Abstract

The preservation and restoration of palm leaf manuscripts face numerous challenges, such as diverse types of damage, material fragility, and the absence of standardized and scientific restoration methods. This work employed a Yunnan-engraved PLM to systematically elaborate and enhance the restoration process. The primary types of damage were identified, and different restoration materials were evaluated. The PLM surfaces were found to be contaminated, and material loss occurred during restoration. Wiping with warm water was conducive to the removal of surface contamination, while the use of inlay techniques and a composite restoration paste effectively repaired the damaged areas and enhanced the structural stability of the manuscript. This study established a systematic restoration procedure for engraved PLMs and improved the restoration quality to provide a feasible practical solution for the long-term preservation of engraved PLMs and similar manuscripts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Palm leaf manuscripts (PLMs), which represented a dominant literary medium in South and Southeast Asia prior to the advent of paper, are now emerging as invaluable components of global cultural heritage1. These manuscripts not only preserve knowledge across diverse fields, such as history, literature, philosophy, art, and science, but they also hold significant cultural and religious value in Buddhism2,3,4,5. Around the 7th century AD, PLMs were introduced to the Yunnan region of China via Myanmar and Thailand following the southern transmission of Theravada Buddhism from Sri Lanka4,6. In China, the tropical climate of Xishuangbanna offers an optimal environment for the cultivation of talipot palm, which is the primary sources of these manuscripts. Consequently, this region has become the only area in China that preserves the traditional skills and cultural practices associated with the creation and use of PLMs. This region hosts a considerable number of PLMs with rich content, which are also known as the “Encyclopedia of Dai Culture.”

Since natural organic materials are primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, PLMs are susceptible to damage from high temperatures, humidity, biological erosion, and other factors. Common types of damage include insect damage, stains, missing fragments, fraying fibers, tearing, and hole wear. These issues severely affect the structural stability of the manuscripts and the integrity of the information they contain, thereby rendering it imperative to conduct effective conservation and restoration work7,8.

In recent years, important developments have been reported in terms of the material analysis5,9,10,11, processing techniques2,12,13,14, classification and assessment of degradation types15,16,17,18, and suitable storage environments19,20,21 of PLMs. Recent work has also explored the properties and application strategies of various restoration materials, including papers, bark strips, paper pulps, and palm leaf segments, as well as adhesives, such as wheat starch, methylcellulose, and isinglass7,8,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. These studies have led to the accumulation of valuable experience with regards to restoration practices, while also providing a theoretical basis for the conservation of PLMs.

However, current restoration processes continue to exhibit a number of shortcomings. First, the selection of restoration materials is based mainly on empirical judgment, which can lead to compatibility or stability issues. For example, starch-based adhesives are prone to molding in high-humidity environments28,32, while methylcellulose forms a shiny film layer on the surface, thereby affecting the appearance of the manuscript8. Second, current restoration processes lack systematicity and standardization. Consequently, a lack of technical standards for key processing steps can easily lead to a range of issues. For example, inappropriate thinning and patching operations can obscure the original text or cause damage to the leaf structure. Moreover, certain materials and techniques can cause irreversible damage to the manuscript and accelerate its degradation. For example, resin-based materials cannot meet the reversibility requirements of restoration, and a contradiction exists between the structural stability and visual harmony of such patching materials28. Considering these issues, it is evident that relying solely on empirical material and process selection is not sufficient for achieving the effective scientific restoration of PLMs.

Although a number of studies have employed microscopic imaging8,9,30, physical measurements17,30, and chemical analysis techniques5 to assist in the identification of damage, significant shortcomings remain with regards to verifying the suitabilities of restoration materials, the design of the restoration process, and the assessment of technological effects. These limitations restrict the scientific standardization and promotion of restoration work, and have become key bottlenecks that must urgently be overcome in the field of PLM conservation.

Thus, to investigate scientific detection techniques and systematic restoration processes for PLMs, the current study focuses on an ancient Dai-language-engraved PLM from Yunnan, China. This engraved PLM was created by inscribing text onto palm leaves using a stylus-like instrument, thereby differing from the written PLMs originating from Xizang, China4,33. Through the integration of modern scientific methods and the development of scientific and standardized restoration protocols, this study aims to provide innovative technological solutions and conceptual frameworks for the restoration and long-term preservation of engraved PLMs. Additionally, it is expected to offer valuable insights and references for the restoration and protection of similar manuscripts, with the aim of contributing to the advancement of standardized practices for PLM conservation.

Methods

Materials

The production of PLMs involves a series of meticulous steps, including leaf collection, cutting, steaming, polishing, flattening, air drying, engraving, inking, and binding2,13,14,34,35. These manuscripts were drawn from the leaves of talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera), a tall and robust arborescent plant distinguished by its long, wide, and densely textured leaves6,9,15,36.

The PLM ( , Bala Shanghaya) employed in the current study is a significant Buddhist Jātaka text inscribed in the “Old Dai (Tai Lü) script.” This text is written in left-to-right and top-to-bottom orders and comprises six lines. It measures approximately 49.8 cm in length and 4.3–4.9 cm in width; it is slightly wider in the middle than at the ends. This manuscript has been widely circulated in the Xishuangbanna region of Yunnan, China, and has profoundly influenced the historical heritage, religious beliefs, and social customs of the area. Notably, this PLM holds significant reference value for studying the integration and development of Theravada Buddhism in the Dai society. Additionally, it provides valuable academic resources for exploring the ethical and moral values of the Dai social life, as well as the impact of Buddhist thought on Dai ethical concepts.

, Bala Shanghaya) employed in the current study is a significant Buddhist Jātaka text inscribed in the “Old Dai (Tai Lü) script.” This text is written in left-to-right and top-to-bottom orders and comprises six lines. It measures approximately 49.8 cm in length and 4.3–4.9 cm in width; it is slightly wider in the middle than at the ends. This manuscript has been widely circulated in the Xishuangbanna region of Yunnan, China, and has profoundly influenced the historical heritage, religious beliefs, and social customs of the area. Notably, this PLM holds significant reference value for studying the integration and development of Theravada Buddhism in the Dai society. Additionally, it provides valuable academic resources for exploring the ethical and moral values of the Dai social life, as well as the impact of Buddhist thought on Dai ethical concepts.

Palm leaf patches from the Xishuangbanna region of Yunnan were handcrafted using traditional techniques. It was cut into the corresponding shapes and sizes as needed during restoration.

The palm leaf powder was prepared by crushing the palm leaves and subsequent screening using a 200-mesh sieve.

The palm leaf fibers were screened through a 40-mesh sieve to select fibers within a length range of 2–5 mm after crushing.

The composite repair paste was obtained by mixing palm leaf powder (screened through a 200-mesh sieve) and a 20 ~ 30% (w/v) gelatin solution or isinglass solution in a 1:4 ~ 1:4.5 mass ratio.

For the preparation of the gelatin solution, the required amount of gelatin was accurately weighed, mixed with 25 °C deionized water (80 mL), and soaked for 20–30 min until water absorption was complete and the material had fully expanded. Subsequently, the double boiler method (water temperature ~70 °C) was used to heat the mixture under continuous stirring until the formation of a homogeneous solution. Notably, the temperature was carefully controlled since higher temperatures (i.e., >80 °C) can cause denaturation of the protein8.

For the preparation of the isinglass solution, the required amount of isinglass was accurately weighed based on the desired concentration and volume of the solution. 25 °C deionized water (70 mL) was added to the weighed isinglass and soaked for ~12 h until water absorption was complete and the material had fully expanded. Subsequently, the double boiler method (water temperature ~70 °C) was used to heat the mixture under continuous stirring until the formation of a homogeneous solution.

The wheat starch (Zen (Jin) Shofu Japanese Wheat Paste) was purchased from TALAS, New York, USA. Wheat starch was gelatinized at approximately 70 °C to yield a 20% w/v translucent colloidal paste.

Methyl Cellulose M450 was purchased from the China National Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. M450 was dispersed in hot water at 70 °C, followed by the addition of cold water at 25 °C and subsequent standing to prepare a 5% w/v colloidal gel.

All experimental water was produced using the H2O Laboratory Water Purification System (Model: Master-S20UVF) from Hitech Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Thickness measurements

Thickness measurements were conducted using a digital micrometer thickness gauge (model: SYA1703735, Suzhou Shang’en Instruments Co., Ltd., China) in accordance with the ISO 534:2011 for determining the thickness of paper and paperboard. Given that some palm leaf samples exhibited significant damage to their left or right sides, the measurement points were selected in relatively intact areas near the binding holes, and also at the center point between the two holes, to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the experimental data. Thickness measurements were performed at three points on each leaf, namely on the left side, in the middle, and on the right side.

Color measurements

Color measurements were performed using a 3nh colorimeter (model: NR10QC, Shenzhen Sanen Shi Technology Co., Ltd., China) based on the CIE 1976 (CIELAB) L*, a*, and b* color space system established by the International Commission on Illumination. In this system, the L-axis represents the lightness value, the a-axis represents the change from green to red, and the b-axis represents the change from blue to yellow. The color difference (ΔE*) was calculated using the following formula:

Color measurements followed the same sampling principle as the thickness measurements, with three points being selected for each sample, namely one on the left side, one in the middle, and one on the right side. To ensure accuracy, color measurements were performed on both the front and back sides of the palm leaves. To prevent interference with the measurement results, special attention was paid to avoid areas containing text.

Determination of the pH value

The pH value was determined in accordance with standard GB/T 13528–2015 for determining the surface pH of paper and paperboard. For this purpose, a HANNA pH meter (model: HI99171, Hanna Instruments Co., Ltd., China) was employed. Similar to the color measurements, the pH value was measured on both the front and back sides of each palm leaf, as well as at three positions (i.e., left, middle, and right).

Aging treatment

Palm leaf patches were selected for restoration using a dry heat-aging treatment approach. This method employed a dry heat oven (Model: DHG-9240A, Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China) in accordance with the GB/T 464–2008 standard for the dry heat accelerated aging of paper and paperboard. Selection of the temperature and time parameters was performed based on preliminary experiments (i.e., 105 and 120 °C; 10, 20, 30, and 40 d).

The adhesives were treated using a humid heat-aging method to evaluate their tensile strengths. More specifically, humid heat treatment was performed using a constant-temperature and humidity chamber (Model: JW-2004, Shanghai Juwei Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., China) in accordance with the GB/T 22894-2008 standard for the accelerated aging of paper and paperboard (humid heat treatment method). The experimental conditions were set at a temperature of 80 °C and a relative humidity of 65%. The aging periods were 7, 14, and 30 d.

Tensile strength testing

The tensile strengths of the palm leaf samples were tested under different aging conditions using a universal testing machine (WDW-100, Changzhou Sanfeng Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., China). The tensile strengths of the repaired palm leaves were also measured. The test speed was set to 0.5 mm/min.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, HNB-DSC300C, Xiamen Senbei Technology Co., Ltd., China) was used to obtain the heating curves of the adhesives. Each sample was heated from 0 to 150 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min.

Microorganism identification

The surfaces of the PLM specimen were swabbed using sterile swabs and streaked onto potato dextrose agar plates. After culturing for 3–7 d at 28 °C, individual colonies were selected for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. The bacterial 16S rRNA sequence general primers 27 F (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’)/1492 R (5’-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’) and the fungal ITS general primers ITS4 (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’)/ITS5 (5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’) were employed for PCR analysis. The PCR system consisted of 2xTaq PCR Mastermix (12.5 μL), 8 F primer (0.5 μL), 1492 R primer (0.5 μL), and ddH2O (11.5 μL). The PCR protocol consisted of pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52 °C for 30 s, chain extension at 72 °C for 90 s, and 30 elongation cycles at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were subsequently separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and single target bands were sequenced. Similarity searches were conducted for all sequences in the GenBank database using BLASTn.

Results

Damage survey

A comprehensive damage survey was performed for the PLM specimen. The existing 10 palm leaves exhibited a variety of conditions, with damage primarily concentrated at the left and right ends and on the upper and lower edges of the leaves. Specific types of damage include staining, missing fragments, fraying fibers, tearing, and wear holes, as shown in Fig. 1.

More specifically, in terms of the staining damage, the surfaces of palm leaves were found to be covered with various types of dirt, including dust, grease, and adhesive tape residue. These stains not only affect the clarity of the text, thereby increasing the difficulty of reading, but they may also lead to further blurring of the inscriptions. In addition, it was observed that each leaf contained varying degrees of missing fragments, particularly the first few pages, which exhibited larger areas of loss. These missing parts affect the completeness and readability of the text, hindering a comprehensive understanding of its content. With regards to the fraying fibers, the pulling apart and loosening of the palm leaf fibers were commonly observed along the edges of exposed areas. This type of damage often compromises the structural stability of the manuscript edges, and during restoration, the fibers must be carefully realigned and reinforced to restore the edge integrity. Some pages also showed tearing at the edges or in the middle sections owing to the combined effects of material aging, long-term usage, and environmental factors. These tears not only compromise the integrity of the PLM, but they may also expand over time, leading to a decrease in the structural stability of the affected page. Furthermore, the binding holes can become enlarged or deformed over time owing to long-term handling and use. In the current investigations, it was found that the edges of the holes exhibited irregular traces, altering their shapes and sizes, and affecting the structural stabilities of the leaves.

The damage survey results for the Bala Shanghaya manuscript are listed in Table 1, wherein it is evident that the upper leaves sustained more severe damage, with the first page showing severe damage and pages 2–5 also exhibiting moderate damage. In contrast, the lower leaves (6–10 cm) showed only minor damage. Considering that such damage can affect the physical integrity of the PLM, it is essential to implement appropriate repair and protection measures to extend the manuscript lifespan and ensure the continuation of their cultural value.

Analysis of the PLM specimen

Nondestructive or minimally invasive testing methods were employed to analyze the thickness, color, and pH of the Bala Shanghaya PLM. Prior to testing, the palm leaves were numbered according to their original page order (BY1–BY10), and the front and back sides of each leaf were identified.

According to the test results outlined in Table 2, the thicknesses of the palm leaves ranged from 0.41 to 0.62 mm. The average thicknesses at the sampling points on the left side, the middle region, and the right side were determined to be 0.50, 0.51, and 0.48 mm, respectively. The minimal differences among these values indicated a relatively uniform thickness distribution across the palm leaves. Notably, the average thickness at the middle sampling point was slightly higher than that at the sides. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that the central area experiences a lesser degree of physical wear and tears than the edges, which are more susceptible to handling and environmental influences.

For the purpose of this study, the palm leaf BY5 was selected as the reference standard because of its relatively low level of contamination and wear. Based on the comparison between the BY5 and other leaves, the color measurement results indicated minimal color variations among the three sampling points on the left side, middle region, and right side of the various palm leaves (Table 3). However, some samples (e.g., BY8, BY9, and BY10) exhibited a ΔE* values > 5.0 on their back sides, indicating significant color deviations due to contamination or discoloration. Moderate cleaning treatment should therefore be implemented on the surfaces of PLMs with large color differences ensure an enhanced color uniformity.

The pH measurement results presented in Table 4 indicate that the pH values of the palm leaves range from 5.7 to 6.3, indicating a relatively mild degree of acidification. Typically, because of the more severe contamination of the upper and lower leaves compared with the middle part of an ancient book, higher acidification levels are expected in these areas. However, the acidification level in the entire manuscript investigated herein showed a high degree of uniformity, and the expected phenomenon was not observed. The reason for this phenomenon may be that these palm leaves have undergone a process of acid-base equilibrium over a long period under relatively stable storage conditions, resulting in a more uniform overall pH distribution. Additionally, the acidification levels on both the front and back sides of the palm leaves were found to be essentially consistent, further confirming the uniform distribution of the overall acidification state. Thus, considering the mild acidification level of the entire manuscript and the potential dimensional changes that deacidification treatment might cause, specialized deacidification treatment was not considered to be necessary. Rather, it was anticipated that after cleaning, the degree of acidification would decrease.

Ten bacterial and two fungal colonies were identified in the PLM specimen investigated herein. At the genus level, Bacillus and Paenibacillus were the dominant bacteria, accounting for 58.33 and 16.67%, respectively, while the remaining three strains belonged to the Priestia, Phanerochaetella and Aspergillus genera (Fig. 2). All bacterial isolates are common in soil and plant microbiota37, and recent studies have found that these microorganisms are also present in the storage environments of culture relics, consistent with the current results38,39,40. In addition, it has been found that both Phanerochaetella and Aspergillus are able to efficiently degrade cellulose and lignin, and that some strains of Bacillus have the ability to degrade cellulose41,42. These characteristics provide rationale for their detection of these microorganisms on the PLM surface, and point to the risk of biodegradation.

Restoration plan and implementation

Based on the above results, a plan was developed to adhere to the fundamental principles of conservation, including “restoration to original condition,” “minimal intervention,” “reversibility,” and “safety.” More specifically, this plan aimed to restore the manuscript to its original state while ensuring its continued usability and long-term preservation. The formulation of this restoration plan is illustrated in Fig. 3, wherein key steps are detailed, including assessment of the current PLM condition, data analysis, establishment of the technical approach, selection of restoration materials, risk assessment and mitigation strategies, and development of the restoration plan.

Establishment of restoration techniques

Based on the primary types of damage observed in PLMs, this study focuses on restoration efforts for cleaning and filling. To develop a scientific and effective restoration strategy, recommendations for improvement are proposed in combination with the damage characteristics to enhance the restoration outcomes. For this purpose, the cleaning process was divided into dry and wet cleaning. Dry cleaning involves the use of soft brushes and erasers to remove surface dust and loose dirt, whereas wet cleaning utilizes a conservative approach of using warm water for washing to minimize the impact of chemical agents on the palm leaves. The water temperature was carefully controlled to prevent warping or deformation of the leaves. This method ensures that the cleaning process is gentle and safe.

Subsequently, aged palm leaf patches with retained strength characteristics were used for the filling step. These patches were carefully selected to match the textures and thicknesses of the original leaves. The damaged areas were repaired by inlaying the composite repair paste and powder at the seams to ensure adhesion after repair. This technique not only restores the physical integrity of the leaves, but it also minimizes the visual impact of the repairs.

In terms of the binding design, the original binding form of the PLM was retained, and the traditional binding method was used to maintain the integrity and historical appearance of the manuscript. The use of such traditional techniques ensured that the manuscripts retained their cultural authenticity, while benefiting from modern conservation practices.

In addition, acid-free protective storage boxes were prepared to buffer against the effects of external humidity and acidic substances. These boxes were designed to reduce the risk of moisture and acidic corrosion. The storage environment was carefully controlled to maintain a stable relative humidity and temperature, further protecting the PLM from environmental degradation.

Overall, these restoration techniques and protective measures were implemented to extend the lifespan of the PLM, while preserving its cultural and historical significance.

Selection of the restoration materials

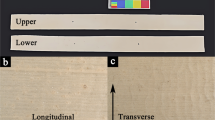

To ensure that the restoration materials were highly consistent with the original PLM in terms of their physical and chemical properties, the physical strengths of the aged palm leaf patches were evaluated. Based on the results of aging experiments, palm leaf patches subjected to 120 °C dry heat for 10 d, 105 °C dry heat for 10 d, and 120 °C dry heat for 30 d were preliminarily selected for analyses due to their close color matches to the original manuscript. Further comprehensive experiments determined that the palm leaf patches aged at 120 °C for 10 d were the most suitable restoration material because of their moderate tensile strengths and larger elongations at break (Fig. 4). These patches not only matched the color of the original manuscript, but they also met the practical requirements of the restoration work in terms of their structural stabilities and durabilities. This selection ensured that the restored sections were both visually and mechanically compatible with the original PLM, thereby enhancing the overall integrity and longevity of the restored item.

For the purpose of this study, 20% wheat starch31, 5% methylcellulose8, and 30% isinglass16 were investigated for use as the repair adhesive. Owing to its higher moisture content, wheat starch tended to cause deformation of the palm leaf material. In addition, this adhesive exhibited a long curing time, typically requiring >24 h to achieve complete setting, thereby significantly affecting the conservation quality. A long curing time will affect the controllability of the restoration operation, making it difficult to precisely control the state of the material during the process. This, in turn, increases the technical difficulty of the restoration process and may affect the final conservation outcome. In contrast, both 5% methylcellulose and 30% isinglass exhibited shorter curing times. More specifically, the curation of methylcellulose typically reached completion within 4–6 h, whereas the optimal curing of isinglass was observed within 2–4 h. Additionally, the results shown in Fig. 5a demonstrate that both wheat starch and isinglass exhibit high thermal stabilities at elevated temperatures. Methylcellulose has moderate thermal stability, with a significant endothermic peak occurring at around 40 °C. Wheat starch exhibits good thermal stability, characterized by a slow and steady endothermic process without any distinct thermal peaks. In comparison, isinglass demonstrates the best thermal stability, with an overall smooth and stable profile. Furthermore, Fig. 5b shows the changes in the tensile strengths of the different adhesives, wherein it is evident that isinglass maintained a high tensile strength throughout the aging process, demonstrating a superior stability to the other adhesives. Methylcellulose was the second most stable adhesive in terms of its tensile strength, while the starch adhesive exhibited a low tensile strength and low tensile strength stability, rendering it unsuitable for use in long-term preservation applications. Overall, isinglass outperformed the other samples in terms of both its thermal and adhesive strength stabilities, identifying it as the optimal adhesive within the scope of this evaluation.

Risk assessment and mitigation strategies

Risk assessment plays a pivotal role in anticipating difficulties and uncertainties that may arise during the restoration process. Identifying these challenges enables conservators to devise and implement appropriate preventive and mitigation strategies, thereby ensuring the smooth progress of the restoration protocol and effectively preventing secondary damage to the manuscripts. In this context, a comprehensive analysis was performed regarding the damage conditions of the PLM, the restoration techniques employed, and the selection of appropriate restoration materials. Based on this analysis, the potential risks that may emerge during the restoration process were identified, and suitable preventive and mitigation strategies were identified (see Table 5) to enhance the safety and long-term effectiveness of the restoration work.

Main restoration operations

The complete restoration steps identified based on the restoration plan are shown in Fig. 6 and are detailed in the following subsections.

During the PLM restoration process, cleaning and decontamination are crucial steps that directly affect the quality and outcomes of subsequent restorations. For the purpose of this study, the cleaning process was divided into two stages, namely dry and wet. More specifically, the primary goal of the dry cleaning process was to remove loose dust and dirt from the surface of the PLM. During the cleaning operation, antistatic dusting cloths and dust-free cotton swabs were used to gently wipe the surfaces of the pages, as shown in Fig. 7a. Special care was taken to avoid contact with the binding holes and any severely damaged areas, while also ensuring that the fibers of the cleaning materials did not catch on the irregular edges to avoid further damage. When cleaning the holes and damaged areas, wiping was performed in a single direction to minimize repeated friction, thereby reducing the risk of tearing. After cleaning each page, the dust was promptly removed to prevent cross-contamination. Additionally, it was found that the first page of the manuscript contained sections of adhesive tape. Given the strong adhesion of the tape, initial attempts to remove it were unsuccessful. Instead, cotton swabs dampened with ethanol were used to carefully lift and successfully remove the tape without causing surface damage (Fig. 7b). This method ensured that the integrity of the manuscript surface was maintained, while effectively addressing the issue of the adhesive residue.

Prior to performing the wet cleaning protocol, an ink-adhesion test was conducted to confirm the stability of the inscriptions. The test results indicated that the ink was firmly attached, and so wet cleaning was performed on the PLM. For this purpose, disposable 100% cotton cloths and dust-free cotton swabs were utilized, along with warm water maintained at a temperature of 20–40 °C (see Fig. 7c). The cleaning procedure was meticulously divided into three distinct areas, namely the left-hand, middle, and right-hand areas. Initially, a damp cotton cloth was gently wiped along the grain of the palm leaf to avoid back-and-forth friction, thereby reducing the risk of wrinkling or tearing, especially around the holes and damaged areas. Each area was wiped 2–3 times, and excess moisture was promptly removed to prevent saturation and potential deformation of the leaf. For the holes and worn areas, damp, dust-free cotton swabs were carefully used to clean delicate sections. The manuscript was securely held in place throughout the cleaning process to prevent any movement that could cause additional damage. The work surface was promptly cleaned of water stains after cleaning each area to prevent cross-contamination and ensure a clean environment for the restoration process. Subsequently, the PLM specimen was carefully placed on absorbent paper and gently flattened using a book press to ensure that the pages were both flat and dry. This step provided a stable basis for subsequent restoration operations, ensuring that the manuscript remained under optimal conditions for further treatment.

After cleaning, the L* values at all sampling points were found to increase significantly (Table 6), indicating that the systematic cleaning process effectively removed the surface dust and stains, thereby enhancing the brightness of the PLM. Additionally, the pH values of the treated samples increased (Table 6), suggesting a reduction in the degree of acidification. Overall, the above cleaning process removed surface deposits and provided a clean substrate for restoration and adhesion of the repair materials (Fig. 8).

In the restoration of PLM, the repair step is crucial for restoring the integrity and structural stability of the manuscript. To ensure that the repaired structure was robust and its appearance was natural, this study adopted a specialized repair method, as detailed in Fig. 9. More specifically, palm leaf patches selected through the aforementioned screening process were used to ensure that the texture and color matched those of the original manuscript. These patches were carefully trimmed to fit perfectly with the edges of the defects, as can be seen in Fig. 9a. With regards to marking and alignment, the edges of the defects were marked with an awl to ensure precise alignment. Additionally, the grain direction of the patch was aligned with that of the original manuscript and any excess fibers at the edges were removed. Subsequently, the adhesive was applied evenly along the edges of the defect (Fig. 9b), and the patch was precisely fitted into the defect and firmly pressed into place (Fig. 9c). To prevent gaps in the seams, a composite repair paste was used to fill the seams (Fig. 9d). Surface treatment was then performed by the application of a fine layer of palm leaf powder over the seam to enhance its strength, prevent transparency, and reduce the risk of adhesion (Fig. 9e). Notably, the work surface was kept clean throughout the above processes, and the manuscript was flattened only after the adhesive was fully cured to prevent sticking. For this purpose, the repaired palm leaves were placed on absorbent paper and pressed flat. To prevent sticking, a sheet of Hollytex interleaving paper was placed above the restored area (Fig. 9f). After drying, the leaves were trimmed and cut to ensure uniformity. For larger defects, trimming was referenced against the most intact page to ensure alignment and uniformity. The trimming process was performed after only after completion of the repair to ensure precision (see Fig. 9g). The final step in the defect repair process was binding. More specifically, based on the material, color, and thickness of the original binding cord, a suitable acid-free linen cord was selected for use. Binding was restored using a single-hole cord threading and knotting method on the left side, while maintaining consistency in the PLM structure and functionality (Fig. 9h). The replaced binding cord was preserved along with the original manuscript.

Protective encasement

To ensure the long-term preservation of a PLM specimen, appropriate encasement is crucial after performing the repair process. Thus, to effectively reduce the effects of humidity and acidic substances on the PLM, acid-free protective boxes were custom-made to store the PLM after restoration (Fig. 10). These protective measures aimed to provide a reliable storage environment for the PLM to ensure its long-term preservation and allow it to be displayed under appropriate conditions. More specifically, the protective box was fabricated according to the dimensions of the Bala Shanghaya specimen (i.e., 52 cm × 8 cm × 4.6 cm). It was primarily composed of acid-free cotton paperboard (light gray) with a pH value of 8.2. The base of the inner compartment featured a soft-walled structure composed of polyethylene foam produced using physical foaming technology. The box was equipped with a carrying rope for ease of transport. Additionally, a side panel was designed to display information for identification of the manuscript, and an upper cover plate composed of acid-free cotton paperboard was included to stabilize the position of the manuscript and prevent deformation.

Documentation of the restoration process

Upon completion of the restoration, the author compiled a comprehensive restoration archive that meticulously documented and encapsulated the entire process. This detailed documentation serves as a foundational reference for future restoration endeavors and research, ensuring that subsequent restoration activities are both well-informed and evidence-based (see Appendix Table 1. Restoration archive of the Bala Shanghaya PLM). The restoration archive includes a number of main aspects, including a survey of the initial PLM, results of the scientific analyses, the establishment of appropriate restoration techniques, selection of the restoration materials, details of the risk assessment and mitigation measures, the restoration plan, expert opinions on the restoration plan, implementation of the restoration, evaluation of restoration outcomes, and post-restoration acceptance information documentation.

Evaluation and analysis of the restoration outcomes

The quality of the PLM restoration was assessed from multiple perspectives. As shown in Fig. 11a–d, the restored manuscript pages were flat and uniform in size, with the missing parts accurately filled and the repair areas matching the original color, while remaining distinguishable (Fig. 11e, f); these characteristics are in accordance with the principles of cultural heritage restoration. Importantly, the inscriptions are clear with no evidence of ink bleeding or fading, and the overall restoration meets the technical standards for manuscript restoration. Additionally, the cord material and the method employed for threading of the binding cord match those employed during the preparation of the original PLM (Fig. 11g, h). Furthermore, the use of acid-free materials along with an acid-free protective box was expected to further extend the preservation time of this cultural heritage item.

a Recto of leaf 1 before restoration; b Recto of leaf 1 after restoration; c Verso of leaf 4 before restoration; d Verso of leaf 4 after restoration; e Detail showing extensive losses before restoration; f The same viewing angle after restoration (using the recto of leaf 5 as an example); g Broken binding cord; h Newly applied binding cord. Note: Images e and f show similar angles from different leaves; image f uses leaf 5 as an example to demonstrate restoration results.

Microscopic observations revealed that the texture of the palm leaf patches matched the original manuscript very well, and that the color difference was reasonably controlled (Fig. 12a). Under transmitted light, the repaired areas were filled with no obvious gaps (Fig. 12b). However, excessive adhesive application led to the formation of a shiny film layer on the surface after drying, thereby affecting the visual harmony (Fig. 12c). This observation suggests that the amount of applied adhesive requires further optimization. Additionally, the palm leaf powder appeared slightly whitish in color (Fig. 12d), although it should be possible to address this through artificial accelerated aging and natural air drying before powder preparation to better match the original manuscript.

a Comparison of the texture between the palm leaf insert and the original material; b Observation of the restored area under transmitted light; c Formation of a glossy film on the palm leaf surface upon the application of excess adhesive; d Slight whitening observed in the area coated with the palm leaf powder.

Discussion

This study used an engraved PLM from Yunnan as an example to systematically demonstrate the application and practice of scientific restoration methods for long-term manuscript preservation. The specific restoration steps applied to the selected PLM specimen involved the collection of basic information and assessment of the manuscript value, assessment of the PLM condition, characterization and analysis, development of a restoration plan with an appropriate risk assessment, implementation of the restoration protocol, evaluation of the restoration outcome, and establishment of the restoration documentation. The above process integrated restoration practices with modern analytical methods to effectively enhance the standardization and systematicity of the restoration operation, while also strengthening the controllability and traceability of the entire restoration process.

The main issues addressed during the restoration of the PLM in the current study were cleaning and filling. More specifically, previous conservators and researchers have proposed various solutions to these issues (Table 7), wherein cleaning and decontamination are the fundamental steps in the restoration and conservation of PLMs. Although various solvents have been previously reported for use in this step (e.g., surfactants, ethanol, trichloroethane, acetone, benzene, and carbon tetrachloride), a comprehensive evaluation of efficacy and safety identified distilled water as the optimal choice. This aligns with the principles of minimal intervention, which aims to minimize the impact of chemical agents on palm leaves16. Although cleaning with warm water is generally a safer alternative than solvents for use with palm leaf surfaces, excessive wetting should be avoided to prevent warping or deformation. Similar to wood and paper, PLMs are primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, all of which are highly hygroscopic. Indeed, fluctuations in humidity can cause manuscripts to expand or contract, resulting in physical deformation, cracking, or warping, which can ultimately lead to permanent structural loss43. Therefore, the water temperature and humidity should be carefully controlled based on the condition of the palm leaves, and localized cleaning is recommended to reduce their impact on the overall structure. Thus, in the current study, cleaning was performed carefully to avoid secondary damage. Notably, chemical cleaning agents should be selected with caution, and their safety for use with palm leaves must be assessed through preliminary tests prior to implementation.

Currently, no unified international standard exists regarding the choice of filling material for such restorations. Thus, the selection of an appropriate filling material should be based on the thickness, strength, and appearance of the original palm leaf material to ensure compatibility between the repaired and original materials. In previous restoration research performed on PLMs in South Asia, handmade paper repair, palm leaf patching, and bast paper materials are commonly employed and supplemented with various natural or synthetic adhesives7,12,14,32. In these previous works, the selection of these materials was primarily based on accumulated experience and crafting habits. Although Japanese paper and Thai mulberry paper are widely used for PLM restoration16, a suitable compatibility between these papers and the palm leaves must be ensured. Pulp filling is also an effective restoration method for severely damaged palm leaves. However, the compatibility and durability of the filling materials must also be considered to ensure the long-term stability of the restoration44.

In contrast, the current study selected palm leaf patches as the filling material, and a number of physical and chemical tests being performed to support the selection of appropriate restoration materials and the formulation of restoration plans. For example, the thickness and colorimetry data were used to quantify the match between the patch material and the original PLM in terms of the structure and visual appearance, thereby helping enhance the consistency of the restoration. Additionally, pH measurements were performed to determine the acidity or alkalinity of the restoration material, since a low pH can indicate a potential risk of acidification, which also providing a basis for developing an appropriate deacidification treatment. Furthermore, analysis of the microbial activity helped identify potential biological degradation risks and guided the formulation of mold prevention measures. Moreover, evaluation of the tensile strength allowed analysis of the bonding between the adhesive and the palm leaf material, and provided details regarding the mechanical stability of the repaired area. Thermal stability tests were also conducted to evaluate the performance of the adhesive under typical high-temperature and high-humidity storage conditions.

Notably, the above analyses helped enhance the specificity and standardization of the restoration decisions. For example, during the selection of matching materials, comparison of the thickness error and color difference between the original and repaired palm leaf patches identified that the thickness error should be controlled within ±0.03 mm, while the color difference (ΔE) should ideally be <3. Generally, it is considered that ΔE* ≤ 3 is within the range of visual harmony, whereas ΔE* ≤ 2 indicates a high degree of consistency, and the color difference is hardly perceptible to the naked eye. However, significant color differences were observed even for the palm leaves processed in the same batch, and it was difficult to adjust these values to match the original using manual methods. Ultimately, a batch of aged palm leaf patches was selected for use wherein the thickness was consistent with the original PLM and the color difference (ΔE*) was 3.29. Although this color difference was slightly higher than the ideal value, the overall visual harmony after restoration met the requirements for protective restoration. This also retains the degree of recognizability between the repaired and original areas, reflecting the application balance of the principle of reversibility in actual operations. Moreover, the pH measurement results demonstrated that the average pH value of the original PLM was 6.0, thereby representing mild acidification (pH 6.0–6.5 = mild, 5.0–6.0 = moderate, 4.0–5.0 = severe, and <4.0 = very severe acidification). Since the potential impact of alkaline treatment agents on palm leaf material is not yet clear, this study adopted a warm water cleaning method to alleviate the acidic environment while effectively controlling moisture penetration and fiber expansion, thereby achieving gentle intervention. In terms of the adhesive selection, isinglass demonstrated a good thermal stability within the range of 0–150 °C, with an initial bonding strength higher than those of wheat starch and methylcellulose. In addition, the isinglass adhesive maintained a high strength stability during artificial aging, demonstrating an excellent durability and adaptability. Consequently, this adhesive was selected for use in large-area patching restorations. These practices indicate that the scientific restoration pathway developed herein, which was supported by the evaluation of critical physical and chemical parameters, demonstrates a higher controllability and degree of effectiveness in practice when compared with traditional empirical methods.

Despite the initial success of the study, a number of limitations remain. First, the range of adhesives selected for restoration of the PLM was relatively limited, with only three types of natural or naturally derived adhesives being investigated (i.e., starch, methylcellulose, and isinglass). More specifically, this study did not consider chemically derived adhesives that have been used in the restoration of PLMs (e.g., polyvinyl alcohol, vinyl acetate, acrylic emulsions, and ethylene–vinyl acetate copolymer)7,12,15,32, thereby resulting in an incomplete assessment of adhesive compatibility.

Second, although this study introduced basic physicochemical indicators such as the thickness, colorimetry parameters, pH value, microbial activity, thermal stability, and tensile strength, the detection dimensions were still insufficient. Previous investigations into the internal structures and fundamental properties of PLMs have facilitated a profound understanding of their structure–property relationships18,45, while research into the deterioration states, aging behaviors, and hygroscopic natures of PLMs has helped define their appropriate storage conditions, while also contributing to the design suitable storage boxes2,3,11,19,20,46. Current detection methods mainly focus on the macroscopic physical properties and primary chemical attributes without considering the microstructure, chemical composition, aging behavior, and environmental adaptability of the material. This renders it difficult to fully characterize the compatibility and long-term stability of a restoration material when applied to a palm leaf substrate.

Moreover, existing scientific detection techniques have failed to establish standardized detection methods for restoration materials, and the relevant detection indicators are unclear. Future research should therefore focus on a number of aspects. First, the selection of filling and adhesive materials should be expanded, and their performance should be systematically compared in terms of the color stability, acidity/alkalinity changes, thermal stability, reversibility, and aging resistance. Second, the detection methods should be further expanded using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to analyze the chemical composition and elemental characteristics of the restoration materials and palm leaf substrates. Furthermore, the comprehensive performance of the various adhesives should be evaluated in terms of their biological stability, visual harmony, and mechanical flexibility characteristics. Third, a standardized detection parameter system for palm leaf materials should be established, along with sampling requirements and measurement specifications for various indicators (e.g., thickness, colorimetry parameters, pH, microbial activity, and tensile properties) to enhance the consistency and comparability of the data. In addition, various detection methods should be evaluated in combination with actual restoration conditions to evaluate their applicability and cost-effectiveness. Finally, priority application principles should be clarified under resource-limited conditions to enhance the effectiveness and economic profiles of the detection methods.

In summary, the current study explored the effective integration of traditional restoration techniques and modern scientific technologies during the scientific restoration of PLMs. More specifically, these techniques and technologies were evaluated in combination for the design of appropriate restoration methods, the selection of analytical parameters, and for determining their suitability for use in practical applications. The current attempts to develop standardized and data-driven approaches provide important references for the establishment and promotion of standards for future restoration work on PLMs, and offer a paradigm that can be referenced for the protection of similar ancient books.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vijaya Lakshmi, T. R., Sastry, P. N. & Rajinikanth, T. V. Feature selection to recognize text from palm leaf manuscripts. Signal Image Video Process 12, 223–229 (2018).

Yu, D. et al. The effect of traditional processing craft on the hygroscopicity of palm leaf manuscripts. Herit. Sci. 12, 280 (2024).

Zhang, W., Wang, S. & Guo, H. Study on the effects of temperature and relative humidity on the hygroscopic properties of palm leaf manuscripts. Forests 15, 1816 (2024).

Yu, C., Zhang, M. & Song, X. Analysis of two different inks and application techniques on palm leaf manuscripts through non-invasive analysis. Restaur 45, 237–256 (2024).

Sharma, D., Singh, M. R. & Dighe, B. Chromatographic study on traditional natural preservatives used for palm leaf manuscripts in India. Restaur 39, 249–264 (2018).

Zhang, J., Yu, H., Li, Y., Liu, P. & Hu, Y. Conservation of palm leaf manuscripts from a biological perspective (in Chinese). J. Fudan Univ 63, 658–666 (2024).

Agrawal, O. P. Conservation of Manuscripts and Paintings of South-East Asia. (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1984).

Van Dyke, Y. Sacred leaves: the conservation and exhibition of early Buddhist manuscripts on palm leaves. Book Pap. Group Annu. 28, 83–97 (2009).

Sharma, D., Singh, M., Krist, G. & Velayudhan, N. M. Structural characterisation of 18th century Indian palm leaf manuscripts of India. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 9, 257–264 (2018).

Singh, M. R. & Sharma, D. Investigation of pigments on an Indian palm leaf manuscript (18th–19th century) by SEM-EDX and other techniques. Restaur 41, 49–65 (2020).

Chu, S., Lin, L. & Tian, X. Evaluation of the deterioration state of historical palm leaf manuscripts from Burma. Forests 14, 1775 (2023).

Sah, A. Palm leaf manuscripts of the world: material, technology and conservation. Stud. Conserv. 47, 15–24 (2002).

Kumar, D. U., Sreekumar, G. & Athvankar, U. Traditional writing system in southern India—palm leaf manuscripts. Des. Thoughts 7, 2–7 (2009).

Ghosh, S., Mahajan, A. & Banerjee, S. Palm leaf manuscript conservation, the process of seasoning with special reference to Saraswati Mahal library, Tamilnadu in India: some techniques. Int. J. Inf. Mov. 2, 122–128 (2017).

Wiland, J. et al. A literature review of palm leaf manuscript conservation—Part 1: A historic overview, leaf preparation, materials and media, palm leaf manuscripts at the British Library and the common types of damage. J. Inst. Conserv. 45, 236–259 (2022).

Wiland, J. et al. A literature review of palm leaf manuscript conservation—Part 2: historic and current conservation treatments, boxing and storage, religious and ethical issues, ecommendations for best practice. J. Inst. Conserv. 46, 64–91 (2023).

Zhang, M., Song, X., Wang, J. & Lyu, X. Preservation characteristics and restoration core technology of palm leaf manuscripts in Potala Palace. Arch. Sci. 22, 501–519 (2022).

Yi, X. et al. Study on the material properties and deterioration mechanism of palm leaves. Restaur 45, 219–236 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Investigation on the moisture absorption behaviors of palm leaves (Corypha umbraculifera) and their variation mechanism. Langmuir 40, 25133–25142 (2024).

Zhang, W., Wang, S. & Guo, H. Influence of relative humidity on the mechanical properties of palm leaf manuscripts: short-term effects and long-term aging. Molecules 29, 5644 (2024).

Zhang, W., Wang, S., Han, L. & Guo, H. Aging effects of relative humidity on palm leaf manuscripts and optimal humidity conditions for preservation. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 1–14 (2025).

Nordstrand, O. K. Some notes on procedures used in the Royal Library, Copenhagen for the preservation of palm leaf manuscripts. Stud. Conserv. 3, 135–140 (1958).

Joshi, B. R. Preservation of palm leaf manuscripts. Conserv. Cult. Prop. 22, 120–127 (1989).

Suryawanshi, D. G., Nair, M. V. & Sinha, P. M. Improving the flexibility of palm leaf. Restaur 13, 37–46 (1992).

Joshi, Y. (ed.) Modern techniques of preservation and conservation of palm leaf manuscripts. In Proc. Conf. Palm Leaf and Other Manuscripts Indian Lang. (Inst. Asian Stud., Madras, 1995).

Harinarayana, N. Techniques of conservation of palm leaf manuscripts: ancient and modern. In Proceedings of the Conference on Palm Leaf and Other Manuscripts in Indian Languages, 261-274 (1995).

Nichols, K. An alternative approach to loss compensation in palm leaf manuscripts. Pap. Conserv. 28, 105–109 (2004).

Takagi, N., et al. Preservation cooperation in Nepal: from training to conservation and digitization of rolled palm leaf manuscripts. In Preservation and Conservation in Asia:Pre-conference of WLIC, 16–17 (2006)

Poirier, J. Delaminating and fraying fibres: developing an advanced treatment approach for the conservation of a 12th century palm leaf manuscript [EB/OL]. Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. Available at: https://chesterbeatty.ie/conservation/delaminating-and-fraying-fibres/ (Accessed 2025-06-11) (2020).

Dong, D. & Yu, C. Techniques for filling losses in palm leaf manuscripts. Restaur 45, 257–275 (2024).

Yao, N., Lv, J., Guo, H. & Wang, S. A study on the adhesive materials used in the conservation and restoration of palm leaf manuscripts. J. Fudan Univ. 63, 628–639 (2024). (in Chinese)

Crowley, A. S. Repair and conservation of palm leaf manuscripts. Restaur 1, 105–114 (1969).

Lian, X. et al. Revealing the Mechanism of Ink Flaking from Surfaces of Palm Leaves (Corypha umbraculifera). Langmuir 40, 6375–6383 (2024).

Panigrahi, A. K. & Litt, D. Odia script in palm-leaf manuscripts. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 23, 13–19 (2018).

Sahoo, J. A selective review of scholarly communications on palm leaf manuscripts. Libr. Philos. Pract 1, 1397–1427 (2016).

Freeman, R. Turning over old leaves: Palm leaves used in South Asian manuscripts. Book Pap. Group Annu. 24, 99–102 (2005).

Jiao, Y., Gao, Z., Li, G., Li, P. & Li, P. Effect of different indigenous microorganisms and its composite microbes on degradation of corn straw. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 31, 201–207 (2015). (in Chinese)

Pepe, O. et al. Heterotrophic microorganisms in deteriorated medieval wall paintings in southern Italian churches. Microbiol. Res. 165, 21–32 (2010).

Li, Q., Zhang, B., Yang, X. & Ge, Q. Deterioration-associated microbiome of stone monuments: structure, variation, and assembly. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e02680–17 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Diversity and composition of culturable microorganisms and their biodeterioration potentials in the sandstone of Beishiku Temple, China. Microorganisms 11, 429 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Transcriptomics analysis reveals the high biodegradation efficiency of white-rot fungus Phanerochaete sordida YK-624 on native lignin. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 132, 253–257 (2021).

Hajji-Hedfi, L. et al. Microbial inoculants for plant resilience performance: roles, prospects and challenges. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 132, 88 (2025).

Bylund Melin, C., Hagentoft, C.-E., Holl, K., Nik, V. M. & Kilian, R. Simulations of moisture gradients in wood subjected to changes in relative humidity and temperature due to climate change. Geosci 8, 378 (2018).

Jurkiewicz, I. Magic in conservation—using leaf-casting on paper and palm leaves. Collection Care Blog. Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2017/10/magic-in-conservation-using-leaf-casting-a-mechanical-pulp-repair-technique-on-paper-and-palm-leaves-as-the-library-i.html (Accessed 2025-06-11) (2017).

Chu, S. et al. Analysis of Aspergillus niger isolated from ancient palm leaf manuscripts and its deterioration mechanisms. Herit. Sci. 12, 199 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Study on the Aging Effects of Relative Humidity on the Primary Chemical Components of Palm Leaf Manuscripts. Polymers 17, 83 (2025).

Suryawanshi, D. G., Sinha, P. M. & Agrawal, O. P. Basic studies on the properties of palm leaf. Restaur 15, 65–78 (1994).

Jacobs, D. Workshop notes of the conservation and stabilization of palm leaf manuscripts. South Asia Libr. Group Newsl. 40, 27–28 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Palm Leaf Manuscript Conservation Foundation of Yunnan Academician Workstation (YAW23002) and National Ethnic Affairs Commission Ethnic Research Project of China (2024-GMI-036).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.Y., Y.Z., Y.H.Y. and G.Y.; methodology, P.L., Y.H., Y.H.Y., Y.L.Y., Y.Z. and G.Y.; validation, Y.L., J.Z., Y.Q., Y.L., S.W., B.Y., H.Y., Q.X., P.L. and Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.L., J.Z., Y.Q., Y.H. Y. and Y.Z.; investigation, Y.L., J.Z., Y.Q., B.Y., H.Y., P.L. and Y.H.; resources, B.Y., H.Y., Y.L., Q.X., J.Z. and Y.Z.; data curation, Y.L., Y.L., S.W., P.L. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L., J.Z., Y.Q., B.Y., H.Y., P.L. and Y.H.; supervision, P.L., Y.H., Y.H.Y., G.Y., Y.Z. and Y.L.Y.; project administration, Y.H.Y., G.Y., Y.Z. and Y.L.Y.; funding acquisition: Y.L., Y.Z. and Y.L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhang, J., Qin, Y. et al. Scientific restoration of engraved palm leaf manuscripts. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01943-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01943-0