Abstract

The expansion of global seafood value chains in recent decades has benefited developing countries, which are key producers and exporters. However, developing countries still need to upgrade themselves in many relevant areas to meet requirements such as product and labor standards proposed by global buyers. Upgrading is recognized as a pathway for developing countries to capture more benefits or maintain their position within those chains. Determining which types of upgrades are suitable for each country is challenging. This research uses the gravity model to examine the impacts of value chain upgrading on seafood exports from developing countries. The key findings suggest that product upgrading positively affects traded seafood, while the impacts of process and functional upgrading on the seafood exports of the selected countries can be positive and negative. In addition, social improvements are more important for seafood exports to developed countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, seafood products have been widely recognized as significant traded items in the global value chains (GVCs) of the agri-food sector. Seafood exports constitute approximately 11% of traded agricultural products and involve over 59 million people (Cojocaru et al., 2022; FAO, 2022). Compared with other products, seafood holds a larger export share in global markets. Moreover, more than 70% of the world’s seafood production is exported (Natale et al., 2015; Yang & Anderson, 2020). The value of world seafood exports has grown from 55,287 million US dollars in 2003 to 155,988 million US dollars in 2021. Despite facing economic crises, such as the 2008 global financial crisis and the European debt crisis, world seafood exports rapidly recovered from 2003 to 2021 (Cojocaru et al., 2022; FAO, 2022).

Developed countries (e.g., Japan and the United States) are significant buyers in global markets. In contrast, developing countries (e.g., India and Thailand) are the top exporters of seafood products. Between 2003 and 2021, developing countries accounted for more than 50% of global seafood market exports. An expansion of traded seafood products can benefit developing countries, for example, by reducing poverty at the local level (FAO, 2022).

Developing countries in the global seafood market face numerous requirements from international buyers, such as food safety and labor standards. Failure to meet these requirements may lead to a loss of market share and the associated benefits. Developing countries need to upgrade themselves in several relevant areas to meet the requirements and product standards of aquaculture and to continue exporting seafood products to global markets. For example, Thai seafood products were banned from the United States and the EU since human trafficking and Illegal Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing problems were found in the Thai seafood industry from 2014 to 2015 (Kadfak & Linke, 2021). To overcome the labor problem, the Thai government implemented the Labor Protection Act to improve labor standards for the seafood industry (Wongrak et al., 2021). Owing to the Thai government’s efforts, Thai seafood products have been exported to the US and EU markets since 2019.

According to the literature on GVC analysis, upgrading is essential for developing countries to improve and advance up the value ladder. Upgrading can be categorized into two subtypes: economic upgrading (EUP) and social upgrading (SUP). EUP includes four subtypes: product, process, functional, and intersectoral upgrading. In contrast, SUP involves enhancing entitlements and workers’ rights (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002).

However, determining which types of upgrades are appropriate for each value chain or each country is challenging. The decision to upgrade depends on several criteria, such as trading partners and product characteristics (Ponte & Ewert, 2009). Furthermore, upgrading can negatively affect producers and exporters; in particular, it can lead to an increase in their production costs (Baldwin, 2014; Pahl & Timmer, 2020). These are the key motivations for the study, which addresses the following key research question: How can the seafood sector of developing countries be upgraded to expand their traded seafood in global markets?

Accordingly, the key objective of this research is to assess the impacts of EUP and SUP on the seafood exports of developing countries. According to the literature, the effects of value chain upgrading have been inconclusive (Malcorps et al., 2021). However, empirical studies examining the effects of EUP and SUP on seafood exports have been scarce, especially in developing countries (Malcorps et al., 2021; Ponte et al., 2014). These are significant research gaps in the relevant literature. Previous studies have often focused on the benefits of GVC participation, such as export growth and improvements in labor productivity (Eegunjobi & Ngepah, 2022; Pahl & Timmer, 2020). This study analyzes the effects of EUP and SUP on seafood exports from developing countries to various groups of export destinations on the basis of the gravity model. The study period spans from 2003 to 2021. The study’s results are expected to provide broader perspectives on the effect of value chain upgrading on the exports of developing countries and can fill literature gaps in the field of GVC analysis. The selected developing countries include Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam, which were major exporters in global markets during the study period. These countries collectively held a market share of approximately 75% of traded seafood exported from developing countries between 2003 and 2021 (FAO, 2022).

The remainder of this paper is structured into five sections. Section “Traded seafood of developing countries in world markets” provides an overview of seafood traded by developing countries in world markets. A literature review related to EUP and SUP is presented in Section “The debate on upgrading in GVCs: Literature review.” Section “Methodology and data” presents the methodology and data, while the empirical findings and discussion are elaborated in Section “Empirical results and discussion.” Section “Summary and policy implications” presents the conclusions and policy implications.

Traded seafood of developing countries in world markets

Developing countries have become key exporters of traded seafood (Cojocaru et al., 2022). The market share of developing countries increased from 48.89% of total world seafood exports in the 2003–2008 period to 55.80% in the 2015–2021 period (Table 1). In contrast, the market share of developed countries decreased from 51.12% of total world seafood exports to 44.20% over the same period. Several developing countries have become important exporters in global seafood markets. More specifically, China is the top exporter of seafood products among the key developing countries. The Chinese export share of seafood products was approximately 24.91% of the total seafood exports of all developing countries between 2003 and 2021. Thailand, Vietnam, and Chile followed China in the rankings during the same period. In particular, the seafood export shares of Thailand and Vietnam accounted for 10% of the total seafood exports of all developing countries from 2003 to 2021.

The major export destinations for seafood products of developing countries are the United States and Japan, which are classified as the “South to North” trade pattern (Table 2). Notably, the export share of key developing countries is concentrated in a few countries. For example, more than 50% of Chilean and Indonesian seafood products were exported to the United States and Japan between 2003 and 2021. Approximately 40% of total Thai seafood exports during the same period were exported to the same destinations. Interestingly, some key exporters exported their seafood products to developing countries; this is called the “South to South” trade pattern (Cojocaru et al., 2022; Malcorps et al., 2021). For example, Uruguay was a major export destination for Chinese seafood products.

Table 3 presents the EUP and SUP indicators of the selected developing countries. In general, the selected developing countries faced both product upgrading and downgrading between 2003 and 2021. Table 3 presents the variable of export value per import refusals; it is the proxy for process upgrading. Table 3 suggests that the selected developing countries achieved process upgrading for seafood exports from 2003 to 2021. The export value per import refusals of seafood products of the selected developing countries increased from 195.02 to 526.99 million U.S. dollars. With respect to net outflows of foreign direct investment (OFDI) and Human Development Index (HDI) variables that proxy for functional and social upgrading, Table 3 shows that these two variables increased slightly between 2003 and 2021.

The debate on upgrading in GVCs: Literature review

Upgrading is widely acknowledged as a significant aspect of GVC analysis. It involves economic activities that assist companies or countries in moving up the value chain. According to the literature, there are two core types of upgrading: EUP and SUP (Bernhardt & Milberg, 2011). On the one hand, EUP includes four subtypes of upgrading: product, process, functional, and intersectoral upgrading. Product upgrading involves improving product quality. For example, exporters can produce seafood products with high value-added. Process upgrading involves improving production processes more efficiently. For example, exporters or producers in the seafood industry upgrade their production process to meet new food safety standards. In addition, functional upgrading occurs when countries can move from existing functions to advanced functions in value chains, such as moving from simple producers to brand designers. Focusing on intersectoral upgrading, it explains the situation in which firms can use the knowledge and skills captured from an existing value chain to launch a new business in other value chains. SUP explains processes of improving entitlements and employees’ rights, such as wages and the fairness of employers (Milberg & Winkler, 2011).

However, determining the appropriate types of upgrading for each country can be challenging. It depends on the characteristics of GVC governance and products. Additionally, each type of upgrading has different impacts on export activities. For example, Eegunjobi and Ngepah (2022) suggest that under captive value chain governance, countries acting as suppliers may be limited to narrow and simple tasks (e.g., simple production). Furthermore, the leading firms in a value chain may limit export destinations for their suppliers.

Derived demand effects can cause SUP, which means that EUP may have a positive effect on SUP. However, previous studies have suggested that EUP does not necessarily have positive effects on SUP, especially in developing countries (Pahl & Timmer, 2020). Countries achieving economic upgrading, for example, by using new technologies related to GVC production, subsequently decreasing the use of unskilled labor as an input factor (Baldwin, 2014; Barrientos et al., 2011). In addition, labor exploitation problems in the Thai processed food industry have been identified, although Thailand is a key exporter of traded processed food (Kadfak & Linke, 2021).

According to previous studies, upgrading measurements are inconclusive. Several measures of EUP and SUP depend on product characteristics, data availability, and the level of analysis (i.e., country-level or company-level). Product upgrading is commonly proxied by increasing product prices (Ponte & Ewert, 2009). However, increasing product prices may reflect a shift in the costs of production. If product prices are explained by a shift in these costs, it can be misleading with respect to product quality. Thus, both market shares and product prices need to be used to calculate product upgrading. Countries frequently face a decrease in their market share in global markets if they cannot achieve cost competitiveness (Kaplinsky & Readman, 2005).

For alternative measures of product upgrading, Khandelwal et al. (2013) quantify the quality of products by using product prices, market share, and elasticities of substitution. However, Curzi, Pacca (2015) suggest that elasticities of substitution are not easy to compute, particularly for agri-food products. Bernhardt and Milberg (2011) use an equally weightedFootnote 1 impact of changes in the export share and export price in export markets to calculate the composite index for describing product quality. Positive and negative values of the index value represent product upgrading and downgrading, respectively. Since the composite index relies on trade data, it can calculate product upgrades for various products and countries (Bernhardt & Pollak, 2016).

When process upgrading, especially in the food sector, is considered, import refusal is a proxy variable (Baylis et al., 2010). If exporting countries can upgrade their production process to meet the standards and requirements proposed by global buyers, the import refusals of exporting countries should be reduced (Jongwanich, 2009).

Previous research has used some proxy variables to describe functional upgrading. For example, the diversification of exports is used to elaborate the functional upgrading of countries, as discussed in Kowalski et al. (2015). However, Jongwanich (2020) noted that the diversification of exports can explain a situation in which countries export existing products to new export markets. In contrast, Pananond (2012) and OECD-UNIDO (2019) suggest that a change in the OFDI can explain a functional upgrading situation. When exporters want to be distributors in overseas markets, they are often required to increase their OFDI in overseas countries.

The measurement of intersectoral upgrading is challenging because it presents only a broad perspective on upgrading. For example, exporters may start exporting new products, but this does not indicate which areas or aspects of countries need improvement (Ponte & Ewert, 2009).

Milberg and Winkler (2011) propose that social upgrading can be explained by relevant variables, such as employment, wages, and human resource development (i.e., HDI), depending on data availability. Bernhardt and Milberg (2011) developed an index that combines changes in wages and employment to quantify social upgrading. They use equally weighted effects of employment and wages, as previous studies have not presented exact measures. Positive and negative values of the index refer to social upgrading and downgrading, respectively.

Few previous studies have explored the effects of EUP and SUP on trade. For example, Baylis et al. (2010) suggest that countries experience a reduction in their exports if they cannot comply with the sanitary and phytosanitary standards (SPS). In addition, Lin (2016) shows that FDI outflows positively impact trade.

Methodology and data

The conceptual framework

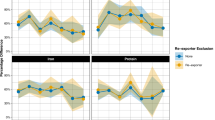

As discussed in Section “Introduction”, this study develops a conceptual framework for assessing the effects of EUP and SUP on the seafood exports of developing countries. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the conceptual framework shows that the key independent variables are EUP and SUP, and other control variables (i.e., gross domestic product (GDP) and trade agreements). The dependent variable is the seafood exports of the selected countries to their partners (developed and developing countries). Positive or negative impacts can be found by focusing on the effects of EUP and SUP on seafood exports. For example, if a country can achieve social upgrading to meet global buyers’ requirements, it tends to keep its exports to global markets. However, social upgrading may lead to higher production costs, decreasing cost competitiveness in global markets.

Model specification

On the basis of the conceptual framework, this study examines the impacts of EUP and SUP on traded seafood products from developing countries to various destinations (i.e., developed and developing countries). The gravity model of trade is commonly accepted to describe bilateral trade flows. As displayed in Eq. (1), the trade between countries i and j (Tij) is essentially explained by their GDP and the geographical distance between these two countries (Head & Mayer, 2010; Santos Silva & Tenreyro, 2006).

Previous studies augmented the parameter (\(\alpha\)), a control variable, by using other control variables, such as population, trade agreements, exchange rates, and economic crises (Bensassi et al., 2015; Thuong, 2017). According to the literature, the population variable can have either positive or negative effects on trade flows between two countries. An increasing population can expand a domestic market, leading to a trade expansion between two countries. However, an increase in population can explain a larger domestic resource endowment and market. This situation can indicate less reliance on trade between two countries. Consequently, the coefficient sign of the population variable will be negative (Papazoglou, 2007). Prior empirical research indicated that trade agreements between two countries can significantly or non-significantly affect bilateral trade. For instance, trade agreements may be established to bolster a political relationship, irrespective of critical factors, such as the domestic resource endowment (Bensassi et al., 2015; Jongwanich, 2009). In addition, several studies have examined the impact of the global financial crisis on trade. Athukorala (2012) suggested that the global financial crisis in 2008 often negatively affected global trade. Previous studies have shown that exchange rate depreciation positively (negatively) affects exports (imports) (Baylis et al., 2010).

Consequently, the study uses the gravity model to investigate the effects of EUP and SUP on the seafood exports of the chosen developing countries. The study also controls for the unobserved characteristics of each trading partner. The dependent variable is the seafood exports of the selected developing countries to their trading partners. The key regressors are EUP and SUP. Moreover, the study adds lagged variables of process and functional upgrading (represented by OFDI) to Eq. (1). Baylis et al. (2010) and Lin (2016) suggest that exporters sometimes need to increase their investment in machinery or capital to improve their production process or change their economic activities in the beginning. Thus, the effects of process and functional upgrading may be seen in their lagged variables. This study does not include intersectoral upgrading in the empirical model because measuring and assigning appropriate proxy variables are difficult (Ponte & Ewert, 2009). Other regressors include GDP, distance, population, trade agreements between two countries, the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 crisis, real exchange rates, and macroeconomic variables related to the politics and government performance of each exporter (corruption and government effectiveness indices).

In addition, the study separates export destinations into two subgroups: developed and developing countries (The United Nations (2022)). This division provides more information about two trade characteristics: south-to-north and south-to-south trade patterns. The empirical model is shown in Eq. (2). Table 4 provides the definitions of all the variables used in Eq. (2).

To estimate Eq. (2), the use of the least squares technique to apply the gravity equation poses three main problems (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, 2006). First, biased estimators occur when the least squares technique is used to estimate the log-linearized model due to Jensen’s inequality. Second, even when fixed effects are controlled for, the gravity model regressed in the log-linear model form can still suffer from problems of heteroskedasticity, resulting in inefficient estimations. Third, the log-linear estimation suffers from zero-value trade flows due to logarithmic rules (Staub & Winkelmann, 2013). Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006), (2011), and (2022) suggest the use of the Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood (PPML) technique to address these three issues when the gravity model is used. The PPML estimation is chosen because the gravity model is formulated as a constant-elasticity model. Additionally, when estimated using the PPML technique, the dependent variable can be in the form of a trade value itself rather than a logarithmic term.

As a result, this study employs the PPML estimation to analyze Eq. (2). The dependent variable is export values. The coefficients estimated by the PPML technique can be considered the elasticity for independent variables in the logarithm form. If independent variables are not in the logarithmic form, their coefficients are elaborated as semi-elasticities. Dummy variables can be computed via the formula \(\left({{\rm{e}}}^{{{\rm{b}}}_{{\rm{i}}}}-1\right)\)*100% (where bi is the coefficient) to explain their elasticity (Silva & Tenreyro, 2006).

Data and variable measurement

The study period spans from 2003 to 2021 because of the availability of data. The seafood products considered in this study include HS0302, HS0303, HS0304, HS0305, HS0306, HS0307, and HS0308 (these products are subproducts in the Harmonized Code 03; fish and crustaceans, mollusks and other aquatic invertebrates), HS1604, and HS1605 (they are preparations of fish or crustaceans, mollusks or other aquatic invertebrates) (World Customs Organization, 2017; Yang & Anderson, 2020). The selected developing countries are Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam because they were major exporters of seafood products in world markets during the study period, and data for these countries are readily available (FAO, 2022). The export values (in millions of USD) of seafood products of the selected developing countries to their trading partners are extracted from the UN Comtrade database. The study uses a cutoff threshold of 0.1% of the average value of seafood exports to avoid miscellaneous export values. If the export values are lower than the threshold, they are rounded to zero. This study also evaluates the sensitivity of this value. Values slightly above or below this point show minor differences in the number of export values and partners.

The GDP it, GDPjt, Popit, Popjt, and Disij values are obtained from the World Development Indicators and CEPII database (CEPII, 2022; World Bank, 2022). TAijt, FCRIt, and COVIDt are dummy variables. RERijt is computed from the nominal exchange rate between exporter i and partner j, adjusted by the ratio of the average prices of partner j to the average prices of exporter i. The nominal exchange rate is extracted from the World Bank database. The control of corruption and government effectiveness indices are obtained from the Worldwide Governance Indicators.

The study uses equally weighted effects of changes in the market shares (%∆MS) and export prices (%∆EV) of seafood products to compute PRODit. The export price is computed by export values divided by export quantities (Bernhardt & Pollak, 2016). For the process upgrading variables (PROCit and PROCit-1), the study employs the export values of the selected countries per import refusals as a proxy variable. The import refusal data for seafood products are from the The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2022). In terms of the functional upgrading variables (OFDIit and OFDIit-1), this study uses net outflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) (% of GDP) as proxies for each exporter. The study does not add intersectoral upgrading to the empirical model because this upgrading cannot clearly explain what aspects of countries should be focused on (Milberg & Winkler, 2011). In addition, this study employs HDIit to present the social upgrading of each exporter (Milberg & Winkler, 2011). This index captures three main dimensions related to social areas: healthy life, knowledge, and standards of living. The FDI net outflows and the HDI are from the World Bank and United Nations Development Program (UNDP) database.

Empirical results and discussion

The impact of value chain upgrading on seafood exports from the selected countries to developed countries

Section “The impact of value chain upgrading on seafood exports from the selected countries to developed countries” presents empirical findings of the effects of the EUP and SUP on the exports of seafood products from the selected countries to developed countries, which is called the south-to-north trade pattern. The key findings reveal that the EUP and SUP variables have varying effects on seafood exports from the selected exporters to developed countries. Product upgrading positively and significantly affects seafood exports for most exporters, including Chile, India, Indonesia, Morocco, and Thailand. The estimated semi-elasticity ranges from 0.001 to 0.007 (Table 5). Compared with other selected countries, product upgrading in seafood exports is particularly significant for Morocco and Thailand. However, product upgrading has insignificant effects on seafood exports from China, Russia, and Vietnam.

The results suggest that process upgrading negatively affects seafood exports from Chile and China. The estimated elasticity is −0.316 for Chile and −0.067 for China. Conversely, it has positive effects on the seafood exports of India, Russia, and Thailand. The estimated elasticities are 0.156 for India, 0.307 for Russia, and 0.092 for Thailand. The results also show that the lagged variable of process upgrading negatively affects seafood exports from Chile, China, and Morocco. However, the lagged variable positively affects Russian seafood exports. This study’s findings suggest that Chile and China experience negative impacts from process upgrading, in both the current and lagged periods, on their exports to developed countries. These results support the findings of Baylis et al. (2010) and Suanin (2022). That is, when countries adhere to the product standards and requirements established by importers in global markets, their production costs may increase. As a result, this increase can reduce the export competitiveness of these countries.

When the functional upgrading variable is considered, the findings reveal both positive and negative effects of the variable on seafood exports among selected exporters. Specifically, the functional upgrading variable positively affects seafood exports from Morocco and Thailand. Conversely, it negatively affects Indonesian, Russian, and Vietnamese seafood exports. Additionally, the lagged variable of functional upgrading is statistically significant for the seafood exports of the chosen exporters. It positively affects seafood export products from Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam. At the same time, it negatively affects seafood products from Chile. Chen et al. (2019) and Yan et al. (2023) highlight that the impacts of OFDI on the home country’s economy can vary depending on factors such as the business environment and productive sectors. Furthermore, OFDI often promotes exports from low-productivity sectors, such as primary products. Notably, an increase in OFDI from emerging countries may reduce domestic investment and production, subsequently leading to lower export growth.

In addition, social upgrading has both positive and negative effects on seafood exports. Specifically, social upgrading positively affects seafood exports from India, Morocco, and Russia. However, a negative effect of social upgrading on traded seafood was observed for China, Indonesia, and Thailand. This outcome can be attributed to the fact that the social upgrading variable is proxied by the HDI, which encompasses various relevant aspects, such as wages. As a result, social upgrading may lead to higher production costs for seafood products, subsequently reducing the cost competitiveness of these exporters in global markets. These findings support the results of Baldwin (2014), Pahl and Timmer (2020), and Ponte and Ewert (2009). That is, the effects of value chain upgrading on exports vary, depending on product characteristics and countries.

Through the lens of GVCs, Table 5 suggests that product upgrading positively affects the seafood exports of most selected countries. This result supports the findings of Humphrey and Schmitz (2002). That is, product upgrading is fundamental for survival within GVCs, especially for agri-food value chains. However, process and social upgrading have both positive and negative effects on seafood exports to developed countries. In particular, if a country aims to achieve process upgrading, it needs to develop its production process, subsequently increasing production costs and decreasing cost competitiveness in global markets. Table 5 also suggests that functional upgrading has less of an impact on the seafood exports of the selected exporters than does product and process upgrading. The reason is that the leading firms in some value chains allow their suppliers to achieve only product and process upgrades. The leading firms in productive sectors in GVCs usually manipulate significant activities in the value chain, such as product distribution in retail markets (Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002; Ponte & Ewert, 2009).

With respect to the other variables, the GDP of China and India has positive impacts on their seafood exports (Table 5). However, the GDP of Morocco, Russia, and Thailand negatively affects their seafood exports. These results support the findings of Natale et al. (2015). Additionally, trading partner GDP positively traded seafoods from Chile and Thailand to developed countries.

Table 5 also suggests that the Chilean population variable significantly and positively affects Chilean seafood exports. In contrast, India’s population has a significantly negative influence on Indian seafood exports to developed countries. As discussed earlier, an increasing population can indicate larger domestic markets and, consequently, less reliance on trade. With respect to the population of trading partners variable, Table 5 shows that the variable positively affects seafood exports from China and Indonesia.

The trade agreement variable negatively affects seafood exports from Indonesia, Morocco, and Vietnam to developed countries. This result is possible since tariff exemptions created by trade agreements do not guarantee a freer trade flow, especially for edible products (Rao et al., 2021). Most exporters still need to comply with several product standards. Additionally, these standards can sometimes act as a trade barrier.

The real exchange rate variable statistically positively affects seafood exports from Chile, India, and Indonesia. The estimated elasticity values fall between 0.643 and 1.107, suggesting that Chile, India, and Indonesia benefit from a devaluation of their currency. In short, the seafood product prices of these exporters tend to be lower in the eyes of importers (Asche, 2014).

Table 5 indicates that the impacts of the global financial crisis and COVID-19 crisis variables on seafood exports from the selected countries to developed nations vary. For example, the global financial crisis negatively affected seafood exports for China, India, Indonesia, and Thailand, while it positively affected Chile and Morocco. The COVID-19 crisis statistically and negatively affected seafood exports for Chile, China, Indonesia, and Thailand but positively affected seafood exports for India and Russia. The crisis led to both positive and negative effects on trade. Panic buying of food products increased exports for countries with less stringent lockdown measures than for their competitors in global markets (Dong & Truong, 2022; Hayakawa & Mukunoki, 2021). With respect to the control variables associated with macroeconomic factors, Table 5 indicates that the control of corruption index variable positively affects Russian and Vietnamese seafood exports to developed countries but negatively affects Indian, Moroccan, and Thai seafood exports to the same destinations. Moreover, the government effectiveness index has negative impacts on the seafood exports of several exporters, such as Chile, China, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Specifically, the negative impact of governance variables (i.e., control of corruption and government effectiveness indices) on economic growth is observed in developing countries. Developing countries sometimes prioritize expanding their economy over improving their governance (Mongi & Saidi, 2023). This implies that economic growth in developing countries may stem from existing political risks (Zhuo et al., 2021).

The impact of value chain upgrading on seafood exports from the selected countries to developing countries

Focusing on the south-to-south trade pattern, Section “The impact of value chain upgrading on seafood exports from the selected countries to developing countries” presents the estimation results of the effects of EUP and SUP on seafood products exported from the selected countries to developing countries. The EUP and SUP variables have varying effects on seafood exports (Table 6). That is, product upgrading positively affects seafood exports for Chile, China, India, Morocco, Thailand, and Vietnam, with the estimated semi-elasticities ranging from 0.0003 to 0.003. These results align with the findings of the effect of product upgrading on traded seafood products from the selected countries to developed countries. These results also support the findings of Humphrey and Schmitz (2002). That is, product upgrading is crucial for survival within agri-food value chains.

Table 6 also presents mixed results regarding the effect of process upgrading on traded seafood. Specifically, process upgrading positively affects Russian seafood exports and negatively affects Vietnamese seafood exports. Focusing on the lagged variable of process upgrading, Table 6 shows that the lagged variable positively affects Chinese and Russian seafood exports. In contrast, the lagged variable of process upgrading negatively affects Moroccan, Thai, and Vietnamese seafood exports. Compared with the results in Table 5, process upgrading often has a negative impact on seafood exports from the selected countries to developing countries.

The results also present both positive and negative effects of functional upgrading on seafood exports. Specifically, functional upgrading positively affects Chinese and Moroccan seafood exports, whereas this variable negatively affects Indonesian, Russian, and Vietnamese seafood exports to the same destination. Additionally, the results show that the lagged variable of functional upgrading positively affects Russian seafood exports and negatively affects Vietnamese seafood exports. As discussed by Chen et al. (2019) and Yan et al. (2023), the effect of OFDI on the home country’s economy varies, depending on relevant factors (i.e., economic conditions and productive sectors). Social upgrading significantly and positively affects Russia’s and Vietnam’s seafood exports. However, the social upgrading variable does not have a significant effect on the seafood exports of other selected exporters.

A comparison of the findings in Tables 5 and 6 reveals that the process, functional, and social upgrading variables have less of an impact on seafood exports to developing countries than on seafood exports to developed countries. Moreover, process and functional upgrading often have a negative effect on seafood exports to developing countries. These findings align with the results of Barrientos et al. (2011), Barrientos et al. (2015), and Rossi (2013). Buyers in developing countries often pay less attention to EUP and SUP. Additionally, domestic markets in developing countries often pay attention to product prices rather than to stringent product standards.

For other regressors, the results indicate that China’s GDP positively affects the Chinese seafood exports of the selected exporters to developing countries. Conversely, the GDP variables for Morocco, Russia, and Vietnam negatively affect seafood exports to the same destinations. Table 6 also shows that the variable positively affects seafood exports from Indonesia, Morocco, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Table 6 suggests that the population variable significantly and positively affects seafood exports for Morocco and Vietnam. When the population of the trading partner variable is considered, it positively affects traded seafood for China. However, it negatively affects Chilean, Moroccan, Russian, and Vietnamese seafood exports.

The trade agreement variable negatively affects seafood exports from selected countries, such as Chile, Indonesia, and Thailand, to developing countries. Furthermore, the depreciation of the exchange rate results in an expansion of seafood exports from China, Thailand, and Vietnam. This result means that these exporters benefit from a devaluation of their currency, which allows them to expand their seafood exports to developing countries. In addition, Table 6 shows that the global financial crisis negatively affected Chinese and Russian seafood exports. In contrast, the variable had a positive effect on Moroccan and Vietnamese seafood exports to the same destinations. The COVID-19 variable negatively affected seafood exports from China, Morocco, and Vietnam. In contrast, this variable positively affected seafood exports from Russia to the same destinations. Table 6 also shows that the control of corruption variable positively affects seafood exports from Chile, China, Russia, and Vietnam to developed countries. However, it also negatively affects seafood exports from Morocco and Thailand to the same destinations. Additionally, the government effectiveness variable has negative impacts on seafood exports from China, Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam, whereas it positively affects seafood exports from Morocco.

Summary and policy implications

This study empirically investigates the effects of EUP and SUP on seafood exports from the selected developing countries. The key results show that each type of upgrading has different effects on seafood exports. More specifically, the product upgrading variable positively affects seafood exports from the chosen exporters to developed and developing countries. However, other types of upgrading have less impact on seafood exports to developing countries than those exports to developed countries. This study also yields mixed findings when considering the impact of other types of upgrading on the seafood exports of the selected developing countries. For example, process upgrading negatively affects exported seafood from Chile and China due to shifted production costs in compliance with global standards. Process upgrading and its lagged variables significantly and positively affect seafood exports for Russia. This study also highlights mixed results regarding the effects of the functional upgrading variable on seafood exports from the selected countries. In addition, the social upgrading variable significantly affected seafood exports, especially to developed countries. It is also found that the selected exporters experience both positive and negative effects of social upgrading on their seafood exports, especially to developed countries. Specifically, social upgrading can increase the product costs of seafood exporters, leading to decreased export competitiveness in world markets.

This study’s results suggest some key policies. First, it is recommended that product upgrading be prioritized as a fundamental strategy to increase seafood exports for the selected exporters. For example, producers and exporters should create more sophisticated products rather than simple products for export. Additionally, both the government and private sectors should increase their focus on factors that support product upgrading, such as investing more in research and development (Kowalski et al., 2015). Process upgrading could have positive and negative impacts on seafood exports from the selected exporters. Importantly, policies supporting process upgrading are still necessary. For instance, governments should offer adequate financial support to private firms for process upgrading (Kowalski et al., 2015). Private sectors should also consider the potential negative impacts of process upgrading on seafood exports. The reason is that this type of upgrading may lead to increasing production costs and, subsequently, to decreased competition in world markets. Furthermore, both the government and private sectors should carefully develop policies that support functional upgrading for seafood exports. The reason is that functional upgrading is found to be both significantly positive and negative for the seafood exports of certain exporters. In contrast, it is nonsignificant for other countries, such as India and China. The effectiveness and efficiency of policies that support functional upgrading must be carefully considered. The government and private sectors should focus more on SUP when exporting seafood products to developed countries. Specifically, private firms need to be aware of the negative impact of SUP on seafood exports due to higher production costs, such as higher wages. Governments could implement support programs for private firms to help them maintain their competitiveness in global seafood markets. Critically, the policies above should be thoroughly evaluated for their impact before implementation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

According to the literature, the exact effects of these two indicators on the index calculation are inconclusive. Thus, Bernhardt and Milberg (2011) state that the use of equally weighted impacts is a good start for the calculation, rather than unequally weighted impacts.

References

Asche, F (2014) Exchange rates and the seafood trade. Available via https://www.fao.org/3/bb216e/bb216e.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2023

Athukorala PC (2012) Asian trade flows. Trends, patterns prospects Jpn World Econ 24(2):150–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2012.01.003

Baldwin, R (2014) Trade and industrialization after globalization’s second unbundling: How building and joining a supply chain are different and why it matters. In: Feenstra, RC, Tayler, AM (Eds) Globalization in an age of crisis: Multilateral economic cooperation in the twenty-first century. University of Chicago Press, p 165–214

Barrientos S, Gereffi G, Rossi A (2011) Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. Int Labour Rev 150(3-4):319–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2011.00119.x

Barrientos S, Knorringa P, Evers B, Visser M, Opondo M (2015) Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture. Environ Plan A 48(7):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15614416

Baylis K, Nogueira L, Pace K (2010) Food import refusals: Evidence from the European Union. Am J Agric Econ 93(2):566–572. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaq149

Bensassi S, Márquez-Ramos L, Martínez-Zarzoso I et al. (2015) Relationship between logistics infrastructure and trade: Evidence from Spanish regional exports. Transport Res Part A 72:47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2014.11.007

Bernhardt, T, Milberg, W (2011) Economic and social upgrading in global value chain: Analysis of horticulture, apparel, tourism and mobile telephones. Available via www.capturingthegains.org/publications/workingpapers/wp_201106.htm. Accessed 30 July 2023

Bernhardt T, Pollak R (2016) Economic and social upgrading dynamics in global manufacturing value chains: A comparative analysis. Environ Plan A: Econ Space 48(7):1220–1243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15614683

CEPII (2022) CEPII gravity dataset. https://www.cepii.fr/. Accessed 5 May 2023

Chen T, Lin G, Yabe M (2019) Impact of outward FDI on firms’ productivity over the food industry: Evidence from China. China Agric Econ Rev 11(4):655–671. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2017-0246

Cojocaru AL, Liuy Y, Smithz MD et al. (2022) The “seafood” system: Aquatic foods, food security, and the global south. Rev Environ Econ Policy 16(2):306–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/721032

Curzi D, Pacca L (2015) Price, quality and trade costs in the food sector. Food Policy 55:147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.06.007

Dong, CV, Truong, HQ (2022) Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international trade in developing countries: Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-09-2021-1395

Eegunjobi, R, Ngepah, N (2022) The determinants of global value chain participation in developing seafood-exporting countries. Fishes, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7040186

FAO (2022) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Towards Blue Transformation. Available via https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/11a4abd8-4e09-4bef-9c12-900fb4605a02. Accessed 10 July 2023

Hayakawa K, Mukunoki H (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on international trade: Evidence from the first shock. J Jpn Int Econ 60:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2021.101135

Head K, Mayer T (2010) Gravity, market potential and economic development. J Econ Geogr 11(2):281–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq037

Humphrey J, Schmitz H (2002) How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Region Stud 36(9):1017–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000022198

Jongwanich J (2009) Impact of food safety standards on processed food exports from developing countries. Food Policy 34(5):447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2009.05.004

Jongwanich J (2020) Export diversification, margins and economic growth at industrial level: Evidence from Thailand. World Econ 43(10):2674–2722. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12921

Kadfak, A, Linke, S (2021) More than just a carding system: Labour implications of the EU’s illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing policy in Thailand. Marine Policy 27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104445

Kaplinsky R, Readman J (2005) Globalization and upgrading: What can (and cannot) be learnt from international trade statistics in the wood furniture sector? Ind Corp Change 14(4):679–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dth065

Khandelwal A, Schott PK, Wei SJ (2013) Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: Evidence from Chinese exporters. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2169–2195. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2169

Kowalski, P, Gonzalez, JL, Ragoussis, A et al. (2015) Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies. OECD Trade Policy Papers. https://doi.org/10.1787/5js33lfw0xxn-en

Lin CF (2016) Does Chinese OFDI really promote export? China Financ Econ Rev 4(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40589-016-0037-8

Malcorps, W, Newton, RW, Maiolo, S et al. (2021) Global seafood trade: Insights in sustainability messaging and claims of the major producing and consuming regions. Sustainability 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111720

Milberg W, Winkler D (2011) Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: Problems of theory and measurement. Int Labour Rev 150(3-4):341–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2011.00120.x

Mongi, C, Saidi, K (2023) The impact of corruption, government effectiveness, FDI, and GFC on economic growth: New evidence from global panel of 48 middle‑income countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01509-0

Natale F, Borrello A, Motova A (2015) Analysis of the determinants of international seafood trade using a gravity model. Mar Policy 60:98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.05.016

OECD-UNIDO (2019) Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in global value chains: Enabling linkages with foreign investors. Available via https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/integrating-southeast-asian-smes-in-global-value-chains-enabling-linkages-with-foreign-investors_016ecfa0-en. Accessed 10 July 2023

Pahl S, Timmer MP (2020) Do global value chains enhance economic upgrading? A long view. J Dev Stud 56(9):1683–1705. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1702159

Pananond P (2012) Moving along the value chain: Emerging Thai multinationals in globally integrated industries. Asian Bus Manag 12(1):85–114. https://doi.org/10.1057/abm.2012.30

Papazoglou C (2007) Greece’s potential trade flows: A gravity model approach. Int Adv Econ Res 13(4):403–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-007-9107-x

Ponte S, Ewert J (2009) Which way is “up” in upgrading? Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Dev 37(10):1637–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.03.008

Ponte, S, Kelling, I, Jespersen, KS et al. (2014) The blue revolution in Asia: Upgrading and governance in aquaculture value chains. World Development, 64: 52-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.022

Rao M, Bast A, de Boer A (2021) European private food safety standards in global agri-food supply chains: A systematic review. Int Food Agribus Manag Rev 24(5):1–16. https://doi.org/10.22434/IFAMR2020.0146

Rossi A (2013) Does economic upgrading lead to social upgrading in global production networks? Evidence from Morocco. World Dev 46:223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.02.002

Santos Silva JMC, Tenreyro S (2006) The log of gravity. Rev Econ Stat 88(4):641–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.641

Santos Silva JMC, Tenreyro S (2011) Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Econ Lett 112(2):220–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.05.008

Santos Silva JMC, Tenreyro S (2022) The Log of Gravity at 15. Portuguese Econ J 21:423–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-021-00203-w

Staub KE, Winkelmann R (2013) Consistent estimation of zero-inflated count models. Health Econ 22(6):673–686. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2844

Suanin W (2022) Processed food exports from developing countries: The effect of food safety compliance. Eur Rev Agric Econ 50(2):743–770. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbac030

The United Nations (2022) World Economic Situation and Prospects 2022. Available via https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-2022/. Accessed 20 July 2023

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2022) Import Refusal Report. Available via https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/importrefusals/. Accessed 15 July 2023

Thuong, NTT (2017) The effect of Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures on Vietnam’s rice exports. EconomiA. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econ.2017.12.001

Wongrak G, Hur N, Pyo I, Kim J (2021) The impact of the EU IUU regulation on the sustainability of the Thai fishing industry. Sustainability 13:6814–6830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126814

World Bank (2022) World Development Indicator. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators. Accessed 10 June 2023

World Customs Organization (2017) HS Nomenclature 2017 edition. https://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/nomenclature/instrument-and-tools/hs-nomenclature-2017-edition/hs-nomenclature-2017-edition.aspx. Accessed 28 Jan 2025

Yan Z, Sui S, Wu F et al. (2023) The impact of outward foreign direct investment on product quality and export: Evidence from China. Sustainability 15(4227):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1505422

Yang B, Anderson JL (2020) Determinants of China’s Seafood Trade Patterns. Mar Resour Econ 35(2):97–112. https://doi.org/10.1086/708617

Zhuo Z, Musaad OAS, Muhammad B et al. (2021) Underlying the relationship between governance and economic growth in developed countries. J Knowl Econ 12:1314–1330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-020-00658-w

Acknowledgements

I thank Professor Archanun Kohpaiboon and Assistant Professor Pasakorn Thammachote for his helpful suggestions. I also thank the Faculty of Economics, Kasetsart University for providing the research funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The single author takes full responsibility for all aspects of the research and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanrattanaphong, B. Value chain upgrading and seafood exports: lessons from developing countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04790-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04790-3