Abstract

A two-decade-long accumulation of freshwater in the Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre has recently started to be released. Here we use satellite observations and model simulations to show that changes in wind regimes and sea ice declines are causing freshwater to accumulate close to the export gateways to the North Atlantic. This emerging buffer zone plays an important role in modulating the propagation of freshwater into the subpolar North Atlantic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Arctic Ocean is one of the major freshwater reservoirs of the climate system and an important component of the hydrological cycle of the Northern Hemisphere1,2. It is fed by river runoff from land, precipitation from the atmosphere and Pacific water with relatively low salinity3. In a warming climate, these freshwater sources are increasing, with the addition of ice melt water4. The Arctic freshwater is ultimately exported to the subpolar North Atlantic (SPNA) via the Fram and Davis straits. Changes in Arctic freshwater export can influence the ocean stratification and dense water formation in the SPNA, thus impacting the large-scale Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and the climate5,6.

Great Salinity Anomalies of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, featuring low-salinity pulses propagating in the SPNA, were induced or enhanced by freshwater export from the Arctic Ocean7,8, although wind-driven ocean circulation changes in the North Atlantic can also lead to large-scale salinity anomalies in the SPNA9. An intense Great Salinity Anomaly can lead to the shutdown of deep convection in the Labrador Sea10. Furthermore, it was suggested that the Atlantic overturning circulation is more sensitive to changes in Arctic freshwater export and precipitation than it is to Greenland melt water11.

The Arctic Ocean is known to have accumulated an unprecedented amount of liquid freshwater in the 2000s and 2010s, with most of it stored in the Beaufort Gyre region12,13. This freshwater accumulation was not only due to unusual anti-cyclonic winds in the western Arctic, which helped converge surface freshwater into the Beaufort Gyre; it was also related to the strong sea ice decline, which supplied additional melt water and intensified the Ekman transport of freshwater towards the Beaufort Gyre region14.

Here, we use a combination of satellite observations and model simulations to show that the Arctic Ocean freshwater system entered a new state recently. While the Beaufort Gyre was releasing freshwater, a buffer zone north of Greenland was accumulating freshwater. Our results suggest that this buffer zone plays a crucial role in modulating the propagation of Arctic low-salinity anomalies to the SPNA.

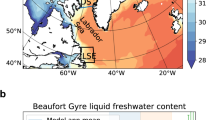

The Beaufort Gyre experienced three major changes since the beginning of the twenty-first century. First, from 2004 to 2009, its freshwater content (FWC) increased rapidly (Fig. 1a,d)15,16,17. This increase was accompanied by a westward expansion of its spatial extent18. This period was characterized by a strong anti-cyclonic atmospheric circulation anomaly over the Canada Basin (Extended Data Fig. 1a), which was associated with higher than normal Beaufort High sea level pressure (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Along with effects of Arctic sea ice decline, which increases both the availability of freshwater and ocean surface stress, this anti-cyclonic wind anomaly increased the FWC of the Beaufort Gyre, causing a spin-up of the gyre’s circulation (Extended Data Fig. 2)14.

a–c, FWC anomaly in 2009 (a), 2019 (b) and 2022 (c) relative to the climatological mean over 1980–2004 in the FESOM simulation. d,e, Time series of FWC anomaly relative to the climatological mean in the Beaufort Gyre region (d) and buffer zone (e) in the FESOM simulation. The hydrography-based FWC anomaly in the Beaufort Gyre region, provided in refs. 12,13, is presented as mean values ± one standard deviation (error bars) in d. The uncertainty of satellite-based estimates in d is about ±3.9%, as provided in ref. 12. The Beaufort Gyre region and buffer zone are indicated in a–c with black and magenta lines, respectively. Other main geographic areas mentioned in the text are labelled in c: EEB, eastern Eurasian Basin; MB, Makarov Basin; WCB, western Canada Basin; FS, Fram Strait; DS, Davis Strait.

The second major change in the Beaufort Gyre occurred between 2014 and 2019 (Fig. 1d). In this period, the total FWC in the Beaufort Gyre further increased, but the increase was confined to the eastern part of the gyre; the western part actually experienced a reduction in FWC (Extended Data Fig. 3). This effectively caused a shrinkage of the Beaufort Gyre in the zonal direction14,19,20. This simultaneous increase in FWC and reduction in zonal extent of the gyre can be explained by the anomalous atmospheric circulation in the Arctic (Extended Data Fig. 3b). The Arctic sea level pressure was slightly above climatology in the southeastern Canada Basin and anomalously low elsewhere. This led to an anti-cyclonic wind anomaly over the southeastern Canada Basin (Extended Data Fig. 1a), causing the accumulation of freshwater in this region.

The third, transformative change in the Beaufort Gyre commenced around 2019. Not only has the zonal extent of the gyre continued to shrink (comparing Fig. 1b,c), the total FWC of the gyre also started decreasing (Fig. 1d). Both satellite observations and model simulations consistently reveal a reduction in sea surface height in the central Beaufort Gyre from 2019 to 2022 (Fig. 2a,c), in response to the reduction in FWC (Fig. 2d). The latter can be explained by the negative sea level pressure anomaly (Fig. 2b) and, thus, the positive wind curl anomaly over the Canada Basin (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

a, The change in dynamic ocean topography (DOT) obtained from satellite observations23. b, The sea level pressure (SLP) anomaly in 2019–2022 relative to the long-term mean of 1980–2022. c, The simulated sea surface height (SSH) change. d, The simulated FWC change.

The contraction and spin-up of the Beaufort Gyre between 2014 and 2019 were accompanied by a reduction in FWC in the eastern Eurasian Basin and Makarov Basin (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 3d). Between 2019 and 2022, the area with lower than normal FWC extended further eastwards into the western Canada Basin (Fig. 1c). The large-scale ocean circulation in the Arctic alternates between cyclonic and anti-cyclonic regimes on subdecadal time scales, mainly associated with the phase change of the Arctic Oscillation21,22. The eastward extension of negative FWC anomalies suggests a recent intensification of the Arctic Ocean cyclonic circulation mode23. This intensification is attributed to the predominantly positive phase of the Arctic Oscillation since the mid-2010s (Extended Data Fig. 1b) and increased ocean surface stress resulting from sea ice decline14. The concurrent contraction of the Beaufort Gyre and the strengthening of the cyclonic circulation can also facilitate the propagation of water of Atlantic origin towards the Canada Basin24,25.

During the rapid inflation of the Beaufort Gyre before 2009, the FWC in the region north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Greenland did not change much (Fig. 1a). However, after 2009, as the Beaufort Gyre contracted eastwards, this region began accumulating freshwater released from the Beaufort Gyre (Fig. 1b,c). Due to its ability to accumulate freshwater over time (Fig. 1e), this area is referred to as a freshwater ‘buffer zone’. Notably, the dynamic ocean topography from satellite observations shows a marked increase in the buffer zone between 2019 and 2022 (Fig. 2a). This trend is consistently reproduced in simulated sea surface height (Fig. 2c), corroborating the notion of a corresponding rise in FWC (Fig. 2d).

The buffer zone not only serves as a conduit for Beaufort Gyre freshwater but also modulates the time it takes for the freshwater to exit the Arctic Ocean, a process influenced by wind conditions. To better understand this, we conducted a wind-perturbation simulation in which the anti-cyclonic wind anomaly—associated with the positive sea level pressure anomaly in the central Arctic during 2019–2022—was changed to a cyclonic pattern (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). The model results indicate that, under cyclonic wind conditions, freshwater released from the Beaufort Gyre is exported more rapidly through the buffer zone and subsequently through the Arctic gateways (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e). Thus, the buffer zone can delay the propagation of freshwater from the Beaufort Gyre to the SPNA under certain wind conditions, such as those observed in 2019–2022. Moreover, the ongoing decline in Arctic sea ice can enhance ocean surface stress and Ekman transport, potentially amplifying the influence of winds on freshwater accumulation and release in the Arctic Ocean26.

By 2022, the Beaufort Gyre’s anomalous FWC has decreased to approximately 4,000 km3, while the buffer zone has accumulated around 3,000 km3 anomalous freshwater (Fig. 1d,e). Different from the freshwater stored in the Beaufort Gyre, the anomalous freshwater in the buffer zone is situated in close proximity to the Arctic export gateways. Previous modelling studies have offered a quantitative assessment of the potential impact of releasing Beaufort Gyre freshwater on downstream salinity. It was demonstrated that releasing 5,600 km3 freshwater over a 13-year period through Davis Strait could reduce upper-200-m salinity by 0.2–0.4 along the Baffin Island Current and Labrador Current27. Therefore, the current total anomalous freshwater in the buffer zone and eastern Beaufort Gyre, distributed just behind the doors leading to the SPNA, has the potential to trigger notable salinity anomalies upon eventual release. The distribution of freshwater export between the two Arctic gateways (east and west of Greenland) can be influenced by atmospheric forcing both inside and outside the Arctic4.

In conclusion, we found that the Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre has started to release freshwater after accumulating it for an unusually prolonged period, while a buffer zone situated close to the Arctic export gateways has shown an emerging ability to accumulate freshwater. With the contraction of the Beaufort Gyre and the strengthening of the cyclonic circulation mode of the Arctic Ocean, anomalous freshwater has shifted into this buffer zone. The propagation of the Arctic freshwater anomaly to the North Atlantic was delayed in the buffer zone under the recent wind conditions. Given the anticipated increase in the ocean’s sensitivity to winds due to sea ice decline, the role of the buffer zone in modulating the propagation of freshwater to the North Atlantic warrants greater attention.

Methods

Model simulations

We employed the global Finite Element Sea-ice Ocean Model (FESOM)28,29. The model is based on unstructured meshes, thus allowing to use variable horizontal resolution. The setup used here has a horizontal resolution of 4.5 km in the Arctic Ocean, 24 km in the SPNA and about nominal one degree in the rest of the global ocean. In the vertical, the grid spacing is 10 m in the upper 100 m and then coarsened with depth. The model was initialized from the Polar science center Hydrographic Climatology version 3 (ref. 30) and run from 1958 to 2022 forced by the surface-atmospheric dataset JRA55-do, which is based on the Japanese 55-year atmospheric reanalysis31. The model has been used in studies on Arctic freshwater32, sea ice33 and Arctic gateway transports4,34. As shown in the model assessment in these studies, the model can reasonably reproduce observed trends and variability in Arctic sea ice extent and ocean temperature and salinity. In particular, the observed changes in the Beaufort Gyre FWC over the past two decades were reasonably reproduced in the model, with some underestimation in the magnitudes of the changes (Fig. 1d).

Besides the historical control simulation described above, we performed a wind-perturbation simulation. On average, the atmospheric circulation in the central Arctic was in an anti-cyclonic regime in the period 2019–2022 (Extended Data Fig. 4a). To reveal the role of this wind condition in trapping the freshwater released from the Beaufort Gyre, in the wind-perturbation simulation we added a cyclonic wind perturbation north of 79° N to the wind forcing so that the wind condition in the central Arctic is changed to a cyclonic regime (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). A dye tracer with value 1 is injected in the Beaufort Gyre region (the area indicated by the black box in Fig. 1a) in the upper 100 m at the beginning of 2019. The dye tracer experiences the same advection and diffusion processes as salinity during model simulations. The spatial distribution of the dye tracer at the end of the simulations shows that the freshwater originating from the Beaufort Gyre leaves the buffer zone and propagates through the Arctic gateways more rapidly in the wind-perturbation simulation than in the control simulation (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e). At the end of the simulations, the buffer zone contains 25% more dye tracer in the control simulation compared with the wind-perturbation simulation. In the wind-perturbation simulation, this portion of the dye tracer has exited the Arctic Ocean. Therefore, the buffer zone can influence the time it takes for the Arctic fresh, cold surface water to transit into the North Atlantic.

Observational dataset

Dynamic ocean topography (physically equivalent to sea surface height in ocean model simulations) from satellite altimetry measurements was employed to investigate Arctic Ocean changes in different periods, including the gridded dynamic ocean topography product for the period of 2004–2019 derived from Envisat and CryoSat-2 data35 and that for the period of 2019–2022 derived from ICESat-2 data36. The product derived from ICESat-2 was not smoothed as strongly as that derived from Envisat and CryoSat-2, so some fingerprints of satellite tracks and missing data are visible in the plot of dynamic ocean topography anomaly (Fig. 2a).

FWC in the Beaufort Gyre was estimated from both hydrography observations (2003–2018) and satellite-derived dynamic ocean topography (2004–2014) in previous studies12. With the recent update13, the estimate based on hydrography observations now covers the period of 2003–2021. These observational estimates together with model results are used to illustrate the changes in Beaufort Gyre FWC over the past two decades.

In the Arctic deep basin, changes in steric sea level are primarily attributed to variations in the halosteric component. Changes in FWC, which is a measure of vertically integrated salinity signal, are thus correlated with variations in sea surface height16,17,35. Consequently, satellite altimeter data can be interpreted as a metric for assessing FWC in the Arctic basin. Over continental shelf, mass changes may play a relatively large role, so changes in sea surface height have less correspondence with changes in FWC.

Definition of FWC

We define vertically integrated FWC (in metres) within a water column as

where S represents ocean salinity, Sref is the reference salinity, which is set to the mean salinity of the Arctic Ocean (34.8)37, D represents the depth of the 34.8 isohaline and z represents the vertical coordinate. By integrating the vertically integrated FWC over an area, one obtains the volumetric FWC (in cubic metres).

The FWC in a column means the amount of pure water that can be taken out so that the mean salinity of the column becomes the reference salinity. Using a different reference salinity, such as a value representing the upper ocean salinity of the SPNA, would result in a different mean value of the FWC. However, the temporal change of FWC as we focus on in this study does not change much when a different reference salinity is used. In particular, both the observational estimates12,13 and our model results use the same reference salinity. As depicted in Fig. 1d, they consistently show the temporal changes in the Beaufort Gyre FWC.

Data availability

The model data used in Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Figs. 1–4 are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10409535 (ref. 38). The dynamic ocean topography data are available at http://www.cpom.ucl.ac.uk/dynamic_topography/ (ref. 35) and https://nsidc.org/ (ref. 36). Observational estimates for the FWC are from refs. 12,13. The Arctic Oscillation index is available at https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/.

References

Peterson, B. J. et al. Trajectory shifts in the Arctic and Subarctic freshwater cycle. Science 313, 1061–1066 (2006).

Carmack, E. et al. Freshwater and its role in the Arctic Marine System: sources, disposition, storage, export, and physical and biogeochemical consequences in the Arctic and global oceans. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 121, 675–717 (2016).

Serreze, M. C. et al. The large-scale freshwater cycle of the Arctic. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 111, C11010 (2006).

Wang, Q. et al. A review of Arctic–Subarctic ocean linkages: past changes, mechanisms, and future projections. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0013 (2023).

Weijer, W. et al. Stability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: a review and synthesis. J. Geophy. Res. Oceans 124, 5336–5375 (2019).

Haine, T. W. N., Siddiqui, A. H. & Jiang, W. Arctic freshwater impact on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation: status and prospects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 381, 20220185 (2023).

Dickson, R., Meincke, J., Malmberg, S. & Lee, A. J. The Great Salinity Anomaly in the Northern North-Atlantic 1968–1982. Prog. Oceanogr. 20, 103–151 (1988).

Belkin, I. M. Propagation of the ‘Great Salinity Anomaly’ of the 1990s around the northern North Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L08306 (2004).

Holliday, N. P. et al. Ocean circulation causes the largest freshening event for 120 years in eastern subpolar North Atlantic. Nat. Commun. 11, 585 (2020).

Gelderloos, R., Straneo, F. & Katsman, C. A. Mechanisms behind the temporary shutdown of deep convection in the Labrador Sea: lessons from the Great Salinity Anomaly years 1968–71. J. Clim. 25, 6743–6755 (2012).

Le Bras, I. et al. How much Arctic fresh water participates in the subpolar overturning circulation? J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 955–973 (2021).

Proshutinsky, A. et al. Analysis of the Beaufort Gyre freshwater content in 2003–2018. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 9658–9689 (2019).

Timmermans, M.-L. & Toole, J. M. The Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 223–248 (2023).

Wang, Q. & Danilov, S. A synthesis of the upper Arctic Ocean circulation during 2000–2019: understanding the roles of wind forcing and sea ice decline. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 863204 (2022).

McPhee, M. G., Proshutinsky, A., Morison, J. H., Steele, M. & Alkire, M. B. Rapid change in freshwater content of the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L10602 (2009).

Giles, K. A., Laxon, S. W., Ridout, A. L., Wingham, D. J. & Bacon, S. Western Arctic Ocean freshwater storage increased by wind-driven spin-up of the Beaufort Gyre. Nat. Geosci. 5, 194–197 (2012).

Morison, J. et al. Changing Arctic Ocean freshwater pathways. Nature 481, 66–70 (2012).

Regan, H. C., Lique, C. & Armitage, T. W. K. The Beaufort Gyre extent, shape, and location between 2003 and 2014 from satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 844–862 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Biophysical consequences of a relaxing Beaufort Gyre. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085990 (2020).

Lin, P. et al. Recent state transition of the Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre. Nat. Geosci. 16, 485–491 (2023).

Proshutinsky, A. & Johnson, M. Two circulation regimes of the wind-driven Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 12493–12514 (1997).

Thompson, D. W. J. & Wallace, J. M. The Arctic Oscillation signature in the wintertime geopotential height and temperature fields. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 1297–1300 (1998).

Morison, J. et al. The cyclonic mode of Arctic Ocean circulation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 1053–1075 (2021).

Steele, M. & Boyd, T. Retreat of the cold halocline layer in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 103, 10419–10435 (1998).

Nishino, S. et al. Atlantic-origin water extension into the Pacific Arctic induced an anomalous biogeochemical event. Nat. Commun. 14, 6235 (2023).

Wang, Q. Stronger variability in the Arctic Ocean induced by sea ice decline in a warming climate: freshwater storage, dynamic sea level and surface circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2020JC016886 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Labrador Sea freshening linked to Beaufort Gyre freshwater release. Nat. Commun. 12, 1229 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. The Finite Element Sea Ice-Ocean Model (FESOM) v.1.4: formulation of an ocean general circulation model. Geosci. Model Dev. 7, 663–693 (2014).

Danilov, S. et al. Finite-Element Sea Ice Model (FESIM), version 2. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 1747–1761 (2015).

Steele, M., Morley, R. & Ermold, W. Phc: a global ocean hydrography with a high quality Arctic Ocean. J. Clim. 14, 2079–2087 (2001).

Tsujino, H. et al. JRA-55 based surface dataset for driving ocean–sea-ice models (JRA55-do). Ocean Modell. 130, 79–139 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Arctic sea ice decline significantly contributed to the unprecedented liquid freshwater accumulation in the Beaufort Gyre of the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4956–4964 (2018).

Wang, Q., Ricker, R. & Mu, L. Arctic sea ice decline preconditions events of anomalously low sea ice volume export through Fram Strait in the early 21st century. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, e2020JC016607 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Intensification of the Atlantic Water supply to the Arctic Ocean through Fram Strait induced by Arctic sea ice decline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086682 (2020).

Armitage, T. et al. Arctic sea surface height variability and change from satellite radar altimetry and GRACE, 2003–2014. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 4303–4322 (2016).

Morison, J., Hancock, D., Dickinson, S., Robbins, J. & Roberts, L. ATLAS/ICESat-2 L3B Monthly 3-Month Gridded Dynamic Ocean Topography, Version 1 (NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center, 2023).

Aagaard, K. & Carmack, E. C. The role of sea ice and other fresh-water in the Arctic circulation. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 14485–14498 (1989).

Wang, Q. FESOM model data used in the study on the buffer zone for great salinity anomaly. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10409535 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) within the EPICA project with grant no. 03F0889A (Q.W.) and by the AWI INSPIRES programme (Q.W.).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alfred-Wegener-Institut.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. conceived the study, performed and analysed the simulations, and wrote the first paper draft. S.D. and T.J. contributed to the interpretation of the results and improving the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks John Toole and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: James Super, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

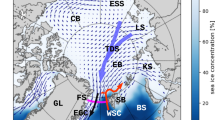

Extended Data Fig. 1 Climate indices.

a, Normalized wind curl over the Canada Basin. b, Arctic Oscillation index.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Changes in the Arctic Ocean from 2004 to 2009.

a, Change in dynamic ocean topography (DOT) obtained from satellite observations. b, Sea level pressure (SLP) anomaly in 2004-2009 relative to the long-term mean of 1980-2022. c, Simulated sea surface height (SSH) change. d, Simulated freshwater content (FWC) change.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Changes in the Arctic Ocean from 2014 to 2019.

a, Change in dynamic ocean topography (DOT) obtained from satellite observations. b, Sea level pressure (SLP) anomaly in 2014-2019 relative to the long-term mean of 1980-2022. c, Simulated sea surface height (SSH) change. d, Simulated freshwater content (FWC) change.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Accumulation of freshwater in the buffer zone influenced by wind conditions.

a, Sea level pressure (SLP) anomaly in 2019-2022 relative to the long-term mean of 1980-2022. b, SLP anomaly in 2019-2022 in case the perturbation shown in (c) is added, that is, (b) is obtained by adding (c) to (a) in the area indicated by the black circles. c, A negative SLP perturbation. The wind perturbation associated with this SLP perturbation (shown by arrows) is used in the perturbation simulation to reveal the impacts of winds on the ocean. d, Beaufort Gyre dye tracer at the end of 2022 in the historical control simulation, which corresponds to the atmospheric circulation condition in (a). e, The same as (d), but for the wind-perturbation simulation, which corresponds to the atmospheric circulation condition in (b).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Danilov, S. & Jung, T. Arctic freshwater anomaly transiting to the North Atlantic delayed within a buffer zone. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1218–1221 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01592-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01592-1

This article is cited by

-

Dominant inflation of the Arctic Ocean’s Beaufort Gyre in a warming climate

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Overview of the studies on the interactions between atmosphere, sea ice, and ocean in the Arctic Ocean and its climatic effects: contributions from Chinese scientists

Acta Oceanologica Sinica (2025)