Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a complex condition driven by inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic imbalances, calls for innovative treatment strategies. Engineered probiotics delivering angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) offer a promising strategy by leveraging gut microbiome-retina association. Advances in synthetic biology and computational techniques enable personalized, data-driven therapies. This review discusses computational approaches at multiple scales and presents an integrated framework for promoting personalized, systems-level DR management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a major sight-threatening complication of diabetes and a leading cause of vision loss worldwide1. Conventional treatments, such as controlling blood sugar levels and ocular procedures, can slow its progression but do not target its systemic causes. Increasing evidence underscores the impact of gut microbiome imbalance on inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic regulation, which are crucial in DR2,3,4. This concept, known as the “gut-retina axis,” offers new possibilities for therapeutic intervention5. Table S1 lists important factors related to DR pathogenesis, as reported in the literature.

Among systemic modulators, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has become a molecule of interest due to its role in maintaining vascular health and regulating inflammation6. While ACE2 has been studied in conditions such as cardiovascular disorders7, pulmonary arterial hypertension8, and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury9, its specific involvement in DR presents a unique upstream approach to restore balance in retinal and systemic pathways.

Synthetic biology offers innovative strategies for gut microbiome modulation. Engineered probiotics can be designed to deliver therapeutic molecules, enhance gut functions, and modulate host-microbe interactions related to DR10. Parallel advances in gene circuits, CRISPR-based editing, and bioencapsulation further expand the possibilities for targeted microbiome engineering11,12. However, ensuring precision, stability, and safety remains a challenge for clinical translation13.

Computational tools can support the design and prediction of therapeutic efficacy. Multi-omics integration, machine learning (ML), and biomechanical simulations provide systems-level insights into host–microbe interactions and help optimize engineered probiotics for therapeutic use.

In this review, we synthesize current knowledge on the ACE2 modulation through the gut microbiome and highlight how synthetic biology, computational systems biology, and artificial intelligence (AI) can converge to inform next-generation DR therapies. By connecting mechanistic insights with data-driven modeling, we present tools for personalized, microbiome-based interventions that advance conventional treatment approaches.

ACE2 and microbiome modulation in DR pathophysiology

RAS in DR. The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a complex hormonal cascade primarily involved in regulating blood pressure, electrolyte homeostasis, and fluid balance; however, its dysregulation contributes to retinal microvascular dysfunction14. Elevated levels of angiotensin II (Ang2), a key RAS effector, exert vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory, and pro-oxidative effects within the retina15. These actions promote endothelial dysfunction, increase vascular permeability, and induce cytokine and chemokine production, which activate leukocytes and amplify vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling16,17. Together, these processes lead to ischemia, vascular leakage, and diabetic macular edema.

Pharmacological inhibition of the RAS through angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or Ang2 receptor blockers (ARBs) can decrease inflammation and oxidative stress, which results in improved clinical outcomes in patients with DR. Therefore, targeting the RAS is a promising approach for managing DR and its related complications18.

ACE2 in DR. Beyond RAS blockade, attention has shifted toward ACE219, a protective factor that degrades Ang2 to produce angiotensin-(1–7) (Fig. 1)20. Reduced ACE2 activity in diabetes can disrupt this balance, favoring Ang2-mediated damage. Unlike ACE inhibitors or ARBs, which suppress Ang2 activity, targeting ACE2 restores this equilibrium21. Studies indicate that ACE2 deficiency exacerbates diabetes-induced vascular dysfunction and worsens DR, while Ang(1–7) supplementation restores impaired functions of bone marrow–derived CD34+ (Fig. 2)22. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of the ACE2/Ang(1–7) axis.

(top) Overview of the application of computational methods on diabetic retinopathy at different scales, with a focus on ACE2; (bottom) the renin-angiotensin system is upregulated during inflammatory states, resulting in increased synthesis of Ang2. This heightened production of Ang2 can happen both systemically and locally within organs, inducing vessel vasoconstriction. ACE2 can degrade Ang2 (ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; Ang2, angiotensin II; RAS, renin–angiotensin system).

a Representative OCT images showing reduced retinal thickness in diabetic cohorts (Akita and ACE2–/y-Akita groups) compared to wild-type and ACE2–/y groups. Quantification revealed a reduction in retinal thickness associated with diabetes, independent of ACE2 loss. b Fundus images illustrating a marked increase in white retinal lesions in ACE2–/y mice, indicative of retinal nerve fiber layer infarcts. These changes occurred regardless of diabetic status, implicating ACE2 deficiency as the primary driver (figure adapted with permission from22) (OCT, optical coherence tomography; ACE2–/y, ACE2 knockout mice).

However, systemic modulation of ACE2 is complicated. Over- or under-activation of ACE2 can disrupt the Ang2/Ang(1–7) balance, with systemic effects on blood pressure and other organs. Moreover, systemic delivery may not provide enough retinal concentrations and could cause off-target effects. The blood-retina barrier limits the entry of ACE-modulating agents into the retinal tissue, making effective delivery more difficult23,24. Another challenge arises from the interconnected processes underlying DR, where multiple pathological mechanisms contribute to its progression. While ACE2-based interventions may address inflammation, they do not directly counteract oxidative damage or neural degeneration25,26. Also, interindividual variability in ACE2 expression, affected by genetic and environmental factors27, further complicates the development of a one-size-fits-all therapeutic strategy.

These limitations have shifted research interests toward the gut microbiome, which can modulate ACE2 expression and activity through the gut-retina axis. Microbiota modulation offers an indirect yet systemic route to improve ACE2 regulation and provide complementary therapeutic benefits.

Regulation of ACE2

The gut microbiome and RAS engage in a dynamic, bidirectional interplay essential for homeostasis28. Microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other bioactive compounds, modulate systemic RAS activity, influencing inflammation, vascular function, and immune regulation. Conversely, RAS dysregulation can alter the gut environment, impacting microbiota composition and metabolic activity 29. This connection has prompted the exploration of microbiome-based interventions, such as probiotics and dietary supplements, which target upstream mechanisms of DR. These non-invasive solutions offer systemic benefits by modulating enzyme activity, including ACE2, across multiple tissues.

ACE2 serves as a critical link in this interaction. Predominantly expressed in gut epithelial cells, ACE2 regulates RAS by converting Ang2 into Ang(1–7), while also maintaining dietary amino acid transport, particularly tryptophan, and preserving gut barrier integrity 30,31,32. Dysregulation of ACE2 in the gut can cause systemic inflammation, increased intestinal permeability, and metabolic disturbances, all of which indirectly contribute to DR33,34. By modulating ACE2 expression, the gut microbiome emerges as a potential upstream regulator of both gut and systemic health (Box 1).

Engineering probiotics for human ACE2 delivery

To address the challenges associated with ACE2 regulation, synthetic biology offers strategies (see Box 2), including the design and development of engineered probiotics for targeted ACE2 delivery (Fig. 3). Safe probiotic strains can serve as live vectors for the oral administration of ACE2, engineered to enhance tissue bioavailability. This approach harnesses the interplay between the systemic and the tissue-specific RAS networks that collectively maintain physiological homeostasis.

This figure highlights examples of engineered approaches for microbiome-based therapy. a Metabolite-responsive genetic circuits. SCFA-sensing NOT-gate circuit in E. coli responds to propionate or butyrate and dials down a transgene, e.g., sfGFP or mGM-CSF. This leads to an inverse output at high SCFA levels (figure adapted from124, licensed under CC BY 4.0). b Design logic for living therapeutics. Disease-associated biomarkers are detected and processed by genetic circuits, and signals are then converted into programmed responses, such as therapeutic production, secretion, degradation, or surface display, with tunable feedback control (figure adapted with permission from125). c In-gut CRISPR-based modulation. Modulation of bacterial genes in the mammalian gut using encapsulated bacteriophages carrying CRISPR/dCas9 machinery. This enables targeted control of colonizing strains (figure adapted from126, licensed under CC BY 4.0) (SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; GFP, green fluorescent protein; mGM-CSF, murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats).

This figure illustrates a probiotic construct designed to express codon-optimized human ACE2127. The construct consists of the LDH promoter, a strong constitutive promoter derived from the lactate dehydrogenase gene of Lactobacillus acidophilus, which drives the expression of the gene cassette, starting with a signal peptide sequence from the Usp45 protein and CTB for enhanced stability. ACE2 is expressed as a secreted fusion protein alongside CTB. A furin cleavage site is positioned between ACE2 and CTB, which facilitates the release of ACE2 upon expression. The transcriptional terminator sequence ensures proper termination of mRNA synthesis (ACE2 angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CTB cholera toxin subunit B).

Engineered probiotic platforms. Lactobacillus paracasei has emerged as a leading candidate for recombinant probiotic delivery of human ACE235. A ubiquitous member of the gut microbiome, L. paracasei has been shown to strengthen barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins, and has demonstrated clinical benefit in conditions such as diarrhea and irritable bowel syndrome36. These properties make it a versatile platform for oral delivery, offering both localized gastrointestinal effects and systemic therapeutic potential. For detailed examples of engineered L. paracasei constructs designed for ACE2 delivery, see Box 3.

Barriers in probiotic therapeutics

Despite the promise, several challenges limit the translation of engineered probiotics into clinical therapies. One of the primary challenges is therapeutic dosage control: unlike conventional protein drug delivery systems, which can be timed to reach peak concentrations in the body, probiotics continuously secrete therapeutic proteins. As a result, the effective dosage depends on several factors beyond just protein expression levels and the initial bacteria dose37. Key among these variables is the survival and persistence of orally administered probiotics within the gastrointestinal tract. This variability complicates optimization of therapeutic outcomes.

Another unresolved challenge is understanding the broader biological impact of introducing recombinant strains into the human microbiome. Engineered bacteria may alter gut community composition or immune responses in unpredictable ways, particularly in patients with underlying health conditions38. Careful investigation into host–microbe interactions, stability of engineered strains, and potential off-target effects will be critical to ensuring safety. Targeted editing of gut microbes perturbs specific functions while largely preserving community composition, aiding safety evaluation.

Despite these challenges, engineered probiotics represent a promising delivery system for ACE2 and other therapeutic proteins. The success of such therapies hinges on overcoming these limitations through targeted research and development in synthetic biology, with the goal of optimizing the stability, safety, and efficacy of probiotic-based treatments.

Computational modeling in DR and microbiome research

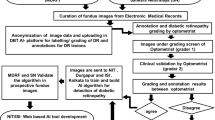

To address existing challenges, computational methods have become powerful tools. These approaches streamline the design and evaluation of engineered probiotics, predict survival and colonization dynamics, and simulate host-microbe interactions and metabolite production. More broadly, computational models integrate multi-omics datasets, identify microbial genes and pathways influencing key regulators such as ACE2, and optimize synthetic constructs for targeted interventions. In this way, systems-level computational tools provide a foundation for rational probiotic engineering, predictive biomarker discovery, and mechanistic insight into how gut microbiota influence diabetic retinopathy (Fig. 5).

Synthetic biology approaches, such as engineered probiotics, together with computational frameworks, enable the design and validation of next-generation therapeutic interventions (DR diabetic retinopathy, AI artificial intelligence, ML machine learning, DL deep learning, MD molecular dynamics, PLM protein language model).

High-throughput omics technologies

Advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have significantly deepened our understanding of the gut microbiome and its systemic impacts, including retinal health. By linking gut microbial diversity to host immune responses and metabolic pathways, these technologies can provide mechanistic insights into the microbiome’s role in disease pathogenesis (see Box 4).

Decoding microbial composition and function

Metagenomic sequencing enables the identification of microbial taxa and gene repertoires associated with key metabolic and inflammatory pathways relevant to DR. Genes encoding enzymes for pro-inflammatory mediators or anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as SCFAs, provide mechanistic links between gut dysbiosis and retinal injury39. Shotgun sequencing offers a broader view of microbial functional capacity, but interpretation is limited by its static nature40. Complementary metatranscriptomics adds a dynamic perspective and provide real-time insights into active microbial gene expression41. Such analyses reveal the temporal and contextual activity of microbial genes and further our understanding of the gut microbiome’s role in systemic inflammation and retinal disease progression42.

Bridging metabolism to retinal pathophysiology

Metabolomics, in particular, provides a tool for profiling gut microbiota-derived metabolites and determining their impact on host metabolic states via mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Changes in key microbial metabolites, including SCFAs, bile acids, and tryptophan derivatives, have been documented in DR patients, with significant correlations to disease severity and progression43,44. In efforts to explore the effect of dysbiosis in disease exacerbation, metabolomic analyses in proliferative DR revealed reduced microbial diversity and disrupted metabolite-host interactions39,45. These insights can hint at biomarkers but require validation across cohorts due to high interindividual variability. Proteomics extends this view by mapping host pathways impacted by microbial products, including those linked to inflammation and other DR-related processes. Dysregulation of proteins involved in immune signaling and angiogenesis has been reported in DR, with evidence suggesting modulation by the gut microbiota46,47. In parallel, transcriptomic analyses of retinal tissues reveal differential gene expression patterns that link metabolic disturbances to gut microbial dysbiosis48,49. Such integrative analyses highlight the complex molecular dialog between gut microbes and the retina.

Multi-omics data and AI

Integrating multi-omics data provides an understanding of how microbial diversity, metabolite production, and host inflammatory pathways interact in DR. Advanced bioinformatics and AI approaches provide the computational power to synthesize and analyze these large datasets, uncover novel biomarkers, and identify therapeutic targets. Such integrative approaches, discussed in the following, are pivotal for advancing precision medicine in DR or other systemic diseases.

AI-enabled microbiota analysis

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are transforming our ability to decode complex host–microbe relationships and profile the gut microbiome and its metabolites. Such approaches are particularly relevant in managing conditions like DR, where gut microbiota dysbiosis is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor50,51.

ML has proven instrumental in integrating diverse data types to identify molecular signatures associated with disease states. Supervised techniques like random forests and support vector machines excel in predictive modeling52,53,54, while unsupervised clustering methods reveal previously unrecognized microbial patterns55. For instance, studies integrating multi-omics data, including metagenomic and metabolomic profiles, have successfully stratified patients by microbial species and metabolic pathways linked to inflammatory and metabolic disorders56. More advanced methods like partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) further enhance biomarker discovery, with applications in identifying metabolic signatures relevant to DR57.

DL extends this capability by capturing highly non-linear relationships in microbiome data. Convolutional neural networks have been applied to phenotype prediction58, while graph neural networks (GNNs) model hierarchical and functional interactions within microbial communities59,60. Recent work shows the ability of GNNs to integrate multi-omics microbiome datasets and predict host phenotypes associated with inflammatory conditions61. This graph-based perspective is relevant to the gut-retina axis, where interactions among microbial species, metabolites, and host pathways may drive DR progression.

The utility of a GNN is fundamentally dependent on the underlying graph structure. Many early applications relied on simple correlation-based graphs, which may not reflect actual biological mechanisms. New computational frameworks use graph-based approaches to bridge mechanistic predictions with deep learning. For instance, SIMBA provides a scalable framework for integrating metabolic-based interaction graphs with a custom graph transformer62. Such approaches show how AI can be trained on biological first principles rather than just statistical association.

AI in probiotic research

Probiotic research has greatly benefited from ML and DL advancements, particularly in strain identification, functional prediction, and efficacy optimization. Platforms like iProbiotics employ ML algorithms to rapidly identify probiotic strains based on genomic and phenotypic data, streamlining the discovery and development process63. DL models have been influential in predicting functional traits of gut microbiota, such as the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging enzymes, which are crucial for mitigating oxidative stress64. Time-series models, including recurrent neural networks (RNNs), can be used to evaluate the longitudinal impact of probiotics on gut microbial composition and systemic health65. This kind of research enables the optimization of probiotic formulations for specific therapeutic outcomes.

Limitations of AI/ML models

Microbiome datasets are relatively small in size and heterogeneous in quality, and this makes them prone to overfitting with less generalizability across populations. Many algorithms lack interpretability, which constrains clinical trust and adoption, particularly when it comes to therapeutic design. Most models rely on cross-sectional data, whereas longitudinal datasets are essential for capturing dynamic host–microbe interactions relevant to DR. Validation of AI-informed predictions in clinical studies is still limited; this highlights the importance of translational pipelines before clinical applications. Emerging computational strategies are beginning to address these limitations.

With the rise of large language models (LLMs), LLM–powered agents are being developed to integrate heterogeneous microbiome datasets, guide hypothesis generation, and provide context-aware explanations for model predictions66. These advances hold promise for making AI-driven microbiome research both more reliable and clinically actionable.

Metabolic networks and constraint-based tools

Microbial ecosystems are highly dynamic, with species engaging in complex cooperative and competitive metabolic interactions. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a systems framework to map metabolic capabilities from genomic sequences and predict phenotypic responses to perturbations. By linking genotypes to phenotypes, GEMs enable the design of microbial communities with tailored traits, guide therapeutic strategies, and support applications in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and precision medicine67 (see Box 5).

GEM reconstruction and challenges

GEMs are reconstructed from genomic sequences using annotation-based methods to define metabolic networks. Automated pipelines expedite this process68,69; however, incomplete or fragmented genomes, common in metagenome-assembled data, can induce gaps and inaccuracies70,71. To address this, recent methods like the pan-Draft approach72, GECKO toolbox73, CLOSEgaps74, and ModelSEED v275 incorporate evidence from multiple genomes to improve accuracy. Still, manual curation along with detailed experimental data are essential to ensure reliable reconstructions76,77.

Constraint-based models

A core method within GEMs is flux balance analysis (FBA), which applies linear programming to predict steady-state metabolic fluxes, often optimizing for an objective function, such as biomass production78. In microbial communities, this technique oversimplifies the complexities of interspecies interactions and must be adapted to account for the metabolic crosstalk among community members. Extensions like OptCom79 and MICOM80 address this by incorporating multi-level optimization strategies to balance individual- and community-level objectives. More recent adaptations, including community FBA (cFBA)81 and SteadyCom82, enforce synchronized growth rates across community members and improve predictions of substrate utilization and metabolite exchange dynamics.

Insights into ACE2 regulation through GEMs

Direct applications of GEMs to ACE2 regulation remain limited; however, these models can illuminate upstream metabolic contexts that shape enzyme expression and activity. By simulating fluxes through pathways involved in angiotensin peptide synthesis and related networks, GEMs can help predict how metabolic shifts might alter ACE2-relevant processes. While GEMs do not directly predict protein abundance, methods such as ΔFBA83, which integrate differential gene expression data with GEM constraints, can refine flux predictions and highlight dysregulated pathways in diseases. Integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data further improves model contextualization and can help nominate candidate targets for ACE2 modulation84 (see Box 6). GEMs can also explore drug interactions: for instance, simulating how ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers influence RAS components and mapping these effects onto broader metabolic networks85,86.Beyond characterization, metabolic networks have been used to identify candidate drug targets by comparing structural similarities between human metabolites and chemical libraries87.

Limitations of constraint-based models

Metagenome-assembled genomes are often incomplete, and gaps in annotation can propagate errors into metabolic reconstructions. Model assumptions can oversimplify the non-equilibrium nature of microbial communities. Microbe-host interactions add further complexity, as GEMs rarely capture immune responses, spatial heterogeneity, or signaling cascades. Importantly, predictions from GEMs must be experimentally validated, and this becomes increasingly demanding at a community scale. These challenges underscore the importance of integrating metabolic networks with complementary approaches and validating them in physiology-relevant systems.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are common biophysical computational tools that provide detailed insights into the structural dynamics and interactions within biomolecular systems. Docking, commonly used in virtual screening, provides a prediction of how a ligand binds to a protein’s binding site, resulting in static binding poses and associated binding affinities. MD simulations additionally model the physical movements of ions and molecules over time, generating dynamic trajectories and evaluating stability of protein-ligand complexes that capture quantitative information, such as Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF), material coefficients, thermodynamic and kinetic information of events, and specific intermolecular force contributions88. Together, these simulations can show how molecules, produced by engineered probiotics, interact with host proteins and receptors, such as ACE2 and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)89. By modeling these interactions, researchers can predict binding affinities, identify potential binding sites, and analyze the conformational changes that occur upon binding. This level of detail is important for designing probiotics that effectively modulate ACE2 activity. Crucially, these computational simulations not only generate powerful mechanistic hypotheses but are inherently predictive; their findings require following experimental validation through in vitro binding assays and testing in animal models to confirm biological relevance.

Docking has been extensively used to virtually screen large libraries of small molecule binding inhibitors between ACE2 and other biologically relevant receptor binding domains88,90,91. Predictions such as binding affinity, ligand poses, and protein-protein interactions can be utilized to identify microbial compounds and derived metabolites with potential to modulate pathways and mechanisms of interest to DR. To further understand such mechanisms, MD simulations have been used to investigate the binding and activation mechanisms of SCFAs on free fatty acid receptors (FFARs), specifically FFAR2 and FFAR392. MD simulations can also be used to explore lipid-protein interactions, focusing on how membrane lipids influence the function of biological molecules93.

Gut barrier and tight junctions

Maintaining gut barrier integrity is important for reducing systemic inflammation and preventing the translocation of harmful molecules into the host cardiovascular system94. MD simulations have been used to study conformational dynamics of tight junction proteins, such as claudins, and their role in regulating paracellular permeability95,96. These models highlight how microbial metabolites and signaling molecules affect pore size and stability and offer mechanistic explanations for barrier disruption or reinforcement. Such insights are directly relevant to probiotic-based strategies aimed at strengthening gut and retinal vascular barriers.

Microbe-derived signaling molecules

MD approaches have also elucidated how microbial components, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), interact with immune receptors like Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and their ligands. Detailed analyses have shown the structural and molecular mechanisms underlying TLR activation and selectivity. Simulations of TLR4-MD2-(myeloid differentiation factor 2)-LPS complexes, for example, revealed important hydrophobic clusters within MD2 mediating receptor dimerization and activation97. Similar studies on TLR8 show how ligand selectivity fine-tunes immune responses98. These findings deepen understanding of how microbial molecules drive inflammatory cascades in DR and may inform rational design of probiotic metabolites or small molecules to modulate TLR signaling99.

Quorum sensing and microbial balance

Quorum sensing (QS) is a bacterial communication mechanism through which bacteria coordinate gene expression based on their population density by producing, releasing, and detecting signaling molecules100. QS regulates various microbial functions, including biofilm formation, virulence, and competition between bacterial species101,102.

Probiotics can influence QS systems by disrupting pathogenic signaling or enhancing beneficial pathways103. Pathogenic bacteria often rely on QS to establish dominance within the gut, which results in dysbiosis104,105. On the other hand, probiotics and their metabolites can act as QS inhibitors; they interfere with pathogenic communication systems to restore microbial balance106. QS in commensal or probiotic bacteria also facilitates cooperative behaviors, such as nutrient sharing and synchronized biofilm formation, which collectively support gut integrity and function107.

Docking and MD simulations can characterize interactions between QS signals and regulatory proteins108. Extending these techniques to ACE2-related processes may aid in exploring ligand-protein complexes over time and also predicting drug-likeliness and ADMET profiling of candidate microbial compounds109,110,111.

Limitations of molecular dynamics

Molecular docking’s primary limitation is that it simply scores the binding of rigid molecules using simplified criteria functions. This oversimplification can lead to inaccuracies in predicting the binding affinity between proteins and ligands from their true in vivo interactions. MD simulations are computationally expensive, typically limited to capturing nanosecond- to microsecond-scale dynamics on supercomputing clusters, whereas biological processes such as receptor activation and chronic inflammation occur over much longer timescales. Both methods are limited by the accuracy of approximate force fields, and solvent models may not fully replicate physiological environments.

Despite these limitations, proper use and integration of docking and MD can be powerful. Docking’s simplicity makes it fast, ideal for narrowing down large libraries of small molecules, while the more computationally intensive MD can be run on fewer systems. MD should be viewed as a powerful hypothesis-generating tool, best used in combination with experimental validation and systems-level modeling to extend findings to tissue-level outcomes.

Protein structure prediction toolchains

Computational protein structure prediction tools, such as AlphaFold and Rosetta, have transformed structural biology by enabling accurate modeling of protein conformations and interactions, even in the absence of experimental data. Such tools can play a critical role in understanding the subtle structural interactions of ACE2 within the context of the RAS in the scope of DR.

Using AlphaFold to resolve unknown structures

Much of the preceding work on the structural mechanics of ACE2 has been done in the context of its role as an infection vector for COVID-19. AlphaFold-predicted ACE2 conformations were used to validate structural models of ACE2 orthologous peptides before docking and molecular dynamics simulations, enabling the design of inhibitory peptides with enhanced binding affinity90. Similarly, AlphaFold has been used with ACE2 to gain a glimpse into the nature of its interaction with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, by generating protein structures of structurally unknown biological compounds to understand if the disruption of ACE2 binding could result in potentially harmful side effects in the host’s system88.

Beyond viral entry, these approaches can be extended to DR by modeling ACE2 variants, isoforms, or post-translational modifications that may shift enzymatic activity or binding affinity for Ang2/Ang-(1–7)112,113,114. AlphaFold can prioritize ACE2 complex partners and potential interface clashes, particularly when filtered by retina single-cell data115 or proteomics to focus on tissue-relevant interactors116. Coupling AlphaFold-informed docking with molecular dynamics then guides the rational design of peptides, small molecules, or even microbial metabolites that stabilize ACE2’s protective function while avoiding disruption of native interactions117.

Validating predicted protein structures

Rosetta, a popular computational suite for macromolecular modeling, complements AlphaFold by refining structural predictions, exploring conformational landscapes, and performing energy-based docking and design118. On its own, Rosetta has been successfully used for ACE2 to create soluble receptor variants with improved binding affinity to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein119 and ACE2-derived peptides that can act as competitive inhibitors120. More recently, hybrid pipelines that combine AlphaFold’s structural accuracy with Rosetta’s energetic refinement and flexible docking capabilities have enhanced the modeling of protein–protein interactions and ligand docking121.

Integrating structural prediction with validation

Integrating Rosetta with AlphaFold in the context of DR can be used to improve AlphaFold-predicted models of ACE2 and its interactors, resample docking poses to account for conformational changes, and design peptides or small molecules that maintain ACE2’s protective Ang-(1–7) signaling cascade. This approach not only aids in identifying candidate therapeutics118,121, but also provides energy-based validation of ACE2’s structural stability under diabetic conditions, such as oxidative stress. By combining AlphaFold’s predictive power with Rosetta’s design tools, researchers can create a rational workflow for developing ACE2-targeted interventions that protect retinal tissues while minimizing disruption of ACE2’s natural biological interactions.

Prospects

The multifaceted etiology of DR calls for innovative and comprehensive therapeutic strategies (see Box 7). Engineered probiotics designed to deliver therapeutic molecules offer a promising strategy to address systemic and retinal complications of diabetes. The gut microbiota’s pivotal role in modulating ACE2 expression highlights its potential as a therapeutic target for DR. Advances in probiotic engineering and metagenomics have made the precise manipulation of the microbiome increasingly feasible, paving the way for effective interventions.

Recent breakthroughs in computational biology have further boosted the potential of microbiome-based therapies. Within the next few years, it is realistic to expect these tools to yield significant clinical advancements. ML and DL have already revolutionized microbiome research by enabling sophisticated analyses of complex datasets. This will likely lead to validated predictive models that can identify microbial patterns to stratify patient risk for DR.

By analyzing baseline microbiome profiles alongside metagenomic and other omics data, AI systems can be refined to predict individual responses to probiotic treatments. This can guide the design of more targeted clinical trials (see Box 8). Moreover, the rise of explainable frameworks will be important in translating these complex computational predictions into clinical practice by making them interpretable to clinicians122,123.

Looking further ahead, the long-term vision for this field remains more speculative. Future directions emphasize hybrid computational models that incorporate microbiome, host genomic, and clinical data to provide a holistic understanding of host-microbiome interactions. The ultimate, though still distant, goal is to use these capabilities for truly personalized medicine and data-driven healthcare, where interventions are tailored to an individual’s unique biological landscape. However, several challenges must be addressed to fully realize this potential. Experimental validation of computational predictions remains a challenge, as does the gap between predictions and clinical reality. Many proposed interventions remain untested in animal models or early-phase trials, and discrepancies frequently emerge when computationally optimized strategies are applied in vivo. Bridging this divide will require standardized pipelines for validation, multi-omics datasets collected across diverse populations, and iterative feedback loops between computational modeling and experimental or clinical studies. Fostering interdisciplinary collaboration across microbiology, computational biology, and clinical sciences will be essential to overcoming these challenges. Also, ethical considerations related to data privacy must be prioritized to ensure responsible and equitable advancement of these transformative technologies.

The intersection of microbiome research, synthetic biology, and computational tools provides an exciting frontier for addressing the multifactorial challenges of DR. Through these innovations, we can move closer to holistic and personalized therapeutic solutions that benefit individuals with diabetes and its complications.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study & GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by diabetic retinopathy: A meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye 38, 2047–2057 (2024).

Liu, K., Zou, J., Fan, H., Hu, H. & You, Z. Causal effects of gut microbiota on diabetic retinopathy: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 13, 930318 (2022).

Qin, X. et al. Gut microbiota predict retinopathy in patients with diabetes: A longitudinal cohort study. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108, 497 (2024).

Jiang, S.-Q. et al. Gut microbiota induced abnormal amino acids and their correlation with diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 17, 883–895 (2024).

Thakur, P. S., Aggarwal, D., Takkar, B., Shivaji, S. & Das, T. Evidence suggesting the role of gut dysbiosis in diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 21 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in Human Retina and Diabetes—Implications for Retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62, 6–6 (2021).

Oudit, G. Y. & Pfeffer, M. A. Plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: Novel biomarker in heart failure with implications for COVID-19. Eur. Heart J. 41, 1818–1820 (2020).

Bradford, C. N., Ely, D. R. & Raizada, M. K. Targeting the vasoprotective axis of the renin-angiotensin system: a novel strategic approach to pulmonary hypertensive therapy. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 12, 212–219 (2010).

Xie, J.-X., Hu, J., Cheng, J., Liu, C. & Wei, X. The function of the ACE2/Ang(1-7)/Mas receptor axis of the renin-angiotensin system in myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Eur. Rev. Med Pharm. Sci. 26, 1852–1859 (2022).

Praveschotinunt, P. et al. Engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 for the delivery of matrix-tethered therapeutic domains to the gut. Nat. Commun. 10, 5580 (2019).

Robinson, C. M., Short, N. E. & Riglar, D. T. Achieving spatially precise diagnosis and therapy in the mammalian gut using synthetic microbial gene circuits. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 959441 (2022).

Riglar, D. T. et al. Engineered bacteria can function in the mammalian gut long-term as live diagnostics of inflammation. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 653–658 (2017).

Merenstein, D. et al. Emerging issues in probiotic safety: 2023 perspectives. Gut Microbes 15, 2185034 (2023).

Lovshin, J. A. et al. Retinopathy and RAAS activation: Results from the Canadian Study of longevity in type 1 diabetes. Diab. Care 42, 273–280 (2019).

Verma, A. et al. ACE2 and Ang-(1-7) confer protection against development of diabetic retinopathy. Mol. Ther. 20, 28–36 (2012).

Wang, L. et al. High glucose induces and activates toll-like receptor 4 in endothelial cells of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 7, 89 (2015).

Vezza, T. & Víctor, V. M. The HIF1α-PFKFB3 pathway: A key player in diabetic retinopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, e4778–e4780 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Effects of RAS inhibitors on diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 3, 263–274 (2015).

Phipps, J. A. et al. The renin-angiotensin system and the retinal neurovascular unit: A role in vascular regulation and disease. Exp. Eye Res. 187, 107753 (2019).

Verma, A. et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) expressed from lactobacillus bacteria protect diabetic retina in mice. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9, 20–20 (2020).

Tao, L. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activator diminazene aceturate prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB pathways in human retinal pigment epithelium. J. Neuroinflamm. 13, 35 (2016).

Duan, Y. et al. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 exacerbates diabetic retinopathy by promoting bone marrow dysfunction. Stem Cells 36, 1430–1440 (2018).

Liu, L. & Liu, X. Roles of drug transporters in blood-retinal barrier. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1141, 467–504 (2019).

Bleker, S. et al. Modulation of the blood-retina-barrier permeability by focused ultrasound: Computational and experimental approaches. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, A68–A68 (2023).

Eleftheriadou, A. et al. Risk of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema with sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: a real-world data study from a global federated database. Diabetologia 67, 1271–1282 (2024).

Toprak, I., Fenkci, S. M., Fidan Yaylali, G., Martin, C. & Yaylali, V. Early retinal neurodegeneration in preclinical diabetic retinopathy: a multifactorial investigation. Eye (Lond.) 34, 1100–1107 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Individual variation of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 gene expression and regulation. Aging Cell 19, e13168 (2020).

Gotoh, K. & Shibata, H. Association between the gut microbiome and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a possible link via the activation of the immune system. Hypertens. Res 46, 2315–2317 (2023).

Jaworska, K., Koper, M. & Ufnal, M. Gut microbiota and renin-angiotensin system: a complex interplay at local and systemic levels. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 321, G355–G366 (2021).

Vuille-dit-Bille, R. N. et al. Human intestine luminal ACE2 and amino acid transporter expression increased by ACE-inhibitors. Amino Acids 47, 693–705 (2015).

Song, L., Ji, W. & Cao, X. Integrated analysis of gut microbiome and its metabolites in ACE2-knockout and ACE2-overexpressed mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1404678 (2024).

Hashimoto, T. et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature 487, 477–481 (2012).

Jena, L. et al. Gene expression analysis in T2DM and its associated microvascular diabetic complications: Focus on risk factor and RAAS pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 8656–8667 (2024).

Zhao, L. et al. Untargeted metabolomics uncovers metabolic dysregulation and tissue sensitivity in ACE2 knockout mice. Heliyon 10, e27472 (2024).

Mei, X. et al. Genetically engineered Lactobacillus paracasei rescues colonic angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and attenuates hypertension in female Ace2 knock out rats. Pharmacol. Res. 196, 106920 (2023).

Zeng, Z., Guo, X., Zhang, J., Yuan, Q. & Chen, S. Lactobacillus paracasei modulates the gut microbiota and improves inflammation in type 2 diabetic rats. Food Funct. 12, 6809–6820 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Lactobacillus paracasei 24 Attenuates Lipid Accumulation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice by Regulating the Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 70, 4631–4643 (2022).

Prasad, R. et al. Sustained ACE2 expression by probiotic improves integrity of intestinal lymphatics and retinopathy in type 1 diabetic model. J. Clin. Med. Res. 12, 1771 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing and metabolomic profiling identify specific human gut microbiota associated with diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Front Immunol. 13, 943325 (2022).

Quince, C., Walker, A. W., Simpson, J. T., Loman, N. J. & Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 833–844 (2017).

Nancy, Boparai, J. K. & Sharma, P. K. Metatranscriptomics: A promising tool to depict dynamics of microbial community structure and function. Microb. Metatranscriptomics Belowground 471, 491 (2021).

Prasad, R. et al. Ile-Trp dipeptide prevents diabetic retinopathy via gut Indole/AhR/PXR signaling in type 2 diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 844–844 (2024).

Guo, C. et al. High-coverage serum metabolomics reveals metabolic pathway dysregulation in diabetic retinopathy: A propensity score-matched study. Front Mol. Biosci. 9, 822647 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Sodium butyrate ameliorates diabetic retinopathy in mice via the regulation of gut microbiota and related short-chain fatty acids. J. Transl. Med. 21, 451 (2023).

Ye, P. et al. Alterations of the gut microbiome and metabolome in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Front Microbiol 12, 667632 (2021).

Dao, D. et al. High-fat diet alters the retinal transcriptome in the absence of gut Microbiota. Cells 10, 2119 (2021).

Huang, Q. et al. Biomarker identification by proteomic analysis of vitreous humor and plasma in diabetic retinopathy. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.18.594835 (2024).

Becker, K. et al. In-depth transcriptomic analysis of human retina reveals molecular mechanisms underlying diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 11, 10494 (2021).

Zhang, R., Huang, C., Chen, Y., Li, T. & Pang, L. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealing changes in retinal cell subpopulation levels and the pathways involved in diabetic retinopathy. Ann. Transl. Med. 10, 562 (2022).

Mouzaki, M. & Loomba, R. Insights into the evolving role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Rationale and prospects for therapeutic intervention. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 12, 1756284819858470 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Elevated plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide levels are associated with diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 58, 221–229 (2021).

Ai, D. et al. Using decision tree aggregation with random forest model to identify gut microbes associated with colorectal cancer. Genes (Basel) 10, 112 (2019).

Aryal, S., Alimadadi, A., Manandhar, I., Joe, B. & Cheng, X. Machine learning strategy for gut microbiome-based diagnostic screening of cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 76, 1555–1562 (2020).

Liu, W., Fang, X., Zhou, Y., Dou, L. & Dou, T. Machine learning-based investigation of the relationship between gut microbiome and obesity status. Microbes Infect. 24, 104892 (2022).

Yang, D. & Xu, W. Clustering on human microbiome sequencing data: A distance-based unsupervised learning model. Microorganisms 8, 1612 (2020).

Ning, L. et al. Microbiome and metabolome features in inflammatory bowel disease via multi-omics integration analyses across cohorts. Nat. Commun. 14, 7135 (2023).

Pang, Y. et al. Multi-omics integration with machine learning identified early diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macula edema and anti-VEGF treatment response. Trans. Vis. Sci. Tech. 13, 23–23 (2024).

Shtossel, O., Isakov, H., Turjeman, S., Koren, O. & Louzoun, Y. Ordering taxa in image convolution networks improves microbiome-based machine learning accuracy. Gut Microbes 15, 2224474 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. An explainable graph neural framework to identify cancer-associated intratumoral microbial communities. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 11, e2403393 (2024).

Chen, Y. & Lei, X. Metapath aggregated graph neural network and tripartite heterogeneous networks for microbe-disease prediction. Front. Microbiol. 13, 919380 (2022).

Irwin, C., Mignone, F., Montani, S. & Portinale, L. Graph neural networks for gut microbiome metaomic data: A preliminary work. arXiv [cs.LG] (2024).

Parsa, M., Aminian-Dehkordi, J. & Mofrad, M. R. K. SIMBA-GNN: Simulation-augmented microbiome abundance graph neural network. bioRxiv 2025–2005 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. iProbiotics: a machine learning platform for rapid identification of probiotic properties from whole-genome primary sequences. Brief Bioinform. 23, bbab477 (2022).

Yan, Y., Shi, Z. & Zhang, Y. Hierarchical multi-task deep learning-assisted construction of human gut microbiota reactive oxygen species-scavenging enzymes database. mSphere 9, e0034624 (2024).

Thompson, J. C., Zavala, V. M. & Venturelli, O. S. Integrating a tailored recurrent neural network with Bayesian experimental design to optimize microbial community functions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011436 (2023).

Dehkordi, J. A., Parsa, M. S., Naghipourfar, M. & Mofrad, M. KODA: An agentic framework for KEGG orthology-driven discovery of antimicrobial drug targets in gut microbiome. in ICML 2025 Generative AI and Biology (GenBio) Workshop (2025).

Gu, C., Kim, G. B., Kim, W. J., Kim, H. U. & Lee, S. Y. Current status and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Genome Biol. 20, 121 (2019).

Vayena, E. et al. A workflow for annotating the knowledge gaps in metabolic reconstructions using known and hypothetical reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 119, e2211197119 (2022).

Hsieh, Y. E., Tandon, K., Verbruggen, H. & Nikoloski, Z. Comparative analysis of metabolic models of microbial communities reconstructed from automated tools and consensus approaches. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 10, 54 (2024).

Chen, L.-X., Anantharaman, K., Shaiber, A., Eren, A. M. & Banfield, J. F. Accurate and complete genomes from metagenomes. Genome Res 30, 315–333 (2020).

Borer, B. & Magnúsdóttir, S. The media composition as a crucial element in high-throughput metabolic network reconstruction. Interface Focushttps://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2022.0070 (2023).

De Bernardini, N. et al. pan-Draft: automated reconstruction of species-representative metabolic models from multiple genomes. Genome Biol. 25, 280 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Reconstruction, simulation and analysis of enzyme-constrained metabolic models using GECKO Toolbox 3.0. Nat. Protoc. 19, 629–667 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Deep learning-driven automatic reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic networks. Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2605759/v1 (2023).

Faria, J. P. et al. ModelSEED v2: High-throughput genome-scale metabolic model reconstruction with enhanced energy biosynthesis pathway prediction. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.04.556561 (2023).

Heinken, A., Magnúsdóttir, S., Fleming, R. M. T. & Thiele, I. DEMETER: efficient simultaneous curation of genome-scale reconstructions guided by experimental data and refined gene annotations. Bioinformatics 37, 3974–3975 (2021).

Aminian-Dehkordi, J., Mousavi, S. M., Jafari, A., Mijakovic, I. & Marashi, S.-A. Manually curated genome-scale reconstruction of the metabolic network of Bacillus megaterium DSM319. Sci. Rep. 9, 18762 (2019).

Orth, J. D., Thiele, I. & Palsson, B. Ø What is flux balance analysis?. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 245–248 (2010).

Zomorrodi, A. R. & Maranas, C. D. OptCom: a multi-level optimization framework for the metabolic modeling and analysis of microbial communities. PLoS Comput Biol. 8, e1002363 (2012).

Diener, C., Gibbons, S. M. & Resendis-Antonio, O. MICOM: Metagenome-scale modeling to infer metabolic interactions in the gut Microbiota. mSystems 5, 10–1128 (2020).

Khandelwal, R. A., Olivier, B. G., Röling, W. F. M., Teusink, B. & Bruggeman, F. J. Community flux balance analysis for microbial consortia at balanced growth. PLoS One 8, e64567 (2013).

Chan, S. H. J., Simons, M. N. & Maranas, C. D. SteadyCom: Predicting microbial abundances while ensuring community stability. PLoS Comput Biol. 13, e1005539 (2017).

Ravi, S. & Gunawan, R. ΔFBA-Predicting metabolic flux alterations using genome-scale metabolic models and differential transcriptomic data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009589 (2021).

Zare, F. & Fleming, R. M. T. Integration of proteomic data with genome-scale metabolic models: A methodological overview. Protein Sci. 33, e5150 (2024).

Di Filippo, M. et al. INTEGRATE: Model-based multi-omics data integration to characterize multi-level metabolic regulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1009337 (2022).

Cordes, H., Thiel, C., Baier, V., Blank, L. M. & Kuepfer, L. Integration of genome-scale metabolic networks into whole-body PBPK models shows phenotype-specific cases of drug-induced metabolic perturbation. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 4, 10 (2018).

O’Hagan, S. & Kell, D. B. Understanding the foundations of the structural similarities between marketed drugs and endogenous human metabolites. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 105 (2015).

Milanetti, E., Miotto, M., Bo, L., Di Rienzo, L. & Ruocco, G. Investigating the competition between ACE2 natural molecular interactors and SARS-CoV-2 candidate inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Interact. 374, 110380 (2023).

Latorraca, N. R., Venkatakrishnan, A. J. & Dror, R. O. GPCR dynamics: Structures in motion. Chem. Rev. 117, 139–155 (2017).

Mahmoudi Azar, L. et al. Human ACE2 orthologous peptide sequences show better binding affinity to SARS-CoV-2 RBD domain: Implications for drug design. Comput Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 4096–4109 (2023).

Isaac-Lam, M. F. Molecular modeling of the interaction of ligands with ACE2-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein complex. Silico Pharm. 9, 55 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Molecular recognition and activation mechanism of short-chain fatty acid receptors FFAR2/3. Cell Res 34, 323–326 (2024).

Tieleman, D. P. et al. Insights into lipid-protein interactions from computer simulations. Biophys. Rev. 13, 1019–1027 (2021).

Ghosh, S. S., Wang, J., Yannie, P. J. & Ghosh, S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction, LPS translocation, and disease development. J. Endocr. Soc. 4, bvz039 (2020).

Tervonen, A., Ihalainen, T. O., Nymark, S. & Hyttinen, J. Structural dynamics of tight junctions modulate the properties of the epithelial barrier. PLoS One 14, e0214876 (2019).

Alberini, G., Benfenati, F. & Maragliano, L. A refined model of claudin-15 tight junction paracellular architecture by molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One 12, e0184190 (2017).

Tafazzol, A. & Duan, Y. Key residues in TLR4-MD2 tetramer formation identified by free energy simulations. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007228 (2019).

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, S. & Deng, J. N. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal the selectivity mechanism of structurally similar agonists to TLR7 and TLR8. PLoS One 17, e0260565 (2022).

Billod, J.-M., Lacetera, A. & Guzmán-Caldentey, J. & Martín-Santamaría, S. Computational approaches to toll-like receptor 4 modulation. Molecules 21, 994 (2016).

Oliveira, R. A., Cabral, V., Torcato, I. & Xavier, K. B. Deciphering the quorum-sensing lexicon of the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 31, 500–512 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Pan, X., Wang, L. & Chen, L. Iron metabolism in biofilm and the involved iron-targeted anti-biofilm strategies. J. Drug Target 29, 249–258 (2021).

Uhlig, F. et al. Identification of a quorum sensing-dependent communication pathway mediating bacteria-gut-brain cross talk. iScience 23, 101695 (2020).

Murali, M. et al. Exploration of CviR-mediated quorum sensing inhibitors from Cladosporium spp. against Chromobacterium violaceum through computational studies. Sci. Rep. 13, 15505 (2023).

Venkatramanan, M. et al. Inhibition of Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in by Fruit Extracts of. ACS Omega 5, 25605–25616 (2020).

Shapiro, L. & Losick, R. Cell Biology of Bacteria: A Subject Collection from Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. (2011).

Devi, S., Chhibber, S. & Harjai, K. Optimization of cultural conditions for enhancement of anti-quorum sensing potential in the probiotic strain GG against. 3 Biotech 12, 133 (2022).

Abisado, R. G., Benomar, S., Klaus, J. R., Dandekar, A. A. & Chandler, J. R. Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Microbial Community Interactions. mBiohttps://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02331-17 (2018).

Kalia, V. C. Biotechnological Applications of Quorum Sensing Inhibitors. (Springer, 2018).

Shanmugarajan, D. P. P., Kumar, B. R. P. & Suresh, B. Curcumin to inhibit binding of spike glycoprotein to ACE2 receptors: Computational modelling, simulations, and ADMET studies to explore curcuminoids against novel SARS-CoV-2 targets. RSC Adv. 10, 31385–31399 (2020).

Mansour, M. A., AboulMagd, A. M. & Abdel-Rahman, H. M. Quinazoline-Schiff base conjugates: study and ADMET predictions as multi-target inhibitors of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) proteins. RSC Adv. 10, 34033–34045 (2020).

Da, A., Wu-Lu, M., Dragelj, J., Mroginski, M. A. & Ebrahimi, K. H. Multi-structural molecular docking (MOD) combined with molecular dynamics reveal the structural requirements of designing broad-spectrum inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 entry to host cells. Sci. Rep. 13, 16387 (2023).

Cheng, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 381, eadg7492 (2023).

Onabajo, O. O. et al. Interferons and viruses induce a novel truncated ACE2 isoform and not the full-length SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Nat. Genet. 52, 1283–1293 (2020).

Mehdipour, A. R. & Hummer, G. Dual nature of human ACE2 glycosylation in binding to SARS-CoV-2 spike. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2100425118 (2021).

Menon, M. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of the human retina identifies cell types associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Commun. 10, 4902 (2019).

Burke, D. F. et al. Towards a structurally resolved human protein interaction network. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 216–225 (2023).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Drake, Z. C., Seffernick, J. T. & Lindert, S. Protein complex prediction using Rosetta, AlphaFold, and mass spectrometry covalent labeling. bioRxivhttps://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.30.490108 (2022).

Glasgow, A. et al. Engineered ACE2 receptor traps potently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28046–28055 (2020).

Renzi, F. et al. Engineering an ACE2-derived fragment as a decoy for novel SARS-CoV-2 virus. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 6, 857–867 (2023).

Harmalkar, A., Lyskov, S. & Gray, J. J. Reliable protein-protein docking with AlphaFold, Rosetta, and replica exchange. Elife 13, RP94029 (2025).

Kamal, M. S., Dey, N., Chowdhury, L., Hasan, S. I. & Santosh, K. C. Explainable AI for glaucoma prediction analysis to understand risk factors in treatment planning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 71, 1–9 (2022).

Novielli, P. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence for microbiome data analysis in colorectal cancer biomarker identification. Front Microbiol 15, 1348974 (2024).

Serebrinsky-Duek, K., Barra, M., Danino, T. & Garrido, D. Engineered bacteria for short-chain-fatty-acid-repressed expression of biotherapeutic molecules. Microbiol Spectr. 11, e0004923 (2023).

Cubillos-Ruiz, A. et al. Engineering living therapeutics with synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 941–960 (2021).

Hsu, B. B. et al. In situ reprogramming of gut bacteria by oral delivery. Nat. Commun. 11, 5030 (2020).

Verma, A. et al. Expression of human ACE2 in Lactobacillus and beneficial effects in diabetic retinopathy in mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 14, 161–170 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003).

Gheblawi, M. et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res 126, 1456–1474 (2020).

Kim, T. H., Cho, B. K. & Lee, D.-H. Synthetic biology-driven microbial therapeutics for disease treatment. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34, 1947–1958 (2024).

Galvan, S., Teixeira, A. P. & Fussenegger, M. Enhancing cell-based therapies with synthetic gene circuits responsive to molecular stimuli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 121, 2987–3000 (2024).

Krawczyk, K. et al. Electrogenetic cellular insulin release for real-time glycemic control in type 1 diabetic mice. Science 368, 993–1001 (2020).

Ye, H. et al. Self-adjusting synthetic gene circuit for correcting insulin resistance. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0005 (2017).

Xie, L. et al. Glucose-activated switch regulating insulin analog secretion enables long-term precise glucose control in mice with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 72, 703–714 (2023).

Barra, M., Danino, T. & Garrido, D. Engineered probiotics for detection and treatment of inflammatory intestinal diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 265 (2020).

Mayorga-Ramos, A., Zúñiga-Miranda, J., Carrera-Pacheco, S. E., Barba-Ostria, C. & Guamán, L. P. CRISPR-Cas-based antimicrobials: Design, challenges, and bacterial mechanisms of resistance. ACS Infect. Dis. 9, 1283–1302 (2023).

Jiang, J.-N., Kong, F.-H., Lei, Q. & Zhang, X.-Z. Surface-functionalized bacteria: Frontier explorations in next-generation live biotherapeutics. Biomaterials 317, 123029 (2025).

Ates, A., Tastan, C. & Ermertcan, S. Precision genome editing unveils a breakthrough in reversing antibiotic resistance: CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of multi-drug resistance genes in methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.31.573511 (2024).

Yi, Q., Ouyang, X., Zhu, G. & Zhong, J. Letter: The risk-benefit balance of CRISPR-Cas screening systems in gene editing and targeted cancer therapy. J. Transl. Med. 22, 1005 (2024).

Parada Venegas, D. et al. Corrigendum: Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol. 10, 1486 (2019).

Scott, S. A., Fu, J. & Chang, P. V. Microbial tryptophan metabolites regulate gut barrier function via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 19376–19387 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Programmable probiotics modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment after effective oral delivery. Nat. Commun. 13, 3432 (2022).

Wang, X. Microencapsulating alginate-based polymers for probiotics delivery systems and their application. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 15, 644 (2022).

Oh, J.-H. et al. Secretion of recombinant interleukin-22 by engineered lactobacillus reuteri reduces fatty liver disease in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. mSphere https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00183-20 (2020).

Noguès, E. B. et al. Lactococcus lactis engineered to deliver hCAP18 cDNA alleviates DNBS-induced colitis in C57BL/6 mice by promoting IL17A and IL10 cytokine expression. Sci. Rep. 12, 15641 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Correction to: Engineered probiotics. Microb. Cell Fact. 21, 1–1 (2022).

Weibel, N. et al. Engineering a novel probiotic toolkit in for sensing and mitigating gut inflammatory diseases. ACS Synth. Biol. 13, 2376–2390 (2024).

Prasad, R. et al. Maintenance of enteral ACE2 prevents diabetic retinopathy in type 1 diabetes. Circ. Res. 132, e1–e21 (2023).

Paul, S. et al. An engineered probiotic expressing Ang1-7 minimizes the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy in db/db mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 323–323 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiome contributes to glaucoma pathogenesis. MedComm - Fut. Med. 1, e28 (2022).

Li, M., Chen, W.-D. & Wang, Y.-D. The roles of the gut microbiota-miRNA interaction in the host pathophysiology. Mol. Med. 26, 101 (2020).

Fardi, F. et al. An interplay between non-coding RNAs and gut microbiota in human health. Diab. Res. Clin. Pract. 201, 110739 (2023).

Lun, D. S. et al. Large-scale identification of genetic design strategies using local search. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 296 (2009).

Gu, D., Zhang, C., Zhou, S., Wei, L. & Hua, Q. IdealKnock: A framework for efficiently identifying knockout strategies leading to targeted overproduction. Comput Biol. Chem. 61, 229–237 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. Improving pathway prediction accuracy of constraints-based metabolic network models by treating enzymes as microcompartments. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 8, 597–605 (2023).

Reimers, A.-M., Knoop, H., Bockmayr, A. & Steuer, R. Cellular trade-offs and optimal resource allocation during cyanobacterial diurnal growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 114, E6457–E6465 (2017).

Reimers, A.-M., Lindhorst, H. & Waldherr, S. A Protocol for Generating and Exchanging (Genome-Scale) Metabolic Resource Allocation Models. Metabolites 7, 47 (2017).

Oyarzún, D. A. & Stan, G.-B. V. Synthetic gene circuits for metabolic control: design trade-offs and constraints. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20120671 (2013).

Watanabe, L. et al. iBioSim 3: A tool for model-based genetic circuit design. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1560–1563 (2019).

Paklao, T., Suratanee, A. & Plaimas, K. ICON-GEMs: Integration of co-expression network in genome-scale metabolic models, shedding light through systems biology. BMC Bioinforma. 24, 492 (2023).

Jensen, P. A., Lutz, K. A. & Papin, J. A. TIGER: Toolbox for integrating genome-scale metabolic models, expression data, and transcriptional regulatory networks. BMC Syst. Biol. 5, 147 (2011).

Xu, X. et al. The gut metagenomics and metabolomics signature in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Pathog. 14, 26 (2022).

Heinken, A., Hertel, J. & Thiele, I. Metabolic modelling reveals broad changes in gut microbial metabolism in inflammatory bowel disease patients with dysbiosis. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 7, 19 (2021).

Patumcharoenpol, P. et al. MetGEMs Toolbox: Metagenome-scale models as integrative toolbox for uncovering metabolic functions and routes of human gut microbiome. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008487 (2021).

Bidkhori, G. & Shoaie, S. MIGRENE: The toolbox for microbial and individualized GEMs, reactobiome and community network modelling. Metabolites 14, 132 (2024).

Yao, Y., Wang, H. & Liu, Z. Expression of ACE2 in airways: Implication for COVID-19 risk and disease management in patients with chronic inflammatory respiratory diseases. Clin. Exp. Allergy 50, 1313–1324 (2020).

Nascimento Conde, J., Schutt, W. R., Gorbunova, E. E. & Mackow, E. R. Recombinant ACE2 expression is required for SARS-CoV-2 to infect primary human endothelial cells and induce inflammatory and procoagulative responses. MBio 11, 10–1128 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Digestive symptoms of COVID-19 and expression of ACE2 in digestive tract organs. Cell Death Discov. 6, 76 (2020).

Toyonaga, T. et al. Increased colonic expression of ACE2 associates with poor prognosis in Crohn’s disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 13533 (2021).

Puurunen, M. K. et al. Safety and pharmacodynamics of an engineered E. coli Nissle for the treatment of phenylketonuria: A first-in-human phase 1/2a study. Nat. Metab. 3, 1125–1132 (2021).

Microbiome Therapeutics Innovation Group & Barberio, D. Navigating regulatory and analytical challenges in live biotherapeutic product development and manufacturing. Front. Microbiomes 3, 1441290 (2024).

Dreher-Lesnick, S. M., Stibitz, S. & Carlson, P. E. U.S. regulatory considerations for development of live biotherapeutic products as drugs. Microbiol Spectr 5, 10–1128 (2017).

Cordaillat-Simmons, M., Rouanet, A. & Pot, B. Live biotherapeutic products: The importance of a defined regulatory framework. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 1397–1406 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.D., F.M., and M.M. conceived the idea for the review and outlined the structure. J.A.D. and F.M. conducted the literature search and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. J.A.D., A.T., and F.M. critically revised the manuscript and updated it. All authors (J.A.D., F.M., A.T., and M.M.) contributed to the writing, reviewed the final draft, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aminian-Dehkordi, J., Montazeri, F., Tamadon, A. et al. Systems biology and microbiome innovations for personalized diabetic retinopathy management. npj Syst Biol Appl 11, 133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00607-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00607-w

This article is cited by

-

SIMBA-GNN: mechanistic graph learning for microbiome prediction

npj Systems Biology and Applications (2025)