Abstract

The stories of Cinderella, highlighting the theme of kindness, are classic children’s literature worldwide. In China, the translation of the Cinderella stories has been listed in the Chinese textbook series launched in 2004, exerting a profound influence on generations of Chinese readers. This study investigates how Huiguniang, the Chinese counterpart of the character Cinderella, has become a household name among Chinese children. By examining the changes, correlations, and shifts of their prototypical features under the framework of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther classification in the three Chinese translations of the Cinderella stories and the ancient Chinese folklore The tale of Ye Xian, the study examines how factors such as external stability, internal dynamic trade-offs, and the iterative nature and empowerment of translation have popularized and canonized Huiguniang in China. The study further extends its focus within the broader context of discourse studies, embracing the intersections of language and society, as it brings to light the intricate dynamics of translation, empowerment, and cultural reception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From “once upon a time” to “they lived happily ever after”, bedtime stories are part of growing up pathways from the west to the east and from ancient to modern times. Among the fairy tales, Cinderella is one of the most well-known in Europe and China (Li et al., 2016; Jameson, 1988; De la Rochère, 2016). In China, the story enjoys special popularity because it is listed on the Chinese Standard Experiment Textbook for the Compulsory Education Curriculum, first published in 2004. Every school child in China reads and learns this story during their nine years of compulsory education (usually aged 6–14), highlighting the significant status of this children’s literary canon in China.

In the realm of Chinese translations of Cinderella-themed stories, Douban, a Chinese online database and social networking platform, records an extensive inventory exceeding 3000 adaptations and reinterpretations of the Cinderella narrative across multiple cultural landscapes. The earliest and most prominent translations originate from the French and German Cinderella stories (found in Stories or Tales from Past Times and Grimm’s Fairy Tale, respectively) in the early 20th century. Among the most translated and reprinted versions are those by Sun Yuxiu, Sima Tong, Yang Wuneng, and Wei Yixin. Wei Yixin firstly translated the German Cinderella story into Chinese, while Sun Yuxiu was the first to translate the French Cinderella story into Chinese. Some translations have origins in Japanese sources (translated by Luxun), involving an indirect translation from Western languages to Japanese and then into Chinese. The journey of translations of Cinderella-themed stories in China showcases a shift in language from ancient Chinese to modern Chinese and reflects numerous transitions in source languages (Li, 2013), often coinciding with periods of cultural exchange or increased interest in foreign literature and folklore.

Cinderella stories are predominantly thought of as western stories (Lai, 2007) and more specifically, fairy tales of German and French origin. Notwithstanding such a Euro-centric argument, Chen (2020) and Waley (1947) explored the Chinese origins of the Cinderella story to discover its relationship with the long-neglected Chinese-originated Cinderella story The tale of Ye Xian authored by Duan Chengshi in the Tang Dynasty of China (803–863 BCE). Their findings shed new light on the research of Cinderella in China in that the canonized Cinderella story in China involves three cultures (hereafter tri-cultural): German, French, and ancient Chinese cultures. Such tri-cultural involvement and multiple-source text origination are not commonly seen in the context of translation studies and therefore entail a thorough study.

As well as its popularity and tri-cultural involvement, another rationale for the study of Cinderella is the change of the protagonist’s name from 辛度利拉(Xindulila, transliterated from Cendrillon) during the 1920s to the current household name of 灰姑娘(Huiguniang, not transliterated). Names are considered important in literary production, and the translation of names equally so. The change in the translation of names could signify other potential changes in the translation of the Cinderella story in China.

To portray these potential changes, this study adopts the notion of prototypical features from the domain of folklore research (Garry, 2017; Dundes, 1997). Prototypical features in this study refer to the motifs indexed from the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) classification (Aarne, 2018)—a catalogue and classification of folktale types established in folklore research. This choice is made not because the Cinderella story is indexed among the prototypes (i.e., ATU510 type) but for its representativeness in revealing the similarities between different tales, which is a good fit for the current research. Specifically, the study aims to answer the following questions: (1) What are the diachronic changes of the Cinderella story in China in terms of the overall prototypical features? (2) In which prototypical features are the canonized Cinderella story similar to or different from the previous Cinderella stories in China? (3) What is the evolving trajectory for the canonization of Huiguniang in China?

Literature review

Cinderella-themed stories around the world

There are many stories with the theme of Cinderella around the world. The origin of Cinderella-themed stories can be traced back to Europe and beyond. The oldest known oral version of the Cinderella story is the ancient Greek story of Rhodopis (Hansen and Fawkes, 2019, p. 86–87), followed by Aspasia of Phocaea from the Late Antiquity period (Ben-Amos, 2010, p. 438–439). More recent origins from Europe include Le Fresne from the twelfth century (Anderson, 2002, p. 41–42) and Ċiklemfusa from Malta. Cinderella stories outside Europe have been explored as long ago as 860 BCE in The tale of Ye Xian, which first appeared in Duan Chengshi’s Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang (Beauchamp, 2010, p. 447–496). Other origins of the present Cinderella-themed stories include Vietnam’s Cinderella story of Tam and Cam (Manggala, 2017, p. 65–73), the Cambodian version with the name Néang Kantoc (Leclère and Feer, 1895, p. 70–90), and several different variants of the story that appeared in the medieval One Thousand and One Nights (Marzolph et al., 2004, p. 4).

Cinderella-themed stories in China

The thousand-year-journey of the Cinderella-themed stories in the Chinese context can be tentatively classified into three stages: (1) Ye Xian in Tang China, (2) translations from French and German since the early 20th century, and (3) canonized in children’s textbooks since 2004.

For the first stage, as Cinderella-themed stories are at the outset classified as folklore literature passed down orally (Baum, 2000, p. 70), verification of their origin in China is considered difficult, if not impossible. Beauchamp (2010), Cullen (2003) and Louie (1982) have argued that the story of Ye Xian is the “earliest complete record” of the prototype of Cinderella-themed stories in China. As the earliest exemplar of the Cinderella-type tale found in a collection of exotica from the Tang Dynasty in China (803–863 BCE) authored by Duan Chengshi, the Chinese Cinderella story of Ye Xian narrates the tale of an abused stepdaughter helped by the bones of a fish she had raised.

The second stage covers the early 19th and 20th centuries when western ideas were introduced, characterized by the translation of new literary genres, including children’s literature, into classical Chinese (Luo and Zhu, 2019, p. 154). It was during this period that the European versions of Cinderella stories began to be told in the Orient. Among the myriad of translated versions, Cinderella was first translated into Chinese in 1913 (Sun, 1913) and then underwent a long journey in China for more than a century. Sun’s first attempt in introducing the story to Chinese recipients in the form of a story published in a magazine (Xiaoshuoyuebao) was from the French Cinderella story by Charles Perrault (1697) in Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passé, and this is included for the study with other book series. Another prevalent translation came from the German book Kinder-und Hausmärchen by Grimm (1812). This was translated by Wei (1934) in 1934 and has been reprinted many times, becoming a bestseller among all the translated Cinderella stories in the Chinese fairy tale market (Li, 2014).

In 2004, the story earned its canonization status by being selected for inclusion in the Standard Experiment Textbook for Compulsory Education Curriculum for fourth-grade elementary schools in China. It is true that Grimme fairy tales were recommended as extracurricular reading for many primary schoolchildren before 2004, yet the significance of canonization often extends beyond mere familiarity or recommendations to academic and educational endorsement. While extracurricular readings might encompass a broader range and larger volume, the process of being officially included in textbooks holds significantly more weight in terms of formal recognition and influence within the educational sphere (Kelly, 2009). The inclusion of Huiguniang in children’s textbooks suggests an authoritative recognition, indicating a deliberate selection and validation by educational authorities. Such a transition is pivotal because it reflects a formal acknowledgement of the text’s cultural and pedagogical value, aligning it with the educational objectives and standards set by the governing bodies in charge of curriculum development. Therefore, despite the familiarity or informal recommendation of Grimme fairy tales before 2004, the official incorporation of Huiguniang in 2004 solidifies its canonization within the structured educational system, establishing its enduring relevance for generations of Chinese students. The version appearing in the textbook is alleged to be adapted from the Grimms’ German version. It enters every child’s consciousness, becoming part of their childhood memories. This fairy tale in China is therefore shared by Chinese people, especially children, via collective cultural adaptation (Zhou and Moody, 2017) and the reproduction of literary values, testifying to its canonical status.

Canonization in translation studies

A literary canon broadly refers to the “body of texts taken to be the best a culture has to offer” (Baker and Saldanha, 2020, p. 52), where best can be expanded to include “major authors, a list of major works, or fundamental principles that govern literary criticism and judgment” (Farquhar, 1999, p. 299). The apparently fuzzy conceptualization in the words best, major, and fundamental reveals the challenges of subjectivity and ambiguity inherent in evaluating the literary canon; thus literary scholars have called for a more dynamic view of the literary canon as “canon is not an immutable, closed group of literary works but rather a dynamic body: texts can fall out and new texts can fall in” (Baker and Saldanha, 2020, p. 52). This opinion is echoed by Classen (2011) who specifies some trivialized occasions that should be treasured into the accepted literary canon. This study therefore adopts a dynamic and descriptive perspective congruent with the rationale.

Canonization, also known as “crystallization” (Even-Zohar, 2021) is the process of canon formation in “standing the test of time and finally enjoying general acclaim among readers, critics and academics alike” (Baker and Saldanha, 2020, p. 52). Much research has been devoted to topics on how the classics are formed and the basis for judging the canons (Corbin and Strauss, 1990; Gould, 2014; Altieri, 1983). The essentialist view of canonization emphasizes the aesthetic characteristics of the canonized literature per se with the argument that canonization takes place within literary works (Bloom, 2014). On the other hand, the constructivist view of canonization envisages canon as a manifestation of cultural politics, emphasizing the multiple external factors in the process of canon formation (Qinbing and Dongfeng, 2021). This is not dissimilar to Fokkema (1982) view that research into canonization should not be limited to displaying texts, but must also be explained and described through the dimensions of space, time, and society. Overall, canon formation is generally accepted as a “collective cultural process of value conferral upon works of literature” (Baker and Saldanha, 2020, p. 52) with influencing factors including the pure linguistics lens into the quality of the text and social-cultural or historical stances such as race, gender, or regional diversity (Lauter, 1991; Cawelti, 1997).

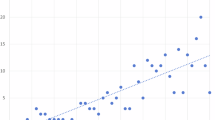

The process of canon formation in some cases transcends cultural boundaries (i.e., literary works being translated into other languages), thus legitimizing the afterlife of originally cannoned or non-cannoned literature into a different culture (Li, 2013). Each time literature crosses cultural boundaries, its literary value is reproduced in the form of translation if the boundaries of the notion of translation are to be expanded (Kolbas, 2018). Most translation research with a focal point on the relationship between canonization and translation concerns the way canons or non-canons from a foreign culture have either prospered or floundered in the recipient culture and literary systems (Rigney, 2012; Yu, 2020) (Fig. 1). For instance, the translation of Chinese classics like “Dream of the Red Chamber” into English and other languages, according to Moratto et al. (2022), has facilitated its recognition and eventual canonization in global literary circles, shaping cross-cultural dialogues and literary landscapes.

Within the realm of translation studies, the dynamics influencing canon formation, initially conceptualized through systems theory (Even-Zohar, 1990), are further elaborated upon by translation theorist Lefevere (2016). Lefevere’s contributions expand the scope by integrating crucial elements like patronage, ideology, and poetics, thus enriching the exploration of canon formation within the field of translation studies (Li et al., 2011; Chou and Liu, 2023). The system theory by Even-Zohar (1990) provided a descriptive viewpoint to describe the dynamics in how each culture compiles, through translation, its own canon of another culture and of world literature; and how this translated canon can also influence the domestic literature. Subsequently, the notions of patronage, ideology, and poetics (Lefevere, 2016) offers as an explanatory viewpoint answering questions of why specific texts are chosen or excluded for translation across cultures or why smaller literatures have the ability to comment on the canon of larger literatures through what they choose to import in translation (Venuti, 2013). It is expected that the integration of Even-Zohar’s system theory with Lefevere’s theoretical concepts will lead to a nuanced examination of canonization within translation studies with regard to the Cinderella story translations in China.

Both translation and literary scholars have scrutinized the inherent dynamics in the process of literary works becoming canonized via translation. There is increasing agreement that literary quality is merely one of the influencing factors, on the basis of the eloquent argument that “judgments of quality are extremely context-bound” (Baker and Saldanha, 2020, p. 54). Upon consensus and contentions alike, this study probes into the compromises and trade-offs in the process of cross-cultural canonization via tri-cultural-rooted translations to unfold the inherent nature and possible influencing factors and mechanisms of canonization via translation.

The following part of the study presents how the data is collected for analysis. The data components, selection criteria, and analytical details are described. The next section then presents the ATU classification and the prototype theory as the study’s analytical methodology. Based on the methodology, an adapted prototype framework is proposed for the discussions and investigations of the factors for the canonization of Huiguniang in China.

Methodology

The data

The Chinese-origin story of Cinderella and three Chinese translations of Cinderella from different source languages of different times were collected as the dataset (Table 1). The selection was made based on the diachronic and synchronic considerations in line with the research questions, a period covering from 803 to 863 BCE to its recognized heyday from 2004 to the present. The Chinese-origin story of Cinderella is the story of Ye Xian authoured by Duan Chengshi dating from 803 to 863 BCE. The three Chinese translations contain the first translation by Sun (1913) from the French Les Contes de la Mere L’oye (Perrault, 1697), the translation by Wei (1934) from the German Kinder-und Hausmärchen by Grimm (1812), and the more recent German translation listed in Chinese primary children’s textbooks. The footnote in the textbook alleges that the presented version is an adaptation from the Grimms’ German version. However, the translator remains unspecified in the book; therefore, this paper refers to the translator as the Editorial Board. To quantitively and qualitatively analyse the micro-level features displayed in these diverse versions, this study breaks down the story into the shortest possible sentences as the analytical unit in the identification of the prototypical motif distribution. This attempt follows the technique of the basic structural analysis of myth and fairy tales proposed by Lévi-Strauss (2008).

ATU classification and the prototype theory

Folktales are composed of different variations on limited themes. In the classification of folklore, scholars have proposed various systems to reveal the similarities between stories by grouping the variants of the same story into categories (Garry, 2017; Dundes, 1997). This study resorts to the ATU classification, a catalogue and classification of folktale types established in folklore research. The classification adheres to the “one story one classification” (Tangherlini, 2013, p. 15) system and retrieves information on certain shared features of folktale characters and actions. Altogether, there are 2399 tale types falling into seven broad categories: Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, Realistic Tales, Tales of the Stupid Ogre (Giant, Devil), Anecdotes and Jokes, and Formula Tales. The Cinderella story falls into the category of Tales of Magic. The ATU classification was first developed by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne using the historical geographic method. Further revised by American folklorists Thompson and Uther, the ATU classification (Thomson, 1966) was finalized as an indispensable tool for folklorists to make explicit the similarities between different tales via the identification of distinctive motifs.

Within the ATU classification, the Cinderella story belongs to the ATU510 type, that is, Tales of Magic embodies Magic Helpers. The ATU510 type is entitled Cinderella and Cap o’ Rushes, a combination of Cinderella tales and the fairy tales of Cap o’ Rushes. This study, with a specific focus on Cinderella stories, extracts elements relevant to the analysis of the Cinderella story as outlined below.

I. The Persecuted Heroine. (a) The heroine is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters and (a1) stays on the hearth or in the ashes and (a2) is dressed in rough clothing—such as a cap of rushes or wooden cloak.

II. Magic Help. While she is acting as a servant (at home or among strangers) she is advised, provided for, and fed (a) by her dead mother, (b) by a tree on the mother’s grave, (c) by a supernatural being, (d) by birds, or (e) by a goat, a sheep, or a cow. When the goat (cow) is killed, a magic tree springs up from her remains.

III. Meeting the Prince. (a) She dances in beautiful clothing several times with a prince who seeks in vain to keep her, or she is seen by him in church. (b) She gives hints of the abuse she has endured as a servant girl. (c) She is seen by the Prince in her beautiful clothing in her room or the church.

IV. Proof of Identity. She is discovered through (a) the slipper-test or (b) through a ring which she throws into the prince’s drink or bakes in his bread, or (c) she alone is able to pluck the gold apple desired by the knight.

V. Marriage with the Prince. The above-extracted classification is adopted to further identify the conceptual cores and other category members in the Chinese translations of Cinderella. For example, the sentence “灰姑娘和王子的婚礼在教堂举行(Cinderella and the prince’s wedding was held in the church)” would be coded into the “Marriage with the Prince” motif. These five types of themes or motifs, defined as “usually recurring salient thematic elements” (Han, 2014, p. 21), are labelled as prototypical features in the identification of conceptual cores in the story of Cinderella. Subsequently, this study examines the occurrences of different types of prototypical features in different translated versions for a more meticulous comparison.

This study adapts the framework of prototype theory (Langacker, 1987; Aarne, 2018) in folklore literature to explain the observed prototypical feature changes and shifts in the canonization process. The core concept schema of the prototype theory, according to Langacker (1987), “is an abstract characterization that is fully compatible with all the members of the category it defines”. Regarding the members of the defined category, it is agreed that “categories are represented in the mind in terms of prototypes” (Lakoff, 2007, p. 132), where a prototype is a conceptual core and other entities are “determined by their degree of similarity to the prototype” (p. 132). The other less kernel entities are clustered as extensions but are still category members of the schema.

The interconnections among “schema”, “prototype”, and “extension” show that “prototype” and “extension” are members of “schema”. The arrows in the diagram disclose their relationships where the schema is the compatible abstract characterization from prototypes and extensions (Fig. 2). “Prototype” and “extension” exert influence on each other, and the possibility of superseding could exist. Within “prototype” and “extension”, various motifs could be identified through the catalogue of ATU (Aarne, 2018) to conduct a thorough and copious prototypical analysis in both synchronic (i.e., the examination of prototypical features of Cinderella stories without factoring in historical contexts) and diachronic (i.e., the examination of prototypical features of Cinderella stories across historical spaces) feature shifts.

Overall, this study adopts the cognitive prototype theory (Langacker, 1987) as well as the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) classification of folk tales (Aarne, 2018) from the folklore domain to elucidate the canonization process for the journey of Cinderella in China over a thousand years.

Prototypical differences

This section entails the prototypical feature analysis of the four Cinderella stories in China. The results are presented and analysed both quantitively with regard to sentence distribution patterns and qualitatively within certain prototypical features.

Preliminary sketch of the prototypical features

A synchronic motif comparison

Altogether there are 43, 80, 120, and 35 sentences in the translations and adaptations by Duan, Sun, Dai, and the Editorial Board, respectively (percentages shown in Table 2). The distribution of sentences are categorized and added up in terms of the five prototypical features proposed in the ATU classification of folk tales—“The Persecuted Heroine”, “Magic Help”, “Meeting the Prince”, “Proof of Identity”, and “Marriage with the Prince” (Thomson, 1966). Not all the sentences in different translations fall into these five categories, resulting in divergent totals.

For the synchronic comparison among the four versions, the prototypical feature “Magic Help” is the most salient motif ranking top in terms of sentence distribution with percentages of 27.91, 25.00, 20.00, and 22.86. The salient feature of “Magic Help” conforms to the miraculous feature of fairy tales: as Zipes (2012) convincingly attests, fairy tales are “universal, ageless, therapeutic, miraculous, and beautiful”. They have always been a typology of powerful discourse, capable of being used to shape attitudes and behaviour within different cultures.

Conversely, the “Marriage with the Prince” feature observed in the four versions is similar in the total sentence number, that is, only one or two sentences making up the lowest percentage among the five prototypical features (Fig. 3). The remaining three prototypical features are largely in-betweens among the two edges in terms of sentence numbers and percentages with few remarkable changes. This synchronic comparison highlights the “Magic Help” feature, echoing the typology of Cinderella in the ATU510 type “Magic Helpers”.

Correlation of different translations in terms of prototypical features

A comparison between correlations of the different versions provides hints on the relationships of different versions and on the explanations of how Huiguniang became a household name in China.

Duan’s version and Sun’s translation share a similar distribution pattern in the rankings of each prototypical feature. As shown in Table 3, Duan and Sun are significantly correlated, r = 0.93, p < 0.05. The Pearson Correlation value of their distributions is very close to 1, indicating that these two versions are highly correlated. This statistical correlation offers a further explanation for the survival, popularity, and final canonization of Cinderella in China. That is, one of the prerequisites for canon formation is that canon literature is a type of literature shared by a group (Baker and Saldanha, 2020). An assumption could be made that because the Cinderella story from the west is similar to the Chinese Cinderella story The tale of Ye Xian by Duan, the retranslations and popularizations of the Cinderella story in China became possible.

However, the canonized version surprisingly is not statistically correlated to any of the previous versions in terms of the prototypical feature distributions. As discussed in ‘Literature review’, the fourth version of the textbook was adapted from German versions by the Editorial Board and is regarded as the canonized version. Contradictory to the intuition that the original and adapted texts have close connections and resemblance (Corrigan, 2017), the correlations among the Editorial Board and other versions are not statistically significant. Thus, to further probe into this discrepancy, this study conducts a detailed diachronic comparison of their prototypical differences.

Diachronic overview of the prototypical features

A diachronic comparison among all the renderings exhibits a significant result. Over the centuries, there has been a slight rise of percentage in the “Marriage with the Prince” feature (Fig. 4). The “Meeting the Prince” and “Proof of Identity” features also see slow but steady increases of 15.35% and 11.23%. The only decreased prototypical feature is “Magic Help”, dropping slightly from 27.91 to 22.86%.

Wei’s translation is observed as a key element among the four versions. A marked rise and a following fall are observed in “The Persecuted Heroine” feature in the translations by Wei and the Editorial Board. A sharp increase in sentence numbers and percentages from Sun to Wei could possibly imply a move in the category member, “The Persecuted Heroine”, from a peripheral position to a more central one. On the other hand, the translation by Wei could be seen leading the changes for the following reason: After its 1934 heyday of 20% by Wei, a reasonable decline followed till the percentage reached 8.75, still higher than the original 4.65%. The rendering by Wei is therefore a key element in the process of the canonization of Cinderella in China, at least exerting a potential influence on the canonized prototypical features.

To get a full view of the changes of particular prototypical features of Cinderella in China, Fig. 5 compares the difference in percentage score for each of the prototypical features on average (AVE) and the Editorial Board (EB). The canonized Cinderella story in Chinese textbooks gives greater prominence to the positive, optimistic, and hopeful features of “Meeting the Prince”, “Proof of Identity”, and “Marriage with the Prince”. Conversely, the features entailing negative denotations or plots are reduced trivialized via the percentage deduction in “The Persecuted Heroine” and “Magic Help”. To sum up, the tendency is that positive prototypical features are highlighted while negative prototypical features are given less prominence in the canonization of the Cinderella story in China.

Shift within “The Persecuted Heroine” feature

This section examines in detail the salient features of “The Persecuted Heroine”, whose position moves from the periphery to a more central one in the target literary system as discussed in ‘Diachronic overview of the prototypical features’. Based on the ATU classification of folk tales (Aarne, 2018), “The Persecuted Heroine” is composed of three subcategory features: (a) the heroine is abused by her stepmother and stepsisters and (a1) stays on the hearth or in the ashes and, (a2) is dressed in rough clothing, such as a cap of rushes or a wooden cloak. The examples below are the representative sentences occurring in several versions under “The Persecuted Heroine” feature at different times.

Example 1

TT: 二姊亦奴畜之。辛度利拉蓬頭跣足, 充灶下婢妾而已。(Sun, 1913, p. 37)

Back translation (BT): Her two sisters also abused her. Xindulila was unkempt and was treated like a slave in the kitchen.

Example 2

TT: 她们跟她开玩笑,把莞豆和扁豆倒在灰里,使她不得不坐着把它们拣出来。晚上, 她工作得疲倦的时候,没有床睡觉, 只得躺在灶旁的灰里。(Wei, 1934, p. 70)

BT: They joked with her and dumped the peas and lentils in the ashes so that she had to sit and pick them out from the ashes. At night, when she was tired from work, she had no bed to sleep in, so she had to lie in the ashes by the stove.

Example 3

TT: 从此, 可怜的小姑娘成天穿着一件灰褂子, 满身灰尘, 满脸污垢。(Editorial Board)

BT: From then on, the poor little girl wore a grey gown all day long and was covered with dust and had dirt on her face.

Beyond the quantitative data signifying the tendency of the prototypical feature “The Persecuted Heroine” to shift from a peripheral position to a more central one, these examples describe an abused image of Cinderella who stays in the ashes and dresses in rough clothing. All these examples showcase the increasingly highlighted (a1) characteristic: she stays on the hearth or in the ashes. From the tangible ashes in the kitchen (灶下, 灶旁的灰里) to the designed plot of picking lentils from ashes (从灰里拣着扁豆) and the colour of grey in the heroine’s clothes (灰褂子), we can see a salient image of a girl who stays on the hearth or in the ashes. In this process, the image in Wei’s translation functions as an extension to the image constructed in previous translations.

The disappearance of negative connotations in protagonist’s name

Although both the quantitative and qualitative analysis present the seemingly negative image of Cinderella, this study observes its positive image reception in China: the negative connotations associated with the protagonist’s name, Huiguniang, particularly in its first part, Hui, appear to be disappearing. The three basic senses of the Chinese character hui (灰) are as follows: (1) grey, the colour of light black; (2) ash, the powder left over after an object burns; (3) dust. The extended meaning of the character also includes “dirty”, such as huitata (灰遢遢, dirty and disorderly appearance), huirongtumao (灰容土貌, describing a dirty and ugly face) and spiritually depressed in the case of huixin (灰心, low spirit and discouraged). The main semantic prosody of words containing the Chinese character hui would therefore possibly entail a negative representation. However, in the case of Huiguniang as a compound word, the negative connotation of hui is fading. Instead, Huiguniang represents a girl with a poor family background who often fails to get due attention, but finally becomes a success in life with the heroine’s value measured in terms of her kindness, elegance, and beauty (Harwood, 2008). The overall significance lies always in the triumphant reward.

Notwithstanding that the prototypical feature of “the heroine always staying on the hearth or ashes” becomes a more prominent part of the schema, it should not be interpreted as a movement towards the conceptual core. Since “a schema is an abstract characterization that is fully compatible with all the members of the category it defines” (Langacker, 1987, p. 371), the triumphant reward in the schema is the eternal conceptual core in the Chinese context. The moment Huiguniang comes to the Chinese reader’s mind, the foremost identified prototypical feature would be the conceptual core (i.e., the triumphant reward). As a result, the negative connotation of hui, in this case, is temporarily obscured. Such disappearance of hui’s negative connotations legitimates its canonization in China where the mainstream tends to be positive overall (Kong, 2005).

Legitimization of the proper noun Huiguniang

The most evident manifestation of “The Persecuted Heroine” feature and the disappearance of hui’s negative connotations is shown in the names of the heroine. The name of the heroine also shifts from the original Yexianguniang (叶限姑娘) to transliterated Xindulila (辛度利拉) and is finalized as the household Huiguniang (灰姑娘) as shown in Fig. 6. Transliteration of the names of foreigners was common and legitimate in early 20th century China (Lu, 2020). The name of the heroine is therefore translated as Xindulila under the phonetic implicature embedded in the source text Cendrillon. In a similar way, Wei’s rendering from German versions borrows the denotation of Asche from Cinderella’s German name Aschenputtel. The Cambridge dictionary explains Asche as: (1) the dust that remains after anything is burnt; (2) the remains of a human body after cremation; (3) a piece of burnt coal, wood. The denotations are perfect matches for the Chinese character hui as translated by Wei (1934), and Huiguniang has been widely accepted and become an integral household name among Chinese children.

Moreover, a co-occurrence analysis helps to contextualize the proper noun and show words with similar appearance patterns. It is a useful method providing hints on the legitimization process and outcomes of Huiguniang. Consequently, the previous analysis is extended by generating and analyzing co-occurrence networks (Fig. 7) via KH Coder (Higuchi, 2016), a software utilized in the field of computational linguistics to analyze the co-occurrence network with a diagram that shows the words with similar appearance patterns. In line with the technique of the structural analysis of myths proposed by Lévi-Strauss (2008), the analysis in this study is conducted at sentence-level instead of the preassigned paragraph level. The word Huiguniang (灰姑娘) in the network is labelled as a proper noun automatically by the system, another testimony of the word as an integral household name. The co-occurring character of Huiguniang is the prince, whose partner is generally acknowledged as the princess, an appellation full of positive happiness, felicity, and blessings. In addition, the co-occurrences of Huiguniang and Prince can be seen as a vigorous affirmation of the previously observed disappearance of negative denotation.

Investigating the factors for the canonization of Huiguniang in China

In comparison to other prescriptive studies proposing an alternative translation for some fairy tales (Rojas-Lizana et al., 2018), this study adopts a descriptive perspective to unfold the canonization of Cinderella in China. Under the adapted framework of Langacker (1987) and Aarne (2018) of prototype theory within folklore literature, it is found that: (1) all versions contain the same category of prototypical features; (2) the canonized version is surprisingly not statistically correlated to any of the previous versions in terms of prototypical feature distributions; and (3) within the salient “The Persecuted Heroine” feature, there is a disappearance of negative connotations and the legitimization of proper nouns.

In detail, the marked prototypical differences in the Chinese Cinderella stories are identified and further probed in both preliminary synchronic-diachronic sketches and additional observation within “The Persecuted Heroine” feature. The synchronic motif comparison indicates that “Magic Help” is the most salient prototypical feature. It is easy to neglect the fact that there is no absence of any of these five prototypical features. The correlation index among different versions showcases the highly correlated relationship between the Cinderella stories by Duan and Sun. However, the canonized Editorial Board version is not statistically significant to any of the previous versions. Such pronounced loose correlation invites a diachronic exploration towards their prototypical differences. In the diachronic observation, “The Persecuted Heroine” had the most significant changes, from a peripheral position to a more central one, with Wei’s translation taking the lead. The subsequent qualitative analysis within “The Persecuted Heroine” feature discloses the disappearance of hui’s negative connotations as well as the legitimization of the proper noun Huiguniang.

Overall, the findings present the details of Cinderella’s evolving trajectory in China. However, a generalization of the seemingly trivial results is needed to get a holistic viewpoint of this evolving trajectory. By operationalizing the triangulation among “Schema”, “Prototype”, and “Extension” from the cognitive domain, this section aims to generalize and investigate the factors for the canonization of Huiguniang in China. The following discussion envisages the external stability and the internal dynamic trade-offs among translations in the process of canonization. In addition, the iterative nature and empowerment of translation on literary canon is highlighted.

External stability in canonization

Considering that the journey of Cinderella in China concerns the exceptional phenomena of a piece of canonized translation having roots in more than one foreign culture (i.e., Germany and France), one might ponder how these different cultures unite and co-exist in one story. The synchronic overview presents the non-absence of all the prototypical features despite minor nuances within the flow of the story. Such all-inclusive and congruent considerations observed in the process of canonization via translation indicates the external stability when diverse cultures are involved. This is similar to Baker and Saldanha (2020)’s view that canon works (literature shared by a group) develop as a collective cultural process in canonization. Although some scholars have argued that foreign works introduce features “into the home literature which did not exist there before” (Even-Zohar, 1990, p. 47), the western Cinderella story, in this study, is imported into Chinese culture under the rationale of the existence and external stability of shared prototypical features and motifs in China and the west in the ancient Yexianguniang (803–863 BCE) and the folklore Cendrillon (1697) by Charles Perrault.

Internal dynamic trade-off

In addition to the external stability in the canonization process, this study also observes an internal dynamic trade-off among different works in the previous quantitative and qualitative analysis. The dynamics of canon, as expounded by Baker and Saldanha (2020), are adequately confirmed via the observed motif shifts from peripheral positions to prototypical cores (“Meeting the Prince” and “Proof of Identity”) and from prototypical cores to more peripheral positions (loss of negative denotation in “The Persecuted Heroine”). Meanwhile, translation is also expounded as “a dynamic reflection of human activities” (Newmark, 2003, p. 57) where a dynamic notion is highlighted in the canonization process.

This trade-off is explicit in the prefaces and the translated texts by different translators, presenting conflicting agendas in importing foreign literature from different cultures. In Sun (1913) preface, he expounds on the complicated relationship of literature, novels, and fairy tales while introducing the history and development of fairy tales in China. Sun’s translation is therefore targeted at intellectuals with a knowledge of literature, with the intention of arousing the public’s interest and awareness of the importance of fairy tales. Conversely, the frequent mention of children in Wei (1934) preface indicates a different audience from Sun’s targeted intellectuals. Wei justifies his deletion of the few versed aphorisms at the end of each story to avoid their moral concepts, with his view that they would restrain the lively and imaginative souls of children. Wei’s efforts in bringing a vivid and modern work to the children of 1930s China engenders the choice of colloquial 姑娘(Guniang) rather than the previously used formal 女(Nv) in the title. Li (2014) assertion that “no literary movement can escape the influence of the domestic social, political, and poetical contexts within which it happens” (Li, 2014, p. 120) indicates that adult-orientated considerations to children-oriented rationales were influenced by a change in the social-cultural background following the May Fourth Movement in China.

The iterative nature and empowerment of translation in the literary canon

It is uncommon for a story such as Cinderella to originate from three cultures (Chinese, French, and German). Thus, this study propounds a more inclusive perspective on the exploration of the exhaustive possibilities in canonization and translation research. Apart from its external stability and dynamic nature, the multicultural scrutinization of the prototypical features of different translations reveals the iterative nature of canonization in the Chinese Cinderella story (Fig. 8). The empowerment of translation on the literary canon will subsequently manifest itself.

The German translation by Wei (1934) into Chinese is an extension in terms of the prototypical features and conversely influences the prototype constructed through the French translations by Sun (1913). The motif of the “heroine always staying on the hearth or ashes” becomes a more prominent part of the schema as discussed in ‘Internal dynamic trade-of’. The potential of the extension could exceed the central prototype in many areas including the ending of the translated Cinderella story. Sun’s 1913 translation states: “although Cinderella’s stepsisters were jealous, they could do nothing about it” (p. 39); whereas Wei’s 1934 translation states: “the stepsisters of Cinderella are punished as blind all their lives because they are vicious and cunning” (p. 75). Surprisingly, nothing in the German source text could be found narrating or hinting at the tragic ending of the stepsisters. The fabricated plot by Wei highlights the vicious and cunning characteristic of the stepsisters, strengthening the vivid contrast with the “quiet and grateful” image of Cinderella (Sun, 1913, p. 39). Wei’s translation therefore facilitates the loss of negative denotation and the shift from prototypical core to a more peripheral position of “The Persecuted Heroine”. The movement of the rendering by the Editorial Board to the central position (“prototype”) is also self-explanatory as it has become the current canon among Chinese children today.

The diachronic recap of the ancient Chinese Cinderella story as well as the three translations together denote the iterative nature of canonization. It is reasonable to anticipate the emergence of a new canon in the Cinderella story in the years to come as well as shifts of its prototypical core, with the current canon of the textbook translation by the Editorial Board becoming merely an extension rather than the prototype in the Cinderella story in the future.

To sum up, the canonization of literature, either consciously or unwittingly, can be legitimated, induced, or altered by translated works. The importance of understanding translation production, circulation, and readership, as highlighted by Bassnett (2018), is reinforced in this study through the discussion of the empowerment of translation and extension, not only as a means of motivating peripheral prototypical features to a more central position but also as a bedrock supporting other prototypical features in holding their existing status.

Conclusion

Although there are cases of retranslations of canonized translations that have failed to take root (Baker and Saldanha, 2020), this study elucidates the canonization process of Cinderella in China where the potential of multi-cultural retranslations is recognized. Based on the evidence of change, correlations, and shifts in prototypical features, the study reveals a stable, dynamic, and iterative evolving trajectory of Huiguniang in China. This research contributes to literary and translation studies in the following ways: First, it extends the research object for both literary and translation studies by introducing and analysing a literary work with tri-cultural involvement and multiple source texts origination. Second, it highlights the external stability, internal dynamic trade-offs, and the iterative nature and empowerment of translation in the popularization and canonization of Huiguniang in China. This can help understand the process and factors in the canonization of other literary works.

However, this study examines only the written record of the Cinderella story in China for accuracy and consistency. The oral Chinese Cinderella stories (Chen, 2020) are also a field of genuine interest that should be explored. If both the written and oral Chinese Cinderella stories are considered, future study may either confirm or contradict the findings of the present study. Moreover, canonization in genres beyond literary (e.g., speeches) may exhibit novel observations that could indicate further limitations of this study that focuses purely on children’s literature. This could be another avenue of investigation.

For further research, the emergence of new translations of the Cinderella stories in China, either in textbooks or elsewhere, may produce further insightful results. There is also the possibility of the currently canonized Cinderella story being removed from the Chinese textbook series. Such a possibility would allow potential follow-up research to investigate or testify the external stability, internal dynamic trade-offs, and iterative nature in the canonization of literary works observed.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the author on reasonable request.

References

Aarne A (2018) Aarne-thompson-uther classification of folk tales. Multilingual Folk Tale Database. Available online: http://www.mftd.org/index.php. Accessed on 12 Jan 2023

Altieri C (1983) An idea and ideal of a literary canon. Crit Inq 10(1):37–60

Anderson G (2002) Fairytale in the ancient world. Routledge, Abingdon

Baker M, Saldanha G (2020) Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies. Routledge, Abingdon

Bassnett S (2018) Translation and world literature. Routledge, Abingdon

Baum R (2000) After the ball is over: bringing Cinderella home. Cultural Anal 1:69–83

Beauchamp F (2010) Asian origins of Cinderella: The Zhuang storyteller of Guangxi. Oral Tradition 25(2)

Ben-Amos D (2010) Straparola: the revolution that was not. J Am Folk 123(490):426–446

Bloom H (2014) The western canon: The books and school of the ages. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston

Cawelti JG (1997) Canonization, modern literature, and the detective story. CONTRIBUTIONS STUDY POPULAR CULTURE 62:5–16

Chen FPL (2020) Three Cinderella tales from the mountains of southwest China. J Folk Res 57(2):119–152

Chou I and Liu K (2023) Style in speech and narration of two English translations of Hongloumeng: a corpus-based multidimensional study. Target. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.22020.cho

Classen A (2011) Problematics of the canonization in literary history from the middle ages to the present. The case of Erasmus Widmann as an example–The victimization of a poet oddly situated between epochs, cultures, and religions. Stud Neophilol 83(1):94–103

Corbin JM, Strauss A (1990) Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociol 13(1):3–21

Corrigan T (2017) Defining adaptation. Oxford University Press, New York

Cullen B (2003) For whom the shoe fits: Cinderella in the hands of Victorian writers and illustrators. Lion Unic 27(1):57–82

De la Rochère MHD (2016) Cinderella across cultures: New directions and interdisciplinary perspectives. Wayne State University Press, Detroit

Dundes A (1997) The motif-index and the tale type index: A critique. J Folklore Res 195–202

Even-Zohar I (1990) The literary system. Poetics today 11(1):27–44

Even-Zohar I (2021) The position of translated literature within the literary polysystem. The Translation Studies Reader. Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 191–196

Farquhar M (1999) Children’s literature in China: from Lu Xun to Mao Zedong. Routledge, Abingdon

Fokkema DW (1982) Comparative literature and the new paradigm. Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée. 1–18

Garry J (2017) Archetypes and motifs in folklore and literature: A Handbook. Routledge, Abingdon

Gould R (2014) Conservative in form, revolutionary in content: Rethinking world literary canons in an age of globalization. Can Rev Comp Lit/Rev Canadienne de Littérature Comparée 41(3):270–286

Grimm J (1812) Wilhelm: Kinder-und Hausmärchen. Engel, Munich

Han S-K (2014) Motif of sequence, motif in sequence. Advances in sequence analysis: Theory, method, applications. Springer, pp. 21–38

Hansen W, Fawkes G (2019) The Book of Greek and Roman Folktales, Legends, and Myths. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Harwood D (2008) Deconstructing and reconstructing Cinderella: theoretical defense of critical literacy for young children. Language Literacy 10(2)

Higuchi K (2016) KH Coder 3 reference manual. Ritsumeikan University, Kioto (Japan)

Jameson R (1988) Cinderella in China. Cinderella: a casebook. 71-97

Kelly AV (2009) The curriculum: Theory and practice. Sage, California

Kolbas ED (2018) Critical theory and the literary canon. Routledge, Abingdon

Kong S (2005) Consuming literature: Best sellers and the commercialization of literary production in contemporary China. Stanford University Press, California

Lai A (2007) Two translations of the Chinese Cinderella story. Perspectives 15(1):49–56

Lakoff G (2007) Cognitive models and prototype theory. The cognitive linguistics reader. 130–167

Langacker RW (1987) Foundations of cognitive grammar: Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford university press, California

Lauter P (1991) Canons and contexts. Oxford University Press, New York

Leclère A, Feer L (1895) Cambodge: Contes et légendes. Librairie Émile Bouillon

Lefevere A (2016) Translation, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, Abingdon

Lévi-Strauss C (2008) Structural anthropology. Basic books

Li D (2014) The influence of the Grimms’ fairy tales on the folk literature movement in China (1918–1943). Grimms’ Tales around the Globe. 119–133

Li D, Zhang C, Liu K (2011) Translation style and ideology: a corpus-assisted analysis of two English translations of Hongloumeng. Lit linguistic Comput 26(2):153–166

Li H, Yang W, Chen JJ (2016) From ‘Cinderella’ to ‘Beloved Princess’: the evolution of early childhood education policy in China. Int J Child Care Educ Policy 10(1):1–17

Li L (2013) The afterlife of the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales in China. Babel Rev Int de la Trad / Int J Translation 59(4):460–472

Louie A-L (1982) Yeh-shen: A Cinderella story from China. Penguin, London

Lu X (2020) Refeng. Beijing Book Co. Inc, Beijing

Luo X, Zhu J (2019) The translation of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales in China: a socio-historical interpretation. Babel 65(2):153–174

Manggala SA (2017) The transitivity process patterns and styles in the characterization of the protagonist character in Phuoc’s “the story of Tam and Cam. J Lang Lit 17(1):65–73

Marzolph U, Van Leeuwen R, Wassouf H (2004) The Arabian nights encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, California

Moratto R, Liu K, Chao D-K (2022) Dream of the Red Chamber: Literary and Translation Perspectives. Taylor & Francis, Oxfordshire

Newmark P (2003) No global communication without translation. Translation today: Trends and perspectives. 55–67

Perrault C (1697) Histoires, ou Contes du Temps passé. Edition Claude Barbin, Paris

Qinbing T, Dongfeng T (2021) Construction, deconstruction and reconstruction of literary canons. BEIJING BOOK CO. INC, Beijing

Rigney A (2012) The afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the move. Oxford University Press, New York

Rojas-Lizana S, Tolton L, Hannah E (2018) “Kiss me on the lips, for I love you” Over a century of Heterosexism in the Spanish translation of Oscar Wilde. Int J Comp Lit Translation Stud 6(2):9–18

Sun Y (1913) 歐美小說叢談(Discussions on European Literature). 小說月報 (Fiction Monthly) 6(4):37–39

Tangherlini TR (2013) The folklore macroscope: Challenges for a computational folkloristics. Western Folklore. 7–27

Thomson S (1966) Motif-index of folk-literature: A classification of narrative elements in folktales, ballads, myths, fables, mediaeval romances, exempla, fabliaux, jest-books and local legends. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Venuti L (2013) World literature and translation studies. In: D’haen T, Damrosch D and Kadir D (eds) The Routledge companion to world literature. Routledge, London & New York, p 180–193

Waley A (1947) The Chinese Cinderella story. Folklore 58(1):226–238

Wei Y (1934) 格林童話(Grimm’s Fairy Tales). People’s Literature Publishing House, Beijing

Yu S (2020) Translation and canon formation. Forum Rev Int d’interprétation et de Trad / Int J Interpretation Translation 18(1):86–104

Zhou S, Moody A (2017) English in the voice of China. World Englishes 36(4):554–570

Zipes J (2012) Fairy tales and the art of subversion. Routledge, Abingdon

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL and DL initiated, refined, and contextualized the research idea collectively. YL wrote the initial manuscript, performed dataset analysis, statistical assessments, and visual representations. DL provided guidance throughout the paper’s development and contributed research insights.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Li, D. Intersecting language and society: a prototypical study of Cinderella story translations in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 223 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02719-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02719-w