Abstract

The architectural heritages of the Peking-Mukden Railway has witnessed the industrialization of China. When it no longer serves its original function, finding a new way for reuse becomes a trend. It requires feedback from reused cases to guide decision-making. This article aims to propose an approach to post-occupancy evaluation of architectural heritages in the Peking-Mukden Railway and apply it to real cases for analysis. The evaluation indicator system used here consists of a hierarchical structure, evaluation indicators, and interpretation indicators. Cosine similarity, entropy weight method, and precedence chart method are utilized to determine final weights. The GRA-TOPSIS method is utilized to identify reuse cases that require additional optimization. The conclusions are as follows: 1. The cosine similarity can be introduced to neutralize individual preferences. The entropy weight method can be used to neutralize subjective factors. 2. Based on the analysis of the sensitivity levels, indicators that need to be improved first can be identified. Priority should be given to spatial accessibility and cultural transmission when making adjustments with limited resources. 3. The GRA-TOPSIS evaluation method can be used to rank and find reuse cases that need further optimization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The predecessor of the Peking Railway is the Tangshan-Xugezhuang Railway, which was the earliest railway built independently in China. There are still hundreds of architectural heritage sites belonging to this railway. They were born during a period of dramatic changes in China’s political situation, many of which have historical and artistic values. But only a few well-preserved classic cases have been reused. They belong to the same railway system but have their own characteristics. The linear connection of geographical relationships and the homologous railway culture endow them with commonality, while the construction date and functional use lead to differences in characteristics. The reuse of these architectural heritage sites shows new features that combine the characteristics of the old era with the needs of the new era. They have entered a new life cycle and need a new comprehensive evaluation to measure the effect. This study conducted a post-occupancy evaluation of these samples from the perspective of heritages protection. By analyzing commonalities and differences, it can provide a path reference for the subsequent protection and reuse of other architectural heritages in the railway.

Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is a feedback on the built environment and construction standards [1,2,3]. The POE theory originated in European and American countries in the 1960s, initially proposed by scholars in the field of environmental behavior from research on building environment design [4,5,6]. In Chinese research, the book Interior Environment Design and Psychology introduced POE-related theories and methods earlier [7]. The importance of POE is gradually being recognized in China. Although there are still shortcomings in practical applications, it has become an important research area for architectural design optimization [8,9,10].

POE can be divided into 3 types based on the evaluation content: technical evaluation, functional evaluation, and behavioral evaluation [11]. POE usually selects one or more aspects to establish an indicator system, corresponding to physical environment, functional space, and usage behavior for evaluation. The modes of post-occupancy evaluation can be divided into two types: one is based on objective standards, and the other is based on subjective feelings. The former evaluates design quality based on performance data, while the latter evaluates overall satisfaction based on personal experience. Both can be considered together in the evaluation system [3, 12].

The assessment of the physical environment is mainly based on objective data, such as evaluating public buildings through environmental monitoring or combining actual measurements and questionnaires for comprehensive evaluation [14, 15]. The evaluation of functional and behavioral levels is usually conducted through questionnaires or big data as a medium to collect subjective feelings, based on different themes, and comprehensively evaluate satisfaction [16,17,18]. In existing research on POE of historical buildings after reuse, the evaluation of renovation effectiveness is mainly based on subjective feelings, such as visibility and accessibility, spatial experience and comfort, and appropriateness of regeneration strategies [19, 20]. However, research on specific protection conditions tends to use objective data indicators, such as POE studies of historical architecture museums that integrate collection preservation and visitor perspectives [21]; The post-occupancy evaluation research extended to larger-scale historical districts or industrial heritage parks has similar research frameworks. And the evaluation content will be selected based on a more macro perspective [22,23,24].

Materials and methodology

Heritage list and data collection

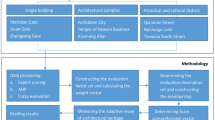

The selection of evaluation objects covers 3 periods in terms of time: the late Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China, and the People’s Republic of China. Taking into account the historical significance, architectural scale, style characteristics, etc., 6 typical case samples that have been updated and revitalized were selected from 30 cases as the research objects for post-occupancy evaluation: China Railway Museum (Zhengyangmen Branch), Tianjin Freight Center Canteen, Jinzhou Railway Culture Palace, Yi County Intangible Cultural Heritage Exhibition Center, Huanggutun Incident Museum, and Office Building of Shenyang Railway Subbureau. The information of the architectural heritages is detailed in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

The Likert scale with 5-level options was used to collect the indicator empowerment opinions and user evaluation opinions through a questionnaire survey. The questionnaires were sent through e-mail to 30 scholars, including 19 researchers majoring in historical buildings, 6 practitioners in the architectural renewal design and research institute, and 5 practitioners in urban and rural planning. The questionnaire of users' evaluation is attached with a detailed text introduction and images of the architectural heritages, which is convenient for tourists, managers, and other individuals without a background in architecture to understand the descriptive language.

Indicator system and analysis methods

Drawing on relevant literature [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34], this study proposes a POE indicator system for railway architectural heritages in the Peking-Mukden Railway, consisting of target layers, first-level, second-level, and interpretation layer (see Table 2). The first-level includes physical space representation and economic and social effects.

The ‘physical space representation’ is a comprehensive evaluation of the performance and quality of the physical entities and the spaces they enclose in the renovation of architectural heritages. The subdivided indicators include accessibility, architectural regeneration adaptability, and external environment quality. The ‘economic and social effects’ is a subdivision of the effects of architectural heritage renovation on the economic and social levels. The subdivided indicators include economic utility, social identity, and cultural transmission.

The analysis methods selected in this paper are applied in the weighting and comprehensive evaluation sections (see Table 3), which encompass 4 individual approaches and 2 composite methods derived from the former. The 4 individual methods interpret data based on a specific feature in respective steps and are integrated through 2 composite methods in the weighting and comprehensive evaluation sections.

Combination of subjective and objective weighting

In the subjective weighting, the emphasis that decision-makers place on indicators directly affects how the weights are allocated. In this study, the expert group is chosen as decision-makers for subjective weighting. Two methods are used in the subjective weighting process: experts’ average priorities and the precedence chart method weighting.

Experts’ average priorities use cosine similarity as a standard to measure the similarity between individual decisions and group decisions. It then adjusts the prior weights of indicators accordingly [35, 36] so that group decisions can represent the common wishes of experts as much as possible and reduce the influence of personal preferences. The precedence chart method uses the results of experts’ average priorities to select the optimal through multi-factor comparison. It quantifies the superiority of indicators in the form of a numerical matrix, thus completing the weight allocation [37, 38].

In objective weighting, the allocation is based on the data characteristics of the evaluation results. It takes into account factors such as dispersion to reduce the proportion of subjective influence in the weighting process. The entropy weighting method is used here to measure the dispersion and uncertainty of the post-occupancy evaluation data and to select indicators that have a greater impact on the comprehensive evaluation. The more information there is, the smaller the entropy value obtained, indicating a greater variation degree in the indicator. Therefore, a larger weight is given to this indicator. Otherwise, a smaller weight is given.

The combined weight is obtained by integrating the subjective and objective weight through calculation. It is calculated based on the principle of minimum discrimination information to make the combined weight, subjective weight, and objective weight as close as possible. The combined weight comprehensively considers the focus of the decision-making group in the professional context, as well as the significant factors reflected by the objective characteristics of the evaluation data [39, 40].

Experts’ average priorities

Experts’ Average Priorities is a pre-procedure for subjective weighting in this study, following the principle of majority rule, aiming to reduce the influence of individual preferences. This step involves calculating the cosine similarity function value \({d}_{e}\) to determine the magnitude of weight adjustment. The larger this value, the closer the individual expert is to the group decision. Assignments that are close to the common will are given greater weight, while those that deviate from the common will are given less weight. After calculating \({d}_{e}\), a ranking value (i.e., 1, 2, 3…k) is assigned to each expert according to this value, and the fine-tuned expert weight assignment is calculated accordingly [41].

Original evaluation matrix of experts

The collected results can be expressed clearly through the matrix. See formula (1) for matrix expression.

\({A}_{a}\) indicates the original evaluation matrix of expert weight for the indicators in the system;

\({a}_{kn}\) refers to the value of the importance evaluation of the \(n\) th indicator by the \(k\) th expert.

Cosine similarity function value

The cosine similarity function value \({d}_{e}\) is the basis for judging the difference between individuals and groups. Its principle is to judge the similarity through the angle between two vectors. The smaller the difference is, the larger the \({d}_{e}\) is. It is necessary to make subsequent adjustments to the indicators according to the calculation results of \({d}_{e}\). See formula (2) for the calculation process of \({d}_{e}\) value.

\({d}_{e}\) is the cosine similarity function value;

\({a}_{ej}\) indicates the individual expert weight for the \(j\) th indicator;

\({\overline{a}}_{j}\) refers to the average weight of the experts' group before the adjustment of the \(j\) th indicator;

\(\sum {A}_{:,j}\) means summing the \(j\) th column of matrix A.

Group decision weight fine-tuning

In the process of transforming cosine similarity \({d}_{e}\) into the corresponding fine-tuning weight \({w}_{e}\), the value \({\mu }_{e}\) needs to be sorted from small to large according to the \({d}_{e}\) value as the calculation basis. The minimum \({\mu }_{e}\) value corresponding to the minimum \({d}_{e}\) value is 1; The maximum \({\mu }_{e}\) value corresponding to the maximum \({d}_{e}\) value is k (k is the total number of experts participating in the evaluation). The \({d}_{e}\) value is the largest, and the greater the \({\mu }_{e}\) value. The greater the weight value of the corresponding expert's score will be obtained in this step. See formula (3) for the conversion relationship between sorting value \({\mu }_{e}\) and fine-tuning weight value \({w}_{e}\).

\({\mu }_{e}\) is the ranking value obtained for the \(e\) th expert;

\({w}_{e}\) represents the fine-tuning weight value of the \(e\) th expert.

Subjective weighting based on precedence chart method

Precedence chart is a method for calculating indicator weights [42]. This method is based on the overall winning situation between the indicators to sort and assign values. And it is presented as a judgment matrix. In the judgment matrix, 0, 0.5, and 1, respectively, mean relatively unimportant, equally important, and relatively important. These three values are the superior ordinal numbers of the comparison results. The sum of the superior ordinal numbers of all comparison results of an indicator is the basis for weight distribution. The more times the indicator wins in the importance comparison, the larger total priority number is, and a higher weight value should be given [43, 44].

Judgment matrix

The judgment matrix is the basis for multi-factor comparison and selection by the precedence chart method. See formula (4) for the matrix expression. 0, 0.5, 1 in matrix C is used to quantify the degree of superiority.

Precedence number

The precedence number is the numerical presentation of the total superior degree of the indicator and is the direct basis for weight distribution. It is obtained by summing each row of the judgment matrix. See formula (5) for the calculation.

\({PN}_{xj}\) is the precedence number of the \(j\) th indicator \({X}_{j}\);

\(\sum {C}_{j,:}\) means summing the \(j\) th row of matrix \(C\).

Subjective weight calculation

The weight is given by calculating the proportion of the total priority number of the indicator \({PN}_{xj}\). See formula (6) for the conversion relationship between the total priority number \({PN}_{xj}\) and the subjective weight value \({w}_{zj}\).

\({w}_{zj}\) represents the subjective weight value of the \(j\) th indicator \({X}_{j}\).

Objective weighting based on the entropy weight method

The Entropy Weight Method (EWM) is an objective weighting method. It judges based on the objective information reflected by the evaluation results [45]. A smaller entropy value indicates greater data dispersion, suggesting that the difference in scores for different architectural heritages in that indicator is greater [46]. Shortly, indicators with a smaller entropy value are significant factors affecting the evaluation results and should be given a higher weight value. Conversely, a lower weight value should be assigned.

Users` original evaluation matrix and data processing

The score data were presented concisely by matrix, and the original data were standardized and normalized. See formula (7) for matrix expression and data processing.

\({d}_{mn}\) represents the original evaluation value of the \(n\) th indicator of the \(m\) th architectural heritage;

\({f}_{ij}\) represents the indicator attribute after standardization.

Entropy method weight calculation

According to the data in matrix D, the entropy value \({e}_{j}\) can be calculated and converted into the objective weight \({w}_{kj}\). See formula (8) for the calculation process.

\({p}_{ij}\) represents the specific gravity of characteristic;

\({e}_{j}\) represents entropy;

\({g}_{j}\) represents the difference coefficient;

\({w}_{kj}\) represents the entropy method weight of the indicator.

Combination weight calculation

The combined weight is calculated using the Minimum Discrimination Information Principle [47]. This method involves seeking a solution that minimizes this difference under certain conditions [48]. When the sum of the distance among \({\omega }_{j}\), \({w}_{zj}\), \({w}_{kj}\) (combined weight, subjective weight, objective weight) is minimal, it indicates that the difference corresponding to this weight value is minimal, which comprehensively considers both subjective and objective weight factors. The calculation method of the combined weight value \({\omega }_{j}\) is shown in formula (9).

\({\omega }_{j}\) is the combined weight of the \(j\) th indicator;

\({w}_{zj}\) is the subjective weight;

\({w}_{kj}\) is the objective weight.

GRA-TOPSIS comprehensive evaluation method

The comprehensive evaluation process adopts a combination of Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [49, 50]. The GRA method ranks different elements based on their importance, which considers the geometric similarity of data but ignores the numerical proximity. The TOPSIS method ranks evaluation objects based on their distance from the ideal solution [51, 52], which reflects the positional relationship between data curves but does not reflect the trend changes of data. This study integrates and complements the 2 methods of TOPSIS and GRA, scoring and ranking by simultaneously measuring both geometric similarity and numerical difference between the architectural heritages and the ideal solution. According to the calculated relative closeness \({\eta }_{i}\), the final evaluation gradation of each architectural heritage is obtained, as shown in Table 4.

The relative closeness \({\upeta }_{i}\) is obtained by combining the evaluation results of TOPSIS and GRA methods. When evaluating based on TOPSIS, the closeness of each evaluation object to the ideal solution is obtained by calculating the Euclidean distance, and the scoring and ranking are carried out accordingly. When evaluating based on GRA, the importance of different elements is ranked according to the geometric similarity of data sequences by calculating the grey relational degree. The relative closeness \({\upeta }_{i}\) obtains the evaluation result based on the gap between the evaluation object and the ideal solution, that is, the relative ideal degree of the case. Based on this, it is possible to compare the differences in user satisfaction under the same indicator system and analyze the causes of this result in combination with the actual situation. The GRA-TOPSIS comprehensive evaluation method mainly includes the following research steps:

Weighted evaluation matrix

The evaluation data and weight values are input into the weighted evaluation matrix. See formula (10) for matrix expression and data processing.

\({d}_{ij}\) refers to the element in \(i\) th row and \(j\) th column of the original evaluation matrix \(D\);

\({\omega }_{n}\) represents the combined weight of the \(j\) th indicator.

Application of theTOPSIS method for evaluation

The distance between the architectural heritage and the ideal solution is obtained by calculating the Euclidean distance \({d}_{i}^{\pm }\) as the evaluation result of the TOPSIS method. The selection of the ideal scheme of this method and the calculation of Euclidean distance are shown in the formula (11).

\({X}^{+}\),\({X}^{-}\) indicates positive and negative ideal scheme; \({x}_{j}^{+}\), \({x}_{j}^{-}\) denote positive and negative ideal solutions; \({d}_{i}^{+}\),\({d}_{i}^{-}\) denote the Euclidean distance of positive and negative ideal solutions.

Application of the GRA method for evaluation

The geometric similarity of the evaluation data is obtained by calculating the grey correlation degree \({l}_{i}^{\pm }\) as the evaluation result of the application of the GRA Method. See formula (12) for the calculation method.

\({\gamma }_{ij}^{+}\), \({\gamma }_{ij}^{-}\) represents the weighted grey correlation degree of the \(j\) th indicator between the \(i\) th architectural heritage and the positive ideal solution; \(i\) th architectural heritage and negative ideal solution.

\({l}_{i}^{+}\), \({l}_{i}^{-}\) represents the weighted grey correlation degree between the comprehensive values of all indicators of the \(i\) th architectural heritage and the positive ideal solution; \(i\) th architectural heritage and negative ideal solution.

\(\rho \) is the identification coefficient, \(\rho \in \) [0,1], take \(\rho \)=0.5

Relative closeness

According to the Euclidean distance \({d}_{i}^{\pm }\) calculated by the TOPSIS method and the grey correlation degree \({l}_{i}^{\pm }\) calculated by the GRA method, the relative closeness \({\upeta }_{i}\) is obtained. This value reflects the sum of the relative ideal degree of the case and can be used as the basis for sorting. See formula (13) for the calculation method.

\({D}_{i}^{\pm }\),\({L}_{i}^{\pm }\), represent Euclidean distance and grey correlation degree;

\({\varphi }_{i}^{\pm }\) represents the combined value of both methods;

\(\beta \) indicates the preference of decision-makers,

\({\beta }_{1}{+\beta }_{2}\)=1, \({\beta }_{1}{, \beta }_{2}\) \(\in \) [0,1];

\({\upeta }_{i}\) represents relative closeness.

Results

Combination weight results

Subjective weight

Both 2 methods are combined in the calculation of subjective weights, which is completed in 3 steps: Firstly, according to the aforementioned formulas (1), (2), and (3), the fine-tuned weight values \({w}_{e}\) of each expert are calculated. The results are shown in Table 5. Secondly, the fine-tuned weights are obtained based on \({w}_{e}\). The process is shown in formula (14), and the results are shown in Table 6. Thirdly, according to formulas (4), (5), and (6), the subjective weighting is completed using the precedence chart method, and the results are shown in Table 7.

The matrix \({A}_{poe}\) represents the weights from each expert after giving the fine-tuning weight \({w}_{e}\). Each element is composed of ‘expert score × fine-tuning weight’. After the average sum of each column in the matrix \({A}_{poe}\), the experts’ average priorities weight can be obtained.

The subjective weights of the indicators are as follows:

A = [5.350, 6.722, 4.801, 0.686, 4.527],

B = [3.155, 5.624, 7.270, 1.783, 3.429],

C = [3.978, 6.447, 3.704, 0.412, 0.137, 1.235, 1.783, 2.606],

D = [4.252, 2.332, 5.075],

E = [1.509, 6.996, 0.960, 2.881],

F = [5.898, 6.447].

Objective weight

The entropy weight method is used to calculate the objective weights in 2 steps: Firstly, calculate the specific gravity of characteristic \({p}_{ij}\) and entropy value \({e}_{j}\) according to the formulas (7) and (8). Secondly, convert the entropy value \({e}_{j}\) into the difference coefficient \({g}_{j}\) and complete the objective weight allocation. The results of the entropy weight method are shown in Table 8.

The objective weights of the indicator are as follows:

A = [5.147, 6.187, 5.045, 3.120, 6.976],

B = [2.945, 2.730, 2.999, 3.803, 3.173],

C = [4.450, 3.505, 2.710, 5.657, 2.634, 3.799, 3.162, 2.426],

D = [3.285, 3.269, 2.288],

E = [2.822, 3.588, 2.998, 3.014],

F = [4.107, 4.169].

Combination

In combined weighting, the Minimum Discrimination Information Principle is used for integration. The steps involve organizing the subjective weight value \({w}_{zj}\) and objective weight value \({w}_{kj}\) of the indicators and inputting them into the formula (9) to obtain the corresponding combined weight \({\omega }_{j}\). The final results of the combined weights of evaluation indicators are as follows:

A = [5.566, 6.841, 5.221, 1.552, 5.961],

B = [3.233, 4.157, 4.945, 2.762, 3.499],

C = [4.463, 5.043, 3.361, 1.618, 0.638, 2.297, 2.519, 2.668],

D = [3.965, 2.929, 3.615],

E = [2.189, 5.315, 1.800, 3.126],

F = [5.221, 5.499].

Evaluation results

The comprehensive evaluation combines 2 evaluation methods and is carried out in 4 steps: Firstly, the evaluation data and corresponding combination weights are collated. And a weighted evaluation matrix is constructed according to the formula (10). Secondly, the Euclidean distance \({d}_{i}^{\pm }\) is obtained using the TOPSIS method according to formula (11). Thirdly, the grey relational degree \({l}_{i}^{\pm }\) is calculated using the GRA method according to formula (12). Fourthly, the relative closeness \({\eta }_{i}\) is calculated according to formula (13). The classification is carried out according to the grade division table (Table 4). The final comprehensive evaluation results are shown in Table 9 and Fig. 2.

Discussion

Analysis of differences in indicator weight

The weight reflects the sensitivity of the evaluator to a certain evaluation index. Sensitivity is used to express the degree to which a thing can be perceived and can be regarded as a psychological weight [53, 54]. Evaluators pay more attention to elements with high psychological weight and are less likely to give moderate results. So sensitive items can be discovered from polarized evaluations [53, 55]. The weighting process actually combines perceptual evaluations from 2 perspectives and highlights sensitive indicators through peak values and dispersion. The weight value in subjective weighting directly reflects the psychological weight of the expert group; while the weight value in objective weighting indirectly reflects the psychological weight of the general users.

From the perspective of the experts` group, the sensitivity indicators show more attention on long-term value, with a greater emphasis on core practicality, inheritance, and influence. Indicators such as structural reliability, coordination, public recognition, and cultural continuity receive more attention, indicating that the exploration of historical and cultural values of heritages under the premise of safety is the focus from this perspective. Secondary design elements such as parking spaces, green landscapes, and architectural details have a lower priority. From the perspective of general users, the sensitivity indicators focus more on immediate visual experiences, with a greater emphasis on convenience and ambiance. Therefore, the setting of entrances and exits, road traffic within the park, and green landscapes become significant factors, indicating that users pay more attention to convenience and accessibility when evaluating railway architectural heritages [56].

By integrating the perspectives of both expert group and user evaluation groups, and analyzing the differences based on the weighting results shown in Fig. 3, sensitive indicators are identified (Table 10). The ideal average weight value of 27 indicators is used as an auxiliary judgment threshold. When both subjective and objective weights are higher than this value, it shows that the indicator is sensitive from the perspective of both evaluation groups, classified as ‘Sensitivity level 1’ (Fig. 3-①). When the subjective weight is higher than this value and the objective weight is lower than this value, it shows that the indicator is sensitive from the perspective of the experts` group, classified as ‘Sensitivity level 2’ (Fig. 3-②). When the objective weight is higher than this value and the subjective weight is lower than this value, it shows that the indicator is sensitive from the perspective of general users, classified as ‘Sensitivity level 3’ (Fig. 3-③). When both subjective and objective weights are lower than this value, it shows that the indicator is not sensitive from the perspective of both groups, classified as ‘Non sensitive’ (Fig. 3-④) [54]. After comparative analysis, the Sensitivity level 1 indicators in the explanatory layer are A1, A2, A3, A5, F1, and F2. When optimizing based on POE results under limited resources, priority should be given to spatial accessibility in physical space representation and cultural transmission in economic and social effects.

Analysis of satisfaction evaluation results

When the satisfaction level is rated as L1 or L2, it indicates that the current quality of use is at a relatively low level among all cases participating in the evaluation. This can be combined with sensitivity indicators to determine items that need to be optimized. Among the satisfaction evaluation results of the 6 architectural heritages (See Table 9), half are rated as L3, and 2 with better performance are rated as L4, indicating that most of the evaluation objects have met the expectations of users in the reuse under limited conditions. The satisfaction level of Case No. 2, Tianjin Freight Center Canteen, is relatively low, and its performance in items A, C, E, and F is inferior, which is related to the limitations of its use functions. The use functions of the exhibition and office may have more room for improvement in terms of user satisfaction.

Based on the sensitivity indicators in the previous analysis, comparisons, and optimization adjustments can be made, as shown in Table 11. The lowest score is for Case No. 5, Tianjin Freight Center Canteen and the highest score is for Case No. 5, Huanggutun Incident Museum. Through comparative observation, the entrance environment of Case No. 2 is cramped, with messy arrangements of pipes and air conditioning on the walls, and the overall recognition is average. The entrance facade of Case No. 2 is changed to transparent glass that contrasts with the original brick wall, giving the entrance a strong sense of transparency and high recognition. Through comparative reference, it is clear that one of the optimization directions for Case No. 2 in A5 is to create a bright and spacious entrance space through orderly planning or to remove wall clutter to reveal the original facade features.

The values of the secondary indicators for L2 and L3 level evaluation objects are relatively close, but there are differences in the final result calculation. This indicates that the method can be evaluated by integrating numerical differences and distribution differences. Although the reference object is the ideal solution composed of optimal items, under the influence of variable differences in individual buildings, the optimality of the ideal solution may not necessarily be the optimality of the evaluation object, but it still has practical significance.

Conclusions

In this study, an approach is proposed for the post-occupancy evaluation of the Peking-Mukden Railway architectural heritages. The analysis examines 6 different reuse cases. The research process involves creating a value evaluation indicator system. Both expert opinions and users` evaluation data are used in indicator weighting to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the reuse cases. Cosine similarity, entropy weight method, precedence chart method, and GRA-TOPSIS method are utilized to ensure the evaluation process is scientifically sound. The conclusions are as follows:

Firstly, the weighting process needs to be more objective to enhance credibility. Objective information can be introduced twice in the empowerment process: introducing cosine similarity in the experts’ average priorities to reduce the influence of personal preferences and introducing the entropy method to neutralize subjective factors.

Secondly, based on the analysis of the sensitivity levels, indicators that need to be improved first can be identified. Priority should be given to spatial accessibility and cultural transmission when making optimization design with limited resources.

Thirdly, the GRA-TOPSIS evaluation method can be used to quantify the quality of heritage reuse projects, identify projects that need to be optimized, and make adjustments accordingly. The GRA-TOPSIS evaluation method used in the study is characterized by a comprehensive assessment of all participating evaluation objects, taking the ideal solution composed of the optimal items of each index in the total sample as the reference quantity, and being able to evaluate and rank based on the numerical and distribution differences of the overall score. A lower satisfaction level indicates poorer use quality, which needs to be adjusted and optimized based on the actual situation.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study may be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- POE:

-

Post occupancy evaluation

References

Liang S, Zhang W. A review of the progress of post-occupancy evaluation research based on the ‘pre-planning-post-evaluation’ closed loop. Time Archit. 2019;4:52–5.

Zhuang W. ‘Pre-planning to post-evaluation’: a feedback mechanism for the closed loop of architectural process. Des Community. 2017;5:125–9.

Science N, Committee TTR. Architectural terms. Beijing: Science Press; 2014.

Zhuang W, Dang Y. Post-occupancy evaluation: a standard for reasonable design. Des Community. 2017;1:132–5.

Zhuang W, Han M. Overview of basic methods and frontier technologies for post-occupancy evaluation of buildings. Time Archit. 2019;4:46–51.

Chen X. The importance and urgency of post-occupancy evaluation (POE) for architects. South Archit. 2015;6:61–5.

Chang H. Environmental psychology and interior design. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 2000.

Zhuang W, Liang S, Wang T. Post-evaluation in China. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 2017.

Zhuang W, Zhang W, Liang S. Architectural planning and post-evaluation. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 2018.

Li P, Froese TM, Brager G. Post-occupancy evaluation: state-of-the-art analysis and state-of-the-practice review. Build Environ. 2018;133:187–202.

Wu S. An important research direction in architecture: post-occupancy evaluation. South Archit. 2009;1:4–7.

Vasquez-Hernandez A, Alvarez MFR. Evaluation of buildings in real conditions of use: Current situation. J Build Eng. 2017;12:26–36.

Jiu M, Song L. Research ideas on post-occupancy evaluation method for green buildings. Build Sci. 2015;31(12):113–21.

Anna LP, Veronica LC, Cristina P, Franco C. Coupling artworks preservation constraints with visitors’ environmental satisfaction: results from an indoor microclimate assessment procedure in a historical museum building in central Italy. Indoor Built Environ. 2018;27(6):846–69.

Zhu X. Post-occupancy evaluation and sensitivity analysis of evaluation indicators for the quality of living space environment in typical affordable housing in Guangzhou. J Hum Settl West China. 2017;32(03):23–9.

Xu L, Yang G. Evaluation of residential environment in Shanghai. J Tongji Univ (Nat Sci). 1996;05:546–51.

Suyeon B, Abimbola OA, Caren SM. Impact of occupants’ demographics on indoor environmental quality satisfaction in the workplace. Build Res Inf. 2020;48(3):301–15.

Xu L. Post-occupancy evaluation of sunken plaza. J Tongji Univ (Nat Sci). 2003;12:1405–9.

Hashim AE, Aksah H, Said SY. Functional assessment through post occupancy review on refurbished historical public building in Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2012;68:330–40.

Mundo-Hernández J, Valerdi-Nochebuena MC, Sosa-Oliver J. Post-occupancy evaluation of a restored industrial building: a contemporary art and design gallery in Mexico. Front Archit Res. 2015;4:330–40.

Martínez Molina A, Boarin P, Tort-Ausina I, Vivancos JL. Assessing visitors’ thermal comfort in historic museum buildings: results from a post-occupancy evaluation on a case study. Build Environ. 2018;132:291–302.

Wang Z, Zhuang W. Post-evaluation study on the use of SD method for perceptual evaluation driven by review data—taking urban and rural historical districts as an example. New Archit. 2019;04:38–42.

Zhu X. Post-occupancy evaluation of public street corner space in old urban communities - taking Xiguan in Guangzhou as an example. Huazhong Archit. 2011;29(10):78–81.

Liu X, Shao Y, Wang Y. Research on the optimization strategy of industrial heritage renovation for creative industries based on POE. Mod Urban Res. 2017;05:58–66.

Wang H. Research on the protection history of american architectural heritage: an analysis of four thematic events and their background. Nanjing: Southeast University Press; 2009.

Freeman MA III. The measurement of environmental and resource values (Zeng X. Trans.). Beijing: People’s University of China Academic Press; 2002.

Prukin. Architecture and historical environment (Han L. Trans.). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2011.

Zhang J. Research and evaluation on values of architectural heritage of chinese eastern railway. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 2017.

Tang Q, Shen Z. Research on Yunnan-Burma railway engineering and architectural heritage value. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press; 2018.

Chen J, Sun S, Lin K, Lin J. Post-occupancy evaluation of public spaces in traditional villages and towns from the perspective of space syntax. South Archit. 2022;4:99–106.

Si G, Zhuang W, Liang S. Framework and logic of post- occupancy evaluation of neighborhood space. Archit J. 2024;02:36–42.

Jia Y. Embodiment and Application of Multi- subject Needs in the Evaluation of Public Building External Spaces. New Archit. 2023;3:27–32.

Hay R, Samuel F, Waston KJ, Bradbury S. Post-occupancy evaluation in architecture: experiences and perspectives from UK practice. Build Res Inf. 2018;46(6):698–710.

Liu F, Zhao Q, Yang Y. An approach to assess the value of industrial heritage based on Dempster-Shafer theory. J Cult Herit. 2018;32:210–20.

Forman E, Peniwati K. Aggregating individual judgments and priorities with the analytic hierarchy process. Eur J Oper Res. 1998;108(1):165–9.

Herrera F, Herrera-Viedma A, Chiclana F. Multiperson decision-making based on multiplicative preference relations. Eur J Oper Res. 2001;192(2):372–85.

Huang W. Application of the precedence chart method in evaluation. J Technol Econom. 1997;3:63–4+40.

Li H, Zong X, Wang J, Wang D, Liang N. Construction of evaluation index system for traditional Chinese medicine group standards based on improved Delphi method and precedence diagram method. Chinese J Basic Med. 2023;29(05):775–80.

Xue X, Wang X, Zhang Q. Combined weight and variable fuzzy coupling model for wear risk assessment of filling pipeline. J Cent South Univ. 2016;47(11):3752–8.

Zuo Q, Zhang Z, Wu B. Evaluation of water resources carrying capacity in nine provinces of the yellow river basin based on the combined weight TOPSIS model. Water Resour Prot. 2020;36(02):1–7.

Yang Y, Yu B, Tai H, Shen L, Wang S. A methodology for weighting indicators of value assessment of historic building using AHP with experts’ priorities. J Asian Architect Build Eng. 2022;21(5):1814–29.

Moody PE. Decision making: proven methods for better decisions. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1983.

Jin X, Li Y. Comparative study and application of the analytic hierarchy process and the analytic hierarchy process in determining weights. Chinese J Health Stat. 2001;02:55–6.

Yang L, Song Y, Hu Z. Recognition of typical driving stressors and driver stress level in a Chinese sample. J Transp Saf Secur. 2023;15(8):774–94.

Li G, Yuan H, Shan Y, Lin G, Xie G, Giordano A. Architectural cultural heritage conservation: fire risk assessment of ancient vernacular residences based on FAHP and EWM. Appl Sci. 2023;13:12368.

Chen H, An Y. Green residential building design scheme optimization based on the orthogonal experiment EWM-TOPSIS. Build. 2024;14:452.

Soofi ES, Retzer JJ. Adjustment of importance weights in multiattribute value models by minimum discrimination information. Eur J Oper Res. 1992;60(1):99–108.

Zeng Y, Qiang Y, Zhang N, Yang X, Zhao Z, Wang X. An influencing factors analysis of road traffic accidents based on the analytic hierarchy process and the minimum discrimination information principle. Sustain. 2024;16(16):6767.

Chen C. A new multi-criteria assessment model combining gra techniques with intuitionistic fuzzy entropy-based topsis method for sustainable building materials supplier selection. Sustain. 2019;11(8):2265.

Zhang J, Huang D, You Q. Evaluation of emergency evacuation capacity of urban metro stations based on combined weights and TOPSIS-GRA method in intuitive fuzzy environment. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023;95: 103864.

Dong H, Yang K, Bai G. Evaluation of TPGU using entropy-improved TOPSIS-GRA method in China. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1): e0260974. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260974.

Ji J, Wang D. Evaluation analysis and strategy selection in urban flood resilience based on EWM-TOPSIS method and graph model. J Clean Product. 2023;421(1): 138955.

Si G, Zhuang W. The dilemma and breakthrough countermeasures of china’s open blocks: based on residents’ perception sensitivity assessment. J Urban Sci. 2024;1:8–15.

Wang S. Architectural scheme planning and architectural design evaluation based on fuzzy bi-directional hierarchical algorithm. PhD degree. Beijing: Tsinghua University; 2015.

Li Z, Kang J. Sensitivity analysis of changes in human physiological indicators observed in soundscapes. Landsc urban plan. 2019;190: 103593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103593.

Zheng M, Chen M, Li P. Post-occupancy evaluation of information signs and pre-boarding behavior in a historic railroad station. J Asian Architect Build Eng. 2010;9(1):177–84.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 52078107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.; Methodology, Z.L.; Formal analysis, Z.L.; Investigation, W.Q.; Resources, F.L. and W.Q.; Writing—original draft, Z.L. and W.Q.; Writing—review & editing, F.L. and Z.L.; Visualization, Z.L.; Supervision, F.L.; Project administration, F.L.; Funding acquisition, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Lu, Z. & Qiang, W. An innovative approach to post-occupancy evaluation of architectural heritages in the Peking-Mukden railway. Herit Sci 12, 383 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01498-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01498-6