Abstract

Ecological vulnerability is crucial in assessing the ecosystems of Karst World Heritage Sites(WHSs), providing vital insights for ecological evaluation, protection, and resilience enhancement. This study develops an indicator system based on the Sensitivity-Recovery-Pressure (SRP) conceptual model, selecting 11 indicators across four dimensions: climate, topography, vegetation, and human disturbance. Using Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang Karst WHSs as study areas, we analyzed data from 2014, 2018, and 2022. By integrating the entropy weight method with the Geodetector, we investigated the spatiotemporal changes in ecological vulnerability and identified the primary driving factors. The findings reveal: (1) Temporally, the comprehensive ecological vulnerability index of Shibing WHS initially decreased and then increased from 2014 to 2022, but overall trending positively. In contrast, the vulnerability index of Libo-Huanjiang WHS showed a slight increase. (2) Spatially, core areas of the WHSs exhibited relatively low ecological vulnerability, while buffer zones and tourist concentration areas showed higher vulnerability. (3) Regarding driving factors, all indicators significantly influenced ecological vulnerability, with multi-factor interactions offering stronger explanatory power than single factors. These results provide essential scientific evidence for assessing the ecological environment of Karst WHSs, promoting sustainable tourism development, and enhancing environmental change resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the inception of the International Biological Program (IBP) in the 1960s, ecological vulnerability has emerged as a pivotal topic in ecological environmental research and a current focus in ecological protection and sustainable development studies. Ecological vulnerability denotes the sensitivity and response capacity of ecosystems to natural and human stressors over time and space, encompassing structural and functional changes in ecosystems facing challenges like climate change, pollution, and overexploitation. It is fundamental for environmental protection and sustainable development1. To date, significant research outcomes have been achieved. Evaluation indicators are mainly categorized into single-type2, composite3, and simulation prediction systems4, tailored to regional ecosystem conditions. Various models have been established for regional ecological vulnerability evaluation, including qualitative-quantitative, temporal-spatial, and static-dynamic studies5, with prominent models such as the Sensitivity-Recovery-Pressure (SRP) model6, the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model7, the Vulnerability-Sensitivity-Adaptation (VSD) model8, and ecosystem structure-function-habitat indicators9. Evaluation methods vary with indicator systems and data characteristics, including the entropy weight method10, AHP-fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method11, landscape ecology method12, principal component analysis13, and comprehensive index method14. Research areas primarily cover ecologically sensitive regions like the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau15, the Loess Plateau16, and the southwestern Karst region, along with specific natural geographical units such as watersheds17, forests18, and grasslands19. Ecological vulnerability assessment is a critical and foundational component in ecological protection and climate change research, and has become a core element in promoting sustainable development20,21. However, studies focusing on the ecological vulnerability of Karst World Heritage Sites (WHSs) remain scarce.

Globally, Karst ecosystems span approximately 22 million km², accounting for about 15% of the global land area. The southwestern part of China, centered on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, contains the world’s most concentrated and continuous carbonate rock formations, covering about 550,000 km²22. Due to unique geological structures, climatic conditions, and human activities, the southwestern Karst region exhibits pronounced ecological vulnerability23. The ancient and hard characteristics of carbonate rocks, coupled with synchronous rain and heat conditions under the monsoon climate and intense human disturbances, make the ecosystem extremely sensitive to changes24,25. The karst ecosystem features two extreme landscapes: well-preserved original karst ecosystems and degraded secondary karst ecosystems due to human disturbance26,27. Karst WHSs integrate these two ecosystems. The “South China Karst” is a World Natural Heritage project submitted in phases by the Chinese government to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee. It is one of the most well-developed regions globally for tropical-subtropical, humid to semi-humid plains, hills, mountains, and plateau karst systems. It reflects the geological development history of southern China, its unique natural geography, landscape types, ecosystems, biodiversity, natural beauty, and evolutionary processes, holding significant global value and importance28. These sites are not only outstanding witnesses to Earth’s evolutionary history, recording the development of life and significant geomorphological processes, but also showcase unique landforms and natural geographic features, holding irreplaceable value29. Generally, these WHSs are considered to have dense vegetation, effective protection, and a favorable natural ecological environment. However, they are characterized by multiple vulnerabilities, and from a natural perspective, global climate change poses unprecedented challenges and degradation risks to WHSs30. Coupled with the inherent vulnerability of karst areas—characterized by thin soil layers, complex aboveground and underground structures, and high susceptibility to natural disasters like floods—the instability of the ecological environment is high31. From humanities perspective, the Karst WHSs are known for its rich biodiversity, unique geological structures, and diverse geomorphological landscapes. With the branding effect of the WHS, recognition has been enhanced and a large number of tourists have been attracted to the site, leading to an increase in tourism facilities and programs32. However, the intensity of human activities has increased the pressure on the ecological environment of the WHSs33. Overall, the ecological vulnerability of the Karst WHS refers to the high sensitivity and instability displayed by their ecosystems when faced with natural pressures like disasters and climate change, as well as human pressures such as over-tourism. Due to thin soil layers and complex structures, these areas are highly susceptible to damage, posing severe challenges to ecological security. Therefore, in-depth research on the vulnerability distribution characteristics, spatiotemporal evolution, and driving factors of Karst WHSs is of vital importance for formulating effective ecological protection measures and promoting sustainable development. This not only helps maintain the integrity of these valuable resources but also holds significant value for global biodiversity conservation and geological scientific research.

Current research on WHSs mainly includes geomorphological characteristics and development evolution, aesthetic value, monitoring, protection, and management, biodiversity and distribution patterns, and ecosystem structure and function34,35,36,37. Related studies on the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs are often limited to time series. However, integrating the concepts of ecological geography and utilizing Geographic information systems (GIS) for spatial analysis and driving mechanism investigation of ecological vulnerability is still lacking. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the spatiotemporal distribution patterns and causes of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs. Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang Karst WHSs were selected as case studies. Based on the SRP model, focusing on climate, topography, vegetation, and human disturbance, the entropy weight method was used to determine indicator weights and further spatial map overlay analysis of GIS and Geodetector were employed to reveal distribution characteristics, spatiotemporal evolution, and driving factors. This study constructs a universally applicable indicator system for assessing the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs, providing a foundation for evaluating the ecological vulnerability of different Karst WHSs, aiming to offer effective references for better protection and management of WHSs.

Study area and data sources

Study area

A heritage site, often referred to as the core area, is an area with outstanding natural or cultural value that requires strict protection. Human activities are prohibited or restricted to maintain its original state and ecological integrity. The buffer zone surrounds the core area, allowing moderate development and low-intensity use. It serves as additional protection for the core area, preventing external disturbances and ensuring the long-term stability of the core area. The study areas in this article all include buffer zones38.

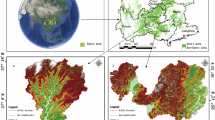

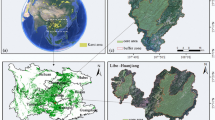

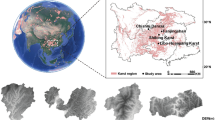

Shibing Karst is located in Shibing County, Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province (center coordinates: 108°05′40″E, 27°10′16″N). It overlaps with the boundaries of the National Scenic Area of Wuyang River, including the Shanmu River and Yuntai Mountain Scenic Area, and the Shanmu River Watershed. The WHS covers 102.8 km², with a buffer zone of 180.15 km², totaling 282.95 km². The annual average temperature is 16 °C, and annual average precipitation of 1220 mm. The elevation ranges from 526 to 1576 m, with average elevation of 912 m (see Fig. 1). This region is situated in the mid-subtropical karst canyon area, generally characterized by higher elevations in the north and lower in the south. The landscape predominantly features peak-cluster canyons, interspersed with peak-cluster depressions, peak-cluster valleys, peak-forest valleys, and peak-forest depressions, making it a typical representative of tropical and subtropical dolomite karst landforms worldwide39.

Libo-Huanjiang Karst, a typical cone karst, is located at the junction of Libo County, Qiannan Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, Guizhou Province, and Huanjiang Maonan Autonomous County, Guangxi Province (center coordinates: 107°58′30″E, 25°13′15″N and 107°59′40″E, 25°10′01″N). It includes the Maolan National Nature Reserve, the Small and Large Seven-Hole Scenic Areas of the Zhangjiang National Scenic Area, and the Mulun National Nature Reserve in Guangxi. The total area of the Libo-Huanjiang WHS is 845.75 km², with 366.47 km² as the core area of WHS and 479.28 km² as the buffer zone. The annual average precipitation is 1752 mm, and average annual temperature of 15 °C, and average elevation of 758 m. Developed in the mid-subtropical plateau cone karst, this unique geographical area preserves the largest remnant evergreen and deciduous broad-leaved mixed forest ecosystem at the same latitude on Earth. It showcases significant ongoing karst biological and ecological evolutionary processes and houses numerous rare wildlife species, making it a key area for global biodiversity and habitat protection40.

Data sources and processing

The data for this study include meteorological data, remote sensing data, land use cover data, and socio-economic data for Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang WHSs from 2014, 2018, and 2022.

Meteorological data include temperature, precipitation, and dryness, sourced from the National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn), with a resolution of 1 km.

Remote sensing data come from the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn/), and slope, aspect, and topographic relief are calculated using ArcGIS Digital Elevation Model (DEM) tools with a resolution of 30 m.

Gross domestic product (GDP) spatial distribution raster data are sourced from the “Geographical Remote Sensing Ecological Network Science Data Registration and Publishing System” (www.gisrs.cn). This data calculates the impact weights of GDP distribution based on nighttime light brightness, land use types, and residential density, standardizes the processing, and combines it with population spatial distribution at a resolution of 250 m.

Land use type data are visually interpreted from remote sensing images with a Kappa coefficient greater than 0.8, ensuring feasibility. Landscape disturbance reflects the landscape’s ability to resist external disturbances and its self-recovery capacity. The higher the disturbance degree, the greater the vulnerability, obtained by weighting landscape fragmentation, separation, and dominance, with a resolution of 30 m.

Other data include Net Primary Productivity (NPP) of vegetation from the US Geological Survey (https://www.usgs), with a resolution of 500 m, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data from the “Geographical Remote Sensing Ecological Network Science Data Registration and Publishing System” (www.gisrs.cn), with a resolution of 30 m.

Research methods

Selection of ecological vulnerability indicators

The SRP (Sensitivity-Recovery-Pressure) model is a comprehensive evaluation tool. It selects indicators closely related to the specific area and ecological vulnerability, assigns weights and indices to each indicator, and then performs multiplication and cumulative summation to calculate the ecological vulnerability index. This model considers not only the sensitivity and resilience of the ecosystem but also the pressures it endures, providing a comprehensive assessment of ecological vulnerability3. With ongoing optimization, this model’s application in ecological vulnerability assessment has become more extensive and in-depth41. This study references the selection of indicator systems used by other scholars for evaluating ecological vulnerability and spatiotemporal differentiation in karst regions. It combines these with the primary causes and manifestations of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs to construct an indicator system composed of ecological sensitivity, recovery, and pressure21. The Karst WHSs ecosystem is a complex integrated ecosystem composed of natural and socio-economic components, influenced by various factors. Therefore, the evaluation indicators are diverse1. In this study, ecological sensitivity refers to the sensitivity and instability of the Karst WHSs ecosystem when impacted by external disturbances, represented by meteorological and topographical factors. Ecological recovery refers to the ecosystem’s ability to recover or approach its original ecological state after disturbance, represented by vegetation indicators. Ecological pressure refers to the intensity of human social activities’ interference with the Karst WHSs ecosystem, represented by human disturbance pressure3. Considering the importance, urgency, and uniqueness of ecological environment protection in Karst WHSs, this study selects dryness, annual precipitation, annual temperature, aspect, slope, topographic relief, DEM, NDVI, NPP, landscape disturbance, and GDP of the years 2014, 2018, and 2022 as indicators to construct an ecological vulnerability assessment index system (Table 1).

Index standardization

To address inconsistencies in dimensions and comparability between different indicators, we used the range method to standardize the raw data. This method converts indicator data into dimensionless values using the following formulas:

Positive Indicators:

Negative Indicators:

Where Yi represents the dimensionless value of the ith indicator, Xi represents the data value of the ith indicator, and Xmax and Xmin represent the maximum and minimum values of the ith indicator, respectively.

Calculation of ecological vulnerability indicator weights

The entropy weight method was used to determine the weights of the indicators. The advantages of this method include its basis on the data itself to calculate weights objectively, accurately reflecting indicator variations, and its high objectivity, which avoids subjective bias and effectively extracts data information. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

-

(1)

Calculate the proportion of the ith indicator value in the jth research unit Bij:

$${B}_{{ij}}=\frac{{X}_{{ij}}}{{\sum }_{i=1}^{m}{X}_{{ij}}}$$(3)Where Xij is the evaluation indicator, Bij is the proportion of the factor in the indicator, and m is the total number of research units, 1 ≥ i ≤ m.

-

(2)

Calculate the entropy value of the jth indicator Ej:

$${E}_{j}=-K\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{m}{B}_{{ij}}\cdot {ln}{B}_{{ij}}$$(4)where K = 1/ln(n), K > 0; m is the number of research samples, Ej > 0; to make ln\({B}_{{ij}}\) Meaningful, assume ln\({B}_{{ij}}\) = 0, when \({B}_{{ij}}\) = 0.

-

(3)

Calculate the differentiation coefficient of the jth indicator \({y}_{i}\):

$${y}_{i}=(1-{E}_{j})\left/\left(m-\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{m}{E}_{j}\right)\right.$$(5) -

(4)

Calculate the weight of the jth indicator Wj:

Where n represents the number of evaluation indicators, 11 ≥ j ≤ n;0 ≤ \({y}_{i}\) ≥ 1.

Ecological vulnerability assessment

Calculation of ecological vulnerability index

The comprehensive index method was used to evaluate ecological vulnerability, suitable for multi-element regional evaluation, combining dominant factors with comprehensive analysis. This method reflects the comprehensiveness, systematic, and hierarchy of the evaluation, allowing us to accurately determine the vulnerability index and its causes. The ecological vulnerability index (EVI) for the study area was calculated using the following formula:

Where EVI is the ecological vulnerability index, Si represents the standardized value of the ith indicator, n is the total number of indicators in the criterion layer, and Wi is the weight of the ith indicator. The higher the EVI value, the greater the ecological vulnerability of the area, and vice versa.

Classification of ecological vulnerability

After calculating the EVI using formula (7), the EVI was classified to visually display the vulnerability status of the Karst WHSs ecosystem. Based on the actual situation of the study area and referencing domestic and international research, the ecosystem vulnerability was divided into five levels: slight vulnerability (I: EVI ≤ 0.2), mild vulnerability (II: 0.2 < EVI ≤ 0.3), moderate vulnerability (III: 0.3 < EVI ≤ 0.4), intensive vulnerability (IV: 0.4 < EVI ≤ 0.45), and severe vulnerability (V: 0.45 < EVI ≤ 1.0)42.

Geodetector model

The spatial differences in ecological vulnerability result from the influence of certain factors. The Geodetector, developed by the team of Jinfeng Wang from the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, is a primary method for analyzing spatiotemporal evolution patterns and driving mechanisms43. This tool accurately assesses the impact of different factors on the distribution and development of geographical phenomena, revealing the driving forces behind geographical phenomena through quantitative analysis. Its advantage lies in not requiring numerous assumptions, and overcoming the limitations of traditional methods in handling classification problems. To further explore the spatiotemporal distribution and evolution patterns of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs, this study used the factor detector and interaction detector methods of the Geodetector to investigate the dominant factors and main driving mechanisms of ecological vulnerability.

The factor detector primarily detects the influence of various factors on the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs. The calculation formula is:

Where \(q\) serves as the evaluation standard for the explanatory power of indicator X on ecological vulnerability E; n represents the total sample size; L indicates the number of classifications of the evaluation indicator; \({n}_{h}\) and \({\delta }_{h}^{2}\) represent the sample size and variance of the ecological vulnerability indicator in the hth layer, respectively. The value range of \({q}_{X,E}\) is [0, 1]; the elevated value indicates a stronger capacity of indicator X to elucidate the ecological vulnerability of the area.

The interaction detector identifies the explanatory power of multiple influencing factors on geographical phenomena when they interact. Specifically, it analyzes whether the interaction of factors X1 and X2 will enhance or weaken their impact on the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs. The specific interaction types are shown in Table 2.

Results and analysis

Spatial distribution characteristics of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs

Employing the entropy weight method, we calculated the weights for the 11 evaluation factors in the ecological vulnerability assessment system for Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang WHSs in 2014, 2018, and 2022. The annual weight values for each metric are detailed in Table 3. Utilizing formula (10), we calculated the EVI of the WHSs. Subsequently, Subsequently, we mapped the spatial distribution of ecological vulnerability, referring to the grading criteria of Karst WHSs (Fig. 2).

In 2014, the EVI of Shibing WHS ranged from 0.187 to 0.507. According to the vulnerability level, as shown in Fig. 2, the overall vulnerability was primarily mild and moderate, accounting for 97.75% of the total aera. Intensive vulnerability areas were mostly scattered in the buffer zone, with a few in the northeastern part of the heritage site. Moderate vulnerability areas were also mainly in the buffer zone, with fewer in the heritage site itself. Mild vulnerability areas were more common within the heritage site, with higher concentrations in the northern part of the buffer zone and fewer in the south. In 2018, EVI ranged from 0.108 to 0.457, with mild and slight vulnerability areas accounting for 90.4%. Moderate vulnerability areas were mainly in the buffer zone, with fewer in the north and more in the south. In 2022, EVI ranged from 0.120 to 0.523, with slight, mild, and moderate vulnerability areas accounting for 99.02%. Intensive and moderate vulnerability areas were also distributed in the buffer zone, while the heritage site itself was mainly slight and mild.

The EVI of Libo-Huanjiang WHS ranged from 0.097 to 0.560 in 2014(Fig. 2). The overall vulnerability was primarily moderate, mild, and slight, accounting for 96.62% of the total area (Fig. 3). Intensive and moderate vulnerability areas were mainly around the buffer zone of the Small and Large Seven-Hole Scenic Areas, with moderate vulnerability areas also within these scenic areas. The eastern part of the heritage site was primarily slight and mild. In 2018, EVI ranged from 0.093 to 0.634, with moderate, mild, and slight vulnerability areas accounting for 86.56%. Severe and intensive vulnerability areas were in the buffer zone, particularly in the northeast, with a few in the Small and Large Seven-Hole Scenic Areas. Slight and mild vulnerability areas were mainly in the core area of the Maolan Scenic Area in the southwest. In 2022, EVI ranged from 0.131 to 0.611, with mild, moderate, and intensive vulnerability areas accounting for 91.51%. Similar to 2018, Severe and intensive vulnerability areas were mainly in the buffer zone, particularly in the northeast and central buffer zones, with a few in the Small and Large Seven-Hole Scenic Areas. Slight and mild vulnerability areas were mainly in the core area of the Maolan Scenic Area in the southwest.

From the changes in the area of vulnerability zones, in Shibing WHS from 2014 to 2022, the area of Severe vulnerability decreased by about 0.01%, intensive vulnerability decreased by 1.2%, moderate vulnerability decreased by 40.75%, while mild and slight vulnerability increased by 36.35% and 5.61%, respectively (Table 4). In Libo-Huanjiang WHS, from 2014 to 2022, the areas of severe, intensive, and moderate vulnerability increased by 5.12%, 6.88%, and 10.77%, respectively, while mild and slight vulnerability decreased by 9.35% and 13.42%, respectively (Table 5).

Analysis of spatial differentiation and driving mechanisms of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs

This study aims to analyze the spatial differences in ecological vulnerability between the two WHSs and explore the influencing factors. We selected the EVI of 2014, 2018, and 2022 as dependent variables, and the 11 evaluation indicators of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs as independent variables. The values of the dependent and independent variables were extracted on a 30 m × 30 m grid scale. Using SPSS software’s K-means clustering tool, the independent variables were classified into five categories, converting numerical values into clustered quantities. These data were then applied to the Geodetector model to investigate the key mechanisms influencing changes in ecological vulnerability.

The Geodetector factor detection results (Table 6) show that in Shibing WHS from 2014 to 2022, the strongest influencing factors were annual precipitation, NPP, and DEM; and the top five strongest explanatory power of the three-year combined q values are annual temperature, annual precipitation, NPP, dryness, and landscape disturbance. In Libo-Huanjiang WHS, the strongest influencing factors from 2014 to 2022 were annual precipitation, annual precipitation, and dryness; and the top five strongest explanatory power of the three-year combined q values are annual precipitation, landscape disturbance, NPP, dryness, and DEM. Therefore, long-term influencing factors on ecological vulnerability changes in both sites include annual precipitation, dryness, landscape disturbance, and NPP.

The interaction detector results indicate that the interactions between any two influencing factors in both study areas showed double-factor enhancement and nonlinear enhancement, meaning that the combined influence of any two factors on ecological vulnerability exceeds the influence of a single factor. Thus the ecological vulnerability of WHSs results from the synergistic effects of various factors.

In Shibing WHS in 2014, the top three interactions in explanatory power were annual precipitation ∩ landscape disturbance, annual temperature ∩ landscape disturbance, and annual precipitation ∩ aspect (Fig. 4), with q-values of 0.8785, 0.8767, and 0.8078, respectively. In 2018, the top three were NPP ∩ landscape disturbance, aspect ∩ NPP, and NPP ∩ topographic relief, with q-values of 0.8288, 0.8259, and 0.7654, respectively. In 2022, the top three were DEM ∩ landscape disturbance, dryness ∩ landscape disturbance, and landscape disturbance ∩ annual temperature, with q-values of 0.7654, 0.693, and 0.6715, respectively. The analysis indicates that in Shibing WHS, the interactions of landscape disturbance, NPP, annual temperature, and annual precipitation with other factors are particularly significant, with explanatory power greater than 67%, suggesting that the complex interactions of land use patterns and vegetation photosynthetic efficiency exacerbate the ecological vulnerability of the heritage site.

In Libo-Huanjiang WHS, the top three interactions of 2014 in explanatory power were annual precipitation ∩ NPP, annual precipitation ∩ DEM, and annual precipitation ∩ landscape disturbance (Fig. 5), with q-values of 0.4552, 0.4308, and 0.3937, respectively. In 2018, the top three were annual precipitation ∩ landscape disturbance, annual precipitation ∩ NPP, and annual precipitation ∩ DEM, with q-values of 0.5504, 0.4752, and 0.4701, respectively. In 2022, the top three interactions were dryness ∩ NPP, dryness ∩ landscape disturbance, and dryness ∩ DEM, with q-values of 0.4190, 0.4135, and 0.3785, respectively. The analysis indicates that in Libo-Huanjiang WHS, the interactions of annual precipitation, dryness, landscape disturbance, and NPP with other factors are particularly significant, with explanatory power greater than 37%. The suggests that the complex interactions of climate and land use changes further increase spatial differences and exacerbate ecological vulnerability in the heritage site. Overall, landscape disturbance, annual precipitation, and NPP are the key factors influencing ecological vulnerability in both sites.

X1: Dryness, X2: Annual Precipitation, X3: Annual Temperature, X4: Aspect, X5: Slope, X6: Topographic Relief, X7: DEM, X8: NDVI, X9: NPP, X10: Landscape Disturbance, X11: GDP

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

This study uses the SRP model to explore the spatiotemporal trends of ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs. Using a spatial grid scale, enables more precise identification and management of ecologically vulnerable areas and more effective monitoring of changes in ecological vulnerability, thus allowing for more targeted protection measures. The results show that the overall ecological vulnerability index of the two heritage sites is relatively low, with Libo-Huanjiang WHS having a slightly higher vulnerability index compared to Shibing WHS. As a tourism highlight in Guizhou Province, the Karst WHSs, including the Libo Xiaoqikong and Daqikong scenic areas, receive a high number of visitors each year. Additionally, the completion of the Yaoshan Ancient Village 4A scenic area (Yaoshan Scenic Area) in 2020, just 8 kilometers from the east gate of the Xiaoqikong Scenic Area, have brought tourist development and operations that overlap with the highly vulnerable buffer zone in the central area of Libo WHS. In comparison, Shibing WHS has lower visibility than Libo WHS, with fewer tourist visits and tourism facilities, showing a decrease in vulnerability followed by a slight increase; however, the overall trend over the past decade has been a decrease. Consequently, the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs is significantly impacted by tourism development. Thus, while promoting tourism and local economic development, it is essential to conduct thorough environmental assessments and monitoring of heritage sites to achieve a balance between economic growth and the protection of heritage ecosystems. In Libo WHS, efforts should be made to ensure comprehensive assessments and monitoring of tourism development, especially for projects within the core areas of the heritage site, to minimize human impact on these regions, prevent overdevelopment, and reduce environmental impact. In Shibing WHS, ongoing focus should be placed on environmental protection of the core area, land use management in the buffer zone, and the continuation of ecological restoration projects.

The Geodetector offers a spatial analysis tool capable of revealing the interactions and spatial distribution characteristics among different geographical factors. It can quantitatively identify the key factors influencing geographic phenomena, providing precise explanations for understanding geographical processes. Results from the factor detector in this study show that year-specific factors shaped the spatial distribution characteristics of ecological vulnerability in each year, while landscape disturbance, vegetation, and climate change also stand out as major factors affecting ecological vulnerability in Karst WHSs. Both natural conditions and human activities impact ecological vulnerability by reducing habitat carrying capacity, intensifying the degradation of ecosystem structure and function, and weakening resilience to external disturbances. Interaction detector results indicate that the complex synergistic effects of various factors provide a stronger explanation of ecological vulnerability than any single factor, further demonstrating that the ecological vulnerability of Karst WHSs results from the combined influence of multiple factors. In recent years, apart from climate change, factors such as scenic area development, village construction, and policies like the national “Red Line of Farmland Protection” have contributed to an increase in vulnerability in buffer zones. However, the core areas remain strictly protected, with no significant increase in ecological vulnerability observed. To address these findings, the following recommendations are proposed: First, employ a multi-factor collaborative management approach, focusing on landscape disturbance, vegetation protection, and climate adaptability. For example, by implementing vegetation restoration and wetland protection, and using ecological restoration combined with climate-adaptive strategies, human disturbances can be reduced, effectively enhancing regional biodiversity. Second, adopt differentiated protection strategies for core and buffer zones. Implement strict management in core areas to protect the native ecosystem, while in buffer zones, allow limited eco-friendly tourism activities. Moderate and rational development in buffer zones alleviates tourist pressure, providing a balanced approach to protecting the ecological environment of heritage sites. Third, strengthen ecological monitoring and early warning systems to promptly identify and respond to ecological risks in highly vulnerable areas. New technologies can be used to monitor and track vegetation and soil conservation, establishing an ecological early warning mechanism supported by big data for disaster prevention and ecological protection. Fourth, continue to promote community involvement in conservation. Explore improved ecological compensation and benefit-sharing mechanisms to balance ecological protection with the improvement of residents’ livelihoods.

Conclusion

This study selected 11 evaluation indicators and used the entropy weight method to determine their weights. It analyzed the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and evolution of ecological vulnerability in Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang WHSs from 2014 to 2022, using the Geodetector to identify the main driving factors. The conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Temporal Dimension: From 2014 to 2022, the comprehensive ecological vulnerability index of Shibing WHS first decreased and then increased, but overall showed a positive trend. The ecological vulnerability of Libo-Huanjiang WHS slightly increased, but the overall vulnerability index remained low.

-

(2)

Spatial Distribution: Both Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang WHSs have lower vulnerability in core areas and relatively higher vulnerability in buffer zones. Scenic areas and villages with high tourist reception and extensive tourism development have relatively high vulnerability.

-

(3)

Evolutionary Drivers: All indicators significantly influence ecological vulnerability, with landscape disturbance index, annual precipitation, and NPP having the greatest impact. Topographical factors such as slope, aspect, and topographic relief have the least impact. The explanatory power of interactions between any two factors is greater than that of single factors, indicating that multi-factor interactions cause ecological vulnerability.

Based on the findings from the SRP and Geodetector analysis, the ecological vulnerability of the Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang WHSs is relatively low; however, potential risks should not be overlooked. The findings can inform the development of scientific management strategies aimed at promoting the long-term protection and sustainable development of WHSs. Strengthening the monitoring of climate, vegetation, and tourism data, establishing a vulnerability early warning system, and conducting necessary project evaluations are essential. Moreover, due to this study is based on small-scale spatial analysis and the availability of indicators, the human activity factors have not been further refined. Therefore, future studies on Karst WHSs should include more indicators of human impact, integrate multiple factors, select higher resolution remote sensing data, and develop a more scientific and comprehensive evaluation system.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Abbreviations

- WHS:

-

World Heritage Site

- SRP:

-

Sensitivity-Recovery-Pressure

- PSR:

-

Pressure-State-Response

- VSD:

-

Vulnerability-Sensitivity-Adaptation

- GIS:

-

Geographic Information System

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- DEM:

-

Digital Elevation Model

- NPP:

-

Net Primary Productivity

- NDVI:

-

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index

- EVI:

-

Ecological Vulnerability Index

References

Beroya-Eitner, M. A. Ecological vulnerability indicators. Ecol. Indic. 60, 329–334 (2016).

Yue, X., Zhang, L. X., Zhou, D. C., Yue, J. & Liu, L. L. Analysis of Ecological Vulnerability and Its Controlling Factors in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Region Based on Vegetation Net Primary Productivity. Geographical Sci. 44, 110769 (2024).

Xu, C. X., Lu, C. X. & Huang, S. L. Ecological Vulnerability and Its Influencing Factors in the Zhangjiakou Area. J. Nat. Resour. 35, 1288–130 (2020).

Yun, X. J., Hou, X. Y., Liu, G. X. & Yin, Y. T. Research progress of vulnerability assessment on grassland ecosystem under climate change. Agric. Sci. Technol. 13, 2186–2190 (2012).

Zhang, X. L., Yu, W. B., Cai, H. S. & Guo, X. M. Review of the evaluation methods of regional eco-environmental vulnerability. Acta Ecologica Sin. 38, 5970–5981 (2018).

Liu, J. R., Zhao, J., Shen, S. M. & Zhao, Y. J. Evaluation of Ecological Vulnerability in the Qilian Mountain Area Based on the SRP Conceptual Model. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 43, 1573–1582 (2020).

Xie, Z. L. et al. Spatial Control Strategies for Zhujiajian Island Based on Island Ecological Vulnerability Simulation. Chinese. J. Appl. Ecol. 30, 2783–2792 (2019).

Li, Y. H. et al. Spatiotemporal Differentiation of Ecological Vulnerability in Natural Disaster-Prone Areas Based on the SRP Model: A Case Study of Chaoyang County, Liaoning Province. Geographical Sci. 35, 1452–1459 (2015).

Hou, W. J., Gao, J. B., Peng, T., Wu, S. H. & Dai, E. F. Advances in the Study of Ecological Vulnerability of Southwest Karst Ecosystems under the Framework of Structure-Function-Habitat. Prog. Geographical Sci. 35, 320–330 (2016).

Liu, C. X., He, Q. Q. & Li, Y. C. Spatiotemporal Evaluation of Socio-Ecological-Economic System Vulnerability: A County-Level Analysis of Chongqing, China. Sustainability 12, 3912 (2020).

Fan, Y. X. & Shi, Z. H. Evaluation of Ecological Environmental Vulnerability Based on Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process: A Case Study of the Ecological Barrier Area of the Three Gorges Reservoir in Hubei. J. Soil Water Conserv. 32, 91–96 (2018).

Giglio, E. Landscape ecological method to study agriculture vegetation: Some examples from the po valley. Ann. di Botanica 6, 95–110 (2016).

Xenarios, S., Nemes, A., Sarker, G. W. & Sekhar, N. U. Assessing vulnerability to climate change: Are communities in flood-prone areas in Bangladesh more vulnerable than those in drought-prone areas? Water Resources and Rural. Development 7, 1–19 (2016).

Wirehn, L., Danielsson, A. & Neset, T. S. Assessment of composite index methods for agricultural vulnerability to climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 156, 70–80 (2015).

Yu, B. H. & Lv, C. H. Evaluation of Ecological Vulnerability in the High-Cold Area of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geographical Res. 30, 2289–2295 (2011).

Yang, Y., Zhou, D. C., Gong, Z. N., Liu, Z. Y. & Zhang, L. X. Analysis of Ecological Vulnerability and Its Controlling Factors in the Loess Plateau Region Based on Vegetation Productivity. J. Ecol. Environ. 31, 1951–1958 (2022).

Ru, S. F. & Ma, R. H. Evaluation, Spatial Analysis, and Prediction of Ecological Vulnerability in the Yellow River Basin. J. Nat. Resour. 37, 1722–1734 (2022).

Zhu, Q. et al. Ecological Vulnerability Assessment in and Around the Changbai Mountain National Nature Reserve. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 30, 1633–1641 (2019).

Jin, Y., Meng, J. J. & Huang, J. Evaluation of Ecological Vulnerability of the Maowusu Sandy Grassland over the Past 50 Years: A Case Study of Wushenqi, Inner Mongolia. J. Peking. Univ. 47, 909–915 (2011).

Sahoo, S., Dhar, A. & Kar, A. Environmental vulnerability assessment using Grey Analytic Hierarchy Process based model. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 56, 145–154 (2016).

Li, H. G. et al. Temporal and spatial changes of ecological vulnerability in southwestern karst mountains based on SRP model. Ecol. Sci. 40, 238–246 (2021).

Liu, C. Q. et al. Research on Biogeochemical Processes and Material Cycling in Karst Ecosystems: Importance, Current Status, and Trends. Front. Earth Sci. 16, 1–12 (2009).

Yuan, D. X., Jiang, Y. J., Shen, L. C., Pu, J. B. & Xiao, Q. Modern Karstology (Science Press, 2016).

Chen, H. S., Nie, Y. & P,Wang, K. L. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity of water and plant adaptation mechanisms in karst regions: A review. Acta Ecol. Sin. 33, 0317–0326 (2013).

Zhu, D. Y., Xiong, K. N. & Xiao, H. Multi-time scale variability of rainfall erosivity and erosivity density in the karst region of southern China, 1960–2017. Catena. 197, 104977 (2021).

Xiong, K. N., He, C., Zhang, M. S. & Pu, J. B. A New Advance on the Improvement of Forest Ecosystem Functions in the Karst Desertification Control. Forests. 14, 2115 (2023).

Zhang, S. H., Xiong, K. N., Qin, Y., Min, X. Y. & Xiao, J. Evolution and determinants of ecosystem services: insights from South China Karst. Ecol. Indic. 133, 108437 (2021).

Williams, P. W. World Heritage Caves and Karst——A Thematic Study (IUCN, 2008).

UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2019). http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines.

Chen, Y., Xiong, K. N., Ren, X. D. & Cheng, C. An overview of ecological vulnerability: a bibliometric analysis based on the Web of Science database. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 12984–12996 (2022).

Zhang, J., et al. Exploring the synergy between Karst World Heritage site’s OUV conservation and buffer zone’s tourism industry development: a case study of the Libo-Huanjiang Karst. Herit. Sci. 11, 202 (2023).

Xiong, K. N., Chen, D., Zhang, J., Gu, X. Y. & Zhang, N. Synergy and regulation of the South China Karst WH site integrity protection and the bufer zone agroforestry development. Herit. Sci. 11, 218 (2023).

Zhang, M., Xiong, K. N., Zhao, X. & Lv, X. X. Mapping and assessment of karst landscape aesthetic value from a world heritage perspective: a case study of the Huangguoshu Scenic area. Herit. Sci., 12, 195 (2024).

Xiong, K. N., Zhang, S. R., Fei, G. Y., Jin, A. & Zhang, H. P. Conservation and Sustainable Tourism Development of the Natural World Heritage Site Based on Aesthetic Value Identification: A Case Study of the Libo Karst. Forests 14, 755 (2023).

Bai, X., Xiong, K. N., Chen, Y. & Liu, Z. Q. Spatiotemporal evolution of landscape stability in World Heritage Karst Sites: a case study of Shibing Karst and Libo-Huanjiang Karst. Herit. Sci. 12, 215 (2024).

Chen, Q. W., Lu, S. X., Xiong, K. N. & Zhao, R. Coupling analysis on ecological environment fragility and poverty in South China Karst. Environ. Res. 201, 111605 (2021).

Yan, N. et al. A comparative study of terrestrial algal species diversity in World Natural Heritage sites. J. Ecol. 41, 9593–9603 (2021).

UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 2008). https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines.

Xiong, K. N., Li, G. C. & Wang, L. Y. Study on the protection and sustainable development of south China karst Libo world natural heritage site. Chin. Gard. 28, 66–71 (2012).

Xiong, K. N., Xiao, S. Z., Liu, Z. Q. & Chen, P. D. A comparative analysis on world natural heritage value of south China karst. China Eng. Sci. 10, 17–28 (2008).

Li, Y. H. et al. Study on the Spatiotemporal Differentiation of Ecological Vulnerability in Natural Disaster-Prone Areas Based on the SRP Model: A Case Study of Chaoyang County, Liaoning Province. Geographical Sci. 35, 1452–1459 (2015).

Zhou, M. Y., Cai, Y. L., Zhang, L. F., Liu, J. & Song, X. J. Study on the Spatiotemporal Pattern Change of Regional Ecological Vulnerability before and after the Establishment of Helan Mountain National Nature Reserve in Ningxia. Ecol. Sci. 38, 78–85 (2019).

Wang, J. F. & Xu, C. D. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geographica Sin. 72, 116–134 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program (No. 220 2023 QKHZC), the Major Special Project of Provincial Science and Technology Program of Guizhou (No. 6007 2014 QKHZDZXZ), and the China Overseas Expertise Introduction Program for Discipline Innovation (No. D17016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q.Z. and K.N.X. developed the concept of this work. Y.Q.Z. wrote the manuscript, K.N.X. reviewed the whole text and made comments and suggestions to improve it. Y.C. and X.B. were involved in collecting data and producing some of the images. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Xiong, K., Chen, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal changes and driving factors of ecological vulnerability in karst World Heritage sites based on SRP and geodetector: a case study of Shibing and Libo-Huanjiang karst. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 65 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01584-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01584-3

This article is cited by

-

Nonlinear CO2 degassing dynamics in the Lijiang River Basin of the World Heritage Site

npj Heritage Science (2025)