Abstract

Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM) for traditional timber architectural heritage faces bottlenecks, including low efficiency, limited accuracy, and constraints on applying and integrating architectural expertise. An intelligent framework integrates machine vision (YOLO) with an expertise-based metamodel for traditional timber architectural heritage. The metamodel specifies core data and adaptive algorithms for automated HBIM; machine vision detects and acquires data from point-cloud images. This integrated approach provides a viable pathway to intelligent and automated HBIM for traditional timber architectural heritage and was validated on a Dong Drum Tower: for plan views, detection F1 Score 0.928 and Precision 0.969; for section views, detection F1 Score 0.873 and Precision 0.897. Automatically generated models achieved about 99% completeness, 99% accuracy, and efficiency improved by 95%. The method replaces strict geometric constraints with expertise-based construction logic, providing a new solution for data-driven intelligent HBIM suited to the numerous and typologically complex traditional timber architectural heritage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Architectural heritage encompasses buildings and their surrounding environments that possess significant historical, geographical, and cultural value, as well as towns and villages bearing equally important historical and cultural significance1. The conservation of architectural heritage is vital not only for safeguarding historical and cultural continuity but also for preserving unique cultural resources for future development, fostering sustainable economic and social growth, and underpinning advances across diverse fields2. In recent years, Building Information Modeling (BIM) has been adopted as an innovative approach in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry and has gradually found applications in cultural heritage conservation. Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM), a specialized branch of BIM, is dedicated to the integration of digital technologies with the conservation of architectural heritage. The construction and application of HBIM for architectural heritage have increasingly become a mainstream trend in heritage conservation. HBIM offers multiple advantages: it not only preserves the 3D geometric and spatial information of architectural heritage, but also integrates rich value-related information, thereby providing strong technical support for its conservation, restoration, management, and adaptive reuse3,4,5,6,7.

Since Murphy first proposed the concept of HBIM in 20098, it has received widespread attention in the fields of archeology and architectural heritage conservation9. HBIM can be defined as a library of parametric object models designed to store data associated with historic buildings10. The construction of HBIM for architectural heritage is a systematic process that involves the meticulous acquisition of complex details of architectural heritage and converting these into interactive digital models, facilitating subsequent conservation and management efforts11. Compared with traditional methods such as manual measurement, photogrammetry, and terrestrial laser scanning have, with the advancement of surveying technology, become the most common techniques for acquiring HBIM data for architectural heritage, providing essential geometric and textural information12. The captured data are then processed using specialized software tools to generate a complete digital representation of existing structures13,14,15,16. The processed data are then imported into HBIM modeling software to generate detailed models of the architectural heritage, enabling diverse applications17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Therefore, HBIM plays a pivotal role in the research and conservation of architectural heritage.

Traditional timber architectural heritage refers to historic buildings constructed primarily from wood using traditional craftsmanship and techniques, characterized by long histories, diverse architectural styles, and well-established construction systems. These structures possess significant cultural and technical value, distinctly reflecting the cultural characteristics of various historical periods and the advanced levels of architectural technology, representing an important category of architectural heritage25. The diversity and complexity of types of traditional timber architectural heritage pose numerous challenges for establishing HBIM, both in the theoretical framework and in practical applications. Currently, BIM software has significantly enhanced its support for 3D point cloud data, which can faithfully represent the surface details of heritage structures, thereby enabling an efficient workflow referred to as Scan-to-BIM. Despite these technological supports, HBIM generation for traditional timber structures remains heavily reliant on manual modeling26. This process requires operators to visually identify features in point cloud imagery within software and manually construct models by integrating point cloud data with survey data. In both research and practice, some researchers opt for manual modeling to maintain the accuracy and precision of the actual data27,28,29, while others adopt a manual mesh modeling approach based on 3D scan data to create HBIM models30. Consequently, prevailing Scan-to-BIM workflows persist as prohibitively time-consuming and error-prone manual processes. Practitioners must draw on their experience and expertise to interpret point cloud data and reconstruct target objects manually, a labor-intensive process that not only demands significant time but also potentially compromises outcomes through subjective judgments by researchers31,32. Although these studies utilizing manual modeling have established HBIM for traditional timber structures, this approach not only requires each component to be defined and modeled individually, but also necessitates manual definition of spatial positioning, structural joinery, and mortise-and-tenon joinery between components. This demands high modeler expertise and consequently leads to slow and inefficient modeling, with difficulties in ensuring modeling standardization.

In recent years, the academic community has built on manual modeling to explore automated HBIM modeling techniques. Research progress has mainly focused on three categories of approaches: rule-based methods, machine learning-based methods, and point cloud-based methods.

Rule-based methods construct models through predefined rules. This approach relies heavily on rule libraries defined by the modeler and is particularly well-suited for generating architectural elements with well-defined structural features and constructing standardized building models. In the field of automatic modeling of architectural elements33, implemented a parametric approach to automatically construct HBIM models of domes based on the geometric rules and proportional relationships of Renaissance-era dome design. Similarly34, proposed a parametric framework to generate HBIM models of vaults by applying geometric rules for vault design documented in historical sources. In the field of automated whole-building modeling35: achieved rapid automated modeling of Huizhou traditional dwellings by systematically integrating their structural grammar rules with the architectural guidelines documented in historical pattern books36. Employed parametric methods to automatically construct HBIM models of traditional Chinese architecture, based on the cai-fen modular system and construction rules defined in the Song Dynasty’s Yingzao Fashi. Furthermore37, proposed a rule-driven procedural modeling method that automates the reconstruction and generation of virtual heritage buildings through the definition and application of architectural rules. These rule-based approaches support diverse representations of architectural elements but have several inherent limitations: (1) they are constrained by predefined rules and thus lack flexibility and adaptability for complex or customized forms; (2) they do not systematically translate architectural expertise into rules, often covering only specific aspects of heritage architecture; and (3) they lack sufficient intelligence in rule application, still requiring substantial manual intervention.

Machine learning-based methods construct models through automated processes. This machine learning-based approach constructs deep learning models to effectively identify and extract key architectural elements from 3D point cloud data of architectural heritage, thereby enabling efficient processing of complex geometric and semantic information. In specific applications38,39,40,41,42, algorithms such as Random Forest, variants of the PointNet architecture, and DGCNN models have been used for semantic segmentation of 3D point cloud data, learning the geometric and semantic features of architectural elements, classifying each element, and generating semantically annotated point clouds, which are then integrated with parametric modeling techniques to transform the semantic information into HBIM. Semantic segmentation of 3D point clouds using machine vision thereby enables automatic extraction of architectural features and reduces reliance on manual intervention. This approach also has certain limitations: (1) 3D point cloud data are unordered and non-regular, requiring complex algorithms to handle spatial relationships, resulting in low computational efficiency and limited detection accuracy; (2) processing 3D point cloud data demands higher hardware requirements, far exceeding those of 2D image processing, with substantial computational resource consumption; (3) annotating 3D point clouds requires point-by-point or region-based category labeling in 3D space, involving complex operations and reliance on specialized tools, leading to high annotation costs; (4) complex building structures may cause loss of local details or global semantic confusion, making multi-scale feature fusion difficult. Therefore, to address these limitations, object identification can be simplified by integrating architectural expertise. Automated parametric HBIM modeling is explored through semantic segmentation performed on 2D sliced point cloud images.

Point cloud–based methods construct models through automated or semi-automated conversion of point cloud data. This approach primarily employs laser scanning or photogrammetric techniques to acquire point cloud data and transform it into three-dimensional models through automated or semi-automated workflows, making it particularly well-suited to reverse modeling of existing buildings. In specific applications, researchers have employed various methods to convert point cloud data into 3D models. For instance43, acquired point cloud data using terrestrial laser scanning and constructed information models acquired point cloud data using terrestrial laser scanning and constructed information models using methods including Boolean operations to achieve the conversion from point clouds to 3D models. to achieve the conversion from point clouds to 3D models. Additionally44, proposed a Rhino + Grasshopper - ArchiCAD workflow that transforms point cloud data into 3D models using Delaunay triangulation and texture mapping techniques, embedding the resulting models into BIM. Furthermore45, introduced a multi-level-of-detail parametric modeling framework, automatically converting high-precision point clouds into 3D models using point cloud slicing, contour extraction, and feature-point detection. Moreover46, developed a generative algorithm using the Grasshopper parametric modeling tool to automatically convert point clouds into parametric 3D models. These approaches offer significant gains in efficiency and accuracy when transforming point cloud data into 3D models. It should be noted that they also depend heavily on point cloud quality, require substantial computational resources, and feature limited automation—factors that particularly impede the generation of high-quality models for timber architecture with numerous complex components. Future research should further enhance automation through machine learning techniques while integrating other methodologies to achieve breakthroughs.

Rule-based, machine learning–based, and point cloud-based approaches each present distinct advantages and limitations. The integration of these approaches could offer a promising solution for automated HBIM modeling of traditional timber architecture. Although recent studies on automated HBIM modeling of traditional Chinese timber architecture have improved modeling speed and accuracy to some extent45,47,48,49, they still face four major challenges:

-

(1)

Most parametric applications are limited to individual components—such as dougong—rather than modeling of complete structures.

-

(2)

These methods are typically tailored to specific building instances and cannot address the need for large-scale, generic modeling across large numbers of traditional timber architecture cases.

-

(3)

The majority of parameterization approaches rely on parameter-geometry relationship analysis, which is primarily based on canonical treatises such as Yingzao Fashi and the Qing Engineering Practices Rules and Regulations. These methods are well-suited for timber structures constructed according to traditional architectural norms, but are rendered inapplicable to vernacular timber architecture where parameter-geometry relationships remain uncertain or undocumented.

-

(4)

Parametric approaches predominantly based on mathematical-geometric relationships are unable to record the construction logic and generative processes of traditional timber architecture, making it difficult to document and express such intangible construction techniques.

Although the structures and components of traditional Chinese timber architecture are complex, they possess a discernible and systematic construction logic, which constitutes the core architectural expertise of traditional Chinese timber architecture construction. Therefore, this study combines these three approaches to develop an intelligent HBIM modeling method that integrates architectural expertise with intelligent technologies such as machine vision.

Methods

Architectural expertise is crucial for building an HBIM model of traditional timber architecture. Architects acquire this expertise through specialized architectural research of the construction logic of traditional timber architecture. By mastering this logic, they can analyze and classify construction types and efficiently extract the core data of timber architecture. An experienced architect typically follows these steps to build an HBIM model for traditional timber architecture: First, advanced data acquisition techniques—such as 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry—are employed to capture point cloud data of the timber architecture; next, the architect professionally analyzes the point cloud data according to the building’s construction logic, identifying and classifying its key structural components and extracting core geometric and semantic information; subsequently, based on the construction logic and extracted core data, the architect constructs the spatial-topological framework of the architecture; finally, guided by the construction logic, suitable components are selected from a pre-established HBIM component library, their parameters and associated information are modified, added, or removed as necessary, and they are assembled into the spatial-topological framework to complete the HBIM model of traditional timber architecture.

Traditional methods for point cloud utilization typically involve using related software tools to treat point cloud images as background references, with the modeler manually tracing timber component contours to extract data—a process that is inherently inefficient. Machine learning-based 3D segmentation of building components in point cloud data faces significant challenges due to diverse component typologies, complex spatial morphologies, and variable point cloud quality. Consequently, no universally applicable solution has yet emerged. However, observations of architectural practice reveal that architects can interpret the spatial structures and construction types of timber architecture from 2D drawings, drawing upon their architectural expertise, thereby extracting the core data needed for HBIM modeling. Therefore, by leveraging architectural expertise, the core data required for constructing HBIM models is systematically clarified, enabling the use of 2D image-based machine vision techniques to delegate some tasks that originally relied heavily on the modeler’s expertise to computer-based processing.

To achieve rapid, efficient, and accurate intelligent HBIM modeling, it is essential to integrate architectural expertise with machine vision. This integration better leverages the experiential characteristics of expertise while mitigating the impact of individual variations, ultimately optimizing the efficiency and accuracy of core data identification and acquisition. Therefore, this study proposes a novel methodology that integrates machine vision techniques based on semantic analysis with an architectural expertise-based metamodel, constructing an innovative framework for intelligent HBIM modeling of traditional timber architecture. The approach formalizes architectural expertise in traditional timber architecture modeling into a construction-logic-based metamodel, which provides an adaptive algorithmic framework and defines core data requirements for automated HBIM model generation. Building on this metamodel and the YOLO framework, it further establishes a machine vision-based method for automated identification and acquisition of core data. Collectively, this framework delivers a practical solution for intelligent and automated HBIM modeling of traditional timber architecture (Fig. 1).

From architectural expertise to a construction-logic-based–based metamodel

A metamodel—formally defined as a “model of models”—is a descriptive specification of modeling procedures, model semantics, and integration/interoperability mechanisms. It serves as a standardized definition for a specific domain’s modeling environment, explicitly defining the domain’s syntax and semantics to comprehensively represent all systems within that domain50,51. A metamodel is defined by four elements: meta-objects, meta-attributes, meta-relationships, and meta-methods. The construction methodology involves inductively organizing these modeling components—meta-objects, meta-attributes, and meta-relationships—into a meta-database. Implementation of meta-methods on this foundation establishes the metamodel’s logical framework, resulting in the complete metamodel. A conventional metamodel can be realized as a data-driven parametric model to rapidly and automatically generate Building Information Models for similar buildings by leveraging the metamodel and associated feature data.

The algorithmic logic of the traditional timber architecture metamodel is identical to its construction logic: the algorithmic logic provides the foundational relationships and data for the HBIM. This logic, translated into computational logic algorithms, subsequently generates the HBIM. Because the construction logic of traditional timber architecture constitutes the core expertise for establishing their HBIM, therefore, formalizing this logic into computational logic algorithms is equivalent to formalizing that expertise into a construction-logic-based metamodel. The basic steps for constructing a metamodel of traditional timber architecture (Fig. 2) are as follows:

-

(1)

Extract the construction logic of traditional timber architecture.

-

(2)

Classify components and extract key parameters according to the construction logic to define meta-objects.

-

(3)

Categorize information and define attributes to establish meta-attributes and build the meta-database.

-

(4)

Determine spatial relationships of components based on the construction logic, translate them into mathematical relationships, and define meta-relationships.

-

(5)

Establish the construction sequence, convert the construction logic into algorithmic logic, and formulate meta-methods.

-

(6)

Determine the classification of the metamodel based on the similarities and differences between meta-relationships and meta-methods.

-

(7)

Integrate the meta-database with the logical algorithms using the Dynamo visual programming platform to build the metamodel.

The metamodel for traditional timber architecture provides an adaptive algorithmic framework while specifying core data requirements for automated HBIM generation. Once the metamodel for a traditional timber architecture is established, users need only supply the core data extracted from point cloud images to drive the automatic construction of the HBIM. To enhance the efficiency and accuracy of 2D point cloud image detection and core data acquisition, this study will also explore novel techniques for automating point cloud image detection and core data acquisition.

Application of machine vision techniques

Building on the metamodel, our processing requirements for 2D point cloud images have shifted to focus on component type identification and core data extraction. Machine vision tasks can be categorized into four stages of increasing complexity: classification, localization, detection, and segmentation. Object detection is particularly well-suited to detecting and recognizing building components in point cloud images of timber architecture. Therefore, this study employs machine vision–based object detection to detect and recognize building components in point cloud images. After a systematic review of object detection algorithms, this study employs the well-established YOLO algorithm to train a model capable of detecting and recognizing components in timber architecture point cloud images, annotating them with architectural semantics (Fig. 3), and enabling the intelligent extraction of core data from the detection results. YOLO (You Only Look Once) is a one-stage object detection algorithm that formulates detection as a single regression task, predicting bounding-box coordinates and class probabilities in one pass. Its architecture consists of three main parts: a backbone (e.g., CSPDarknet) for hierarchical feature extraction, a neck (FPN or PAN) for multi-scale feature fusion, and a detection head for bounding-box regression and classification. By eliminating region proposals, YOLO achieves real-time performance while maintaining high accuracy. These characteristics make it particularly well-suited for interpreting point-cloud images and automating the detection of architectural elements in HBIM workflows for traditional timber architectural heritage. The process of training the YOLO-based detection model for timber architecture point cloud images involves the following steps:

-

(1)

Dataset collection and preparation

-

(2)

Setting up the training environment

-

(3)

Hyperparameter tuning

-

(4)

Training and validation

After a point cloud image is processed by the successfully trained point cloud image detection model, key components in the image are identified and enclosed within bounding boxes. The geometric features of components detected by the detection model in point cloud images can be abstracted as idealized circles and rectangles. Thus, the dimensions of a component are equivalent to the width (w) and height (h) of its bounding box, and the distance between components can be derived from the distance between the centers of their respective bounding boxes. To acquire the core data necessary to drive the automated generation of timber architectural HBIM from a metamodel, dedicated scripts should be developed to automatically calculate the center coordinates and dimensions (w, h) of each bounding box, as well as the distances between their centers. Nonetheless, the obtained data values are based on image scale and expressed in pixel units. To obtain accurate real-world measurements, further scale conversion is necessary.

The point cloud processing tool, Trimble, automatically appends a scale bar to the output point cloud images by default. Once the point cloud image detection model successfully detects the scale bar, it computes the number of pixels within the scale bar’s bounding box based on the overall dimensions of the image, and this quantity is represented by the width (w) and height (h) of the bounding box. Once the pixel dimensions of the scale bar’s bounding box and key component bounding boxes are acquired, the conversion relationship between pixel dimensions and real-world dimensions is established based on the scale value derived from the scale bar in the image (Fig. 4). Dedicated scripts are subsequently developed to execute the conversion of all target measurement data from pixel dimensions to real-world dimensions.

Overall Framework

By integrating machine vision techniques with a construction-logic-based metamodel, this study proposes a research framework for intelligent HBIM modeling of traditional timber architectural heritage. Based on this method, after acquiring the 3D point cloud data of a target timber structure for HBIM construction, the modeler processes the data into 2D point cloud images and inputs them into a pre-trained machine vision object detection model. The detection model automatically identifies key components within the images and intelligently extracts core data required to drive the metamodel. The processed data are then fed into the metamodel and drive it to automatically construct the HBIM (Fig. 5).

Results

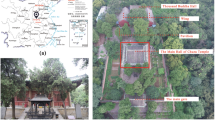

The Dong nationality drum tower, a distinctive architectural typology unique to the Dong ethnic group, is situated in Dong communities at the intersection of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Hunan, and Guizhou provinces in China (Fig. 6). The drum tower exhibits a diverse and intricate structural system. Its construction methodology fundamentally differs from official-style architecture, developing a self-contained and distinctive construction logic (Fig. 7). As a quintessential exemplar of non-modular construction logic distinct from official-style architecture, this structure poses significant challenges for parametric modeling due to the absence of consistent mathematical-geometric relationships. Therefore, the Dong drum tower is chosen as a representative case study for this research.

The non-modular construction logic of the Dong drum tower is prevalent in traditional vernacular timber architecture, primarily evident in its distinctive architectural structure and the “real-scale construction” technique (Fig. 8). “Real-scale construction” comprises two aspects: design and construction. The design process involves a systematic simplification from the three-dimensional framework to the two-dimensional truss framework, and ultimately to the one-dimensional identification system. Conversely, the construction process reverses this sequence, beginning with the one-dimensional identification system, proceeding to the fabrication of vertical components and horizontal component assembly to reconstruct the two-dimensional truss framework, and ultimately completing the three-dimensional framework erection. Therefore, defining the primary truss framework and applying operations such as duplication, rotation, and deformation constitutes the core construction technique for the Dong drum tower, a traditional Chinese pierced-purlin architecture. The “real-scale construction” techniques determine the methods for generating both the structural framework and components in the Dong drum tower.

Extracting the construction logic of the drum tower to develop drum tower metamodels

The metamodels of the Dong drum tower are constructed through the following six main steps: (1) extraction of the drum tower’s construction logic. This process involves abstraction and extraction based on a framework of meta-objects, meta-attributes, meta-relations, and meta-methods. The essential elements to be extracted encompass: component classification, component spatial positioning and identification system, and component assembly sequence; (2) classification of the drum tower metamodels. According to differentiated transformations of the primary bay frame throughout the generative process of the spatial structural system, the metamodels can be categorized into single-bay basic type, double-bay similar type, and variant type; (3) definition of the drum tower metamodel’s system framework. Based on the construction logic of the drum tower, the meta-objects are categorized into the planar column grid system, the major timber truss system, and the roof top part (Fig. 9); (4) extraction of information parameters of timber components and establishment of a timber component library; (5) development of the spatial-topological framework and core logic algorithms for the drum tower metamodels using Dynamo (Fig. 10); and (6) completion of the drum tower metamodels. Within the spatial-topological framework of the metamodels, reference points for components are established using point cloud data, followed by placement of corresponding component family models at these points and association of relevant property parameters, thus completing the establishment of the metamodels (Fig. 11)52. Building on 20 years of architectural research involving nearly 100 drum towers, this study leveraged professional expertise to complete Steps 1–4, subsequently implementing Steps 5–6 within the established research framework.

Training the point cloud image detection model and intelligent extraction of core data

According to the research framework, the next objective is to train an object detection model capable of identifying timber components in both plan and section point cloud images of Dong drum towers and annotating them with corresponding architectural semantic information. Based on the trained model, dedicated computational scripts are developed to intelligently extract the core data required to drive the metamodels for automated HBIM construction.

Dataset collection and preparation

Figure 12 illustrates the main workflow for dataset collection and preparation: (1) compilation of 3D point cloud data from 37 drum towers documented by the research team in prior surveys; (2) slicing processing of 3D point cloud data was performed with Trimble tools, generating point cloud images—mainly ground-floor plans and diagonal sectional views—that meet this object detection task’s requirements for the production of the dataset; (3) data augmentation was executed via zooming, rotation, and panning operations on point cloud images, yielding a dataset consisting of 1041 plan images and 386 section images; (4) the timber components to be identified in the plan and section point cloud images were systematically categorized and annotated using the annotation tool LabelImg; and (5) the image dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 7:2:1. As shown in Table 1, the dataset comprises multiple component categories, but their distribution is imbalanced, with some classes having far more samples than others. This imbalance mainly arises from differences between plan and sectional point cloud images and reflects the natural characteristics of timber heritage data. Nevertheless, each class is sufficiently represented for training, and per-class metrics are reported to ensure fair evaluation. Therefore, the imbalance does not undermine the validity of training or detection performance.

Model training

After the dataset collection and production, the training environment setup was commenced. This study employs YOLOv11 for point cloud image detection model training. The computational environment for model training is configured with Python 3.10.16, PyTorch 2.6.0, and CUDA 12.4. Training was conducted on a platform with an Intel Core i9-13900HX CPU, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU (8 GB GDDR6), 32 GB DDR5 RAM, a 3 TB SSD, a LENOVO LNVNB161216 motherboard, and Windows 11 (24H2). Based on available computational resources and comprehensive comparisons of all YOLOv11 versions, this study employs YOLOv11m as the base network architecture for model training, initialized with the official pre-trained weights (YOLOv11m.pt). The training hyperparameters were uniformly set to: learning rate = 0.01, batch size = 12, epochs = 300, image size = 640 × 640 pixels. Subsequent to hyperparameter configuration, the point cloud detection models for plan and section images were trained in sequential order. To provide a more comprehensive and intuitive illustration of the model training process, Fig. 13 and Fig. 14 present the training performance of the planar and sectional detection models, respectively. These figures depict the trends in box loss, classification loss, and distribution focal loss across both training and validation stages, alongside key evaluation metrics (precision, recall, and mAP). As shown, all loss values decreased steadily and stabilized after approximately 200 epochs, while the precision, recall, and mAP metrics increased correspondingly before converging. This consistent behavior indicates a stable training process with no significant overfitting, confirming the reliability of the trained models for subsequent detection tasks.

Training results and evaluation

According to the formulas for calculating Precision and Recall:

The calculated results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. The planar detection model achieved strong performance (precision 0.969, recall 0.890, mAP0.5 0.945), with major categories such as outer-YZ, inner-ZZ, and scale showing very high values, while smaller categories like outer-GZ and other-GZ had slightly lower recall but maintained good precision, likely due to visual similarity. The sectional model also performed reliably (precision 0.897, recall 0.850, mAP0.5 0.901), with excellent results for inner-ZZ, scale, and LGZ, though some complex classes scored relatively lower due to geometric complexity and class similarity. Overall, both models indicate successful training and effective detection. According to the formula for calculating the F1 Score:

The F1 Scores for the planar and sectional point cloud image detection models were calculated as 0.928 and 0.873, respectively. Upon completion of training, the model was evaluated on the test set to verify its generalization capability and practical performance—specifically its ability to automatically and accurately identify drum tower timber component types. Based on the evaluation metrics and test set results (Fig. 15), model training was deemed successful, demonstrating strong generalization and accurate identification of key timber component types in the drum tower’s 2D point cloud images.

Intelligent extraction of core data

To intelligently acquire the core data required to drive the metamodels for automated HBIM construction, this study develops dedicated computational scripts integrated with the point cloud image detection model. The detailed workflow is as follows:

-

(1)

The nesting of the PaddleOCR model into the point cloud image detection model, with the definition of the ocr_rec function, enables automatic detection and extraction of scale bar values upon detecting scale bars in point cloud images (Table 4);

Table 4 Numerical extraction of scale bar values -

(2)

Based on the bounding boxes and coordinates (xmin, ymin, xmax, ymax) of both the scale bar and individual components identified by the detection model, through the design of the cal_radius function, pixel dimensions (width and height) and center coordinates for each bounding box at the image scale are calculated;

-

(3)

The cal_big_radius function is designed to calculate the geometric inscribed circle radius of a planar column grid by identifying the maximum distance between columns as the inscribed circle’s diameter;

-

(4)

The small_average_mm function is designed to calculate the average dimensions (width and height) for each component category by traversing the dimensions of all component bounding boxes, thereby supporting standardized HBIM modeling;

-

(5)

The pix2mm and small_pix2mm functions are designed to apply the scale values extracted by the PaddleOCR model, based on the method of converting pixel dimensions to real-world dimensions shown in Fig. 4, the real-world dimensions of the timber components and the distances between them can be calculated.

Validation

Figure 16 illustrates the specific operational workflow for the automated construction of the Dong drum tower’s HBIM, based on the HBIM intelligent modeling approach that integrates machine vision techniques based on semantic analysis with an architectural expertise-based metamodel for traditional timber architectural heritage. To evaluate the completeness, accuracy, and modeling efficiency of the automatically constructed drum tower HBIMs generated by the HBIM intelligent modeling approach for traditional timber architectural heritage, we selected one representative drum tower from each of the three metamodel types (single-bay basic type, variant type, and double-bay similar type) to conduct intelligent HBIM modeling validation. We collected 3D point cloud data from the drum tower of Loujing in Xia Ge Township (single-bay basic type), drum tower of Jitang (variant type), and drum tower of Baxi (double-bay similar type), then sliced the data into 2D images for intelligent modeling validation (Fig. 17); the plan and section point cloud images were respectively processed by a trained detection model to identify key timber component types and extract relevant core data. This core data was input into the Dynamo-based drum tower metamodels program to drive automatic HBIM generation. Finally, the intelligently generated drum tower HBIM was cross-validated against its corresponding 3D point cloud model, yielding validation results (Fig. 18). After confirming the feasibility of the proposed intelligent modeling method, we conducted a comparative study by applying both the intelligent modeling method and the traditional manual modeling method to the above three types of drum towers, with ten independent modeling trials performed for each method on each tower (Table 5). The comparison between the two approaches focused on three key evaluation dimensions: modeling accuracy, modeling integrity, and modeling time consumption, with statistical analysis based on mean values and standard deviations. This design enabled a rigorous and quantitative assessment of the relative advantages of the intelligent modeling method over the traditional manual approach.

Discussion

The validation results shown in Fig. 18 and Table 5 lead to the following conclusions:

(1) The intelligent modeling approach automatically generated drum tower HBIM models with approximately 99% completeness and 99% accuracy, demonstrating its capability to produce models of very high integrity and precision. By applying intelligent modeling and validation to representative examples of three different drum tower types, we found that—apart from a few nonstandard components introduced by craftsmen during construction—the automatically generated timber frameworks of the models and detailed features are virtually identical to the original 3D point cloud data. This demonstrates the feasibility of the proposed HBIM intelligent modeling approach for traditional timber architectural heritage, combining machine vision based on semantic analysis with an architectural expertise-based metamodel.

(2) The intelligent modeling approach provides high flexibility in automatic HBIM model generation: it can accommodate different structural system types through the selection of metamodels and enables fine-grained control and modification of timber frameworks by adjusting parameters extracted from point cloud images. The timber architecture model generated through the intelligent modeling approach represents an idealized structure with normalized component dimensions. Consequently, while the overall framework maintains high completeness and accuracy, the spatial positions of certain individual components may deviate slightly from the original 3D point cloud survey data. In these three cases, the maximum deviations of timber components between the HBIM models and their corresponding 3D point cloud models ranged from 7 to 10 cm horizontally to 5–8 cm vertically. The primary causes of deviations include: (1) craftsmen’s inconsistent precision control in design and construction, subject to deviations during the building process; (2) proactive addition of nonstandard structural components by craftsmen based on comprehensive practical factors during construction; and (3) natural degradation including decades of wind and rain exposure, causing timber components to shrink, swell, warp, or undergo structural misalignment. If the modeling objective requires faithful reconstruction of field-recorded data, such deviations can be calibrated in post-processing through point cloud cross-referencing to fine-tune local parameters.

(3) The intelligent modeling approach integrating architectural expertise and machine vision techniques achieves significantly improved efficiency for HBIM modeling of traditional timber architectural heritage. Taking the drum tower as an example, considering the time consumption for both intelligent core data extraction from point cloud images (pre-processing) and model validation/adjustment (post-processing), generating a complete HBIM model of its timber structural framework requires merely around 30 min. Compared to traditional manual modeling approaches, this method achieves at least 15–20 times speed acceleration and approximately 95% higher modeling efficiency, making it exceptionally suitable for achieving efficient modeling using this intelligent approach when handling massive volumes of survey data.

This study proposes an intelligent HBIM modeling method for traditional timber architectural heritage, which significantly improves the efficiency of analyzing and processing point cloud data. By integrating specialized architectural knowledge, it replaces reliance on precise geometric constraints with construction logic based on architectural expertise as the core modeling principle. This modeling method enhances adaptability to the current reality of traditional timber architectural heritage, characterized by large quantities and complex typologies, providing a new solution for data-driven intelligent HBIM modeling of historic architecture.

Traditional timber systems differ in form—Chinese architecture follows bay-based proportional rules, Japanese joinery emphasizes intricate mortise–tenon connections, and European trusses rely on triangular frameworks for stability. Despite such differences, all share reliance on inherited construction rules. The proposed methodology leverages this commonality: its adaptability depends on architectural expertise input rather than fixed rules. By encoding system-specific logic into metamodels and applying machine vision for component detection, it enables automated HBIM modeling across traditions. The key innovation lies not in a tool for one building type, but in a paradigm that transforms architectural knowledge into computable logic, offering an extensible solution for diverse timber heritage. Further research will concentrate on:

-

(1)

Enhancement of point cloud image detection accuracy (e.g., via increased volume of point cloud image data for object detection model training);

-

(2)

Expanding metamodel types applicable to the intelligent modeling approach;

-

(3)

While realizing the preservation and storage of tangible information of traditional timber architectural heritage, it should also simultaneously safeguard the preservation and storage of its intangible information (for example, by combining intangible information such as traditional timber construction techniques with the intelligent modeling approach), and should further explore preservation methods for this intangible information.

Further research will establish foundational support for the conservation and sustainable development of traditional timber architectural heritage.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad, Y. The scope and definitions of heritage: from tangible to intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 12, 292–300 (2006).

Zhang, X., Zhi, Y., Xu, J. & Han, L. Digital protection and utilization of architectural heritage using knowledge visualization. Buildings 12, 1604 (2022).

Bruno, N. & Roncella, R. HBIM for conservation: a new proposal for information modeling. Remote Sens. 11, 1751 (2019).

Dore, C. et al. Structural simulations and conservation analysis-historic building information model (HBIM). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 40, 351–357 (2015).

Lopez, F. J., Lerones, P. M., Llamas, J., Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. & Zalama, E. A framework for using point cloud data of heritage buildings toward geometry modeling in a BIM context: a case study on Santa Maria La Real De Mave Church. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 11, 965–986 (2017).

Murphy, M., McGovern, E. & Pavia, S. Historic Building Information Modelling–Adding intelligence to laser and image based surveys of European classical architecture. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens 76, 89–102 (2013).

Pocobelli, D. P., Boehm, J., Bryan, P., Still, J. & Grau-Bové, J. BIM for heritage science: a review. Herit. Sci. 6, 1–15 (2018).

Murphy, M., McGovern, E. & Pavia, S. Historic building information modelling (HBIM). Struct. Surv. 27, 311–327 (2009).

Lovell, L. J., Davies, R. J. & Hunt, D. V. The application of historic building information modelling (HBIM) to cultural heritage: a review. Heritage 6, 6691–6717 (2023).

Coşgun, N. T., Çügen, H. F. & Selçuk, S. A. A bibliometric analysis on heritage building information modeling (HBIM) tools. ATA Plan. Tasar. Derg. 5, 61–80 (2021).

Megahed, N. A. Towards a theoretical framework for HBIM approach in historic preservation and management. Int. J. Architect. Res. 9, 130 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Comparative analysis of point clouds acquired from a TLS survey and a 3D virtual tour for HBIM development. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 48, 959–968 (2023).

Alshawabkeh, Y. & Baik, A. Integration of photogrammetry and laser scanning for enhancing scan-to-HBIM modeling of Al Ula heritage site. Herit. Sci. 11, 147 (2023).

Costantino, D., Pepe, M. & Restuccia, A. Scan-to-HBIM for conservation and preservation of Cultural Heritage building: The case study of San Nicola in Montedoro church (Italy). Appl. Geomat. 15, 607–621 (2023).

Fidan, Ş, Ulvi, A., Yiğit, A. Y., Hamal, S. N. G. & Yakar, M. Combination of terrestrial laser scanning and unmanned aerial vehicle photogrammetry for heritage building information modeling: a case study of Tarsus St. Paul Church. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 89, 753–760 (2023).

Monchetti, S. et al. Insight on HBIM for conservation of cultural heritage: the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze. Heritage 6, 6949–6964 (2023).

Cuperschmid, A. R. M., Cerávolo, A., Grachet, M. G., Franco Júnior, J. & Fabricio, M. Casa de Vidro: BIM e Gestão do Patrimônio Histórico Arquitetônico. Cad. PROARQ 30, 177–198 (2018).

Silva, F. B., Cuperschmid, A. R., Cerávolo, A. L. & Fabrício, M. A technological prospect for a diagnostic model in HBIM. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 15, 1–24 (2022).

Etxepare, L., Leon, I., Sagarna, M., Lizundia, I. & Uranga, E. J. Advanced intervention protocol in the energy rehabilitation of heritage buildings: a Miñones Barracks case study. Sustainability 12, 6270 (2020).

Oreni, D. et al. Survey turned into HBIM: the restoration and the work involved concerning the Basilica di Collemaggio after the earthquake (L’Aquila). ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2, 267–273 (2014).

Khan, M. S. et al. An integrated hbim framework for the management of heritage buildings. Buildings 12, 964 (2022).

Piselli, C., Guastaveglia, A., Romanelli, J., Cotana, F. & Pisello, A. L. Facility energy management application of HBIM for historical low-carbon communities: Design, modelling and operation control of geothermal energy retrofit in a real Italian case study. Energies 13, 6338 (2020).

Osello, A., Lucibello, G. & Morgagni, F. HBIM and virtual tools: A new chance to preserve architectural heritage. Buildings 8, 12 (2018).

Rocha, J. & Tomé, A. Multidisciplinarity and accessibility in heritage representation in HBIM Casa de Santa Maria (Cascais)—a case study. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 23, e00203 (2021).

Chun, Q., Pan, J. & Dong, Y. Research on integrity damage indexes of the ancient timber frame buildings in the south China. Sci. Conserv. Archaeol. 29, 76–83 (2017).

Santos, D., Sousa, H. S., Cabaleiro, M. & Branco, J. M. Hbim application in historic timber structures: a systematic review. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 17, 1331–1347 (2023).

Koehl, M., Viale, A. & Reeb, S. A historical timber frame model for diagnosis and documentation before building restoration. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2, 201–212 (2013).

Balletti, C., Berto, M., Gottardi, C. & Guerra, F. Ancient structures and new technologies: survey and digital representation of the wooden dome of SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2, 25–30 (2013).

Perria, E., Sieder, M., Hoyer, S. & Krafczyk, C. Survey of the pagoda timber roof in Derneburg Castle. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 42, 509–514 (2017).

Youn, H.-C., Yoon, J.-S. & Ryoo, S.-L. HBIM for the characteristics of Korean traditional wooden architecture: bracket set modelling based on 3D scanning. Buildings 11, 506 (2021).

Quattrini, R., Malinverni, E. S., Clini, P., Nespeca, R. & Orlietti, E. From TLS to HBIM. High quality semantically-aware 3D modeling of complex architecture. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 40, 367–374 (2015).

Sztwiertnia, D., Ochałek, A., Tama, A. & Lewińska, P. HBIM (heritage building information modell) of the Wang stave church in Karpacz–case study. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 15, 713–727 (2021).

Quattrini, R., Sacco, G. L., De Angelis, G. & Battini, C. Knowledge-based modelling for automatizing HBIM objects. The vaulted ceilings of Palazzo Ducale in Urbino. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 48, 1271–1278 (2023).

Capone, M., Palomba, D. & Lanzara, E. Five keystones vaults parametric model generation from point cloud data. Springer Ser. Des. Innov. 23, 271–280 (2022).

Li, S.-L. et al. Rapid modeling of Chinese Huizhou traditional vernacular houses. IEEE Access 5, 20668–20683 (2017).

Liu, J. & Wu, Z.-K. Rule-based generation of ancient chinese architecture from the song dynasty. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 9, 1–22 (2015).

Rodrigues, N., Magalhães, L., Moura, J. & Chalmers, A. Reconstruction and generation of virtual heritage sites. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 1, 92–102 (2014).

Croce, V. et al. From the semantic point cloud to heritage-building information modeling: a semiautomatic approach exploiting machine learning. Remote Sens. 13, 461 (2021).

Roman, O., Avena, M., Farella, E. M., Remondino, F. & Spanò, A. A semi-automated approach to model architectural elements in Scan-to-BIM processes. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 48, 1345–1352 (2023).

Moyano, J., Musicco, A., Nieto-Julián, J. E. & Domínguez-Morales, J. P. Geometric characterization and segmentation of historic buildings using classification algorithms and convolutional networks in HBIM. Autom. Constr. 167, 105728 (2024).

Buldo, M., Agustín-Hernández, L. & Verdoscia, C. Semantic Enrichment of architectural heritage point clouds using artificial intelligence: the Palacio de Sástago in Zaragoza, Spain. Heritage 7, 6938–6965 (2024).

Güneş, M. C., Mertan, A., Sahin, Y. H., Unal, G. & Özkar, M. Semi-automated minimization of brick-mortar segmentation errors in 3D historical wall reconstruction. Autom. Constr. 167, 105693 (2024).

Moyano, J. et al. Bringing BIM to archaeological heritage: Interdisciplinary method/strategy and accuracy applied to a megalithic monument of the Copper Age. J. Cult. Herit. 45, 303–314 (2020).

Andriasyan, M., Moyano, J., Nieto-Julián, J. E. & Antón, D. From point cloud data to building information modelling: an automatic parametric workflow for heritage. Remote Sens 12, 1094 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. A method of automatic extraction of parameters of multi-LoD BIM models for typical components in wooden architectural-heritage structures. Adv. Eng. Inform. 42, 101002 (2019).

Massafra, A., Prati, D., Predari, G. & Gulli, R. Wooden truss analysis, preservation strategies, and digital documentation through parametric 3D modeling and HBIM workflow. Sustainability 12, 4975 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Development and application of an intelligent modeling method for ancient wooden architecture. ISPRS Int J. Geoinf. 9, 167 (2020).

Chen, Y. & del Blanco García, F. L. Análisis constructivo y reconstrucción digital 3D de las ruinas del Antiguo Palacio de Verano de Pekín (Yuanmingyuan): el Pabellón de la Paz Universal (Wanfanganhe). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 13, 1–16 (2022).

Wang, Y., Agkathidis, A. & Crompton, A. Parametrising historical Chinese courtyard-dwellings: an algorithmic design framework for the digital representation of Siheyuan iterations based on traditional design principles. Front. Archit. Res. 9, 751–773 (2020).

Yuan, M., Jie, L. & Bohu, L. Metamodel-based modeling methodology research of complex system. J. Syst. Simul. 14, 411–414 (2002).

Xiqiang, Y., Yan, L., Wenqiang, L., Yan, X. & Yanjian, W. A multidisciplinary information modeling method for complex products based on meta-model. J. Comput. Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 25, 1540–1548 (2013).

Deng, Y., Guo, S. H. & Cai, L. Application of mathematical metamodeling for an automated simulation of the Dong nationality drum tower architectural heritage. Comput. Concr. 28, 605–619 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 24BMZ084) for the project titled “Research on the Tujian System and its Innovative Applications of Dong Nationality’s Timber Architecture Construction Techniques”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. mainly contributed to the development of research ideas, experimental methods and suggestions; Q.L., S.G., and L.C. contributed to the overall experiments, data curation and paper writing. All authors approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This work does not raise any ethical issues. We are grateful for the valuable reviewers’ comments, which helped in revising this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Y., Li, Q., Guo, S. et al. Intelligent Hbim modeling of traditional timber architectural heritage, integrating machine vision and architectural expertise. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 582 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02151-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02151-6