Abstract

Lipid metabolism is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, and its dysregulation is linked to various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Immune cells, such as macrophages, T cells, B cells, and neutrophils, rely on lipid metabolism for their function, which impacts both innate and adaptive immune responses. Understanding how lipid metabolism influences immune cells is crucial, as it can reveal new therapeutic opportunities for immune-mediated diseases. In this review, we provide a retrospective summary of the research history and milestone events in lipid metabolism research and highlight the importance of lipid metabolism in immune cells. In addition to discussing the various lipid functions, transport, and signaling pathways involved in lipid metabolism, we mainly explore the regulation of immune cell behavior by lipid metabolism, focusing on the roles of lipid metabolites in immune cell proliferation, differentiation, and activation. We further highlight multilevel regulatory mechanisms, including genetic, epigenetic, posttranscriptional, and posttranslational regulation, and their impact on immune cell function. Additionally, we discuss the role of lipid metabolism in diseases such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, aging, and metabolic disorders. Finally, we summarize therapeutic strategies targeting lipid metabolism, the progress of global clinical trials, and future research directions, including lipid-derived biomarkers and innovative therapeutic approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipids, including fatty acids (FAs), cholesterol, phospholipids, and triglycerides, are essential for maintaining physiological functions, such as energy storage, membrane structure, and cell signaling. Lipid metabolism, which involves the synthesis and degradation of lipids, plays a vital role in cellular homeostasis, and disruptions in lipid metabolism are associated with various pathological conditions.1 Recent research has highlighted lipids as key regulators of cellular function, particularly in immune cells, where lipid metabolism affects immune responses, cell phenotypes, metabolic pathways, and cytokine levels.2,3,4,5,6 This influence can profoundly affect their functions under both healthy and disease conditions (Fig. 1).

Etiological triggers of disease onset. Various factors, such as a high-fat diet, smoking, viral and bacterial infections, and genetic defects, can disrupt immune cell function and disturb immune homeostasis, resulting in various diseases, including cancer, aging, autoimmune diseases, NDDs, CVDs, etc. Lipid metabolism (e.g., FAs cholesterol, BAs phospholipids, glycolipids, and triglycerides) affects immune cell proliferation, differentiation, and the release of inflammatory mediators. Modulation of lipid metabolism may effectively mitigate the progression of these diseases. Created in BioRender

Historically, studies of lipid metabolism have evolved significantly over the years (Fig. 2). In the 19th century, important lipids such as bile acids (BAs), phospholipids, and sphingolipids were discovered,7,8,9,10 paving the way for further exploration of their biological roles. In the mid-20th century, advancements were made in studies of the role of cholesterol in metabolic diseases,11 fatty acid oxidation (FAO) pathways, and the “phospholipid effect”.12 The introduction of statins in 1979 revolutionized cardiovascular treatment,13 whereas breakthroughs in the 1990s elucidated the roles of sphingolipids in immunity and polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) in immune cell regulation.14,15,16 Advances in lipidomics, especially in mass spectrometry, have furthered the analysis of lipid structure and function, shedding light on the roles of lipids in inflammation and metabolism.17,18,19,20

Timeline of lipid metabolism. The history of BAs is highlighted in pink boxes. New discoveries regarding phospholipids are shown in yellow boxes. The green boxes represent milestone events in the history of FAs. Key findings on lipid rafts are marked in blue boxes, whereas sphingolipid milestones are shown in white boxes. The gray boxes indicate historical developments in lipidomics. Over time, lipid metabolism has become a significant focus of research and interest. Created in BioRender

Interestingly, lipid metabolism in immune cells is particularly dynamic, as it changes significantly during immune activation or inflammation. Unlike nonimmune cells, immune cells critically rely on lipid metabolism to support immune responses.4,21,22,23 For example, T cells and macrophages use FAO and oxidative phosphorylation in their resting state to maintain homeostasis, but during immune activation, they increase glucose metabolism and FAO to meet increased energy demands.24,25,26,27 In contrast, nonimmune cells, such as muscle cells, endothelial cells, and adipocytes, primarily utilize lipid metabolism for energy storage and basic functions, with less involvement in immune regulation.28,29

Clinically, targeting lipid metabolism in immune cells has shown therapeutic potential, particularly in inflammatory diseases, immune deficiencies, and cancer. For example, modulating FA metabolism in T cells can prevent exhaustion and increase the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors.30,31 Moreover, lipid metabolism in immune cells is closely linked to immune regulation in metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA).32,33,34 Targeting lipid metabolism in immune cells may help alleviate chronic low-grade inflammation, improve metabolic states, and enhance immune responses.32,33,34

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of how lipid metabolism influences immune cell behavior, particularly in macrophages, T cells, B cells, and neutrophils, under different physiological and pathological conditions. In this review, we first explore the roles of circulating lipids in regulating immune cell activity across various immunological contexts and disease environments. We then delineate the roles of membrane lipids in intracellular signaling and in shaping immune cell function. Additionally, we highlight the intricate interactions between intracellular signaling pathways and lipid metabolism under different conditions, as well as the underlying regulatory mechanisms involved. Finally, we present a thorough assessment of how lipid metabolism impacts various diseases, consolidating both preclinical and clinical evidence and emphasizing potential strategies targeting lipid pathways to modulate immune cell activity in disease management.

Circulating lipids regulate immune cell responses

Circulating lipids, mainly FAs, cholesterol and cholesterol-derived metabolites, and BAs, are increasingly recognized as crucial sources of nutrients for cellular energy production and biomass generation.35 These lipids serve as essential reservoirs for energy and building blocks. Moreover, they function as signaling molecules crucial for both innate and adaptive immune responses. We summarized the roles of circulating lipids in regulating immune cell responses, especially in the response mediated by macrophages, T cells, B cells, neutrophils, and others (Table 1).

Fatty acids

FAs are categorized according to their length into short-chain (SCFAs), medium-chain, long-chain (LCFAs), and very-long-chain FAs. They play integral roles in regulating immune cell function, inflammation, and overall immune system health.

SCFAs

SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are produced primarily by the gut microbiota through fermentation of dietary fiber (Fig. 3a).36,37 Dietary fiber provides an appropriate substrate for bacteria to produce SCFAs, which are directly associated with increased levels of SCFAs in the gut.38 In addition to promoting microbial diversity and SCFA production, a high-fiber diet can also decrease the levels of inflammatory markers, such as Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, in immune cells.39 In contrast, a low-fiber diet leads to decreased SCFA levels, impaired colonic mucus barrier function, and increased susceptibility of mice to pathogenic bacteria, such as Citrobacter rodentium.40 Therefore, Western diets are associated with lower fecal and serum SCFA levels and reduced microbial fermentation.41 Moreover, SCFAs have been shown to signal through surface-expressed free FA receptors or via G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs), such as GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109A, which are expressed on epithelial cells, adipose tissue, and immune cells.42 Both GPR41 and GPR43 bind acetate, propionate, and butyrate, whereas GPR109A is primarily activated by butyrate. The activation of GPR43 by SCFAs can have various effects depending on the cell type,42 which we will mention further below.

Regulation of immune cell functions by FAs, cholesterol, cholesterol derivatives, and BAs. a SCFAs originate from dietary fiber, whereas LCFAs are obtained primarily from the diet. SCFAs and LCFAs bind to the receptors GPR41, GPR43, GPR109A, and CD36, respectively, and enter the TCA cycle to regulate immune cell functions. b Cholesterol is predominantly synthesized in hepatocytes and released into the bloodstream, where it is absorbed by immune cells to elicit immune responses. c BAs, which originate from the liver, undergo metabolism by the gut microbiota to produce secondary BAs (e.g., LCA, DCA, UDCA), along with their derivatives (e.g., 3-oxoLCA/DCA, isoalloLCA, isoLCA/DCA, 3-oxoalloLCA). These metabolites play significant roles in mediating immune cell functions. The notation (+) indicates upregulation, whereas (-) indicates downregulation. Created in BioRender

SCFAs can influence the recruitment of immune cells and affect the production of inflammatory mediators.42,43 For example, by inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity, SCFAs promote mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation as well as glycolysis, which are essential for robust plasma B cell generation.44 Moreover, SCFAs such as acetate enhance the function of IL-10-producing regulatory B (Breg) cells, contributing to immune regulation.45 The potential mechanism is that acetate induces Breg differentiation through its conversion into acetyl-CoA, which promotes the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and increases protein acetylation. This process undoubtedly promotes the production of IgG and IgA, thereby enhancing the humoral immune response. Moreover, SCFAs also increase the abundance of IgA-coated bacteria in the intestine, thereby regulating intestinal microorganisms, preventing dysbiosis, and maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis.44

The modulation of T cells by SCFAs is also crucial. For example, deregulation of T cell maturation is observed in preeclampsia, coincident with a reduction in maternal serum acetate levels. Similar phenomena have been noted in sterile mice, and such deficiencies can be rectified through supplementation with acetate,46 suggesting that SCFAs function in thymic T cell maturation, particularly regulatory T (Treg) cell maturation. Although there is ongoing debate regarding whether SCFAs can promote the differentiation of peripheral CD4+ T cells into forkhead box P3+ (Foxp3+) T cells, it is generally accepted that SCFAs can enhance the function of Treg cells either through GPR43 activation or by influencing histone acetylation levels.47,48 SCFAs are also recognized for their ability to increase the activities of T helper 1 (Th1) and Th17 cells, both of which contribute to preventing and combating infections, and for promoting immunity or immune tolerance according to the immunological context.49 Mechanistically, the effects of SCFAs on T cells do not rely on GPR41 or GPR43 but rather on the direct inhibitory activity of HDACs. The inhibition of HDACs by SCFAs in T cells increases the acetylation of p70 S6 kinase and the phosphorylation of rS6, thereby regulating the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway required for the generation of Th17 and Th1 cells.49

In macrophages, sodium butyrate significantly inhibits inflammation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated or other classically activated M1-polarized macrophages, inhibits M1 macrophage polarization and promotes oxidative phosphorylation to drive M2 macrophage polarization. This effect extends to regulating conditions such as muscle cell atrophy, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and macrophage-dependent intestinal immune homeostasis.50,51,52 Mechanistically, through HDAC inhibition, butyrate enhances the acetylation of the canonical nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) subunit p65 and its differential recruitment to pro-inflammatory gene promoters, independent of nuclear translocation, or through protein kinase B (Akt)/mTOR/forkhead box O3a (FoxO3a) and F-box protein 32/tripartite motif-containing protein 63 (FBOX32/TRIM63) pathways.50,51 Interestingly, while propionate and butyrate suppress M2 macrophage polarization and alleviate airway inflammation, acetate does not have the same effect and can instead abrogate M2 macrophage polarization in an asthma model and in human-derived macrophages.53 These findings suggest that SCFAs may exert a dual modulatory effect on macrophage activation. Moreover, exogenous acetate/propionate activates the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-type I interferon (IFN-I) axis through GPR43 signal transduction in macrophages. This activation protects against enteric virus infection in mice by increasing intracellular calcium (Ca2+) and mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein-dependent mitochondrial DNA release.54

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are mesh-like structures released by neutrophils under specific stimuli, such as inflammatory mediators, immune complexes, pathogenic microorganisms, and external environmental factors. NETs are composed primarily of DNA, histones, and various antimicrobial proteins, such as elastase and myeloperoxidase.55,56 The formation of NETs can be divided into two pathways: one is cell death-associated NET formation (also called NETosis), which involves cell membrane rupture and nuclear membrane disintegration and is usually accompanied by cell death; the other is the nonclassical pathway of NETosis, which involves chromatin extrusion and the release of granule proteins without cell death.56 NETs play a critical role in the initiation and perpetuation of systemic autoimmune diseases as well as in driving inflammatory responses that lead to organ damage.57,58 Studies have shown that SCFAs regulate the transepithelial migration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and the formation of NETs at different concentrations. Acetate promotes polymorphonuclear neutrophil migration at high concentrations, whereas propionate and butyrate significantly induce both polymorphonuclear neutrophil migration and NETosis at specific concentrations.59 These results suggest that SCFAs enhance neutrophil function by stimulating their migration to inflamed areas, thereby increasing the activity of platelet-activating factor and exerting anti-inflammatory effects.60,61

With respect to other immune cells, SCFAs regulate immune balance and antitumor effects through HDAC inhibition, thereby enhancing the antigen-presenting capacity of dendritic cells (DCs).62 Moreover, SCFAs such as butyrate and pentanoate inhibit mast cell activation and reduce IgE-mediated degranulation by suppressing HDAC activity.63,64

Overall, SCFAs maintain immune homeostasis primarily by regulating cell differentiation, polarization, migration, and the immune response in various immune cells. They enhance immune responses by regulating T cell differentiation and function, promoting M2 macrophage polarization while inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization to exert anti-inflammatory effects, enhancing B cell differentiation and humoral immune responses, supporting neutrophil migration and function, promoting DC antigen presentation, and inhibiting mast cell activation.

LCFAs

Most LCFAs are present in most fats in our diet, such as corn oil, olive oil, and chicken fat, while a small amount is synthesized de novo (Fig. 3a). Upon consumption, LCFAs integrate into the cell membrane, influencing membrane fluidity and the immune response.65 LCFAs are made up of three types of PUFAs: unsaturated FA-, monounsaturated FA (MUFA), and saturated FA (SFA), according to their chemical structure.

PUFAs can modulate pathways in T and B cells, as observed in preclinical models. For example, fish oils are rich in n-3 long-chain PUFAs, such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), both of which can influence T cell function by inhibiting signal transduction through the T cell receptor (TCR) and CD28, thus diminishing CD4+ T cell function.66 In addition, EPA, DHA, and arachidonic acid have been reported to directly become part of the cell membrane and decrease CD4+ T cell proliferation ex vivo and in vitro via the modulation of metabolism and inflammation.67,68,69 An in vitro study demonstrated that DHA can inhibit major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) expression, the expression of costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, and CD86), and the production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-12p70), thereby suppressing CD4+ T cell activation.70 Furthermore, DHA and EPA can alleviate cow milk and peanut allergies in mice by reducing IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a levels, promoting Treg generation, and suppressing Th2 and Th1 cell activation.71,72 Notably, a soy diet rich in n-6 PUFAs increases Th1-like responses but decreases Th2-like responses.73 However, increasing the intake of n-3 long-chain PUFAs can mitigate this effect, highlighting the necessity of the n-3:n-6 PUFA ratio in dietary immune modulation.71

Furthermore, studies have shown that the levels of PUFAs in young and middle-aged individuals are significantly correlated with neutrophil function.74 Among these, n-3 PUFAs increase both the number and percentage of neutrophils during the perinatal period, thereby enhancing their ability to combat pathogens.75

In DCs, PUFAs such as conjugated linoleic acid, n-3, and n-6 FAs inhibit their activation and function.76 Specifically, n-6 PUFAs promote immune suppression by shifting DC metabolism toward glycolysis, thereby reducing immune stimulation.77 Furthermore, n-3 PUFAs inhibit Fc ε receptor I (FcεRI)-mediated mast cell activation, thereby reducing histamine levels.78

Additionally, MUFAs such as oleic acid improve human Treg functions by boosting FA oxidation-driven oxidative phosphorylation metabolism. This process forms a positive feedback loop that enhances Foxp3 expression and STAT5 phosphorylation.79 In addition, dietary trans-oleic acid, rather than its cis isomer oleic acid, can enhance basal or IFN-γ-stimulated MHC-I expression by upregulating MHC-I through nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family caspase recruitment domain domain-containing 5 (NLRC5), promoting tumor antigen presentation and enhancing CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.80

Moreover, SFAs such as lauric acid expand Th1 and Th17 cell populations by activating the p38/MAPK pathway,81 and contribute to a more severe course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS).81,82 In the context of macrophages, several studies have extensively documented the proinflammatory effects of palmitic acid. One study revealed that palmitic acid serves as a toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist, stimulating macrophages to release TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 by enhancing TLR-induced signaling pathways.83,84,85,86,87

Overall, LCFAs expand Th1 and Th17 cell populations by activating the p38/MAPK pathway, thereby promoting immune responses. They stimulate macrophages through enhancing TLR-induced signaling pathways and enhance Treg cell function by promoting FAO metabolism to facilitate immune tolerance. Additionally, LCFAs improve neutrophil function and suppress the activation of DCs and mast cells, thus regulating immunity.

Cholesterol

The abundance of cholesterol and its biosynthetic intermediates in the body has a significant impact on immune cell function in various disease contexts.88,89 In the periphery, the primary site of de novo cholesterol synthesis is hepatocytes (Fig. 3b). Cholesterol synthesized in the liver is released into the bloodstream, where it is absorbed by target cells, thereby influencing immune responses within the target tissue.88 During injury or infection, cytokines released into the bloodstream stimulate cholesterol synthesis in the liver.90,91,92 The liver then releases cholesterol into the bloodstream, facilitating its transport to immune cells in the periphery.

Notably, immune cells, particularly macrophages, can accumulate cellular cholesterol by absorbing modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL), thereby enhancing TLR signaling.88 Increased TLR activity leads to increased levels of cytokines and chemokines, exacerbating inflammation and potentially triggering NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation.93,94,95 Cholesterol accumulation and exposure to exogenous cholesterol can enhance the activation of inflammasomes in macrophages. Treatment of cultured macrophages with cholesterol crystals leads to rapid phagocytosis of the crystals, which are then stored in lipid droplets (LDs). These cholesterol-rich LDs subsequently drive the dose-dependent secretion of IL-1β, a process that relies on caspase-1 and NLRP3 activation.96 Studies have shown that this process is dependent on intracellular complement component (C) 5aR1 signaling, where C5a binds to receptors on the mitochondria, triggering ROS production and providing one of the necessary activation signals for inflammasome assembly and IL-1β secretion, especially in response to sterile inflammation induced by cholesterol crystal exposure.97 Furthermore, the absorption of cholesterol by neighboring neurons and microglia in neuroimmune macrophages influences the production of amyloid and neuroinflammatory cytokines.98,99

In the tumor microenvironment, cholesterol can cause endoplasmic reticulum stress, which promotes CD8+ T cell exhaustion and ultimately leads to uncontrolled tumor growth. Elevated plasma cholesterol levels disrupt T cell homeostasis, contributing to inflammation in patients with hypercholesterolemia.100 The oxysterol 7α,25-dihydroxycholesterol, a cholesterol derivative, signals through Epstein–Barr virus-induced gene 2 (EBI2, also known as GPR183) to facilitate the migration of activated CD4+ T cells to the interface between the B cell follicles and T cell zones in the spleen. This process enhances the accumulation of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, thereby initiating humoral immunity.101

A high level of cholesterol can affect the normal function of neutrophils. Research has shown that a high-cholesterol diet induces neutrophil infiltration, which plays a key role in liver injury through myeloperoxidase activity,102 with 7-ketocholesterol being particularly important in this process. Similarly, cholesterol accumulation in bone marrow cells activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, enhancing neutrophil accumulation and the formation of NETs in atherosclerotic plaques.103 Promoting cholesterol efflux, such as through treatment with liver X receptor (LXR) agonists, can inhibit neutrophil recruitment in a sterile peritonitis mouse model.104 Interestingly, another cholesterol derivative, cholesterol sulfate, can directly act on inflammatory neutrophils, preventing excessive intestinal inflammation by inhibiting the Rac activator dedicator of cytokinesis 2 (DOCK2).105

For other immune cells, increased cholesterol levels inhibit DC migration to lymph nodes, while reducing cholesterol levels can partially reverse these migration defects.106 Studies have also shown that mice fed a high-cholesterol diet have a greater number of eosinophils in their bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, with elevated levels of IL-5, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), which enhances allergic inflammation in the lungs.107

Cholesterol promotes inflammation and IL-1β secretion in macrophages, triggers T cell exhaustion in CD8+ T cells, and enhances immune responses in B cells by facilitating T cell migration and humoral immunity. In addition, cholesterol affects the function of other immune cells through multiple pathways, including promoting immune cell infiltration, activating inflammatory pathways, and regulating cytokine secretion, which may exacerbate inflammatory responses. Overall, given their multiple functions in immune cells, sterols may become potential targets for the development of immunotherapy in the future.

Bile acids

BAs are cholesterol metabolites that are abundantly stored in the mammalian intestine and promote lipid absorption in the intestine. BAs produced by the liver undergo metabolic transformation by the intestinal microbiota to produce enteric BAs such as lithocholic acid (LCA) and deoxycholic acid (DCA) (Fig. 3c). These derivatives play pivotal roles in immune cell biology.

As secondary BAs, DCA and LCA can enhance hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. Treatment of bone marrow cells with DCA and LCA preferentially expands immune phenotypes and functional colony-forming units, such as granulocyte‒macrophage progenitor cells.108 Among them, DCA enhances macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype, partly via TLR2 transactivation by the M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, leading to increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.109 In line with these findings, supplementation with DCA significantly promotes the infiltration of inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates the progression of colitis.109,110 However, variants of LCA, 3-oxoLCA and isoLCA have been identified as TGR5 agonists that promote M2 polarization of macrophages and have a positive effect on alleviating inflammation.111

Notably, BAs not only influence macrophage polarization but also play an important role in T-cell expansion. Derivatives of LCA and DCA act as crucial signaling molecules that modulate Th17 and Treg expansion, thereby reshaping gut inflammation.112,113,114 The variants of LCA, including iso-, 3-oxo-, allo-, 3-oxoallo-, and isoalloLCA, are formed through the collaborative action of 5α/β-reductase and 3α/β-HSDH.115,116 Among these variants, 3-oxoLCA directly interacts with retinoic acid receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma t (RORγt), hindering Th17 cell differentiation. Conversely, isoalloLCA promotes the generation of Tregs by inducing mitochondrial ROS that increases Foxp3 expression.112 Unlike butyrate, which enhances Treg differentiation via the Foxp3 conserved noncoding sequence 1 (CNS1) enhancer, isoalloLCA-induced Treg differentiation is independent of the vitamin D receptor and farnesoid X receptor (FXR) CNS3.112,117 Another study revealed that isoalloLCA increases nuclear receptor 4 group A1 (NR4A1) binding at the Foxp3 locus, increasing Foxp3 transcription and promoting Treg differentiation.113 Therefore, an engineered consortium producing isoDCA that stimulates RORγt+ Tregs has been established in the gut via a CNS1-dependent mechanism.114 Another study indicated that disrupting the bile salt hydrolase of the Bacteroides genus can impair the intracellular dissociation of BAs, significantly reducing the induction of colonic RORγt+ Treg cells.118 Consistent with these findings, restoring the intestinal BA pool can increase the RORγt+ Treg population and improve the susceptibility of the host to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) through BA nuclear receptors.118 Additionally, isoDCA can increase Foxp3 transcription by suppressing the immunostimulatory characteristics of DCs and, in turn, promote the proliferation of peripheral Tregs in the colon.114 Depletion of FXR in DCs mimics the transcriptional profile induced by isoDCA and augments peripheral Treg expansion, suggesting that the crosstalk between FXR and isoDCA is fundamental for maintaining the anti-inflammatory DC phenotype.114

In H. pylori-positive patients, a significant negative correlation has been observed between BA concentrations and the histological score of monocyte/neutrophil infiltration.119 Chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) has been previously shown to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis and Ca2+ influx by competing with N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe for binding to formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1). Similarly, DCA has been shown to suppress neutrophil chemotaxis and Ca2+ mobilization, and it is also believed to inhibit FPR1 signaling.120

Hydrophilic and lipophilic BAs exert distinct effects on immune cells. In mast cells, lipophilic dihydroxy BAs (such as CDCA and DCA as well as their glycine and taurine conjugates) directly activate mast cells, leading to histamine release.121 In contrast, hydrophilic BAs (such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and ursocholic acid and their conjugates) suppress mast cell activation, thereby alleviating bile duct-related damage, fibrosis, and inflammation in cholestatic diseases.122,123 However, unlike mast cells, taurine-conjugated CDCA and taurine-conjugated UDCA can activate human eosinophils at specific concentrations.124

Overall, although BAs are involved in immune regulation in various immune cells, their mechanisms and effects differ significantly: in macrophages, BAs affect inflammation by modulating polarization states, whereas in T cells, BAs regulate immune tolerance and response by modulating cytokine production and differentiation. For other immune cells, hydrophilic BAs alleviate inflammation by inhibiting the activation of neutrophils, DCs, and mast cells, whereas lipophilic BAs modulate immune responses by activating mast cells.

Membrane lipids regulate immune cell responses

It is well known that phospholipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol, as well as the functional membrane microdomains enriched with specific lipids, such as lipid rafts, are primarily components of cell membranes. These membrane lipid structures, functions, and signaling pathways are intricately connected to the expansion and activation of immune cells.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids constitute a diverse group of lipids that regulate intracellular signaling (Fig. 4a). Upon activation, TCRs and B cell receptors (BCRs) initiate a signaling cascade that involves the activation of phospholipase C (PLC). This enzyme hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 then promotes sustained Ca2+ influx, leading to an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. This process facilitates the translocation of activated T cell nuclear factor (NFAT) into the nucleus, leading to NFAT-mediated gene transcription initiation.125 Notably, NFAT family members (including NFATc1, NFATc2, and NFATc4) regulate T cell proliferation and differentiation.126 NFAT1 promotes Th1 differentiation and IFN-γ secretion, influencing the Th1/Th2 balance.127,128 Mice lacking NFAT1 and NFAT4 exhibit increased Th2 cell differentiation and cytokine levels.126,129 Additionally, NFAT2 deficiency reduces IL-4 secretion and impairs Th2 cell differentiation.130,131 These studies highlight the crucial role of NFAT in T cell differentiation.

Phospholipids mediate signaling in immune cells. a Antigens, costimulatory signals, cytokines, and other factors activate PI3K, which phosphorylates the metabolite PIP2 to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). Conversely, PTEN acts in the opposite direction, terminating the PI3K signaling pathway. PIP3 recruits phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1), activating AKT via phosphorylation at Thr308. In addition, mTORC2 phosphorylates AKT at Ser473. Activated AKT dissociates from the cell membrane to phosphorylate target proteins, such as BAD, FOXO, ACLY, MDM2, and IKK, influencing lipid metabolism, survival, apoptosis, differentiation, and other cellular responses in immune cells. PIP2 activates PLC, producing DAG and IP3. IP3 releases Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmic reticulum, leading to the progressive activation of CaM and CaN. CaN hydrolyzes and dephosphorylates NFAT, ultimately promoting its entry into the nucleus to mediate immune cell proliferation and differentiation. DGK converts DAG to PA and, together with PKC, initiates downstream signaling cascades that promote NF-κB entry into the nucleus, modulating the immune response. b Externally transported S1P binds to S1PRs via autocrine or paracrine signaling, regulating pathways such as the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Created in BioRender

NFAT signaling plays crucial roles in the activation, function, and migration of neutrophils. It is activated in neutrophils by various stimuli, including the binding of dectin-1 with fungal ligands such as yeast glucan. This activation triggers the expression of inflammatory genes, including Il10 and Cyclooxygenase 2 (Cox2), enhancing neutrophil responses.132 Inhibition of calcineurin (CaN)-NFAT signaling via drugs such as Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent phosphatase inhibitors has been shown to impair neutrophil function, thereby increasing susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections. These effects are attributed to the disruption of NFAT signaling in myeloid cells (including neutrophils), which in turn impairs pathogen clearance and immune responses.132,133

The diacylglycerol kinase (DGK)-mediated conversion of DAG to phosphatidic acid (PA) activates NF-κB, which is crucial for T cell function. DGK overexpression leads to defects in TCR signaling, while its deficiency promotes T cell expansion and IL-2 secretion.134 Furthermore, DGK defects promote CD8+ T cell activation and cytokine production during viral clearance but inhibit memory CD8+ T cell proliferation upon reinfection.135 These findings illustrate the duality of DGK in effector and memory CD8+ T cells.

Phosphoinositides are glycerophospholipids, with phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) serving as a crucial lipid kinase. By facilitating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, these lipids selectively recruit signaling proteins to the cell membrane to modulate the development and function of T and B cells.136,137 In B cells, once phosphorylated, AKT regulates protein expression, including B cell lymphoma 2-associated agonist of cell death (BAD), FOXO, mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2), IκB kinase (IKK), and ATP citrate lyase (ACLY), which control cell cycle progression, survival, metabolism, differentiation, lipid synthesis, and other functions.137,138 Notably, as a transcription factor crucial in various physiological and pathological processes, the transcriptional activity of FOXO can be inhibited when it is phosphorylated by AKT,139 eventually promoting B-cell proliferation and survival.140,141 In line with these results, FOXO deletion affects key B-cell genes, including early B-cell factor (EBF1), the IL-7 receptor, recombination-activating genes (RAG1 and 2), activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), L-selectin, and B-cell linker protein (BLNK), leading to B cell development.142 By deleting AKT1/2 or PI3KR1, FOXO expression can be disrupted, resulting in the development and maturation of B cells, particularly marginal zone B cells.143,144,145 For other immune cells, mice lacking FOXO 3a produce increased Th1- and Th2-secreted cytokines.146 Moreover, the inhibition of PI3K-AKT phosphorylation, which enhances FOXO1 expression, can suppress DC maturation.147

PI3K/AKT also has crucial functions in other immune cells. The inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, affecting the expression of lactate dehydrogenase A, thereby inhibiting glycolysis in neutrophils, reducing their chemotaxis and phagocytic functions, and leading to immune suppression.148 Similarly, downregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway inhibits the proliferation, migration, and degranulation of eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells in mice.48,149,150,151 These findings underscore the value of PI3K/AKT pathway signaling proteins as targets for the treatment of immune cell-mediated autoimmunity and malignancy.

In T cells, phospholipids activate signaling and gene transcription to regulate immune responses following TCR activation, particularly through the activation of the IP3 and NFAT transcription factors, which control T cell proliferation and differentiation. In B cells, phospholipids regulate immune tolerance by modulating cell survival, metabolism, and differentiation through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and the FOXO transcription factor, which governs metabolic and cell growth signals. In neutrophils, phospholipids regulate immune responses by activating the NFAT and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, which control glycolysis and cell migration. Additionally, this pathway plays an important role in the maturation and activation of DCs and regulates the proliferation, migration, and degranulation of eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells.

Sphingolipids

Sphingolipids, although constituting a relatively minor portion (approximately 5%) of membrane lipids, play indispensable roles. As a sphingolipid metabolite, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) can activate a series of downstream signaling molecules and is a bioactive substance that regulates cell physiological function and the immune response (Fig. 4b).152 The biological effects of S1P are mediated primarily through interactions with members of the GPR family, namely, S1P receptors (S1PRs) 1–5, to regulate the differentiation of immune cells and the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids.153,154 The S1P-S1PR pathway governs the movement and homing of various immune cells through signaling mechanisms such as the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathways.155,156

Previous studies have shown that S1PR1 and S1PR2 are expressed in different populations of macrophages and monocytes.157 In peritoneal macrophages from LDL receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice, the activation of S1PRs significantly reduces the levels of inflammatory TNF-α, TNF-R, and IL-6 upon LPS stimulation.158 In addition, S1PR activation can change the activation state and function of macrophages, changing them from the M1 type to the M2 type, controlling inflammation and thus alleviating atherosclerotic lesions.158 Similarly, a specific agonist of S1P or S1PR1, SEW2871, significantly inhibits markers of LPS-induced M1-type responses, such as TNF, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), and IL-12, further demonstrating the beneficial effects of S1PR activation on the body.157,159

Interestingly, another receptor, S1PR2, which is found in peritoneal macrophages in mice, is more effective at inhibiting the LPS-induced inflammatory response. Compared with macrophages from wild-type mice, S1PR2-deficient mice eliminate the effects of S1P and SEW2871 on macrophages,157,159 indicating that S1PR2 contributes to the functions of S1P and SEW2871. On the other hand, acting as a survival messenger, S1P is secreted by sphingosine kinase 1 (Sphk1) upon stimulation by apoptotic cells and confers a protective effect on macrophages, thereby preventing their early apoptosis.160

S1P also significantly impacts the immune responses mediated by T and B cells. The S1P-S1PR1 pathway promotes CD4+ T cell differentiation into Th1/Th17 cells but has a negligible effect on the cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity of allogeneic CD8+ T cells.161 Th17 cells are excreted from the intestine in an S1PR1-dependent manner and subsequently migrate to the kidney via the CCL20/C-C motif chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) axis, thereby causing nephritis.162 Furthermore, S1PR inhibits extrathymic and innate Treg cell production while driving Th1 development in a reciprocal manner, which is reciprocally regulated by S1P1-mTOR and the opposing TGF-β-Smad3 signaling.163 Targeted S1P therapy helps maintain the survival of both T and B cells, inhibits homeostatic proliferation, and suppresses cytokine production induced by TCR activation in CD4+ T cells.164,165

According to previous reports, S1P strongly promotes the migration and cytoskeletal remodeling of neutrophils in the bone marrow via S1PR1 or S1PR2.166 Blocking S1PR2 significantly reduces neutrophil infiltration in liver injury induced by bile duct ligation in mice. Thus, the S1P/S1PR system plays a crucial role in neutrophil recruitment. Additionally, S1P stimulates NETosis through receptors on neutrophils, and inhibiting S1P signaling can effectively prevent NETosis.167

In allergic diseases, changes in S1P levels can influence the differentiation and reactivity of mast cells. Mast cell activation requires Sphk activation and the secretion of S1P.168 Studies have shown that Sphk2 knockout mice exhibit impaired mast cell degranulation,169 further highlighting the critical role of S1P in mast cell activation. Overall, S1P regulates polarization in macrophages, promotes immune responses in T cells, maintains immune homeostasis in B cells, and regulates migration and activation in neutrophils and mast cells.

Lipid rafts

Plasma membrane lipid rafts are microdomains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids, constituting crucial components of the cell membrane. These cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich regions form tightly packed, low-fluidity microdomains within the membrane, which participate in essential cellular processes, including regulating immune cell activation by reorganizing receptor localization and facilitating signal cascades.170

In B cells, under resting conditions, BCR and CD19 exhibit low affinity for lipid rafts and are therefore located primarily in nonraft domains of the plasma membrane.171 Upon antigen binding, mature B cells’ BCRs are more effectively recruited into lipid rafts, initiating the primary signaling events required for B cell activation (Fig. 5a).172 The Src family kinase Lyn subsequently acts downstream of the BCR to trigger a signaling cascade, leading to full B cell activation.173 Upon BCR activation, the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of Igα/Igβ undergo phosphorylation. This is followed by the phosphorylation of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) and BLNK, further propagating downstream signaling.174 Phosphorylated BLNK serves as a docking site for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and PLC-γ2, activating the NF-κB or PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, which promote B cell proliferation, differentiation, and antibody production.174,175 In immature B cells, even when antigens bind to the BCR, the complex fails to stably cluster within lipid rafts, resulting in inefficient signal initiation and often leading to failed activation or apoptosis.172 Additionally, studies have shown that Raftlin, a novel lipid raft linker protein, is critical for BCR-mediated signaling. The absence of Raftlin significantly reduces the levels of Lyn and ganglioside GM1 within lipid rafts, impairing tyrosine phosphorylation and Ca2+ signaling and thereby suppressing B cell activation.176

Activation of cell receptors and proximal signal transduction. a BCRs on the cell surface recognize and bind various forms of antigens, initiating an activation signal in B cells. This activation triggers a signaling cascade that results in complete B cell activation. CD19 serves as a critical coreceptor in this process, amplifying BCR signaling and enhancing downstream pathways such as the PI3K/AKT pathway, which promotes B cell proliferation and survival. b TCR activation relies on antigen-specific recognition and is further strengthened by auxiliary signals from CD3, coreceptors (such as CD4), and costimulatory signals from CD28, ultimately leading to T cell activation. Created in BioRender

In T cells, TCRs are weakly associated with lipid rafts under resting conditions, but this association is significantly enhanced upon antigen stimulation.177 During T cell activation, the TCR complex aggregates with signaling molecules in lipid rafts, such as the Src family lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck), thereby increasing signal transduction (Fig. 5b). Upon activation, Lck phosphorylates the ITAM regions on the CD3 and ζ chains of the TCR complex.178 Phosphorylated ITAMs provide binding sites for the downstream signaling protein ZAP-70, which subsequently phosphorylates linkers for the activation of T cells (LATs).179,180 Phosphorylated LAT recruits and activates multiple downstream proteins, including GRB2-related adapter protein downstream of Shc (Gads), SH2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa (SLP-76), and PLC-γ1, further propagating the signaling cascade. Gads bind to phosphorylated LAT and SLP-76, forming the LAT-Gads-SLP-76 complex.181 Through this interaction, Gads facilitates the recruitment of SLP-76 into the LAT complex, enabling PLC-γ1 to bind and be further activated by SLP-76.182 This process is essential for the generation of Ca2+ and protein kinase C (PKC) signals, which drive T cell activation and functional responses. Additionally, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) binds to the son of sevenless (Sos), localizing Sos near the membrane to activate the MAPK pathway.183 The integrity of lipid rafts is crucial for T cell activation. Reducing glycosphingolipid levels in CD4+ T cell lipid rafts impairs TCR signaling, thereby diminishing Th17 differentiation.184 Moreover, gangliosides, key components of lipid rafts, play distinct roles in the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.185 The loss of α2,6-sialylation disrupts TCR translocation to lipid rafts, suppressing CD4+ T cell activation and NF-κB expression, which leads to reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and alleviates ulcerative colitis progression.186 Interestingly, cholesterol-rich lipid rafts on activated T cells may enhance viral entry and syncytium formation.187

In conclusion, lipid rafts play crucial roles in regulating immune cell signaling, activation, differentiation, migration, and functional execution in immune cells. Their integrity and functional abnormalities are closely associated with various diseases. Targeting specific components of lipid rafts may provide new strategies for immune regulation and disease treatment. However, compared with other lipid mediators, there has been relatively limited research on the role of lipid rafts in immune cell-based disease therapies. Future research should focus more on the key functions of lipid rafts.

Intracellular reprogramming of lipid metabolism regulates immune cell responses

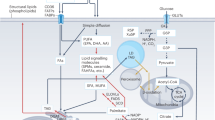

Intracellular lipid homeostasis relies on a precise balance of lipid synthesis, catabolism, and storage. The immune system defends the body by eliminating pathogens, which necessitates the rapid proliferation and differentiation of immune cells. This process requires increased lipogenic activity to provide essential building blocks and energy sources.188,189 Hence, any disruption in normal intracellular lipid synthesis and catabolism can significantly impair immune cell function. In this section, we elaborate on the critical role of intracellular lipid metabolism in directing immune cell differentiation and function (Fig. 6).

Intracellular lipid metabolism in immune cells. Intracellular lipid homeostasis is intricately regulated by multiple pathways, including glycolysis, the mevalonate pathway, the PPP, mTOR, and TLR signaling. Glucose is catabolized into acetyl-CoA and NADPH via glycolysis and the PPP, respectively. Acetyl-CoA enters the TCA cycle for FA synthesis (involving the enzymes ACLY, ACC, FASN, SCD, and ELOVLs), ceramide synthesis, and cholesterol production via the mevalonate pathway. NADPH is essential for lipid synthesis and energy supply. Both mTORC1 and mTORC2 activate SREBP1 expression and protein hydrolysis, with SREBP1 acting as an important transcriptional regulator affecting the activity of FA synthases (e.g., ACLY, ACC, and FASN). Excess FAs are converted into triglycerides through 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT), phosphatidic acid phosphatase 1 (PAP1) and DGAT. Triglycerides accumulate and gradually form droplet lipids, which serve as storage sites for lipids. Lipid catabolism occurs via FAO in mitochondria, with FAs transported by CD36, and droplet lipids enter the TAC cycle to produce energy via FAO. FA, cholesterol, and TLR signaling mediate the expression of nuclear receptor SREBPs and PPARs, thereby modulating lipid synthesis, catabolism, and storage in immune cells. Created in BioRender

Lipid synthesis

Recent research has emphasized that lipogenesis, which serves as a fundamental building block and energy source, is crucial for immune cell functionality and inflammatory responses.

Compared with resting B cells, B cells exhibit elevated expression of key FA biosynthetic genes, suggesting enhanced de novo synthesis. This includes the upregulation of genes encoding acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha (ACACA), elongase of very long chain FAs 1 (Elovl1), Elovl5, Elovl6, fatty acid synthase (FASN), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 2 (SCD2).190 When receiving activation signals, B cells redirect glucose to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to produce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and utilize acetyl-CoA from glucose oxidation. ACLY catalyzes the conversion of citrate produced in the mitochondria into acetyl-CoA, which is then utilized in the cytoplasm for the synthesis of FAs and cholesterol. Elevated ACLY levels and activity are observed in B cells stimulated with LPS. Accordingly, inhibiting ACLY function in these cells suppresses proliferation, impairs endomembrane expansion, and decreases CD138 expression and B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1).191 Furthermore, SCD is crucial for converting SFAs into MUFAs. Additionally, intrinsic SCD, particularly oleic acid, is essential for early B-cell development and germinal center (GC) formation during immunization and influenza infection in vivo.190

Transcriptomic analysis revealed marked upregulation of genes linked to the mevalonate pathway following CD40-induced B cell activation.192 A mechanistic study revealed that the mevalonate pathway is essential for cholesterol synthesis in B cells, with its key enzyme, HMG-CoA reductase, being susceptible to targeted inhibition by statins.193,194 Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), a significant intermediary in cholesterol biosynthesis, counteracts the inhibitory effects of statins on B cell antigen presentation.192 Moreover, Bregs rely on GGPP synthesis to facilitate IL-10 production triggered by TLR9 ligation. This process involves a GGPP-initiated phosphorylation cascade that modulates the PI3Kδ-AKT-glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) pathway, enhancing Blimp-1-dependent IL-10 synthesis.195

For T cells, the response of CD8+ T cells to infection relies on the extraction of acetyl-CoA from citrate via ACLY.196 Upon IL-12 stimulation, CD8+ T cells maintain high levels of IFN-γ through an ACLY-dependent pathway.197 However, under nutrient restriction conditions, the inhibition of ACLY significantly impairs IFN-γ production and reduces CD8+ T cell viability.198 Modulating the expression of ACLY in T cells has emerged as a new strategy for treating diseases, especially intestinal inflammation.199 Moreover, CD8+ T cells show increased lipid storage due to elevated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) activity. Inhibition of ACC activity can modulate T cell metabolism, increase T cell survival and multifunctionality, and effectively suppress tumor growth.200 FASN, a key enzyme in FA synthesis, deficiency leads to elevated MHC-I levels and promotes the killing of cancer cells by tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells.201 Inhibition of FASN also results in a decrease in the survival rate of memory CD8+ T cells but has no significant effect on the survival of effector CD8+ T cells.202 Additionally, FASN plays an important role in the functional maturation of Treg cells; loss of FASN impairs Treg cell function and further suppresses tumor growth.203

Activation of the mevalonate pathway is also critical for maintaining T cell function and stability by inducing T cell proliferation and suppressing IFN-γ and IL-17A levels.204 In addition, GGPP enhances STAT5 phosphorylation to maintain the function of Treg cells through IL-2.204 However, the application of statin drugs inhibits the mevalonate pathway and suppresses the activity of Treg cells.205 Interestingly, inhibiting the mevalonate pathway can also induce Th1 and cytolytic T cell responses, enhancing the antitumor immune effect.206

FASN is also essential for maintaining mature neutrophils, and its deficiency is associated with increased neutrophil apoptosis.207 Additionally, in autophagy-related 7 (Atg7)-deficient myeloblasts, treatment with pyruvate alone or exogenous free FAs (such as linolenic acid or a mixture of unsaturated and SFAs) is sufficient to restore normal glucose metabolism and rescue the defective neutrophil differentiation process.208

For DC maturation and function, DCs synthesize FAs from nonlipid precursors such as glucose and glutamine, which are converted into citrate and then into acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA is further processed by ACC1 into malonyl-CoA, which is elongated by FASN to form palmitic acid. The transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) regulates genes involved in this process. FASN supports the remodeling of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, which is crucial for DC maturation. Inhibition of FASN via ACC1 or FASN inhibitors impairs DC maturation and antigen-presenting functions. Additionally, FASN plays a role in DC-mediated antitumor immunity, and inhibiting FASN can restore DC function in the tumor microenvironment.209 In summary, targeting lipid synthesis to regulate immune cells has potential for treating the progression of various diseases.

Lipid catabolism

FAO is a critical catabolic pathway responsible for breaking down FAs into acetyl-CoA, a substrate for the mitochondrial TCA. Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1) plays a crucial role in FAO by promoting the transport of cytoplasmic FAs into mitochondria. Modulating FAO presents a promising strategy for addressing diseases associated with dysregulated fat and cholesterol metabolism, particularly in macrophages, as highlighted in several studies.210,211 Previous studies have implicated the blockade of CPT1 in the progression of atherosclerosis in macrophages due to increased expression of CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in LDL uptake and subsequent lipid accumulation.210

In T cells, the activation of FAO is correlated with increased AMPK activity, which supports the development of central memory CD8+ T cells, a subset that circulates through secondary lymphoid organs.212,213 Unlike effector CD8+ T cells, central memory CD8+ T cells primarily utilize de novo synthesized triacylglycerides from glucose for FAO, which rely on lysosomal acid lipase.202 Unlike IL-15 signaling, which enhances CPT1a expression to promote FAO, IL-7 signaling stimulates glycerol uptake for triacylglycerol (TAG) synthesis and FAO, contributing to central memory CD8+ T cell longevity.214,215 While genetic deletion of CPT1a in T cells does not impair memory CD8+ T cell formation, treatment with etomoxir, a CPT1a inhibitor, significantly reduces mitochondrial oxidative function. This contrast suggests that CPT1a-independent pathways may compensate for memory T cell generation, whereas etomoxir’s broader inhibition of FAO disrupts mitochondrial integrity, which is essential for this process.213,214,216

In obesity-related breast tumor models, FAO can be increased upon STAT3 activation, which reduces the effector capabilities of CD8+ T cells.217 However, despite exhibiting dysfunction, CD8+ T cells from an obesity-related mouse colon carcinoma 38 tumor model did not show elevated FAO genes, suggesting a context-dependent influence of the tumor environment on lipid metabolism regulation in tumor-infiltrating T cells.218 Thus, FAO is linked to the formation and function of memory T cells under inflammatory conditions.

Compared with other memory T cell subsets, TRM cells exhibit greater extracellular lipid uptake and depend on FAO for their generation and survival.219 Fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs) 4 and 5 regulate lipid transport and trafficking within cells. The absence of these proteins reduces mitochondrial oxygen consumption and diminishes virus-specific TRM cell accumulation in the skin, whereas FABP1 supports TRM cell accumulation in the liver.219,220 This metabolic shift toward FAO promotes TRM cell longevity, which is associated with improved antitumor immunity in gastric adenocarcinoma.221 Furthermore, FABP5 in Treg cells restrains mitochondrial DNA-triggered type I IFN signaling and promotes IL-10 production, highlighting the role of FABPs in modulating T cell responses within tissue microenvironments, including tumors.222

While rapidly dividing cells, such as activated T lymphocytes, predominantly rely on aerobic glycolysis for energy generation,223,224 the specific energy derivation mechanism in GC B cells remained unclear until recent studies. A groundbreaking investigation revealed that GC B cells primarily utilize FAO instead of glycolysis for energy production. Using isotope tracing techniques, researchers observed increased FA uptake by GC B cells in vivo and demonstrated that GC B cells cultured in vitro preferentially metabolize FAs over glucose to generate significant amounts of acetyl-CoA.225

Interestingly, FAO inhibition preferentially disrupts the recruitment of immature neutrophil populations (Ly6Glo/dim) that are influenced by pathogens,226 whereas neutrophil trafficking to infection sites requires CPT1a-dependent FAO.227 In neutrophils, FAO is particularly important during their differentiation, where autophagy plays a crucial role by degrading LDs to provide free FAs, thus maintaining metabolic energy balance. This autophagy-regulated FAO-oxidative phosphorylation pathway appears to be essential for providing ATP to meet the energy demands of the differentiation process.228

FAO also plays a critical role in DC function, particularly in the development of DC subsets and the regulation of immune tolerance. By breaking down FAs, FAO generates metabolic products such as acetyl-CoA, which provide energy for DCs and support their differentiation and activation.229 FAO not only influences the differentiation of DCs but also regulates their function. ROS derived from FAO may impair DC antigen presentation, but antioxidants can mitigate this negative effect.230 The regulatory mechanisms of FAO and its effects on different DC subsets require further investigation to better understand its complex role in immune responses. These findings indicate that FAO mediates the growth, development, activation and function of immune cells.

Lipid storage

Within immune cells, LDs serve as structural indicators of the immune response.231,232 Treg cells exhibit a higher LD content than conventional T cells do.233 Diacylglycerol acyl transferase (DGAT) catalyzes the reaction between DAG and FAs, mediating the formation of LDs. Inhibiting DGAT1 activity disrupts Foxp3 induction, indicating the potential role of LDs in the formation or maintenance of Treg cells.233 Moreover, the function of T cells can be indirectly influenced by the LD content of other immune cells. For example, enhancing the synthesis of LDs in DCs can affect the ability of T cells to initiate an antitumor response.234

In tumor cells, the activation of intracellular signaling pathways enhances FA synthesis and LD accumulation, leading to senescence in effector T cells.235 These senescent T cells, characterized by dysfunction within the tumor microenvironment, exhibit changes in lipid species composition and an accumulation of LDs. This accumulation is correlated with the increased activity of group IVA phospholipase A2. Inhibiting the activity of this enzyme has been shown to reverse T-cell senescence, resulting in reduced tumor size and prolonged survival in tumor-bearing mice.31

While T cells have traditionally been the focus, macrophages have recently garnered increased attention. Agonists for TLRs, such as TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7, have been found to increase LD counts and increase the expression of key proteins involved in LD biogenesis, such as perilipin 2 and DGAT2, in both thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal mouse macrophages and human monocyte-derived macrophages.236 In addition, TLR2 is crucial for stimulating LD formation in macrophages in response to infections by pathogens such as Trypanosoma cruzi, Mycobacterium bovis BCG, and Histoplasma capsulatum.237,238 These findings suggest that LD formation in myeloid cells is a consequence of host defense mechanisms orchestrated by pattern recognition receptor activation.

Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) is recognized as a critical enzyme for triglyceride breakdown within cell LDs. Inhibition of ATGL-mediated lipolysis in macrophages enhances lipid accumulation and hampers the production of the cytokine IL-6.239,240 In ATGL-null macrophages, increased FA uptake attempts to compensate for reduced lipolysis, which is crucial for ATP synthesis and effective phagocytosis.241 Therefore, targeting enzymes such as ATGL, which are involved in lipid metabolism, has therapeutic potential for diseases characterized by dysregulated lipid metabolism and inflammation, including atherosclerosis and metabolic disorders.239,240

LDs are also crucial for DC function, particularly in T cell activation. In granulocyte‒macrophage colony‒stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-induced bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs), LD accumulation is correlated with increased expression of IFN-γ-induced GTPase (IGTP).242 GM-CSF-derived BMDCs lacking IGTP fail to accumulate lipid droplets and exhibit defects in antigen cross-presentation and CD8+ T cell activation. IGTP interacts with adipocyte differentiation-related proteins (also known as perilipin-2) on LDs, preventing phagosome degradation and promoting immune function.242 Additionally, changes in LD composition can affect DC immune function. For example, tumor-derived factors alter the lipid composition of LDs and suppress DC responses to CD8+ T cells.243

In summary, different immune cells rely on distinct lipid metabolic environments to fulfill their functional needs. M1 macrophages enhance the immune response through glycolysis and lipid synthesis, upregulating ACLY, ACC, and FASN to generate proinflammatory lipid molecules such as prostaglandins while promoting neutral lipid storage via perilipin 2. In contrast, M2 macrophages rely on FAO to maintain anti-inflammatory functions, with high activity of CPT1 and acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and lower levels of lipid synthesis and LD formation.92 Activated T cells upregulate ACLY, FASN, SREBP2, and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coA reductase (HMGCR) to increase lipid and cholesterol metabolism, supporting membrane phospholipid synthesis and immunological synapse formation, primarily through glycolysis, although FAO is crucial for their memory function.35 Additionally, activated T cells form limited LDs, with lipids primarily used for membrane expansion rather than storage.35 Activated B cells upregulate FASN and cholesterol synthesis to support proliferation, endoplasmic reticulum expansion, and antibody secretion, potentially supplementing metabolic demands through increased FAO. However, B cells have limited LD formation capacity, weak perilipin 2 expression, and low lipid storage levels.244 Neutrophils require FASN for survival and differentiation, with FAO supporting energy production during differentiation. Disruption of lipid metabolism or FAO impairs neutrophil function and recruitment to infection sites.207,208 DCs rely on FASN and FAO for maturation and antigen presentation. Inhibition of these pathways impairs DC function and antitumor immunity. Lipid droplets in DCs are important for T cell activation, and their composition can affect immune responses.209,230 Overall, lipid metabolism, including FASN, FAO, and LDs, plays a key role in immune cell differentiation and function, with potential therapeutic implications for immune modulation.

Regulatory mechanisms of lipid metabolism in immune cell responses

Immune cells rely on lipids for membrane structure, energy, and signaling, making lipid metabolism essential for immune responses.245 This process is tightly regulated at multiple levels, including genetic, epigenetic, posttranscriptional, and posttranslational levels, ensuring that lipid profiles are dynamically adjusted to meet the metabolic demands of immune cell activation and inflammatory responses.246,247,248,249 Disruption of these regulatory mechanisms can contribute to various diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and fatty liver disease, especially cancer. This chapter explores the different regulatory mechanisms involved in lipid metabolism within immune cells, with a focus on genetic regulation, epigenetic and posttranscriptional modulation, and PTMs.

Genetic regulation

Lipid metabolism in immune cells is governed by a variety of genetic regulators, including transcription factors, nuclear receptors, and enzymes that control lipid biosynthesis, oxidation, and storage. These genetic regulators ensure that immune cells can adapt to various environmental cues and immune stimuli by altering lipid metabolic pathways accordingly.

One key regulatory factor is the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family, particularly PPAR-γ and PPAR-α (Fig. 6). PPAR-γ is a ligand-activated nuclear receptor that is expressed primarily in macrophages, where it regulates FA uptake and storage while also modulating inflammation and promoting immune tolerance.250,251,252 PPAR-γ exerts significant anti-inflammatory effects by regulating triglyceride metabolism, lipid uptake, cholesterol efflux, and macrophage polarization and inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways.250 Furthermore, through posttranslational modifications (PTMs), PPAR-γ modulates its interactions with transcriptional ligands and coactivators or corepressors, thereby influencing the regulation of downstream target genes.250 For example, studies have shown that PTMs of PPAR-γ regulate lipid synthesis in response to wound microenvironment cues and that metabolic reprogramming coordinates the function of reparative macrophages.253 Additionally, PPAR-γ is a required transcription factor for FAO induction in the tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization process, which promotes tumor growth.254

PPAR-α is essential for T cells, where it promotes FAO and provides the energy required for immune cell activation and function. For example, selective activation of PPAR-α enhances free FA metabolism and downregulates the gene expression of Il17a and Il23r, thereby suppressing the metabolic program of Th17 cells. This mechanism may represent a viable therapeutic option for autoimmune diseases.255 Furthermore, fenofibrate (a synthetic ligand of PPAR-α) regulates Th1/Th17/Treg cell responses by activating PPAR-α/LXR-β signaling.256

The immunogenicity of DCs is regulated by PPAR-γ. The activation of PPAR-γ in DCs inhibits the expression of EBI1 ligand chemokines and CCR7, both of which play key roles in DC migration to lymph nodes.257 Studies have also shown that the number of eosinophils is increased in PPAR-α-deficient mice, whereas the activation of PPAR-γ can reduce the number of eosinophils. In addition, the activation of both PPAR-α and PPAR-γ not only inhibits eosinophil chemotaxis but also diminishes their antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.258

Another critical genetic regulator is SREBP, which responds to cellular lipid levels and regulates the expression of genes involved in lipid synthesis (Fig. 6).259,260 Studies have shown that hepatic SREBP signaling mediates circadian communication within the liver and that lipidomic changes dependent on SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) lead to increased metabolic rhythmicity in liver macrophages.261 In the absence of SCAP-mediated activation of SREBP1a, increased M1 macrophage polarization results in reduced cholesterol efflux downstream of 25-hydroxycholesterol (HC)-dependent LXRα activation.262 Moreover, mouse macrophages lacking SREBP1a, when exposed to bacterial LPS triggering TLR4 activation, exhibit impaired lipogenesis, resulting in compromised innate inflammatory responses marked by reduced cytokine production.263 SREBP1a promotes the biosynthesis of anti-inflammatory FAs by regulating lipid metabolism in macrophages, thereby inhibiting inflammation.264

For T cells, during viral infections, SREBPs are pivotal in regulating CD8+ T cells function through initiating lipogenesis to support membrane synthesis.265,266 Additionally, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-raptor activates lipogenic pathways via SREBP1c, increasing cell proliferation and facilitating Th2 cell differentiation.267 In addition to Th2 cells, Th17 cells depend on ACC-mediated lipogenesis for phospholipid production in their plasma membranes, a process that suppresses Th17 cell development while promoting Treg formation.268,269 Additionally, SREBP activity is reportedly upregulated in tumor-infiltrating Tregs, and blocking SREBP signaling disrupts the activation of PI3K in these cells, further suggesting that lipid signaling enhances the functional specialization of Tregs in tumors.203

Moreover, metabolic reprogramming in activated B cells requires SREBP signaling. SREBP signaling in B cells is crucial for antibody responses and the generation of GCs, memory B cells, and bone marrow plasma cells. Under mitogen stimulation, SCAP-deficient B cells fail to proliferate, and lipid rafts are reduced.270 These genetic regulators collectively fine-tune lipid metabolism in immune cells, providing essential support for their immune functions while also offering potential targets for therapeutic intervention in immune-related diseases. Currently, the regulatory mechanisms of lipid metabolism in immune cells are not fully understood, and research faces challenges such as model limitations, the complexity of lipid metabolic pathways, difficulties in drug target development, and individual variability. Future studies need to explore these mechanisms in greater depth and overcome these obstacles to advance the application of lipid metabolism regulation in the treatment of immune-related diseases.

Epigenetic and posttranscriptional regulation

In addition to genetic regulation, lipid metabolism in immune cells is also controlled by epigenetic modifications and posttranscriptional mechanisms, providing further layers of fine-tuning. These regulatory processes do not alter the DNA sequence but instead modify gene expression through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the action of noncoding RNAs.

DNA methylation is an important epigenetic modification that influences lipid metabolism by repressing the expression of certain genes, particularly through the inhibition of transcription factor activation. The selective activation of adipose tissue macrophages is controlled by DNA methylation at the PPAR-γ promoter. DNA methylation at the PPAR-γ promoter blocks the alternative activation of macrophages, whereas high levels of DNA methylation promote inflammatory responses and insulin resistance.271 Furthermore, studies have shown that histone modifications at the PPAR-γ promoter can influence the production of cytokines and autoantibodies. For example, the deletion of HDAC9 in mouse CD4+ T cells increases histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9ac) and H3K18ac at the PPAR-γ promoter, promoting a shift in T cell cytokine production toward a more anti-inflammatory profile while reducing the production of anti-dsDNA autoantibodies by B cells.272

Studies have shown that targeting methylation-related genes and proteins, such as DNA methyltransferase 3beta and TET methylcytosine dioxygenase 3 (TET3), can increase DNA methylation, thereby inhibiting PMA-induced NETosis.273 During the differentiation of DCs from monocytes, the expression of DC-SIGN (CD209) is linked to a reduction in DNA methylation.274 Treatment of monocyte-derived DCs with the methyltransferase inhibitor 5-azacytidine increases the levels of the costimulatory molecules CD40 and CD86, which, in turn, induce activated T cells to express the cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17A.274

Noncoding RNAs, particularly microRNAs, are vital regulators of lipid metabolism. microRNAs can bind to mRNA transcripts and inhibit their translation or promote their degradation, thus modulating lipid metabolic pathways. For example, miR-33 is an intronic microRNA within the gene encoding the SREBP2 transcription factor. The inhibition of miR-33 has been shown to promote cholesterol efflux in macrophages by targeting the cholesterol transporter ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1), thereby reducing the burden of atherosclerotic plaques.275 In addition, the overexpression of the long noncoding RNA homeobox transcript antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) can effectively reduce lipid uptake and suppress immune responses by downregulating the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 during foam cell formation. Mechanistically, HOTAIR alleviates foam cell formation by inhibiting the expression of miR-19a-3p.276 Other studies have shown that oxidized LDL induces the expression and release of miR-155 in macrophages and that miR-155 is essential for mediating oxidized LDL-induced lipid uptake and ROS production in macrophages.277 Reducing miR-155-5p levels and subsequently increasing the expression of LXRα leads to increased ABCA1- and ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux, which promotes macrophage polarization to the M2 phenotype.278

MiR-223 controls neutrophil function by inhibiting the transcription factor myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2 C (MEF2C). In mice, the absence of miR-223 results in a twofold increase in hyperreactive neutrophils, promoting acute inflammation in multiple organs through the involvement of myeloperoxidase and ROS.279 Furthermore, miR-130a is implicated in neutrophil development. The overexpression of miR-130a downregulates CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-ε (C/EBP-ε), reducing the synthesis of secondary granule proteins such as lactoferrin, cathelicidin, and lipocalin-2, which leads to the differentiation of neutrophils with an immature phenotype.279

Various microRNAs play important roles in the differentiation, activation, and functional regulation of DCs. For example, miR-144/451 directly targets interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), inhibiting its expression and reducing DC activation.280 In contrast, miR-148a targets MAF bZIP transcription factor B, promoting the differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs.281 Additionally, miR-9 is upregulated in bone marrow-derived DCs and conventional DC1s, promoting DC activation and enhancing their ability to stimulate T cells.282

microRNAs play crucial roles in regulating mast cell differentiation, proliferation, survival, apoptosis, stress responses, effector functions, and the resolution of immune responses.283 For example, miR-210 and miR-221-3p participate in the pathogenesis of asthma by promoting mast cell activation and Th2 cytokine production. In contrast, miR-143 targets IL-13Rα1 to reduce mast cell activation and subsequent allergic reactions. More detailed information can be found in the referenced study.283

These epigenetic and posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms add another layer of complexity to lipid metabolism, allowing immune cells to adapt to environmental stimuli and modulate their function in response to immune challenges.

Posttranslational regulation

PTMs are another crucial aspect of regulating lipid metabolism in immune cells. PTMs such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination control the activity, stability, and interactions of lipid-metabolizing enzymes, enabling immune cells to rapidly adjust their metabolic pathways in response to immune activation.

Phosphorylation plays a central role in lipid metabolism regulation. AMPK, an energy-sensing enzyme, regulates lipid metabolism by phosphorylating key enzymes involved in FAO and synthesis. Research has shown that the accumulated 25-HC in lysosomes competes with cholesterol for binding to GPR155, inhibiting the kinase mTORC1, which leads to the activation of AMPKα and metabolic reprogramming. AMPKα also phosphorylates STAT6 at Ser564 to increase STAT6 activation and arginase 1 production, suggesting that cholesterol 25-hydroxylase acts as an immune metabolic checkpoint that can manipulate macrophage fate to reshape CD8+ T-cell surveillance and antitumor responses.284,285 Additionally, activation of the ROS-AMPK-mTORC1-autophagy pathway enhances M1-to-M2 polarization, cholesterol efflux, and the anti-inflammatory response both in vitro and in vivo in murine bone marrow-derived M1 macrophage (BMDM1) cells.286 Notably, AMPK activation also increases mitochondrial FAO in activated CD4+ T cells, promoting natural Treg cell differentiation. Furthermore, AMPK agonists promote FAO and natural Treg differentiation via β1-adrenergic receptor signaling.287

Ubiquitination regulates lipid metabolism by targeting enzymes for degradation, thereby controlling their levels and ensuring the balance of lipid metabolic processes during immune activation to prevent metabolic dysregulation. For example, the known protein phosphatase protein tyrosine phosphatase B (PtpB) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate in host cell membranes, which disrupts the membrane localization of cleaved gasdermin D (GSDMD), thereby inhibiting cytokine release and pyroptosis in macrophages. This phosphatase activity requires PtpB to bind to ubiquitin.288 Disruption of phosphatase activity or the ubiquitin-binding motif of PtpB can enhance host GSDMD-dependent immune responses and reduce the survival of intracellular pathogens.