Abstract

The increasingly serious problem of food waste in China has become an important bottleneck constraining sustainable development, posing a great challenge to food security, resource and the environment. Therefore, it is urgent to reduce food waste. However, the inconsistency between consumers’ intention to reduce food waste and their behavior weakens the effectiveness of anti-food waste efforts to some extent. Based on the extended MOA model, this study examines consumers’ intention-behavior gap in reducing food waste and explores the moderating effects of opportunity, ability and face consciousness on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior in the context of China. In addition, we further categorize consumers into high and low face consciousness groups to explore the differences in the moderating effects of opportunity and ability. The results show that there is indeed a gap between consumers’ food waste reduction intention and behavior. In terms of the moderating effects, the factors of external environment, emotional information, and ability have a significant positive moderating effect on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior, while rational information has no significant moderating effect. Notably, face consciousness plays a significant negative moderating effect. For the high face consciousness group, only emotional information has a significant positive moderating effect; while for the low face consciousness group, external environment, emotional information, and ability have a significant positive moderating effect. What’s more, rational information has a non-significant moderating effect on both the high and low face consciousness groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed an increasingly challenging situation for global food safety and security due to climate change, economic volatility and continuing geopolitical conflicts. Although the global food supply crisis is worsening and hunger levels are skyrocketing, the annual global food waste is staggering. According to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019 published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), globally, about 1.3 billion tons of food are wasted or depleted during production and consumption every year, which is as high as 1/3 of the total food output (Aschemann-Witzel et al. 2023). The total amount of food wasted annually is even more prominent in China as a globally populated country, which has become one of the major challenges constraining the sustainable transformation of agrifood systems (Chen et al. 2023). Food waste is the loss of food at the end of the food supply chain (retail and consumption links) caused by subjective factors of retailers and consumers (Parfitt et al. 2010). And catering food waste is an extremely important component of consumer-side food waste in China (Zhang et al. 2024). In 2018, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences jointly released the Report on Urban Catering Food Waste in China, showing that the per capita food waste in China’s catering sector is 93 grams per person per meal, with a waste rate of 11.7%. Extrapolating from survey data from 2013 to 2015, the food waste caused by China’s urban catering industry is about 17–18 million tons (in terms of cooked food) per year, equivalent to the total amount of food needed by 30–50 million people in a year (Wang et al. 2018). Food waste not only causes direct economic losses but also leads to ineffective depletion of agricultural natural resources, such as land and water invested in the whole life cycle of food, thus aggravating the pressure on the ecological environment (Nunkoo et al. 2021).

In the face of the economic losses and the negative externalities of resources and environment caused by food waste, curbing food waste has become increasingly urgent. In 2021, China passed the Anti-Food Waste Law of the People’s Republic of China and implemented the Implementation Program for Promoting Green Consumption in the following year to promote the work of combating food waste in depth. With the positive progress of the related work, the public’s awareness of food saving has been awakening, and more and more consumers have shown strong intention to save food. However, intention is not the only factor that determines behavior; consumer behavior is also influenced by other factors such as the objective external environment (Stancu et al. 2016) and individual ability (De Laurentiis et al. 2020), which may cause consumers to implement food waste behaviors that are contrary to their intentions. In other words, consumers may have the intention to reduce food waste but fail to do so (Visschers et al. 2016), a phenomenon that scholars refer to as the intention-behavior gap (Nguyen et al. 2019; Fraj-Andrés et al. 2023). Ajzen et al. (2018) find that the correlation between intention and behavior averages 0.45–0.62, that is, the two are not perfectly aligned. This gap implies that the existing array of anti-food waste efforts carried out may only enhance consumers’ intention to reduce food waste but not be effective in promoting their behavior to reduce food waste, rendering many of the efforts made by the relevant sectors to curb food waste largely ineffective. Therefore, it is vital to explore targeted intervention strategies to bridge this gap to enhance the effectiveness of anti-food waste efforts and reduce food waste.

Basing their analysis on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) or the Motivation-Opportunity-Ability (MOA) model and employing the focus group interview method or the rooted theory research method, most of the current research on food waste reduction explores the drivers of consumers’ food waste reduction behaviors and corresponding intervention strategies in households (Vittuari et al. 2023), cafeterias (Malefors et al. 2022), restaurants (Hassan et al. 2022), and tourist sites (Fazal-e-Hasan et al. 2023) from the economic, psychological, and anthropological perspectives. However, there is a relative lack of existing research on the effective conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior, which is the key to implementing anti-food waste efforts and effectively curbing food waste. Although some scholars have found inconsistency between food waste reduction intention and behavior (Fraj-Andrés et al. 2023), they are more based on theoretical analyses instead of empirical analyses. In the empirical study of the intention-behavior gap, the MOA model is considered the most systematic and mature theoretical model, with better stability and predictability of behavior (Jiang and Yan 2020). However, the MOA model has certain limitations as it does not take into consideration the cultural context of individuals. In real-life situations, Chinese people attach great importance to face, a concept that has become one of the most basic cultural concepts regulating Chinese people’s daily behaviors, and the influence of specific face scenarios on Chinese consumers’ intentions and behaviors is pervasive and far-reaching. Therefore, exploring the intention-behavior gap of consumers to reduce food waste cannot be separated from the traditional Chinese cultural context. Due to the influence of “high-context culture” in Chinese society, Chinese people’s consumption behavior has a characteristic of strong group embeddedness. Unlike European and American societies, Chinese people are more concerned about their own image and the resulting social effect, which is expressed as “face” (Juan Li and Su 2007). “Face” plays a crucial role in the Chinese cultural context (Mo 2021). For example, food waste behavior at the Chinese dinner table is closely related to face (Liao et al. 2018), where a sumptuous banquet with leftovers is regarded as a “way of hospitality” and the just number of dishes or a lack of wine or food is considered as “bad hospitality” which is regarded as a loss of face and a loss of honor, thus serious catering waste arises. In view of this, focusing on the catering food waste of Chinese residents, this paper draws on the basic theoretical framework of the MOA model and innovatively expands it by taking the unique Chinese concept of face as a moderating variable to examine the intention-behavior gap of consumers to reduce food waste. Specifically, we probe into the moderating effects of opportunity, ability, and face consciousness on the conversion of the intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior. In addition, we further investigate the differences in the moderating effects of opportunity and ability for consumers of high and low face consciousness groups and then propose targeted countermeasures accordingly.

Compared with the existing literature, the possible contributions of this paper are reflected in the following aspects: First, there is a lack of empirical research on the intention-behavior gap in reducing food waste, which is one of the key issues in addressing food waste. The research in this paper fills in the gaps in the existing research and constitutes a useful addition to the existing literature as it provides a reference for the relevant departments in policy making and food waste intervention. Second, this paper extends the concept of face with Chinese characteristics into the MOA theoretical framework to explore the influence of culture on consumer behavior, which improves the theory of consumer behavior. Third, to develop more precise intervention strategies, this paper categorizes consumers into two groups of high and low face consciousness to further explore the differences between different groups of consumers in terms of the mean values of the explanatory, moderating, and explained variables as well as the differences in the moderating roles of opportunity and ability.

Research design and methodology

Theoretical foundation and research hypothesis

The MOA model was firstly proposed by Maclnnis and other scholars in 1991, which consists of the three core elements of Motivation, Opportunity and Ability, i.e., intrinsic motivation (“whether want to do”), external opportunity (“whether allowed to do”) and personal ability (“whether can do”) are interrelated and work together to promote the emergence of specific behavior. Among them, motivation is the main driver of behavioral achievement, while opportunity and ability moderate the relationship between motivation and behavior (Maclnnis et al. 1991). So far, the MOA model has been widely used in many research fields such as tourism behavior (Supryadi et al. 2022), community participation behavior (Kunasekaran et al. 2022), and farmers’ straw resourcing behavior (Jiang and Yan 2020). In the field of food waste behavior, some scholars have constructed a framework for analyzing the influencing factors of consumers’ food waste behavior based on the MOA model, analyzed the mechanism of food waste behavior in depth, and proposed interventions accordingly (Vittuari et al. 2023; Soma et al. 2021). However, most of the above studies are based on the basic theoretical framework of MOA. To better fit the reality of food consumption in China, this paper innovatively adds the variable of face consciousness, which is characterized by Chinese characteristics, to expand the theoretical analytical model of MOA. Based on the expanded MOA model, we develop five research hypotheses, as described in detail in the following parts.

Motivation

Motivation is an internal driver of individual action and refers to the psychological process that stimulates, encourages, and directs behavior, which embodies an individual’s intention to take a certain action and has a direct impact on behavior (Maclnnis et al. 1991). In the case of food waste behavior, motivation refers to consumers’ intention to reduce food waste (Vittuari et al. 2023), and the stronger their intention is, the less likely they will be to put into practice wasteful behavior (Visschers et al. 2016). First, reducing economic loss is one of the strongest motivations to avoid or reduce food waste (Nabi et al. 2021). Thrifty consumers tend to view food waste as a monetary loss and thus tend to avoid food waste in order to minimize the loss (Amirudin and Gim 2019). Second, the environmental motivation is also an important factor that motivates consumers to reduce food waste. Given the fact that food waste brings negative effects such as environmental hazards and resource wastage (Melbye et al. 2017), consumers will feel “frustrated” (Graham-Rowe et al. 2014), “disgust” (Waitt and Phillips 2016), “guilty”, and “shame” (Pearson and Perera 2018) towards food waste behavior, which are important motivations for consumers to reduce food waste (Qi and Roe 2016). In addition, some consumers may be motivated by the desire to set a good image in front of others or to set a good example for their children, thus leading by example and eliminating waste (Fraj-Andrés et al. 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Motivation (intention) to reduce food waste positively influences actual behavior.

Opportunities

If the process of converting intention into actual behavior is influenced by external opportunities, the two may be paradoxical (Zhang et al. 2019). Maclnnis et al. (1991) points out that opportunities are objective external situations perceived by the actor as conducive to triggering a specific behavior, and are characterized by objectivity, subjectivity, and beneficence. In the case of food waste, opportunities mainly include elements related to the external environment of consumption, such as store accessibility (De Laurentiis et al. 2020) and effective reminders from food service staff (Lian et al. 2022), which can facilitate consumers to reduce food waste. The higher the store accessibility is, the higher consumers’ shopping frequency will be, i.e., to buy small quantities several times, which is helpful to avoid unnecessary food waste due to stockpiling (Soma et al. 2021; De Laurentiis et al. 2020). If food service staff give ordering suggestions in advance based on the number of consumers and the portion size of dishes, it will help consumers make reasonable decisions and avoid over-ordering, thus reducing food waste (Lian et al. 2022). Service staff’s proactive prompting of packing or providing packing bags at the end of the meal can help motivate consumers to actively pack their food and increase the consistency of consumers’ intention and behavior to reduce food waste (Cerrah and Yigitoglu 2022).

In addition, external information is also one of the important opportunity factors that significantly contributes to both intention and behavior (Dawson 2018). A large number of studies have confirmed that information can enhance consumers’ awareness of environmental issues and their behavior, which is conducive to promoting green consumption behavior (Chen and Lobo 2012). Notably, reducing food waste is an important component of green consumption (Verain et al. 2015). On their analysis of practicing informational intervention in food waste, Stöckli et al. (2018) find that information prompts prompt consumers to pack away leftover food, thereby effectively reducing food waste. In addition to having a direct positive effect on behavior, information also plays a positive moderating role in the process of converting intention into actual behavior (Li and Shao 2020). Wei et al. (2023) categorize information into rational information, which is mainly related to specific guidance information and policy regulations, and emotional information, which focuses on emotional information that elicits consumers’ emotional resonance. The effectiveness of the two in influencing consumer behavior also varies, with some scholars arguing that rational information incentives are superior to emotional information incentives because rational information is more concise and clearer in conveying key information than emotional information (Laskey Henry et al. 1995), while some scholars argue that emotional information incentives are more effective (Mattila 1999). Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper:

H2a: The external environment has a positive moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

H2b: The emotional information has a positive moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

H2c: The rational information has a positive moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

Ability

Even when consumers have the intention to reduce food waste and have favorable external opportunities, a lack of ability may still prevent consumers from practicing the behavior to reduce food waste (Zhang et al. 2019). Consumers’ food waste reduction behavior is related to food storage and handling capacity (Van Geffen et al. 2020), as well as their acquired knowledge about the hazards of food waste (Vittuari et al. 2023) and scientific food purchase plans (Liao 2022). The more adequate the above knowledge an individual possesses, the more effective he/she is in reducing food waste. However, existing research suggests that consumers are less aware of the environmental hazards of food waste, believing that food waste can be decomposed naturally and does not cause environmental pollution, which may result in wasteful behavior (Farr-Wharton et al. 2014). Therefore, when consumers have sufficient knowledge about food waste, they can more effectively convert their intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior. In addition, making a reasonable food purchase plan by combining the existing food inventory, number of diners, etc., and purchasing on demand to avoid repetition of existing food purchases can also help to reduce food waste (Stancu et al. 2016). Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Ability has a positive moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

Face consciousness

Since consciousness and behavior are rooted in specific cultural contexts, studying consciousness and behavior outside cultural contexts is potentially flawed (Liu et al. 2013). Therefore, the study of Chinese consumers’ food waste intention and behavior should focus on the unique elements of Chinese culture. The Chinese nation has experienced five thousand years of development and evolution, and has gradually formed a Confucian culture guided by Confucianism. Influenced by Confucianism, Chinese people tend to be group-oriented and value interpersonal relationships. In interpersonal interactions, they care more about others’ perceptions and are face-conscious, forming a unique concept of face. Under the influence of face consciousness, most Chinese people believe that individual behavior should conform to the corresponding social norms as much as possible. When individuals violate social norms and do not conform to social expectations, they will feel disgraced and accordingly develop a sense of shame or guilt. Scholars such as Redding and Michael (1983) and Kinnison (2017) have found that face consciousness is the key to understanding the psychology and behavior of the Chinese. In their in-depth interviews with 20 Chinese diners, Hoare et al. (2011) summarize that face, trust, and harmony are the most important factors that Chinese consumers value when dining in foreign restaurants, with face being particularly critical. According to Hu (1944), “face” should be divided into two dimensions: lien and mien, where lien is the respect for one’s moral reputation, a kind of social binding force to maintain moral standards, and an internalized self-restraining force; mien refers to the individual’s reputation gained from success or being boasted about. Chinese consumers’ food waste behavior is closely related to the boastfulness of mien in the face dimension, i.e., consumers may not order according to their needs at the dinner table for the sake of face and may overindulge in extravagance, which is seen as their status and bragging capital, thus leading to wastefulness (Tang and Wang 2021). In addition, under the role of face consciousness, some consumers believe that packing leftovers is a loss of face and resist the behavior of postprandial packing (Hamerman et al. 2018), resulting in unnecessary waste. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Face consciousness has a negative moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

Furthermore, individuals with different face consciousness are differentially influenced by external social norms and interpersonal relationships. Specifically, individuals with higher face consciousness are more likely to be influenced by interpersonal relationships relative to individuals with lower face consciousness (Huang et al. 2021). Consumers with higher face consciousness tend to be more eager to raise social prestige through ostentatious consumption in the social groups involved (Mi et al. 2018). Thus, compared to low face consciousness consumers, consumers with higher face consciousness may not necessarily put their intention to reduce food waste into practice even if they have favorable opportunities or have sufficient knowledge and ability to reduce food waste. Wang (2013) categorize consumers into high and low face consciousness groups and find that for consumers in different face consciousness groups, resource conservation awareness and the influence of situational variables on resource-saving behavior differ significantly. Notably, food waste reduction behavior is similar to resource-saving behavior. As a result, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: For consumers with different face consciousness, differences exist in the moderating effects of opportunity and ability on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

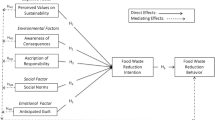

Based on the discussions in the previous section, the expanded Motivation-Opportunity-Ability framework depicted in Fig. 1 highlights the direct effect of food waste reduction intention on food waste reduction behavior as well as the moderating effects of opportunities, ability and face consciousness on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior.

Scale design

Drawing on the questionnaire design ideas of Dong et al. (2022), Vittuari et al. (2021), and Verain et al. (2015), this paper scientifically designs the content as well as the structure of the questionnaire. The content of the questionnaire includes the demographic characteristics of the respondents, such as gender, age, and education level, as well as seven latent variables of motivation (M), external environment (EE), emotional information (EI), rational information (RI), ability (A), face consciousness (FC), and food waste reduction behavior (FWRB), which are measured by a 7-point Likert scale. The corresponding questions and references for each variable are shown in Table 1. Notably, some of the questions are changed appropriately to better fit the real-life context in China.

Data sources

In this paper, following the principle of random sampling, four representative cities in Jiangsu Province, namely Wuxi City in southern Jiangsu, Yangzhou City in central Jiangsu, Huai’an City in northern Jiangsu, and Lianyungang City, are selected as the sampling areas. Field surveys were organized and conducted in July-August 2023. The three regions of Jiangsu Province, namely southern Jiangsu, central Jiangsu, and northern Jiangsu, represent different levels of economic development and are representative. The researchers choose respondents randomly in restaurants, factories, large shopping malls, neighborhoods, parks, etc., ensuring that the samples are distributed across different gender, ages, education levels, and annual incomes. The informed consent form will be read on the front page of the questionnaire before the respondent starts to fill in the survey, and only when the respondent agrees to take the survey will he/she be able to start answering the questionnaire. The survey is anonymous and will not reveal the privacy of any respondent. To ensure the quality of the questionnaire, each respondent who completed the survey was given a small gift worth 5 RMB as compensation for the time delay in taking the survey. After excluding ineligible, incomplete and not carefully completed questionnaires, a total of 680 valid questionnaires are collected. The distribution of the sample is shown in Table 2.

Research methodology

When both explanatory variables and moderating variables are continuous variables, hierarchical regression analysis is done to test the moderating effect (Wen et al. 2005). Likert scale values are not continuous, but can be analyzed using hierarchical regression as they were (Johnson and Creech, 1983). Therefore, this paper establishes the following test model:

where FWRB is the explained variable; M is the explanatory variable; EE, EI, RI, A, and FC are the moderating variables; α0 is the constant term; αi is the regression coefficient; the intersection terms represent the moderating effects of the moderating variables on the relationship between M and FWRB, for example, M×EE represents the moderating effect of the external environment on the path relationship between food waste reduction intention and behavior; µ0 represents the error term.

Results and discussions

Model testing

To verify the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, this paper utilizes SPSS27.0 and Amos24.0 software to conduct the reliability and validity test of the questionnaire.

Reliability test

Generally, a Cronbach’s α coefficient value of 0.7 or above indicates a good internal consistency of the questionnaire. The results of the test shown in Table 3 suggest that the Cronbach’s α values for each variable exceed the critical value of 0.7, indicating that the questionnaire used in this study has good reliability.

Validity test

The convergent validity of the scale is tested by calculating the combined reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 4, the KMO values for each variable are greater than 0.7, which is higher than the standardized value of 0.5 proposed by Kaiser (1974), and the significance probabilities of the Bartlett’s test of sphericity are less than 0.05, which suggests that the empirical data are suitable for factor analysis. Factor analysis shows that the standardized factor loadings for each question item are greater than the standard value of 0.6, and then the CR value and the AVE value are calculated from the factor loadings, respectively. The results show that the CR values for each variable are greater than 0.8 and the AVE values are greater than 0.6, indicating that the scale had good convergent validity.

The results of the discriminant validity test are shown in Table 5. The AVE square root of each variable is greater than the correlation coefficient between the variables, which indicates that the internal correlation between the variables is greater than the external correlation and that there exists difference between the variables, suggesting that the scale has a good discriminant validity.

Multicollinearity test

Excessive correlation of variables can cause problems such as inaccurate regression coefficients and variance inflation, which may affect the explanatory power and predictive ability of the model. The multicollinearity test is used to detect the degree of correlation between variables. This paper carries out the multicollinearity test by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF).

As shown in Table 6, the VIF values of the explanatory variable and the moderating variables are below 2, so there is no serious problem of multicollinearity and the empirical data can be analyzed by regression.

Analysis on the consistency of intention and behavior to reduce food waste

To verify that there is indeed a gap between consumers’ intention to reduce food waste and their behavior, a paired-sample t-test is conducted in the paper. The corresponding results are presented in Table 7. It shows that the significance probability of the t-test is less than 0.05, which means that there is a significant difference between the two, and the mean value of the difference is 0.262. The results in Table 7 indicate that consumers’ intention to reduce food waste has not been completely converted into actual behavior, and the inconsistency between intention and behavior does exist.

Analysis on the moderating effects

Using SPSS27.0 software, this paper employs hierarchical regression analysis to test the moderating effects of external environment, emotional information, rational information, ability, and face consciousness on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior. Notably, all variables are centered before analyzing the moderating effects. With the behavior to reduce food waste as the explained variable, control variables are added in the first step of the hierarchical regression (Model I), followed by the inclusion of the explanatory variable in the regression model (Model II) to analyze the main effects; the moderating variables are then included (Model III), and finally, the interaction terms between the explanatory variable and each of the moderating variables are added (Model IV) to analyze the moderating effects. With the inclusion of variables, R2 gradually increases and changes significantly, indicating that the predictive ability of each model gradually increases. Model II examines the effect of the intention to reduce food waste on actual behavior and find that the intention significantly and positively affects actual behavior, thereby verifying Hypothesis H1, a result that is consistent with some scholars’ studies (Coşkun and Yetkin Özbük 2020; Attiq et al. 2021). However, in real-life situations, consumers’ intention to reduce food waste does not necessarily convert into actual behavior. To further explore the moderators in the process of converting intention into behavior, interaction terms between the moderating variables and the intention to reduce food waste are introduced in Model IV.

The estimated coefficients of the control variables in Model I is shown in Table 8. Age significantly and positively affects consumers’ food waste reduction behavior, i.e., the older the consumers are, the more able they will be to reduce food waste. This may be related to the different consumption concepts of consumers of different ages and the different eras they have been through, as the older generation in China has experienced the 1960s and 1970s when there were a lack of goods and people valued food more. The significant negative effect of educational attainment on consumers’ food waste reduction behaviors may be due to the fact that consumers with higher educational attainment generally have higher incomes, and higher incomes result in more food waste.

The coefficient of the interaction term between external environment and intention to reduce food waste in Model IV is positive and significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that the external environment has a significant positive moderating effect on the conversion of intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior, thereby verifying Hypothesis H2a. That is, the higher the store accessibility is and the more proactive the food service staff is to remind consumers to order moderately or prompt to pack, the more motivated consumers will be to put their intention to reduce food waste into action. Therefore, the distance to the supermarket is a major obstacle for consumers to reduce food waste. If stores are highly accessible, consumers can avoid food waste due to stocking up by shopping in small quantities (De Laurentiis et al. 2020). When eating out, the decision maker in charge of ordering may not be able to accurately know the amount of food needed and taste preferences of the group, and suggestions from food service staff about portion sizes and flavors can help to avoid ordering incorrectly or over-ordering (Lian et al. 2022). In addition, food service staff prompting consumers to pack or offering to provide packing bags can effectively alleviate consumers’ embarrassment due to packing behavior (Hamerman et al. 2018), thus promoting consumers to put their intention to reduce food waste into practical action.

The moderating effect of external information in Model IV shows that the emotional information has a significant positive moderating effect, while the rational information plays no significant effect, thus verifying Hypothesis H2b but not so for Hypothesis H2c. As in Wei et al. (2023), emotional information significantly and positively influences consumers’ low-carbon consumption behavior, while rational information does not have a significant effect. Mattila (1999) also believes that emotional information can create empathy and recognition among consumers and has a better effect than rational information in promoting consumer behavior.

The coefficient of the interaction term between ability and intention in Model IV is positive and significant at the level of 0.01, indicating that ability plays a significant positive moderating role in the process of converting intention into behavior, i.e., the stronger the ability of a consumer is, the more likely that his/her intention to reduce food waste will be converted into actual behavior. Therefore, Hypothesis H3 is verified. The reason for this is obvious: if consumers have the intention to reduce food waste and have more knowledge about food management and storage, they will be more able to buy and store food wisely, thus reducing food waste.

The coefficient of the interaction term between face consciousness and intention to reduce food waste in Model IV is −0.041, which is significant at the 0.05 level, indicating that face consciousness plays a significant negative moderating role in the process of converting consumers’ intention to reduce food waste into their behavior, and thus Hypothesis H4 is verified. This finding suggests that face consciousness does influence consumers’ food waste intention and behavior. Chinese people tend to show off their “face” or “hospitality” by ostentatious consumption such as ordering too much food, which is very likely to result in food waste. In addition, under the influence of face consciousness, consumers tend to order too much food to gain respect and compliments from others. Face consciousness evolves into extravagance through ostentatious consumption, which renders far more dishes than actually needed, ultimately resulting in food waste behavior.

Analysis on the moderating effects for different face consciousness groups

First, the direct effect of face consciousness on the explained variable, the explanatory variable and the moderating variables is examined by the independent samples T test. The corresponding results are shown in Table 9. There are significant differences between the high face consciousness group and the low face consciousness group in terms of motivation, external environment, emotional information, rational information and ability to reduce food waste. That is, compared with the high face consciousness group, the low face consciousness group has a stronger intention to reduce food waste, is more susceptible to the influence of the external environment, is more interested in external information, and possesses more knowledge related to the hazards of food waste, food storage and disposal.

Second, the relationship between intention and behavior as well as the moderating effects of external environment, emotional information, rational information, and ability on the conversion of intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior are examined in different face consciousness groups. The specific results are presented in Tables 10 and 11.

The results show that consumers’ intention to reduce food waste has a significant positive effect on their behavior for both the high face consciousness group and the low face consciousness group, i.e., consumers’ intention contributes significantly to behavior regardless of their face consciousness. In addition, there are significant differences in the moderating effects of opportunity and ability for consumers in different face consciousness groups, thus verifying Hypothesis H5. For the high face consciousness group, only emotional information has a significant positive moderating effect on the conversion of consumers’ intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior. For the low face consciousness group, the external environment, emotional information, and ability have a significant positive moderating effect. However, rational information has no significant moderating effect on both high and low face consciousness groups.

Conclusions and main contributions

Taking the MOA model as the basic framework and reviewing related literature, this paper expands the MOA model by introducing the factor of face consciousness in the Chinese context and examines consumers’ intention-behavior gap in reducing food waste with the help of paired-sample t-test. More importantly, we explore the role of opportunity (external environment, emotional information, rational information), ability, and face consciousness in moderating the process of converting the intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior with the help of multivariate hierarchical regression. We further classify consumers into high and low face consciousness groups to investigate the differences in moderating effects of opportunity and ability on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior for consumers with different face consciousness. The empirical results show that there is indeed a significant gap between consumers’ intention to reduce food waste and their behavior in China’s food consumption context, and that intention significantly and positively influences actual behavior. Factors of external environment, emotional information, and ability positively moderate the conversion of intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior, while rational information plays no significant effect and face consciousness significantly negatively moderates the conversion. In addition, for the high face consciousness group, only emotional information has a significant positive moderating effect; while for the low face consciousness group, external environment, emotional information, and ability have significant positive moderating effects. Notably, the rational information has no significant moderating effect on both high and low face consciousness groups. Specifically, for individuals with high face consciousness, pushing emotional information that can arouse consumers’ emotional resonance can significantly promote the conversion of their intention to reduce food waste into actual behavior; while for individuals with low face consciousness, in addition to using emotional information, providing a favorable external environment and enhancing consumers’ awareness of food waste and improving their ability to store and handle food correctly can effectively promote the practice of food waste reduction.

The research in this paper has both theoretical and practical implications, in which the theoretical contributions are reflected in the following two aspects. Firstly, scholars generally equate intention with actual behavior or consider the two to be highly correlated when studying consumer behavior, and the gap between the two is little studied. Even though some scholars have paid attention to the gap between food waste reduction intention and behavior (Fraj-Andrés et al. 2023), they studied it from a theoretical level rather than an empirical level (Van Geffen et al. 2020). This paper empirically verifies the existence of the “intention-behavior” gap in reducing food waste using data collected from four representative cities in Jiangsu Province, thus substantially promoting the development of research on the “intention-behavior” gap. Secondly, most of the existing literature is based on the basic theoretical framework of MOA (Soma et al. 2021; Vittuari et al. 2023), and does not take into consideration the role of the real cultural context in which individuals live. This paper, however, expands the framework of MOA by incorporating face consciousness—a characteristic of Chinese culture—as an important moderating variable. By doing so, this paper not only refines the theoretical model of consumer behavior, but also expands the research orientation of existing literature focusing on face consciousness as main and mediating effects (Li and Cui 2021; Shi et al. 2017). The results show that face consciousness has a negative moderating effect on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into actual behavior, which suggests that Chinese consumers are likely to be influenced by the concept of face and incline to ostentatious consumption such as ordering too much food that shows their status yet results in food waste. This finding is to some extent consistent with the conclusion drawn by Le Monkhouse et al. (2012) and Chen et al. (2014), as well as with Hu’s (1944) view of the boastfulness of “mien” in the face dimension.

Apart from the aforementioned theoretical contributions, the findings of this paper also provide the following practical insights for bridging the intention-behavior gap of consumers in reducing food waste:

The above empirical analysis shows that consumers’ intention to reduce food waste positively affects their actual behavior. Therefore, the government can strengthen the publicity of food waste reduction through the combination of traditional media and new media, so that the concept of “practicing economy and eliminating waste” can be deeply rooted in people’s hearts and minds and consumers’ intention to reduce food waste can be strengthened, thus effectively promoting behavior to reduce food waste.

The food service industry should enhance training for service staff with the aim of providing possible external opportunities for consumers to reduce food waste. Catering establishments should require service staff to take the initiative to remind customers to order the right amount of food according to the number of diners, their personal tastes, and their needs, and to advise on the number of portions of food to be ordered. At the end of the meal, service staff should proactively provide environmentally friendly packing boxes or bags, thus cultivating the habit of consumers to pack the leftovers. Catering establishments can consider to set up a special civilized dining counselor who timely offers guidance to consumers to reduce food and beverage waste, especially when serving wedding banquets, birthday banquets, annual banquets, tourism and other group meals.

Provide instructions and training on food management, storage and other knowledge through popularized science lectures and thematic educational activities, so as to enhance consumers’ ability to correctly store and dispose of leftover food, thus reducing food waste due to inappropriate storage and other reasons.

As mentioned earlier, emotional information has a significant positive moderating effect on the conversion of food waste reduction intention into behavior, while rational information has no significant moderating effect. Therefore, the government, non-profit organizations or the catering industry should focus on the use of emotional information incentives in the information intervention in food waste. Specifically, the aforementioned institutions should design public service advertisements and push messages that emphasize the harm of food waste to the human living environment as well as the benefits of reducing food waste for individuals and society with the aim of arousing the emotional resonance of consumers, thus stimulating the positive emotions of consumers towards the reduction of food waste, such as feelings of pleasure, satisfaction and pride. In this way, consumers will be inclined to reduce food waste voluntarily.

The unique concept of face at the Chinese dinner table is an important factor that prevents consumers from reducing food waste. For the sake of face and in pursuit of “grandeur”, consumers may pursue ostentatious consumption at the dinner table and not order according to need, leading to wastefulness. Government departments should step up their efforts to guide the social atmosphere, direct ostentatious consumption towards pragmatism, and advocate a frugal, green and economic lifestyle in the whole society. In addition, the social atmosphere has a great influence on consumers’ “face”. When the group around an individual practises frugal consumption and forms group norms, consumers tend to make the same choices as others under the influence of group normative pressure (Gao and Wang 2021). Therefore, the relevant departments can intervene in individual behavior with the help of group norms. Specifically, it is recommended to use TV, Internet and other media to promote and guide the culture and social atmosphere of reducing food waste, by and by forming a “new food trend” of saving in the whole society, thus guiding the public to follow the example of thrift.

Relevant departments should identify the differences in consumers and provide precise intervention strategies. For consumers with high face consciousness, it is necessary to use more emotional information to motivate them, while for consumers with low face consciousness, it is also possible to cultivate their good habits of food saving by the reminder given by catering service staff and the cultivation of their ability to reduce food waste so as to promote the fundamental conversion of the intention to reduce food waste into the actual behavior.

Limitation and future directions

The study in this paper enriches and expands the existing results in the research field of food waste reduction behavior, but there are some shortcomings. First, although the survey sample in this paper comes from the three regions of Jiangsu, namely southern Jiangsu, central Jiangsu and northern Jiangsu, which to a certain extent represents different levels of economic development, the sample is confined to the region of Jiangsu, which is limited to a certain extent. Therefore, the findings of this paper can be validated in more areas in the future. Second, the moderating variables studied in this paper are relatively limited. Future research can further explore other moderating variables that convert the intention to reduce food waste into behavior and how to bridge the intention-behavior gap in reducing food waste, so as to provide theoretical guidance for the formulation of relevant government policies.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

References

Ajzen I, Fishbein M, Lohmann S, Albarracin D (2018) The Influence of Attitudes on Behavior. Handb Attitudes 2014:187–236

Amirudin N, Gim T-HT (2019) Impact of perceived food accessibility on household food waste behaviors: a case of the Klang Valley, Malaysia. Resour Conserv Recycling 151:104335

Aschemann-Witzel J, Asioli D, Banovic M, Perito MA, Peschel AO, Stancu V (2023) Defining upcycled food: The dual role of upcycling in reducing food loss and waste. Trends Food Sci Technol 132:132–137

Attiq S, Chau KY, Bashir S, Habib MD, Azam RI, Wong W-K (2021) Sustainability of household food waste reduction: a fresh insight on youth’s emotional and cognitive behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(13):7013

Cerrah S, Yigitoglu V (2022) Determining the effective factors on restaurant customers’ plate waste. Int J Gastronomy Food Sci 27:100469

Chen J, Lobo A (2012) Organic food products in China: determinants of consumers’ purchase intentions. The international review of retail. Distrib Consum Res 22(3):393–314. The international review of retail, distribution and consumer research 22(3): 293-314

Chen MC, Qin L, Cheng GY (2023) Practicing a greater food approach: challenges, goals and pathways for food system transformation in China. issues in Agricultural Economy (05):4-10

Chen YQ, Zhu H, Le M, Wu YZ (2014) The effect of face consciousness on consumption of counterfeit luxury goods. Soc Behav Personality: Int J 42(6):1007–1014

Coşkun A, Yetkin Özbük RM (2020) What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag 117:170–178

Dawson IGJ (2018) Assessing the effects of information about global population growth on risk perceptions and support for mitigation and prevention strategies. risk Anal 38(10):2222–2241

De Laurentiis V, Caldeira C, Sala S (2020) No time to waste: assessing the performance of food waste prevention actions. Resources. Conserv Conserv Recycling 161:104946

Dong XM, Jiang BC, Zeng H, Kassoh FS (2022) Impact of trust and knowledge in the food chain on motivation-behavior gap in green consumption. J Retail Consum Serv 66:102955

Farr-Wharton G, Foth M, Choi J (2014) Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. journal of consumer. Behaviour 13(6):393–402

Fazal-e-Hasan SM, Mortimer G, Ahmadi H, Abid M, Farooque O, Amrollahi A (2023) How tourists’ negative and positive emotions motivate their intentions to reduce food waste. J Sustain Tour 32(10):2039–2059

Fraj-Andrés E, Herrando C, Lucia-Palacios L, Pérez-López R (2023) Intention versus behavior: integration of theories to help curb food waste among. Br Food J 125(2):570–586

Gao EX, Wang XW (2021) A framework of NUDGES and policy instruments for behavioral public policy innovation: with the behavioral insights team as a case in point. J Xiangtan Univ (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 45(01):16–21

Geng JC, Long RY, Chen H (2016) Impact of information intervention on travel mode choice of urban residents with different goal frames: a controlled trial in Xuzhou. China Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 91:134–147

Graham-Rowe E, Jessop DC, Sparks P (2014) Identifying motivations and barriers to minimizing household food waste. Resour, Conserv recycling 84:15–23

Hamerman EJ, Rudell F, Martins CM (2018) Factors that predict taking restaurant leftovers: strategies for reducing food waste. journal of consumer. Behaviour 17(1):94–104

Hassan HF, Ghandour LA, Chalak A, Aoun P, Reynolds CJ, Abiad MG (2022) The influence of religion and religiosity on food waste generation among restaurant clienteles. Front Sustain Food Syst 6:1010262

Hoare RJ, Butcher K, O’Brien D (2011) Understanding Chinese diners in an overseas context: a cultural perspective. J Hospitality J Hospitality Tour Res 35(3):358–380

Hu HC (1944) The Chinese concepts of “face”. Am Anthropologist 46(1):45–64

Huang HY, He JX, Zhu LJ (2021) A Comparative Study on the Mechanisms of How Consumer Cosmopolitanism, Xenocentrism, and Ethnocentrism Influence Brand Attitudes: The Moderating Roles of Positive and Negative Effects of “Face”. Nankai Bus Rev 24(02):13–26

Jiang WJ, Yan TW (2020) Study on the Consistency of Farmers’ Straw Returning Willingness and Behavior under the Dual Drive of Ability and Opportunity: A Case Study of Hubei Province. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition) (01):47-55+163-164

Johnson DR, Creech JC (1983) Ordinal measures in multiple indicator models: A simulation study of categorization error. Am Sociol Rev 48(3):398–407

Juan Li J, Su C (2007) How Face Influences Consumption - A Comparative Study of American and Chinese Consumers. Int J Mark Res 49(2):237–256

Kinnison LQ (2017) Power, integrity, and mask-An attempt to disentangle the Chinese face concept. J Pragmat 114:32–48

Kunasekaran P, Mostafa Rasoolimanesh S, Wang M, Ragavan NA, Hamid ZA (2022) Enhancing local community participation towards heritage tourism in Taiping. Malays: application Motiv -Oppor -Abil (MOA) model J Herit Tour 17(4):465–484

Laskey Henry A, Fox Richard J, Crask Melvin R (1995) The relationship between advertising message strategy and television commercial effectiveness. J advertising Res 35(2):31–40

Le Monkhouse L, Barnes BR, Stephan U (2012) The influence of face and group orientation on the perception of luxury goods: A four market study of East Asian consumers. Int Mark Rev 29(6):647–672

Li C, Shao Y (2020) How to improve the consistency of intention and behavior in the context of green consumption? J Arid Land Resour Environ 34(08):19–26

Li M, Cui HJ (2021) Face consciousness and purchase intention of organic food: the moderating effect of purchase situation and advertising appeal. Br Food J 123(9):3133–3153

Lian DX, Gao Y, Liu XO (2022) Study on food waste behavior based on uncertainty constraints. Economic Theory Bus Manag 42(08):37–48

Liao CH, Hong J, Zhao DT, Zhang S, Chen CH (2018) Confucian Culture as Determinants of Consumers’ Food Leftover Generation: Evidence from Chengdu, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25(15):14919–14933

Liao F (2022) On influencing factors of food waste behavior based on extended MOA model. J Shanxi Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 21(05):99–108

Liu JG, Lundqvist J, Weinberg J, Gustafsson J (2013) Food losses and waste in China and their implication for water and land. Environ Sci Technol 47(18):10137–10144

Maclnnis DJ, Moorman C, Jaworski BJ (1991) Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from ads. J Mark 55(4):32–53

Malefors C, Sundin N, Tromp M, Eriksson M (2022) Testing interventions to reduce food waste in school catering. Resour Conserv Recycl 177:105997

Mattila AS (1999) Do emotional appeals work for services? Int J Serv Ind Manag 10(3):292–307

Melbye EL, Onozaka Y, Hansen H (2017) Throwing it all away: exploring affluent consumers’ attitudes toward wasting edible food. J Food Products Mark 23(4):416–429

Mi LY, Yu XY, Yang J, Lu JW (2018) Influence of conspicuous consumption motivation on high-carbon consumption behavior of Residents: an empirical case study of Jiangsu province, China. J Clean Prod 191:167–178

Mo T (2021) “Income vs. education” revisited-the roles of “family face” and gender in Chinese consumers’ luxury consumption. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 33(4):1052–1070

Nabi N, Karunasena GG, Pearson D (2021) Food waste in Australian households: role of shopping habits and personal motivations. J Consum J Consum Behav 20(6):1523–1533

Nguyen HV, Nguyen CH, Hoang TTB (2019) Green consumption: closing the intention-behavior gap. Sustain Dev 27(1):118–129

Nunkoo R, Bhadain M, Baboo S (2021) Household food waste: attitudes, barriers and motivations. Br Food J 123(6):2016–2035

Parfitt J, Barthel M, Macnaughton S (2010) Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos Trans R Soc B: Biol Sci 365(1554):3065–3081

Pearson D, Perera A (2018) Reducing food waste: a practitioner guide identifying requirements for an integrated social marketing communication campaign. Soc Mark Q 24(1):45–57

Qi D, Roe BE (2016) Household food waste: multivariate regression and principal components analyses of awareness and attitudes among US consumers. Plos One 11(7):e0159250

Redding SG, Michael N (1983) The role of “face” in the organizational perceptions of Chinese managers. Stud Manag Organ 13(3):92–123

Shi ZM, Zheng WY, Kuang ZY (2017) The Difference of FACE Measurement between Reflective Model and Formative Model and the FACE Influence on Green Product Preference. Chinese. J Manag 14(08):08–1218

Soma T, Li B, Maclaren V (2021) An evaluation of a consumer food waste awareness campaign using the motivation opportunity ability framework. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 168: 1013-1134. Conserv Recycling 168:105313

Stancu V, Haugaard P, Lähteenmäki L (2016) Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: two routes to food waste. Appetite 96:7–17

Stöckli S, Dorn M, Liechti S (2018) Normative prompts reduce consumer food waste in restaurants. Waste Manag 77:532–536

Supryadi DI, Sudiro A, Rohman F (2022) Post-Pandemic Tourism Marketing Strategy Towards Visiting Intentions: the Case of Indonesia. Qual - Access Success 23(191):28–37

Tang DX, Wang Q (2021) Diet Anthropological Study of Food Waste Problem in Chinese Dining Table. J Qinghai Minzu Univ (Soc Sci) 47(03):1–10

Van Geffen L, van Herpen E, Sijtsema S, van Trijp H (2020) Food waste as the consequence of competing motivations, lack of opportunities, and insufficient abilities. Resour, Conserv Recycling: X 5:100026

Verain MCD, Dagevos H, Antonides G (2015) Sustainable food consumption. product choice or curtailment? Appetite 91:375–384

Visschers VHM, Wickli N, Siegrist M (2016) Sorting out food waste behavior: a survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J Environ Psychol 45:66–78

Vittuari M, Garcia Herrero L, Masotti M, Iori E, Caldeira C, Qian Z, Bruns H, van Herpen E, Obersteiner G, Kaptan G, Liu G, Mikkelsen BE, Swannell RP, Kasza G, Nohlen HU, Sala S (2023) How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: a literature review on drivers and levers for behavioral change. Sustain Prod Consum 38:104–114

Vittuari M, Masotti M, Iori E, Falasconi L, Gallina Toschi T, Segrè A (2021) Does the COVID-19 external shock matter on household food waste? The impact of social distancing measures during the lockdown. Resour, Conserv Recycling 174:105815

Waitt G, Phillips C (2016) Food waste and domestic refrigeration: a visceral and material approach. Soc Cultural Geogr 17(3):359–379

Wang JM (2013) The influence of resource conservation awareness on resource conservation behaviour:An interaction and moderating effect model in the context of Chinese culture. Manag World (08):77–90

Wang LE, Hou P, Liu XJ (2018) The connotation and realization way of sustainable food consumption in China. Resources. Science 40(08):1550–1559

Wei J, Zhang LL, Yang RR, Song ML (2023) A new perspective to promote sustainable low-carbon consumption: The influence of informational incentive and social influence. J Environ Manag 327:116848

Wen ZL, Hou ZT, Zhang L (2005) A Comparison of Moderator and Mediator and Their Applications. Acta Psychol Sin 37(02):268–274

Zhang TZ, Yan TW, He K, Zhang JB (2019) Contrary of farmers’ willingness of straw utilization to the behavior: based on the MOA model. J Arid Land Resour Environ 33(09):30–35

Zhang WH, Liu XW, Li YF (2024) The impact of face consciousness on food waste: Promotion or inhibition? J Arid Land Resour Environ 38(02):88–95

Zhang XA, Cao Q, Grigoriou N (2011) Consciousness of social face: The development and validation of a scale measuring desire to gain face versus fear of losing face. J Soc Psychol 151(2):129–149

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Important Projects of the National Social Science Fund of China (No.20&ZD117).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS supervised the research outcome and the final writing. QL processed the data, and carried out manuscript writing and revising. XT contributed to the conception and design of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University for exemption from ethical review (Date: 16 June 2023). The Medical Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University stipulates that the use of anonymized information to conduct interviews and surveys that do not cause harm to human beings and do not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests is exempt from ethical review. The conduction of questionnaire survey of this study was anonymized and did not cause harm to the respondents. Meanwhile, it did not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests, and did not disclose the personal privacy of any respondents. Therefore, our survey is in line with the type of ethical review that can be exempted as stipulated by the Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

We conducted field surveys in July-August 2023 in Wuxi, Yangzhou, Huai’an and Lianyungang in Jiangsu Province. There is a written informed consent for participation on the front page of the questionnaire. In this manner, we inform the respondents of the purpose of the questionnaire and guarantee the anonymity of their personal information. In addition, we promise that the collected data will be used for research purposes only and will not be used for commercial purposes and that there are no risks involved in participating. After reading the informed consent, only when the respondent agrees to take the survey will he/she be able to start answering the questionnaire. No data were collected from anyone under 18 years old.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shan, L., Lu, Q. & Tong, X. How to improve the consistency of consumers’ food waste reduction intentions and behaviors? An analysis based on the expanded Motivation–Opportunity–Ability framework. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1530 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03975-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03975-6