Abstract

Detecting trace amounts of harmful bacteria and nanoscale biomarkers is essential for early diagnosis and disease prevention. However, conventional methods, such as cultivation and immunoassays, are time-consuming and suffer from limited biological sensitivity. To address these limitations, we developed a rapid and highly sensitive detection method based on optical condensation using a metallic thin-film-coated optical fibre module. Acting as a photothermal source, this module induces convection and bubble formation at the fibre tip, enabling efficient three-dimensional condensation of targets within liquid samples. When positioned away from the substrate, the module assembled 103–105 bacteria and microparticles from a 20 μL sample within 60 s. This approach increased assembly efficiency by more than ten-fold compared with conventional two-dimensional photothermal methods, concentrating over 10% of all target objects through combined horizontal and vertical convection. These findings highlight the potential of this technique for advancing bioanalytical detection, drug delivery and material assembly technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate detection of harmful bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (E. coli), is essential for preventing infection and ensuring public health. For instance, E. coli O157 can cause severe illness even at very low concentrations (10–100 cells)1,2. Various methodologies have been employed to detect scant quantities of harmful bacteria, including conventional cultivation, flow cytometry3,4, lateral flow assay5 and spectroscopic methods such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy6 and fluorescence microscopy7. A more straightforward approach involves using optical tweezers to trap bacteria in a dispersion liquid.

Since Ashkin’s pioneering study on optical tweezers8, the optical manipulation of nano- and micro-sized objects, including bacteria, using light-induced forces has gained widespread application across disciplines, such as optical physics, chemistry, cell biology and nanotechnology9,10. Optical tweezers rely on electromagnetic interactions between light and materials to manipulate target objects11,12,13,14, typically using a tightly focused laser beam through a high-numerical-aperture objective lens. Although this enables precise control of microscale objects, the laser spot is constrained by the diffraction limit, rendering the manipulation of nanosized objects challenging. To address this limitation, plasmonic tweezers have been developed, which enhance electric fields through surface plasmon resonance in metallic structures15. By irradiating nanogaps between metallic nanoparticles, these tweezers generate intensified electric fields capable of trapping and manipulating nano-sized objects and bacteria16.

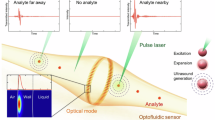

In addition to enhanced electric fields, high-intensity laser irradiation of metallic structures also induces heat generation via the photothermal effect17, which has spurred interest in photothermal fluidics driven by thermally induced convection18,19,20,21,22. This effect originates from laser-excited electrons, which cause molecular vibrations in the metal, converting light energy into phonon energy. Although this effect is typically considered an impediment to stable optical manipulation by causing thermal disturbance, photothermal convection can be exploited to assemble dispersoids, objects dispersed in a fluid medium, typically on the nanoscale to microscale, such as particles and bacteria. Laser irradiation of metallic nanoparticles or thin films induces thermal convection and bubble formation due to photothermal heat23. This thermal convection transports dispersoids toward the bubble, assembling them between the bubble and the substrate, a phenomenon known as optical condensation. Optical condensation has been effectively utilised for assembling nanoparticles, microparticles and bacteria24,25,26, and this method is particularly promising for acceleration and cost-reduction in biological analysis although conventional methods are often time-consuming and expensive. Recently, substrates featuring unique structures, such as honeycomb or bowl-like structures, or imitation bubbles, have been employed to control temperature distribution and facilitate spectroscopic analysis27,28,29. However, the assembly efficiency—defined as the ratio of the number of assembled particles to the total number of particles in the dispersion liquid—remains low and requires enhancement for practical applications.

Recently, optical fibres, including tapered, hollow-core, and plasmonic fibres, have been used to manipulate dispersoids via light-induced force and drive light-induced convection30,31,32,33,34. Tapered optical fibres primarily control and assemble microparticles, cells and bacteria using optical fibre tweezers30,31. In addition, dispersoid assembly has also been reported through bubble generation using tapered and hollow-core fibres, particularly when light-absorbing materials such as graphene are used as the dispersing material32,33. Metallic nanostructures can also be fabricated at the tips of optical fibres to drive light-induced convection, trap dispersoids34 and generate bubbles35,36,37,38.

Inspired by these literatures, this study aims to develop a more sensitive optical condensation method. We explore three-dimensional optical condensation within liquid media using optical fibre modules featuring metallic nanostructures. These modules, built from commercially available optical fibres coated with gold nanofilms via ion sputtering, serve as light and heat sources at their tips, enabling optical condensation at arbitrary positions within the dispersion liquid. We investigate the optical condensation of microparticles and bacteria with an optical fibre module distant from the substrate, focusing on elucidation of the assembly mechanism of dispersoids via light-induced convection from experimental observations and numerical calculations. The findings reveal that the optical fibre module enhanced assembly efficiency by over 10%. Compared to conventional flat-substrate setups, our fibre modules achieve significantly higher assembly efficiency due to the combined effect of vertical and horizontal convection, as confirmed by numerical simulations. This method successfully assembles not only microparticles but also nanoparticles and bacteria. In particular, placing the fibre module in contact with the substrate lead to a unique assembly behaviour, including lateral particle migration along the fibre–substrate interface—phenomena not observed in flat-substrate systems and likely driven by a combination of convection, thermophoresis, and capillary forces. Although higher laser power is used due to non-resonant wavelength heating, the technique can be further optimised with plasmonic nanostructures to reduce thermal damage. These findings demonstrate the method’s versatility and potential for applications in bioanalysis, drug delivery and portable diagnostic systems.

Results

Optical condensation with optical fibre module positioned at a distance from the substrate

Polystyrene particles were optically condensed using gold-coated (10 nm) optical fibre, assembling dispersoids at the tip (Fig. 1a). Upon laser irradiation from the tip of the fibre, a bubble was generated on the tip of the fibre, and dispersoids were transported and concentrated at the fibre tip via bubble-induced Marangoni convection from vertical and horizontal directions in the dispersion liquid (Fig. 1b, c). The optical fibre module was prepared via ion sputtering, which deposited a thin gold film onto the bare fibre (Fig. 1d). Optical transmission and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Fig. 1e–g) confirmed successful deposition. The film formed discrete gold clusters or islands, rather than a uniform layer, due to the sputtering process39.

a Overview. b Top-view. c Side-view. Optical transmission image of the optical fibre module (d) before ion sputtering; (e) after ion sputtering. The scale bars in (d, e) are 75 μm. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the optical fibre module (f) after ion sputtering; g captured with a stage tilted at 30°. The scale bars in (f, g) are 20 μm.

A dispersion liquid (amount: 20 μL) containing polystyrene (PS) particles (diameter: 1 μm, concentration: 4.55 × 107 particles/mL) was applied to the observation microwell, as described in the Methods section. The optical system is shown in Fig. S1. The optical fibre module was centrally positioned in the observation microwell. Laser power for optical condensation was determined by preliminary experiments using the optical system shown in Fig. S2a, investigating assembly efficiency (defined below). A power of 390 mW was selected based on the results shown in Fig. S2b. A 976 nm continuous wave (CW) laser (390 mW) was launched into the optical fibre module, generating a bubble at the fibre tip, as illustrated in Supplementary Movie 1. Transmission and fluorescence images captured immediately before stopping laser irradiation are presented in Fig. 2a, b. During laser exposure, the bubble at the fibre tip expanded and concurrently generated thermal convection. This convection was identified as Marangoni convection, driven by a surface tension gradient across the bubble surface. The gradient arose from a temperature difference between the bottom (in contact with the heated fibre tip) and the top of the bubble. As surface tension decreases with increasing temperature at the air/liquid interface, this gradient induced fluid flow from the warmer to the cooler regions, transporting dispersoids toward the stagnant assembly site between the bubble and fibre tip. This mechanism resembles that observed in conventional optical condensation on gold-coated substrates25. However, in this case, the assembled particles were more widely distributed than the stagnant zone alone would explain, suggesting that particles adsorbed onto the bubble surface, or new particles carried there, were pushed by convection, aiding the overall assembly process. Previous research indicates that particles adsorb onto bubble surfaces40 and subsequently migrate and assemble between the substrate and bubble41. Bubbles shrank and occasionally detached from the fibre tip immediately after stopping laser irradiation. This phenomenon is influenced by the presence of surfactants, which preferentially at the cooler top of the bubble rather than at the warmer bottom near the fibre tip heat source. Turning off the laser equalised the temperature across the bubble surface, leading to uniform surfactant adsorption. This uniform adsorption contributed to more stable bubble formation and subsequent detachment. If a bubble remained attached to the fibre tip, its size remained nearly constant for several minutes or more, enabling continuous observation for extended periods without bubble disappearance. In particular, when a bubble eventually detached, a portion of the assembled particles moved along with it (Supplementary Movie 1), supporting the earlier observation of particle adsorption onto the bubble surface. Optical condensation was also demonstrated using the module across varying particle concentrations. Particles assembly was observed when concentrations were 4.55 × 106 and 4.55 × 108 particles/mL (Fig. 2c, d, respectively).

a Optical transmission image and b–d fluorescence images of optical condensation with the optical fibre module at 60 s after laser irradiation for each concentration of 1 μm PS particles (concentration: a, b 4.55 × 107, c 4.55 × 106 and d 4.55 × 108 particles/mL). Here, green fluorescent objects in (b–d) show 1 μm PS particles. White ellipses in (b–d) indicate assembly area. The scale bar is 75 μm.

We estimated the assembled particle number and assembly efficiency from the fluorescence images after laser irradiation. As mentioned earlier, assembly efficiency is defined as the ratio of assembled particles to the total particles in the dispersion liquid. For instance, if 100 out of 1000 particles are assembled within the dispersion liquid, the assembly efficiency is 10%. A model for calculating the assembly efficiency on flat substrates was established in previous research25. However, because optical condensation at the fibre tip enables cross-sectional observation of the particle assembly state, we modified the existing model accordingly25. The number of assembled particles was geometrically estimated from fluorescence images, based on the assumption that particles were uniformly assembled around the bubbles. The calculation model (Fig. S3) uses the following estimation formula:

where h denotes the height of the assembled particles region, ru represents the radius at the upper boundary of the assembled particles region, rb is the radius at the bottom boundary of the assembled particles region, rg depicts the radius of the contact area between the fibre tip and bubble, V is the dispersoid volume, and 0.74 is the three-dimensional filling rate. Each parameter was estimated from the fluorescence images after optical condensation. The estimated NAB values for each concentration are shown in Fig. 3a. In a high-concentration regime, NAB tends to saturate, whereas in a low-concentration regime, it is a marked increase. The assembly efficiency, derived from the estimated number of assembled particles for each concentration (Fig. 3b), was 2.3 ± 0.6% at high concentrations (4.55 × 108 particles/mL) and increases to 11.6 ± 3.4% at low concentrations (4.55 × 106 particles/mL). This variation may be attributed to particle occupation at the assembly site between the bubble and fibre tip. At high particle concentrations, the assembly site was occupied by particles transported by convection, whereas at low particle concentrations, the assembly site was vacant. This is because the number of dispersed particles in the low-concentration regime is lower than that in the high-concentration regime.

a Number of assembled particles and b assembly efficiency of 1 μm PS particles at 60 s after laser irradiation as a function of particle concentration (n = 3 independent experiments). Red circles show data with optical fibre module and blue triangles show data with flat substrate. Error bars represent standard deviation.

To benchmark our approach against conventional optical condensation methods, we demonstrated optical condensation of polystyrene particles (diameter: 1 μm, concentrations: 4.55 × 108, 4.55 × 107, and 4.55 × 106 particles/mL) on a gold-coated substrate (film thickness: 10 nm). The same laser power (390 mW) was used for both the optical fibre module and for substrate irradiation using an objective lens for focusing. In particular, the laser power in conventional optical condensation was higher than that in the optical fibre module because of the smaller laser spot size produced by the objective lens, which was narrower than the core diameter of the optical fibre module. Snapshots of the transmission images acquired immediately before the laser was turned off at each concentration are shown in Fig. S4. In the conventional method, dispersoids assembled between the bubble and the substrate, as previously reported25. The assembly efficiency of the conventional optical condensation was also estimated, as depicted in Fig. 3b. In this instance, the height of the assembled particles region could not be measured using optical images; therefore, we employed the calculation model from a previous report25. Consequently, the maximum assembly efficiency of the conventional optical condensation was determined to be 0.90 ± 0.13% at (4.55 × 108 particles/mL), which aligns with that obtained in previous studies25. The assembly efficiency of fibre-based methods exceeded that of conventional methods across all particle concentrations, with over a ten-fold increase at the lowest concentration. Two factors that may have contributed to the increased assembly efficiency in fibre-based optical condensation are the direction and velocity of thermal convection. First, regarding the direction of thermal convection, in flat substrate optical condensation, only horizontal thermal convection contributes to assembly, which limits the transport and trapping of dispersoids to the lateral direction. However, in fibre-based optical condensation, both vertical and horizontal convection contribute to assembly, transporting dispersoids toward the bubble at the fibre tip. Second, in flat substrate optical condensation, the thermal convection velocity is reduced due to the viscosity stress on the substrate surface. In contrast, in fibre-based optical condensation, the velocity does not decrease because the optical fibre module is placed at a considerable distance from the substrate. Hence, fibre-based optical condensation enables faster thermal convection in both vertical and horizontal directions, drawing particles from a wider region within the dispersion liquid. This increases the number of particles transported per unit time, thereby resulting in highly efficient particle assembly.

To elucidate the assembly mechanism in fibre-based optical condensation, we conducted simulations of the convection distribution using COMSOL Multiphysics, employing the finite element method (see the ‘Methods’ section). The bubble size was determined from the experimental results. The results revealed a convection distribution in the xy-plane at z = 430 μm, aligning with the experimental observations (Fig. 4a). The distribution in the yz-plane at x = 0 μm, viewed from the side, is shown in Fig. 4b. Figure 4c, d provide a magnified view of the region around each fibre tip. The arrows in Fig. 4a–d indicate the in-plane components of normalised convective velocity. Figure 4e, f display the calculated temperature distributions in the xy-plane at z = 430 μm and the yz-plane at x = 0 μm, respectively. Isotherms at 150 °C, 100 °C, and 50 °C were observed radially outward from the centre of the fibre tip. The calculated temperature distributions suggest that the bottom of the bubble is relatively hot and the top of the bubble is relatively cold, as assumed in the experiment. This temperature gradient drives Marangoni convection via the surface tension gradient. These simulations demonstrate that both horizontal and vertical convection are directed to the tips of the fibre, with increased velocity near the bubble surface due to Marangoni convection. The flow’s asymmetry along the z-axis in the yz-plane correlates with temperature distribution. When the area near the tip of the fibre was enlarged, a region with lower convection velocity than the surrounding areas was observed to be formed between the bubble and the tip of the fibre. This region generally corresponds to the area where particles assembled during the experiment, suggesting that the space between the fibre and bubble acts as an assembly site.

Convective velocity distribution around the optical fibre module and bubble a in the xy-plane; b in the yz-plane at x = 0 μm. Enlarged images in c xy-plane and d yz-plane. Here, the colour map indicates the convective velocity, and the white arrows indicate the in-plane components of the normalised convective velocity. Temperature distribution around the optical fibre module and bubble e in the xy-plane; f in the yz-plane at x = 0 μm. White contours indicate isothermal lines of 150, 100 and 50 °C from the fibre centre.

Based on previous experiments, simulations, and discussions, the principle of optical condensation using an optical fibre module was hypothesised as follows: when laser was introduced into the optical fibre module, the bubble was generated by photothermal effect. Surface tension gradients on the bubble surface generate Marangoni convection, which rapidly transports particles towards a slow-flow region near the three-phase interface at the optical fibre tip from both vertical and horizontal directions in the dispersion liquid. Transported particles adsorb and assemble on both the fibre tip and bubble surfaces. Convection drives particles toward existing assemblies, expanding the assembly site during laser irradiation and holding the particles. After irradiation ends, non-adsorbed particles and particles held by convection diffuse away, whereas those bound to the interface remain at the fibre tip. This mechanism facilitates the particle assembly efficiency compared with that of conventional optical condensation on flat substrates.

Subsequently, we explored the optical condensation of bacteria and nanoparticles for use in bioanalytical techniques. We used rod-shaped bacteria E. coli, stained with fluorescent dyes (SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI)), which display green and red fluorescence for living and dead bacteria, respectively. A green fluorescence image of the bacteria at concentrations of 2.3 × 107 and 2.3 × 106 cells/mL is shown in Fig. 5a, b at a laser power of 390 mW. For clarity, the brightness of Fig. 5b was increased by 4 times compared to the original image with NIS-elements AR software (Nikon, Japan). The original image of Fig. 5b is shown in Fig. S5. Similar to polystyrene particles, bacteria assembled at the fibre tip, albeit in smaller numbers, likely due to differences in surface conditions and bacterial shapes. The estimated assembly efficiencies for bacteria were 7.3 ± 1.9% (at 2.3 × 107 cells/mL) and 10.2 ± 2.3% (at 2.3 × 106 cells/mL). This indicated that bacterial assembly efficiency was lower than that of polystyrene particles at comparable concentrations. Conversely, a red fluorescence image of assembled bacteria after laser irradiation (Fig. S6) indicated that most bacteria were dead. The average survival rates estimated from fluorescence images were 41.0 ± 4.7% at 2.3 × 107 cells/mL and 47.9 ± 2.1% at 2.3 × 106 cells/mL (see Method section for detailed estimation method). In prior studies, high bacterial survival rates during assembly were achieved using substrate-constructed nano-microstructures by controlling temperature distribution27,28,29,42. For future bacterial applications, constructing nano- and micro-structures, such as plasmonic42 or honeycomb configurations28 at the fibre tip would be promising to mitigate thermal damage to the bacteria. Additionally, the laser’s power significantly influences bubble generation: higher laser power in optical fibre modules results in larger bubbles. Reducing laser spot and heating zone size has been reported to enable bubble formation at lower power22. Therefore, reducing the optical fibre core may enable optical condensation at lower power.

a, b Fluorescence images of E. coli (concentration: a 2.3 × 107 cells/mL, b 2.3 × 106 cells/mL) 60 s after laser irradiation of optical condensation with the optical fibre module and c nanoparticles (diameter: 100 nm, concentration: 4.55 × 1010 particles/mL) captured at 60 s after laser irradiation. Here, green fluorescent objects show E. coli in (a, b), 100 nm polystyrene particles in (c). White ellipses in (a–c) indicate assembly area. For clarity, brightness of (b) was increased by 4 times compared to the original image. The assembly efficiencies are a 7.3 ± 1.9%, b 10.2 ± 2.3%, and c 0.89 ± 0.5%, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). Scale bar is 75 μm.

Additionally, polystyrene nanoparticles, of diameter 100 nm and at a concentration of 4.55 × 1010 particles/mL, assembled at a laser power of 390 mW, similar to the micro-sized polystyrene particles and bacteria (Fig. 5c). The assembly efficiency for nanoparticles (0.89 ± 0.5%) was lower than that for microparticles, which was attributed to the higher concentration of nanoparticles that reduced the assembly efficiency. Previous research reported an assembly efficiency of approximately 0.11% for 100 nm polystyrene particles25. This suggests that using an optical fibre module significantly increases nanoparticle assembly efficiency. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of fibre-based optical condensation for applications such as bacterial count measurements and enhancing the sensing efficiency of quantum sensors, given the comparable sizes of the nanoparticles and nanodiamonds used in these sensors.

Optical condensation with optical fibre module on the substrate

Optical condensation of polystyrene particles was conducted using optical fibre modules positioned on the substrate. To secure the optical fibre module via capillary force, we adjusted the height of the stand and pressed the module down to the floor of the observation microwell. When a 390 mW laser beam was introduced into the fibre, bubbles were sometimes formed at the side of the fibre (Fig. S7). This phenomenon was not observed when the fibre was positioned away from the substrate and was likely due to the gold film coating on the side of the fibre. Although the exact cause of side-bubble generation on the substrate remains unclear, we adjusted the laser power to 320 mW to prevent multiple bubble formation.

Upon introducing a 320 mW laser into the optical fibre module, bubbles and thermal convection were generated, akin to scenarios where optical condensation occurred away from the substrate. Snapshots acquired 60 s post-laser irradiation display an optical transmission image (Fig. 6a) and fluorescence images of 1 μm polystyrene particles (4.55 × 107 particles/mL, Fig. 6b), along with fluorescence images for 2 μm polystyrene particles at concentrations of 5.68 × 106 (Fig. 6c) and 4.55 × 107 particles/mL (Fig. 6d). These particles were transported by thermal convection towards the bubbles, as shown in Supplementary Movie 2. In particular, the particle migration speed was reduced compared to that in the fibre module positioned away from the substrate because of the increased shear stress on the substrate surface, which slowed the thermal convection velocity.

a Optical transmission image of 1 μm polystyrene particles 60 s after laser irradiation. Fluorescence images of b 1 μm polystyrene particles (4.55 × 107 particles/mL), and (c, d) 2 μm polystyrene particles at concentrations of c 5.68 × 106 and d 4.55 × 107 particles/mL, acquired 60 s after laser irradiation. Here, green fluorescent objects indicate a 1 μm polystyrene particles and b–e 2 μm polystyrene particles. e Trajectory of assembled particles from 30 s to 40 s post-laser irradiation (2 μm polystyrene particles at concentrations of 5.68 × 106 particles/mL). White numbers indicate particle locations, with red circles marking their positions at each timestamp. Average migration speeds at these locations are: (1) 13.6 ± 3.3, (2) 11.6 ± 3.4, (3) 9.8 ± 2.5, (4) 10.1 ± 0.9, (5) 6.1 ± 1.1, and 5.9 ± 1.0 μm/s, respectively (n = 3 independent experiments). Scale bar is 75 μm.

Particle assembly was observed between the bubble and fibre tip, and around the fibre for various particle sizes and concentrations. This assembly phenomenon, unlike that in conventional optical condensation or fibre-based optical condensation removed from the substrate, is characterised by the movement of a few particles from between the bubble and fibre tip across the optical fibre–substrate contact area. We quantified particle migration speed by tracking trajectories 30 to 40 s after laser irradiation across three independent experiments (2 μm polystyrene particles at concentrations of 5.68 × 106 particles/mL); one such result is depicted in Fig. 6e. White numbers indicate particle locations, with red circles marking their positions at each timestamp. Average migration speeds at these locations are: (1) 13.6 ± 3.3, (2) 11.6 ± 3.4, (3) 9.8 ± 2.5, (4) 10.1 ± 0.9, (5) 6.1 ± 1.1, and 5.9 ± 1.0 μm/s, respectively. Particles near the optical fibre module moved slower than those farther away. This indicates that the region around the fibre served as an assembly site, assembling particles transported by thermal convection.

Additionally, to investigate the assembly phenomenon around the fibre tip, we calculated the convection distribution with the optical fibre module placed on the substrate. The bubble size was determined based on the experimental results, as in the case where the optical fibre was placed at the centre of the optical condensation cell. However, because the diameter of the experimentally generated bubbles was larger than the optical fibre’s diameter, calculations were performed assuming that the bubbles were formed off-centre, upward from the fibre, when the fibre was on the substrate. In this calculation, only thermal convection is considered, excluding particle–fluid interaction and drag or thermophoretic forces on the particle. The calculated convection distributions are shown in Fig. 7a, b. Enlarged views near the fibre end face are presented in Fig. 7c, d. Furthermore, the temperature distribution is shown in Fig. 7e, f. The results (illustrated in Fig. 7) indicate that thermal convection directed particles towards the bubble (Fig. 7a) and formed an assembly site between the optical fibre, bubble, and substrate (Fig. 7b, d). The bubble, generated away from the fibre, created an asymmetric temperature gradient on its surface. This caused a swirling flow along the z-axis between the bubble and the substrate, which may contribute to the assembly. These particle transportation and convective fields align with the experimental observation of particles moving towards the optical fibre tip and the assembling between the fibre end face, bubble, and substrate. However, no stagnant area was observed around the optical fibre module (Fig. 7a, c), suggesting that the assembly around the fibre tip cannot be solely explained by thermal convection. Instead, the assembly is likely driven by a combination of thermophoresis, influenced by the temperature gradient around the fibre tip, and capillary force between the optical fibre module and substrate. Actually, previous studies reported that dispersoids, including PS particles and biological cells can be manipulated by thermophoresis43,44. Accounting these previous studies, the assembly process in this study can be considered as follows. When the laser is activated, thermal convection transports the microparticles to the bubble. As these particles are transported, they assemble around the fibre tip, where the balance between thermal convection and thermophoretic effects slows their movement. Additionally, some particles that may have assembled between the bubble and the fibre tip are displaced by the thermophoretic effect, and the capillary force draw these moving particles towards the contact area between the substrate and the optical fibre module. Thus, the assembly phenomenon results from the synergistic effects of thermal convection, thermophoresis, and capillary force. However, further experiments and calculations are essential to elucidate the assembly mechanism comprehensively.

Convective velocity distribution around the optical fibre module and bubble a in the xy-plane at z = 1 μm; b in the yz-plane at x = 0 μm. Enlarged images are shown in c xy-plane and d yz-plane. Here, the colour map indicates the convective velocity, and white arrows show the in-plane components of the normalised convective velocity. White dashed lines represent the outlines of the optical fibre and bubble. Temperature distribution around the optical fibre module and bubble e in the xy-plane at z = 1 μm; f in the yz-plane at x = 0 μm. White contours indicate isothermal lines of 150, 100 and 50 °C from the fibre centre.

Discussion

We developed optical fibre modules by depositing a thin gold film on the surface of an optical fibre, facilitating optical condensation at a distance from the substrate. The assembly efficiency achieved with this configuration was higher than that of setups where optical condensation involved a light-absorbing part, such as a thin gold film on a flat substrate. This improvement is attributed to the fact that in the flat substrate setup, only horizontal convection contributes to particle assembly, whereas in the fibre module setup, convection occurs in both the vertical and horizontal directions, enhancing the assembly rate per unit time. These observations were corroborated by numerical calculations of the convection distribution.

In addition to micro-sized particles, this method enables the assembly of nanoparticles and bacteria. Additionally, by positioning an optical fibre module directly on the substrate, we successfully assembled particles not only at the tip of the fibre but also around the fibre. Subsequently, some particles migrated from the fibre tip along the contact area between the optical fibre module and the substrate. This assembly behaviour, including particle migration, was not observed in conventional optical condensation on flat substrates, indicating a unique phenomenon facilitated by the fibre module placement. In particular, the behaviour cannot be attributed to convective flow alone. Therefore, a novel assembly mechanism was theorised by placing an optical fibre module on the substrate. We hypothesised that the observed assembly is driven primarily by light-induced convection, with additional contributions from thermophoresis and capillary effects, collectively enhancing the particle assembly process.

Laser power utilised in fibre optical condensation exceeds that typically employed for optical condensation. This was attributed to the use of the non-resonant wavelength of the gold film for heating. Although the laser power for heat generation could be reduced from that used in this study by employing a resonant wavelength (e.g. approximately 500 nm), we opted for an infrared laser to avoid potential photo-absorption damage to bacteria. Furthermore, fabricating gold nanostructures34,42 that exhibit plasmon resonance at the fibre tip, combined with the use of a resonant wavelength laser, could enable optical condensation at laser power as low as several tens of milliwatts. In these structures, heat is localised around the metallic part, potentially minimising damage to biological samples. If plasmonic42, honeycomb28, nanobowl45 or bubble-mimetic structures27,29, can be constructed at the fibre tip, the fibre optical condensation method may also be able to assemble dispersoids with minimal damage.

Dispersoid assemblies utilising Marangoni convection25,28,42,46,47,48 and optical fibres have been reported earlier31,32,33,34. These fall into two major categories: those where the optical fibre or substrate has a heat-generating site (e.g. metallic nanostructures)25,28,34,42, and those where light is absorbed directly by the dispersoids or dispersion liquid31,32,33,46,47,48. In the former case, substrate-based systems are more common. Only a limited number of studies have reported dispersoid assembly via bubble generation on optical fibres, as demonstrated in this work, and many of those involve complex fabrication of plasmonic structures. Conversely, in this study, light absorption sites were formed on the fibre tip by sputtering, which facilitated relatively straightforward fibre preparation. In the latter case, utilising light-absorbing dispersoids or dispersion media avoids the need for dedicated heating structures, thereby simplifying the pretreatment process. Additionally, using liquid absorption instead of metallic structures can mitigate heat generation, rendering the approach more compatible with biological samples by minimising thermal damage. However, these approaches are limited by the optical absorption characteristics of the dispersoids and dispersion medium, which constrain the range of usable light wavelengths. Although this research enables facile optical condensation at arbitrary positions, challenges in spatial heat control—as discussed in previous work on photothermal substrates27—still need addressing.

Future improvements in assembly efficiency may be achieved by moving the optical fibre module during optical condensation. Using multiple modules could enable investigation of bubble–bubble interactions. Given its high assembly efficiency, the developed module shows significant potential for applications in bioanalytical technologies, drug delivery evaluation, and medical applications such as endoscopy. Combining optical condensation with antigen–antibody reactions45,49, could extend the method’s applicability to selective detection, such as detecting foodborne bacteria in low-concentration samples. Future work will focus on simplifying and miniaturising the system into a portable device for on-site microbial and biological sample analysis during fieldwork.

Methods

Optical fibre module preparation

Commercial multimode fibres (GIF625, Thorlabs, USA) were used in this study. The fibres have a cladding diameter of 125 μm and a core diameter of 62.5 μm. After removing the polymer jacket, the multimode fibre was cleaved using a fibre cleaver. The bare fibre was then positioned on the stage of an ion-sputtering apparatus (MC1000, Hitachi, Japan), with the fibre tip and stage arranged perpendicular to each other to deposit a thin gold film (thickness: 10 nm) on the fibre tip. A scanning electron microscope (JSM-IT100, JEOL Ltd., Japan) was used to observe the optical fibre modules after ion sputtering. Following the sputtering process, the fibre was connected to an FC/PC patch cable (M31L02, Thorlabs, USA) using a fusion splicer (EasySplicer mk2, SBSCANDINAVIA, Sweden).

Experimental setup for optical condensation

An inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti2-E, Nikon, Japan) was employed to observe the optical condensation, as depicted in Fig. S1. A halogen lamp was used for sample illumination, and optical images were captured using a CMOS camera (DS-Fi3, Nikon, Japan). Fluorescence imaging was facilitated by a mercury lamp that served as the excitation light source and filter set (GFP-A-Basic, Semrock, USA). A handmade observation microwell comprising a slide glass, cover glass, and double-sided tape was positioned on the microscope stage to adjust the alignment between the optical fibre module and the observation microwell. A cover glass was placed atop the stand, and a 20 μL sample droplet was deposited onto this cover glass. The optical fibre module was then inserted into the droplet from the side. Another cover glass, spaced with double-sided tape (~860 μm), was placed on top of the first. This setup is referred to as the observation microwell. An infra-red continuous-wave (CW) laser (models BL976-SAG300 or BL976-PAG900, Thorlabs, USA) was channelled into the optical fibre module to induce optical condensation. Observations were performed using a 20× objective lens (0.45 NA) (CFI S Plan Fluor ELDW 20XC, Nikon, Japan). The laser power for optical condensation was determined via preliminary experiments (Fig. S2a) conducted with another optical system. This system, a microscope based on OTKB/M (Thorlabs, USA), utilised a 20X objective lens and a CMOS camera (DCC1240C, Thorlabs, USA). The optical condensation setup matched the aforementioned inverted microscope. The laser power was measured using a laser power metre (UP17O-H5 and TUNER; Gentec Electro-Optics, Canada). For comparison, the same microscope setup (Eclipse Ti2-E, Nikon, Japan) was used for conventional optical condensation on a substrate coated with a gold thin film via an ion-sputtering apparatus (MC1000, Hitachi, Japan). In this setup, a sample droplet was placed on a gold-coated substrate topped by a cover glass with a double-sided tape spacer (height: approximately 860 μm). An infra-red CW laser (1064 nm) (LS0100-FSC-SG, Oxide, Japan) was focused through a 40× objective (0.6 NA) lens (CFI S Plan Fluor ELDW 40XC, Nikon, Japan) and directed onto the substrate. Laser power was also measured using the laser power metre.

To assess the assembly of dispersoids, we employed NIS-elements AR software (Nikon, Japan) for both fibre-based and conventional substrate-based optical condensation. For the low concentration bacteria (Fig. 5b), we changed the brightness of the fluorescence image by using NIS-elements AR software. The original image of Fig. 5b and the brightness-increase image are shown in Fig. 5S. Assembly efficiency was estimated by calculating each parameter using the fluorescence image immediately before laser irradiation ended, based on the calculation model in Fig. S2. Obtaining rg directly from the fluorescence image was challenging; hence, we estimated it by identifying the bubble surface’s contour from the fluorescence image and finding its intersection with the optical fibre’s end face. For conventional substrate-based optical condensation, we employed the calculation model from a previous report25, and when particles assembled as single layer, the assembly efficiency was estimated by dividing projection area by the area of particles. Survival rate of assembled bacteria was estimated from green (SYTO9, living bacteria) and red (PI, dead bacteria) fluorescence images after laser irradiation. We estimated green and red fluorescent are because the bacteria were dispersed after laser irradiation, and we calculated survival rate by equation as follows,

To calculate the convection velocity of the optical fibre placed on the substrate, we tracked a particle starting 30 s after the laser turned on, marking its position with a red circle every second. The endpoint was the particle’s position 40 s after the laser turned on. The linear distance between the start and end points was then divided by the time to determine velocity. If tracked particles became difficult to follow owing to mixing with others near the fibre end face, the position just before mixing was used as the endpoint. All optical condensation experiments were conducted and evaluated across three independent experiments and fibres.

Sample preparation

PS particles and bacteria are the primary targets for optical condensation experiments. We purchased 2 μm, 1 μm, and 0.1 μm diameter PS particles (product numbers 09847, 15702, and 16662, respectively; Polyscience, USA) that contained a green fluorescent dye. Their initial concentrations, from the datasheet, were 5.68 × 109 (2 μm), 4.55 × 1010 (1 μm), and 4.55 × 1013 (1 μm) particles/mL. We then diluted the particle dispersions with ultrapure water to achieve the desired concentrations for the experiments.

We purchased E. coli NBRC 13168 from the Biological Resource Centre (NBRC), National Institute of Technology and Evaluation, Japan. The NB agar medium for E. coli cultivation was prepared by adding 9 g Nutrient Broth (E-MC35, Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan) and 7.5 g agar powder (010-08725, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan) to deionised distilled water (DDW). The NB liquid medium was similarly prepared by adding 9 g of Nutrient Broth to DDW. E. coli was then applied to the NB agar medium and incubated at 30 °C for one day. Afterward, an E. coli colony was added to the NB liquid medium and incubated at 30 °C for one day with shaking. Bacterial concentration was determined by cultivation on Petri film (6404EC, 3M, USA) for 24 h, and the average of three independent measurements was used. Before the optical condensation experiments, the cultured bacteria were centrifuged (6000 rpm, 5 min) and the supernatant replaced with DDW. This suspension and centrifugation process was repeated twice. Subsequently, the bacteria were stained with SYTO9 (green fluorescence) and PI (red fluorescence) from the LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™ Bacterial Viability Kit for microscopy (Invitrogen, USA).

To control light-induced convection, we added polyoxyethylene sorbitan monolaurate (T20; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Japan), a non-ionic surfactant, to all dispersion liquids. The surfactant’s final concentration was set to 9.04 × 10−5 M25. This ensured a consistent environment for studying optical condensation effects on both polystyrene particles and bacterial cells.

Simulation method and parameters

To elucidate the mechanism of fibre-based optical condensation, we conducted simulations using the finite element method in COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 (COMSOL AB, Sweden). Our model was designed with a three-dimensional plane symmetry to match the experimental setup depicted in Fig. S8. The computational model comprises a droplet sandwiched between two glass substrates, with an optical fibre inserted into the droplet, and a bubble formed at the fibre’s tip. For simplicity, the sample dispersion is assumed to be a cylinder, and the meniscus, present in experiments, is ignored in the calculations. The bubble radius was determined based on experimental results. We numerically solved the mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations to evaluate convective velocity and temperature profiles. In this calculation, the Reynolds number was computed as Re = L·u/ν = 1.03, where L is the characteristic length (300 µm; bubble diameter), u is the characteristic flow speed (1 mm/s; on the order of Marangoni convection around the bubble), and ν is the dynamic viscosity of water (2.9 × 10−7 m2/s; at 100 °C50). The sufficiently small Reynolds number confirmed the flow remained laminar. Additionally, inversion symmetry was imposed along the fibre’s centre (red line in the figure). The optical fibre was positioned either in the centre of the observation microwell (Fig. S8a) or at a 0.5 µm distance from the substrate (Fig. S8b). In the experiment, the substrate and the fibre are in contact, but in the numerical calculation, a distance of 0.5 µm is left for the convenience of meshing. The convective velocity profile was analysed in the liquid phase (water). The temperature profile encompassed the entire region, including the substrate (glass), optical fibre (glass), and bubble (air). In the experiment, the solvent was heated by the photothermal effect at the end surface of the optical fibre. In this study, heat generation was considered as a boundary heat source to reduce the computational load. A surface heat source was modelled at the end of the fibre core, with the generated heat defined by Q = P·A/S, where P is the laser power loss at the fibre tip (80 mW; laser power was assessed on both bare and sputtered fibres by adjusting the current of the laser power supply with the optical system (Fig. S9a). The laser power loss between the bare and sputtered fibres was then estimated. The maximum values in the experiments are shown in Fig. S9b); A is the absorptance (0.5; calibrated to align the maximum temperature of the simulation with experimental measurements taken by an infra-red thermal imaging camera (InfRec R550, Nippon Avionics, Japan), as shown in Fig. S9c. The thermography results are shown in Fig. S9d); S is the area of the fibre core (3318.3 µm2). The laser power loss was calculated as the difference between the measured laser output power of the bare fibre and the gold-coated optical fibre. The current of 700 mA in the figure corresponds to 390 mW in the experiment. The referenced physical properties were obtained from the COMSOL Multiphysics database. Water was considered incompressible, and the Boussinesq approximation was applied to account for the thermal expansion effects on density. The boundary conditions involved a no-slip condition at the solid–liquid interface (fibre/water, glass/water interface) and a slip condition coupled with the Marangoni effect at the air–liquid interface (bubble/water interface and water surface), where the surface tension was defined using the equation from our previous study25. The exterior boundaries (substrate surface, fibre surface, and liquid surface) were subjected to heat flux boundary conditions, assuming an energy loss of q0 = h (Text − T). The heat transfer coefficient was h = 30 W m−2 K−1 and the external temperature was Text = 293.15 K. The non-uniform mesh sizes for the simulation had maximums of 116 µm and 64 μm, and minimums of 0.35 µm and 0.21 µm for Fig. S8a, b, respectively.

Data availability

All data supporting the paper’s conclusions are available within the paper and/or its supplementary materials. The data used in all graphs are included in the Supplementary Data. Additional study data may be requested from the corresponding authors.

Code availability

All code necessary to evaluate the paper’s conclusions is available within the paper and/or its supplementary materials. Additional code related to this study may be available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Denamur, E., Clermont, O., Bonacorsi, S. & Gordon, D. The population genetics of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 37–54 (2021).

Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P. & Mobley, H. L. T. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 123–140 (2004).

Liu, S. et al. Raid detection of single viable Escherichia coli O157:H7 cells in milk by flow cytometry. J. Food Saf. 39, e12657 (2019).

Dharmasiri, U. et al. Enrichment and detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from water samples using an antibody modified microfluidic chip. Anal. Chem. 82, 2844–2849 (2010).

Sohrabi, H. et al. Lateral flow assays (LFA) for detection of pathogenic bacteria: a small point-of-care platform for diagnosis of human infectious diseases. Talanta 243, 123330 (2022).

Lee, K. S. et al. Raman microspectroscopy for microbiology. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 80 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Recent advances of fluorescent sensors for bacteria detection-A review. Talanta 254, 124133 (2023).

Ashkin, A., Dziedzic, J. M., Bjorkholm, J. E. & Chu, S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt. Lett. 11, 288–290 (1986).

Bustamante, C. J., Chemla, Y. R., Liu, S. & Wang, M. D. Optical tweezers in single-molecule biophysics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 25 (2021).

Moffitt, J. R., Chemla, Y. R., Smith, S. B. & Bustamante, C. Recent advances in optical tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 205–228 (2008).

Iida, T. & Ishihara, H. Theoretical study of the optical manipulation of semiconductor nanoparticles under an excitonic resonance condition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 057403 (2003).

Iida, T. & Ishihara, H. Theory of resonant radiation force exerted on nanostructures by optical excitation of their quantum states: from microscopic to macroscopic descriptions. Phys. Rev. B. 77, 245319 (2008).

Pesce, G., Jones, P. H., Maragò, O. M. & Volpe, G. Optical tweezers: theory and practice. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 949 (2020).

Nieminen, T. A., Knöner, G., Heckenberg, N. R. & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. Physics of optical tweezers. Methods Cell Biol. 82, 207–236 (2007).

Shoji, T. & Tsuboi, Y. Plasmonic optical tweezers toward molecular manipulation: tailoring plasmonic nanostructure, light source, and resonant trapping. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 2957–2967 (2014).

Righini, M. et al. Nano-optical trapping of rayleigh particles and Escherichia coli bacteria with resonant optical antennas. Nano Lett. 9, 3387–3391 (2009).

Kojima, C., Watanabe, Y., Hattori, H. & Iida, T. Design of photosensitive gold nanoparticles for biomedical applications based on self-consistent optical response theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 19091–19095 (2011).

Baffou, G., Cichos, F. & Quidant, R. Applications and challenges of thermoplasmonics. Nat. Mater. 19, 946–958 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Plasmonic tweezers: for nanoscale optical trapping and beyond. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 59 (2021).

Fujii, S. et al. Fabrication and placement of a ring structure of nanoparticles by a laser-induced micronanobubble on a gold surface. Langmuir 27, 8605–8610 (2011).

Lin, L. et al. Bubble-pen lithography. Nano Lett. 16, 701–708 (2016).

Baffou, G., Polleux, J., Rigneault, H. & Monneret, S. Super-heating and micro-bubble generation around plasmonic nanoparticles under cw illumination. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 4890–4898 (2014).

Namura, K., Nakajima, K., Kimura, K. & Suzuki, M. Photothermally controlled Marangoni flow around a micro bubble. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 043101 (2015).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Development of a rapid bacterial counting method based on photothermal assembling. Opt. Mat. Express 4, 1280–1285 (2016).

Yamamoto, Y., Tokonami, S. & Iida, T. Surfactant-controlled photothermal assembly of nanoparticles and microparticles for rapid concentration measurement of microbes. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2, 1561–1568 (2019).

Nakase, I. et al. Light-induced condensation of biofunctional molecules around targeted living cells to accelerate cytosolic delivery. Nano Lett. 22, 9805–9814 (2022).

Hayashi, K. et al. Damage-free light-induced assembly of intestinal bacteria with a bubble-mimetic substrate. Commun. Biol. 4, 385 (2021).

Tokonami, S. et al. Light-induced assembly of living bacteria with honeycomb substrate. Sci. Adv. 9, eaaz5757 (2020).

Hayashi, K., Tamura, M., Tokonami, S. & Iida, T. Quantitative fluorescence spectroscopy of living bacteria by optical condensation with a bubble-mimetic solid–liquid interface. AIP Adv. 12, 125214 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Optical fiber tweezers: from fabrication to applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 175, 110681 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Opto-hydrodynamic driven 3D dynamic microswarm petals. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2300480 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. All-fiber impurity collector based on laser-induced microbubble. Opt. Commun. 439, 308–311 (2019).

Yang, X. Light-induced thermal convection for collection and removal of carbon nanotubes. Fundam. Res. 2, 59–65 (2022).

Kim, J., Yeatman, E. & Thompson, A. Plasmonic optical fiber for bacteria manipulation—characterization and visualization of accumulation behavior under plasmo-thermal trapping. Biomed. Opt. Express 12, 3917–3933 (2021).

Ortega-Mendoza, J. G. et al. Selective photodeposition of zinc nanoparticles on the core of a single-mode optical fiber. Opt. Express 21, 6509–6518 (2013).

Ortega-Mendoza, J. G. et al. Marangoni force-driven manipulation of photothermally-induced microbubbles. Opt. Express 26, 6653–6662 (2018).

Sarabia-Alonso, J. A. et al. Optothermal generation, trapping, and manipulation of microbubbles. Opt. Express 28, 17672–17682 (2020).

Zhang, C. L. et al. Lab-on-tip based on photothermal microbubble generation for concentration detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 255, 2504–2509 (2018).

Siegel, J. et al. Properties of gold nanostructures sputtered on glass. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 96 (2011).

Zhao, C. et al. Theory and experiment on particle trapping and manipulation via optothermally generated bubbles. Lab Chip. 14, 384–391 (2014).

Okada, K., Kodama, K., Yamamoto, K. & Motosuke, M. Accumulation mechanism of nanoparticles around photothermally generated surface bubbles. J. Nanopart. Res. 23, 188 (2021).

Naka, S. et al. Thermo-plasmonic trapping of living cyanobacteria on a gold nanopyramidal dimer array: implications for plasmonic biochips. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 10067–10072 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Thermophoretic tweezers for low-power and versatile manipulation of biological cells. ACS Nano 11, 3147–3154 (2017).

Hill, E. H., Li, J., Lin, L., Liu, Y. & Zheng, Y. Opto-thermophoretic attraction, trapping, and dynamic manipulation of lipid vesicles. Langmuir 34, 13252–13262 (2018).

Kanoda, M. et al. High-throughput light-induced immunoassay with milliwatt-level laser under one-minute optical antibody-coating on nanoparticle-imprinted substrate. npj Biosensing 1, 1 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Light-induced cold Marangoni flow for microswarm actuation: from intelligent behaviors to collective drug delivery. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2200533 (2022).

Nishimura, Y. et al. Control of submillimeter phase transition by collective photothermal effect. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 18799–18804 (2014).

Iida, T. et al. Submillimetre network formation by light-induced hybridization of zeptomole-level DNA. Sci. Rep. 6, 37768 (2016).

Iida, T. et al. Attogram-level light-induced antigen-antibody binding confined in microflow. Commun. Biol. 5, 1053 (2022).

Lide, D. R. (ed. Lide, D. R.) Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 6–8 (CRC Press, 1990).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. S. Toyouchi for his advice and support. This work was partially supported by the JST-Mirai Program (No. JPMJMI18GA, No. JPMJMI21G1), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (No. JP21H04964, No. JP24H00433), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (No. JP 25H00421), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. JP21H01785), JST FOREST Program (No. JPMJFR201O), NEDO Intensive Support for Young Promising Researchers (No. PNP20004), Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (No. JP21J21304), Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (No. JP24K23034), Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (No. JP20K15196), Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) (No. 23H04594, JP25H01627), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (No. JP24K08282) from JSPS KAKENHI, AMED Moonshot Research and Development Program (No. JP24zf0127012s0501), the Key Project Grant Program of the Osaka Prefecture University, and the 2025 Osaka Metropolitan University (OMU) Strategic Research Promotion Project (Development of International Research Hubs). Also, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.I. and S.T. initiated the research and contributed equally to the study design. K.H., T.I., S.T. and M.F. performed the optical condensation with the optical fibre module. K.H., M.T. and T.I. carried out theoretical calculations. K.H., M.T., M.F., T.I. and S.T. prepared the figures and the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, K., Tamura, M., Fujiwara, M. et al. Highly efficient three-dimensional optical condensation of nano- and micro-particles using a gold-coated optical fibre module. Commun Phys 9, 68 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02480-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02480-9