Abstract

We present techniques for estimating key parameters of OneWeb’s Ku-band downlink signal (10.7–12.7 GHz) and reveal it as a single-carrier QPSK signal with a 230.4 MHz symbol rate. The techniques also estimate the signal’s roll-off factor and center frequencies. We further provide the first published account of OneWeb signal demodulation, revealing the basic frame structure of the downlink signal, including a synchronization sequence that repeats every millisecond and is common across all beams, channels, and satellites. Identifying this sequence enables making time-of-arrival measurements from OneWeb signals. These findings contribute to the growing body of research focused on repurposing low-Earth-orbit satellite communication signals for positioning, navigation, and timing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid expansion of low-Earth-orbit (LEO) mega-constellations has enabled unprecedented global broadband coverage. These mega-constellations could also revolutionize the positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) landscape by serving as a new source of signals for PNT1. While their primary mission is usually broadband communication, there have been studies exploring the cost for a constellation operator adopting a fused communications-and-PNT service2, and numerous studies on use of their signal for opportunistic PNT. LEO signals offer increased satellite visibility, enhanced geometric diversity3, and improved robustness through a greater variety of signals. Compared to traditional Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals, LEO communication signals provide significantly higher bandwidths and received power4. These advantages make repurposing LEO signals as a complement or backup to GNSS particularly appealing, especially amid rising threats of jamming and spoofing5,6,7,8,9.

With over 600 LEO satellites, OneWeb is the second-largest LEO constellation after SpaceX’s Starlink10. Its polar orbits provide global coverage and are 15 times closer to Earth than GPS orbits. Moreover, its space-to-Earth link operates in the accessible 10.7–12.75 GHz band.

Exploiting LEO signals for PNT has been the focus of recent studies. Iridium’s potential for high dynamic applications using Doppler measurements was explored in ref. 11. Starlink’s signal was used for Doppler-based positioning in ref. 12,13, and carrier-phase-based positioning was demonstrated in ref. 14 using tones extracted from the signal that are no longer present in newer satellites. Recent surveys have studied integrating Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTNs) with current 5G and future 6G networks for localization systems15. Existing multi-constellation Doppler-based positioning results also reinforce the value LEO signals offer with their variety and geometric diversity16,17,18,19,20. In most cases, these LEO signals are utilized as Signals of Opportunity (SoP), meaning the authors had no cooperation with the satellite operators, and only used publicly available information and the signal itself.

Compared to pseudorange-based PNT techniques, Doppler-based techniques have worse timing accuracy by many orders of magnitude (milliseconds vs. nanoseconds), even under optimistic measurement noise and satellite clock offset rate assumptions3,21,22. Recognizing that many PNT applications of practical interest require accurate timing, we seek a characterization of OneWeb’s signal structure sufficient to enable pseudorange measurements, just as ref. 4 provided for Starlink. A recent paper has already demostrated pseudorange-based positioning with Starlink23, framed as a fused service. Using knowledge published in this paper we were also able to achieve pseudorange-based positioning with OneWeb asa SoP24.

References 23,24 outline LEO PNT strategies that describe different levels of cooperation with the constellation operators and a priori knowledge about the signals and ephemerides dedicated, fused, network-aided opportunistic, and standalone opportunistic. The information revealed in this paper would already be known for a dedicated or fused PNT service, but would be invaluable fora network-aided opportunistic scenario ora standalone opportunistic scenario.

Prior research has identified key characteristics of OneWeb’s signals, including approximate center frequencies, channel bandwidths25,26,27,28, and a 10-ms periodicity believed to be unique to each satellite beam16,25. But beyond these basic observations, OneWeb’s signal remains undisclosed and unpublished, unlike Starlink’s signal, whose structure and parameters are documented in ref. 4. Indeed, the existing literature does not even identify OneWeb’s modulation scheme. In ref. 25, the authors blindly detect the presence of modulation that repeats within the same satellite beam, but no demodulation is attempted. Furthermore, OneWeb’s Ku-band signal parameters have not been rigorously estimated, nor has any demodulated data been presented as in ref. 4. A detailed understanding of the signal structure, parameters, and synchronization sequences would enhance OneWeb’s potential as a PNT source and provide an analytical basis for assessing its limitations. This information is crucial to achieving our primary goal of harnessing OneWeb for positioning and timing through pseudorange-based methods.

We present a signal model for OneWeb’s Ku-band downlink, incorporating the identified modulation scheme and accounting for carrier frequency offset (CFO). Using established methods, we estimate the symbol rate and pulse shape roll-off, which are essential for demodulation. A typical Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (QPSK) demodulation processing chain is then applied to the signal. Analysis of the demodulated signal reveals that the 10-ms periodicity observed in prior studies may be merely a temporary consequence of the present low demand for OneWeb-provided data. We also identify a short synchronization sequence that repeats every 1 ms and is present on all satellites and beams.

To summarize, our paper offers three primary contributions. First, it provides a signal model for OneWeb’s Ku-band downlink and demonstrates how to estimate its key parameters. This process applies to all Gen 1 OneWeb satellites and likely to future versions as long as the signal remains single-carrier. Second, it identifies a synchronization sequence obtained by demodulating data from multiple satellites. The demodulation process further reveals that the 10-ms periodicity observed in prior studies is unlikely to be a permanent feature, as the data transmitted every 10 ms appear to be repeated default data. Finally, the paper shows how a local replica of the repeating modulation can be used to generate time-of-arrival (TOA) and Doppler measurements.

Signal capture

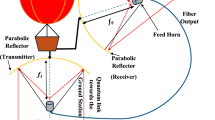

OneWeb’s roughly 650 satellites follow polar orbits at an altitude of 1200 km. Their downlink signal has approval for the 10.7–12.7 GHz space-to-Earth frequency band. A variety of commercially available user terminals (UTs) are available for OneWeb, with dual parabolic or flat panel designs. These would be ill-suited for our signal capture needs, as they do not provide access to the raw signal samples. Further, we would need to investigate the quality of the UT’s internal clock used for downconversion and sampling, or risk it having it skew any subsequent signal time stability analysis. Nonetheless, we can glean useful information from public OneWeb UT specifications, such as their being designed to support QPSK, 8PSK, and 16APSK modulation with a 250-MHz-wide channel spacing29.

In light of the challenges of using a commercial UT, we opted to employ our own steerable 90-cm offset parabolic dish with an approximately 3-degree beamwidth. Using publicly available ephemerides from North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in the form of Two-Line Elements (TLEs), we can steer the dish to track OneWeb satellites overhead. Our antenna’s narrow beamwidth limits captures to a single satellite at a time. As we show later on, the satellites have a fixed beam, where the beam footprint moves with the satellite, as opposed to a fixed-cell approach like Starlink’s, where the beam is fixed to a cell on the ground.

Figure 1 outlines the hardware used to capture the raw IQ samples. Our parabolic dish is equipped with a feedhorn connected to a low-noise block (LNB) with a conversion gain of 60 dB and a noise figure of 0.8 dB. The LNB downconverts 10.7–11.7 GHz signals to 950–1950 MHz, or 11.7–12.75 GHz to 1100–2150 MHz. The antenna’s nominal gain is 40 dBi at 12.5 GHz, but suffers at least 4–5 dB of losses due to lack of circular-to-linear polarizer and feedhorn misalignment. The antenna is located on the campus of The University of Texas at Austin, with a clear view of the sky.

The signal capture system allows selection between two capture modes: wide and narrow. The wide capture is a fixed 500 Msps, while the narrow capture is variable from 250 Msps and below. The downstream hardware then performs additional downmixing, bandpass filtering, and 16-bit complex sampling. Both the LNB and downstream downconversion and sampling hardware are locked to the same GPS-disciplined oven-controlled crystal oscillator (OCXO).

The usable bandwidth of the narrow capture varies depending on the sample rate, with a maximum of 200 MHz. The usable bandwidth of the wide capture is roughly 400 MHz. The capture system is capable of capturing on two channels at once, with the limitation that the sampling rate must be identical for the sampling to begin simultaneously. Such a setup is referred to as dual capture.

For single-carrier signals like OneWeb’s, the narrow captures are challenging or impossible to use for data recovery, but are useful for observing patterns in the signal structure. The wide captures produce roughly 2 GB/s of data, and are prone to overflow the host or device-side data buffers, resulting in dropped samples. As such, our hardware permits less than 10 s of continuous capture in that mode. For narrow captures, the device is capable of capturing for the duration a satellite is overhead.

Signal model

One might expect OneWeb to use orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) given its proven success in space-to-Earth communications by Starlink, and its domination in wireless communications. Various sources, including a test report for one of the UTs29, suggest OneWeb instead uses a single-carrier signal. Assuming the 250 MHz channel spacing specified in ref. 29 for the Ku band, OneWeb could presumably have 8 channels over the 2 GHz Ku-band, as assumed in ref. 25.

We claim, and later provide evidence, that OneWeb employs a Multi-Frequency Time Division Multiple Access (MF-TDMA) Single Carrier (SC) scheme on each of 8 separate frequency channels. The sections below outline the signal model for a SC QPSK signal, and subsequently the model of the received OneWeb signal.

QPSK signal model

Fundamentally, a SC signal is a train of pulses, each modulated by a phase and amplitude shift corresponding to the data symbol being transmitted on that pulse. The resulting continuous stream of symbols can be characterized by a simple signal model. The baseband signal model for a SC QPSK signal is given by

where statistically independent symbol phases \({a}_{m}\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}\triangleq \{0,1,2,3\}\) for \(m\in {\mathbb{Z}}\) can be encoded to represent two bits per symbol, and Tsym is the symbol period. The symbol phase values \({a}_{m}\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}\) will be referred to as symbols hereafter.

The pulse shaping function p(t) is left unspecified in (1). Our later signal parameter estimation shows that a square root raised cosine (SRRC) pulse nicely fits the OneWeb signals captured. Pulse shaping is essential to limit the excess bandwidth of the signal, for regulatory and interference purposes. Proper filtering of a pulse-shaped signal within the receiver can also reduce inter-symbol interference (ISI). Due to its popularity, we tested against the SRRC. The only parameter of note for the SRRC is its rolloff factor βr, which is a measure of its excess bandwidth.

In a single-carrier MF-TDMA protocol, subsequences of symbols are structured in a hierarchy of slots, frames, blocks, etc. We will use the term slot to describe the smallest grouping of symbols that is self-contained in the sense that it includes one or more predictable symbol sequences that mark the beginning of a slot and allow synchronization to it. A slot contains data destined for a small number of users—typically a single user. A contiguous set of slots whose data appear to be correlated in some way will be called a frame.

Different standards outline how frames are constructed. DVB-S2, a popular standard for satellite digital broadcasting, defines base band (BB) frames constructed from a number of input streams time-multiplexed into a physical layer (PL) frame. If a given stream has no data, a default physical-layer frame is inserted, or if a BB frame is incomplete, it is padded. Going from a BB frame to a PL frame also involves appending parity bits and modulating the data based on some modulation and coding scheme. While this processing may provide some structure to the symbol stream, the signal as observed by a receiver will nevertheless follow the model in (1).

Received signal model

The transmitted signal passes through the LEO-to-Earth channel and through the receiver front-end and discretization process. It is affected by multipath fading, Doppler, delay, filtering, digitization, and noise. SATCOM studies conducted in the Ku-band with measurements filtered to 80 MHz indicate that delay spread is minor for receivers experiencing only light shadowing and not near other objects30. We will treat the effect of delay spread as negligible, since in our case the open sky view provides a strong line-of-sight (LOS) component, with few if any multipath components entering our antenna’s narrow beam. Another study on dispersive delays in the Ku-band with a 200-MHz bandwidth receiver attributes a majority of the delay to atmospheric dispersion, and shows sub-millimeter delay31. Due to these findings, we adopt a simple additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) model for the received signal’s noise.

The most pressing phenomenon to model is the Doppler effect. For appropriately low bandwidths and time durations, one often assumes a narrowband model, which treats the Doppler effect as a simple frequency shift32. Using definitions from ref. 4, let vlos be the magnitude of the LOS velocity between the satellite and a receiver, and β ≜ vlos/c be the carrier frequency offset (CFO) parameter, where c is the speed of light. The narrowband model requires that βFsymTsynch ≪ 1 for Tsynch some interval over which we expect to maintain time synchronization, and for the symbol rate Fsym = 1/Tsym. For a LEO satellite with a large bandwidth like Starlink or OneWeb, the requirement is violated4,33,34. Thus, a wideband model that accounts for Doppler compression/dilation of the modulation, manifesting as time scaling, is needed in addition to frequency shifting. Given this, our received baseband analog model is

where Fc is the center frequency of the OneWeb channel, Fcr is the center frequency to which the receiver is tuned, τ0 is the delay experienced by the signal along the least-time path from transmitter to receiver, and w(t) is complex-valued zero-mean AWGN whose in-phase and quadrature components each have (two-sided) spectral density N0/2. It is important to note here that since β depends on the LOS velocity, it is time varying. Also, the satellite clock frequency error causes the same effect as LOS motion on CFO. To keep the model simple, we will lump the effects of satellite clock frequency error into the CFO parameter β unless otherwise indicated.

The final stage is discretization. The received signal passed through a low-pass filter h(t) with bandwidth Fh and sampled at a rate Fsr > Fh. As mentioned earlier, the useful bandwidth (3 dB) of our captured signals is roughly Fh = 200 MHz for the narrow capture, and Fh = 400 MHz for the wide capture. The signal is then quantized to 16 bits, and the resulting discrete-time signal is

At some stages of our processing, we further digitally low-pass filter the signal closer to the symbol rate Fsym for the wideband captures.

Signal parameter estimation

Three parameters must be known to reliably demodulate the signal. The symbol rate Fsym is most important, since any error in its estimate would strain a symbol timing recovery loop, leading to possible data loss.

Another important parameter is the rolloff factor βr of the pulse shaping function. A receiver incorporates a matched filter to maximize the SNR, where the filter’s impulse response is the time-reversed pulse shape. If the rolloff factor is not accurately estimated, the matched filter will be suboptimal, leading to increased ISI. In practice, our low-multipath environment and frequency-flat (non-dispersive) channel render the effect of ISI negligible, thus errors in βr will not significantly affect our demodulation.

The final parameter to estimate is the center frequency Fc of each channel. It is also not as consequential as Fsym since, from a receiver’s perspective, there are various techniques to blindly estimate a QPSK signal’s frequency offset. Estimators often lump together all the frequency shifting effects into a single value, corresponding to the exponent in (2), thereby compensating for Doppler before demodulation.

Exploiting signal cyclostationarity

To estimate the symbol rate, we exploit the cyclostationarity of the QPSK signal. There are numerous examples in the literature of exploiting cyclostationarity to identify periodicity in signals4,35,36. Specifically, the cyclic autocorrelation (CA) function of a QPSK signal reveals its symbol rate37,38,39.

The goal of CA analysis is to identify the hidden second-order periodicity in the signal. As an example, consider a simple sinusoid centered at fc with additive noise. If the noise power is sufficiently high, it can be difficult in the time domain to identify whether the signal is present, let alone its periodicity. Yet observing the sinusoid’s spectrum using a Fourier transform can easily reveal the hidden first-order periodicity as impulses at ±fc. Likewise, the CA function reveals the hidden second-order periodicity in an SC QPSK signal.

Let y(n) be the received signal described in (3). For now, assume β = 0 and Fcr = Fc. The autocorrelation function is defined as

where \(n,k\in {\mathbb{Z}}\), \({\mathbb{E}}[\cdot ]\) is the expectation operation, and y*(n) is the complex conjugate of y(n). Since s(t) in (1) is a pulse train with statistically independent phase shifts am, \(m\in {\mathbb{Z}}\), it follows that Ry(n, k) is periodic in n for certain values of k with a period equal to TsymFsr. This makes y(n) cyclostationary and allows for its autocorrelation function to be expanded in a Fourier series as

where \({\mathcal{A}}(\xi )=\{q/\xi :q\in {\mathbb{Z}}\}\). The particular set \({\mathcal{A}}({T}_{sym}{F}_{sr})\) contains the so-called cyclic frequencies. The Fourier coefficient \({R}_{y}^{\alpha }(k)\) constitutes the signal’s CA function.

Following the framework from ref. 40 for discrete-time signals, we approximate \({R}_{y}^{\alpha }(k)\) as

When operating on a finite-length signal, N is assumed to be much larger than the cyclic period of the signal, and the signal is assumed to be long enough that y(N − 1 + k) is defined for all k values of interest.

Estimation of F sym

We can now define an estimator for the symbol rate as

where \({\mathcal{S}}\) is some constrained set of cyclic frequencies around the expected symbol rate, and \(\widetilde{\alpha }=\alpha {F}_{sr}\) is scaled such that the search space is in Hertz. From a priori knowledge (e.g., observation of the signal’s spectrum and perusal of regulatory or commercial documentation), we can devise a narrow range of possible symbol rates over which to search.

In practice, our simplifying assumptions Fcr = Fc and β = 0 are not accurate, and this must be addressed. Note from the received baseband analog model in (2) that the exponential can be non-unitary when β ≠ 0 or Fcr ≠ Fc, but this will not affect the periodicity in the modulation and so will not affect \({\widetilde{R}}_{y}^{\alpha }(k)\) nor \({\widehat{F}}_{sym}\). On the other hand, for a nonzero β the modulation s(t − t0) gets compressed or stretched as s((t − t0)(1 − β)). This CFO time-scaling effect does change the periodicity—and therefore the observed symbol rate—of the received modulation.

To address this, we correct for the largest component of time scaling—the one due to LOS motion between the satellite and receiver—before performing symbol rate estimation. From the TLE satellite ephemerides and the known receiver location, we calculate the LOS velocity vlos, from which we estimate the motion-induced component of the CFO parameter as \(\widehat{\beta }={v}_{los}/c\). We then resample the received signal at \({F}_{sr}(1-\widehat{\beta })\) to undo the motion-induced time scaling. This results in at most a few Hertz of error in the Doppler shift, and similarly negligible error in the time scaling. Note that this process does not compensate for CFO introduced by transmitter clock frequency error, which, as will be shown, leads to slight residual errors in the symbol rate estimate.

After correcting for time scaling as described, we estimated Fsym based on four captures from March and June 2024. Fig. 2 shows the CA function (6), with N equal to the number of samples in 1 ms of data and k = 0, for each of the four captures. Peaks range from 230.399875 to 230.400180 MHz. Using only 1 ms of data instead of an infinitely long signal causes the peaks to present with finite width. The variance in the location of the peaks is due primarily to transmitter clock frequency error. The peaks are centered around 230.4 MHz to within about 200 Hz, from which we conclude that Fsym = 230.4 MHz.

Resampling

Resampling wide-capture signals at an integer multiple of Fsym facilitates symbol synchronization and demodulation. Recall that for wide-capture signals, the original signal is lowpass filtered to Fh < Fsr and sampled at Fsr > Fsym. Resampling to some Fs < Fsr proceeds by first applying a polyphase anti-aliasing filter at a new lower Fh≥Fsym followed by uniform resampling at Fs. The useful frequency content of the signal is reduced due to the filtering, but what is removed is either noise or adjacent channels, which are not of interest. For what follows, we resample wide captures at twice the symbol rate, going from Fsr = 500 Msps to Fs = 2Fsym = 460.8 Msps.

Narrow-capture signals are only used in this paper for long-duration correlation analysis, for which no resampling was required.

Symbol and carrier frequency synchronization

With Fsym known, one can proceed with carrier frequency and symbol synchronization. This is done with the resampled wide-capture signal. Carrier frequency synchronization proceeds in two steps, coarse CFO compensation followed by phase tracking. Coarse compensation can adopt the method from Sec. IV-B in which TLEs are used to wipe off the expected motion-induced frequency shift. But this method does not compensate for any offset Fcr − Fc from the receiver’s center frequency to the true channel center frequency, and ignoring this offset may strain the carrier phase tracking loop. Thus, a method such as ref. 41 is preferable for coarse CFO compensation. If, as demand increases, OneWeb adopts M-PSK with M > 4, one could extend the work in ref. 42, or rely on the method introduced in ref. 43. For this paper, we applied the FFT-based estimatorin ref. 41, which is based on a periodogram of the mth power of the received signal, where m is the modulation order resulting in m = 4 for QPSK.

which estimates the frequency that maximizes a periodogram of the 4th power of the received signal.

After coarse CFO compensation, inspection of the samples rendered on the complex plane reveals a QPSK-like constellation, but with samples between the canonical symbol locations due to the non-unitary number of samples per symbol, and with residual constellation rotation over time due to imperfect frequency synchronization. To refine the frequency synchronization and thereby arrest the rotation, we apply a second-order phase-locked loop.

Having achieved frequency synchronization, we proceed to symbol synchronization. For this, we pass the signal through a symbol timing recovery loop to align to the pulse apex, then resample to one sample per symbol. We adopted decision-directed approach to symbol synchronization using the Mueller-Muller timing error detection method [ref. 44, Chapter 8]. A preliminary decision on the mth symbol can then be made on each pulse-centered sample. The entire process is summarized by the block diagram in Fig. 3.

Symbol demodulation is preliminary at this stage because it neglects matched filtering to the pulse p(t), which cannot yet be applied because the rolloff factor βr remains unknown. Once the rolloff factor is estimated using the preliminary symbol estimates, as described in the following subsection, a second pass of the process in Fig. 3 is carried out, this time with symbol synchronization and detection aided by matched filtering, which reduces ISI and therefore improves symbol detection accuracy.

The process leading to symbol demodulation requires an entire channel to be present in the data; thus, only our wide captures are suitable. Figure 4 shows the successful result of symbol demodulation with matched filtering to p(t) after determination of βr for 10 μs of data.

Estimation of β r

The rolloff factor βr can be estimated based on the preliminary symbol estimates produced without matched filtering. Only the wide captures are suitable for this, as the narrow captures distort the pulse shape. Let the nth sample after resampling and coarse frequency compensation be denoted \({y}_{s}(n),\,n\in {\mathbb{Z}}\). Suppose we isolate a subset of samples \(\{{y}_{s}(n):n\in {\mathcal{N}}\}\) for a given set \({\mathcal{N}}\) of contiguous indices. Following the steps depicted in Fig. 3, we obtain the preliminary hard-decision demodulated symbols \(\{{\widetilde{a}}_{m}\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}:m\in {\mathcal{M}}\}\), where \({\mathcal{M}}\) is the set of symbol indices corresponding to the sample indices in \({\mathcal{N}}\). We can then generate a local replica l(n; βr), \(n\in {\mathcal{N}}\) of the resampled-and-coarse-frequency-compensated signal by a discrete version of (1) with \({\widetilde{a}}_{m}\) substituted for am, \(m\in {\mathbb{Z}}\), as a function of a candidate rolloff factor βr for p(t). Defining a search space \({\mathcal{B}}\) of possible rolloff factors, we can determine which local replica best matches the original signal. Taking the objective function to be maximized as

Our estimator for βr thus becomes

Figure 5 shows the normalized objective function over βr ∈ [0, 0.25]. The function is maximized for βr ≈ 0.1. Setting \({\mathcal{B}}=\{0.25,0.2,0.15,0.1,0.05\}\), which are the values on this range allowed by the DVB-S2X standard45, an extension of DVB-S2, we conclude that the OneWeb downlink rolloff factor is βr = 0.1.

Estimation of channel center frequencies

OneWeb is authorized to downlink in the 10.7–12.7 GHz Ku band46. Taking into account the 250-MHz channel spacing mentioned in ref. 29 and existing literature showing channelization25, we suppose there are eight channels spaced 250 MHz apart within the 10.7–12.7 GHz band.

For channel center frequency estimation, we follow the same procedure outlined in ref. 4. For this, we exploit a synchronization sequence in the OneWeb signal that will be described later on. The sequence as transmitted repeats once per ms. We estimate the effect of time scaling on the received signal from a series of synchronization sequence time of arrival (TOA) measurements. From (2), one notes that time scaling is only a function of the CFO. From this, we obtain an estimate \(\widehat{\beta }\) of the CFO parameter.

Next, we estimate the same CFO parameter from the exponent in (2) given an a priori estimate of the channel center frequency, denoted \({\overline{F}}_{ci}\). If the prior channel center frequency estimate is correct, then the offset \({\overline{F}}_{ci}-{F}_{cri}\) can be compensated, leaving the CFO as the sole effect on the frequency shift, expressed as Fd. We can estimate the CFO parameter from the frequency shift as \(\overline{\beta }=-{F}_{d}/{\overline{F}}_{ci}\). With the two estimates \(\widehat{\beta }\) and \(\overline{\beta }\), we can then estimate the channel center in MHz as

where rounding to the nearest MHz is justified for the same reasons given in ref. 4.

From this we conclude that the OneWeb downlink channels are centered at Fci = (10.7 + 0.25(i − 0.5))GHz, i = 1, 2, …, 8. These are roughly aligned with Starlink’s channel centers as reported in ref. 4. We only observe activity on channels 2, 3, and 4 over Austin, Texas. The baseband signal model in (1) represents a single channel of the MF-TDMA signal from the transmitter.

Table 1 summarizes the parameter values for the OneWeb Ku-band downlink signal as found by applying the foregoing estimators.

Further system analysis

We can exploit our knowledge of the OneWeb downlink signal parameters and our ability to demodulate the signal to further probe OneWeb’s system behavior and data structure. In particular, we seek answers to the following questions: How are channels mapped to beams? What explains the 10-ms periodicity in OneWeb data noted in earlier studies? What can be revealed about the frame substructure? Do there exist any sequences that are invariant across frames, beams, channels, and satellites, as with Starlink’s PSS and SSS?

Channel activity

Figure 6 shows a composite power spectral density plot of three separate wide captures centered at Fc2, Fc3, and Fc4, showing activity on the three channels. We observe the channels regularly fade in and out of activity over ~20-s windows in such a way that no channel is continuously active. Activity on channels 2 and 4 is synchronous, whereas channel 3 is only active when the other two are not. This behavior is consistent with the spectrogram shown as Fig. 5 in ref. 28. (Note that the channel indexing in ref. 28 starts with what we designate as channel 2.)

Beam patterns

OneWeb downlink signals within a given channel exhibit some patterns that are observable even without knowledge of the signal parameters. One such pattern is the signals’ time-varying power, as shown in the top plot of Fig. 7. This variation in power is a result of the receiver being illuminated by different transmitter beams as the satellite passes overhead. OneWeb satellites can reportedly produce 32 user beams in the Ku-band, half of which are currently active for downlink 47. These beams emanate from the satellite antenna array in a fixed pattern that projects a total footprint of roughly 1080 × 1080 km2 on Earth’s surface. Assuming each of the 16 downlink beams covers approximately the same area, the footprint of each is roughly 68 × 1080 km2.

Top: normalized signal power for a single OneWeb channel. Colors indicate the intervals during which the receiver was within the footprint of an active beam. Bottom Left: Satellite ground track relative to the receiver location (lower vertex of the black triangle). Each arrow shows the movement of the sub-satellite point over the time interval with the corresponding color in the top plot. Thus, when the first recorded beam was passing over the receiver during the interval marked in red in the top plot, the sub-satellite point was entering Oklahoma. Bottom Center: Beam footprints (modeled as rectangular) at the time of the first peak, assuming the receiver is centered latitudinally within the 3rd of 16 beams. Colors indicate correspondence with the signal power time history. Bottom Right: Beam footprints at the time of the second peak, at which point the receiver is centered within the 5th beam. Data are for ONEWEB-0114 from a capture centered at Fc2 taken in March 2024.

Consider the power time history shown in Fig. 7, which lasts about 190 s. As the satellite moves overhead, the receiver is illuminated by successive beams, resulting in a power variation pattern similar to that observed in Fig. 5 of ref. 25. For further analysis, we generate satellite positions using TLE ephemerides and manually align the center of the third beam’s footprint to our receiver location at the moment of the first peak in power (the capture began after the first two beams passed over the receiver’s location). Tracking the beam footprints for subsequent peaks makes it clear that every other beam of the 16 is inactive on a given channel. A reasonable explanation for this observation, and for the alternating channel activity noted above, is that OneWeb’s frequency reuse strategy activates successive beams on different channels. Thus, for the satellite whose data are shown in Fig. 7, one may reasonably assume that channels 2 and 4 are active on beams 1,3,…,15, whereas channel 3 is active on beams 2,4,…,16.

Data patterns across beams

For frames captured within approximately 20 s of each other, we find a repeating pattern of nearly identical demodulated symbols with a 10-ms period. This pattern is consistent with the 10-ms-spaced peaks in the signal’s autocorrelation function noted in ref. 16,25. Such repetition implies a signal with low information content, which is clearly incompatible with a high-rate communication system. We suspect that near our receiver’s location in Austin, Texas, OneWeb currently has few customers, if any, and that, like the DVB-S2 standard, OneWeb’s protocol inserts default physical-layer frames when there is low demand for downlink data.

The 10-ms periodicity is connected to OneWeb’s fixed beams. This can be demonstrated by a narrow capture whose time span is long enough for data from at least two active beams to be present. First, we use TLE ephemerides to eliminate motion-induced CFO effects over the capture, as described in Section IV-B. Next we choose a 10-ms segment from somewhere within the capture. Call this a reference segment. We normalize the reference segment to have unit energy and cross-correlate it against the full capture. The resulting correlation profile reveals that the reference segment is only strongly correlated with an approximately 20-s window of the capture. By selectively choosing the reference segment to maximize the correlation within its window, and repeating this process for various reference segments, we can produce a composite plot like the blue, red, and violet traces shown in Fig. 8. The pattern that emerges matches the power profile over the capture, confirming that each active beam has a unique data pattern, as first reported in ref. 25.

The correlation peaks for reference segments taken at the maximum of each beam are approximately equivalent in magnitude, indicating uniform power across beams. The correlation peak of the gold trace is lower because the overall power of the captured data is reduced at the seam between beams. Data are from ONEWEB-0114 in June 2024.

To appreciate OneWeb’s frequency reuse strategy, consider a reference segment chosen at the moment when the receiver is equidistant from the latitudinal centers of two active beam footprints. If there is significant overlap in the active beam footprints, then this reference segment will be strongly correlated with the unique data pattern associated with both beams, albeit at a lower power for each beam than if it had been chosen at the center of that beam. This is in fact exactly what we observe, as shown by the gold trace in Fig. 8. Clearly, there is considerable overlap between active beams even when only every other beam is active on a given channel. This explains why OneWeb does not allow adjacent beams to be active on the same channel despite such a policy reducing the system’s area spectral efficiency. Each beam pattern would have to be significantly sharper in its power rolloff to allow each beam to carry all channels without significant inter-beam interference.

Frame structure

OneWeb’s simultaneous operation of single-carrier signals in multiple channels constitutes a MF-TDMA scheme. In such schemes, it is typical for a controller to devise a terminal burst time plan (TBTP) to efficiently transmit data to each UT, possibly in response to requests from the UTs on the uplink side. The downlink stream is divided into frames within which each user is assigned one or more time slots to receive data, per the TBTP. Guard intervals filled with predictable data are typically inserted as a preamble within each slot to facilitate slot identification and continual time and frequency synchronization.

The signal demodulation process depicted in Fig. 3, including matched filtering to the SRRC pulse p(t), produces a sequence of symbol estimates. Let \({\widehat{a}}_{m}\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}\) denote the mth symbol estimate for a given satellite, and let \({\boldsymbol{a}}=({\widehat{a}}_{m}:m\in {\mathcal{M}})\) denote the vector of symbol estimates with sequential indices for some set \({\mathcal{M}}\subset {\mathbb{Z}}\) of contiguous indices. By examining such sequences for different \({\mathcal{M}}\) and different satellites, we can identify patterns that reveal the fundamental structure of the OneWeb signal, including repeating sequences.

In view of the strong 10-ms periodicity observed in the estimated symbols across all satellites, we define the frame period Tf to be 10 ms, or Nf = 2304000 symbols. Key questions are the following: (1) Within the same beam, what fraction of the Nf symbols repeat from frame to frame? (2) Are there frame sub-segments that are common across all beams of the same satellite? (3) Are there such sub-segments common across all satellites?

Our approach to addressing these questions proceeds as follows. For a given satellite and beam, we process N frames’ worth of wide-capture samples collected near the latitudinal center of the beam through the decoding pipeline in Fig. 3 to produce a sequence of symbol estimates. One can think of these data as having been collected near one of the peaks shown in Fig. 8. Initially, there is no basis by which to define the beginning of a frame, so we arbitrarily select the first Nf symbols and declare these to be the first frame, etc. Let \({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{n}=({\widehat{a}}_{m}:m\in {{\mathcal{M}}}_{n})\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}^{{N}_{f}}\) denote the vector of estimated symbols over the nth frame, with \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{n}=\{(n-1){N}_{f}+1,(n-1){N}_{f}+2,\ldots ,n{N}_{f}\}\), and let an(m) denote the mth element of an, with \(m\in [1,{N}_{f}]={{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\).

Taking advantage of the strong frame-to-frame correlation evident in Fig. 8, we correlate an, n ∈ {2, 3, …, N} against a1 to verify that the frames are mutually aligned with no extraneous or missing symbols in any frame. We then compute the consensus frame \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{a}}}\in {{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}^{{N}_{f}}\) for the capture, whose mth element \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{a}}}(m)\) is the mode of the set {a1(m), a2(m), …, aN(m)}.

At this point, we can compare each frame symbol-by-symbol against \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{a}}}\). We define the agreement ratio Rm as

where 1(x) is the indicator function, equal to 1 when x is true and otherwise 0. We assume that frames may contain synchronization sequences or default payload data having perfect frame-to-frame agreement. We denote the index set for these by \({\mathcal{S}}\subset {{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\). We further assume that frames may contain payload data, identified by the index set \({\mathcal{P}}\subset {{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\), whose values are independent and uniformly distributed over the domain of am (which is \({{\mathbb{N}}}_{4}\) for QPSK). Finally, we assume that frames may contain intermediate-type data, identified by the index set \({\mathcal{I}}\subset {{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\), that are neither perfectly constant nor perfectly random from frame to frame. We assume these three sets are exhaustive so that \({{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}={\mathcal{S}}\cup {\mathcal{P}}\cup {\mathcal{I}}\).

In a noise-free scenario, Rm = 1 for \(m\in {\mathcal{S}}\), and Rm ≈ 0.25 for \(m\in {\mathcal{P}}\), assuming QPSK modulation and large N. Under the AWGN signal model (2), and assuming large N and perfect phase and symbol synchronization (conditions of coherent detection), Rm ≈ 1 − Pe for \(m\in {\mathcal{S}}\), where Pe is the symbol error rate, which can be calculated based on SNR and Fsym48.

Another useful analytical metric is the frame mismatch rate Mn, or the fraction of symbols in an that fail to match the corresponding symbols in \(\overline{{\boldsymbol{a}}}\):

Figure 9 presents exemplary results for a capture with SNR = 10 dB and N = 100. The top plot indicates near-unity Rm, \(m\in {{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\) except for short bursts spaced by 1 ms during which Rm falls to near 0.25. Each burst lasts approximately 25 μs and contains a 2-μs subinterval over which Rm is again approximately unity. The frame mismatch rate Mn, shown in the bottom plot, hovers around 0.02, meaning that about 98% of the symbols in a contiguous set of frames agree with the consensus frame. This may be compared with Pe = 5.8 × 10−3, the symbol error rate corresponding to SNR = 10 dB under the AWGN model. Clearly, contiguous frames are highly similar, but there exists some systematic disagreement between them that is not due merely to AWGN. Similar results were obtained for other captures analyzed.

Based on these results, we can develop a basic model of OneWeb’s frame structure. According to this model, shown in Fig. 10, a 10-ms frame spans 10 1-ms slots, each consisting of a header and a payload. The header, which corresponds to the 1-ms-spaced intervals of mostly low agreement ratios shown in the top plot of Fig. 9, contains a synchronization sequence and other information unique to each slot. The synchronization sequence occurs at approximately the midpoint of the header and corresponds to the brief 2-μs subinterval over which Rm is approximately unity. The synchronization sequence will be detailed in a later section. The payload typically contains unique downlink data destined to one or more users. But when no active users are present, it is filled with data from a sequence of default payloads.

For further discussion of header and payload properties, it will be convenient to introduce some additional notation. Let hsfbci and psfbci, respectively, be vectors containing the header and payload symbols for slot s of frame f of beam b on channel c of satellite i. Also, let \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{bci}(k)\) be the set of frame indices transmitted by the bth beam on the cth channel of the ith satellite for the kth default payload constancy window, defined as the time interval over which default payload remains constant. The kth default payload \({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{bci}(k)=({{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{1fbci}(k),\,{{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{2fbci}(k),\,\ldots ,\,{{\boldsymbol{p}}}_{10fbci}(k))\) spans a full frame and is identical for all \(f\in {{\mathcal{F}}}_{bci}(k)\). However, the slot-level payloads are different from one another (psfbci(k) ≠ plfbci(k) for s ≠ l). Moreover, the default payload is different from beam to beam (dbci(k) ≠ dlci(k) for b ≠ l), different from channel to channel (dbci(k) ≠ dbli(k) for c ≠ l), and different from one constancy window to another (dbci(k) ≠ dbli(l) for k ≠ l).

Our observation has been that the default payload constancy window lasts approximately one hour. During this time, the default payload for beam b on channel c of satellite i is identical to that for all other satellites on the same beam and channel (dbci(k) = dbcl(k) ≜ dbc(k) for i ≠ l). Our estimate of the default payload constancy window duration was obtained by capturing data from corresponding beams of many satellites over a 2-h interval. Although our antenna can only point to a single satellite at one time, and requires some time to switch between them, we conjecture that each dbc(k) remains constant because it was found to be so for each satellite tracked during the kth window. Three constancy windows were observed during the 2-h interval, two partial and one complete.

Reference 24 exploits the default payload by demodulating only a single frame’s worth of data and using a portion of that as a local replica. This allows TOA and FOA measurements to be made with only a single frame of data per beam.

Synchronization sequence

Discovery of the default payload dbci(k) is significant for opportunistic use of OneWeb signals. When known, it enables long-duration correlation and thus high processing gain. But it must be noted that opportunistic use of the default payload is complicated by the need to re-estimate dbci(k) for each beam b, channel c, satellite i, and constancy window k. Moreover, dbci(k) is only continually present when the OneWeb network is unburdened. In environments where users are highly active, dbci(k) will be only intermittently present or absent altogether.

Thus, it would be of great value to discover a symbol sequence within the OneWeb data that is invariant across slots, frames, beams, channels, and satellites, as is true for Starlink’s PSS and SSS4. Such invariance would make the sequence especially useful for correlation against OneWeb signals in cold-start conditions, and in high-data-rate-demand environments where the default payload is not present. Moreover, it would constitute an unambiguous feature in the OneWeb data stream relative to which an evolving frame structure model could be referenced.

To avoid confusion with the default payload, finding such a sequence requires correlation of frame-length estimated symbol vectors across beams, channels, and satellites. Let \({\overline{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}_{bci}\) be a length-Nf consensus frame for beam b on channel c of satellite i. Circularly correlating this against similar consensus frames from different beams, channels, and satellites reveals peaks spaced by Nf/10 samples, or one slot length. Aligning a large number of diverse consensus frames to the nearest slot and then calculating an agreement ratio Rm, \(m\in {{\mathcal{M}}}_{1}\), what emerges are short 400-symbol (~2-μs) bursts of near-perfect agreement spaced by 1 ms. We call this sequence of symbols the OneWeb synchronization sequence (SS). The SS resides at approximately the midpoint of each slot’s header. In Fig. 9, it is visible in the top panel’s inset as the short subinterval over which Rm ≈ 1.

To verify the SS’s invariance, we correlated it against Doppler-corrected narrow captures that were not involved in its initial identification. The verification data encompassed narrow captures from diverse beams, channels, and satellites across various days in June 2024. In all cases, we found strong correlation against the candidate SS and so consider it verified.

We provide the SS in the form of an 800-bit hexadecimal number qss in which each pair of bits represents a symbol:

Let m ∈ {0, 1, 2, …, Nss − 1} be the symbol index within the SS, where Nss = 400 is the number of symbols. The decimal value am obtained from the hexadecimal sequence is the symbol phase used in (1) to generate a QPSK signal.

The formula in (14) extracts the mth symbol by first dividing qss by 4m so that the desired bit pair occupies the two least significant bits after flooring. Taking the modulo 4 isolates this pair from all others. To ensure proper interpretation of (14), we provide the first eight values of am:

The duration of the SS is Tss = Nss/Fsym = 1.73 μs, and its period is 1 ms. Curiously, we find that symbols at indices m = 10, 25, and 42 at times vary from SS to SS, whereas all others are invariant.

Conclusions

We have presented and applied a blind signal identification process to uncover key parameters in OneWeb’s Ku-band downlink signal. We further identified a synchronization sequence that can be used to passively exploit OneWeb signals for pseudorange-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT), and have proposed a model for the OneWeb frame structure. Moreover, we have discovered that when no active users are present, the OneWeb symbol stream is identical across all satellites for corresponding beams and channels for a period of approximately one hour. The results in this paper illuminate a path to use of OneWeb signals as a backup to traditional GNSS for PNT. Further studies are needed to probe OneWeb’s timing stability and relationship to an absolute time scale such as GPS time.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the enormous size of the data, but are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Kassas, Z. M. Navigation from Low Earth Orbit: Part 2:Models,Implementation, and performance. In Position, Navigation, and Timing Technologies in the 21st Century: Integrated Satellite Navigation, Sensor Systems, and Civil Applications, Vol. 1, 1381–1412 (Wiley-IEEE, 2020).

Iannucci, P. A. & Humphreys, T. E. Fused low-Earth-orbit GNSS. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1–1 (IEEE, 2022).

Psiaki, M. L. Navigation using carrier Doppler shift from a LEO constellation: TRANSIT on steroids. NAVIGATION 68, 621–641 (2021).

Humphreys, T. E., Iannucci, P. A., Komodromos, Z. M. & Graff, A. M. Signal structure of the Starlink Ku-band downlink. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1–16 (IEEE, 2023).

Humphreys, T. E. Interference. In Proc. Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems, 469–503 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Murrian, M. J. et al. First results from three years of GNSS interference monitoring from low Earth orbit. NAVIGATION 68, 673–685 (2021).

Clements, Z., Ellis, P. & Humphreys, T. E. Dual-satellite geolocation of terrestrial GNSS jammers from low Earth orbit. In Proc. IEEE/ION PLANS Meeting, 458–469 (Monterey, 2023).

Workgroup, G. S. GPS spoofing: Final report of the GPS spoofing workgroup. Tech. Rep. OPSGROUP, Tech. Rep., 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ops.group/blog/gps-spoofing-final-report (2024).

Clements, Z. L., Ellis, P. B., Murrian, M. J., Psiaki, M. L. & Humphreys, T. E. Single-satellite-based geolocation of broadcast GNSS spoofers from low Earth orbit. NAVIGATION Submitted for review https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.17791 (2025).

Limited, W. S. Amendment to modification application for U.S. Market Access Grant for the OneWeb Ku- and Ka-Band system. https://licensing.fcc.gov/myibfs/download.do?attachment_key=3495551 SAT-APL-20210112-00007 (2021).

Jardak, N. & Jault, Q. The potential of LEO satellite-based opportunistic navigation for high dynamic applications. Sensors 22, 2541 (2022).

Neinavaie, M., Khalife, J. & Kassas, Z. M. Exploiting Starlink signals for navigation: First results. In Proc. ION GNSS+ Meeting, 2766–2773 (St. Louis, Missouri, 2021).

Neinavaie, M., Khalife, J. & Kassas, Z. M. Acquisition, Doppler tracking, and positioning with Starlink LEO satellites: First results. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58, 2606–2610 (2022).

Khalife, J., Neinavaie, M. & Kassas, Z. M. The first carrier phase tracking and positioning results with Starlink LEO satellite signals. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58, 1487–1491 (2022).

Sallouha, H. et al. On the ground and in the sky: a tutorial on radio localization in ground-air-space networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 27, 218–258 (2025).

Kozhaya, S., Kanj, H. & Kassas, Z. M. Multi-constellation blind beacon estimation, Doppler tracking, and opportunistic positioning with OneWeb, Starlink, Iridium NEXT, and Orbcomm LEO satellites. In Proc. IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), 1184–1195 (IEEE, 2023).

Kassas, Z. M. et al. Navigation with multi-constellation LEO satellite signals of opportunity: Starlink, OneWeb, Orbcomm, and Iridium. In Proc. IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), 338–343 (IEEE, 2023).

Shahcheraghi, S., Saroufim, J. & Kassas, Z. M. Acquisition, Doppler tracking, and differential LEO-aided IMU navigation with uncooperative satellites. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems (IEEE, 2025).

Saroufim, J. & Kassas, Z. M. Ephemeris and timing error disambiguation enabling precise LEO PNT. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems (IEEE, 2025).

Jardak, N., Adam, R. & Jault, Q. Leveraging multi-LEO satellite signals for opportunistic positioning. In Proc. IEEE Access 127100–127114 (IEEE, 2024).

McLemore, B. & Psiaki, M. L. Navigation using Doppler shift from LEO constellations and INS data. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 58, 4295–4314 (2022).

Baron, A., Gurfil, P. & Rotstein, H. Implementation and accuracy of Doppler navigation with LEO satellites. NAVIGATION J. Institute Navigat. 71, navi.649 (2024).

Morgan, S. C. et al. A mock implementation of fused LEO GNSS. In Proc. IEEE/ION PLANS Meeting (Salt Lake City, 2025).

Komodromos, Z. M. et al. Network-aided pseudorange-based LEO PNT from OneWeb. In Proc. IEEE/ION PLANS Meeting (Salt Lake City, 2025).

Kozhaya, S. & Kassas, Z. M. A first look at the OneWeb LEO constellation: Beacons, beams, and positioning. In Proc IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 1–7 (2024).

Blázquez-García, R. et al. Capabilities and challenges of passive radar systems based on broadband low-Earth orbit communication satellites. IET Radar Sonar Navigat. 18 78–92 (2023).

Blázquez-García, R. et al. Experimental comparison of Starlink and OneWeb signals for passive radar. In Proc. IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf23), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Blázquez-García, R. et al. Passive radar imaging based on multistatic combination of Starlink and OneWeb illumination. In Proc. IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf24), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Radio Communications & EMC. OneWeb ow70l UT test report FCC id xxz-intow70ldac. https://fcc.report/FCC-ID/XXZ-INTOW70LDAC/5364479.pdf XXZ-INTOW70LDAC (2021).

Cid, E. L., Sanchez, M. G. & Alejos, A. V. Wideband analysis of the satellite communication channel at Ku-and X-bands. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 65, 2787–2790 (2015).

Hobiger, T., Piester, D. & Baron, P. A correction model of dispersive troposphere delays for the ACES microwave link. Radio Sci. 48, 131–142 (2013).

Lathi, B. & Ding, Z. Modern Digital and Analog Communication Systems. Oxford series in electrical and computer engineering (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Zhao, T. & Huang, T. Cramer-Rao lower bounds for the joint delay-Doppler estimation of an extended target. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 64, 1562–1573 (2016).

Neinavaie, M., Khalife, J. & Kassas, Z. M. Doppler stretch estimation with application to tracking Globalstar satellite signals. In Proc. MILCOM 2021 - 2021 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), 647–651 (IEEE, 2021).

Dobre, O. A. Signal identification for emerging intelligent radios: classical problems and new challenges. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 18, 11–18 (2015).

Sun, H., Zhong, S., Tang, J. & Yuan, J. A blind estimation method of QPSK/OQPSK symbol rate. In Proc. 4th International Conference on Communications, Information System and Computer Engineering (CISCE), 138–141 (IEEE, 2022).

Gardner, W. Exploitation of spectral redundancy in cyclostationary signals. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 8, 14–36 (1991).

Mazet, L. & Loubaton, P. Cyclic correlation based symbol rate estimation. In Proc. Conference Record of the Thirty-Third Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems, and Computers (Cat. No.CH37020) 1008–1012 (IEEE, 1999).

Jin, Y. & Ji, H. Robust symbol rate estimation of PSK signals under the cyclostationary framework. Circuits, Syst., signal Process. 33, 599–612 (2014).

Gardner, W. A. Statistical Spectral Analysis: a Nonprobabilistic theory/by William A. Gardner (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1988).

Nakagawa, T. et al. Non-data-aided wide-range frequency offset estimator for QAM optical coherent receivers. In Proc. Optical Fiber Communication Conference and Exposition and the National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference, 1–3 (IEEE, 2011).

Wang, Y., Shi, K. & Serpedin, E. Non-data-aided feedforward carrier frequency offset estimators for QAM constellations: A nonlinear least-squares approach. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2004, 856139–856139 (2004).

Ciblat, P. & Ghogho, M. Blind NLLS carrier frequency-offset estimation for QAM, PSK, and PAM modulations: performance at low SNR. IEEE Trans. Commun. 54, 1725–1730 (2006).

Rice, M. Digital Communications: A Discrete-time Approach (Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2009).

ETSI. Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Second Generation Framing Structure, Channel Coding and Modulation Systems for Broadcasting, Interactive Services, News Gathering and other broadband satellite applications; Part 2: DVB-S2 Extensions (DVB-S2X). ETSI Standard EN 302 307-2 V1.1.1, European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/302300_302399/30230702/01.01.01_20/en_30230702v010101a.pdf (2014).

Federal Communications Commission. ONEWEB NON-GEOSTATIONARY SATELLITE SYSTEM technical information to supplement Schedule S. https://fcc.report/IBFS/SAT-LOI-20160428-00041/1134939.pdf SAT-APL-20210112-00007 (2017).

Federal Communications Commission. ONEWEB NON-GEOSTATIONARY SATELLITE SYSTEM PHASE 2: MODIFICATION TO AUTHORIZED SYSTEM technical information to supplement Schedule S. https://fcc.report/IBFS/SAT-MPL-20200526-00062/2379706.pdf SAT-MPL-20200526-00062 (2020).

Simon, M. K. & Alouini, M. Digital Communication over Fading Channels, 2 edn. (Wiley, 2005).

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation under Grant 69A3552348327 for the CARMEN+ University Transportation Center and by affiliates of the 6G@UT center within the Wireless Networking and Communications Group at The University of Texas at Austin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.M.K. and T.E.H. jointly wrote the manuscript text. Z.M.K. prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Komodromos, Z.M., Humphreys, T.E. Signal parameter estimation and demodulation of the OneWeb Ku-band downlink. npj Wirel. Technol. 2, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44459-025-00013-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44459-025-00013-y