Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the number of psychotropic medications on short-term neonatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by maternal psychiatric disorders, focusing on the effect of non-opioid psychotropic polypharmacy and co-exposure. A retrospective study was conducted on pregnancies complicated by maternal mental disorders that resulted in full-term singleton deliveries at a tertiary perinatal hospital between 2019 and 2023. Among 4,367 deliveries during the study period, 358 were identified. Pregnant women prescribed three or more psychotropic medications had significantly higher rates of adverse neonatal outcomes. Significantly, most infants exhibiting neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS)-related symptoms were exposed in utero to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and benzodiazepines (BZs). Furthermore, neonates exposed to CYP2D6-inhibiting psychotropic drugs had significantly lower Apgar scores and higher rates of neonatal intensive care unit admission, respiratory ventilator use, and NAS compared to those not exposed to such drugs. Full-term neonates born to women with mental illness taking three or more psychotropic drugs were significantly more likely to experience adverse short-term outcomes. Particular attention should be given to neonatal adaptation in infants exposed in utero to CYP2D6-inhibiting psychotropic drugs, as well as SSRIs and BZs, especially in cases of multiple psychotropic medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychiatric disorders are the most common conditions affecting women of childbearing age1,2. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders has increased, with recent data indicating that approximately 30% of women in developed countries are affected2, and estimates place the prevalence of psychiatric disorders during pregnancy at approximately 20%3,4,5,6. This trend has led to more pregnancies complicated by psychiatric disorders, presenting serious challenges in clinical practice3,5,7. Numerous reports show that such pregnancies are associated with an increased risk of obstetric complications, such as gestational hypertension and diabetes, and adverse neonatal outcomes, such as preterm delivery and low birth weight1,2,6,7.

Pregnancy is a period of heightened psychological vulnerability characterized by a higher risk of mental instability2,3. During the postpartum period, maternal psychiatric instability may adversely affect child development through neglect and abuse. To mitigate these risks, many pregnant women with psychiatric disorders require pharmacological interventions, often involving multiple psychotropic medications2,7,8. The proportion of psychotropic polytherapy continues to rise and 70–80% of exposed women received antipsycotics in polytherapy8. Given that polypharmacy is a common treatment modality for psychiatric disorders during pregnancy, a comprehensive understanding of its impact on fetal and neonatal health is essential.

To date, numerous studies have examined the effects of in utero exposure to individual psychotropic medications on neonatal outcomes and have shown that the appropriate use of single psychotropic medications during pregnancy has minimal adverse effects on obstetric and neonatal outcomes1,2,3,7.. However, evidence remains insufficient regarding the impact of the number of psychotropic medications and their co-exposure during pregnancy8,9,10. In particular, while increasing maternal opioid use has contributed to a rising incidence of opioid-induced neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in many countries, the effects of non-opioid psychotropic polypharmacy and co-exposure during pregnancy on neonatal outcomes remain unclear. In Japan, opioids are not commonly used during pregnancy, and illicit drug use is relatively rare. Consequently, NAS in Japan is rarely associated with opioid exposure is instead more frequently linked to maternal use of antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants11.

This study aimed to investigate the impact of the number of psychotropic medications on short-term neonatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by maternal psychiatric disorders. Specifically, we focused on the effect of non-opioid psychotropic polypharmacy and co-exposure. Additionally, we sought to identify specific medications that may adversely affect neonatal outcomes and to assess whether particular combinations of psychotropic agents are associated with increased risk.

Material and methods

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kitasato University School of Medicine and Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: B24-085). The Committee approved the waiver of written informed consent and opt-out informed consent was employed due to the retrospective study design.

Study population

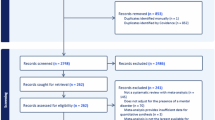

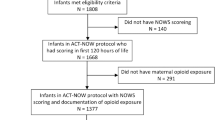

This retrospective study examined pregnancies complicated by maternal mental disorders that resulted in full-term deliveries at Kitasato University Hospital from 2019–2023. During the study period, 4,367 deliveries occurred at our hospital. Among these, 358 were full-term singleton pregnancies complicated by maternal mental disorders. As Kitasato University Hospital is a tertiary care facility, the cohort included women who received prenatal care at the hospital from early pregnancy and those referred during pregnancy due to maternal or fetal complications such as hypertension, fetal growth restriction, and fetal structural abnormalities. A patient selection flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Data collection

This study used birth registry records containing basic information, including maternal age, obstetric history, and clinical diagnoses. Antenatal data were retrospectively collected, including maternal demographic details (age, parity, and preexisting chronic conditions), mode of conception, and obstetric complications. Delivery-related data were also reviewed, including birth weight, gestational age at delivery, Apgar scores, and neonatal complications. Diagnoses of HDP and GDM were made based on the clinical criteria established by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology12.

Mental disorder diagnoses in the study population included the following categories according to ICD-1013: schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F20–F29); mood (affective) disorders (F30–F39); neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40–F48); mild mental retardation (F70); behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–F19); and other disorders.

In this study, we investigated the psychotropic drugs taken at the time of admission for delivery. According to the number of psychotropic medications received on admission for the purpose of delivery, the cohort was divided into three groups: no-drugs (177 cases), 1 or 2 drugs (139 cases) and ≥ 3 psychotropic drugs (42 cases). We classified CYP2D6 inhibiting psychotropic drugs into strong (Paroxetine), moderate (Escitalopram, Duloxetine), weak (Chlorpromazine, Fluvoxamine, Sertraline, Venlafaxine), and unspecified groups (Haloperidol, Levomepromazine, Risperidone) according to the Drug Interaction Database14, KEGG database15, and Flockhart cytochrome P450 drug interactions table14 (Supplemental Table 1). NAS was diagnosed using the Isobe score16 (Supplemental Table 2), a modified Finnegan score17 widely used in Japan. Scoring started a few hours after birth and was checked three times a day until discharge. The diagnosis of NAS was confirmed when the Isobe score was 1 or higher in two or more consecutive observations during hospitalization.

Neonatal short-term outcomes such as birth weight, the proportion of LFD and SGA infants, umbilical cord pH, congenital anomalies, NICU admission, respiratory ventilator treatment, and NAS were compared between the groups.

Statistical analysis

Neonatal short-term outcomes were compared between the non-polypharmacy and polypharmacy groups using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Data were presented as medians (ranges) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Multiple comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction. The adjusted significance level (p < 0.017) was used to compare the three groups and determine the probability value of the significance test results for each comparison pair. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software (version 17; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Maternal background

Among the 4,367 deliveries during the study period, 358 (8.2%) were full-term singleton pregnancies complicated by maternal mental disorders (Fig. 1). Maternal backgrounds are summarized in Table 1, with ages ranging from 17–47 years. The cohort included 225 primiparous women (63%). 282 (79%) women were spontaneously conceived, and 76 (21%) with fertility treatment. The median body mass index was 26, and the smoking rate in the cohort was 8.4%.

Maternal characteristics of the mental disorder

Maternal characteristics of mental disorders classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes are shown in Supplemental Table 3. The mental disorders included alcohol use disorder (F1; 1 case, 0.3%); schizophrenia and acute transient psychotic disorder (F2; 45 cases, 13%); depression and bipolar disorder (F3; 146 cases, 41%); anxiety, panic, somatoform disorders, adjustment disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (F4; 170 cases, 47%); anorexia nervosa, eating disorders, sleep disorders (F5; 22 cases, 6.1%); personality and behavioral disorders (F6; 15 cases, 4.2%); mental retardation (F7; 5 cases, 1.4%); pervasive developmental disorder and autism spectrum disorder (F8; 8 cases, 2.2%); attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (F9; 3 cases, 0.8%); and other disorders including epilepsy, narcolepsy, alopecia areata, and paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis (19 cases, 5.3%).

Maternal characteristics of Exposure to psychotropic therapy

A list of psychotropic medications is provided in Table 2. Antipsychotic medications included typical and atypical antipsychotics (n = 81). The antidepressant medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), serotonin antagonists, reuptake inhibitors (SARIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and tetracyclic antidepressants (67 cases). Antiepileptic medication use was recorded in 22 patients, antianxiety medications in 88 patients, and sleep-inducing drugs in 83 patients.

The number of psychotropic medications used are summarized in Supplemental Table 4. Of the 358 patients, 181 (47%) received psychotropic therapy. Ninety patients (25%) reported the use of one psychotropic medication, 49 (14%) used two, 29 (8%) used three, 7 (2%) used four, 5 (1.4%) used five, and 1 (0.2%) used six psychotropic medications.

Obstetric and neonatal outcomes

The obstetric and neonatal outcomes are shown in Table 3. The gestational age at delivery ranged from 37–41 weeks (median, 38 weeks). Vaginal delivery occurred in 253 patients (71%), of which 205 were performed under combined spinal epidural anesthesia. Cesarean sections were performed in 105 cases (29%). Birth weights ranged from 1,850–4,102 g (median, 2963 g). The large-for-date (LFD) and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) groups included 38 (11%) and 30 (8.4%) infants, respectively. The median Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min were 8 and 9, respectively. The pH of the umbilical artery at birth ranged from 6.93–7.48 (median, 7.31). neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, respiratory ventilator treatment, and NAS were performed in 51 (14%), 15 (4.2%), and 9 (2.5%) patients, respectively. Fetal structural abnormalities were observed in 18 of the 358 cases (5.0%).

Comparison of neonatal short-term outcomes between no-drugs, 1 or 2 drugs, and ≥ 3 psychotropic drugs groups

Maternal background did not differ significantly between the groups (Table 1). Obstetric outcomes, including gestational age at birth, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), epidural anesthesia, cesarean section, blood loss, birth weight, LFD, SGA, and Umbilical artery pH, were not significantly different between the groups. Fetal structural abnormalities were observed in 18 of the 358 cases (5.0%). These included 10 cases (5.6%) with no drug exposure, 6 cases (4.3%) with one or two drugs, and 2 cases (4.8%) with three or more drugs. No association was found between fetal structural abnormalities and the number of antipsychotics administered.

However, short-term neonatal outcomes are affected by psychotropic drug intake. The incidence of adverse events was not increased in newborns exposed to one or two maternal psychotropic medications compared to unexposed infants. However, in utero exposure to three or more psychotropic medications was significantly associated with adverse short-term neonatal outcomes such as respiratory ventilator use and NAS compared to those with no-drugs (Table 3).

Most of the infants with respiratory ventilator treatment and NAS had in utero exposure to SSRIs and/or BZs.

Tables 4 and 5 present a list of psychotropic medications administered to patients who required respiratory ventilator support or developed NAS. Most of the infants requiring ventilator therapy or exhibiting NAS had in utero exposure to at least one SSRI or benzodiazepine (BZ). However, we found no consistent trends linking maternal psychiatric diagnoses to their medications and neonatal adverse outcomes.

Respiratory ventilator support was required in 4 of 177 infants (2.2%) who had not been exposed to psychotropic medications in utero, compared to 11 of 181 (6.1%) who had. No cases of NAS were observed in infants without psychotropic exposure, whereas 9 of 181 (4.9%) infants with psychotropic exposure developed NAS. Among those requiring respiratory ventilator support, 8 of 11 patients (72.7%) had in utero exposure to SSRIs, whereas 5 of 9 patients (55.5%) with NAS had similar exposure. Additionally, BZ exposure was noted in 5 of 11 cases (45.4%) requiring ventilator support and in 6 of 9 cases (66.6%) with NAS.

Exposure to psychotropic drugs with CYP2D6 inhibition during pregnancy impairs neonatal short-term outcomes

Almost all patients who required respiratory ventilator management and had NAS were taking psychotropic drugs that inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6) (Tables 6 and 7). Then, we categorized pregnant women who were taking two or more psychotropic drugs into two groups: those receiving psychotropic drugs with CYP2D6 inhibition and those not receiving psychotropic drugs with CYP2D6 inhibition, and compared their neonatal outcomes.

While no significant differences were observed in birth weight, proportions of LFD and SGA infants, or umbilical cord pH, the group exposed to psychotropic medications with CYP2D6 inhibition had significantly lower Apgar scores and higher rates of NICU admission, respiratory ventilator treatment, and NAS (Table 6). When comparing CYP2D6 inhibition by strength, significant differences were found in the Apgar score at 1 and 5 min, though the extent was not clinically meaningful. However, no significant differences were found in NICU admissions, respiratory ventilator treatment, or NAS (Table 7).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of psychotropic medication use during pregnancy on short-term neonatal outcomes, focusing on the implications of non-opioid psychotropic polypharmacy and co-exposure. The incidence of adverse events was not clearly increased in newborns exposed to one or two maternal psychotropic medications compared to unexposed infants. However, in cases involving maternal use of three or more psychotropic medications, a higher frequency of short-term respiratory support and NAS-related symptoms was observed, although the number of such cases was limited. We also found no consistent trends linking maternal psychiatric diagnoses to their medications and neonatal adverse outcomes. Moreover, psychotropic drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 worsened short-term neonatal outcomes in cases of multiple psychotropic medications.

This study found that taking three or more psychotropic medications during pregnancy worsened short-term outcomes in full-term singleton newborns. Numerous studies have investigated the effects of in utero exposure to individual psychotropic medications on obstetric and neonatal outcomes2,3,7,18,19. However, limited research has examined the impact of psychotropic polypharmacy during pregnancy on neonatal or obstetric outcomes, specifically regarding co-exposure or the number of psychotropic medications used8,9,10. Huybrechts et al. reported that in utero exposure to two or more psychotropic medications with opioids doubled the risk of NAS9. They observed that NAS severity was higher in neonates exposed to both opioids and psychotropic drugs compared to those exposed only to opioids. However, their study did not examine neonatal adverse effects beyond NAS or the outcomes of in utero psychotropic polypharmacy without opioid exposure9. As previous studies investigating the effects of non-opioid medication during pregnancy, Sadowski et al. reported higher NICU admission rates in neonates exposed to polytherapy compared to monotherapy (29% vs. 16%) when analyzing second-generation antipsychotics with other psychotropic medications, though this difference was not statistically significant8. Frayne et al. also found higher NICU admission rates in newborns of women with severe mental illness on psychotropic medications but no significant difference between the monotherapy and polytherapy groups for those on antidepressants or antipsychotics10. In addition to these evidences8,10, our study identified infants exposed to three or more non-opioid psychotropic drugs during pregnancy as a high-risk population. As untreated maternal mental health problems pose significant risks, the decision to use psychotropic medications during pregnancy should be made on an individual basis after a thorough risk/benefit analysis. The adverse effects of prenatal exposure to psychotropic drugs on newborns must be balanced against the benefits of mental health treatment for both the mother and infant20. Appropriate neonatal care should be prioritized for infants exposed to three or more psychotropic drugs during pregnancy.

The possible effects of psychotropic drugs, such as antidepressants and antipsychotics, taken during pregnancy on newborns include congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm delivery, respiratory failure, and NAS2,3,21. This study evaluated respiratory ventilator use and NAS as clinical outcomes of neonatal functional adaptation. Although the definition of NAS varies among studies22, NAS is generally characterized by neurological, gastrointestinal, autonomic, and respiratory symptoms in neonates exposed to psychotropic drugs or other substances during the third trimester5,21,23. As respiratory impairment is a symptom of NAS, it is often treated as poor neonatal adaptation syndrome (PNAS) without distinguishing between the two22,24. In this study, we found that most patients with PNAS were exposed to at least one SSRI or BZ during pregnancy, which is consistent with a previous report2. The risk of PNAS after prenatal exposure to antidepressants is well documented, especially for tricyclic antidepressants25, and recent studies have shown that the risk is lower with SSRIs than with tricyclic antidepressants26,27. Exposure to BZs during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of PNAS2. Therefore, it is recommended that BZs be tapered or avoided during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy2, but it is also important to consider the risks of tapering on the pregnant patient’s mental health. For example, if anxiety flares due to attempted BZ tapering, the benefits of continuing to administer BZs may outweigh the neonatal risks. SSRIs and BZs have also been reported to cause PNAS1,2,3,10,23, but the mechanism of PNAS remains incompletely understood. These symptoms may represent psychotropic withdrawal effects similar to those observed in adults following the abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic medications24 and have also been implicated as possible direct toxic effects on the lungs and central nervous system of infants28. Therefore, in the management of newborns after in utero exposure to psychotropic medications, it should be noted that the incidence of PNAS increases as the number of psychotropic medications increases, and attention should also be paid to neonatal adaptation in cases of in utero exposure to SSRIs and/or BZs.

Interestingly, we also found that psychotropic use of CYP2D6-inhibiting drugs adversely affected short-term neonatal outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide evidence regarding the use of psychotropic drugs that inhibit CYP2D6 during pregnancy and their effects on newborns. Some psychotropic drugs exhibit drug-drug interactions that interfere with metabolic pathways29, and it is estimated that 20–25% of all drugs are metabolized, at least partially, via CYP2D630. CYP2D6 plays a critical role in the metabolism of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and drug interactions involving CYP2D6 inhibitors can elevate the plasma concentrations of these medications29,31. Therefore, polypharmacy can lead to harmful drug-drug interactions via CYP2D6. For example, the concomitant use of CYP2D6-inhibiting drugs increases the risk of fall injuries after the initiation of antidepressant treatment30. To date, information on the effects of CYP2D6-mediated metabolism of psychotropic drugs taken during pregnancy in newborns is extremely limited. In our study, almost all infants requiring respiratory ventilation and NAS were exposed to CYP2D6-inhibiting psychotropic drugs in utero, underscoring the need for careful management of such pregnancies and indicating a potential link between in utero exposure to CYP2D6 inhibitors and adverse neonatal outcomes, especially in cases of exposure to multiple psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

In this study, fetal structural abnormalities were detected in 5.0% of the cases, but no association was found between fetal structural abnormalities and the number of antipsychotics administered. This incidence was slightly higher than the reported frequency of fetal structural abnormalities (2–3%) in Japan32. One of the most common maternal factors that can cause fetal structural abnormalities is GDM. The incidence of GDM in our cohort was 11% which was almost the same as the incidence rate for Japan33. Therefore, this may be due to our institution’s role as a referral center for treating fetal abnormalities that require specialized treatment in pediatric surgery or pediatric cardiology after birth. Given the limited number of cases, the relationship between psychotropic medications and fetal anomalies warrants further investigation.

The strengths of this study include the multidisciplinary involvement of obstetricians, psychiatrists, and neonatologists from the same institution, ensuring consistent diagnosis and treatment within a homogeneous Japanese population and minimizing inter-individual variability. Additionally, the single-center design facilitated precise data collection on the types and numbers of prescribed psychotropic medications. However, this study had some limitations. These include its retrospective design, the inherent constraints of a single-center study, and the lack of data on medication use during early pregnancy or patient adherence to prescribed regimens. This study did not consider the specific profile or dosage of each drug. Importantly, in Japan, when a drug administered to the mother crosses the placenta and reaches the fetus, causing respiratory depression in the newborn immediately after birth, this condition is referred to as “sleeping baby” which is equivalent to neonatal depression in Europe and the United States. In cases of the infants exposed to psychotropic medications, it is difficult to strictly distinguish between“sleeping baby”and NAS. However, since this paper is a retrospective design using medical records, we adopted the descriptions recorded in the medical records for these two conditions. Moreover, this study did not include detailed assessments of potential confounders such as opioid use, alcohol consumption, or misuse of prescribed medications. Additionally, smoking status was based on self-reports, which may underestimate actual use, particularly among individuals with mental health conditions. Actually, the frequency of smokers was higher in the group of ≥ 3 medications, although without significance. Finally, the presence or absence of non-psychotropic CYP2D6-inhibiting drugs was not assessed.

Conclusion

In this study, the incidence of NAS-related symptoms was not clearly increased in newborns exposed to one or two maternal psychotropic medications compared to unexposed infants. However, in cases involving maternal use of three or more psychotropic medications, a higher frequency of NAS-related symptoms was observed, although the number of such cases was limited. Careful postnatal monitoring may be warranted in these situations. Particular attention should also be given to neonatal adaptation in infants exposed in utero to CYP2D6-inhibiting psychotropic drugs, as well as SSRIs and BZs, especially in cases of multiple psychotropic medications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Coughlin, C. G. et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes after antipsychotic medication exposure in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 125, 1224–1235. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000759 (2015).

Treatment and management of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum: ACOG clinical practice guideline No. 5. Obstet Gynecol 141 1262-1288, https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000005202 (2023).

Howard, L. M., Megnin-Viggars, O., Symington, I., Pilling, S. & Guideline Development, G. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 349, g7394. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7394 (2014).

Baker, N., Gillman, L. & Coxon, K. Assessing mental health during pregnancy: An exploratory qualitative study of midwives’ perceptions. Midwifery 86, 102690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102690 (2020).

Runkle, J. D., Risley, K., Roy, M. & Sugg, M. M. Association between perinatal mental health and pregnancy and neonatal complications: A retrospective birth cohort study. Womens Health Issues 33, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2022.12.001 (2023).

Boukakiou, R., Glangeaud-Freudenthal, N. M. C., Falissard, B., Sutter-Dallay, A. L. & Gressier, F. Impact of a prenatal episode and diagnosis in women with serious mental illnesses on neonatal complications (prematurity, low birth weight, and hospitalization in neonatal intensive care units). Arch. Womens Ment. Health 22, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0915-1 (2019).

Howard, L. M. & Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatr. 19, 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20769 (2020).

Sadowski, A., Todorow, M., YazdaniBrojeni, P., Koren, G. & Nulman, I. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal exposure to second-generation antipsychotics given with other psychotropic drugs: a cohort study. BMJ Open https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003062 (2013).

Huybrechts, K. F. et al. Risk of neonatal drug withdrawal after intrauterine co-exposure to opioids and psychotropic medications: cohort study. BMJ 358, j3326. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3326 (2017).

Frayne, J. et al. The effects of gestational use of antidepressants and antipsychotics on neonatal outcomes for women with severe mental illness. Aust. N. Z J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 57, 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.12621 (2017).

Morimoto, D. et al. Head circumference in infants with nonopiate-induced neonatal abstinence syndrome. CNS Spectr. 26, 509–512. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852920001522 (2021).

Itakura, A. et al. Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49(5), 53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.15438 (2023).

Janca, A., Ustun, T. B., Early, T. S. & Sartorius, N. The ICD-10 symptom checklist: A companion to the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 28, 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00788743 (1993).

Flockhart, D. A. Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table, 2017).

GenomeNet, <https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/drug/drug_ja.html> (

Isobe, K. et al. Management of neonatal withdrawal syndrome and drug metabolism: Anticonvulsants and psychotropic drugs. Symposium Perinatol. 14, 65–75 (1996).

Finnegan, L. P., Connaughton, J. F. Jr., Kron, R. E. & Emich, J. P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: assessment and management. Addict Dis. 2, 141–158 (1975).

Heinonen, E., Forsberg, L., Norby, U., Wide, K. & Kallen, K. Neonatal morbidity after fetal exposure to antipsychotics: A national register-based study. BMJ Open 12, e061328. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061328 (2022).

Zhong, Q. Y. et al. Adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes complicated by psychosis among pregnant women in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1750-0 (2018).

Hussain-Shamsy, N. et al. The development of a patient decision aid to reduce decisional conflict about antidepressant use in pregnancy. BMC Med. Inform Decis. Mak. 22, 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-022-01870-1 (2022).

Tolia, V. N. et al. Increasing incidence of the neonatal abstinence syndrome in U.S. neonatal ICUs. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2118–2126. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1500439 (2015).

Kautzky, A., Slamanig, R., Unger, A. & Hoflich, A. Neonatal outcome and adaption after in utero exposure to antidepressants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 145, 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13367 (2022).

Dave, C. V. et al. Prevalence of maternal-risk factors related to neonatal abstinence syndrome in a commercial claims database: 2011–2015. Pharmacotherapy 39, 1005–1011. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2315 (2019).

Cornet, M. C. et al. Maternal treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and delayed neonatal adaptation: A population-based cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 109, 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2023-326049 (2024).

Sutter-Dallay, A. L. et al. Impact of prenatal exposure to psychotropic drugs on neonatal outcome in infants of mothers with serious psychiatric illnesses. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 76, 967–973. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09070 (2015).

Ross, L. E. et al. Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 70, 436–443. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684 (2013).

Kieviet, N., Dolman, K. M. & Honig, A. The use of psychotropic medication during pregnancy: how about the newborn?. Neuropsychiatr. Dis Treat 9, 1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S36394 (2013).

Rampono, J. et al. Placental transfer of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants and effects on the neonate. Pharmacopsychiatry 42, 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1103296 (2009).

Otani, K. & Aoshima, T. Pharmacogenetics of classical and new antipsychotic drugs. Ther. Drug Monit. 22, 118–121. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007691-200002000-00025 (2000).

Dahl, M. L. et al. CYP2D6-inhibiting drugs and risk of fall injuries after newly initiated antidepressant and antipsychotic therapy in a Swedish, register-based case-crossover study. Sci. Rep. 11, 5796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-85022-x (2021).

Zhou, S. F. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: Part II. Clin. Pharmacokinet 48, 761–804. https://doi.org/10.2165/11318070-000000000-00000 (2009).

Mezawa, H. et al. Prevalence of congenital anomalies in the japan environment and children’s study. J. Epidemiol. 29, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20180014 (2019).

Iwama, N. et al. Difference in the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus according to gestational age at 75-g oral glucose tolerance test in Japan: The Japan assessment of gestational diabetes mellitus screening trial. J. Diabetes Investig. 10, 1576–1585. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13044 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. I. collected the data, performed the statistical analyses, wrote the manuscript, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. S. M., H. N., K. I., and D. O. contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y. Y., H. G., Y. Yoshimura, K. H., T. S., and K. S. collected the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

The Kitasato University School of Medicine and Hospital Ethics Committee approved the waiver of written informed consent and opt-out informed consent was employed due to the retrospective study design.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Kitasato University School of Medicine and Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: B24-085).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Isohata, H., Miura, S., Yamazaki, Y. et al. The impact of the number of non-opioid psychotropic medications and their co-exposures during pregnancy on short-term outcomes in full-term neonates. Sci Rep 15, 30853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16886-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16886-6