Abstract

Ferroptosis, a newly discovered type of regulatory cell death with iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides, is widely discussed in a plethora of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, stroke, traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. There are many preclinical and clinical evidences supporting the critical role of ferroptosis in these neurologic conditions, despite the molecular machinery by which ferroptosis modulates brain dysfunction remains uncharacterized. Transcription factors (TFs) are core components of the machinery that manipulates ferroptosis process genetically. Until now, there is no report on the summarization of role of ferroptosis-associated TFs in neurological diseases. Therefore, here we provided the basic knowledge regarding the regulation of TFs on ferroptotic processes including iron metabolism, antioxidant defense and lipid peroxidation. In addition, we also discussed the recent advances in our understanding of ferroptosis-related TFs in the emerging hallmarks of neurological diseases. The fact that Nrf2 activator RTA-408 is approved for clinical evaluation (phase 2 clinical trial) of its efficacy and safety in patients with Alzheimer’s disease supports this notion. Future research on proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) and gene therapy holds promise for optimization of neurological disease treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

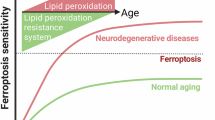

The balanced regulation between cell death and survival is essential for maintaining homeostasis in living organisms. Ferroptosis, a recently identified form of regulated cell death, is characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (LPO) and was first described by Stockwell’s research group in the year 20121. In contrast to apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and autophagy, ferroptosis is distinguished by unique morphological, genetic and biochemical features. Common morphological changes include alterations in biological membranes, particularly those of mitochondria and cells. These changes are marked by reduced mitochondrial volume, increased membrane density, and a loss of cristae2, which often culminates in membrane rupture3. In addition to these morphological alterations, significant changes in gene expression are observed during ferroptosis, with pivotal genes including glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)4, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH)5 and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)6,7. In detail, GPX4 prevents LPO by reducing reactive phospholipid hydroperoxides to stable products, while FSP1, an oxidized coenzyme Q10 oxidoreductase, produces antioxidants to counteract free radicals7,8. DHODH, located on the mitochondrial inner membrane, inhibits ferroptosis by reducing ubiquinone (CoQ) to ubiquinol, working in concert with GPX49. Biomarkers such as glutathione (GSH) and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) also play significant roles in ferroptosis. GSH, which serves as a substrate for GPX4, neutralizes peroxides and mitigates oxidative stress (OS)5. GSH depletion leads to ROS accumulation, LPO and membrane rupture10. ROS accumulation further damages organelles, such as mitochondria11 and endoplasmic reticulum12, activating OS pathways such as Keap1–Nrf2/ARE13,14. Ferroptosis is particularly prevalent in the central nervous system (CNS), given high lipid content (~60%), elevated oxygen consumption (~20% of total) and limited antioxidant capacity for the brain15,16,17. In addition, iron content rich in the brain also enhances susceptibility to ferroptosis18, making it a critical factor in diverse neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), epilepsy, stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI) and spinal cord injury (SCI), as listed in Table 1.

Transcriptional regulation plays a key role in initiating pathological processes. Transcription factors (TFs) regulate gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences19. At least 11 TFs are involved in modulating ferroptosis in CNS disorders through their effects on iron metabolism, antioxidant defense and LPO (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2, TFs exert divergent roles in ferroptosis depending on the pathway and context, with their function determined by the target genes they regulate. For example, within antioxidant defenses, p53 inhibits ferroptosis by inducing GLS2 to increase GSH levels and decrease ROS levels in ovarian cancer20. However, in several types of tumor cell, p53 could promote ferroptosis by repressing expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 gene (SLC7A11) to enhance OS21.

a The general scheme of TFs regulating ferroptosis in CNS. Overview of the role of TFs in regulating ferroptosis through three following aspects: iron accumulation, antioxidant defense and LPO. The relevant TFs for each mechanism are listed. b TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and other forms of cell death. The illustration shows the interaction between ferroptosis and other types of cell death, such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy, necroptosis and cuproptosis. ⟶, activation; ⊣, inhibition. Figure created with BioRender.com.

This Review examines the roles of TFs in ferroptosis, their influence on neurological disease pathophysiology, and their potential as therapeutic targets. By synthesizing recent insights and addressing existing gaps, this Review aims to inform future research and the development of targeted therapies that leverage ferroptosis-associated TFs, offering promising avenues for treating debilitating neurological conditions.

Regulatory roles of TFs on ferroptosis

TFs on ferroptosis processes

TFs regulate gene expression by binding to the promoter region of target gene during ferroptosis, subsequently reshaping brain function. This section systematically explores the pivotal role of TFs in modulating ferroptosis processes, including iron metabolism, antioxidant defense and LPO.

Role of TFs on ferroptosis-associated iron metabolism

Iron plays multiple roles in metabolic processes and is an essential cofactor and a catalyst of oxidative reactions. Intracellular iron homeostasis is controlled through iron uptake, storage, and export. Transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) mediates the transportation of ferric iron (Fe³⁺)22, which is then reduced to ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) and released into the labile iron pool via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1). Fe²⁺ drives the Fenton reaction, generating hydroxyl radicals (•OH) that promote LPO, a hallmark of ferroptosis. Excess iron is sequestered by ferritin and it can be exported via ferroportin (FPN)23. Iron accumulation accelerates ferroptosis24, and TFs are essential for the expression of key genes involved in iron metabolism, such as TFR1, ferritin and FPN25. Upon cellular iron uptake, Sp1 upregulates transferrin receptor (TFRC) transcription, enhancing TFR1 expression and promoting ferroptosis in coxsackievirus B3 infection HeLa cells26. Sp1 overexpression increases the promoter activity of TFRC27. During AD-like induced pluripotent stem cell (hIPSC) differentiation, TFR1 expression rises steadily, and silencing TFR1 reduces iron levels28. Moreover, Nrf2 binds to SLC40A1, triggering iron export through upregulation of ferritin plasma nonheme iron transport protein 1 (FPN1), which subsequently suppresses ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury rats. In summary, TFs play a critical role in ferroptosis regulation through iron metabolism, highlighting them as potential therapeutic targets for neurological diseases.

Role of TFs on ferroptosis-associated antioxidant defense

Antioxidant defense systems against ferroptosis mainly including system Xc−–GSH–GPX4 axis and CoQ system29,30. System Xc− mediates cystine uptake, which is reduced to cysteine for GSH synthesis. As a critical cofactor of GPX4, GSH enables the reduction of phospholipid hydroperoxides to alcohols, thereby preventing membrane peroxidation. An CoQ system can resist ferroptosis independently of GPX4. FSP1 and mitochondrial DHODH reduce CoQ to ubiquinol (CoQH2), which scavenges lipid peroxyl radicals. While FSP1 generates a cytoplasmic pool of CoQH2, DHODH maintains mitochondrial redox homeostasis, together forming a complementary network5. Antioxidant defense mechanisms protect against mitochondrial dysfunction and cell membrane rupture by inhibiting ROS accumulation and LPO—key events in ferroptosis31. TFs are indispensable for regulating the expression of antioxidant defense-related genes32. For example, ATF3 represses SLC7A11 expression, reducing GSH levels and GPX4 activity, thus promoting ferroptosis in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts33. By contrast, ATF4 upregulates SLC7A11 to strengthen antioxidant capacity and suppresses ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes34. p53 shows context-dependent effects, promoting ferroptosis through SLC7A11 repression in H1299 tumor cells21. From a biochemical perspective, the overexpression of ATF3 prevents p53 from hindering MDM2-mediated degradation and leads to increased transcription of p53-regulated promoters in H1299 and HCT116 cell models35. However, the synergistic effect between ATF3 and p53 when binding to SLC7A11 has not yet been observed. NRF2, by activating the system Xc−–GPX4 axis and FSP1 to reduce redox status, protects neurons from ferroptosis in mouse models of TBI36. These TFs influence cytosolic and mitochondrial ROS accumulation and LPO, directly impacting neurological functions. Excessive ROS disrupts redox balance, impairing neurogenesis and synapse formation37. Antioxidant defenses protect neuronal proliferation by reducing OS, while dysregulated ROS promote excessive synaptic pruning and gliosis38. Moreover, ROS-driven ferroptosis in glial cells exacerbates neuroinflammation, affecting glial proliferation and phagocytic activity39. These findings indicate that TFs regulating antioxidant defense in ferroptosis have dual effects on neural function.

Role of TFs on ferroptosis-associated LPO

LPO is one of the most critical processes in ferroptosis. This process involves the oxidative modification of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) within cellular membranes, leading to the generation of lipid peroxides40. Enzymes such as acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) play central roles in this pathway. ACSL4 catalyzes the free PUFAs to reactive intermediates, while LPCAT3 incorporates them into membrane phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylethanolamine. These PUFA-phosphatidylethanolamine species then undergo peroxidation, contributing to ferroptosis41. LPO-induced membrane rupture is a significant mechanism underlying ferroptosis42. Enzymes such as Alox1543 and SAT144 control LPO and, consequently, ferroptosis. TFs are essential regulators of their transcriptions. It has been shown that p53 directly binds to SAT1, leading to Alox15 expression in H129945, which catalyze lipid hydroperoxide generation to promote ferroptosis46. Sp1 suppresses SAT1 transcription to reduce ferroptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells, while Nrf2 interacts with acetyl-CoA carboxylase to mitigate LPO during ferroptosis47,48. Therefore, Alox15 and SAT1 are critical genes in the regulation of LPO process. In the CNS, LPO plays a key role in regulating astrocytic reactivity. For instance, high-fat diet-induced LPO increases the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the hippocampus, a specific marker of astrocytes. Excessive astrocytic reactivity can exacerbate neuroinflammation and neuronal damage49.

TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and other forms of cell death

Effects of TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy

Autophagy is characterized by the formation of autophagosomes, with ATG5 serving as a critical biomarker of its upregulation50. Ferroptosis and autophagy are closely interconnected51, and TFs play a central role in regulating their complex interactions. Nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) is a key TF regulator that links ferritinophagy to autophagy, acting as a central hub in this process. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis is tightly regulated by TFs, which affect the degradation of key proteins (for example, GPX4, SLC7A11) and modulate iron homeostasis. Notably, TMEM164 and STING1 have been identified as TF-regulated factors that promote ferroptosis by activating autophagy and LPO52. Conversely, TFs such as NF2 and YAP inhibit ferroptosis by enhancing antioxidant defenses53. The context-dependent roles of these TFs highlight their therapeutic potential in diseases where ferroptosis and autophagy are implicated, particularly through NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy mechanisms. In sepsis-associated encephalopathy, hippocampal ferroptosis is activated and then contributes to cognitive dysfunction. Liproxstatin-1 effectively inhibits ferroptosis and enhances autophagy, alleviating this impairment by suppressing ferroptosis via TFR1 degradation54. These findings suggest that targeting TF involving in the crosstalk between ferroptosis and autophagy may offer a promising therapeutic approach to treat neurological disorders.

TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and apoptosis

Apoptosis is marked by caspase-3 activation and the formation of apoptotic bodies55. Key biomarkers in apoptosis include antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and proapoptotic proteins suxh as Bax. Apoptosis has been shown to interact with ferroptosis56. TFs such as C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and ATF4 mediate the crosstalk between these two forms of cell death. Treatment with ferroptosis-inducing agents artesunate (an inhibitor of GSH S-transferase) activate the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4-CHOP pathway, and CHOP, in turn, promotes the expression of PUMA, a proapoptotic protein, linking ferroptosis to apoptosis. This interaction suggests that combining ferroptotic and apoptotic therapies may enhance anticancer efficacy57. In the early stages of PD, stages have been associated with iron overload, which can trigger p53-dependent ferroptosis followed by apoptosis by apoptosis. Notably, ferroptosis inhibitors such as ferrostatin-1 and desferrioxamine not only suppress ferroptosis but also abolish the subsequent apoptosis24. While there is limited research on the role of TFs in the interplay between ferroptosis and apoptosis in neurological diseases, studies in other fields suggest that these TFs could serve as novel therapeutic targets.

TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and pyroptosis

Pyroptosis, a caspase-1-mediated form of cell death, involves the cleavage of gasdermin D, which releases its N-terminal domain to form membrane pores, resulting in cell swelling and lysis58. This process is intricately linked to ferroptosis. TFs such as Nrf2, HIF-1α and TP53 regulate the crosstalk between ferroptosis and pyroptosis. Nrf2 promotes antioxidant responses and inflammation via the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in PD59, influencing cell death pathways60. HIF-1α promotes pyroptosis under hypoxic conditions while exacerbating ferroptosis through LPO61. p53 modulates ferroptosis by regulating iron metabolism and antioxidant genes, while also influencing pyroptosis through caspase-3 activation21. Shared signaling pathways, such as ROS and iron metabolism, highlight the interdependence of these cell death mechanisms. Ferroptosis and LPO are critical in the pathology of AD and PD, with β-amyloid deposition and iron metabolism abnormalities being central features. Pyroptosis, mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome, exacerbates neuroinflammation through IL-1β release, accelerating neuronal degeneration. Together, these processes contribute to cognitive decline and motor dysfunction. MCC950, an NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, reduces pyroptosis and inflammatory factor release, indirectly alleviating ferroptosis62. Targeting these TFs could provide novel therapeutic strategies for diseases involving pyroptosis.

TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and necroptosis

Necroptosis, a form of programmed cell death, is characterized by the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIPK3)63. While both ferroptosis and necroptosis are forms of cell death, they operate through distinct mechanisms. Ferroptosis is driven by oxidative damage and iron metabolism, whereas necroptosis is typically associated with uncontrolled cell swelling and membrane rupture via the RIPK–MLKL pathway64. Both ferroptosis and necroptosis are regulated forms of nonapoptotic cell death with distinct yet interconnected mechanisms, with TFs playing a critical role in their crosstalk. Nrf2, for example, suppresses ferroptosis by enhancing antioxidant defenses, while RIPK3 in necroptosis promotes LPO as a consequence of ROS and lipid peroxide accumulation65. The crosstalk between these pathways involves shared signaling nodes such as ROS and lipid metabolism, through which TFs influence cell fate. In a cerebral ischemia–reperfusion mouse model, iron, a key catalyst for LPO, promotes ferroptosis66. In necroptosis, iron amplifies OS, driving RIPK1–MLKL pathway activation and further promoting ferroptosis67. This crosstalk between ferroptosis and necroptosis plays a significant role in neurological disorders, highlighting the potential for developing novel therapies targeting this interaction.

TFs on the crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis

Cuproptosis, a form of copper-induced cell death, is linked to mitochondrial stress and damage, particularly in cells relying on oxidative phosphorylation for energy production68,69. It is triggered when intracellular copper levels exceed a specific threshold and involves a rare lysine post-translational modification known as protein fatty acylation. This modification leads to the accumulation of fatty-acylated proteins, disrupting normal mitochondrial metabolism and inducing cell death. Key biomarkers such as FDX1, LIAS and DLAT are involved in cuproptosis promotion70. Ferroptosis and cuproptosis share a mitochondrial connection. Both are metal ion-dependent forms of cell death—ferroptosis results from iron accumulation, while cuproptosis is triggered by excessive copper. Both processes involve mitochondrial metabolic disruptions: cuproptosis impairs the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle, leading to proteotoxic stress, while ferroptosis causes cell membrane damage via LPO71. Copper exacerbates ferroptosis by targeting GPX4, a lipid repair enzyme. OS is a common driver of both processes, with ROS acting as a key mediator. PANoptosis is an inflammatory programmed cell death pathway characterized by key features of pyroptosis, apoptosis and/or necroptosis. This is precisely the origin of the ‘P’, ‘A’ and ‘N’ in the term PANoptosis. Copper-induced ROS not only promote ferroptosis but also trigger PANoptosis, a highly coordinated inflammatory programmed cell death featured by the formation of PANoptosome72, suggesting shared inflammatory mechanisms73,74. circSpna2 interacts with the ubiquitin ligase Keap1 to modulate the NRF2-Atp7b signaling pathway and influences cuproptosis in the brain. Mechanistically, circSpna2 targets the DGR domain of Keap1 to alleviate NRF2 ubiquitination. Overexpression of circSpna2 alleviates cuproptosis post-TBI through the Keap1–NRF2–Atp7b axis75. NRF2 activation also directly upregulated a series of antioxidases including GPX4, which inhibited the ferroptosis process. These evidences hint that potential crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis pathways could occur in CNS diseases. Although the regulation of TFs in the crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis has not been reported, investigating this interplay holds therapeutic potential for neurological disease treatment. Experimental evidence is essential to obtain regarding TF-mediated interactions between ferroptosis and cuproptosis, which has therapeutic value for disease alleviation in the future.

Proposed roles of ferroptosis-associated TFs in the emerging hallmarks of neurological diseases

Effect of ferroptosis-associated TFs on protein aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation

Protein aggregation is a prominent molecular hallmark of various neurological disorders, including AD and PD. In AD, the formation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are hallmarks of the disease76. Aβ plaques consist of aggregated Aβ peptides, which are neurotoxic, while neurofibrillary tangles are composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, which disrupts normal microtubule function in neurons77. TFs related to ferroptosis can impact the development of AD through multiple mechanisms, such as regulating genes involved in Aβ metabolism. For example, Nrf2 downregulates the expression of BACE1 and BACE1-AS by binding to ARE sites in their promoters78. In Nrf2-deficient AD mice, BACE1 and BACE1-AS (BACE1 antisense RNA) levels are increased, leading to greater Aβ plaque formation and more serious cognitive impairment79. However, increased Nrf2 and decreased BACE1 and BACE1-AS, reduces Aβ production and alleviates cognitive and AD-related pathologies79. It hints that the intimate relationship between Nrf2 and BACE1 or BACE1-AS. Overexpression of p53 is also found to inhibit BACE1 expression, potentially reducing APP processing and Aβ generation80. TFEB enhances Aβ uptake and its colocalization with LysoTracker-stained organelles, thereby promoting Aβ clearance81. HIF-1α plays a dual role by upregulating β/γ-secretases and downregulating α-secretases, which increases Aβ production. These findings suggest that ferroptosis-associated TFs significantly promote Aβ deposition. In PD, α-synuclein aggregation into Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites are key pathological features82. These aggregates are toxic to dopaminergic neurons, impairing their function and contributing to both motor and nonmotor symptoms in patients with PD83. Several ferroptosis-associated TFs have been shown to regulate α-synuclein aggregation84. Overexpression of TFEB promotes α-synuclein clearance and prevents ferroptosis, offering better protection in the prevention or treatment of PD85. STAT3 activation through the IL6/IL6R/IL6ST complex increases in α-synuclein-induced PD mice, promoting α-synuclein aggregation86. Nrf2 activation reduces α-synuclein accumulation by inhibiting ferroptosis through the Nrf2–heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) pathway87. In addition, dysregulation of NF-κB may significantly contribute to PD pathogenesis by promoting the accumulation, aggregation and spreading of α-synuclein82. Ferroptosis-associated TFs play a pivotal role in modulating α-synuclein aggregation, and targeting these TFs and their associated pathways may offer novel therapeutic strategies for PD by regulating α-synuclein aggregation. In AD, tau hyperphosphorylation is another prominent feature88. Research has demonstrated that ferroptosis-related TFs can influence hyperphosphorylated tau protein and potentially improve AD prognosis. HIF-1α has dual roles in AD: it can upregulate β/γ-secretases and downregulate α-secretases, thus increasing Aβ generation, while also combating Aβ toxicity and restraining tau hyperphosphorylation89. p53 affects the p-tau/tau ratio, and although no significant changes in tau levels are observed in mice model, the p-tau/tau ratio differs notably. Treatment with cerebroprotein hydrolysate-I reduces this ratio in APP/PS1 mice44. TFEB promotes Aβ uptake and its colocalization with LysoTracker-stained organelles, influencing tau pathology by clearing abnormal tau proteins and alleviating neurotoxicity90. Furthermore, disruption of HNF-4A due to histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2)-induced deacetylation upregulates AMPK, contributing to tauopathy. Utilizing miR-101b mimics or AMPK small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) can rescue tau pathology and improve memory deficits91. These ferroptosis-associated TFs play essential roles in tau hyperphosphorylation, underscoring their clinical value as potential therapeutic targets for neurological diseases especially AD.

Effect of ferroptosis-associated TFs on OS

OS, characterized by an imbalance between ROS/reactive nitrogen species generation and antioxidant defenses, is a critical factor in various neurological diseases. It induces neuronal damage and death through mechanisms such as LPO, protein oxidation and DNA damage92. Several ferroptosis-associated TFs have been shown to modulate OS. For example, p53 inhibition improves cell viability and reduces LPO and malondialdehyde (MDA) content in IRP2-overexpressed ferroptotic PC12 cells93. Overexpression of HIF-1α increases the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4, upregulates GSH levels and reduces LPO and ROS levels induced by 6-OHDA94. Similarly, Sp1 overexpression diminishes ROS generation in erastin-stimulated ferroptosis in Lund human mesencephalic cell95. These ferroptosis-associated TFs are essential in modulating OS, offering potential therapeutic strategies for PD. In epilepsy research, various TFs have been found to influence mitochondrial dysfunction and OS. Nrf2 activation enhances the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), GSH-Px and GPX4, thus reducing OS96. Overexpression of TFEB promotes autophagy and lysosome biogenesis, which aids in clearing damaged mitochondria and alleviating OS97. ATF4 activation increases xCT expression, boosting GSH synthesis and mitigating OS, thereby alleviating ferroptosis98. These TFs play pivotal roles in mitochondrial dysfunction and OS, providing promising new avenues for treating epilepsy. In AD, several TFs influence OS. Sp1 is implicated in Aβ-induced LPO. The Sp1 and ACSL4 signaling pathway participates in Aβ-induced changes in cell survival, cardiomyocyte contractile dysfunction and LPO. Upregulation of Sp1 helps prevent OS, thereby simultaneously suppressing ferroptosis and alleviating AD pathology99. ATF4 is involved in the regulation of ferroptosis in AD through the PERK–ATF4–HSPA5 pathway. The sh-HSPA5 virus reduces MDA activity and increases the activity of GSH, GSH-Px and SOD in the hippocampal tissue of AD mice100. Nrf2 activation enhances the expression of SOD, GSH-Px and GPX, reducing MDA levels and OS. This not only inhibits ferroptosis but also suppresses the accumulation of ROS, thereby alleviating OS in AD101. These findings suggest that certain TFs regulate both ferroptosis and the pathological processes in AD. In stroke, TFs HIF-1α and STAT3 regulate ischemia–reperfusion-dependent expression of neuronal polymerase I and transcript release factor (PTRF) through promoter binding, which increases ROS levels and ferroptosis102. Moreover, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 1 (SATB1), a TF predominantly localized in neurons103, has been shown to influence ferroptosis. Experimental data have demonstrated that Danhong injection inhibits ferroptosis via the SATB1–SLC7A11–HO-1 axis, reducing MDA levels and enhancing SOD and GSH activities in permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (p-MCAO) mouse model of stroke, suggesting a reduction in lipid oxidation104. These results underscore the critical role of ferroptosis-associated TFs in regulating OS in stroke. In TBI, excessive ROS production leads to LPO and ferroptosis105. Experimental data indicate that blocking the thrombin receptor PAR1 reduces cortical iron deposition and serum transferrin levels while simultaneously enhancing Nrf2 and antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and GPX4. This reduces LPO in a repetitive TBI model106. These findings highlight the role of Nrf2 in counteracting ferroptosis and oxidative injury in the injured brain. Thus, targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs, particularly those regulating antioxidant defenses, offers a promising therapeutic strategy for TBI.

Effect of ferroptosis-associated TFs on neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation, driven by activated microglia and astrocytes that release proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, plays a pivotal role in neurological diseases107. Dysregulation of iron metabolism and OS in ferroptosis can trigger the activation of microglia and astrocytes, further promoting the release of proinflammatory factors108. There are some ferroptosis-related TFs have been shown to influence neuroinflammation in AD. For instance, Nrf2 activation enhances the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 while reducing proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF109. STAT3 activation via the cGAS-STING pathway amplifies inflammatory responses, but the absence of IL-6 mitigates this activation and reduces neuroinflammation110. NF-κB is a critical regulator of neuroinflammation, with its activation promoting the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Adiponectin inhibits amyloid-β oligomer-induced proinflammatory cytokine production in microglia through the AMPK–NF-κB pathway111. Although the coexistence of neuroinflammation and ferroptosis in AD remains unobserved, ferroptosis-associated TFs are integral to neuroinflammation. Targeting these TFs may offer novel therapeutic strategies for AD. In PD, HSF1 overexpression reduces microglial activation and reverses cytokine alterations112. NF-κB inhibition decreases inflammatory factor production by upregulating Nurr1 and TH while downregulating α-syn expression. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling in microglia leads to a reduction in inflammatory cytokine levels113. While no direct link between ferroptosis and neuroinflammation has been established for these TFs, their roles in neuroinflammation in PD are significant. Modulating these TFs may open new avenues for PD therapy. In epilepsy, multiple TFs have been reported to influence neuroinflammation. NF-κB activation promotes the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF114. STAT3 activation also increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines115. Nrf2 activation mitigates proinflammatory cytokine production by inhibiting ferroptosis116. Ferroptosis-associated TFs play a critical role in neuroinflammation, and modulating both TFs and neuroinflammation offers promising therapeutic avenues for epilepsy. Several TFs contribute to ischemic inflammatory responses, with those influencing ferroptosis showing satisfactory therapeutic potential117,118. HIF-1α directly interacts with the promoter of ferritin light chain, an iron storage protein, enhancing its expression119. In models of oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD) and middle cerebral artery occlusion, HIF-1α activation reduces proinflammatory cytokines (TNF and IL-6) and downregulated COX-2 and iNOS expression, indicating a protective role in neuroinflammation via ferroptosis-related mechanisms119. Targeting these factors thus holds promise for alleviating neuroinflammatory damage following stroke. In TBI, network pharmacology analysis reveals TBI-induced upregulation of p53, which contributes to the inflammatory response120. Conversely, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, a transcriptional regulator, suppresses inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB activity, thereby reducing proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18106. Both p53 and NF-κB are closely associated with ferroptosis in various pathological models121,122. Therefore, targeting ferroptosis-related TFs to reduce excessive neuroinflammation is a key strategy for amelioration of brain injury. In SCI, acacetin has been demonstrated to increase NeuN level and reduce glial fibrillary acidic protein and Iba-1 levels, alongside a decrease in proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18 and TNF) post SCI123. Notably, these effects were reversed by inhibiting Nrf2, implicating the Nrf2–HO-1 signaling axis in the anti-inflammatory response123. Further investigation is needed to clarify the role of TFs in ferroptosis and neuroinflammation during SCI.

Effect of ferroptosis-associated TFs on neuronal hyperexcitability

Neuronal hyperexcitability, a hallmark of epilepsy, arises from factors such as ion channel dysfunction, glutamate receptor overactivation and reduced GABAergic inhibition124. This hyperexcitability leads to excessive synchronous neuronal firing, resulting in seizures and other clinical manifestations of epilepsy125. Ferroptosis contributes to neuronal hyperexcitability in epilepsy through dysregulation of iron metabolism and OS, which can impair neuronal membrane potential and ion channel function126. For instance, iron overload may elevate ROS production, exacerbating neuronal hyperexcitability. Several TFs influence neuronal hyperexcitability. Nrf2 activation reduces ROS levels and OS, mitigating neuronal hyperexcitability127. TFEB overexpression promotes autophagy and lysosome biogenesis, facilitating the clearance of damaged mitochondria and reducing neuronal hyperexcitability97. STAT3 activation upregulates proinflammatory cytokines, further enhancing neuronal hyperexcitability96,128. Ferroptosis-associated TFs play pivotal roles in modulating neuronal hyperexcitability, and targeting these TFs and their pathways could offer novel therapeutic approaches for epilepsy.

Effect of ferroptosis-associated TFs on neurogenesis

Neurogenesis, the generation of new neurons, is crucial in epilepsy129. It is influenced by several factors such as seizures, OS and neuroinflammation. Impaired neurogenesis may contribute to the onset and progression of epilepsy130. Ferroptosis can disrupt neurogenesis in epilepsy by affecting iron metabolism and inducing OS, leading to damage of neural stem and progenitor cells and reducing neurogenesis. Various TFs impact neurogenesis. Nrf2 activation protects neural stem cells from oxidative damage and promotes neurogenesis131. TFEB overexpression enhances autophagy and lysosome biogenesis, aiding the clearance of damaged mitochondria and supporting neurogenesis97. STAT3 activation impedes neurogenesis by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines132. Ferroptosis-associated TFs play significant roles in neurogenesis, and modulating these TFs and their pathways could provide novel therapeutic strategies for epilepsy.

Collectively, according to the discussions of roles of ferroptosis-associated TFs in various neurological diseases (Fig. 3 and Table 2), it indicates that they are vital in regulating hallmarks of these diseases.

The figure shows how TFs affect ferroptosis in neurological diseases (for example, AD, PD, epilepsy and stroke) and their relationships with disease phenotypes. a In AD, TF-mediated regulation of ferroptosis is linked to disease phenotypes such as Aβ deposition, tau hyperphosphorylation, OS and neuroinflammation. b In PD, TF-mediated regulation of ferroptosis is involved in its disease phenotypes such as α-synuclein aggregation, OS and neuroinflammation. c In epilepsy, ferroptosis-related TFs can affect neuronal hyperexcitability, mitochondrial dysfunction, neuroinflammation and neurogenesis. d In stroke, ferroptosis-associated TFs regulate the formation of thrombus, OS and neuroinflammation. PUFA-CoA, polyunsaturated fatty acyl–coenzyme A; PUFA-PL, polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids; PLOOH, phospholipid hydroperoxides; STEAP3, six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; FTL, ferritin light chain; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; GSSG, oxidized GSH; R-OH, hydroxylated lipid; R-OOH, lipid hydroperoxide; SLC3A2, solute carrier family 3 member 2; PLA2G4, phospholipase A2 group IVA; ⟶, activation; ⊣, inhibition.

Coordination of epigenetic regulators and ferroptosis-associated TFs on neurological diseases

TFs and epigenetic regulators coordinate to maintain cell homeostasis. It has been shown that ferroptosis-associated TFs and various forms of epigenetic modification including DNA methylation, histone post-translational modification (PTM) and noncoding RNA (ncRNA) can interact to manipulate neurological disease process (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

a–c The representative examples indicating the coordination of ferroptosis-associated TFs and DNA methylation, histone PTM and ncRNA in neurological diseases, respectively. Ub, ubiquitination; Ac, acetylation; ↓, downregulation; ⟶, activation; ⊣ inhibition. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Ferroptosis-associated TFs cooperating with DNA methylation

The methylation status of the promoter of TFs greatly affects its gene expression. For example, in AD-like cell model induced by expressing human Swedish mutant amyloid precursor protein (N2a/APPswe), it was found that treatment with DNA methyltransferases inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine significantly facilitated the increase of Nrf2 at gene and protein levels via DNA demethylation133, which was accompanied with high expression of Nrf2 downstream target gene including NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductas (NQO1) after the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 occurred. Although the effect of Nrf2 promoter demethylation by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine on ferroptosis cannot be detected in this study, NQO1 is a well-known target to counteract OS134, an significant molecular trait for ferroptosis, which is positively regulated by Nrf2 promoter demethylation. It implicates that Nrf2 methylation promotes ferroptosis process via decreasing its nuclear translocation and gene expression, finally exacerbating AD pathology. In addition, there are other ferroptosis-associated TFs including p53135 and NFYA136, which are subject to DNA methylation and linked with neurological diseases, although the detailed molecular mechanism which regulates ferroptosis is unknown.

Ferroptosis-associated TFs cooperating with histone PTMs

Histone PTMs, including acetylation and phosphorylation, play a significant role in the regulation of ferroptosis-associated TFs137. These modifications can influence the binding of TFs to the DNA sequence, thereby affecting gene expression and cellular processes related to ferroptosis in neurological diseases. The interplay between histone PTMs and ferroptosis-associated TFs includes two aspects as follows: effect of enzymes involving histone PTMs on the activity of and ferroptosis-associated TFs and effect of TFs on the histone PTMs within the target gene. The interaction between histone PTMs-associated enzymes and TFs is crucial for the regulation of ferroptosis-related gene transcription. For instance, it has been demonstrated that HDAC9 increases the protein level of HIF-1 by deacetylation and deubiquitination, thus promoting the transcription level of the proferroptotic TFR1 gene138. In the meantime, activation of HDAC9 also triggers the decrease of Sp1 via deacetylation and ubiquitination, ultimately facilitating neuronal ferroptosis due to reduction of the anti-ferroptotic GPX4 gene in vitro brain ischemia induced by glucose deprivation plus reoxygenation (OGD/Rx)138. Furthermore, intracerebroventricular injection of siHDAC9 is also reported to prevent the increases of HIF-1 and TFR1 transcription and the reduction of Sp1 and its target gene GPX4, finally decreasing a well-known marker of ferroptosis 4-hydroxynonenal release in vivo ischemic stroke mouse model caused by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (t-MCAO)138. These results indicate that HDAC9-mediated histone deacetylation can promote neuronal ferroptosis via either activation of HIF-1-dependent TFR1 transcription or blockade of Sp1-mediated GPX4 transcription. In addition, it has also shown that HDAC2, another member of histone PTMs-associated enzyme, suppresses the Nrf2 activity via its deacetylation and repression of nuclear translocation in a neonatal rat model of hypoxic–ischemic brain injury139. Inhibition of HDAC2 can partially retard neuronal ferroptosis in HIBI neonatal rats.

Histone PTMs can also influence their interaction with TFs and subsequent transcriptional regulation. For example, genetic silencing of a well-known histone acetyltransferase KAT6B reduces the enrichment of histone H3 lysine 23 acetylation on the STAT3 promoter region in glioma cell lines including U251 and LN229140. Conversely, overexpression of KAT6B suppresses erastin-induced lipid ROS and ferroptosis in these cells and deletion of STAT3 reverses KAT6B-mediated glioma cell ferroptosis. These data suggest that KAT6B facilitates glioma progression via suppressing ferroptosis through epigenetic activation of STAT3. In the aspect effect of TFs on the histone PTMs within the target gene, it has been shown that the phosphorylation of STAT3 occurs in neurons of a mouse cerebral ischemia model subject to middle cerebral artery occlusion and promotes proinflammatory reactions115. Local STAT3 deficiency via in vivo injection of STAT3 shRNA results in decreases of histone H3 and H4 acetylation on the NLRP3 promoter and the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome, finally inhibiting inflammatory reaction. Although this phenomenon regarding the effect of TFs on histone acetylation within the target gene following ferroptotic condition remains unknown, it is still a critical direction requires to be explored in the future.

Ferroptosis-associated TFs cooperating with ncRNAs

ncRNAs play crucial roles in regulating ferroptosis-associated TFs in neurological diseases including long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), microRNA and so on. They act through various mechanisms, such as competing with endogenous RNA, directly binding to TFs, or modulating signaling pathways, thereby affecting the pathogenesis of neurological disorders. In the SCI rat model, lncRNA OIP5-AS1 expression is downregulated, and lncRNA OIP5-AS1 deficiency further triggers the decrease of Nrf2 level by less sponging miR-128-3p, finally promoting ferroptosis and apoptosis in neural stem cells141. By contrast, overexpression of lncRNA OIP5-AS1 inhibits ferroptotic cell death and improves the functional recovery of SCI by increasing the level of Nrf2. The addition of miR-128-3p blocks the contributory effect of lncRNA OIP5-AS1 on Nrf2 protein level141. These results indicate that lncRNA OIP5-AS1 inhibits ferroptosis of SCI cells dependent upon downregulation of miR-128-3p. Moreover, circBBS2 is reported to be lowly expressed and ferroptosis is triggered in a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion142. Increase of circBBS2 by umbilical cord–mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes is shown to suppress ferroptosis via sponging miR-494 to augment SLC7A11 level, finally facilitating the recovery of ischemic stroke. Despite little investigation on the relationship between cirRNA and TFs under ferroptotic condition, it is an impressive area due to the vital role of the regulation of cirRNA on TFs in the field of neuroscience143. Taken together, coordinations with ferroptosis-associated TFs and ncRNAs especially lncRNAs and circRNAs play a critical role in neurological diseases. Understanding these interactions provides valuable insights into potential therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases.

Therapeutic approaches to combat neurological diseases via targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs in preclinical models

It is well established that targeting TFs alone is usually undruggable. However, there are so far several promising therapeutic approaches indirectly affecting the function of TFs, which includes modulators of TFs cofactors, TFs-mediated PTMs and TFs-associated ncRNAs (Fig. 5), as elaborated in the following section.

Targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs presents a promising therapeutic avenue for treating neurological disorders. Three sorts of therapeutic approaches including TF cofactor modulators, TF-mediated PTMs and TF-associated ncRNAs are proposed. Ub, ubiquitination; 3′UTR, 3′ untranslated region; E3, ubiquitin–protein ligase; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; KEAP1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; ARE, antioxidant response element; ↑, upregulation; ↓, downregulation; ⟶, activation; ⊣ inhibition.

Modulators of TFs cofactors

Since the biological function of TFs is exerted via interaction of large amounts of transcriptional cofactors to influence RNA polymerase II activity, intervention of TF–cofactor interaction is an intriguing therapeutic strategy. The TF Nrf2 has been demonstrated to bind to a dimeric KEAP1 with two binding motifs, DLG and ETGE144,145. RTA-408, a structural analog of bardoxolone methyl, activates Nrf2 by inhibiting KEAP1 through binding to the C151 site of the KEAP1. The binding leads to the stabilization and nuclear translocation of Nrf2, upregulating the expression of antioxidant protective genes, such as NQO1. Furthermore, RTA-408 has been proved that inhibits ROS and mitochondrial depolarization. Based on mentioned above, ROS accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction are vital inducers for ferroptosis146. Due to the satisfactory penetration into the brain, RTA-408 has proved its safety and efficacy in a phase II clinical trial for the therapeutics of Friedreich’s ataxia147. In addition, HIF is a heterodimeric TF composed of an α subunit (such as HIF-1α or HIF-2α) and β subunit (HIF-1β, also known as ARNT)148. Under normoxic conditions, PHD catalyzes the hydroxylation of Pro402 and Pro564 on HIF-1α. The hydroxylated HIF-1α and HIF-2α can then be recognized by the ubiquitin ligase VHL, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation via the proteasome pathway149. By contrast, under hypoxic conditions, PHD cannot effectively hydroxylate HIF-α, resulting in the stabilization and accumulation of HIF-α within the cell. The stabilized HIF-α subunit enters the nucleus, where it forms a complex with HIF-1β, activating the expression of a series of target genes. As a type of intracranial tumor, the location and size of glioma may have a direct impact on the cerebral neuronal activity150. When it presses or intrudes into certain areas, it may cause abnormal neuronal discharge, which in turn triggers seizures. The frequency and severity of seizures may vary depending on the growth, location and individual differences of the glioma in patients151. In addition to removing glioma by radiotherapy or chemotherapy to alleviate seizures, researchers found the Roxadustat, a prolyl hydroxylase PHD inhibitor activating HIF-α. Activation of HIF-α induces ferroptosis, especially the activation of HIF-2α upregulates lipid regulatory genes, mainly promoting LPO during ferroptosis152. Although the promotion of Roxadustat to ferroptosis cannot alleviate seizures, it still provides a novel insight to develop a PHD activator to treat epilepsy. Taken together, the above evidences support that TFs cofactors are crucial targets for the treatment of CNS disorders.

TF-mediated PTMs

There are multiple types of PTM within TFs and PTMs can regulate subcellular localizations, protein–protein/DNA interactions and stability for TFs153, suggesting a critical role of PTMs for the function of TFs. Thus, targeting PTMs within TFs is regarded as a promising therapeutic avenue. In this area, researchers have developed proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology based on the principle of ubiquitination for degradation by adding ubiquitin molecules.

PROTAC is a chimeric compound that can promote the ubiquitination and degradation of target proteins154. The chemical probes such as pan-bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) is a structural class which can recognize and recruit BET BDs and serve as ideal PROTAC target for BET proteins. BET proteins consist of the bromodomain-containing protein (BRD) 2–4 and the testis-specific isoform BRDT. BET-targeted PROTACs dBET1, MZ1 and ARV-825 are reported to recognize and recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligase to target BRD4, leading to the deletion of BET proteins155,156,157. BET proteins influence the inflammatory process by modulating signaling pathways such as NF-κB and Nrf2158. When BET inhibitors such as JQ1 are used, an increase in the expression of Nrf2 and its target antioxidant genes can be observed, indicating that BET proteins exert inhibitory effects on Nrf2 signaling158. Applying this principle to PROTAC technology, it is possible to achieve selective degradation of BET proteins (especially BRD4) by designing PROTAC molecules specifically targeting these proteins. Given the inhibitory effect of BET proteins on Nrf2 signaling, the reduction of BET proteins is theoretically expected to activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway, thereby upregulating the expression levels of Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant genes. Since OS is a key mechanism in ferroptosis and both inhibition of oxidant reaction and enhancing antioxidant capacity can alleviate ferroptosis in epilepsy. This suggests that using PROTAC technology to decrease the level of BET proteins indirectly enhances the activity of Nrf2 and the expression of its target genes, thus strengthening the hippocampal cells’ antioxidant capacity159. Although PROTAC technology targeting TFs has not yet been reported in neurological diseases, studies suggest the therapeutic potential of PROTACs in this field. For example, the small-molecule tau PROTAC C004019, which shows great blood-brain barrier permeability, selectively promotes tau degradation and produces sustained in vivo efficacy, leading to improved synaptic and cognitive function in 3xTg transgenic mice160. Thus, TF-mediated PTMs especially PROTAC technology is a trend of therapeutics for neurological diseases.

TFs-associated ncRNAs

It has been demonstrated that ncRNAs transcription around gene promoters and enhancers can promote DNA binding of TFs to their target sites161,162, finally manipulating gene transcription, which suggests that targeting TFs-associated ncRNAs is an invaluable therapeutic approach. RNA-based therapies encompass the use of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), siRNAs, microRNAs and single-guide RNA-associated CRISPR–Cas9 technology precisely targeting and cleaving specific regions within the genome163. Researchers have discovered a dual-gene therapy system based on charge-reversible coordination-crosslinked spherical nucleic acids164. They used poly lactic acid as a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer backbone, which was modified with functionalized side chains to enable binding with ASOs and siRNA. In addition, a polyethylene glycol shell was introduced to enhance the circulation time and tumor-targeting ability of the nanoparticles. The ASOs and siRNA target the mRNA of Bcl-2 and HIF-1α, respectively, inhibiting the expression of these genes by preventing the translation of mRNA into proteins164. Nowadays, tRF3-IleAAT is a tRNA-derived fragment produced by nucleases at specific sites on tRNA. Despite no application of it in neurological diseases, treatment with tRF3-IleAAT mimics is reported to increase intracellular GSH level and decrease the content of ferrous iron in high glucose-induced mesangial cell and mouse model of Db/db diabetic kidney disease via binding to the 3′UTR of ZNF281 and negatively regulating its expression165. Further study is essential to ascertain the effect of TF-associated ncRNAs on neurological diseases.

Promising ferroptosis-associated TFs as novel therapeutic targets to treat neurological diseases

As mentioned above, ferroptosis-associated TFs have a pivotal role in improving brain dysfunction via multiple aspects. In recent years, there are some clinical evidences supporting that targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs show therapeutic implications for the treatment of neurological diseases. For instance, omaveloxolone, an Nrf2 activator, has shown promise in treating Friedreich ataxia147. In the MOXIe trial, which is an international, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, registrational phase 2 trial, it significantly improves neurological function and displays favorable safety and tolerability. Furthermore, another Nrf2 activator dimethyl fumarate (BG-12/Tecfidera) is approved for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune-mediated neurological disorder, highlighting the successful translation of Nrf2-targeting drugs into clinical practice166. Moreover, hydralazine is also evaluated to analysis its cognition enhancement in patients with early-stage AD through Nrf2 activation167. In the realm of cancer therapy, p28, a cell-penetrating peptide targeting p53, has been studied in pediatric brain tumor patients including diverse malignancies, namely, high-grade glioma, medulloblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumors, atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or choroid plexus carcinoma, showing good tolerability168. In addition, the STAT3 inhibitor WP1066 has entered phase I trials for recurrent malignant glioma, with plans for further phase II studies169. Moreover, drugs such as fenofibrate and aspirin, which target TFEB and PPAR-α, respectively, have also shown potential in stroke prevention and AD treatment by activating PPAR-α to upregulate TFEB and increase lysosomal biogenesis170. Currently, no clear preclinical studies or drugs that have entered clinical trials have been found utilizing PROTAC technology to simultaneously target TFs and epigenetic factors for the treatment of neurological diseases such as AD, PD or epilepsy. However, researchers have successfully designed dNF-κB and dE2F, which effectively degrade endogenous p65 (an NF-κB subunit) and E2F1 proteins in cancer cells, respectively, and demonstrate superior anti-proliferative effects171. Meanwhile, PROTAC technology has been widely applied in targeting the epigenetic regulatory network. Several PROTAC molecules, including ARV-825, MZ1 and dBET1, target BRD4 for the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma172. In addition, NP8 and NH2 target HDAC6 for the treatment of multiple myeloma173. Although PROTAC technology has demonstrated technical feasibility in targeting both TFs and epigenetic factors, the combination of these two approaches—developing PROTAC drugs that simultaneously target TFs and epigenetic factors for the treatment of neurological diseases—remains an unrealized concept. In the future, with advancements in delivery technology and a deeper understanding of disease molecular mechanisms, developing such complex PROTAC strategies may become a promising direction in the field of neuropharmacology. Based on the importance of ferroptosis-related TFs in neurological diseases, it is of vital importance to explore the feasibility of ferroptosis-related TFs as novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of patients with neurological diseases in the future.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Our understanding of the regulatory role of TFs in ferropotsis processes including iron metabolism, antioxidant defenses and LPO and emerging hallmarks of diverse neurological diseases indicates the ability of ferroptosis-associated TFs to reshape brain function. Targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs via various types of strategies including TF–cofactors, TF–PTMs and TF-associated ncRNAs hold promise for the treatment of neurological disease such as AD, PD, epilepsy, stroke, TBI and SCI. For example, Nrf2 activators hydralazine successfully enters into the clinical study for assessment of its therapeutic effect on patients with AD167. In addition, other Nrf2 inducers including dimethyl fumarate (DMF) and diroximel fumarate, have been approved to treat patients with multiple sclerosis174. It is worthy to explore more therapeutic approach to treat neurological diseases via targeting ferroptosis-associated TFs in the future.

However, there are still some considerations required to clarify. First, since the therapeutic strategies including TF–cofactors, TF–PTMs and TF-associated ncRNAs mentioned above are critical for regulating the function of ferroptosis-associated TFs, it is indispensible to probe the detailed information especially in the context of neurological diseases. Second, it is also very necessary to figure out the function and accurate regulatory mechanism of ferroptosis-associated TFs in a variety of neural cell types following brain dysfunction. Third, with the technology advances in functional genomics such as CRISPR–Cas9175, it is quite necessary to draw a comprehensive picture of TFs dependencies across diverse forms of neurological diseases via implementation of these techniques. It has been demonstrated that knockout of the TF ZNF543 via CRISPR–Cas9 causes the increase of TRIM28 transcription and subsequently exacerbate PD176, which suggests that overexpression of the ZNF543 gene has therapeutic effect on PD. Moreover, the influence of gender differences on TFs is also a significant factor in the research of neurological diseases. In 3xTg AD mouse model, female mice generally exhibit higher levels of NF-κB in hypothalamic mitochondria compared with male ones. However, higher expression levels of NRF2 were observed only in the hypothalamus of aged female mice. This suggests that the expression levels of certain TFs may differ during the pathological processes of neurological diseases177. It revealed that sex difference is vital in the development of novel therapeutics of CNS diseases. Notably, single-cell CRISPR screening and spatial transcriptomics are newly emerged research tools in recent years, which facilitate the discovery of novel evidence linking ferroptosis-associated TFs to neurological diseases. The CRISPR–Cas9 system enables precise gene editing, including gene knockout (CRISPR-KO), gene inhibition (CRISPRi) and gene activation (CRISPRa)178. Researchers can perturb large numbers of genes under high-throughput conditions by constructing single-guide RNA libraries179. In complex biological systems such as the brain, cell types are highly heterogeneous180. Single-cell CRISPR screening can identify TFs regulating ferroptosis in specific brain cell types, thereby revealing cell-type-specific mechanisms of ferroptosis. Neurological disorders such as AD, PD and Huntington’s disease are characterized by selective neuronal degeneration and loss41. Ferroptosis is considered a key factor in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases181. Recent studies indicate that microglia is particularly vulnerable to iron overload-induced ferroptosis, suggesting that ferroptosis inhibitors may have therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative disorders182. Furthermore, neurons, astrocytes, and brain organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells can be used for CRISPR screening to uncover disease-associated TFs and their regulatory networks. A specific approach involves integrating the CRISPR system into hIPSCs, inducing their differentiation into various cell types such as neurons and astrocytes and subsequently conducting survival/proliferation screening, Fluorescence Activating Cell Sorting screening and single-cell transcriptomic screening to systematically study the functions of TFs183. Spatial transcriptomics is a technology that simultaneously captures gene expression profiles and spatial location information of cells, enabling the analysis of gene expression data within the original tissue context. This technology is crucial for understanding region-specific gene expression in the complex structure of the brain184. Many neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, exhibit region-specific pathological changes. By integrating neuropathology, single-cell and spatial genomics, and longitudinal clinical metadata, the Seattle Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Cell Atlas provides a unique resource for studying AD pathogenesis185. Using spatial transcriptomics, researchers can detect ferroptosis-related TFs in disease models or patient brain tissues. For instance, BAP1 has been found to suppress SLC7A11 expression, inhibiting cystine uptake and leading to LPO and ferroptosis186. Meanwhile, DJ-1 has been shown to exert neuroprotective effects and inhibit ferroptosis in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury via the ATF4–HSPA5 pathway187. By combining single-cell CRISPR screening and spatial transcriptomics, researchers can first use single-cell CRISPR screening to identify TFs and their target genes involved in ferroptosis regulation at a high-throughput level. Subsequently, spatial transcriptomics can be employed to validate the spatial expression patterns of these TFs in specific brain regions and cell types, as well as their alterations during disease progression. This integrated approach provides a unique, high-resolution analytical framework for gaining deeper insights into the complex roles of ferroptosis-related TFs in neurological disorders.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Dixon, S. J. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072 (2012).

Cao, Z. et al. Biomimetic macrophage membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles induce ferroptosis by promoting mitochondrial damage in glioblastoma. ACS Nano 17, 23746–23760 (2023).

Ahola, S. & Langer, T. Ferroptosis in mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Trends Cell Biol. 34, 150–160 (2024).

Yang, W. S. et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 156, 317–331 (2014).

Mao, C. et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature 593, 586–590 (2021).

Mishima, E. et al. A non-canonical vitamin K cycle is a potent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 608, 778–783 (2022).

Doll, S. et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 575, 693–698 (2019).

Li, W., Liang, L., Liu, S., Yi, H. & Zhou, Y. FSP1: a key regulator of ferroptosis. Trends Mol. Med. 29, 753–764 (2023).

Lancaster, G. I. & Murphy, A. J. GPX4 methylation puts a brake on ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 27, 556–557 (2025).

Davidson, A. J., Heron, R., Das, J., Overholtzer, M. & Wood, W. Ferroptosis-like cell death promotes and prolongs inflammation in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 26, 1535–1544 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Systematic identification of anticancer drug targets reveals a nucleus-to-mitochondria ROS-sensing pathway. Cell 186, 2361–2379.e2325 (2023).

Hourihan, J. M., Moronetti Mazzeo, L. E., Fernández-Cárdenas, L. P. & Blackwell, T. K. Cysteine sulfenylation directs IRE-1 to activate the SKN-1/Nrf2 antioxidant response. Mol. Cell 63, 553–566 (2016).

Bae, T., Hallis, S. P. & Kwak, M. K. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 501–514 (2024).

Mohan, M., Mannan, A., Kakkar, C. & Singh, T. G. Nrf2 and ferroptosis: exploring translational avenues for therapeutic approaches to neurological diseases. Curr. Drug Targets 26, 33–58 (2025).

Shulman, R. G., Rothman, D. L., Behar, K. L. & Hyder, F. Energetic basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Trends Neurosci. 27, 489–495 (2004).

Marschallinger, J. et al. Lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 194–208 (2020).

Xu, W. et al. The roles of microRNAs in stroke: possible therapeutic targets. Cell Transplant 27, 1778–1788 (2018).

Wang, P. et al. Mitochondrial ferritin attenuates cerebral ischaemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 12, 447 (2021).

Lambert, S. A. et al. The human transcription factors. Cell 172, 650–665 (2018).

Wang, Y. & Yi, Y. CISD2 downregulation participates in the ferroptosis process of human ovarian SKOV-3 cells through modulating the wild type p53-mediated GLS2/SAT1/SLC7A11 and Gpx4/TRF signaling pathway. Tissue Cell 89, 102458 (2024).

Jiang, L. et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 520, 57–62 (2015).

Han, C. et al. Ferroptosis and its potential role in human diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 239 (2020).

Costa, I. et al. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and their involvement in brain diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 244, 108373 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Ferroptosis was more initial in cell death caused by iron overload and its underlying mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 152, 227–234 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Nrf2 activators for the treatment of rare iron overload diseases: from bench to bedside. Redox Biol 81, 103551 (2025).

Yi, L. et al. TFRC upregulation promotes ferroptosis in CVB3 infection via nucleus recruitment of Sp1. Cell Death Dis. 13, 592 (2022).

Ru, Q. et al. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 9, 271 (2024).

Kang, T., Han, Z., Zhu, L. & Cao, B. TFR1 knockdown alleviates iron overload and mitochondrial dysfunction during neural differentiation of Alzheimer’s disease-derived induced pluripotent stem cells by interacting with GSK3B. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29, 101 (2024).

Xie, Y., Kang, R., Klionsky, D. J. & Tang, D. GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy 19, 2621–2638 (2023).

Bersuker, K. et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 575, 688–692 (2019).

Dixon, S. J. & Olzmann, J. A. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 424–442 (2024).

Ma, Q. Transcriptional responses to oxidative stress: pathological and toxicological implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 125, 376–393 (2010).

Li, Y., Yan, J., Zhao, Q., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Y. ATF3 promotes ferroptosis in sorafenib-induced cardiotoxicity by suppressing Slc7a11 expression. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 904314 (2022).

Jiang, H. et al. ATF4 protects against sorafenib-induced cardiotoxicity by suppressing ferroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 153, 113280 (2022).

Yan, C., Lu, D., Hai, T. & Boyd, D. D. Activating transcription factor 3, a stress sensor, activates p53 by blocking its ubiquitination. EMBO J. 24, 2425–2435 (2005).

Cheng, H. et al. Neuroprotection of NRF2 against ferroptosis after traumatic brain injury in mice. Antioxidants 12, 731 (2023).

Cheng, X. et al. Overexpression of Kininogen-1 aggravates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 550, 142–150 (2021).

He, H. et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate pretreatment alleviates doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by upregulating AMPKα2 and activating adaptive autophagy. Redox Biol. 48, 102185 (2021).

Bi, Y. et al. FUNDC1 protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte PANoptosis through stabilizing mtDNA via interaction with TUFM. Cell Death Dis. 13, 1020 (2022).

Reichert, C. O. et al. Ferroptosis mechanisms involved in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8765 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. Ferroptosis is regulated by mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurodegener. Dis. 20, 20–34 (2020).

Yang, W. S. & Stockwell, B. R. Ferroptosis: death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 165–176 (2016).

Ma, X. H. et al. ALOX15-launched PUFA-phospholipids peroxidation increases the susceptibility of ferroptosis in ischemia-induced myocardial damage. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 288 (2022).

Ren, X. et al. Cerebroprotein hydrolysate-I ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting ferroptosis via the p53/SAT1/ALOX15 signalling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 979, 176820 (2024).

Ou, Y., Wang, S. J., Li, D., Chu, B. & Gu, W. Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6806–e6812 (2016).

Shintoku, R. et al. Lipoxygenase-mediated generation of lipid peroxides enhances ferroptosis induced by erastin and RSL3. Cancer Sci. 108, 2187–2194 (2017).

Wei, W. et al. Synergistic antitumor efficacy of gemcitabine and cisplatin to induce ferroptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via Sp1-SAT1-polyamine metabolism pathway. Cell Oncol. 47, 321–341 (2024).

Ludtmann, M. H., Angelova, P. R., Zhang, Y., Abramov, A. Y. & Dinkova-Kostova, A. T. Nrf2 affects the efficiency of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Biochem J. 457, 415–424 (2014).

Herrera, G., Silvero, C. M., Becerra, M. C., Lasaga, M. & Scimonelli, T. Modulatory role of α-MSH in hippocampal-dependent memory impairment, synaptic plasticity changes, oxidative stress, and astrocyte reactivity induced by short-term high-fat diet intake. Neuropharmacology 239, 109688 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Stress dynamically modulates neuronal autophagy to gate depression onset. Nature 641, 427–437 (2025).

Liu, Y., Stockwell, B. R., Jiang, X. & Gu, W. p53-regulated non-apoptotic cell death pathways and their relevance in cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 600–614 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. TMEM164 is a new determinant of autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Autophagy 19, 945–956 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Fujimaki, M. & Rubinsztein, D. C. Autophagy-dependent versus autophagy-independent ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 9, 745–760 (2025).

Du, L. et al. Autophagy suppresses ferroptosis by degrading TFR1 to alleviate cognitive dysfunction in mice with SAE. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 43, 3605–3622 (2023).

Carneiro, B. A. & El-Deiry, W. S. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 395–417 (2020).

Gao, M. et al. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 26, 1021–1032 (2016).

Lee, Y. S., Lee, D. H., Choudry, H. A., Bartlett, D. L. & Lee, Y. J. Ferroptosis-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress: cross-talk between ferroptosis and apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 16, 1073–1076 (2018).

Wright, S. S. et al. Transplantation of gasdermin pores by extracellular vesicles propagates pyroptosis to bystander cells. Cell 188, 280–291.e217 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. The Nrf2-NLRP3-caspase-1 axis mediates the neuroprotective effects of Celastrol in Parkinson’s disease. Redox Biol. 47, 102134 (2021).

Dodson, M., Castro-Portuguez, R. & Zhang, D. D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 23, 101107 (2019).

Meybodi, S. M. et al. Crosstalk between hypoxia-induced pyroptosis and immune escape in cancer: From mechanisms to therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 197, 104340 (2024).

Wu, H., Li, D., Zhang, T. & Zhao, G. Novel mechanisms of perioperative neurocognitive disorders: ferroptosis and pyroptosis. Neurochem Res. 48, 2969–2982 (2023).

Newton, K. et al. Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science 343, 1357–1360 (2014).

Gautam, A. et al. Necroptosis blockade prevents lung injury in severe influenza. Nature 628, 835–843 (2024).

Seo, J., Nam, Y. W., Kim, S., Oh, D. B. & Song, J. Necroptosis molecular mechanisms: recent findings regarding novel necroptosis regulators. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 1007–1017 (2021).

Tuo, Q. Z. et al. Tau-mediated iron export prevents ferroptotic damage after ischemic stroke. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 1520–1530 (2017).

Du, B. et al. Iron promotes both ferroptosis and necroptosis in the early stage of reperfusion in ischemic stroke. Genes Dis. 11, 101262 (2024).

Tsvetkov, P. et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 375, 1254–1261 (2022).

Tang, D., Kroemer, G. & Kang, R. Targeting cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 370–388 (2024).

Cong, Y., Li, N., Zhang, Z., Shang, Y. & Zhao, H. Cuproptosis: molecular mechanisms, cancer prognosis, and therapeutic applications. J. Transl. Med. 23, 104 (2025).

Xue, Q. et al. Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy 19, 1982–1996 (2023).

Hou, K. et al. Molecular mechanism of PANoptosis and programmed cell death in neurological diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 209, 106907 (2025).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L. & Zhou, F. Cuproptosis: a new form of programmed cell death. Cell Mol. Immunol. 19, 867–868 (2022).

Yang, F. et al. Interplay of ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and PANoptosis in cancer treatment-induced cardiotoxicity: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Semin Cancer Biol. 106-107, 106–122 (2024).

Du, M. et al. CircSpna2 attenuates cuproptosis by mediating ubiquitin ligase Keap1 to regulate the Nrf2-Atp7b signalling axis in depression after traumatic brain injury in a mouse model. Clin. Transl. Med. 14, e70100 (2024).

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker predicts dementia onset and progression in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 31, 1416–1417 (2025).

Barthélemy, N. R. et al. Highly accurate blood test for Alzheimer’s disease is similar or superior to clinical cerebrospinal fluid tests. Nat. Med. 30, 1085–1095 (2024).

Qu, L. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of multi-target-directed ligands with BACE-1 inhibitory and Nrf2 agonist activities as potential agents against Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 219, 113441 (2021).

Bahn, G. et al. NRF2/ARE pathway negatively regulates BACE1 expression and ameliorates cognitive deficits in mouse Alzheimer’s models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 12516–12523 (2019).

Singh, A. K. & Pati, U. CHIP stabilizes amyloid precursor protein via proteasomal degradation and p53-mediated trans-repression of β-secretase. Aging Cell 14, 595–604 (2015).

Xiao, Q. et al. Enhancing astrocytic lysosome biogenesis facilitates Aβ clearance and attenuates amyloid plaque pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 34, 9607–9620 (2014).

Bellucci, A. et al. Nuclear factor-κB dysregulation and α-synuclein pathology: critical interplay in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 68 (2020).

Zhou, N. et al. SLC7A11 is an unconventional H+ transporter in lysosomes. Cell 13, 3441–3458 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. The interplay of iron, oxidative stress, and α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease progression. Mol. Med. 31, 154 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. TFEB regulates cellular labile iron and prevents ferroptosis in a TfR1-dependent manner. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 208, 445–457 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Involvement of the STAT3/HIF-1α signaling pathway in α-synuclein-induced ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 752, 151419 (2025).

Kong, L. et al. Granulathiazole A protects 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson’s disease from ferroptosis via activating Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Bioorg. Chem. 147, 107399 (2024).

Zhang, Z. Y. et al. TRIM11 protects against tauopathies and is down-regulated in Alzheimer’s disease. Science 381, eadd6696 (2023).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Role of hypoxia inducible factor-1α in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 80, 949–961 (2021).

Polito, V. A. et al. Selective clearance of aberrant tau proteins and rescue of neurotoxicity by transcription factor EB. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 1142–1160 (2014).

Liu, D. et al. Targeting the HDAC2/HNF-4A/miR-101b/AMPK pathway rescues tauopathy and dendritic abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Ther. 25, 752–764 (2017).

Dasuri, K., Zhang, L. & Keller, J. N. Oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and the balance of protein degradation and protein synthesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 62, 170–185 (2013).

Yao, Z. et al. The involvement of IRP2-induced ferroptosis through the p53-SLC7A11-ALOX12 pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 222, 386–396 (2024).

Xuejia, L. et al. HIF1α/SLC7A11 signaling attenuates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced ferroptosis in animal and cell models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurorestoratol. 13, 100171 (2025).

Ma, J. et al. miR-494-3p promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis by targeting REST to activate the interplay between SP1 and ACSL4 in Parkinson’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 7671324 (2022).

Li, D., Bai, X., Jiang, Y. & Cheng, Y. Butyrate alleviates PTZ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and neuron apoptosis in mice via Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 168, 25–35 (2021).

Zhuang, X. X. et al. Pharmacological enhancement of TFEB-mediated autophagy alleviated neuronal death in oxidative stress-induced Parkinson’s disease models. Cell Death Dis. 11, 128 (2020).

Lewerenz, J. et al. Mutation of ATF4 mediates resistance of neuronal cell lines against oxidative stress by inducing xCT expression. Cell Death Differ. 19, 847–858 (2012).

Zhu, Z. Y. et al. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) rescues cardiac contractile dysfunction in an APP/PS1 murine model of Alzheimer’s disease via inhibition of ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43, 39–49 (2022).

Shao, Y. et al. The inhibition of ORMDL3 prevents Alzheimer’s disease through ferroptosis by PERK/ATF4/HSPA5 pathway. IET Nanobiotechnol. 17, 182–196 (2023).

Meng, X. et al. Lignans from Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill ameliorates cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease and alleviates ferroptosis by activating the Nrf2/FPN1 signaling pathway and regulating iron levels. J. Ethnopharmacol. 341, 119335 (2025).

Jin, W. et al. Neuronal STAT3/HIF-1α/PTRF axis-mediated bioenergetic disturbance exacerbates cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury via PLA2G4A. Theranostics 12, 3196–3216 (2022).

Turovsky, E. A. et al. Role of Satb1 and Satb2 transcription factors in the glutamate receptors expression and Ca2+ signaling in the cortical neurons in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5968 (2021).

Zhan, S. et al. SATB1/SLC7A11/HO-1 axis ameliorates ferroptosis in neuron cells after ischemic stroke by Danhong injection. Mol. Neurobiol. 60, 413–427 (2023).

Thelin, E. P. et al. Protein profiling in serum after traumatic brain injury in rats reveals potential injury markers. Behav. Brain Res. 340, 71–80 (2018).

El-Gazar, A. A., Soubh, A. A., Abdallah, D. M., Ragab, G. M. & El-Abhar, H. S. Elucidating PAR1 as a therapeutic target for delayed traumatic brain injury: Unveiling the PPAR-γ/Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 axis to suppress ferroptosis and alleviate NLRP3 inflammasome activation in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 139, 112774 (2024).

Ravizza, T. et al. mTOR and neuroinflammation in epilepsy: implications for disease progression and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 334–350 (2024).

Macco, R. et al. Astrocytes acquire resistance to iron-dependent oxidative stress upon proinflammatory activation. J. Neuroinflammation 10, 130 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Forsythoside A mitigates Alzheimer’s-like pathology by inhibiting ferroptosis-mediated neuroinflammation via Nrf2/GPX4 axis activation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 2075–2090 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Interleukin-6 deficiency reduces neuroinflammation by inhibiting the STAT3-cGAS-STING pathway in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neuroinflammation 21, 282 (2024).

Jian, M., Kwan, J. S., Bunting, M., Ng, R. C. & Chan, K. H. Adiponectin suppresses amyloid-β oligomer (AβO)-induced inflammatory response of microglia via AdipoR1-AMPK-NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 110 (2019).

Liao, Y. et al. HSF1 inhibits microglia activation to attenuate neuroinflammation via regulating miR-214-3p and NFATc2 in Parkinson’s disease. Folia Neuropathol. 61, 53–67 (2023).

Gao, H., Wang, D., Jiang, S., Mao, J. & Yang, X. NF‑κB is negatively associated with Nurr1 to reduce the inflammatory response in Parkinson's disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 23, 396 (2021).

Mahmut, E. & Ahmet Sevki, T. The antiepileptogenic effect of metformin and possible interaction with neuroinflammation in the pentylenetetrazole-kindling model in rats. Neurochem. J. 17, 260–269 (2023).

Zhu, H. et al. Janus kinase inhibition ameliorates ischemic stroke injury and neuroinflammation through reducing NLRP3 inflammasome activation via JAK2/STAT3 pathway inhibition. Front. Immunol. 12, 714943 (2021).