Abstract

Plenty of research has been done to examine the influence of corporate marketing activities on consumer behavior; however, less attention is paid to exploring the childhood experience that shapes consumers’ donation intention. Most charitable organizations always view donations as a one-off effect, but charitable donation is a sustainable event resulting from childhood influence. Drawing on imprinting theory, this article deeply explores how perceived social support in childhood affects consumers’ willingness to donate, and further, is empirically tested utilizing a survey method. Prosocial motivation and perspective taking are first introduced to construct a chain mediating model to explain the relationship between consumers’ perceived social support in childhood and donation intention in adulthood. This paper concludes with discussions on the implications of theory, research, and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Charitable giving represents a complex social behavior influenced by multiple psychological and environmental factors. While existing research has extensively examined corporate influences on donation behavior (Shang et al. 2020), a critical gap remains in understanding how early life experiences influence enduring philanthropic tendencies. This research breaks new ground by applying Imprinting Theory to reveal how childhood perceived social support creates lasting cognitive frameworks that influence adult donation behavior through a novel dual-mediation pathway.

Perceived social support is of great value in the field of marketing. Whether and how much social support is obtained will have an important impact on consumer behaviors, enterprise activities, and social development (Zhu et al. 2016). It was confirmed that consumer perceived social support enhanced recognition of enterprises by reducing perceived risks, thus triggering consumers’ purchase behaviors (Rosenbaum and Massiah, 2007). Based on the research background of virtual brand community, scholars unveiled that consumer perceived social support can actively foster customer trust and further enhance consumers’ willingness to share knowledge (Wang et al. 2014). Thus, there is sufficient evidence to confirm that perceived social support has a positive effect in the realm of marketing.

Traditional approaches to understand donation behavior have primarily focused on contemporaneous factors such as demographic variables (Brown and Ferris, 2007), organizational characteristics (Graddy and Wang, 2009), or marketing stimuli (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011; Hahn and Gawronski, 2015). Nonetheless, these perspectives fail to account for the developmental origins of prosocial tendencies. Our study addresses this gap by introducing childhood perceived social support as a formative imprint that persists into adulthood, offering a longitudinal perspective absent in current literature.

Early experience is a double-edged sword for individual development. Previous studies have focused on the traumatic “imprint” of childhood adversity (Xu and Ma, 2022; Tian et al. 2022), whereas positive and warm experiences cannot be ignored. Practically, China has succeeded in eliminating poverty and building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. With a decline in the probability of unfortunate experiences such as famine, poverty, and abuse, more and more families have become aware of creating a warm and positive environment for the growth of their children and are able to do so. The existing research literature on charitable donation has paid less attention to the relationship between early positive experience and donation intention. However, perceived social support in childhood can deliver positive energy, improve mood and shape behavior (Zahodne et al. 2019). Therefore, this study fills this gap by investigating the role of perceived social support in childhood in promoting willingness to donate among consumers. Consumers who feel more social support in childhood tend to have a healthier mentality and a more optimistic lifestyle, which makes a difference in their performance and results in the process of public welfare consumption (Jin et al. 2020). On this basis, it is explored in this study whether consumers’ perceived social support in childhood influences their charitable donation intention, what influence it has, and its underlying mechanism.

This study aims to fill the gaps in the preceding literature on perceived social support in childhood and donation intention by addressing two significant research questions: (i) What is the relationship between perceived social support in childhood and donation intention, and how do prosocial motivation and perspective taking influence these dynamics? and (ii) How are social marketing strategies utilized in these charities to enhance consumers’ perceived social support in childhood?

The theoretical foundation of this study rests on three innovative premises. First of all, this research extends Imprinting Theory beyond its conventional application to traumatic experiences by presenting how positive childhood environments create lasting cognitive frameworks that guide prosocial behavior. Secondly, a previously unrecognized sequential mediation pathway is identified: childhood perceived social support fosters prosocial motivation, enhances perspective taking, and ultimately promotes donation intention. This chain mechanism provides a more nuanced understanding than existing single-mediator models. Thirdly, this study bridges developmental psychology and consumer behavior by demonstrating how early positive experiences manifest in specific marketplace behaviors decades later.

This research offers a fundamentally new perspective on donation behavior by shifting focus from immediate situational factors to developmental antecedents. The findings challenge conventional marketing approaches that emphasize transactional benefits, instead highlighting the deep psychological roots of generosity. This understanding opens new avenues for both theoretical development and practical intervention in the domain of prosocial consumer behavior.

Literature review and hypotheses

Theoretical basis and literature review

Imprinting theory

It was in the late 19th century that the concept of imprinting was first raised in the study of animal behavior. In 1965, Stinchcombe proposed the concept of imprinting into the study of organizations, laying emphasis on the significance and continuity of external environmental forces in shaping the initial structure of enterprises. According to the Imprinting Theory, the experience of the subject forms the “imprint” that matches the environment, and it exerts influence on the subject even if the environment changes in the later period (Marquis and Tilcsik, 2013). There are three main characteristics of imprinting. Firstly, imprinting occurs in a certain sensitive period. Secondly, the core characteristics of the environment influence the focal entity significantly during the sensitive period. Lastly, the imprinting process has persistent effects.

In recent years, there have been more and more scholars applying Imprinting Theory to explain behavior at the individual level. In plenty of studies, it has been explored how childhood adversity or traumatic experiences relate to individual cognition, behavior patterns, and outcomes in adulthood (Xu and Ma, 2022). Currently, the emphasis is placed more on revealing the negative influence of early unfortunate experiences on individuals, from such perspectives as mental health (McLaughlin et al. 2010), personality development (Rosenman and Rodgers, 2006), and employment performance (Churchill et al. 2021). Critically, the three imprinting characteristics—critical period sensitivity, environmental determinism, and persistence—provide a theoretical anchor for this core construct (childhood perceived social support). Firstly, ages 5–15 represent a biologically recognized sensitive period for social cognition development. Secondly, family/school environments during this period fundamentally shape perceived social support (Zimet et al. 1988). Thirdly, imprinted perceived social support persists into adulthood, as evidenced by the longitudinal mediation model. Therefore, Imprinting Theory not only justifies studying childhood antecedents but also explains why perceived social support exerts enduring effects beyond contemporaneous factors.

Charitable donation intention

Scholars in different fields define charitable donation intention differently. As argued by Baston (1991) and Bendapudi et al. (1996), the intention of charitable donation can be defined as the inclination to donate money or goods to individuals or non-profit organizations with no interest.

The research on charitable donation intention focuses mainly on the influencing factors and motivations. However, there remains a lack of a unified conclusion reached on the influencing factors of individual donation intention, mainly due to the different disciplines of researchers. Besides, there are also differences in the theories applied to explain donation behavior. At present, the influencing factors of individual charitable donation mainly involve the characteristics of donors, recipients, charities and social environment. Scholars have studied demographic variables to discover that the donors who have a higher income, are older, are more educated, and are religious have a strong explanatory power on individual donation intention (Brown and Ferris, 2007). Secondly, the personality traits of agreeability (Bekkers, 2006) and empathy (Verhaert and Van den Poel, 2016) show a positive correlation with charitable donation intention and behavior. Thirdly, it is considered by scholars that donation is influenced by the organizational characteristics of charities, such as establishment time (Graddy and Wang, 2009), information disclosure mechanism, and organizational efficiency (Warwick, 2011). In addition, it is suggested by scholars that charitable donation is closely associated with the culture of a country (Wang and Graddy, 2008). Regardless of the perspective taken to examine the influencing factors in individual donation intention, it has been confirmed by many scholars that marketing plays an important role in these research results. Meanwhile, there remains a lack of research on how donation intention is influenced by childhood experiences.

On the other hand, Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) reviewed more than 500 studies on individual donation behavior to identify eight motivations of individual donors, which are the awareness of need (Bekkers, 2008), solicitation (Bekkers, 2005; Gneezy and List, 2006), costs and benefits (Karlan and List, 2007), altruism (Soetevent, 2005), reputation (Bateson et al. 2006), psychological benefits (Tankersley et al. 2007), values (Bekkers, 2007; Fong, 2007), and effectiveness (Bekkers, 2006; Smith and McSweeney, 2007). Although many scholars have studied each single motivation, the phenomenon of compound motivation still exists in real life. In recent years, the research on individual donation has become increasingly important as individual public welfare develops and an atmosphere of moral consumption is created.

While prior studies have extensively examined the effect of childhood adversity in shaping donation behavior (Kraus et al. 2013), three critical gaps remain. Firstly, the focus has predominantly been on negative childhood experiences, with limited attention to the effects of positive experiences, such as perceived social support. Secondly, the mechanisms linking childhood experiences to donation intention are underexplored, particularly the roles of prosocial motivation and perspective taking. Thirdly, most studies have relied on corporate or celebrity donation data, neglecting individual-level psychological processes. This research addresses these gaps by investigating how perceived social support in childhood (a positive experience) shapes donation intention through a chain mediation model involving prosocial motivation and perspective taking, as shown in Table 1.

Research hypothesis

Perceived social support in childhood and consumers’ donation intention

In the field of social psychology, it is widely recognized that the behavior of individuals is closely related to their early life experiences, especially childhood experiences. Childhood is the stage in which an individual's thinking mode is shaped and values are cultivated. The cultivation of individual quality is profoundly influenced by various childhood experiences (Elder et al. 1991). According to Imprinting Theory, the imprint formed by some important experiences of individuals in childhood has a persistent influence on their ideas and behaviors in adulthood. At the same time, the social exchange theory holds that those individuals with high perceived social support are inclined to repay society by taking positive behaviors (Lenzi et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2021). When consumers perceive that society is trying to give them positive experiences in their childhood, they, as adults, stimulate a stronger sense of responsibility and exhibit more positive behaviors voluntarily for social development. As a psychological coping resource, perceived social support plays an important role in motivating the charitable behavior of individuals (Wentzel, 2003). Therefore, the consumers receiving more care in childhood take an optimistic attitude towards life, which leads to more positive emotional reactions while enhancing charitable donation willingness. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Consumers’ perceived social support in childhood will positively influence their intention to donate.

Mediating effect of prosocial motivation

According to social exchange theory, individuals receive care, information and services from the outside world, and return similar resources to others based on the feeling of gratitude and the principle of reciprocity. As a kind of protective resource from the outside world, social support provides individuals with spiritual energy continuously, maintains their physical and mental health, and ultimately influences their behavior (Hobfoll et al. 1990). As indicated by Marquis and Tilcsik (2013), individuals can be taught by precept and example under the influence of the behavior of “role models” and “peers” from family structure, campus environment, and peer relationships in childhood, which shapes a more prosocial personality trait. Therefore, the consumers with high perceived social support in childhood tend to have stronger prosocial motivation and are keener to help others through efforts in their subsequent life.

As an other-focused motivation, prosocial motivation can translate into a series of positive behavioral manifestations. For example, it is shown by the empirical studies on college students that prosocial motivation exerts a positive influence on online helping behaviors (Cadenhead and Richman, 1996) and altruistic behaviors (Tsang, 2006). According to the theory of motivational information processing, those driven by prosocial motivation pay more attention to the information processing related to the interests of others (Grant and Berry, 2011). On the one hand, prosocial motivation is regarded as an other-focused psychological process, which means individuals turn their attention to helping others, and then make efforts to fulfill the desire to help others (Grant, 2007; Grant and Berry, 2011). On the other hand, prosocial motivation is viewed as a psychological state that directs individuals to act in the interest of others (De Dreu, 2006; Grant, 2007; Grant and Berry, 2011).

On this basis, it is contended in this paper that the social support perceived by consumers in childhood can improve the level of prosocial motivation in adulthood, thus prompting individuals to consider the interests of others and enhancing the willingness of consumers to donate to charity. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Consumers’ prosocial motivation strengthens the association between perceived social support in childhood and individual donation intention.

Mediating effect of perspective taking

There is a close relationship between perceived social support and empathy. When individuals experience more perceived social support, their empathy abilities are stronger (Leppma and Young, 2016). Empathy and perspective-taking are two concepts that influence each other. The cognitive effort of perspective taking usually leads to empathy (Vescio et al. 2003), while empathy leads to people’s perspective taking (Vorauer and Sasaki, 2009). Therefore, it is more likely that the consumers receiving more external support in the early stage of growth engage in perspective taking during consumption.

According to empirical studies, the understanding of others’ opinions and emotions (i.e. perspective taking) by an individual has a significant influence on his or her decision-making and prosocial behaviors Hodges et al. 2010). The individuals with a strong ability of perspective taking tend to pay attention to others for better understanding their thoughts and emotions, which motivates donation behavior (Barret and Yarrow, 1977; Eisenberg and Miller, 1987). Therefore, the willingness of an individual to donate is affected by the ability of donors to choose opinions (Aron et al. 1992). When paying attention to and understanding others’ opinions and feelings, individuals are more willing to donate.

In conclusion, it is proposed in this paper that consumers’ perceived social support in childhood can lead to a higher level of perspective taking in later years, which promotes the behavior of helping others and enhances the willingness of consumers to donate. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Consumers’ perspective-taking strengthens the association between perceived social support in childhood and individual donation intention.

Chain mediating effect of prosocial motivation and perspective taking

According to the theory of motivational information processing, individuals with stronger prosocial motivation pay more attention to the information about the well-being of others when they process information (Grant and Berry, 2011), which enables them to overcome the limitations of their own perspective and take the perspectives of others (Škerlava et al. 2018). Thus, they exhibit positive behaviors. As confirmed by the studies in relation to psychology and management, prosocially motivated individuals are more likely to consider the views of a range of others around them (Parker and Axtell, 2001; Grant and Berry, 2011). Meanwhile, perspective taking as a key information processing mechanism to drive individual behaviors enables an individual to concern and understand the feelings and views of others from their perspectives, thus actuating them to effectively help others (Galinsky et al. 2008). Despite the variation in the tendency of individuals to adopt opinions, existing studies demonstrate that the change of individual motivation affects the effort to accept others’ opinions in a specific situation and environment (De Dreu et al. 2000; Grant and Berry, 2011). Therefore, it is through prosocial motivation that consumers’ perceived social support in childhood promotes the perspective-taking behavior of individuals, which encourages them to donate. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Consumers’ prosocial motivation and perspective taking play a chain mediating role in the effect of perceived social support in childhood on individual donation intention.

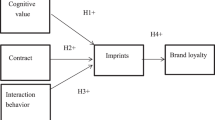

Finally, a research model is constructed in this study, as shown in Fig. 1.

Methods

Variable measurement

In this paper, the questionnaire method was used to collect relevant data. The designed questionnaire consists of three parts. In the first part, the questionnaire was introduced to the respondents to clarify the purposes of this study, and their participation was acknowledged. In the second part, a Likert scale anchored at 1 (disagree strongly) and 7 (agree strongly) was adopted to test the perceived social support in childhood, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and charitable donation intention. In the last part, an investigation was conducted into the personal information of the sample, including age, gender, education, occupation, discretionary consumption amounts monthly, and whether they were the only child.

Charitable donation intention (DI)

The donation intention scale was developed by Hou (2009), which refers to plenty of domestic and foreign literature and opinions. It has been recognized and applied by many scholars with high reliability and validity. There are four items, such as “I am willing to donate to my selected charitable organizations” and so on.

Perceived social support in childhood (PSS)

Perceived social support refers to the subjective evaluation and perception of external support by an individual (Zimet et al. 1988). In this paper, the multidimensional scale of perceived social support (MSPSS) was applied to measure the perceived social support in childhood (Zimet et al. 1988), which has been validated in Chinese populations and extensively used in studies involving Chinese participants. It involves three dimensions that can be used to evaluate the social support received from family, friends and other important people, respectively, encompassing a total of 12 items, such as “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” and so on. On the specific operational level, this study ensured that the measured variable was perceived social support in childhood by adding the pre-description “Please recall the care you received during your childhood (5–15 years old)”.

Prosocial motivation (PM)

Contrary to self-interested motivation, prosocial motivation is defined as the desire to make efforts to help others or make contributions to others (Grant, 2007). In this paper, the scale developed by Grant (2008) was applied to change the subject of the scale from employees to consumers. Additionally, the context was changed from the workplace to the donation context. The scale covers four items, such as “I care about benefiting others through my donation” and so on.

Perspective taking (PT)

Perspective taking is the ability of an individual to differentiate his or her own view from that of others, and to consider problems and understand the world from the perspectives of others (Parker and Axtell, 2001). This research adopts the interpersonal reactivity index-C (IRI-C) developed by Zhang et al. (2010), which encompasses perspective taking, fantasy, empathetic concern and personal distress. IRI-C was revised from the interpersonal reactivity index (IRI) (Davis, 1980) for the Chinese environment and reduced from 28 items to 22 items. There are five items about perspective taking used in this paper, such as “In the donation, I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision” and so on.

Control variables

In order to avoid the influence of demographic characteristics on the existence of the main effect in this study, we controlled the age, gender, education, and occupation. This study takes into account that an individual’s discretionary income monthly affects his/her willingness to donate, so we controlled the discretionary income monthly (the term “discretionary income” in the tables). The term “residence” intends to investigate whether the respondents lived in the city or the country. Urban residents and rural residents have certain differences in consumption capacity and consumption content, so we controlled the residence. The term “family structure” intends to investigate whether the respondents come from single-parent families or not. The family environment has an influence on individual prosocial behavior, so we controlled the family structure. Variables such as residence and family structure were controlled due to their documented associations with prosocial behavior and access to perceived social support. The term “one-child” intends to survey whether respondents are the only child in their families. The quantity of children is related to the prosocial behavior through the parental investment and socialization patterns, so we controlled this variable. By controlling for these variables, it is able to reduce the possibility that they would impact the result.

Data collection and descriptive statistics

Based on the feasibility perspective, the survey was conducted in China using the online platform Questionnaire Star, which is accessible nationwide and ensures representation from diverse geographic and socioeconomic backgrounds. Data were collected through social media platforms such as WeChat and QQ, which are widely used across all provinces in China. This study adopted a cross-sectional survey design. Participants were invited on WeChat and QQ, among China’s most popular social media platforms, with over 1 billion and 500 million active users, respectively. The invitation included a brief introduction to the study’s purpose and a link to the questionnaire. Respondents were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous. To guarantee the rigor of the survey, the data collection is divided into two stages: the pre-survey and the formal survey. Firstly, a pre-survey was conducted to assist participants in exactly understanding the questions in the formal survey phase. This phase collected 63 questionnaires through Questionnaire Star, with 51 valid questionnaires. Then, the questionnaire was revised to account for the reliability and validity of the results. The second stage was the formal survey. Through a one-month online questionnaire (from October 13, 2023, to November 10, 2023), a total of 480 questionnaires were collected, of which 340 valid questionnaires (n = 340) were finally obtained after removal of the questionnaires with incomplete information, unclear relevant matching, and too many consistent options. The questionnaire’s effective rate of collection was 70.8%. In this survey, 45.3% of the covered samples were male and 54.7% female. By age, their proportions are as follows: 30.6% is 18–25 years old, 25.0% is 26–35 years old, 26.8% is 36–45 years old, 15.0% is 46–55 years old, and last 2.6% is 56 years old or over. Their education levels are as follows: 33.8% is junior college or below, 49.4% is a bachelor’s degree, 12.6% is a master’s degree, and 4.1% is a doctoral degree or above. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2.

The sample spanned 13 provincial-level regions, capturing socioeconomic diversity across China as shown in Table 3. Core Economic Zones (Yangtze River Delta, YRD) dominated 49.5%, which was consistent with China’s population concentration in eastern coastal regions. Western/Inland Representation included Chongqing (11.2%), Sichuan (4.1%), Hubei (2.9%), and Jiangxi (1.4%), which reflected the inclusivity of less-developed areas.

Reliability and validity analysis

In this study, Cronbach’s α was used as an evaluation criterion for the reliability of the measurement question items. As shown in Table 4, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of the variables of perceived social support in childhood (PSS), prosocial motivation (PM), perspective taking (PT) and charitable donation intention (DI) exceed 0.8, indicating the high reliability of all scales and their suitability for subsequent data test.

SPSS 26.0 was used to conduct validity analysis. The KMO value of perceived social support in childhood (PSS) is 0.967, which is significant according to the Bartlett test (p < 0.001). The KMO value of prosocial motivation (PM) is 0.816, which is significant according to the Bartlett test (p < 0.001). The KMO value of perspective taking (PT) is 0.873, which is significant according to the Bartlett test (p < 0.001). The KMO value of donation intention (DI) is 0.817, which is significant according to the Bartlett test (p < 0.001). Therefore, the questionnaire used in this study is verified as valid, and the explanation of each item on the variables is considered reasonable.

At the level of convergent validity, as shown in Table 4, the factor loading coefficient estimate for each item is greater than 0.5, and the combined reliability (CR) of each variable is greater than 0.8, as well as the average variance extracted value (AVE) exceeds 0.5. This indicates that the convergent validity of all the items in this study is good. As shown in Table 4 in terms of discriminant validity, the correlation coefficients between the variables are lower than the square root of AVE. This indicates the discriminant validity of all the measurement items in this study is good. Therefore, the questionnaire is well designed and the items have excellent reliability and validity.

Common method bias and collinearity analysis

In order to control the common method bias, anonymous evaluation and hidden variable names were adopted in this study for issuing questionnaires. Since all variables were measured through a self-assessment questionnaire, Harman’s single-factor analysis was conducted to detect common method bias. Also, exploratory factor analysis was performed on all variables, with 4 factors found to have a higher initial eigenvalue than 1. The overall explanation rate of these 4 factors for the variables was 66.61%, and the explanation rate of the first factor was 39.66%, which was less than 40%. That is to say, there is no serious common method bias in the questionnaire data used in this paper. To facilitate the collinearity diagnosis of childhood perceived social support, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and donation intention, the VIF is <2, which is far lower than the critical value of 10. It is indicated that there is no serious collinearity problem among the variables used in this study.

Data analysis and results

Correlations

Table 5 lists the results of the correlation analysis among the variables. It shows a significantly positive correlation between consumers’ perceived social support in childhood and the charitable donation intention of individuals. Also, there is a significantly positive correlation observed with prosocial motivation and perspective-taking. A significant positive correlation is present not only between prosocial motivation, opinion adoption, and charitable donation intention, but also between prosocial motivation and opinion taking.

Hypothesis testing

Main effect of perceived social support in childhood and consumers’ donation intention

In this paper, SPSS 26.0 was applied for multiple linear regression analysis. Firstly, as shown in Table 6, a range of control variables were introduced into Model 1, such as gender, age, education, one-child, occupation, discretionary income, residence, and family structure. Then, the perceived social support in childhood as an independent variable was factored into Model 2, as shown in Table 6. Compared to Model 1, the R2 in Model 2 increases significantly. Childhood perceived social support has a significant positive effect on individual charitable donation intention, whose standardized coefficient is 0.36. Also, the p-value of its regression factor test falls below 0.001 (β = 0.360, t = 7.088, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis H1 is supported.

Mediating effect of prosocial motivation and perspective taking

As shown in Table 7, the perceived social support in childhood has a significantly positive forecasting effect on prosocial motivation (β = 0.400, t = 7.918, p < 0.001). Also, the perceived social support in childhood has a significantly positive predictive effect on perspective taking (β = 0.379, t = 7.509, p < 0.001), and prosocial motivation has a significantly positive predictive effect on perspective taking (β = 0.318, t = 6.095, p < 0.001). When perceived social support in childhood, prosocial motivation, and perspective taking are added to the regression equation simultaneously, prosocial motivation (β = 0.170, t = 3.088, p < 0.01) and perspective taking (β = 0.243, t = 4.412, p < 0.001) have a positive predictive effect on charitable donation intention. The direct effect of perceived social support in childhood on charitable donation intention remains significant (β = 0.199, t = 3.686, p < 0.001), indicating a partial chain mediating role that prosocial motivation and perspective taking play in the effect of perceived social support in childhood on charitable donation intention.

Based on the study of Preacher and Hayes (2008), the Bootstrap method was used in this paper to verify the mediating effect. The plug-in unit PROCESS in SPSS 26.0 was used to select Model 6 for test on the chain mediating effect of prosocial motivation and perspective taking on the correlation between perceived social support in childhood and charitable donation intentions, with gender, age, education, one-child, occupation, discretionary income, residence, and family structure as control variables. As shown in Table 8 and Fig. 2, the total indirect effect of perceived social support in childhood on the charitable donation intention is significant, with a total indirect effect is 0.160, 95% CI [0.106, 0.217], SE is 0.284, and the ratio of the mediating effect to the total effect is 44.4%. Specifically, the mediating effect is decomposed into three indirect effects: childhood perceived social support → prosocial motivation → donation intention as the indirect effect 1 (0.068); childhood perceived social support → perspective taking → donation intention as the indirect effect 2 (0.061); and childhood perceived social support → prosocial motivation → perspective taking → donation intention as the indirect effect 3 (0.031). The mediating bootstrap 95% CI effect was estimated using 5000 samplings, and the mediation effect test was carried out. At the 95% CI, the results of the mediating effect of the three paths do not contain 0, indicating the significant level reached by the effects. Specifically, the indirect effect 1 accounts for 18.9% of the total effect, the indirect effect 2 accounts for 16.9% of the total effect, and the indirect effect 3 accounts for 8.6% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypotheses H2, H3, and H4 are all supported.

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusion

In this paper, the Imprinting Theory is applied to construct a chain mediation model in which consumers’ perceived social support in childhood exerts influence on the individual’s willingness to donate. Also, the developmental psychology and cognitive effects of positive childhood experiences on charitable donations are confirmed. Through empirical research, the following conclusions are drawn. (1) Consumers’ perceived social support in childhood has a significantly positive impact on the individual charitable donation intention; (2) Consumers’ prosocial motivation plays a mediating role in the positive effect of perceived social support in childhood on individual donation intention; (3) Consumers’ perspective taking mediates the effect of perceived social support in childhood on individual donation intention; (4) Consumers’ prosocial motivation and perspective taking play a chain mediating role in the effect of perceived social support in childhood on individual donation intention. These findings directly extend the Imprinting Theory, demonstrating how childhood perceived social support creates enduring cognitive frameworks that shape adult prosocial behavior, thus validating the theoretical anchor of this study.

Discussion

Based on the Imprinting Theory, this research adopted multiple linear regression analysis and the Bootstrap method to test the direct effect and chain mediating pathway of perceived social support in childhood on consumers’ willingness to donate. The results verify that perceived social support in childhood has a positive influence on consumers’ willingness to donate in adulthood, and this influence is transmitted sequentially through the two mediating variables of prosocial motivation and perspective taking.

First of all, the Imprinting Theory is applied to introduce a new predictor for the research on individual donation, indicating that consumers’ perceived social support in childhood has a positive effect on individual charitable donation intention. Previous studies have indicated that social support positively affects individual psychology and behavior (Ali and Mandurah, 2016; Guo, 2020; Fan and Fan, 2023). Because the availability of resources during childhood is a major factor affecting their attitudes and behaviors in adulthood, the environment in this period has a significant impact on individuals (Wang and Rao, 2015; Chen, 2024). This study further clarifies the relationship between perceived social support in childhood and specific prosocial behavior (donation intention). This empirical study has confirmed that perceived social support in childhood can enhance consumers’ willingness to donate in adulthood, providing more concrete evidence for the promotion of prosocial behavior by perceived social support. Secondly, prosocial motivation and perspective taking constitute the underlying psychological pathway for the influence of perceived social support in childhood on consumers’ donation intention. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory, the study emphasizes how perceived social support in childhood fosters a sense of reciprocity and gratitude, which translates into a sustained desire to benefit others. Meanwhile, childhood perceived social supports likely enhance empathy, enabling individuals to mentally stimulate others’ needs. Unlike most of the previous studies on consumer donation behavior where only a single mediating mechanism with limited explanatory power was demonstrated (Zhang and Liu, 2014; Liu et al. 2024), this paper reveals a chain mediating mechanism with different attributes: prosocial motivation and perspective taking. The findings enrich the understanding of the mechanism of social support affecting prosocial behavior and provide new ideas and directions for follow-up research. Thirdly, the research on how early positive experience influences individual behaviors is enriched. Prior studies focus mainly on the influence of individual childhood negative experiences on adulthood psychology and behavior (Kraus et al. 2013; Kish-Gephart and Campbell, 2015; Chen, 2024), though there is limited literature on childhood positive experiences. Some existing studies investigated the relationship between early positive experience and health status in adulthood (Bethell et al. 2019; Han et al. 2023), whereas the literature is scarce on individual behaviors. Focusing on the prosocial behavior of donation intention, this study provides support for the significant correlation between the positive experiences in early life and the prosocial behavior in adulthood.

While the Empathy-Altruism hypothesis (Batson, 1991) posits that situational empathy drives helping behavior, our study reveals that the capacity for empathy (e.g., perspective taking) may itself stem from childhood experience. This aligns with Social Cognitive Theory’s emphasis on early social learning but adds temporal specificity by identifying childhood as a critical period for prosocial trait formation. Importantly, unlike the Theory of Planned Behavior, which focuses on contemporaneous intentions, our model suggests that childhood imprints establish enduring motivational tendencies (prosocial motivation) that later interact with situational factors. This underscores the value of designing charity campaigns that activate childhood—support narratives—a strategy elaborated in the section “Managerial implications”. These findings extend Imprinting Theory by demonstrating that imprints are not merely ‘static traces’ but actively shape adult cognition through sequential mediation. Collectively, these theoretical advances offer actionable levels for practitioners seeking to cultivate sustained donor engagement.

Managerial implications

Building on the theoretical discussion, which positions childhood perceived social support as a scaffold for adult prosociality, this part proposes two evidence-based strategies. Firstly, non-profit organizations can utilize emotional marketing strategies to arouse consumers’ warm memories of childhood and emphasize the significance of social support. For example, charities can design campaigns like “Give the Support You Received”, featuring narratives of individuals recalling childhood moments of familial care and linking them to donate to children in need. Certainly, non-profit organizations, such as charitable organizations, should be active in guiding and caring for the growth of children during childhood and adolescence. Also, it is necessary to guide the elders to raise the younger generation in a more gentle and caring way through enough publicity and education done for families and schools. Secondly, charities need to design marketing campaigns to stimulate consumers’ prosocial motivations and cultivate the abilities of perspective taking. Specifically, consumers can perceive the positive impact of their behaviors on others and society through a connection established between individuals and donation events, which stimulates their prosocial motivation. At the same time, charities can carry out charity publicity and communication activities through offline scenes or online platforms. This improves consumers’ understanding of charity events, guides them to choose opinions, and promotes their participation in charitable donations.

Limitations and future research

Due to the limited cognition and resources, this paper is subject to the following limitations. Firstly, data collection has limitations. The sample size of this study is relatively small. While our use of online convenience sampling enabled efficient data collection, it may overrepresent urban, tech-savvy demographics. Secondly, many factors influence the effect of consumers’ perceived social support in childhood on donation intention. Although prosocial motivation and perspective taking are found to have a chain mediating effect, it is still insufficient to fully reveal the mechanism of childhood positive experience and individual donation. Especially, the research results show that the two only play a partial mediating role, which necessitates further exploration of other mechanisms in the future.

Future research could expand the sample size and geographical coverage, and consider including moderating variables in the model to deepen understanding of the pathways to improve donation intention. In addition, more moderator variables can be joined to investigate how cultural values or adulthood experience alter the imprinting effect. Recently, some scholars have proposed that the sustained impact of “imprinting” is not equal to the permanent effects (Simsek et al. 2015), and it may be changed due to continuous contact with contradictory information. Hence, exploring imprinting based on dynamics may become a new perspective for related research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ali I, Mandurah S (2016) The role of personal values and perceived social support in developing socially responsible consumer behavior. Asian Soc Sci 12(10):180–189

Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D (1992) Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Personal Soc Psychol 63(4):596–612

Bateson M, Nettle D, Roberts G (2006) Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real world settings. Biol Lett 2:412–414

Batson CD (1991) The altruism question: toward a social–psychological answer. Psychology Press

Bendapudi N, Singh SN, Bendapudi V (1996) Enhacing heiping behavior: an integrative framework for marketing planning. J Mark 60(7):33–49

Bekkers R (2006) Traditional and health-related philanthropy: the role of resources and personality. Soc Psychol Q 69(4):349–366

Bekkers R (2007) Measuring altruistic behavior in surveys: the all-or-nothing dictator game. Surv Res Methods 1:101–123

Bekkers R (2005) Participation in voluntary associations: relations with resources, personality and political values. Political Psychol 26:438–454

Bekkers R (2008) Straight from the heart. In: Chambre S, Goldner M, Root R (eds) Patients, consumers and civil society: us and international perspectives. Advances in Medical Sociology. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Bekkers R, Wiepking P (2011) A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drives charitable giving. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 40(5):924–973

Bethell CJJ, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R (2019) Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr 173(11):e193007

Brown E, Ferris JM (2007) Social capital and philanthropy: an analysis of the impact of social capital on individual giving and volunteering. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 36(1):85–99

Cadenhead AC, Richman CL (1996) The effects of interpersonal trust and group status on prosocial and aggresssive behaviors. Soc Behav Personal Int J 24(2):169–184

Chen YL (2024) Early exposure to air pollution and cognitive development later in life: evidence from China. China Econ Rev 83:112098

Churchill SA, Munyanyi ME, Smyth R, Trinh TA, Business JO, Woodside AG (2021) Early life shocks and entrepreneurship: evidence from the Vietnam war. J Bus Res 124:508–518

Davis MH (1980) A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat Sel Doc Psychol 10:85

De Dreu CKW, Weingart LR, Kwon S (2000) Influence of social motives on integrative negotiation: a meta-analytic review and test of two theories. J Personal Soc Psychol 78:889–905

De Dreu CKW (2006) Rational self-interest and other orientation in organizational behaviour: a critical appraisal and extension of Meglino and Korsgaard. J Appl Psychol 91:1245–1252

Eisenberg N, Miller P (1987) The relation of empathy to proposal and related behaviors. Psychol Bull 101:91–119

Elder GH, Gimbel C, Ivie R (1991) Turning points in life: the case of military service and war. Mil Psychol 2:215–231

Fan J, Fan XW (2023) A research on the impact mechanism of social support on customer creativity in online brand community. J Cent Univ Financ Econ 5:119–128

Fong CM (2007) Evidence from an experiment on charity to welfare recipients: reciprocity, altruism, and the empathic responsiveness hypothesis. Econ J 117:1008–1024

Galinsky AD, Maddux WW, Gilin D, White JB (2008) Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychol Sci 19(4):378–384

Gneey U, List JA (2006) Putting behavioral economics to work: testing for gifting exchange in labor markets using field experiments. Econometrica 74:1365–1384

Graddy E, Wang L (2009) Community foundation development and social capital. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 38:392–412

Grant AM (2007) Relationship job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Acad Manag Rev 32:393–417

Grant AM (2008) Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J Appl Psychol 931:48–58

Grant AM, Berry JW (2011) The necessity of others is the mother of invention: intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Acad Manag J 1:73–96

Guo Y (2022) The relationship between perceived social support and college student’s prosocial behavior—the mediating role of empathy and the moderating role of self-esteem. Surv Educ 11(32):7–11

Han D, Dieujeste N, Doom JR, Narayan AJ (2023) A systematic review of positive childhood experiences and adult outcomes: promotive and protective processes for resilience in the context of childhood adversity. Child Abus Negl 144:106346

Han Y, Chi W, Zhou JY (2022) Prosocial imprint: CEO childhood famine experience and corporate philanthropic donation. J Bus Res 139:1604–1618

Hahn A, Gawronski B (2015) Implicit social cognition. In: Wright JD (ed) Behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. International encyclopedia of the social behavioral sciences. Elsevier, pp 714–720

Hobfoll SE, Freedy J, Lane C, Geller P (1990) Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. J Soc Personal Relatsh 7(4):465–478

Hodges SD, Kiel KJ, Kramer A, Veach D, Villanueva BR (2010) Giving birth to empathy: the effects of similar experience on empathic accuracy, empathic concern, and perceived empathy. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 36(3):398–409

Hou JD (2009) Research on the effects of nonprofit’s perceptual attributes on individual donors’ giving behavior. Huazhong University of Science & Technology

Jin TL, Wu YTN, Zhang L, Yang X et al. (2020) The effect of perceived chronic social adversity on aggression of college students: the roles of ruminative responses and perceived social support. Psychol Dev Educ 36(4):414–421

Karlan D, List JA (2007) Does price matter in charitable giving? Evidence from a large-scale natural field experiment. Am Econ Rev 97(5):1774–1793

Kish-Gephart JJ, Campbell JT (2015) You don’t forget your roots: the influence of CEO social class background on strategic risk taking. Acad Manag J 58(6):1614–1636

Kraus MW, Tan J, Tannenbaum MB (2013) The social ladder: a rank-based perspective on social class. Psychol Inq 24(2):81–96

Leppma M, Young ME (2016) Loving-kindness meditation and empathy: a wellness group intervention for counseling students. J Couns Dev 94(3):297–305

Lenzi M, Vieno A, Perkins DD, Pastore M, Santinello M (2012) Perceived neighborhood social resources as determinants of prosocial behavior in early adolescence. Am J Community Psychol 50:37–49

Liu A, Wang W, Wu X (2021) Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth mediate the relations between social support, prosocial behavior, and antisocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Eur J Psychotraumatol 12(1):1864949

Liu WK, Jiang RJ, Hu LL (2024) College students’ understanding of the relationship between social support and prosocial behavior: the mediating role of gratitude and moderating role of belief in a just world. Rev High Educ 2:38–44+90

Marquis C, Tilcsik A (2013) Imprinting: toward a multilevel theory. Acad Manag Ann 7(1):195–245

McLaughlin K, Conron K, Koenen K, Gilman S (2010) Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med 40(10):1647–1658

Parker SK, Axtell CM (2001) Seeing another viewpoint: antecedents and outcomes of employee perspective taking. Acad Manag J 44:1085–1100

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891

Rosenbaum M, Massiah CA (2007) When customers receive support from other customers: exploring the influence of inter-customer social support on customer voluntary performance. J Serv Res 9(3):257–270

Rosenman S, Rodgers B (2006) Childhood adversity and adult personality. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry 40(5):482–490

Shang J, Reed A, Sargeant A, Carpenter K (2020) Marketplace donation: the role of moral identity discrepancy and gender. J Mark Res 57(2):375–393

Simsek Z, Fox BC, Heavey C (2015) “What’s past is prologue”: a framework, review, and future directions for organizational research on imprinting. J Manag 41(1):288–317

Škerlava JM, Connelly CE, Cerne M et al. (2018) Time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding. J Knowl Manag 22(7):1489–1509

Smith JR, McSweeney A (2007) Charitable Giving: the effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behavior model in predicting donating intentions and behavior. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 17:285–302

Soetevent AR (2005) Anonymity in giving in a natural context—a field experiment in 30 churches. J Public Econ 89:2301–2323

Tankersley D, Stowe CJ, Huettel SA (2007) Altruism is associated with an increased neutral response to agency. Nat Neurosci 10:150–151

Tian L, Jiang Y, Yang Y (2022) CEO childhood trauma, social networks, and strategic risk taking. Leadersh Q 34(2):101618

Tsang JA (2006) The effects of helper intention on gratitude and indebtedness. Motiv Emot 30(3):198–204

Verhaert GA, Van den Poel D (2016) Empathy as added value in predicting donation behavior. J Bus Res 64:1288–1295

Vescio TK, Sechrist GB, Paolucci MP (2003) Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: the mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions. Eur J Soc Psychol 33(4):455–472

Vorauer JD, Sasaki SJ (2009) Helpful only in the abstract? Ironic effects of empathy in intergroup interaction. Psychol Sci 20(2):191–197

Wang L, Graddy E (2008) Social capital, volunteering, and charitable giving. Voluntas 19(1):23–42

Wang CS, Tai K, Ku G, Galinsky AD (2014) Perspective-thinking increases willingness to engage in intergroup contact. PLoS ONE 9(1):e85681

Wang XC, Rao C (2015) The dimension and the impact mechanism of perceived support for customers. J Beijing Inst Technol (Soc Sci Ed) 17(6):99–105

Warwick M (2011) How to write successful fundraising letters: sample letters, style tips, useful hints, real-world examples. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Wentzel KR (2003) Motivating students to behave in socially competent ways. Theory Into Pract 42(4):319–326

Xu S, Ma P (2022) CEOs’ poverty experience and corporate social responsibility: are CEOs who have experienced poverty more generous? J Bus Ethics 180(2):1–30

Zahodne LB, Sharifian N, Manly JJ, Sumner JA, Crowe M, Wadley VG, Howard VJ, Murchland AR, Brenowitz WD, Weuve J (2019) Life course biopsychosocial effects of retrospective childhood social support and later-life cognition. Psychol Aging 347:867–883

Zhang FF, Dong Y, Wang K, Zhan ZJ, XIe LF (2010) Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the interpersonal reactivity index-C. Chin J Clin Psychol 18(2):155–157

Zhang ZJ, Liu QL (2014) Rational or altruistic: the impact of social media information exposure on Chinese youth’s willingness to donate blood. Front Public Health 12:1359362

Zhu DH, Sun H, Change YP (2016) Effect of social support on customer satisfaction and citizenship behavior in online brand communities: the moderating role of support source. J Retail Consum Serv 2016(31):287–293

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess 52(1):30–41

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided: the Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department: No. Y202455584 (Ying Wang), No. Y202353212 (Tingyuan Lou); the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Zhejiang Province of China: No. 25NDJC021YBMS (Tingyuan Lou); the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China: No. 23YJC630054 (Qiang Hu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ying Wang: Writing of original draft, investigation, methodology, data analysis, and manuscript revision; Xiaogang He: Research design and manuscript revision; Qiang Hu: Literature review and manuscript revision; Tingyuan Lou: Organization and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and granted full approval on September 2, 2023, by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (上海财经大学伦理审查委员会), a formally recognized ethics committee constituted in compliance with international standards for ethical oversight. The ethical approval explicitly covered all aspects of the research protocol, including participant recruitment procedures, the informed consent process, all data collection instruments, protocols for data handling, storage, and the dissemination of results. The study was conducted in strict accordance with the principles outlined in the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants between October 13, 2023, and November 10, 2023. The consent document, which was reviewed and approved in full by the IRB for its clarity and comprehensibility, detailed the research objectives, data collection methods, and consent for the publication of results. It explicitly guaranteed participant anonymity, confidentiality, and the exclusive use of data for academic research purposes, with no disclosure to any third parties. Participants were advised of their voluntary participation and right to withdraw at any time without penalty. As this was a non-interventional study, the document also informed participants that there were no foreseeable risks associated with their involvement. The form provided clear contact details for both the principal investigator and the IRB for any further questions or concerns.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., He, X., Hu, Q. et al. The effect of childhood experience on consumers’ willingness to donate: an imprinting perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1484 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05807-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05807-7