Abstract

This study presents a computational framework for optimising a hip implant through a functionally graded biomimetic lattice structure, designed to reduce stress shielding. The optimisation technique, inspired by an inverse bone remodelling algorithm, promotes even stress distribution by reducing density and stiffness in regions with high strain energy compared to a reference level. The resulting non-uniform density distribution showed lower density levels along the implant stem’s sides and higher density around its medial axis. This optimised material distribution was captured using mapping of a triply periodic minimal surface lattice structure on the implant, creating porous lattice surfaces within the solid structure. The porous implant’s performance was evaluated using a finite element bone remodelling algorithm, comparing its bone response to a femur with a fully solid implant model, in terms of stress distribution and mass change. Results demonstrated improved bone formation at the bone-implant interface and enhanced stress transmission to the surrounding bone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Joint replacement surgeries, such as total hip replacement, are one of the successful interventions among orthopaedic treatments, enhancing patient quality of life and relieving pain in the long term. However, in some cases, the orthopaedic implants fail, and a revision surgery is required. Aseptic loosening is one of the main causes of implant failures, whereby local bone resorption takes place at the bone-implant interface1,2. The vast majority of orthopaedic implants are made of solid metals, such as cobalt chromium alloys, 316L stainless steel, and titanium-based alloys. However, the stiffness of these materials is orders of magnitude higher than that of the surrounding bone2,3,4. The large stiffness mismatch at the implant-bone interface results in stress shielding, whereby most of the load is carried by the implant instead of the bone tissue itself4,5. As bone is an adaptive tissue, the reduced mechanical loading on the bone results in local bone resorption and loss of bone mineral density in the region, which leads to contact loosening in the interface2,6 and ultimately implant failure.

Several approaches have been used to address the issue of stress shielding, with the aim of reducing the stiffness of the hip implant stem. These approaches have targeted the geometric design of the stem region, material properties of the implant, or a combination of both geometrical and material changes2,4. Geometric design modifications include alterations to cross-section geometry design7, addition of holes and ridges to the stem8,9, and femoral stem length10,11, although it remains challenging to resolve the stiffness mismatch or achieve optimum load distributions with macro-level changes to implant design. On the other hand, micro-level design modifications included applications of biomimetic polymer-composite materials12. With advances in additive manufacturing techniques, a novel category of materials has recently emerged that are referred to as meta-biomaterials, that is, an intermediate concept that lies between material and structure13. The application of meta-materials in addressing the stress shielding problem includes using different functionally graded (FG) lattice structures in porous hip implant designs5,14,15, and novel meta-biomaterials in orthopaedic device design, such as auxetic and deployable meta-implants1,16.

Porous lattice structures have been used both as surface coatings in implants to address issues with fixation by promoting bone ingrowth2,17,18, and to address the stiffness mismatch between implant and bone using a more lightweight implant design4,5,15,19,20,21. This advantage has been clinically approved by evidence of enhanced bone regeneration using optimised 3D titanium-mesh scaffolds in sheep22, with a computational optimisation framework developed accordingly23. However, many current hip implant designs with FG structures are limited to uniform lattices5,20, or simple gradient lattice structures24,25,26. Although several more advanced lattice models have been suggested based on hybrid lattice designs5,19, and optimised material distribution throughout the implant, using tetrahedron-based cells3,4, and body centric cubic (BCC) structures14,21. The compatibility of neighbouring unit cells in FG materials in hip implant design has been optimised through connectivity between adjacent microstructural unit cells in two dimensions27. While these studies have introduced novel FG implant structures, it is notable that many have not achieved true optimisation as their design process has not considered the long-term remodelling process of the bone3,21,27, which is highly dependent on the dynamic loading conditions experienced at the bone-implant interface. Furthermore, certain approaches have not been able to map the density distribution to small sub-domains in a continuous manner4. Porous implant designs have also been proposed using triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) structures25,28, which have been mechanically investigated29,30. Such approaches have used simple uniform TPMS lattices24,25, or multi-morphology lattice structures31, representing graded mechanical requirements. However, while TPMS lattice structures offer morphological and mechanical properties that mimic trabecular bone, current approaches in hip implant design have not yet sought to map optimised material distribution using TPMS.

The objective of this study is to develop a FG biomimetic lattice-based hip implant design that is structurally optimised to limit stress shielding to the surrounding bone. The study develops and implements a new optimisation algorithm based on an inverse bone remodelling logic, whereby the optimised density distribution for the orthopaedic implants could be determined. Using the element-by-element density mapping lattice technique developed in LatticeWorks32, a non-uniform FG TPMS gyroid structure was mapped to the implant geometry to produce the optimised structure, with a solid shell surrounding the porous structure. The long-term adaptive response of the bone tissue was evaluated using a strain energy density-based bone remodelling scheme, and the performance of the solid and FG porous implant was compared. Also, this study includes an additively manufactured prototype of the implant, demonstrating its manufacturability.

Results

Bone remodelling in solid implant

Figure 1 shows the temporal evolution of Von Mises stress distribution, and subsequently bone density, in the femur following implantation of the bone remodelling algorithm on a fully solid implant design. Stress values at the outer layers of the cortical region triggered a positive remodelling scheme, and the bone density increased in these regions. As shown in Fig. 1b, the density distribution started from a homogenous state of \({\rho }_{{{\rm{initial}}}}=1.65{{\rm{g}}}/{\rm{cm}}^{3}\), which is notable that this state was not a homeostatic condition. This means that the bone remodelling algorithm showed distinct changes in the early iterations, with high bone density remaining in high stress regions and regions of bone resorption detected in non-load carrying regions in the proximal femur.

a Development of Von Mises stress distribution, and b bone density variation over time, for the femur with a fully solid implant, under the remodelling algorithm. Final Von Mises stress distribution within c cut view of the femur with fully solid implant assembly, d bone part and e solid implant part.

Figure 1c shows the Von Mises stress distribution in the assembly of a femur with a fully solid implant, following the bone remodelling algorithm, is converged. Figure 1c shows that at the bone-implant interface, the solid implant elements are under higher stress levels compared to the surrounding bone. In the bone section in Fig. 1d, the circumferential cortical region carries more stress compared to the concentric bone elements within the bone canal, and stress reduces as getting closer to the near-the-implant trabecular region. The implant section, on the other hand, in Fig. 1e, shows an uneven stress distribution throughout the stem region, with concentrated stress in the bone-implant interface. Maximum stress in the implant was \(359{{\rm{MPa}}}\), in the neck region of the implant.

Optimisation of density distribution and functionally graded lattice mapping

Figure 2 shows how the bone density distribution and Von Mises stress evolved over time, as a result of the optimisation algorithm. Here, the element density was originally \(4.06{{{g}}}/{{cm}}^{3}\) throughout the entire structure. During the optimisation process, the density and stiffness started to reduce on the sides of the proximal region of the stem. Low-density regions evolved horizontally and vertically over time. On the other hand, the density in the distal region did not reduce over the analysis time. The final density distribution is shown at time \(t=6.16\), where the total mass reduction within the structure reached 20%.

Figure 3a, b shows the resulting non-uniform density distribution in the design region of the implant, as a result of the optimisation algorithm on the solid implant. In this suggested material distribution, the core of the implant had greater density, whereas the density of material was reduced on the sides of the medial axis in the implant. The reduced density regions were under higher stresses, as shown in Fig. 2b and went under the reducing stiffness loop in the inverse remodelling algorithm. A minimum allowable density of \(1.36\,{{\rm{g}}}/{\rm{cm}}^{3}\) corresponds to the volume fraction of 30% in elements. The narrow bottom part of the stem also maintained higher density values, as it was not under high stress values. The density distribution was translated to a relative density distribution, and according to the gyroid power law equations and using Eq. (10), and Young’s modulus distribution map over the design region was calculated, as shown in Fig. 3b.

The results of the mapping techniques are shown as step-by-step in Fig. 4. The binarized grid, shown in Fig. 4a, divides the domain into points that are inside the implant surface and the outside points. The interpolated element density data, as the results of FE optimisation, calculated for the inner grids, is shown in Fig. 4b. Based on the relative density vs. levelset equation in the gyroid structure in Fig. 4, the gyroid levelset distribution field was calculated, shown in Fig. 4c, and the density distribution field was mapped into a gyroid levelset field. The equivalent gyroid levelset variation was calculated to be [−1.5, 0.75], for volume fraction variation of [0.3, 1]. The normalised mapped gyroid field by the levelset values was rendered at an isovalue of one and is shown in Fig. 4d. This new gyroid field is non-uniformly graded, and captures the same gradient map, as shown in the density distribution field in Fig. 3, enabling to draw the gyroid isosurface and create the porous structure.

Mapping density lattice generation, a binarized grid over the bounding box of the implant stem, b element density distribution interpolated on the grid, c equivalent gyroid levelset field to the density distribution, d gyroid function values created on the levelset field, e isosurfaces on the generated mapping gyroid field in grey, and outer face boundary surface of the implant shown in pink.

The resulting graded gyroid lattice surface with optimised density distribution is shown in Fig. 4e. The gyroid surface, shown in grey in Fig. 4e, represents a porous region that was needed to be removed to capture the derived density distribution map within the implant region. The other surface is the implant original boundary surface, which is shown in pink in Fig. 4e. To construct the implant, the area between the two surfaces was solidified that the porous gyroid was deducted from it.

The generated the field for the coating shell (\(R\)) is shown in Fig. 5a, in which the coating shell is shown as negative field values. This shell field overwrites the gyroid field function (\(\varphi\)) on the surface boundary with thickness, \(t\). The combined field function of these two fields were rendered at isovalue of one, and the resultant surfaces is shown in Fig. 5b. The inner grey surface is generated based on the gyroid field function, and the surrounding pink surface is generated based on the original implant boundary surface, and the thickness gap is applied in between these two surfaces. With the gyroid voids surface inside, and a cover surface on the boundaries, the space between the two surfaces was solidified, and slice images of the final design are shown in Fig. 5c.

Bone remodelling in functionally graded porous implant

The results of the bone remodelling algorithm following implantation of the FG porous implant were compared to the femur with a fully solid implant. Figure 6 shows the density and elastic modulus of the surrounding bone for the femur with porous and fully solid implants, following the bone remodelling algorithm. According to Fig. 6a, the density of elements was higher in the bone-implant interface when implanted with the FG porous design. As a result, the elastic modulus of the elements was higher in these regions, as shown in Fig. 6b, for the porous implant case compared to the solid implant.

The bone mass of element sets in the two cases of femur with fully solid and porous implant is summarised in Fig. 6c. The percentage of change in bone mass with the porous design implant, compared to the solid implant design, is reported for Gruen zones and bone-implant interface elements, as shown in Fig. 6d, e. According to these results, the bone mass particularly increased in Gruen zones 3 and 5. However, Gruen zones 6 and 7 showed mass reduction, and Gruen zones 1, 2 and 4 did not show any considerable mass change, comparing the porous implant with the solid implant design. Although, the total bone mass with the two implant cases were almost similar, the local changes of bone mass on the bone-implant interface elements, showed an overall mass increase of 33%, based on Fig. 6e. According to the results, reducing the implant elastic modulus created a local increase in bone mass for the surrounding bone, although not changing the overall bone mass.

Figure 7 shows the Von Mises stress distribution on the bone, implants, and assembled systems for both implant designs. In the case of the FG porous implant, as shown in Fig. 7a, b, bone elements experienced higher stress at the bone-implant interface region. Subsequently, in the high-stress regions, positive remodelling was triggered in those elements, and higher density was reported, as shown in Fig. 6a.

According to Fig. 7c, in the FG porous implant design, the stress has increased on the solid shell region to compensate for the material reduction. The stress distribution has also been shifted more towards the medial axes of the implant in the porous implant design. The middle section of the FG porous implant, shown in red window in Fig. 7c, had lower porosity in and was also under higher stress levels compared to the same regions in the fully solid implant design. However, in the lower parts of the FG porous implant, shown in the green window in Fig. 7c, elements were not in direct surface contact with the surrounding bone. Therefore, they showed lower stress values. There is a small region on the porous implant with high stress concentration, which is due to the contact with the geometrical artefacts in the bone marrow. Moreover, the neck region of the FG porous implant, as the critical region, still maintained a safety factor of 2 \({{{SF}}}=\frac{{\sigma }_{{{\rm{yield}}}}}{{\sigma }_{max }\,}\)2, considering the yield stress of the material.

Prototype printing of functionally graded porous implant

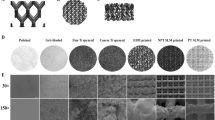

To demonstrate the internal porous structure of the implant design, it was printed in two sections, cut from the medial plane, as shown in Fig. 8a, b shows the printed prototype. Due to the fact that components manufactured by DMLS typically have as-fabricated surface defects33, the inner pore surfaces include particles of unmelted metal powder or have pores created as a result of weld pool collapses. However, the resolution of the model, the minimum pore size in the model, and the particle size affect the final product quality.

Discussion

This study developed a FG hip implant design using a gyroid lattice-based structure that was structurally optimised through an inverse bone remodelling algorithm. The FG gyroid lattice structure was mapped on an optimised density distribution field in the implant stem region. The density optimisation technique was based on an inverse bone remodelling logic, which produced a structure that had low density regions on the sides of the medial axis of the stem and in the proximal region, while having a higher density at distal part of the stem (Fig. 3). The performance of the FG porous implant design was evaluated using a bone remodelling algorithm. Local increases in the bone mass distribution were found for the FG porous design, with higher stress successfully transferred to the bone elements at the bone-implant interface following implantation.

The optimised porous implant design that was developed in this study represents a novel design, with notable differences to existing commercially available porous implant designs that have not been optimised based on loading distribution. For example, the Arcos one-piece34 femoral revision system (Zimmer Biomet, USA, 2016) simply uses a randomly distributed porous structure throughout the component. Other devices tend to only include porosity on surface35, as shown in Fig. 9. Considering new additively manufactured designs of FG porous implants, very few of them are based on an optimised material distribution3,4,36, and in most cases, the gradient structure is a uniform or simple linear graded lattice structure25,37, or else use hybrid designs, including multi-material lattice structures1,5,19,38. However, the graded lattice pattern that was produced in the current study is non-uniform and dictated by a material optimisation algorithm, and it cannot simply be described by a linear gradient lattice. Here, the density mapping technique was used in the graded lattice design that follows an element-by-element tailored structural properties, instead of using a multi-morphology lattice design.

a VerSys HA/TCP Fibre Metal Taper stem porous coated implant [from ref. 35] vs. b the new graded porous implant design.

While the resulting distribution map was aligned with other studies that have used alternative optimisation algorithms3,4, the element-by-element density mapping approach outlined here enabled a higher resolution grid point, which locally mapped continuous porous structure. This is in contrast to other methods4,15 that limited the number of sampling points to reduce computational cost, with these distributed through the structure to map the density distribution. In addition, this study provides the option to cover the porous implant using a solid shell, to offer the opportunity for applying an optimised porous coating on the surface, whereas in most gradient porous implant designs, the body of the implant consists of lattice structures. This generated a porous implant with gradient cell sizes and porosity on its surface4,14,27. Although the porosity might address the fixation by promoting bone growth in these implant designs, it needs more invasive techniques in case of a revision surgery39,40. The coated design was applied on the graded porous implant design, whereas in another study it was considered on a uniform BCC lattice structure37. Density-mapping lattices used in other studies were strut-based lattices, including BC lattices41, or tetrahedron lattices3,4. Although TPMS-based lattices have been used in hybrid lattice-based implant designs5, however as a density-based lattice structure, they have not been investigated before. Using the density mapping technique, introduced in LatticeWorks32, the results of the optimisation section were used to generate a FG lattice structure in the implant surface that had the optimised material distribution mapped.

The new implant design was evaluated and compared to the fully solid implant design, using a bone remodelling algorithm on the surrounding bone. The quantified stress levels and bone density showed locally higher stress and higher density on the surrounding bone elements, in the case of the porous implant design. The increased interface stress was an undesirable effect of the new design, which might increase the probability of failure in bone4,15. However, in this study, the resulting stresses in the optimised implant upon loading were safe when evaluated and compared to the yield strength of the material. Also, the increased stress value in the bone tissue served as a positive remodelling stimulus for the interface elements. Bone mass results showed a 33% increase on the bone-implant interface elements in the femur with porous implant, compared to the femur with a fully solid implant. Although the results did not show a considerable bone mass increase in the wider bone regions. The high stress regions in the implant and bone assembly were due to the geometry artefact and the step generated in the bone canal while excavating the implant hole. This study also has several limitations that should be considered. After THA, a patient’s most common dynamic activity is walking. Therefore, to calculate the changes in the physiological strain distribution following THA or bone remodelling, researchers typically looked at static load situations of the gait cycle42. However, in normal life, the femur is under other loading conditions as well that incorporates all the muscle loads. Therefore, the design can be evaluated in more loading conditions, to capture a more inclusive bone response, that incorporates the upper region of the femur bone as well, whereas in this design was shown to be under resorption and reduced in density. Also, the stress shielding effect can be quantified using the stress shielding increase (SSI) indicator2 that evaluates the response of the implanted femur with the intact femur response. For further assessment of the stress shielding effect, the SSI factor can also be calculated to compare the two solid and porous implant designs. However, in this work, the change of bone mass has been reported to assess the performance of the new implant, with reference to the femur with a solid implant. Furthermore, the sectioned prototype of the implant design was also 3D printed to demonstrate the manufacturability of the design, as well as additive manufacturing challenges. In this prototype, the sample was printed as two sides of the whole model. However, with the full model design, using powder bed technology, removing the remaining powder within the closed porous surface is not accessible as it is in the cut model. The additive manufacturing experience in this study showed that for future similar designs, a vent or powder removal channel needs to be considered at the design stage, to facilitate prototyping with the DMLS technique. Also, aluminium is not biocompatible within human body, and the real implants are available in other biocompatible materials43,44,45. In this demonstration of metal additive manufacturing, the material itself was not a matter of study. However, in future studies, it is recommended that the implant be printed in biocompatible materials. With the full implant model additively manufactures, the mechanical performance of the implant can be experimentally tested in terms of yield strength or fatigue in future works. However, this study is an inclusive package from modelling, optimisation, analysis, and prototyping that establishes the key aspects of the FG porous implant design. The process can be modified and customised in each step according to the specific application.

This study developed an optimised FG porous implant design, equipped with a solid shell coating, that showed improved long-term bone response. The optimisation technique was inspired by an inverse bone remodelling logic that promoted an even stress distribution throughout the design region by reducing the density and consequently the stiffness in regions where strain energy was higher than the reference level. The results of the optimisation technique were a density distribution field, that showed lower density on the sides of the implant stem, and higher material density around the medial axis and distal regions of the implant. The performance of the optimised FG porous implant design showed improved bone formation on the bone-implant interface. This study demonstrates how the computational frameworks developed in this work can be utilised to create FG lattice structures, incorporating structural optimisation techniques to facilitate customised implant design.

Methods

Model framework

A three-dimensional model was prepared using a hip implant and a femoral bone geometry. The implant model was created based on an identical configuration to a Zimmer M/L Taper implants (Zimmer Inc., USA, 2010). The bone was generated as a surface using a cloud point of a femur model from a previous study46. The generated parts with their dimensions are shown in Fig. 10, with the design domain in the hip stem region shown in green. To assemble the two parts, the implant stem surface was subtracted from the bone part, enabling the implant to be virtually inserted into the bone. The two parts, with linear elastic material properties (see section “Bone remodelling in solid implant”), were assembled as shown in Fig. 10c. Contact at the bone-implant interface was modelled as a node-to-surface interaction, with hard contact defined in the normal direction while the tangential direction was defined by a friction coefficient of 0.4547,48. The two generated parts were meshed using linear tetrahedral elements (C3D4), using TetGen49,50 algorithm, as shown in Fig. 10c. The FE model of the solid implant and bone parts consisted of 3812 nodes and a total of 17,700 elements, and 13,295 nodes and 54,784 elements, respectively.

This study considered four distinct steps in developing a FG porous implant. Firstly, an existing bone remodelling algorithm51,52 was implemented on the bone section to predict the bone tissue response to the implanted femoral implant and identify any instances of stress shielding. A second algorithm was developed to determine the optimised material distribution within the implant part, with the formulation of this algorithm based on the principle of an inverse remodelling logic. Subsequently, this optimised density distribution was mapped to a tailored density lattice structure on the implant through the appropriate mapping technique using the recently developed LatticeWorks toolbox32. LatticeWorks is an open-source MATLAB toolbox for lattice generation, facilitating the creation of nonuniform and density mapping lattice structures, and infill lattice generation. A new implant design was suggested through mapping the optimised material distribution. Finally, the bone remodelling algorithm was applied once again on the femur with porous implant and the performance in terms of stress shielding was evaluated and compared to the solid implant. The following sections describe the methods applied in each step in more detail.

Bone remodelling algorithm

A bone remodelling algorithm, inspired by Wolff’s Law, where the strain energy density (SED) is used as a feedback control variable, was implemented to determine the bone density distribution51,52. The algorithm adjusts density to balance SED around a reference value, triggering (1) positive remodelling (bone apposition), (2) negative remodelling (bone resorption), or (3) no change (lazy zone). The strain energy per unit of mass, \(S\), was based on the physiological loads applied and was calculated as Eq. (1):

in which \(\rho\) represents the density, \(\sigma\) is the tissue level stress based on element Von Mises stress, and \(\varepsilon\) is the strain tensor from the FE analysis. The average strain energy density per unit of mass is calculated over the integration points of each element. The applied remodelling algorithm updated the material properties of elements, according to their average strain energy per unit of mass \(S\), compared with a reference value, \({S}_{{{{ref}}}}\). The reference strain energy (\({S}_{{{{ref}}}}\)) was calculated based on the initial state of bone, as the homoeostatic stress and elastic modulus were \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{initial}}}}=68\,{{\rm{MPa}}}\), and \({E}_{{{\rm{initial}}}}=17\,{{\rm{GPa}}}\). The bone remodelling stimulus was the difference between the \({S}_{{{{ref}}}}\), and bone remodelling flag was defined as:

Based on the remodelling flag, the change an element’s apparent density was calculated according to,

in which \({dt}\) is the time of the increment, \(\tau\) is a time constant and assumed to be \(\frac{130}{28}\,{{{gm}}}{{{m}}}^{-2}{{{J}}}{{{g}}}^{-1}\) per day, and \(A(\rho )\) is the free surface area, and a function of density, defined as53:

The elements density is updated according to the remodelling flag, which was defined as:

The upper and lower density for the cortical bone elements was set to be \(\left[0.01,\,1.73\right]\,{{{g}}}\,{{cm}}^{-3}\). When the density was calculated, the Young’s modulus of an element was updated using Eq. (6)42,51.

Using the updated material properties at each increment, the FE solver updates the response of the system based on the boundary conditions. The maximum allowable density change in each iteration \({(\Delta \rho }_{\max })\) was limited to \(\frac{0.175}{28}{{{g}}}/{{cm}}^{-3}\) per day. The bone remodelling algorithm was considered converged when the change in density among the elements was lower than 0.002 in successive increments. The bone remodelling parameters are summarised in Table 1.

The bone remodelling algorithm is summarised in a schematic flowchart shown in Fig. 11, with the model implemented in the Abaqus/Standard54 solver, through a user-defined field Subroutine (USDFLD).

Density optimisation algorithm

An optimisation algorithm was developed based on an inverse-remodelling scheme to achieve a more homogenous stress distribution within an implant, by iteratively reducing stiffness via density adjustments in high-SED regions, promoting load redistribution.

The objective of the optimisation method was to reduce the total mass of the implant stem by 20%, while optimising SED distribution. This topological objective, targeting material reduction in the final design, was addressed by tuning the strain energy per unit of mass (\(S\)) of the elements, calculated using Eq. (1), compared to a reference strain energy (\({S}_{{{{ref}}}}\)). Mathematically, this is expressed as reducing the total mass (\(M\)) subject to the balanced SED (\(S-{S}_{{{{ref}}}}\)), where SED drives the optimisation, aligning with bone remodelling principles. The optimisation logic is governed by Eq. (7), in which the reference strain energy is considered \({S}_{{{{ref}}}}\,=1e-5{{{J}}}/{{g}}\), based on the original strain energy of the elements to initiate the optimisation.

in which \({\rho }_{i}\) and \({V}_{i}\) denote the apparent density and volume of the individual elements, respectively. The density change in each iteration was calculated as:

In the optimisation process, the density change was not a function of the surface free area. Therefore, \(A(\rho )\) the factor was considered as 1 in this algorithm. Based on the strain energy difference and the stiffness optimisation scheme, the elements' density was updated according to the remodelling flag:

The lower and upper bounds for the implant element density were set between \(\left[1.36,\,4.5\right]\,{{{g}}}\,\cdot\,{{cm}}^{-3}\), which corresponds to the relative density of [30%–100%], using implant material properties55. When the density was calculated, an element’s Young’s modulus was updated based on the gyroid power law equation29,30, using Eq. (10).

The flowchart of the optimisation scheme is shown in Fig. 12. While the optimisation targets a 20% mass reduction, the ultimate goal is to mitigate stress shielding, assessed post-optimisation via the bone remodelling algorithm (as per Section “Bone remodelling algorithm”).

Functionally graded biomimetic lattice structure tailoring density distribution

The LatticeWorks toolbox32, was used to map the optimised density distribution to a graded lattice structure. Using this toolbox, a grid was first generated in the bounding box enclosing the structure. An image matrix (\(D\)) was created using the grids to calculate the distance of individual grids from the nearest boundary face of the implant. This distance matrix was binarized to inside (\(D < 0\)) and outside (\(D > 0\)) of the design region. The FE model density data was then interpolated to the inner grids, using barycentric coordinates of the elements. The grid relative density data was then translated to the gyroid levelset (\(l\)) data using the gyroid relative density vs. levelset relationship and shown in Fig. 13. The gyroid field function (\(\varphi\))29 was evaluated on the grid points (\(X,{Y},{Z}\)), based on Eq. (11), with the isotropic frequency of \(70\pi\), that corresponded to the wavelength of \(3.5\,{{\rm{cm}}}\), in all three directions. Gyroid strut-based lattice choice with lower stiffness compared to sheet-based lattice56 aligns with the goals of reducing the stress shielding effect. The generated uniform gyroid field (\({\varphi }_{{{{uniform}}}}\)) was then normalised using the gradient levelset field (\(l\)), using Eq. (12). The new gyroid field (\({\varphi }_{{{{map}}}}\)) became non-uniform, mapping the graded density distribution.

Finally, the mapping gyroid field (\({\varphi }_{{{{map}}}}\)) was rendered at isovalue of one, where the uniform gyroid field (\({\varphi }_{{{{uniform}}}}\)) was equal to the levelset value (\(l\)), mapping the required relative density distribution.

The generated gyroid field was enclosed in a shell with a thickness of \(t=4\,{{\rm{mm}}}\), in terms of the distance value from the boundary surface of the implant stem in the image matrix. This step was done using density mapping with the shell technique in LatticeWorks32. According to this technique, a copy of the distance matrix (\(D\)) was adopted to categorise the grids within a certain distance from the boundary face. The gyroid mapping field (\({\varphi }_{{{{map}}}}\)) within the boundary region grids was replaced by the thickness field. With the new combined mapping and thickness field (\({\varphi }_{t,{{{map}}}}\)), inner porous surface and boundary shells were drawn using isolevel value at zero.

Bone remodelling in solid implant

With the FE model of the femur with a fully solid implant prepared in the section “Model framework”, the bone remodelling algorithm was applied to the surrounding bone part. The material properties and the boundary conditions that were applied are described in the following sections.

In the first section for the analysis, the implant material was considered as a titanium alloy, as an isotropic linear elastic material, with the mechanical properties reported in Table 242,48. The cortical bone section undergoes a remodelling algorithm, in which the material properties are updated in each solver increment. However, the allowed upper and lower limits of its Young’s modulus in the algorithm and considered yield strength are reported in Table 257,58.

The boundary conditions and applied loading for this case considered the static forces of a 700N person walking at normal speed19,59,60. The bone-implant assembly was subjected to the maximum muscle forces acting on the bone at node \(P2\), and stem head contact force at node \(P1\), as shown in Fig. 14. A reduced muscle system was considered with a combination of abductors, the tensor fascia latae, and the vastus lateralis muscles, as summarised in Table 3. The bottom ends of the femoral bone were defined as fixed support, considering the contact surfaces of the knee joint. The applied boundary conditions are visualised in Fig. 14.

To evaluate the stress shielding effect in the bone-implant assembly, the FE model results were studied after convergence criteria were achieved, in ten iterations of remodelling, and the bone mass was analysed on the bone elements. The femur bone was segmented into seven Gruen zones2,4, which are often used in clinical settings to evaluate THA performance. Also, to study the local effects of the implant, a bone-implant interface element set was defined on the bone section. These element groups are shown in Fig. 15, for Gruen zones and bone-implant interface elements.

Bone element density and element volume were exported from the results, and bone mass was calculated for the element sets defined. The change in elements bone mass was compared for the porous FG implant design with the solid implant design, and the percentage of change in bone mass was reported based on,

Optimisation of density distribution and functionally graded lattice mapping

The optimisation algorithm was applied to the implant design section in the bone-implant assembly, as shown in Fig. 10c. In this assembly, the bone section was defined as an isotropic linear elastic material, with a constant Young’s modulus of \(17\,{{\rm{GPa}}}\), and Poisson ratio of \(0.3\). All boundary conditions and applied loads were the same as those described in the bone remodelling model, as presented in Table 3 and Fig. 14. The implant optimisation algorithm was considered converged when the mass reduction among the elements reached lower than 20% of the original mass. The optimisation algorithm was only applied to the design region of the implant, as shown in Fig. 10a, and the neck region maintained solid with material properties stated in Table 2.

Bone remodelling in functionally graded porous implant

To evaluate stress shielding in the newly designed porous implant model, a FE model similar to the model in Section “Model framework” was developed, with this implementation using the porous implant, instead of the solid implant. Following the generation of the porous stem in LatticeWorks, it was merged with the neck region. The assembled implant was meshed using TetGen algorithm49,50. However, to mesh the solid section of the implant, hollowed gyroid voxels needed to be recognised by the meshing algorithm, otherwise it would automatically fill them up. To this end, the individual continuous holes were introduced to the algorithm by an inner point. However, due to resolution limitations, the mapped gyroid surfaces were not continuous, and there were groups of them throughout the stem region. To address this, continuous groups of gyroid surfaces were sorted based on their volumes. The largest regions, with a volume threshold of \(500\,{{\rm{mm}}}^{3}\) were selected, and any remaining sections or tiny gyroid surfaces were removed. With introducing an inner point of the maintained gyroid surfaces, the new implant model was meshed, and the mesh data was converted to Abaqus input parameters. With the two FE models of the implanted femur, one with a fully solid implant, and the other with the new porous design, the remodelling algorithm was applied to the surrounding bone part.

With the new implant design, the stress shielding effect was evaluated through bone mass in different element groups, through the method discussed in Section “Bone remodelling in solid implant”. The new implant design was assessed through comparing the results with the case of a femur with a fully solid implant.

Prototype printing of functionally graded porous implant

The resulting optimised FG porous implant design was manufactured with the Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) method, using aluminium, by LPE company (Laser Prototypes Europe Ltd., UK), using EOS M290 printer. DMLS is a very efficient sort of additive manufacturing procedure that uses a layer-by-layer manufacturing technique to produce any complex design. The main benefits of this technique are its adaptability to different materials and shapes, its vast potential for producing intricate 3D parts61.

A high-resolution stereolithography (STL) model of the designed implant was generated for 3D printing. The printing parameters are summarised in Table 4, in which for different printing directions, laser power and speed are specified.

Data availability

All relevant data and figures supporting the main conclusions of the document are available on request. Please refer to M.V. at mahtab.vafaeefar@universityofgalway.ie.

Code availability

The codes generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository under an MIT license (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14906052).

References

Mirzaali, M. J. & Zadpoor, A. A. Orthopedic meta-implants. APL Bioeng. 8, 010901 (2024).

Naghavi, S. A. et al. Stress shielding and bone resorption of press-fit polyether–ether–ketone (PEEK) hip prosthesis: a Sawbone model study. Polymers 14, 4600 (2022).

Wang, Y., Arabnejad, S., Tanzer, M. & Pasini, D. Hip implant design with three-dimensional porous architecture of optimized graded density. J. Mech. Des. 140, 111406–111419 (2018).

Arabnejad, S., Johnston, B., Tanzer, M. & Pasini, D. Fully porous 3D printed titanium femoral stem to reduce stress-shielding following total hip arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 1774–1783 (2017).

Naghavi, S. A. et al. A novel hybrid design and modelling of a customised graded Ti-6Al-4V porous hip implant to reduce stress-shielding: an experimental and numerical analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1–20 (2023).

Avval, P. T., Samiezadeh, S., Clav Klika, V. & Bougherara, H. Investigating stress shielding spanned by biomimetic polymer-composite vs. metallic hip stem: a computational study using mechano-biochemical model. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 41, 56–67 (2014).

Sabatini, A. L. & Goswami, T. Hip implants VII: finite element analysis and optimization of cross-sections. Mater. Des. 29, 1438–1446 (2008).

Ceddia, M. & Trentadue, B. Evaluation of rotational stability and stress shielding of a stem optimized for hip replacements—a finite element study. Prosthesis 5, 678–693 (2023).

Gross, S. & Abel, E. W. A finite element analysis of hollow stemmed hip prostheses as a means of reducing stress shielding of the femur. J. Biomech. 34, 995–1003 (2001).

Van Rietbergen, B. & Huiskes, R. Load transfer and stress shielding of the hydroxyapatite-ABG hip: a study of stem length and proximal fixation. J. Arthroplast. 16, 55–63 (2001).

Sas, A. et al. Effect of anatomical variability on stress-shielding induced by short calcar-guided stems: automated finite element analysis of 90 femora. J. Orthop. Res. 37, 681–688 (2019).

Bougherara, H., Bureau, M., Campbell, M., Vadean, A. & Yahia, L. Design of a biomimetic polymer-composite hip prosthesis. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 82A, 27–40 (2007).

Yavari, S. A. et al. Relationship between unit cell type and porosity and the fatigue behavior of selective laser melted meta-biomaterials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 43, 91–100 (2015).

Sun, C. et al. Stress-dependent design and optimization methodology of gradient porous implant and application in femoral stem. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 0, 1–12 (2022).

Arabnejad Khanoki, S. & Pasini, D. Multiscale design and multiobjective optimization of orthopedic hip implants with functionally graded cellular material. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 031004 (2012).

Kolken, H. M. A. et al. Additively manufactured space-filling meta-implants. Acta Biomater. 125, 345–357 (2021).

Heinl, P., Müller, L., Körner, C., Singer, R. F. & Müller, F. A. Cellular Ti–6Al–4V structures with interconnected macro porosity for bone implants fabricated by selective electron beam melting. Acta Biomater. 4, 1536–1544 (2008).

Lv, J. et al. Enhanced angiogenesis and osteogenesis in critical bone defects by the controlled release of BMP-2 and VEGF: implantation of electron beam melting-fabricated porous Ti6Al4V scaffolds incorporating growth factor-doped fibrin glue. Biomed. Mater. 10, 035013 (2015).

Gok, M. G. Creation and finite-element analysis of multi-lattice structure design in hip stem implant to reduce the stress-shielding effect. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 236, 429–439 (2022).

Burton, H. E. et al. The design of additively manufactured lattices to increase the functionality of medical implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 94, 901–908 (2019).

He, Y., Burkhalter, D., Durocher, D. & Gilbert, J. M. Solid-lattice hip prosthesis design: applying topology and lattice optimization to reduce stress shielding from hip implants. 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1115/dmd2018-6804 (2018).

Pobloth, A. M. et al. Mechanobiologically optimized 3D titanium-mesh scaffolds enhance bone regeneration in critical segmental defects in sheep. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaam8828 (2018).

Perier-Metz, C., Duda, G. N. & Checa, S. A mechanobiological computer optimization framework to design scaffolds to enhance bone regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 980727 (2022).

Davoodi, E. et al. Additively manufactured gradient porous Ti−6Al−4V hip replacement implants embedded with cell-laden gelatin methacryloyl hydrogels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 22110–22123 (2021).

Kladovasilakis, N., Tsongas, K. & Tzetzis, D. Finite element analysis of orthopedic hip implant with functionally graded bioinspired lattice structures. Biomimetics 5, 44 (2020).

Seharing, A., Hadi Azman, A. & Abdullah, S. Finite element analysis of gradient lattice structure patterns for bone implant design. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 11, 535–545 (2020).

Garner, E., Kolken, H. M. A., Wang, C. C. L., Zadpoor, A. A. & Wu, J. Compatibility in microstructural optimization for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 26, 65–75 (2019).

Mostafa, K. G., Momesso, G. A., Li, X., Nobes, D. S. & Qureshi, A. J. Dual graded lattice structures: generation framework and mechanical properties characterization. Polymers 13, 1528 (2021).

Vafaeefar, M., Moerman, K. M., Kavousi, M. & Vaughan, T. J. A morphological, topological and mechanical investigation of gyroid, spinodoid and dual-lattice algorithms as structural models of trabecular bone. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 138, 105584 (2023).

Vafaeefar, M., Moerman, K. M. & Vaughan, T. J. Experimental and computational analysis of energy absorption characteristics of three biomimetic lattice structures under compression. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 151, 106328 (2024).

Zeng, S. et al. Design and performance prediction of selective laser melted porous structure for femoral stem. Mater. Today Commun. 34, 104987 (2023).

Vafaeefar, M., Moerman, K. M. & Vaughan, T. J. LatticeWorks: an open-source MATLAB toolbox for nonuniform, gradient and multi-morphology lattice generation, and analysis. Mater. Des. 250, 113564 (2025).

Walczak, M. & Szala, M. Effect of shot peening on the surface properties, corrosion and wear performance of 17-4PH steel produced by DMLS additive manufacturing. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 21, 1–20 (2021).

Zimmer Biomet. Arcos ® One-piece Femoral Revision System (2016).

Motomura, G. et al. Effects of porous tantalum on periprosthetic bone remodeling around metaphyseal filling femoral stem: a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled study. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–9 (2022).

Tan, N. & van Arkel, R. J. Topology optimisation for compliant hip implant design and reduced strain shielding. Materials 14, 7184 (2021).

Mehboob, H., Ahmad, F., Tarlochan, F., Mehboob, A. & Chang, S. H. A comprehensive analysis of bio-inspired design of femoral stem on primary and secondary stabilities using mechanoregulatory algorithm. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 19, 2213–2226 (2020).

Bartolomeu, F., Costa, M. M., Alves, N., Miranda, G. & Silva, F. S. Additive manufacturing of NiTi-Ti6Al4V multi-material cellular structures targeting orthopedic implants. Opt. Lasers Eng. 134, 106208 (2020).

Amanatullah, D. F. et al. Revision total hip arthroplasty after removal of a fractured well-fixed extensively porouscoated femoral component using a trephine. Bone Jt. J. 97-B, 1192–1196 (2015).

Masri, B. A., Mitchell, P. A. & Duncan, C. P. Removal of solidly fixed implants during revision hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 13, 18–27 (2005).

Müller, P. et al. Development of a density-based topology optimization of homogenized lattice structures for individualized hip endoprostheses and validation using micro-FE. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–14 (2024).

Behrens, B. A., Nolte, I., Wefstaedt, P., Stukenborg-Colsman, C. & Bouguecha, A. Numerical investigations on the strain-adaptive bone remodelling in the periprosthetic femur: Influence of the boundary conditions. Biomed. Eng. Online 8, 1–9 (2009).

Bandyopadhyay, A., Mitra, I., Goodman, S. B., Kumar, M. & Bose, S. Improving biocompatibility for next generation of metallic implants. Prog. Mater. Sci. 133, 101053 (2023).

Sidambe, A. T. & Oh, J. K. Biocompatibility of advanced manufactured titanium implants—a review. Materials 7, 8168–8188 (2014).

Manam, N. S. et al. Study of corrosion in biocompatible metals for implants: a review. J. Alloy. Compd. 701, 698–715 (2017).

Vafaeefar, M. & Katoozian, H. Finite Element-based Design, Shape and Structural Rigidity Optimization of Hip Prosthesis (Amirkabir University of Technology, 2018).

Mathai, B. & Gupta, S. The influence of loading configurations on numerical evaluation of failure mechanisms in an uncemented femoral prosthesis. Int. J. Numer. Method Biomed. Eng. 36, 1–16 (2020).

Mathai, B., Dhara, S. & Gupta, S. Orthotropic bone remodelling around uncemented femoral implant: a comparison with isotropic formulation. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 20, 1115–1134 (2021).

Si, H. TetGen, a delaunay-based quality tetrahedral mesh generator. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 41, 36 (2015).

Si, H. TetGen—a quality tetrahedral mesh generator and three-dimensional delaunay triangulator, User’s Manual, Version 1.4 (2006).

Quinn, C., Kopp, A. & Vaughan, T. J. A coupled computational framework for bone fracture healing and long-term remodelling: investigating the role of internal fixation on bone fractures. Int. J. Numer. Method Biomed. Eng. 38, e3609 (2022).

Huiskes, R. et al. Adaptive bone-remodeling theory applied to prosthetic-design analysis. J. Biomech. 20, 1135–1150 (1987).

Martin, R. B. Porosity and specific surface of bone. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 10, 179–222 (1984).

ABAQUS, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp, Version 6.14 (2019).

Nicholson, J. W. Titanium alloys for dental implants: a review. Prosthesis 2, 100–116 (2020).

Li, D., Liao, W., Dai, N. & Xie, Y. M. Comparison of mechanical properties and energy absorption of sheet-based and strut-based gyroid cellular structures with graded densities. Materials 12, 2183 (2019).

Gerhardt, L. C. & Boccaccini, A. R. Bioactive glass and glass-ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Materials 3, 3867–3910 (2010).

Morgan, E. F., Unnikrisnan, G. U. & Hussein, A. I. Bone mechanical properties in healthy and diseased states. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 20, 119–143 (2018).

Heller, M. O. et al. Determination of muscle loading at the hip joint for use in pre-clinical testing. J. Biomech. 38, 1155–1163 (2005).

Chashmi, M. J. et al. Design and analysis of porous functionally graded femoral prostheses with improved stress shielding. Designs 4, 1–15 (2020).

Nandy, J., Sarangi, H. & Sahoo, S. A review on direct metal laser sintering: process features and microstructure modeling. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 6, 280–316 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. 804108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by M.V. and T.V. M.V. performed all the simulations and data analysis, under the supervision of T.V. and K.M. M.V. wrote the first draft, reviewed by T.V. and K.M. T.V. contributed to both funding acquisition and project management. K.M. and C.Q. contributed to coding. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vafaeefar, M., Quinn, C., Moerman, K.M. et al. A computational optimisation study of hip implant using density mapping functionally graded biomimetic TPMS-based lattice structures. npj Metamaterials 1, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44455-025-00003-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44455-025-00003-8