Abstract

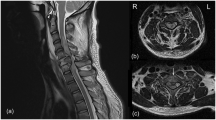

Ischemic stroke remains a major health challenge with limited treatment options. NeuroAid II (MLC901), a multi-herbal remedy, has shown clinical promise in post-stroke recovery, though its molecular mechanisms are unclear. This study employed an integrative computational approach, including network pharmacology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, molecular mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) free energy calculations, and pharmacophore modeling, to investigate NeuroAid II’s neuroprotective mechanisms. Active compounds were screened for drug-likeness and matched to ischemic stroke-related targets via target prediction and protein–protein interaction analysis. Top ligands were docked to key targets, followed by 100 ns MD simulations and binding energy estimation. Network analysis identified MMP2 and SRC as critical targets. Docking and MD results showed baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG formed stable, specific interactions with both proteins. DCP-sterol showed the strongest binding affinity to MMP2 (− 31.06 kcal/mol) and SRC (− 17.10 kcal/mol), outperforming standard inhibitors. DMCG and baicalin also displayed favorable binding to MMP2 (− 12.17 and − 13.54 kcal/mol, respectively) and SRC (− 16.19 and − 10.60 kcal/mol, respectively). Pharmacophore models revealed conserved hydrogen bonding (Ala86 in MMP2; Ala393/Ala296 in SRC) and key hydrophobic features. These findings provide molecular insights into NeuroAid II’s multitarget effects and highlight promising lead compounds for further validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a leading cause of mortality and long-term disability worldwide, primarily resulting from an obstruction in cerebral blood flow due to thromboembolism1,2. The blockage deprives brain tissues of oxygen and essential nutrients, triggering a cascade of pathological events, including excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis3,4. Despite extensive research, effective therapeutic strategies for ischemic stroke remain limited, with current treatments primarily focused on thrombolysis using recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) or mechanical thrombectomy5,6,7. However, these interventions are constrained by a narrow therapeutic time window and potential hemorrhagic complications, necessitating the exploration of alternative neuroprotective therapies8,9. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has gained attention in stroke management due to its multimodal therapeutic actions10. NeuroAid II (MLC901), a second-generation herbal formulation derived from the original NeuroAid (MLC601), has been developed to promote neuroprotection and neurorepair in stroke recovery11. Unlike MLC601, which contains both herbal and animal-derived components, NeuroAid II consists solely of herbal ingredients, making it more accessible and acceptable for widespread clinical use. The formulation comprises nine medicinal plants, including Radix Astragali, Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae, Radix Paeoniae rubrae, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Radix Angelicae sinensis, Flos Carthami, Semen Persicae, Radix Polygalae, and Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii, each of which has been traditionally used for its neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties11,12,13.

Despite its promising clinical benefits, the molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of NeuroAid II remain largely unexplored. Previous studies have primarily focused on pharmacological efficacy, toxicity, and clinical outcomes14,15,16, with limited molecular insights into its interaction with ischemic stroke-associated pathways and target proteins. The multi-component nature of NeuroAid II adds another layer of complexity, as the synergistic or individual contributions of its herbal compounds are not well characterized at the molecular level. Another key research gap is the lack of comprehensive molecular simulations that validate the bioactivity of NeuroAid II compounds against stroke-related targets. While molecular docking studies have been used in some herbal medicine research, they are often limited to static representations of ligand–protein interactions, failing to capture the dynamic nature of molecular binding17,18. To address this limitation, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are required to provide a more realistic assessment of the stability and flexibility of ligand-target complexes under physiological conditions19,20. Additionally, no studies have systematically evaluated the pharmacophore features of NeuroAid II, which could be instrumental in optimizing its bioactive components for enhanced therapeutic efficacy.

This study aimed to investigate the molecular mechanisms of NeuroAid II in ischemic stroke through an integrative computational approach combining network pharmacology, molecular docking simulations, MD simulations, and pharmacophore modeling. The research systematically identified bioactive compounds in NeuroAid II, predicted their potential target proteins, and evaluated their molecular interactions. Initially, network pharmacology was utilized to explore the active compounds and their associated targets, constructing a comprehensive network to understand the interactions between NeuroAid II components and stroke-related biological pathways21. Molecular docking simulations were then conducted to assess the binding affinity and molecular interactions between selected compounds and key stroke-related proteins, providing insights into their potential therapeutic relevance. To further validate these findings, MD simulations were performed to analyze the stability, flexibility, and persistence of ligand-target complexes under physiological conditions by examining parameters such as structural deviations, molecular fluctuations, hydrogen bonding, and binding free energy22,23. Finally, pharmacophore modeling was employed to identify essential molecular features responsible for the bioactivity of NeuroAid II compounds, aiding in the rational design of optimized derivatives with enhanced therapeutic potential. This integrative molecular simulation study provided a mechanistic understanding of the neuroprotective effects of NeuroAid II in ischemic stroke, offering valuable insights for further experimental validation and potential clinical applications.

Results

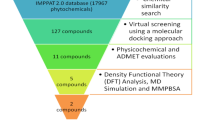

Unraveling drug–target interactions and prioritization of target receptors

To systematically elucidate the pharmacological landscape of NeuroAid II, a comprehensive drug–target network was constructed by integrating compound screening and disease-target mapping. Initially, the herbal composition of NeuroAid II, consisting of nine medicinal plants, yielded 1070 phytochemical constituents retrieved from various TCM databases. These raw compounds were filtered using well-established pharmacokinetic criteria: oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.18, resulting in 159 putative bioactive compounds. After removing duplicate entries, a final set of 143 unique bioactive compounds was selected for target prediction analyses. Among the individual herbal components, Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae (Dan Shen) contributed the highest number of filtered bioactive compounds (65), followed by Radix Paeoniae rubrae (29), Flos Carthami (23), and Radix Astragali (20). Interestingly, herbs such as Rhizoma Chuanxiong and Radix Angelicae sinensis, despite contributing a large number of unfiltered compounds (188 and 125, respectively), retained only a small number after pharmacokinetic filtering (7 and 2, respectively). This highlights the selectivity imposed by absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME)-related filtering and underscores the pharmacological relevance of a smaller subset of highly bioavailable and drug-like compounds.

The network visualization summarizes the compound–target–disease associations from a comprehensive screening and intersection analysis of multiple herbal components in the NeuroAid II formula, highlighting the complexity of pharmacological interactions through compound diversity and target convergence. Following compound filtration, target prediction was conducted using SwissTargetPrediction (STP), Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA), and PharmMapper platforms. These platforms predicted 22,145 compound–protein interactions, which were subsequently refined by excluding duplicates, resulting in 642 unique human proteins. After removing duplicates, 1239 disease-related human targets were curated from multiple databases. The intersection between the predicted compound targets and the disease targets revealed 189 common protein targets, which are shown at the center of the network (hexagonal nodes in varying shades of blue-green), signifying key molecular mediators in NeuroAid II pathophysiology. These 189 intersecting proteins are targeted by multiple bioactive compounds extracted from nine different medicinal herbs. The orange oval nodes represent 59 bioactive compounds from Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae, demonstrating the herb’s dominant contribution to the network (Fig. 1). Their connections to nearly all 189 proteins suggest a broad pharmacological spectrum, consistent with its known multitarget properties in neurovascular and anti-inflammatory contexts24,25.

Compound–target–disease interaction network. Hexagonal nodes in blue-green shades represent the 189 intersecting human protein targets. Orange oval nodes represent 59 compounds from Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae. Green arrowhead nodes represent 17 compounds from Radix Astragali. Blue parallelogram nodes represent eight compounds from Radix Paeoniae rubrae. Purple triangle nodes represent 11 intersection compounds shared among multiple herbs. Pink diamond nodes represent 14 compounds derived from other herbs in the NeuroAid II formula. The complete list of compound–target–disease interactions is provided in Supplementary Data 1, specifically in the tab titled “Compound–disease interactions”.

The green arrowhead nodes denote 17 compounds from Radix Astragali, another herb with neuroprotective properties, which also exhibits a strong interaction pattern across the target space. Blue parallelogram nodes signify eight compounds derived from Radix Paeoniae rubrae, known for its neuroprotective potential26. Purple triangle nodes represent 11 shared compounds, common to multiple herbs (intersectional bioactives), which could act as synergistic agents in polyherbal formulations. Finally, 14 magenta diamond nodes indicate additional compounds from other herbs involved in the NeuroAid II formulation, contributing supplementary or modulatory effects. For instance, Radix Angelicae sinensis significantly reduced levels of IL‑1β, TNF‑α, and NF‑κB. NF‑Κb, while upregulating Bcl‑2 and downregulating Bax and cytochrome C. This action helps protect neurons against oxidative stress and apoptosis, and promotes angiogenesis in ischemic brain tissue via pathways such as PI3K/Akt/HIF-1/VEGF signaling27,28. The dense connectivity in the network, illustrated by the web of grey lines, emphasizes the multicomponent, multitarget therapeutic approach, reflecting the holistic principles of traditional herbal medicine. These overlapping interactions highlight potential synergistic mechanisms that could modulate key pathological pathways in NeuroAid II, such as neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, immune regulation, and neuronal survival.

Figure 2a shows a Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between targets associated with NeuroAid II and those related to ischemic stroke, identifying 189 common target proteins (11.17%). These shared targets represent key molecular intersections through which NeuroAid II may exert its therapeutic effects in the context of ischemic stroke. A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING database to evaluate the functional relevance of these common targets. As shown in Fig. 2b, the resulting network consists of 186 nodes and 2862 edges, indicating a high level of interaction among the proteins. This dense network structure suggests that many of these proteins are involved in coordinated biological processes. To identify central nodes within the network, topological analysis was performed using four key centrality measures: Degree Centrality (DC), Eigenvector Centrality (EC), Betweenness Centrality (BC), and Closeness Centrality (CC)29. By applying the respective median thresholds (DC ≥ 64.5, EC ≥ 0.093, BC ≥ 1760.53, CC ≥ 0.154), 18 hub proteins were selected (Fig. 2c). CytoNCA and STRING analysis showed a tightly connected subnetwork (node degree: 16.7, clustering coefficient: 0.982, p-value: 3.49 × 10−14), indicating significant functional association despite being slightly above the p < 1.0 × 10−16 threshold30.

Network-based identification of key receptor targets for NeuroAid II in ischemic stroke treatment. (a) Venn diagram showing the overlap between predicted compound targets and ischemic stroke–related targets, resulting in 189 common target proteins. (b) Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the 189 intersected targets, comprising 186 nodes and 2862 edges, indicating a highly connected network. (c) A subnetwork of 18 core hub proteins was identified through stepwise topological filtering, forming a tightly clustered module with strong functional associations.

To further delineate the most relevant regulatory components within the network, a second round of topological filtering was applied using more stringent, median-based thresholds across four centrality measures: DC ≥ 16.0, EC ≥ 0.227, BC ≥ 0.205, and CC ≥ 0.947. This refined analysis yielded a subset of 14 core proteins, forming a highly interactive and tightly clustered subnetwork. Eight of those 14 core proteins, namely STAT3, AKT1, EGFR, ESR1, PPARG, MMP9, MMP2, and SRC, are known to play critical roles in ischemic stroke pathophysiology by regulating key biological processes, including neuroinflammation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, oxidative stress response, and neuronal survival31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Their high connectivity and central positions suggest they serve as critical hubs through which NeuroAid II may exert multi-target therapeutic actions. To ensure the relevance of these targets for compound interaction analysis, a final refinement step was performed to focus specifically on proteins functioning as receptors, which are more likely to mediate direct interactions with small molecules. As a result, JUN, ALB, CASP3, HIF1A, FGF2, and IGF1 were excluded from further analysis, as they are not classified as receptors. As a result, only eight receptor proteins (MMP2, PPARG, ESR1, EGFR, AKT1, STAT3, MMP9, and SRC) were subjected to molecular docking simulation, ensuring a targeted and pharmacologically relevant evaluation of compound–receptor binding within the NeuroAid II framework. Detailed datasets and network pharmacology analyses can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Molecular docking reveals favorable binding affinities and key protein–ligand interactions

From a pool of 143 filtered bioactive compounds derived from the NeuroAid II, a targeted selection strategy was employed to identify the most promising ligands for molecular docking simulations. The selection was based on the interaction coverage of each compound across the eight core receptor proteins previously identified as key targets in ischemic stroke pathophysiology. Only compounds predicted to interact with at least seven of the eight receptor targets were prioritized for docking analysis to ensure broad-spectrum target engagement. This criterion ensured a focus on multi-target compounds with the potential for maximal therapeutic impact through polypharmacological mechanisms. As summarized in Table 1, nine compounds met this stringent threshold, each demonstrating predicted interactions with seven of the eight core receptor proteins. These compounds exhibit structural and functional diversity, ranging from flavonoid derivatives to phenolic acids and glycosylated phytochemicals.

The molecular docking simulations provided key insights into the binding affinities and interaction profiles of selected bioactive compounds, particularly baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG, against core receptor targets involved in ischemic stroke (Table 2). The docking performance of these compounds was compared with standard therapeutic agents (e.g., aspirin, pioglitazone) and known receptor-specific antagonists and agonists, focusing on three representative receptors: MMP2, PPARG, and SRC. In the case of MMP2, a matrix metalloproteinase implicated in blood–brain barrier disruption and extracellular matrix remodeling post-stroke34,38, all three test compounds exhibited superior binding energy scores compared to the standard agents. DMCG achieved the most favorable binding energy at − 9.23 kcal/mol, slightly outperforming baicalin (− 9.17 kcal/mol) and DCP-sterol (− 9.12 kcal/mol). These values were more negative than those of the standard antagonist TP0597850 (− 8.65 kcal/mol) and significantly better than those of aspirin (− 6.70 kcal/mol). Notably, all three compounds displayed strong van der Waals interactions and negative desolvation energies, indicating stable and energetically favorable binding within the MMP2 active site.

Similar trends were observed for PPARG, a nuclear receptor involved in inflammation regulation and metabolic control39,40. While the standard agonist pioglitazone and antagonist SB-1406 produced binding energies of − 6.83 kcal/mol and − 7.13 kcal/mol, respectively, the test compounds showed markedly stronger binding. DMCG again performed best with a value of − 8.54 kcal/mol, followed by DCP-sterol (− 8.37 kcal/mol) and baicalin (− 8.00 kcal/mol). Baicalin’s powerful electrostatic interaction (− 74.8 kcal/mol) is noteworthy, suggesting a key role in modulating receptor conformation or activity. Although the root mean square deviation (RMSD) values varied slightly, all remained within an acceptable 2.0 nm threshold41, suggesting consistent pose stability. The SRC receptor, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase associated with cell survival and angiogenesis42, further confirmed the strong docking behavior of the test compounds. All three demonstrated excellent binding energy scores, DCP-sterol (− 9.91 kcal/mol), DMCG (− 9.42 kcal/mol), and baicalin (− 9.30 kcal/mol), exceeding the performance of both aspirin (− 6.91 kcal/mol) and the standard antagonist AP-23451 (− 8.99 kcal/mol). Here, DMCG showed a notably high van der Waals contribution, while baicalin demonstrated strong electrostatic interactions, which may enhance binding specificity. The complete molecular docking results of the eight core receptor targets with standard and nine selected ligands are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

Aspirin, as a reference therapeutics compound, exhibits a modest binding affinity for MMP2. The binding site interactions are mediated through hydrogen bonds with Leu83, Ala84, and His125, forming a relatively stable yet less potent interaction compared to other compounds (Fig. 3a). The orientation of aspirin within the binding cleft suggests a shallow occupation, which could reflect its limited inhibitory capacity against MMP2 (Fig. 4a). TP0597850, a known MMP2 antagonist, binds more tightly than aspirin, as indicated by its lower docking energy. It forms multiple hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, Ala88, and Thr91 (Fig. 3b), suggesting a deep insertion into the binding pocket and a strong stabilizing effect (Fig. 4b). These extended interactions across several conserved residues in the catalytic site enhance binding affinity and likely contribute to its effective antagonistic activity. This compound serves as a pharmacological benchmark for comparison with the phytochemicals in NeuroAid II.

2D interaction maps of standard therapy, standard inhibitor, and best-performing ligands in the MMP2 ligand-binding domain (LBD). (a) Aspirin (a standard drug used in ischemic stroke therapy) bound to MMP2, forming hydrogen bonds with Leu83, Ala84, and His125. (b) TP0597850 (standard MMP2 antagonist) showing hydrogen bonding with Ala84, Ala86, Ala88, and Thr91. (c) Baicalin, a natural flavone glycoside, interacts with Ala84, Ala86, and Glu130. (d) DCP-sterol, a sterol-based compound, forms a single hydrogen bond with Pro141. (e) DMCG, the top-performing ligand, forms hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, and His125. The interaction types are color-coded as follows: hydrogen bonds (bright green), van der Waals interactions (pale green), Pi–Alkyl (pink), Pi–Sigma (purple), and Pi–Sulfur (orange). The figures were generated using BIOVIA Discovery Studio version 2025 (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, San Diego, USA; https://www.3ds.com/products/biovia/discovery-studio).

Comparative 3D binding poses of standard therapy, standard inhibitor, and best-performing ligands in the MMP2 LBD. (a) Aspirin–MMP2 shows shallow binding with limited interactions. (b) TP0597850–MMP2 (standard inhibitor) forms multiple hydrogen bonds within the active site. (c) Baicalin–MMP2 binds centrally with strong polar interactions. (d) DCP-sterol–MMP2 binds near the cavity edge with fewer interactions. (e) DMCG–MMP2 shows the most stable pose with deep binding and key hydrogen bonds. The protein surface is shown in cyan, while ligands are displayed in distinct colors to differentiate their binding orientations. Blue dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. The figures were generated using UCSF ChimeraX version 1.11 (University of California, San Francisco, USA; https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/).

Baicalin, a flavone glycoside, demonstrates high affinity for MMP2, outperforming the standard antagonist TP0597850. It forms hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, and Glu130, showing hydrophilic and acidic residue interactions (Fig. 3c). This suggests that baicalin stabilizes within a critical binding region, potentially disrupting enzymatic activity. Its docking conformation implies that it can serve as a potent natural inhibitor of MMP2, supporting its reported anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in ischemic models (Fig. 4c). DCP-sterol, a sterol derivative, also shows strong binding affinity, close to baicalin. Unlike other ligands, it forms a single hydrogen bond with Pro141, a residue near the binding pocket’s outer edge (Fig. 3d). While fewer H-bonds are involved, the compound’s rigid, lipophilic steroid backbone likely enables extensive van der Waals interactions that contribute to its stability in the binding site (Fig. 4d). This suggests that nonpolar interactions significantly affect its inhibitory potential against MMP2. DMCG exhibits the highest binding affinity among all tested compounds in binding with MMP2. It establishes hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, and His125, indicating a deep and stable interaction within the catalytic groove (Fig. 3e). This binding pattern overlaps significantly with aspirin and baicalin, suggesting that DMCG targets functionally relevant residues but with enhanced affinity (Fig. 4e). These results highlight DMCG as a promising multi-functional lead compound with strong potential to inhibit MMP2 activity in stroke-related neuroinflammation. Notably, the hydrogen bonding pattern of baicalin and DMCG overlaps TP0597850, particularly at Ala84 and Ala86, suggesting a conserved interaction mode that may underlie its inhibitory effectiveness. The stable docking conformation of DMCG indicates its potential as a potent natural MMP2 inhibitor. The 2D interaction maps of PPARG and SRC complexes can be seen in Supplementary Data 3.

A comprehensive atomic contact analysis was conducted to evaluate the molecular interactions of selected ligands within their respective target binding domains. The interaction types were categorized into carbon–carbon (CC), carbon–oxygen (CO), carbon–nitrogen (CN), and other key atomic pairings, providing a quantitative view of binding engagement (Table 3). For the MMP2 complex, the standard therapy, aspirin, demonstrated the lowest interaction counts, notably with 968 CC and 712 CO contacts, and negligible heavy-atom interactions. In contrast, the standard antagonist TP0597850 exhibited significantly higher interaction levels across all categories, including 2926 CC, 1661 CO, 1389 CN interactions, and 154 NN interactions, indicating a densely packed binding pose. Among the test compounds, DMCG showed the highest interaction counts overall, including 2724 CC, 2139 CO, and 738 CN contacts, suggesting the strongest and most stable binding within the MMP2 active site. Baicalin and DCP-sterol also demonstrated robust interaction profiles, though baicalin showed a more balanced polar and nonpolar contact distribution.

In the PPARG complexes, aspirin again showed minimal interaction (e.g., 706 CC, 467 CO), reflecting its weak binding affinity. Standard agonist pioglitazone and antagonist SB-1406 demonstrated moderate interaction counts, especially in CN and NO contacts. Notably, DMCG formed the most extensive interaction network with PPARG (2155 CC, 1715 CO, 554 CN), surpassing even baicalin, which still maintained a strong profile. DCP-sterol had high CC contacts (2085) but low polar interactions, indicating mainly hydrophobic engagement. For the SRC complexes, DMCG again outperformed all other ligands with an exceptionally high number of polar and nonpolar contacts (e.g., 2879 CC, 2414 CO, 796 CN, and 407 NO interactions). The standard antagonist AP-23451 also showed a strong interaction network (e.g., 2238 CC, 1324 CN, and 194 NN), while aspirin remained the weakest binder. Baicalin showed a robust polar contact profile (e.g., 363 OO and 335 NO interactions), reinforcing its high binding potential. DCP-sterol displayed the highest CC contact count (3234) but minimal polar contacts, suggesting its interaction is primarily hydrophobic. Comprehensive molecular interaction profiles of the eight core receptor targets with standard and nine selected ligands are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

MD simulations corroborate the stability and binding fidelity of ligand–receptor complexes

To investigate the dynamic stability, conformational changes, and binding fidelity of selected protein–ligand complexes, 100 ns MD simulations were explicitly conducted on MMP2 and SRC complexes. These two receptors were prioritized based on earlier docking and interaction profiling results, which revealed notable structural and binding similarities between the top three phytocompounds (baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG) and the standard ligands (aspirin and TP0597850 for MMP2; aspirin and AP-23451 for SRC). In contrast, other protein targets exhibited less consistent binding profiles and were thus excluded from MD analysis. For each selected protein (MMP2 and SRC), simulations were performed on six systems: the apo-protein (unbound form), the complex with a standard therapy ligand, the complex with a known standard antagonist, and complexes with the three top-ranking phytocompounds.

The RMSD is a critical metric for assessing the global structural stability of protein–ligand complexes throughout simulation43. As seen in Table 4 and Fig. 5a, the apo–MMP2 system remained highly stable throughout the simulation, with an average RMSD of 0.20 nm, reflecting the intrinsic structural rigidity of the unbound protein. Although the RMSD plot shows occasional spikes exceeding 4 nm, replicate simulations confirm that these represent transient loop fluctuations rather than systematic instability. The Aspirin–MMP2 complex exhibited the highest average RMSD (2.69 nm) and pronounced fluctuations, including intermittent excursions above 4 nm. These events were reproduced in repeated simulations and arise from aspirin’s weak and unstable binding mode, which leads to partial loop displacement and episodic ligand dissociation. This behavior suggests that aspirin binding significantly destabilizes the protein or fails to maintain consistent interactions, a pattern indicative of ligand-induced structural perturbation rather than simulation failure. Conversely, the MMP2–DCP-sterol complex showed the lowest RMSD value (0.29 nm) among ligand-bound systems, indicating that this ligand maintains a tight, stable binding conformation throughout the simulation. Baicalin and DMCG also exhibited low RMSD values (0.46 nm and 0.58 nm, respectively), which closely matched the TP0597850 control (0.56 nm). These results strongly suggest that baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG form stable complexes with MMP2, indicating favorable binding and potential inhibitory behavior.

MD simulation profiles of MMP2 complexes with standard ligands and the top three ligands from NeuroAid II. (a) Root mean square deviation (RMSD). (b) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF). (c) Radius of gyration (RoG). (d) Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). (e) Average distance between ligand and receptor centers of mass. (f) The number of hydrogen bonds between the ligand and the receptor. The NeuroAid II ligands demonstrate comparable or superior dynamic stability and interaction fidelity relative to the standard antagonists, particularly in maintaining compact structures, stable binding distances, and consistent hydrogen bonding, thereby supporting their potential as effective MMP2 inhibitors.

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) measures the atomic fluctuations of each amino acid residue, providing insights into the local flexibility and ligand-induced dynamic changes44,45. As shown in Fig. 5b, all complexes exhibit similar RMSF profiles, with notable fluctuations around residues Gly66 to Ala88, an active-site region critical for MMP2’s catalytic function. Importantly, the RMSF profiles of baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG within the Gly66–Ala88 region closely mimic the fluctuation pattern of TP0597850, the known MMP2 antagonist. This suggests that these compounds likely interfere with the active site, destabilizing the local structure in a manner consistent with known inhibitory mechanisms. These fluctuations are essential as they reflect a potential disruption of hydrogen bonds and coordination geometry within the enzyme’s catalytic site, which can lead to functional inhibition. In contrast, the aspirin-bound system showed an inconsistent and reduced fluctuation profile, indicating weak interference with the active site and possibly an inability to modulate MMP2’s function effectively.

The radius of gyration (RoG) measures the protein’s compactness during the simulation46. A lower and stable RoG indicates a more tightly packed structure, generally favorable for ligand binding. The apo-MMP2 form had an average RoG of 1.53 nm, serving as a baseline. Among the ligand-bound systems, DCP-sterol again stood out with a RoG of 1.53 nm, suggesting it promotes a compact and structurally coherent complex. Baicalin and TP0597850 were nearly identical, with RoG values of 1.50 nm, supporting their antagonistic effect and structural stabilization of MMP2. DMCG showed a slightly higher RoG (1.50 nm), but it was still within a stable range. Although the Aspirin–MMP2 complex showed a relatively low average RoG (1.51 nm), it was not the lowest among the tested ligands. TP0597850–MMP2 and Baicalin–MMP2 exhibited slightly smaller RoG values (1.50 nm), indicating a more compact complex structure. The slightly higher RoG in the Aspirin complex may reflect subtle conformational flexibility or reduced compactness compared to the other ligand-bound forms (Fig. 5c). The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) indicates the degree to which protein surfaces are exposed to the solvent, reflecting the conformational openness of the protein47. As shown in Fig. 5d, the apo-protein exhibited an average SASA of 92.10 nm2. DCP-sterol had the highest SASA (97.56 nm2), suggesting that it may induce structural opening or allosteric changes, possibly affecting the protein’s binding pockets or flexibility. TP0597850 (96.14 nm2) and DMCG (95.62 nm2) also caused notable increases in SASA, correlating with their antagonistic behavior and active site disruption. This higher exposure implies that these ligands likely interfere with the solvent-exposed catalytic groove, either directly or allosterically. Baicalin had a SASA of 94.81 nm2, still elevated compared to the apo form. Meanwhile, the aspirin–MMP2 complex exhibited a moderate increase in SASA (95.45 nm2) compared to the apo-protein, but lower than several other ligand-bound complexes. This suggests a limited degree of conformational change upon binding, indicating a relatively modest structural impact on MMP2.

The average distance between ligand and receptor directly indicates binding persistence and affinity48. As seen in Fig. 5e, DCP-sterol maintained the closest average distance (0.980 nm) throughout the simulation, reflecting strong and stable binding within the binding site. Baicalin (1.319 nm) and DMCG (1.375 nm) also exhibited persistent and tight interactions, consistent with stable complex formation. These values are comparable to the standard antagonist TP0597850 (1.335 nm), indicating these ligands could serve as competitive inhibitors. On the contrary, the aspirin complex showed wide distance fluctuations and an average of 2.519 nm, signifying weak and inconsistent binding, likely due to limited or no engagement with key interaction residues. Hydrogen bonding is critical for ligand stabilization and specificity49. Figure 5f illustrates the number of hydrogen bonds between ligands and MMP2 over time. TP0597850 formed the most hydrogen bonds (average of 4), aligning with its role as a potent antagonist. DMCG formed three hydrogen bonds on average among the tested compounds, suggesting strong and stable anchoring. Baicalin and DCP-sterol followed with 2 and 1 average H-bonds, respectively. These values confirm sustained interaction of these compounds with the protein, particularly in or near the catalytic site. In contrast, aspirin formed only one hydrogen bond, which was inconsistent, further reinforcing its inferior binding affinity and likely limited inhibitory effect. The MD results of SRC complexes can be seen in Supplementary Data 5; Fig. S1.

The MM/PBSA binding free energy (ΔG_binding) values, as presented in Table 5, offer thermodynamic insights that complement the MD simulation data regarding the stability and affinity of each ligand–receptor complex. Lower ΔG_binding values reflect stronger ligand–receptor binding interactions and enhanced complex stability, thus serving as critical parameters to assess the inhibitory potential of compounds. For the MMP2 complexes, the MD simulation results indicated stable protein conformations and ligand binding behaviors for all complexes, particularly for the top three ligands from NeuroAid II. Notably, DCP-sterol, which possesses a rigid tetracyclic sterol scaffold with a hydrophobic alkyl side chain, showed the most favorable MM/PBSA binding energy (− 31.06 ± 4.40 kcal/mol). This bulky, nonpolar framework fits well into the hydrophobic cleft of MMP2, while the single hydroxyl group at C3 forms stabilizing polar interactions with nearby residues. These complementary features explain its excellent dynamic stability, characterized by consistent hydrogen bonding, the lowest average ligand–receptor distance (0.98 nm), and compact structural maintenance throughout the 100 ns trajectory. Similarly, baicalin, a flavonoid glycoside with multiple hydroxyl groups and a glucuronic acid moiety, demonstrated moderate binding affinity (− 13.54 ± 3.13 kcal/mol). The polyphenolic rings support π–π stacking with aromatic residues, while the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups form hydrogen bonds that stabilize its position within the binding pocket, consistent with the observed favorable RMSD and RoG values. DMCG, a glycosylated chromenol derivative, showed comparable binding energy (− 12.17 ± 5.14 kcal/mol). The dense array of hydroxyl groups on its sugar units allowed for persistent hydrogen bonding, while its aromatic chromenol ring anchored the molecule through hydrophobic interactions. Together, these structural features validate the strong binding predicted by MM/PBSA. In contrast, the Aspirin–MMP2 complex showed poor thermodynamic binding (ΔG_binding = − 1.36 ± 2.41 kcal/mol) and significant fluctuations in RMSD, reflecting its small, simple structure that lacks sufficient hydrogen bonding donors/acceptors and aromatic scaffolds, thereby explaining its weak inhibitory potential against MMP2.

Turning to the SRC complexes, a similar pattern emerges. DCP-sterol again demonstrated strong binding (− 17.10 ± 4.64 kcal/mol), with its sterol backbone deeply embedded in the hydrophobic SRC pocket, while the hydroxyl head group engaged in hydrogen bonding to anchor the ligand. This dual hydrophobic–polar interaction strategy is characteristic of steroid-like inhibitors and explains its superior performance over the standard antagonist AP-23451. DMCG also outperformed AP-23451 (− 16.19 ± 5.32 kcal/mol vs. − 13.04 ± 6.96 kcal/mol), leveraging its flexible sugar moieties to form multiple hydrogen bonds (3–4 on average) with SRC residues, while its rigid aromatic core provided hydrophobic anchoring. This combination of rigidity and flexibility allowed DMCG to adapt effectively within the binding site. Baicalin exhibited a moderate binding profile, but its planar flavone core enabled π–π stacking with key aromatic residues, while its glucuronic acid substituent formed electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions with polar residues. These features contributed to dampening local flexibility in the Glu415–Lys430 region, consistent with antagonist-like behavior. Importantly, the RMSF analysis of SRC highlighted that all three NeuroAid II ligands mirrored the fluctuation pattern of AP-23451 in the active site region, suggesting that their binding interferes with hydrogen bonding networks critical for SRC activation. This structural mimicry, combined with their favorable ΔG_binding values, supports the conclusion that these ligands may act as effective competitive SRC antagonists with therapeutic potential.

3D pharmacophore modeling and in silico toxicity reveal key bioactive features and safety profiles

The 3D pharmacophore modeling of MMP2-ligand complexes revealed distinct interaction patterns involving key amino acid residues, which are crucial for the antagonistic activity and stability of the ligand–receptor complexes. Pharmacophore features were classified into hydrogen bond (HB) donors/acceptors and hydrophobic (HP) interaction sites50,51. In the case of aspirin, the standard therapy, the ligand formed hydrogen bonding with Ala84 and a hydrophobic interaction with Leu83, suggesting limited engagement within the binding pocket (Fig. 6). Although these interactions contribute to some stabilization, the minimal hydrogen bonding network may explain aspirin’s relatively weak MM/PBSA binding free energy (− 1.36 ± 2.41 kcal/mol) compared to other ligands. Conversely, TP0597850, a known MMP2 antagonist, displayed a more extensive hydrogen bond network with Ala86, Ala88, and Thr91. Hydrogen bonding with Ala86, a recurring interaction hotspot, highlights its potential role as a critical anchoring point within the MMP2 active site. This enhanced bonding profile aligns with its more favorable MM/PBSA binding free energy (− 19.09 ± 4.92 kcal/mol), supporting its role as a potent reference antagonist.

3D pharmacophore modeling of ligand interactions with MMP2: (a) Aspirin, (b) TP0597850 (standard antagonist), (c) Baicalin, (d) DCP-sterol, and (e) DMCG. Yellow spheres indicate hydrophobic interaction sites, green arrows represent hydrogen bond donors, and red arrows signify hydrogen bond acceptors. The visualized pharmacophore features highlight key interaction residues within the MMP2 binding pocket, with notable conservation of hydrogen bonding at Ala86 in TP0597850, baicalin, and DMCG, suggesting a shared anchoring mechanism relevant to antagonistic activity. The figures were generated using LigandScout version 4.5 (Inte:Ligand GmbH, Vienna, Austria; https://docs.inteligand.com/ligandscout/).

Among the top ligands from NeuroAid II, baicalin exhibited a strong interaction profile, forming hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, Glu130, and His131, along with multiple hydrophobic contacts involving Val118, Leu138, Ala140, and Tyr143. The shared hydrogen bond with Ala86, similar to TP0597850, suggests that baicalin may mimic the antagonist’s inhibitory behavior, possibly disrupting enzymatic function through competitive inhibition. Its balanced hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction network may contribute to its moderate MM/PBSA binding free energy (− 13.54 ± 3.13 kcal/mol). DCP-sterol, on the other hand, lacked hydrogen bond interactions entirely but demonstrated strong hydrophobic contacts with Tyr74, Leu82, and Phe87. Despite the absence of polar interactions, DCP-sterol achieved the most favorable MM/PBSA binding free energy (− 31.06 ± 4.40 kcal/mol), indicating that hydrophobic interactions alone can drive strong binding affinity, possibly due to the ligand’s lipophilic nature and deep anchoring within the nonpolar regions of the MMP2 pocket. DMCG, which had a moderate MM/PBSA binding free energy (− 12.17 ± 5.14 kcal/mol), formed hydrogen bonds with Ala84, Ala86, and His121 and a hydrophobic interaction with Leu82. The presence of Ala86 hydrogen bonding again supports its potential to act in a similar antagonistic mechanism as TP0597850. The dual interaction modes (HB and HP) likely contribute to DMCG’s stable binding and antagonistic potential. The pharmacophore results for the SRC complexes, along with the detailed pharmacophore features for both MMP2 and SRC, are provided in Supplementary Data 5; Fig. S2 and Table S1.

The drug-likeness and toxicity profiles of baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG were assessed to evaluate their potential as orally available and safe drug candidates (Table 6). In terms of molecular weight (MW), all compounds are within an acceptable range, although DMCG (626.67 g/mol) slightly exceeds the traditional Lipinski’s rule threshold of 500 g/mol, which may affect oral absorption. However, baicalin (446.39 g/mol) and DCP-sterol (414.79 g/mol) conform to this rule, supporting their suitability for oral administration. AlogP, an indicator of lipophilicity, showed diverse values across the compounds. DCP-sterol recorded a high AlogP of 8.08, suggesting strong lipophilicity, which can facilitate membrane permeability but may also increase non-specific binding and toxicity risks. In contrast, baicalin and DMCG showed AlogP values of 0.64 and − 0.68, respectively, indicating balanced or hydrophilic properties that may benefit aqueous solubility. The hydrogen bonding capacity, reflected in the number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA), also varies significantly. DMCG exhibits the highest HBD (8) and HBA (15), which may enhance binding affinity through polar interactions but might also reduce permeability due to increased polarity. Baicalin, with 6 HBD and 11 HBA, presents a balanced profile, whereas DCP-sterol, with just one HBD and HBA, shows minimal polar interaction potential, which aligns with its high lipophilicity.

OB is a key determinant of drug delivery efficiency. All three ligands demonstrated moderate to good OB, with DMCG achieving the highest value at 49.28%, followed by baicalin (40.12%) and DCP-sterol (36.91%). These values suggest that all compounds have promising oral pharmacokinetic profiles, particularly DMCG. However, Caco-2 cell permeability, which reflects intestinal absorption potential, varies notably. DCP-sterol exhibited the best permeability (+ 1.32), consistent with its lipophilic nature, while baicalin (− 0.85) and DMCG (− 2.22) had negative values, indicating less efficient absorption via passive diffusion. Regarding BBB penetration, DCP-sterol (+ 0.87) appears capable of crossing the BBB, which could be advantageous for treating CNS-related conditions. Conversely, baicalin (− 1.74) and DMCG (− 3.36) show limited CNS accessibility, potentially restricting their use to peripheral targets or necessitating delivery enhancements. The DL scores of baicalin and DCP-sterol (both 0.75) are favorable, while DMCG scored slightly lower (0.62), suggesting marginally reduced compatibility with common drug-like properties.

From a structural and physicochemical standpoint, polar surface area (PSA) values support these observations. DCP-sterol has the lowest PSA (20.23 Å2), correlating with high membrane permeability, while baicalin and DMCG, with PSAs of 183.21 and 226.45 Å2, respectively, may face barriers in crossing lipid membranes, impacting oral absorption and BBB penetration. Importantly, the toxicity profile of all three ligands is promising, with none predicted to be mutagenic, tumorigenic, or irritant. However, DMCG shows potential reproductive toxicity, which raises concerns for its long-term or systemic use and warrants further investigation through in vivo toxicological studies. Lastly, molecular flexibility and complexity were examined. DCP-sterol demonstrates the highest flexibility (0.35) and a moderate complexity score (0.70), which might aid target adaptability but also affect specificity. Baicalin and DMCG showed higher complexity (0.90 and 0.87, respectively), which may enhance target selectivity but potentially reduce synthetic tractability.

Discussion

The multi-level computational framework applied in this study, encompassing network pharmacology, molecular docking, MD simulations, MM/PBSA calculations, and pharmacophore modeling, provides an integrated mechanistic perspective on the potential neuroprotective actions of NeuroAid II (MLC901) in ischemic stroke. Our network pharmacology analysis identified MMP2 and SRC as central stroke-relevant hub proteins potentially targeted by multiple NeuroAid II constituents. This aligns with their well-established involvement in extracellular matrix degradation, BBB instability, and neuroinflammation38,52,53. The convergence of several ligands (particularly DCP-sterol, DMCG, and baicalin) on these same targets suggests a coordinated multi-compound effect that may underlie the therapeutic profile reported for NeuroAid II.

Docking, MM/PBSA, and MD simulation data collectively indicate that these compounds can form stable and energetically favorable interactions with both MMP2 and SRC. While these computational approaches do not confirm biological activity, they reveal consistent structural features, such as conserved antagonist-like hydrogen-bond interactions with Ala86 (MMP2) and Ala393/Ala296 (SRC) that support a plausible inhibitory or modulatory role. Experimental evidence from the literature reinforces this interpretation for baicalin, which exhibits antioxidative, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects in ischemic models54,55,56 and is known to engage PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling57,58. The pharmacophore analysis further supports baicalin’s compatibility with known inhibitory motifs for these targets. Given the regulation of MMP2 and SRC by AKT signaling, the interaction of baicalin and the other NeuroAid II ligands with these proteins likely contributes to neuronal survival, neurite outgrowth, and vascular repair59,60,61. DCP‑sterol (a sterol alcohol) and DMCG (a glycosylated chroman derivative) also emerged with strong MM/PBSA binding energies and pharmacophore profiles closely matching standard inhibitors. Although experimental data on DCP‑sterol and DMCG in stroke models are currently limited, their structural features (a sterol scaffold for DCP‑sterol and multiple hydrogen-bonding donors/acceptors for DMCG) suggest potential for modulation of MMP2/SRC activity and stabilization within the binding pocket. These ligands may contribute synergistically to the observed neuroprotective profile of NeuroAid II through complementary binding and modulation of the same receptor targets.

NeuroAid II-treated models report reduced glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression62, preserved neuronal architecture, and enhanced electrophysiological function, effects likely linked to inhibition of MMP2 and SRC. SRC inhibition mitigates astrocytic scarring, while MMP2 suppression improves BBB integrity and reduces edema63,64. Furthermore, baicalin has been implicated in lowering MMP2 expression via p38-MAPK and NF-κB pathways65. With dual-target profiles, strong computational stability, and encouraging pharmacophore mimicry, DCP‑sterol, DMCG, and baicalin are promising scaffolds for precise drug development. Future investigations should evaluate their direct effects on MMP2 enzymatic activity, SRC phosphorylation, and downstream neuronal survival and angiogenesis in cellular and animal models. Given the favorable safety and efficacy profile of MLC901 in stroke trials (e.g., The Chinese Medicine Neuroaid Efficacy on AIS Recovery (CHIMES)), these compounds represent viable leads for refined therapeutic formulations grounded on mechanistic insight15.

The PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling axis plays a pivotal role in neuronal survival and post-ischemic repair, and its activation by NeuroAid II compounds such as baicalin has been repeatedly demonstrated in preclinical stroke models66,67. Upon PI3K activation, downstream phosphorylation of AKT leads to the inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), a kinase that otherwise promotes apoptosis, oxidative stress, and synaptic dysfunction68,69,70. By maintaining AKT activity and suppressing GSK3β, NeuroAid II promotes neuronal survival, axonal regeneration, and vascular repair. This pathway also interfaces with cytoskeletal reorganization and mitochondrial stability, providing a mechanistic explanation for the enhanced GAP-43 expression and neurite outgrowth observed with NeuroAid II treatment62. In ischemic models, upregulation of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling reduces infarct size and improves behavioral recovery71,72, reinforcing its role as a central therapeutic axis influenced by the bioactive compounds of NeuroAid II.

In parallel, the p38-MAPK and NF-κB pathways represent critical regulators of neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and BBB disruption during ischemic stroke73,74. Overactivation of p38-MAPK amplifies pro-inflammatory cytokine release (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β), while NF-κB nuclear translocation induces expression of inflammatory mediators and pro-apoptotic genes75,76. NeuroAid II, particularly baicalin, has been reported in experimental studies to attenuate these pathways, thereby downregulating MMP2 and reducing ECM degradation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress54,77. Based on the docking and MD simulation findings in this study, the NeuroAid II compounds may potentially influence both PI3K/AKT/GSK3β (pro-survival) and p38-MAPK/NF-κB (anti-inflammatory) signaling cascades through stable binding interactions with key upstream regulators. Rather than proving a definitive mechanistic outcome, our computational results provide predictive support for the hypothesis that these compounds could exert a multipathway modulatory effect, consistent with previously reported experimental observations. Thus, the data suggest a possible dual protective role, while acknowledging that confirmation of such effects requires targeted biological validation.

Limitations, clinical implications, and future works

Limitations

Despite the promising findings of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, while our integrative computational approach, encompassing network pharmacology, molecular docking, MD simulations, MM/PBSA calculations, and pharmacophore modeling, provides a robust theoretical framework, the biological relevance of these interactions remains to be experimentally validated. The protein–ligand interactions, although showing stable binding and favorable energy profiles in silico, do not account for the full complexity of the in vivo environment, including factors such as protein expression levels, post-translational modifications, compound metabolism, and pharmacokinetics. Importantly, no wet-lab experiments were performed to confirm MMP2 or SRC modulation by the predicted compounds, and the findings should therefore be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. Second, the compound-target network was constructed using existing databases and predictive models, which may introduce inherent biases or incomplete annotations. Some potentially relevant targets or secondary pathways could have been missed due to limitations in current interaction datasets or the exclusion of low-confidence interactions. Third, although our MM/PBSA calculations help estimate binding energies, they do not fully account for entropic contributions or solvation dynamics beyond the generalized Born approximation, which may affect the absolute interpretation of binding affinity.

Additionally, baicalin and other flavonoids may undergo significant biotransformation, which was not modeled in this study. A further limitation is the limited availability of literature-derived biological evidence for DCP-sterol and DMCG in the context of ischemic stroke. Unlike baicalin, which has well-documented neuroprotective effects, the predicted roles of DCP-sterol and DMCG are based almost entirely on computational predictions. This limits the strength of cross-validation and underscores the need for targeted biochemical assays, cell-based functional studies, and in vivo experiments to assess their modulatory effects on MMP2, SRC, and downstream pathways. Finally, while this study highlights DCP-sterol, DMCG, and baicalin as potential dual-target modulators of MMP2 and SRC, the assumption of synergistic or additive effects within NeuroAid II’s multi-component matrix requires further dissection. The combinatorial dynamics of these compounds, along with possible metabolic interactions and transport limitations, warrant further investigation through wet-lab integrative assays or pharmacokinetic studies.

Clinical implications

The computational findings presented here align with clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of NeuroAid II in post-stroke recovery. Clinical studies, including the CHIMES and CHIMES-E trials, have demonstrated that NeuroAid improves functional outcomes, reduces neurological deficits, and enhances long-term recovery in ischemic stroke patients11,78,79. Our in silico results, particularly the predicted inhibition of MMP2 and SRC and modulation of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β and NF-κB pathways, provide a mechanistic explanation for these observed clinical benefits. Specifically, the preservation of BBB integrity, attenuation of inflammatory cascades, and enhancement of pro-survival signaling predicted from our computational models correspond to clinical findings of reduced disability progression and improved neurological function. The predicted actions of baicalin, DCP-sterol, and DMCG in promoting neuronal survival, preserving BBB integrity, and attenuating inflammation suggest that the multi-component matrix of NeuroAid II may act synergistically to produce the functional improvements documented in patients. Importantly, this convergence of computational and clinical evidence strengthens the translational relevance of our study, supporting the rationale for further pharmacological optimization of NeuroAid II constituents as potential standalone or adjunctive therapies in stroke management.

Future works

Several future directions are proposed to bridge the gap between computational findings and clinical applications. First, experimental validation is imperative. This includes conducting in vitro enzyme inhibition assays for MMP2 and SRC to confirm the predicted antagonistic actions of DCP‑sterol, DMCG, and baicalin. Additionally, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) studies could quantify binding affinities and verify molecular interactions under physiological conditions. Second, to assess downstream functional relevance, cellular assays examining neuroprotective markers (e.g., p-AKT, GAP-43, VEGF, and GFAP) following compound treatment in ischemic neuronal or astrocytic models should be performed. Such studies would determine whether these compounds modulate survival and repair signaling cascades as predicted. Furthermore, BBB integrity assays, such as trans-epithelial/endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements in endothelial cell monolayers, could validate the mechanistic role of MMP2/SRC modulation in maintaining vascular integrity. Third, in vivo stroke models (e.g., middle cerebral artery occlusion in rodents) should be employed to test the efficacy of these compounds alone and in combination. Behavioral recovery metrics, infarct volume analysis, and immunohistochemical assessments would provide critical translational insights. Parallel pharmacokinetic and bioavailability studies are also essential, particularly for baicalin, which is known to undergo extensive hepatic metabolism. Finally, it is recommended that further structure–activity relationship (SAR) exploration and lead optimization be undertaken using de novo design tools. Analogues of DCP‑sterol and DMCG with improved solubility, metabolic stability, or blood–brain barrier permeability can be designed based on the pharmacophore features elucidated in this study. Integrating artificial intelligence-driven QSAR and multi-objective optimization approaches could accelerate the rational design of next-generation neuroprotectants derived from NeuroAid II components.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive in silico exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of NeuroAid II (MLC901) in ischemic stroke. By integrating network pharmacology, molecular docking, MD simulations, MM/PBSA energy analyses, and 3D pharmacophore modeling, we identified key bioactive compounds, DCP‑sterol, DMCG, and baicalin, that exhibit stable and energetically favorable interactions with critical stroke-related proteins MMP2 and SRC. These proteins, previously implicated in BBB integrity and neuroinflammatory responses, were shown to be effectively modulated by the selected compounds through shared hydrogen bonding at key residues such as Ala86 (MMP2) and Ala393/Ala296 (SRC). The computational results are consistent with experimental findings from prior in vitro and in vivo studies on MLC901, suggesting that the observed neurorestorative effects may be mediated, at least in part, by direct antagonistic actions on these molecular targets. These insights not only support the therapeutic potential of NeuroAid II in ischemic stroke but also pave the way for further experimental validation and optimization of its bioactive components for drug development.

Materials and methods

Bioactive compounds collection

The chemical composition of NeuroAid II was derived from its nine herbal components, including Radix Astragali, Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae, Radix Paeoniae rubrae, Rhizoma Chuanxiong, Radix Angelicae sinensis, Flos Carthami, Semen Persicae, Radix Polygalae, and Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. Data on the chemical constituents of these herbal plants were retrieved from the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP)80, developed by the Center for Bioinformatics, College of Life Science, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi, China; the Traditional Chinese Medicine Integrated Database (TCM-ID)81, maintained by Bioinformatics & Drug Design (BIDD) group in Department of Pharmacy, National University of Singapore; and the Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI) database82, curated by the EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Hinxton, UK. A filtering process was applied based on pharmacokinetic properties to select bioactive compounds from NeuroAid II. The selection criteria included two key parameters: OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.1883,84, as defined in TCMSP. OB is a critical pharmacokinetic property that quantifies the fraction of an orally administered dose that enters systemic circulation unchanged, ensuring the therapeutic potential of the compound for oral administration85,86. DL represents the structural and physicochemical attributes influencing ADME, as well as a compound’s overall pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties87,88. For compounds not available in the TCMSP database, additional pharmacokinetic analyses were conducted using SwissADME89, developed by the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB), Lausanne, Switzerland, and MolSoft Drug-Likeness and molecular property prediction90, developed by MolSoft, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA. Each compound was analyzed using its canonical simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES), which was obtained from PubChem91, a database maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, MD, USA. These computational tools provided supplementary predictions for OB and DL, ensuring a comprehensive screening of NeuroAid II’s bioactive constituents.

Network pharmacology-based target identification

The identification of potential target proteins for NeuroAid II was conducted using multiple network pharmacology platforms, including STP92, developed by the SIB, Lausanne, Switzerland; the SEA93, maintained by the Shoichet Lab at the University of California, San Francisco, USA; and PharmMapper94, developed by Honglin Li’s Lab, East China University of Science and Technology, Shanghai, China. The SMILES for each bioactive compound in NeuroAid II’s nine herbal ingredients were retrieved from PubChem and used as input for target prediction analyses. To refine the target selection, the filtering criteria were set to include only Homo sapiens proteins. In STP and SEA, a similarity-based approach was applied using the Tanimoto coefficient (TC), where a threshold of ≥ 0.5 was considered to ensure reliable target prediction21. The TC is a widely used metric in cheminformatics that measures the structural similarity between compounds, with values typically ranging between 0.5 and 0.895, depending on the study design. A higher TC threshold results in fewer predicted target proteins but increases the confidence in identified interactions. Target proteins predicted from all three databases were compiled, and duplicate entries were removed to generate a non-redundant set of potential NeuroAid II targets. To ensure consistency in protein nomenclature, all predicted targets were standardized using the UniProt database96, a widely recognized resource for curated protein sequence and functional information.

To establish disease relevance, ischemic stroke-associated target proteins were systematically collected from multiple biomedical databases using a comprehensive query approach. The keywords “ischemic stroke” and “cerebral infarction” were applied to search the GeneCards database97, developed by LifeMap Sciences Limited, Hong Kong, in collaboration with the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel, with a relevance score of ≥ 10.00 to ensure the selection of highly significant stroke-related genes. The NCBI Gene database98, maintained by the NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA, was also searched using the same keywords, with results filtered under the Homo sapiens taxonomy and protein-coding category to ensure human-specific relevance. Additionally, the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database99, maintained by Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, was utilized to extract genes associated with ischemic stroke and cerebral infarction, specifically focusing on genes classified as “Gene with known sequence” and “Gene with known sequence and phenotype”. All ischemic stroke-related target proteins obtained from these databases were compiled into a comprehensive dataset, and duplicate entries were systematically removed to eliminate redundancy. The final set of stroke-associated targets was standardized using the UniProt database to ensure consistency in gene and protein annotations. Integrating multiple high-quality data sources and applying rigorous filtering criteria established a robust and well-curated collection of ischemic stroke-related target proteins for subsequent computational analyses.

PPI network construction and analysis

A PPI network was constructed using the STRING database to investigate the functional landscape of NeuroAid II target proteins in the context of ischemic stroke. The analysis focused on the common protein targets identified through the intersection of predicted compound targets and ischemic stroke-related genes. The resulting network was visualized using Cytoscape, and topological properties were analyzed using the CytoNCA plugin100. Four centrality metrics, including DC, EC, BC, and CC, were calculated, and proteins meeting or exceeding the respective median thresholds for each metric were designated as hub nodes. A second round of topological filtering was performed using more stringent median-based cutoffs, resulting in a refined set of core proteins. Among these, only receptor-class proteins were selected for subsequent molecular docking analysis. The overall PPI network was further assessed for statistical significance using the STRING platform’s enrichment test, with significance determined by the default threshold of p < 1.0 × 10−16, indicating that the observed interactions were unlikely to occur randomly and instead reflect biologically meaningful associations30.

3D structure construction and MM2 energy minimization

To ensure accurate molecular modeling of the selected bioactive compounds from NeuroAid II, three-dimensional (3D) structures were generated using Chem3D Ultra v22, developed by PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA101. This software facilitated the conversion of two-dimensional (2D) representations of chemical compounds into their corresponding 3D molecular structures, preserving atomic connectivity and stereochemical information essential for computational analyses. Following 3D structure generation, MM2 (Molecular Mechanics 2) energy minimization was applied to refine molecular geometries and eliminate steric hindrances102. The MM2 algorithm is a widely used molecular mechanics force field that optimizes molecular conformations by adjusting bond lengths, bond angles, torsional angles, and non-bonded interactions, such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions103. This minimization process aimed to stabilize molecular structures by reducing their potential energy to a local minimum, ensuring that the generated conformations closely resemble their biologically relevant states. Using MM2 energy minimization, structural distortions were corrected, and chemically unrealistic geometries were avoided, enhancing the reliability of subsequent computational simulations, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies104.

Molecular docking simulations

Ligand-receptor docking simulations were performed to elucidate the binding mechanisms of NeuroAid II-derived bioactive compounds with key receptor targets involved in ischemic stroke. These simulations aimed to identify crucial binding residues, evaluate intermolecular interactions, analyze binding affinities, and determine binding orientations at the receptor’s active sites. Initially, PDBsum105, developed by the European Bioinformatics Institute (Cambridge, UK), was utilized to generate a structural summary of each target receptor, highlighting key binding residues within its active site. This mapping process facilitated the identification of potential binding sites for the bioactive compounds. To enhance docking accuracy, the target receptor structures were refined using Swiss-PdbViewer v4.1106, developed by Nicolas Guex, ensuring optimal geometry and structural stability before interaction studies. To determine the potential efficacy of NeuroAid II bioactive compounds in stroke-related pathways, comparative docking analyses were conducted using aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) as a standard reference drug. Aspirin is widely recognized as a first-line antiplatelet agent in the medical management of ischemic stroke due to its ability to inhibit platelet aggregation and reduce the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke107. This comparative approach provided valuable insights into the potential therapeutic roles of NeuroAid II bioactives by benchmarking their binding affinities and interaction profiles against a clinically validated stroke medication.

To explore the binding interactions between NeuroAid II bioactives and their target receptors, docking simulations were executed using the High Ambiguity Driven protein–protein DOCKing (HADDOCK) 2.4 web server (https://wenmr.science.uu.nl/haddock2.4/)108, developed by the University of Utrecht, Netherlands. This advanced platform specifies ligand-receptor interactions by integrating geometric and energetic constraints derived from experimental and computational data. The simulations were conducted using the HADDOCK web interface, ensuring precise predictions of binding modes. The selection of optimal docked complexes was based on two key parameters, including the cluster population size, which indicates the stability and reproducibility of the predicted interactions, and the HADDOCK score, which reflects the binding affinity strength between NeuroAid II bioactives and their target receptors. These stringent criteria ensured that only highly stable and functionally relevant docking models were retained for further evaluation. To refine the binding energy predictions, docking results were further analyzed using PROtein binDIng enerGY prediction (PRODIGY)109, a computational tool that estimates binding free energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) by incorporating structural and energetic features of ligand-receptor complexes. PRODIGY’s binding affinity estimation considered intermolecular contacts and desolvation effects, providing a physiologically relevant assessment of binding stability.

MD simulation

To investigate the dynamic behavior, structural stability, and conformational changes of NeuroAid II-derived bioactive compounds in complex with key receptor targets, MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2023.3110,111, a high-performance computational tool for biomolecular simulations. This approach provided an in-depth understanding of the temporal evolution, interaction stability, and receptor-ligand binding dynamics in ischemic stroke-related pathways. The general AMBER force field 2 (GAFF2) was applied for ligand parameterization, with atomic partial charges assigned using the AM1-BCC (Austin Model 1-bond charge corrections) method112,113. The AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE (ACPYPE) tool, integrated with AmberTools21, generated the ligand topology114. The CHARMM27 force field was used for the protein component to accurately represent protein–ligand interactions. The simulation system was enclosed in a truncated octahedral box, maintaining a minimum buffer distance of 1.2 nm between the complex and the box boundary. The system was solvated with TIP3P water molecules, and a 150 mM NaCl concentration was added to mimic physiological ionic strength, ensuring charge neutrality115,116. Periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) were applied to simulate a continuous biological environment. Nonbonded interactions were handled using a 1.0 nm cutoff for short-range interactions, while long-range electrostatic forces were computed using the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method117,118,119.

The system underwent multi-step equilibration before initiating the production simulation to ensure a stable and physiologically relevant environment. Energy minimization was performed using the conjugate gradient algorithm until the maximum force was reduced to 500 kJ/mol/nm. This was followed by canonical ensemble (NVT) equilibration for 200 ps, maintaining a constant temperature of 310 K using the V-rescale thermostat. Next, isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) equilibration was applied for 200 ps to stabilize pressure at 1 atm, regulated by the Monte Carlo barostat. Following equilibration, a 100 ns production simulation was executed under constant temperature and pressure conditions, controlled by the Nosé-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostats120,121. This long-duration simulation allowed for an in-depth evaluation of binding stability, conformational shifts, and interaction persistence over time. Post-simulation, the trajectory data were analyzed to assess ligand stability, protein flexibility, and receptor-ligand interactions. For systems exhibiting higher RMSD values, replicate MD simulations were performed to confirm reproducibility and assess binding stability. Several structural parameters were computed, including RMSD to evaluate global stability, RMSF to assess residue-level flexibility, and RoG to examine protein compactness. Additionally, hydrogen bonding interactions were analyzed to determine the strength and consistency of ligand binding throughout the simulation122. RMSD, RMSF, RoG values are reported in nanometers (nm) and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) in square nanometers (nm2), as directly obtained from GROMACS analysis tools. MM/PBSA binding free energies are reported in kilocalories per mole (kcal/mol) and were calculated using gmx_MMPBSA, an add-on tool integrated with the GROMACS package. All reported units correspond to the default outputs of the respective GROMACS and gmx_MMPBSA tools used in this study. To facilitate in-depth visualization and structural analysis, molecular graphics tools such as PyMOL 3.1.3 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, USA)123, BIOVIA Discovery Studio version 2025 (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, San Diego, USA)124, and UCSF ChimeraX version 1.11 (University of California, San Francisco, USA)125 were used for manual inspection and graphical representation of key binding interactions. This integrative MD simulation approach provided valuable insights into the binding stability and mechanistic role of NeuroAid II bioactive compounds, reinforcing their potential therapeutic relevance in ischemic stroke treatment.

MM/PBSA free energy analysis for evaluating ligand-receptor interactions

To assess the binding strength and stability of NeuroAid II-derived bioactive compounds with their target receptors, the MM/PBSA method was applied in conjunction with MD simulations. This computational approach provided a quantitative evaluation of binding affinity126, enabling a deeper understanding of the thermodynamic contributions governing ligand-receptor interactions in ischemic stroke-related pathways. Representative structural snapshots were extracted from MD trajectories to capture the dynamic conformations of the ligand-receptor complexes. These snapshots were used for detailed energy calculations, including gas-phase molecular mechanics energy, solvation energy, and entropy corrections. The SASA model127 was applied to estimate nonpolar solvation energy, accounting for the hydrophobic contributions to ligand binding. The single-trajectory protocol128 was employed to ensure consistency in energy evaluations, assuming minimal conformational changes upon ligand binding. This assumption enabled a more reliable calculation of the binding free energy (ΔG_binding) using the gmx_MMPBSA module129 within GROMACS. The binding free energy was computed based on the following equation:

ΔG_complex represents the total free energy of the solvated ligand-receptor system, while ΔG_ligand and ΔG_receptor correspond to the free energy of the unbound ligand and receptor, respectively.

3D pharmacophore modeling and virtual toxicity screening

To identify the key molecular features responsible for the bioactivity of NeuroAid II-derived compounds, 3D pharmacophore modeling was performed using LigandScout version 4.5 (Inte:Ligand GmbH, Vienna, Austria)130. This computational approach enabled the generation of pharmacophore models by mapping crucial interaction sites, including hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and electrostatic hotspots, which are critical for ligand-receptor binding131,132,133. The pharmacophore profile of NeuroAid II-derived bioactive compounds was further compared with well-established standard ligands known for their therapeutic potential in ischemic stroke treatment. This comparative analysis helped evaluate the structural and functional similarities between NeuroAid II-derived compounds and clinically relevant drugs, allowing for the identification of promising candidates with optimized pharmacological properties. Simultaneously, an in silico toxicity evaluation was performed using DataWarrior 6.4.2 (Actelion, Ltd, Allschwil, Switzerland)134 to assess the safety profiles of the identified compounds. This tool integrates molecular descriptors and machine-learning-based toxicity prediction algorithms to evaluate potential mutagenic, carcinogenic, hepatotoxic, and cardiotoxic risks135,136. By ensuring that only chemically viable and non-toxic candidates were selected, this approach refined the selection of potential drug candidates for further validation. This dual computational strategy comprehensively assessed the pharmacophoric characteristics and toxicity risk of NeuroAid II-derived bioactive compounds, reinforcing their therapeutic potential in treating ischemic stroke while ensuring optimal drug safety.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ADME:

-

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- AM1-BCC:

-

Austin Model 1-bond charge corrections

- BBB:

-

Blood–brain barrier

- BC:

-

Betweenness centrality

- CC:

-

Closeness centrality

- ChEBI:

-

Chemical Entities of Biological Interest

- CHIMES:

-

The Chinese Medicine Neuroaid Efficacy on AIS Recovery

- DC:

-

Degree centrality

- DL:

-

Drug-likeness

- EC:

-

Eigenvector centrality

- GAFF2:

-

General AMBER force field 2

- GFAP:

-

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HADDOCK:

-

High Ambiguity Driven protein–protein DOCKing

- HBA:

-

Hydrogen bond acceptor

- HBD:

-

Hydrogen bond donor

- ITC:

-

Isothermal titration calorimetry

- LBD:

-

Ligand-binding domain

- MD:

-

Molecular dynamics

- MM2:

-

Molecular mechanics 2

- MM/PBSA:

-

Molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area

- MProp:

-

MolSoft molecular properties

- MW:

-

Molecular weight

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NPT:

-

Number of particles, pressure, and temperature

- NVT:

-

Number of particles, volume, and temperature

- OB:

-

Oral bioavailability

- OMIM:

-

Online Mendelian Inheritance in man

- PBC:

-

Periodic boundary condition

- PME:

-

Particle-mesh Ewald

- PPI:

-

Protein–protein interaction

- PRODIGY:

-

PROtein binDIng enerGY prediction

- PSA:

-

Polar surface area

- RMSD:

-

Root mean square deviation

- RMSF:

-

Root mean square fluctuation

- RoG:

-

Radius of gyration

- rtPA:

-