Abstract

Due to their significant environmental impact, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are critical in improving a green economy. This research examines the influence of firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure on the green orientation of SME senior management. Utilizing a sample of CEOs and owner-managers from 489 Chinese SMEs, data accumulated from October 2023 to March 2024 were analyzed using structural equation modeling. The outcomes confirm the significant impact of firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure on senior management’s green orientation, which, in turn, improves SME outcomes. In addition, senior management’s green orientation partially intermediates the influence of firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure on SME outcomes. Stakeholder pressure further moderates the link between the senior management’s green orientation and SME outcomes, indicating the importance of external pressures in adopting strategic green orientations. These results support the resource-based view, stakeholder theory, and upper-echelon theory, offering practical guidance for businesses seeking to incorporate green strategies into their fundamental operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, organizations have faced growing pressure to implement sustainability initiatives in response to climate change, limited resources, and evolving buyer preferences. According to the 2023 Buying Green Report, which surveyed over 9000 consumers across Europe, North America, and South America, 82% expressed a readiness to pay more for sustainable packaging since 2021 (Trivium Packaging, 2023). Similarly, in 2019, 58% of United States buyers across age groups indicated a willingness to make extra payments for sustainable products (Petro, 2022). Generation X’s commitment to sustainability has shown strong growth, as 90% are ready to pay at least 10% extra for sustainable goods (Petro, 2022).

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play an essential role in the sustainability of an economy due to their substantial environmental impact (Casidy et al., 2024). SMEs represent 99% of all business entities and generate 60% of jobs, yet they contribute 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions (OECD, 2023). In China, SMEs are responsible for approximately 80% of the hazardous chemical incidents from 2000 to 2006 and 53% of CO2 emissions in 2010 (Chen et al., 2022). Responding to these effects, numerous SMEs have recently adopted green strategies and implemented eco-friendly practices to minimize their ecological impact (Sun et al., 2022; Waqas et al., 2021).

Despite the positive trends, research has revealed that numerous SMEs participate in greenwashing; they brand themselves as “green” without making meaningful changes (Yao et al., 2024; Zhang, 2022). While earlier studies have focused on external motivators for SMEs adopting green strategies, such as external pressures and regulatory demands (Cantele & Zardini, 2020; Tyler et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), they have not fully addressed the internal dynamics. For example, Cantele and Zardini (2020) analyzed 3,533 Italian SMEs and identified internal and external pressure, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers to implementing sustainability practices. Tyler et al. (2023) explored the wine sector in Denmark, France, Italy, and the United States, identifying that organizational proactive orientation and regulatory pressure were significant factors for 286 SMEs. Wang et al. (2023) identified 14 drivers of sustainability in Pakistani SMEs, highlighting organizational commitment and external support. However, despite the recent progress, earlier research has failed to capture the internal dynamics of SMEs, particularly the influence of chief executive officers and senior management on green orientation (Casidy et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023).

The present research seeks to fill this void by exploring firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation as significant motivators of green practices and performance among SMEs. Specifically, we examine how the firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation impact senior management’s green orientation and, subsequently, overall organizational performance. Our contribution is to achieve better integration between external pressures and internal motivations necessary for a comprehensive understanding of how SMEs can effectively meet sustainability challenges.

Firm environmental ethics represents a firm’s ethical beliefs, norms, and values regarding environmental issues. Extensive research indicated that involving ethical standards in organizational culture improves a unique and valuable green mindset and equips firms with essential resources and capabilities (Guo et al., 2020; Waheed & Zhang, 2022). Such ethical commitments enable organizations to benefit from being first movers through sustainable innovation and new market opportunities (Aftab et al., 2022). Senior management guided by these ethical values can better integrate sustainability into core business strategies, improving regulatory compliance, operational efficiency, and market positioning (Menguc et al., 2010). An organization that incorporates environmental ethics can enhance its brand reputation, cultivate trust among consumers, and establish a competitive edge (Chang, 2011), all of which are essential for sustained success (Aftab et al., 2022; Dudley, 2007; Jing Xie et al., 2024). The adherence to robust environmental ethics by senior managers is essential as it enables the effective implementation of green practices that lead to notable improvements in business operations (Li et al., 2024; Mahran & Elamer, 2024). In this context, our research emphasizes the relationship of firm environmental ethics with SMEs’ senior management’s green orientation and performance in the Chinese context.

Given that over 85% of people worldwide affiliate themselves with a faith system (Waseerman, 2024), it is likely that SME senior managers hold spiritual beliefs that influence their decision-making processes (Casidy et al., 2024). Earlier scholars have demonstrated a notable link between spiritual orientation and sustainable buying behaviors (Alotaibi and Abbas, 2023; Minton et al., 2015; Orellano et al., 2020). Spiritual beliefs often intersect with political ideology, influencing attitudes and behaviors toward socio-economic (Al Fozaie, 2023) and environmental issues (Naiman et al., 2023). For instance, Bjork-James (2023) found that the apocalyptic view among United States evangelicals often led to diminished interest in environmental issues. Lockwood (2018) noted that Republican Evangelical Protestants were more skeptical about climate change compared to their Democratic counterparts. Considering these observations, our research raises two critical questions: Does the spiritual orientation of SME senior managers or owners affect the degree to which their organization adopts a strategic green orientation? How does spiritual orientation intersect with one’s political identity to impact the adoption of strategic environmental orientation? This research explores these questions in the Chinese context.

The Chinese context is essential because of its unique blend of cultural and spiritual influences. Confucianism emphasizes harmony, the collective good, and respect for authority, improving a holistic approach to business (Xu and Wang, 2024). The intense interest in relationships or guanxi and community-oriented values differ from the individualistic focus in the United States (Weiss et al., 2021) and other countries, including Australia and Malaysia (Noordin et al., 2002). These Chinese spiritual values encourage long-term thinking and investment in environmental and social responsibilities (Su et al., 2023). The specific features of Chinese organizations’ internal dynamics and strategic approaches formed by their spiritual and cultural values require detailed investigations.

External pressures, such as those from employees, the local community, regulators, and investors, also play an essential role in forming businesses’ sustainability-related strategies (Adomako & Tran, 2022; Papadas et al., 2019). It has been shown to moderate the link between sustainable activities and SME results (Agyapong et al., 2023; Baah et al., 2021). For instance, institutional pressures can drive strategic decisions that improve organizational legitimacy and success (Adomako et al., 2023). The involvement of stakeholder pressure in the SME’s strategic management has gone outstanding, and SME outcomes are immense, as it describes how these firms would overcome challenges or exploit opportunities existing within an environment that is constantly changing at a rapid pace (Tyler et al., 2024). By closely exploring these dynamics, this research underscores how stakeholder engagement drives innovation, improves competitive advantage, and encourages sustainable practices in SMEs (Alshukri et al., 2024).

Considering the above-identified gaps, we aimed to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

How do firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure influence senior management’s green orientation in Chinese SMEs?

-

2.

How do firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure interact with senior management’s green orientation to influence the performance of Chinese SMEs?

-

3.

What is the moderating effect of stakeholder pressures on the relationship between the senior management’s green orientation–and the performance of Chinese SMEs?

We apply the “upper-echelon theory” of Hambrick and Mason (1984), which holds that senior management characteristics, experiences, and values form strategic choices (Hiebl, 2014) and affect organizational performance (Dhir et al., 2023). This theory indicates that the backgrounds and beliefs of senior management influence strategic choices as to how firms respond to stakeholder pressures and the changing market environment (Kim, 2022; Wiengarten et al., 2017). Additionally, this theory is complemented by the resource-based view theory of Barney (1991), which proposes that distinctive capabilities and resources, including intangible assets such as firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation, have the potential to confer a competitive edge (Chang, 2011; Singh et al., 2019; Tracey, 2012). Moreover, this study integrates aspects of the stakeholder theory of Freeman (1999), which emphasize the significance of aligning with the expectations and demands of stakeholders (Guo and Wang, 2022). By integrating these theoretical perspectives, this research offers a deeper insight into how values and beliefs at the top management shape environmental strategies and emphasize leadership in effecting sustainability (Eisenhardt and Martin, 2000; Singh et al., 2019).

Literature review hypothesis formulation

Theoretical foundation for the study proposed model

This study proposed a model driven by the integration of the upper-echelon theory of Hambrick and Mason (1984), the stakeholder theory of Freeman (1999), and the resource-based view of Barney (1991) that explain how the internal characteristics and external links of firms influence the outcomes of enterprises. The upper echelons theory postulates that the traits and values of senior management affect enterprise outcomes through the perceptions and strategies induced in them (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). This describes how strategic decisions by senior management’s green orientation profoundly impact SME performance (Li et al., 2024; Xu, 2023), driven by their commitment to firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation (Iguchi et al., 2022; Madrid-Guijarro and Duréndez, 2024). These cognitive bases and senior management’s green orientation represent the only filters through which strategic decisions align business practices with sustainability objectives (Mahran and Elamer, 2024; Xu, 2023).

This is further complemented by stakeholder theory and the resource-based view concerning the roles of external pressures and internal capabilities. According to the theory of stakeholders, an enterprise has to deal with all kinds of stakeholders to be successful in the long run with environmental impacts (Seroka-Stolka, 2023; Jing Xie et al., 2024). This theory supports the moderation effect of stakeholder pressure in the model. It underlines how reshaping corporate strategies by external demands may shift toward sustainable outcomes (Guo and Wang, 2022). Resource-based view theory also holds that enterprises can achieve a competitive advantage from distinctive resources, including high alignment with firm environmental ethics (Baah et al., 2024) and spiritual orientation (Rezapouraghdam et al., 2019) which are inimitable, rare, and non-substitutable and valuable. Resources have, therefore, become a path for SMEs to implement and maintain green strategies for improved results.

Effects of firm environmental ethics

Firm environmental ethics is “the firm’s fundamental ethical attitude, belief, and mindset about the environmental aspect” (Wu et al., 2022, p. 4). It represents an organization’s commitment to sustainability values, impacting decision-making, and enhancing a culture related to sustainability (Wu et al., 2022). The upper-echelon theory highlights how senior management’s personal values or spiritual beliefs drive strategic decisions, specifically when ethical values are integrated with an SME’s culture (Casidy et al., 2024; Jun Xie et al., 2023). Prior research showed that firm environmental ethics influences several sustainability initiatives, including eco-efficiency, green leadership, green marketing, and proactive environmental strategies (Dragomir, 2020; Han et al., 2019). Ethical values, combined with strategic objectives, enable the integration of firm environmental ethics into business practices for better SME performance (Baah et al., 2024).

The theory of the resource-based view supports that intangible resources like firm environmental ethics act as an integral component in sustaining a competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Dubey et al., 2019). Within the organizational culture framework, firm environmental ethics are a critical element that underscores environmental concerns and sustainability (Singh et al., 2019). Studies have demonstrated the essentiality of environmental ethics for SME outcomes in the manufacturing sector (Aftab et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019) and its significant impact on strategic outcomes, such as financial outcomes and market positioning (Baah et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2020). Following this, we hypothesize that.

H1a: Senior management’s green orientation is significantly influenced by firm environmental ethics.

H1b: SME outcomes are significantly influenced by firm environmental ethics.

Effects of spiritual orientation

Psychologically, spirituality manifests through observable elements such as spiritual practices, behaviors motivated by spirituality, and spiritual thinking (Sargeant & Yoxall, 2023). A comprehensive understanding of spirituality includes traits applicable to all individuals, regardless of their religious affiliations (Krok, 2008). Spiritual orientation is defined as an individual’s association, identification, and connection with specific beliefs, practices, and rituals, which provide meaning, purpose, and direction to their life (Hill et al., 2000). It inculcates spiritual and ethical values into business practice (Carr, 2018) to create a sense of purpose and environmental stewardship through practices and beliefs (Margaça et al., 2022; Rezapouraghdam et al., 2019). Recent studies also considered the influence of spirituality on companies’ decision-making processes (Casidy et al., 2024). The idea is based on Cannella’s (2001) upper-echelon theory, which says that personal individual values and traits of the senior influence strategic decisions in the enterprise (e.g., Astrachan et al. (2020) and Cebula and Rossi (2021)). This theoretical perspective is further reinforced by findings that indicate spiritual orientation may elicit sustainable results by developing commitment among managers toward the practice of environmental concerns (Alotaibi and Abbas, 2023; Iguchi et al., 2022; Orellano et al., 2020; Tsendsuren et al., 2021).

More recently, Casidy et al. (2024) found that top executives’ spiritual orientation correlates positively with strategic green marketing orientation among SMEs in the United States. Studies also evidenced that enterprises integrating spiritual orientation into their business practices show a more profound commitment to ethical behavior and social responsibility, which leads to enhanced firm image and financial or sustainable outcomes (Kennedy and Lawton, 1998; Zahari et al., 2024). However, research by Mutmainah and Apriliantika (2023) found an insignificant correlation between spiritual orientation and firm performance. Based on the above discussions and inconsistent results, we hypothesize that.

H2a: The senior management’s green orientation is significantly influenced by spiritual orientation.

H2b: SME outcomes are significantly influenced by spiritual orientation.

Effects of senior management’s green orientation

The strategic orientation concept has roots in the resource theory, which postulates that it comprises a combination of intangible capabilities and resources integral to a firm’s culture (Khizar et al., 2023). It consists of a firm’s strategic direction to foster behaviors that assure sustained firm performance and competitive market position (Reyes-Gómez et al., 2024). While many types of strategic orientations exist, including entrepreneurial, environmental, learning, market, and technology orientations (Nugroho et al., 2022; Reyes-Gómez et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2021), few have examined senior management’s green orientation (Adomako et al., 2021). In this context, the senior management’s green orientation refers to how senior managers address sustainability through activities that involve green supply chain management, energy efficiency, waste reduction, eco-friendly innovation, and green HR practices.

Peng et al. (2024) recently emphasized how strategic human resources management shapes eco-innovation and sustainability outcomes. Xu (2023) identified the positive influence of prior experience by CEOs on corporate social responsibility outcomes within China. Empirical evidence has, therefore, so far shown a positive connection between the variants of strategic orientation and SME outcomes (Hakovirta et al., 2023; Khizar et al., 2023; Nugroho et al., 2022; Reyes-Gómez et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2021). However, only a handful of empirical studies have explored strategic environmental orientation in relation to the performance of SMEs. Such as Hong et al. (2009) detected its significant impact on SME outcomes within the context of manufacturing firms, while Shaukat and Ming (2022) studied both direct and indirect influence in Pakistan’s industrial companies. Other regional studies have sought to study green marketing orientation, including, among many, those of Khan et al. (2020) on Bangladeshi SMEs and Choudhury et al. (2019) on Indian SMEs, considering limitations such as the type of participants or sector-specific contexts. Therefore, we hypothesize that.

H3a: SME outcomes are significantly influenced by the senior management’s green orientation.

Although some studies explored the direct effect of spiritual orientation (Casidy et al., 2024; Iguchi et al., 2022) and firm environmental ethics (Han et al., 2019; Douglas Schuler et al., 2017) on senior management’s green orientation, its mediating role is yet to be studied. The spiritual orientation of senior managers promotes values that highlight responsibility and stewardship for environmental sustainability (Cui et al., 2015). This could be a religion-based but ethically driven perspective that may urge managers to embrace and implement a strategic environmental orientation that prioritizes environmental protection and sustainability in the strategies and operations of a firm (Albursan et al., 2016). As expected, such a strategic orientation was argued to promote firm performance through cost reduction by resource use efficiency and by improving firm reputation among environmentally sensitive consumers.

Furthermore, firm environmental ethics motivates senior managers to include environmental issues in pricing policies, leading to differential pricing for eco-friendly products (Elfenbein & McManus, 2010). Dedicated top management comments towards environmental issues tend to enhance green distribution networks, hence improving coordination with stakeholders (Yen, 2018). In addition, companies with high corporate social responsibility levels, especially regarding environmental ethics, attract favorable media attention (Cahan et al., 2015). Simultaneously, through green product initiatives, companies design their products and packaging with environmental considerations and implement eco-friendly production techniques (Dangelico and Pujari, 2010). Additionally, by engaging in green distribution programs, companies collaborate with suppliers and distributors to effectively meet their environmental objectives (Godfrey et al., 2009). Moreover, ecological ethics ensures that the chief executive officers adopt green strategies for waste reduction and energy efficiency. It enhances compliance, fosters innovation, and meets the market demand for greening (Han et al., 2019).

Among the other studies that have looked at strategic orientation as a mediating factor, Carvalho et al. (2016) established mediation between environmental dimensions and SME outcomes in the hotel sector in Brazil. Similarly, Coşkun et al. (2017) established that ecological orientation intermediates the link between psychological traits and purchase intentions among Turkish consumers. Han et al. (2019) found that green marketing intermediates the link between firm environmental ethics and outcomes in industrial firms in China. However, how senior management’s green orientation mediates the relationships between spiritual orientation, firm environmental ethics, and SME outcomes remains uncharted. Therefore, we hypothesize that.

H3b: The senior management’s green orientation significantly mediates the relationship between firm environmental ethics and SME outcomes.

H3c: The senior management’s green orientation significantly mediates the relationship between spiritual orientation and SME outcomes.

H3d: The senior management’s green orientation significantly mediates the relationship between stakeholder pressure and SME outcomes.

Effects of stakeholder pressure

Stakeholder pressure refers to the “influence stakeholders have over a firm’s decisions” (Singh et al., 2022, p. 504), and this pressure has become a significant force driving sustainability practices (Hoştut et al., 2023). Available literature identifies this factor to be important for those firms that adopt such green strategies as GHRM (Marrucci et al., 2023; Shah et al., 2024), green marketing (Chung, 2020), and supply chain management (Awan et al., 2017; Yen, 2018).

Recent studies have also emphasized the moderating effect of stakeholder pressure in different relationships. For example, Shahzad et al. (2023) examined its impact on the link between organizational motives and green management practices. Guo and Wang (2022) investigated its influence on the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurial orientation and firm environmental innovation. Seroka-Stolka (2023) studied its impact on the link between ecological strategy choice and the environmental performance of the organization. Appiah-Kubi (2024) analyzed its role in perceived benefit and SME sustainability reporting in Ghana. However, how stakeholder pressure improves the effect of senior management’s green orientation on enterprise outcomes remains less explored and requires empirical support in the context of Chinese companies. Therefore, we hypothesize that.

H4a: The senior management’s green orientation is significantly influenced by stakeholder pressure.

H4b: SME outcomes are significantly influenced by stakeholder pressure.

H4c: Stakeholder pressure moderates the effect of the senior management’s green orientation on firm performance.

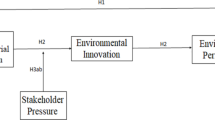

Figure 1 visually depicts the hypothesized relationships; it employs black arrows to illustrate direct connections, a blue dotted line indicates the mediating influence of the senior management’s green orientation, and an orange represents the moderation of stakeholder pressures.

Material and methods

Research context

We chose China as the setting for our research, recognizing it as the fastest-growing, largest, and most dynamic developing economy worldwide. This selection was informed by China’s institutional similarities to other developing markets, which comprises significant constraints on primarily intangible resources essential for SMEs to achieve an edge and better performance. Additionally, SMEs are indispensable to maintaining economic vitality and promoting innovation and entrepreneurship in China (Yang and Lu, 2024). Notably, SMEs represent 99% of businesses in China (Qalati et al., 2024) and account for 50% of the country’s tax revenue, 60% of its GDP, 70% of technological advancement, 80% of urban employment (OECD, 2024), and 68% of export trade (Qalati et al., 2024).

Despite this, manufacturing enterprises also pose significant challenges. Globally, account for about 70% of industrial pollution (Mady et al., 2023), with 50% in the Asia-Pacific, 70% in the European Union (Madrid-Guijarro & Duréndez, 2024), and 65% in China, of which 38% is contributed by industrial SMEs (Meng et al., 2018). In addition, 36% of adverse health effects and 41% of crop damage in China are caused by pollution from the manufacturing sector (Qalati et al., 2023). Moreover, manufacturing SMEs are responsible for 35% of the country’s heat-trapping emissionsFootnote 1. As such, the present research focuses on SMEs, which present a two-edged sword: they are essential to China’s value-added economic processes, yet they significantly contribute to environmental pollution (Chen et al., 2022).

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, SMEs are defined as companies with fewer than 1,000 employees and annual revenues not exceeding ¥400 million (Lu et al., 2021). The present investigation focuses on manufacturing SMEs in the sub-sectors of cement, chemical, refineries, steel, and textile, as they account for 61.6% of the country’s emissions and are responsible for high resource consumption, including 56% of energy consumption (Qalati et al., 2024; Shandalow et al., 2022).

Research sampling

In this cross-sectional study, a purposive sampling technique was used targeting CEOs and owner-managers, as prior studies have established the accuracy and reliability of data provided by top managers (Khan et al., 2019). This sampling is advantageous because purposive sampling enables the researcher to select participants with characteristics relevant to the study, like CEOs or owner-managers of SMEs (Chakabva and Tengeh, 2023). Targeting responding persons with the authority and knowledge to provide insightful data improves data quality and relevance (Etikan et al., 2016). Further, this sampling minimizes variability by focusing on a defined group (Tongco, 2007); hence, the findings would more likely apply to the specific context of SMEs in the dynamic market environment of China, leading to more robust conclusions.

The required sample size for the study was estimated to be 340 responses, based on the rule of 10, which recommends that for each variable item, at least ten responses should be considered (Kline, 2015). Kline’s (2015) approach holds that the sample would be large enough to ensure the results are reliable and generalizable, increasing the statistical power of analysis. To this end, this study has followed this guide to reduce the model’s overfitting risks and ensure sufficient robustness findings that enable meaningful interpretation and conclusion related to the proposed relationships. A larger sample size can, therefore, account for the non-response bias and represent a greater diversity of opinion, which may be usually seen in the case of manufacturing SMEs in China, given that various factors are associated with strategic decisions affecting sustainability practices.

Data collection process

Initially written in English, two professors at Jiangsu University translated the questionnaire into Chinese and then carefully retranslated it into English to ensure accuracy and avoid translation errors. A pilot test with feedback from 15 senior managers of Chinese SMEs led to further refinements and the finalization of the questionnaire. The participants were guaranteed anonymity and the confidentiality of their survey answers. They were also made aware that their involvement in the study was entirely at their discretion and that they were free to discontinue their participation at any point without any consequences.

We issued invitations to 1500 SMEs in the manufacturing sector and encouraged participation through follow-up calls and reminder emails. Data collection was strategically divided into three two-month stages from October 2023 to March 2024 to alleviate bias issues (Podsakoff et al., 2003) with separate stages for independent, mediator, moderator, and dependent constructs. In the first stage, we approached participants to record their responses for the independent construct firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation. Out of 1500 questionnaires distributed, we received 1139 valid responses. In the second stage, we called the 1139 to accumulate their reactions for the mediator–senior management’s green orientation and the moderator–stakeholder pressure, resulting in 782 valid responses. In the last stage, we contacted the 782 participants to submit their responses for dependent construct–SMEs outcomes, resulting in 489 valid responses and a 62.5% response rate.

Table 1 shows that 64.2% of the individuals are male and 35.8% are female. Considering the age of the organizations, 31.9% are less than one year old, 35.8% are in the range of 1 to 5 years, and 32.3% are older than five years. CEOs and owners are almost equally represented in job roles, making up 38.8% and 35.4% of the sample. Lastly, the majority of the SMEs, 39.3%, had less than 50 employees (see Table 1).

To assess nonresponse bias, our research assesses early and late individuals within the final sample based on the assumption that late responses might resemble non-responses (Adomako & Tran, 2022). The study found no changes between early and late participants considering the firm age, indicating that non-response bias does not pose a significant threat to our findings.

Instruments

In the present study, all scale items were sourced from existing research to measure the variable of interest, ensuring the instruments’ reliability and validity. We assessed spiritual orientation using the scale from Case and Chavez’s (2017) study, with a sample item being, “My spiritual beliefs inspire me to promote environmental sustainability.” Items to measure firm environmental ethics were adapted from Guo et al. (2020), with a sample item: “Our organization has integrated its environmental plan, vision, or mission into the company’s culture.” The senior management’s green orientation scale items were adapted from Casidy et al. (2024), exemplified by the item, “We make efforts to use renewable energy sources for our products/services.” Our research adapted scale items of Adomako and Tran (2022) to measure stakeholder pressure, with a sample item “Government/regulators put pressure on our company to pursue sustainable environmental practices.” Firm performance was assessed using an adapted seven-item scale from the work of Adomako and Tran (2022) and Choi and Hwang (2015). A sample item includes “Decreased CO2 emissions, wastewater, and energy consumption.” All the items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, where one indicates “strongly disagree” and five represents “strongly agree.” All the scale items are available in Appendix A, which is attached as a supplementary file.

Data analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to confirm the theoretical model by two different analysis methods: “covariance-based” and “variance-based.” In the current study, the variance-based partial least square SEM method was adopted, and Smart PLS 4.1 software was utilized to evaluate our hypothetical model. Hair et al. (2019) recommend using partial least square SEM under certain conditions. It suits testing theoretical frameworks oriented towards prediction, as is our goal in exploring firm performance. It also efficiently examines complex structural models comprising various variables, indicators, or model links (Abid et al., 2024). This model contains five constructs, which are independent, dependent, mediator, and moderator variables based on suggestions by Thakur et al. (2024) suggestions.

We also used partial least square SEM because of the following reasons recorded by Hair et al. (2021). Firstly, it allows formative and reflective variables without the rigid constraints for model identification imposed by CB-SEM. Secondly, it offers an advantage in instances where a study’s objective is to predict results or when facing convoluted structural frameworks. Third, it takes a clear position on the issue of how measurement variables are composites reflecting theoretical constructs while being pragmatic about the reality of measurement errors. Fourth, the method of partial least squares SEM is more suited to exploratory studies because of its flexibility and relatively fewer constraining assumptions on the intrinsic distribution of data and the measurement scales. Lastly, techniques of partial least squares SEM for modeling reduce the impact of metrological uncertainty compared to CB-SEM. Partial least square SEM requires assessment for the measurement and structural model (Kock, 2019).

Analysis of results

Assessment of measurement model

The competency of this proposed framework is assessed using convergent validity, which is determined through metrics such as average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (CA), and factor loadings. In addition, the discriminant validity is assessed using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) metrices. Table 2 presents the outcomes for matrices in which values of AVE were retained at>0.50 and CR, CA, and item loading were retained at>0.70 (Hair et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2022). These values reflect that the model has strong reliability and validity (Tran and Leirvik, 2020).

Table 3 results confirmed discriminant validity by verifying that all HTMT values do not exceed the 0.90 threshold. Based on this evaluation, the measurement model has successfully validated both convergent and discriminant validity, making it suitable for progressing to the next phase, which involves deriving a structural model.

Structural model

The typical evaluation metrics for this model encompass the coefficient of determination (R2), path significance, its effect sizes (f²), and an extra metric known as cross-validated redundancy (Q2). Before evaluating the model, it was suggested that multicollinearity be checked by exploring the VIF. According to Table 2, all VIF values were retained <3.33, signifying no issue of multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2021).

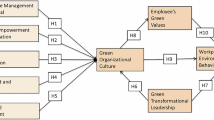

The findings from the path analysis are displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 2. The results show that FEE is significantly associated with SMGO (H1a: βdirect = 0.282 and t = 7.366) and SME outcomes (H1b: βdirect = 0.267 and t = 10.724). Similarly, SORI is significantly connected with the SMGO (H2a: βdirect = 0.391 and t = 11.250) and SME outcomes (H2b: βdirect = 0.215 and t = 10.591). The study also observed a significant link between SMGO and SME outcomes (H3a: βdirect = 0.524 and t = 27.958). Moreover, our work also observed a substantial impact of stakeholder pressure SMGO (H4a: βdirect = 0.305 and t = 10.634) and SME outcomes (H4b: βdirect = 0.131 and t = 5.739). The present research assessed the path using a 90% confidence interval. Table 4 shows that the confidence intervals for all hypotheses contain zero between the “5% and 95%” intervals, suggesting support hypothesis. Consequently, the results accepted all hypotheses.

Table 4 displays the outcomes, illustrating the f² of suggested pathways and offering a thorough perspective on the magnitude and importance of the postulated correlations within the framework. These f² scores of 0.35 or above are deemed large, scores ranging from 0.15 to 0.35 are considered medium, and scores below 0.02 are considered small (Xiao et al., 2023). Table 4 findings indicate that f² for the influence of SORI and stakeholder pressure on SMGO is medium, and the influence of FEE and SORI on SME outcomes is medium. In contrast, the influence of FEE on SMGO and the impacts of SMGO and stakeholder pressure on direct and moderating affection is small. Lastly, the Q2 value of the SMGO = 0.337 and SME outcomes = 0.638 exceeds zero, demonstrating that the model offers substantial predictive relevance.

Figure 2 demonstrates the results of the proposed relationships among constructs with the hypothesized path coefficient and p-value in parentheses. For instance, β = 0.282 (0.000) reflects the H1a path coefficient and significance level. The R² values within the circle represent the explained variance in the variable. For example, FEE, SORI, and stakeholder pressure explained 49.2% of the SMGO variance, and all four factors, including SMGO, explained 85.2% of the variance in SME outcomes. The R2 values vary between 0 and 1; a higher R2 value signifies greater explanatory strength of the model (Xiao et al., 2023).

Multigroup analysis (MGA)

We have also used MGA to determine whether the associations among the variables being measured differ across discrete groups or subpopulations. Table 5 provides a detailed MGA of the relationship path coefficient and their p-values across the demographic categories, including gender, organization age, organization size, and employee role.

Turning to gender, FEE positively influences SMGO for males and females at 0.243 while negatively affecting SMEO for females at −0.167. SORI negatively affects SMGO for females at −0.224 while having a small, positive effect on SMEO at 0.083. SMGO negatively influences SMEO for males at −0.312. SP positively influences both SMGO and SMEO at 0.224 and 0.294, respectively, for females, while its interaction term with SMGO has a strong negative influence on SMEO at −0.428.

Considering the effect of organizational age, for young organizations (<1 year), FEE positively influences SMGO with 0.114 while negatively influences SMEO with −0.080. For organizations from 1 to 5 years of age, FEE influences negatively on both SMGO -0.279 and SMEO −0.130. For older organizations, in other words, 1–5 and above five years, the influence of FEE on SMGO is more negative,−0.394, while not significant on SMEO. In the case of younger firms, SORI does not significantly influence SMGO but starts to positively influence it in the 1–5 and above 5-year groupings. It also positively influences SMEO in younger organizations, though it is becoming insignificant for older organizations. SMGO negatively influences SMEO in younger organizations, while SP generally negatively affects SMEO across all age groups, especially for organizations over five years old.

Regarding organizational size, FEE significantly negatively influences neither small-scale organizations, which have less than 50 staff; however, FEE negatively impacts SMGO and SMEO for organizations with 51–250 employees and organizations employing between 251 to 1000 employees. Regarding SORI, it negatively influences SMGO in organizations having <50 employees but positively influences SMGO with an increase in the scale of the organization. Similarly, SORI negatively relates to SMEO in organizations with <50 employees, but with 251–1000, it becomes positive. The relationship between SMGO and SMEO is negative, with organizations having 50–250 and 251–1000 employees. SP did not significantly influence the path to SMGO; however, it negatively influences SMEO in organizations with 50–250 employees, while in organizations with 251–1000 employees, the impact of SP is insignificant. In this respect, the interaction of SP and SMGO is always negative for organizations with <50 and 50–250 employees and positive for organizations with over 250 employees with 0.542.

Lastly, concerning the employees’ roles, FEE negatively impacts SMGO for the CEO–Owner group with −0.202, though insignificant for the other groups. SORI, on the other hand, negatively affects the same group while positive for the different groups. SMGO positively influences SMEO for the CEO-Owner group but is negative at −0.667 for the Owner-Senior Manager Group. SP positively influences SMGO and SMEO within the CEO-Senior Manager Group, as does its interaction with SMGO on SMEO within the CEO-Owner Group, with 0.915, but is negative within the Owner-Senior Manager Group −0.317. This analysis also brings to light the moderating effects of these demographics, showing that relationships between variables vary markedly across different groups.

Mediation effect test

Our research used the bootstrapping technique to generate values of indirect effects, as Preacher and Hayes (2008) recommended. This method is more robust and applies to simple and multiple mediator models. The indirect impact of FEE (H3b: βindirect = 0.148, t = 7.841), SORI (H3c: βindirect = 0.205, t = 9.642), and SP (H3d: βindirect = 0.160, t = 10.668) on SME outcomes is found significant (see Table 4). Preacher and Hayes (2008) state that the mediation effect exists if zero is absent in the 95% confidence interval.

The study also conducted a mediation analysis using the variance accounted for (VAF) test, which is beneficial for assessing mediation effects. A VAF between 0.2 and 0.8 indicates partial mediation, while a VAF more significant than 0.8 signifies complete mediation, and less than 0.2 signifies no mediation (Baah et al., 2021; Shahzad et al., 2024).

\({VAF}{FEE}=\frac{{Indirect\; effect}}{{Total\; effect}}=\frac{0.148}{0.415}=35.6 \%\)

\({VAF}{SORI}=\frac{{Indirect\; effect}}{{Total\; effect}}=\frac{0.205}{0.420}=48.8 \%\)

\({VAF}{SP}=\frac{{Indirect\; effect}}{{Total\; effect}}=\frac{0.160}{0.291}=54.5 \%\)

Our study results show that the VAF value for FEE is 0.35, SORI 0.488, and SP 0.545, indicating that the model exhibits partial mediation. Table 4 represents the direct and indirect effect values.

Moderation effect test

Figure 3 illustrates a fundamental slope analysis showing the impact of SP on the association between SMGO and SME outcomes, with three lines (red, green, and blue). In particular, red, blue, and green lines illustrate impact 1 SD below the mean, at the mean, and 1 SD above the mean, respectively. The figure shows that with the increase in SMGO, there is a corresponding rise in SME outcomes, signifying a positive connection. The association becomes more robust as the stakeholder pressure escalates, with the most pronounced upward trajectory observed at +1 standard deviation, indicating that stakeholder pressure enhances the impact of SMGO on SME outcomes. Conversely, decreasing stakeholder pressure results in a more flattened connection, suggesting a lesser influence. This pattern indicates that stakeholders’ expectations might incentivize management to embrace more robust environmentally friendly practices, as evidenced by studies that link stakeholder pressure to heightened efforts in corporate sustainability through paths like consumer expectations, investor inclinations, and regulatory requirements.

Discussion of results

Environmental concerns have gained significant attention globally, particularly among companies with increased regulatory scrutiny, heightened public awareness, and stakeholder pressure to preserve nature (Han et al., 2019). Adoption and integration of green practices, therefore, have come to be perceived to open up new opportunities for value creation and improve SMEs’ performance (Agyapong et al., 2023; Baah et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). Even with the growing awareness of its significance, not many studies have been carried out to explore in detail how firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation can lead to improved corporate performance through substantial behavior. Our research presents an in-depth analysis related to the impact of firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and stakeholder pressure on senior management’s green orientation and the performance of SMEs.

Results reflect that the significant influence of firm environmental ethics on senior management’s green orientation supports the previous studies, which establish the importance of the ethical framework in developing sustainable business strategy. In the study, Han et al. (2019) found that firms’ environmental ethics in Chinese companies lead to adopting a green marketing program. The findings also support the fact that commitment towards ethics in SMEs is also there beyond compliance, which allows the firms to go green with a proactive environmental strategy. This confirms the work of Dragomir (2020) and Schuler et al. (2017), who demonstrated how firm environmental ethics creates an intrinsic value approach toward sustainability by moving beyond instrumental benefits.

Furthermore, we found that spiritual orientation is a strong predictor of senior management’s green orientation support. Casidy et al. (2024) found a significant link between the spiritual beliefs of senior executives and strategic green orientations in the United States SMEs. This study further strengthens this understanding by examining the Chinese context, where Confucianism and collective cultural values amplify the effect of spiritual beliefs on management decisions. In a research of Tokyo-based SMEs, Iguchi et al. (2022) found that spirituality results in more intense engagement with green activities. We also extend our data, as spiritual values create a sense of stewardship driving green-oriented decisions.

Our study observed that stakeholder pressure significantly moderates the impact of senior management’s green orientation on SME outcomes. High levels of stakeholder pressure from employees, the government, and others can leverage the positive outcomes that arise from a green strategic orientation. This amplification occurs through strengthening the firm’s dedication to sustainable practices, improving operational efficiencies, and market reputation (Adomako et al., 2023; Jing Xie et al., 2024). This finding is in line with Adomako and Tran (2022) and Guo and Wang (2022) studies, which highlighted the moderation effect of stakeholder pressure.

While previous studies considered strategic environmental orientation as an important influencer of firm performance, for example, Shaukat and Ming (2022), many were narrowly concentrated in certain sector-based studies or smaller samples. Our investigation fills this gap by adopting a wider sample of 489 Chinese SMEs across high-impacting sub-sectors like cement and textiles. The spiritual orientation, therefore, plays a nuanced role in influencing the senior management’s green orientation, providing an added layer of understanding from a spiritual belief integrated within the corporate culture that acts as a strong ethical backbone, creating a firm foundation upon which environmental initiatives may be launched.

Interestingly, while Mutmainah and Apriliantika (2023) did not detect any significant relationship between spiritual orientation and organizational performance, our findings differ in that the influence of spiritual orientation is partially mediated through an indirect path using senior management’s green orientation. The divergence in results may stem from contextual differences in the settings of the studies and specific interplays of Confucian values with stakeholder expectations in China.

Lastly, an area that needs further investigation is the impact of gender on senior management’s green orientation and sustainability outcomes. Our data did not bifurcate findings by gender, which is one of the study’s limitations. However, the literature suggests that gender diversity in leadership implies sustainability initiatives. For instance, Kassinis et al. (2016) and Singhania et al. (2024) observed that female leaders hold strong ethical values relative to males. The gender effect on sustainability practices is because of differences in values, risk perception, and collective-oriented behavior. Women executives tend to be more empathetic and more socially responsible; hence, there is stronger support for senior management’s green orientation in the presence of gender diversity.

In contrast, male leaders focus mostly on financial results and receive much consideration regarding short-term profitability and operational effectiveness (Chadwick & Dawson, 2018). Such strategic orientation to sustainability issues can then see most elements addressed, most often viewed from lenses focused on risk management or cost control or incremental, but not fundamental, transformation. Men may focus on solutions that fit current business models more closely, seeking cheap or less disruptive ways of pursuing sustainability. As a result, this difference in leadership priorities could determine how sustainability problems are approached at the organizational level, where women are more likely to support broader, socially-driven strategies, while men are likely to balance financial performance with sustainability objectives.

Theoretical implication

We present several theoretical implications stemming from our findings. Firstly, our research extends the resource-based perspective by suggesting that firm environmental ethics performs the role of an intangible asset in motivating strategic green orientation, which stands in line with the findings of (Aftab et al., 2022). The congruence of ethical norms with strategic green orientation means that SMEs with enhanced firm environmental ethics can implement eco-friendly practices in business operations to attain a competitive advantage. SMEs with substantial firm environmental ethics are more likely to alter their strategies and operations and embrace green initiatives to reduce costs and enhance their reputation, ultimately leading to better compliance outcomes (Baah et al., 2024).

Secondly, by incorporating spiritual orientation into the discussion, this study enriches the upper-echelon theory of Albert, Cannella (2001), pointing out that senior leaders use personal values to shape strategic organizational behaviors. This outcome facilitates the Albert, Cannella (2001) framework that individual characteristics influence an organization’s managerial decisions. Besides, our investigation emphasizes the importance of aligning senior management characteristics with organizational green strategies to enhance SME outcomes, mainly through environmental sustainability (Iguchi et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024; Mahran & Elamer, 2024). Additionally, by focusing on spiritual orientation as one of our primary constructs, we addressed Alabbad et al. (2022), Singh and Babbar (2021), and Zahari et al. (2024) demand for studies investigating the elements that influence SME adoption of green orientation and performance. We also answered Astrachan et al. (2020) and Casidy et al. (2024) call for contributions to the scarce research on the effect of spiritual orientation on the individual’s decision-making.

Lastly, our research outcomes extend stakeholder theory by showing how stakeholder expectations reinforce and magnify the implementation of senior management’s green orientation. It supports the notion that external pressures serve as a boundary condition in shaping how internal resources and orientations affect the outcomes (Osei et al., 2024). By testing the intervening impact of stakeholder pressure, our research also responds to recent calls for studies exploring the stakeholder pressure moderating role (Adomako & Tran, 2022; Guo and Wang, 2022), a topic gaining significance as it enlarges the impact of organizational motives towards sustainable practices leading to improved performance (Shahzad et al., 2024).

Managerial implication

The study findings recommend that SME leaders need to form a solid commitment to firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation to foster senior management’s green orientation. The focus will eventually influence the companies to achieve green innovation and operational enhancement, which confirms Aftab et al. (2022) and Jing Xie et al. (2024), who have mentioned that the ethical and spiritual framework leads to long-term benefits. Thus, the inclusion of firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation within organizational training and strategic development should be done to bring about the top-down approach toward sustainability. This can enable SMEs to sustain operations that are firmly positioned both by regulatory demands and market demands. Additionally, results reflect that leaders with a strong spiritual and ethical orientation can respond to sustainability challenges by incorporating their perceptions into strategic decisions. This is because the integration provides an increasing form of firm reputation, operational efficiency, and compliance, as affirmed by Cahan et al. (2015). In this respect, leaders should lead the green initiatives in organizations in guiding a way that could shape corporate culture and operational policy.

Furthermore, SMEs should not waste an opportunity presented by stakeholders to engage them in solidifying the value of senior management’s green orientation. By aligning green initiatives with stakeholders’ expectations, SMEs are well-placed to achieve higher performance outcomes through reduced environmental liabilities and ecologically sensitive consumer loyalty. Hence, strong channels of communication with stakeholders can help SMEs anticipate the expectations of the environment and meet them to achieve continued competitive advantage.

Moreover, the moderating results of stakeholder pressure highlight the significance of regulatory bodies and consumer advocacy groups for an enabling environment that could enable sustainable practices. These insights can be utilized by policymakers in developing policies that can provide incentives for green initiatives, as suggested by Guo and Wang (2022). It furthers that managers are supposed to be highly involved with stakeholders, understand their expectations, and consequently adapt their strategies to respond to such pressures. This proactive approach would increase the reputation and market position of SMEs.

Lastly, our study suggests that the government should promote firm environmental ethics to enhance economic growth. Publicizing the benefits of green initiatives and encouraging a culture that supports sustainability can help accomplish this objective. Governments should set up efficient institutional frameworks, organize forums for entrepreneurs, and facilitate interactions among businesses to strengthen environmental ethics. Financial incentives should be offered to support green activities, making eco-friendly businesses more economically viable. For example, the government could offer financial aid to companies engaged in voluntary environmental programs to help cover the substantial upfront costs of training employees, coordinating activities, and revising marketing strategies.

Conclusion

The present study offers key insights into how firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and the pressure from stakeholders influence senior management’s green orientation and, in turn, SMEs’ performance. Our findings indicate that developing a high commitment toward environmental ethics and inculcating spiritual orientation at the strategic leadership level significantly improves sustainable management practices and operational outcomes. Additionally, findings indicate that senior management’s green orientation plays a significant role in intermediating the link between firm environmental ethics, spiritual orientation, and SME outcomes. It further shows that stakeholder pressure amplifies the positive influence of senior management’s green orientation, which further justifies the need for stakeholder engagement to enhance sustainable orientations. This study provides evidence of how leaders who lead with high ethical and spiritual values integrate sustainability into their strategic decisions’ core, improving their reputation, operational efficiency, and compliance. The study findings facilitate the need for training and strategic development programs that integrate firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation to enable SMEs to meet both regulatory and market demands.

While this research offers robust contributions, it also recognizes some limitations: the cross-sectional design limits inferences on causality, stating that further studies using a longitudinal design would be more meaningful. Secondly, though senior management’s green orientation was assessed as a mediator, further studies can easily investigate other mechanisms through which firm environmental ethics and spiritual orientation influence performance. The focus on Chinese SMEs limits generalizability; thus, future studies must consider wider contexts. Lastly, the research used stakeholder pressure as a moderator; it can be a predictor that influences both senior management’s green orientation and SME outcomes. Additionally, the impact of gender on different factors also limited findings, which requires upcoming scholars to replicate the model. Hence, upcoming studies are suggested to test both effects.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14511542, and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abid N, Ceci F, Aftab J (2024) Attaining sustainable business performance under resource constraints: Insights from an emerging economy. Sustain Dev 32(3):2031–2048. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2763

Adomako S, Amankwah-Amoah J, Danso A, Dankwah GO (2021) Chief executive officers’ sustainability orientation and firm environmental performance: Networking and resource contingencies. Bus Strategy Environ 30(4):2184–2193. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2742

Adomako S, Simms C, Vazquez-Brust D, Nguyen HTT (2023) Stakeholder Green Pressure and New Product Performance in Emerging Countries: A Cross-country Study. Br J Manag 34(1):299–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12595

Adomako S, Tran MD (2022) Environmental collaboration, responsible innovation, and firm performance: The moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Bus Strategy Environ 31(4):1695–1704. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2977

Aftab J, Abid N, Sarwar H, Veneziani M (2022) Environmental ethics, green innovation, and sustainable performance: Exploring the role of environmental leadership and environmental strategy. J Clean Prod 378:134639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134639

Agyapong A, Aidoo SO, Acquaah M, Akomea S (2023) Environmental orientation and sustainability performance; the mediated moderation effects of green supply chain management practices and institutional pressure. J Clean Prod 430:139592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139592

Al Fozaie MT (2023) Behavior, religion, and socio-economic development: a synthesized theoretical framework. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 10(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01702-1

Alabbad A, Al Saleem J, Kabir Hassan M (2022) Does religious diversity play roles in corporate environmental decisions? J Bus Res 148:489–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.04.058

Albert A, Cannella J (2001) Upper echelons: Donald Hambrick on executives and strategy. Acad Manag Perspect 15(3):36–42. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.5229499

Albursan IS, AlQudah MF, Bakhiet SF, Alzoubi AM, Abduljabbar AS, Alghamdi MA (2016) Religious orientation and its relationship with spiritual intelligence. Soc Behav Personality: Int J 44(8):1281–1295. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.8.1281

Alotaibi A, Abbas A (2023) Islamic religiosity and green purchase intention: a perspective of food selection in millennials. J Islamic Mark 14(9):2323–2342. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-06-2021-0189

Alshukri, T, Seun Ojekemi, O, Öz, T, & Alzubi, A (2024). The Interplay of Corporate Social Responsibility, Innovation Capability, Organizational Learning, and Sustainable Value Creation: Does Stakeholder Engagement Matter? Sustainability, 16(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/su16135511

Appiah-Kubi E (2024) Management knowledge and sustainability reporting in SMEs: The role of perceived benefit and stakeholder pressure. J Clean Prod 434:140067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140067

Astrachan JH, Binz Astrachan C, Campopiano G, Baù M (2020) Values, Spirituality and Religion: Family Business and the Roots of Sustainable Ethical Behavior. J Bus Ethics 163(4):637–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04392-5

Awan U, Kraslawski A, Huiskonen J (2017) Understanding the Relationship between Stakeholder Pressure and Sustainability Performance in Manufacturing Firms in Pakistan. Procedia Manuf 11:768–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.07.178

Baah C, Agyabeng-Mensah Y, Afum E, Lascano Armas JA (2024) Exploring corporate environmental ethics and green creativity as antecedents of green competitive advantage, sustainable production and financial performance: empirical evidence from manufacturing firms. Benchmarking: Int J 31(3):990–1008. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2022-0352

Baah C, Opoku-Agyeman D, Acquah ISK, Agyabeng-Mensah Y, Afum E, Faibil D, Abdoulaye FAM (2021) Examining the correlations between stakeholder pressures, green production practices, firm reputation, environmental and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing SMEs. Sustain Prod Consum 27:100–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.015

Barney J (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Bjork-James S (2023) Lifeboat Theology: White Evangelicalism, Apocalyptic Chronotopes, and Environmental Politics. Ethnos 88(2):330–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1839527

Cahan SF, Chen C, Chen L, Nguyen NH (2015) Corporate social responsibility and media coverage. J Bank Financ 59:409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2015.07.004

Cantele S, Zardini A (2020) What drives small and medium enterprises towards sustainability? Role of interactions between pressures, barriers, and benefits. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(1):126–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1778

Carr D (2018) Spirituality, spiritual sensibility and human growth. Int J Philos Relig 83(3):245–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11153-017-9638-x

Carvalho CE, Rossetto CR, Verdinelli MA (2016) Strategic Orientation as a Mediator Between Environmental Dimensions and Performance: A Study of Brazilian Hotels. J Hospitality Mark Manag 25(7):870–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2016.1130668

Case, SS, & Chavez, E (2017). Measuring religious identity: developing a scale of religious identity salience. International Association of Management, Spirituality and Religion, USA, 1–27

Casidy, R, Arli, D, & Tan, LP (2024). The Influence of Religious Identification on Strategic Green Marketing Orientation. J Business Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05658-3

Cebula RJ, Rossi F (2021) Religiosity and corporate risk-taking: evidence from Italy. J Econ Financ 45(4):751–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-021-09543-x

Chakabva O, Tengeh RK (2023) The relationship between SME owner-manager characteristics and risk management strategies. J Open Innov: Technol, Mark, Complex 9(3):100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100112

Chadwick IC, Dawson A (2018) Women leaders and firm performance in family businesses: An examination of financial and nonfinancial outcomes. J Fam Bus Strategy 9(4):238–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2018.10.002

Chang C-H (2011) The Influence of Corporate Environmental Ethics on Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Role of Green Innovation. J Bus Ethics 104(3):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0914-x

Chen YP, Zhuo Z, Huang Z, Li W (2022) Environmental regulation and ESG of SMEs in China: Porter hypothesis re-tested. Sci Total Environ 850:157967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157967

Choi D, Hwang T (2015) The impact of green supply chain management practices on firm performance: the role of collaborative capability. Oper Manag Res 8(3):69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-015-0100-x

Choudhury D, Rao VG, Mishra MK (2019) Impact of strategic and tactical green marketing orientation on SMEs performance. Theor Econ Lett 9:1633–1650. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2019.95104

Chung KC (2020) Green marketing orientation: achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. J Hospitality Mark Manag 29(6):722–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1693471

Coşkun A, Vocino A, Polonsky M (2017) Mediating effect of environmental orientation on pro-environmental purchase intentions in a low-involvement product situation. Australas Mark J (AMJ) 25(2):115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.04.008

Cui J, Jo H, Velasquez MG (2015) The Influence of Christian Religiosity on Managerial Decisions Concerning the Environment. J Bus Ethics 132(1):203–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2306-5

Dangelico RM, Pujari D (2010) Mainstreaming Green Product Innovation: Why and How Companies Integrate Environmental Sustainability. J Bus Ethics 95(3):471–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0434-0

Dhir A, Khan SJ, Islam N, Ractham P, Meenakshi N (2023) Drivers of sustainable business model innovations. An upper echelon theory perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Change 191:122409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122409

Dragomir, VD (2020). Ethical Aspects of Environmental Strategy. In VD Dragomir (Ed.), Corporate Environmental Strategy: Theoretical, Practical, and Ethical Aspects (pp. 75-113). Cham: Springer International Publishing

Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Childe SJ, Blome C, Papadopoulos T (2019) Big Data and Predictive Analytics and Manufacturing Performance: Integrating Institutional Theory, Resource-Based View and Big Data Culture. Br J Manag 30(2):341–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12355

Dudley RG (2007) Payments, penalties, payouts, and environmental ethics: a system dynamics examination. Sustainability: Sci, Pract Policy 3(2):24–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2007.11907999

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2000) Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strategic Manag J 21(10-11):1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

Elfenbein DW, McManus B (2010) A greater price for a greater good? Evidence that consumers pay more for charity-linked products. Am Economic J: Economic Policy 2(2):28–60

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Freeman RE (1999) Divergent Stakeholder Theory. Acad Manag Rev 24(2):233–236. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.1893932

Godfrey PC, Merrill CB, Hansen JM (2009) The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: an empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Manag J 30(4):425–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.750

Guo Y, Wang L (2022) Environmental Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Environmental Innovation and Stakeholder Pressure. Sage Open 12(1):21582440211061354. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211061354

Guo Y, Wang L, Yang Q (2020) Do corporate environmental ethics influence firms’ green practice? The mediating role of green innovation and the moderating role of personal ties. J Clean Prod 266:122054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122054

Hair, JF, Hult, GTM, Ringle, CM, Sarstedt, M, Danks, NP, & Ray, S (2021). An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In JF Hair Jr, GTM Hult, CM Ringle, M Sarstedt, NP Danks, & S Ray (Eds.), Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook (pp. 1-29). Cham: Springer International Publishing

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hakovirta M, Denuwara N, Topping P, Eloranta J (2023) The corporate executive leadership team and its diversity: impact on innovativeness and sustainability of the bioeconomy. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 10(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01635-9

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad Manag Rev 9(2):193–206. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1984.4277628

Han M, Lin H, Wang J, Wang Y, Jiang W (2019) Turning corporate environmental ethics into firm performance: The role of green marketing programs. Bus Strategy Environ 28(6):929–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2290

Hiebl MRW (2014) Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. J Manag Control 24(3):223–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-013-0183-1

Hill PC, Pargament II K, Hood RW, McCullough JME, Swyers JP, Larson DB, Zinnbauer BJ (2000) Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. J Theory Soc Behav 30(1):51–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00119

Hong P, Kwon HB, Jungbae Roh J (2009) Implementation of strategic green orientation in supply chain. Eur J Innov Manag 12(4):512–532. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060910996945

Hoştut S, van het Hof SD, Aydoğan H, Adalı G (2023) Who’s in and who’s out? Reading stakeholders and priority issues from sustainability reports in Turkey. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 10(1):773. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02264-y

Iguchi H, Katayama H, Yamanoi J (2022) CEOs’ religiosity and corporate green initiatives. Small Bus Econ 58(1):497–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00427-8

Kassinis G, Panayiotou A, Dimou A, Katsifaraki G (2016) Gender and Environmental Sustainability: A Longitudinal Analysis. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 23(6):399–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1386

Kennedy EJ, Lawton L (1998) Religiousness and Business Ethics. J Bus Ethics 17(2):163–175. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005747511116

Khan EA, Royhan P, Rahman MA, Rahman MM, Mostafa A (2020) The Impact of Enviropreneurial Orientation on Small Firms’ Business Performance: The Mediation of Green Marketing Mix and Eco-Labeling Strategies. Sustainability 12:221, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/1/221 Retrieved from

Khan KU, Xuehe Z, Atlas F, Khan F (2019) The impact of dominant logic and competitive intensity on SMEs performance: A case from China. J Innov Knowl 4(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2018.10.001

Khizar, HMU, Iqbal, J, Khalid, J, & Hameed, Z (2023). Unlocking the complementary effects of multiple strategic orientations on firm performance: an interplay of entrepreneurial, sustainability and market orientation. Kybernetes, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/K-03-2022-0319

Kim J (2022) Extending upper echelon theory to top managers’ characteristics, management practice, and quality of public service in local government. Local Gov Stud 48(3):556–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1882427

Kline, P (2015). A handbook of test construction (psychology revivals): introduction to psychometric design (1st ed.). London: Routledge

Kock N (2019) From composites to factors: Bridging the gap between PLS and covariance-based structural equation modelling. Inf Syst J 29(3):674–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12228

Krok D (2008) The role of spirituality in coping: Examining the relationships between spiritual dimensions and coping styles. Ment Health, Relig Cult 11(7):643–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670801930429

Li X, Guo F, Wang J (2024) A path towards enterprise environmental performance improvement: How does CEO green experience matter? Bus Strategy Environ 33(2):820–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3524

Liu, Y, Xi, M, & Wales, WJ (2023). CEO entrepreneurial orientation, human resource management systems, and employee innovative behavior: An attention-based view. Strategic Entrepreneurship J https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1488

Lockwood M (2018) Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Environ Politics 27(4):712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1458411

Lu C, Yu B, Zhang J, Xu D (2021) Effects of open innovation strategies on innovation performance of SMEs: evidence from China. Chin Manag Stud 15(1):24–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-01-2020-0009

Madrid-Guijarro A, Duréndez A (2024) Sustainable development barriers and pressures in SMEs: The mediating effect of management commitment to environmental practices. Bus Strategy Environ 33(2):949–967. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3537

Mady K, Battour M, Aboelmaged M, Abdelkareem RS (2023) Linking internal environmental capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage in manufacturing SMEs: The mediating role of eco-innovation. J Clean Prod 417:137928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137928

Mahran K, Elamer AA (2024) Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and corporate environmental sustainability: A systematic literature review and avenues for future research. Bus Strategy Environ 33(3):1977–2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3577

Margaça, C, Sánchez-García, JC, Cardella, GM, & Hernández-Sánchez, BR (2022). The role of spiritual mindset and gender in small business entrepreneurial success. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1082578

Marrucci L, Daddi T, Iraldo F (2023) Institutional and stakeholder pressures on organisational performance and green human resources management. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30(1):324–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2357

Meng B, Liu Y, Andrew R, Zhou M, Hubacek K, Xue J, Gao Y (2018) More than half of China’s CO2 emissions are from micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Appl Energy 230:712–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.08.107

Menguc B, Auh S, Ozanne L (2010) The Interactive Effect of Internal and External Factors on a Proactive Environmental Strategy and its Influence on a Firm’s Performance. J Bus Ethics 94(2):279–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0264-0

Minton EA, Kahle LR, Kim C-H (2015) Religion and motives for sustainable behaviors: A cross-cultural comparison and contrast. J Bus Res 68(9):1937–1944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.003

Mutmainah I, Apriliantika A (2023) The mediating effect of Islamic ethical identity disclosure on financial performance. Asian J Islamic Manag (AJIM) 5(1):69–82

Naiman SM, Stedman RC, Schuldt JP (2023) Latine culture and the environment: How familism and collectivism predict environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions among U.S. Latines. J Environ Psychol 85:101902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101902

Noordin F, Williams T, Zimmer C (2002) Career commitment in collectivist and individualist cultures: a comparative study. Int J Hum Resour Manag 13(1):35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190110092785

Nugroho A, Prijadi R, Kusumastuti RD (2022) Strategic orientations and firm performance: the role of information technology adoption capability. J Strategy Manag 15(4):691–717. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-06-2021-0133

OECD. (2023). Sustainable SMEs. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/data-insights/sustainable-smes

OECD. (2024). People’s Republic of China. In Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2024: An OECD Scoreboard (pp. 1-12). Paris: OECD

Orellano A, Valor C, Chuvieco E (2020) The Influence of Religion on Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 12(19):7901, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/19/7901 Retrieved from

Osei CD, Zhuang J, Adu D (2024) Impact of regulatory, normative and cognitive institutional pressures on rural agribusiness entrepreneurial opportunities and performance: empirical evidence from Ghana. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev 27(4):651–670. https://doi.org/10.22434/ifamr1008

Papadas K-K, Avlonitis GJ, Carrigan M, Piha L (2019) The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J Bus Res 104:632–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.009

Peng MY-P, Zhang L, Lee M-H, Hsu F-Y, Xu Y, He Y (2024) The relationship between strategic human resource management, green innovation and environmental performance: a moderated-mediation model. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 11(1):239. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02754-7

Petro, G (2022). Consumers Demand Sustainable Products And Shopping Formats. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/gregpetro/2022/03/11/consumers-demand-sustainable-products-and-shopping-formats/?sh=4fce0ebe6a06

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Qalati SA, Barbosa B, Ibrahim B (2023) Factors influencing employees’ eco-friendly innovation capabilities and behavior: the role of green culture and employees’ motivations. Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03982-8

Qalati SA, Siddiqui F, Magni D (2024) Senior management’s sustainability commitment and environmental performance: Revealing the role of green human resource management practices. Business Strategy and the Environment, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3962

Reyes-Gómez, JD, López, P, & Rialp, J (2024). The relationship between strategic orientations and firm performance and the role of innovation: a meta-analytic assessment of theoretical models. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2022-0200