Abstract

The gut microbiome is increasingly implicated in colorectal cancer (CRC), yet the functional signatures associated with disease progression remain poorly resolved across populations. We performed an assembly-based metagenomic analysis of more than 500 samples from three geographically distinct cohorts to characterize resistome and virulome patterns associated with CRC. Using a cross-validated modeling framework based on Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, we identified two reproducible latent functional gradients that structured variation in antimicrobial-resistance and virulence-factor profiles. One gradient was enriched for adhesion, efflux, and biofilm-associated functions, while the second reflected immunomodulatory and barrier-related pathways. These components were statistically robust, directionally stable across cohorts, and consistent with functional themes frequently reported in CRC microbiome studies. To summarize variation along these gradients, we derived an exploratory Dual-Axis Index (DAI) based on the two stable PLS components. Although its discriminative performance was moderate, the DAI provided an interpretable low-dimensional representation of how resistome–virulome patterns differed across healthy, adenoma, and carcinoma states. These results suggest that functional gene profiles in CRC are organized along reproducible statistical axes, and highlight functional modules, such as adhesion-, iron-associated, and immune-interaction pathways that may complement taxonomic or metabolic biomarkers in future multimodal approaches. Our work provides a reproducible, assembly-based framework for examining the functional organization of CRC-associated microbiomes across diverse populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a defining challenge of modern oncology, ranking among the top three most diagnosed malignancies and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide1,2. Nearly two million new cases occur each year, and while screening has stabilized incidence in high-income regions, rates are accelerating across low- and middle-income countries3,4,5. In Africa alone, CRC prevalence is expected to more than double by 2040, reflecting shifts in diet, urbanization, and population aging6,7,8. These global trends demand new frameworks that integrate environmental, microbial, and molecular determinants of disease.

Among these determinants, the gut microbiome has emerged as a dynamic ecological system associated with CRC risk. The intestinal microbiota maintains metabolic homeostasis, epithelial integrity, and immune balance, yet disruption of this equilibrium termed “microbial dysbiosis” has been linked to inflammation, genotoxicity and tumor progression environment9,10,11,12,13,14. Multiple bacterial species, including Fusobacterium nucleatum, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, colibactin-producing Escherichia coli, Parvimonas micra, and Hungatella hathewayi, exemplify how microbial colonization, toxin secretion, and immune modulation may influence CRC-associated pathology15,16,17,18. Consistently, CRC-associated microbiomes display enrichment of oral-derived pathobionts and depleted butyrate-producing commensals such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia, reflecting broader ecological reorganization19,20,21,22.

Importantly, microbial function, not only composition, appears deeply relevant to CRC biology. Virulence factors (VFs) and antimicrobial-resistance genes (ARGs) provide insight into how microbes can persist within, or adapt to, the tumor microenvironment. VFs contribute to adhesion and barrier disruption, while an expanded resistome may support survival under oxidative stress, inflammation, or chemotherapeutic pressure23,24,25,26,27. These functional attributes suggest that CRC-associated microbiota occupy a selective niche shaped not merely by taxonomic shifts but also by metabolic and defensive capacity28.

Despite this evidence, most CRC-microbiome studies remain taxonomic, reference-dependent, and cross-sectional, limiting reproducibility and hindering functional interpretation. Assembly-based, multi-cohort frameworks that integrate functional inference with ecological modeling remain scarce.

Here, we present a multi-cohort, assembly-based metagenomic analysis of more than 500 samples spanning healthy, adenoma, and carcinoma states. Our pilot investigation focuses on the functional ecology of the CRC microbiome by combining de novo assembly with Double Machine Learning (DML) to identify latent statistical components in the resistome–virulome space. Rather than proposing predefined ecological categories, we examine whether reproducible functional gradients emerge across geographically distinct cohorts and explore how these gradients relate to CRC status. Our goal is to provide an initial statistical and ecological framework for understanding how functional gene patterns, particularly virulence- and stress-associated pathways vary across CRC progression.

Results

Data processing and quality assessment

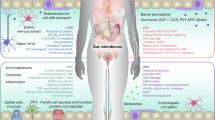

Rigorous preprocessing eliminated host and contaminant sequences, yielding high-quality assemblies across all cohorts (Figure S1a-i, Data S1). Cohort 3 produced the most contiguous assemblies, whereas Cohort 1 exhibited greater fragmentation, consistent with variation in sequencing depth (Figure S1a-ii, Data S1). Batch correction effectively minimized inter-cohort bias while preserving biological structure. For instance, species-level variation among clinical groups remained significant (PERMANOVA R² = 0.018, p = 0.001), whereas functional (ARG/VF) profiles showed no residual batch structure (Figure S1b-i, S2a; Data S2). These quality-control steps ensured that downstream ecological and functional analyses reflected biological rather than technical variation. The overview of the study design and analytical workflow is shown in Fig. 1.

Publicly available CRC metagenomic datasets from three international cohorts were processed through a harmonized pipeline. Following host read removal, decontamination, and de novo assembly, functional profiling was performed to extract antimicrobial resistance (ARG) and virulence factor (VF) gene matrices, followed by normalization and batch correction. Machine-learning classification was used to identify discriminative taxa and ecological signatures across disease stages, while Partial Least Squares–Double Machine Learning (PLS-DML) analysis was applied to the ARG/VF dataset to model directional associations with CRC progression. Validation included bootstrap resampling, external cohort testing, and ecological interpretation through the Dual-Axis Index (DAI), which distinguished two major microbial strategies: pathogenic expansion (red) and protective adaptation (blue).

Microbial community ecology across CRC stages

Microbial diversity remained largely stable across disease stages, with no significant differences in alpha diversity (Richness p = 0.51; Shannon p = 0.11; Simpson p = 0.13) (Fig. 2a; Data S2). However, beta-diversity analyses revealed subtle but consistent restructuring of community composition (R² = 0.018, p = 0.001) across healthy, adenoma, and cancer groups (Fig. 2b). These differences reflected genuine ecological reorganization rather than dispersion effects (ANOVA F = 0.96, p = 0.39) (Data S2).

a Alpha-diversity metrics across clinical stages showing comparable within-sample diversity (i, Richness; ii, Shannon; iii, Simpson). b Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS, Euclidean distance) reveals modest but significant compositional restructuring among Healthy, Adenoma and Cancer groups. c Reproducibility of CRC-associated taxa: i, core species enriched across cohorts; ii, Venn comparison of taxa shared with reference CRC datasets16,29; iii, clustered heatmap showing consistent stage-associated abundance profiles (Z-score). d Co-occurrence networks of reproducible taxa highlighting core commensals (R. intestinalis, A. hallii, B. wexlerae) as major ecological hubs forming stable, functionally cohesive modules across CRC progression.

Core species were highly conserved across cohorts ( > 99% overlap) and dominated by commensals such as Anaerobutyricum hallii, Roseburia intestinalis, and Blautia wexlerae, suggesting metabolic resilience despite disease progression (Fig. 2c-i; Data S2). Peripheral taxa accounted for the majority of diversity (approximately 85%), highlighting adaptive turnover along the CRC continuum. Comparison with previously published CRC datasets16,29 confirmed the reproducibility of our results, identifying 64 overlapping taxa (20.9%) shared with reference studies. These included Parvimonas micra, Hungatella hathewayi, and Bacteroides fragilis, which were consistently enriched in cancer, as well as A. hallii, B. wexlerae, and Eggerthella lenta, which were more abundant in controls (Fig. 2c-ii, iii; Data S2). Importantly, these overlapping species correspond to canonical CRC markers reported in the GMrepo v2 database30, further validating the cross-cohort reproducibility of our findings. Network analysis additionally identified R. intestinalis as a central hub associated with stage-specific microbial modules (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these findings reveal a stable commensal core accompanied by a dynamic peripheral microbiome undergoing progressive ecological restructuring across CRC progression.

Stage-specific microbial indicators and predictive features

Indicator-species analysis identified 42 taxa significantly associated with clinical stages (adj. p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Health-associated microbiomes were enriched in Ligilactobacillus ruminis, Faecalibacillus intestinalis, and Clostridium thermarum, whereas Bacteroides sp. CACC 737 and B. cellulosilyticus increased in adenoma and cancer. Novosphingobium sp. 9 and Bifidobacterium longum were distinguishing indicators between cancer and healthy samples (Data S3).

a Indicator-species analysis (IndVal.g) identifies taxa significantly associated with Healthy, Adenoma and Cancer stages (Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted p ≤ 0.05). b Performance of supervised classifiers discriminating CRC stages from species-level abundance profiles. Models (Random Forest i, and Gradient Boosting ii) were trained as multi-class classifiers. ROC curves were generated using the standard one-vs-rest (OvR) extension of ROC analysis, where a separate ROC curve is computed for each class based on its predicted probability scores. iii Consensus feature ranking across models highlights robust discriminative taxa, including A. hallii, Blautia hansenii, Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, and R. intestinalis.

Supervised learning further supported these stage-specific patterns. Among all models, Gradient Boosting showed the highest overall performance (mean accuracy = 0.69; balanced accuracy = 0.61; MCC = 0.48) and consistently strong discrimination across clinical groups (AUC = 0.71 for cancer, 0.58 for adenoma, and 0.73 for healthy; Fig. 3b-i, ii; Figure S1c-i). Random Forest also performed relatively well (mean accuracy = 0.66; MCC = 0.43), but with slightly lower discrimination compared to Gradient Boosting. Consensus feature ranking of the two models identified Prevotella copri, Sellimonas intestinalis, Butyrivibrio crossotus, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii among the most predictive taxa, together with several other species overlapping with already established CRC markers (Fig. 3b-iii; Data S3). These findings indicate a reproducible microbial signature that discriminates disease stages and captures coherent ecological shifts along the CRC trajectory.

Functional variation across host and geographic contexts

To focus on biologically interpretable functional variation, we quantified the total abundance (“load”) of antimicrobial-resistance (ARG) and virulence-factor (VF) genes per sample rather than re-estimating diversity indices. Total ARG and VF loads did not differ significantly among disease stages (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4a, b; Data S3), indicating that CRC progression alone does not substantially alter the overall functional capacity of the microbiome. Instead, ARG and VF variation showed stronger associations with host and geographic factors: body-mass index (BMI) correlated negatively with both ARG (ρ = −0.26, p < 0.05) and VF (ρ = −0.21, p < 0.05) loads, and ARG abundance varied across countries (p = 0.001), with higher values in Austria than in France (p = 0.006) or Germany (p = 0.017). No associations were observed with age or sex (Data S3), suggesting that resistome and virulome magnitude covaries primarily with host physiology and environmental context rather than tumor stage.

a, b Total antimicrobial-resistance gene (ARG) and virulence-factor (VF) loads across Healthy, Adenoma and Cancer groups show no global differences in abundance. c Bootstrapped PLS-Double-Machine-Learning (PLS-DML) effects showing component-level average treatment effects (ATEs). d Sensitivity of estimated effects to unmeasured confounding quantified by E-values; PLS₃ shows greatest robustness. e Directed acyclic graph (DAG) illustrating assumptions linking ARG/VF abundance (indicated in the figure as Microbial_abundance) to CRC stage while adjusting for age, BMI and sex. f Gene co-occurrence network highlighting interactions between dominant ARG and VF modules along the CRC continuum. Red node = PLS₁ and green node = PLS₃. g External-validation ROC curve showing moderate discrimination of the derived functional signatures (AUC = 0.603). h Directional concordance of PLS₁/PLS₃ genes between internal and external datasets indicating consistent trends. i Power analysis for PLS₁ and PLS₃ components demonstrating statistical power > 80% at current sample size. j Gene-level ANOVA-based power estimates confirming adequate detectability for the most robust genes under about 100 samples per group.

Directional modeling of functional axes

To explore potential functional patterns associated with CRC progression, we applied a cross-validated Partial Least Squares-Double Machine Learning (PLS-DML) framework controlling for age, BMI, and sex. Ten (10) components were derived, of which two captured dominant functional axes: PLS₁, enriched for virulence and resistance functions, and PLS₃, reflecting protective, functionally adaptive traits (Fig. 4c–e; Data S3).

PLS₁ showed a modest positive average treatment effect (ATE = 0.004; 95% CI = –0.023 to 0.030), whereas PLS₃ displayed a negative association with CRC risk (ATE = –0.038; 95% CI = –0.092 to 0.015) and the highest robustness to unmeasured confounding (E-value = 1.24). Gene-loading analysis identified virulence genes (eptA, irp1, entE) within PLS₁ and protective elements (Cdif_EFTu_ELF and Ecol_EFTu_KIR, EC-5) within PLS₃ (Figure S2e, f). Functional enrichment showed that PLS₁ was dominated by exotoxin, adherence, biofilm-formation, and RND efflux mechanisms, while PLS₃ featured effector-delivery, immune-modulation, and target-alteration pathways (Data S3). Post-hoc tests confirmed that virulence-linked functions such as biofilm formation, adherence, and efflux pumps were significantly elevated in cancer compared with the other groups (p < 0.05).

Network topology further distinguished the two axes: PLS₁ hubs (stgC, Kpne_phoQ_CST, ygeH, fliA) formed cooperative resistance-virulence clusters, whereas PLS₃ hubs (upaH, tet(37), TolC, bacA) organized into cohesive protective networks (Fig. 4f, Data S3). As an exploratory proof-of-concept, we assessed whether the two stable functional axes identified by PLS-DML (PLS₁ and PLS₃) were sufficient to capture disease-associated functional variation. A minimal logistic model using only these two components achieved an out-of-fold ROC-AUC of 0.68 (95% CI 0.58–0.78) for distinguishing cancer from non-cancer samples. Risk stratification based on out-of-fold predicted probabilities reflected clinical stage patterns where high-risk assignments were most common in cancer (35.7%), followed by healthy (29.6%) and adenoma (12.5%), whereas low-risk classifications were rare in cancer (7.1%) but more frequent in non-cancer groups (18.5% in healthy; 20.8% in adenoma) (Data S4). These results indicate that the Dual-Axis Index (DAI) summarizes broad functional tendencies associated with CRC status, while its moderate discriminative performance underscores that it should be interpreted as an associative ecological score rather than a diagnostic classifier.

Validation and reproducibility of PLS-DML gene signatures

To assess reproducibility, the stable PLS₁ and PLS₃ gene signatures were first evaluated within the internal dataset and then validated in an independent CRC cohort (Data S4). Logistic regression, identified during benchmarking as the top-performing classifier, achieved strong internal discrimination (AUC = 0.776, MCC = 0.54). Before applying the model externally, we performed a leave-one-cohort-out (LOCO) analysis to examine cross-cohort robustness. Performance differed between the held-out cohorts, with Cohort 2 showing moderate discrimination (AUC = 0.71) and Cohort 3 showing lower discrimination (AUC = 0.46). However, Cohort 1 could not be assessed because only a single sample remained after quality filtering and alignment. Further, when the model was applied to the external validation cohort, it retained moderate discrimination (AUC = 0.603; balanced accuracy = 0.54; F₁ = 0.51; MCC = 0.10) (Fig. 4g; Figure S2g). Subsequently, gene-level concordance showed that 17 of 34 genes, including stgC, irp1, tet(37), upaH, Kpne_phoQ_CST, phoQ, and espX5, preserved consistent directionality across cohorts (Fig. 4h). Although effect magnitudes differed (Mann-Whitney p = 0.002; Wilcoxon p = 0.003), overall trends were conserved, supporting the biological stability of PLS components (Figure S2h-i).

Power analysis indicated robust statistical reliability for PLS₁ (power = 86.2%; Cohen’s f = 0.33) and near-sufficient power for PLS₃ (78.9%; f = 0.30) at the current sample size (N = 107). These results confirm that the PLS-DML gene signatures capture generalizable microbial determinants of CRC risk across populations (Fig. 4i, j; Figure S2d; Data S4).

Overall, these analyses delineates a reproducible ecological and functional continuum of CRC progression anchored by a stable commensal core and dynamically shifting peripheral taxa. The directional modeling framework identifies two consistent microbial strategies that may be linked to the functional reorganization of the gut microbiome during colorectal tumorigenesis. We emphasize that PLS₁ and PLS₃ represent latent statistical components extracted from the resistome–virulome matrix using five-fold cross-validated PLS regression. Their ecological interpretation is therefore post hoc, inferred from the structure of the gene loadings rather than imposed a priori. PLS₁ and PLS₃ capture the dominant axes of covariation in antimicrobial-resistance and virulence-factor profiles after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, and their loading patterns remained stable when functional categories were permuted, supporting that these components reflect genuine covariation structure rather than annotation artifacts.

For clarity, the descriptors “pathogenic enrichment” and “protective adaptation” are used only as interpretive summaries of the enriched functional signatures. For instance, adhesion, efflux, and biofilm-associated genes in PLS₁, while immunomodulatory or barrier-associated elements in PLS₃. These labels are not intended to denote discrete ecological strategies. Instead, PLS₁ and PLS₃ should be understood as reproducible statistical gradients that align with well-reported CRC-associated microbial adaptations without implying mechanistic causality.

Discussion

This study provides a multi-population characterization of the CRC resistome and virulome using an assembly-based metagenomic framework. By reconstructing contigs through de novo assembly rather than relying solely on read-level profiling, our approach captured a broader spectrum of microbial functional diversity and improved the resolution of gene-level analyses, enabling consistent cross-cohort comparison of microbial traits. Integrating these assembly-derived features with batch-aware normalization produced reproducible ecological and functional patterns despite demographic and geographic variability. These findings demonstrate that harmonized assembly workflows can bridge technical gaps that have long limited cross-study comparability in CRC microbiome research.

Across populations, the CRC microbiome showed gradual ecological restructuring rather than abrupt community turnover. Core commensals such as A. hallii, R. intestinalis, and B. wexlerae remained conserved across disease stages, while opportunistic taxa including P. micra, H. hathewayi, and B. fragilis expanded progressively along the adenoma–carcinoma sequence. These species, consistently identified in global meta-analyses16,22,29, highlight the universality of CRC-associated microbial shifts across populations and sequencing platforms. Our harmonized cross-cohort framework reproduced these patterns in three independent datasets, confirming that CRC-related microbial transitions are ecologically stable and globally reproducible. The enrichment of oral-derived pathobionts particularly P. micra, F. nucleatum, and H. hathewayi together with the depletion of butyrate-producing commensals appears to be consistent with a continuous microbial gradient from health to malignancy accompanied by the gradual colonization of oral anaerobes.

Together, these compositional shifts imply not only taxonomic restructuring but also deeper functional adaptation of the CRC microbiome. Accordingly, we investigated the resistome and virulome to determine how antimicrobial resistance and virulence traits contribute to microbial persistence in the tumor-associated niche. Fredriksen et al. (2023) reported mild but consistent ARG enrichment in CRC despite limited antibiotic exposure, attributing it to inflammation-driven selection31. Our results align with this interpretation, as CRC-associated communities exhibited elevated efflux and biofilm potential, traits consistent with persistence under oxidative and inflammatory stress. This suggests that resistome expansion in CRC reflects adaptation to the tumor niche rather than direct antibiotic pressure.

Functionally, our analysis reveals two opposing microbial strategies that organize CRC-associated communities. Using a cross-validated PLS-DML framework, we identified a pathogenic enrichment axis (PLS₁) characterized by virulence and resistance mechanisms, and a protective adaptation axis (PLS₃) defined by immunomodulatory and barrier-stabilizing functions. These axes represent a directional ecological gradient rather than binary dysbiosis. Mechanistically, genes such as eptA and phoQ remodel bacterial surfaces to resist antimicrobial peptides and oxidative stress32,33,34, while irp1 and entE mediate siderophore-driven iron acquisition, thereby promoting microbial survival under tumor-associated hypoxia35,36,37,38. Conversely, upaH and bacA, which are central to the protective axis were reported to enhance mucosal adhesion and membrane integrity, which could lead to maintaining commensal stability in inflammatory environments39,40,41. The coordinated behavior of these antagonistic gene networks for example, stgC-phoQ-ygeH versus upaH-bacA-TolC captures the dual ecological logic of the CRC microbiome, in which virulent expansion coexists with compensatory symbiotic resilience, reflecting an adaptive equilibrium associated with selective pressures within the tumor microenvironment. Detailed annotations, mechanisms, and species associations for all PLS₁- and PLS₃-associated genes, based on CARD and VFDB classifications, are provided in Supplementary Data S1 and S2. Because PLS-DML derives components that maximize covariance between microbial functions and disease stage, the resulting axes reflect statistical structures, not predefined ecological categories. Accordingly, their interpretation as “pathogenic enrichment” and “protective adaptation” is intended to be conceptual rather than categorical. These descriptors merely summarize the dominant functional themes associated with each axis, for example, adhesion, efflux, and biofilm pathways loading positively on PLS₁, and immunomodulatory or stress-adaptive elements loading on PLS₃.

We do not claim that these components correspond to discrete in vivo ecological strategies. Rather, they represent cohort-independent functional gradients that are consistent with patterns frequently observed across CRC microbiome studies. This distinction is important as the PLS axes provide an interpretable statistical framework for organizing resistome–virulome variation, but they should not be interpreted as mechanistic or causative ecological modes.

Overall, nearly half of the 34 overlapping genes driving these two axes retained consistent directionality across cohorts, supporting their biological stability. Power analysis confirmed adequate statistical strength for both axes, reinforcing that the identified components represent reproducible functional gradients rather than stochastic variation. The robustness of these functional axes across cohorts provides a foundation for comparison with earlier CRC microbiome studies.

In contrast to the stability of gene-level patterns, predictive transferability showed greater variability. The moderate decrease in performance observed during external validation (AUC = 0.603), compared with higher internal discrimination (AUC = 0.776), reflects a well-recognized challenge in microbiome-based prediction: models trained in one population frequently exhibit attenuated performance when applied to independent cohorts. Our leave-one-cohort-out (LOCO) analysis demonstrated the same pattern, with substantial variability among internal cohorts (AUC range: 0.46–0.71), despite the absence of residual batch effects in the functional space. This heterogeneity is consistent with prior multi-cohort CRC studies, which show that differences in sequencing depth, assembly contiguity42, population-specific strain composition43, and environmental exposures (diet, geography, and antibiotic history)16 can markedly influence functional gene recovery and therefore limit cross-cohort generalizability. Given that ARGs and VFs are highly sensitive to such local ecological and technical factors, moderate variability in absolute predictive performance is expected. Importantly, the directional consistency of the top-loading genes across cohorts supports the stability of the underlying PLS components, whereas the observed AUC differences underscore the inherent difficulty of achieving universal transportability in metagenomic classifiers18.

Building on this observed gene-level stability, the virulence-associated patterns identified here are broadly consistent with prior CRC microbiome studies. For example, Yang et al. (2021) reported early enrichment of adhesion- and virulence-related functions in young-onset CRC, while Wirbel et al. (2019) described a global virulence signature dominated by oral pathobionts such as Fusobacterium and Parvimonas16,44. The recurrence of these functional themes across geography, age groups, and analytical frameworks suggests that virulence-associated modules represent a reproducible aspect of CRC-associated microbiomes rather than cohort-specific artifacts. This cross-study consistency complements the directional stability of our PLS-derived components, reinforcing the interpretation that certain functional motifs appear robustly across CRC datasets even when taxonomic compositions vary.

Within this context, the Dual-Axis Index (DAI) serves as a concise, exploratory summary of the two dominant functional gradients captured by PLS₁ and PLS₃. While its discriminative performance is moderate (AUC = 0.68), the DAI provides interpretive value by positioning samples along these functional axes rather than classifying them into discrete diagnostic categories. Higher scores occurred more frequently among cancer samples, whereas lower scores were more common among non-cancer groups. However, the substantial overlap, particularly between healthy and adenoma samples, indicates that functional gene profiles alone cannot reliably resolve early disease states. Accordingly, we do not present the DAI as a diagnostic or prognostic tool. Instead, it offers a structured statistical framework for summarizing resistome–virulome variation and may complement taxonomic, metabolic, inflammatory, or clinical markers in future multimodal approaches18,19,20,22,25. In this respect, the consistently enriched modules identified here, for example, adhesion, iron-associated functions, and immune-interaction pathways could serve as adjunct functional features to established stool-based assays, including fecal immunochemical tests or F. nucleatum detection45,46,47. Ultimately, any translational application would likely require integration of multiple data layers and validation in prospective designs with the DAI providing a conceptual starting point for such integrated frameworks.

A major strength of this study lies in its integrative analytical design, combining assembly-based contig reconstruction, functional profiling, and Double Machine Learning (DML) modeling to identify stable microbial features across populations. The contig-level quantification strategy enabled consistent cross-cohort comparison by preserving low-abundance but informative ARG and VF annotations. To ensure analytical reproducibility, each functional gene was counted once per contig and normalized to the total number of ARG/VF annotations within each sample, thereby minimizing biases from sequencing depth, assembly fragmentation, and multi-hit inflation42,48. Retaining the complete functional repertoire avoided over-weighting abundant features and allowed us to capture the full breadth of resistome and virulome variation. Importantly, the cross-fitted PLS-DML components were driven by consistently detected functional modules, such as adhesion, efflux, and siderophore-associated pathways rather than by rare features more sensitive to sequencing variation49,50,51. The absence of residual batch effects in the functional space (PERMANOVA R² < 0.01), together with directional concordance for approximately half of the high-loading genes in the independent validation cohort, underscores the stability of these functional gradients across populations. Future incorporation of long-read sequencing or prevalence-based filtering may further enhance resolution where needed.

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the cross-sectional study design precludes causal inference, and residual confounding by unmeasured factors (such as diet, medication, sampling protocol, or inflammatory comorbidities) cannot be excluded. Second, the absence of genome-resolved binning limits strain-level interpretation of resistance and virulence determinants. Future work integrating long-read sequencing, genome dereplication, and metabolically coupled multi-omic data could refine functional resolution and facilitate investigation of horizontal gene transfer and the evolution of resistance or virulence traits within the CRC microenvironment. Applying this framework to larger, prospectively sampled cohorts and combining functional, taxonomic, metabolic, and immunologic layers will help clarify how resistome–virulome patterns relate to diagnostic potential, host physiology, and broader CRC functional ecology.

In summary, our findings delineate reproducible functional gradients associated with CRC progression, illustrating how microbial communities vary along axes of virulence-associated enrichment and commensal-like functional adaptation. This function-centered perspective provides an interpretable statistical framework for organizing resistome–virulome variation and offers a conceptual bridge between microbiome ecology and emerging translational applications.

Methods

Analytical framework

All analyses were conducted using the GRUMB pipeline, which integrates read processing, assembly, taxonomic profiling, and machine-learning modules within a reproducible workflow52,53. For this study, GRUMB was adapted for CRC microbiomes and extended with a Partial Least Squares (PLS)-Double Machine Learning (DML) framework to model directional associations between microbial functions (ARGs and VFs) and disease stage. The analytical workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1 as shown above.

Metagenomic cohorts and quality processing

Publicly available shotgun metagenomic datasets (553 samples) were retrieved from the NCBI SRA on 10 November 2024, encompassing three geographically distinct cohorts: Cohort 1 (USA/Canada, n = 84)54, Cohort 2 (France/Germany, n = 316)18, and Cohort 3 (Austria, n = 153)19. These cohorts were selected for their high-quality sequencing data, harmonizable metadata (age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and disease stage: Healthy, Adenoma, Cancer), uniform Illumina sequencing platforms, and consistent read lengths (100–125 bp). As these datasets have been widely used in benchmarking studies, they enable direct comparison with previous CRC microbiome research while minimizing technical heterogeneity that could confound functional inference. Focusing on these well-curated cohorts ensures that observed patterns reflect biological rather than batch-driven variability and provides a robust, reproducible basis for future multi-cohort extensions.

The raw reads obtained from these datasets were then quality-filtered and trimmed using BBTools v37.6255, while host or contaminant sequences were removed with FastQ Screen v0.15.356 against a multi-genome reference. Clean reads were assembled de novo using metaSPAdes v3.15.5 57with default parameters, and contigs shorter than 1 kb were discarded. Assembly quality was assessed using QUAST v5.2.058, and outputs were formatted for downstream analyses.

Taxonomic profiling and ecological analysis

Contigs were taxonomically classified using Kraken2 (v2.1.3)59 and abundance estimates refined with Bracken v2.960 against the standard Kraken2 bacterial database (https://benlangmead.github.io/aws-indexes/k2). Species detected in < 5% of samples or non-microbial taxa were excluded.

Relative-abundance matrices were centered-log-ratio (CLR) transformed after pseudocount regularization61,62 and batch-corrected with empirical-Bayes linear modeling in limma::removeBatchEffect v3.64.163,64, using Project and Center Name as technical covariates. Clinical stage (Healthy, Adenoma, Cancer) was not included as a batch variable to avoid artificial inflation of disease-associated signals. Correction quality was verified by t-SNE visualization and PERMANOVA variance partitioning.

Alpha-diversity (Shannon, Simpson, Richness) and beta-diversity (Euclidean distance, NMDS) were computed in vegan v2.6-1064. Group differences were assessed with Kruskal–Wallis and PERMANOVA, and dispersion with betadisper. Indicator species were identified by IndVal.g (999 permutations; indicspecies v1.8.0) and classified as core ( ≥ 80%), secondary (50–79%), or peripheral ( < 50%). Ecological networks and prevalence intersections were visualized with igraph, ggraph, and UpSetR.

Validation of Reported CRC Markers

Previously reported CRC-associated taxa were compiled from Wirbel et al. (2019) and Piccinno et al. (2025)16,29 to assess cross-study reproducibility. In addition, we consulted the GMrepo v2 database30 to further verify the presence of established CRC biomarkers and confirm that the species detected in our assemblies corresponded to those consistently reported across independent human gut microbiome cohorts. Overlap between the current study’s taxa and reference markers was visualized using a Venn diagram and hierarchical clustering (ComplexHeatmap v2.24.0). Spearman correlation networks (r > 0.5) and Louvain clustering were used to detect conserved co-occurrence modules across clinical stages.

Functional annotation and load analysis

Contigs were aligned to the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)65 and Virulence Factor Database (VFDB)66 using DIAMOND blastx (v2.1.10)67 (e-value < 1 × 10⁻⁵, identity ≥ 80%). To generate reproducible functional profiles across cohorts, each contig-level ARG or VF annotation was counted once and converted into a within-sample relative frequency by scaling to the total number of detected functional annotations. These normalized values were assembled into gene-by-sample matrices with standardized identifiers (ARG_ or VF_) and merged only after strict alignment of sample IDs to their corresponding metadata. Subsequently, group differences were evaluated by Kruskal-Wallis with Benjamini-Hochberg correction, and associations with host factors (age, BMI, sex, country) were assessed by Spearman correlation.

Machine-learning classification

Species-level classification used scikit-learn68 implementations of Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Decision Tree (DT), and Logistic Regression (LR). Data were split 80 : 20 (training : test) with stratified sampling and evaluated by 10-fold cross-validation. Performance metrics included accuracy, balanced accuracy, macro F₁, Cohen’s κ and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). The best-performing classifiers (RF and GB) were further evaluated using nested cross-validation with grid-search optimization. Feature importance was computed using both Gini and permutation-based methods, averaged over 50 iterations to produce consensus predictor rankings.

To prevent information leakage, all hyperparameter tuning was performed exclusively within the inner loop of the nested cross-validation framework. The outer loop (10-fold) provided an unbiased estimate of model performance, while the inner loop (5-fold) optimized hyperparameters using GridSearchCV. The complete hyperparameter search space for all taxonomic and functional models is provided in Data S3.

Directional functional modeling with PLS–DML

To explore directional relationships between microbial functions and CRC progression, Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression was combined with Double Machine Learning (DML)69,70,71. The ARG and VF datasets were first benchmarked using the same machine-learning framework described above to identify suitable nuisance estimators. RF and GB provided the most stable fits and were therefore adopted in the PLS-DML workflow. Hyperparameter tuning for these models also followed the same nested framework, with optimization restricted to inner folds to preserve the integrity of out-of-fold estimates. A directed acyclic graph (DAG) was constructed in daggity v0.3-4 in order to identify the minimal adjustment set of covariates (age, sex, BMI)72,73. Prior to analysis, five-fold cross-validated PLS regression was applied to the data to extract latent functional components summarizing ARG/VF-CRC covariation.

Average treatment effects (ATEs) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using a cross-fitted Double Machine Learning (DML) framework (econml v0.14.2) with 200 bootstrap resamples applied to the two stable PLS components. Residual confounding was evaluated using E-value sensitivity analysis. Functional enrichment was used to identify genes contributing most strongly to each component, and component interpretation was assigned strictly post hoc, based on gene loadings and enriched functional categories, without imposing any biological labels during model training. Network topology of the stable components was visualized using NetworkX v3.3, with hub genes defined by degree and eigenvector centrality.

As an exploratory proof-of-concept, we trained a simple logistic-regression model using only PLS₁ and PLS₃ to evaluate whether these latent components captured meaningful variation associated with CRC status. Model performance was estimated using five-fold out-of-fold (OOF) predictions, with ROC-AUC confidence intervals obtained from 1000 bootstrap resamples and statistical significance assessed by a 1000-iteration permutation test. Calibration curves and OOF-derived predicted probabilities were used to construct low-, medium-, and high-score strata. This cross-validated logistic model constitutes the Dual-Axis Index (DAI), which we present as an exploratory summary index rather than a diagnostic classifier.

External validation and power analysis

To evaluate cross-cohort robustness, the two stable PLS components (PLS₁ and PLS₃) were validated in an independent CRC dataset using logistic regression with L1/L2 regularization. Prior to external validation, internal generalizability was assessed using a leave-one-cohort-out (LOCO) framework, in which the classifier was trained on two internal cohorts and tested on the third.

To assess biological consistency at the gene level, we compared effect directionality across cohorts using the difference in CLR-transformed abundance (ΔCLR = mean[Case] – mean[Control]) and evaluated significance using both Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Statistical power for detecting component-level differences was estimated using a one-way ANOVA–based power test (pwr.anova.test) assuming a moderate effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.3), α = 0.05, and a target power ≥ 0.8.

Data availability

All sequencing datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers provided in Supplementary Data S1.

Code availability

The GRUMB framework used for assembly-based taxonomic and ecological analyses is described in Aminu et al. (2025)74. The DAG developed in this study can be accessed at: https://dagitty.net/dags.html?id=KF2cp6jA. The full reproducible analysis scripts of the PLS-DML framework are available at https://github.com/AscanOfficiel2/CausoBiome.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Santucci, C. et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2024 with focus on colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 35, 308–316 (2024).

Elmadani, M. et al. Cancer burden in Europe: a systematic analysis of the GLOBOCAN database (2022). BMC Cancer 25, 447 (2025).

Ouakrim, D. A. et al. Trends in colorectal cancer mortality in Europe: retrospective analysis of the WHO mortality database. BMJ 351, h4970 (2015).

Megafu, O. M. An analysis of colorectal cancer in Ghana: implications for low and middle income countries. Am. J. Surg. 245, 116350 (2025).

Akoko, L. et al. Colorectal cancer in Tanzania: the current status and future directions. ecancermedicalscience 17, 1564 (2023).

Olfatifar, M. et al. Assessing the Colorectal Cancer Landscape: A Comprehensive Exploration of Future Trends in 216 Countries and Territories from 2021 to 2040. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 15, 5 (2025).

Garrett, W. S. Cancer and the microbiota. Science 348, 80–86 (2015).

Raskov, H., Burcharth, J. & Pommergaard, H.-C. Linking Gut Microbiota to Colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer 8, 3378–3395 (2017).

Loke, Y. L., Chew, M. T., Ngeow, Y. F., Lim, W. W. D. & Peh, S. C. Colon carcinogenesis: the interplay between diet and gut microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 1–26 (2020).

McBeth, A. et al. Balancing Oxidative Stress: How the Gut Microbiome Supports Redox Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Health. J. Restor. Med. 15, 4 (2025).

Aminu, S. et al. Exploring microbial worlds: a review of whole genome sequencing and its application in characterizing the microbial communities. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 805–829 (2024).

Gagnière, J. et al. Gut microbiota imbalance and colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 22, 501–518 (2016).

Kostic, A. D. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Potentiates Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Modulates the Tumor-Immune Microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 14, 207–215 (2013).

Wirbel, J. et al. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 25, 679–689 (2019).

Dougherty, M. W. & Jobin, C. Intestinal bacteria and colorectal cancer: etiology and treatment. Gut Microbes 15, 2185028 (2023).

Zeller, G. et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10, 766 (2014).

Feng, Q. et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Nat. Commun. 6, 6528 (2015).

Yu, J. et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 66, 70–78 (2017).

Yachida, S. et al. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal distinct stage-specific phenotypes of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 25, 968–976 (2019).

Thomas, A. M. et al. Metagenomic analysis of colorectal cancer datasets identifies cross-cohort microbial diagnostic signatures and a link with choline degradation. Nat. Med. 25, 667–678 (2019).

Pugazhendhi, A. S., Wei, F., Hughes, M. & Coathup, M. Bacterial Adhesion, Virulence, and Biofilm Formation. in Musculoskeletal Infection (ed. Coathup, M.) 19–64 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83251-3_2.

Shahoumi, L. A., Saleh, M. H. A. & Meghil, M. M. Virulence Factors of the Periodontal Pathogens: Tools to Evade the Host Immune Response and Promote Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 11, 115 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Species-level analysis of the human gut microbiome shows antibiotic resistance genes associated with colorectal cancer. Front. Microbiol. 12, 1–15 (2021).

Sears, C. L. & Garrett, W. S. Microbes, Microbiota and Colon Cancer. Cell Host Microbe 15, 317–328 (2014).

Jans, M. & Vereecke, L. Physiological drivers of pks+ E. coli in colorectal cancer. Trends Microbiol. 33, 1003–1017 (2025).

Ternes, D. et al. Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer: How to Get from Meta-omics to Mechanism? Trends Microbiol 28, 401–423 (2020).

Piccinno, G. et al. Pooled analysis of 3741 stool metagenomes from 18 cohorts for cross-stage and strain-level reproducible microbial biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 31, 2416–2429 (2025).

Dai, D. et al. GMrepo v2: a curated human gut microbiome database with special focus on disease markers and cross-dataset comparison. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D777–D784 (2022).

Fredriksen, S., de Warle, S., van Baarlen, P., Boekhorst, J. & Wells, J. M. Resistome expansion in disease-associated human gut microbiomes. Microbiome 11, 166 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. The role of bacterial cell envelope structures in acid stress resistance in E. coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 2911–2921 (2020).

Ma, Z. et al. Membrane lipid homeostasis dually regulates conformational transition of phosphoethanolamine transferase EptA. Nat. Commun. 15, 10166 (2024).

Groisman, E. A., Duprey, A. & Choi, J. How the PhoP/PhoQ System Controls Virulence and Mg2+ Homeostasis: Lessons in Signal Transduction, Pathogenesis, Physiology, and Evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 85, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00176-20 (2021).

Nazari, M., Hemmati, J. & Asghari, B. Comprehensive Analysis of Virulence Genes, Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm Formation, and Sequence Types in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 1403019 (2024).

Olamafar, E., Yadegar, A., Shahrokh, S., Ebrahimi, M. T. & Houri, H. Pathogenic Potential of Invasive Mucosa-Associated Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in Ulcerative Colitis: Characterization of Virulence Factors and Inflammatory Response. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 13, e70285 (2025).

Adhyaru, H. J., Mangroliya, D. B., Bhalu, A. B., Kabariya, J. H. & Ramani, V. M. Genomic insights into prevalence of virulence and multi drug resistance genes in milk borne Klebsiella pnuemoniae: Face of emerging resistance to last resort antibiotics. Microb. Pathog. 196, 106936 (2024).

Chen, H., Fang, Q., Zheng, L., Wu, Y. & Liang, W. Clonal Dynamics, Virulence Genes, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Early Diagnostic Indicators of Bloodstream Infections of Vibrio vulnificus in a Hospital in Eastern China from 2021 to 2024. Infect. Drug Resist. 18, 5173–5186 (2025).

Rodríguez-Miranda, E. et al. Differential Expression of fimH, ihf, upaB, and upaH Genes in Biofilms- and Suspension-Grown Bacteria From Samples of Different Uropathogenic Strains of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 5235071 (2024).

Habibi, M. et al. Immunization with recombinant protein Ag43::UpaH with alum and 1,25(OH)2D3 adjuvants significantly protects Balb/C mice against urinary tract infection caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Int. Immunopharmacol. 96, 107638 (2021).

Wallart, L. et al. BacA: a possible regulator that contributes to the biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1–16 (2024).

Vandeputte, D. et al. Quantitative microbiome profiling links gut community variation to microbial load. Nature 551, 507–511 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Multi-cohort metagenomics reveals strain functional heterogeneity and demonstrates fecal microbial load correction improves colorectal cancer diagnostic models. Front. Microbiol. 16, 1–12 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Dysbiosis of human gut microbiome in young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 6757 (2021).

Hampton, J. S. et al. The performance of FIT-based and other risk prediction models for colorectal neoplasia in symptomatic patients: a systematic review. eClinicalMed. 64, 1–36 (2023).

Monahan, K. J. et al. Faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in patients with signs or symptoms of suspected colorectal cancer (CRC): a joint guideline from the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) and the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327985.(2022).

Wang, N. & Fang, J.-Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a key pathogenic factor and microbial biomarker for colorectal cancer. Trends Microbiol. 31, 159–172 (2023).

Custer, G. F., Gans, M., van Diepen, L. T. A., Dini-Andreote, F. & Buerkle, C. A. Comparative Analysis of Core Microbiome Assignments: Implications for Ecological Synthesis. mSystems 8, e01066–22 (2023).

Cappellato, M., Baruzzo, G. & Camillo, B. D. Investigating differential abundance methods in microbiome data: A benchmark study. PLOS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010467 (2022).

Armour, C. R., Nayfach, S., Pollard, K. S. & Sharpton, T. J. A Metagenomic meta-analysis reveals functional signatures of health and disease in the human gut microbiome. mSystems 4, https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00332-18 (2019).

Kissami, I., Basmadjian, R., Chakir, O. & Abid, M. R. TOUBKAL: a high-performance supercomputer powering scientific research in Africa. J. Supercomput. 81, 1401 (2025).

Aminu, S. et al. Genome-resolved surveillance and predictive ecological risk modeling of urban microbiomes. Microbiome https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-025-02315-3 (2025).

Hannigan, G. D., Duhaime, M. B., Ruffin, M. T., Koumpouras, C. C. & Schloss, P. D. Diagnostic Potential and Interactive Dynamics of the Colorectal Cancer Virome. mBio 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02248-18 (2018).

B., B. BBTools software packag. e (2014).

Wingett, S. W. & Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research 7, 1338 (2018).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res 27, 824–834 (2017).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol 20, 257 (2019).

Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 3, e104 (2017).

Pan, A. Y. Statistical analysis of microbiome data: The challenge of sparsity. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 19, 35–40 (2021).

Yerke, A., Fry Brumit, D. & Fodor, A. A. Proportion-based normalizations outperform compositional data transformations in machine learning applications. Microbiome 12, 45 (2024).

Gibbons, S. M., Duvallet, C. & Alm, E. J. Correcting for batch effects in case-control microbiome studies. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006102 (2018).

Wen, T. et al. The best practice for microbiome analysis using R. Protein Cell 14, 713–725 (2023).

Alcock, B. P. et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D690–D699 (2023).

Liu, B., Zheng, D., Zhou, S., Chen, L. & Yang, J. VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res 50, D912–D917 (2022).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Kramer, O. Scikit-Learn. in Machine Learning for Evolution Strategies (ed. Kramer, O) 45–53 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33383-0_5.

Chernozhukov, V. et al. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econom. J. 21, C1–C68 (2018).

Hünermund, P., Louw, B. & Caspi, I. Double machine learning and automated confounder selection: A cautionary tale. J. Causal Inference 11, 1–12 (2023).

Knaus, M. C. Double machine learning-based programme evaluation under unconfoundedness. Econom. J. 25, 602–627 (2022).

Byeon, S. & Lee, W. Directed acyclic graphs for clinical research: a tutorial. J. Minim. Invasive Surg. 26, 97–107 (2023).

Tennant, P. W. G. et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 620–632 (2021).

Corander, J., Hanage, W. P. & Pensar, J. Causal discovery for the microbiome. Lancet Microbe 3, e881–e887 (2022).

Aminu, S., Ascandari, A., Benhida, R. & Daoud, R. GRUMB: a genome-resolved metagenomic framework for monitoring urban microbiomes and diagnosing pathogen risk. Bioinformatics 41, btaf548 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the African Supercomputing Center at Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P)73 for providing the high-performance computing resources used in this study. We are grateful to colleagues in the Department of Chemical and Biochemical Sciences at UM6P for their technical assistance and insightful discussions. We also acknowledge the open availability of metagenomic datasets from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), which enabled comparative analysis across cohorts. This work was supported by internal research funding granted to Dr. Rachid Daoud by Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation & Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. S.A.: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. R.B.: Scientific Oversight, Review & Editing. R.D.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ascandari, A., Aminu, S., Benhida, R. et al. Cross-cohort resistome and virulome gradients structure the colorectal cancer microbiome. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 12, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00905-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00905-5