Abstract

Loneliness, defined as unmet needs for intimate relationships (emotional loneliness) or larger social connections (social loneliness), is a risk factor for internalizing disorders common among people with HIV (PWH). While loneliness is associated with facial emotion perception (FEP)—the ability to recognize others’ emotional expressions—research has focused on healthier, younger populations, limiting its generalizability to PWH. Further, the extent to which emotional and social loneliness is associated with FEP has not been examined. As such, this study assessed the relationship between loneliness subtypes and FEP in 75 PWH (mean age = 59.4; 56% male; 77% Black). Participants completed the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale and an FEP Task that measures recognition of happy, sad, angry, fearful, and neutral emotions. Emotional loneliness was associated with reduced neutral bias (r=− 0.28, P = 0.014) and lower overall accuracy (r=− 0.46, P < 0.001), including poorer recognition of fear, anger, happy, and neutral emotions. Social loneliness was related to greater inaccuracy in identifying negative emotions (r = 0.29, P = 0.011) and misperception of fear (r = 0.22, P = 0.049). Findings suggest that emotional and social loneliness are related to different aspects of FEP, underscoring the need for interventions targeting loneliness subtypes to improve FEP deficits and social-emotional functioning in PWH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loneliness, the subjective negative feeling stemming from unmet social needs from the social relationship, places people at a higher risk for poor mental and physical health1,2,3 Loneliness can be more precisely defined by the perceived deficiencies in specific types of social relationships that trigger feelings of loneliness4 Emotional loneliness arises when an individual perceives an absence of intimacy or closeness in relationship, while social loneliness arises when a person perceives a lack of belonging and community within a larger social network4,5 Studies demonstrate the conceptual distinction of emotional and social loneliness and suggest that emotional and social loneliness should be considered to determine which unmet needs from social relationships contribute to loneliness6,7 Evidence indicates that emotional and social loneliness may be differentially associated with different health conditions. For instance, emotional loneliness was found to be significantly related to an increased risk for mortality8,9,10.

People with HIV (PWH) often face social stigma and experience depression, which place them at a higher risk for loneliness11,12,13 Loneliness, in turn, may increase the perception of social threat, leading to an increased sensitivity to negative/threatening social stimuli1,14,15 This suggests that lonely individuals may have an attentional bias towards negative emotions. Facial emotion perception (FEP), the ability to accurately and rapidly process the facial emotions of others, is crucial for effective social interactions and maintaining social relationships16 Impairments in FEP can significantly disrupt social functioning, further exacerbate loneliness, and diminish well-being. Prior research has found that PWH experience deficits in FEP compared to people without HIV (PWoH), particularly in regard to recognizing negative emotions17,18,19 Psychiatric difficulties, such as depression, have also been consistently linked to negativity biases in PWoH, where neutral or ambiguous affective expressions are more likely to be perceived as negative20,21 In addition, a recent systematic and meta-analytic review of social cognition in HIV demonstrated consistent impairments in FEP among PWH compared to PWoH22 Notably, the review emphasized the potential for social cognitive deficits to contribute to broader psychosocial difficulties, including social isolation and impaired interpersonal functioning—factors intimately tied to loneliness. These findings underscore the need to investigate FEP in relation to loneliness in PWH.

Extant research on FEP in relation to loneliness has yielded mixed results regarding both the direction of the association and specific aspects of FEP. One study demonstrated that lonely adolescents were more accurate in recognizing happy, sad, and fearful faces than their non-lonely peers, even when accounting for symptoms of depression and anxiety23 Another study involving first-year psychology undergraduate students found that loneliness was associated with increased accuracy in recognizing sad faces but decreased accuracy in identifying fearful faces24 This study also found that both loneliness and depression were related to increased negativity bias, where neutral expressions were misattributed as sad. A more recent study involving young adults showed that loneliness was associated with reduced accuracy in identifying happy faces, even after controlling for other psychiatric comorbidities25.

Emerging evidence concerning the relationship between loneliness and FEP has primarily focused on healthy adolescents or younger populations, limiting the generalizability of these findings. In particular, there is a lack of research exploring loneliness and FEP in PWH. Prior studies have only examined loneliness as a unidimensional construct, leaving the associations between emotional and social loneliness and FEP unexplored. Based on prior studies using the unidimensional approach in younger populations and consistent findings that show differential effects of loneliness subtypes on various health outcomes, we hypothesized that both emotional and social loneliness would be related to FEP in PWH, with each subtype having distinct associations with different aspects of FEP. Understanding how these loneliness subtypes affect FEP may inform the development of targeted interventions.

Results

Seventy-five PWH (mean age = 59.40 [SD = 9.4]; 56% men; 77% Black; mean years of education = 14.05 [SD = 3.5]) were included as our sample. An overview of the descriptive statistics on sample characteristics and study variables are presented in Table 1.

The relationship between emotional and social loneliness was not significant (r = 0.11; p = 0.35). Figure 1 shows the frequencies of PWH who fall into the respective categories of high or low levels of emotional and social loneliness. This cross-tabulation results indicate that these loneliness subtypes do not completely overlap (X2 = 0.004, P = 0.95), and participants mostly fall into the “Low” category for both loneliness subtypes (n = 33), while fewer individuals report both “High” (n = 10) levels of loneliness subtypes. Additionally, some participants report “High” social (n = 20) or “High” emotional loneliness (n = 16) only.

Heatmap representing the cross-tabulation of emotional and social loneliness. This heatmap visualizes the frequency distribution across levels of emotional and social loneliness among participants. Darker shades indicate higher cell counts, while lighter shades indicate lower counts. The chi-square test of independence revealed no significant association between emotional and social loneliness (X2 = 0.00, P = 0.95). Darker regions indicate higher counts; lighter regions indicate lower counts; X2 = 0.00, P = 0.95.

Partial correlation results

Partial correlation results are shown in Table 2. Overall loneliness demonstrated a significant negative correlation with overall accuracy in FEPT (r = − 0.35, p = 0.002). This relationship was particularly significant for the perceptions of anger (r=− 0.31, p = 0.006), happy (r = − 0.27, p = 0.019), and neutral (r = − 0.42, p < 0.001) faces. Additionally, overall loneliness was associated with a higher negativity bias (r = 0.27, p = 0.020), inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum (r = 0.34, p = 0.002), and more fear bias (r = 0.29, p = 0.01).

Emotional loneliness showed stronger associations with accuracy in FEPT than overall loneliness. It was negatively correlated with overall accuracy (r = − 0.46, p < 0.001), and the accuracy in the perceptions of fear (r=− 0.46, p = 0.013), anger (r = − 0.37, p < 0.001), happy (r = − 0.39, p < 0.001), and neutral (r = − 0.44, p < 0.001) faces were particularly affected. In addition, emotional loneliness had a negative correlation with neutral bias (r = − 0.28, p = 0.014). The only notable association of social loneliness was with greater inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum (r = 0.29, p = 0.011) and fear bias (r = 0.22, p = 0.05).

ANCOVA results

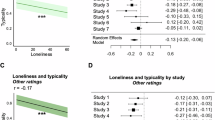

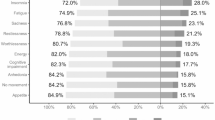

We conducted a follow-up analysis to determine potentially clinically relevant differences in the relationship between loneliness and FEPT performance (Table 3; Figs. 2 and 3). The results followed a similar pattern as the partial correlation results with some significant differences in FEPT that were not observed in partial correlations. Like the partial correlation results, participants with high overall loneliness had significantly reduced overall accuracy (p = 0.007), specifically in identifying neutral faces (p < 0.001), greater negativity bias (p = 0.013), greater inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum (p < 0.001), and more biases for fear (p = 0.002) emotion. Notably, the results also showed that participants in high overall lonely group had more biases for sad (p = 0.026) and anger (p = 0.022) emotions and less bias for neutral emotion (p = 0.025) compared to their counterparts in low lonely group.

Mean (SE) Accuracy in Facial Emotion Perception Tests Across Loneliness Types. This figure visualizes the distribution of the mean and standard error on the accuracy of Facial Emotion Perception Tests (overall accuracy and specific subsets of fear, sad, anger, happy, and neutral), stratified by high or low loneliness subtypes (overall, emotional, and social). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01.

Mean (SE) Facial Emotion Perception Tests Across Loneliness Types. This figure visualizes the distribution of the mean and standard error on different Facial Emotion Perception Tests (negativity bias, inaccuracy in negative emotion, fear bias, sad bias anger bias, neutral bias), stratified by high or low loneliness subtypes (overall, emotional, and social). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Similar to the partial correlation results, participants with high emotional loneliness were more likely to have lower overall accuracy in FEPT (p < 0.001), particularly driven by the lower accuracy for recognizing fear (p = 0.003), anger (p < 0.001), happy (p < 0.001), and neutral (p < 0.001) emotions, compared to participants in low emotional loneliness. Individuals with higher emotional loneliness also demonstrated lower neutral bias (p = 0.02).

Individuals with high social loneliness showed greater inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum (p = 0.017), consistent with the partial correlation results. A notable difference was that it was also associated with greater anger bias (p = 0.018).

Discussion

The present study assessed the relationship between loneliness and FEP among PWH and as a function of social and emotional loneliness, revealing significant differences in several aspects of FEP among PWH. Overall loneliness was related to lower accuracy and higher biased perception of facial emotions in PWH. This finding offers support for the theoretical frameworks of loneliness, which suggest that lonely individuals are hypervigilant to negative social stimuli and have more attentional biases toward negative emotions (i.e. negativity bias)1,14,15.

These findings also highlight the role of emotional loneliness in FEP among PWH. Emotional loneliness, but not social loneliness, was associated with poorer overall accuracy in FEP, particularly for recognizing fearful, angry, happy, and neutral faces. Moreover, individuals with higher emotional loneliness were less likely to misperceive affective expressions as neutral. This aligns with a recent review which emphasized that PWH demonstrate consistent impairments in recognizing negative and ambiguous emotions and are more prone to errors in interpreting subtle social signals22Emotional loneliness, which reflects a perceived lack of close or emotionally supportive relationships26, may amplify internal focus or cognitive biases that distort perception of others’ emotional states. In this context, neutral faces may be perceived as ambiguous or even threatening, resulting in errors in social interactions and an over- or under-estimation of intimacy in relationships. These misperceptions may reflect not only FEP impairment but broader disruptions in social cognition, including theory of mind and empathy, as described in the review. Our findings underscore the need to investigate whether interventions aimed at enhancing FEP accuracy—particularly in interpreting neutral or low-intensity expressions—could reduce emotional loneliness and improve social cognition in PWH.

In contrast, PWH with higher social loneliness did not show deficits in overall or emotion-specific accuracy but did demonstrate lower accuracy within the negative emotion spectrum, that is, correctly recognizing the emotion as negative but inaccurately classifying what negative emotion it is. Furthermore, partial correlation analyses showed an association between higher social loneliness and greater misperception of fearful emotions, while ANCOVA results showed an association between higher social loneliness and greater anger bias. Together, these findings suggest that the difficulties faced by PWH with higher social loneliness may be explained, in part, by a tendency to misperceive others’ emotional expression as angry or fearful. A continual tendency to misperceive these negative emotions, even when they are actually absent, may contribute to social loneliness by impairing individual’s sense of safety and belonging within their social network.

Taken together, these findings suggest that emotional loneliness may relate to difficulties with accurately perceiving emotions, with a specific bias towards under-identifying neutral emotions. In contrast, social loneliness appears to be linked to the misperception of angry or fearful faces and reduced accuracy in recognizing negative emotions. These results have important implications for understanding the distinct processes underlying emotional and social loneliness in PWH, highlighting the need to consider loneliness subtypes when examining emotional processing deficits in this population.

These findings are in contrast with other studies demonstrating an association between loneliness and FEP23,24,25 Specifically, while previous studies found that higher loneliness was related to higher accuracy in FEP, we found that higher loneliness was associated with lower accuracy. This discrepancy may be due to the sociodemographic differences in the samples, as prior research has predominantly focused on younger, healthy populations, whereas our sample was comparably older-aged PWH. Evidence has shown that both HIV17,18,19 and older age27,28 are associated with lower accuracy in FEP. Thus, HIV serostatus and age of our sample may have influenced the direction of the relationship we observed between loneliness and FEP. While loneliness has been associated with higher FEP accuracy in young, healthy individuals, it may instead exacerbate FEP deficits in older PWH.

Our findings have important implications for understanding social disconnection among PWH. Since the perception of different emotions can elicit different social responses in a social interaction —such as sadness prompting an approach response and anger triggering avoidance response29,30, the combination of a heightened negativity bias and reduced accuracy in recognizing negative emotions may lead lonely individuals to make more frequent or significant social errors. As such, to improve social functioning in PWH, interventions aimed at reducing loneliness could potentially enhance abilities in FEP, thereby improving social interactions and reducing the risk of misunderstandings and social conflicts.

The observed negativity bias among lonelier individuals in our sample suggests the need for interventions focusing on cognitive reappraisal to enhance emotion recognition and mitigate negative interpretative biases. Previous meta-analyses have shown that cognitive behavioral therapy and interventions targeting maladaptive social perceptions and attributions have been effective in improving emotional processes and reducing loneliness31,32 Future research should explore the effectiveness of targeted interventions in enhancing emotion perception and alleviating loneliness in this population. Finally, the differential effects observed across the loneliness subtypes highlight the complexity of loneliness as a construct. Emotional and social loneliness, while related to one another, appear to influence FEP differently. This suggests that tailored interventions that specifically target the unique aspects of emotional and social loneliness might be more effective than a one-size-fits-all approach.

While our study provides significant insights, it is important to acknowledge our limitations. The sample size was relatively small with uneven racial distribution, which limits the generalizability of the findings and underscores the need for future research with larger and more demographically diverse samples. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences, which precludes any conclusions about the directionality or causality of the relationship found in the study. While one possible interpretation is that deficits in FEP may contribute to difficulties in social communication and, in turn, increased loneliness, alternative explanations are equally plausible. For instance, loneliness itself may influence social cognitive processes, including FEP. Importantly, our intent is not to suggest that FEP deficits directly cause loneliness or to propose FEP as an immediate intervention target. Rather, these findings should be viewed as hypothesis-generating, identifying a potentially important area for further investigation. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the directionality of the relationships between loneliness and FEP over time. Additionally, experimental or intervention-based research will be essential to establish whether improving FEP abilities can meaningfully affect loneliness outcomes in PWH. Although the measure we used to assess for loneliness subtypes has been validated and has showed good internal consistency within our sample, the use of negatively and positively worded items for emotional and social loneliness subscales, respectively, may have introduced a potential source of bias and influenced the scoring for each subscale and total scale33 While categorizing participants by loneliness score using tertiles of the distribution aligns with findings from partial correlation results and provides insights about the overall sample that may not be evident when examining the mean alone, this approach raises questions about the clinical relevance of this cutoff34 Future studies are needed to determine the clinical cutoff for loneliness subtypes. Additionally, our task only included posed emotional photographs of White-presenting individuals. Research shows that, while emotion perception is a universal skill, it is influenced by sociocultural attributes, such that individuals are generally better at perceiving emotions of their own racial, gender, and age in-groups35,36 Although we adjusted all analyses for participant race, this may not have fully captured the FEP capacity of non-White participants. Given that our sample primarily consisted of non-White individuals, race may act more as an effect modifier than a confounding variable. Future research replicating our work using a racially diverse set of stimuli for FEP task involving a more diverse sample would be beneficial. Furthermore, while we initially assessed several covariates including depressive symptoms and HIV-related outcomes, on their associations with FEP, only race emerged as a significant factor related to FEP. As such, only race was adjusted in our final analyses to preserve model parsimony and reduce the risk of overfitting with our small sample size. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples are needed to explore whether these important factors act as mediators, moderators, or confounders in the relationship between loneliness and FEP. Additionally, future studies should also incorporate key HIV-related factors—such as HIV duration, stigma, and cognitive function— to better isolate the mechanisms underlying our observed associations. The timing of HIV diagnosis—particularly the sociocultural context in which people were diagnosed—is a meaningful factor that was not assessed in the current study. The experience of stigma has shifted considerably over the decades, with individuals diagnosed with HIV in the 1990 s or early 2000 s likely facing more pervasive stigma reinforcing social withdrawal, compared to those diagnosed more recently. These cohort effects may shape long-term social cognition, FEP, and internalized stigma trajectories. Future studies should consider this variable to better capture how historical stigma contexts interact with psychosocial and cognitive outcomes in people aging with HIV. Finally, another potential limitation of this study is the possibility of sampling bias related to loneliness. Individuals experiencing more profound or socially isolating forms of loneliness may be less likely to participate in research, particularly studies like ours that involve in-person visits involving FEPT. As a result, our sample may reflect a subset of PWH who, while experiencing loneliness, are also more socially engaged, psychologically resilient, or connected to healthcare and research infrastructures. This may lead to an underestimation of the true extent of FEP impairments among the most socially isolated and lonelier individuals. Future studies should consider alternative recruitment strategies—including home-based assessments or digital platforms—to engage those who are less likely to participate in traditional research but may be disproportionately affected by loneliness and related vulnerabilities.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that high loneliness is related to emotion processing deficits in PWH, including lower overall accuracy and misperception of neutral stimuli as negative. Within subtypes of loneliness, emotional loneliness was related to lower accuracy in identifying several aspects of emotions and under identifying emotions as neutral. In contrast, social loneliness was associated with overidentifying emotions as fearful or angry and greater inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum. Taken together, these results suggest that PWH with higher loneliness experience not only higher inaccurate perception of emotions but also greater bias towards perceiving facial expressions as negative. These findings underscore the importance of addressing specific subtype of loneliness to improve social functioning and emotional health in this population. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms underlying these associations and to develop effective interventions. Interventions that target loneliness subtypes and social cognition may help improve FEP deficits and promote social-emotional functioning in this population.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of an ongoing cohort study known as the Johns Hopkins Center for Advancement of HIV Neurotherapeutics- 4 th Clinical Outcomes Cohort (JH-CAHN COC4). JH-CAHN COC4 was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University (IRB00322465), conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study activities. Data were accrued between August 2022 to July 2024. Participants in JH-CAHN COC4 were primarily recruited through the John G. Bartlett HIV Practice at Johns Hopkins Hospital and from the surrounding Baltimore community. To enter JH-CAHN COC4, participants had to be between 30 and 90 years of age, English-speaking, able to travel to the clinic for assessments, virally suppressed (plasma HIV RNA viral load < 1,000copies/ml) and on antiretroviral therapy. Participants were excluded if they had any condition deemed by the study team clinicians as likely pose a safety risk or to interfere with successful participation. Other exclusion criteria were current, untreated hypertension or diabetes, head injury with loss of consciousness in the past year, positive urine toxicology screen (except marijuana or prescription medication use that were each allowed), acute intoxication or withdrawal, or history of substance use disorder in the past six months (based on structured clinical interview for DSM Disorders [SCID]). Participants provided written informed consent before provision of data that included a neuropsychological battery made up of self-report questionnaires (including the scale for loneliness) and objective testing across paradigms (including FEPT). Participants were compensated for their travel and time.

Measures

Loneliness

The 6-item version of the De Jong Gierveld (DJG), was used to assess overall loneliness, as well as the subdomains of emotional, and social loneliness37,38 The first three items assess emotional loneliness (e.g., I often feel rejected) and three items assess social loneliness (e.g., There are many people I can trust completely) with an option to respond as “Yes,” “More or less,” or “No.” Overall loneliness was computed as the sum of all six items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 6. For the negatively worded emotional loneliness items, “Yes” and “More or less” responses are scored as 1. The total score ranges from 0 to 3 with higher scores equating to more emotional loneliness. For the positively worded social loneliness items, “More or less” and “No” are scored as 1. Again, the total score ranges from 0 to 3 with higher scores equating to greater social loneliness. Because tertile data have not been previously reported in the literature, we did not use pre-determined cutoff points. Instead, we used the top tertile ranges derived from the distribution of each loneliness variable (overall, emotional, social loneliness) within the sample. High overall loneliness was defined as the total score ≥ 3. High emotional and social loneliness were defined as scores ≥ 2 on each subscale. The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (emotional loneliness: α = 0.63; social loneliness: α = 0.70; overall scale: α = 0.60), and comparable to what has been reported in a previous study with similar age groups (45–64 years of age; emotional loneliness: α = 0.69; social loneliness: α = 0.78; overall scale: α = 0.73).20

Facial emotion perception

The computerized Facial Emotion Perception Test (FEPT), was implemented to emotion processing of happy, sad, angry, fearful, and neutral faces. The task involves blocks of human faces and blocks of animals. The facial stimuli are static, black-and-white photographs of white faces from the Ekman and Friesen’s Pictures of Facial Affect series39,40 Each trial follows the same order: a fixation cross at the center of the screen, the primary stimulus (affective face or animal depending on the block) displayed for 500 ms, a visual mask for 500 ms, and then a forced-choice response page. During the forced-choice response, the participant identifies the emotion or animal which they believe they saw by pressing a corresponding key on the keyboard. We assessed the following aspects of FEPT: overall accuracy of all emotions (correctly identifying the expressed emotions), accuracy for each type of emotion, negativity bias (misperception of neutral/ambiguous stimuli as negative emotions), inaccuracy within the negative emotion spectrum (correctly identifying an emotion as negative but incorrectly identifying which negative emotion it is), and bias for specific emotions (pattern of misperceiving other emotions as a particular emotion such as the number of non-angry faces that were misperceived as angry).

Covariates

Several covariates were selected based on clinical assumptions and previous findings that suggest an association with FEP. These included sociodemographic factors (e.g., age, biological sex, race, ethnicity, years of education), CD4 + T cell count, HIV viral suppression (suppressed < 20 cp/ml vs. not suppressed ≥20 and < 100 cp/ml), and mental health symptoms including symptoms of anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD]−7)41, depression (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ]−9)42, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Scale [PCL-C])43.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate-level relationships among covariates, DJG, and FEPT were assessed using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), t-tests, or ANOVA, as appropriate. Partial correlations were calculated between total and subscale scores for loneliness and FEPT, adjusting for statistically significant covariates. Race was the only measured confounder that was significantly associated with various FEPT performance metrics. To assess for group differences in high vs. low loneliness on FEPT performance, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used with group as the between subjects factor and race as the covariate. All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics Version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and significance was considered at the p < 0.05 level.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13 (10), 447–454 (2009).

Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40 (2), 218–227 (2010).

Käll, A. et al. A common elements approach to the development of a modular cognitive behavioral theory for chronic loneliness. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 88 (3), 269–282 (2020).

Weiss, R. Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation (MIT Press, 1975).

Manoli, A., McCarthy, J. & Ramsey, R. Estimating the prevalence of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 21045 (2022).

Wolters, N. E. et al. Emotional and social loneliness and their unique links with social isolation, depression and anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 329, 207–217 (2023).

De Jong Gierveld, J. & Van Tilburg, T. The de Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur. J. Ageing. 7 (2), 121–130 (2010).

Dahlberg, L. & McKee, K. J. Correlates of social and emotional loneliness in older people: evidence from an english community study. Aging Ment Health. 18 (4), 504–514 (2014).

OʼSúilleabháin, P. S., Gallagher, S., Steptoe, A. & Loneliness Living alone, and All-Cause mortality: the role of emotional and social loneliness in the elderly during 19 years of Follow-Up. Psychosom. Med. 81 (6), 521–526 (2019).

Hyland, P. et al. Quality not quantity: loneliness subtypes, psychological trauma, and mental health in the US adult population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54 (9), 1089–1099 (2019).

Harris, M. et al. Impact of loneliness on brain health and quality of life among adults living with HIV in Canada. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 84 (4), 336–344 (2020).

Greene, M. et al. Loneliness in older adults living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 22 (5), 1475–1484 (2018).

Yoo-Jeong, M., Hepburn, K., Holstad, M., Haardörfer, R. & Waldrop-Valverde, D. Correlates of loneliness in older persons living with HIV. AIDS Care. 32 (7), 869–876 (2020).

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S. & Boomsma, D. I. Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cogn. Emot. 28 (1), 3–21 (2014).

Qualter, P. et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 (2), 250–264 (2015).

Adolphs, R. Is the human amygdala specialized for processing social information?. Ann. New. York Acad. Sci. 985(1), 326–340 (2003).

Clark, U. S., Cohen, R. A., Westbrook, M. L., Devlin, K. N. & Tashima, K. T. Facial emotion recognition impairments in individuals with HIV. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 16 (6), 1127–1137 (2010).

Baldonero, E. et al. Evaluation of emotion processing in HIV-infected patients and correlation with cognitive performance. BMC Psychol. 1 (1), 3 (2013).

González-Baeza, A. et al. Facial emotion processing in aviremic HIV-infected adults. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 31 (5), 401–410 (2016).

Bourke, C., Douglas, K. & Porter, R. Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: a review. Aust N Z. J. Psychiatry. 44 (8), 681–696 (2010).

Elliott, R., Zahn, R., Deakin, J. F. & Anderson, I. M. Affective cognition and its disruption in mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 36 (1), 153–182 (2011).

Vance, D. E. et al. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of social cognition among people living with HIV: implications for Non-Social cognition and social everyday functioning. Neuropsychol. Rev. (2024).

Vanhalst, J., Gibb, B. E. & Prinstein, M. J. Lonely adolescents exhibit heightened sensitivity for facial cues of emotion. Cogn. Emot. 31 (2), 377–383 (2017).

Cheeta, S., Beevers, J., Chambers, S., Szameitat, A. & Chandler, C. Seeing sadness: comorbid effects of loneliness and depression on emotional face processing. Brain Behav. 11 (7), e02189 (2021).

Akram, U. & Stevenson, J. C. Altered perception of emotional faces in young adults experiencing loneliness after controlling for symptoms of insomnia, anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disorders Rep. 12, 100581 (2023).

Gardiner, C., Geldenhuys, G. & Gott, M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc. Care Community. 26 (2), 147–157 (2018).

Grainger, S. A., Henry, J. D., Phillips, L. H., Vanman, E. J. & Allen, R. Age deficits in facial affect recognition: the influence of dynamic cues. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 72 (4), 622–632 (2017).

Cortes, D. S. et al. Effects of aging on emotion recognition from dynamic multimodal expressions and vocalizations. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 2647 (2021).

Seidel, E. M., Habel, U., Kirschner, M., Gur, R. C. & Derntl, B. The impact of facial emotional expressions on behavioral tendencies in women and men. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 36 (2), 500–507 (2010).

Marsh, A. A., Ambady, N. & Kleck, R. E. The effects of fear and anger facial expressions on approach-and avoidance-related behaviors. Emotion 5 (1), 119 (2005).

Hickin, N. et al. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for loneliness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 88, 102066 (2021).

Wong, N. M. L. et al. Meta-analytic evidence for the cognitive control model of loneliness in emotion processing. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 138, 104686 (2022).

Penning, M. J., Liu, G. & Chou, P. H. B. Measuring loneliness among middle-aged and older adults: the UCLA and de Jong Gierveld loneliness scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 118, 1147–1166 (2014).

Busch, E. L. Cut points and contexts. Cancer 127 (23), 4348–4355 (2021).

Engelmann, J. B. & Pogosyan, M. Emotion perception across cultures: the role of cognitive mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 4, 118 (2013).

Conley, M. I. et al. The Racially diverse affective expression (RADIATE) face stimulus set. Psychiatry Res. 270, 1059–1067 (2018).

De Jong-Gierveld, J. & Kamphuls, F. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 9 (3), 289–299 (1985).

Gierveld, J. D. J. & Tilburg, T. V. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging. 28 (5), 582–598 (2006).

Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. Pictures of Facial Affect (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976).

Jenkins, L. M. et al. Amygdala and dorsomedial hyperactivity to emotional faces in youth with remitted major depression. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2015, nsv152 (2015).

Löwe, B. et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care. 46 (3), 266–274 (2008).

Kroenke, K. et al. Patient health questionnaire anxiety and depression scale: initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosom. Med. 78 (6), 716–727 (2016).

Blanchard, E. B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T. C. & Forneris, C. A. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav. Res. Ther. 34 (8), 669–673 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants for their participation. This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins University Center for the Advancement of HIV Neurotherapeutics (JHU CAHN; P30MH075673, MPI: Rubin, Slusher, Clements) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH128955, MPI: T. Wilson, J. Meyers). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors on this paper meet the four criteria for authorship as identified by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE); all authors have contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted or have been involved in revising this manuscript, reviewed the final version of this manuscript before submission, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Specifically, using the CRediT taxonomy, the specific contributions of each author is as follows: Conceptualization & Methodology: M.Y-J, L.R; Formal Analysis: L. R., R. D., E. S.; Funding acquisition: L. R.; Investigation: L. R.; Project administration: G. M., J. P., S. R., I.T.; Supervision: L. R.; Validation: L. R., T. W.; Writing – original draft: M. Y-J.; Writing/Revising – L. R., T. W., J. C., A.W., S.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo-Jeong, M., Easter, R.E., Coughlin, J.M. et al. Loneliness is related to facial emotion perception in people with HIV. Sci Rep 15, 22370 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04237-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04237-4