Abstract

Melioidosis is a life-threatening tropical disease caused by an intracellular gram-negative bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. B. pseudomallei polymerizes the host cell actin through autotransporters, BimA, and BimC, to facilitate intracellular motility. Two variations of BimA in B. pseudomallei have been reported previously: BimABp and BimA B. mallei-like (BimABm). However, little is known about genetic sequence variations within BimA and BimC, and their potential effect on the virulence of B. pseudomallei. This study analyzed 1,294 genomes from clinical isolates of patients admitted to nine hospitals in northeast Thailand between 2015 and 2018 and performed 3D structural analysis and plaque-forming efficiency assay. The genomic analysis identified 10 BimABp and 5 major BimC types, in the dominant and non-dominant lineages of the B. pseudomallei population structure. Our protein prediction analysis of all BimABp and major BimC variants revealed that their 3D structures were conserved compared to those of B. pseudomallei K96243. Sixteen representative strains of the most distant BimABp types were tested for plaque formation and the development of polar actin tails in A549 epithelial cells. We found that all isolates retained these functions. These findings enhance our understanding of the prevalence of BimABp and BimC variants and their implications for B. pseudomallei virulence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Burkholderia pseudomallei is the causative agent of melioidosis. It is a gram-negative intracellular soil-dwelling bacterium1 isolated from various soil and water sources in Thailand, Australia, and other tropical countries2,3. Routes of infection include direct aerosol inhalation, ingestion, and percutaneous inoculation4. Melioidosis has various clinical manifestations ranging from acute infections with pneumonia, sepsis, and disseminated internal abscess to localized and neurological infections5,6. The prevalence of melioidosis in Southeast Asia ranges from 0.02% to 74.4%, while the disease is estimated to affect 165,000 people worldwide of which 89,000 are fatalities7,8. Moreover, the fatality rate of melioidosis reaches 35%–40% in northeast Thailand8,9 and 10% in northern Australia10. The treatment regimen for melioidosis includes ceftazidime and meropenem for the initial parenteral phase, while trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole) is administered orally during the eradication phase11. B. pseudomallei is classified as a tier 1 select biological agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, posing a severe threat to both humans and animals12,13. Currently, licensed melioidosis vaccines and better treatment approaches are unavailable.

B. pseudomallei can invade and replicate inside phagocytic and nonphagocytic mammalian cells14. B. pseudomallei employs various virulence factors, such as Bsa (T3SS-3), to escape from vacuoles and survive in the cytoplasm15. When B. pseudomallei is inside the cytosol, it utilizes a motility factor, BimA16 and mimics the host cell actin nucleator, Ena/VASP, to polymerize actin, drives actin-based motility, and initiates host cell fusion17. BimA is a member of the trimeric autotransporter family and homologous to YadA of Yersinia enterocolitica18. BimA can induce actin-based membrane protrusions by polar nucleation16,19,20. When the protrusions connect with a neighboring cell, B. pseudomallei moves from one cell to another, spreads intracellularly, and fuses with neighboring cells, leading to form multinucleated giant cells (MNGCs) and plaques19. BimA is involved in the replication and intercellular spread of B. pseudomallei in many cell types, including epithelial19, macrophage-like21, and neuroblastoma22 cells. BimA is present in B. pseudomallei and closely related species, B. mallei and B. thailandensis23. B. mallei causes glanders, which primarily affects animals and can also infect humans. It is a clonal descendant of B. pseudomallei, having undergone genome reduction24,25. Although B. thailandensis is usually nonpathogenic to humans and animals, it has occasionally been isolated from humans and observed to be virulent in an insect model26,27,28. BimA of B. mallei and B. thailandensis can compensate for the actin-based motility function of the bimA knock-out mutant of B. pseudomallei29. There are two known types of BimA in B. pseudomallei: the typical BimA B. pseudomallei (BimABp) and the BimA B. mallei-like variation (BimABm). BimABm is 54% identical to the BimA of B. pseudomallei K96243 (BimABp) and 95% identical to B. mallei ATCC 23344, respectively23. Studies have reported the BimABm variants in Australian and South Asian isolates are associated with neurological melioidosis30,31,32. In an Australian study, 26% of 76 clinical isolates harbored BimABm, which was also linked to meropenem resistance and had a truncated bimC gene32. The BimABm variant was observed in 4.5% and 18.5% of the isolates in India and Sri Lanka, respectively30,31; however, none were observed in 4 and 99 isolates of B. pseudomallei from Malaysia and Thailand, respectively23,33. In a murine melioidosis model, the BimABm variant was more virulent when delivered intranasally and subcutaneously and persisted longer within the phagocytic cells compared to BimABp34.

BimC, located upstream of bimA in B. pseudomallei chromosome 2, is involved in actin-based motility, MNGC formation, and plaque formation21. BimC is a member of the bacterial autotransporter heptosyltransferase (BAHT) family35 and shares sequence homology with TibC from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli36. BimC of B. thailandensis directly interacts with the transmembrane domain of BimA to confer polar targeting of BimA through the iron-finger motif formed by the four cysteine residues of BimC (C371, C374, C390, and C402)37. However, Srinon et al. previously described a polar expression of BimA in B. pseudomallei even after bimC deletion21.

Although variations in BimA have been studied across Australia and South Asia, particularly the BimABm variant and its potential implications for virulence, it is necessary to explore novel sequence variations within BimA and BimC and their potential impact on B. pseudomallei virulence, especially in hyperendemic regions, such as northeast Thailand and its neighboring countries. In this study, we performed a genomic analysis to identify novel variations in BimA and BimC. Our genomic study analyzed 1,294 clinical isolates of B. pseudomallei collected from patients with melioidosis prospectively recruited into a cohort study conducted at nine hospitals in northeast Thailand. We then constructed three-dimensional (3D) structural models to predict whether these variations alter the structures of BimA and BimC proteins. Furthermore, we conducted assays to assess plaque-forming efficiency and performed immunostaining and confocal microscopy to investigate whether the identified BimA variants were associated with changes in the actin-based motility of B. pseudomallei.

Results

BimA and BimC are conserved in B. pseudomallei isolates in Thailand

In our 3-year prospective cohort study on melioidosis, known as the DORIM study, conducted in nine hospitals in northeast Thailand38, we collected 1,294 clinical isolates of B. pseudomallei. This study utilized whole genome sequencing data from the DORIM study39 to examine the genetic variations of bimA and bimC. Using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), we observed that only 1,195 isolates contained the full length of bimA nucleotide sequences, while all 1,294 isolates had complete bimC nucleotide sequences. This discrepancy arose due to limitations in the short-read sequencing method, which resulted in bimA gene fragmentation (Supplementary Data 1).

Among 1,195 isolates of B. pseudomallei, none carried the bimABm gene; however, all genomes carried bimABp, and variations were observed in this gene’s alleles. We then categorized BimABp into different types. Genetic variants containing synonymous mutations after amino acid translation and have 100% amino acid sequence identity compared to B. pseudomallei K96243, were categorized as BimABp type 1. Among all isolates with bimABp, nine BimABp types diverged from BimABp type 1 of B. pseudomallei K96243 (Figs. 1a and 2a and c; Table 1; Supplementary Data 3). Of the nine BimABp types 2–10, six types (BimABp types 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 10) possessed missense mutations compared to BimABp type 1, while the remaining three types (BimABp types 4, 6, and 9) had additional insertion sequences (Fig. 1a and Table 1). All the identified BimABp types shared 97−99% sequence identity with BimA of the B. pseudomallei K96243.

Alignment of the BimABp and BimC types identified in clinical B. pseudomallei isolates. (a) Alignment of B. pseudomallei BimABp types depicting the variations observed between types 1 and 10 compared to BimABm MSHR668 23 located at the bottom of the alignment. (b) Alignment of B. pseudomallei BimC types depicting the variations observed between types 1 and 5. B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW40.

Number of B. pseudomallei genomes and Pairwise Single Amino acid Polymorphism (SAP) of BimABp and BimC types in clinical B. pseudomallei isolates. (a) and (b) Heat maps for pairwise SAP distances between BimABp and BimC variants. The color and number correspond to the number of SAP distances between each variant type in reference to BimABp and BimC types 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain). (c) and (d) Number of B. pseudomallei genomes harboring the BimABp and BimC variant types.

The analysis of bimC, when compared to B. pseudomallei K96243, revealed only missense mutations and lacked insertions or deletions. Based on the missense mutations, we categorized bimC into five major types (BimC types 1–5) and 25 minor types (BimC types 6–30) (Figs. 1b and 2b and d; Table 1; Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 4). BimC type 1 and types 2–5 shared 100% and more than 99% sequence identity with BimC of the B. pseudomallei K96243, respectively (Table 1). The 3D structures of all BimABp and major BimC types were further characterized, and the representative isolates harboring the BimABp types 2, 4, 6 and 9 (most distant from BimABp type 1) and BimABp type 10 (carrying a missense mutation in the transmembrane domain) were selected further for plaque-forming efficiency assay. These selections aimed to predict BimA-based functions in the virulence of B. pseudomallei.

BimABp and BimC variants are specific to dominant B. pseudomallei lineages

The population structure of B. pseudomallei in northeast Thailand was outlined from 1,265 genomes in our recent study39. To investigate BimABp and BimC variants further, we incorporated 27 and 2 genomes from clinical isolates of Laos and Cambodian patients (Supplementary Data 1) into the existing 1,265 genomes. These patients were admitted to the study hospitals in Thailand38. Subsequently, we re-evaluated the population structure of the combined set of 1,294 genomes (Supplementary Data 1) using maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogeny and performed PopPUNK analysis. Consistent with our previous study39, our approach assigned 1,294 genomes into 101 lineages, which were classified into 3 dominant lineages (lineage 1, n = 317; lineage 2, n = 271; and lineage 3, n = 113), accounting for 54.2%, and 98 non-dominant lineages (lineages 4–101, n = 1–52), accounting for 45.8% (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Despite a limited number of isolates from Laos patients included in this study, B. pseudomallei from both Thailand and Laos displayed an inter-mixed pattern, as supported by the presentation of Laos (n = 14) in all three dominant lineages (Fig. 3). Moreover, our study revealed presentations of the dominant lineages, BimABp and BimC types in each year of sample collection, which spanned from 2015 to 2018.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenomic tree of 1,294 B. pseudomallei clinical isolates rooted on MSHR5619. The innermost ring (1) represents the PopPUNK lineages. The second (2) and middle (3) rings represent the BimABp and BimC variant types, respectively. The fourth (4) and outermost (5) rings represent the country sources based on patients’ home addresses and the year of sample collection, respectively. The tree scale indicates 0.01 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Our results in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S1 demonstrated that BimABp types 1 and 4 were likely associated with lineage 1 (type 1, 55%, P = < 0.0001; type 4, 37%, P = < 0.0001), while BimABp types 2 and 3 were likely specific to lineages 2 and 3, respectively (type 2, 83%; P = < 0.0001; type 3, 60%; P = < 0.0001). On the other hand, BimC type 1 was distributed across all lineages but was predominantly enriched in lineage 1 (90%; P = < 0.0001). The remaining BimC types 2–5 were present in lineages 2, 3, and in non-dominant lineages.

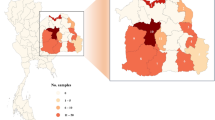

BimABp and BimC variants are dispersed across the endemic areas

We plotted the distribution of BimABp and BimC variants in northeast Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia using the longitudinal and latitudinal coordinates obtained from the patients’ residences (Fig. 4). Dominant lineages 1–3 were noted in patients from northeast Thailand and Laos, consistent with the ubiquitous dispersal of dominant lineages (Fig. 4b) as described by Seng et al.39. Associated with the dispersal of lineages 1–3, the dominant BimABp (BimABp types 1–4) and BimC (BimC types 1–3) types were also ubiquitously present across the studied regions (Fig. 4c-d).

Geographical distribution of B. pseudomallei clinical genomes. (a) Geographical map of northeast Thailand with study sites highlighted in gray. (b) Geographical distribution of the three dominant PopPUNK lineages. (c) Geographical distribution of the ten BimABp types. (d) Geographical distribution of the five BimC types. The spatial distribution of genomes was represented by the patients’ home addresses in Thailand, Laos and Cambodia.

3D structural analysis of BimABp types

We performed 3D structure modeling to predict the potential functional change of BimABp variants (Fig. 5). The amino acid sequences of BimA B. pseudomallei K96243 were retrieved from GenBank (Reference: CAH38965.1, locus tag: BPSS1492) and subjected to a BLAST search against Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org) to identify an appropriate template for homology modeling. However, despite efforts to enhance the search using the Phyre 2 protein threading method41, a reliable template could not be identified due to low sequence identity and coverage. To overcome this limitation, we utilized the I-TASSER de novo protein modeling method42 to generate our own model, resulting in a model with a confidence score of -0.96. To ensure the model’s quality, we performed YASARA energy minimization43 and validated it using the SAVES PROCHECK server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). The 3D structure of the model was then visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer software (Biovia v.21.1).

3D structural models of ten BimABptypes and BimABmof Australian strain MSHR668 of Burkholderia pseudomallei. (a) 3D structural model of BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain) as described by Stevens et al.16. The yellow-colored ribbon represents the predicted signal peptide (residues 1–53); green, NIPVPPPMPGGGA direct repeat (residues 63–75); violet, proline-rich motif (residues 78–84); pink, WH and WH2-like domains (residues 155–158); orange, PDASX repeats (residues 244–268); blue, transmembrane domain (residues 458–516). (b – j) 3D structural models of BimABp types 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. Mutation positions are represented in pink Corey-Pauling-Koltun (CPK) models and labeled accordingly. The red-colored ribbons represent the insertion. (k) 3D structural model of BimABm MSHR668 23. All BimABp and BimABm models were built using I-TASSER. The C-score of the models were: -0.96 for BimABp type 1; -1.16 for type 2; -0.71 for type 3; -0.74 for type 4; -0.99 for type 5; -0.73 for type 6; -1.02 for type 7; -1.12 for type 8; -1.13 for type 9; -0.71 for type 10; and -0.93 for BimABm MSHR668. Figures were generated by Discovery Studio Visualizer version 21.1.

BimA B. pseudomallei is a type Vc trimeric autotransporter whose structure contains a C-terminal autotransporter domain anchored to the membrane by forming a pore and an N-terminal passenger domain, which transports protein and is exposed to the bacterial surface44. In reference to BimABp type 1 of B. pseudomallei K96243 (Fig. 5a), the 3D structures of BimABp types 2–10 did not differ despite the presence of single amino acid polymorphisms (SAPs) and insertions (Fig. 5b–j). The mutations found in each BimABp type were listed in Table 1. Interestingly, BimABp types 9 and 10 have amino acid amino acid changes in the transmembrane domain (458–516), which was previously described as a site of BimC interaction in B. thailandensis, crucial for the polar localization of BimA37.

The 3D structure of BimABm has not been reported. Therefore, we constructed the 3D structural model of a BimABm of an Australian strain MSHR668 (GenBank Ref.: NZ_CP009545) (Fig. 5k) using I-TASSER which resulted to model 1 with confidence score of -0.93 42. Although the BimABm variant shares only 54% of its sequence with BimABp K96243 23, its structure remains typical of an autotransporter in which the β-barrel C-terminal autotransporter domain serves as an anchor to the bacterial surface to form a pore for protein transport18,45.

3D structural analysis of major BimC types

The BimC amino acid sequence was retrieved from GenBank (Ref: WP_011205625.1, locus tag: BPSS1491) and categorized by Lu et al.35 into an autotransporter heptosyltransferase with a calculated molecular weight of 45,928 Dalton. The template for BimC homology modeling was based on SWISS-MODEL with GMQE (Global Model Quality Estimate) score of 0.77, using TibC, a dodecameric iron-containing heptosyltransferase from enterotoxigenic E. coli H10407 (4RB4), which has 43.85% sequence identity and 93% coverage of the BimC of B. pseudomallei K96243 46. Visualization using Discovery Studio Visualizer software showed that our BimC variants possessed several missense mutations located in the alpha helices of the protein’s secondary structure and lacked insertion or deletion sequences (Fig. 6a and e). The mutations found in major BimC types were listed in Table 1.

3D structural models of five major BimC types of B. pseudomallei. (a) The 3D structural model of BimC type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain) was built based on a template TibC of E. coli H10407 (4RB4) using SWISS-MODEL, with 43.85% sequence identity and 93% coverage and GMQE score of 0.77. The iron-finger motif (C354, C357, C373 and C385) is shown as an inset. (b – e) 3D structural models of BimC types 2, 3, 4 and 5. Mutation positions are represented in pink Corey-Pauling-Koltun (CPK) models and labeled accordingly. Figures were generated by Discovery Studio Visualizer version 21.1.

Moreover, mutations were not found in the four cysteine residues (C354, C357, C373, and C385) in the sequences of BimC types 1–5. These cysteine residues bind to the iron ion (Fe2+) to form the unique iron-finger motif (Fig. 6a, inset)35. The iron-finger motif is essential for the polar targeting of BimC and polymerization of BimA in B. thailandensis37. These steps are necessary for actin-tail formation to enable bacterial movement within and between the host cells47. Although the variations in BimC were minimal, further investigation is needed to validate their involvement in actin-tail formation.

B. pseudomallei isolates with different BimABp types can induce plaque formations

Stevens et al. previously reported that B. pseudomallei uses BimA to facilitate its intracellular movement and host cell membrane protrusion by initiating host actin polymerization, thereby enabling bacterial spread from one cell to another16. A way to assess the effect of cell-to-cell spread is by observing the plaque-forming efficiency in infected cells19. In this study, we examined the plaque-forming efficiencies of representative isolates of BimABp types 2, 4, 6, 9 (most distant from BimABp type 1) and 10 (carrying a missense mutation in the transmembrane domain) compared to B. pseudomallei K96243 (BimABp type 1) (Fig. 7). We observed plaques in A549 infected with the representative isolates although the plaque-forming efficiency (PFU/ml) of BimABp type 2 (mean ± standard deviation (SD) = 1.34 × 10−7 ± 2.77 × 10−8 PFU/ml; P = 0.2053), BimABp type 4 (mean ± standard deviation (SD) = 1.44 × 10−7 ± 2.68 × 10−8 PFU/ml; P = 0.4973), BimABp type 6 (mean ± standard deviation (SD) 1.71 × 10−7 ± 3.75 10−8 PFU/ml; P = 0.9995) and BimABp type 10 (mean ± standard deviation (SD) = 1.52 × 10−7 ± 6.00 × 10−8 PFU/ml; P = 0.7616) were not significantly different from that of BimABp type 1 (K96243). Interestingly, BimABp type 9 showed lower plaque-forming efficiency and was statistically different compared to BimABp type 1 (K96243) (mean ± SD = 1.02 × 10−7 ± 4.30 × 10−8 PFU/ml versus 1.77 × 10−7 ± 2.69 × 10−8 PFU/ml; P = 0.0018) and other types. The lower plaque formation in BimABp type 9 could be contributed by an amino acid change from threonine to alanine in the PDASX region, a predicted CK2 phosphorylation site that plays a role in actin polymerization and assembly16,48.

Plaque-forming efficiencies of representative strains harboring different BimABptypes in A549 cells. (a) Photographic representation of plaques. (b) Plaque-forming efficiencies of B. pseudomallei isolates harboring the different BimABp types in A549 cells. The cells were infected with B. pseudomallei strains representative of BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain), type 2 (DR10025A, DR20021A and DR40130A), type 4 (DR40111A, DR80025A and DR90085A), type 6 (DR10008A, DR40025A and DR50053A), type 9 (DR50173A, DR70003A and DR90006A), and type 10 (DR20062A, DR50003A and DR60054A) at MOI of 0.1:1. Plaques were stained with 2% (w/v) crystal violet at 24 h post-infection. Plaque-forming efficiency (PFU/ml) was counted as the number of plaques (plaque-forming units: PFU) divided by the CFU (colony-forming units) of bacteria added per well (CFU/ml). Error bars represent means ± standard deviation of data from three independent experiments (one-way ANOVA; P < 0.05).

Furthermore, we examined if the sixteen strains used in plaque assay possessed variations in proteins (BPSL0097, BPSS0015, BPSS1494 (VirG), BPSS1495 (VirA), BPSS1498 (Hcp-1), BPSS1818 and BPSS1860) involved in plaque formation and actin-based functions, as described in previous studies18,49,50,51 (Supplementary Data 2). We found that variations in BPSL0097, BPSS0015, BPSS1494 (VirG), BPSS1495 (VirA), BPSS1498 (Hcp-1), BPSS1818 and BPSS1860 also exist in these genomes.

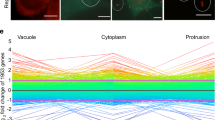

B. pseudomallei isolates with different BimABp types are all capable of inducing actin tails

Since B. pseudomallei utilizes the BimA protein factor to polymerize host actin17, we performed immunostaining and confocal microscopy of A549 epithelial cells infected with the representative isolates of six BimABp types to demonstrate their ability to form actin tails. The isolates included B. pseudomallei K96243 as representative of BimABp type 1 and the reference strain; DR40130A, DR40111A, DR10008A, DR50173A, and DR50003A, representing BimABp types 2, 4, 6, 9, and 10, respectively (Fig. 8a-g). The representative isolates of BimABp types 2, 4, 6, and 9 carried the most distant BimABp types from BimABp type 1, and type 10 had a missense mutation in the transmembrane domain.

Confocal microscopy images of A549 cells infected with B. pseudomallei isolates with different BimABptypes. The representative strains of B. pseudomallei (a) BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as the reference strain), (b) BimABp type 2 (DR40130A), (c) BimABp type 4 (DR40111A), (d) BimABp type 6 (DR10008A), (e) BimABp type 9 (DR50173A), and (f) BimABp type 10 (DR50003A) were used to infect A549 cells (g) at MOI of 30:1. Immunofluorescence staining was performed at 8 h post-infection using 4B11 monoclonal antibody specific to B. pseudomallei capsular polysaccharide to visualize the bacteria in green; phalloidin for F-actin in red; and Hoechst 33258 for the host DNA in blue. (h) The length of actin tails (white arrow) was determined using Zen Zeiss 3.0 SR (black) software tools. The mean lengths were: 3.1605 μm, BimABp type 1; 1.988 μm, BimABp type 2; 2.043 μm, BimABp type 4; 1.807 μm, BimABp type 6; 1.465 μm, BimABp type 9; and 1.603 μm, BimABp type 10 (one-way ANOVA; P < 0.05). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Our results demonstrated that all isolates were capable of polymerizing actin, as observed by the formation of a characteristic “comet” tail at the polar end of the bacteria. However, the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) actin tail length (µm) produced by the representative strains of BimABp type 9 (1.465 ± 1.291, P = 0.0182) and type 10 (1.603 ± 1.211, P = 0.0391) were significantly shorter than those generated by the reference, BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243) (3.1605 ± 2.354). In contrast, the actin tail lengths (µm) produced by the representative strains of BimABp type 2 (1.988 ± 1.627, P = 0.2227), type 4 (2.043 ± 1.701, P = 0.2714), and type 6 (1.807 ± 1.436, P = 0.1058) did not show significant differences compared to BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243) (Fig. 8h).

Discussion

Previous studies have reported the presence of a BimABm in B. pseudomallei isolates from Australia, India, and Sri Lanka and their association with neurological melioidosis30,31,32. However, the sequence variation within BimABp and its impacts on the actin-based motility function of BimA are unexplored. Similarly, while the role of BimC in actin-based motility and B. pseudomallei pathogenesis has been reported21, its variants and their implications have not been well investigated.

In this study, we examined the genomes of 1,294 B. pseudomallei clinical isolates and observed that BimA and BimC exhibited variations. In addition to BimABp type 1 of B. pseudomallei K96243, the BimABp variants were further classified into nine types, and four types (BimABp types 1,2, 3, and 4) were predominant in the three dominant lineages of B. pseudomallei, suggesting that BimABp variations may make some contributions to the formation of dominant lineages. However, in vitro and in vivo experiments are warranted to validate this conclusion.

Our analysis of 1,294 genomes identified five major BimC types of which none possessed insertion or deletion sequences but harbored nonsynonymous SNPs, suggesting that BimC is more conserved than bimA in B. pseudomallei. Moreover, 45% of our isolates (585/1,294) fell under BimC type 1, which shares 100% of the sequences with BimC of the B. pseudomallei K96243. Furthermore, BimC type 1 was predominant in major lineage 1, while the remaining BimC variant types 2–5 were associated with the minor lineages. Although we could not find a BimABm variant from our B. pseudomallei collections in Thailand, the dominant BimABp and BimC variants were widely dispersed across northeast Thailand, which is an evolutionary and transmission hotspot for B. pseudomallei in Southeast Asia52.

3D structural modeling of BimABp types allowed us to observe one or two additional PDAST (proline, aspartic acid (D), alanine, serine, and threonine) repeat sequences, with observable changes of threonine to alanine in this region, from the usual five PDAST repeats of the B. pseudomallei K96243. Similarly, there were variations in the number of PDASX repeats in BimA, ranging from two (found in B. pseudomallei BCC215) to seven (B. pseudomallei MSHR305)23. Notably, these PDASX repeats are the predicted sites of host casein kinase 2 phosphorylation23, an important post-translational modification catalyzed by protein kinases to regulate cell processes in eukaryotes and bacteria53. Protein kinases usually phosphorylate bacterial proteins on serine and threonine amino acid residues to conform structural changes or modify protein–protein interactions54. An example of a protein kinase is YopO of Yersinia spp., whose phosphorylation of the host actin-modulating proteins disrupts the actin filaments and inhibits actin polymerization55. Furthermore, Sitthidet et al. have explored the impact of in-frame deletion of two, five, and seven PDASX repeats in BimA B. pseudomallei, wherein they found that increased PDASX repeats function additively, indicating an increased rate of actin polymerization and assembly48. In addition, the trans-complement of B. pseudomallei bimA mutant harboring BimA with two, five, and seven PDASX repeats could restore actin-based motility and plaque formation in A549 cells without discernible variations between the morphology of actin tails and plaques48. In-depth molecular and biochemical investigations on the implications of the phosphorylation of BimA will be needed to gain a deeper understanding of the actin dynamics and functions of BimA in B. pseudomallei.

Our study observed that the B. pseudomallei isolates, which harbored phylogenomically distant BimABp types, formed plaques after 24 h of infection in A549 cells. However, the B. pseudomallei isolates carrying BimABp type 9 formed significantly lower plaques. The variation in the results of plaque-forming efficiency assay might be due to other bacterial motility factors, like the motA2 from the fla2 flagellar cluster where the deletion of bimA and motA2 genes almost completely abolished plaque formation in HEK293 cells49. To support our findings, we found that these strains do not only harbor variations in BimABp but also in BPSL0097, BPSS0015, BPSS1494 (VirG), BPSS1495 (VirA), BPSS1498 (Hcp-1), BPSS1818 and BPSS1860, which have been described as being involved in actin-based functions in B. pseudomallei18,49,50,51. Moreover, we observed that the representative B. pseudomallei isolates with sequence variations within BimABp were still effective in developing the actin tails. However, the mean actin tail length generated by BimABp type 9 was significantly shorter, consistent with the observed lower plaque formation. These observations could be due to variations in regulatory gene virAG, which controls the expression of BimA56, or other proteins involved in the actin-development process. For instance, Jitprasutwit et al. identified a cellular protein, named ubiquitous scaffold protein Ras GTPase-activating-like protein (IQGP1) and showed that it was recruited to the infected actin tails of B. pseudomallei and controlled the length and density of the actin tails57. Furthermore, we found the variation in BPSS1818, a predicted inner membrane protein which modulates the host’s tubulin, suggesting that it might also influence the actin-tail formation and actin-based motility of B. pseudomallei50.

This study has some limitations. First, genomic analysis was only performed on our clinical isolates, mainly collected in northeast Thailand, which may not cover all isolates that may have the bimABm gene in Southeast Asia. An In-depth screening for a bimABm allele in Southeast Asia will benefit from a large-scale genomic analysis that covers all global B. pseudomallei clinical and environmental isolates. Second, the isolates used in our plaque, immunostaining, and confocal microscopy assays were merely representatives of the BimABp variants, and each strain may employ various mechanisms and adaptive strategies to endow B. pseudomallei with virulence and overcome the host. More research into the BimABp and BimC variants at the molecular and structural level is crucial to better understand the virulence, pathogenicity and implications of BimABp and BimC variations.

Overall, this study highlights the variations within BimABp and BimC and the implications of BimABp variants for B. pseudomallei pathogenesis in A549 epithelial cells. Moreover, our work provides additional insight into the virulence mechanisms of B. pseudomallei and may aid in developing future research and therapeutic strategies for melioidosis.

Materials and methods

Biosafety approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MU2022-028). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experiments involving B. pseudomallei were performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory.

Whole genome sequencing data

The data sets used in this study were 1,294 short-read genomes from our previous DORIM study39. The genomes utilized were from 1,294 B. pseudomallei clinical isolates (collected from melioidosis patients admitted to nine hospitals (Udon Thani Hospital,Khon Kaen Hospital, Srinakarind Hospital, Nakhon Phanom Hospital, Mukdahan Hospital, Roi Et Hospital, Surin Hospital, Sisaket Hospital, and Buriram Hospital) in northeast Thailand between July 2015 and December 2018)38. Of all genomes, 1,265, 27, and 2 were the B. pseudomallei genomes isolated from patients residing in northeast Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, respectively. All genomes were checked for potential contamination with other closely related species by assigning taxonomic identity using Kraken v.1.1.158. Epidemiological data, isolate data, and genome accession codes used in this study are listed in Supplementary Data 1.

Genome assembly and mapping alignment

We performed de novo assembly of short-read data using Velvet v.1.2.10 59. Genome alignment of the 1,294 isolates used in this study and an Australasian outgroup MSHR5619 was achieved by mapping short-read sequences to B. pseudomallei strain K96243 (accession numbers BX571965 and BX571966) using Snippy v.4.6.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy). To prevent mapping errors and false SNP identifications, we filtered out SNPs with coverage of fewer than 10 reads and frequency below 0.9.

Detection of variations in BimA and BimC

bimABp (BPSS1492 in B. pseudomallei K96243), bimABm (BURPS668_A2118 in B. pseudomallei MSHR668), and bimC (BPSS1491 in B. pseudomallei K96243), were determined in 1,294 assembled genomes using BLAST with the option to retrieve bimABp,bimABm, and bimC sequences from each genome. Nucleotide alignment was subjected to CD-HIT v.4.8.1 60 with a 100% threshold to identify variations. Nucleotide sequences of each bimA and bimC types were then translated into amino acid sequences using the Sequence Manipulation Suite translation tool61 (www.bioinformatics.org) and aligned using MAFFT v.7 62. All bimA variants were subjected to PCR and were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Pairwise SAP (single amino acid polymorphism) distances were calculated using snp-dists v.0.7.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/snp-dists). SAP is defined based on single substitution of amino acid from the reference strain B. pseudomallei K96243.

Additionally, detection of variations in bpsl0097, bpss0015, virG (BPSS1494 in B. pseudomallei K96243), virA (BPSS1495 in B. pseudomallei K96243), hcp-1 (BPSS1498 in B. pseudomallei K96243), bpss1818, and bpss1860 in the genomes used in plaque-forming efficiency assay (DR10025A, DR20021A, DR40130A, DR40111A, DR80025A, DR90085A, DR10008A, DR40025A, DR50053A, DR50173A, DR70003A, DR90006A, DR20062A, DR50003A, and DR60054A) were performed following the same method as the detection of variations in BimA and BimC.

Population structure analysis

Of the 1,294 B. pseudomallei genomes used in our study, 1,265 isolates were studied for the population structure by our previous project39. In this study, we re-analyzed the population structure by adding 29 B. pseudomallei genomes from Laos (n = 27) and Cambodian (n = 2) patients to the 1,265 genomes using a combination of two independent approaches: (i) employing PopPUNK v.2.4.0 63 and (ii) constructing the ML phylogeny of core-SNP alignment with IQ-TREE v.2.0.3 64 as methods described by Seng et al.39. The spatial distribution map of the dominant lineages and the BimABp and BimC types were plotted using the latitude and longitude of the patients’ home addresses.

3D protein structure modeling

BimA and BimC amino acid sequences were subjected to BLAST search against the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (http://www.rcsb.org) to find a template for homology modeling. For BimA, our search in SWISS-MODEL yielded models with low percent sequence identity and low coverage (< 40%)46, which were unsuitable. We then proceeded to Phyre 2, an automatic fold recognition server for predicting the structure and/or function of target protein sequence, to enhance the search41, but we obtained similar results. We also explored AlphaFold; however, although the model generated had high sequence coverage (> 90%), our residues of interest (175–263) were in a region with a very low confidence score (pLDDT < 50)65. Therefore, we used the de novo protein modeling tool, I-TASSER (Iterative Threading ASSEmbly Refinement)42, which works through threading, to generate the best model for BimA. I-TASSER produced model 1 with a confidence score (C-score) of -0.96. C-score is calculated based on the significance of threading template alignments and the convergence parameters of the structure assembly simulations. C-score typically ranges from − 5 to 2, with higher value indicating models of greater confidence and vice-versa42. The BimA model built by I-TASSER was then subjected to the YASARA energy minimization tool43 and validated using the SAVES PROCHECK server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). All ten BimABp type models were built on one reference model BimABp K96243. The BimABm model was built using the reference BimABm MSHR668 with a confidence score of -0.93.

The BimC protein model was built based on a reference in PDB using SWISS-MODEL46, using the template TibC, a dodecameric iron-containing heptosyltransferase from enterotoxigenic E. coli H10407 (4RB4), which has 43.85% sequence identity and 93% coverage of the BimC of B. pseudomallei K96243. The built model has a GMQE score of 0.77 46 and validated using the SAVES PROCHECK server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). The generated 3D structures of the models were visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer software (Biovia v.21.1).

Plaque-forming efficiency assay

The plaque-forming efficiency was evaluated using A549 epithelial lung cells (CCL-185, American Type Culture Collection, MD, USA) as described previously66 with some modifications for 16 representative strains of the BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243), type 2 (DR10025A, DR20021A and DR40130A), type 4 (DR40111A, DR80025A and DR90085A), type 6 (DR10008A, DR40025A and DR50053A), type 9 (DR50173A, DR70003A and DR90006A) and type 10 (DR20062A, DR50003A and DR60054A). The cells were seeded at 3.0 × 105 cells/well into a 24-well tissue culture plate and incubated at 37℃ with 5% CO2 overnight. The culture medium was replaced with fresh RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, USA) to prepare the cells for infection. The cells were infected with representative strains of the BimABp variant types in duplicates at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1:1 at 37℃ with 5% CO2 for 2 h. Thereafter, the infected cell monolayers were washed with PBS two times and maintained in a culture medium containing 250 µg/ml kanamycin (Invitrogen) for 24 h to eliminate the extracellular bacteria. The infected cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 2% (w/v) crystal violet for 2 min. The plaque confirmatory test was done by visualizing the plaques under the microscope. Plaque-forming efficiency (PFU/ml) was counted as the number of plaques (plaque-forming units: PFU) formed, divided by the inoculation volume of bacteria (CFU/ml). The plaque-forming efficiency assay was performed in three independent experiments.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Immunostaining was performed for six representative isolates of BimABp type 1 (B. pseudomallei K96243, classified as type 1 was used as a reference strain), type 2 (DR40130A), type 4 (DR40111A), type 6 (DR10008A), type 9 (DR50173A), and type 10 (DR50003A) as previously described66 with some modifications. Briefly, A549 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/well on a sterile glass coverslip in a six-well tissue culture plate and incubated overnight at 37℃ with 5% CO2. The monolayers were infected with the six representative isolates at an MOI of 30:1 for 2 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS three times, and the extracellular bacteria were killed with 250 µg/ml kanamycin in RPMI. The infected cells were incubated further for 6 h, washed with PBS three times, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, and permeabilized with 0.5% triton X-100 for 30 min. After the washing, the permeabilized cells were incubated with 1:200 of 4B11 (2.5 µg/ml) monoclonal antibody specific to B. pseudomallei capsular polysaccharide67 at 37℃ for 1 h. The cells were then washed with PBS three times, followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 at dilution of 1:1,000 (Invitrogen) for B. pseudomallei detection, Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated phalloidin at dilution of 1:1,000 (Invitrogen) for actin staining, and Hoechst 33258 (1:1,000) (Invitrogen) for nuclear staining at 37℃ for 1 h. The stained cells were washed with PBS three times, and the coverslips were mounted on glass slides using 8 µl of ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Confocal microscopy was performed with a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss) using 100× objective lenses with oil immersion and Zen software (2010 edition, Zeiss, Germany). The excitation and emission wavelengths were 496/519 for Alexa Fluor 488, 352/461 for Hoechst 33258, and 594/633 for Alexa Fluor 647. For actin tail length measurement, Zeiss Zen 3.0 SR (black) software tools were utilized by counting 20 bacteria with actin tail per representative image of the BimABp type-harboring strains.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA). The data are presented as individual points and mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare three or more groups, while the t-test was used to compare two groups. For comparisons involving the lineage distribution of BimABp and BimC types, Chi-square test was used. The results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Ethical approval

This study and the consent procedure were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MUTM 2015-002-01 and MUTM 2022-038-01). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their representatives before enrollment.

Data availability

The genome sequence data presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The ENA under study accession number PRJEB25606 and PRJEB35787. The accession numbers for individual genomes were listed in Supplementary Data 1.

References

Cheng, A. C. & Currie, B. J. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18, 383–416. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.18.2.383 (2005).

Seng, R. et al. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates in the environment near a patient’s residence in Northeast Thailand. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007348 (2019).

Shaw, T. et al. Environmental factors associated with soil prevalence of the melioidosis pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei: a longitudinal seasonal study from South West India. Front. Microbiol. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.902996 (2022).

Wiersinga, W. J., Currie, B. J., Peacock, S. J. & Melioidosis N Engl. J. Med. 367, 1035–1044 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1204699 (2012).

Gassiep, I., Armstrong, M., Norton, R. & Human Melioidosis Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00006-00019 (2020).

Wongwandee, M. & Linasmita, P. Central nervous system melioidosis: a systematic review of individual participant data of case reports and case series. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007320. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007320 (2019).

Selvam, K. et al. Burden and risk factors of melioidosis in Southeast Asia: a scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315475 (2022).

Limmathurotsakul, D. et al. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.8 (2016).

Hinjoy, S. et al. Melioidosis in Thailand: Present and Future. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 3, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed3020038 (2018).

Currie, B. J. Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. in Elsevier eBooks. 2869–2879. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-443-06839-3.00221-6 (2010).

Currie, B. J. Melioidosis: evolving concepts in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Semin Respir Crit. Care Med. 36, 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1398389 (2015).

White, N.J. Melioidosis. Lancet. 361, 1715–1722. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0026898419010087 (2003).

CDC USA Federal Select Agent Program. Select Agents and Toxins List, (2023). https://www.selectagents.gov/sat/list.html. Accessed 12 July 2023.

Whiteley, L. et al. Entry, intracellular survival, and multinucleated-giant-cell-forming activity of Burkholderia pseudomallei in human primary phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 85, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00468-17 (2017).

Stevens, M. P. et al. An Inv/Mxi-Spa-like type III protein secretion system in Burkholderia pseudomallei modulates intracellular behaviour of the pathogen. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03190.x (2002).

Stevens, M. P. et al. Identification of a bacterial factor required for actin-based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04528.x (2005).

Benanti, E. L., Nguyen, C. M. & Welch, M. D. Virulent Burkholderia species mimic host actin polymerases to drive actin-based motility. Cell. 161, 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.044 (2015).

Lazar Adler, N. R., Stevens, J. M., Stevens, M. P. & Galyov, E. E. Autotransporters and their role in the virulence of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. Front. Microbiol. 2, 151. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00151 (2011).

Kespichayawattana, W., Rattanachetkul, S., Wanun, T., Utaisincharoen, P. & Sirisinha, S. Burkholderia pseudomallei induces cell fusion and actin-associated membrane protrusion: a possible mechanism for cell-to-cell spreading. Infect. Immun. 68, 5377–5384. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.68.9.5377-5384.2000 (2000).

Breitbach, K. et al. Actin-based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei involves the Arp 2/3 complex, but not N-WASP and Ena/VASP proteins. Cell. Microbiol. 5, 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00277.x (2003).

Srinon, V., Chaiwattanarungruengpaisan, S., Korbsrisate, S. & Stevens, J. M. Burkholderia pseudomalleiisimC Is required for actin-based motility, intracellular survival, and virulence. Front. Cell. Infect. 9, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00063 (2019).

Jitprasutwit, N. et al. In vitro roles of Burkholderia intracellular motility A (BimA) in infection of human neuroblastoma cell line. Microbiol. Spectr. 0, e01320-01323. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01320-23 (2023)

Sitthidet, C. et al. Prevalence and sequence diversity of a factor required for actin-based motility in natural populations of Burkholderia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 2418–2422. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00368-08 (2008).

Godoy, D. et al. Multilocus sequence typing and evolutionary relationships among the causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 2068–2079. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.5.2068 (2003).

Nierman, W. C. et al. Structural flexibility in the Burkholderia mallei genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 14246–14251. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403306101 (2004)

Gee, J. E. et al. Burkholderia thailandensis isolated from infected wound, Arkansas, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 24, 2091–2094. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2411.180821 (2018).

Glass, M. B. et al. Pneumonia and septicemia caused by Burkholderia thailandensis in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 4601–4604. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01585-06 (2006).

Pilátová, M. & Dionne, M. S. Burkholderia thailandissis Is virulent in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 7, e49745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049745 (2012).

Stevens, J. M. et al. Actin-binding proteins from Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia thailandensis can functionally compensate for the actin-based motility defect of a Burkholderia pseudomallei bimA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7857–7862. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.187.22.7857-7862.2005 (2005).

Jayasinghearachchi, H. S. et al. Biogeography and genetic diversity of clinical isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei in Sri Lanka. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0009917. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009917 (2021).

Shaw, T., Tellapragada, C., Kamath, A., Kalwaje Eshwara, V. & Mukhopadhyay, C. Implications of environmental and pathogen-specific determinants on clinical presentations and disease outcome in melioidosis patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007312. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007312 (2019).

Burnard, D. et al. Clinical Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates from north Queensland carry diverse bimABm genes that are associated with central nervous system disease and are phylogenomically distinct from other Australian strains. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0009482–e0009482. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009482 (2022).

Ghazali, A. K. et al. Whole-genome comparative analysis of Malaysian Burkholderia pseudomallei clinical isolates. Microb. Genom. 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000527 (2021).

Morris, J. L. et al. Increased neurotropic threat from Burkholderia pseudomallei strains with a B. mallei–like variation in the bimA motility gene, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 740–749. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2305.151417 (2017).

Lu, Q. et al. An iron-containing dodecameric heptosyltransferase family modifies bacterial autotransporters in pathogenesis. Cell. Host Microbe. 16, 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.008 (2014).

Yao, Q. et al. A structural mechanism for bacterial autotransporter glycosylation by a dodecameric heptosyltransferase family. eLife. 3, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.03714 (2014).

Lu, Q., Xu, Y., Yao, Q., Niu, M. & Shao, F. A polar-localized iron-binding protein determines the polar targeting of Burkholderia BimA autotransporter and actin tail formation. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 408–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12376 (2015).

Chantratita, N. et al. Characteristics and one year outcomes of melioidosis patients in Northeastern Thailand: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health - Southeast. Asia. 9, 100118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100118 (2023).

Seng, R. et al. Genetic diversity, determinants, and dissemination of Burkholderia pseudomallei lineages implicated in melioidosis in Northeast Thailand. Nat. Commun. 15, 5699. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50067-9 (2024).

Higgins, D. G., Thompson, J. D. & Gibson, T. J. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 266, 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8 (1996).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2015.053 (2015).

Zhang, Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform. 9, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-40 (2008).

Krieger, E. et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 77 Suppl 9, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.22570 (2009).

Dautin, N. & Bernstein, H. D. Protein secretion in Gram-negative bacteria via the autotransporter pathway. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093233 (2007).

Leo, J. C., Grin, I. & Linke, D. Type V secretion: mechanism(s) of autotransport through the bacterial outer membrane. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1088–1101. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0208 (2012).

Waterhouse, A. et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–w303. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky427 (2018).

Lasa, I., Dehoux, P. & Cossart, P. Actin polymerization and bacterial movement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1402, 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00009-3 (1998).

Sitthidet, C. et al. Identification of motifs of Burkholderia pseudomallei BimA required for intracellular motility, actin binding, and actin polymerization. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1901–1910. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.01455-10 (2011).

French, C. T. et al. Dissection of the Burkholderia intracellular life cycle using a photothermal nanoblade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 12095–12100. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1107183108 (2011)

Heacock-Kang, Y. et al. The Burkholderia pseudomallei intracellular ‘TRANSITome’. Nat. Commun. 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22169-1 (2021)

Burtnick, M. N. et al. The cluster 1 type VI Secretion System is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 79, 1512–1525. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01218-10 (2011).

Chewapreecha, C. et al. Global and regional dissemination and evolution of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16263. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.263 (2017).

Zhang, A., Pompeo, F. & Galinier, A. Overview of protein phosphorylation in bacteria with a main focus on unusual protein kinases in Bacillus subtilis. Res. Microbiol. 172, 103871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2021.103871 (2021).

Beltrao, P., Bork, P., Krogan, N. J. & Van Noort, V. Evolution and functional cross-talk of protein post-translational modifications. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/msb.201304521 (2013)

Lee, W. L. et al. Mechanisms of Yersinia YopO kinase substrate specificity. Sci. Rep. 7, 39998. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39998 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Regulation of type VI Secretion System during Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Infect. Immun. 79, 3064–3073. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.05148-11 (2011).

Jitprasutwit, N. et al. Identification of candidate host cell factors required for actin-based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Proteome Res. 15, 4675–4685. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00760 (2016).

Wood, D. E. & Salzberg, S. L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46 (2014).

Zerbino, D. R. & Birney, E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18, 821–829. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.074492.107 (2008).

Li, W., Jaroszewski, L. & Godzik, A. Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics. 17, 282–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/17.3.282 (2001).

Stothard, P. The sequence manipulation suite: JavaScript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques. 28, 1102, 1104. https://doi.org/10.2144/00286ir01 (2000).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkf436 (2002).

Lees, J. A. et al. Fast and flexible bacterial genomic epidemiology with PopPUNK. Genome Res. 29, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.241455.118 (2019).

Trifinopoulos, J., Nguyen, L. T., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W232–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw256 (2016).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 596, 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (2021).

Saiprom, N. et al. Genomic loss in environmental and isogenic morphotype isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei is associated with intracellular survival and plaque-forming efficiency. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008590 (2020).

Anuntagool, N. et al. Monoclonal antibody-based rapid identification of Burkholderia pseudomallei in blood culture fluid from patients with community-acquired septicaemia. J. Bacteriol. 49, 1075–1078. https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-49-12-1075 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patients, families, clinicians and staff from Udon Thani Hospital, Khon Kaen Hospital, Srinakarind Hospital, Nakhon Phanom Hospital, Mukdahan Hospital, Roi Et Hospital, Surin Hospital, Sisaket Hospital and Buriram Hospital who participated in this study. We would also like to thank the staff at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology and Mahidol-Oxford Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University for their support to this study. C.M.S.C. was supported by The German Academic Exchange Service: Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) - SEAMEO TropMed Network In-Country/In-Region scholarship [91777149]. N.C. and T.E.W. were supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH) (https://www.nih.gov) under Award Number U01AI115520. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was funded in part, by the Wellcome Trust [220211]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

C.M.S.C. was supported by The German Academic Exchange Service: Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) - SEAMEO TropMed Network In-Country/In-Region scholarship [91777149]. N.C. and T.E.W. were supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH) (https://www.nih.gov) under Award Number U01AI115520. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was funded in part, by the Wellcome Trust [220211]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C. and C.M.S.C. conceived and designed the study. N.C., N.S., T.E.W. and R.S. collected and identified bacterial isolates. N.C., C.M.S.C., and R.S. wrote the manuscript. R.S., C.C., N.C., S.T. and C.M.S.C. performed bioinformatics analysis. C.M.S.C. and N.S. performed laboratory experiments. U.B. and C.M.S.C. performed 3D structure modeling. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interests exists.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cagape, C.M.S., Seng, R., Saiprom, N. et al. Genetic variation, structural analysis, and virulence implications of BimA and BimC in clinical isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei in Thailand. Sci Rep 14, 24966 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74922-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74922-3