Abstract

The association between various cumulative doses of 5-ARIs and mortality remains unclear. To examine the absolute and time-averaged cumulative doses of 5-ARIs and their association with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or androgenic alopecia (AGA). A nested case-control study was conducted. For each patient who died, up to five controls were matched, based on age, sex, follow-up duration, and date of BPH or AGA diagnosis. The cumulative 5-ARI dose was calculated as the cumulative defined daily dose (cDDD) for the absolute and time-averaged doses over the follow-up period. The study involved 3,084 cases and 14,630 controls. The < 365 cDDDs group and 365–730 cDDDs group had higher mortality rates, whereas the > 5840 cDDDs group had a significantly reduced mortality risk. A similar result was observed for the duration-averaged cumulative doses. Cause-specific analysis revealed higher suicide rates at lower cumulative doses and lower cardiovascular mortality rates at higher cumulative doses. Other cause-specific mortality rates were not statistically significant. The findings revealed a complex relationship between cumulative 5-ARI dosage and all-cause mortality, highlighting the need for careful monitoring of patients using 5-ARIs, particularly concerning the elevated risk of suicide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

5α-Reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), finasteride and dutasteride, are therapeutic options for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and androgenic alopecia (AGA)1,2,3,4. The antiandrogenic mechanisms of 5-ARIs are associated with several established or controversial adverse effects, including decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, infertility, cognitive impairment, prostate and breast cancer, depression, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)5,6,7.

Several studies have investigated the association between 5-ARI use and mortality. In a cohort study involving men with prostate cancer, 5-ARI use was linked with delayed cancer diagnosis and higher cancer-specific and all-cause mortality8. However, another retrospective study9found no association between 5-ARI use in patients with BPH and higher all-cause or cancer-specific mortality compared with that in alpha-blocker (AB) users. Significant differences in all-cause or cancer-specific mortality among 5-ARI users with prostate cancer were similarly not observed in other studies10,11. However, one study12 indicated that 5-ARI intake was correlated with a lower prostate cancer-specific mortality risk and no significant difference in all-cause mortality in healthy adults, compared with that in nonusers.

Unconfirmed associations exist between the use of 5-ARIs and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among patients with benign BPH or prostate cancer, whereas 5-ARI use in AGA has not been considered. Furthermore, limited research exists on the association between 5-ARI use and cause-specific mortality, excluding prostate cancer, with a particular focus on the cumulative dose of 5-ARIs. Given the limited and inconclusive nature of existing research and the widespread use of 5-ARIs for managing BPH or AGA, the aim of this study was to investigate the dose-dependent association between 5-ARI intake and all-cause or cause-specific mortality among patients with BPH and AGA by using a large population-based cohort.

Methods

Data source

We employed the Korea National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC). The NHIS-NSC is a representative, population-based database from the Republic of Korea, prospectively collected between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 201913. Systematic stratified random sampling with proportional allocation based on age, sex, area of residence, and NHIS premium level in 2006 was employed to ensure representativeness. In addition, the Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) system functions as a single-insurer model, providing universal healthcare coverage for all citizens and healthcare providers, thereby allowing prospective data collection and representativeness. The NHIS-NSC originally included NHIS beneficiaries of Korean nationality in 2006 (48,222,537 individuals), and after sampling, 1,024,340 participants remained (2.2% of the Korean population).

The study cohort contains several variables: health insurance classifications (including the NHI and Medical Aid Program), sociodemographic variables, mortality records with causes of death, prescription data, and diagnostic information. Participant follow-up continued until December 31, 2019, unless NHI disqualification (such as emigration) or death occurred.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea (IRB No: [4–2024-0367]) approved this study. The requirement for obtaining written informed consent was waived.

Study design and participants

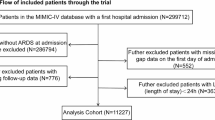

We conducted a nested case-control study, an effective alternative to cohort analysis, particularly for time-dependent variables, rare outcomes, and large sample sizes, involving 92,444 participants diagnosed with BPH or AGA14. To ensure accuracy, we excluded individuals who were potentially misdiagnosed or who obtained prescriptions through illegal proxies, and we included only individuals who had visited outpatient clinics at least three times or were admitted with these diagnoses (Fig. 1). Participants who did not develop BPH or AGA for at least 2 years after cohort enrollment were also excluded to focus on newly diagnosed cases (2-year washout period). Additionally, we excluded individuals diagnosed with BPH or AGA before the age of 40 years to focus our analysis on older adults. Participants covered by the Medical Aid Program were excluded. Furthermore, stringent inclusion criteria were applied, excluding individuals without at least a 30-day prescription of 5-ARI or AB. Eligible participants were followed up from the initial diagnosis date of BPH or AGA until death, disqualification from the NHI, or the end of the observation period on December 31, 2019, whichever occurred first.

Flowchart of the selection process of participants in the nested case-control study. (a) The Korea National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC) database is a longitudinal cohort comprising 1,024,340 participants, equivalent to 2.2% of the Korean population, spanning from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2019. This database encompasses various sociodemographic variables, health insurance classifications, mortality records, medical checkup results, diagnostic information, and prescribed medications. (b) Participants who died following a diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia or androgenic alopecia. (c) Age (± 1 year), sex (male or female), date of the first depression diagnosis (± 30 days), and follow-up duration. Abbreviations: BPH, benign prostate hyperplasia; AGA, androgenic alopecia, 5-ARI, 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

Identification of cases and controls

Participants who died following a BPH or AGA diagnosis were designated as cases, while controls were those still alive (i.e., at risk of mortality) at the time of the matched case’s death. The follow-up period extended from the date of BPH or AGA diagnosis until death. Causes of death were determined according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10).

Matching of cases with controls was conducted among patients with BPH or AGA who were alive at the time of matching. Replacement of matched controls was permitted. The case could serve as its own control. Matching was conducted based on several attributes corresponding to the cases, including age (± 1 year), sex (male and female), the duration of follow-up (exact), and date of the first BPH or AGA diagnosis (± 30 days). We excluded individuals with follow-up durations of less than 1 year to focus on the long-term association between 5-ARI intake and mortality. The index date for the controls was the same as that for the matched cases. Participants with missing data were excluded. Following the application of these criteria, controls were randomly chosen among the matched controls at a 1:5 ratio, and any controls lacking corresponding cases were excluded. A total of 3,084 patients and 14,630 controls were included in this study. Among the 3,084 cases, 65 patients were matched at a 1:1 ratio, 85 at a 1:2 ratio, 81 at a 1:3 ratio, and 113 at a 1:4 ratio.

Exposure

The cumulative use of 5-ARIs, specifically dutasteride and finasteride, was the exposure variable. The cumulative defined daily doses (cDDDs) established by the World Health Organization were used to quantify use of 5-ARI. Prescriptions issued during hospital admissions and outpatient visits from the first 5-ARI prescription date to the index date, irrespective of the reasons for 5-ARI intake, were included in the cDDD calculations. Participants who had consumed 5-ARIs beyond the minimal significant prescription threshold (i.e., 30 cDDDs) were classified as ever-users.

The cumulative dose of 5-ARIs was evaluated in two ways: (1) the absolute cumulative dose and (2) the average cumulative dose over the follow-up period. The absolute cumulative dose throughout the follow-up period was classified into six groups: <365 cDDDs, 365–730 cDDDs, 730–1,460 cDDDs, 1,460–2,920 cDDDs, 2,920–5,840 cDDDs, and > 5,840 cDDDs. Dose classification was also conducted based on quartiles.

We further investigated the association between the average cumulative dose per year (calculated by dividing the cumulative dose by the follow-up period and multiplying by 365.25 days) and mortality. The mean absolute cumulative dose among all participants was 2,681 cDDDs with a standard deviation (SD) of 7,923 cDDDs, and the mean average cumulative dose per year was 491 cDDDs/year with a SD of 1,471 cDDDs/year.

Outcomes

All-cause and cause-specific mortality were the primary outcomes. The deaths of the participants and their causes, categorized according to the ICD-10 guidelines, were identified from the Statistics Korea Death Database. Cause-specific mortality was subdivided based on ICD-10 into categories including all types of cancers, CVDs such as stroke and acute myocardial infarction, completed suicides (intentional self-harm), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), physical trauma (e.g., car accidents, falls), diabetes mellitus (DM), pneumonia, infections, senility, and other causes not listed above. The ICD-10 codes used for the cause-of-death analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Covariates

The socioeconomic characteristics at the index date included the economic status (classified by NHI premium amount: low, middle, and high), area of residence (i.e., capital area, metropolitan area, and province), and NHI insurance type (i.e., employee, and dependents of employees, self-employed, dependents of self-employed). Health status indicators at the index date included physical activity level (i.e., inactive; insufficiently active, less than 600 metabolic equivalents of task [MET] minutes per week; sufficiently active, more than 600 MET-min/week)15,16, alcohol consumption (social drinkers; consuming alcohol less than once a week) and current drinkers; consuming alcohol once a week or more frequently), smoking status (i.e., non-smoker, past smoker, and current smoker), body mass index, annual outpatient visits, and number of hospital admissions. Additionally, previous diagnoses such as chronic kidney disease, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic liver disease, congestive heart failure, DM, cancer, stroke, and any psychiatric disorder were accounted for to adjust for comorbidities. Treatment for BPH included ABs, such as alfuzosin, terazosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, silodosin, and naftopidil, prescribed for at least 30 days, and any type of surgical intervention for the prostate. All major ingredient codes of medications and ICD-10 diagnostic codes used in the analyses are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

A conditional logistic regression model was used to explore the association between 5-ARI intake and mortality. With patients treated as self-referent controls using replacements, unbiased estimations of hazard ratios (HRs) were achieved by using odds ratios derived from conditional logistic regression analyses14,17,18,19. The crude HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and aHRs (adjusted for all covariates) with 95% CIs were also calculated. Trend analyses (P-for-trend) were conducted, considering the cumulative 5-ARI dose categories as ordinal variables, to examine potential dose-response associations within the logistic model20. Subgroup analyses based on age group (below 50s, 60s and 70s, and ≥ 80 years), and type of 5-ARI (i.e., dutasteride or finasteride) were conducted. Although not a matching variable, subgroup analyses were also performed based on the cumulative AB doses during the follow-up period. There was no evidence of multicollinearity as maximum variance inflation factor was 1.28.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted taking into account the alternative minimum cumulative 5-ARI dose criteria (0 cDDDs, 180 cDDDs), the various exclusion criteria regarding the minimum duration between a BPH or AGA diagnosis and death date (no washout period, follow-up duration < 3 years), and different exclusion criteria (any surgical intervention on the prostate or prostate cancer). SAS version 9.4 was utilized for all analyses, and a two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant in all cases.

Results

The inclusion criteria were met by 17,714 participants, comprising 3,084 patients and 14,630 controls (Fig. 1). Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the participants and the crude HRs for each variable. The mean (SD) follow-up period for the cases and controls was 5.7 (3.2) years. The mean (SD) age was 68.5 (8.5) years among the controls and 69.1 (8.8) years among the cases. No female participants were included after applying the exclusion criteria.

Ever-users of 5-ARIs, regardless of the cumulative dose, exhibited a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality by 16.9% compared with that in never-users (aHR, 1.169; 95% CI, 1.049–1.302; Table 2). In particular, a 5-ARI intake of < 730 cDDDs was associated with a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality (aHR, 1.346; 95% CI, 1.177–1.539 in < 356 cDDDs group, aHR, 1.258; 95% CI, 1.040–1.522 in 365–730 cDDDs group). Conversely, participants taking more than 5,840 cDDDs demonstrated a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality than did never-users (aHR, 0.525; 95% CI, 0.413–0.669). An analysis based on the average cumulative dose per year during follow-up indicated that, compared with never-users, individuals taking less than 365 cDDDs/year were at a greater risk of death, whereas users taking more than 1,460 cDDDs/year were at a reduced risk of death (aHR, 0.524; 95% CI, 0.374–0.736). Similar outcomes were observed based on the quantile dose classification and another subdivided classification (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 1), and a no dose-dependent trend was detected (P-for-trend).

Subgroup analyses based on the type of 5-ARIs used (Table 3) revealed that dutasteride and finasteride ever-users had a higher risk of all-cause mortality than did never-users. Additionally, a cumulative dose of < 365 cDDDs for both medications was associated with a higher risk. Higher doses of > 365 cDDDs/year of dutasteride and > 1,460 cDDDs/year of finasteride significantly reduced the risk of all-cause mortality compared with the risk in never-users. Subgroup analysis based on age group and cumulative AB use revealed that these associations were found in aged 60s (Supplementary Table 2). Also, higher mortality risk among non-users and lower morality risk among AB users more than 365 cDDDs.

Table 4 and Supplementary Table 3 detail the cause-specific mortality risks among the 5-ARI users. No significant association existed between 5-ARI intake and mortality due to cancer, COPD, pneumonia, infection, DM, senility, physical trauma. However, a lower mortality due to CVDs was associated with 5-ARI ever-users who had > 5,840 cDDDs of cumulative dose (aHR, 0.260; 95% CI, 0.101–0.669) and > 1,460 cDDDs/year of average cumulative dose (aHR, 0.173; 95% CI, 0.048–0.629), with a marginally significant P-for-trend. Additionally, 5-ARI ever-users and individuals taking < 365 cDDDs/year had a higher risk of mortality due to suicide. The sensitivity analysis results (Supplementary Table 4) were generally consistent with the main outcomes.

Discussion

The aim of this large population-based cohort study was to examine the absolute and time-averaged cumulative doses of 5-ARIs and their association with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in patients with BPH or AGA. We found that the absolute and average cumulative doses of 5-ARIs were associated with higher risks of all-cause mortality at lower doses and lower risks at higher doses. Of note, lower cumulative doses of 5-ARI were associated with increased mortality from suicide, whereas higher doses were associated with decreased mortality from CVDs.

Nonusers of 5-ARIs and users receiving high absolute and average doses could exhibit a lower risk of all-cause mortality in our study, potentially because of the normalization of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels. Previous studies21,22have identified a curvilinear association between DHT levels and all-cause mortality, suggesting the lowest mortality risk at DHT concentrations within the normal range of 50–74 ng/dL. 5-ARIs have an antiandrogenic action and significantly reduce plasma DHT levels more than 70% by targeting types 1 and 2 5α-reductase23,24,25,26. Based on these previous research, it is plausible that DHT levels are more likely to remain within a normal range in two subgroups: 5-ARI non-users and 5-ARI high-cumulative-dose users. This might occur because 5-ARI non-users generally have milder disease severity and therefore do not require 5-ARI treatment, whereas 5-ARI high-cumulative-dose users may suppress DHT levels adequately through consistent and sufficient treatment. By contrast, 5-ARI low-cumulative-dose users may not receive enough 5-ARI to fully suppress DHT levels. However, further prospective research incorporating direct DHT measurements is necessary to elucidate any causal relationship between 5-ARI use and mortality.

Although the statistical significance of 5-ARI use in relation to completed suicide remains unconfirmed27,28,29,30, previous studies have reported increased risks of depressive disorders, depressive symptoms, and self-harm28,31,32,33. Based on our findings, 5-ARI ever users, particularly BPH or AGA patients who used 5-ARIs at low absolute and average cumulative doses, showed an increased risk of completed suicide. This aligns with previous research indicating an elevated incidence of self-harm during the early stages of 5-ARI use (< 1.5 years)28Furthermore, depressive symptoms, including self-harm, which are linked to completed suicide, may contribute to this higher risk34. Plausible mechanisms may explain these findings: 5-ARIs might decrease the levels of neuroactive steroids associated with antidepressant effects and diminish the efficacy of antidepressants, and the capacity of finasteride to penetrate the blood-brain barrier could potentially heighten these risks35,36,37. Further research is needed that takes into account underlying psychiatric conditions and psychotropic medications.

A relationship between 5-ARI use and CVD-related deaths has not been noted in previous studies21,38,39. This study similarly found no statistically significant difference in 5-ARI ever-users and mortality due to CVD. However, our findings suggested a decreased mortality risk among users of high cumulative doses (> 5,840 cDDDs or 1,460 cDDDs/year), correlating with DHT normalization, which has been linked to reduced CVD incidence40. Detailed investigations of plasma and free DHT levels relative to 5-ARI doses are warranted to further elucidate these effects.

This study offers several notable strengths. It is an inaugural investigation examining the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality associated with both absolute and average cumulative doses of 5-ARIs in patients with BPH and AGA. By utilizing a representative population-based cohort, this study benefited from extensive follow-up, robust prescription-based data, and a substantial sample size. This methodology provided critical clinical and policy insights, particularly for primary care physicians and policymakers. Additionally, this study underscores the importance of educating patients about the potential mortality risks associated with 5-ARI treatment.

This study has some limitations. First, although a dose-dependent trend emerged between cumulative 5-ARI dosage and mortality, causality could not be established because a nested case-control design was employed. Second, privacy protection rules restricted access to cohort data, preventing the examination of several diagnoses (e.g., specific psychiatric or infectious conditions) and variables such as marital status and educational level. Despite the rigorous inclusion criteria for BPH and AGA, the risk of misdiagnosis cannot be eliminated. The follow-up period and dates of diagnosis were carefully matched, and adjustments were made to account for the severity of BPH, including surgical interventions and AB intake. However, the possibility remains that higher cumulative doses are indicative of a poorer health status, potentially leading to increased mortality. Finally, the study was limited to Korean participants; thus, additional research is needed to assess whether these findings can be generalized across different racial and ethnic groups.

In conclusion, this study highlights the complex relationship between 5-ARI dosing and all-cause mortality risk in patients with BPH and AGA and indicates increased suicide risk and decreased CVD mortality associated with 5-ARI use. Specifically, among patients with BPH or AGA who received low cumulative doses of 5-ARI, the risk of completed suicide was more than double compared to non-users. Consequently, it is important to closely monitor these individuals—especially at the initial stage or when prescribing low doses—for indicators of suicidal risk, such as suicidal ideation, depressed mood, or prior suicide attempts. In addition, maintaining a consistent and sufficiently high 5-ARI dosage regimen is advisable.

Data availability

The Korea National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC) is a public open-access database. It is based on the health insurance claims data of all Koreans, and the sample cohort is available for public purposes and scientific research. The sample cohort data are available after approval for use by the National Health Insurance Service (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba000eng.do).

References

Kanti, V. et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men - short version. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 32, 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14624 (2018).

Varothai, S. & Bergfeld, W. F. Androgenetic alopecia: an evidence-based treatment update. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 15, 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-014-0077-5 (2014).

McConnell, J. D. et al. Finasteride, an inhibitor of 5 alpha-reductase, suppresses prostatic dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 74, 505–508. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.74.3.1371291 (1992).

McConnell, J. D. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: treatment guidelines and patient classification. Br. J. Urol. 76 (Suppl 1), 29–46 (1995).

Trost, L., Saitz, T. R. & Hellstrom, W. J. Side effects of 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors: A comprehensive review. Sex. Med. Rev. 1, 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/smrj.3 (2013).

Chislett, B. et al. 5-alpha reductase inhibitors use in prostatic disease and beyond. Transl Androl. Urol. 12, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-22-690 (2023).

Hirshburg, J. M., Kelsey, P. A., Therrien, C. A., Gavino, A. C. & Reichenberg, J. S. Adverse effects and safety of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride): A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 9, 56–62 (2016).

Sarkar, R. R. et al. Association of treatment with 5alpha-Reductase inhibitors with time to diagnosis and mortality in prostate cancer. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 812–819. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0280 (2019).

Wallner, L. P. et al. The use of 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors to manage benign prostatic hyperplasia and the risk of All-cause mortality. Urology 119, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.05.033 (2018).

Azoulay, L., Eberg, M., Benayoun, S. & Pollak, M. 5alpha-Reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer-Related mortality in men with prostate cancer. JAMA Oncol. 1, 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0387 (2015).

Knijnik, P. G. et al. The impact of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors on mortality in a prostate cancer chemoprevention setting: a meta-analysis. World J. Urol. 39, 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03202-2 (2021).

Bjornebo, L. et al. Association of 5alpha-Reductase inhibitors with prostate cancer mortality. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.1501 (2022).

13. Lee, J., Lee, J. S., Park, S. H., Shin, S. A. & Kim, K. Cohort Profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, e15 https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv319 (2017).

Essebag, V., Platt, R. W., Abrahamowicz, M. & Pilote, L. Comparison of nested case-control and survival analysis methodologies for analysis of time-dependent exposure. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 5, 1–6 (2005).

World Health Organization, t. Global recommendations on physical activity for health (World Health Organization, 2010).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 1575–1581 (2011). (2011).

Nicholas, P. J. & Boca, R. Statistics for epidemiology. Danvers: Chapman Hall/CRC (2003).

Suissa, S. Brief report: the Quasi-cohort approach in pharmacoepidemiology: upgrading the nested Case–Control. Epidemiology 26, 242–246 (2015).

Vandenbroucke, J. P. & Pearce, N. Case–control studies: basic concepts. Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 1480–1489 (2012).

Maclure, M. & Greenland, S. Tests for trend and dose response: misinterpretations and alternatives. Am. J. Epidemiol. 135, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116206 (1992).

Shores, M. M. et al. Testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in the cardiovascular health study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 2061–2068. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-3576 (2014).

Yeap, B. B. et al. In older men an optimal plasma testosterone is associated with reduced all-cause mortality and higher dihydrotestosterone with reduced ischemic heart disease mortality, while estradiol levels do not predict mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 99, E9–E18 (2014).

Uygur, M. C., Arik, A. I., Altug, U. & Erol, D. Effects of the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride on serum levels of gonadal, adrenal, and hypophyseal hormones and its clinical significance:: A prospective clinical study. Steroids 63, 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-128x (1998). (98)00005 – 1.

Roehrborn, C. G. et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 60, 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01905-2 (2002).

Bhasin, S. et al. Effect of testosterone supplementation with and without a dual 5α-Reductase inhibitor on Fat-Free mass in men with suppressed testosterone production A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 307, 931–939. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.227 (2012).

Russell, D. W. & Wilson, J. D. Steroid 5α-reductase: two genes/two enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 25–61 (1994).

Kim, J. A., Choi, D., Choi, S., Chang, J. & Park, S. M. The association of 5alpha-Reductase inhibitor with suicidality. Psychosom. Med. 82, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000784 (2020).

Welk, B. et al. Association of suicidality and depression with 5alpha-Reductase inhibitors. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0089 (2017).

Garcia-Argibay, M., Hiyoshi, A., Fall, K. & Montgomery, S. Association of 5alpha-Reductase inhibitors with dementia, depression, and suicide. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2248135. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.48135 (2022).

Garcia-Argibay, M., Hiyoshi, A., Fall, K. & Montgomery, S. Association of 5α-reductase inhibitors with dementia, depression, and suicide. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e2248135–e2248135 (2022).

Unger, J. M. et al. Long-term consequences of finasteride vs placebo in the prostate cancer prevention trial. JNCI: J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djw168 (2016).

Altomare, G. & Capella, G. L. Depression circumstantially related to the administration of finasteride for androgenetic alopecia. J. Dermatol. 29, 665–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00200.x (2002).

Doherty, N. et al. Use of 5‐alpha reductase inhibitors and risk of gastrointestinal cancers in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: A population‐based cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 155, 666–674 (2024).

Melhem, N. M. et al. Severity and variability of depression symptoms predicting suicide attempt in High-Risk individuals. JAMA Psychiatry. 76, 603–613. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4513 (2019).

Drury, J. E., Di Costanzo, L., Penning, T. M. & Christianson, D. W. Inhibition of human steroid 5beta-reductase (AKR1D1) by finasteride and structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19786–19790. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C109.016931 (2009).

Finn, D. A. et al. A new look at the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride. CNS Drug Rev. 12, 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x (2006).

Lambert, J. J., Cooper, M. A., Simmons, R. D., Weir, C. J. & Belelli, D. Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABA(A) receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 (Suppl 1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009 (2009).

Ayele, H. T. et al. The cardiovascular safety of Five-Alpha-Reductase inhibitors among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: A Population-Based cohort study. Am. J. Med. 136, 1000–1010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.06.021 (2023).

Hsieh, T. F. et al. Use of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors did not increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia: a five-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 10, e0119694 (2015).

Swerdloff, R. S. et al. Biochemistry, physiology, and clinical implications of elevated blood levels. Endocr. Rev. 38, 220–254. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2016-1067 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of the Institute of Health Services Research at Yonsei University (Seoul, Republic of Korea) for their insightful comments and Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for providing English language editing assistance.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ECP: conceived, designed, directed the study, critically revied the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for final content. JK: conceptualized the study, conducted statistical analysis, interpreted the data, wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and revised the manuscript. JK and SYJ conducted statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. ECP: responsible for the revision of the manuscript. All authors: participated sufficiently in the work, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea (IRB No: [4-2024-0367]) approved the study. The IRB, recognizing the sole academic nature of the investigators’ database access and the absence of personally identifiable information utilization, exempted the need for obtaining written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data sharing statement

The Korea National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC) is a public open-access database. It is based on the health insurance claims data of all Koreans, and the sample cohort is available for public purposes and scientific research. The sample cohort data are available after approval for use by the National Health Insurance Service (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ab/bdaba000eng.do).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Jang, SY. & Park, EC. Differential association between cumulative dose of 5α-reductase inhibitors and mortality. Sci Rep 15, 10962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95583-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95583-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of life’s crucial 9 score with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a cross-sectional study

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2025)