Abstract

This study examines the emotional dynamics of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners in higher vocational colleges (HVCs) under Small Private Online Course (SPOC)-based blended learning settings. A survey of 1250 EFL students from six HVCs was conducted to explore the impact of SPOC-based blended learning environment adaptability, SPOC-based blended learning style adaptability, and persistence of online learning cycles on students’ learning emotions. Results indicate positive emotions and high adaptability to SPOC-based blended learning, with no significant learning fatigue. Emotional factors varied based on grade, gender, and majors. In addition, a regression model is proposed to observe the factors affecting SPOC-based blended learning emotions. The findings contribute empirical evidence and research references to enhance teaching efficiency for EFL students in HVCs using SPOC-based learning, and promote the integration and innovation of online and offline teaching modes based on SPOC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Emotions are an integral component of educational environments1, profoundly influencing students’ motivation, learning strategies, attention, and self-regulation2,3. Emotion, as a complex subjective experience, can be influenced by numerous factors, thereby shaping learners’ educational journey with a spectrum of positive and negative emotional responses. In recent years, there has been a surge in research interest concerning learning emotions. Various learning models and theories have consistently affirmed the pivotal role of emotions, not only in traditional face-to-face classrooms4,5 but also in the realm of online learning1,6,7,8,9. Positive emotions have been found to stimulate learning interest, enhance efficiency, prolong learning duration, and foster creativity, whereas negative emotions have an inhibitory effect on these outcomes5.

Despite the proliferation of research in this area, a notable gap persists in our understanding of the learning emotions of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students within a blended learning environment based on Small Private Online Courses (SPOCs) in Higher Vocational Colleges (HVCs). SPOCs represent an innovative integration of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) with traditional face-to-face classrooms, aiming to achieve high learning efficiency in higher education10,11,12. However, in the context of SPOC-based blended learning, where teaching and learning are separated by time and space, students’ learning emotions are subjected to a complex array of factors that can undermine the intended impact of this learning model.

The present study addresses this gap by exploring the overall level of learning emotions of EFL students and investigating the factors that influence their learning emotions in a SPOC-based blended learning environment in HVCs in China. By examining the adaptability to SPOC-based blended learning environments, the adaptability of SPOC-based blended learning styles, and the persistence of online learning cycles, this research aims to provide insights into the emotional dynamics of EFL learners in this unique educational setting. Understanding these factors is crucial for optimizing teaching strategies, enhancing learning outcomes, and promoting the effective integration and innovation of online and offline teaching modes based on SPOCs. This study aims to address the following research questions:

-

(1)

What are the overall levels of learning emotions among EFL students in HVCs, and how do positive and negative emotions compare?

-

(2)

How do learning emotions vary among EFL students in HVCs across different academic levels, genders, and majors?

-

(3)

What factors are significantly correlated with the learning emotions of EFL students in HVCs?

To bridge this gap, the current research investigates the emotional landscape of EFL learners in SPOC-integrated settings, offering actionable insights to refine pedagogical strategies and foster more adaptive, emotionally intelligent learning ecosystems within vocational education frameworks.

Literature review

The traditional face-to-face learning environment is based on human-to-human interaction, where students are physically present in the classroom13. In this context, Hascher2 reported that the learners themselves, along with other key figures in the learning environment such as teachers and peers, as well as the learning tasks, are essential sources of both cognition and emotion in physical classroom learning. Fang and Xia14, using Pekrun’s academic emotion theory3(2002), explored the main types of academic emotions experienced by first-year English majors in Content-based Instruction classes, as well as the classroom environment factors affecting academic emotions, and the relationship between them, using a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods. The results showed that academic emotions can be divided into four dimensions: positive high arousal emotion, positive low arousal emotion, negative high arousal emotion, and negative low arousal emotion. Classroom environment factors mainly include teacher guidance, expectations, feedback, student autonomy in the classroom, competition, cooperation, teacher-student relationship, and textbooks. Differently, Laukenmann et al.15 conducted a study using both quantitative and qualitative methods to examine 24 eighth-grade physics classrooms in Germany. Their results not only revealed that positive emotions are more critical in the acquisition phase than in the practice phase, and anxieties play an ambiguous role in the practice phase, but also provided indications that joy about learning and interest are frequently linked to successful learning processes, rather than only to the nature of the subject matter.

Some researchers reported that the students generally demonstrated a positive attitude to their learning emotions in online learning environments7,16,17,18. Concerning factors affecting learning emotions in online environment, some research indicates that factors influencing learning emotions in online learning environments can be divided into two categories: endogenous and exogenous factors. Endogenous factors include learners’ expectations and motivation, while exogenous factors include technical quality, course content, and interpersonal interaction19. Recent comparative studies have further nuanced this framework by highlighting modality-specific emotional responses. For instance, Li et al.20 found that Chinese EFL learners in fully online environments exhibited significantly higher anxiety and lower emotional engagement compared to offline counterparts, particularly related to technical challenges and reduced social presence. Similarly, Li et al.21 emphasized that instructional approach profoundly shapes learner engagement, with online-only formats correlating with lower persistence and higher disengagement rates than blended or in-person models. These findings underscore the critical role of instructional design in mitigating negative emotions often associated with purely online learning22.

Specifically, studies have shown that online learners may experience negative emotions such as frustration, nervousness, anxiety, and shyness due to factors such as unstable network, tedious operation process, imperfect system function, and outdated information22. In contrast, positive emotions such as excitement and pride can arise from experiencing new learning styles, having more initiative, and completing stage tasks23,24. Additionally, students may face challenges in adapting to the new social and communication skills required for online learning, leading to anxiety and feelings of fear and alienation25. Zhao et al.19 found that course quality is the most important factor triggering positive emotions of online learners at different learning stages, while the ease of use of the technology platform is an important influencing factor for negative emotions in the pre- and mid-learning period. Furthermore, the impact of interpersonal interaction frequency on emotions increases significantly as the learning process progresses19; similarly, Zembylas et al.26 reported that the issues of social and emotional communication and contact emerge as critical in the exploration of adult learners’ emotions in the context of online learning. Finally, research indicates that the affective attachment that students develop with teachers also influences their learning emotions27,28. Song et al.7 conducted a survey of 1,606 junior high school students in 13 provinces and cities in China and found that students adapted well to the home learning environment and online learning methods without experiencing obvious learning fatigue; besides, the various influencing factors exhibited significant differences among grade levels, genders, and urban-rural areas. Overall, understanding the factors that affect learning emotions in online learning environments is crucial for educators and course designers to provide supportive and effective learning experiences for students.

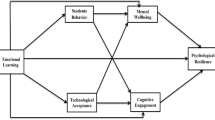

Blended learning—defined as the strategic integration of online and face-to-face instructional methods29—represents a distinct pedagogical approach compared to fully online learning. While online learning typically relies on asynchronous, self-directed activities, blended learning combines these with synchronous, interactive face-to-face sessions. This blended model enhances social presence (e.g., immediate feedback, peer collaboration) and provides scaffolding for complex tasks30, which may explain its documented advantages in emotional engagement. For example, Li et al.21 demonstrated that blended approaches outperform online-only models in maintaining learner motivation and reducing anxiety, aligning with Acosta-Gonzaga and Ramirez-Arellano’s31 finding that positive emotions are more pronounced in blended contexts than traditional face-to-face settings. The distinction lies in blended learning’s capacity to leverage technology for flexible content delivery while retaining the socio-emotional benefits of in-person interaction. This duality addresses key limitations of online learning—such as transactional distance32 and isolation33—thereby creating a more adaptive and emotionally supportive environment. By examining EFL learners in SPOC-based blended contexts, this study extends prior work focused on undergraduate populations to explore how HVCs learners navigate the emotional complexities of integrating career-focused education with work-integrated learning in digital environments.

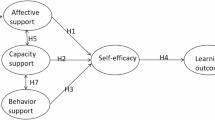

Emotional support is crucial in all types of learning, especially in blended learning programs34. In blended learning environments, students generally exhibit a positive tendency in their learning emotions35,36,37. Specifically, Acosta-Gonzaga and Ramirez-Arellano31(2021) proposed a conceptual model that examined the relationships between motivation, emotions, cognition, and metacognition in a blended context. They found that positive emotions played a significant role in blended learning, but not in face-to-face learning. Ye38 reported that the factors of influencing undergraduate students majoring in industrial design in flipped classrooms included tear and immense pressure, fear of insufficient self ability, not knowing how to apply the knowledge learned in school, and nervousness in presenting on stage. Yang et al.9 investigated the impact of blended teaching on college students’ academic emotions and learning autonomy. Their research aimed to improve college students’ academic emotions and learning autonomy and provide new methods and ways for the reform of modern higher education. The conceptual model proposed by Ramirez-Arellano et al.39 indicated causal and reciprocal relationships between motivation, emotions, cognition, metacognition, and students’ academic achievements in a blended context. Other studies have also compared the effects of students’ emotions and motivation in different learning contexts. For instance, Butz et al.40 found that online students reported higher levels of anger and anxiety than face-to-face students, while face-to-face students had higher levels of boredom than online students. In contrast, Daniels and Stupnisky41 found no differences in the emotions experienced by students in online and face-to-face contexts. Iqbal et al.42 examined the direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and study habits in blended learning environments and they found emotional intelligence included self-awareness, self-motivation, and the regulation of emotion. In summary, emotional support is crucial in blended learning environments, and positive emotions play a significant role in blended learning. Various studies have investigated the impact of blended teaching on students’ academic emotions and learning autonomy and have compared the effects of students’ emotions and motivation in different learning contexts.

The combination of internet formation and education led to a widespread adoption of SPOC-based blended learning models across educational institutions, including HVCs43. This sudden change has significantly impacted students’ learning environment, style, and learning persistent cycle, and it is important to understand how these changes affect their emotional state in SPOC-based blended learning environments. Besides, EFL learners experience very complicated learning emotions over language learning, and the factors affecting EFL learners’s learning emotion need to be explored44. Moreover, previous studies have primarily focused on undergraduate students, whereas this study examines EFL students in HVCs who receive a combination of career education and work-integrated learning as part of their formal studies11,45. Hence, this study aims to examine the factors influencing SPOC-based blended learning emotions of EFL students from HVCs, filling a gap in the literature.

Methodology

Research participants

The participants were selected using purposive sampling, and quantitative data were collected and analyzed from EFL students who studied the compulsory course HVCE. This course was carried out under a SPOC-based blended learning model in six HVCs (three public colleges and three private colleges) and was only offered to first-year students. Among the 1,250 participants, the sample consisted of 543 (43.4%) freshmen, 439 (35.1%) sophomores, and 268 (21.4%) juniors. In terms of gender, 640 (51.2%) participants were male, and 610 (48.8%) were female. Additionally, 710 (56.8%) participants studied science, while 540 (43.2%) studied liberal arts. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Guangdong Mechanical and Electrical Polytechnic, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The English proficiency of these participants was primarily evaluated using the Practical English Test for Colleges (PRETCO), a standardized assessment specifically designed for vocational college students, with a full score of 100 and a passing score of 60. Among them, 405 participants scored above 70 points, 580 scored between 60 and 70 points, and 265 failed to meet the passing threshold. This distribution indicates that the majority of participants possessed adequate foundational English competencies.

Research tools

Emotional influences measurement tool

The Emotional Influence Measurement Tool, adapted from the Classroom Emotions Scale (CES) by Titsworth et al.46, is a 10-item scale used to assess adaptability in both blended learning environments and blended learning styles. Specifically, questions 1–4 and 8–10 are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely agree) to 5 (completely disagree), while questions 5–7 are scored in reverse. This tool evaluates two dimensions: learning environment adaptability (four questions) and blended learning style adaptability (six questions). Higher scores indicate greater adaptability to online learning compared to offline learning, and to the blended learning method, respectively.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the scale, a psychometric analysis was conducted with a sample of 135 EFL students. The sample size was chosen based on practical considerations, such as time and resource constraints, while still ensuring a representative and statistically significant subset of the larger population. The analysis resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.815 for the overall scale, 0.807 for blended learning style adaptability, and 0.822 for learning environment adaptability, confirming the scale’s reliability. Validity analysis using Amos 21.0 also produced favorable results, demonstrating the tool’s good structural validity. Example items from the scale include “I feel comfortable learning online” and “I prefer blended learning over traditional classroom learning.”

Additionally, the survey on the persistence of online learning cycles in a SPOC-based learning context included three questions: one measuring online self-learning frequency (on a scale from “1 day” to “7 days”), one assessing online self-learning intensity (ranging from “less than 2 hours” to “more than 5 hours” per day), and one evaluating learning willingness (indicating voluntary engagement in learning the course HVCE with response options of “often,” “sometimes,” or “never”).

Emotional level measurement tool

The Positive Negative Affect Inventory (PNEI), originally compiled by Watson et al.47 and further developed and standardized by Huang et al.48, was adapted to measure emotional level. This 20-item scale consists of two sub-scales: positive and negative emotions, each comprising 10 adjectives describing specific emotions. Participants were asked to rate their experience of each emotion on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost none) to 5 (very much) based on their actual situation in the last one or two weeks. A higher score on the positive/negative emotion sub-scale indicates a greater experience of positive/negative emotions. If the positive emotion score exceeds the negative emotion score, it indicates an overall positive emotion level, and vice versa. The total score of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.819, with coefficients of 0.879 and 0.906 for the positive and negative emotion sub-scales, respectively, indicating the scale’s reliability. Example items from the scale include “happy” and “sad.” CFA results confirmed the two-factor model (positive/negative affect) with excellent fit. Standardized factor loadings for all items were high (0.73–0.91) and significant (p < 0.001), demonstrating strong structural validity.

Statistical methods

The statistical analyses in this study were conducted using the widely-used SPSS 26.0 software package in the field of social science research. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 to indicate statistical significance. Descriptive analysis was employed to summarize and describe the level of blended learning emotions among EFL students and the characteristics of the data. Independent sample t-tests were used to assess gender differences in the frequency of online self-learning. One-way ANOVA was utilized to examine grade differences in factors affecting SPOC-based blended learning emotions. Correlation analysis was performed to determine the correlation coefficients between demographic variables, blended learning environment adaptability, blended learning style adaptability, persistence of online learning cycles, and EFL students’ online learning emotions. Multiple linear regression analysis was applied to identify the factors influencing students’ blended learning emotions. These statistical methods enhance the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Data collection procedures

The data collection process involved implementing a SPOC-based blended learning model, which comprised two components: online self-learning and offline teacher-led instruction and Q & A sessions. For the HVCE course, students engaged in two two-hour classes per week, totaling four hours of instruction over a 16-week semester. Throughout the semester, students spent 16 weeks on online self-learning and participated in 32 h of offline centralized teaching, combining offline class hours and online self-learning. To measure students’ learning emotions, a questionnaire survey was administered between December 11st and 26th, 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their legal guardians. The survey was conducted across six HVCs in Guangdong province, China, resulting in the collection of 1,400 questionnaires. The data from questionnaires where the answer time was less than one minute and all answers were the same option were excluded. This left us with 1,250 valid questionnaires, yielding an effective response rate of 89.2%.

Results

The overall level of learning emotions of EFL students from HVCs

This study examined the learning emotions of EFL students in HVCs using a survey. Overall, the results indicated positive emotions among the students, with higher scores in positive emotions (27.95 ± 6.92), reflecting happiness, focus, and energy. Negative emotions scores were lower (20.96 ± 7.59), indicating fewer negative emotions. Further analysis revealed interesting findings summarized in Table 1.

Regarding academic levels, junior students exhibited significantly higher negative emotions compared to sophomore students, who, in turn, had higher negative emotions than freshmen students (P < 0.01). Female students had significantly higher negative emotions scores than male students (P < 0.01). Additionally, female students showed higher overall emotional positivity compared to males (P < 0.05), and freshmen students had higher overall emotional positivity than sophomore and junior students (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). These findings suggest variations in emotional states among different academic levels and genders.

Furthermore, positive emotions of liberal arts students were significantly higher than those of science students (P < 0.05), indicating the influence of academic discipline on emotional states among EFL students.

Overall, the study provides valuable insights into the emotional state of EFL students in HVCs. The findings suggest that gender, grade, and major are important factors that influence emotional states.

Group difference analysis of factors affecting learning emotions of EFL students

Gender differences

Table 2 shows that the difference between males and females in their blended learning environment adaptability is statistically significant (t = -2.805, P < 0.01). Females were more adapted to the face to face offline teaching with their classmates and teachers (5. 48 ± 2.17), while males preferred to study online self-learning setting (4. 83 ± 2.27). For blended learning style, the gender difference were not statistically significant, and both males (15.10 ± 18.40) and females (15.45 ± 4.31) thought that SPOC-based blended learning had no effect on learning efficiency and concentration (P > 0.05), and could adapt to learning style under SPOC-based blended learning.

Concerning the results of the persistence of online learning cycles dimension. About one thirds of students, 388 (31.04%), learned online for 1 day a week, while 320 (25.6%) and 190 (15.2%) studied for 2 and 3 days respectively as it shows from Table 3. In terms of daily study duration, 385 (30.8%) studied online for six or more hours, 402 (32.1%) studied for 5–6 h, 102 (8.1%) studied for 4–5 h, 161 (12.8%) studied for 3–4 h, and 200 (16%) studied online for less than 2 h per day.

Table 4 shows the independent sample t-test indicated a statistically significant difference in the online learning frequency between genders (t = -2.401, p < 0.05), with female students (4.31 ± 0.62) having a significantly higher online learning frequency than male students (5.28 ± 0.52). However, there was no significant difference between male and female students regarding online self-learning intensity and learning willingness (t = -1.98, P > 0.05).

Grade differences

The ANOVA results indicated that there were statistically significant differences between the three grades concerning their blended learning environment adaptability (F = 4.708, P < 0.01) and blended learning style adaptability (F = 4.208, P < 0.001). In terms of blended learning environment adaptability, there was a significant difference between freshmen and sophomores. Specifically, sophomores demonstrated significantly higher adaptability to the online self-learning environment (5.28 ± 2.09) compared to freshmen (4.30 ± 2.08, P < 0.01). Additionally, regarding blended learning style adaptability, there were significant differences between freshmen and juniors, as well as between sophomores and juniors. Freshmen showed significantly higher adaptability to blended learning style adaptability (17.48 ± 4.01) compared to juniors (15.14 ± 4.70, P < 0.001), while sophomores (18.28 ± 4.78) also demonstrated significantly higher adaptability to blended learning style compared to juniors (15.14 ± 4.70, P < 0.001). (See Table 5).

There were statistically significant differences in the frequency and intensity of online self-learning among the three grades. The frequency of online learning was the highest in the freshmen students (5.45 ± 0.69), followed by sophomore students (5.21 ± 0.44), and lowest in junior students (5.18 ± 0.68). The online learning intensity was also the highest in the freshmen students (4.84 ± 1.28), followed by the sophomore students (4.63 ± 1.28), and lowest in the freshmen students (4.27 ± 1.28). Differences in both frequency and intensity were significant between all pairs of grades (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001). However, there was no statistically significant difference in learning willingness among the grades (P > 0.05) (See Table 6).

Major differences

As for the two dimensions of blended learning environment adaptability and blended learning style adaptability, liberal arts students and science students’ blended learning emotions were different. There is no statistical difference between the performance of liberal arts and science students on the two dimensions of blended learning environment adaptability and blended learning style adaptability. Regarding to the blended learning environment adaptability, both liberal arts students (4.98 ± 2.34) and science students (4.78 ± 2.47) preferred to study in a online self-learning environment as opposed to studying face to face offline learning setting. In terms of blended learning styles adaptability, both liberal arts (17.10 ± 4.90) and science students (18.80 ± 4.82) were more likely to preferred to the online self-learning method, and science students were more likely to accept online self-learning setting than those in liberal arts students.

As for the persistence of online learning cycles dimension from Table 7, there were statistically significant differences in online learning frequency and learning willingness, and non-statistically significant differences in intensity of learning. The online self-learning frequency was significantly higher for liberal arts students (5.20 ± 0.52) than for science students (5.12 ± 0.59, p < 0.05). The learning willingness in blended learning environment was significantly higher in liberal arts students (2.38 ± 0.65) than that in science students (2.09 ± 0. 61, p < 0.001).

Regression analysis of the factors influencing students’ learning emotions

The correlation analysis was utilised to obtain the correlation coefficients between demographic variables, blended learning environment adaptability, blended learning style adaptability, persistence of online learning cycles, and EFL students’ blended learning emotions. The results are presented in Table 8.

One of the research purposes was to establish a regression equation that could predict EFL students’ blended learning emotions based on several independent variables. Using the stepwise regression method in multiple linear regression analysis, the researchers identified the most significant factors that correlated with blended learning emotions, which included blended learning environment adaptability, blended learning style adaptability, and learning willingness. In the first step of the analysis, gender and grade were entered as control variables. After identifying and removing 15 outliers found in case diagnosis, the researchers selected the best regression model. The Durbin-Watson (D-W) value of 2.038 (between 1.8 and 2.2) in Table 9 confirmed that the data were independent. The adjusted R-squared value of 0.325 indicated that the regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in the data. Additionally, the analysis of variance showed that the F-value for the regression equation was 189.473, with a P-value less than 0.001, which indicated that the model was statistically significant. The predictor variables are constant, grade, gender, blended learning style adaptability, blended learning environment adaptability, and learning willingness.

Table 10 shows the results of variance for the independent variables in the regression equation. The variables exhibited low variances and variance inflation factor (VIF) values close to 1, demonstrating minimal collinearity. All independent variables had P values below 0.01, signifying their statistical significance as predictors of blended learning emotional level. The regression equation derived from these findings is as follows: blended learning emotional level = -5.985–1.106 × grade − 1.405 × gender + 1.198 × blended learning style adaptability − 0.507 × blended learning environment adaptability − 1.020 × learning willingness. Notably, in this study, the values 1, 2, and 3 represent freshmen, sophomores, and juniors, respectively, while 1 represents male students and 2 represents female students. Further details on scoring methods for blended learning style adaptability, blended learning environment adaptability, and learning willingness can be found in the previous tools.

Discussion

Building on self-determination theory (SDT) frameworks highlighted by Wang and Liu49, which emphasize the role of autonomous motivation in engagement, this study alighs with previous research by Kim and Ketenci16, Kuo et al.17, Pekrun et al.50,51, and Song et al.7, this study found that EFL students had a positive overall learning emotion, which resonates with Liu et al.‘s52 distinction between global and specific levels of foreign language boredom, suggesting that students may experience situational disengagement without overall negative affect. Unlike Acosta-Gonzaga and Ramirez-Arellano’s31 findings, which indicated a positive attitude towards blended learning but not offline learning, this study observed a positive overall mood among EFL students in both online self-learning and offline learning within the SPOC-based blended learning setting. Similarly, Daniels and Stupnisky41 found no differences in emotions between online self-learning and offline contexts. The unique contextual factors of Chinese vocational colleges significantly influenced these outcomes. Firstly, the institutional emphasis on the PRETCO test, required for graduation, cultivates a utilitarian learning orientation that diminishes student resistance to blended teaching formats by prioritizing practice-oriented outcomes. Secondly, China’s high internet penetration rates coupled with vocational colleges’ early institutional adoption of blended learning have jointly developed a mature digital learning ecosystem. This contrasts sharply with educational contexts where online learning remains novel, as observed by Butz et al.40, creating natural adaptability for technology-integrated pedagogy in these institutions. Contrary to the results of Butz et al.40, who reported higher levels of anger and anxiety in online learning compared to offline learning, and higher levels of boredom in ofline learning compared to online learning, this study revealed that EFL students not only adapted well to the SPOC but also to the blended learning style. Several factors may explain these findings.

Firstly, the widespread adoption of the internet in China and the prior exposure of HVCs students to blended learning before enrollment have contributed to their familiarity and acceptance of this learning approach43. Additionally, the practice of pre-class online preview and post-class review has become increasingly accepted by students compared to traditional face-to-face teaching methods. Furthermore, female EFL students in HVCs tend to exhibit a higher overall emotional response to SPOC-based blended language learning, possibly linked to gendered perceptions of teacher support, as Liu et al.53 found male students report higher emotional support, yet female students may internalize such support more deeply.

Moreover, offline teacher-led instruction and Q & A sessions provide face-to-face communication opportunities, enabling better student focus, timely guidance, and emotional support. Offline classroom interaction enhances classroom flexibility and deepens students’ understanding of knowledge. In contrast, online self-learning requires students to take more autonomy in their learning7. Although teachers may have less attention and interaction during students’ online learning due to class size and extensive learning content, online self-learning offers unique advantages such as maximizing the use of online educational resources, revisiting instructional videos for knowledge consolidation, and facilitating text-based communication, allowing students to express their knowledge and viewpoints more confidently54. Research suggests that students maintain a positive attitude towards online self-learning, perceiving no significant negative impact on lecture efficiency, concentration, or teacher-student interaction. Overall, students are able to adapt well to online self-learning.

Similar to Song et al.7, this study found that second-year students were more adaptive to face-to-face offline learning, while first-year students showed greater adaptability to online self-learning. This decline in digital tool usage across academic years may reflect two interrelated dynamics. First, a “novelty effect” suggests freshmen’s initial enthusiasm for technology-enhanced learning diminishes as academic pressures intensify in subsequent years, redirecting focus to core curriculum demands. Second, escalating curricular complexity in junior years—where courses demand deeper analytical and critical thinking skills—might lead students to perceive traditional face-to-face instruction as more effective for navigating complex problem-solving scenarios than digital platforms alone.

Additionally, sophomores demonstrated significantly higher adaptability to face-to-face offline learning compared to freshmen, and both freshmen and sophomores exhibited higher adaptability to online self-learning than juniors. Moreover, freshmen had significantly higher online self-learning frequency and intensity compared to sophomores and juniors. In terms of gender differences, females showed higher adaptability to face-to-face offline learning but lower online self-learning frequency compared to males. Furthermore, liberal arts students had higher online self-learning frequency and willingness to engage in SPOC-based blended learning than science students.

The higher adaptability of sophomores and females to the learning environment may be attributed to their greater maturity as young adults. Sophomore students are generally more mature compared to freshmen, and females tend to exhibit greater maturity than males. In contrast, junior students may face difficulties in adapting to online self-learning, possibly due to the specialized nature of third-year courses, which differ from earlier grades, along with the pressures of career development. The persistence of the online learning cycle, including the number of days and duration of online learning, is influenced by the college’s course schedule and individuals’ voluntary participation. Freshmen students, who are often more self-motivated in their studies, displayed higher online learning frequency and intensity compared to sophomores and juniors, indicating a greater willingness to engage in online self-learning.

Regarding majors, liberal arts students, particularly females, demonstrated higher online self-learning frequency due to their generally higher self-regulation compared to science students. However, liberal arts students faced more difficulty adapting to online self-learning, and their learning willingness was lower than that of science students. Conversely, liberal arts students were more likely to adapt to online self-learning, and their learning willingness was significantly higher than that of science students. The paradoxical finding that liberal arts students exhibited higher online self-learning frequencies yet contradictory adaptability levels may stem from two interrelated factors. First, the content alignment between SPOC platforms and disciplinary curricula appears critical: HVCs’ SPOC resources often prioritize language-focused exercises (e.g., PRETCO-style drills), which naturally align with liberal arts’ communication-centric curriculum, whereas science majors encounter greater mismatches when encountering specialized technical terminology in digital formats. Second, differing self-regulation capacities and support needs come into play—while liberal arts students’ proficiency in text-based discussions and independent reading makes them suited to asynchronous online modules, science students’ mastery of technical concepts often requires offline scaffolding like lab simulations and instructor-led problem-solving sessions, creating divergent adaptation patterns despite comparable access to digital tools.

The multiple linear regression analysis of this study revealed that several factors influence students’ emotional response to blended learning based on SPOC. These factors include grade, gender, blended learning style adaptability, blended learning environment adaptability, and learning willingness. Here is a detailed analysis of these factors.

First, previous studies have shown that learners’ emotions are influenced by the flexibility, ease of use, and stability of the online learning platform10. Therefore, administrators should carefully select a high-quality online learning platform and ensure its functionality before implementing blended teaching policies. This will prevent potential negative effects of platform shortcomings and foster positive emotions among learners. Consistent with prior research, reducing negative emotions in online distance learning requires adaptability to the learning environment, improved communication with peers and instructors, and enhanced learning intensity and frequency3,4,9,32,38.

The regression model also identified grade, gender, and major as significant factors affecting EFL students’ emotional levels in blended learning. Consistent with previous research, gender differences were observed, with females displaying stronger negative emotions than males7,26,55. Additionally, students’ majors were found to be related to blended learning, providing valuable insights into the emotional factors associated with online learning. Both liberal arts and science students show a preference for online learning over offline teaching, likely due to their familiarity with online learning methods and the autonomy and flexibility it offers55.

Furthermore, students’ adaptability to the offline learning environment was found to impact their emotions. There was a slightly positive correlation between students’ adaptability to the online self-learning environment and their emotions, likely due to their prior experience with online learning before enrolling in HVCs. Learning willingness emerged as not only a predictor of emotions but also a reflection of an individual’s emotional state. Students with stronger online learning willingness tended to exhibit more positive emotional expressions. This aligns with studies that found positive attitudes towards online learning to be associated with higher satisfaction, engagement, and motivation18,31,56.

Lastly, online learning frequency and intensity can impact negative emotions. Excessive online learning, such as spending excessive time on computers or mobile devices, was associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and sleep problems among college students57,58,59. These findings offer valuable insights for educators and policymakers aiming to enhance students’ emotional experiences in blended learning environments.

Regression analysis identified demographic variables—grade level, gender, and academic major—as significant predictors of students’ emotional engagement. However, contextual factors related to institutional SPOC support emerged as equally critical yet under-examined determinants. For instance, China’s collectivist educational culture, characterized by structured learning environments, may explain the absence of widespread negative affective responses observed in comparable international studies40, suggesting cultural context moderates technology integration outcomes in ways that current predictive models have yet to fully incorporate.

The findings of this study offer actionable implications for designing SPOC-based blended English courses in HVCs, particularly in addressing learner emotional dynamics and contextual adaptability. First, the overall positive emotional orientation of EFL students toward blended learning suggests that curriculum developers should prioritize practice-oriented, low-resistance learning activities aligned with institutional goals like PRETCO preparation. For instance, integrating gamified language drills or interactive video modules could sustain student engagement while reinforcing utilitarian learning objectives. Secondly, grade-level differences in adaptability highlight the need for stratified pedagogical strategies: freshman-focused courses might emphasize asynchronous online resources to capitalize on their digital enthusiasm, while junior-year programs could blend complex problem-solving tasks with offline instructor scaffolding to mitigate anxiety around technical content. Gender disparities in emotional responses—notably females’ higher negative affect—warrant flexible support mechanisms, such as optional peer mentorship circles or gender-segmented feedback sessions to address confidence gaps.

Thirdly, disciplinary differences further necessitate major-specific course customization. For science majors, SPOC platforms should incorporate lab simulations and technical terminology databases to bridge digital-physical learning gaps, whereas liberal arts courses could leverage SPOCs for collaborative writing projects and discussion forums that align with their self-regulated learning strengths. Critically, the study underscores the role of platform functionality and cultural context in emotional outcomes. Institutions must invest in user-friendly, stable learning ecosystems and foster a collectivist learning culture—for example, through group-based online challenges or offline collaborative assessments—to replicate the study’s low negative affect findings. Such culturally attuned designs could mitigate resistance in regions where blended learning remains novel, offering a scalable model for adaptive education.

The study findings indicate positive emotions among EFL students in HVCs under SPOC learning context, with lower levels of negative emotions. These results align with past research by Song et al.7 Kim and Ketenci16 Zhang et al.18. The emotional state of EFL students is influenced by factors such as grade, gender, blended learning style adaptability, blended learning environment adaptability, and learning willingness. The regression equation coefficients suggest that emotional levels decrease by 1.106 for each grade level, decrease by 1.405 for females compared to males, increase by 1.198 for greater blended learning style adaptability, decrease by 0.507 for less blended learning environment adaptability, and decrease by 1.020 for lower learning willingness.

Limitations warrant acknowledgment. The reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces potential biases, including social desirability responding and subjective interpretation of emotional experiences. Additionally, the sample’s geographic specificity and cross-sectional design limit generalizability across diverse educational and cultural contexts. Future research should adopt mixed-methods approaches to triangulate self-reports with physiological measures (e.g., EEG, eye-tracking) or observational data. Longitudinal designs could clarify how emotional responses evolve during prolonged SPOC exposure. Cross-cultural comparisons might explore whether collectivist educational norms—such as China’s structured learning culture—systematically moderate emotional engagement patterns. Furthermore, experimental studies manipulating specific SPOC design features (e.g., interactive modules vs. passive content delivery) could identify causal links between pedagogical choices and affective outcomes. Such inquiries would advance understanding of how blended learning ecosystems can optimize both cognitive and emotional dimensions of language education.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to participants’ privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Artino, A. R. Jr Emotions in online learning environments: Introduction to the special issue. Internet High. Educ. 15(3), 137–140 (2012).

Hascher, T. Learning and emotion: Perspectives for theory and research. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 9(1), 13–28 (2010).

Pekrun, R. et al. Academic emotions in students’ Self-Regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37, 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 (2002).

Swan, K. & Shih, L. F. On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 9(3), 115–136 (2005).

Zhao, H. & Zhang, X. Emotional States and characteristics of online learning among distance learners. Mod. Distance Educ. Res. 2019(2), 85–94 (2019).

Hejazi, E., Narenji Thani, F. & Ghofrani, A. Psychological components related to students success in a blended learning environment. J. Appl. Psychol. Res. 12(3), 105–127 (2021).

Song, N., Jiang, Q. & Luo, L. Research on the influencing factors of online learning emotion of junior high school students. Educ. Teach. Res. 04, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.13627/j.cnki.cdjy.220.04.003 (2020).

Wang, M. The current practice of integration of information communication technology to english teaching and the emotions involved in blended learning. Turki. Online J. Educ. Technol. TOJET 13(3), 188–201 (2014).

Yang, Y. et al. A study on the influence of flipped classroom on college students’ academic emotion and learning autonomy. Health Vocat. Educ. 04, 60–62 (2022).

Jiang, L. Factors influencing EFL teachers’ implementation of SPOC-based blended learning in higher vocational colleges in China: A study based on grounded theory. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32(3), 859–878 (2024).

Jiang, L. & Liang, X. Influencing factors of Chinese EFL students’ continuance learning intention in SPOC-based blended learning environment. Educ. Inform. Technol. 1–26 (2023).

Li, H. & Li, X. Discussion on SPOC experiential learning based on distribution flflipping in post MOOC era. Audio Vis. Educ. Res. 36(11), 44–50 (2015).

Vernadakis, N., Giannousi, M., Derri, V., Michalopoulos, M. & Kioumourtzoglou, E. The impact of blended and traditional instruction in students’ performance. Procedia Technol. 1, 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2012.02.098 (2012).

Fang, Z. & Xia, Y. An empirical study of english learners’ academic emotions and the factors affecting their classroom environment: A case study of CBI curriculum reform for english majors. Lang. Educ. 01, 48–53 (2015).

Laukenmann, M. et al. An investigation of the influence of emotional factors on learning in physics instruction. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 25(4), 489–507 (2003).

Kim, M. K. & Ketenci, T. The role of expressed emotions in online discussions. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 52(1), 95–112 (2020).

Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E. & Belland, B. R. Interaction, internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High. Educ. 20, 35–50 (2014).

Zhang, J., Chen, M. & Chen, C. The relationship between online learning engagement and students’ perceived learning outcomes: A study of Chinese students in the united States. J. Interact. Online Learn. 17(3), 238–252 (2020). https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/17.3.4.pdf

Zhao, H. & Zhang, X. A study on the factors influencing online learning emotions of Chinese adult learners. Open Educ. Res. 2, 78–88 (2018).

Li, Z., Guan, P., Li, J. & Wang, J. Comparing online and offline Chinese EFL learners’ anxiety and emotional engagement. Acta Psychol. 242, 104114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.104114 (2023).

Li, Z., Dai, Z., Li, J. & Guan, P. Does the instructional approach really matter? A comparative study of the impact of online and in-person instruction on learner engagement. Acta Psychol. 253, 104772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.104772 (2025).

Muirhead, B. The challenges and opportunities of E-learning in higher education. In Handbook of Research on E-Learning Applications for Career and Technical Education: Technologies for Vocational Training 1–24 (IGI Global, 2018). https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2918-0.ch001.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1 (2008).

Keller, J. M. First principles of motivation to learn and e3-learning. Distance Educ. 29(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802154970 (2008).

Wegerif, R. The social dimension of asynchronous learning networks. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2, 1 (1998). http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v2n1/v2n1_wegerif.asp

Zembylas, M. Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Educ. 1, 71–87 (2008).

Moriña, A. The keys to learning for university students with disabilities: motivation, emotion and faculty-student relationships. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215249 (2019).

Trigueros, R. et al. The role of perception of support in the classroom on the students’ motivation and emotions: The impact on metacognition strategies and academic performance in math and english classes. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02794 (2020).

Garrison, D. R. & Kanuka, H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 7(2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001 (2004).

Staker, H. & Horn, M. B. Classifying K-12 blended learning. Innosight Institute (2012).

Acosta-Gonzaga, E. & Ramirez-Arellano, A. The influence of motivation, emotions, cognition, and metacognition on students’ learning performance: A comparative study in higher education in blended and traditional contexts. Sage Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/215824402110275 (2021).

Park, Y. A pedagogical framework for mobile learning: Categorizing educational applications of mobile technologies into four types. Int. Rev. Res. Open. Distrib. Learn. 12(2), 78–102. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v12i2.791 (2011).

Croft, N., Dalton, A. & Grant, M. Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. J. Educ. Built Environ. 5(1), 27–64. https://doi.org/10.11120/jebe.2010.05010027 (2010).

Whiteside, A. L. & Dikkers, A. G. Leveraging the social presence model: A decade of research on emotion in online and blended learning. In Emotions, Technology, and Learning 225–241 (2016).

Cavanagh, M., Chen, B., Bathgate, M., Frederick, J. & Haney, M. Blended learning in higher education: Institutional adoption and implementation. Comput. Educ. 94, 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.008 (2016).

Guo, X. & Liang, Y. Effects of blended learning on learning outcomes and learner satisfaction. Int. J. Inform. Educ. Technol. 5(5), 365–368. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2015.V5.560 (2015).

Liu, B. Research on the learning attitude of college students in SPOC-based blended learning environments. J. Huaibei Normal Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 5(39), 78–82 (2018).

Ye, X. A study on the influence of flipped classroom on students’ learning emotion—taking the students of industrial design major who participate in off campus competitions as an example. Art Educ. 14, 79–81 (2018).

Ramirez-Arellano, A., Acosta‐Gonzaga, E., Bory‐Reyes, J. & Hernández‐Simón, L. M. Factors affecting student learning performance: A causal model in higher blended education. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 34(6), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12289 (2018).

Butz, N. T., Stupnisky, R. H. & Pekrun, R. Students’ emotions for achievement and technology use in synchronous hybrid graduate programmes: A control-value approach. Res. Learn. Technol. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v23.26097 (2015).

Daniels, L. M. & Stupnisky, R. H. Not that different in theory: Discussing the control-value theory of emotions in online learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 15(3), 222–226 (2012).

Iqbal, J., Asghar, M. Z., Ashraf, M. A. & Yi, X. The impacts of emotional intelligence on students’ study habits in blended learning environments: The mediating role of cognitive engagement during COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 12(1), 14 (2022).

Jiang, L., Al-Shaibani, K. S. & G Influencing factors of students’ small private online course-based learning adaptability in a higher vocational college in China. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32(3), 972–993 (2024).

Shao, K., Kutuk, G., Fryer, L. K., Nicholson, L. J. & Guo, J. Factors influencing Chinese undergraduate students’ emotions in an online EFL learning context during the COVID pandemic. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. (2023).

Jiang, L., Liang, F. & Wu, D. Effects of Technology-aided teaching mode on the development of CT skills of EFL students in higher vocational colleges: A case study of english argumentative writing. Think. Skills Creat. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2024.101594 (2024).

Titsworth, S., Quinlan, M. M. & Mazer, J. P. Emotion in teaching and learning: Development and validation of the classroom emotions scale. Commun. Educ. 59(4), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634521003746156 (2010).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellgen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 54(6), 1063–1070 (1998).

Huang, L., Yang, T. & Ji, Z. A study on the applicability of the positive negative emotion scale in Chinese population. Chin. J. Mental Health 1, 54–56 (2003).

Wang, X. & Liu, H. Exploring the moderation roles of emotions, attitudes, environment, and teachers on the impact of motivation on learning behaviors in students’ English learning. Psychol. Rep.. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941241231714 (2024)

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J. & Maier, M. A. Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: A theoretical model and prospective test. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 583–597 (2006).

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J. & Maier, M. A. Achievement goals and achievement emotions: testing a model of their joint relations with academic performance. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 115–135 (2009).

Liu, H., Zhu, Z. & Chen, B. Unraveling the mediating role of buoyancy in the relationship between anxiety and EFL students’ learning engagement. Percept. Mot. Skills. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125241291639 (2024).

Liu, H., Li, X. & Yan, Y. Demystifying the predictive role of students’ perceived foreign Language teacher support in foreign Language anxiety: the mediating role of L2 grit. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2223171 (2023).

Yuhanna, I., Alexander, A. & Kachik, A. Advantages and disadvantages of online learning. J. Educ. Verkenn. 1(2), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.48173/jev.v1i2.54 (2020).

Li, H. & Meng, Y. Analysis of learning emotions of distance and open education students in electric university. J. Beijing Inst. Educ. Nat. Sci. Ed. (1), 18–22 (2011).

Wang, Q., Chen, L. & Liang, Y. The effects of positive emotions on learner engagement and academic outcomes in online learning: The mediating role of learner engagement. Int. Rev. Res. Open. Distrib. Learn. 18(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.2885 (2017).

Liu, M. & Liu, C. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and negative affect: An examination of moderating role of mobile addiction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 159, 120194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120194 (2020).

Li, J. B., Yang, A., Dou, K. & Cheung, R. Y. M. Self-quarantine fatigue and life satisfaction among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of online learning experience. Qual. Life Res. 30(10), 2767–2780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02870-3 (2021).

Xie, X. et al. Psychological distress, negative affect, and online learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12, 625409 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 2023 The twelfth batch of “China Foreign Language Education Fund” (Grant No: ZGWYJYJJ12A083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.: Conceptualized and designed the research framework; conducted systematic data collection and primary analysis; developed the initial draft and refined the methodological structure. X.N. (CA): Interpreted results and proofreading.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, L., Niu, X. A study on the learning emotions of EFL students in SPOC based blended learning in Chinese vocational colleges. Sci Rep 15, 15126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99350-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99350-9