Abstract

This study aims to enhance the industrial employability of PhD graduates through the development of the HIRES-PhD framework, an abbreviation of High Impact Research and Employability Skills for the PhD. It identifies and categorizes essential transversal skills. Using a systematic literature review and thematic analysis, we screened 828 papers and selected 39 relevant studies to compile a database of 236 transversal skills. These skills were organized into 16 categories and further distilled into four overarching themes. The HIRES-PhD Framework is compared with traditional models like DOTS, USEM, and MCPHE, as well as recent European initiatives such as DocTalent4EU and OUTDOC. This comparison highlights the framework’s unique focus on doctoral training and industrial employability, unlike traditional models which often target broader educational contexts. Our findings emphasize the importance of a holistic approach to transversal skills training, tailored specifically to the needs of PhD graduates. The HIRES-PhD Framework serves as a comprehensive, data-driven tool for designing PhD programmes that align with industry demands, ensuring that doctoral training is relevant and effective in enhancing employability. In conclusion, the HIRES-PhD Framework significantly contributes to the improvement of doctoral education by providing a structured approach to transversal skills development, thus bridging the gap between academic training and industrial needs. This framework is a valuable resource for policymakers, educators, researchers, and employers aiming to optimize PhD programmes for better employment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This study focuses on transversal skills that influence the PhDs’ employability beyond academe. In this paper, we introduce the framework HIRES-PhD, an abbreviation of High Impact Research and Employability Skills for the PhD. It is a theoretical framework that consists of a two-level thematic reduction of 236 PhD transversal skills identified from the systematically selected scientific literature in the topic. This framework facilitates course design and hiring processes. It also serves as a self-reflective tool for the doctorates that helps them recognize the transversal skills that they possess or must develop. HIRES-PhD does not promise to serve as a mechanism for doctorate employability guarantee. And its components are not the variables of an output-oriented model. Rather HIRES-PhD is the thematic synthesis of concepts from the literature of PhD transversal skills. The HIRES-PhD is a fusion of logical data-based efforts and the derivation of meaning from it. It is the developmental tool for the doctoral stakeholders to utilize researched knowledge for informed transversal skills decision making. These features help suffix HIRES-PhD with ‘framework’ rather than a ‘model’. Framework is a set of structured outlines which are developing in nature to solve problems, achieve objectives, or make progress in its own evolution (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994). The HIRES-PhD’s primary aim is not a guarantee but a credible base for a doctorate’s success. The HIRES-PhD shall be an evolving framework since the dynamism of the professional landscapes today inspires the higher education to adapt constantly.

In this study, we focus on transversal skills. By transversal skills, we mean those skills for doctorates which has multiple domains of application. This definition follows the ideas from Dāvidsone et al., who understand these skills as '…behaviours that can be used within a wide range of contexts including different functions and activities.' (p.728, 2021), and from Mariani et al., who point out that those transversal skills are '…not specifically related to a particular job, task, academic discipline, or area of knowledge, but which can be used in a wide variety of situations and work settings.' (pp. 45-46, 2020). Highlighting the paramount importance of transversal skills in doctoral studies, numerous studies and proposals have underscored their significance. For instance, the Trends II report from the European University Association (EUA) (Haug & Tauch, 2002), showcased the advancing harmonization of doctoral studies and the establishment of doctoral schools. Parallelly, one of the principles in Bologna Seminar on 'Doctoral Programmes for the European Knowledge Society' encouraged PhDs’ interdisciplinary transversal skills development (Bologna Process, 2005). Thus, established doctoral schools today strive in the same direction (Poyatos Matas, 2012).

In the past, the Joint Skills Statement (Research Councils/AHRB, 2003), and the Researcher Development Framework (VITAE, 2012), suggested researchers’ career development actions primarily focussed towards higher education roles. Today, a keen focus on transversal skills education has been adopted as the means for smoother industrial transition of the PhDs. European Union organizations fund reports for PhD transversal skills identification, reflecting an urgency to address the issue. The reports identify these skills through industrial stakeholders’ job ads (Minea, 2023), and surveys (Držanič & Fišer, 2021), showcasing the present state of affairs. Multiplying developments despite the existing traditional models that resonate with transversal human calibre like the DOTS model (decision learning, opportunity awareness, transition learning and self-awareness) (Law & Watts, 1977), USEM (understanding, skills, efficacy beliefs and metacognition) Employability Model (Knight & Yorke, 2002), and the Model of Course Provision in Higher Education (Bennett et al., 1999), reflects upon the escalating demand for a focus in doctoral contexts for industrial job transition.

The perception of employability depends on the different contexts (Römgens et al., 2020; Small et al., 2017). An early understanding of employability reflects upon the ability to secure and maintain satisfying work, relying on one’s skills and attitudes, how they present themselves to employers, and the surrounding labour market conditions (Hillage & Pollard, 1998). Possession of skills, knowledge, and attributes enhancing an individual’s job prospects and adaptability in a changing labour market is a parallel viewpoint (Römgens et al., 2020). Employability definitions, also often expand into models having components for deeper explanation of employability (Behle, 2020; Clarke, 2018; Pool & Sewell, 2007). Recent studies increasingly incorporate perceived employability into quantitative analyses (Ma & Bennett, 2024; Ma & Chen, 2024; Shomotova & Ibrahim, 2024). These varied takes show employability as a dynamic blend of technical and personal competencies. In this study we undertake the perspective of employability, namely the qualities that a PhD holder must have, to be suitable for working in industrial environment. By industrial here we mean the non-academic sectors of work. The landscape of doctoral studies is undergoing a transformation, with an increasing recognition of the importance of industrial job transition alongside traditional academic paths.

Academic positions for doctorates appear limited, and their industrial job transition is perhaps a necessity. For instance, at Poland, ninety percent of doctoral candidates may never be positioned at higher education (Kwiek, 2021). From China, more than half of doctoral participants aimed non-academic jobs (Gu et al., 2017). In a Canadian longitudinal study, 13 doctoral candidates were re-interviewed in a decade’s gap, only 3 were tenure track after years of serving temporary academic positions (Acker & Haque, 2017). In contrast, though, the employment of doctorates in Sweden, Germany and Austria seems stable and efficient (Huisman et al., 2016; Schwabe, 2011), and data in-fact suggests that Germany produced about twenty-nine thousand doctorates in 2016 alone as it is almost a job necessity for them (Kehm, 2020). However, countries efficiently enabling PhD employment may still have an underlying need for developing transversal skills. For example, an Australian report claimed their PhDs successful at labour market, while simultaneously observing certain gaps corresponding to their skills like communication and team collaboration (Western et al., 2007).

Considering the need to open new professional horizons for doctoral candidates and recognizing the necessity of identifying, therefore, new skills, a study like ours becomes paramount. A study in this topic encompassing systematically selected and peer-reviewed studies in a panoptic timeframe, while simultaneously deriving PhD transversal skills database from them, will converge the individual studies towards an applicable theoretical transversal skills framework. Reports in the past have probed limited literature and tabulated identified skills in categories (Bitušíková & Borseková, 2020). However, a larger thoroughly developed data of cited PhD transversal skills from scientific literature is required with rigorous thematic levels of classification, along with its sources like emerging from primary, non-primary studies or just authors’ comments. This will serve as a comprehensive framework for course designs and hiring practices. Additionally, future social scientists can observe a change in the framework by adding to its underlying open-access database. With this aim, we execute a painstaking search and collection of 236 PhD transversal skills from systematically screened 39 research studies, transformed into a framework, and synthesized into knowledge.

The HIRES-PhD Framework and its underlying data of transversal skills emerge from the research papers focussed on industrial needs. It is about fitting the human resources in the economy while improving the skills according to employer needs. This is why our approach aligns with the technocratic rationality of employability (Hooley et al., 2022). Alternatively, a humanistic rationality focuses on the individuals’ personal development instead of the outcome of the labour market. Such a kind of a humanistic rationality is akin to the university missions and ethos, rather than a technocratic approach. This approach shifts the focus towards the students, and away from the employment (Hooley et al., 2022). Another rationality worth noting in the context of PhD transversal skills training is the emancipatory rationality (Sultana, 2014), which is a career guidance approach inspiring liberation through critique and freedom. It addresses the self-reflection and self-knowledge capacity. It is that approach of learning that inspires liberation and realisations. In such an approach one must be on the path of self-expression and self-fulfilment. A training design on a mix of these rationalities can perhaps help the students to realize their reasonings behind their purpose of work. This in turn could solve their hinderances in the development of their transversal skills while securing their future employment.

The remaining of article is structured into four sections unfolds. First, we delve into the methodology, outlining the screening and selection process of research papers, the construction and processing of PhD transversal skills data derived from these papers, and provide access to the open-access link for further exploration. Following this, we present our findings, detailing the characteristics of the selected studies, followed by an exposition of the framework, its synthesis, and pertinent reflections. In the discussion section, we engage in reflective analysis and comparative examination of our findings. Finally, our conclusions contextualize the study within contemporary research paradigms, emphasizing its relevance and applicability, particularly for stakeholders in higher education.

Methodology

Our method of investigation was divided in two stages adhering to a systematic approach. The first stage corresponds to the search and screening of literature. The second stage relates to the PhD transversal skills data identification from it, its thematic processing and synthesis.

Search and literature screening

We began searching for texts with a selected string of keywords. The following points portray the intentions for the keywords.

-

a.

PhD: We chose the keyword ‘PhD’ to find research papers that not only focussed on a research population pursuing doctoral studies but also the population that had completed their doctorate journey. It helped us seek research papers about the overall experience of students during their training and the developed skills in the process.

-

b.

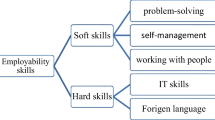

Transversal Skills: We chose the term ‘transversal skills’ to not only identify soft skills. Transversal skills are not limited to soft or hard skills, rather they are the skills that are applied across multiple domains of employment. Therefore, we carefully brainstormed and chose the most suitable search keyword for the purpose of this research.

-

c.

Training: We introduced this keyword to identify the training approaches or methodologies from the literature being used to train doctoral students at transversal skills that help in their diverse employment prospects.

-

d.

Employability: This keyword was introduced to the string to identify results of research texts which had observed the hiring trends among the PhD qualified personnel. We did not restrict it to specific industries or types of institutions.

With the above keywords, we formulated the search string, 'PhD' 'Transversal Skills' 'Training' 'Employability'. The string was entered in Scopus and Web of Science with no results returned. Thus, we eliminated the double quotation marks from the search string which helped us retrieve only two research papers on this topic. Additionally, we searched dimensions.ai an open-access database of research texts. This broadened our scope of search. The string finally returned 828 papers from dimensions.ai by running the keywords in the full text.

We adapted to a systematic approach of elimination by following the steps of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses commonly known as the PRISMA (Page et al., 2021). For this purpose of elimination, we used a systematic review management software, the Covidence. The software enabled the screening of these texts with yes/no buttons and could automatically remove duplicates. It enabled two of us authors’ blind voting with yes/no buttons in the research texts’ selection. While in the event of contrasting views, the third author held the moderation rights for a mutual consensus, facilitated by the tool. These votes for text selection were enabled by certain criterion.

Following was the inclusion criterion:

-

a.

texts had to be in English for all authors of this research paper to comprehend,

-

b.

research papers had to come from a peer-reviewed journal,

-

c.

the papers included were judged from the title and abstract on its potential contribution to the topic.

Exclusions were made based on:

-

a.

the irrelevancy gauged from the title, abstract and full paper, and the insufficiency for the topic,

-

b.

texts that did not originate from a peer-reviewed journal,

-

c.

and if the work seemed to be from a periodical or an institutional report since we aimed to synthesize only research efforts

Region or year of study had no influence in our texts’ inclusion or exclusion. Further, this process has been visualized in the below flowchart. Each of the stages is explained in the following epigraphs.

As shown in Fig. 1, after the screening process, 87 research papers emerged for full-text observation. Papers further withdrawn did not contribute towards the objective or were from an unreliable source from a research perspective. Finally, 39 texts were selected for building the PhD transversal skills database and the synthesis of information.

Data processing and synthesis

Each of the 39 papers was observed to contain transversal skills that enabled industrial employment of PhDs. Noticing a pattern of skills being repeatedly mentioned in the 39 papers we chose to use Thematic Analysis. Some examples could be the ability to lead, coach or motivate a person. We also encapsulate within transversal skills those generic knowledge areas which have been recognised important for a doctorate’s employment prospects, for instance, awareness about intellectual property, data curation and business creation, which may not exactly be skills but have been found crucial in the literature. It helped in harnessing a comprehensive purpose of the HIRES-PhD framework. We built a data of these skills and applied a scientific qualitative methodology, the thematic analysis. It helps identify, analyse, organize, describe, and report the themes found within a data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We follow the different steps of thematic analysis identified by Nowell et al., in 2017 who has transformed them into applicable phases as shown in the following Fig. 2.

Phase 1 data familiarization

Reading each of the thirty-nine papers one-by-one, the 236 transversal skills identified were extracted into a spreadsheet column. This formed our data on which we conducted the thematic analysis. Collecting the data, we recognized its granular aspects. However, it was essential to immerse ourselves fully to gain a comprehensive understanding of its scope. We found that the skills emerged from various approaches, including primary and secondary research, researchers’ expert commentary, and/or the specifically selected transversal skills to explore deeper contexts. Further, we could distinguish these skills based on their methodological origins. Also, the raw data of identified transversal skills in a spreadsheet column served as level one.

Phase 2 initial code generation

In the adjacent spreadsheet column, we coded each transversal skill from the literature into broader categories, forming the second level of our framework with a hypernym perspective. A hypernym represents a broader category, and past studies have utilized this approach for grouping data (Kalaimani et al., 2015; Sunagar et al., 2020). Given the limited number of 236 transversal skills, we opted for a manual process to ensure rigour. This inductive coding established Level 2 of our HIRES-PhD framework, facilitating the analysis and transition of unstructured data into 16 clear codes while simplifying complex granular aspects.

Phase 3 establishing themes

In the third phase, we reviewed the initial coded data and organized these codes into thematic groups based on their relevance. Identifying these themes allowed us to link significant portions of the data. We rigorously revisited the codes assigning themes instead of adopting it from an existing transversal skill framework. This was to reserve the originality and authenticity. The inductive approach in theme assignment has been recognized valid in thematic analysis (Nowell et al., 2017). In this manner, HIRES-PhD framework’s Level 3 was developed.

Phase 4 reviewing themes

During this phase, we reviewed the coded data extracts for each theme to identify any patterns. We considered the relevance of individual themes and considered whether they accurately reflected the meanings from the data. The end of this phase ensured that we conveyed a good idea of the different themes, how they align, and the overall narrative conveyed by the data.

Phase 5 defining and naming themes

Here we defined the themes, ensured that we captured relevant aspects of the data. This involved a meticulous interpretation on the themes’ fit into the overall story, to improve clarity and credibility. Themes were reviewed and modified until all data was thoroughly analysed and represented. As reflected by Nowell et al. (2017) the final theme names should be punchy, reflecting the voices within the data.

Phase 6 producing the report

This is the final phase of thematic analysis, where researchers write a coherent, logical, and credible report of their findings. It emphasized the need for clear communication, interpretation beyond mere description, and the integration of literature supporting claims.

The process is evident in the below data link. However, the same is better visible at the ‘Findings’ section’s Tables 2–5 with methodological origins. The Fig. 3 also represents sixteen codes of Level 2 overarched by the themes of Workmanship, Charisma, Empowerment and Tenacity in Level 3.

Open-Access Data Link: https://doi.org/10.34810/data1276.

Findings

The screened set of papers

Table 1 presents the 39 screened texts and its attributes like the type of study, study sample, data collection and geographical contexts. The main point of this table is to recognise the way transversal skills are being identified while highlighting the geographic region being focussed on, in the studies. This was essential for planning of future investigations in this topic for avoiding excessive focus in one region and to attain a methodological reference. The table offers two major deductions. First, is that thirty-one studies use qualitative methods like surveys, interviews, and case studies. Secondly, the literature is mostly available in European contexts.

From the papers of Table 1, we collect 236 transversal skills. The results of the thematic analysis on these skills are represented in Tables 2–5. The tables reflect four broad themes: workmanship (Table 2), charisma (Table 3), empowerment (Table 4), and tenacity (Table 5). Inside these tables are the sub-themes (Level 2) and the specific transversal skills (Level 1) identified along with its source and the nature of the study.

In each table, the skills are divided into three columns. In the first column, we identify those skills which were found in papers adopting the primary methods of research. The second column represents those transversal skills that were identified from papers using non-primary research methods. This could be through secondary sources, document analysis or a random selection of generally accepted transversal skills, for the purpose of further investigation. The last column represents those transversal skills that were authors’ own comments, views, and opinions in a research paper. The last column also showcases those skills that formed the central subject of the paper. For example, if a paper studied only entrepreneurship in doctoral training and found it useful in industrial jobs, thus entrepreneurship was listed in the third column.

HIRES-PhD framework: high impact research and employability skills for a PhD

In Tables 2–5, we observe that the authors from various research studies have discussed the PhD relevant transversal skills. These tables provide the transversal skills data and its corresponding themes evolving it into applicable knowledge. Hence, we present a refined perspective of this knowledge for the ease of its interpretation and application. In Fig. 3, we introduce the HIRES-PhD, a high impact research and employability skills PhD framework, drawing insights from Tables 2–5. Authors of this subject area have been contributing to the topic of transversal skills for PhDs’ diverse employment prospects. And the HIRES-PhD conceptual theoretical framework serves as the point of convergence of these common efforts while visually representing its thematic classifications.

The framework from Fig. 3 reflects upon the high impact research and employability skills for a PhD. The sections of the outermost circle in Fig. 3 are the level 2 sixteen codes from the overall 236 identified skills. Further four themes form the level 3 that had emerged from these sixteen codes, are presented in the corresponding innermost sections of the circle. In the following epigraphs, we discuss the insights drawn under these themes and sub-themes.

Workmanship

These skills enable the cooperation in the application of practical information. With workmanship abilities, we highlight skills like knowledge transfer, basic technological acumen, teamwork, and management.

Knowledge transfer encompasses the information dissemination capacities between entities. It can entail the local implementation of practical knowledge (Medina et al., 2020), and the awareness of knowledge boundaries (Shackleton & Messenger, 2021). Teaching skills are demanded beyond academics (Khaouja et al., 2019). This requires coaching, and identifying the learners’ needs, especially if they are challenged in any way (Khasanzyanova, 2017). University-business cooperations revolve around transfer of knowledge (Orazbayeva et al., 2019), signifying doctoral students in the process (Santos et al., 2020). Since doctoral students train at teaching (Freitas et al., 2018), it helps transfer expertise in non-academic sectors. Additionally, they hone their learning skills for working at enterprises (Cinque, 2016). A life-long learning approach is however not very common among industries (Anastasiu et al., 2017). Enterprises work with expeditious analytics and statistics. These skills relate to PhD students as they develop research skills, statistical literacies and scientific research methods (Atenas et al., 2015).

Technology skills highlight the proficient use of common tools, computers and data. In other words, it is the ability to recognize and work with the potential upcoming technologies (Shackleton & Messenger, 2021). Synthetic skills are one such example (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019), that reflects data-backed decision-making. Technical or technological skills have been acknowledged by businesses (Olo & Correia, 2022), and evidence reflects the efforts in developing students’ digital skills (Fabbri & Romano, 2019), like using open data in PhD skill training (Atenas et al., 2015). Though, students and employers may value other skills over technical skills (Anastasiu et al., 2017; Caeiro-Rodriguez et al., 2021), the transversality of technical skills cannot be ignored completely as industrial participants actively seek for digital skills (Olo & Correia, 2022). Like Freitas et al., in 2018 found a demand for software proficiency in doctorates and, Kismihók et al., in 2022 comment data management important across professions.

Teamwork reflects collaboration and coordination. And a brainstorming process can help recognize the optimal roles in a team setting (Pardo-Garcia & Barac, 2020). Teamwork is an employment enhancer for students (Olo & Correia, 2022) and is keenly emphasised in doctoral training (Anastasiu et al., 2017). Intercultural and interdisciplinary collaboration, in industrial hiring further highlights its importance (Martins et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2018). A reformed training can enhance this skill (Vittorio, 2015). Both, the employers, and the PhD students demand for its further development (Isaacs, 2015; Suleman et al., 2021). The career services in a university has the capacity to contribute in this direction (Boffo, 2019). Parallelly, teamwork is associated with colleague interaction abilities (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019). It facilitates problem-solving and project management (Rossano et al., 2016). Evidence reflects its priority in multiple industries along with medical science and justice (Khaouja et al., 2019; Martins et al., 2021).

Management refers to the administration of tasks and resources. Institutions adopt innovative approaches for improving resource and activity management abilities (Cinque, 2016; Icociu et al., 2019; Malik & Setiawan, 2015). Time management is a transversal skill (Kismihók et al., 2022; Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019), and PhDs recognize its importance (Edinova, 2020). They develop time management skills for their cross-sector employability (Freitas et al., 2018; Martins et al., 2021). Similarly, project management skills also hold relevance for doctorates (Cinque, 2016; Vittorio, 2015). Employers realise its importance (Anastasiu et al., 2017; Khasanzyanova, 2017) and expect them to possess it (Kismihók et al., 2022; Martins et al., 2021). Students sometimes perceive their project management skills underdeveloped (Isaacs, 2015), and university-business collaborations help in overcoming this perception (Rossano et al., 2016). One can face uncertainty while managing projects. Thus we also find PhDs being tested at managing uncertainty for their non-academic careers (Azzini et al., 2018; Azzini et al., 2019; Marrara et al., 2021).

Charisma

Through charisma, we highlight not only skills of proficient communication but also the capacity to delve into fruitful networking and socializing while possessing the emotional intelligence to translate it into leadership as situation demands.

Communication skills are the ideas and information dissemination abilities. This could be ranging from the curriculum vitae designing abilities to excelling at personal interviews, considering its significance for securing a work position (Medina et al., 2020). Communication involves an active and attentive listener. And volunteering activities are found to develop students’ listening skills (Khasanzyanova, 2017). This however is possible with good linguistic command over a language. Linguistic competencies are identified enriching for students by Olo & Correia, in 2022, while Rossano et al. (2016) find the importance of foreign language skills for students’ motivation and perceived benefits. However, challenges persist when human resource managers find graduates lacking written and oral communication skills (Suleman et al., 2021). A survey among the employers of doctoral students found a demand for assertive communication, science communication, and presentation skills (Freitas et al., 2018). Based on this survey they developed a course for doctoral students training them at these skills for reaching non-specialized audiences and scientific writing/publishing.

Networking and social skills reflect the relationship-building abilities. It encompasses the ability to be aware of one’s actions and words while simultaneously establishing bonds. Diverse environments call for cultural sensitivity contributing in effective global citizenship (Atenas et al., 2015), and intercultural awareness (Kismihók et al., 2022). Perhaps for this reason, networking, and social skills, are the most sought-after skills in the job market (Khaouja et al., 2019). Likewise, it is valued in doctoral training and hiring (Azzini et al., 2018; Kismihók et al., 2022; Kehm, 2020; Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Marrara et al., 2021). Melacarne & Nicolaides, in a 2019 study, makes close associations of negotiation and interpersonal skills with the ability to interact with colleagues and employees. Such skills are essential for the PhDs (Isaacs, 2015). However, the firms report students lacking enough behavioural and social skills (Suleman et al., 2021). And university-industry collaboration has been claimed as one of the ways to improve it (Medina et al., 2020).

Emotional intelligence or EI encapsulates the aptitude, perception, and interpretation of feelings. Employers suggest that EI enhances students’ employability (Olo & Correia, 2022; Pool & Sewell, 2007). Several skills and qualities of EI are sought across industries. Like respect, accountability (Khaouja et al., 2019) and stress tolerance (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019). Moreover, PhD students perceive themselves tolerant in ambiguous situations (Smith et al., 2014). Another example of EI is empathy (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019). Empathy is of importance for researchers in technical fields like engineering (Martins et al., 2021). Similarly, ethics and privacy are essential aspects in professional life (Kismihók et al., 2022) and sometimes students may lack for its sensitivity (Picard et al., 2021). It can encompass a sense of justice, integrity, or responsibility (Shackleton & Messenger, 2021). A study revealed students improved at certain EI abilities like morality, work ethics, task responsibility, confidence and open-minded with practical training (Malik & Setiawan, 2015). Open-mindedness is sign of EI as it improves one’s receptivity (Khasanzyanova, 2017).

Leadership incorporates group direction towards a common goal while maintaining high spirits. Leadership is one of the major transversal skills being taught in European higher education institutions, especially in the case of PhD students’ labour market employment prospects (Cinque, 2016). Similarly, the consultation of diverse stakeholders identified influence and leadership crucial for preparing PhDs for the industry (Rodrigues et al., 2018). Industrial participants can have a distinct and keen emphasis on leadership skills (Anastasiu et al., 2017). This is perhaps better witnessed in institutions with engineering domains (Martins et al., 2021). As contrastingly Santos (2021) observes a deficiency in the leadership skills of PhD holders, a requirement in industry, whereas Isaacs's (2015) research reveals that certain European doctoral students would opt for team leadership training if given a chance to repeat their studies.

Empowerment

With empowerment abilities, we incorporate the skills that strengthen PhDs at self-reflection, financial independence, adaptability, and flexibility, while maintaining creativity and innovativeness.

Self-skills enable personal and professional betterment through habit regulation. Self-analysis/observation abilities can result from pursuing a PhD (Edinova, 2020). However, they be low on self-awareness capacities during an industrial job transition (Hnatkova et al., 2022). Skills like self-efficacy, self-confidence (Pool & Sewell, 2007) and self-esteem (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019) enable employability. This involves mental well-being, which is useful in various professional aspects (Kismihók et al., 2022). Evidence shows universities equipping students with personal development skills (Cinque, 2016). Moreover self-management, is a student’s major motivation in project participation (Rossano et al., 2016). This can involve a sense of independence, which is also valued in hiring prospects (Khaouja et al., 2019). Such general mental abilities can predict one’s career advancement prospects (Mainert et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurship skills, identifying the business accumen, profit pursuing, ingenuity and risk-taking qualities. Experts suggest doctoral training develops a risk-taking propensity (Hnatkova et al., 2022). And research students may perceive themselves as entrepreneurial risk-takers (Smith et al., 2014), as observed in UK (Smith et al., 2014). Employers recognize entrepreneurship (Anastasiu et al., 2017), and seek PhDs bringing additional business value (Terzaroli, 2019). They expect skills for business creation (Freitas et al., 2018), and consumer orientatedness in PhD hiring (Rodrigues et al., 2018). European Commission promotes industrial doctorates, with the hope of bringing research outputs to the market (Vittorio, 2015). Alongside, university-business cooperations develop students’ entrepreneurial accumen (Orazbayeva et al., 2019; Pardo-Garcia & Barac, 2020; Santos et al., 2020). Thus, institutions train PhD students at entrepreneurship for industrial employment (Martins et al., 2021; Pisoni et al., (2020); Terzaroli, 2019). Still, employers indicate a need for better efforts in this direction (Olo & Correia, 2022), like a focus on service orientation, i.e seeking ways to help people (Icociu et al., 2019).

Adaptability and flexibility help to adjust and thrive in diverse or dynamic circumstances. In a 2016 paper by Cinque, PhD students trained at adaptability to changes, for industrial employment opportunities. Similarly, another study focusing doctoral training highlighted the ability at responding to changes, a crucial transversal skill in doctoral training (Rodrigues et al., 2018). We find adapting to new situations (Medina et al., 2020), or new ways of working (Shackleton & Messenger, 2021) as skills that either the students were being trained at or it is expected from them in their employment prospects. Moreover, labour market seeks cognitive flexibility (Icociu et al., 2019), which is a catalyst for developing adaptability. Furthermore, having flexibility and adaptability require an individual to be patient. Volunteering activities have proven to develop patience among participants (Khasanzyanova, 2017). In conclusion, cultivating adaptability and flexibility is an essential transversal skill, that increases the chances of employability in an individual.

Creativity and innovation highlight the inventive and modificative capabilities of a person. Isaacs, (2015) comments that a learning society needs highly qualified polymaths who take creative initiatives. Doctoral training aims to produce creative risk-takers (Hnatkova et al., 2022) and diverse methods have been adopted to develop innovation and creative thinking skills (Malik & Setiawan, 2015; Pardo-Garcia & Barac, 2020; Pisoni et al., (2020). Alongside, automation in PhD hiring, also witnesses ‘creativity’ a testing criteria (Azzini et al., 2018; Azzini et al., 2019; Marrara et al., 2021). This is perhaps because businesses find creativity enhancing for the students’ skillset (Olo & Correia, 2022). A UK study found research students confident at creativity and innovation skills (Smith et al., 2014). In fact in America, creativity was found as one of the top skills (Khaouja et al., 2019). Thus the future education has a keen focus on creativity and innovation among other skills (Icociu et al., 2019).

Tenacity

Through the acumen for tenacity, we group together all those skills which reflect the ability to commit, maintaining prolonged motivation, while being careful to prevent hindrances. In the event of encountering an obstacle, tenacity entails problem solving abilities and tactical proficiencies.

Commitment and motivation skills indicate consistency, fervour, and zeal. One example is discipline, that PhD students in Russia, believed was crucial for their future success (Edinova, 2020). Goal-orientation is rather challenging for the PhDs to successfully showcase it (Hnatkova et al., 2022). Further, we incorporate rigour as a transversal skill that Khaouja et al., in 2019 found as one of the top skills demanded from Moroccan job adverts. It further reported that adverts emphasized on motivation skills, i.e. their willingness to meet the company’s goals. Further, we find PhD trainings inclusive of proactivity for doctorate employment prospects (Boffo, 2019). Resilience and results orientation highlighted as crucial transversal skills (Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019; Shackleton & Messenger, 2021), are essential for enhancing performance and employability.

Carefulness indicates precisive focus on the detail while preventing errors in operations. Applications that help test the PhD qualified for their transversal skills include carefulness in their list of skills (Azzini et al., 2019; Marrara et al., 2021). This was based on a taxonomy from a 2018 work, where the PhD-qualified individuals seeking employment were examined for their ability to be careful among other skills (Azzini et al., 2018). Another study from 2018, by Rodrigues et al., mentions a course, designed with the advice industry participants, that trained PhD students at various skills, among which stood attention to detail and attention to the broader picture. Since attention to detail and the overall picture keep the individual conscious about staying on track, we include it under the category of carefulness. In conclusion, carefulness of an individual is essential for the employability prospects of a PhD.

Problem solving enables the ability to overcome challenges. A rigorous research is a problem-solving endeavour. It involves instances of conflict resolution as the PhD journey is a back-and-forth of challenging and defending findings. Industries benefit from human resources with such an experience. In today’s dynamic workplace, employers find the ability resolve conflicts, enriching for a students’ hiring prospects (Olo & Correia, 2022). In future trainings, we anticipate a growing focus on complex problem-solving skills (Icociu et al., 2019; Melacarne & Nicolaides, 2019), as it helps one’s career advancement (Mainert et al., 2015), and correlates well with the team working skills of an individual (Rossano et al., 2016). University courses or PhD programmes provide a fertile ground for honing such skills (Boffo, 2019; Caeiro-Rodriguez et al., 2021; Malik & Setiawan, 2015; Martins et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2018). However, there’s often a gap in translating these academic problem-solving abilities into practical workplace solutions (Suleman et al., 2021).

Tactical proficiencies entail thoughtful foresight preceding actions. Melacarne & Nicolaides, (2019) comment analytical and decision-making abilities in demand by the employers. And student projects prove adept for students’ overall planning skills (Picard et al., 2021). However, the experts claim that PhDs fall behind at showcasing their strategic planning despite having the capabilities for it (Hnatkova et al., 2022). Companies suggest doctoral trainings can do better at developing students’ planning abilities (Santos, 2021). For this, institutions adopt trainings that enhance strategic decisions and critical thinking (Malik & Setiawan, 2015; Rodrigues et al., 2018). Capstone projects of students are proven adept for students’ overall planning skills (Picard et al., 2021). Since a capacity for reflection and development or critical thinking is a standard occupational need (Shackleton & Messenger, 2021). Expert opinions suggest that PhDs’ ability for critical thinking is valuable in various professions (Hnatkova et al., 2022). Future training may emphasise the development of critical thinking and appropriate judgement abilities (Icociu et al., 2019).

Discussion

In the past decades, some notable conceptualizations have resonated with transversal skills development. They’ve formed the foundational perceptions and intentions in competency training. These conceptualisations have helped shape the transversal skills’ identification and development throughout the decades. Even today, they provide the groundwork in the preliminary understanding of this subject area. The HIRES-PhD framework has common and different aspects with these traditional concepts. As a representative set of the traditional knowledge on transversal skills, we contrast the DOTS model (decision learning, opportunity awareness, transition learning and self-awareness) (Law & Watts, 1977), USEM model (understanding, skills, efficacy beliefs and metacognition) (Knight & Yorke, 2002), and the Model of Course Provision in Higher Education (MCPHE) (Bennett et al., 1999), with the HIRES-PhD framework. These contrasts give a synthesized overview of their ultimate purpose, organisation, and application.

Where the HIRES-PhD Framework has the specific purpose of enhancing industrial employability of doctorates, the DOTS model stems from the calibre development of school children in the 1970s’ United Kingdom (Law & Watts, 1977). DOTS’s components emerge from the authors’ views. For this, the model has also received critique in its suitability for career researchers (McCash, 2006). On the contrary, the USEM model and the MCPHE, focus on not only on higher education but also approach it with the perspective of employment. Where the USEM model portrays interactions between its variables like understanding, skills, efficacy beliefs and metacognition that collectively lead to employability (Knight & Yorke, 2002); the MCPHE organizes combinations between generic skills, disciplinary skills, disciplinary content, workplace awareness and workplace experience for targeted learning outcomes (Bennett et al., 1999).

HIRES-PhD framework shares the broader purpose of these traditional models. Like skill building during studentship, recognising the dimension of employability, and the identification of contributing factors in the transversal skills enhancement. The HIREs-PhD framework is a guiding apparatus for the design of processes and actions in the concerned issue whereas the traditional models manifest as independent processes. They suggest a niche approach for a broad set of receivers, conversely, the HIRES-PhD is a broad approach for niche set of receivers. Traditional concepts focus on varied studentships and not exclusively on the doctoral studies. This is an important point to note as doctoral studies differ from other studentships. At this level, the purpose is not only to absorb knowledge but also to produce, invent or discover it.

Realizing this, initiatives were undertaken with an exclusive focus on the enhancement of doctorate employability. These initiatives were focused on the development of doctoral talent aiming for an academic career in the 2000s and the 2010s. The undertaken steps translated into skill development guidelines for PhD students. Their identified abilities focussed on the development of diverse skill sets, some of which were transversal. A skills training requirements statement, commonly known as the Joint Skills Statement (JSS) (Research Councils/AHRB, 2003), is one notable example. This was a list of guidelines that gave trainings a direction for the advancement of doctoral education. The development of this statement was through a blend of inputs from higher education stakeholders. These were not essentially valuing industrial contexts but did address a need for PhDs’ transition outside academia. From its seven points ranging from A to G, the point number G(3) of the statement mentioned 'Demonstrate an insight into the transferable nature of research skills to other work environments and the range of career opportunities within and outside academia.'. This point marks a budding interest in PhDs skills training with industrial contexts.

With changing times, Joint Skills Statement was replaced with the Researcher Development Framework or RDF (VITAE, 2012). Alike its predecessor, its purpose was the enhancement of academic careers of doctorates through their trainings. This reflects from its adopted methodology. It was a researched framework built with insights from higher education organisations and researchers, using surveys, interviews, and the contexts of phenomenology. The methodology also revealed transversal skills as a pillar in the RDF. The RDF acknowledged the value of developing reputation outside academics to build advocacy as an academic researcher. Overall, JSS and RDF’s motivation remained in the advancement of a researchers’ career. In contrast, the HIRES-PhD framework has focused on the finer details of this mission. HIRES-PhD framework is about skill development, limited to the transversal skills; and employment limited to industrial contexts. JSS and RDF had a broader focus in terms of skills and employment, the HIRES-PhD framework has amplified research efforts in its two finer aspects. However, both the JSS and RDF have catered to United Kingdom, whereas HIRES-PhD is not limited to a specific geographic region in its aim.

In the recent developments, the European Union has become active in funding projects that investigate industrial transversal skill requirements for PhD’s employability and training needs. The DocTalent4EU, OUTDOC, EURODOC and DocEnhance, mark few of the notable examples. The projects, adopting different methods, have been increasingly producing reports on the concerned topic. This is indicative of the urgency among policymakers to address this topic since reports are usually introduced to draw insights for a pressing issue.

A report on the Current and Future Skill Needs for the PhDs by Doctalent4EU approached the issue from multiple perspectives (Minea, 2023). It collected skills from live PhD job advertisements in February 2023, gathered feedback from higher education institutions and stakeholders from the non-academic sectors. The identified skills were mapped to an existing framework. This framework is a generally accepted one that encompasses different professions and abilities, known as ESCO (European Commission, 2020). The report in its final recommendation suggests a list of transversal skills that should be addressed for enhancing PhDs’ industrial employability. In simple terms, the skills were language mastery, working with digital devices and applications, working efficiently, proactive approach, positive attitude, willingness in learning, supporting and leading others.

A prior report, Research Report on PHD’s Skills and Competencies in Emerging Sectors by OUTDOC, also conducted surveys from 252 companies in European countries for identifying skills that improve the employability of PhDs (Držanič & Fišer, 2021). They found that the ‘training and professional skills of PhDs not being related to the company’, was the leading factor in the reasons for not employing PhDs. In their final list of recommended skills developed through survey, they enlist verbal communication, teamwork accountability, self-motivation, organisation, writing, problem-solving and decision-making, flexibility, result presentation to public and creativity.

The two above reports are distinct in their final recommendations for certain skills. For example, working with digital skills and language mastery (Minea, 2023), is not in the final recommendations of the report from the OUTDOC project (Držanič & Fišer, 2021). In fact, the report from OUTDOC eliminates foreign language skills from its final recommendations on its grounds of alignment towards hard skills. However, the two reports are representative examples of funded efforts that give an essential viewpoint of the current state of affairs. Unlike the HIRES-PhD framework which reflects the developed theoretical progress made over a panoptic timespan, the reports dwell into the most recent trends for fulfilling immediate gaps between the higher education initiatives and the industry expectations. They narrow down on select geographic regions pinpointing the latest challenges, in converse to the HIRES-PhD framework that systematically transforms exhaustive information, from different regions and time periods, for transforming it into levels of thematic knowledge with its best possible efforts in encapsulating the overall transversal skillsets.

Nonetheless, other reports also that draw information from the existing documents. The report Identifying Transferable Skills and Competences to Enhance Early-Career Researchers Employability and Competitiveness from EURODOC is one such example (Weber et al., 2018). It identifies various industry-relevant PhD transversal skills and tabulates them in different categories for their employability enhancement. The categories are career development, cognitive, communication, digital, enterprise, interpersonal, mobility, research, teaching, and supervision. These categorisations are not emerging themes from the collected data but adopted and modified from non-peer-reviewed sources. The report does not detail if the selected sources were the result of a systematic screening process with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, it mentions that they do not claim the work’s completeness.

Similarly, the report, Good Practice Recommendations for Integration of Transferable Skills Training in PhD Programmes by DocEnhance, probes the literature for answers (Bitušíková & Borseková, 2020). It also draws information from the project’s partners and several parallel projects. It appears that their literature search was agile and flexible avoiding rigidity. Its insight on transversal skills is a continuous monographic dialogue of information and intuitive suggestions on the recent practices in doctoral education and employment. The report is insightful in recommending a STAR format of organising one’s skills portfolio that enables reporting the situation where the skill was acquired, the tasks carried out, actions undertaken, and the results accomplished, serves as a tool for the PhDs to self-reflect. However, it leaves a gap in producing a thematically reduced corpus available further research developments by peers.

We observe that the framework, models, or other diagrammatic representations are a collection of transversal skills constructs. The identification of these constructs is being carried out through secondary and primary research methods. Each time a study investigates this topic through primary sources, it finds the most recent trends in the PhD transversal skills and employability training. In secondary sources, the identified constructs do not reflect the most recent trends but the constantly relevant aspects. For example, from the traditional models, like the USEM model of employability, the identified skills are rooted in the psychology and self-theories literature without any statement for its rationality.

Also, the traditional models were focusing on a broad set of students. Thus, frameworks like RDF fulfilled this gap. The RDF, adept for the PhDs’ academic career, stems its data of one thousand characteristics from interviews and literature reviews. This made a mix of primary and secondary sources. The levels in RDF are gradual reductions of these characteristics through clustering. A rigour in building the framework increases the user’s faith in it. Perhaps this had led to RDF’s popularity. An equivalent rigour is required in the development of framework for the PhD transversal skills in industrial employability contexts. Selecting the literature without a systematic screening like in the DocEnhance report (Bitušíková and Borseková, 2020) or acknowledging the incompleteness of a work as claimed in EURODOC’s report (Weber et al., 2018) brings doubts in the users’ mind. Moreover, adopting solely survey methods like from the report by OUTDOC (Držanič & Fišer, 2021), shall only reflect a present-day situation without the overall constant theoretical view on the subject. Additionally, mapping the specific PhD industrial transversal skills to a generalized framework (Minea, 2023; Weber et al., 2018), misses the key point to identify emerging themes from the core of the topic itself.

Therefore, the need for HIRES-PhD framework was identified. In the HIRES-PhD framework, we attempt to overcome such shortcomings. In the development of the framework, the studies from which the transversal skills had to be identified were screened in stages (title, abstract and full text), to ensure that it serves the purpose of the study and is related to doctoral education, doctoral training, and industrial employability. This ensured its adherence to the core topic of the study. Secondly, we identified the transversal skills, building a data, in a significant number of rows to identify the thematic patterns emerging from within them in two additional levels. The first level is the transversal skills with citations, the second level, are the sixteen codes emerging from it, and the third level, is a further thematic reduction of the sixteen codes into four themes. This contributed to our levels of the framework. As the levels are emerging from within the collected data, it transforms the singular information from the thirty-nine studies into reliable knowledge emerging from the core sources of the topic. With the development of HIRES-PhD framework, we realize that transversal skills are inter-dependent and it is best to focus on them holistically, especially for training purposes. When the framework is used for specific industrial occupations, there could be increased need for some transversal skills than others. The framework is a set of guidelines which can be used in these situations as indicatively and not exhaustively. Also, it is developed from the scientific literature, thus reliable in the contexts of doctorate training and hiring.

Conclusions and future implications

A transversal skills framework is a structured accumulation of abilities and behaviours that are important for workplace achievements. Similarly, HIRES-PhD framework is a scientific accumulation of researched insights to facilitate the industrial career accomplishment of doctorates. It is an indicative scaffolding under which transversal skillset developments are executed. This framework works like a guiding reference for doctorate human resource development. A transversal skills framework helps entities recognize their requirement of skills in various organisational roles. It serves a blueprint for training designs and recruitment efforts enabling employee success. It helps optimizing uniformity in the existing trends of employability and training practices. Likewise, the HIRES-PhD helps standardise transversal skill courses and provides a roadmap for its holistic design. The critically and systematically reviewed framework improves its reliability. HIRES-PhD is a focal point of knowledge from researched studies, making it important to possess this framework since it promotes the doctorate human resource development by its stakeholders. Also, post the training reception, the framework helps trainees self-reflect on their calibre. The framework is a medium for PhD career diversification outside academics. It contributes towards a sense of research and development in the world and helps build the knowledge society.

Where a transversal skills model concentrates on the process of specific inputs with expected outputs, a transversal skill framework like the HIRES-PhD provides an exhaustive set of guidelines that aligns with diverse roles and departments in an organisational setting. Transversal skills identification for every role can be executed through a mix of interviews, subject-matter experts, job analysis or stakeholder consultations. The skills can differ with varying roles within an organisation. Though each role has its unique mix of skillset requirements based on the needs of the specific job and culture, an overlap may exist in certain skills. Since the HIRES-PhD Framework is a converged reflection of the research literature insights, transformed into thematic knowledge, it provides user freedom in working with the skills more significant for a role, organization, or region concerned. Thus, the framework can be used exhaustively and exclusively.

The HIRES-PhD framework will prove beneficial in the process of doctorate recruitment for evaluating the competing candidate’s capabilities. In this study, we witness the automated testing of PhD transversal skills for industrial employment (Azzini et al., 2018). The scientifically researched framework of HIRES-PhD eliminates the need for the identification of a standard set of skills in such automation efforts. Through the alignment of themes highlighted in the framework, informed decisions can be undertaken in the organisational hiring judgements to affirm the best on-boarding. A transversal skills framework like the HIRES-PhD is not only a valuable tool for doctoral students but is significant for the doctorate human resource development. For industrial organizations that actively employ PhDs, the HIRES-PhD framework has the potential to be utilized in the identification of skill gaps, designing corporate trainings, and enabling customised mentoring for the enhancement of their transversal skills. Such a framework needs to be updated in regular intervals to secure its applicability with dynamic needs of the industrial environment. An annual review of such frameworks is recommended or whenever the need arises with the changing social and organisational needs. The HIRES-PhD transversal skills framework is mouldable for the reflection of exclusive needs in varied industries. There can be certain specific competencies that are applicable in diverse industrial settings, however organisations can customize the framework to inculcate the industry-aligned skills. For the implementation of a framework like the HIRES-PhD, organisations must initiate an exhaustive evaluation of their existing transversal skills. This enables them to implement the framework based on their findings and express it to their hired talent through awareness campaigns and skill-building efforts. Alongside, a continuing supervision and assessment hold value to ensure the effect of the framework’s implementation.

The current study is a theoretical contribution which opens the dialogue for further research discussion on this topic. It encourages a collective effort in shaping the transversal skills theory extracting information from the validated and peer-reviewed singular studies. Each of these studies are painstaking effort from various authors in this topic, and this study transforms it into knowledge base. We acknowledge the fact that this study is a starting point for further research development in PhD employability and transversal skills. Moreover, the framework can be further enhanced as the literature appears leaning towards the European contexts and transversal skills can vary across cultures. Future studies can also extend the framework with the identification of skills in other languages. Broadening the scope of this framework for other studentships will evolve its conceptualization. The underlying literature of this framework emerges from technocratic themes emphasizing the fulfilment of skill demands. Future studies can investigate skills that emerge from humanistic and emancipatory rationalities which focus on personal development and freedom (Hooley et al., 2022). Addition of skills from studies of such nature will broaden the underpinning database of the framework. Therefore, in addition to the practical implications, this study also draws social science researchers’ attention towards this topic through HIRES-PhD, a transversal skills framework for diversifying PhD employability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the CORA repository, https://doi.org/10.34810/data1276.

References

Acker S, Haque E (2017) Left out in the academic field: doctoral graduates deal with a decade of disappearing jobs. Can J High Educ 47(3):101–119. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v47i3.187951

Anastasiu L, Anastasiu A, Dumitran M et al. (2017) How to align the university curricula with the market demands by developing employability skills in the civil engineering sector. Educ Sci 7(3):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7030074

Atenas J, Havemann L, Priego E (2015) Open data as open educational resources: towards transversal skills and global citizenship. Open Prax 7(4):377–389. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.7.4.233

Azzini A et al. (2018) A Classifier to Identify Soft Skills in a Researcher Textual Description. In: Applications of Evolutionary Computation. 21st International Conference, EvoApplications 2018, Parma, April 2018. Springer, Cham, pp 538–546

Azzini A et al. (2019) Evolving Fuzzy Membership Functions for Soft Skills Assessment Optimization. In: Knowledge Management in Organizations. International Conference on Knowledge Management in Organizations, Zamora, July 2019. Springer, Cham, pp 74–84

Behle H (2020) Students’ and graduates’ employability: a framework to classify and measure employability gain. Policy. Rev High Educ 4(1):105–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2020.1712662

Bennett N, Dunne E, Carré C (1999) Patterns of core and generic skill provision in higher education. High Educ 37:71–93. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003451727126

Bitušíková A, Borseková K (2020) Good practice recommendations for integration of transferable skills training in PhD programmes. DocEnhance. Available via CORDIS. https://shorturl.at/9qyJa

Boffo V (2019) Employability and higher education: a category for the future. N Directions Adult Continuing Educ 163:11–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20338

Bologna Process (2005) Doctoral Programmes for the European Knowledge Society. In: European University Association. Available via EUA. https://shorturl.at/U7yk7

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caeiro-Rodriguez M, Manso-Vázquez M, Mikic-Fonte FA et al. (2021) Teaching soft skills in engineering education: an European perspective. IEEE Access 9:29222–29242. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3059516

Cinque M (2016) Lost in translation” soft skills development in European countries. Tuning J High Educ 3(2):389–427. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-3(2)-2016pp389-427

Clarke M (2018) Rethinking graduate employability: the role of capital, individual attributes and context. Stud High Educ 43(11):1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

Dāvidsone A, Seppel K, Telyčėnaitė A, Matkevičienė R, Uibu M, Silkāne V, Jurāne-Brēmane A, Allaje Õ (2021) Exploring students’ perceptions on acquisition of transversal skills during an online social simulation. Paper presented at the 79th international conference of University of Latvia, Human, Technologies and Quality of Education, 727–738. https://doi.org/10.22364/htqe.2021.58

Držanič IL, Fišer SZ (2021) Research report on PHD’s skills and competencies in emerging sectors. OUTDOC. Available via Erasmus+ Projects. https://outdoc.usal.es/outcomes

Edinova M (2020) The characteristics of PhD programs at Saint-Petersburg State University (SPSU): The transformation of generic competences of PhD students in political science. Tuning J High Educ 7(2):43–65. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-7(2)-2020pp43-65

European Commission (2020) ESCO Portal. https://esco.ec.europa.eu/en

Fabbri L, Romano A (2019) Engaging transformative organizational learning to promote employability. N Directions Adult Continuing Educ 163:53–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20341

Freitas A, Garcia P, Lopes H et al. (2018) Mind the gap: bridging the transversal and transferable skills chasm in a public engineering school. In: IEEE Xplore. 3rd International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), Aveiro, June 2018

Gu J, Levin JS, Luo Y (2017) Reproducing “academic successors” or cultivating “versatile experts”: influences of doctoral training on career expectations of Chinese PhD students. High Educ 76(3):427–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0218-x

Haug G, Tauch C (2002) Trends II—towards the European higher education area: survey of main reforms from Bologna to Prague. European University Association. Available via EUA. https://eua.eu/resources/publications/676:trends-ii-towards-the-

Hillage J, Pollard E (1998) Employability: developing a framework for policy analysis. Department for Education and Employment, London

Hnatkova E, Degtyarova I et al. (2022) Labour market perspectives for PhD graduates in Europe. Eur J Educ 57(3):395–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12514

Hooley T, Bennett D, Knight E (2022) Rationalities that underpin employability provision in higher education across eight countries. High Edu 86:1003–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00957-y

Huisman J, Weert ED, Bartelse J (2016) Academic careers from a European perspective. J High Educ 73(1):141–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2002.11777134

Icociu CV, Costoiu MC, Dobresu TG et al. (2019) Competences between labor market and higher education through ESCO. Inf Econ 23(4):89–100. https://doi.org/10.12948/issn14531305/23.4.2019.08

Isaacs AK (2015) Tuning tools and insights for modern competence-based third-cycle programs. In: Curaj A, Matei L, Pricopie R, Salmi J, Scott P (eds) The European Higher Education Area. Springer, Cham, pp 561–572

Kalaimani EVMR, Kirubakaran E, Anbalagan P (2015) Hypernym based feature selection for semi-structured web content classification. Int J Appl Eng Res 10(2):2609–2626

Kehm BM (2020) The past, present and future of doctoral education in Germany. In: Yudkevich M, Altbach PG, Wit HD (eds) Trends and Issues in Doctoral Education: A Global Perspective. SAGE Publications Pvt Ltd, Delhi, pp 79–102

Khaouja I, Mezzour G, Carley KM et al. (2019) Building a soft skill taxonomy from job openings. Soc Netw Anal Min 9:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-019-0583-9

Khasanzyanova A (2017) How volunteering helps students to develop soft skills. Int Rev Educ 63:363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-017-9645-2

Kismihók G, McCashin D, Mol ST (2022) The well-being and mental health of doctoral candidates. Eur J Educ 57(3):410–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12519

Knight PT, Yorke M (2002) Employability through the curriculum. Tert Educ Manag 8:261–276. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021222629067

Kwiek M (2021) Poland: an abundance of doctoral students but a scarcity of doctorates. In: Yudkevich M, Altbach PG, Wit HD (eds) Trends and Issues in Doctoral Education: A Global Perspective. SAGE Publications Pvt Ltd, Delhi, pp 103–126

Law B, Watts AG (1977) Schools, careers, and community: a study of some approaches to careers education in schools. Church Information Office, London

Ma Y, Bennett D (2024) Analyzing predictors of perceived graduate employability from sufficiency and necessity perspectives. High Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01221-1

Ma Y, Chen SC (2024) Understanding the determinants and consequences of perceived employability in graduate labor market in China. Int J Educ Vocat Gui 24:435–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09567-7

Mainert J, Kretzschmar A, Neubert JC et al. (2015) Linking complex problem solving and general. Int J Lifelong Educ 34(4):393–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2015.1063482

Malik A, Setiawan A (2015) The development of higher order thinking laboratory to improve transferable skills of students. In: Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Innovation in Engineering and Vocational Education, Bandung, November 2015. Atlantis Press, pp 36–40. https://doi.org/10.2991/icieve-15.2016.9

Mariani P, Zenga M, Marletta A (2020) Applying conjoint analysis to the labour market: analyzing the position of ICT assistant in the Italian Electus project. Statistica Applicata 32(1):29–39. https://doi.org/10.26398/IJAS.0032-003

Marrara S, Azzini A, Cortesi N (2021) A language model-based approach for candidates with PhD profiling in a recruiting. Int J Web Eng Technol 15(4):407–436. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWET.2020.114031

Martins H, Freitas A, Direito I et al (2021) Engineering the future: transversal skills in engineering doctoral education. In: 4th International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), Lisbon, 2021. IEEE Xplore. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISPEE47794.2021.9507210

McCash P (2006) We’re all career researchers now: breaking open career education and DOTS. Brit J Guid Couns 34(4):429–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880600942558

Medina A, Hernández JC, Muñoz-Cerón E et al. (2020) Identification of educational models that encourage business participation in higher education institutions. Sustainability 12(20):2–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208421

Melacarne C, Nicolaides A (2019) Developing professional capability: growing capacity and competencies to meet complex workplace demands. N Directions Adult Continuing Educ 163:37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20340

Minea AA (2023) Report on current and future needs for transferable skills. DocTalent4EU. Available via ZENODO. https://zenodo.org/records/10853414

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691773384

Olo D, Correia L (2022) How to develop higher education curricula towards employability? A multi-stakeholder approach. Educ + Train 64(1):89–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-10-2020-0329

Orazbayeva B, Van der Sijde P, Baaken T (2019) Autonomy, competence and relatedness—the facilitators of academic engagement in education-driven university-business cooperation. Stud High Educ 46(7):1406–1420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1679764

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Pardo-Garcia C, Barac M (2020) Promoting employability in higher education: a case study on boosting entrepreneurship skills. Sustainability 12(10):4004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104004

Picard C, Hardebolle C, Tormey R (2021) Which professional skills do students learn in engineering team-based projects? Eur J Eng Educ 47(2):314–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2021.1920890

Pisoni G, Renouard F (2019) Integrating online education in Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E) Doctoral training program. In: 17th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Smokovec, 2019. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETA48886.2019.9040144

Pisoni G, Renouard F, Segovia J et al. (2020) Design of small private online courses (SPOCs) for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E) Doctoral-level education. In: 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, 2020. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON45650.2020.9125153

Pool LD, Sewell P (2007) The key to employability: developing a practical model of graduate employability. Educ + Train 49(4):277–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710754435

Poyatos Matas C (2012) Doctoral education and skills development: an international perspective. REDU 10(2):163–191. https://doi.org/10.4995/redu.2012.6102

Research Councils/AHRB (2003) Improving standards in postgraduate research degree programmes. In: The National Archives. Available via The National Archives. https://n9.cl/mcd01

Ritchie J, Spencer L (1994) Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: A Bryman, & B Burgess, (eds) Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge, London, pp 173–194

Rodrigues JC, Freitas A, Garcia P et al. (2018) Transversal and transferable skills training for engineering PhD/doctoral candidates. In: IEEE Xplore. 3rd International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), Aveiro, June 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISPEE.2018.8593472

Römgens I, Scoupe R, Beausaert S (2020) Unravelling the concept of employability, bringing together research on employability in higher education and the workplace. Stud High Educ 45(12):2588–2603. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1623770

Rossano S, Meerman A, Kesting T et al. (2016) The relevance of problem-based learning for policy development in university-business cooperation. Eur J Educ 51(1):40–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12165

Santos P (2021) Public policies for university–business collaboration in Portugal: an analysis centred on doctoral education. Port J Soc Sci 20:65–86. https://doi.org/10.1386/pjss_00034_1

Santos P, Veloso L, Urze P (2020) Students matter: the role of doctoral students in university–industry collaborations. High Educ Res Dev 40(7):1530–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1814702

Schwabe M (2011) The career paths of doctoral graduates in Austria. Eur J Educ 46(1):153–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01465.x

Shackleton J, Messenger S (2021) The WorldSkills response to transversal skills. J Supranatl Policies Educ 13:168–190. https://doi.org/10.15366/jospoe2021.13.008

Shomotova A, Ibrahim A (2024) Higher education student engagement, leadership potential, and self-perceived employability in the United Arab Emirates. Stud High Educ: 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2367155

Small L, Shacklock K, Marchant T (2017) Employability: a contemporary review for higher education stakeholders. J Vocat Educ Train 70(1):148–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2017.1394355

Smith K, Williams D, Yasin N et al. (2014) Enterprise skills and training needs of postgraduate research students. Educ + Train 56(8/9):745–763. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2014-0052

Suleman F, Videira P, Araújo E (2021) Higher education and employability skills: barriers and facilitators of employer engagement at local level. Educ Sci 11(2):2–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11020051

Sultana RG (2014) Rousseau’s chains: striving for greater social justice through emancipatory career guidance. J Nat Ins Car Educ Couns 33:15–23. https://doi.org/10.20856/jnicec.3303

Sunagar P, Kanavalli A, Shweta S (2020) A survey report on hypernym techniques for text classification. In: 2020 Fifth International Conference on Research in Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (ICRCICN), Bangalore, India, pp 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRCICN50933.2020.9296159

Terzaroli C (2019) Entrepreneurship as a special pathway for employability. N Directions Adult Continuing Educ 163:121–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20346

VITAE (2012) Vitae Researcher Development Framework and Researcher Development Statement: methodology and validation report. In: VITAE Realising the Potential of Researchers. Available via VITAE. https://www.vitae.ac.uk

Vittorio N (2015) European Doctoral Programs in Light of EHEA and ERA. In: A Curaj, L Matei, R Pricopie, J Salmi, & P Scott (eds) The European Higher Education Area. Springer, Cham, pp 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_35

Weber CT, Borit M, Canolle F (2018) Identifying transferable skills and competences to enhance early-career researchers employability and competitiveness. EURODOC. Available via ZENODO. https://zenodo.org/records/1299178

Western M, Boreham P, Kubler M et al. (2007) PhD graduates 5 to 7 years out: employment outcomes, job attributes and the quality of research training. Available via The University of Queensland Social Research Centre. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:177864

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 945413 and from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV). Disclaimer: This work reflects only the author’s view and the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the study conception, design and writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions