Abstract

For next-generation wireless networks, both the upper mid-band and terahertz spectra are gaining global attention. This article provides an in-depth analysis of recent regulatory rulings and spectrum preferences issued by international standard bodies. We highlight promising frequency bands earmarked for 6G and beyond, and offer examples that illuminate the passive service protections and spectrum feasibility for coexistence between terrestrial and non-terrestrial wireless networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As wireless communication technologies evolve toward 6G and beyond, previously underexplored frequency bands have emerged as promising candidates to enable ultra-high-speed data transmission, ultra-low latency, and next-generation networking paradigms. Given the increasing demand for higher bandwidth and emerging applications such as direct-to-device (D2D) satellite service, other non-terrestrial networks (NTNs), terahertz backhaul, chip-to-chip communications, and wireless fiber replacement, it becomes apparent that understanding spectrum availability and regulatory constraints is critical for product planning by the industry, as well as network build-out strategies for service providers. This article provides a comprehensive survey of global spectrum allocation activities through analyses of current regulatory frameworks, international policies, as well as suitability for network operators in the future. Here, we examine allocations and restrictions set by major regulatory bodies, including the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and national telecommunications agencies across Europe, Asia, North America, and emerging markets.

New spectrum released in each generation

Since the founding of the cellular telephone industry, new spectrum has been released to meet the growing demands of wireless services and applications. The global community identifies frequency bands that are studied and discussed at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC) every four years. In the 1970s and 1980s, the first-generation wireless systems around the world were deployed in the 800 and 900 MHz bands. In the second generation (2G) of cellphone technology, the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) evolved out of the first pan-European spectrum and technology standardization effort, where countries throughout Europe agreed on a common cellphone spectrum allocation across country borders and on a single GSM air interface. Through ITU, governments around the world agreed upon spectrum allocations for the budding cellphone industry at both 800–900 MHz as well as at 1900 MHz. In the U.S. and Japan, numerous types of digital standards proliferated, including IS-136 (TDMA), IS-95 (CDMA), and Japan Digital Cellular (JDC)1.

In the 2000s, when the third-generation cellular networks began to roll out with high-speed digital cellular networks, another new frequency band at 2.1 GHz in the U.S. was approved for major standards, such as UMTS and CDMA2000, which provided a much-improved link throughput as packet data was introduced. Other countries began authorizing new spectrum, best suited to dovetail with their own incumbent users, to foster the remarkable growth of cellular telephones. In the 2010s, the fourth-generation (4G) long-term evolution (LTE) technology was adopted as the single, unifying technology standard embraced by global carriers and manufacturers, leading to incredible market scale and cost savings to consumers. The ubiquity of wireless and the advanced capabilities of LTE required many more spectrum bands to unleash the multimedia and Internet Protocol (IP)-based connectivity. The new frequency bands that support time-division duplex and frequency-division duplex, as well as concatenation of bands, including 700 MHz, 1700 MHz, 2300 MHz, 2600 MHz, and 3.5 GHz, respectively2.

At the dawn of the 5G era, the FCC led the world in opening up the millimeter wave (mmWave) spectrum above 24 GHz3,4, with spectrum auctions taking place in 2019 for the greatest amount of wireless spectrum ever offered to the industry5. Despite the common misconception that 5G mmWave has not been successful, wireless carriers in India and the USA have reported big rollouts and massive profits using mmWave for fixed wireless access (FWA) and in urban centers and entertainment venues for new customer additions in the 5G mmWave era6,7,8.

In March 2019, the FCC opened up spectrum bands above 95 GHz (Spectrum Horizons, ET Docket 18-21) for unlicensed uses in 95 GHz–3 THz9. Today, the Qualcomm Snapdragon X75 modem supports over 25 different cellphone radio bands from around 400 MHz to 39 GHz10. The growth in authorized spectrum bands and total bandwidths enabled by these frequencies is listed in Table 1.

Interest in the upper mid-band spectrum

The upper mid-band spectrum, also known as FR3 (7.125 GHz–24.25 GHz) in 3GPP, has garnered significant global interest11. Agencies and institutes around the world, such as the ITU, the U.S. National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), FCC, European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), and Ofcom in the U.K., have been considering several frequency bands within this spectrum for 5G-Advanced (3GPP Release 18) and 6G (3GPP Release 19) applications12,13. The primary interest lies in the so-called “golden band” in 7.125–24.25 GHz due to its balance of coverage and system capacity while supporting wider bandwidths than previous sub-6 GHz spectrum allocations. Historically, the lower frequencies, e.g., below 6 GHz, have been extremely desirable due to their better propagation through buildings and foliage, although the higher millimeter wave bands offer much wider allocations of spectrum as well as much greater channel gain due to compact yet very directional beamforming antennas that overcome the omnidirectional free space path loss that naturally occurs at higher frequencies14,15,16.

Another service trend in wireless networking in the upper mid-band spectrum is the integrated terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks, where satellites can connect directly to mobile devices, thereby bypassing ground infrastructure altogether17. Such D2D satellite-to-mobile links can provide coverage for areas where ground infrastructure is inaccessible or too expensive to build, such as in rural areas, mountainous areas, or the sea. This is particularly important given that oceans make up 75% of land mass on earth, and rural or mountainous locations are difficult and expensive to serve with conventional terrestrial infrastructure. Here, we provide an in-depth discussion on the new FR3 bands and other promising future spectrum allocations at the ultra-high frequency (UHF, between 300 MHz and 3 GHz) and mid-band (up to 6 GHz) in the section “Spectrum Opportunities at UHF, Mid-band, and Upper Mid-band for Mobile and Fixed Wireless”.

Issues with current global spectrum allocations in fixed, mobile, defense, and satellite services

Current spectrum allocations adopted by countries often vary widely, leading to compatibility issues and difficulties in harmonizing spectrum allocations across the world. For example, the 3.5 GHz band in the U.S. is for Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) where organizations can adopt and build private 5G networks with a shared licensing model18. However, in Europe and some countries in Asia, this band is for standard 5G cellular networks. Thus, when equipment providers, such as Ericsson or Nokia, wish to deploy their network equipment in European and U.S. markets, different hardware and firmware must be configured to meet specific regulations in respective regions. For a 5G user who travels between the U.S. and Europe, these variations in spectrum allocations cause product rollout delays and may lead to reduced coverage in certain areas due to the differences in assigned cellular bands and lagging support in devices. Some users may find their cellphones with channels that are operable in one region but not in another, which may lead to degradation in user experience.

Organization and notations

Some recent works have explored the spectrum opportunities9,19,20,21, and this article is unique in that it provides many important recent developments in the rapidly changing field of spectrum allocations, as well as particular insights into the rapidly growing adoption of satellites as part of regional and global cellphone networks. The article is organized as shown in the flowchart in Fig. 1. For the rest of this article, we first present cellular spectrum opportunities at the desired lower frequencies at UHF, mid-band, and upper mid-band in the section “Spectrum Opportunities at UHF, Mid-band, and Upper Mid-band for Mobile and Fixed Wireless”. An overview of current spectral allocations across major regulatory organizations at UHF, mid-band, and upper mid-band for D2D satellite service is presented in the section “Spectrum Allocation for D2D Satellite Applications”, followed by a review of recent experiments in the upper mid-band for conventional cellular services in the section “Future Promise of Upper Mid-band for Conventional Cellular Services”. For 5G-Advanced/6G networks, the global spectrum regulations above 100 GHz are provided in the section “Global Spectrum Regulations for 5G-Advanced/6G Above 100 GHz”. Then, a discussion on promising frequency bands above 100 GHz is presented in the section “Future Frequency Bands and Coexistence Consideration Above 100 GHz”, followed by an outlook of research directions for emerging spectrum allocations in the section “Future Research Directions for Emerging Spectrum Allocations and Coexistence”. The notations and abbreviations can be found in Table 2 on the following page.

Spectrum opportunities at UHF, mid-band, and upper mid-band for mobile and fixed wireless

Frequencies at sub-6 GHz and upper mid-band (7–24 GHz) provide opportunities for burgeoning markets in 5G-Advanced (3GPP Release 18) and future 6G (3GPP Release 19) applications due to their balance of coverage and system capacity. AT&T recently proposed to the FCC to consider moving the CBRS band out of the current allocation of 3.5–3.7 GHz, and down to 3.1–3.3 GHz in order to relocate 150 MHz of prime cellular spectrum at 3.55 GHz for the cellphone industry22. This proposal stems from an observation of a low usage of the CBRS band by the cable industry in the U.S. Similarly, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) recently proposed to re-allocate the original CBRS band at 3.5 GHz for 5G services23. The DoD proposal went further, also calling for the release of 50 MHz of new spectrum at 1.3 GHz, 70 MHz at 1.8 GHz, 75 MHz in the upper 5-GHz band, and 125 MHz in the 7-GHz band, respectively23. Among all upper mid-band candidates, 7.125–13.25 GHz is considered the most promising “golden band” due to favorable propagation and wider spectrum chunks without adjacent incumbents12,14.

The NTIA in the U.S. published an implementation plan in 2024 for the frequency band in 7.125–8.4 GHz as part of the National Spectrum Strategy, which is currently under study by federal agencies as “Strategic Objective 1.2: Ensure spectrum resources are available to support private sector innovation now and into the future”24. Meanwhile, the FCC also expanded 12.2–12.7 GHz for flexible use in terrestrial fixed links and 12.7–13.25 GHz for mobile broadband in 5G in 202325. Similarly, Europe is considering 7.125–8.4 GHz and 14.8–15.35 GHz for international mobile telecommunications (IMT) in terrestrial networks toward 6G26. Ofcom in the U.K. has been considering hybrid approaches to share the 6-GHz band between Wi-Fi and cellphone users27. A more detailed breakdown of the global allocation of the upper mid-band spectrum is given in Table 3. Another two promising bands are 18.1–18.6 GHz (for expanded satellite operations) and 37.0-37.6 GHz (for shared usage among federal and non-federal satellite and terrestrial operations), which are part of the National Spectrum Strategy currently being studied by NTIA, NASA, DoD, and FCC24.

Spectrum allocation for D2D satellite applications

D2D initiatives seek to extend connectivity to remote areas lacking traditional cellular infrastructure28. November 2022 saw the launch of the first D2D activity in the cellphone industry when Apple debuted its emergency text message services to iPhones in partnership with Globalstar29. Currently, the U.S. service provider T-Mobile has partnered with SpaceX’s Starlink satellite system to provide D2D text message delivery as well as Wireless Emergency Alerts nationwide with the aim of eliminating “mobile dead zones”30. Meanwhile, AST SpaceMobile is developing a satellite-based cellular broadband network to provide 5G coverage globally, partnering with U.S. carriers AT&T and Verizon, among others31.

D2D’s need for bandwidth

D2D initiatives face a key challenge in securing enough bandwidth to support ambitious proposals for broadband service from space. Consider AST SpaceMobile (AST), whose Block 2 BlueBird satellites are each designed to support 2500 adjustable antenna beams, with every downlink beam supporting a bandwidth over 40 MHz in the UHF and L bands, and possibly later the S band32,33. Straightforward downlink calculations illustrate why ample bandwidth is essential to AST’s broadband ambitions28. Assuming a wavelength λ = 34 cm (a satellite downlink frequency of 880 MHz in the UHF cellular band), a space-based antenna area A = 223 m2 and efficiency η = 0.7, the Block 2 phased array gain is approximately Gt = 4πηA/λ2 = 42 dBi, for a half-power beamwidth of θt = 0.028 rad, or 1.6 deg. At an altitude of 725 km34, the satellite produces a beam whose narrowest footprint has a 20.3 km diameter and 324 km2 area. Assuming a spectral efficiency of 3 bps/Hz (consistent with early testing), a 40-MHz beam could support a total downlink rate of 120 Mbps. If directed at a sparse rural area with a population density of 30 users per km2 and a conservative 50% smartphone ownership (the U.S. average in 2023 was 90%), a single beam would encompass 324 × 30 × 0.5 = 4860 smartphones in its footprint. Assuming 5% peak concurrency usage, about 240 of these phones would be active during peak demand hours, for an equal-division allocation of 500 kbps per user—far from broadband rates.

To approach scalable broadband, AST and other satellite carriers must either increase their system’s area spectral efficiency (bits/Hz/area) or expand their bandwidth. The former will be difficult due to launch vehicle and power limitations. Narrowing the antenna beamwidth, which occurs as the antenna area increases, appears impractical. Block 2 BlueBird satellites are already so large (three times larger than the array shown in Fig. 2) that only eight fit within the enormous payload fairing of Blue Origin’s New Glenn launch vehicle, the largest for which the Block 2 is manifest35. A further size increase in pursuit of higher area spectral efficiency would markedly raise launch costs, eroding the constellation’s economic viability. Similarly, the Block 2 satellites are already designed to radiate power at the limits of SCS out-of-band (OOB) emission and interference restrictions, though a recent loosening of these limits in the U.S. for Starlink may also be extended to AST, providing some additional headroom36.

Given that AST’s Block 2 satellites will already operate near the practical limits of antenna size and radiated power, expanded bandwidth appears to be the most viable path to increased D2D throughput. Another approach would be to increase the operating carrier frequency since path loss is dramatically decreased with increased frequency and fixed antenna area (see the section “Future Frequency Bands and Coexistence Consideration Above 100 GHz”); however, the tropospheric attenuation and rain attenuation would tend to offset such link budget gains at higher frequencies9,37. A similar analysis—not presented here, but yielding similar results—can be carried out for SpaceX’s D2D offering via Starlink to appreciate their need for greater bandwidth. The following subsections assess the various possible sources of D2D spectrum.

Existing mobile satellite services (MSS) spectrum

Historically, mobile satellite services (MSS) have been assigned to spectrum bands in L-band (1–2 GHz) and S-band (2–4 GHz)38, as well as slices of the Ku- and Ka-band39. One of the advantages of the existing MSS spectrum is that it is well-coordinated globally and protected from terrestrial interference. Resolutions from WRC-23 also updated the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System to strengthen the safety and reliability of MSS communications. These benefits make conventional MSS spectrum well-suited for D2D, including mission-critical applications, such as ship-to-shore alerting and connectivity recovery from natural disasters.

The primary impediment to expanded use of MSS for D2D is the lack of unencumbered bandwidth40. Even existing allocations are typically too narrow for broadband D2D; e.g., Inmarsat’s L-band Broadband Global Area Network constrains throughput to an average of 650 kbps per channel41. Against this backdrop, AST’s recent purchase of usage rights to 40 MHz of Ligado’s MSS L-band spectrum42 is a rare and impressive attainment.

Terrestrial spectrum under Supplemental Coverage from Space

In February 2024, the FCC introduced a groundbreaking regulatory framework called Supplemental Coverage from Space (SCS) in which spectrum owned by terrestrial network operators can be used for D2D. The ultimate goal of SCS is a “Single Network Future” with seamless collaboration between satellite system operators and terrestrial mobile service providers43. Under SCS, two primary approaches are being explored to enable D2D using terrestrial mobile spectrum: (1) dedicate spectrum solely for D2D service, and (2) share the same spectrum between terrestrial- and satellite-based services40. Here we discuss the benefits and challenges of both approaches.

Dedicated spectrum for D2D

In this approach, a terrestrial mobile operator designates specific spectrum blocks for exclusive use by a satellite partner. For example, T-Mobile and SpaceX use the 1910–1915 MHz and 1990–1995 MHz bands (i.e., the PCS G Block) exclusively for D2D services44. A dedicated approach simplifies interference coordination within a carrier’s own network and guarantees consistent availability for satellite services. Another advantage is the optimization of waveform and medium access protocols for D2D links, which improves link reliability and efficiency. However, a dedicated-spectrum model is inevitably spectrum-inefficient for the carrier—especially in regions where terrestrial coverage is already adequate—since, due to greater path loss, D2D has much lower spectral efficiency than the terrestrial network.

Flexible terrestrial spectrum sharing for both terrestrial and D2D services

A more flexible alternative allows the mobile spectrum to be exploited both by the incumbent wireless carriers offering standard cellular service over terrestrial networks and by satellite networks offering a D2D service to mobile customers. For Lynk Global, D2D messaging and voice are in sub-GHz cellular bands via SCS, including a 2025 FCC modification enabling commercial SCS in Guam/Northern Mariana Islands (845.1–845.3 MHz in uplink and 890.1–890.3 MHz in downlink) with partner NTT Docomo Pacific45. Appropriate technical mechanisms will be required for coexistence (e.g., time or geographic division, beamforming, and transmitted power control, among others). The primary benefit of the spectrum sharing model is spectrum (re-)utilization and reducing barriers for scaling D2D globally. However, daunting challenges exist in dealing with terrestrial-to-satellite core network latency, wide Doppler swings, and interference across a D2D satellite’s spot beam while maintaining good spectral efficiency. It may be that the resource orthogonality and expanded guard intervals required to ensure seamless handover between terrestrial and D2D coverage will inevitably lead to poor spectral efficiency in the periphery of terrestrial coverage. Existing studies, including46,47, provide quantitative analysis on co-channel interference and out-of-band leakage for both downlink and uplink in satellite networks.

Prospects of upper mid-band spectrum for D2D

The upper mid-band spectrum for potential D2D services poses both opportunities and challenges. While the spectral windows available in the upper-mid band range (shown in Table 3) have the potential to support broadband satellite services with significant capacity, the feasibility of space-based D2D in the upper mid-band is constrained by propagation characteristics. Satellite transmission links in this range suffer higher path loss for fixed antenna gains (e.g., shrinking antenna area at higher frequencies) and have poorer diffraction performance as compared to the lower frequency L-band and S-band MSS allocations, making it difficult to deliver data to handheld devices, especially on the uplink under non-line-of-sight (NLoS) scenarios. Additionally, the increased Doppler shift, which is proportional to the carrier frequency, as well as more stringent requirements on antenna beam pointing, acquisition, and tracking, also complicate mobility management and waveform design in the upper mid-band. Therefore, while technically feasible with advanced transceiver systems, antenna arrays, adaptive beamsteering, and waveform optimization, space-based D2D in the upper mid-band may be limited to favorable propagation conditions or may require hybrid architectures with local terrestrial repeaters or bi-directional beamforming from space and at the mobile device.

Worth noting is that for fixed satellite service (FSS) systems operating around Ku- and Ka-band, spectrum sharing relies heavily on spatial multiplexing through beamforming at both the satellite and user terminals, such as is employed by the Starlink Ku-band terrestrial user terminals. But handheld devices are too small to support tight device-side beamforming. Thus, their quasi-omnidirectional antennas will collect signals from large sectors of the sky. As a result, spectrum sharing through spatial multiplexing from space is unlikely in D2D applications.

Future promise of upper mid-band for conventional cellular services

As the interest in the upper mid-band spectrum grows globally (previously discussed in the section “Interest in the Upper Mid-band Spectrum”), this spectral range, which covers more than 8 GHz of bandwidth14, promises great potential in achieving a balanced tradeoff between throughput and coverage11. Only lately has the global wireless community started to develop in-depth knowledge of propagation conditions for mobile applications of this emerging spectrum, as it has traditionally been allocated for satellite, fixed point-to-point, and military applications, where the global cellular network community in 3GPP standard bodies had assumed no difference in radio propagation characteristics between the conventional cellular frequencies below 6 GHz and frequencies up through 24 GHz.

In recent channel studies at the upper mid-band, various institutions across the world have found that the channel models (such as delay spread and angular spread models) currently assumed by the 3GPP standard bodies are inadequate and require revision. In particular, researchers at NYU WIRELESS studied an indoor factory channel at 6.75 GHz and 16.95 GHz with a bandwidth of 1 GHz48. The work demonstrates a frequency-dependent behavior of root-mean-square (RMS) delay spread and RMS angular spread. Another study on penetration loss at 6.75 GHz and 16.95 GHz over ten different building materials and antenna polarizations suggests existing 3GPP material penetration models may be required for revision49. In addition, another work50 conducted in an urban outdoor setting shows that measured mean values of NLoS RMS delay spread and RMS angular spread are consistently lower in New York City compared to 3GPP model predictions using TR 38.901, which brings the knowledge for the first time to the research community.

Researchers at Seoul National University also studied the upper mid-band in an urban microcellular scenario in Seoul51. Their work corroborates the findings of NYU in that the 3GPP model for RMS delay spreads in the upper mid-band currently used by 3GPP is much larger than was observed in the streets of Seoul, South Korea. This finding is an important design consideration for the 6G standardization process, since a smaller RMS delay spread implies the physical existence of a larger coherence bandwidth in the channel that will support wider bandwidth, hence leading to more subcarriers in Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM) than at sub-6-GHz frequencies.

A set of outdoor double-directional measurements targeting the urban microcellular scenario is conducted on the campus of the University of Southern California using a vector network analyzer-based channel sounder that can sweep across 6–14 GHz52. Key findings from the measurement campaign also confirm the stronger received power as compared to theoretical predictions from the Friis path loss model due to multipath components, whereas angular spreads at the transmitter and receiver demonstrate general consistency across different frequencies.

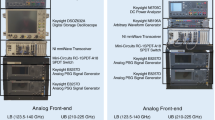

In a multi-institutional collaboration in the U.S., including NYU, the University of Notre Dame, and Florida International University (FIU), researchers developed a custom software-defined radio (SDR) platform and conducted experiments in urban outdoor settings in a wide spectral range of 6–24 GHz53. The studies, enabled by this SDR platform, allow for flexible waveform generation and reception, as well as adaptive wideband operations in the upper mid-band, thus facilitating channel sounding and interference management in various application scenarios, including the coexistence of satellite and terrestrial cellular networks.

European efforts in the upper mid-band are also gaining traction. For example, Politecnico di Milano investigated the 6.425–7.125 GHz band using a customized 5G new radio (NR) testbed for urban and factory automation scenarios54. Their work provides an evaluation of the upper mid-band’s capabilities in supporting deterministic latency and achieving reliability goals in Industry 4.0 environments while maintaining adequate coverage. Such an overview of recent efforts by research and industrial groups investigating the propagation characteristics of the upper mid-band (FR3) is presented in Table 4 on the following page.

Global spectrum regulations for 5G-advanced/6G above 100 GHz

As different countries adopt different strategies in developing 5G and future 6G networks, it is necessary to review current global spectrum regulations above 100 GHz to identify opportunities for future service expansion and coexistence in the 5G-Advanced/6G era. In this section, we present the key agenda items toward World Radiocommunication Conference 2027 (WRC-27) and offer perspectives indicated by major standard bodies, such as ITU, FCC, and ETSI.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

The ITU is an agency within the United Nations that oversees global telecommunications, information, and communication technology (ICT) policies. The ITU functions to regulate and harmonize global spectrum usage, set international standards, facilitate international coordination and cooperation, as well as promote global connectivity. ITU also organizes world radiocommunication conferences (WRCs) every four years to lay out agenda items for discussion by participants from global industry, governments, and research groups, which shape the prospects of the wireless industry. One of the agenda items in WRC-27 focuses on evaluating potential regulatory measures to protect passive services operating in frequency bands above 76 GHz (Agenda Item 1.18)55. Specifically, Agenda Item 1.18 seeks to ensure the global protection of the Earth Exploration-Satellite Service (EESS) (passive) and the Radio Astronomy Service (RAS) from unwanted emissions originating from active services. A study is being conducted under the guidance of Resolution 712 (WRC-23), which is an in-depth assessment of the interference risks posed by emerging active radio systems56. Given the increasing interest in utilizing the mmWave and sub-THz spectrum for advanced wireless communications, including 6G and beyond, the need for spectrum coexistence analysis and interference mitigation strategies is becoming more pressing.

The ITU Radiocommunication Sector (ITU-R) Working Party (WP) 7C leads discussions on remote sensing services, which include both active and passive Earth observation systems, such as the EESS. In preparation for WRC-27 Agenda Item 1.18, WP 7C has developed a draft framework for conducting spectrum sharing and compatibility studies related to EESS operations in frequency bands above 76 GHz. The framework lays the foundation for evaluating potential regulatory and technical measures necessary to protect passive sensing applications57. One of the key aspects of the current ITU-R studies conducted by the WP 7C is the assessment of unwanted emissions from active services, particularly those from high-frequency communication and sensing technologies. The reason is that with the highest frequency ranges considered in the current draft framework for radiolocation service in WRC-27 include 231.5–275 GHz and 275–700 GHz, some have already been allocated or identified for EESS, RAS, fixed and mobile services, among other applications58. Within the working party, involvement of major stakeholders such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and Amazon underscores the strategic importance of these interference risks and coexistence studies, as both organizations have vested and sometimes contradictory interests in space-based and terrestrial applications that rely on access to mmWave and THz spectra.

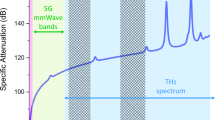

In parallel with the protection of passive services, WRC-27 will also consider the potential identification of several frequency bands for International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT). According to the ITU draft agenda55, the upcoming WRC-27 will explore the feasibility of allocating specific sub-THz bands for future mobile broadband applications, in accordance with Resolution 255 (WRC-23). The targeted bands under consideration include 102–109.5 GHz, 151.5–164 GHz, 167–174.8 GHz, 209–226 GHz, and 252–275 GHz, all of which exhibit promising characteristics for ultra-high-throughput wireless communications for potential 6G deployments56. The identification of the candidate frequencies (102–109.5 GHz, 151.5–164 GHz, 167–174.8 GHz, 209–226 GHz, and 252–275 GHz) for IMT use also raises regulatory concerns, mostly on coexistence with passive services. The overlap between proposed IMT bands and existing EESS and RAS allocations (previously demonstrated in37, also shown in Fig. 3 for portions above 170 GHz) calls for the development of advanced spectrum-sharing frameworks and interference mitigation techniques. A more in-depth analysis of some promising frequency bands within or close to these targeted bands is provided in the section “Future Frequency Bands and Coexistence Consideration Above 100 GHz”. In a most recent ITU-R Working Party 1A document (Document 1A/88-E) released in May 202559, a revised outline is proposed by Japan on spectrum utilization, channel characteristics, and applications for terrestrial active services, such as fixed, mobile, radiolocation, amateur, and Industrial, Scientific, and Medical (ISM) from 275 GHz to 1 THz. In particular, new use cases are being highlighted, which include 1) for fixed services: THz multi-hop mesh backhaul and multi-antenna spatial-multiplex links, 2) for mobile services: in-cabin THz hotspots, train-to-train links, augmented reality/virtual reality applications, THz device-to-device communications at home, and THz multi-hop sidelink relays. A new radiolocation use case is also proposed, which is a walk-through security imaging system co-located with THz “Touch-and-Get” data kiosks. A new use case proposed for the ISM bands is a high-/low-power continuous-wave illumination imaging system and frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radars for standoff detection and non-destructive testing. These new use cases are expected to generate more substantial system parameters (e.g., power, antenna gain, modulation scheme, bandwidth) to be further studied under simulation or measurements and researched for compatibility with passive services.

Green-colored bands are for fixed or land mobile services; gray-colored bands are RR5.340 prohibited bands or reserved for passive services, including EESS; orange-colored bands are for inter-satellite services; and the yellow-colored band is for the ISM band at 244 GHz9,21,58. The attenuation traces overlap between wet air (blue curve) and total air (black curve) conditions.

Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

The FCC serves as the primary regulatory body in the U.S. that is responsible for managing spectrum resources across various applications, including wireless communications, passive sensing, and experimental radio services. In the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 47 provides the legal framework for spectrum allocation and regulation, particularly in Part 2 (Frequency Allocations and Radio Treaty Matters; General Rules and Regulations) and Part 5 (Experimental Radio Service)58. The FCC Office of Engineering and Technology also provides guidelines in radiated emission measurement for devices operating above 95 GHz up to 750 GHz60. These regulations ensure a structured approach to spectrum access while accommodating scientific, industrial, and communication needs. In general, the spectrum bands can be categorized into prohibited bands reserved for remote sensing purposes and frequency bands for fixed, mobile, and other applications.

Prohibited bands for passive sensing and earth atmospheric observations

To protect the integrity of ground-based atmospheric sensing and passive scientific applications, certain frequency bands have been prohibited from active transmissions. According to FCC regulations, the bands required to protect passive Earth observation and atmospheric monitoring systems include 200–209 GHz, 226–231.5 GHz, and 250–252 GHz58. These prohibited bands are crucial for applications including radio astronomy, climate monitoring, and remote sensing, where even small interference could result in observation inaccuracy. These prohibited bands align with those of ITU to preserve passive sensing capabilities, particularly in mmWave and sub-THz frequency ranges. Similar to the U.S., in Europe, the U.K., Japan, and Australia, these three bands (200–209 GHz, 226–231.5 GHz, and 250–252 GHz) are also reserved for passive sensing and radio astronomy.

Spectrum for fixed and mobile services

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) within the U.S. Department of Commerce, in conjunction with the FCC, has identified several high-frequency bands for fixed and mobile service applications, which permit active communication applications under defined conditions. These bands include 209–226 GHz, 231.5–235 GHz, 238–241 GHz, and 252–265 GHz58. These sub-THz allocations provide significant opportunities for high-frequency communication technologies, including 6G mobile and fixed wireless networks, ultra-high-speed backhaul, and point-to-point wireless links. In addition, several frequency bands, including 296–306 GHz, 313–318 GHz, and 333–356 GHz, can also be used for similar mobile and fixed wireless services under the condition of necessary protection for passive sensing and radio astronomy. Additionally, the 244–246 GHz band has been designated for ISM equipment, with a center frequency at 245 GHz61. This allocation supports applications such as high-frequency industrial processes, biomedical research, and precision sensing systems.

Earth Exploration-Satellite Service (EESS)

The EESS plays a major role in remote sensing applications, including climate monitoring, atmospheric studies, and Earth observation. Specific frequency bands within the 275–1000 GHz range have been identified for EESS operations, as listed in ITU-R Radio Regulations (RR) No. 5.565, which includes bands such as 275–277 GHz, 294–306 GHz, 316–334 GHz, and 342–349 GHz, among others58. These allocations facilitate high-precision sensing of atmospheric, oceanic, and land-based environmental parameters. According to ITU-R Report SM.2450 (2019) and related studies62, it has been determined that no additional regulatory protection measures are required for EESS operations in the 275-296 GHz, 306-313 GHz, and 320-330 GHz bands, provided that active systems comply with operational parameters specified in ITU-R recommendations. This suggestion deems the coexistence between EESS and other services in these bands as feasible, which relieves the concern over potential interference. As THz communication technologies mature, further studies may be necessary to assess the long-term impact on spectral integrity and data quality of EESS.

European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI)

The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), especially its Industry Specification Group (ISG) on THz, has conducted extensive studies on the spectrum above 100 GHz, which include promising use cases63 and feasible frequency bands64, as well as extensive survey on propagation channel measurements and developed channel models that can support future high-throughput wireless communication systems65. In its research, ETSI categorizes the 100 GHz to 1 THz range into distinct spectral regions based on their propagation characteristics, absorption losses, and potential for communication applications, which ETSI names as “transmission windows” and identifies specific frequency bands where electromagnetic waves experience lower atmospheric attenuation and can thus enable more efficient data transmission64. As shown in Fig. 4, these transmission windows serve as guidelines for selecting feasible bands for applications such as 6G ultra-high-speed backhaul links, THz high-resolution imaging, and next-generation radar systems, among other communication and sensing applications. ETSI ISG’s studies provide an insightful reference in standardizing the use of THz frequencies, which guarantee that future wireless systems can both operate efficiently and coexist in harmony with incumbent services such as passive sensing, radio astronomy, and EESS.

Seven transmission windows defined by ETSI from 100 GHz to 1 THz at the link distance of 100 meters at sea level with a temperature of 15 °C and water vapor density of 7.5 g/m364.

Future frequency bands and coexistence consideration above 100 GHz

In this section, we discuss frequency bands above 100 GHz that are promising in 6G wireless networks for cellular and inter-satellite services. When evaluating potential frequency bands above 100 GHz, major factors that should be taken into account include the attenuation caused by atmospheric components, including oxygen, water vapor, and other molecular absorptions, according to ITU-R P.676, which provides specific and path gaseous attenuation due to oxygen and water vapor66. The specific attenuation under dry air and wet air (with water vapor content of 7.5g/m3) in the frequency range of 170–350 GHz is shown in Fig. 3.

A long-held misconception about frequency bands above 100 GHz with excessively high path loss along propagation channels is that when the free-space path loss grows proportionally with the increase of frequency, the channel becomes extremely lossy. However, this view overlooks the scaling effect of antenna gains, which means that as a steerable or fixed beam maintains the same effective aperture, as the frequency increases, the link has a much reduced loss67. Modern wireless systems in cellular or Wi-Fi networks utilize beamforming to ensure that maximum or near maximum antenna gain is realized, especially at mmWave frequencies. To further illustrate this effect mathematically, suppose the gain of an antenna is expressed as

where \({A}_{e}^{{{\rm{TX}}}/{{\rm{RX}}}}\) is the effective aperture of the beam at either the transmitter (TX) or the receiver (RX) and λ is the wavelength. Substituting the antenna gain expression into the received power calculation according to the Friis free-space path loss formula (assuming that the transmitted power PTX and propagation distance d remain fixed), the received power is expressed as

This relationship above shows an increased received power (reduced loss) as frequency increases (wavelength decreases) while fixing the antenna apertures. Extensive field experiments and simulations based on NYUSIM up to 150 GHz in both MATLAB and ns-3 also corroborate these mathematical insights68,69,70,71. Additionally, as Eq. (1) shows, the antenna gain scales proportionally with the frequency. Therefore, an antenna array with a fixed aperture provides much higher gain at mmWave and sub-THz frequencies15,16. Such an additional gain largely offsets the distance-dependent path loss in free space or lightly/non-obstructed radio channels. Hence, a mmWave and sub-THz link can deliver more received power than a lower-frequency link72. Mobile carriers are already exploiting this property to roll out FWA services with massive bandwidth in the mmWave bands.

Recent global experimental efforts above 100 GHz

A snapshot of the most recent global efforts (results published in the recent two years) in THz channel measurement campaigns is provided in Table 5, highlighting the diversity of frequency ranges, deployment scenarios, and measurement bandwidths. These efforts span academia, industry, and government laboratories, emphasizing the growing momentum toward establishing realistic channel models and experimental platforms for future THz wireless systems. In the following, we summarize these recent results according to the test frequency and experiment scenario, highlighting key observations.

At the lower end of the THz spectrum (around 130–150 GHz), NYU WIRELESS has conducted measurements at 142 GHz using a 1 GHz bandwidth sliding correlator-based sounder in a variety of scenarios, such as indoor office, factory, and urban outdoor68,70,71. These studies provide key insight into statistical channel characterization and path loss modeling in industrial and urban outdoor scenarios at various THz bands, highlighting the potential for ultra-broadband communications in the 6G era. A study conducted by Princeton University focuses on diffuse scattering at 140 GHz with 10 GHz of bandwidth, contributing insights into reflection and multipath characteristics in the lower THz regime73. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has developed a testbed operating in a similar band of 141 GHz (in the D-band) with bandwidths up to 6.4 GHz for real-time near-field switch beamforming74. Notably, this channel sounder achieves a fast channel sweep of 512 μs and a fine 3D spatial resolution of 2 cm.

Another set of recent work focuses on studying the backhaul feasibility of different THz bands. Researchers from Oklahoma State University demonstrate through extensive field measurements the feasibility of outdoor links over 2.9 km at 130 GHz with a maximum 5.5 GHz bandwidth75, highlighting the potential for long-range non-line-of-sight applications. A collaborative effort from Northeastern University, Florida International University, and SUNY Polytechnic Institute developed a software-defined radio (SDR) platform at 147 GHz with the connectivity of a 2-km link76. Institutions in Europe and Asia also contribute significantly to showcasing the long-distance connectivity of THz bands. For example, Chalmers University and Ericsson in Sweden conducted W-band measurements (92–114 GHz) over a 1.5-km outdoor link77.

Moving on to the middle to high end of the THz spectrum (around 200–725 GHz), Collaborative efforts also explore novel scenarios such as chip-to-chip links at 300 GHz (Georgia Institute of Technology)78, jamming and security at 197.5 GHz (Brown and Rice)79, and weather-affected propagation, including snowfall, at 140 and 270 GHz (Brown and Beijing Institute of Technology)80. Researchers from Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China reported channel behavior in highly directional environments such as L-shaped intersections using bands centered around 300 and 360 GHz81. Notably, the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Lille University, and Osaka University extended measurements into the upper THz spectrum, demonstrating a photonics-enabled link operating from 500–724 GHz with a bandwidth of 250 GHz, achieving a throughput of 1.04 Tbps82.

Such a wide range of frequency bands and experimental scenarios being studied thus far reflects both the rising interest and deployment challenges of THz bands. Recent analytical studies above 100 GHz in satellite networks also show promising results in gradually bridging the gap between theory and reality83,84,85,86,87,88,89. Standardization efforts (such as IEEE 802.15.3d90) are still taking shape to identify feasible spectrum bands, develop accurate THz channel models, novel waveforms, and other physical-layer solutions. Based on the current spectrum allocation regulated by the ITU, several promising frequency bands that may satisfy both throughput and coexistence demands above 100 GHz are discussed below.

Short-distance “Whisper Radio” at 180 GHz

As shown in Fig. 3, the wet-air attenuation at around 180 GHz is approximately 20 dB/km, making its usage primary toward short-range communications under wet air conditions. However, this band is favorable when the water attenuation effect is less prominent, which usually occurs above the atmosphere. According to RR 5.562H, the spectral bands in the range of 174.8 GHz–182 GHz and 185 GHz–190 GHz are provisioned for the inter-satellite service for satellites in the geostationary-satellite orbit [38, §4.1.3]. According to RR 5.558, a bandwidth of 300 MHz is allocated between 174.5 GHz and 174.8 GHz for fixed, mobile, and inter-satellite services around 180 GHz. In addition, there is 7.5 GHz of bandwidth allocated for this purpose from 167 GHz, amounting to a total of 7.8 GHz feasible for broadband communication purposes.

220 GHz

The 209–225 GHz band offers a bandwidth of 17 GHz, which is also promising to achieve ultra-high throughput in the THz spectrum. This frequency range, which is under study by different research groups91,92,93 in both indoor and outdoor scenarios, has the potential to support high-throughput wireless transmission and short-range THz networks. A portion of this band, specifically 217–226 GHz, is currently allocated for space-based radio astronomy58. However, given the space-borne platform of radio astronomical observations and the directional characteristics of radio telescopes, this 217–226 GHz band may still be potentially reusable for terrestrial fixed and mobile services.

The feasibility of spectrum sharing in this range is further supported by the high atmospheric attenuation at sub-THz frequencies, which inherently limits interference between terrestrial and space-based applications. Additionally, the utilization of dynamic spectrum access (DSA) mechanisms and adaptive beamforming techniques could further enhance coexistence to minimize interference and manage spectrum access. Therefore, the 209–225 GHz band presents an opportunity for advancing future high-speed wireless communications while preserving existing space-based radio astronomy operations.

280 GHz

The 275–296 GHz frequency range provides a contiguous bandwidth of 21 GHz, which sets itself as a promising candidate for future ultra-broadband wireless communication systems. However, there is currently no formal allocation above 275 GHz from either ITU or FCC for communication services, leaving an open regulatory landscape for future standardization and spectrum policy development. Because of the benefit of this spectrum’s ultra-wide bandwidth, research groups around the world have been actively conducting experiments in the frequency band above 275 GHz to evaluate its feasibility for practical wireless connectivity. Recent demonstrations, including long-range point-to-point links at 300 GHz94, demystify the long-time misconception about the propagation distance limitation in these tremendously high frequencies9. More data-hungry applications and services, such as holographic massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) communications, will likely find current networks as a bottleneck and bandwidth allocation limited, necessitating next-generation wireless networks to explore alternative options at THz bands to satisfy these growing demands.

One of the primary advantages of this band is its favorable propagation characteristics, particularly in low-humidity environments and line-of-sight (LoS) conditions. Compared to other THz bands, the 275–296 GHz range exhibits moderate atmospheric attenuation, which makes it well-suited for applications such as indoor point-to-multipoint communications, ultra-high-speed network-on-chip interconnects, wireless data center, and THz-band fiber replacement technologies. Additionally, the contiguous bandwidth of 21 GHz in this spectrum range enables multi-gigabit per second (Gbps) to terabit per second (Tbps) data transmission, which provides a distinct benefit for high-capacity wireless links, high-resolution imaging, and secure communications with spread spectrum or frequency hopping schemes.

However, several technical challenges remain in device development in this spectrum, which sets limits on power amplification techniques, detectors with large dynamic range, and efficient transceivers. Recent advancements in solid-state THz sources, graphene-based transistors, and photonic-integrated circuit architectures indicate significant progress toward overcoming these challenges. But it may take time for future WRCs and global markets to fully adopt these frequency bands for commercial wireless networks.

Future research directions for emerging spectrum allocations and coexistence

The increasing demand for efficient spectrum utilization, coexistence with incumbent services, and regulatory adaptability necessitates innovative approaches in spectrum management, energy efficiency, and hybrid network architectures. Given the existing and prospective frequency bands at UHF, mid-band, upper mid-band, and above 100 GHz for future wireless network design, several key research directions, including new scenarios of wireless communication system deployment in these emerging bands, intelligent spectrum allocation strategies that leverage artificial intelligence, consideration of energy efficiency in spectrum sharing, and integrated terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks, are expected to enhance spectrum sharing and adaptive allocation strategies.

New scenario in the upper mid-band

In addition to the commonly studied scenarios, such as urban microcell street canyon, urban macrocell, indoor office, and rural macrocell in 3GPP TR 38.90195, an emerging scenario of suburban macrocell provides unique deployment opportunities in the upper mid-band spectrum, including high-speed broadband for residential areas, fixed wireless access as a fiber alternative, and smart city applications. Existing channel models may fall short in faithfully characterizing the channel statistics in this scenario with a sparse presence of residential structures, trees, and foliage, while an outdoor-to-indoor penetration loss study at 7–24 GHz under different materials and beamforming strategies can also be beneficial to comprehend the upper mid-band’s potential in smart-home network applications.

In a recently concluded channel modeling study (in June 2025) as part of 3GPP Release 19, researchers from Sharp, Nokia, Intel, and Ericsson, among other companies conducted field measurements and simulations at both sub-6 GHz and 7–24 GHz in suburban environments, to study the path loss, delay spread, LoS probability, and number of multipath clusters, among others96. A new plywood penetration loss model and an outdoor-to-indoor penetration loss model are also introduced in this study.

AI-assisted spectrum allocation strategies

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in spectrum management is a transformative step toward real-time, adaptive spectrum allocation. Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) and deep-learning algorithms can analyze historical spectrum usage data, learn spectrum access patterns, detect interference trends, and predict optimal frequency allocations, thus improving overall spectrum efficiency.

Moreover, deep reinforcement learning algorithms can facilitate environmental context-aware or semantic-aware spectrum decision-making, which is based on environmental conditions, network traffic demands, and regulatory constraints97. However, a prerequisite is that the data required to train these AI-driven spectrum management systems must be carefully curated and validated to ensure accuracy, fairness, and compliance with regulatory standards. Open-source access to the data also allows fair comparisons and standardized assessments across different ML algorithms.

Future research needs to ensure that algorithms can recognize and address bias in AI models and provide interpretability98. Other critical challenges in the deployment of AI-assisted spectrum allocation strategies include protecting spectrum usage data privacy99, adaptability of AI models in dynamic spectrum usage, and SDR system with intelligent spectrum agility100.

Energy-efficient spectrum sharing

Energy efficiency is a crucial consideration in next-generation spectrum-sharing frameworks. The 6-GHz band (5.925–7.125 GHz) provides an example of licensed and unlicensed spectrum sharing by Ofcom in the U.K. and the FCC in the U.S.27,101, where efficient spectral resource utilization is achieved by enforcing power and coordination constraints. In the 6-GHz band, unlicensed users operate in IEEE 802.11ax standard (also known as Wi-Fi 6), which provides a data rate at least twice as fast as that of the legacy Wi-Fi networks101, without causing interference to incumbent licensed users that operate wireless backhaul links at the 6-GHz band. This model serves as a blueprint for future spectrum-sharing strategies in higher-frequency bands, particularly in the upper mid-band, mmWave, and THz ranges.

Energy efficiency for NTN applications also remains an important issue. Unlike traditional terrestrial links, since the D2D links traverse the Earth’s atmosphere, the operation of the non-terrestrial connectivity is subject to spectrum regulations and power spectral density limits to minimize the potential OOB interference with other space-borne services. Meanwhile, concerns about increased OOB interference not only arise from the other communication services (such as the ones in geostationary orbit), but also from the radio astronomy community102. The coexistence issue between terrestrial and non-terrestrial connectivity, as well as active communication and passive sensing services, will remain critical in 6G network deployments.

Additionally, future spectrum coexistence studies need to focus on optimizing transmission power according to real-time demand. The adoption of energy-efficient beamforming, AI-driven adaptive power control, and energy-efficient network architectures will be essential in reducing energy consumption while maintaining high spectral efficiency. The development of green spectrum-sharing policies by regulatory bodies (such as the recent FCC motion to review its rules on maximum transmissible power for satellites in the Ka- and Ku-bands103) around the world can also contribute to the achievement of sustainability goals in wireless communication networks. In a most recent proposed rulemaking by the FCC released on June 13, 2025 in modernizing spectrum sharing for satellite broadband104, it is probable that the traditional equivalent power-flux density (EPFD) limits on geostationary and non-geostationary satellites that operate at 10.7–12.7 GHz, 17.3–18.6 GHz, and 19.7–20.2 GHz bands will be revised by the FCC and a degraded throughput methodology will be adopted. These frequency bands coexist with other services, such as radio astronomy and terrestrial applications. This recent FCC initiative will likely prompt broader ITU adoption of the degraded throughput criterion going forward.

Integrated terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks

The convergence of terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks (NTNs) is another critical area of research to achieve seamless global connectivity in future wireless networks105,106. Such an integration of satellites, high-altitude platforms (HAPs), and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) with terrestrial infrastructure enables ubiquitous coverage, enhanced resilience, and extended service availability in remote and underserved areas. Although there are existing partnerships and tests proven to be feasible in serving mobile users directly from satellites in low Earth orbits30, data and broadband services are still not accomplished.

In addition, several challenges in integrating terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks include vertical handover mechanisms across different networks for seamless mobility between terrestrial base stations and non-terrestrial nodes107,108, as well as latency and synchronization issues for applications requiring real-time communication109,110, such as autonomous vehicles and emergency response networks.

Coexistence of D2D with ground-based astronomy

Previous studies have shown large deployable arrays designed for direct-to-device (D2D) links with noticeable optical brightness111. For example, an observation campaign shows the peak magnitude of 0.4 for BlueWalker 3 satellite, making it one of the brightest objects in the sky111,112. The magnitude in astronomy refers to the Johnson-Cousins magnitude, which is a unit-less measure of the brightness of an object perceived in a defined spectrum113 and a lower value indicates higher brightness. The International Astronomical Union (IAU)’s Center for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference (CPS) recommends that satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) should not be visible by the unaided eye114. More specifically, the CPS further recommends the magnitude of LEO satellites to be around 7.

The FCC Space Bureau has started the regulation process by including clear guidelines, including a recent authorization in August 2024 for AST to aim for 6th-to-7th-magnitude brightness and to coordinate mitigation measures with the astronomy community115,116. It is foreseeable that future launches will also abide by similar requirements to mitigate the brightness issues to ground-based astronomy.

Conclusion and discussion

This article outlines a vision of spectrum opportunities for the wireless future. Through surveying existing global allocations for passive and active services, interference considerations, and technical challenges related to propagation and hardware constraints, we identify potentially viable spectrum bands across UHF, upper mid-band, and above 100 GHz, as summarized in Table 6. The findings provide valuable insights into the most promising frequency bands for future wireless systems, including direct-to-device satellite applications to 6G cellular services, while highlighting key regulatory and technological hurdles that must be addressed to enable the global adoption of upper mid-band and THz spectra for future wireless communications.

As WRC-27 approaches, discussions on spectrum opportunities for the wireless future will continue to evolve. Consistent global regulations and cooperation will be essential to support the growing demand for next-generation wireless networks while protecting the needs of Earth observation and radio astronomy. Moving forward, the adoption of spectrum-sharing strategies, opportunities in the upper mid-bands, the OOB interference challenge for fixed and mobile terrestrial links adjacent to satellite downlink, and D2D satellite service will be critical in maximizing the efficient use of radio frequency spectrum while addressing the concerns of both active and passive service stakeholders.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Rappaport, T. S. Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

Calabrese, F. D., Monghal, G., Anas, M., Maestro, L. & Penttinen, J. T. LTE Radio Network. The LTE/SAE Deployment Handbook 95–136 (2011).

Federal Communications Commission. Report and order and further notice of proposed rulemaking. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/fcc-16-89a1.pdf (2016).

Federal Communications Commission. FCC Takes Next Steps on Facilitating Spectrum Frontiers Spectrum: Use of Spectrum Bands Above 24 GHz For Mobile Radio Services. https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-takes-next-steps-facilitating-spectrum-frontiers-spectrum (2017).

Federal Communications Commission. Auction 101: Spectrum Frontiers -28 GHz. https://www.fcc.gov/auction/101 (2019).

Thillo, W. V. The Key Takeaways From Reliance Jio’s mmWave FWA Rollout. https://www.thefastmode.com/expert-opinion/36142-the-key-takeaways-from-reliance-jio-s-mmwave-fwa-rollout (2024).

Poggianti, P. A ‘Quiet’ 5G Application Success Story. https://www.comsoc.org/publications/ctn/quiet-5g-application-success-story (2024).

Wyrzykowski, R. 5G Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) Success in the US: A Roadmap for Broadband Success Elsewhere? https://www.opensignal.com/2024/06/06/5g-fixed-wireless-access-fwa-success-in-the-us-a-roadmap-for-broadband-success-elsewhere (2024).

Rappaport, T. S. et al. Wireless communications and applications above 100 GHz: Opportunities and challenges for 6G and beyond. IEEE Access 7, 78729–78757 (2019).

Qualcomm. Snapdragon X75 5G Modem-RF System. https://www.qualcomm.com/products/technology/modems/snapdragon-x75-5g-modem-rf-system (2023).

Bazzi, A. et al. Upper Mid-Band Spectrum for 6G: Vision, Opportunity and Challenges. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.17914 (2025).

Shakya, D. et al. Comprehensive FR1 (C) and FR3 lower and upper mid-band propagation and material penetration loss measurements and channel models in indoor environment for 5G and 6G. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. (2024).

Ghosh, M. New Regulatory Activities for Sharing in the 3.1-3.45 GHz and 7.125-8.4 GHz Frequency Bands. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 32, 14–15 (2025).

5G Americas. The 6G Upgrade in the 7-8 GHz Spectrum Range: Coverage, Capacity, and Technology White Paper (2024).

Rappaport, T. S., Qiao, Y., Tamir, J. I., Murdock, J. N. & Ben-Dor, E. Cellular broadband millimeter wave propagation and angle of arrival for adaptive beam steering systems. In 2012 IEEE Radio and Wireless Symposium, 151–154 (IEEE, 2012).

Nie, S., MacCartney, G. R., Sun, S. & Rappaport, T. S. 72 GHz millimeter wave indoor measurements for wireless and backhaul communications. In 2013 IEEE 24th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC) 2429–2433 (IEEE, 2013).

Azari, M. M. et al. Evolution of non-terrestrial networks from 5G to 6G: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 24, 2633–2672 (2022).

Sohul, M. M., Yao, M., Yang, T. & Reed, J. H. Spectrum access system for the citizen broadband radio service. IEEE Commun. Mag. 53, 18–25 (2015).

Katwe, M. V. et al. Cmwave and sub-THz: Key radio enablers and complementary spectrum for 6G, in IEEE Wireless Communications, https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.2025.3599659 (2025).

Akyildiz, I. F., Han, C., Hu, Z., Nie, S. & Jornet, J. M. Terahertz band communication: An old problem revisited and research directions for the next decade. IEEE Trans. Commun. 70, 4250–4285 (2022).

Polese, M. et al. Coexistence and spectrum sharing above 100 GHz. Proc. IEEE 111, 928–954 (2023).

Johnson, R. Ten Years Later: A New Vision for the 3 GHz Band. https://www.attconnects.com/ten-years-later-a-new-vision-for-the-3-ghz-band/ (2024).

Dano, M. DoD reportedly enlists in AT&T’s plan to blow up CBRS band. https://www.lightreading.com/5g/dod-reportedly-enlists-in-at-t-s-plan-to-blow-up-cbrs-band (2025).

National Telecommunications and Information Administration. National Spectrum Strategy Implementation Plan. https://www.ntia.gov/sites/default/files/publications/national-spectrum-strategy-implementation-plan.pdf (2024).

Federal Communications Commission. FCC FACT SHEET: Expanding Flexible Use of the 12.2-12.7 GHz Band & Expanding Use of the 12.7-13.25 GHz Band for Mobile Broadband or Other Expanded Use. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-392970A1.pdf (2023).

Paroutsas, A. A leap towards 6G: Spectrum allocation and its global impact. https://www.qualcomm.com/news/onq/2024/03/a-leap-towards-6g-spectrum-allocation-and-its-global-impact (2024).

Ofcom. Mobile and Wi-Fi in Upper 6 GHz: Why hybrid sharing matters. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/spectrum/innovative-use-of-spectrum/vision-for-sharing-upper-6-ghz-spectrum-between-wi-fi-and-mobile (2024).

Andrews, J. G., Humphreys, T. E. & Ji, T. 6G Takes Shape. IEEE BITS Inf. Theory Mag. 4, 2–24 (2024).

Rainbow, J. Globalstar soars on Apple’s $1.7 billion satellite investment. https://spacenews.com/globalstar-soars-on-apples-1-5-billion-satellite-investment/ (2024).

T-Mobile Starlink Beta Takes Off. https://www.t-mobile.com/news/network/t-mobile-starlink-beta-open-for-all-carriers (2025).

AT&T and AST SpaceMobile Announce Definitive Commercial Agreement. https://about.att.com/story/2024/ast-spacemobile-commercial-agreement.html (2024).

AST SpaceMobile. AST SpaceMobile secures strategic investment from AT&T, Google and Vodafone https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1780312/000149315224002914/ex99-1.htm (2024).

TheKOOKReport. AST SpaceMobile: The mobile satellite cellular network monopoly. https://www.kookreport.com/post/ast-spacemobile-asts-the-mobile-satellite-cellular-network-monopoly-please-find-my-final-comp (2024).

Boumard, S., Moilanen, I., Lasanen, M., Suihko, T. & Höyhtyä, M. A technical comparison of six satellite systems: Suitability for direct-to-device satellite access. In 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), 01–06 (IEEE, 2023).

Harrison, T.Building an Enduring Advantage in the Third Space Age (American Enterprise Institute, 2024).

Chief, S. B. & Chief, W. T. B. A. Application for Authority for Modification of the SpaceX NGSO Satellite System to Add a Direct to Cellular System. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-25-197A1.pdf (2025).

Xing, Y. & Rappaport, T. S. Terahertz wireless communications: co-sharing for terrestrial and satellite systems above 100 GHz. IEEE Commun. Lett. 25, 3156–3160 (2021).

National Telecommunications and Information Administration.Manual of regulations and procedures for federal radio frequency management, January 2023 Revision of the January 2021 Edition. NTIA, U.S. Department of Commerce (2023).

Chini, P., Giambene, G. & Kota, S. A survey on mobile satellite systems. Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 28, 29–57 (2010).

Musey, J. A. & Farrar, T. Spectrum for emerging direct-to-device satellite operators https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm?abstractid=5150379 (2025).

Inmarsat. Inmarsat Broadband Global Area Network. https://developer.inmarsat.com/technology/bgan/ (2024).

Jewett, R. Ligado Files for Chapter 11, Makes Deal with AST SpaceMobile for MSS Spectrum. https://www.satellitetoday.com/finance/2025/01/06/ligado-files-for-chapter-11-makes-deal-with-ast-spacemobile-for-mss-spectrum/ (2025).

Federal Communications Commission. FCC FACT SHEET: Single Network Future: Supplemental Coverage from Space. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-400678A1.pdf (2024).

Brian Wang. FCC Allows SpaceX Starlink Direct to Cellphone Power for 4G/5G Speeds. https://www.nextbigfuture.com/2025/03/fcc-allows-spacex-starlink-direct-to-cellphone-power-for-4g-5g-speeds.html (2025).

Federal Communications Commission, Space Bureau. Public Notice: Lynk Global License Modification to Provide Supplemental Coverage from Space in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands. Tech. Rep. DA 25-385, Federal Communications Commission. https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-25-385A1.pdf (2025).

Lagunas, E., Tsinos, C. G., Sharma, S. K. & Chatzinotas, S. 5G cellular and fixed satellite service spectrum coexistence in C-band. IEEE Access 8, 72078–72094 (2020).

Lim, B. & Vu, M. Interference analysis for coexistence of terrestrial networks with satellite services. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23, 3146–3161 (2023).

Ying, M. et al. Upper mid-band channel measurements and characterization at 6.75 GHz FR1 (C) and 16.95 GHz FR3 in an Indoor factory scenario. In ICC 2025-IEEE International Conference on Communications 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Shakya, D. et al. Wideband penetration loss through building materials and partitions at 6.75 GHz in FR1(C) and 16.95 GHz in the FR3 upper mid-band spectrum. In GLOBECOM 2024 - 2024 IEEE Global Communications Conference 1665–1670 (2024).

Shakya, D. et al. Urban outdoor propagation measurements and channel models at 6.75 GHz FR1(C) and 16.95 GHz FR3 upper mid-band spectrum for 5G and 6G. In ICC 2025-IEEE International Conference on Communications 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Yang, H. et al. 6G Channel measurement in urban, dense urban scenario and massive ray-tracing-based coverage analysis at 7.5 GHz. In ICC 2025-IEEE International Conference on Communications 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Abbasi, N. A. et al. Ultra-wideband double-directional channel measurements and statistical modeling in urban microcellular environments for the Upper-Midband/FR3. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.20755 (2024).

Kang, S. et al. Cellular wireless networks in the upper mid-band. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 5, 2058–2075 (2024).

Morini, M., Moro, E., Filippini, I. & Capone, A. Will the Upper 6 GHz Bands Work for 5G NR? A urban field trial. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Workshop on Wireless Network Testbeds, Experimental evaluation & Characterization 49–55 (2023).

International Telecommunication Union, Radiocommunication Sector. ITU-R Preparatory Studies for WRC-27. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-R/study-groups/rcpm/Pages/wrc-27-studies.aspx (2024).

International Telecommunication Union, Radiocommunication Sector. World Radiocommunication Conference 2023 (WRC-23) Final Acts. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-r/opb/act/R-ACT-WRC.16-2024-PDF-E.pdf (2024).

De Matthaeis, P., von Deak, T., Oliva, R. & Bollian, T. Agenda items of the world radiocommunication conference 2023 relevant to remote sensing. In IGARSS 2020-2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 3781–3783 (IEEE, 2020).

Federal Communications Commission. FCC Online Table of Frequency Allocations, 47 C.F.R. §2.106 (Federal Communications Commission, Office of Engineering and Technology, Policy and Rules Division, 2025).

ITU-R 237/1 Document 1A/88-E. Technical and operational characteristics and spectrum use of radiocommunication services in the frequency ranges above 275 GHz (2025).

Federal Communications Commission, Office of Engineering and Technology, Laboratory Division. Sub-THz Emission Measurement Guidance. Tech. Rep. 800303 D01 (Draft), Federal Communications Commission https://apps.fcc.gov/oetcf/kdb/forms/FTSSearchResultPage.cfm?id=240776&switch=P (2025).

Federal Communications Commission. FCC FACT SHEET: Spectrum Horizons First Report and Order—ET Docket 18-21. https://mmwavecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/DOC-356297A1-FCC-Report-Order.pdf (2019).

Report ITU-R SM.2450-0. Sharing and compatibility studies between land-mobile, fixed and passive services in the frequency range 275-450 GHz. https://www.itu.int/pub/R-REP-SM.2450-2019 (2019).

European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), GR THz 001 ETSI ISG THz. TeraHertz technology (THz); Identification of Use Cases for THz Communication Systems. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_gr/THz/001_099/001/01.01.01_60/gr_THz001v010101p.pdf (2024).

European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), GR THz 002 ETSI ISG THz. TeraHertz technology (THz); Identification of frequency bands of interest for THz communication systems. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_gr/THz/001_099/002/01.01.01_60/gr_THz002v010101p.pdf (2024).

European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), GR THz 003 ETSI ISG THz. TeraHertz modeling (THz); Channel measurements and modeling in THz bands. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_gr/THz/001_099/003/01.01.01_60/gr_THz003v010101p.pdf (2024).

International Telecommunication Union, Radiocommunication Sector. Recommendation ITU-R P.676, Attenuation by atmospheric gases and related effects (2022).

Xing, Y. & Rappaport, T. S. Propagation measurement system and approach at 140 GHz-moving to 6G and above 100 GHz. In 2018 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), 1–6 (2018).

Ju, S. et al. 142 GHz sub-terahertz radio propagation measurements and channel characterization in factory buildings. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 23, 7127–7143 (2023).

Poddar, H. et al. Full-stack end-to-end mmWave simulations using 3GPP and NYUSIM channel model in ns-3. In ICC 2023-IEEE International Conference on Communications 1048–1053 (IEEE, 2023).

Kanhere, O., Poddar, H. & Rappaport, T. S. Calibration of NYURay for ray tracing using 28, 73, and 142 GHz channel measurements conducted in indoor, outdoor, and factory scenarios. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 73, 405–420 (2025).

Shakya, D. et al. Radio propagation measurements and statistical channel models for outdoor urban microcells in open squares and streets at 142, 73, and 28 GHz. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 72, 3580–3595 (2024).

Ju, S. et al. Scattering mechanisms and modeling for terahertz wireless communications. In ICC 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 1–7 (IEEE, 2019).

Shen, R. & Ghasempour, Y. Characterizing sub-terahertz reflection and its impact on next-generation wireless networking. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1–1 (2024).

Bang, J. et al. Real-Time 141 GHz JCAS channel sounder: near-field switched beamforming, carrier multiplexing, and context awareness. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 73, 1–14 (2025).

O’Hara, J. F. et al. Long-distance, multi-gigabit-per-second terahertz wireless communication. In MILCOM 2024–2024 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM) 270–275 (2024).

Karunanayake, K., Singh, A., Jornet, J. & Madanayake, A. PanTera: RF-SoC Testbed using PYNQ platform for 147 GHz SDR with 64 Mbps at up to 2 km. In MILCOM 2024-2024 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), 111–116 (IEEE, 2024).

Hörberg, M. et al. A W-band, 92-114 GHz, real-time spectral efficient radio link demonstrating 10 Gbps peak rate in field trial. In 2022 IEEE/MTT-S International Microwave Symposium—IMS 2022 545–548 (2022).

Zajić, A. Future of terahertz channel measurements and modeling in computer systems. In 2023 17th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), 1–5 (2023).

Shrestha, R., Guerboukha, H., Fang, Z., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Jamming a terahertz wireless link. Nat. Commun. 13, 3045 (2022).

Liu, G. et al. Impact of snowfall on terahertz channel performance: measurement and modeling insights. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 14, 691–698 (2024).

Wang, Y., Li, Y., Yu, Z. & Han, C. 300 GHz dual-band channel measurement, analysis and modeling in L-shaped scenarios. IEEE Trans. Vehicular Technol. 74, 11025−11038 (2025).

Ducournau, G. et al. Photonics-enabled 1.04-Tbit/s aggregated data-rate in the 600-GHz-band. In 2023 Asia-Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC) 327–329 (IEEE, 2023).

Torrens, S. A., Petrov, V. & Jornet, J. M. Modeling interference from millimeter wave and terahertz bands cross-links in low earth orbit satellite networks for 6G and beyond. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 42, 1371–1386 (2024).

Aliaga, S., Alqaraghuli, A. J. & Jornet, J. M. Joint terahertz communication and atmospheric sensing in low earth orbit satellite networks: physical layer design. In 2022 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM) 457–463 (IEEE, 2022).

Aliaga, S., Petrov, V. & Jornet, J. M. Cross-link interference modeling in 6G millimeter wave and terahertz LEO satellite communications. In ICC 2023-IEEE International Conference on Communications 2577–2582 (IEEE, 2023).

Aliaga, S., Alqaraghuli, A. J., Singh, A. & Jornet, J. M. Enhancing joint communications and sensing for cubesat networks in the terahertz band through orbital angular momentum. In 2023 IEEE Aerospace Conference 1–14 (IEEE, 2023).

Aliaga, S. et al. Analysis of integrated differential absorption radar and subterahertz satellite communications beyond 6G. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 17, 19243–19259 (2024).

Alqaraghuli, A. J., Siles, J. V. & Jornet, J. M. The road to high data rates in space: terahertz versus optical wireless communication. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 38, 4–13 (2023).

Alqaraghuli, A. J., Abdellatif, H. & Jornet, J. M. Performance analysis of a dual terahertz/ka band communication system for satellite mega-constellations. In 2021 IEEE 22nd International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM) 316–322 (IEEE, 2021).

IEEE. IEEE 802.15.3-2023, IEEE Standard for Wireless Multimedia Networks. https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/802.15.3/10801/ (2024).

Al-Dabbagh, M. D. et al. Characterization of sub-THz channel sounding systems in OTA measurement scenarios using a vector network analyzer. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagation 73, 1–1 (2025).

Liao, X. et al. Measurement-based channel characterization in indoor iiot scenarios at 220 GHz. In 2024 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Lyu, Y., Yu, Z. & Han, C. 220 GHz urban microcell channel measurement and characterization on a university campus, 2024 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps),Cape Town, South Africa, pp. 1−5, https://doi.org/10.1109/GCWkshp64532.2024.11101111 (2024).

Sen, P., Siles, J. V., Thawdar, N. & Jornet, J. M. Multi-kilometre and multi-gigabit-per-second sub-terahertz communications for wireless backhaul applications. Nat. Electron. 6, 164–175 (2023).

3GPP. Study on channel model for frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz (3GPP TR 38.901 version 16.1.0 Release 16) http://www.etsi.org/standards-search (2020).