in seafood reach safe levels before consumption49. Public health campaigns should educate consumers on avoiding seafood species with high antibiotic residues. More importantly, more regulated antibiotic use and stricter emission controls are needed to reduce antibiotic contamination in seafood at its source.

Uncertainties

Although the RQ of individual antibiotics decreased compared to the “worst-case scenario”, most reductions were within one order of magnitude (Supplementary Figs. 5–8). In seawater, 81.6% of marine areas were classified as high risk under the worst-case MRQ, while this proportion dropped to 63.2% and 57.9% for the mean and median MRQs, respectively (Supplementary Table 11). Similarly, areas categorized as moderate risk declined by about 10%. The 95% confidence interval for MRQ in global seawater ranged from 0 to 29.2 at the lower bound and from 0.145 to 59.4 at the upper bound. Approximately 60% of marine areas exhibited a > 50% probability of high risk, and the probability of moderate risk exceeded 80% in most regions (Fig. 6a). These findings indicate that the underlying risk remains substantial in many locations. In marine sediments, the 95% confidence interval for global MRQ ranged from 9.77 × 10−9 to 8.84 × 10−3 at the lower limit and from 7.68 × 10−6 to 2.02 at the upper limit. The proportion of areas with a medium risk classification declined markedly, from 39.1% under the worst-case assumption to 13% under the uncertainty-based estimate. High-risk probabilities were virtually absent in most areas, with the exception of the Southern Baltic Sea (Poland), which showed a high-risk probability of approximately 17%. These results suggest that ecological risks in sediments are generally lower than in seawater but may still be significant in localized hotspots. Therefore, marine regions with relatively high MRQs and a substantial probability of high risk should be prioritized for ecological risk control and monitoring.

a Mixed ecological risk of antibiotics (low risk (MRQ < 0.1), moderate risk (0.1 < MRQ < 1), and high risk (MRQ > 1)); b probability of generating risk of AMR development; and c the combined health risk of antibiotics in three age groups (2–5-years-old: children, 6–18-years-old: adolescent, and >18-years-old: adult) (low risk (HQS < 0.1), moderate risk (0.1 < HQS < 1), and high risk (HQS > 1)).

In most regions, the majority of antibiotics posed very low AMR risks (<0.1%) (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table 12). However, certain antibiotics in ten regions exhibited AMR development probabilities exceeding 10%. Notably, TYL in the coastal waters of Costa Rica showed a 75% probability of AMR risk, indicating a high likelihood of promoting AMR. Other antibiotics with elevated AMR risk probabilities included TMP in Laizhou Bay (Bohai Sea), EFX in the Southern Baltic Sea (Poland), ATM in the Mediterranean coastal lagoon (Southeastern Spain) and False Bay (Cape Town), and CIP in Antarctic waters. Interestingly, CEL, which posed a negligible ecological risk under both assessment approaches, showed an 8.26% probability of AMR development in the South China Sea, highlighting the importance of AMR-specific risk assessment. These antibiotics and associated regions should be identified as AMR-priority control areas. Moreover, even compounds with low environmental concentrations and minor ecological risks should not be dismissed, as they may still contribute to resistance selection and dissemination.

For human health risk (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 13), only mariculture farms in South Korea showed a non-negligible probability (10%) of high health risk. Several other regions exhibited moderate risk, ranked by probability as follows: mariculture farms (South Korea) > Bohai Sea (China) > Kalk Bay Harbour (South Africa) > Pearl River Delta (China) > False Bay (Cape Town). HQs based on the mean and median values were significantly lower than those estimated under the “worst-case scenario”, only 4.68–46.4% of the worst-case HQs. The 95% confidence interval for HQs ranged from the lowest levels observed in Eastern, Southern, and Western Hong Kong waters (1.57 × 10−6 to 9.16 × 10−5) to the highest values in South Korean mariculture farms (0.0693–2.05). Most regions showed low HQs based on mean and median values, indicating generally low health risks. Only the mariculture zones in South Korea and the Bohai Sea reached moderate risk levels. Importantly, the probability of moderate health risk (HQs > 0.1) for children and adolescents, especially the latter, was substantially higher than for adults. These findings underscore the necessity for age-specific strategies in seafood consumption guidelines.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive review of the sources, pollution levels, environmental behavior, and risks of antibiotics in marine environments worldwide. SAs, FQs, MAs, and TCs were identified as the most prevalent antibiotic classes, with SMX and TMP being the most frequently detected compounds in seawater and biota. Antibiotic concentrations in seawater ranged from ND to 332440 ng L−1, with TMP reaching the highest levels. In sediments, concentrations ranged from ND to 1515 ng g−1, with TMP and TC most commonly detected, while OTC exhibited the highest levels. In biota, concentrations ranged from ND to 3341 ng g−1, with OA showing the highest measured concentration. China accounted for the majority of studies on marine antibiotic contamination, indicating severe pollution in its coastal areas. Antibiotics in the marine environment migrate and transform across the atmosphere, seawater, sediments, and biota. Marine-specific conditions influence antibiotic behavior differently compared to terrestrial systems. Coexisting contaminants, such as heavy metals, plastics, and phages (as coexisting viruses), further exacerbate environmental risks.

Antibiotics negatively impact marine organisms, promoting ARGs expression and posing risks to human health. Ecological risk assessments revealed that 29.2%, 6.94%, and 5.56% of antibiotics globally posed high risks to algae, invertebrates, and fish, respectively, with the coastal waters near Costa Rica presenting the greatest ecological risk. Despite the lower RQ observed for higher trophic level organisms, attention should still be given to their potential long-term effects and the risk of bioaccumulation through food chains and food webs. Thirteen antibiotics, including ATM, CEL, and MET, were identified as potential drivers of AMR despite their low ecological risk. Health risk assessments showed that adolescents (6–18 years) faced the highest health risk. Across all age groups, SMX, SCP, EFX, RTM, and CLM posed moderate risks, while OA presented a high risk. High health risks were observed in the Bohai Sea and Pearl River Delta in China, as well as in mariculture farms in South Korea. This study uses a dual assessment strategy for environmental risk, compared to the “worst-case scenario”, high mixed ecological risks decreased by 20% under uncertainty analysis, yet 60% of marine areas still had >50% probability of high risk. Several regions showed >10% AMR risk, and South Korea’s mariculture farms posed notable health risks, especially for children and adolescents.

To address the growing global challenge of antibiotic contamination and the associated emergence and spread of ARBs and ARGs in the marine environment, future research should prioritize several key areas. These include (1) investigating the sources of antibiotics, such as industrial, agricultural, and domestic origins, along with their distribution, migration, and transformation across different marine regions and depths; (2) examining the risks associated with the co-occurrence of antibiotics and other contaminants, such as plastics and heavy metals, particularly how these interactions influence antibiotic behavior and promote the spread of resistance; (3) exploring the mechanisms and distribution of ARGs, particularly their transport, transformation, and reproduction in relation to antibiotic concentrations; (4) comprehensive monitoring and assessment of the occurrence and risk of antibiotics in the marine environment in under-studied regions to improve the global assessment system; (5) Strengthening research on the toxicity of understudied antibiotics to marine organisms to improve the accuracy of ecological risk assessments in marine ecosystems; (6) developing advanced monitoring technologies, such as high-precision biomarkers and remote sensing, to detect low-concentration antibiotics and ARGs and enable intelligent environmental monitoring; (7) integrating environmental, hydrological, and meteorological data to construct predictive models that consider the effects of climate change on antibiotic and ARGs distribution; (8) assessing the ecological impacts of antibiotics on biodiversity, food webs, and ecosystem functions, incorporating broader chronic exposure effects to inform risk management; and (9) designing environmentally friendly and cost-effective technologies to remove antibiotics and ARGs from marine environments.

Effective mitigation of antibiotic contamination requires integrating scientific research, policy, and technological innovation. Key strategies include (1) targeting antibiotics with severe pollution and high risks, such as SAs and MAs in seawater, FQs and TCs in sediments, and bioaccumulative FQs in biota; (2) reducing emissions at the source by promoting sustainable agricultural practices like green farming and enforcing stringent standards on antibiotic use and discharge; (3) establishing national and international monitoring networks to regularly track antibiotic contamination in marine areas and provide reliable data for policy formulation; (4) strengthening environmental regulations, such as implementing stricter water quality and discharge standards with penalties for violations; (5) upgrading wastewater treatment facilities, particularly for mariculture wastewater and rural sewage, to improve the removal efficiency of antibiotics and ARGs; and (6) considering future human activities, including the impacts of climate change, on antibiotic contamination and ARGs expression, integrating these factors into comprehensive mitigation plans.

Effective management should prioritize regions and antibiotics with elevated environmental risks. Future research should focus on robust methods for monitoring and predicting antibiotic behavior in marine environments. Coordinated efforts across monitoring, prediction, and control strategies are essential to mitigate antibiotic contamination effectively.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The review process of this study is illustrated through the PRISMA (Preferred Items for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) flow chart (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The literature search focused on themes related to the occurrence, environmental behavior, and ecological effects of antibiotics in marine ecosystems. Searches were conducted across databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The review includes both original research and review articles published over a span of 15 years, from 2010 to 2025. Keywords used in the search strategy combined the term “antibiotic” with terms such as marine, ocean, seawater, sediment, seafood, organism, biota, offshore, gulf, coastal, or coastline. Various combinations and permutations of these terms were employed across the different databases. All retrieved articles were systematically organized and manually screened. Reference lists were reviewed to identify additional relevant studies, and duplicates were subsequently removed. Data included in the review were extracted directly from the original studies, encompassing information on sources, pollution levels, environmental behavior, ecological impacts, and human health risks of antibiotics in the global marine ecosystem.

To evaluate the extent of antibiotic contamination in marine ecosystems globally, studies reporting measured antibiotic concentrations were selected based on the following three criteria:

-

(1)

The study provided actual monitoring data on antibiotic concentrations in seawater, marine sediments, or marine organisms.

-

(2)

Sampling locations were clearly recorded, with geographic specificity to a particular country or region.

-

(3)

Sampling and analytical methods were scientifically robust and clearly described. Samples were collected from various marine environments, including coastal zones, offshore waters, estuaries, and bays. Samples were promptly transported to laboratories for concentration analysis after collection. Quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) were implemented, and detection methods included liquid chromatography (LC) and gas chromatography (GC) coupled with mass analyzers (such as LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and LC-MS/qTOF).

The review covers data on 80 antibiotics across 50 marine areas in 20 countries or regions. These antibiotics belong to various classes, including sulfonamides (SAs), fluoroquinolones (FQs), macrolides (MAs), tetracyclines (TCs), chloramphenicols (CPs), β-lactams (βLs), and others. A detailed summary of the antibiotics considered is provided in Supplementary Table 2. Although studies using LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS, and LC-MS/qTOF were considered during the literature selection process, all included studies ultimately employed LC-MS/MS for antibiotic quantification, ensuring methodological consistency. Extracted data were systematically categorized by antibiotic class, environmental medium, and geographic location to create a database for further analysis (Supplementary Table 6). The mean, median, and range of antibiotic concentrations in the global marine environment, as well as the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ), are presented in Supplementary Tables 7–9. Supplementary Table 10 summarizes the instruments for the determination of antibiotic concentration in each study.

Environmental risk assessment

The ecological risk of antibiotics in seawater and marine sediments was evaluated using toxicity data derived from three trophic levels of aquatic organisms: algae, invertebrates, and fish52. This assessment followed the framework outlined in the EU technical guidance document on risk assessment, employing the RQ approach as a quantitative metric to characterize ecological risk10. RQ is obtained by dividing the measured concentration by the predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) (Eq. (1)). PNEC is calculated based on toxicity data of antibiotics on organisms, but due to the lack of toxicity data, the PNEC of some antibiotics is predicted by the ECOSARv2.0 software developed under the supervision of the United States Environmental Protection Agency42. Based on established classification criteria, risk levels were categorized as low risk (RQ < 0.1), moderate risk (0.1 < RQ < 1), and high risk (RQ > 1)6.

Where MEC is the measured concentration of antibiotics in seawater (ng L−1) or marine sediments (ng g−1). In accordance with the “worst-case scenario” principle defined by the European Chemicals Agency in the Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment in 2016134, the maximum detected concentration within a given dataset was selected as the MEC value. PNECWater (ng L−1) is derived by dividing acute toxicity values (LC50, EC50) or chronic toxicity values (NOEC, ChV) by an appropriate assessment factor (AF). Standard AF values of 1000 and 100 were applied for acute and chronic toxicity data, respectively33. PNECSed was estimated by PNECWater (Eqs. (2 and 3)). The PNEC values are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

Where RHOsusp and RHOsolid were densities of wet suspended matter and the solid phase, valued 1150 and 2500 in kg (m3)−1, respectively. Fwater-susp and Fsolid-susp were the volume fractions of water and solid in suspended matter, defined as 0.9 and 0.1 in m3 (m3)−1. Foc-susp was the mass fraction of organic carbon in suspended matter, with an assigned value of 0.1 in kg kg−1. KOC was the partition coefficient of organic carbon-water (L kg−1), as shown in Supplementary Table 2.

In addition, a mixing concentration model was employed for ecological risk assessment of mixed toxicity to account for the synergistic effects of multiple antibiotics28. The mixed RQ MRQMEC/PNEC and MRQSTU for all detected antibiotics in each marine area are determined in Eqs. (4 and 5). The risk level definition for MRQ is the same as for RQ.

A standardized assessment framework, established by the AMR Industry Alliance, has been adopted to evaluate the potential risk of AMR emergence10. This approach involves a comparative analysis between the PNEC for AMR selection (AMR-PNEC) and the measured environmental concentrations of antibiotics (MEC). The lower of the PNEC-environment (PNEC-ENV) and the PNEC-minimum inhibitory concentration (PNEC-MIC) was selected as the AMR-PNEC value. The AMR-PNEC values for various antibiotics, as detailed in Supplementary Table 2, serve as reference thresholds. When MEC levels surpass the corresponding AMR-PNEC, the likelihood of AMR development is considered significant, necessitating further investigation.

Estimating human dietary exposure to antibiotics through seafood consumption is crucial for assessing health risks169. Four types of seafood, including shrimp, crab, mollusks, and fish, were selected for this analysis60. The daily intake of antibiotics was estimated based on the concentrations detected in marine biota and the daily seafood consumption of different age groups. The three age groups included were children (2–5 years), adolescents (6–18 years), and adults (>18 years). The health hazard quotient (HQ) was calculated by dividing the estimated daily intake (EDI, ng (kg bw d)−1) by the acceptable daily intake (ADI, ng (kg bw d)−1) of antibiotics (Eqs. (6 and 7)). ADI is designated as a dose that can be consumed by humans on a daily basis without adverse health effects (Supplementary Table 4). This is derived based on toxicological and pharmacological action data73,170, noting that some data are calculated by LTD (lowest therapeutic dose of pharmaceuticals)171. HQ was classified into three risk levels: low risk (HQ < 0.1), moderate risk (0.1 < HQ < 1), and high risk (HQ > 1). The coexistence of multiple antibiotics in the environment may pose a synergistic risk to human health172. Therefore, the combined health HQS was employed to assess the overall health risk of different age groups (Eq. (8)). HQs uses the same risk level definition as HQ.

Where MECMarine biota is the measured concentration of antibiotics in marine biota (ng g−1) that considers the worst case, using the maximum value for each antibiotic, in order to effectively identify high-risk antibiotics and to understand the safety of consuming seafood60,142. MSeafood is the daily consumption of seafood by different age groups (g d−1), and bw is the body weight (kg) (Supplementary Table 5).

Uncertainty analysis

To comprehensively assess the environmental risks of antibiotic contamination in the global marine environment, a dual-assessment strategy was employed in this study. First, a “worst-case scenario” approach was adopted using the maximum observed concentrations of antibiotics for risk estimation. Second, uncertainty analysis was conducted based on the statistical distribution of observed concentrations (median and range). Assuming a log-normal distribution, Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 iterations) were performed to derive probabilistic indicators, including the mean, median, risk probabilities, and confidence intervals. This dual approach enables a more systematic evaluation of risk variability and provides insight into the probability of high-risk scenarios.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Lei, L. et al. Current applications and future impact of machine learning in emerging contaminants: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 1817–1835 (2023).

Wu, D. L. et al. From river to groundwater: antibiotics pollution, resistance prevalence, and source tracking. Environ. Int. 196, 109305 (2025).

Huang, J. H. et al. Effect driven prioritization of contaminants in wastewater treatment plants across China: a data mining-based toxicity screening approach. Water Res. 264, 122223 (2024).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Sources, environmental fate, and ecological risks of antibiotics in sediments of Asia’s longest river: a whole-basin investigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14439–14451 (2022).

Qiu, X. J. et al. Occurrence, distribution, and correlation of antibiotics in the aquatic ecosystem of Poyang Lake Basin, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 479, 135656 (2024).

Lu, S. et al. Profiling of the spatiotemporal distribution, risks, and prioritization of antibiotics in the waters of Laizhou Bay, northern China. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127487 (2022).

Zhao, J. L. et al. Comprehensive monitoring and prioritizing for contaminants of emerging concern in the Upper Yangtze River, China: an integrated approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 135835 (2024).

Lee, K. et al. Population-level impacts of antibiotic usage on the human gut microbiome. Nat. Commun. 14, 1191 (2023).

Ouyang, B. W. et al. Recent advances in environmental antibiotic resistance genes detection and research focus: from genes to ecosystems. Environ. Int. 191, 108989 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Profiles, drivers, and prioritization of antibiotics in China’s major rivers. J. Hazard. Mater. 477, 135399 (2024).

Sommeria-Klein, G. et al. Global drivers of eukaryotic plankton biogeography in the sunlit ocean. Science 374, 594–599 (2021).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. Global biogeography of microbes driving ocean ecological status under climate change. Nat. Commun. 15, 4657 (2024).

Xu, N. H. et al. A global atlas of marine antibiotic resistance genes and their expression. Water Res. 244, 120488 (2023).

Yang, Q. L. et al. Antibiotics: an overview on the environmental occurrence, toxicity, degradation, and removal methods. Bioengineered 12, 7376–7416 (2021).

Chen, W. B. Analysing seven decades of global wave power trends: the impact of prolonged ocean warming. Appl. Energy 356, 122440 (2024).

McEachran, A. D. et al. Antibiotics, bacteria, and antibiotic resistance genes: aerial transport from cattle feed yards via particulate matter. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 337–343 (2015).

Chen, H. Y., Jing, L. J., Teng, Y. G. & Wang, J. S. Multimedia fate modeling and risk assessment of antibiotics in a water-scarce megacity. J. Hazard. Mater. 348, 75–83 (2018).

Lulijwa, R., Rupia, E. J. & Alfaro, A. C. Antibiotic use in aquaculture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: a review of the top 15 major producers. Rev. Aquacult. 12, 640–663 (2020).

González-Gaya, B., García-Bueno, N., Buelow, E., Marin, A. & Rico, A. Effects of aquaculture waste feeds and antibiotics on marine benthic ecosystems in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 151190 (2022).

Wang, X. T., Lin, Y. F., Zheng, Y. & Meng, F. P. Antibiotics in mariculture systems: A review of occurrence, environmental behavior, and ecological effects. Environ. Pollut. 293, 118541 (2022).

Zhu, Y. G. et al. Continental-scale pollution of estuaries with antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16270 (2017).

Gao, H., Li, B. & Yao, Z. W. Advances in research on the presence and environmental behavior of antibiotics in the marine environment (in Chinese). Environ. Chem. 42, 779–791 (2023).

Liu, J. C., Zhang, C. Y., Zheng, Y., Hu, E. & Li, M. Occurrence, fate, and ecological risk of PAEs, PFASs, antibiotics in industrial, urban and rural WWTPs in Shaanxi Province, China. J. Water Process Eng. 68, 106324 (2024).

Wang, B. Q., Xu, Z. X. & Dong, B. Occurrence, fate, and ecological risk of antibiotics in wastewater treatment plants in China: a review. J. Hazard. Mater. 469, 133925 (2024).

Zhao, M., Huang, K., Wen, F. F., Xia, H. & Song, B. Y. Biochar reduces plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance gene transfer in earthworm ecological filters for rural sewage treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 487, 137230 (2025).

Liu, K. et al. Occurrence and source identification of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in groundwater surrounding urban hospitals. J. Hazard. Mater. 465, 133368 (2024).

Bielen, A. et al. Negative environmental impacts of antibiotic-contaminated effluents from pharmaceutical industries. Water Res. 126, 79–87 (2017).

Sun, C. S. et al. Spatial distribution and risk assessment of certain antibiotics in 51 urban wastewater treatment plants in the transition zone between North and South China. J. Hazard. Mater. 437, 129307 (2022).

Hu, J. R. et al. Animal production predominantly contributes to antibiotic profiles in the Yangtze River. Water Res. 242, 120214 (2023).

Delgado, N., Orozco, J., Zambrano, S., Casas-Zapata, J. C. & Marino, D. Veterinary pharmaceutical as emerging contaminants in wastewater and surface water: an overview. J. Hazard. Mater. 460, 132431 (2023).

Gao, F. Z. et al. Swine farming shifted the gut antibiotic resistome of local people. J. Hazard. Mater. 465, 133082 (2024).

Li, Y. L. et al. Current status and spatiotemporal evolution of antibiotic residues in livestock and poultry manure in China. Agriculture 13, 1877 (2023).

Chen, Y. R. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics pollution the Yangtze River basin, China: emission, multimedia fate and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 465, 133247 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Occurrence, spatial distribution and ecological risks of antibiotics in soil in urban agglomeration. J. Environ. Sci. 125, 678–690 (2023).

Cáliz, J., Subirats, J., Triadó-Margarit, X., Borrego, C. M. & Casamayor, E. O. Global dispersal and potential sources of antibiotic resistance genes in atmospheric remote depositions. Environ. Int. 160, 107077 (2022).

Xie, J. W., Jin, L., Wu, D., Pruden, A. & Li, X. D. Inhalable antibiotic resistome from wastewater treatment plants to urban areas: bacterial hosts, dissemination risks, and source contributions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 7040–7051 (2022).

Han, Q. F., Song, C., Sun, X., Zhao, S. & Wang, S. G. Spatiotemporal distribution, source apportionment and combined pollution of antibiotics in natural waters adjacent to mariculture areas in the Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea. Chemosphere 279, 130381 (2021).

Choi, S. et al. Antibiotics in coastal aquaculture waters: Occurrence and elimination efficiency in oxidative water treatment processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 396, 122585 (2020).

Li, S. et al. A duodecennial national synthesis of antibiotics in China’s major rivers and seas (2005–2016). Sci. Total Environ. 615, 906–917 (2018).

Oesterle, P., Gallampois, C. & Jansson, S. Fate of trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole and caffeine after hydrothermal regeneration of activated carbon. J. Cleaner Prod. 429, 139477 (2023).