Abstract

Australia is a major exporter of energy and ores, and it has ambitions to become a renewable energy superpower by providing commodities with low embedded greenhouse gas emissions. Certification of low-emissions products is crucial to attract a price premium for green products in international markets. However, certification should not impose undue regulatory burden or increase production costs. Here, we employ energy system modelling and evaluate how different policy choices affect the accuracy of certified emissions methods and the cost of hydrogen produced by grid-connected electrolysers in Australia. The results show that emissions are not always accurately accounted for under the currently proposed Australian methodologies. However, imposing geographic and relaxed temporal correlation requirements on the use of renewable energy certificates could be sufficient to ensure minimal emissions at low cost. Our study provides evidence to assist in the design of robust and practical certification schemes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trusted and internationally recognized certification of embedded emissions is critical to enable customers to differentiate low-emissions and “green”1,2 products like hydrogen and derivatives, from identical products made from fossil fuels with high emissions3,4. In the absence of a global price on carbon, such differentiation will be needed for low-emission products to compete in global markets2, and to facilitate the implementation of green industrial policies that incentivize decarbonization5. To be effective, methodological criteria for certification must capture production emissions with a high degree of accuracy while balancing the costs imposed on consumers—it is to this debate that our modelling will contribute.

In general, the certification of hydrogen produced via electrolysis is relatively straightforward when the power is sourced directly from dedicated, off-grid renewable energy (RE). Certification becomes more complex for grid-connected electrolyser systems, as the emissions from grid electricity provided by a dynamic mix of generators vary with time and location6. The challenge for certification schemes is to balance the requirement to accurately account for electricity emissions without imposing excessive regulatory burden, or driving up production costs5.

The European Union (EU) Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II) and its Delegated Regulations set out criteria for recognizing (and certifying) electricity emissions associated with grid-connected hydrogen production7,8,9. Grid electricity used for electrolyser operation/hydrogen production is defined as “fully renewable”, and hence zero emissions, if it is procured under a renewable power purchase agreement and meets three criteria: RE is supplied by renewable capacity commissioned no more than 36 months before the start of hydrogen production (additionality); RE should be generated and consumed by hydrogen production within a certain time interval (temporal correlation or simultaneity); and RE should be generated within the same interconnected bidding zone as the electrolyser (geographic correlation). Where these conditions are not met, alternative criteria may enable hydrogen to be certified as fully renewable if the grid linked to the electrolyser has over 90% renewable generation in the previous year, if its average electricity emissions intensity is below 18 gCO2e/MJ, or if the electrolyser contributes to the grid balancing8,10. Otherwise, produced hydrogen is not certified as “renewable”, and the production related emissions can be calculated by using the average emission intensity of the electricity grid7.

Previous analyses have shown the importance of additionality, geographic and temporal correlation requirements on costs and emissions of hydrogen production11,12,13,14,15,16 and have driven conversations around appropriate levels of policy stringency to enable the emergence of new green industries12. Ensuring additionality is critical to avoid scenarios where electrolysers compete for low-carbon electricity from existing capacity with other grid consumers, inadvertently increasing overall emissions11,14,17. Geographic and temporal correlation has proven to be an important but controversial policy lever11,12,16,18. A prior study of U.S. grid conditions demonstrated that allowing electricity from broad geographic regions could result in substantial consequential emissions from hydrogen production as transmission congestion could lead to different marginal generating units supplying power18. In contrast, analysis within the context of the Australian National Electricity Market (NEM) revealed that enforcing geographic correlation may be counterproductive for emissions mitigation due to larger dependence on the grid for firming local renewable supply16. Previous literature reveals a trade-off whereby strict time-matching can reduce hydrogen emissions by ensuring that grid electricity is only used when RE is generated but may also lower profitability by limiting electrolyser operation and necessitating electricity or hydrogen storage to firm supply13,14. Different conclusions have been drawn depending on the regions, scenarios and methodologies used, including support for stricter hourly temporal correlation15,18, less restrictive temporal correlation13,14,19, or a proposed transitional softening of regulations that adopts less restrictive time-matching in the near term and stricter criteria later11,12, which is adopted in the U.S. under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and in the EU under RED II to encourage grid-connected hydrogen production8,20.

The Australian government is developing a Product Guarantee of Origin (PGO) scheme to support its ambition to become “renewable energy superpower” by exporting low emission products and commodities21,22. The PGO includes methodologies to certify emissions embedded in products such as hydrogen23, and allows the surrender of renewable energy certificates (RECs) generated for each megawatt hour of renewable electricity sold to the grid. Each REC will include the commissioning date and location of the power station and when the electricity is generated with hourly resolution24,25, granting the PGO scheme the flexibility to develop rules to ensure additionality as well as geographic and temporal correlation (potential approaches are described in detail in other work10). Unlike the U.S. IRA or the EU’s RED II, the PGO scheme does not mandate additionality, nor does it enforce strict temporal or geographic correlation26. Instead, a maximum temporal correlation period of two years is imposed, allowing for relatively flexible temporal correlation26. Although the PGO scheme allows voluntary reporting of compliance with requirements of international certification frameworks23, its primary objective is to establish a system through which hydrogen producers can demonstrate the emission intensity of their hydrogen to support the future export27. However, the accuracy of the proposed emissions accounting methods has not been independently assessed for grid-connected hydrogen production, and there has been little analysis on how additional policy choices could impact the accuracy of hydrogen certification and their implications for hydrogen production costs in Australia or other countries with relatively sparse grids and vast untapped RE sources.

In this context, our study assesses the accuracy of emissions accounting under the proposed PGO certification scheme, and the implications of different policy settings on the cost and emissions intensity of grid-connected hydrogen produced in Australia. First, we develop a linear optimization model to simulate hybrid grid-connected hydrogen production systems powered by dedicated renewables and grid electricity. This hybrid framework enables evaluation of emissions accounting accuracy across multiple cost-optimal configurations, incorporating policy rules on additionality, and geographic and temporal correlation. Next, we design scenarios to evaluate the accuracy of PGO methods under the current framework and with additional policy constraints. Our modelling quantifies differences between actual and PGO-assigned emissions across varying renewable-to-electrolyser capacity ratios, allowing comparative analysis of PGO methods’ performance under diverse system configurations. Subsequently, the accuracy of PGO methods is further quantified under increasingly stringent temporal correlation and geographic correlation constraints to assess their impact on emissions accounting accuracy and resulting changes in hydrogen supply cost. Lastly, the assessment results allow us to explore how and why proposed emissions accounting frameworks under the PGO lead to inaccuracies with the aim of informing the development of accurate and efficient certification schemes.

Modelling grid-connected hydrogen production

We establish the hybrid grid-connected system powered by a mix of renewable and grid electricity, as mapped in Fig. 1. The system is operated with hourly time resolution to deliver a constant supply of hydrogen, building on previously developed optimization models28 (details in Methods section). The system can use power directly from dedicated RE capacity or can choose to buy/sell electricity from the Australian NEM with grid-use costs associated29. The hydrogen produced by the electrolyser is initially at a pressure of 30 bar and compressor 1 pressurizes hydrogen to 100 bar for direct pipeline transport to the load, while compressor 2 increases the pressure to 150 bar for storage in underground lined rock caverns if needed. We use a linear optimization model to determine the capacity of the different components including wind and solar, electrolysers, and hydrogen storage as well as their operational profiles including the system interaction with the electricity grid required to ensure lowest cost hydrogen production, calculated as on-site hydrogen supply cost (\({OHSC}\))12:

where\(\,{M}_{{H}_{2}}\) is the total hydrogen produced annually, \({CAPEX}\) is the capital expenditure including installation and equipment cost30, \(\mathrm{O\& M}\) is the operation and maintenance costs, which includes fixed and variable costs (excluding power), \({CRF}\) is the capital recovery factor, and \({C}^{e}\) is the electricity cost over the year. \({CAPEX}\) and \(O\& M\) are given by the sum of the costs associated with individual system components includes wind, PV, electrolyser and hydrogen storage facilities. The capacity of the system is constrained within the range of 10 MW to 50 MW so as not to perturb the spot price or emission intensity of the grid. These values were chosen to reflect the capacity of proposed hydrogen production projects in Australia31, and to be well below the average instantaneous electricity demand of the smallest regional grid in the NEM, Tasmania, which is approximately 1200MW32. Whenever possible, cost estimates for RE and hydrogen technology were taken from the Australia specific data in the 2023-2024 Gencost report, provided annually by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation33. Throughout, costs are converted to 2023 US dollars with an exchange rate of 0.7 US dollars per Australian dollar, also taken from Gencost33.

Embedded emissions accounting for grid-connected hydrogen

The Australian PGO scheme assigns an emission intensity to each batch of hydrogen using a modular approach designed to meet the requirements of the International Partnership for Hydrogen and Fuel Cells in the Economy’s methodology34. The emission accounting system boundary of the Australian PGO scheme spans from “well-to-delivery”25, split into two main parts: (1) the production boundary encompassing upstream and direct emissions; and (2) the post-production boundary including emissions from transport and storage of hydrogen as shown in Fig. 1. In this work, we compare the actual and certified emissions for hybrid grid-connected hydrogen production system, focusing our analysis on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with electricity imports from the grid during the production, neglecting other sources of emissions, such as from water purification or fugitive emissions of hydrogen35.

Two methods are defined by the Australian PGO scheme25 to quantify certified emissions from hydrogen production, differentiated by whether they allow the trading of RECs to account for electricity emissions (market-based method) or use a state dependent annual electricity emissions factor defined by the Australian government (location-based method)36. To calculate the electricity emissions using the location-based method (\({e}_{G{O}_{L}}\)), the net electricity bought or sold to the grid is multiplied by the annual average emissions factor for each state (\({{EF}}_{j}\))36:

where \({E}_{{out}}^{{grid}}\left(t\right)\) represents the amount of electricity bought and \({E}_{{in}}^{{grid}}(t)\) denotes the electricity sold to the grid at each hour. If the amount of \({E}_{{out}}^{{grid}}\left(t\right) < {E}_{{in}}^{{grid}}(t)\), the system could displace generation from other electricity producers and thereby contribute to the reduction of grid GHG emissions when the displaced units are fossil-fuel based.

Under the PGO market-based method, the emissions of electricity used to produce hydrogen is calculated as:

The market-based method uses two nation-wide values for electricity emission accounting: the applicable renewable power percentage (\({ARPP}\)) which gives the fraction of the electricity taken from the grid that is renewable, and the residual mix factor (\({RMF}\)), which is the annual average emission factor for the grid that excludes all the electricity generation claimed by RECs36 (or the superseded Large-Scale Generation Certificates (LGCs) through the Renewable Energy Target scheme37). Equation (3a) shows the general case in which emissions are calculated by first reducing the total electricity purchased from the grid (\({Q}_{{grid}}\)) by the ARPP and subtracting the renewable electricity consumption claimed by the eligible RECs or LGCs (total eligible RECs or LGCs: \({Q}_{{RECs}}\))38. Each REC or LGC claims one MWh of renewable generation; thus, \({Q}_{\text{RECs}}\times 1000\) gives the total renewable electricity claimed in kWh. The remaining residual electricity mix is then multiplied by the RMF to determine the emissions. Equation (3b) shows how we apply the PGO market-based method in our model over time interval \({t}_{1}\) to \({t}_{2}\). We assume each MWh of RE sold to the grid generates one REC such that, \({Q}_{{RECs}}={E}_{{in}}^{{grid}}\left(t\right)/1000\), which can be surrendered to cover emissions from using grid electricity. If more eligible RECs are surrendered to estimate electricity emissions than the total required to reach zero emissions, \({e}_{G{O}_{M}}\) is equal to zero36. Here, we assume that excess RECs will be traded to other facilities, enabling them to claim reductions in their electricity emissions under the PGO market-based method36. Consequently, one unit of eligible RECs can represent an emissions reduction on the grid of \({Q}_{{RECs}}\times {RMF}=0.81{\rm{t}}{{\rm{CO}}}_{2}e\) in the market-base method. The residual mix factors for consumption of electricity and applicable renewable power percentage are given in Supplementary Table 7.

We leverage our model to assign time and state dependent emission factors to net grid electricity consumption in each time step, enabling us to calculate modelled electricity emissions. Average emissions factors (AEFs) are computed by averaging emissions from electricity generated across each of the five states, and marginal emissions factors (MEFs) represent the emissions of the ‘marginal’ generator which would be dispatched to meet any additional electricity demand. The MEF-based and AEF-based calculation methods keep track of the electricity emissions (\({e}_{{MEF}}\) and \({e}_{{AEF}}\)) from buying and selling electricity to the grid from time \({t}_{1}\) to \({t}_{2}\) and are defined as

where the MEFs and AEFs of the grid in Australian states, \(j\), connected to the NEM at each time, \(t\), are represented as \({{MEF}}_{j}(t)\) and \({{AEF}}_{j}(t)\) respectively.

MEFs best represent the actual electricity emissions caused by the additional demand on the grid from our system39,40,41, as such changes are not met proportionally by all generators across the grid but rather by specific marginal generators whose emission intensity drives the resulting variation in emissions40. MEFs can also estimate the grid emissions avoided by displacing electricity from the marginal generator with RE sold into the grid (generating RECs in the process). Comparing the emissions calculated using the PGO methods described previously with the MEF-based method allows us to quantify how well the proposed certification methodology captures the actual emissions.

We assume that emission values can be below zero for the location-based, AEF, and MEF methods, representing cases where more RE is sold to the grid than is purchased, contributing to a reduction in grid GHG emissions by the displacement of fossil fuel generators. For the market-based method, below zero values quantify the emissions represented by excess RECs generated by the system that could be sold to offset emissions by other grid users.

The emission intensities of hydrogen are defined as EI_Market and EI_L for the values calculated by PGO market-based and location-based methods, respectively, and EI_MEF and EI_AEF for the MEF-based method and AEF-based method, respectively. The emissions offset by excess RECs produced by the system per unit of hydrogen are defined as EI_RECs.

Modelling policy settings

Policy settings can be incorporated into the model by introducing additional constraints. Additionality is ensured by restricting the system to access RE and RECs from dedicated capacity installed at the same time as the electrolyser14. Limiting the purchasing of RECs to a specific RE system allows us to accurately measure both certified and actual emissions, and also reflects the rapid deployment of new capacity to meet the growing demand for RECs in Australia42. The Australian NEM is a wholesale electricity market encompassing five states (Queensland (QLD), New South Wales (NSW), South Australia (SA), Victoria (VIC), and Tasmania (TAS)), each operating as a distinct bidding zone. Interconnectors between these states represent potential points of congestion. Thus, geographic correlation can be imposed by requiring the dedicated RE capacity to be in the same state as the electrolyser10. Temporal correlation requires that the total electricity sold to the grid must be larger than or equal to the total purchased electricity within the time interval13:

where \(\gamma\) indicates the length of the time interval required (total hour number in each time interval), and \({t}_{s}\) marks the beginning of the temporal correlation interval, which falls within the set of time steps \(\theta\) tailored to meet the specified time interval. In this work, \(\gamma\) ranges from one hour to one year (8760 h).

Scenario design for assessing emissions accounting accuracy

We model several scenarios to test how accurate PGO methods are under the current framework, and how they perform when different policy constraints are added as shown in Fig. 2. In all scenarios, OHSC is minimized using a linear optimization model. The capacities of wind \({C}^{{wind}}\), PV \({C}^{{PV}}\), and electrolyser \({C}^{{el}}\) are optimized (labelled as “Opt”) in all scenarios except for Scaling renewables (Fig. 2d), where these capacities are held fixed (labelled as “Fixed”). In scenarios (a–e) the electrolyser is co-located and directly connected to the renewable generators.

a–f Show the different scenarios considered. The orange arrows indicate electricity flows and their directions. Across scenarios (a–f), the capacities of wind \({{\boldsymbol{C}}}^{{\boldsymbol{wind}}}\), PV \({{\boldsymbol{C}}}^{{\boldsymbol{PV}}}\) and the electrolyser \({{\boldsymbol{C}}}^{{\boldsymbol{el}}}\) are optimized (labelled as “Opt”), with the exception of scenario (d), in which these capacities are prescribed (labelled as “Fixed”) rather than determined by optimization. Subsequent processes including compression, storage, and transport, are optimized consistently across all scenarios, with the capacity of hydrogen storage optimized in each case.

The off-grid scenario (Fig. 2a) features no grid connection while scenarios b-f optimize system interaction with the grid under different constraints. The “Flexible” scenario (Fig. 2b) models a grid-connected system that can buy and sell electricity without any restrictions on generating emissions. The “Emissions avoided” scenario (Fig. 2c) constrains the “actual” emissions intensity of hydrogen is to be less than zero (i.e., “EI_MEF ≤ 0”). This is not meant to model a realistic policy setting, but to understand what a system optimised for zero-emissions at lowest cost looks like. Figure 2a–c are used as the reference cases for comparison with the following scenarios.

In the “Scaling renewables” scenarios (Fig. 2d), electrolyser capacity is fixed and the combined capacity of wind and solar PV is scaled as a multiple of the electrolyser capacity, referred to as the RE factor. The RE factor is defined as the ratio between RE generators (sum of wind and solar) and electrolyser capacity. For each location, the largest RE factor is set to be 1.5 times greater than the RE factor for the optimised off-grid system. By adjusting the RE factor from 0 to its maximum value, we explore the variation in the emission intensities of hydrogen using different accounting methods (see Fig. 3).

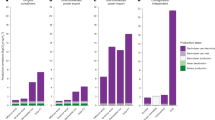

a–e Emission intensities of hydrogen under various RE factors, defined as the ratio between the capacity of the RE generators and the electrolyser deployed in systems located in each of the five states of the NEM, calculated using three different methods for electricity emissions. Actual emissions are tracked using time and state dependent marginal emission factors applied to net grid electricity consumption (EI_MEF, orange curve). Certified emissions are calculated using the PGO market-based (EI_Market, blue curve) and location-based (EI_L, green curve) methods. Negative emissions intensity values indicate that more renewable electricity is sold to the grid than is bought per unit hydrogen produced, resulting in a reduction of grid emissions (for location and MEF methods). When the system generates more RECs than needed to ensure that EI_Market = 036, the electricity emissions can be reduced by excess RECs for each MWh hydrogen produced (EI_RECs, green bars). The energy content of hydrogen is taken to be the higher heating value (39.4 kWh/kgH250) throughout the manuscript.

The “Time-matching” scenario (Fig. 2e) is designed to explore the impact of temporal correlation (Fig. 4), where additionality and geographic correlation are met and certified market-based emissions are limited below zero (i.e., “EI_Market≤0”), with the time-matching condition defined in Eq. (6) applied over different intervals (hourly - which is equivalent to only allowing the selling of electricity to the grid labelled “Sell only”, daily, monthly, yearly).

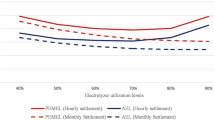

Total OHSC (white dots), average yearly actual emission intensities (EI_MEF, yellow triangles) and certified emission intensities of hydrogen (EI_Market, red triangles) calculated using the PGO market-based method for optimized system configurations in five states under “Time-matching” scenarios as described in Fig. 2e. The “Off-grid”, “Flexible” and “Emissions avoided” reference scenarios (labelled as (Ref)), as described in Fig. 2a–c, are included for comparison. The emission intensity is given in kgCO2e/kgH2 to allow comparison with existing certification schemes. Bars show the contribution of the different system components to the OHSC: grid electricity cost (sum of the total expenditure and profit from buying and selling electricity to and from the grid, which can be negative), capital expenditure (CAPEX) for hydrogen storage, and CAPEX and operation and maintenance costs (OM) of electrolyser, PV and wind generators.

Figure 2f shows the “Cross-state” scenario, where yearly temporal correlation and additionality are met but the electrolyser and the dedicated RE generators are located in different states and interact only through grid-connection. The RE is sold to its local grid, generating RECs and offsetting actual emissions in that state, while the electrolyser buys electricity from its local grid, generating actual emissions and using the RECs generated by the RE to offset emissions (details are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 2). This scenario is used to investigate the impact of geographic correlation (Fig. 5).

a OHSC and (b) emission intensity of hydrogen produced by a grid-connected electrolyser located in Newcastle NSW, with RECs sourced from grid-connected RE capacity located in the same or different states, as indicated along the x-axis. Systems are optimized under the constraint of yearly temporal correlation and are compared to off-grid (reference scenario in Fig. 2a, labelled as (Ref)) and fully-grid connected systems in NSW. The green line indicates the estimated cost of purchasing RECs from a third party to offset emissions for the fully on-grid case, assuming REC costs of 14-42USD42. Note that the OHSC for a system with RE located in NSW connected to the electrolyser through the grid is slightly higher than that calculated previously (see red dot in Fig. 5a and NSW of Fig. 4) for a system with direct connection between co-located RE and electrolyser in NSW (red dot) due to increased transmission use of system fees. The emission intensity of hydrogen is calculated by MEF-based method (yellow triangles) and for the PGO market-based (red triangles).

Accuracy of certified emission intensity of hydrogen in Scaling renewables scenario

First, we assess the accuracy of the PGO methodologies under the “Scaling renewables” scenario (Fig. 2d). We calculate the emission intensity of hydrogen produced by hybrid systems in the five states for systems with a constant electrolyser size (equal to that of an optimized off-grid system) and varying levels of dedicated RE capacity: an RE factor of 0 is a fully grid-reliant system, while an RE factor of 2 indicates the system has RE capacity (wind+PV) two times larger than the electrolyser (Fig. 3). The dedicated RE capacity is co-located, ensuring geographic correlation, and the systems can interact with the grid flexibly without temporal correlation. Actual emissions are shown as EI_MEF (orange curve), while certified emissions are represented by EI_Market calculated by the market-based (blue curve) and EI_L using location-based (green curve) methods. The emissions offset by excess RECs produced by the system each MWh hydrogen is shown as EI_RECs (green bar).

Actual hydrogen emissions intensities (EI_MEF, orange curve) vary from 0.6-0.8 tCO2e/MWhH2 for fully grid-reliant systems in QLD, NSW and VIC (Fig. 3a–c), with relatively high emissions intensities, and fall to near zero for RE factors of around 2-2.5, indicating that RE systems need to be overbuilt to avoid grid imports and minimize emissions. Systems in these states can also displace substantial emissions by selling to the grid for high RE factors with EI_MEF < -0.24 tCO2e/MWhH2 (EI_MEF, orange curves in Fig. 3a–c). For TAS, which has very high renewable penetration, fully grid-reliant systems produce hydrogen with much lower emissions intensities of ~ 0.26 tCO2e/MWhH2 (EI_MEF, orange curve in Fig. 3d), falling to zero for systems with RE factors of around 1. However, systems are limited in the quantity of emissions they can displace as RE factors increase. In SA, hydrogen from fully grid-reliant systems is still ~0.6 tCO2e/MWhH2 (EI_MEF, orange curve in Fig. 3e) despite the dominance of renewables in the state, as the marginal generator will be a fossil fuel technology 45% of the time (red and yellow bars in Supplementary Fig. 8).

The key result from this analysis is that actual emissions intensities of hydrogen, represented by EI_MEF (orange curve) are not always well represent by certified emission intensities, calculated using the PGO market-based (blue curve for EI_Market and green bar for EI_RECs) and location-based (EI_L, green curve) methods. The PGO location-based method overestimates actual emissions in QLD, NSW, and VIC by up to 63% (0.43 tCO2e/MWhH2) in VIC (green curve for EI_L and orange curve for EI_MEF in Fig. 3c) and underestimates actual emissions for TAS and SA by up to 42% (0.24 tCO2e/MWhH2) in SA (green curve for EI_L and orange curve for EI_MEF in Fig. 3e) for systems powered by the grid (RE Factor = 0). This is because MEFs for states dominated by coal (QLD, VIC, NSW) tend to be lower than the AEFs used in the location-based method, as over 49% of the time the marginal generator will be a lower emissions technology like gas or renewables (yellow, blue, purple and green bars in Supplementary Fig. 8). Conversely, states with high renewable penetration such as SA and TAS tend to have MEFs higher than AEFs as marginal demand may be met by importing electricity provided by coal (33% of the time in SA and 18% of the time in TAS, see red bars in Supplementary Fig. 8).

In general, comparison between the emission intensities calculated using the AEF-based and PGO location-based methods, given in Supplementary Fig. 10, show relatively good agreement for all systems investigated, as they both use state-based AEFs, albeit at different temporal resolutions (1 hour for EI_AEF, 1 year for EI_L)43.

The emissions intensity calculated using the PGO market-based method (blue line, Fig. 3a–e) is the same for all systems due to the use of nation-wide emissions and renewable energy factors in the calculation (see Eq. (3a)). The PGO market-based method overestimates the emissions for fully grid reliant systems (RE Factor = 0) and overestimates the electricity emissions avoided by self-sufficient systems (at the maximum RE Factor) by generating excess RECs. The largest discrepancies are observed for TAS (comparing blue and orange lines in Fig. 3d, and orange curve in Supplementary Fig. 11a), with emissions intensities overestimated by up to 274% (0.7 tCO2e/MWhH2), and EI_RECs overestimated by up to 245% (0.4 tCO2e/MWhH2). Deviations reduce as less grid-electricity is bought and sold.

We attribute this to the fact that the proportion of RE on the state grids can be much higher (93% and 71% in 2023 for TAS and SA, respectively, see Supplementary Table 6) than the national-wide renewable power percentage (ARPP) of 18.72%. Likewise, the emissions intensity used in the calculation (RMF) is calculated by adjusting the average emission factor of the grid at the national level (including the NEM, South-West Interconnected System, and the Darwin, Katherine Interconnected System44) by excluding all RE that has generated RECs or LGCs (Supplementary equation (27)). This neglects the energy mix of the state grids on the NEM, resulting in larger discrepancies for states with higher RE penetration.

Accuracy of certified emission intensity of hydrogen in time-matching scenarios

Next, we optimize the system configuration and operation of hybrid systems to achieve lowest cost hydrogen production under constraints defined in the “Time-matching” scenarios (Fig. 2e). We compare emissions certified by the PGO-market based method and actual emissions, as well as the cost of hydrogen produced under different scenarios: Off-grid (reference scenario in Fig. 2a), “Flexible” systems with no constraints (reference scenario in Fig. 2b), “Emissions avoided” systems with actual emissions limited below zero (reference scenario in Fig. 2c), and systems with different temporal correlation requirements (“Sell only”, daily, monthly and yearly), while ensuring geographic correlation, as above (Fig. 4).

In all states, off-grid production systems achieve zero emissions but result in the highest OHSC (the reference scenario as defined in Fig. 2a). Grid connection lowers OHSC (white dot points in Fig. 4), with the lowest costs occurring for “Flexible” scenarios with no additional constraints (the reference scenario as defined in Fig. 2b), but leads to different emissions outcomes depending on the state and specific scenario constraints.

In general, we find that the market-based method (EI_Market, red triangles in Fig. 4) does not always accurately capture the actual emissions (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in Fig. 4) resulting from buying grid electricity and selling RE to the grid, overestimating emissions when buying large amounts of grid electricity, and overestimating emissions offsets by generating excess RECs when large amounts of RE are sold. Critically, there are scenarios where emissions certified to be below zero result in substantial actual emissions, with intensities of up to 3.6 kgCO2e/kgH2 (EI_MEF, yellow triangle in “Yearly” for NSW in Fig. 4) for the yearly temporal correlation constraint in NSW. In the following, we explore how and when these discrepancies arise, and the implications of different policy settings on the optimal system configuration, and the resulting cost and emissions. There are two distinct trends for optimized system configurations and emission intensity of hydrogen: one that holds for TAS, NSW and VIC, and one that holds for SA and QLD.

Due to the interplay between spot prices and the quality of the RE resources, the cheapest way to produce electrolytic hydrogen in TAS, NSW and VIC is to minimize capital investment and source large amounts of power from the grid under the “Flexible” scenarios. For TAS and VIC, relatively low grid electricity prices (see Supplementary Table 6) make dedicated RE uncompetitive. While NSW has the highest yearly average electricity price in the NEM (Supplementary Table 6), the local RE resources in Newcastle are less abundant (quantified by the RE capacity factor, Supplementary Table 5), leading to higher RE costs. When unconstrained by temporal correlation in the “Flexible” scenario, the system builds less dedicated RE capacity in TAS and NSW compared to the “Off-grid” scenario, and none in VIC (see CAPEX + OM of wind and PV, purple and blue bars in TAS, NSW and VIC of Fig. 4), and invests in smaller hydrogen storage and electrolyser capacity. Critically, relying on grid power in the lowest cost flexible scenarios can result in very high hydrogen emission intensities, with EI_MEF = ~ 25 kgCO2e/kgH2 for VIC and NSW (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in “Flexible” in VIC and NSW of Fig. 4), comparable to hydrogen made from coal gasification45. Once again, we see that the PGO market-based method, overestimates the certified emissions intensity, particularly for TAS and VIC (see red triangles for EI_Market and yellow triangles for EI_MEF in TAS, NSW and VIC of Fig. 4).

Once yearly temporal correlation is imposed in TAS, NSW and VIC, the system is forced to build RE capacity, the OHSC increases, and the actual emission intensity falls to below zero in TAS and slightly above zero in NSW and VIC (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in TAS, NSW and VIC of Fig. 4). As the temporal correlation requirements become more restrictive, shifting from yearly to hourly time matching, the system increases the capacity of the electrolyser and storage, and the configuration progressively resembles an off-grid setup. Consequently, OHSC increases by 30%-38% (OHSC, white dots in “Yearly” and “Sell only” in TAS, NSW and VIC of Fig. 4). Once again, the PGO market-based emission calculation overestimates potential emissions offsets by RECs, with the effect increasing when the system sells larger amounts of electricity to the grid (compare red triangles for EI_Market and yellow triangles for EI_MEF in TAS, NSW and VIC of Fig. 4).

The trend is different for SA and QLD. All systems have actual emissions intensities close to or below zero (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in SA and QLD of Fig. 4), and the “Flexible” and yearly “Time-matching” scenarios all result in nearly identical system configurations, with similar and lowest cost OHSC (white dots in SA and QLD of Fig. 4). The cost reduction in these two scenarios compared to the reference off-grid system is mainly attributable to the systems’ ability to profit from selling surplus electricity to the grid (see Grid electricity cost, light red bars in SA and QLD of Fig. 4), driven by favourable local RE resources and higher regional electricity prices (Supplementary Tables 5, 6). The system oversizes the cheapest RE capacity and sells large amounts of electricity to subsidize the cost of hydrogen production (see light red bars for Grid electricity cost, and purple and blue bars for CAPEX + OM of wind and PV in SA and QLD of Fig. 4). As the temporal correlation requirements become more restrictive, shifting from yearly to hourly time matching, the restrictions on importing electricity from the grid results in the establishment of configurations similar to the reference off-grid system with PV and larger storage components. The systems are prevented from subsidizing the cost of hydrogen by selling electricity, increasing the OHSC by 78% in QLD, and 52% in SA (OHSC, white dots in “Yearly” and “Sell only” in QLD and SA of Fig. 4).

One way to assess the efficacy of temporal correlation as a policy is to compare with systems optimized to minimize cost while constraining EI_MEF\(\le\)0. Figure 4 shows that such systems (“Emissions avoided”, the reference scenario in Fig. 2c) are most similar to those optimized under yearly temporal correlation, suggesting it is an efficient policy measure to keep emissions low, at low cost. However, it is important to note that while yearly temporal correlation is sufficient to ensure that the certified emissions intensities under the PGO market-based method are all below zero (EI_Market, red triangles in Fig. 4), actual emissions intensities are still 1.9 kgCO2e/kgH2 for the VIC case and 3.6 kgCO2e/kgH2 for the NSW case (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in VIC and NSW of Fig. 4).

Accuracy of certified emission intensity of hydrogen in Cross-state scenarios

So far, all hybrid systems have been constrained by geographic correlation, with a direct connection between co-located RE and hydrogen electrolysers. Next, we relax that constraint and compare scenarios in which the electrolyser and the dedicated RE generators are located in different states and interact only through grid-connection (“Cross-state” scenario Fig. 2f). We focus on an electrolyser located in Newcastle (NSW), which is the site of the announced Hunter Valley Hydrogen Hub, slated to include a 50 MW electrolyser powered by grid-connected RE through purchase and retirement of RECs46. In Fig. 5, we compare systems under the constraint of yearly temporal correlation (Eq. (6)) with dedicated RE located in the same or different states, with a fully grid-powered system (without RE generators and no additional constraints) and an off-grid system. When grid connection is not permitted and a geographic correlation constraint is imposed, off-grid production systems achieve zero emissions but incur highest OHSC (reference “Off-grid” scenario in Fig. 2a). Similar to Fig. 4, the OHSC decreases with grid connection, and certified emission intensities remain below zero under the yearly temporal correlation constraint (EI_Market, red triangles in Fig. 5b), while actual emissions vary considerably depending on the state in which RE generators are located.

With the geographic correlation constraint, the actual emissions intensity for a system with RE located in NSW connected to the electrolyser through the grid is 3.7 kgCO2e/kgH2 (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in NSW(Newcastle) of Fig. 5). Without the constraint of geographic correlation, the actual emissions (EI_MEF, yellow triangles in Fig. 5b) vary widely with the location of the RE, as the emissions displaced by selling RE will depend on the makeup of its local grid and are not necessarily equal to emissions generated using electricity in NSW. In the worst case, hydrogen certified as zero emissions by the PGO market-based method can have actual emission intensities of 21 kgCO2e/kgH2 (yellow triangle for EI_MEF and red triangle for EI_Market in TAS (Burnie) of Fig. 5b), similar to that of hydrogen produced via coal gasification45, as high emissions intensity electricity consumed in NSW is being offset by displacing relatively low emissions intensity electricity in TAS. This highlights that temporal correlation alone is insufficient to ensure that emissions from grid-connected hydrogen remain low.

Notably, the OHSC can be reduced by as much as 21% when the RE is located in QLD due to the superior RE resources and high electricity costs (OHSC, blue bar in QLD (Gladstone) of Fig. 5a), as the net cost of grid electricity is determined by buying and selling electricity to and from two different grids and depends on the spot prices in both states. In this case, producers have a cost incentive to site the RE in a location that will result in the lowest emissions, but this will not generally be true in all cases as production cost and emissions outcomes will be determined by the interplay of cost and emissions factors in different states.

In all scenarios so far, we assume a strict additionality requirement: that dedicated RE is deployed concurrently to the electrolyser. The PGO scheme does not currently require such strict additionality: RECs can be generated by eligible RE systems built before the electrolyser, as long as they began generating renewable electricity after 1997, and do not have to be surrendered as part of Renewable Energy Target37,38,47. The fully grid-powered electrolyser system in Fig. 5 approximates this case, buying electricity from the NSW grid at the spot price and generating the corresponding emissions according to the state-based MEF. Under this scenario, the additional cost for RECs to offset the certified emissions under the market-based method would increase the OHSC by 16-44% assuming RECs costs of 14-42USD42 (OHSC, blue bar in Fully-grid (Newcastle) of Fig. 5), while estimating the actual emissions would require the time and state dependent MEF for each REC.

Conclusions

Developing “green” global hydrogen markets requires trusted certification that is stringent enough to reflect the actual emissions of certified hydrogen. There is a degree of optimization required to design certification stringency such that it minimizes the cost of hydrogen production, but not at the expense of masking true emissions.

We employ an energy system model to quantify emissions and costs of hybrid grid-connected hydrogen production systems located across the Australian National Electricity Market and find that both emissions accounting methods in the Product Guarantee of Origin scheme could lead to notable discrepancies compared to the actual emissions. The discrepancy arises in the Product Guarantee of Origin location-based method because actual emissions from additional electricity demand are driven by the marginal generator rather than the average grid emissions intensity, and interconnection among the five states in the National Electricity Market makes marginal emission factors of one regional grid subject to influence from another with a different generation mix through inter-regional trade. The Product Guarantee of Origin market-based method uses national-level factors relating to renewable energy penetration and residual emissions (i.e., applicable renewable power percentage and residual mix factor), overlooking variations in energy mix across state grids44. While overestimation is consistent with the principle of conservativeness recommended for embedded emissions accounting5, and hence is not necessarily a design flaw, underestimation of embedded emissions contravenes the conservativeness principle and undermines the scheme’s emissions-reduction goals.

We study the accuracy of emission certification under different policy settings and find that geographic correlation coupled with less stringent temporal correlation is an effective and efficient policy measure to ensure near-zero emissions systems at low cost and low regulatory overhead. However, we show that it is possible for hydrogen that is certified as zero-emissions under the Product Guarantee of Origin market-based method to generate actual emissions under these conditions, which is consistent with a previous finding based on a system-level analysis of the National Electricity Market16.

However, the optimum temporal correlation interval to ensure that actual emissions remain below zero for all states still needs to be determined and will likely depend on the interplay between regional electricity prices, local renewable resources and renewable energy penetration in the local state grid. As such, this will be sensitive to location and could change over time. Further work is needed to better understand the importance of temporal correlation impacts on the cost and emissions of grid-connected hydrogen and should include a larger number of potential sites to assess the broader cost-effectiveness of policy settings. In this work, we assume that the incremental electricity demand modelled is small so as not to alter the marginal generators and therefore does not affect spot prices or marginal emission factors. In addition, our model optimizes the system configuration over a single year with perfect foresight, and we do not investigate how natural variation in weather patterns and the dynamic changes in grid spot price and emissions over the years would affect optimal sizing or operation. Future work should consider the impact of large-scale hydrogen production on grid dispatch and account for uncertainties in weather and grid conditions during the production process. Nevertheless, our findings provide timely evidence to aid the design of the Australian Product Guarantee of Origin scheme, and while grounded in the National Electricity Market’s context, the case study of five states with diverse grid characteristics offers insights for other national systems to design robust and practical certification schemes.

Methods

Model description

We establish a linear optimization model to quantify the cost and emission intensity of hydrogen produced by hybrid grid-connected hydrogen production systems in Australia. In the following, we briefly describe the relevant features of the model. A full description is provided in the Supplementary Note 1, along with details of all technical and economic parameters. The model is operated with hourly time resolution over a one-year period and is constrained to deliver a constant supply of hydrogen (180 kg/hour) to industrial end-users throughout the year. This reflects the likely requirements of large, continuous industrial processes in refineries, ammonia plants, liquefaction facilities, and other industrial operations27. The optimization model minimizes the on-site hydrogen supply cost (OHSC), defined in Eq. (1), which consists of capital expenditure (\({CAPEX}\)) (annualized using the capital recovery factor \({CRF}\)), operation and maintenance costs (\(\mathrm{O\& M}\)) and annual electricity cost (\({C}^{e}\)). The \({CAPEX}\) and \(\mathrm{O\& M}\) are given by the sum of the costs associated with individual system components:

where\(\,{C}^{k}\) represents the installed capacity of a component, \({I}^{k}\) is investment needed per unit installed capacity, \({{FOM}}^{k}\) and \({{VOM}}^{k}\) are the fixed and variable operation and maintenance cost of component \(k\), where \(K\) is the component set which includes wind, PV, electrolyser and \({H}_{2}\) storage facilities. The \({CRF}\) can be calculated according to the plant lifetime \(n\) and the interest rate \(i\) as:

The electricity cost \({C}^{e}\) over one year includes costs associated with buying electricity from the grid and negative “costs” from selling electricity to the grid in each time \(t\) and is given by,

where \({E}_{{out}}^{{grid}}\left(t\right)\) and \({E}_{{in}}^{{grid}}(t)\) are the amount of electricity bought or sold each hour, and \({P}_{j}(t)\) is the electricity spot price in state \(j\) at each time \(t\). In addition, the system pays an additional transmission use of system fee \({TS}\) when importing electricity48,49. The electricity into the electrolyser and the hydrogen storage level are both limited by the capacity of electrolyser \({C}^{{el}}\), and hydrogen storage \({C}^{S}\), respectively:

Constraints are placed on the size of the RE capacity to avoid unrealistic results. For example, in states with high electricity prices, the system may grossly oversize the local RE generation capacity to profit from selling electricity to the grid, in essence creating a second business to subsidize hydrogen production. This phenomenon does not align with practical constraints as the RE generation capacity is usually limited by the available land, project budget and the risk of investment48. Thus, we also constrain the \({CAPEX}\) of the on-grid system such that it does not exceed the \({CAPEX}\) of the optimized off-grid system without grid-connection.

The model simulates the operation of the production system by ensuring the equilibrium of electricity and hydrogen flows, as described in the following.

Electricity flow balance

The production system is powered by electricity which can be sourced from local RE generation or imported from the grid. At each time \(t\), local wind generation (\({E}_{{out}}^{{wind}}(t)\)) and solar generation (\({E}_{{out}}^{{PV}}\left(t\right)\)) are produced based on the local weather profile. RE can either be used to (i) power the electrolyser for hydrogen production (\({E}_{{in}}^{{el}}\left(t\right)\)) and the compressor for hydrogen transmission into either the pipeline (\({E}_{{in}}^{{comp}1}\left(t\right)\)) or storage facilities (\({E}_{{in}}^{{comp}2}\left(t\right)\)), (ii) exported to the grid (\({E}_{{in}}^{{grid}}(t)\)), or (iii) curtailed (\({E}_{{in}}^{C}(t)\)). If the local RE is insufficient to support the system’s operation, the system can choose to import electricity from the grid (\({E}_{{out}}^{{grid}}(t)\)). The decision of electricity dispatching is made by solving the flow balance equation given by

Hydrogen flow balance

The system converts electricity into hydrogen through electrolysis and then either pumps the hydrogen into the pipeline for direct transportation to the hydrogen load or stores it in the hydrogen storage equipment, which serves as a reserve for the load, storing hydrogen to supply when production by the electrolyser is insufficient to meet the demand. At each time \(t\), hydrogen is produced by the electrolyser with efficiency, \(\eta =70 \%\)30, as following:

where \({HHV}\) = 39.4 kWh/kgH250 is the higher heating value of hydrogen and \({H}_{{out}}^{{el}}(t)\) represents the hydrogen produced by electrolyser. This hydrogen is subsequently allocated by the system to either compressor 1 (\({H}_{{out}}^{{comp}1}\left(t\right)\)), which pumps it into the pipeline for direct transportation to end-users at a pressure of 100 bar, or to compressor 2 (\({H}_{{out}}^{{comp}2}\left(t\right)\)), where it is pressurized to 150 bar and then stored in the hydrogen storage:

The hydrogen load in each time \(t\) (\({H}_{{in}}^{{Load}}\left(t\right)=180{kg}\)) is met either by hydrogen flow directly from the electrolyser via pipeline and/or hydrogen from storage (\({H}_{{out}}^{S}(t)\)) according to:

Wind and solar generation

Local wind and PV generation at each time \(t\) depends on the optimized capacity of the generators. To enable the optimization, we define reference capacities for the onshore wind farm (\({C}_{{Ref}}^{{wind}}=320{\rm{MW}}\)) and PV field (\({C}_{{Ref}}^{{PV}}=1{\rm{MW}}\)), and calculate the hourly reference generation (\({E}_{\mathrm{Re}{f}_{{out}}}^{{wind}}\) and \({E}_{\mathrm{Re}{f}_{{out}}}^{{PV}}(t)\)) using NREL’s PySAM engine51 and historical local weather data from MERRA-2 dataset52. The actual generation is then calculated through linearly scaling the reference output based on the ratio of actual capacity to reference capacity:

where \({E}_{{out}}^{{wind}}(t)\) and \({E}_{{out}}^{{PV}}(t)\) represent the actual hourly generation of the wind farm and the PV field, respectively. \({C}^{{wind}}\) and \({C}^{{PV}}\) indicate the capacity for the wind farm and PV field, respectively.

Grid

We introduce the grid node to simulate the interaction between production system and the grid. The system can choose to import and export electricity from the grid node (the state in which it is located), defined by time and location dependent historical electricity prices and emissions factors (average and marginal), described in detail in section Modelling the Australian National Electricity Market below. Detailed information on the NEM data is provided in Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Fig. 7.

Compressor 1 and Compressor 2

The electricity consumption of compressor 1, which pressurizes hydrogen produced by the electrolyser for pipeline injection, and compressor 2, which pressurises hydrogen for storage is given by

where \({\mu }_{{out}}^{{comp}1}\) and \({\mu }_{{out}}^{{comp}2}\) are the electricity consumption for each unit of hydrogen compressed by compressor 1 and compressor 2, respectively.

Hydrogen storage

The hydrogen storage level at each time \(t\) (\({H}^{{S\_level}}(t)\)) is updated according to:

where \({H}_{{out}}^{S}(t)\) represents the hydrogen sent out by the hydrogen storage to meet the load and \({H}^{{S\_level\_}0}\) is the initial level of hydrogen storage as we assume the system has been in trial operation for a period. The hydrogen storage level in the last time point should be equal to the initial level to ensure that all the hydrogen sent out is produced within the modelled year.

Modelling the Australian National Electricity Market

The NEM is made up of networks in five regions (roughly corresponding to the states) interconnected by a transmission network, including Queensland (QLD), New South Wales (NSW), South Australia (SA), Victoria (VIC) and Tasmania (TAS). Electricity is traded within and between states by the central dispatch engine run by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO)53. The spot prices of electricity in each state are determined by the highest bid accepted by the AEMO from a generator to fulfill demand for each 5-minute interval. The historical data on spot prices and emission factors used in our study is from 2023 sourced from AEMO at five-minute intervals, and subsequently averaged to one-hour timesteps29, as described in the Supplementary Table 6. Here, a representative historical time series is shown in Fig. 6a, depicting hourly AEFs and MEFs for Queensland grid profile on 18 Feb 2023. The associated hourly spot prices for the same time and location are shown in Fig. 6b, along with a bar chart indicating how frequently each type of generator (coal, gas, renewables) becomes the marginal generator over the five-minute intervals in each hourly dataset.

a Shows marginal emissions factors (MEFs) (purple curve) and average emissions factors (AEFs) (green curve) in relation to the electricity generation of the grid (bars) in each hour. b Shows the frequency of each type of fuel generator becoming marginal (bars), along with electricity prices (blue curve) for each hour.

The graphs show that AEFs reflect the generation mix of the grid, with high AEFs during the early morning and evening peaks due to the reliance on fossil fuel-generated electricity, and lower AEFs during midday when the proportion of RE generation on the grid increases. In contrast, the MEF values are determined by the emissions intensity of the marginal generators and so can change rapidly across the day. The two emission factors can vary widely over some time periods. Further discussion about the comparison between MEFs and AEFs is given in Supplementary Note 5.

Yearly average AEFs and MEFs for each state are given in Supplementary Table 6, and the energy generation mix as quantified by the percentage contribution of different generators to annual generation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Local grids in QLD, VIC and NSW are dominated by coal power (~60%)54, with RE meeting a major portion of the remaining demand, (also given in Supplementary Table 6 as 28%, 42%, 31% respectively) leading to average AEFs of 0.69, 0.73, and 0.63 kgCO2e/kWh in 2023. In contrast, 71% of SA electricity was provided by renewables in 2023, with the rest coming from gas power and imports from other states54, resulting in a much lower average AEF of 0.23 kgCO2e/kWh. The average AEF in TAS was lower still, at 0.12 kgCO2e/kWh, as over 90% of electricity generation was renewable, mostly from hydro (~70%), followed by wind (~20%).

The average MEF values vary much less between the states, from 0.4-0.52 kgCO2e/kWh, with the exception of TAS, which has a much lower average MEF of 0.19 kgCO2e/kWh. This is because the marginal generators that respond most frequently to increased demand in each state are similar: coal (33-50% of the time), followed by hydro (25-32%), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Since TAS has abundant hydro, it is the marginal generator over 75% of the time. The high frequency of hydro as the marginal generator leads to MEFs that are lower than AEF in heavily coal-reliant states (QLD, NSW, VIC), while the fossil fuel technologies are marginal generators 45% of the time in SA, resulting in larger MEF than AEF.

Data availability

The input data for the various scenarios evaluated along with the outputs are available at https://zenodo.org/records/1738880755.

Code availability

The model source code used for this study is available at https://zenodo.org/records/1738880755.

References

White, L. V. et al. Towards emissions certification systems for international trade in hydrogen: the policy challenge of defining boundaries for emissions accounting. Energy 215, 119139 (2021).

Köveker, T. et al. Green premiums are a challenge and an opportunity for climate policy design. Nat. Clim. Chang 13, 592–595 (2023).

Longden, T., Beck, F. J., Jotzo, F., Andrews, R. & Prasad, M. ‘Clean’ hydrogen? – Comparing the emissions and costs of fossil fuel versus renewable electricity based hydrogen. Appl. Energy 306, 118145 (2022).

Vallejo, V., Nguyen, Q. & Ravikumar, A. P. Geospatial variation in carbon accounting of hydrogen production and implications for the US Inflation Reduction Act. Nat Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-024-01653-0 (2024).

White, L. V., Aisbett, E., Pearce, O. & Cheng, W. Principles for embedded emissions accounting to support trade-related climate policy. Clim. Policy 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2024.2356803 (2024).

Engstam, L., Janke, L., Sundberg, C. & Nordberg, Å Grid-supported electrolytic hydrogen production: cost and climate impact using dynamic emission factors. Energy Convers. Manag. 293, 117458 (2023).

European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/1185 of 10 February 2023 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing a Minimum Threshold for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Savings of Recycled Carbon Fuels and by Specifying a Methodology for Assessing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Savings from Renewable Liquid and Gaseous Transport Fuels of Non-Biological Origin and from Recycled Carbon Fuels. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/1185/oj (2023).

European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/1184 of 10 February 2023 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing a Union Methodology Setting out Detailed Rules for the Production of Renewable Liquid and Gaseous Transport Fuels of Non-Biological Origin. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/1184/oj (2023).

European Commission. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance). http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2001/oj (2024).

White, L. V., Fazeli, R., Beck, F. J., Baldwin, K. G. H. & Li, C. Implications for cost-competitiveness of misalignment in hydrogen certification: a case study of exports from Australia to the EU. Energy Policy 204, 114661 (2025).

Giovanniello, M. A., Cybulsky, A. N., Schittekatte, T. & Mallapragada, D. S. The influence of additionality and time-matching requirements on the emissions from grid-connected hydrogen production. Nat Energy 9, 197–207 (2024).

Brandt, J. et al. Cost and competitiveness of green hydrogen and the effects of the European Union regulatory framework. Nat Energy 9, 703–713 (2024).

Ruhnau, O. & Schiele, J. Flexible green hydrogen: The effect of relaxing simultaneity requirements on project design, economics, and power sector emissions. Energy Policy 182, 113763 (2023).

Schlund, D. & Theile, P. Simultaneity of green energy and hydrogen production: Analysing the dispatch of a grid-connected electrolyser. Energy Policy 166, 113008 (2022).

Zeyen, E., Riepin, I. & Brown, T. Temporal regulation of renewable supply for electrolytic hydrogen. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024034 (2024).

Palmer, G., Dargaville, R., Wang, C., Hamilton, S. & Hoadley, A. Considering the greenness of renewable hydrogen production in Australia. J. Clean. Product. 516, 145776 (2025).

Alex Barnes. How Proper Measurement of Low Carbon Hydrogen’s Carbon Intensity Can Reduce Regulatory Risk (The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford, 2024).

Ricks, W., Xu, Q. & Jenkins, J. D. Minimizing emissions from grid-based hydrogen production in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 014025 (2023).

Majanne, Y., Vilhonen, V., Repo, S. & Vilkko, M. Impacts of EU regulation on green hydrogen production and storage capacity design and operation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 58, 745–750 (2024).

Internal Revenue Service Treasury. Section 45 V Credit for Production of Clean Hydrogen; Section 48(a)(15) Election To Treat Clean Hydrogen Production Facilities as Energy Property. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-12-26/pdf/2023-28359.pdf (2023).

DCCEEW. National Hydrogen Strategy 2024. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-hydrogen-strategy-2024.pdf (2024).

The Treasury. Establishing a ‘Front Door’ for Major, Transformational Projects - Consultation Paper. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-09/c2024-571335-consultation-paper.pdf (2024).

DCCEEW. Future Made in Australia (Guarantee of Origin) Act 2024. https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2024A00121/asmade/2024-12-10/text/original/pdf (2024).

DCCEEW. Renewable Electricity Guarantee of Origin Approach Paper. https://storage.googleapis.com/files-au-climate/climate-au/p/prj291cc9979281a4ffc59d8/public_assets/Renewable%20Electricity%20Guarantee%20of%20Origin%20Approach%20Paper.pdf (2023).

DCCEEW. Guarantee of Origin - Emissions Accounting Approach Paper. https://storage.googleapis.com/files-au-climate/climate-au/p/prj291cc9979281a4ffc59d8/public_assets/Guarantee%20of%20Origin%20-%20Emissions%20Accounting%20Approach%20paper.pdf (2023).

Parliament of Australia. FUTURE MADE IN AUSTRALIA (GUARANTEE OF ORIGIN) BILL 2024 - EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/legislation/ems/r7245_ems_f6ba1951-c855-47e4-af3d-9bbae044ea6b/upload_pdf/JC014047.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22legislation/ems/r7245_ems_f6ba1951-c855-47e4-af3d-9bbae044ea6b%22 (2024).

Bracci, J. M., Sherwin, E. D., Boness, N. L. & Brandt, A. R. A cost comparison of various hourly-reliable and net-zero hydrogen production pathways in the United States. Nat Commun 14, 7391 (2023).

Mojiri, A., Wang, Y., Rahbari, A., Pye, J. & Coventry, J. Current and future cost of large-scale green hydrogen generation. SSRN Scholarly Paper at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4477925 (2023).

AEMO. NEMweb market data. https://aemo.com.au/energy-systems/electricity/national-electricity-market-nem/data-nem/market-data-nemweb (2024).

AEMO. 2023 Costs and Technical Parameter Review AEMO. https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/stakeholder_consultation/consultations/nem-consultations/2023/2024-forecasting-assumptions-update-consultation-page/aurecon---2023-cost-and-technical-parameters-review.pdf (2023).

Rees S., Grubnik P., Easton L., & Feitz A. Australian Hydrogen Projects Dataset (June 2024). http://pid.geoscience.gov.au/dataset/ga/146425 (2024).

Australian Energy Regulator. Annual electricity consumption - NEM. https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/charts/annual-electricity-consumption-nem (2024).

Graham, P., Hayward, J., & Foster J. GenCost 2023-24: Final Report. https://www.csiro.au/-/media/Energy/GenCost/GenCost2023-24Final_20240522.pdf (2024).

International Partnership for Hydrogen and Fuel Cells in the Economy. Methodology for Determining the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Associated with the Production of Hydrogen. https://www.iphe.net/_files/ugd/45185a_8f9608847cbe46c88c319a75bb85f436.pdf (2023).

Frazer-Nash Consultancy. Fugitive Hydrogen Emissions in a Future Hydrogen Economy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/624ec79cd3bf7f600d4055d1/fugitive-hydrogen-emissions-future-hydrogen-economy.pdf (2022).

National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme. National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Measurement) Determination 2008. https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2008L02309/latest/text (2025).

Clean Energy Regulator. Renewable Energy Target. https://cer.gov.au/schemes/renewable-energy-target (2025).

DCCEEW. Renewable Energy (Electricity) Regulations 2001. https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2001B00053/2024-10-14/2024-10-14/text/original/pdf (2024).

Ryan, N. A., Johnson, J. X. & Keoleian, G. A. Comparative assessment of models and methods to calculate grid electricity emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 8937–8953 (2016).

Hawkes, A. D. Estimating marginal CO2 emissions rates for national electricity systems. Energy Policy 38, 5977–5987 (2010).

Elenes, A. G. N., Williams, E., Hittinger, E. & Goteti, N. S. How well do emission factors approximate emission changes from electricity system models? Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14701–14712 (2022).

Clean Energy Regulator. Large-scale generation certificate (L. G. C.) reported spot and forward prices. https://cer.gov.au/markets/reports-and-data/quarterly-carbon-market-reports/quarterly-carbon-market-report-december-quarter-2024/large-scale-generation-certificates-lgcs (2024).

Schäfer, M., Cerdas, F. & Herrmann, C. Towards standardized grid emission factors: methodological insights and best practices. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2776–2786 (2024).

DCCEEW. Australian National Greenhouse Accounts Factors. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-greenhouse-account-factors-2024.pdf (2024).

Eric, L. et al. Comparison of Commercial, State-of-the-Art, Fossil-Based Hydrogen Production Technologies. https://doi.org/10.2172/1862910 (2022).

CSIRO. Hunter Valley Hydrogen Hub (Updated Project Description). HyResource https://research.csiro.au/hyresource/hunter-valley-hydrogen-hub/ (2024).

DCCEEW. Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000. https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2004A00767/2025-01-01/2025-01-01/text/original/pdf.

Salmon, N. & Bañares-Alcántara, R. Impact of grid connectivity on cost and location of green ammonia production: Australia as a case study. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 6655–6671 (2021).

TasNetworks. Prescribed Transmission Service Prices for 2024-25. https://www.tasnetworks.com.au/config/getattachment/96b170ef-8d44-43b9-97bf-7ba6b2304bd0/2024-25-prescribed-transmission-service-prices.pdf (2024).

Harrison, K. W., Remick, R., Martin, G. D. & Hoskin, A. Hydrogen Production: Fundamentals and Case Study Summaries. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy10osti/47302.pdf (2010).

National Renewable Energy Laboratory. PySAM: Python Wrapper for the System Advisor Model (Version 6.0.0). https://github.com/NREL/pysam (2024).

Rienecker, M. M. et al. MERRA: NASA’s modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications. J. Clim. 24, 3624–3648 (2011).

Australian Energy Regulator. State of the Energy Market 2021. https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/State%20of%20the%20energy%20market%202021%20-%20Chapter%202%20-%20National%20Electricity%20Market_0.pdf (2021).

The Superpower Institute. Open Electricity. https://explore.openelectricity.org.au/energy/nem/?range=7d&interval=30m&view=discrete-time&group=Detailed (2025).

Chengzhe, L. Assessing emission certification schemes for grid-connected hydrogen in Australia. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17388807 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Heavy Industry Low-carbon Transition Cooperative Research Centre (HILT CRC) whose activities are funded by industry, research and government partners along with the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centre Program. C.L. acknowledges support from the ANU Centre for Energy Systems.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chengzhe Li: conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. Lee V. White: conceptualisation, investigation, writing-review and editing. Reza Fazeli: conceptualisation, investigation, writing-review and editing. Anna Skobeleva: methodology, writing-review and editing, Michael Thomas: methodology, writing-review and editing, Shuang Wang: methodology, writing-review and editing. Fiona J Beck: conceptualisation, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Sustainability thanks Jonathan Brandt and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., White, L.V., Fazeli, R. et al. Assessing emission certification schemes for grid-connected hydrogen in Australia. Commun. Sustain. 1, 19 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00019-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00019-1