Abstract

Fabrication of pores at the atomic scale remains a significant challenge in modern nanotechnology, hindering the study of ion transport and molecular dynamics in confined spaces. Here, we introduce a chemically controllable break-membrane approach that enables the repeated formation and closure of nanoscale pores in SiNx membranes through manipulating the in-pore electrochemical reaction conditions by transmembrane voltage. Ionic current measurements reveal distinct conductance features that are consistent with ion dehydration and transport through highly confined channels approaching sub-nanometer dimensions. The scalable nature of this platform, which allows multiple pores to be actuated simultaneously, offers a powerful tool for probing ion transport and fluid dynamics in extreme confinement. Beyond advancing fundamental understanding of ion transport and fluid dynamics, this chemically driven membrane system holds promise for applications in single-molecule sensing, neuromorphic computing, and nanoreactor design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evolution of life has created ion channels for the maintenance of non-equilibrium physicochemical environments within cells to support biological functions in physiological matrices1,2. The channels exist in transmembrane proteins featuring ångström-sized constrictions of atomically precise geometries dictated by their ingenious molecular structures3,4,5,6. Their unique architecture enables permselective transport by admitting only the ions of sufficiently small sizes to traverse the minuscule conduits. Another key function is gating, where conformational changes in protein structure open or close the channels in response to external stimuli, generating action potentials via the selective ion flux crucial for intercellular communication and perception7,8,9.

Inspired by nature, advances in nanotechnology have driven growing interest in mimicking the distinct capability of biological ion channels with solid-state nanopores10,11,12. Self-organized nanoporous structures in synthetic membranes are found to serve as a nanofluidic system with permselectivity13, filtering specific types of ions for desalination and osmotic power generation14,15. Meanwhile, electron and ion beam milling allows the fabrication of single-digit nanochannels in dielectric membranes16,17, enabling studies of ion transport at the individual pore level18,19. Ångström-scale slits are another promising platform20 comprising a two-dimensional channel of sub-nanometer heights in stacked 2D materials with rich transport properties involving ion pairing21 and quantum friction22. These emerging nanostructures have proven useful for investigating the transport phenomena in confined spaces at a scale relevant to the biological ion channels. However, probing ion flow in such infinitesimal conduits remains challenging due to the difficulty of creating such confined spaces with reproducible precision, limiting the number of channels available for systematic study23,24. In contrast, we herein introduce a chemically driven break-membrane strategy that exploits voltage-controlled precipitation and dissolution of metal phosphates inside a lithographically defined nanopore to autonomously create, seal, and recreate sub-nanometer conduits. This voltage-facilitated in-pore chemistry enables repeated pore formation with high stability over hundreds of cycles and reveals rich ion-transport phenomena, including spontaneous ionic spiking reminiscent of biological channels, tunable pore sizes governed by solution composition and pH, and selective transport of chaotropic or kosmotropic ions through pores approaching the scale of dehydrated species. By providing a scalable route to generate and study thousands of ångström-scale pores within a single solid-state nanopore, this framework establishes a new experimental platform to probe ion dynamics at the limits of confinement for developing chemically active membranes relevant to single-molecule sensing, adaptive iontronics, and nanoscale reactors.

Results

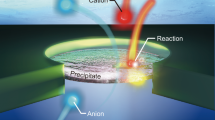

The method uses a nanoscale hole of diameter dpore in a silicon nitride membrane (thickness is 30 nm, otherwise stated) as a nanoreactor25,26,27,28. The in-pore reaction is induced by the ion flux under the transmembrane voltage Vb with the trans and cis compartments filled with 2 M MnCl2 and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), respectively (Fig. 1a, see also Supplementary Table 1). As Mn2+ cations electromigrate into the pore under negative voltage, they react with the phosphoric acid anions in PBS to undergo nucleation and growth of manganese phosphates. Eventually, the precipitated layer completely seals the nanopore, strongly suppressing the ionic current Iion during the negative Vb scans (Fig. 1b–d). Turning the voltage to positive, on the other hand, the precipitate is dissolved by the acidic MnCl2 solution of pH 4.2, reverting the nanopore to a fully opened state. The resulting diode-like behavior features a high Iion rectification ratio rrec = I+1/I−1 of over 30,000, where I+1 and I−1 are the ionic current at Vb = +1 V and −1 V, respectively29. The sequence of chemical reactions is stable over 756 voltage scanning for >10 hours, suggesting the robust nature of the voltage-controlled precipitation/dissolution processes inside the nanopore (Fig. 1e, see also Supplementary Fig. 1)29,30.

a Schematic illustration depicting the working principle of a voltage-gated nanopore. It consists of a nanopore of a lithographically defined diameter in a thin SiNx membrane, separating cis and trans compartments filled with different salt solutions. The transmembrane voltage Vb generates a flux of cationic and anionic reactants into the nanopore, inducing chemical reactions for nucleation and growth of a nanoprecipitate layer therein. The reaction process is monitored via the measurements of the ionic current Iion. b Iion–Vb characteristics obtained for a 100 nm-sized SiNx nanopore with cis and trans filled with 2 M MnCl2 and PBS, respectively (open circles: positive Vb scan; solid circles: negative Vb scan). As depicted in the insets, negative voltage brings Mn2+ and (PO4)3− into the pore for the precipitation of manganese phosphates, thereby suppressing the ion transport. Conversely, a positive voltage reverses the ion flux to stop the precipitation reaction. Simultaneously, the manganese phosphate dissolves into the acidic MnCl2 solution, returning the pore to the fully opened state. c, d Stability of the in-pore reactions. Iion–Vb curves are highly reproducible over 756 cycles of voltage scans from −1.5 V to 1.5 V in ~10 hours (c, d). The curves are presented in the form of a two-dimensional histogram, where the color coding denotes the counts of data points in each bin of size 20 nA and 0.02 V. e Rectification ratio rrec at Vb = ±1 V in each of the 756 Iion–Vb curves. The variation in rrec is attributable to a change in the ion concentration due to water evaporation and residual precipitates remained undissolved on the pore wall surface during the 10 hours of measurement. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The precipitated layer activates repetitive formation of small pores. This can be found as conductive Iion spikes stochastically fired under constant negative transmembrane voltage (Fig. 2a, see also Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), the feature of which resembles the spontaneous activity of ionic channels31. They are characterized as pulse signals of amplitude Ip and width td (Fig. 2b, c). The underlying mechanism involves the interplay of in-pore chemistry and voltage-driven ion transport (Fig. 2d). Precipitation reaction under negative Vb fills the nanopore with a phosphate manganese film. Once complete sealing occurs, meanwhile, the applied voltage becomes ineffective in delivering ionic reactants. As a result, the dissolution of the precipitated layer on the cis side begins to reduce its thickness isotropically down to a critical level, thereby penetrating a small hole (Supplementary Fig. 4). Concurrently, the focused electric field triggers the precipitation reaction by electrostatically dragging manganese ions and phosphoric acids to close the pore. The chemical reaction-mediated piercing suggests a self-regulating mechanism in which the dissolution-driven thinning of the phosphate layer occurs uniformly across the precipitate film under the given pH conditions, thereby stabilizing the film at a thin thickness in a steady state, irrespective of the applied voltage. The rate of pore piercing fp is presented by the time interval Δt between two consecutive Iion spikes. The rate of pore piercing fp is presented by the time interval Δt between two consecutive Iion spikes. Fitting the Δt distribution with a Gaussian peak given as

where A and w are the peak area and width at half maximum, respectively, the characteristic fp = Δt−1 is estimated to be ~10 Hz from the peak position xc for the case in the MnCl2/PBS system under Vb = −1.1 V (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). While similar features were observed in voltage-driven motions of nanoprecipitates at the tip of a nanopipette25,26,27,28,30, they were unable to seal the channel completely, leading to random oscillations in the base level current. In contrast, the nanopore reactor in the thin SiNx membrane provides finer control over in-pore chemical reaction conditions, enabling the repeated formation of small pores through the autonomous nanoelectrochemistry29.

a Ionic current trace under the transmembrane voltage of −1.1 V applied to a 100 nm nanopore in a 30-nm-thick SiNx membrane with MnCl2 (cis)/PBS (trans) solution arrangement. The precipitated phosphate layer sealed the pore, suppressing Iion to below 100 pA. At the same time, conductive pulses emerged stochastically, suggestive of repeated opening and closure of small pores. b Magnified view of the conductive Iion spikes, characterized by the height Ip and width td representing the size and the lifetime of the small pores, respectively. On the other hand, the time interval Δt characterizes the frequency of the pore creation. a–c denote the three stages of the pore evolution. c Scatter plots of Ip as a function of td. d Breathing mode of the voltage-gated nanopore comprising the three processes from (a–c). When the precipitate completely seals the nanopore, the ionic current becomes silent (a). During this stage, the transmembrane voltage is ineffective in causing the precipitation since it generates no ion flux. Meanwhile, the dissolution reaction at the acidic MnCl2 solution side proceeds to gradually narrow the nanoprecipitate layer. As a result, a small pore is pierced at a certain moment, causing the rapid rise in Iion (b). Simultaneously, the focused electric field starts to feed the reactant ions into the pore for the precipitation, leading to the closure of the pore (c). These three stages of chemical reactions occur autonomously to repeatedly form and close small pores, which is observed as the firing of Iion spikes. e Logarithmic Δt histogram indicating the pore piercing frequency of ~10 Hz.

This breathing mode of the precipitated nanopore membrane is tunable by the ionic reactants on the cis side (Fig. 3a). In the presence of MgCl2 (2 M), for instance, the in-pore reaction equilibrium shifts toward dissolution, preventing the precipitate layer from sealing the nanopore. Conversely, non-dissolvable aluminum phosphates are formed with AlCl3 (2 M). For these salts, the breathing mode is absent, resulting in either a partially occluded or permanently sealed nanopore. Meanwhile, the reaction kinetics in CaCl2 (2 M) promote spontaneous membrane piercing, demonstrating conductive Iion spikes. While the overall feature is similar to that observed in MnCl2, the pulses are found as relatively large in CaCl2, as evident in the Ip versus td scatter plots displaying clusters of data above 10 nA with CaCl2 (Fig. 3b, c). The result is similar in an equimolar mixture of MnCl2 (1 M) and CaCl2 (1 M), suggesting the coexistence of manganese and calcium phosphate precipitation reactions within the nanopore (Fig. 3d).

a Ionic current traces with different salts in cis. MgCl2 can seal the nanopore only partially (orange), due to the relatively faster dissolution reaction than precipitation. On the other hand, AlCl3 synthesizes insoluble precipitates to seal the pore, keeping the ionic current in a silent mode (skyblue). Intermediate dynamic reaction balance is achieved with MnCl2 (red) and CaCl2 (green), exhibiting breathing mode via the chemically-driven spontaneous pore piercing. b, c Ip versus td scatter plots for MnCl2 (a) and CaCl2 (b) added to cis. Data clustered at above 5 nA in the case of CaCl2 indicates the larger pores created than those in MnCl2, manifesting the distinct in-pore chemistry with Mn2+ and Ca2+. d Ip–Vb scatter plots in the mixture of CaCl2 (1 M) and MnCl2 (1 M). e Ionic current showing three giant Iion spikes. f A close-up view of a giant spike, revealing a specific pattern in the ionic current changes. The Iion range is limited to a maximum of 12 nA to highlight fine features immediately preceding the spike. Only a portion of the giant spike is shown, whereas its actual amplitude exceeds 50 nA, as depicted in (e). This burst mode of Iion spiking comprises four stages. It begins with a silent state for ~0.2 s, followed by small spike firing for ~1.5 s. Subsequently, larger spikes are fired. Soon after, it caused a giant spike. These processes continue to fire giant spikes at a certain period. g Underlying mechanism of the burst mode. It begins with synthesis of the thick precipitate layer completely sealing the nanopore to cause the silent Iion feature (a). Meanwhile, the layer is thinned gradually via dissolution (b), initiating the small pore piercing to fire the relatively weak Iion spikes (c). As the precipitate layer is thinned further, the small pores tend to be created at higher rates, leading to coalescence into large pores (d). Eventually, the layer is partially ruptured to generate a giant spike (e). What follows is the in-pore precipitation to repair the precipitate layer (a). The series of reaction processes takes place to cause the repeated bursts of the ionic current traces with CaCl2.

Compared to the stochastic nature of pore piercing in MnCl2, the spontaneous activity in CaCl2 demonstrates a distinct pattern (Fig. 3e). Being sealed by calcium phosphate under negative transmembrane voltage, the ionic current remains silent for ~0.2 s (Fig. 3f). This is followed by small conductive pulses, resembling those observed in MnCl₂, which persist for ~1.5 s. Subsequently, larger pulses begin to appear, culminating in a single giant spike. After that, the Iion state returns to the silent mode. The cycle of events repeats periodically to fire giant ionic spikes roughly every 4 s (Supplementary Fig. 7).

This burst mode can be ascribed to the slow reaction rate of the calcium phosphate precipitation (Fig. 3g). Initially, calcium phosphate blocks the pore, preventing ion flux through the membrane. Since it inhibits the ion transport for further precipitation, the precipitate layer undergoes isotropic corrosion, leading to gradual thinning to stochastic small pore piercing. What is different from the case of MnCl2/PBS system is that the precipitation dynamics cannot compensate for the rapid dissolution to repair the phosphate layer under corrosion. As a result, small nanopores tend to merge into larger ones. Ultimately, the phosphate membrane partially or fully ruptures, either spontaneously or under the influence of electroosmotic flow32, producing a giant Iion spike. This resets the reaction system by resealing the SiNx nanopore through phosphate precipitation.

Since the pores formed by the cyclic in-pore chemical reactions are anticipated to be at the ultimate scale, ion transport therein likely exhibits intriguing size effects intrinsic to the confined space. Molecular dynamics simulations predict the notable influence of hydrated water molecules around ions on their mobility when passing through sub-nanometer-scale fluidic channels33,34. This factor is particularly critical for understanding and controlling the ion blockade behavior of biomolecules in the presence of ionic reagents belonging to the so-called Hofmeister series35,36,37. In this context, we examined the ion transport characteristics using F− and I− as chaotrope and kosmotrope, respectively, which are expected to form more ordered and disordered hydration shells compared to Cl-38. These halide anions are added on the trans side as KF (1 M) and KI (1 M) in PBS (Fig. 4a) to keep the electrolyte buffer pH and the concentration of the phosphoric acid almost unchanged for the balance between precipitation and dissolution reactions to allow the spontaneous pore piercing. In both cases, the SiNx nanopores are sealed with the precipitates at Vb = −0.5 V in the presence of 2 M MnCl2 on the cis side.

a Adding kosmotrope of KF into trans elevates the frequency of ionic current spiking (green) than without KF (blue), which is attributed to the more facile electromigration of F− through the pores, due to its smaller ionic radius than Cl-, under Vb = −0.5 V. KI in trans, on the other hand, produces negative Iion spikes. b Spiking frequency fp with the chaotrope and kosmotrope. Blue and red bars denote fp of positive and negative spikes, respectively. c, Logarithmic Ip histogram with (blue) and without KF (skyblue) in trans. d–f Ip versus td scatter plots with KI (d), no KI nor KF (e), and with KF (f) in trans. Pink and skyblue plots indicate positive and negative spikes, respectively. Note that positive spikes are detected with KI (d) due to the presence of Cl− contained in PBS. g A result of adding KI and KF, showing both the characteristic features of larger positive spikes and the negative spiking derived from the F− and I− transport, respectively.

The addition of the chaotropic and kosmotropic agents induces distinct changes in the spontaneous activity of the phosphate membranes. For example, KF facilitated the firing of the ionic spikes, enhancing fp by a factor of 6 (Fig. 4b), while also increasing their amplitude (Fig. 4c). Here, F− is a kosmotrope bearing ordered water molecules to form a thicker hydration shell39,40. The fact that F− enabled larger conductance indicates a minor role of the energy barrier in disrupting the hydration structure under the focused electric field. Given its smaller ionic radius, instead, the result suggests the higher mobility of F_ in the infinitesimal pores compared to Cl-.

In contrast, KI induces negative pulses (Fig. 4d–f). The comparatively large ion radius of I− restricts its passage through the small channels24,39. As their presence at the entrance impedes the transmembrane ion flux, the focused electric field accumulates other anions and cations at the pore. Upon the closure of the channel by the precipitation reaction, the stored ionic charges relax to cause transient changes in the ionic current. These contrasting features of the chaotropic and kosmotropic ions coexist in a mixture of KI (0.5 M) and KF (0.5 M) in PBS, manifesting the tunability of the ionic flow in the infinitesimal channels by the ion radii (Fig. 4g).

The transmembrane voltage dependence of the conductive pulses provides further insight into the ion transport characteristics. The ionic current traces are silent under small negative Vb, suggesting an insufficient electric field to squeeze the hydrated ions into the pierced channels before they are closed via the precipitation reaction. As the negative voltage increases, meanwhile, ionic current spikes become observable, resembling the ionic Coulomb blockade characteristics of MoS2 sub-nanometer-pores41,42. Noticeably, the threshold voltage for observing the conductive pulses is smaller for MnCl2 than CaCl2 (Fig. 5a, b, see also Supplementary Figs. 8–10). Since both solutions have the same concentration of Cl− on the trans side, the difference manifests in the distinct roles of Mn2+ and Ca2+. According to the Coulomb blockade theory, ions of the same valency should experience energy barriers of similar heights41,42. The difference in the threshold voltage is, thus, ascribed to the hydration energy. According to the Hofmeister series, however, Mn2+ is more kosmotropic than Ca2+43, indicating the interplay of factors beyond the Coulomb blockade and hydration effects in the pore piercing to ion translocation processes.

a, b Iion traces under various Vb with MnCl2 (a) and CaCl2 (b) in cis. No spikes are observed at Vb smaller than −0.2 V and −0.5 V for MnCl2 and CaCl2, respectively. c Logarithmic Ip histograms with MnCl2 under varying Vb revealing no peaks. d Logarithmic Ip distributions with KF added to trans. Pronounced peaks signify the formation of small pores of a well-defined size. Solid curves are Gaussian fits to the peaks. e Plots of the peak positions in (d) as a function of Vb. The red line is a linear fit. The dashed line points to zero current for the sake of visualizing the voltage offset. The inset image depicts the size of the pore estimated from the voltage dependence of Ip, allowing F− translocation in its dehydrated form. f, g Ensemble-averaged ionic current spike showing the onset (f) and tail lineshapes under different Vb: 0.4 V (red), 0.5 V (green), 0.6 V (blue), 0.7 V (purple), 0.8 V (dark yellow), 0.9 V (orange), and 1.0 V (pink). h The slope r of the ionic current rise (red) and fall (blue) in (f, g), respectively.

Determining the size of the pores is crucial. In the MnCl₂/PBS system, nevertheless, the Ip distributions exhibit no evidence of well-defined channel structures formed by the membrane piercing mechanism (Fig. 5c, see also Supplementary Fig. 11), which is attributed to an energy barrier arising from Coulombic interactions and steric effects of hydration shells42. While ions are able to transit the pierced pores under the energy barrier at Vb > 0.1 V, their height likely depends on the arbitrary size of the pores42, resulting in the featureless Ip distributions observed. Similar pulse height distributions are found in the CaCl₂/PBS system, except for giant spikes (~40 nA) associated with membrane rupture in the burst mode (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). Maxwell–Hall theory44 describes the ionic conductance (Gpore) of a cylindrical pore with diameter dpore and depth Lpore as Gpore = (Racc + Rpore)−1, where Racc = ρ/dpore is the access resistance45,46 and Rpore = 4ρLpore/πdpore2 is the resistance inside the pore, with ρ denoting the solution resistivity. This model accurately predicts pore conductance when counterion conduction47 and fluid dynamics48 have negligible effects on in-pore ion flux, as is the case during membrane rupture under high salinity. From the 40 nA heights of the giant spikes and ρ of 8.3 S/m (Supplementary Fig. 14), therefore, Rpore is estimated to be 12.5 MΩ, which suggests the opening of nanopores with diameters around 10 nm with the CaCl2/PBS configuration.

Unlike manganese and chloride ions, F− was found to electromigrate through the ångström-scale pores without significant steric impedance. This is evident from the log10Ip distributions with a pronounced peak shifting monotonically to higher current levels with Vb (Fig. 5d, see also Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16). Plotting the peak positions, assessed by Gaussian fitting to the histograms, the characteristic ionic current states are revealed to scale linearly with the transmembrane voltage (Fig. 5e with a fitting curve Ip = I0 + rVb, where I0 and r are the intercept and the slope, respectively), which signifies the F− transport through a channel of a well-defined structure with negligible contributions from the Coulomb blockade- and hydration-derived energy barriers42. The differential conductance obtained from r is 3.9 nS. Neglecting the effect of pore length, verified by the measurements using SiNx nanopore membranes of different thickness (Supplementary Fig. 17), the diameter of the pores is calculated from Racc to be 0.39 nm (Fig. 5e inset) 24 with ρ = 0.1 Ωm for 1 M KF in the sub-nanometer-pores with the fast ion mobility of dehydrated fluoride ions49. The pores are, thus, larger than the fluoride ions (0.3 nm diameter) but smaller than the hydrated forms (0.7 nm diameter)39, suggesting the dehydration-mediated F− transport (Table 1)50. Additionally, a 0.28 V offset at zero current is observed, which is consistent with the suppressed transport of hydrated ions at low voltages due to the significant effects of Coulombic and steric interactions42. It is important to emphasize, however, that this pore size estimate is indirect and based solely on ionic current measurements. Additional factors, such as counterion conduction47, permselectivity51, electroosmotic flow52, and ion–ion correlations53, may also contribute to the observed conductance and have not been fully accounted for in this model. While the results are consistent with the formation of sub-nanometer pores, direct structural observation54 and refined theoretical modelings55 are essential to validate the inferred dimensions and to fully capture the ion transport physics within such confined environments.

The incorporation of KF also increased the ionic spiking rate. Pores form via dissolution-induced thinning of the metal phosphate layer and subsequently reclose through precipitation, driven by electric-field-mediated translocation of Mn²⁺ and phosphate ions. During this cycle, pores remain undetectable in ionic current measurements until they expand sufficiently to accommodate the relatively large Cl⁻ ions when F− is absent. Many pores, therefore, remain invisible, sealed by precipitation before becoming detectable. The introduction of smaller F⁻ anions enables ionic conduction through these nascent pores, revealing their existence and enhancing the observed spiking frequency.

The reaction dynamics are explored by inspecting the conductive pulse waveforms. Aligning the ionic signals with respect to the onsets and tails, defined as the moments when the ionic current rises above or returns to the base level, we obtain ensemble-averaged Iion profiles revealing how the ångström pores are formed and closed (Fig. 5f, g). They exhibit smooth changes in the ionic current, suggestive of the non-discrete nature of the reaction-driven pore opening/closure kinetics. Both the onset and tail phases can be fitted with the exponential function Iion∼exp(±rt), where the coefficient r characterizes the speed of the pore evolution (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). The observed decrease in r with increasing Vb suggests that higher electric fields slow down the dissolution and precipitation reactions (Fig. 5h), ascribed to the role of the associated stronger flows of non-reactant chloride ions in suppressing the reaction.

The autonomous spiking behavior of the nanopore membrane is highly tunable via chemical control. For example, reducing the MnCl2 concentration on the cis side from 2 M progressively suppresses spiking activity, yielding featureless ionic current traces (Supplementary Fig. 20). This inactivation arises from a concomitant pH increase from 4.2 to ∼7, which inhibits the dissolution of manganese phosphate nanoprecipitates once formed, mirroring the behavior observed in the AlCl3/PBS system. When the pH was adjusted back to 4.2, lowering the MnCl2 concentration to 0.1 M resulted in larger ionic spikes, indicative of pore opening driven by a reduced precipitation rate under limited Mn2+ supply (Supplementary Figs. 21–23). Further dilution of MnCl2 eventually caused rupture of the phosphate layer through dissolution, marking the transition from self-oscillatory to fully open states.

Reaction kinetics can also be modulated through the concentration of anionic reactants. Substituting PBS with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) eliminates the strong ionic rectification in the Iion–Vb curves, as HBSS lacks phosphate even in the presence of 2 M MnCl2 in cis. Meanwhile, introducing phosphate sources, H3PO4 (Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25), K2HPO4 (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27), or Na2HPO4 (Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29), into trans restores manganese phosphate nucleation within the nanopore, producing pronounced current suppression at negative Vb. The required concentration threshold depends strongly on the phosphate species: Na2HPO4 induces precipitation at levels as low as 10−5 M, whereas H3PO4 requires > 0.1 M due to its low pH (1.5), accelerating dissolution.

For Na2HPO4 in trans, ionic spiking emerges at concentrations above 5 × 10−3 M (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31). Below this threshold, insufficient phosphate flux fails to maintain a complete precipitate seal against the relatively fast cis-side dissolution. Conversely, at higher concentrations, the spiking frequency decreases and pulses become weaker and narrower (Supplementary Figs. 32–36), reflecting more rapid pore closure by an enhanced phosphate ion flux that prevents pores from growing to larger sizes.

Beyond reactant concentration, pH adjustment offers a way for reproducible, size-controlled pore formation. In MnCl2/PBS systems, lowering the trans-side pH below 7.4 with HCl steadily increases spike amplitudes (Fig. 6a–g, Supplementary Figs. 37–44). Simultaneously, the distribution of pulse heights narrows, indicating reduced pore-to-pore size variability (Fig. 6h). Using the Maxwell–Hall model under the condition Racc >> Rpore (Supplementary Fig. 14), the mean pore diameter is estimated to be tunable from ~2 nm to ~7 nm solely through pH control, demonstrating sub-nanometer precision in autonomous pore size regulation. Similar behavior was observed with pH adjustment on the cis side, although excessively acidic conditions led to membrane instability, limiting its utility for controlled operation (Supplementary Figs. 45 and 46).

a An illustrative description of a chemistry-driven autonomous membrane interfacing 2 M MnCl2 and acidic PBS with HCl. b Ionic current traces recorded for the MnCl2/(PCB + HCl) systems with a 100 nm nanopore in a 20 nm-thick SiNx membrane under Vb = −0.5 V. pH at trans is 6.7 (red) and 3.2 (blue). c–e Ip versus td scatter plots for the cases of pH 6.7 (c), 5.2 (d), and 3.2 (e). f Log10Ip distributions at pH 6.7 (red), 5.2 (green), and 3.2 (blue) at the trans. g Average Ip estimated by the Gaussian fits. Axis at the right denotes the pore diameter dpore estimated from the pulse heights based on Maxwell–Hall’s model. h Variations in the pulse heights are represented as the full-widths at half-maxima of the Gaussian peaks fitted in (f).

The automated membrane piercing for repeated nanopore formation is scalable to multipore systems. A single SiNx nanopore of dpore = 100 nm can serve as a template for precipitating metal phosphates under transmembrane voltage (Fig. 7a), enabling the chemically driven autonomous actuation to open and close minuscule pores. Expanding the number of 100-nm-sized pores Npore in two-dimensional arrays in the membrane results in a linear increase in the ionic conductance (Supplementary Fig. 47). Scanning Vb to examine the repetitive in-pore reactions with the MnCl2/PBS configuration, we observe strong ionic rectification at negative voltages (Supplementary Fig. 48). The absence of discrete features in the Iion-Vb curves, suggestive of sequential nanopore closure via phosphate precipitation, confirms the synchronized activity of the multiple SiNx pores in response to the transmembrane voltage. Consistently, the spiking frequency at −0.5 V increases linearly with Npore (Fig. 7b, c, see also Supplementary Fig. 49). Here, Fig. 7c is fitted with a linear function fcap = γ Npore with the slope γ. Notably, this level of control is unattainable by merely enlarging dpore in a single SiNx nanopore (Supplementary Figs. 50–52), manifesting the chemical kinetics distinction in the pores of different sizes.

a A sketch describing multipore in a SiNx membrane with cis and trans filled with 2 M MnCl2 and PBS, respectively. b Ionic current traces under Vb = −0.5 V for 100-nm-sized multipore membranes with the number of pores Npore = 1 (red), 4 (green), 16 (orange), and 36 (blue). False-colored scanning electron micrographs, with white bars denoting 1 μm, show the arrangement of nanopores. c fp plotted against Npore. Gray line is a linear fit crossing zero fp at Npore = 0. d Ip versus td scatter plots for the multipores of Npore = 1 (red) and 36 (blue). e Logarithmic Ip histograms for the multipores of Npore = 1 (red), 4 (green), and 36 (blue). Pink curves are a Gaussian fit to the peak profiles. Dashed line points at Ip of the ionic spikes detected with KF in trans at Vb = −0.5 V.

The high efficiency of Iion spiking allowed the observation of Cl− transport signature through the nanopores. Whereas the log10Ip distribution is featureless for 13,204 Iion spikes detected with a single 100-nm-sized nanopore, a pronounced peak appears ~1.8 nA, well described by the Gaussian function

with the peak position (xc), area (A), and width at half maximum (w), for 88,651 signals obtained with the quadrupore (Npore = 4) (Fig. 7d, e, see also Supplementary Fig. 53). The peak becomes even more pronounced with 163,241 signals from the hexadecapores (Npore = 16). This amount of current can be compared to the F− conductance giving 0.8 nA at Vb = −0.5 V. The higher conductance seen for Cl− is attributable to its 1.7-fold larger mobility than F-56. Only 0.009% and 0.02% of the pores are fully permeable to Cl− for Npore = 4 and 16, respectively, as evaluated by the area of the peaks at 1.8 nA, manifesting the importance of the high-fp systems for resolving dehydration-mediated ion transport. Overall results are consistent in validating the chemically-controllable break-membrane approach for systematic evaluations of the ion transport in ångström-scale small pores.

Discussion

Several mechanisms could, in principle, contribute to the ionic current spiking behavior. One possibility is that thin nanoprecipitate layers act as capacitors, intermittently charging and discharging under an applied voltage. Such processes, however, typically yield overshooting non-Faradaic current transients of biphasic characteristics57, in contrast to the single, non-overshooting pulses observed here. Another mechanism involves the so-called chemical reaction wave, a transient electrochemical phenomenon in which nucleation and dissolution reactions induce time-dependent morphological changes in a precipitated film on an electrode58. Yet in the present measurement configuration, this pathway is unlikely to generate appreciable Faradaic currents unless a new ion-conducting channel is created (though it may contribute to the autonomous activity of the nanoprecipitated membranes). Taken together, the most consistent interpretation is that the ionic current spikes originate from the spontaneous opening and closing of nanoscale pores in the precipitate layer, driven by the interplay of voltage-facilitated precipitation and dissolution reactions. Further efforts are expected to be devoted to exploring how the ångström pores behave under strong salinity gradients and localized electric fields. Under such conditions, additional factors, including counterion conduction47, concentration polarization59, permselectivity51, and electroosmotic flow52, alongside ion dehydration42, are expected to come into play. These effects may further enrich the nonlinear ion transport dynamics and broaden the functional space of voltage-gated chemically active nanopores.

The ability to actuate the repetitive opening and closing of nanopores via in-pore chemistry, with transmembrane voltage as a facilitator, manifests the pivotal role of solution composition in governing precipitation–dissolution dynamics of metal phosphates under nanoconfinement. Insufficient reactant concentration produces only a partial precipitate, unable to fully seal the SiNx nanopore. Conversely, excess reactants accelerate precipitation kinetics, closing the channel more effectively and yielding smaller pores upon reopening. The solution pH similarly regulates dissolution rates: acidic conditions tend to reopen larger pores, while basic conditions yield smaller ones. Meanwhile, it is important to note that since the reactant concentration can also shift the solution pH, these effects are mutually coupled, as observed in the MnCl2 concentration dependence of the Iion spiking feature. As such, both the frequency of pore piercing and the effective pore size can be tuned by manipulating the degrees of freedom available in solution chemistry.

Fabrication at atomic resolution remains beyond the reach of current semiconductor technologies. In nanoelectronics, however, the advent of mechanically controllable break junctions60,61 revolutionized the study of molecular devices by enabling the reproducible formation of single-molecule contacts through simple mechanical manipulation of metal tips. In an analogous manner, the chemically controllable break membranes demonstrated here provide a platform for systematic investigation of ion transport in sub-nanometer confinement. By repeatedly forming and measuring thousands of pores within a larger pore through self-regulated cycles of metal phosphate precipitation and dissolution under voltage control, this method addresses long-standing challenges in creating ångström-scale fluidic channels with reproducible precision. While the exact pore dimensions cannot yet be directly verified, the conductance data are consistent with transport through channels approaching the sub-nanometer scale. This capability opens opportunities to advance our understanding of fluid and ion dynamics in extreme confinement, with implications for emerging technologies such as single-molecule sensing62, neuromorphic computing63, and nanoreactors64.

Methods

Fabrication of solid-state nanopores

A 4-inch silicon wafer is coated with 30-nm-thick SiNx layers from both sides by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition. It is then diced into 25 mm × 25 mm square chips. Photoresist AZ5206-E (MicroChemicals co.) is spin-coated on a chip, followed by patterning of a microelectrode pattern by photolithography. After development, a 20 nm-thick Au with a 5 nm Ti adhesion layer is deposited by radio-frequency magnetron sputtering (Samco co.). The chip is immersed in N,N-dimethylformamide overnight and ultrasonicated to lift off the residual resist. Subsequently, the SiNx layer on the opposite side of the microelectrodes is partially removed by reactive ion etching (Samco co.) via a metal mask. After that, the exposed Si is wet-etched in KOH aq. (Wako co.) on a hot plate, creating a SiNx membrane at the bottom of the deep trench formed. On the membrane, ZEP520 resist is spin-coated. A circle of diameter dpore is delineated by electron beam lithography (Elionix co.). The residual resist after the development is used as a mask to sculpt a nanopore by the reactive ion etching. The chip is immersed in N,N-dimethylformamide overnight again to remove the resist layer. Finally, it is rinsed with ethanol and acetone.

Fabrication of nanoheater-embedded nanopores

A nanopore of dpore = 50 nm is formed in a SiNx membrane by the fabrication processes described above. Using a part of the microelectrodes as markers, a nanoscale coil pattern is delineated in the resist layer (ZEP520) coated on the membrane by the electron beam lithography. After development, 50 nm-thick Pt is deposited by sputtering. Lifting off the resist in N,N-dimethylformamide, the chip is rinsed with ethanol and acetone. Finally, 20-nm-thick SiO2 is grown on the membrane, which serves as a protection layer for the nanoheater. As the SiO2 is deposited on the nanopore wall, it causes the pore diameter to shrink to approximately 40 nm. We note that this nanoheater-embedded nanopore is used only for examining the in-pore chemistry at elevated temperature. All other measurements use the pristine nanopores in 30 nm-thick SiNx membranes.

Nanopore sealing

Polymer blocks are adhered to both sides of a nanopore chip for the ionic current measurements. They are made of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) formed on a SU-8 mold. Specifically, SU-8 resist is spin-coated on a 4-inch Si wafer. An I-shaped pattern is created by photolithography, which is used as a mold to cure PDMS. This is performed by pouring Sylgard 184 (Dow co.) on the mold, degassing in a vacuum, and heating in an oven at 90 °C for 6 hours. After curing PDMS, a 15 mm × 15 mm × 5 mm block is cut out with a surgical knife. Because of the SU-8 pattern, the block has an I-shaped trench serving as a fluidic channel for pouring electrolyte solution into nanopores. In the block, three holes are punched using a tool for biopsy. The surface of the PDMS block and the nanopore chip is activated by oxygen plasma (Femto co.). Subsequently, the two surfaces are put together for the bonding. The series of processes was carried out to attach another PDMS block to the other side of the nanopore.

Ionic current measurements

Electrolyte solution is poured into one of the three holes in a PDMS block attached to a nanopore chip using a pipette. Subsequently, another solution is added through the holes in the polymer block on the other side. After that, two Ag/AgCl rods are inserted into the holes in the two PDMS. Transmembrane voltage Vb is applied through one of the Ag/AgCl, and the resulting ionic current is recorded through the other Ag/AgCl. A picoammeter-source unit Keithley 6487 (Keithley co.) is used for the Iion–Vb characteristics measurements, which is GPIB-controlled under a program coded in Visual Basic. On the other hand, time course changes in the ionic current are recorded at 1 MHz sampling rate using a nanopore reader equipped with a fast current amplifier of 100 MHz bandwidth (Elements co.). After each measurement, HCl is added to the nanopore to completely dissolve the residual precipitates on the membrane surface for the condition initialization. After that, the PDMS channels are filled with ultrapure water (Millipore co.). The water is then replaced with an electrolyte solution for another ionic current measurement.

Ionic current spike extraction

The ionic current spikes fired upon the precipitate membrane piercing are extracted as follows. The open pore current is offset to zero by linear fits to the partial 0.5 s ionic current traces and subtracting the fitted components from the raw data. The offset traces are smoothed by the second-order Savitzky-Golay function for noise reduction, coded in Python. To extract the ionic current spikes, the local maxima points are searched above a threshold level of 300 pA. Subsequently, 2.5 ms of data before and after the current maxima are saved in a separate file, collecting the datasets of the ionic current spikes. For the ensemble averaging of the spike signals, the points where the current decreases to below zero amperes from the current maxima are identified, followed by data saving with the time at the zero-crossing point set to zero. The spikes extracted in this way are ensemble-averaged to examine the spike onsets and tails. All these pulse extraction processes are performed automatically under a program coded in Visual Basic.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gadsby, D. C. Ion channels versus ion pumps: the principal difference, in principle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 344–352 (2009).

Hille, B., Armstrong, C. M. & Mackinnon, R. Ion channels: from idea to reality. Nat. Med. 5, 1105–1109 (1999).

Choe, S. Potassium channel structures. Nat. Rev. Neuron 3, 115–121 (2002).

Jentsch, T. J., Hubner, C. A. & Fuhrmann, J. C. Ion channels: function unravelled by dysfunction. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1039–1047 (2004).

Maffeo, C., Bhattacharya, S., Yoo, J., Wells, D. & Aksimentiev, A. Modeling and simulation of ion channels. Chem. Rev. 112, 6250–6284 (2012).

Scott, A. J. et al. Constructing ion channels from water-soluble α-helical barrels. Nat. Chem. 13, 643–650 (2021).

Hodgkin, A. L. & Huxley, A. F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 117, 500–544 (1952).

Berneche, S. & Roux, B. Energetics of ion conduction through the K+ channel. Nature 414, 73–77 (2001).

Dixon, R. E., Mavedo, M. F., Binder, M. D. & Santana, L. F. Mechanisms and physiological implications of cooperative gating of clustered ion channels. Physiol. Rev. 102, 1159–1210 (2022).

Bocquet, L. Nanofluidics coming of age. Nat. Mater. 19, 254–256 (2020).

Emmerich, T. et al. Nanofluidics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 4, 69 (2024).

Ying, Y.-L. et al. Nanopore-based technologies beyond sequencing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 1136–1146 (2022).

Cao, L. et al. Switchable Na+ and K+ selectivity in an amino acid functionalized 2D covalent organic framework membrane. Nat. Commun. 13, 7894 (2022).

Surwade, S. P. et al. Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 459–464 (2015).

Zhang, Z., Wen, L. & Jiang, L. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 622–639 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Ion-beam sculpting at nanometre length scales. Nature 412, 166–169 (2001).

Storm, A. J., Chen, J. H., Ling, X. S., Zandergen, H. W. & Dekker, C. Fabrication of solid-state nanopores with single-nanometre precision. Nat. Mater. 2, 537–540 (2003).

Feng, J. et al. Single-layer MoS2 nanopores as nanopower generators. Nature 536, 536 (2016).

Rollings, R. C., Kuan, A. T. & Golovchenko, J. A. Ion selectivity of graphene nanopores. Nat. Commun. 7, 11408 (2016).

You, Y. et al. Angstrofluidics: waking to the limit. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 52, 189–218 (2022).

Robin, P. et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 379, 161–167 (2023).

Kavokine, N., Bocquet, M.-L. & Bocquet, L. Fluctuation-induced quantum friction in nanoscale water flows. Nature 602, 84–90 (2022).

Rigo, E. et al. Measurements of the size and correlations between ions using an electrolytic point contact. Nat. Commun. 10, 2382 (2019).

Huang, X.-Y., Cui, Y., Ying, C., Tian, J. & Liu, Z. Scaling behavior and conductance mechanisms of ion transport in atomically thin graphene nano/subnanopores. Nano Lett. 25, 1722–1728 (2025).

Powell, M. R. et al. Nanoprecipitation-assisted ion current oscillations. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 51–57 (2008).

Vilozny, B., Actis, P., Seger, R. A. & Pourmand, N. Dynamic control of nanoprecipitation in a nanopipette. ACS Nano 4, 3191–3197 (2011).

Yusko, E. C., Billeh, Y. N. & Mayer, M. Current oscillations generated by precipitate formation in the mixing zone between two solutions inside a nanopore. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 454127 (2010).

Maddar, F. M., Perry, D. & Unwin, P. R. Confined crystallization of organic materials in nanopipettes: Tracking the early stages of crystal growth and making seeds for unusual polymorphs. Cryst. Growth Des. 17, 6565–6571 (2017).

Tsutsui, M. et al. Transmembrane voltage-gated nanopores controlled by electrically-tunable in-pore chemistry. Nat. Commun. 16, 1089 (2025).

Wawrzkeiwicz-Jalowiecka, A., Krasowska, M., Strzelewicz, A., Cho, A. D. & Siwy, Z. S. Asymmetric nanopores sustain hours long stationary ion current instabilities with voltage controlled temporal patterns and predictability. Measurement 249, 116950 (2025).

Chow, C. C. & White, J. A. Spontaneous action potentials due to channel fluctuations. Biophys. J. 71, 3013–3021 (1996).

Alizadeh, A., Hsu, W.-L., Wang, M. & Daiguji, H. Electroosmotic flow: from microfluidics to nanofluidics. Electrophoresis 42, 834–868 (2020).

Zwolak, M., Lagerqvist, J. & Di Ventra, M. Quantized ionic conductance in nanopores. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 128102 (2009).

Sahu, S., Di Ventra, M. & Zwolak, M. Dehydration as a universal mechanism for ion selectivity in graphene and other atomically thin pores. Nano Lett. 17, 4719–4724 (2017).

Wei, W. Hofmeister effects shine in nanoscience. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302057 (2023).

Nuwan, Y. M., Bandara, D. Y. & Freedman, K. J. Lithium chloride effects field-induced protein unfolding and the transport energetics inside a nanopipette. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3171–3185 (2024).

Wei, W., Chen, X. & Wang, X. Nanopore sensing technique for studying the Hofmeister effect. Small 18, 2200921 (2022).

Assaf, K. I. & Nau, W. M. The chaotropic effect as an assembly motif in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13968–13981 (2018).

Kielland, J. Individual activity coefficients of ions in aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 59, 1675–1678 (1937).

Cabarcos, O. M., Weinheimer, C. J., Lisy, J. M. & Xantheas, S. S. Microscopic hydration of the fluoride anion. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 5–8 (1999).

Krems, M. & Di Ventra, M. Ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores. J. Phys. Cond. Matter 25, 065101 (2013).

Feng, J. et al. Observation of ionic Coulomb blockade in nanopores. Nat. Mater. 15, 850–855 (2016).

Mazzini, V. & Craig, V. S. J. What is the fundamental ion-specific series for anions and cations? Ion specificity in standard partial molar volumes of electrolytes and electrostriction in water and non-aqueous solvents. Chem. Sci. 8, 7052 (2017).

Hall, A. Access resistance of a small circular pore. J. Gen. Physiol. 66, 531–532 (1975).

Garaj, S. et al. Graphene as a subnanometre trans-electrode membrane. Nature 467, 190–193 (2010).

Sahu, S. & Zwolak, M. Maxwell-Hall access resistance in graphene nanopores. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 4646–4651 (2018).

Lee, C. et al. Large apparent electric size of solid-state nanopores due to spatially extended surface conduction. Nano Lett. 12, 4037–4044 (2012).

Qiu, Y. & Ma, L. Influences of electroosmotic flow on ionic current through nanopores: a comprehensive understanding. Phys. Fluid. 34, 112010 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Fast and selective fluoride ion conduction in sub-1-nanometer metal-organic framework channels. Nat. Commun. 10, 2490 (2019).

Richards, L. A., Schäfer, A. I., Richards, B. S. & Corry, B. The importance of dehydration in determining ion transport in narrow pores. Small 6, 1701–1709 (2012).

Zhang, S. et al. Addressing challenges in ion-selectivity characterization in nanopores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11036–11042 (2024).

Mehrafrooz, B. et al. Electro-osmotic flow generation via a sticky ion action. ACS Nano 18, 17521–17533 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Drastically reduced ion mobility in a nanopore due to enhanced pairing and collisions between dehydrated ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 4264–4272 (2019).

Kashin, A. S. & Ananikov, V. P. Monitoring chemical reactions in liquid media using electron microscopy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 624–637 (2019).

Liu, J. & Aksimentiev, A. Molecular determinants of current blockade produced by peptide transport through a nanopore. ACS Nanosci. Au 4, 21–29 (2024).

Koneshan, S., Rasaiah, J. C., Lynden-Bell, R. M. & Lee, S. H. Solvent structure, dynamics, and ion mobility in aqueous solutions at 25 °C. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 4193–4204 (1998).

Tivony, R., Safran, S., Pincus, P., Silbert, G. & Klein, J. Charging dynamics of an individual nanopore. Nat. Commun. 9, 4203 (2018).

Nagamine, Y. & Yoshikawa, K. Travelling wave on a phase-segregated metal composite caused by electrochemical reaction: direct monitoring for silver wave. AIP Adv. 15, 075040 (2025).

Yang, R. et al. Negative differential resistance in conical nanopore iontronic memristors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13183–13190 (2024).

Xu, B. & Tao, N. J. Measurement of single-molecule resistance by repeated formation of molecular junctions. Science 301, 1221–1223 (2003).

Evers, F., Korytar, R., Tewari, S. & van Ruitenbeek, J. M. Advances and challenges in single-molecule electron transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 035001 (2020).

Drndic, M. 20 years of solid-state nanopores. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 606 (2021).

Xu, G. et al. Nanofluidic ionic memristors. ACS Nano 18, 19423–19442 (2024).

Wang, Y., Xie, F. & Zhao, L. Spatially confined nanoreactors designed for biological applications. Small 20, 2310331 (2024).

Acknowledgements

A part of this work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grant numbers 23K22681, 24K08201, and 25K01639. Makusu Tsutsui acknowledges support by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) Grant no. 25152420.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T., D.G., H.D., and T.K. conceived and designed experiments. M.T., W.L.H., D.G., and A.D. performed experimental studies. M.T., W.L.H., Y.K., D.G., and A.D. analyzed data. M.T. and T.K. co-wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Huacheng Zhang, Kai Xiao, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsutsui, M., Hsu, WL., Garoli, D. et al. Chemistry-driven autonomous nanopore membranes. Nat Commun 17, 1496 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68800-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68800-x