Abstract

Limited evidence links short-term temperature increases to interpersonal and self-inflicted violence via physiological and behavioral pathways, especially among vulnerable communities. Here, we analyzed 14 years (1999–2012) of Medicaid claims (N = 332,293) for interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits in the United States. We compared daily hospital visits with local temperature patterns over the following six days, assessed by cause, demographics, climate region, and socioeconomic factors. We found that as heat stress rose, violence-related hospital visits also increased, especially in the first two days after higher heat stress. A 5°C increase was associated with a 1.5% [95% CI:1.1–1.9%] increase in interpersonal and a 3.7% [95% CI:1.5–5.9%] increase in self-inflicted violence visits. Though the difference across groups was not conclusive, point-estimate associations were greatest in younger individuals and ZIP Codes with higher poverty, lower educational attainment, and more non-white residents. Our results emphasize the importance of integrating mental health into heat health action plans and climate change preparedness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The impact of both warm and cold weather events on public health can be substantial, driving the need for adaptation measures against climate change1. Previous evaluations of health effects of extreme temperature have primarily concentrated on infectious diseases and physical health such as cardiorespiratory diseases2,3. Recent studies have focused on climate-related mental health outcomes in the United States, such as hospitalizations associated with depression and anxiety, deaths from assault and suicide, and alcohol and substance use4,5,6,7,8. There are plausible direct behavioral and physiological pathways for a relationship between changes in temperature and interpersonal and self-inflicted violence including elevated levels of anger5,6,9 and increased psychoactive drug use7. It has been hypothesized that higher temperatures are associated with higher levels of distress and hopelessness in younger people9,10,11. There are also plausible reasons why dry temperature and humid temperature may differently impact mental health; typically weather forecasts inform the public of dry temperatures and can influence behavior12, whereas high humid temperatures can be physiologically extremely dangerous by decreasing sweat evaporation and the ability to cool off13.

Medicaid, a critical pillar of healthcare provision in the United States, provides health coverage to more than 70 million eligible low-income adults, children, and pregnant people, as well as people with disabilities14. Compared to the general population, Medicaid enrollees are more likely to experience poverty (27.5% below the poverty line15 compared with 10.5% in the general population16), live with disabilities (35%17 compared to 19% in the general population17), and be members of racial or ethnic minority groups (61.1%15 compared to 44% in the general population18). Medicaid enrollees are particularly vulnerable due to on average persistently low incomes, limited educational attainment, higher rates of chronic illnesses, and disproportionate representation among racial and ethnic marginalized groups19. Violent victimization in the United States is twice as high in low-income households when compared to high-income equivalents20. The vulnerability among Medicaid enrollees is further compounded by barriers to accessing timely and appropriate health care, limited health literacy, and a higher prevalence of social determinants of health, such as housing instability and food insecurity19. Examining the impact of heat and other extreme weather events in a low-income population like Medicaid enrollees, therefore, is critical as the climate continues to warm.

The aim of this study was to evaluate (a) how daily temperature was associated with interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits in a low-income population, and (b) how this association varied by sex, age group, climate region, poverty, educational attainment, and race. We leveraged national daily ZIP Code-level hospital visit data obtained from Medicaid claims on interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits.

Results

Hospital visits

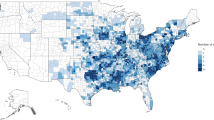

There was a total of 332,293 included hospital visits, of which there were 327,577 interpersonal violence-related hospital visits and 17,271 self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits among Medicaid enrollees in the United States during the study period (1999–2012) (Table 1). Across every cause, the age group with largest proportion of hospital visits was 25–44 years, from 35% (113,468) of interpersonal violence-related hospital visits up to 44% (7950) of self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits. Females made up most hospital visits across all causes, from 56% (187,636) of interpersonal violence to 63% (10,864) of self-inflicted violence. Interpersonal violence occurred most in the Ohio Valley (80,451; 25%) and self-inflicted violence occurred most in the Southeast (8540; 49%). Most hospital visits occurred in ZIP Codes in the highest poverty quintile, from 30% (97,695) of interpersonal violence-related hospital visits to 26% (4437) of self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits; in ZIP Codes in the least educated quintile, from 25% (82,796) of interpersonal violence-related hospital visits to 21% (3691) of self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits; and in ZIP Codes in the most non-white quintile for interpersonal violence (126,321; 39%) and in ZIP Codes in the second most non-white quintile for self-inflicted violence (5161; 30%)

The number of interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits varied by sex and age group over time (Fig. 1). There were more interpersonal violence hospital visits than self-inflicted violence hospital visits throughout the study period. The number of annual interpersonal violence-related hospital visits peaked in 2003–2004, with self-inflicted violence peaking in different years by age group (2012 for 0–24 years, 2000 for 25–44 years, 2012 for 45–64 years, 2001 for 65+ years).

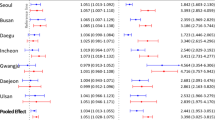

Association of temperature with total hospital visits

All results here refer to WBGTmax and cumulative lag 0-1 increases. For all violence, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 1.6% [95% CI:1.1–2.0%] cumulative (lag 0-1) increase (Fig. 2). For interpersonal violence, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 1.5% [95% CI:1.1–1.9%] cumulative increase. For self-inflicted violence, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 3.7% [95% CI:1.5–5.9%] cumulative increase.

When comparing by sex, the associations were similar for all interpersonal and self-inflicted violence. For example, for male Medicaid enrollees, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 1.3% [95% CI:0.7–2.0%] cumulative increase in interpersonal violence-related hospital visits. Among females, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 1.6% [95% CI:1.0–2.2%] cumulative increase in interpersonal violence-related hospital visits. For self-inflicted violence, though also not statistically different, associations were stronger-in-magnitude for males than females; for males, a 5 °C increase was associated with an estimated 5.4% [95% CI:2.1–8.6%] cumulative increase, and for females was associated with an estimated 2.4% [95% CI:-0.4–5.2%] cumulative increase in all-violence hospital visits.

By age group, for interpersonal and self-inflicted violence, though not statistically different, associations were mostly greatest in younger age groups. For example, for interpersonal violence, associations were greatest for those 0–24 years, with an estimated 1.6% [95% CI:0.9–2.3%] cumulative increase. For self-inflicted violence, greatest increases were in 45–64 years 0–24 years (5.0% [95% CI:1.7–8.3%]).

For all violence, the greatest associations were in Northern Rockies (1.7% [95% CI:0.1–3.6%]). For interpersonal violence, the greatest associations were also in Northern Rockies (1.8% [95% CI:-0.1–3.7%]). For self-inflicted violence, the greatest associations were in the Southwest (8.3% [95% CI:-2.2–18.9%]).

Point-estimate associations were greatest in quintiles with the highest poverty, lowest educational attainment, and highest non-white, e.g., in the highest poverty quintile, a 5 °C increase in temperature was associated with an estimated 2.0% [95% CI:1.1–2.8%] cumulative increase in for interpersonal violence-related hospital visits, with the lowest poverty quintile associated with an estimated 0.6% [95% CI:−0.9–2.0%] cumulative increase. Associations were statistically significant and strongest-in-magnitude (though with overlapping confidence intervals) in areas with both large non-white populations and high poverty, e.g., in the high non-white and high poverty stratum the cumulative increase for interpersonal violence was 1.9% [95% CI:0.9–2.9%], with other results (high non-white and low poverty, low non-white and high poverty, low non-white and low poverty) all crossing the null.

Secondary analyses

Results of cumulative associations between temperature exposure from the day of up to 6 days before (0–6 days) and cause-specific hospital visits are found in Supplementary Fig. 1. Overall, the conclusions were the same as in the main analyses. When comparing dry to humid temperatures, for the same magnitude of change of temperature (5 °C in this case), dry temperatures resulted in higher-in-magnitude point increases in the same direction (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Results of only including the pre-Medicaid expansion period of study (1999–200921) are found in Supplementary Fig. 3. Overall, the conclusions were the same as in the main analyses.

Discussion

In the United States, in the Medicaid population, a particularly vulnerable group of low-income and disabled people, during 1999–2012, an increase in temperature 0-1 days before hospital visits was linearly associated with higher hospital visit rates for interpersonal and self-inflicted violence.

Plausibility of results

Although not previously quantified, it is plausible that temperature influences interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related Medicaid hospital visits. Previous work has also associated warmer monthly temperatures with increased monthly violent death rates, including assaults and suicides5,6. Warmer temperatures and increased outdoor time correlate with a higher frequency of face-to-face interactions, contributing to a rise in arguments, confrontations, and assaults22,23, though potentially also more social support24. These effects could be compounded by the greater anger levels linked to higher temperatures from increased irritability, outbursts of temper, and more negative reactions to others25,26,27, particularly when there is access to firearms28. Reduced quality and length of sleep from higher temperatures can also result in more irritable individuals during the daytime29, particularly in low-income homes where air conditioning is less prevalent30. Increased hospital visits and consumption of alcohol and other psychoactive drugs during higher temperatures7 may also influence violent behavior to others and to oneself. That we found similar associations for dry and humid temperature is reasonable, considering the limited variability in humidity in an extratropical country such as the United States13. Consistent with our results, those with the least resources may also be more likely to be impacted the most, both in the United States and worldwide, for example from challenges in accessing indoor air conditioning10,30 and limited access to regular preventative health care9. We found that a linear association was the most appropriate model fit, consistent with previous temperature and mental health-related outcome research7,8,29.

The Medicaid population in the United States is of particular concern for violence and rising temperatures. Violence rates and substance use have been shown to be particularly high in poorer households when compared with higher income counterparts, through systemic drivers20. Co-existing conditions, such as lower access to air conditioning than the general population, are also more prevalent among lower-income populations30. Initiatives targeting socioeconomic disparities, including equitable distribution of domestic cooling provision, coupled with investments in community-based programs and adaptation strategies to mitigate the impacts of higher temperatures, can help alleviate the vulnerabilities faced by these communities and foster a safer and more resilient society overall.

Strengths and limitations

Drawing on a rich dataset of 332,293 violence-related hospital visits—including 327,577 for interpersonal violence and 17,271 for self-inflicted violence—across the United States over 14 years, alongside detailed daily temperature and relative humidity data at the ZIP Code level, this study offers, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive investigation to date into the relationship between temperature and violence-related hospital visits among the Medicaid population.

Nonetheless, our study also has limitations. First, outcome misclassification is a concern. The most severe cases of interpersonal and self-inflicted violence may have resulted in death before any hospital admission, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true association. Future research should aim to link death records with hospital data to better understand individuals’ full medical trajectories. Additionally, diagnostic misclassification in identifying violence-related hospital visits—whether interpersonal or self-inflicted—is also a possibility. Second, exposure misclassification is also likely. For example, individuals hospitalized may have been located in a ZIP Code different from their residential ZIP Code. However, it is unlikely that many individuals would be away from home for an extended period. Any such exposure misclassification is likely to be non-differential, as it would not be expected to systematically differ based on the outcome, and would likely bias results toward the null31. Third, while we accounted for many potential confounders, some residual confounding may persist. The time-stratified case-crossover design, in which individuals serve as their own controls matched on month and day of the week, controls for between-person confounding as well as for time-varying factors like long-term trends, seasonal patterns, and weekly cycles. Nonetheless, confounding by unmeasured factors that vary over shorter timeframes (e.g., sub-monthly) cannot be fully ruled out. However, such factors would need to correlate both with hospital visits and temperature, independently of the matching variables, to introduce bias—unlikely in this case. Fourth, the implications of our findings under future climate change scenarios remain uncertain. Adaptation strategies may help reduce adverse health outcomes linked to rising temperatures32. Yet, the capacity for adaptation—particularly among vulnerable populations such as Medicaid enrollees—may be limited. Fifth, eligibility criteria for Medicaid are not consistent across states. However, this is not expected to introduce bias in our study, since we used a case-crossover design (i.e., matched on person). Sixth, the most vulnerable in the United States, including undocumented migrants, are not eligible for Medicaid, and are therefore not included in our analysis. Nevertheless, these results further indicate that public health practitioners preparing for climate change should consider outcomes that have not been previously linked to temperature. Seventh, we acknowledge that isolating the effects of individual environmental exposures is challenging given the broader influence of the overall non-optimal environment.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore that hospital visits related to interpersonal and self-inflicted violence are sensitive to increases in temperature. Increasing temperatures driven by climate change may lead to a greater number of violence-related hospital visits, unless their effects are reduced through targeted social infrastructure and health system interventions. Public health targeted interventions to mitigate violent behavior in warmer weather for the poorest and most vulnerable—for example, targeted messaging on the risks of consuming psychoactive substances during warmer weather—should be a priority. Medicaid enrollees in the United States bear the heavy burden of poverty and face unique obstacles that demand attention and targeted interventions to ensure equitable healthcare access and improved outcomes.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health and Harvard School of Public Health and was classified as exempt from needing to obtain Informed Consent (Protocol IRB- AAAT5279).

Study population

We obtained Medicaid inpatient claims data from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) and assembled data from Medicaid beneficiaries, enrolled in the fee-for-service program for at least one month from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2012, and residing in the United States. For each enrollee, we extracted ZIP Code and state of residence from the Medicaid enrollee record file and the date and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for each hospital visit. In our analyses, we included both emergency and nonemergency hospital visits and all ZIP Codes in the continental United States.

Outcomes

We identified combined interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related cases, categorized as all violence, from all nine available ICD-9-CM diagnostic position codes in each admission record (Supplementary Table 1). Both inpatient and outpatient admissions were included. We subdivided violence-related records to interpersonal and self-inflicted violence. This resulted in analyses for one broad cause (all violence) and two sub-causes (interpersonal and self-inflicted violence). For each cause, an admission was counted as a case if it included at least one matching code in the nine ICD-9-CM codes, such that a single admission could be attributed to several causes.

Exposure

We derived daily maximal shaded wet bulb globe temperature (WBGTmax) – a commonly-used measure of humid-heat stress generated as in previously analyses33,34 – from the Parameter-elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model (PRISM) dataset. This dataset is produced by using a spatial regression model to interpolate sophisticated quality control measures weather observations from a wide range of in-situ monitoring networks to generate a nationwide gridded weather dataset, with full space and time coverage over our study period35. We used gridded daily maximum air temperature and minimum vapor pressure deficit estimates at a resolution of 4 km to generate area-weighted daily shaded maximum wet bulb globe temperature estimates assuming a fixed wind speed of 0.5 m/s33,34,36. We then estimated daily area-average WBGTmax at the ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA) level, a consistent geographic representation of ZIP Codes (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/zctas.html), referred to as ZIP Code throughout. In a similar way to WBGTmax, we also processed dry temperature for a secondary analysis.

Covariates

We used yearly information by ZIP Code from 1999 to 2012 on poverty (percentage in poverty), educational attainment (percentage with at least high school diploma), and race/ethnicity (percentage non-white) from the American Community Survey (ACS) (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs). We divided each covariate into quintiles of ZIP Codes (e.g., for poverty, ZIP Codes with the lowest proportion in poverty (1st quintile) to ZIP Codes with the highest proportion in poverty (5th quintile)) and assigned values to each individual visiting the hospital, based on their residential ZIP Code. The same quintile values were used for each ZIP Code throughout analyses.

Statistical analysis

We employed a time-stratified case-crossover design, a method frequently used to examine the relationship between short-term exposures and acute health events37. In this design, WBGTmax on the day of the hospital visit and relevant prior days (case period) is compared to WBGTmax on selected days when the hospital visit did not occur (control periods). This approach leverages every hospital visit in the dataset. Case and control periods were matched by year, month, and day of the week. By comparing individuals to themselves at different times when they did not make a hospital visit, we reduce confounding from factors that differ between people within the same month. Additionally, this matching strategy accounts for confounding due to long-term trends, seasonality, and day-of-week patterns.

We applied conditional logistic regression38, which accounts for the matched study design, to assess the relationship between daily temperature and hospital visit rates. To capture cumulative effects leading up to the hospital visit, we incorporated distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) terms39. Specifically, via a logit function, the log-odds of hospital visit were modeled as follows:

where \({{{\rm{Y}}}}_{{ci}}\) denotes whether subject \(i\) in matched stratum \(c\) made a hospital visit, i.e., \(c\) represents a group of a case period and its matched control periods; \({\alpha }_{c}\) the matched stratum-specific intercepts (not estimated in conditional logistic models); \(n\) the number of total lag day terms included (described below), and \(s{\left(T,{df}\right)}_{{lci}}\) the lag (\(l\))-specific natural spline terms as part of the dlnm terms for temperature. In this design, because of the incidence density sampling of control periods, the odds ratios estimate rate ratios38.

To select the optimal fit for the dlnm terms, we fit models for all violence, interpersonal violence, and self-inflicted violence attempts separately using a variety of plausible degrees of freedom (dfs) to model the lag-specific exposure – response function (df_var), as well as the function of the association over the examined lags (df_lag). A range of 2–6 for df_lag was considered, along with a range of 1 (i.e., a linear association) to 4 for df_var. The optimal values were selected by choosing the combination of df_lag and df_var with the lowest Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) values. The models with lowest AIC values for all three analyses were df_lag=6 and df_var=1, which in practice was a linear model. We initially set the total number of lag days to go from 0 to 6 (\(n\) = 7) due to the hypothesized acute association of higher temperatures with higher interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related hospital visits. Further evaluation of the models established that the estimated associations were dominated by contributions from lag days 0 and 1. Therefore, our main model includes lag 0–1 terms, with a model including lag 0–6 terms as a secondary analysis.

In addition to the main analyses investigating all hospital visits together for all violence and interpersonal and self-inflicted violence separately, we further estimated stratified associations by sex (female or male), age group (0–24 years, 25–44 years, 45–64 years, or 65+ years), and NOAA’s climate regions (Northeast, Northern Rockies, Northwest, Ohio Valley, South, Southeast, Southwest, Upper Midwest, or West)40. We additionally stratified analyses by ZIP Code-level quintiles of poverty (lowest proportion in poverty (1) to highest proportion in poverty (5)), educational attainment (highest proportion with at least high school diploma (1) to lowest proportion with at least high school diploma (5)), or non-white (lowest proportion non-white (1) to highest proportion non-white (5)). We additionally stratified models by combinations of race and poverty (high/low non-white and high/low in poverty). All stratified analyses followed the same modeling approach as described above.

We present results as cumulative percentage change in hospital visit rates per 5 °C increase on each of up to one day after the hospital visit37. Statistical analyses were conducted using the R Statistical Software, version 4.2.341, and the dlnm, package version 2.4.742.

Secondary analyses

We evaluated associations for dry temperature and for lag 0–6 exposures prior to hospital visit. This allowed us to examine a longer exposure period, while also maximizing power by not overlapping case and control periods. Since some states adopted Medicaid expansion as early as the introduction of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, in a sensitivity analysis we restricted the study period to 1999–2009.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Daily 4-km PRISM data during 1999-2012 are freely available at https://prism.oregonstate.edu/recent/. WBGTmax data are available via https://github.com/rmp15/PRISM-grids-into-FIPS-ZIP-censustract-USA. Medicaid enrollees dynamic cohort data are publicly available, upon purchase and after an application process, from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/CMS-Information-Technology/AccesstoDataApplication/index. Census data are freely available from the American Community Survey (ACS) (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs). The datasets which populate figures are available on the SPARK Lab GitHub repo at https://github.com/sparklabnyc/usa_temperature_medicaid_violence_2025.

Code availability

The R code for the statistical analysis is available on the SPARK Lab GitHub repo at https://github.com/sparklabnyc/usa_temperature_medicaid_violence_2025.

References

Romanello, M. et al. The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: the imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet 402, 2346–2394 (2023).

McMichael, A. J., Woodruff, R. E. & Hales, S. Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet 367, 859–869 (2006).

Haines, A. & Ebi, K. The imperative for climate action to protect health. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 263–273 (2019).

Yoo, E., Eum, Y., Gao, Q. & Chen, K. Effect of extreme temperatures on daily emergency room visits for mental disorders. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 39243–39256 (2021).

Burke, M. et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 723–729 (2018).

Parks, R. M. et al. Anomalously warm temperatures are associated with increased injury deaths. Nat. Med. 26, 65–70 (2020).

Parks, R. M. et al. The association between temperature and alcohol-and substance-related disorder hospital visits in New York State. Commun. Med. 3, 118 (2023).

Nori-Sarma, A. et al. Association between ambient heat and risk of emergency department visits for mental health among US adults, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 341–349 (2022).

WHO. Mental health and Climate Change: Policy Brief. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240045125 (2022).

Lawrance, E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G. & Jennings, N. The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: current evidence and implications for policy and practice. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/grantham/publications/all-publications/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-mentalhealth-and-emotional-wellbeing-current-evidence-and-implications-for-policy-and-practice php (2021).

Collins, P. Y. et al. Making cities mental health friendly for adolescents and young adults. Nature 627, 137–148 (2024).

Ebi, K. L. & Schmier, J. K. A stitch in time: improving public health early warning systems for extreme weather events. Epidemiol. Rev. 27, 115–121 (2005).

Baldwin, J. W. et al. Humidity’s role in heat-related health outcomes: a heated debate. Environ. Health Perspect. 131, 055001 (2023).

CMS. Centers for medicare & medicaid services. https://www.cms.gov/ (2017).

Langellier, B. A., Guernsey De Zapien, J., Rosales, C., Ingram, M. & Carvajal, S. C. State Medicaid expansion, community interventions, and health care disparities in a United States–Mexico border community. Am. J. Public Health. 104, e94–e100 (2014).

Bureau U. C. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html (2020).

Burns, A. 5 Key Facts About Medicaid Coverage for People with Disabilities. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/5-key-facts-about-medicaid-coverage-for-people-with-disabilities/ (2025).

Race and Ethnicity of the National Medicaid and CHIP Population in 2020. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/data-and-systems/downloads/macbis/2020-race-etncity-data-brf.pdf (2020).

Roberts, E. T., Mellor, J. M., McInerney, M. & Sabik, L. M. State variation in the characteristics of Medicare-Medicaid dual enrollees: Implications for risk adjustment. Health Serv. Res. 54, 1233–1245 (2019).

Harrell, E., Langton, L., Berzofsky, M., Couzens, L. & Smiley-McDonald, H. Household poverty and nonfatal violent victimization, 2008-2012 (US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice, 2014).

Sommers, B. D., Stone, J., Kenney, G. & Epstein, A. Coverage impacts of early Medicaid expansions under health reform: a policy brief for state and federal leaders. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24395938/

Glaeser, E. L., Sacerdote, B. & Scheinkman, J. A. Crime and social interactions. Q. J. Econ. 111, 507–548 (1996).

Rotton, J. & Cohn, E. G. Global warming and U.S. crime rates: an application of routine activity theory. Environ. Behav. 35, 802–825 (2003).

Pinker, S. The village effect: how face-to-face contact can make us healthier and happier (Vintage Canada, 2015).

Anderson, C. A. Temperature and aggression: ubiquitous effects of heat on occurrence of human violence. Psychological Bull. 106, 74–96 (1989).

Baron, R. A. & Bell, P. A. Aggression and heat: the influence of ambient temperature, negative affect, and a cooling drink on physical aggression. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 33, 245–255 (1976).

Talaei, A., Hedjazi, A., Rezaei Ardani, A., Fayyazi Bordbar, M. R. & Talaei, A. The relationship between meteorological conditions and homicide, suicide, rage, and psychiatric hospitalization. J. Forensic Sci. 59, 1397–1402 (2014).

Lyons, V. H., Gause, E. L., Spangler, K. R., Wellenius, G. A. & Jay, J. Analysis of daily ambient temperature and firearm violence in 100 US Cities. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2247207 (2022).

Minor, K., Bjerre-Nielsen, A., Jonasdottir, S. S., Lehmann, S. & Obradovich, N. Rising temperatures erode human sleep globally. One Earth 5, 534–549 (2022).

Romitti, Y., Sue Wing, I., Spangler, K. R. & Wellenius, G. A. Inequality in the availability of residential air conditioning across 115 US metropolitan areas. PNAS Nexus 1, pgac210 (2022).

Carroll, R. J., Ruppert, D., Stefanski, L. A. & Crainiceanu, C. M. Measurement error in nonlinear models: a modern perspective (CRC press, 2006).

Watts, N. et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet 397, 129–170 (2021).

Ahn, Y., Tuholske, C. & Parks, R. M. Comparing approximated heat stress measures across the United States. GeoHealth 8, e2023GH000923 (2024).

Tuholske, C. et al. Hazardous heat exposure among incarcerated people in the United States. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01293-y (2024).

PRISM Climate Group. The PRISM climate and weather system - an introduction. https://prism.oregonstate.edu/documents/PRISM_history_jun2013.pdf (2013).

Spangler, K. R., Weinberger, K. R. & Wellenius, G. A. Suitability of gridded climate datasets for use in environmental epidemiology. J. Exp. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 29, 777–789 (2019).

Maclure, M. The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am. J. Epidemiol. 133, 144–153 (1991).

Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., Lash, T. L. Modern epidemiology (Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008).

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Kenward, M. G. Distributed lag non-linear models. Stat. Med. 29, 2224–2234 (2010).

Karl, T. & Koss, W. J. Regional and national monthly, seasonal, and annual temperature weighted by area. 1895–1983 https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/10238 (1984).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Core Team, 2013)

Gasparrini, A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: the package dlnm. J. Stat. Softw. 43, 1 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by NIH grants R00 ES033742, R00 ES022631, R01 ES030616, R01 ES028805, R01 ES028033, R01 MD012769, R01 AG066793, R01 ES029950, R01 AG060232, RF1 AG071024, R21 ES028472, P30 ES009089, and P20 AG093975. Funding was also provided by the Climate Change Solutions Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to study concept and interpretation of results. R.M.P., L.F., Z.G. and D.B. collated and organized hospital visit files. R.M.P. collated and organized the temperature data from the dataset provided by C.T. R.M.P., F.D., and M.A.K. developed the statistical model, which was implemented by R.M.P. R.M.P. performed the analysis, with input from M.A.K. and F.D. D.B., C.T., I.C.T. and J.L. assisted with interpretation of results. R.M.P. and M.A.K. wrote the first draft of the paper; all authors contributed to revising and finalizing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Sustainability thanks John Ji, Jaquelyn Jahn and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Yann Benetreau. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parks, R.M., Flynn, L., Gu, Z. et al. Higher temperatures are associated with increased interpersonal and self-inflicted violence-related Medicaid hospital visits in the United States. Commun. Sustain. 1, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00001-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00001-x