Abstract

Xyloglucan, a plant hemicellulosic polysaccharide, has a β-glucan main chain and complex side chains composed of sugars such as xylose, galactose and fucose. In this study, we identified xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes in the thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. TmCel74, belonging to glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 74, was found to be an endo-processive-type xyloglucanase that degraded xyloglucan into xyloglucan oligosaccharides and was able to cleave the β-glucan main chain at both unbranched and xylosylated glucosyl residues. The gene locus of TmCel74 was located near the loci encoding α-l-fucosidase (GH29), α-xylosidase TmAxy31 (GH31), and β-galactosidase TmBgalB (GH42). TmAxy31 and TmBgalB released xylosyl and galactosyl residues, respectively, from xyloglucan oligosaccharides, but not from xyloglucan polysaccharides, indicating that these exo-type glycoside hydrolases cooperatively degrade the side chains of xyloglucan oligosaccharides produced from xyloglucan by TmCel74. Our findings shed light on the complex genetic locus required for xyloglucan degradation in T. maritima.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima produces thermostable glycoside hydrolases, including endo-β-glucanases and β-mannanases, which are involved in the degradation of plant polysaccharides1. These enzymes of T. maritima show very high stability at high temperatures and the thermostability of these enzymes is important for their industrial utilization.

Xyloglucan is a major hemicellulosic polysaccharide found in plant cell walls as a matrix polysaccharide and in plant seeds as a storage polysaccharide2. Xyloglucan has β-(1→4)-glucan as the main chain, and the O−6 positions of glucopyranosyl residues of the glucan main chain are regularly substituted with α-d-xylopyranosyl residues. The xylopyranosyl side chains are modified with other saccharides, such as β−1,2-linked galactopyranosyl residues (Fig. 1A). In addition, other sugars, such as α-(1→2)-linked l-fucose and α-(1→2)-linked l-arabinose are attached to the xyloglucan side chains3. The structures of the side chains of xyloglucan are abbreviated using single letters as follows: G, an unbranched glucopyranosyl segment; X, an α-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl segment; L, a β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl segment; and F, a α-l-fucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→2)-α-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl segment (Fig. 1A)4. Microorganisms produce several glycosidases that degrade and assimilate xyloglucan. For example, xyloglucanases, which are xyloglucan-specific endo-β−1,4-glucanases, degrade xyloglucans into xyloglucan oligosaccharides5,6. In addition to xyloglucanases, some cellulases (endoglucanases) degrade cellulose and xyloglucan7. Isoprimeverose-producing enzymes and oligoxyloglucan-reducing end-specific cellobiohydrolases (OXG-RCBHs) release isoprimeverose [α-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-d-glucose] from the non-reducing end of xyloglucan oligosaccharides and xylosylated cellobiose [such as XG: Glc2Xyl1, α-d-xylopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-d-glucose] from the reducing end of xyloglucan oligosaccharides, respectively8,9,10,11. Xyloglucan oligosaccharides are degraded into monosaccharides through the enzymatic cooperation of β-galactosidases12,13, α-xylosidases14,15,16,17, α-l-fucosidase18,19, and β-glucosidase18,20. β-Galactosidases release galactopyranosyl residues attached to xylopyranosyl side chains, whereas α-xylosidases release xylopyranosyl side chains from the β-(1→4)-glucan main chains of xyloglucan oligosaccharides and isoprimeverose. The debranched oligosaccharides are then degraded into glucose by β-glucosidases. Glycoside hydrolases are classified into the glycoside hydrolase (GH) family based on their amino acid sequences (https://www.cazy.org)21. β-Galactosidases are found in many GH families including 2, 35, and 42, while α-xylosidases are only found in GH31. In bacteria, GH2, GH35, and GH42 β-galactosidases are involved in the degradation of xyloglucan oligosaccharides20. Xyloglucanases have also been found in GH5, 9, 12, 16, 26, 44, 45, and 74. Many xyloglucanases cleave the glycosidic bond of unsubstituted glucopyranosyl residues in the xyloglucan main chain, but some xyloglucanases cleave the glycosidic bond of not only the unsubstituted glucopyranosyl residues but also the xylosylated glucopyranosyl residues in the xyloglucan main chain22,23. Xyloglucanases are divided into two types based on their mode of activity: endo-dissociative-type and endo-processive-type22,24. Both endo-dissociative- and endo-processive-type xyloglucanases hydrolyze the internal glycosidic bond between glucopyranosyl residues of the β-(1→4)-glucan main chain of xyloglucan. Endo-dissociative-type activity is a typical endo-type activity that repeats hydrolysis and desorption from xyloglucan polysaccharides. In contrast, endo-processive-type enzymes undergo repeated hydrolysis without desorption from xyloglucan polysaccharides25.

Except for Thermotoga maritima Cel74 (TmCel74), GH74 enzymes, which have been previously characterized, are xyloglucanases and OXG-RCBHs. However, TmCel74 has been reported to show higher hydrolytic activity toward (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan and the specific activity toward xyloglucan was less than one-fourth of that toward (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan26. In this study, we clarified that TmCel74 has high hydrolytic activity toward xyloglucan and that it is able to cleave not only the glycosidic bonds of unbranched glucopyranosyl residues, but also xylosylated glucosyl units in an endo-processive manner. In addition, we found that T. maritima possesses polysaccharide utilization locus (PUL) for xyloglucan degradation. This PUL contained genes encoding TmCel74 (TM_0305), GH29 α-l-fucosidase (TM_0306), l-fucose isomerase (TM_0307), a putative GH31 (TM_0308), and GH42 β-galactosidase TmBgalB (TM_0310) (Fig. 1B). TmBgalB released galactopyranosyl residues attached to the xylopyranosyl side chains of xyloglucan oligosaccharides, indicating that TmBgalB is involved in xyloglucan degradation. In addition, we characterized the putative GH31 enzyme and found that it has α-xylosidase activity toward isoprimeverose and xyloglucan oligosaccharides. The xyloglucan assimilation in T. maritima has not been elucidated, but our results suggested that T. maritima degrades xyloglucan, which has complex side-chain structures, by producing multiple glycoside hydrolases.

Structures of xyloglucan and xyloglucan-utilization locus of T. maritima. (A) Structure of xyloglucan. Abbreviations of the side chain structures are shown in boldface. Glc: glucopyranosyl residue, Xyl: xylopyranosyl residue, Gal: galactopyranosyl residue, l-Fuc: l-fucopyranosyl residue. (B) Loci of genes analyzed in this study. Gray arrows indicate genes encoding (putative) glycoside hydrolases.

Results

Substrate specificity, regiospecificity, and mode of action of TmCel74

Recombinant TmCel74 was heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described in the Materials and Methods section. The hydrolytic activities of TmCel74 toward xyloglucan and (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan were examined. The Michaelis constant (Km) and Vmax of recombinant TmCel74 toward xyloglucan were 21.1 ± 4.6 µg/mL and 196 ± 9 µmol/min/mg, respectively. In contrast, the Km and Vmax of recombinant TmCel74 toward (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan were 156 ± 59 µg/mL and 88.3 ± 9.9 µmol/min/mg, respectively. These results indicated that xyloglucan was preferred over (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan as the TmCel74 substrate. In addition to xyloglucan and (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan, TmCel74 showed weak hydrolytic activity toward glucomannan and carboxymethyl cellulose (data not shown), as previously reported26. These results indicated that TmCel74 has broad substrate specificity compared to other GH74 enzymes, but TmCel74 has highest specific activity toward xyloglucan. As reported previously, TmCel74 has high thermostability26; however, its activity gradually decreases when stored in a refrigerator for several weeks (data not shown).

During the degradation of tamarind seed xyloglucan, TmCel74 produced XXXG (Glc4Xyl3), XLXG/XXLG (Glc4Xyl3Gal1), and XLLG (Glc4Xyl3Gal2), as well as other xyloglucan oligosaccharides [such as hexose (Hex: Glc or Gal)3Xyl2, Hex6Xyl4, and Hex7Xyl4] (Fig. 2A and C), indicating that TmCel74 cleaves the β-glucan main chain of xyloglucan at both unbranched glucopyranosyl residues and xylosylated glucopyranosyl residues. During the degradation of (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan, TmCel74 produces tetra-, penta-, hepta-, octa-, and deca-saccharides (Glc4, Glc5, Glc7, Glc8, and Glc10) (Fig. 2B and D).

Xyloglucanases are composed of both endo-dissociative- and endo-processive-type xyloglucanases22. Previously, we reported that Aspergillus oryzae GH12 xyloglucanase (AoXeg12A) is endo-dissociative23. After the degradation of xyloglucan by AoXeg12A, compounds of mid-range molecular weight (retention time: 15–20 min) were detected in the initial stage of the reaction (Fig. 3B) using gel filtration chromatography. In contrast, these mid-range-molecular-weight compounds were negligible for xyloglucan degradation by TmCel74 (Fig. 3A). This xyloglucan degradation pattern of TmCel74 was similar to that of endo-processive-type xyloglucanases, such as Paenibacillus XEG7425. These results suggested that TmCel74 is an endo-processive-type xyloglucanase.

Degradation of xyloglucan and (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan with TmCel74. Xyloglucan was degraded by TmCel74, and the reaction products were analyzed by HPLC (A) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (C). (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan was degraded by TmCel74 and the reaction products were analyzed by HPLC (B) and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (D). Hex: hexose (glucose or galactose) residue, Glc: glucopyranosyl residue, Xyl: xylopyranosyl residue. Xyloglucan was incubated with TmCel74 in the presence of TmAxy31 (E) or TmBgalB (F). Xyl: xylose, Gal: galactose.

Identification of exo-acting xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes in T. maritima.

T. maritima contains genes encoding GH29, GH31, and GH42 at adjacent loci (Fig. 1B). The GH29 enzyme (TM_0306, GenBank accession number: AAD35394) was identified as an α-l-fucosidase27. Previously, Li et al. reported that the GH42 β-galactosidase TmBgalB shows hydrolytic activity toward chromogenic substrates [p-nitrophenyl (pNP) β-galactopyranoside and o-nitrophenyl (oNP) β-galactopyranoside]28. Given the low activity toward lactose, the natural substrate of TmBgalB remains unclear. In addition, GH31 (termed TmAxy31) has not yet been characterized.

Based on the predictions of signal peptides and their cleavage sites using SignalP (version 6.0, https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/)29, TmCel74 contained an N-terminal signal peptide (18 amino acid residues) for secretion. In contrast, GH29 α-l-fucosidase, GH31 TmAxy31, and GH42 TmBgalB do not contain N-terminal signal peptides. These predictions suggest that TmCel74 is an extracellular enzyme, and GH29 α-l-fucosidase, TmAxy31, and TmBgalB are intracellular enzymes. Purified recombinant TmAxy31 and TmBgalB were prepared as described in the Materials and Methods section. The enzymes were incubated with xyloglucan in the presence of TmCel74. TmAxy31 and TmBgalB released xylose and galactose from xyloglucan oligosaccharides produced by TmCel74 (Fig. 2E and F). These results suggested that TmAxy31 and TmBgalB are a xyloglucan oligosaccharide-active α-xylosidase and β-galactosidase, respectively.

The amino acid sequence of TmAxy31 was similar to that of α-xylosidases from E. coli (YicI, GenBank accession number: AAC76680; identity 51%)14, Aspergillus nidulans (AgdD, EAA62085; identity 47%)30, and Lactiplantibacillus pentosus (XylQ, AAC62251; identity 46%)31. Recombinant TmAxy31 had hydrolytic activity for pNP α-d-xylopyranoside (1.85 ± 0.02 µmol/min/mg), but not for other chromogenic substrates (pNP β-d-xylopyranoside, pNP α-d-glucopyranoside, pNP β-d-glucopyranoside, pNP α-d-galactopyranoside, pNP β-d-galactopyranoside, pNP α-l-fucopyranoside, pNP β-l-fucopyranoside, pNP β-d-fucopyranoside, pNP α-l-arabinofuranoside, pNP α-l-arabinopyranoside, pNP β-l-arabinopyranoside, pNP α-d-mannopyranoside, pNP β-d-mannopyranoside, and pNP α-l-rhamnopyranoside). The optimal pH and temperature for recombinant TmAxy31 activity toward pNP α-d-xylopyranoside were pH 5.5 and 85 °C, respectively. The hydrolytic activities of TmAxy31 toward isoprimeverose and reduced XXXG were 6.65 ± 0.34 and 14.4 ± 0.3 µmol/min/mg, respectively, suggesting that TmAxy31 preferred larger xyloglucan oligosaccharides than smaller oligosaccharides. However, TmAxy31 did not show hydrolytic activity toward xyloglucan polysaccharide, indicating that the degradation of xyloglucan to xyloglucan oligosaccharides by TmCel74 is vital for TmAxy31.

TmBgalB was incubated with lactose, xyloglucan, xyloglucan oligosaccharide, or pNP β-d-galactopyranoside. As reported previously, TmBgalB showed hydrolytic activity toward pNP β-d-galactopyranoside (Fig. 4A). In addition, TmBgalB released galactopyranosyl residues from xyloglucan oligosaccharides. However, under our assay conditions, no galactosidase activity was detected when lactose or xyloglucan polysaccharide were used as the substrates (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that TmBgalB is involved in xyloglucan degradation, and that the degradation of xyloglucan into xyloglucan oligosaccharides by TmCel74 is also important for TmBgalB.

During the degradation of xyloglucan oligosaccharides (mixture of XXXG, XXLG/XLXG, and XLLG; Fig. 4B) using TmBgalB, XLLG completely disappeared and XXXG levels increased, but the XXLG peak remained (Fig. 4C). In contrast, almost all galactosyl residues were released by the combination of TmBgalB and TmAxy31 (Fig. 4D). Previously reported GH31 α-xylosidases release only one molecule of xylose from one molecule of XXXG and produce GXXG from XXXG16,17, suggesting that the oligosaccharide produced from xyloglucan oligosaccharides (XXXG, XXLG/XLXG, and XLLG) by the combination of TmBgalB and TmAxy31 was GXXG (Fig. 4D). These results suggested that release of the xylopyranosyl side chain attached to the glucopyranosyl residue at the non-reducing end of xyloglucan oligosaccharides is important for TmBgalB activity. Therefore, TmAxy31 is important for the efficient function of TmBgalB in the degradation of the side chains of xyloglucan oligosaccharides.

Substrate specificity of TmBgalB. (A) TmBgalB was incubated with lactose, xyloglucan, xyloglucan oligosaccharides, or pNP β-d-galactopyranoside and the reaction products were analyzed using thin-layer chromatography. A xyloglucan oligosaccharide mixture containing XXXG, XXLG/XLXG, and XLLG (B) was incubated with TmBgalB in the absence (C) or presence (D) of TmAxy31 and the mono- and oligosaccharides produced were analyzed using HPLC.

Discussion

In this study, we identified xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes in the thermophilic bacterium T. maritima. As described above, TmCel74 is predicted to be an extracellular enzyme and GH29 α-l-fucosidase, TmAxy31, and TmBgalB are predicted to be intracellular enzymes, suggesting that T. maritima degrades xyloglucan into xyloglucan oligosaccharides by the endo-processive-type xyloglucanase, TmCel74, outside the cell. Xyloglucan oligosaccharides are then degraded into monosaccharides by the cooperative action of exo-type enzymes within the cell (Fig. 5). The xyloglucan of tamarind seed does not contain l-fucopyranosyl residues. However, the side chains of xyloglucan in the cell wall of dicotyledonous plants are modified with l-fucopyranosyl residues3, suggesting that GH29 α-l-fucosidase (TM_0306) and l-fucose isomerase (TM_0307) are involved in the degradation and assimilation of fucosylated xyloglucan.

The xyloglucan-utilization locus of T. maritima does not contain a gene encoding β-glucosidase, which degrades the β-glucan main chain of xyloglucan oligosaccharides into glucose; however, β-glucosidase belonging to GH1 has previously been identified in T. maritima (BglA, GenBank accession number: CAA52276)32. β-Glucosidase may be involved in the degradation of both cellulose and xyloglucan. In addition, there is a gene encoding a putative substrate-binding protein of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (TM_0309) between the genes encoding TmAxy31 and TmBgalB (Fig. 1B). This protein might contribute to the uptake of xyloglucan oligosaccharides by T. maritima cells. It has been previously reported that another substrate-binding component of the ABC transporter (TM_0300) binds xyloglucan oligosaccharides33. The gene encoding TM_0300 is also located near TmCel74, suggesting that T. maritima has xyloglucan-oligosaccharide-uptake machinery. In addition to xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes, T. maritima produces various types of plant polysaccharides degradation-related enzymes, including cellulases, mannanases, and xylanases1,34, suggesting that T. maritima degrades and assimilates cellulose and hemicelluloses of plants. Xyloglucan is a major hemicellulosic polysaccharide of land plants, but xyloglucan-like polysaccharides have also been found in algae35,36. T. maritima was isolated from geothermally heated sea sediment37, suggesting that xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes of T. maritima may be involved in the degradation of xyloglucan-like polysaccharides of algae.

TmCel74 has an endo-processive mode of action toward xyloglucans. In GH74 endo-processive-type xyloglucanases, two tryptophan residues in the + 3 and + 5 subsites are well conserved, and the tryptophan residue in the + 3 subsite is essential for endo-processive activity22,25. In TmCel74, the tryptophan residue in the + 3 subsite was conserved, whereas the aromatic residue in the + 5 subsite was a tyrosine residue (Fig. 6A). Aromatic residues in the positive subsites may be involved in the endo-processive mode of action of TmCel74.

TmAxy31 showed high specific activity not only for isoprimeverose, but also for a large xyloglucan oligosaccharide (XXXG). Although many GH31 α-xylosidases prefer isoprimeverose to large xyloglucan oligosaccharides, some GH31 α-xylosidases are known to exhibit high specific activity for large xyloglucan oligosaccharides15,38. In these GH31 α-xylosidases, such as Bacteroides ovatus BoGH31 and Cellvibrio japonicus Xyl31 A, the PA14 domain, which has a β-barrel structure and forms an insert in glycosidases39, is thought to be involved in the recognition of large xyloglucan oligosaccharides15,38,40. TmAxy31 did not contain a PA14 domain (Fig. 6B). Our future studies will focus on the detailed mechanisms of substrate recognition by TmAxy31, TmCel74, and TmBgalB using X-ray crystal structure analyses.

Xyloglucan-utilization loci have been well studied in Bacteroides, which degrade xyloglucan in the mammalian gut. For example, the xyloglucan-utilization loci of Bacteroides species (e.g., B. uniformis and B. fluxus) contain GH5 xyloglucanase, GH31 α-xylosidase, GH2 β-galactosidase, GH95 α-l-fucosidase, and GH43 α-l-arabinofuranosidase18. In contrast, T. maritima has GH74 xyloglucanase, GH31 α-xylosidase, GH42 β-galactosidase, and GH29 α-l-fucosidase for the degradation of xyloglucan. This indicates that microorganisms possess xyloglucan-utilization loci composed of GHs with different evolutionary origins, except for GH31 α-xylosidase, and are able to degrade xyloglucans with complex side chain structures.

Xyloglucan is used in foods as a viscosity-increasing polysaccharide and xyloglucan oligosaccharides are expected to exert physiological functions and prebiotic effects41. Thermostable xyloglucan degradation-related enzymes produced by T. maritima are thought to contribute to the enzymatic conversion of xyloglucan and its related oligosaccharides.

Sequence alignments of GH74 and GH31 enzymes. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of GH74 xyloglucanases. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Paenibacillus sp. XEG74 (Paenibacillus_XEG74, BAE44527), Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum Xeg74A (Clostridium_Xeg74A, AGF55626), Thermotoga maritima Cel74 (TmCel74, AAD35393), Streptomyces avermitilis SaGH74B (Streptomyces_SaGH74B, BAC70285), and Geotrichum sp. XEG (Geotrichum_XEG, BAD11543). Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org) code of Geotrichum sp. XEG is 3A0 F. Amino acid residues in + 3 and + 5 subsites are surrounded. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of GH31 α-xylosidases. GenBank accession numbers are follows: T. maritima Axy31 (TmAxy31, AAD35396), E. coli YicI (EcYicI, AAC76680), Cellvibrio japonicus Xyl31A (CjXyl31A, ACE86259), and Bacteroides ovatus GH31 (BoGH31, EDO11437). PDB codes of E. coli YicI and C. japonicus Xyl31 A are 1XSI and 2XVG, respectively. PA14 domains are surrounded. Amino acid sequences were aligned using the Clustal Omega program (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo). Asterisks, colons, and periods indicate fully conserved, strongly conserved, and weakly conserved amino acid residues, respectively.

Materials and methods

Materials

Genomic DNA of T. maritima MSB8 strain was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC 43589D-2; Manassas, VA, USA). Xyloglucan, (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan, and glucomannan were purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland). Carboxymethyl cellulose was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). pNP substrates and xyloglucan oligosaccharides were prepared as previously described42,43.

Heterologous expression and purification of glycoside hydrolases

The genes encoding TmCel74 (GenBank accession number: AAD35393), TmAxy31 (GenBank accession number: AAD35396), and TmBgalB (GenBank accession number: AAD35398) were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the genomic DNA of T. maritima MSB8 strain and the following primers: 5´-AGGAGATATACCATGGCAACTTTTGAGTGGAAATCGGTGG-3´ and 5´-GTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTTCCTCCTTCACTTCACCAACGATG-3´ for TmCel74, 5´-AGGAGATATACCATGCGTTTCACGGAAGGGCTTTGGAG-3´ and 5´-GTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTTTTGTCTTTAAAATCGCTCTCTGGAAGCTG-3´ for TmAxy31, and 5´-AGGAGATATACCATGGTAAATCCGAAACTTCCTGTGATCTGG-3´ and 5´-GTGGTGGTGCTCGAGTTCTTTTAGAAGGATCAGAACATCGAGC-3´ for TmBgalB. The pET-28a vector was linearized by PCR using the primers 5´-CATGGTATATCTCCTTCTTAAAGTTAAAC-3´ and 5´-CTCGAGCACCACCACCACCACCACTGAG-3´ and the pET-28a vector as a template. The amplified genes were cloned into the linearized pET-28a vector using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The resultant plasmids (pET-28a-TmCel74-His6, pET-28a-TmAxy31-His6, and pET-28a-TmBgalB-His6) were introduced into E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells harboring pET-28a-TmCel74-His6, pET-28a-TmAxy31-His6, or pET-28a-TmBgalB-His6 were grown to early logarithmic-phase in Luria-Bertani medium (1% peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% sodium chloride) supplemented with 20 µg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C, 150 rpm and then 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the medium. After incubation at 37 °C, 150 rpm for 2 h, the E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 3 min). Recombinant enzymes were extracted and purified using an Ni2+ affinity column, as described previously43. Purified recombinant enzymes were concentrated using an ultrafiltration membrane (Vivaspin Turbo 15 PES, 10 kDa cutoff; Sartorius Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The concentrations of the purified recombinant enzymes were determined using the bicinchoninic acid method, with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Substrate specificity of TmCel74

A reaction mixture (20 µL) containing polysaccharide [12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 µg/mL xyloglucan or 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1,600 µg/mL (1→3)(1→4)-β-glucan], 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and 1 ng of purified TmCel74 was incubated at 85 °C for 5 min. After the reaction, the concentration of the reducing sugars produced was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay44. A standard curve was constructed using glucose. Michaelis constant (Km) and Vmax were calculated as reported previously45.

Analysis of TmCel74 cleavage sites in Xyloglucan

A reaction mixture (200 µL) containing 4 mg/mL xyloglucan and 4.5 µg of TmCel74 was incubated at 70 °C for 12 h. After the reaction, the oligosaccharides produced were analyzed on a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a refractive index (RI) detector and a TSKgel Amide-80 5-µm column [4.6 mm internal diameter (I.D.) × 250 mm; Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan] using 60% acetonitrile (0.8 mL/min) as the column eluent at 40 °C, and mass spectrometry spectra of the produced oligosaccharides were acquired in linear positive ion mode using a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (MALDI-8020; Shimadzu Corp, Kyoto, Japan) as described previously23.

Gel-filtration chromatography analysis of TmCel74 and AoXeg12 A-treated-xyloglucan

Xyloglucan was treated with TmCel74 as described below. Twenty microliters of TmCel74 (4 µg/mL in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer [pH 5.5)] was added to 180 µL of 8 mg/mL xyloglucan and incubated at 70 °C. After various incubation times (1 to 4 h), the reaction solution was applied to a Superdex Peptide 10/300 GL gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) at 35 °C. Ultra-pure water was used as the column eluent, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The HPLC system was driven by a pump equipped with an RI detector.

Xyloglucanase from A. oryzae (AoXeg12A) was prepared as previously described23. Xyloglucan was treated with AoXeg12A, as described below. Twenty microliters of AoXeg12A [1 µg/mL in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5)] was added to 180 µL of 8 mg/mL xyloglucan and incubated at 40 °C. After various incubation times (1–4 h), the reaction products were analyzed using a gel filtration column, as described above.

Cooperative action of TmCel74 and TmAxy31 or TmBgalB on Xyloglucan degradation

A reaction mixture (200 µL) containing 4 mg/mL xyloglucan and 4.5 µg TmCel74 was incubated at 70 °C for 12 h in the presence of 1 µg of TmAxy31 or 2 µg of TmBgalB. After the reaction, the oligosaccharides produced were analyzed on an HPLC system using a TSKgel Amide-80 5-µm column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm), as described above.

Optimal pH and temperature of TmAxy31

The optimal pH for TmAxy31 activity was determined as follows. A reaction mixture (20 µL) containing 2 mM pNP α-d-xylopyranoside, 250 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5, 5.0, 5,5 or 6.0) and 0.26 µg of TmAxy31 was incubated at 70 °C for 10 min. After the reaction, 50 µL of 1 M sodium hydrogen carbonate was added to stop the reaction. The concentration of the released pNP was measured at 405 nm using an Infinite M200 PRO plate reader (Tecan, Zurich, Switzerland).

The optimal temperature for TmAxy31 was determined as follows. A reaction mixture (20 µL) containing 2 mM pNP α-d-xylopyranoside, 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and 0.2 µg of TmAxy31 was incubated at 65 to 90 °C for 10 min. After the reaction, 50 µL of 1 M sodium hydrogen carbonate was added to stop the reaction. The concentration of released pNP was measured as described above.

Substrate specificity of TmAxy31

The specificity of TmAxy31 for chromogenic substrates was determined as follows. A reaction mixture (40 µL) containing 2 mM chromogenic substrates (pNP α-d-xylopyranoside), 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and 80 ng of TmAxy31 was incubated at 80 °C for 10 min. After the reaction, 120 µL of 1 M sodium hydrogen carbonate was added to stop the reaction. The concentration of released pNP was measured as described above.

The substrate specificity of TmAxy31 for xyloglucan oligosaccharides (reduced XXXG) was determined as follows. The reaction mixture (10 µL) containing 2 mM reduced XXXG, 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and 20 ng of TmAxy31 was incubated at 80 °C for 10 min. The concentration of the released reducing sugars was measured using a bicinchoninic acid assay, as described above. A standard curve was constructed using xylose.

The substrate specificity of TmAxy31 for isoprimeverose was determined as follows. A reaction mixture (10 µL) containing 2 mM reduced XXXG, 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), and 20 ng of TmAxy31 was incubated at 80 °C for 10 min. The concentration of the glucose produced was measured using a Glucose Assay Kit-WST (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan).

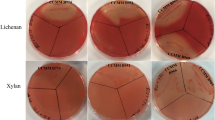

Substrate specificity of TmBgalB

Xyloglucan oligosaccharide mixtures containing XXXG, XXLG/XLXG, and XLLG were prepared as previously described8. The substrate specificities of TmBgalB toward lactose, xyloglucan, a xyloglucan oligosaccharide mixture, and pNP β-d-galactopyranoside were determined as follows. A reaction mixture (20 µL) containing 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), TmBgalB (5, 10, or 20 µg/mL), and substrate (10 mM lactose, 8 mg/mL xyloglucan, 10 mg/mL xyloglucan oligosaccharides, or 10 mM pNP β-d-galactopyranoside) was incubated at 70 °C for 10 min. The reaction products were analyzed using thin-layer chromatography on a Silica Gel 60 plate (Merck Millipore, Waltham, MA, USA) using a mobile phase of 2-propanol–acetic acid–water [4:1:1 (vol/vol/vol)]. The spots were detected using 2.5% p-anisaldehyde, 3.5% sulfuric acid, and 1% acetic acid in ethanol, as described previously19. The image of thin-layer chromatography was acquired using a scanner (CanoScan LiDE 400, Canon, Tokyo, Japan).

Xyloglucan oligosaccharide mixtures containing XXXG, XXLG/XLXG, and XLLG were incubated with TmBgalB in the presence or absence of TmAxy31, as described below. A reaction mixture (200 µL) containing 10 mg/mL xyloglucan oligosaccharide mixture, 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5), 4 µg of TmBgalB, and 4 µg of TmAxy31 was incubated at 70 °C for 16 h. After the reaction, the oligosaccharides produced were analyzed on an HPLC system equipped with an RI detector and a TSKgel Amide-80 5-µm column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm; Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) as described above.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chhabra, S. R., Shockley, K. R., Ward, D. E. & Kelly, R. M. Regulation of endo-acting Glycosyl hydrolases in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima grown on glucan- and mannan-based polysaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 545–554 (2002).

Buckeridge, M. S. Seed cell wall storage polysaccharides: models to understand cell wall biosynthesis and degradation. Plant. Physiol. 154, 1017–1023 (2010).

Fry, S. C. & Xyloglucan A metabolically dynamic polysaccharide. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol. 4, 279–289 (1992).

Tuomivaara, S. T., Yaoi, K., O’Neill, M. A. & York, W. S. Generation and structural validation of a library of diverse Xyloglucan-derived oligosaccharides, including an update on Xyloglucan nomenclature. Carbohydr. Res. 402, 56–66 (2015).

Grishutin, S. G. et al. Specific xyloglucanases as a new class of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1674, 268–281 (2004).

Yaoi, K., Nakai, T., Kameda, Y., Hiyoshi, A. & Mitsuishi, Y. Cloning and characterization of two xyloglucanases from Paenibacillus sp. strain KM21. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7670–7678 (2005).

van Casteren, W. H. et al. Endoglucanase V and a phosphatase from Trichoderma viride are able to act on modified exopolysaccharide from Lactococcus lactis subsp. Cremoris B40. Carbohydr. Res. 317, 131–144 (1999).

Matsuzawa, T., Mitsuishi, Y., Kameyama, A. & Yaoi, K. Identification of the gene encoding isoprimeverose-producing oligoxyloglucan hydrolase in Aspergillus oryzae. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 5080–5087 (2016).

Matsuzawa, T., Watanabe, M., Nakamichi, Y., Fujimoto, Z. & Yaoi, K. Crystal structure and substrate recognition mechanism of Aspergillus oryzae isoprimeverose-producing enzyme. J. Struct. Biol. 205, 84–90 (2019).

Yaoi, K. & Mitsuishi, Y. Purification, characterization, cloning, and expression of a novel xyloglucan-specific glycosidase, oligoxyloglucan reducing end-specific cellobiohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48276–48281 (2002).

Bauer, S., Vasu, P., Mort, A. J. & Somerville, C. R. Cloning, expression, and characterization of an oligoxyloglucan reducing end-specific Xyloglucanobiohydrolase from Aspergillus Nidulans. Carbohydr. Res. 340, 2590–2597 (2005).

Larsbrink, J. et al. A complex gene locus enables Xyloglucan utilization in the model saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 418–433 (2014).

Matsuzawa, T., Watanabe, M., Kameda, T., Kameyama, A. & Yaoi, K. Cooperation between β-galactosidase and an isoprimeverose-producing oligoxyloglucan hydrolase is key for Xyloglucan degradation in Aspergillus oryzae. FEBS J. 286, 3182–3193 (2019).

Okuyama, M., Kaneko, A., Mori, H., Chiba, S. & Kimura, A. Structural elements to convert Escherichia coli α-xylosidase (YicI) into α-glucosidase. FEBS Lett. 580, 2707–2711 (2006).

Larsbrink, J. et al. Structural and enzymatic characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 31 α-xylosidase from Cellvibrio japonicus involved in Xyloglucan saccharification. Biochem. J. 436, 567–580 (2011).

Matsuzawa, T., Kameyama, A. & Yaoi, K. Identification and characterization of α-xylosidase involved in Xyloglucan degradation in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 201–210 (2020).

Matsuzawa, T. et al. Characterization of an extracellular α-xylosidase involved in Xyloglucan degradation in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 675–687 (2022).

Déjean, G., Tauzin, A. S., Bennett, S. W., Creagh, A. L. & Brumer, H. Adaptation of syntenic Xyloglucan utilization loci of human gut Bacteroidetes to polysaccharide side chain diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e01491–e01419 (2019).

Shimada, N., Kameyama, A., Watanabe, M., Sahara, T. & Matsuzawa, T. Identification and characterization of xyloglucan-degradation related α-1,2-L-fucosidase in Aspergillus oryzae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 138, 196–205 (2024).

Larsbrink, J. et al. A discrete genetic locus confers Xyloglucan metabolism in select human gut Bacteroidetes. Nature 506, 498–502 (2014).

Drula, E. et al. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D571–D577 (2022).

Arnal, G. et al. Substrate specificity, regiospecificity, and processivity in glycoside hydrolase family 74. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 13233–13247 (2019).

Matsuzawa, T., Kameyama, A., Nakamichi, Y. & Yaoi, K. Identification and characterization of two xyloglucan-specific endo-1,4-glucanases in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 8761–8773 (2020).

Ichinose, H. et al. Characterization of an endo-processive-type xyloglucanase having a β-1,4-glucan-binding module and an endo-type xyloglucanase from Streptomyces avermitilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7939–7945 (2012).

Matsuzawa, T., Saito, Y. & Yaoi, K. Key amino acid residues for the endo-processive activity of GH74 xyloglucanase. FEBS Lett. 588, 1731–1738 (2014).

Chhabra, S. R. & Kelly, R. M. Biochemical characterization of Thermotoga maritima endoglucanase Cel74 with and without a carbohydrate binding module (CBM). FEBS Lett. 531, 375–380 (2002).

Tarling, C. A. et al. Identification of the catalytic nucleophile of the family 29 α-L-fucosidase from Thermotoga maritima through trapping of a covalent glycosyl-enzyme intermediate and mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47394–47399 (2003).

Li, L., Zhang, M., Jiang, Z., Tang, L. & Cong, Q. Characterization of a thermostable family 42 β-galactosidase from Thermotoga maritima. Food Chem. 112, 844–850 (2009).

Nielsen, H., Teufel, F., Brunak, S. & von Heijne, G. SignalP: the evolution of a web server. Methods Mol. Biol. 2836, 331–367 (2024).

Bauer, S., Vasu, P., Persson, S., Mort, A. J. & Somerville, C. R. Development and application of a suite of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes for analyzing plant cell walls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103, 11417–11422 (2006).

Chaillou, S. et al. Cloning, sequence analysis, and characterization of the genes involved in isoprimeverose metabolism in Lactobacillus pentosus. J. Bacteriol. 180, 2312–2320 (1998).

Liebl, W., Gabelsberger, J. & Schleifer, K. H. Comparative amino acid sequence analysis of Thermotoga maritima β-glucosidase (BglA) deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the gene indicates distant relationship between β-glucosidases of the BGA family and other families of β-1,4-glycosyl hydrolases. Mol. Gen. Genet. 242, 111–115 (1994).

Nanavati, D. M., Thirangoon, K. & Noll, K. M. Several archaeal homologs of putative oligopeptide-binding proteins encoded by Thermotoga maritima bind sugars. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1336–1345 (2006).

Winterhalter, C., Heinrich, P., Candussio, A., Wich, G. & Liebl, W. Identification of a novel cellulose-binding domain within the multidomain 120 kda Xylanase XynA of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Mol. Microbiol. 15, 431–444 (1995).

Ikegaya, H. et al. Presence of xyloglucan-like polysaccharide in Spirogyra and possible involvement in cell-cell attachment. Phycol. Res. 56, 216–222 (2008).

Domozych, D. S., Sørensen, I. & Willats, W. G. The distribution of cell wall polymers during antheridium development and spermatogenesis in the charophycean green alga, Chara corallina. Ann. Bot. 104, 1045–1056 (2009).

Huber, R. et al. Thermotoga maritima sp. Nov. Represents a new genus of unique extremely thermophilic eubacteria growing up to 90°C. Arch. Microbiol. 144, 324–333 (1986).

Silipo, A. et al. NMR spectroscopic analysis reveals extensive binding interactions of complex Xyloglucan oligosaccharides with the Cellvibrio japonicus glycoside hydrolase family 31 α-xylosidase. Chemistry 18, 13395–13404 (2012).

Rigden, D. J., Mello, L. V. & Galperin, M. Y. The PA14 domain, a conserved all-β domain in bacterial toxins, enzymes, adhesins and signaling molecules. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 335–339 (2004).

Hemsworth, G. R. et al. Structural dissection of a complex Bacteroides ovatus gene locus conferring Xyloglucan metabolism in the human gut. Open. Biol. 6, 160142 (2016).

Yamamoto, K., Shirakawa, M., Kuwano, K., Suzuki, J. & Mitamura, T. Effects of hydrolyzed Xyloglucan on lipid metabolism in rat. Food Hydrocoll. 10, 369–372 (1996).

Matsuzawa, T., Kimura, N., Suenaga, H. & Yaoi, K. Screening, identification, and characterization of α-xylosidase from a soil metagenome. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 122, 393–399 (2016).

Matsuzawa, T. & Yaoi, K. Screening, identification, and characterization of a novel saccharide-stimulated β-glycosidase from a soil metagenomic library. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 633–646 (2017).

Fox, J. D. & Robyt, J. F. Miniaturization of three carbohydrate analyses using a microsample plate reader. Anal. Biochem. 195, 93–96 (1991).

Kitaoka, M. Automatic calculation of the kinetic parameters of enzymatic reactions with their standard errors using Microsoft excel. J. Appl. Glycosci. 70, 33–37 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bioinformatics Research Facility (Kagawa University) for their technical expertise. We thank Dr. Katsuro Yaoi and Dr. Takehiko Sahara (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan) for providing oligosaccharides. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: TM, HS. Analyzed the oligosaccharides: YK, TM, AK. Preparation of enzyme: TM, YK. Performed and analyzed all other experiments: TM, YK. Wrote the paper: TM, YK, AK, HS. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawai, Y., Kameyama, A., Sakuraba, H. et al. Characterization of glycoside hydrolases involved in xyloglucan degradation in the thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Sci Rep 15, 19922 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05366-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05366-6