Abstract

Despite the role of ethical voice in promoting ethics in working units, scant attention has been devoted to the emergence and boundary conditions of collective ethical voice. In accordance with the integration between regulatory focus theory and social identity theory, this research explores the antecedents and moderators of promotive ethical voice and prohibitive ethical voice in working units. Hierarchical regression analysis of field data on 632 employees and 62 leaders at three Chinese organizations supports the hypotheses. Faultlines negatively relate to promotive ethical voice and prohibitive ethical voice in groups. Role ambiguity moderates the effect of two forms of ethical voice on citizenship behaviors and task performance in groups. Based on regulatory focus and social identity theory, this study contributes to existing research by revealing faultlines to be barriers of collective promotive and prohibitive ethical voice. Additionally, this research provides a novel lens to understand the underlying interaction mechanisms through which role ambiguity regulates the effect of ethical voice on performance in groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A number of well-known companies have reported unethical behaviors and financial fraud every year, damaging their reputation and public trust (Kim and Vandenberghe, 2020). This has led to calls from researchers and practitioners for the prevention of unethical conduct (Kim et al. 2023; Zheng et al. 2022). As a response to ethical reform within organizations, groups, as the most basic unit of an organization, need to understand their members’ ethical views as expressed in daily communication. One way that groups can develop such understanding is through the ethical ideas that group members present. This is referred to as group ethical voice, which is defined as group members speaking up about their concerns regarding the violation of ethical norms and their suggestions about sustaining ethical norms (Chen and Treviño, 2022; Ogunfowora et al. 2022).

In recent years, research interest in group ethical voice has increased dramatically (e.g. Chen and Treviño, 2023; Kim et al. 2023; Ogunfowora et al. 2022; Kim and Vandenberghe, 2020; Huang and Paterson, 2017). However, somewhat surprisingly, with a few exceptions (Chen and Treviño, 2022), the literature on group ethical voice has typically focused on broader or overall perspectives that do not clarify the different perspectives within group ethical voice. In this study, we heed the call of Ogunfowora et al. (2022) to specify the dimensions of group ethical voice based on promotion and prevention (or prohibition) type regulatory focus. In particular, this effort helps to develop a theoretical framework that considers the causes and boundary conditions of group promotive and prohibitive ethical voice.

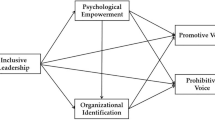

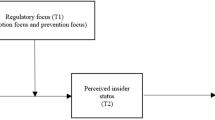

Based on the promotion and prevention distinction advanced by regulatory focus theory, group ethical voice can be classified into two forms: promotive voice (speaking to what ethical behaviors should do) and prohibitive voice (speaking to what unethical behaviors should not do) (Chen and Treviño, 2023). As group members’ regulatory focus on ethical voice depends on how they connect with group identity and whether the group supports their regulatory focus (Newheiser et al. 2015), we propose an integration of social identity theory and regulatory ethical focus. In this regard, we explore the antecedents of our two forms of group ethical voice based on the social categorization perspective of social identity theory by testing the role of activated group faultlines, which are defined as perceived dividing lines that categorize group members into different subgroups based on similarities or differences in personal attributes (e.g., age and gender) (Lau and Murnighan, 1998). Furthermore, we also explore the boundary condition of the relationship between two forms of group ethical voice and group-level organizational citizenship behaviors (GOCB) and group task performance based on the basic motivation of social identity theory (uncertain consideration) by examining the moderating role of group role ambiguity, which is defined as a lack of necessary information about a given group position (Cicero et al. 2010) (Fig. 1).

Overall, our study makes several contributions to the research on (non)emergence of group ethical voice based on social identity theory. First, we explain why group members fail to display ethical voice from the perspective of group faultlines. Despite the importance of group ethical voice, it is often perceived as risky and difficult to speak up on ethical grounds in the group context because of the fear of invalidation (e.g. “no one will listen”, “nothing will change”) or danger (e.g. “any voice can be punished”) (Satterstrom et al. 2021). This fear reflects a lack of intra-group psychological connection (Satterstrom et al. 2021). According to social identity theory, invalidation of voice and danger of voice as manifestations of a lack of intra-group psychological connection are reflections of intra-group psychological boundaries and group (non)identification (Chamberlin et al. 2017). Empirical studies on social identity theory have demonstrated that the higher the level of group identification, the more likely group members are to speak out on ethical grounds, i.e., engage in an ethical voice (Chamberlin et al. 2017; Burhan et al. 2023; Johnson et al. 2023). However, no studies have considered the (non)emergence of ethical voice from the perspective of intra-group psychological boundaries, especially subgroup psychological boundaries. It is still unclear how group members interact with each other and think about each other from ethical perspectives based on subgroup categorization processes. Without such understanding, leaders may hardly to know why group members’ voice in ethical ground is narrowly focused (the focus on few subgroup members rather than entire group members). According to social identity theory, social categorization processes explain the barriers of voice as the formation of inter-subgroup boundaries (inter-subgroup hostility) based on subgroup categorization, along with the alignment of members’ multiple attributes (e.g., age and gender) (Ulrich et al. 2021; Chen and Wang, 2021), which can be referred to as group faultlines (Wu et al. 2021). Qi et al. (2022b) indicated that group faultlines, a typical informal group structure, are an integral part of intra-group activities and provide a setting for information expression and analysis. In this study, we focus on the relationship between group ethical voice and group faultlines. Our study not only provide evidence for the connection between social categorization processes in social identity theory and regulatory focus theory but also clarify why group members’ ethical voice is constrained from the perspective of intra-group boundaries.

Second, our research breaks new ground by testing a boundary condition (group role ambiguity) regarding the influences of two types of group ethical voice. Group role ambiguity represents group members’ perception of group uncertainty (Carlson and Ross, 2022). Social identity theory suggests that environmental stability and certainty represent individuals’ basic motivation to connect with the collective identity (Wu et al. 2021) and whether they care about group ethical voice. Whether team members view higher levels of environmental (un)stability and (un)certainty from the perspectives of gains or losses regulates the individual group member’s regulatory focus (Jiang et al. 2020). Hambrick et al. (2005) support this view, stating “executives vary widely in their abilities and in the suitability of their talents for the specific environmental conditions they face” (p. 475). Limited past studies have explored the moderating role of uncertainty on regulatory focus (Jiang et al. 2020). They mainly focus on macro organization or industry background through objective secondary data and are inspired more by the person-environmental regulatory (mis)fit perspective than by social identity theory. However, these studies provide conflicting discussions regarding either positive or negative person-environmental regulatory (mis)fit. The inconsistent findings fail to result in solid conclusions about the interaction between regulatory focus and uncertainty. By applying group role ambiguity based on social identity theory, we extend the research focus from the macro organizational or industry level to the micro group level. This is because, based on the level-matched principle, group-level behaviors are more strongly related to the perception of group identity than they are to other levels of identity (e.g., personal identity or organization identity) (e.g., Qi et al. 2023). In addition, we challenge the basic argument of person-environmental regulatory (mis)fit (e.g., Jiang et al. 2020), which states that uncertainty may enhance the benefits of regulatory focus to some extent and confirm the “dark side” of uncertainty by testing group role ambiguity. Overall, we contribute to the integration of social identity and regulatory focus theory by extending the boundary conditions of group ethical voice from the person–environment regulatory (mis)fit perspective to the uncertainty perspective of social identity theory.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Group ethical voice

The study on the dimensions of ethical voice rests on two forms of regulatory focus: promotive regulatory focus and preventive regulatory focus. The former is defined as expressing new views to facilitate organizational functioning, while the latter is defined as expressing concerns about harmful actions to prevent organizational damage (Zheng et al. 2021). Regarding the ethical perspective, prohibitive-target ethical voice aims to focus attention on avoiding ethical issues, and promotive-target ethical voice is related to voicing suggestions for improving ethical functioning (Ogunfowora et al. 2022).

Given the apparent promotive and prohibitive distinction in the ethical voice literature and regulatory focus theory, we propose that group ethical voice can be either promotive or prohibitive. Group promotive ethical voice can be framed as group members providing new ethical ideas to improve the group. In contrast, group prohibitive ethical voice refers to expressing concerns about the negative ethical-related outcomes of the group (Chen and Treviño, 2022). During intragroup communication, each type of voice focuses on different information content. In ethical promotive voice, a positive tone is taken and positive information is advocated in communication (Chen and Treviño, 2023; Zheng et al. 2022). For example, the equality of female workers should be highlighted in group work. In ethical prohibitive voice, however, a negative tone is used and potential violations are highlighted in communication to reduce group costs (Kim and Vandenberghe, 2020). For example, gender discrimination should be avoided in group work.

Group faultlines

Faultlines represent a kind of group structure that captures the joint effect of multiple characteristics in defining subgroups (Ma et al. 2022). The strength of a group faultline increases when multiple demographic characteristics converge, thus further generating clear subgroups with a high level of between-subgroup differences and within-subgroup similarities (Shemla and Wegge, 2019). For instance, demographic faultlines can take the form of age-gender divides between senior females and junior males. When the strength of a group faultline is activated, subgroup boundaries become salient, and it then becomes easy for group members to perceive subgroup boundaries (Xie et al. 2015). Previous studies have revealed that group faultlines influence group processes and outcomes (e.g. Qi et al. 2022a; Wu et al. 2021; Yao et al. 2021). For example, they causes intragroup conflicts, leading to poor group performance and low-quality group learning and decision-making.

As Carton and Cummings (2012) emphasize, identity subgroups emerge when faultlines are created by demographic characteristics. In this study, we focus on two dimensions of demographic attributes that are likely to create subgroups within a group, namely, age and gender. This is because age and gender, as the most salient and easily activated attributes of group members (Leicht-Deobald et al. 2021), are central to individuals’ perceptions of similarities or differences (Li and Jones, 2018) because they are related to stereotypic beliefs (Qi et al. 2022a).

Group faultlines and group ethical voice

According to the propositions of social identity theory, collective regulatory focus is related to the prototypical collective identity (Newheiser et al. 2015). Group members’ preferences for promotion and prevention are affected by their attitudes toward in-categorization or out-categorization (Faddegon et al. 2008). In this regard, it is reasonable to develop an integrated theoretical framework reflecting the relationship between group faultlines and group ethical voice.

In groups with strong faultlines, polarization between members from different subgroups may occur (Ulrich et al. 2021). This leads to “behavioral disintegration” (Ndofor et al. 2015), which activates social discrimination and further regulates individuals’ perceptions and actions (Ma et al. 2022). As employees prefer to link themselves and others to the prototypes of the collective identity to which they belong (Choi and Hogg, 2020), group members within salient subgroups with strong faultlines tend to define themselves according to in-subgroup norms and adjust their own ethical voice based on subgroup porotypes (Antino et al. 2019). They may validate their ethical voice by isolating them from those voices held by members of out-subgroups. As a result, they easily neglect ethical voice originating from out-subgroup members. Even out-subgroup ethical voice raises their concern, and they may have a negative attitude or resistance toward them derived from out-subgroup hostility (Wu et al. 2021). This is in line with the social categorization perspectives of social identity theory that claim that out-subgroup members who are different from the individuals are seen as an invalid point reference for information processing (Rees et al. 2022). As ethical discussions are aggregated at the subgroup level, the range of ethical voice potentially available to the group is constrained.

In contrast, in groups with weak faultlines, the boundaries between the in-subgroup and out-subgroup are not obvious and being hard to detect because of the cross-alignment of multiple demographic attributes (Qi et al. 2023). Group members can easily find “common ground” among each other, which can reduce the bias and discrimination between subgroups (Yao et al. 2021). Furthermore, as subgroup identity with weak group faultlines is not salient, group members can transform their attention from subgroup identity to group identity and define themselves and others according to group norms rather than subgroup norms (Xie et al. 2015). As a result, group cohesion is stronger than the subgroup cohesion, and group members may consider group promotive and prohibitive voice as a means of contributing to the entire group.

Hypothesis 1: group faultlines are negatively related to group promotive ethical voice.

Hypothesis 2: group faultlines are negatively related to group prohibitive ethical voice.

The moderating role of group role ambiguity

Based on regulatory focus theory, promotive and prohibitive voice have different group targets: promotive voice is related to group growth and advancement, while prohibitive voice is related to group risk avoidance (Huang and Paterson, 2017). Although their conceptual distinctions imply that they have different outcomes, some studies have found that both forms of voice can be constructive and have the same effect on the development of the organization (Chamberlin et al. 2017). Consistently, empirical studies on the relationship between voice and job performance have been decidedly equivocal, reporting opposite effects for promotive and prohibitive voice on job performance in some cases (e.g., Liang et al. 2012) and the same effect (positive) in others (Chamberlin et al. 2017). There are conceptual reasons to believe that the influence of voice is contingent on certain factors. Our study extends this idea to propose that the effect of group ethical voice (promotive and prohibitive) on group performance (GOCB and group task performance) is contingent on group role ambiguity because group role ambiguity determines the meaning of group identity (Elstak et al. 2014).

Group role ambiguity is accompanied by a feeling of uncertainty (Cicero et al. 2010), which regulates individuals’ attention to group development and group risk avoidance. In groups with a high level of role ambiguity, group members are less likely to define themselves as a part of the group because it is difficult for the group to satisfy their basic need for uncertainty reduction (Carlson and Ross, 2022; Elstak et al. 2014). From this perspective of ethical voice, uncertainty increases the difficulty of employees’ ethical information-elaboration work (Ahmadi et al. 2017). In this situation, employees may take more time to consider the risk of in-role or extra-role behaviors and rational processing of information about ethical voice before taking action. Thus, group role ambiguity is likely to suppress employees’ level of attention to group ethical voice.

Regarding the interaction between group role ambiguity and group promotive ethical voice, we propose that group role ambiguity and group promotive ethical voice can be seen as prototypical of collective uncertainty and collective identity enhancement, respectively. During times of uncertainty, the need for uncertainty reduction takes precedence over the need for identity enhancement (Elstak et al. 2014). During such time, employees must pay more attention to how to survive in the organization regardless of the valence of the group. As Choi and Hogg (2020) emphasize, individuals must know who they are before they think about how good they are. Consistent with this, Hogg (2021) indicate that uncertainty is the most important risk or issue that individuals draw attention to because it threatens one’s self-concept, which defines what individuals need to do. Therefore, group role ambiguity, which represents a high level of uncertainty, inhibits employees’ attention to group promotive ethical voice. As a result, the positive effect of group promotive ethical voice on GOCB and group task performance is hampered.

In addition, both group role ambiguity and group prohibitive ethical voice focus on the negative aspects of the group (e.g., potential violations and high-level risk). This kind of consistence may increase the negative feelings that individuals experience from environmental uncertainty (Knippenberg et al. 2016). Negative feelings, along with group role ambiguity, inhibit individuals’ psychological attachment to the group in such a way that group members feel as if they do not have a predictable future because certainty is a determinant of how individuals take actions and what they expect from the group (Cicero et al. 2010). In this regard, group role ambiguity undermines individuals’ sense of identity, sense of belonging to the group and their sense of contributing to the group. Social identity theory suggests that uncertainty makes it difficult for individuals to assimilate themselves into a prototype that represents the group, thereby failing to validate their own self-concept (Hogg, 2021). Cesario et al. (2004) also indicate that when employees experience negative perceptions of ambiguous knowledge, the fit between environmental uncertainty and individuals’ prevention-oriented behaviors increases the strength of these negative feelings. Therefore, a high level of group role ambiguity intensifies the negative effect of group prohibitive ethical voice. As a result, employees are less likely to engage in group task performance and GOCB.

In contrast, in groups with lower levels of role ambiguity, uncertainty is not psychologically significant for employees, and attention may thus be redirected to group ethical voice. Employees do not spend their time on uncertainty reduction and may easily deal with ethical voice elaboration. According to social identity theory, a collective identity of certainty sustains the group identification of individuals, further leading to group-oriented behaviors (Choi and Hogg, 2020).

Hypothesis 3a: group role ambiguity moderates the relationship between group promotive ethical voice and GOCB such that the positive relationship between them is weakened when employees perceive a high level of group role ambiguity.

Hypothesis 3b: group role ambiguity moderates the relationship between group promotive ethical voice and group task performance such that the positive relationship between them is weakened when employees perceive high level of group role ambiguity.

Hypothesis 4a: group role ambiguity moderates the relationship between group prohibitive ethical voice and GOCB such that the positive relationship between them is weakened when employees perceive high level of group role ambiguity.

Hypothesis 4b: group role ambiguity moderates the relationship between group prohibitive ethical voice and group task performance such that the positive relationship between them is weakened when employees perceive high level of group role ambiguity.

Method

Participants

We conducted data collection from three Chinese organizations. The theoretical model assessed a set of online questionnaires that had been individually distributed with the support of a human resource manager. Along with our chosen variables, we clarified our responsibility based on the rule of confidentiality obligations (Qi et al. 2022a).

To reduce common method bias, we measured independent, mediating and moderating variables separately at previously recommended intervals (Chen and Treviño, 2022) and collected data on independent and dependent variables from different participants. We invited 779 employees at Time 1 to report the perceived age and gender subgroups, as well as their own demographic information. At time 2 (2 weeks later), all participants completed the questionnaire on group promotive and prohibitive ethical voice. We administered the Time 3 survey two weeks after time point 2 and asked participants to report their perception of group role ambiguity. 77 group leaders who directly manage the respondents were also invited to evaluate their followers’ GOCB and group task performance. To match the responses of employees with those of their leaders, we invited both to record the last four digital phone numbers of target employees (Qi et al. 2022a).

The final sample includes 632 group members (81% response rate) and 62 leaders (81% response rate) from 62 groups. On average, each group includes 10.19 members, ranging from 7 to 19. Participants in the final sample average 36.43 years old. 23.1% were less than 30 years old, 50.8% were 30–39 years old, 21.7% were 40–49 years old, 4.4% were more than 49 years old. 44.9% of participants were female.

Measures

The back-translation procedure was adopted to translate the original English items into Chinese (Qi et al. 2023). The following measures included in the questionnaires were recorded using six-point response scales.

Group promotive and prohibitive ethical voice

We applied Chen and Treviño (2022) designed 6 items to evaluate the degree to which participants perceived promotive (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.81) and prohibitive (3 items; Cronbach’s α = 0.85) ethical voice. The sample items for promotive and prohibitive were “How much did group members emphasize an opportunity for us to care for others?” and “How much did group members emphasize that we should stop doing something wrong or harmful?” respectively. The Rwg and ICC for promotive and prohibitive were acceptable (group promotive ethical voice: Rwg= 0.73; ICC(1) = 0.19; ICC(2) = 0.71; prohibitive ethical voice: Rwg= 0.71; ICC(1) = 0.22; ICC(2) = 0.75). Therefore, the group-level scale was calculated by averaging individuals’ responses.

Activated group faultlines

As discussed in the section on group faultlines, we calculated group faultlines as pertaining to two attributes: age and gender. Next, we followed Antino et al.’s (2019) steps to construct activated group faultlines. First, Shaw’s (2004) FLS algorithms were adopted to obtain the faultline strength scores for age and gender. Second, a four-item instrument from Jehn and Bezrukova’s (2010) study was adopted to reveal employees’ perceptions of the age and gender subgroups. Third, the scores obtained from the calculation of the FLS algorithms and survey of perceived subgroups were further multiplied. Finally, the multiplied score was averaged to represent the activated identity faultlines.

Group role ambiguity

Participants responded to four items borrowed from Cicero et al.’s (2010) designed instrument (e.g., I know in almost every moment what to do in the group). Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.82. The Rwg of the construct was 0.84. The ICC(1) and ICC(2) were 0.11 and 0.54, respectively. Therefore, the group-level scale was calculated by averaging individual responses.

Group-level organizational citizenship behaviors

GOCB was evaluated by five items adopted from Euwema et al. (2007) study (e.g. “this person in my group is willing to put in extra time on the job”). Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.85. The Rwg of the construct was 0.83. The ICC(1) and ICC(2) were 0.25 and 0.78 respectively. Therefore, the group-level scale was calculated by averaging individuals’ responses.

Group task performance

Group task performance was evaluated by three items adopted from Lam et al.’s (2002) study (e.g. “This group member is very competent”). Cronbach’s α of this scale was 0.82. The Rwg of the construct was 0.90. The ICC(1) and ICC(2) were 0.12 and 0.57 respectively. Therefore, the group-level scale was calculated by averaging individuals’ responses.

Control variables

We controlled group size because group size plays an important role in the interaction and performance of group members (Chen et al. 2019). In addition, our study also adopted age diversity and gender diversity as control variables because these variables not only reflect the most salient and easily activated characteristics of group faultlines (Leicht-Deobald et al. 2021) but are also determinants of employees’ moral perception and actions (Yao et al. 2021; Pearsall et al. 2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics and the inter-correlation between variables are displayed in Tables 1. The results of confirmatory factor analysis (Table 2) suggest that the five-factor model (x2/df = 1.94; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.04) was more appropriate than other alternative models. In addition, ANOVA was conducted to test between-organization variance for all variables. The results shown that group faultlines (F2,59 = 1.92, p > 0.05), group promotive ethical voice (F2,59 = 0.41, p > 0.05), group prohibitive ethical voice (F2,59 = 1.88, p > 0.05), group role ambiguity (F2,59 = 1.18, p > 0.05), GOCB (F2,59 = 1.08, p > 0.05), group task performance (F2,59 = 0.17, p > 0.05). Therefore, we did not control for organization in all hypotheses.

In terms of the impact of group faultlines on group promotive and prohibitive ethical voice, Table 3 shows that group faultlines have a negative effect on both the promotive type (β = −0.59; p < 0.01; ΔR2 = 0.13, Δf = 8.64, p < 0.01) and prohibitive type (β = −0.55; p < 0.05; ΔR2 = 0.09, Δf = 6.18, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. Hypothesis 3 predicts that group role ambiguity has a negative moderating influence on the relationship between group promotive ethical voice and GOCB/group task performance. Our results substantiate this hypothesis (Table 4), revealing that the influence of group promotive ethical voice varies by the level of group role ambiguity (GOCB: β = −0.47; p < 0.05; group task performance: β = −0.37; p < 0.01). To analyze the interaction effect in more detail, this study plotted the interaction displayed in Figs. 2 and 3. The results show that the simple of slope is positive and significant (GOCB: β = 0.34; p < 0.01; group task performance: β = 0.23; p < 0.01) at a low level of group role ambiguity, while it is nonsignificant (GOCB: β = 0.02; p > 0.05; group task performance: β = −0.02; p > 0.05) at a high level of group role ambiguity, indicating that employees that use promotive ethical voice in a group with high role ambiguity are less likely to engage in GOCB and task performance. In addition, Hypotheses 4 predicts that group role ambiguity has a negative moderating influence on the relationship between group prohibitive ethical voice and GOCB/group task performance. Table 5 shows that this hypothesis was supported (GOCB: β = −0.73; p < 0.05; group task performance: β = −0.47; p < 0.05). According to the plotted interaction effect in Fig. 4, group prohibitive ethical voice is related to group task performance only when the level of group role ambiguity is low (β = 0.24; p < 0.01) rather than high (β = −0.08; p > 0.05). Therefore, those that use prohibitive ethical voice in a group with high role ambiguity are less likely to engage in group task performance. However, group prohibitive ethical voice is non-significantly related to GOCB regardless of whether the level of group role ambiguity is high or low (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Based on an integration between regulatory focus theory and social identity theory, this study develops an overarching theoretical model to advance our understanding of the antecedents and contingency factors of two forms of group ethical voice. Consistent with our hypotheses, the findings reveal that group faultlines have a negative effect on group promotive and prohibitive ethical voice. In a group with a high level of role ambiguity, the positive effect of promotive voice on GOCB/group task performance and the positive influence of prohibitive voice on group task performance are inhibited.

Theoretical implications

Our study advances our knowledge of the predictors and boundary conditions of group ethical voice on the basis of regulatory focus and social identity theory. First, previous studies on the relationship between regulatory focus and social identity theory have focused mainly on group identification perspectives and individuals’ “upward voice” (voice that helps the group or a leader) (Burhan et al. 2023). None of them have addressed subgroup categorization and voice that targets fellow group members. Compared with individual upward voice, group ethical voice has a better reflection of group ethical environment and interaction between group members in the ethical ground. Group faultlines, representing subgroup categorization, have greater predictive power for group ethical voice than most predictors of individual upward voice, because they reflect the information interaction between group members (Qi et al. 2022a). The findings on the relationship between group faultlines and group ethical voice support the findings of the faultline literature that group faultlines are a “harmful” group structure in inhibiting group performance (Wu et al. 2021). The stronger group faultlines are, the stronger the psychological boundaries are between subgroup members and the less likely members are to speak out for ethical promotion or prevention purposes. This is because out-subgroup ethical voice is inhibited by out-subgroup hostility when faultlines are strong. To date, most faultline studies have examined the effects of group faultlines on group performance (e.g., Bezrukova et al. 2009; Qi et al. 2022b; Wu et al. 2021), but they have failed to further explore whether group faultlines may lead to barriers to group ethical voice. Without such an understanding, it may be impossible to explain why individuals’ ethical-related behaviors is limited in a smaller unit (e.g. subgroup) rather than a larger unit (e.g. group) and why individuals’ ethical-related behaviors cannot be extended from lower level unit to a higher level unit. Our study fills these gaps, demonstrating that collective promotion focus and prevention focus are related to in-group rather than out-group members. Overall, our study advances the theory of group ethical voice by examining intra-group structure and voice and thereby going beyond the traditional approach of examining the relationship between superordinate group identification and reactions to superordinate voice. Our study demonstrates that group ethical voice is not restricted to the unified or shared perception of the entire group; it is also influenced by self-categorized subgroup norms (Faddegon et al. 2008).

Although group promotive and prohibitive ethical voices have clear conceptual distinctions, our study found that both forms of voice can be driven by the same set of antecedents. This supports Morrison’s (2014) argument that factors that promote or hinder individuals from speaking out about supportive ideas can be the same as those that promote or hamper individuals from voicing issues that need to be solved.

Second, our study is a response to calls for moderators of ethical voice (Chen and Treviño, 2022) and regulatory focus perspectives (Liu et al. 2023) by exploring the role of group role ambiguity. Although previous studies have demonstrated the benefits of group ethical voice for group performance (Kim et al. 2023; Kim and Vandenberghe, 2020), not all groups with a strong group ethical voice may reach the same level of positive group performance. That is, the extent to which group ethical voice responds to group performance may be influenced by how much members care about this voice. Building on the proposition of social identity theory that uncertainty reduction drives individuals’ focus on collective activities (Choi and Hogg, 2020), we support this view to demonstrate that these collective activities can include group ethical voice and that group role ambiguity, a type of uncertainty, influences employees’ regulatory focus on the ethical voice. In this regard, the lower the level of group role ambiguity, the more likely members are to focus on group ethical voice. These findings are in line with the argument of Hogg et al. (2007) that individuals pay more attention to unambiguous group prototypes than to vague group prototype. This is because uncertainty reduction is the most basic and important individual need (Elstak et al. 2014). Once an individual has resolved uncertainty, they may redirect their attention to fulfilling other needs, such as the need for group ethical development.

However, our results contradict those of certain studies in the field of uncertainty and regulatory focus. Those studies assert the role of uncertainty in enhancing the benefits of regulatory focus to some extent. For example, Jiang et al. (2020) argue that environmental dynamism provides more changes in development and thus enhances the positive effect of CEO promotion focus on the magnitude of strategic change. Bruch et al. (2007) indicate that leaders who use a prevention-oriented voice are endorsed in situations of high uncertainty. There are some reasons for the difference in findings between our study and the above literature. First, we have different levels of concern and differently involved participants. Previous studies consider macro-organizational uncertainty as leaders’ situational regulatory focus, which plays an important role in influencing the leadership process (Jiang et al. 2020). However, these studies do not extend the micro-team level to explore whether group uncertainty regulates members’ regulatory ethical focus. This inattention is a limitation not only because leaders’ regulatory focus may be different from that of group members’ (Kark and Dijk, 2007) but also because lower-level collective identity (e.g., group identity) is closer to employees’ daily work and thus exerts a stronger effect on employees’ behaviors than higher-level collective identity (e.g., organization identity) does (Qi et al. 2023). In this study, we apply social identity theory to explain how group uncertainty works in the process of applying group ethical voice. Second, our research focuses on aggregated group members’ perception of uncertainty rather than relying on objective company sales data, as in previous studies. Compared with objectively measured uncertainty based on industry data, individuals’ perceived uncertainty exerts a stronger influence on their behaviors because of the perception-action match principle (Qi et al. 2023).

By exploring the interaction between group role ambiguity and group prohibitive ethical voice, our findings show that prohibitive ethical voice has no significant relationship with GOCB across high and low levels of group role ambiguity. This contradicts previous studies’ conclusion positing either the positive or negative influence of prohibitive regulatory focus on GOCB (Wallace et al. 2009; Chamberlin et al. 2017). A possible reason for this is that prohibitive voice and GOCB focus on distinct phenomena. GOCB is driven by a positive tone or voice that contributes to group morale. In contrast, prohibitive voice is related to conservative behaviors that are in-role and safety-oriented (Chamberlin et al. 2017).

Practical implications

Along with theoretical relevance, our study also provides practical implications. Group promotive and prohibitive ethics have strong effects on group behaviors. Organizations need to pay more attention to how to motivate employees to engage in group ethical voice and how to guide ethical speakers to engage in positive group performance. Our study provides two strategies with which to pursue this goal. First, group leaders need to monitor and control group composition based on the attributes of members (e.g., age and gender). Given the costs of group friction and the undermining of group ethical behaviors that can result from strong group faultlines, leaders may adjust group configuration by exchanging members between groups to reduce the strength of group faultlines (Yao et al. 2021). In doing this, subgroup members may feel the boundaries between subgroups is not fixed. As a result, the rules of in-subgroup favoritism and out-subgroup hostility can be changed along with new members joining and old members leaving. However, it is not always feasible to create a group whose members are of the same age and gender. Alternatively, group leaders can highlight relational values and mutual understanding between subgroups through weekly informal collective chatting based on the inter-(sub)group relational model of social identity theory (Rast et al. 2018; Burhan et al. 2023). Rast et al. (2020) indicated that highlighting positive relationships between different categories may reduce conflicts and enhance cooperation between them. In addition, based on the common in-group model of social identity theory (Qi et al. 2022b), leaders can shift group members’ attention from subgroup identity to group identity by highlighting the values and benefits of shared group identity for all group members. Bezrukova et al. (2009) asserted that group identification may consolidate groups and facilitate understanding between members, thereby enhancing group performance.

Second, group ethical voice is not always efficient, especially in cases of role ambiguity. Therefore, organizational leaders need to remain sensitive to group role settings (Davies et al. 2022). There are several strategies to avoid group role ambiguity in the workplace context. First, as job descriptions clarify individuals’ work content in each department (Vervecken and Hannover, 2015), human resource departments should formulate comprehensive and clear job descriptions to ensure that every group member knows what their role means and what they need to do in that specific role. Second, group leaders should be clearly aware of the nature of each member’s working role and ready to clarify or reiterate the role requirements when members get lost in the group. As role ambiguity is often happened in the job role change (Fuller and Hester, 2010), group members need to be informed in a timely manner if and when their roles change.

Limitations and future studies

First, the data on group faultlines and group ethical voice are collected from the same data source, which may lead to potential common method variance. However, we collected data on these variables at different time points to control for common method variance. Even so, we still recommend that future studies use multiple sources and multiple methods to confirm our results. Second, our sample comprises Chinese employees and leaders. It is unclear whether our findings can be generalized to other cultural workplaces. Under the influence of Chinese culture, the Chinese workplace is highly sensitive to uncertainty (Hofstede et al. 1990). This may explain why the moderating effect of group role ambiguity is significant. We suggest that future studies replicate our theoretical model by using Western samples in low uncertainty avoidance cultures. Third, our study develops a theoretical model based on social identity theory and only selects a single moderator and a single antecedent of group ethical voice. There may be other social variables that can be linked with group ethical voice literature. For example, leader group prototypicality may embody group identity values to employees and regulate employees’ focus on group norms and ethics (Kark and Dijk, 2007). Future studies can consider other variables (e.g., leaders’ group prototypicality) regarding social identity theory to further extend our theoretical model.

Conclusion

Our study expands the literature on group ethical voice by considering the role of group faultlines as a new antecedent of group ethical voice and revealing the moderating role of group role ambiguity in the relationship between group ethical voice and group performance. By exploring the roles of group faultlines and group role ambiguity, we suggest that to avoid barriers to group ethical voice, group leaders should regulate group structure and highlight group values to reduce the harm caused by the alignment of members’ attributes and clarify working role descriptions. We hope that our study will spur further exploration of the antecedents and moderators of group ethical voice and enhance understanding of the emergence and processes of group ethical voice.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality of the respondents’ information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmadi S, Khanagha S, Berchicci L, Jansen JJP (2017) Are managers motivated to explore in the face of a new technological change? the role of regulatory focus, fit, and complexity of decision-making. J Manag Stud 54(2):219–237

Antino M, Rico R, Thatcher SM (2019) Structuring reality through the faultlines lens: The effects of structure, fairness, and status conflict on the activated faultlines–performance relationship. Acad Manag J 62(5):1444–1470

Bezrukova K, Jehn KA, Zanutto EL, Thatcher SMB (2009) Do workgroup faultlines help or hurt? A moderated model of faultlines, team identification, and group performance. Organ Sci 20(1):35–50

Bruch H, Shamir B, Eilam-Shamir G (2007) Managing meanings in times of crisis and recovery: CEO prevention-oriented leadership. In R Hooijberg, JG Hunt, J Antonakis, K Boal, & N Lane (Eds.), Being there even when you are not: Leading through strategy, structures, and systems: 131-158. Oxford, UK: JAI Press

Burhan Q-A, Khan MA, Malik, MF (2023) Ethical leadership: a dual path model for fostering ethical voice through relational identification, psychological safety, organizational identification and psychological ownership. RAUSP Management Journal

Carlson JR, Ross Jr WT (2022) When polychronicity affects salesperson performance: the effects of improvisation, role ambiguity, and sales job complexity. Ind Mark Manag 107:323–336

Carton AM, Cummings JN (2012) A theory of subgroups in work teams. Acad Manag Rev 37(3):441–470

Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET (2004) Regulatory fit and persuasion. Transfer from “feeling right”. J Personal Soc Psychol 86:388–404

Chamberlin M, Newton DW, Lepine JA (2017) A meta‐analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: Identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Pers Psychol 70(1):11–71

Chen A, Treviño LK (2022) Promotive and prohibitive ethical voice: Coworker emotions and support for the voice. J Appl Psychol 107(11):1973–1994

Chen A, Treviño LK (2023) The consequences of ethical voice inside the organization: An integrative review. J Appl Psychol 108(8):1316–1335

Chen H, Liang Q, Zhang Y (2019) Facilitating or inhibiting? Chin Manag Stud 13:802–819

Chen M, Wang F (2021) Effects of top management team faultlines in the service transition of manufacturing firms. Ind Mark Manag 98:115–124

Choi EU, Hogg MA (2020) Self-uncertainty and group identification: A meta-analysis. Group Process Intergroup Relat 23(4):483–501

Cicero L, Pierro A, Knippenberg D (2010) Leadership and uncertainty: how role ambiguity affects the relationship between leader group prototypicality and leadership effectiveness. Br J Manag 21(2):411–421

Davies B, Leicht C, & Abrams D (2022) Donald trump and the rationalization of transgressive behavior: the role of group prototypicality and identity advancement. J Appl Social Psychol(7), 52

Elstak MN, Bhatt M, Riel CBMV, Pratt MG, Berens GAJM (2014) Organizational identification during a merger: the role of self-enhancement and uncertainty reduction motives during a major organizational change. J Manag Stud 52(1):32–62

Euwema MC, Wendt H, Emmerik HV (2007) Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. J Organ Behav 28(8):1035–1057

Faddegon K, Scheepers D, Ellemers N (2008) If we have the will, there will be a way: regulatory focus as a group identity. Eur J Soc Psychol 38(5):880–895

Fuller JB, Hester MK (2010) Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J Organ Behav 27(8):1089–1120

Hambrick DC, Finkelstein S, Mooney AC (2005) Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Acad Manag Rev 30:472–491

Hofstede G, Neuijen B, Ohayv DD, Sanders G (1990) Measuring organizational cultures: a qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Adm ence Q 35(2):286–316

Hogg M (2021) Self-uncertainty and group identification: consequences for social identity, group behavior, intergroup relations, and society. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 64:263–316

Hogg MA, Sherman DK, Dierselhuis J, Maitner AT, Moffitt G (2007) Uncertainty, entitativity, and group identification. J Exp Soc Psychol 43(1):135–142

Huang L, Paterson TA (2017) Group ethical voice influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. J Manag 43(4):1157–1184

Jehn KA, Bezrukova K (2010) The faultline activation process and the effects of activated faultlines on coalition formation, conflict, and group outcomes. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 112(1):24–42

Jiang W, Wang L, Chu Z, Zheng C (2020) How does ceo regulatory focus matter? the impacts of ceo promotion and prevention focus on firm strategic change. Group Organ Manag 45(3):386–416

Johnson, H, Wu, W, Zhang, Y, & Lyu, Y (2023) Ideas endorsed, credit claimed: Managerial credit claiming weakens the benefits of voice endorsement on future voice behavior through respect and work group identification. Human Relations

Kark R, Dijk DV (2007) Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: the role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Acad Manag Rev 32(2):500–528

Kim D, Vandenberghe C (2020) Ethical leadership and team ethical voice and citizenship behavior in the military: the roles of team moral efficacy and ethical climate. Group Organ Manag 45(4):514–555

Kim, D, Choi, D, & Son, SY (2023) Does Ethical Voice Matter? Examining How Peer Team Leader Ethical Voice and Role Modeling Relate to Ethical Leadership. J Business Ethics

Knippenberg DV, Wisse B, Pieterse AN (2016) Motivation in words: promotion- and prevention-oriented leader communication in times of crisis. J Manag 44(7):2859–2887

Lam SSK, Chen X, Schaubroeck J (2002) Participative decision making and employee performance in different cultures: The moderating effects of allocentrism/idiocentrism and efficacy. Acad Manag J 45:905–914

Lau DC, Murnighan JK (1998) Demographic diversity and faultlines: The compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):325–340

Leicht-Deobald U, Huettermann H, Bruch H, Lawrence BS (2021) Organizational demographic faultlines: their impact on collective organizational identification, firm performance, and firm innovation. J Manag Stud 58(8):2240–2274

Li, M, & Jones, CD (2018) The effects of tmt faultlines and ceo-tmt power disparity on competitive behavior and firm performance. Group Organization Management, 1–41

Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh J-L (2012) Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Acad Manag J 55(1):71–92

Liu, Z, Ouyang, X, & Pan, X (2023) Experiencing tensions, regulatory focus and employee creativity: the moderating role of hierarchical level. Chinese management studies

Ma H, Xiao B, Guo H, Tang S, Singh D (2022) Modeling entrepreneurial team faultlines: Collectivism, knowledge hiding, and team stability. J Bus Res 141:726–736

Morrison EW (2014) Employee voice and silence. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 1:173–197

Ndofor HA, Sirmon DG, He X (2015) Utilizing the firm’s resources: how tmt heterogeneity and resulting faultlines affect tmt tasks. Strat Manag J 36(11):1656–1674

Newheiser AK, Barreto M, Ellemers N, Derks B, Scheepers D (2015) Regulatory focus moderates the social performance of individuals who conceal a stigmatized identity. Br J Soc Psychol 54(4):787–797

Ogunfowora B, Gok K, Babalola MT, Garcia PRJM, Ren S (2022) Stronger together: understanding when and why group ethical voice inhibits group abusive supervision. J Organ Behav 43(3):386–409

Pearsall MJ, Ellis APJ, Evans JM (2008) Unlocking the effects of gender faultlines on team creativity: Is activation the key? J Appl Psychol 93(1):225–234

Qi M, Armstrong SJ, Yang Z, Li X (2022a) Cognitive diversity and team creativity: effects of demographic faultlines, subgroup imbalance and information elaboration. J Bus Res 139:819–830

Qi M, Liu Z, Kong Y, Yang Z (2022b) The influence of identity faultlines on employees’ team commitment: the moderating role of inclusive leadership and team identification. J Bus Psychol 38(4):1299–1311

Qi M, Shu Z, Song M (2023) Leader-member subgroup similarity and team identification: effects of faultlines, social identity leadership and leader-member exchange. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 32(2):272–284

Rast DE, Hogg MA, van Knippenberg D (2018) Intergroup Leadership Across Distinct Subgroups and Identities. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 44(7):1090–1103

Rast DE, van Knippenberg D, Hogg MA (2020) Intergroup relational identity: Development and validation of a scale and construct. Group Process Intergroup Relat 23(7):943–966

Rees HR, Sherman JW, Klauer KC, Todd AR (2022) On the use of gender categories and emotion categories in threat‐based person impressions. Eur J Soc Psychol 52(4):597–610

Satterstrom P, Kerrissey M, DiBenigno J (2021) The Voice Cultivation Process: How Team Members Can Help Upward Voice Live on to Implementation. Adm Sci Q 66(2):380–425

Shaw JB (2004) The development and analysis of a measure of group faultlines. Organ Res Methods 7:66–100

Shemla M, Wegge J (2019) Managing diverse teams by enhancing team identification: The mediating role of perceived diversity. Hum Relat 72(4):755–777

Ulrich LD, Hendrik H, Heike B, Barbara SL (2021) Organizational demographic faultlines: their impact on collective organizational identification, firm performance, and firm innovation. J Manag Stud 58(8):2240–2274

Vervecken D, Hannover B (2015) Yes i can! effects of gender fair job descriptions on children’s perceptions of job status, job difficulty, and vocational self-efficacy. Soc Psychol 46(2):76–92

Wallace JC, Johnson PD, Frazier ML (2009) An examination of the factorial, construct, and predictive validity and utility of the regulatory focus at work scale. J Organ Behav 30(6):805–831

Wu J, Triana M, del C, Richard OC, Yu L (2021) Gender Faultline Strength on Boards of Directors and Strategic Change: The Role of Environmental Conditions. Group Organ Manag 46(3):564–601

Xie XY, Wang WL, Qi ZJ (2015) The effects of tmt faultline configuration on a firm’s short-term performance and innovation activities. J Manage Organ 21(05):558–572

Yao J, Liu X, He W (2021) The curvilinear relationship between team informational faultlines and creativity: moderating role of team humble leadership. Manag Decis 59(2):2793–2808

Zheng Y, Epitropaki O, Graham L, Caveney N (2022) Ethical Leadership and Ethical Voice: The Mediating Mechanisms of Value Internalization and Integrity Identity. J Manag 48(4):973–1002

Zheng Y, Graham L, Farh JL, Huang X (2021) The impact of authoritarian leadership on ethical voice: a moderated mediation model of felt uncertainty and leader benevolence. J Bus Ethics 170:133–146

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Beijing Social Science Fund (22GLB017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LF collected and processed the data. QM drafted the manuscript. QM and LF contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, M., Liu, F. Promotive and prohibitive ethical voice in groups: the effect of faultlines and role ambiguity. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 325 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02799-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02799-8