Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading global cause of mortality and disability, posing a major challenge to human health. Accurate, long-term monitoring of electrophysiological activity in excitable cells such as cardiomyocytes is critical for elucidating disease mechanisms, advancing drug discovery, and evaluating therapeutic efficacy. However, conventional techniques each present key limitations: patch clamp offers high-fidelity signals but is invasive and low-throughput; optical imaging enables parallel measurements but is hindered by phototoxicity and limited temporal resolution; and planar microelectrode arrays support long-term studies but yield only low-fidelity extracellular recordings. To address these trade-offs, three-dimensional bioelectronic interfaces constructed from low-dimensional nanomaterials have recently emerged as powerful tools, providing minimally invasive, high-throughput, high-signal-to-noise intracellular recordings. Among them, one-dimensional nanostructures such as nanowires, nanopillars, and nanotubes offer unique advantages, including tight membrane coupling, tunable physicochemical properties, and compatibility with large-scale microfabrication. This review summarizes bottom-up synthesis strategies for these nanostructures, top-down and hybrid approaches for device integration, multimodal characterization methods, and intracellular access techniques. Finally, we highlight recent advances in cardiac electrophysiology, covering the fundamental principles of action potential generation and network propagation, as well as key applications in drug cardiotoxicity screening and disease modeling. Future directions are also discussed, including integration with complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor technology, development of flexible platforms, and in vivo bioelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a formidable global health challenge1,2. In 2022, they were the leading cause of mortality worldwide and a major contributor to disability, accounting for approximately 19.8 million deaths3. The prevalence of CVDs has nearly doubled over the past two decades, with the burden especially pronounced in middle-income countries4. This global burden continues to increase with population aging and lifestyle-related risk factors such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, unhealthy diets, and air pollution5,6,7,8,9. Drug-induced cardiotoxicity further worsens the problem, representing a major cause of late-stage drug development failures and post-market withdrawals10,11. Although traditional animal models and ex vivo preparations have yielded valuable insights, inherent limitations, including interspecies physiological differences, high costs, and low throughput, underscore the urgent need for robust in vitro platforms that can accurately recapitulate human cardiac physiology. At the cellular level, many CVDs, including various forms of arrhythmia, are closely linked to abnormal electrical activity in cardiomyocytes12. The transmembrane action potential (AP) waveform, precisely shaped by the coordinated function of key ion channels (e.g., Na+, Ca2+, and K+), serves as a highly sensitive and information-rich readout of cellular excitability, conduction, and arrhythmogenesis13,14. Consequently, the development of platforms capable of precise, long-term, and high-throughput electrophysiological recording is critical for elucidating disease mechanisms, predicting drug responses, and advancing personalized medicine15.

At present, several conventional methods are available for cellular electrophysiology, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The patch-clamp technique, widely regarded as the “gold standard,” enables direct measurement of intracellular APs with exceptional fidelity16,17,18,19,20,21. However, it is invasive, technically demanding, and inherently low throughput; even automated systems often require cell suspension, which disrupts the native cardiomyocyte syncytium and may compromise physiologically relevant measurements. Optical imaging techniques offer a noninvasive, high-throughput alternative that allows parallel recording22,23,24,25,26. Despite their utility, these methods are limited by phototoxicity, marker interference, and the restricted temporal resolution imposed by the on/off kinetics of fluorescent probes, making it difficult to capture the rapid dynamics of an AP. Planar microelectrode arrays (MEAs) provide another noninvasive, label-free platform suitable for long-term monitoring27,28,29. Weak coupling between the electrode and the cell membrane limits detection to low-amplitude extracellular field potentials. These signals lack essential subthreshold and morphological characteristics of the true transmembrane action potential, including the resting potential and plateau phases. The problem is further compounded by the mechanical mismatch between rigid electrode materials and soft cardiac tissue30. Consequently, a long-standing trade-off persists among the precision of patch clamp, the throughput of optical imaging, and the stability of MEAs.

In recent years, rapid advances in nano-bioelectronics have opened new avenues for overcoming these limitations, with low-dimensional nanomaterials playing a central role31,32,33. Among them, one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures such as nanowires, nanopillars, and nanotubes have shown particular promise34,35,36,37,38. Their nanoscale diameters and high aspect ratios enable intimate contact with the cell membrane, while tunable surface chemistry enhances biocompatibility and functional coupling39,40,41. Unlike conventional planar electrodes, these vertically oriented 1D nanostructures form three-dimensional (3D) interfaces with cells, inducing membrane wrapping that markedly increases the seal resistance at the electrode–cell junction. This wrapping phenomenon is driven by cell adhesion forces, where the cell membrane minimizes its free energy by maximizing contact with the high-curvature nanostructure. The resulting tight engulfment creates a long and tortuous ionic pathway between the electrode surface and the bulk extracellular medium, which significantly increases the electrical resistance of this junction (i.e., the seal resistance). A high seal resistance is critical as it electrically isolates the recording site, minimizing signal shunting and thereby enabling the detection of small intracellular potential changes with a high signal-to-noise ratio. This enhanced coupling substantially improves signal detection sensitivity, enabling high-fidelity intracellular potential recordings while preserving cell viability.

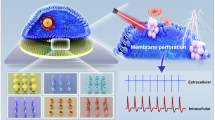

Notably, recent studies demonstrate that when integrated into array platforms, nanoelectrodes can capture intracellular AP waveforms with fidelity approaching that of patch clamp, while maintaining high-throughput recording capabilities42,43. Importantly, these intracellular recordings provide access to the full action potential waveform, including resting potential, subthreshold dynamics, and precise repolarization kinetics, which are largely absent in extracellular signals and essential for accurately assessing ion channel function and proarrhythmic risk. Moreover, when applied to human-derived cells, these platforms offer a high-throughput alternative to animal models, avoiding interspecies differences and enabling mechanistic studies at the single-cell level. Based on these advances, the value of low-dimensional nanomaterials in cellular electrophysiology is increasingly evident, as their nanoscale geometries, tunable physicochemical properties, and compatibility with microfabrication techniques create unique opportunities for minimally invasive, high-throughput, and long-term intracellular recording (Fig. 1).

The central schematic illustrates the critical cell–electrode interface, wherein 3D nanoelectrodes achieve intimate coupling with cells to enable high-fidelity recording. The pipeline begins with the synthesis of diverse low-dimensional materials that serve as core functional units, including iridium oxide (IrOx) nanotubes75, kinked nanowires58, silicon (Si) nanowires65, nanobranches77, nanotemplate electrodes76, and nanocrown electrodes101. These materials are subsequently integrated into devices using top-down or hybrid fabrication strategies, such as 3D flexible nanoscale field-effect transistors (FETs)58, vertical nanowire electrode arrays65, CMOS nanoelectrode arrays (NEAs)102, 3D transistor arrays70, nanotemplate electrode arrays76, and nanocrown devices43. To ensure reliable performance, these platforms undergo comprehensive characterization and employ strategies for intracellular access, including spontaneous internalization, electroporation, and optoporation. Collectively, these advances have culminated in powerful biomedical applications, particularly in drug screening and disease modeling

This review provides a systematic overview of recent advances in this rapidly evolving field. We begin by outlining the “bottom-up” synthesis of key 1D nanostructures, followed by a discussion of “top-down” and “hybrid” fabrication strategies for their integration into functional 3D devices. We then describe essential approaches for multimodal device characterization and review the primary methods for achieving intracellular access. Based on this technical foundation, we summarize the principles of cardiac electrophysiology and network activity and highlight major applications in drug screening and disease modeling. Finally, we conclude with perspectives on future directions, including complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) integration, flexible platforms, and in vivo bioelectronics.

Synthesis strategies for low-dimensional materials used in electrophysiology

Bottom-up synthesis represents a foundational approach for constructing the core functional units of electrophysiological sensors at the atomic or molecular level32. These strategies enable the controlled “growth” of nanomaterials with defined dimensions, morphologies, and functionalities through precise regulation of chemical reactions44. Low-dimensional materials for high-performance bioelectronic interfaces are most commonly produced via two principal technological pathways: vapor-phase synthesis and solution-phase synthesis. The fundamental principles of these approaches are illustrated in Fig. 2.

a Vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) growth of Si nanowires, where a gold (Au) catalyst particle mediates Si deposition from a gaseous precursor. b Chemical vapor deposition for carbon nanotube growth, in which a catalyst on a substrate directs decomposition of a carbon source into a nanotube103. c Electrochemical deposition, showing the reduction of metal ions from an electrolyte solution onto an electrode within a porous membrane104. d Atomic layer deposition (ALD), illustrating the sequential pulsing of precursor gases into a reaction chamber for conformal thin-film deposition105. e Hydrothermal synthesis, depicting the growth of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanostructures under elevated temperature and pressure in an aqueous solution containing zinc precursors. Collectively, these methods enable precise control over the dimensionality, morphology, and composition of nanomaterials, which is critical for fabricating high-performance electrophysiological interfaces106

Vapor-phase synthesis approaches

Vapor-phase synthesis methods utilize gaseous precursors, typically at high temperatures and in specific atmospheres, for material growth45,46,47,48,49,50. These methods can produce high-purity, high-quality crystalline nanostructures; therefore, they are crucial for fabricating active devices and high-performance conductive networks requiring excellent electronic properties34,51,52,53,54.

VLS is the dominant technique for growing single-crystal 1D nanowires55,56. The process begins with the dispersion of metal nanoparticles, such as Au, on a substrate to act as catalysts. When a vapor-phase semiconductor precursor (e.g., silane gas) is introduced at high temperatures, the metal nanoparticles form liquid eutectic alloy droplets, which serve as a preferential site for the absorption and decomposition of the precursor gas. As the concentration of the semiconductor element reaches supersaturation within a droplet, it precipitates out at the liquid–solid interface, leading to the unidirectional, epitaxial growth of a single-crystal nanowire57. The VLS method offers a high degree of process control: the diameter of the nanowires is precisely determined by the size of the initial catalyst nanoparticle, their length is controlled by the growth duration, and their electronic properties can be modulated in real time by introducing dopant gases during the synthesis. Owing to this precise controllability, the VLS method is essential for synthesizing structures such as 1D Si nanowires, which are the core functional units in active FET probes42,58.

Another key vapor-phase technique is chemical vapor deposition, which provides a highly versatile synthesis platform consisting of the deposition of a solid material, typically a high-quality thin film or nanostructure, via the reaction of one or more gaseous precursors on a heated substrate surface. By precisely controlling parameters such as temperature, chamber pressure, and gas flow rates and ratios, the crystalline quality, thickness, and morphology of the final product can be effectively regulated. In the fabrication of electrophysiology devices, chemical vapor deposition is primarily used to synthesize two-dimensional (2D) graphene for transparent MEAs or 1D carbon nanotubes that can form compliant, porous interfaces59. A key variant is plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD), which operates at lower temperatures than conventional thermal chemical vapor deposition and is therefore more compatible with device fabrication processes that use temperature-sensitive substrates. Other vapor-phase techniques, such as metal–organic vapor-phase epitaxy, are also employed for fabricating complex semiconductor heterostructures; however, they involve more hazardous precursors.

Solution-phase- and template-assisted synthesis approaches

Contrary to vapor-phase methods that typically require high temperatures and vacuum environments, solution-phase synthesis employs wet-chemical processes conducted in liquid media. These approaches are distinguished by milder reaction conditions, cost-effectiveness, and methodological diversity. They offer unique advantages, particularly through the use of templates for precise morphological control, and are widely adopted for fabricating functional passive electrodes and high-surface-area interfaces.

Template-assisted electrochemical deposition is a representative solution-phase technique. It employs an insulating template with a regular nanoporous structure, such as anodized aluminum oxide or a polymer mold defined by photolithography, as a scaffold for material growth. The template is placed on a conductive substrate and immersed in an electrolyte solution containing the target ions. Upon application of an electric field, the ions are reduced and deposited within the template nanochannels, forming highly ordered arrays of solid nanopillars or hollow nanotubes. This approach is widely used to fabricate high-surface-area passive electrodes, such as arrays of IrOx nanotubes, which are particularly well suited for long-term intracellular recording.

Similarly, template-assisted ALD leverages the structural guidance of a template. ALD is a vapor-phase technique based on self-limiting, sequential surface reactions that deposit material one atomic layer at a time. Its primary advantage lies in the ability to create highly uniform, conformal films with atomic-level thickness control on complex surfaces60,61. When combined with a template, ALD precursor gases can penetrate deep pores and deposit layer by layer along the inner walls, yielding nanotube arrays with precisely defined wall thickness after template removal. This level of precision provides new opportunities for advanced electrode interface design.

Furthermore, hydrothermal synthesis is an important solution-phase technique. It involves producing crystalline materials from an aqueous solution in a sealed vessel (autoclave) heated above the normal boiling point. The elevated temperature and corresponding autogenous pressure enhance the solubility and reactivity of reactants, thereby facilitating crystal nucleation and growth. This method offers an efficient and cost-effective approach for directly growing high-surface-area 3D interfaces on patterned substrates, such as ZnO nanostructures, for sensing applications. The resulting high-density 3D architectures are particularly advantageous for fabricating electrodes with a large effective surface area, which reduces electrode impedance and improves the signal-to-noise ratio during recordings.

Fabrication strategies for 3D nanoelectronic devices

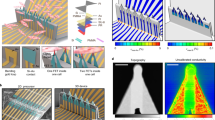

The successful application of low-dimensional nanomaterials requires their integration into robust, scalable, and functional device platforms. A key architectural feature in this field is the fabrication of 3D topographies, which establish a nonplanar, spatially complex interface with the cell membrane to promote the tight coupling that enables a high-fidelity recording. To contextualize these fabrication routes, it is important to compare their underlying material synthesis philosophies and associated trade-offs. Bottom-up strategies provide precise control over nanomaterial dimensions, morphologies, and functionalities at the atomic or molecular scale. For instance, VLS growth produces high-purity, single-crystal 1D nanowires with tunable diameters, lengths, and electronic properties, ideal for constructing the core functional units of high-performance FET probes, although their large-scale integration and compatibility with standard microelectronics remain challenging. In contrast, top-down methods fabricate nanostructures by selectively removing material from a bulk substrate. They are fully compatible with conventional semiconductor processes, provide excellent mechanical stability and wafer-scale reproducibility, and are suitable for large-scale integration, although they typically offer lower crystal quality and less defect control compared with bottom-up approaches. Hybrid strategies combine the advantages of both approaches, harnessing the superior material properties of bottom-up synthesis while retaining the patterning precision and scalability of top-down methods, enabling diverse 3D nanoelectrode architectures with enhanced device performance. This chapter details the primary manufacturing paradigms for these 3D devices, which are broadly categorized into top-down subtractive fabrication (Fig. 3) and hybrid strategies combining multiple techniques (Fig. 4).

a Fabrication of vertical Si nanowires65. The process flow shows the key steps, including reactive ion etching (RIE) of an Si-on-insulator (SOI) wafer to form Si cores, followed by thermal oxidation for insulation and metal cap deposition. b Fabrication of nanovolcanoes66 via ion beam etching redeposition of a material sputtered from the bottom of the photoresist openings on the sidewalls to build the hollow structure. c Fabrication of nanocrowns43,101. This multistep process involves the formation of solid SiO2 pillars, conformal deposition of conductive/insulating layers, directional dry etching of the tip, and final selective wet etching of the core to create the semi-hollow crown structure

a Fabrication of kinked nanowire probes: Using a series of top-down lithography steps, a presynthesized (bottom-up) kinked Si nanowire is integrated into a flexible probe body composed of metal interconnects and a polymer58. b Fabrication of IrOx nanotubes: A nanohole template defined by top-down lithography is used to guide the bottom-up electrochemical deposition of IrOx into a tubular structure75. c Fabrication of nanotemplate electrodes using a poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) template: Using a prefabricated porous PET membrane as a scaffold, combining bottom-up ALD coating with top-down conventional microfabrication affords a vertical electrode array76. d Fabrication of nanobranch electrodes: A ZnO seed layer region is defined by top-down lithography, followed by the selective, bottom-up hydrothermal growth of nanobranches in that area77

Top-down fabrication

The top-down approach is a subtractive process in which nanostructures are fabricated via the selective removal of a material from a bulk substrate. This strategy is highly compatible with standard semiconductor manufacturing processes, affording high mechanical stability and wafer-scale reproducibility62,63,64. The fabrication of vertical nanoelectrodes using this route typically involves a sequence of high-resolution lithography and anisotropic etching, as illustrated for three representative geometries in Fig. 3.

Solid vertical nanowires are essential 3D structures that can be fabricated using this method (Fig. 3a)65. The process, which is typically performed on an SOI wafer, begins by defining an array of nanopores in a polymethyl methacrylate resist via electron beam lithography (EBL), followed by the fabrication of an array of alumina (Al2O3) nanodisks via evaporation and liftoff. These disks serve as a hard mask for the subsequent etching. Next, the top Si layer is vertically etched via RIE, forming micron-tall Si pillars. A key step is the precise thinning of these pillars down to the final desired nanoscale diameter using a combination of thermal oxidation and wet-chemical etching. After thinning, a final thermal oxidation step is performed to grow an insulating silicon dioxide (SiO2) shell on the nanowire surface. To selectively metallize the tips, a thin layer of photoresist is spun onto protect the nanowire sidewalls while leaving only the tips exposed. After stripping the oxide from the tips, multilayer metals such as titanium (Ti)/Au are sputtered to form the conductive electrode caps.

Nanovolcano electrodes are fabricated using a unique top-down process involving an ion beam etching redeposition mechanism (Fig. 3b)66,67,68. The process begins with standard photolithography to pattern micron-scale circular openings in a photoresist layer on a multilayered substrate (e.g., Ti–platinum (Pt)-Ti-Au-Ti-SiO2). An argon ion beam is then used to vertically bombard and etch the substrate exposed at the bottom of these openings. During this process, the material sputtered from the substrate is redeposited onto the photoresist sidewalls, building up the hollow volcano structure layer by layer. Finally, freestanding nanovolcano structures are obtained by stripping the photoresist.

Nanocrown electrodes, which exhibit a more complex, semi-hollow geometry, are also produced via a top-down strategy but using a more intricate multistep etching process (Fig. 3c)43,69. First, solid, tapered SiO2 micropillars are fabricated on a quartz substrate using dry and wet etching. Then, conductive (Pt) and insulating (SiO2/Si3N4) layers are conformally deposited, encapsulating the entire pillar. A critical step is the directional dry etching to precisely remove the coatings from the very tip of the pillar, exposing the inner SiO2 core. Finally, time-controlled selective wet etching removes a portion of the exposed SiO2 core, creating the final, hollow-tipped crown structure.

Hybrid Fabrication

The hybrid strategy, which synergistically combines bottom-up material synthesis with top-down microfabrication, has provided access to diverse device architectures (Fig. 4). By harnessing the superior material properties afforded by bottom-up growth (e.g., single crystallinity) while retaining the patterning precision and scalability of conventional top-down methods70,71,72,73, this approach has furnished a variety of 3D nanoelectrodes with novel structures and enhanced performance.

The most sophisticated strategy of this type is the integration of presynthesized components, which is exemplified by the fabrication of kinked nanowire FET probes (Fig. 4a)58,74. This process begins with the bottom-up synthesis of single-crystal Si nanowires with a specific kinked geometry. These high-performance nanowire components are then transferred to a substrate containing a sacrificial layer. A series of complex, multistep top-down photolithography processes is subsequently performed to precisely define metal interconnects and a flexible polymer (SU-8) support arm. Finally, the entire probe structure is released by removing the sacrificial layer and then assembled onto a macroscopic connector. Although complex, this method masterfully combines the excellent electrical properties of single-crystal semiconductor nanowires with the practical usability of macroscopic devices.

A more common hybrid approach is template-assisted growth75. The fabrication of IrOx nanotubes is a classic example (Fig. 4b). In this case, top-down electron beam lithography is first used to define a nanohole array in an insulating layer, which serves as a template. Subsequently, a bottom-up approach involving electrochemical deposition is conducted to selectively grow hollow IrOx nanotubes within the nanoholes to form a vertical array.

Figure 4c shows the fabrication of nanotemplate electrodes using a porous PET template as another example of a unique template-based method using a prefabricated porous structure76. First, the bottom-up ALD technique is adopted to conformally grow an Al2O3 nanotube layer within the pores of the PET template. Subsequently, a series of top-down steps including etching, photolithography, metal deposition, and insulation layer encapsulation afford the final functional vertical electrode array.

Seed-layer-directed growth is another variation of the template-based method. For example, in the fabrication of nanobranch electrodes (Fig. 4d)77,78, a top-down process involving photolithography and sputtering is first used to define a patterned ZnO seed layer on the substrate. Then, using a bottom-up hydrothermal method, ZnO nanobranches are selectively grown from this seed layer. Finally, the device fabrication is completed using standard top-down processes such as photolithography, metal deposition, and insulation patterning.

Collectively, these hybrid strategies illustrate the power of combining atomic-level material control with top-down spatial precision. Such approaches enable versatile 3D nanoelectrode architectures that balance electrical performance, structural integrity, and scalability, offering a viable path toward next-generation intracellular bioelectronic interfaces. To facilitate a more intuitive comparison across these diverse 3D nanoelectronic platforms, Table 1 summarizes their representative fabrication routes, intracellular access mechanisms, and recording performance. The comparison highlights how different fabrication philosophies translate into distinct signal characteristics and cellular compatibilities.

Device Characterization and Intracellular Access Strategies

The transition of 3D bioelectronic devices based on low-dimensional materials from laboratory prototypes to reliable tools for cellular electrophysiology requires two critical steps: (i) comprehensive performance characterization of the devices and (ii) adoption of efficient, minimally invasive intracellular access strategies. Characterization is essential for ensuring structural precision and performance reliability, validating each stage from material synthesis to device integration. Intracellular access strategies are equally vital, as they determine whether a stable electrical pathway to the cell interior can be established without significantly disrupting normal physiological activity. Achieving such access is central to obtaining high-signal-to-noise intracellular recordings. This section first outlines multimodal methods for characterizing advanced devices, followed by a discussion of cutting-edge intracellular access techniques, encompassing both physical and biochemical approaches.

Device characterization

Device characterization begins with the most fundamental parameters: structure and composition. Precise morphology and chemical composition form the basis of performance. High-resolution imaging of nanostructure dimensions and architecture can be achieved using scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), often combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) or Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) for elemental analysis. For example, AES has confirmed that IrOx nanotubes consist of iridium and oxygen, with elemental line-scan data clearly revealing their hollow tubular geometry in contrast to solid Au nanopillars (Fig. 5a)75. In more complex devices such as “nanovolcano” electrodes, combined TEM–EDX enables precise resolution of the multilayer material stack (Au/Si/Ti/O, etc.) within cross-sections, thereby verifying the reproducibility and controllability of the fabrication process (Fig. 5b)66.

a Elemental and structural analysis of IrOx nanotubes. Left: AES confirms the presence of Ir and O. Right: Elemental line-scan data reveal the hollow tubular structure75. b Cross-sectional compositional analysis of a nanovolcano electrode66. TEM combined with EDX resolves the precise multilayer stack of materials (Au, Si, Ti, O, etc.). c Electrochemical performance comparison of IrOx nanotubes and Au nanopillars. Left: Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) shows lower impedance in IrOx nanotubes. Right: Cyclic voltammetry (CV) demonstrates their higher charge storage capacity75. d Comparison of EIS across electrodes with different morphologies. 3D structured electrodes, such as Al2O3 nanotemplates and ZnO nanorods, exhibit reduced interface impedance compared with planar electrodes76. e Functional characterization of a 3D flexible FET probe58. Top: Conductance and sensitivity remain stable under mechanical deflection. Bottom: Potential response to pH changes demonstrates its chemical sensing capability. f Electrical characterization of U-shaped nanowire FET (U-NWFET) probes42. Current–voltage (I–V) curves for devices with three different channel lengths (~50, ~500, and ~2000 nm) confirm reliable transistor performance

Next, the electrochemical performance of the device in a physiological environment is evaluated, as this directly determines the quality of the recorded biological signals. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is a key technique for assessing the electrode–electrolyte interface. Lower impedance reduces thermal noise, which is the dominant source of baseline fluctuation in electrophysiological recordings. This directly improves the signal-to-noise ratio and enables faithful resolution of subtle features within the action potential waveform, such as depolarization rate and plateau duration. Studies have shown that IrOx nanotubes exhibit an order of magnitude lower impedance than Au nanopillars of comparable surface area (Fig. 5c)75. Electrode geometry also plays a significant role; relative to planar electrodes, 3D structures such as Al2O3 nanotemplates and ZnO nanorods display markedly reduced impedance due to their larger effective surface area (Fig. 5d)76. Similarly, electrodes fabricated from a porous network of carbon nanotubes leverage a high effective surface area to achieve low impedance, enabling high-sensitivity recording of extracellular potentials from cardiomyocytes79. Additionally, cyclic voltammetry (CV) is used to determine the charge storage capacity (CSC), a parameter that quantifies the total charge the electrode can safely inject. A high CSC is particularly advantageous for applications requiring electrical stimulation, such as pacing cardiomyocytes or triggering network activity. It allows for the delivery of effective stimulus currents with smaller, safer voltage transients, which minimizes the risk of irreversible electrochemical reactions and potential cell damage.

Finally, specialized functional characterization is essential for specific device designs. For FET-based probes, validation of their core sensing function is critical. For instance, characterization of a 3D flexible FET probe demonstrates that its conductance and sensitivity remain stable under substantial mechanical deflections, highlighting its suitability for interfacing with soft biological tissues. The same probe also exhibits near-Nernstian sensitivity to changes in solution pH, underscoring its potential for multimodal sensing (Fig. 5e)58. In another example, electrical measurements of U-NWFETs confirm reliable transistor performance. Their I–V curves reveal an inverse relationship between conductance and channel length, indicating that the device’s electrical properties are both predictable and tunable (Fig. 5f)42.

Beyond electrochemical and functional performance, biosafety is a fundamental prerequisite for applying these devices in cellular electrophysiology. The nanoscale dimensions of the probes inherently minimize invasiveness and mechanical perturbation to the cell membrane. Structural integrity remains central to all fabrication strategies. For top-down devices, this is achieved through their monolithic architecture, in which nanostructures are covalently bonded to the substrate. In hybrid architectures incorporating bottom-up nanostructures, stability arises from strong interfacial adhesion formed during synthesis and mechanical immobilization achieved during integration, typically embedding the nanostructures within a solid dielectric matrix and making them inseparable from the device framework. Materials such as silicon, noble metals, and stable oxides are employed for their well-established biocompatibility and chemical inertness. Collectively, these design principles ensure a stable, biocompatible interface, as demonstrated by the ability to maintain high-fidelity intracellular recordings from the same cells over extended periods. However, the translation of these devices to in vivo applications will require continued evaluation of long-term tissue compatibility, including potential inflammatory and immune responses.

Intracellular access strategies

Once a device has been comprehensively characterized and its performance validated, the next major challenge is to employ nanostructures to penetrate the cell membrane and establish a stable, low-impedance electrical interface with the cell interior. An ideal intracellular access strategy should be minimally invasive, highly efficient, and controllable, and cause minimal disruption to normal physiological activity. Current approaches can be broadly categorized into three groups: (i) chemically induced membrane fusion or spontaneous internalization, driven by direct interactions between nanostructures and the cell membrane; (ii) electroporation, which employs localized electric fields; and (iii) optoporation, which leverages photothermal or photomechanical effects.

Chemically induced membrane fusion or spontaneous internalization is a passive, trigger-free access method regarded as the least invasive strategy42,58,71,74. Its effectiveness depends primarily on two factors: nanoprobe geometry and surface biofunctionalization. A very small radius of curvature (typically tens to hundreds of nanometers) can generate high local membrane curvature, thereby activating endogenous internalization pathways such as endocytosis. In parallel, coating the probe surface with a phospholipid bilayer mimics the biochemical properties of the cell membrane, promoting fusion between the probe and the cell. For instance, V- or U-shaped nanowire transistor probes functionalized with phospholipids can spontaneously penetrate the cell interior and stably record intracellular APs with near-full amplitudes (Fig. 6a, b)42,58. By mimicking the natural cell–membrane interface, this strategy encourages active probe uptake, minimizing both physical damage and physiological disruption. However, this approach is still limited by low efficiency and reproducibility, as spontaneous penetration events are often rare and transient.

a Schematic of spontaneous internalization of a phospholipid-coated V-shaped nanowire FET probe and its corresponding intracellular signal recording58. b Geometry-assisted spontaneous internalization of a U-NWFET, illustrating the transition from extracellular to intracellular signals42. c Electroporation with vertical nanopillars, showing a marked increase in signal amplitude following poration80. d Electroporation with nanobranched electrodes, enabling a recording mode switch from extracellular (blue) to intracellular (red)77. e Optoporation using 3D plasmonic nanoelectrodes to achieve intracellular signal recordings81. f Optoacoustic poration with a planar plasmonic “meta-electrode,” enabling intracellular signal acquisition82

Electroporation is one of the most widely used physical methods for membrane permeabilization83,84,85,86. It involves applying a series of brief voltage pulses (typically a few volts) through a nanoelectrode, generating a highly localized electric field in the narrow gap between the electrode tip and the cell membrane43,75,77,80,87,88,89,90. This intense field creates transient, reversible nanopores in the membrane, thereby establishing an electrical pathway between the intracellular and extracellular environments. For instance, studies using vertical nanopillar arrays have shown that following voltage pulsing, the recording mode can be switched from low-amplitude extracellular signals (Fig. 6c, top) to high-amplitude intracellular APs with clear waveforms and nearly a 100-fold increase in signal amplitude (Fig. 6c, bottom)80. Similarly, 3D nanobranched electrodes employ the same principle to transition from extracellular to intracellular recording via local electroporation, yielding high-quality AP signals (Fig. 6d)89. Electroporation has been widely adopted due to its straightforward operation and high success rate. However, the applied voltage pulses can generate electrical artifacts that temporarily saturate the amplifier, and intracellular access is inherently limited by membrane resealing. The duration and stability of access vary with cell type and pulse parameters, typically allowing high-fidelity recordings for several minutes to up to two hours before reverting to extracellular-like potentials.

Optoporation offers a gentler and more targeted approach for accessing the cell interior. It relies on focused laser pulses to excite the plasmonic resonance of nanostructures81,82,91,92,93. In 3D plasmonic nanoelectrodes, laser energy is concentrated at the electrode tip, producing localized photothermal, photomechanical (e.g., nanoshockwaves), or nonlinear effects (e.g., nanosecond-scale bubbles) that generate precise pores in the adjacent cell membrane. A major advantage of this method is that it decouples the poration trigger (light) from the electrical recording, thereby avoiding the strong electrical artifacts and amplifier saturation often associated with electroporation. As demonstrated in Fig. 6e, laser irradiation enables a smooth transition from weak extracellular spikes to intracellular signals with characteristic AP morphology81. Further development of this strategy has introduced the concept of planar plasmonic “meta-electrodes.” In this design, protruding 3D structures are unnecessary; instead, a nanoporous layer (e.g., porous platinum) deposited on planar CMOS electrodes achieves poration via a laser-induced optoacoustic effect, allowing clear intracellular recordings of cardiomyocyte APs (Fig. 6f)82. Despite its advantages, the requirement for complex and costly optical systems still limits its scalability.

In summary, the three main intracellular access strategies present distinct trade-offs. Spontaneous internalization offers minimally invasive, long-term recordings but suffers from low efficiency and reproducibility. Electroporation provides high-amplitude, scalable intracellular signals yet introduces transient electrical artifacts and is limited by membrane resealing. Optoporation enables artifact-free, targeted recordings with potentially lower invasiveness, though throughput and system complexity constrain widespread adoption. Strategy selection depends on experimental priorities, and future directions may focus on integrating electrical and optical approaches or automating optical delivery to achieve both high-throughput and minimally invasive intracellular recordings.

Principles and advanced applications in cardiac electrophysiology

The electrophysiological activity of cardiomyocytes, particularly their transmembrane AP, serves as a key biomarker of cardiac health. The distinctive AP waveform reflects the coordinated function of multiple ion channels, and even subtle morphological changes can indicate a potential proarrhythmic risk. Accordingly, this section first elucidates the mechanisms underlying AP generation and its propagation across cardiomyocyte networks, establishing the theoretical basis for subsequent discussions. Based on this foundation, we then examine advanced applications of 3D nanoelectronic devices in drug screening and disease modeling.

Principles of cardiac electrophysiology and cell network activity

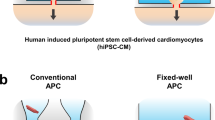

The pumping function of the heart results from the precise spatiotemporal coordination of its electrical activity, which is based on the electro-excitability of individual cardiomyocytes and their ordered propagation at the tissue level. At the single-cell level, the core of this activity is the transmembrane AP, a rapid and reversible change in membrane potential driven by ion concentration gradients across the plasma membrane94,95,96,97. The typical AP waveform of a working ventricular cardiomyocyte consists of five distinct phases (0–4), whose morphology is precisely regulated by the sequential opening and closing of voltage-gated ion channels, including Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels (Fig. 7a). For example, the rapid depolarization of phase 0 results from the large-scale opening of Na+ channels, while the plateau of phase 2 reflects a dynamic equilibrium between Ca2+ influx and K+ efflux. At the tissue level, cardiomyocytes form a functional syncytium through electrical coupling via gap junctions. This allows signals initiated in one cell to propagate rapidly and with low resistance to neighboring cells. This creates a coordinated wave of excitation that synchronizes contraction across the heart, thereby maintaining normal rhythm. Recent advances in low-dimensional nanomaterials and 3D MEA technologies now allow precise recording and monitoring of cardiomyocyte electrical activity, providing new insights into how excitation propagates within cell networks. These platforms facilitate the formation of tightly coupled cardiomyocyte monolayers on 3D substrates, offering ideal experimental conditions for multiscale electrophysiological research (Fig. 7b)98. Although Fig. 7b shows a neuron network cultured on a 3D NEA, similar architectures have been successfully applied to cardiomyocyte networks for monitoring collective electrical activity. Using such systems, researchers can monitor cell network electrical activity in a long-term, noninvasive manner, generating reliable data to support cardiac disease modeling.

a Schematic of the fundamental principles of cardiac electrophysiology, showing a typical cardiomyocyte AP and its five distinct phases (0–4) driven by the transmembrane flow of key ions (Na+, Ca2+, and K+) through their respective channels. b Scanning electron micrograph of a neuron network cultured on a 3D NEA98. c Application of nanopillar electrodes in drug screening, showing the shortening and prolongation of intracellularly recorded AP duration (APD) after administration of nifedipine and tetraethylammonium (TEA), respectively80. d Dose-dependent effects of verapamil on APs recorded using hollow nanopillars89. e Use of nanocrown electrodes for multidose drug evaluation, showing distinct AP waveform changes for drugs with different cardiotoxicity risks43. f Application of nanopillars in disease modeling of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), comparing AP recordings from a healthy individual and HCM patient–derived human induced pluripotent stem cell–cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs)99. g A heart-on-a-chip model with integrated nanopillars for studying hypoxia, comparing AP signals under normoxic and hypoxic conditions100

Drug screening

Drug-induced cardiotoxicity is a leading cause of both new drug failures and post-market withdrawals, with toxic effects often manifesting as alterations in cardiomyocyte AP morphology. 3D nanoelectronic platforms provide physiologically relevant and scalable in vitro models for preclinical drug safety screening87. A key advantage of these systems is their ability to perform “self-referencing” measurements on the same cell before and after drug administration, enabling precise assessment of drug effects while eliminating intercellular variability. For example, nanopillar electrodes yield high-quality intracellular recordings that can clearly distinguish APD shortening caused by Ca2+ channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine) from APD prolongation induced by K+ channel blockers (e.g., TEA) (Fig. 7c)80.

Hollow nanopillars further enable monitoring of dose-dependent effects, such as the APD changes produced by different concentrations of verapamil (Fig. 7d)89. More recently, advanced nanocrown electrodes, with >99% success rates for intracellular access and excellent recording stability, have facilitated parallel screening of compound panels with varying proarrhythmic risk levels43,101. As illustrated in Fig. 7e, this technology can detect pronounced APD prolongation induced by high-risk drugs (e.g., dofetilide), APD shortening by low-risk drugs (e.g., nifedipine), and even early afterdepolarization-like–like events triggered by intermediate-risk drugs (e.g., cisapride). In addition to passive electrode arrays, active devices based on 3D FETs have demonstrated strong potential for drug screening. Kinked nanowire FET probes, for instance, have been used to quantitatively characterize the effects of ion-channel blockers such as nifedipine and tetrodotoxin on intracellular APs. The field is progressing toward large-scale screening through the integration of vertical nanoelectrodes with CMOS technology. High-density CMOS NEAs now allow simultaneous recording from hundreds of cells, enabling evaluation of both network-level drug effects and the spatial heterogeneity of cellular responses.

Disease modeling

Combining patient-derived hiPSC-CMs with 3D nanodevices enables the in vitro reconstruction of disease-specific electrophysiological phenotypes, providing powerful models for investigating disease mechanisms and developing new therapies. Because alterations in AP morphology are directly associated with numerous CVDs, such platforms can precisely capture pathological electrical signals resulting from ion-channel dysfunction. Using nanopillar arrays, researchers have successfully modeled multiple genetic cardiac disorders in vitro. For example, recordings from hiPSC-CMs derived from a patient with HCM revealed hallmark AP abnormalities (including arrhythmia and delayed afterdepolarizations) that were absent in healthy controls (Fig. 7f)99. In addition to genetic conditions, integrating nanoelectronic devices into heart-on-a-chip systems allows dynamic pathological processes to be studied in real time30. For instance, by controlling oxygen concentration in a microfluidic channel to mimic acute hypoxia, integrated nanopillar arrays have been used to monitor the electrophysiological responses of cardiomyocytes in a previous study, and multiplexed synchronous recordings captured key changes (such as APD shortening under hypoxic conditions) and highlighted the spatial heterogeneity of cellular responses (Fig. 7g)100. The versatility of these platforms also extends to modeling pharmacologically induced arrhythmias, such as those triggered by norepinephrine, and channelopathies arising from abnormal ionic environments, including hyperkalemia and hyponatremia. They have also been applied to genetic channelopathies such as long QT syndrome, wherein they accurately reproduced the characteristic prolongation of APD. Advances in flexible bioelectronic platforms and early demonstrations of in vivo recording suggest promising opportunities for translating these technologies into more physiologically relevant contexts.

Conclusion and Outlook

Over the past two decades, bioelectronic devices based on low-dimensional materials, particularly 1D nanostructures, have advanced from initial proof-of-concept studies to pivotal technologies in intracellular electrophysiology. These innovations have begun to resolve the long-standing trade-offs among fidelity, throughput, and long-term stability that limit conventional methods. By forming intimate 3D interfaces with cell membranes, such platforms markedly improve electrode–cell coupling and enable the acquisition of high-fidelity AP waveforms. This review has systematically outlined progress in the field, spanning bottom-up nanomaterial synthesis, top-down and hybrid fabrication strategies, multimodal device characterization, and methods for intracellular access. Comprehensive characterization not only confirms structural precision and electrochemical performance but also ensures reliable biocompatibility, establishing the foundation for downstream applications. Building on this technical basis, we then summarized the principles of cardiac electrophysiology and highlighted key applications in drug screening and disease modeling.

Despite significant progress, several critical challenges must be addressed before these devices transition from laboratory prototypes to widely adopted tools. A central challenge is achieving robust and reproducible performance, which must be addressed at both the manufacturing and experimental levels. At the manufacturing level, standardizing fabrication processes to ensure device-to-device consistency is a primary hurdle. For bottom-up methods, inherent variability in catalyst uniformity or growth conditions makes precise control over nanostructure dimensions and density difficult across large wafers. Conversely, top-down approaches, while more reproducible, are highly sensitive to minor process fluctuations in etching or deposition that can impact final device performance. At the experimental level, even for well-fabricated devices, ensuring long-term stability is critical for studying chronic disease progression. This requires further optimization of material biostability and antibiofouling surface chemistries to maintain a reliable interface over extended timescales. In parallel, although the high manufacturing cost of CMOS integration presents a significant obstacle, it is not universally essential for all experiments or applications. For many fundamental mechanistic studies, especially those involving the monitoring of a limited number of cells, low-density passive electrode arrays offer a cost-effective and highly valuable alternative. However, for applications that demand high parallelism and precise spatiotemporal resolution, such as large-scale drug screening and network-level analysis of arrhythmogenesis, CMOS integration becomes indispensable. These applications require the ability to capture the propagation of electrical signals across large syncytia and detect rare, stochastic events. Therefore, overcoming the challenges of efficient large-scale CMOS integration and effectively analyzing the resulting large datasets remains a key priority for advancing the field.

The future of cellular analysis lies in achieving a more holistic understanding of cell function through multimodal platforms that integrate nanoelectrodes with optical, chemical, and mechanical sensors. Although the focus here is on cardiomyocytes, the underlying design principles and bioelectronic strategies are broadly applicable to other excitable cells, including neurons. Many of these low-dimensional platforms have also achieved parallel advances in neuroscience, as illustrated in Fig. 7b. A major long-term objective is to interface these advanced arrays with physiologically relevant models, such as self-organizing cardiac organoids, thereby bridging the gap between 2D cell cultures and in vivo physiology. Ultimately, the transition from the culture dish to living organisms will require the development of flexible, biocompatible, and chronically implantable nanoprobe arrays capable of high-resolution intracellular monitoring in living tissue. In conclusion, intracellular electrophysiological recording technologies based on low-dimensional materials continue to advance our ability to probe cellular function at unprecedented resolution. As challenges related to stability, scalability, and integration are progressively addressed, these platforms are poised to play a decisive role in elucidating CVD mechanisms and accelerating the development of next-generation therapies.

References

Fuster, V. Top 10 cardiovascular therapies and interventions for the next decade. Nat Rev Cardiol 11, 671–683 (2014).

Zhao, D., Liu, J., Wang, M., Zhang, X. & Zhou, M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat Rev Cardiol 16, 203–212 (2019).

WHO. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (2025).

Pineiro, D. J., Codato, E., Mwangi, J., Eisele, J. L. & Narula, J. Accelerated reduction in global cardiovascular disease is essential to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Rev Cardiol 20, 577–578 (2023).

Ezzati, M. et al. Contributions of risk factors and medical care to cardiovascular mortality trends. Nat Rev Cardiol 12, 508–530 (2015).

Al-Kindi, S. G., Brook, R. D., Biswal, S. & Rajagopalan, S. Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution. Nat Rev Cardiol 17, 656–672 (2020).

Nishiga, M., Wang, D. W., Han, Y., Lewis, D. B. & Wu, J. C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol 17, 543–558 (2020).

Janssen, H., Koekkoek, L. L. & Swirski, F. K. Effects of lifestyle factors on leukocytes in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 21, 157–169 (2024).

Vaccarino, V. & Bremner, J. D. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. Nat Rev Cardiol 21, 603–616 (2024).

Gintant, G., Sager, P. T. & Stockbridge, N. Evolution of strategies to improve preclinical cardiac safety testing. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 457–471 (2016).

Fabiani, I., Chianca, M., Cipolla, C. M. & Cardinale, D. M. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: risk prediction, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Cardiol 22, 551–563 (2025).

Garg, P. et al. Human induced Pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as models for cardiac channelopathies: a primer for non-electrophysiologists. Circ Res 123, 224–243 (2018).

Nerbonne, J. M. Controlling the traffic to keep the beat: targeting of myocardial sodium channels. Circ Res 129, 366–368 (2021).

Seibertz, F. et al. A modern automated patch-clamp approach for high throughput electrophysiology recordings in native cardiomyocytes. Commun Biol 5, 969 (2022).

Xue, J., Shao, M., Gao, Z. & Hu, N. Advances in micro-nano biosensing platforms for intracellular electrophysiology. J Zhejiang Univ Sci A 24, 1017–1026 (2023).

Cull-Candy, S. G., Miledi, R. & Parker, I. Single glutamate-activated channels recorded from locust muscle fibres with perfused patch-clamp electrodes. J Physiol 321, 195–210 (1981).

Sakmann, B. & Neher, E. Patch clamp techniques for studying ionic channels in excitable membranes. Annu Rev Physiol 46, 455–472 (1984).

Fertig, N., Blick, R. H. & Behrends, J. C. Whole cell patch clamp recording performed on a planar glass chip. Biophys J 82, 3056–3062 (2002).

Pantoja, R. et al. Silicon chip-based patch-clamp electrodes integrated with PDMS microfluidics. Biosens Bioelectron 20, 509–517 (2004).

Milligan, C. J. et al. Robotic multiwell planar patch-clamp for native and primary mammalian cells. Nat Protoc 4, 244–255 (2009).

Zhao, Y. et al. Patch clamp technique: Review of the current state of the art and potential contributions from nanoengineering. Proc Inst Mech Eng N: J Nanoeng Nanosyst 222, 1–11 (2009).

Siegel, M. S. & Isacoff, E. Y. A genetically encoded optical probe of membrane voltage. Neuron 19, 735–741 (1997).

Matiukas, A. et al. New near-infrared optical probes of cardiac electrical activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290, H2633–H2643 (2006).

Herron, T. J., Lee, P. & Jalife, J. Optical imaging of voltage and calcium in cardiac cells & tissues. Circ Res 110, 609–623 (2012).

Klimas, A. et al. OptoDyCE as an automated system for high-throughput all-optical dynamic cardiac electrophysiology. Nat Commun 7, 11542 (2016).

Scanziani, M. & Hausser, M. Electrophysiology in the age of light. Nature 461, 930–939 (2009).

Stett, A. et al. Biological application of microelectrode arrays in drug discovery and basic research. Anal Bioanal Chem 377, 486–495 (2003).

Reppel, M. et al. Microelectrode arrays: a new tool to measure embryonic heart activity. J Electrocardiol 37, 104–109 (2004).

Chang, J. C., Brewer, G. J. & Wheeler, B. C. Microelectrode Array Recordings of Patterned Hippocampal Neurons for Four Weeks. Biomed Microdevices 2, 245–253 (2000).

Han, J. et al. Mechanically Matched Heart-on-a-Chip Platform Mediated Maturation of Excitation-Contraction Coupling. ACS Nano 19, 24052–24066 (2025).

Spira, M. E. & Hai, A. Multi-electrode array technologies for neuroscience and cardiology. Nat Nanotechnol 8, 83–94 (2013).

Zhang, A. & Lieber, C. M. Nano-bioelectronics. Chem Rev 116, 215–257 (2016).

Abbott, J., Ye, T., Ham, D. & Park, H. Optimizing nanoelectrode arrays for scalable intracellular electrophysiology. Acc Chem Res 51, 600–608 (2018).

Hu, J., Odom, T. W. & Lieber, C. M. Chemistry and physics in one dimension: synthesis and properties of nanowires and nanotubes. Acc Chem Res 32, 435–445 (1999).

Juhasz, R., Elfstrom, N. & Linnros, J. Controlled fabrication of silicon nanowires by electron beam lithography and electrochemical size reduction. Nano Lett 5, 275–280 (2005).

Shalek, A. K. et al. Vertical silicon nanowires as a universal platform for delivering biomolecules into living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 1870–1875 (2010).

Joyce, H. J. et al. III–V semiconductor nanowires for optoelectronic device applications. Prog Quantum Electron 35, 23–75 (2011).

Ren, J. et al. Superaligned carbon nanotubes guide oriented cell growth and promote electrophysiological homogeneity for synthetic cardiac tissues. Adv. Mater. 29 (2017).

Hanson, L. et al. Vertical nanopillars for in situ probing of nuclear mechanics in adherent cells. Nat Nanotechnol 10, 554–562 (2015).

Higgins, S. G. et al. High-aspect-ratio nanostructured surfaces as biological metamaterials. Adv Mater 32, e1903862 (2020).

Lee, J. et al. Repeated and on-demand intracellular recordings of cardiomyocytes derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cells. ACS Sens 7, 3181–3191 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Scalable ultrasmall three-dimensional nanowire transistor probes for intracellular recording. Nat Nanotechnol 14, 783–790 (2019).

Jahed, Z. et al. Nanocrown electrodes for parallel and robust intracellular recording of cardiomyocytes. Nat Commun 13, 2253 (2022).

Fan, H. J., Werner, P. & Zacharias, M. Semiconductor nanowires: from self-organization to patterned growth. Small 2, 700–717 (2006).

Wagner, R. S. & Ellis, W. C. Vapor-liquid-solid mechanism of single crystal growth. Appl Phys Lett 4, 89–90 (1964).

Li, W. Z. et al. Large-scale synthesis of aligned carbon nanotubes. Science 274, 1701–1703 (1996).

Cao, L. et al. Instability and transport of metal catalyst in the growth of tapered silicon nanowires. Nano Lett 6, 1852–1857 (2006).

Tsivion, D., Schvartzman, M., Popovitz-Biro, R., von Huth, P. & Joselevich, E. Guided growth of millimeter-long horizontal nanowires with controlled orientations. Science 333, 1003–1007 (2011).

Wang, H. et al. Oxide shell assisted vapor− liquid− solid growth of periodic composite nanowires: a case of Si/Sn. Chem Mater 19, 5598–5601 (2007).

Wang, H. et al. Bulk preparation of Si-SiOx hierarchical structures: high-density radially oriented amorphous silica nanowires on a single-crystal silicon nanocore. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 44, 6934–6937 (2005).

Dasgupta, N. P. et al. 25th anniversary article: semiconductor nanowires-synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv Mater 26, 2137–2184 (2014).

Lieber, C. M. Nanoscale science and technology: Building a big future from small things. MRS Bull 28, 486–491 (2003).

Gupta, A. K. & Gupta, M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 26, 3995–4021 (2005).

Zhou, X., Boey, F. & Zhang, H. Controlled growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on patterned substrates. Chem Soc Rev 40, 5221–5231 (2011).

Gao, Q. et al. Simultaneous selective-area and vapor-liquid-solid growth of InP nanowire arrays. Nano Lett 16, 4361–4367 (2016).

Westwater, J., Gosain, D. P., Tomiya, S., Usui, S. & Ruda, H. Growth of silicon nanowires via gold/silane vapor–liquid–solid reaction. J Vac Sci Technol B: Microelectron Nanometer Struct Process, Meas, Phenom 15, 554–557 (1997).

Gudiksen, M. S., Wang, J. & Lieber, C. M. Synthetic control of the diameter and length of single crystal semiconductor nanowires. J Phys Chem B 105, 4062–4064 (2001).

Tian, B. et al. Three-dimensional, flexible nanoscale field-effect transistors as localized bioprobes. Science 329, 830–834 (2010).

Cools, J. et al. 3D microstructured carbon nanotube electrodes for trapping and recording electrogenic cells. Adv Funct Mater 27, 1701083 (2017).

Gordon, R. G., Hausmann, D., Kim, E. & Shepard, J. A kinetic model for step coverage by atomic layer deposition in narrow holes or trenches. Chem Vap Depos 9, 73–78 (2003).

George, S. M. Atomic layer deposition: an overview. Chem Rev 110, 111–131 (2010).

Wang, H., Sun, M., Ding, K., Hill, M. T. & Ning, C. Z. A top-down approach to fabrication of high quality vertical heterostructure nanowire arrays. Nano Lett 11, 1646–1650 (2011).

Liu, R. et al. Ultra-sharp nanowire arrays natively permeate, record, and stimulate intracellular activity in neuronal and cardiac networks. Adv Funct Mater 32, 2108378 (2022).

Liu, R. et al. High density individually addressable nanowire arrays record intracellular activity from primary rodent and human stem cell derived neurons. Nano Lett 17, 2757–2764 (2017).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Vertical nanowire electrode arrays as a scalable platform for intracellular interfacing to neuronal circuits. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 180–184 (2012).

Desbiolles, B. X. E., de Coulon, E., Bertsch, A., Rohr, S. & Renaud, P. Intracellular recording of cardiomyocyte action potentials with nanopatterned volcano-shaped microelectrode arrays. Nano Lett 19, 6173–6181 (2019).

Desbiolles, B. X. E. et al. Nanovolcano microelectrode arrays: toward long-term on-demand registration of transmembrane action potentials by controlled electroporation. Microsyst Nanoeng 6, 67 (2020).

Desbiolles, B. X. E. et al. Volcano-shaped scanning probe microscopy probe for combined force-electrogram recordings from excitable cells. Nano Lett 20, 4520–4529 (2020).

Shukla, S. et al. Supra- and sub-threshold intracellular-like recording of 2D and 3D neuronal networks using nanopillar electrode arrays. Microsyst Nanoeng 10, 184 (2024).

Gu, Y. et al. Three-dimensional transistor arrays for intra- and inter-cellular recording. Nat Nanotechnol 17, 292–300 (2022).

Duan, X. et al. Intracellular recordings of action potentials by an extracellular nanoscale field-effect transistor. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 174–179 (2011).

Hai, A., Shappir, J. & Spira, M. E. In-cell recordings by extracellular microelectrodes. Nat Methods 7, 200–202 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. Sensitive and prolonged intracellular electrophysiological recording by three-dimensional nanodensity regulation. View 4, 20230031 (2023).

Qing, Q. et al. Free-standing kinked nanowire transistor probes for targeted intracellular recording in three dimensions. Nat Nanotechnol 9, 142–147 (2014).

Lin, Z. C., Xie, C., Osakada, Y., Cui, Y. & Cui, B. Iridium oxide nanotube electrodes for sensitive and prolonged intracellular measurement of action potentials. Nat Commun 5, 3206 (2014).

Xu, D. et al. Porous polyethylene terephthalate nanotemplate electrodes for sensitive intracellular recording of action potentials. Nano Lett 22, 2479–2489 (2022).

Hu, N. et al. Intracellular recording of cardiomyocyte action potentials by nanobranched microelectrode array. Biosens Bioelectron 169, 112588 (2020).

Xu, D. et al. Synchronized intracellular and extracellular recording of action potentials by three-dimensional nanoroded electroporation. Biosens Bioelectron 192, 113501 (2021).

Dou, W. et al. A Carbon-based biosensing platform for simultaneously measuring the contraction and electrophysiology of iPSC-Cardiomyocyte monolayers. ACS Nano 16, 11278–11290 (2022).

Xie, C., Lin, Z., Hanson, L., Cui, Y. & Cui, B. Intracellular recording of action potentials by nanopillar electroporation. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 185–190 (2012).

Dipalo, M. et al. Intracellular and extracellular recording of spontaneous action potentials in mammalian neurons and cardiac cells with 3D plasmonic nanoelectrodes. Nano Lett 17, 3932–3939 (2017).

Dipalo, M. et al. Plasmonic meta-electrodes allow intracellular recordings at network level on high-density CMOS-multi-electrode arrays. Nat Nanotechnol 13, 965–971 (2018).

Kotnik, T. et al. Electroporation-based applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol 33, 480–488 (2015).

Kotnik, T., Rems, L., Tarek, M. & Miklavcic, D. Membrane electroporation and electropermeabilization: mechanisms and models. Annu Rev Biophys 48, 63–91 (2019).

Fang, J. et al. Accurate and efficient intracellular delivery biosensing system by nanostrawed electroporation array. Biosens Bioelectron 194, 113583 (2021).

Fang, J. et al. Integrated cardiomyocyte-based biosensing platform for electroporation-triggered intracellular recording in parallel with delivery efficiency evaluation. Nano Lett 23, 4049–4057 (2023).

Xu, D. et al. Scalable nanotrap matrix enhanced electroporation for intracellular recording of action potential. Nano Lett 22, 7467–7476 (2022).

Xu, D. et al. A universal, multimodal cell-based biosensing platform for optimal intracellular action potential recording. Biosens Bioelectron 206, 114122 (2022).

Fang, J. et al. Scalable and robust hollow nanopillar electrode for enhanced intracellular action potential recording. Nano Lett 23, 243–251 (2023).

Han, H. et al. Elevating intracellular action potential recording in cardiomyocytes: A precision-enhanced and biosafe single-pulse electroporation system. Biosens Bioelectron 246, 115860 (2024).

Dipalo, M. et al. Intracellular action potential recordings from cardiomyocytes by ultrafast pulsed laser irradiation of fuzzy graphene microelectrodes. Sci Adv 7, eabd5175 (2021).

Melikov, R. et al. Longitudinal and noninvasive intracellular recordings of spontaneous electrophysiological activity in rat primary neurons on planar MEA Electrodes. Adv Mater 37, e2412697 (2025).

Dipalo, M. et al. Membrane poration mechanisms at the cell-nanostructure interface. Adv Biosyst 3, e1900148 (2019).

Marban, E. Cardiac channelopathies. Nature 415, 213–218 (2002).

Giudicessi, J. R. & Ackerman, M. J. Potassium-channel mutations and cardiac arrhythmias-diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 9, 319–332 (2012).

Hille, B. & Catterall, W. A.(s). Electrical Excitability and Ion Channels in Electrical Excitability and Ion Channels of book (eds. Scott T. Brady, George J. Siegel, R. Wayne Albers, & Donald L. Price(s)) (Academic Press, 2012).

Ikonnikov, G., Yelle, D., Wong, E. & Chaudhry, S. Physiology of cardiac conduction and contractility. McMaster Pathophysiol Rev (2013).

Abbott, J. et al. A nanoelectrode array for obtaining intracellular recordings from thousands of connected neurons. Nat Biomed Eng 4, 232–241 (2020).

Lin, Z. C. et al. Accurate nanoelectrode recording of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes for assaying drugs and modeling disease. Microsyst Nanoeng 3, 16080 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Heart-on-a-chip model with integrated extra- and intracellular bioelectronics for monitoring cardiac electrophysiology under acute hypoxia. Nano Lett 20, 2585–2593 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Cardiotoxicity drug screening based on whole-panel intracellular recording. Biosens Bioelectron 216, 114617 (2022).

Abbott, J. et al. CMOS nanoelectrode array for all-electrical intracellular electrophysiological imaging. Nat Nanotechnol 12, 460–466 (2017).

Yang, F. et al. Chirality-specific growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on solid alloy catalysts. Nature 510, 522–524 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Electrochemical deposition as a universal route for fabricating single-atom catalysts. Nat Commun 11, 1215 (2020).

Parsons, G. N., George, S. M. & Knez, M. Progress and future directions for atomic layer deposition and ALD-based chemistry. Mrs Bull 36, 865–871 (2011).

Ejsmont, A. & Goscianska, J. Hydrothermal Synthesis of ZnO superstructures with controlled morphology via temperature and pH optimization. Materials 16, 1641 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, A., Liang, T., Niu, L. et al. Low-dimensional materials for intracellular electrophysiology: advances from synthesis to applications. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 51 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01148-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01148-2