Abstract

Ancient Japanese manuscripts are invaluable cultural assets but are often degraded by stains, fading, and bleed-through. We propose a restoration framework integrating the Diffusion Denoising Restoration Model (DDRM) with a two-stage mask generation process combining Automatic Color Equalization (ACE) and Gaussian Mixture Model clustering across multiple color spaces. A key novelty is the use of binarized text masks as guidance signals for DDRM through noise masking, which constrains denoising to character shapes and suppresses background noise. A high-resolution patch-based strategy with feather blending further enables seamless reconstruction of both text and background. Experiments on synthetic degradations of The Pillow Book and real manuscripts such as Tsurezuregusa demonstrate significant improvements over binarization-based DDRM, with an average PSNR gain of 10 dB, SSIM increase of 0.17, and LPIPS reduction from 0.49 to 0.28. The framework enhances textual clarity, preserves red annotations, and offers a scalable solution for AI-driven cultural heritage preservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

From the earliest symbols carved into stone to satellites orbiting the Earth, human civilization has advanced through the accumulation of records and knowledge. Among the most valuable legacies of this progress are historical documents, which preserve the thoughts and expressions of past societies. In particular, ancient manuscripts have served as crucial vessels for transmitting the language, emotions, and ideas of earlier generations.

Ancient Japanese manuscripts represent highly significant cultural and historical legacies. Their interpretation provides insight into the culture and daily life of the time, while their philosophical and aesthetic values offer new perspectives for the present. For instance, ethical and existential reflections documented in these works resonate with contemporary thought, and their traditional artistic sensibilities inspire modern design and creative practices.

However, centuries of storage have resulted in extensive degradation, including stains, mold, and insect damage, which often obscure the text and further hinder interpretation. Such challenges are not unique to Japan but are shared globally. Examples include ancient inscriptions, Dunhuang murals, and bamboo slips in China, medieval manuscripts in Europe, and cuneiform texts in the Middle East, all of which face similar threats of deterioration and demand restoration.

A distinctive characteristic of Japanese manuscripts lies in their script. They are written in kuzushiji, a cursive style widely used before the modern era. Until the late Edo period (prior to the 19th century), kuzushiji was the standard writing style. Following the Meiji era, standardized print-based scripts were adopted, and modern Japanese came to be composed of hiragana, katakana, and approximately 3000 kanji characters. A unique challenge of kuzushiji is the wide variation in character shapes depending on the manuscript and scribe. For example, Fig. 1 illustrates the characters U+306E, U+306B, and U+3057, each of which appears in significantly different cursive forms across three manuscripts. Since many of these forms differ drastically from contemporary orthography, deciphering them is difficult even for specialists, and only a limited number of scholars are capable of accurate interpretation.

Examples of handwritten character variations for three hiragana letters, U+306E, U+306B, and U+3057, extracted from three historical Japanese manuscripts. Each row corresponds to a different source: “Uso narubeshi” (top), “Teisa Hiroku” (middle), and “Gozen Kashi Hiden sho” (bottom). Each column represents one character, with multiple samples showing stylistic diversity in stroke curvature, proportion, and brush pressure. These examples highlight the significant intra-character variability observed across manuscripts due to differences in calligraphic style, time period, and individual scribes, illustrating the challenges of character recognition and clustering in kuzushiji analysis. All images were derived from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset).

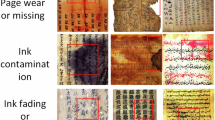

In addition to linguistic challenges, these manuscripts suffer from various forms of physical degradation. As illustrated in Fig. 2, deterioration can be broadly classified into three categories. The first is staining, including background stains blending into the paper (a), stains overlapping characters (b), and large-scale stains covering entire sections of a page (c). The second is character loss caused by fading ink or physical damage, which manifests as partial fading (d) or structural disappearance of characters (e). The third is bleed-through (f), in which ink from the reverse side or adjacent pages becomes visible, interfering with the text and reducing readability. Each of these forms presents substantial challenges for restoration.

Representative examples of various types of degradation observed in a page of an ancient Japanese manuscript. Colored boxes indicate distinct categories of deterioration and their corresponding magnified regions on the right. Red solid boxes a, b, c denote stains, blue solid boxes d, e indicate faded text regions or loss character, and green solid boxes f highlight bleed-through areas where ink has penetrated from the reverse side. Each enlarged patch on the right corresponds to the same color-coded region on the left. These examples illustrate the complexity of mixed degradations-including discoloration, text fading, and bleed-through-that motivate the need for multi-class clustering and mask-guided restoration in the proposed framework. All images were derived from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset).

Conventional restoration has relied heavily on manual techniques, requiring interdisciplinary expertise in kuzushiji transcription, history, and philology. Yet manual approaches remain limited in scalability and efficiency, and the continued progression of degradation raises concerns of irreversible loss.

To address these issues, this study proposes a virtual restoration framework for ancient Japanese manuscripts. The approach incorporates masks automatically generated via color-space clustering as guidance for diffusion-based restoration.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

Introduction of an automatic mask generation method using color-space clustering to distinguish text, background, red annotations, and degraded regions.

-

Quantitative evaluation across multiple degradation levels, demonstrating superior performance over baseline methods in PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS.

-

Validation of the method’s practical utility through application to the historical manuscript Tsurezuregusa, preserving red annotations while enhancing visual clarity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the target manuscripts and reviews conventional and AI-based restoration approaches. Section 3 then describes the proposed diffusion-based restoration framework and presents both quantitative and qualitative evaluations using synthetic and real degradations. Section 4 evaluates the effectiveness and limitations of the proposed method, outlines future directions such as advanced segmentation and tailored evaluation metrics, and concludes by highlighting the academic and cultural significance of AI-driven restoration for digital humanities and cultural heritage preservation.

Methods

Materials

In this study, we targeted two representative classical Japanese manuscripts: The Pillow Book (Makura no Sōshi) and Tsurezuregusa. The Pillow Book, compiled during the Heian period (late 10th to early 11th century), has been well preserved with minimal degradation, making it suitable for controlled simulation experiments. In contrast, Tsurezuregusa, transcribed in the early Keichō era (1596–1615), exhibits prominent natural deterioration, including stains, ink fading, and bleed-through. Moreover, unlike The Pillow Book, Tsurezuregusa contains both black and red text, providing more complex conditions for restoration methods.

High-resolution scanned images of these manuscripts were obtained from the Center for Open Data in the Humanities (CODH), National Institute of Informatics. Images showing bibliographic information or the physical appearance of the manuscripts (e.g., title slips, exterior photographs) were excluded from the analysis and not used in the experiments. Only the main text regions were utilized: from each scanned double-page image, LabelImg (https://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg) was used to crop out individual pages by marking the four corners, producing single-page inputs for restoration (Fig. 3). This procedure enabled clustering and evaluation restricted solely to the textual content of the manuscripts.

Example of the preprocessing step applied to historical manuscripts prior to segmentation and restoration. (Left) Original high-resolution scan of a double-page spread, captured with a color calibration strip for reference. Images were derived from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset). (Right) Cropped single-page images automatically generated using LabelImg by manually annotating the four corner points of each page. This preprocessing step standardizes the input dimensions and ensures consistent alignment across samples, facilitating downstream color correction, clustering, and diffusion-based restoration.

The traditional physical restoration of ancient manuscripts has historically been based on shared principles across different regions. Surface dirt and mold are removed through dry cleaning techniques, such as the use of soft brushes, smoke sponges, and suction devices, or through wet cleaning using purified water or pH-neutral solutions. Creases and cracks in paper or parchment are corrected by controlled humidification to soften the fibers, followed by flattening and tension drying. Missing portions are repaired with paper or parchment infills, while flaking ink or pigments are consolidated with adhesives or thin resin coatings. In all cases, the principle of reversibility is emphasized, ensuring that interventions can be undone in the future. Preventive conservation is also indispensable, including environmental controls such as stable temperature and humidity, protection from light, and measures against insects and pollutants.

Japanese manuscripts exhibit unique features compared to their Western or Middle Eastern counterparts. They are primarily written on washi (Japanese handmade paper) made from mulberry, mitsumata, or gampi fibers, which is thin yet highly durable. Notably, washi has been recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, highlighting its cultural and historical value. Restoration often employs the same type of washi for reinforcement and infill to maintain material consistency. Distinctive binding formats—such as scrolls (makimono), accordion books (orihon), and stitched booklets (sōshi)—require treatments that preserve the original structure. Furthermore, Japanese manuscripts are frequently written in kuzushiji, a cursive script, and may contain annotations in red ink, decorative pigments, or even gold leaf. These characteristics demand special care: for example, aqueous treatments risk ink bleeding, and fragile decorative layers may require consolidation. In terms of preservation, washi is particularly sensitive to humidity, making strict environmental control and protection against acidic gases, light, and insects especially important.

Despite their effectiveness, traditional physical restoration methods face several limitations. First, specialized expertise is required. Each type of deterioration—whether stains, fading, or structural loss—necessitates different treatments, demanding knowledge in material science, chemistry, history, and philology, as well as advanced technical skills. Second, the cost of restoration is substantial. Manual work requires long hours of labor, specialized tools, and costly conservation materials. As the number of manuscripts increases, both human and financial costs escalate significantly. Third, dependence on preservation environments poses an ongoing challenge. Deterioration factors such as fluctuations in temperature and humidity, exposure to light, airborne pollutants, and biological activity can continue to damage manuscripts even after treatment, often necessitating repeated interventions.

In response to these challenges, digitization initiatives have rapidly advanced in recent decades. Digital archiving reduces physical handling of the original materials, thereby preventing further wear, while also ensuring long-term preservation of information. Moreover, digitized manuscripts can be made openly accessible, allowing researchers and the public worldwide to engage with cultural heritage. UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme1 seeks to safeguard documentary heritage and improve accessibility, while European platforms such as Europeana2 and Archives Portal Europe3 provide open access to vast collections of digitized cultural materials. Within this international context, the restoration of Japanese manuscripts can be regarded as part of the broader movement in cultural heritage preservation and digital humanities.

Therefore, while digitization is essential for preservation, it remains insufficient on its own. It can only safeguard and disseminate what is already visible, but it cannot recover text or information that has been obscured or lost. To overcome this limitation, recent research increasingly explores advanced image processing and artificial intelligence, opening new avenues for the virtual restoration of degraded manuscripts.

Methods

Recent efforts to preserve ancient texts have focused on digitizing books and storing them in databases. At the Art Research Center (ARC) of Ritsumeikan University, academic knowledge is digitally archived, facilitating both material preservation and interdisciplinary collaboration between the humanities and information science4. Optical character recognition (OCR) has also been introduced to extract digital text from ancient manuscripts5,6,7.

In recent years, machine learning and deep learning techniques have increasingly been applied to cultural heritage preservation8. These methods have been used in tasks such as manuscript image restoration9,10, classification11,12,13, and digital archiving14,15,16.

However, the complex shapes of kuzushiji characters and various types of degradation-such as stains, insect damage, ink fading, and bleed-through-significantly impair OCR accuracy. These challenges remain key obstacles to effective manuscript restoration and digital preservation.

Conventional manuscript restoration methods can be broadly classified into three categories: mask-based methods, image inpainting, and generative models.

Mask-based approaches focus on extracting textual regions from manuscript images. Among these, binarization techniques are widely used. Local adaptive thresholding methods, including Otsu’s method17, Sauvola18, and Niblack19, are commonly employed to segment text from the background based on contrast20. These techniques are computationally efficient and straightforward to implement. However, they are highly sensitive to uneven backgrounds and degradations such as ink bleed, often resulting in the loss of faint textual information.

To address these limitations, color-space-based mask generation methods have gained increasing attention. For instance, Muhammad Hanif et al.21 proposed a method that converts RGB images into Lab, Luv, and HSV color spaces, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) and Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)-based unsupervised clustering to segment text and degradation. These techniques require no manual annotations and are adaptable to diverse types of deterioration. In addition, advanced digital restoration approaches incorporate multispectral imaging, 3D surface reconstruction, and statistical image processing22,23, further expanding the toolkit available for cultural heritage preservation.

Generative models for manuscript restoration are often categorized into GAN-based inpainting and diffusion-based generation. GAN-based methods generate high-quality outputs through adversarial training between a generator and a discriminator. In manuscript restoration, GANs have been used to remove noise and restore faint or smudged text. For example, Kaneko et al.24 modified the CycleGAN architecture with tailored loss functions to improve the restoration of degraded characters. Other studies have also utilized GANs for text enhancement and background suppression. Nevertheless, GANs can suffer from training instability and mode inconsistency, which may lead to artifacts or content hallucination25,26,27,28.

Diffusion-based methods have emerged as robust generative tools that reconstruct images by reversing a gradual noising process. Notable models include Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM)29 and Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM)30, which have achieved state-of-the-art results in natural image generation and are increasingly explored for manuscript restoration31,32,33,34.

Figure 4 illustrates the restoration framework based on diffusion models. The framework builds upon DDPM and consists of two stages: a forward diffusion process and a reverse denoising process.

Schematic illustration of the denoising diffusion process and the proposed guided restoration framework. (Top) Forward diffusion process, where a clean manuscript image x0 is gradually corrupted with Gaussian noise to obtain xT. (Bottom) Reverse diffusion process, where the model iteratively reconstructs x0 from xT under the guidance of an observed degraded image y. In this framework, y represents the observed measurement or degraded input (e.g., blurred, stained, or incomplete image). By conditioning the reverse process on y, the model reconstructs a clean and faithful restoration of the original manuscript.

In the forward diffusion process (top row), a clean image x0 is progressively perturbed by adding Gaussian noise, producing intermediate states x1, x2, …, xT. As t increases, each xt becomes increasingly noisy, with xT approaching a standard Gaussian distribution.

In the reverse diffusion process (bottom row), a neural network parameterized by θ reconstructs the original image(GT) by iteratively denoising from xT to x0, optionally conditioned on auxiliary information (e.g., a measurement y). This yields a sequence of conditional transitions that refine the sample toward a plausible, clean image.

Denoising Diffusion Restoration Models (DDRM) extend DDPM to linear inverse problems by incorporating a measurement model y = Hx + ϵ, where H is a degradation operator, and ϵ is noise. The probabilistic formulation of the conditional generative process is given as follows:

which factorizes the posterior trajectory into step-wise transitions conditioned on the observation. Intuitively, this equation describes how the model begins from a noisy image xT and gradually restores it step by step, guided by the observation y, much like refining a blurred photo until it becomes clear again.

Results

Overview of the proposed method and contributions

The proposed framework introduces noise masking, where a binarized text mask is used not as a final output but as a guidance signal for DDRM’s reverse diffusion process35,36. While binarization removes stains and discoloration and highlights text regions, in our approach it constrains the denoising updates to follow character-shaped structures, thereby suppressing irrelevant background noise and degradation artifacts.

Formally, let xθ,t denote the network’s prediction of x0 at step t. The masked update is defined as:

where H represents the degradation operator (see Eq. (2)) and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. This ensures that updates are suppressed in degraded regions, while restoration is guided along text contours, enabling natural stroke regeneration.

The effectiveness of noise masking, however, critically depends on the accuracy of the input mask. Conventional binarization methods, which are widely used in manuscript processing, often fail to preserve faint characters and are highly sensitive to luminance variations, leading to the misclassification of heavily stained regions.

To overcome these limitations, we adopt a two-stage mask generation process. First, Automatic Color Equalization (ACE)37 is applied to the input image to normalize the color distribution and reduce biases caused by illumination or aging (Fig. 5). This correction enhances the separability between textual and background regions. Second, feature vectors are constructed by concatenating values from RGB, CIELab, and CIELuv color spaces. After dimensionality reduction via Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is employed in a two-stage clustering scheme. As a result, each image is segmented into four classes: background, black text, red text, and real degradation.

Example showing the impact of color normalization using Automatic Color Equalization (ACE)37. (Left) Original manuscript image cropped from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset) using LabelImg. (Right) The same image after ACE correction, where the color distribution has been normalized and the contrast between text and background has been enhanced. ACE effectively compensates for uneven illumination and discoloration, reduces the yellowish tint, and improves the separability between ink and paper regions.

The clustering proceeds as follows (Fig. 6). In Stage 1, luminance-based features [L,a,b] are used for PCA and GMM clustering, yielding three clusters corresponding to background, black text, and degradation. In Stage 2, only the pixels assigned to the degradation class are further analyzed. Color-focused features [a,b,r,g] are employed, emphasizing chromaticity rather than luminance. A subsequent PCA → GMM(2) step separates this subset into red text and real degradation based on a “redness” index. Through this design, black text, red text, and degradation regions can be clearly distinguished.

Two-stage restoration pipeline integrating color-space clustering and guided diffusion-based restoration. In the first stage (Mask Generation), an ACE-processed manuscript image is clustered via Color Space Clustering (CSC) into three primary classes: background, degradation, and black text. The degradation class is further refined into two subclasses-red text and real degradation-through a secondary CSC step. In the second stage (Guided Diffusion Model), the background and black-text masks are used to guide the DDRM process, while the red-text mask is overlaid to preserve handwritten annotations. This hierarchical mask-guided design enables the restoration model to suppress stains and discoloration while maintaining the structural integrity and color information of the original manuscript. All manuscript images were cropped from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset) using LabelImg.

The resulting masks for black and red text can effectively reduce small-scale noise. However, in the presence of faint or deteriorated strokes, excessive post-processing may cause character fragmentation or rounded edges. For this reason, such operations are treated in a controlled manner, avoiding over-application in order to preserve character fidelity.

The black text mask obtained from this pipeline is used to guide the noise-masking DDRM inference, thereby preserving fine textual details while selectively restoring degraded regions. For manuscripts containing red annotations (e.g., Tsurezuregusa), the red text is excluded from the denoising process. Instead, after DDRM inference, the refined red text mask is applied to the original image to extract red characters, which are then overlaid onto the restored output. This ensures both textual clarity and chromatic fidelity.

Furthermore, the pipeline has been implemented in a batch-processing framework that can handle multiple input images. For each image, the system automatically outputs the color-corrected version, four-class masks, controlled noise-reduced masks, and statistical summaries such as class-wise area ratios. This design enables efficient processing of large-scale manuscript datasets.

Overall, the proposed method offers three main advantages. (1) ACE compensates for uneven illumination and discoloration, improving clustering stability. (2) Noise masking constrains denoising to character regions, balancing stain suppression with the preservation of faint strokes. (3) The exploitation of color information enables the extraction of class-specific masks (e.g., red annotations), supporting color-aware, type-specific restoration. Consequently, the proposed framework enhances visual clarity, structural fidelity, and chromatic authenticity, providing a robust foundation for the digital restoration of ancient manuscripts.

Experimental design

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted a series of experiments using high-resolution scans of classical Japanese manuscripts from the ROIS-DS Center for Open Data in the Humanities (CODH) (https://codh.rois.ac.jp/). These clean images served as ground truth for synthetic degradation.

The restoration model is based on DDRM (Diffusion Denoising Restoration Model) and was trained on 4829 pages from a humanities-focused manuscript dataset. All images were resized to 128 × 128 pixels for training due to hardware constraints.

We used a 3-channel U-Net architecture with 64 feature channels per layer and four residual blocks. To enhance structural understanding, Self-Attention layers were added at spatial resolutions of 16 and 8. Class-conditional training was introduced using manuscript-specific labels to account for class-wise degradation patterns. The model was trained using mean squared error (MSE) loss with a linear beta schedule over 1000 diffusion steps.

Restoration performance was evaluated using standard metrics such as PSNR38, SSIM39, and LPIPS40 (AlexNet-based), and we also measured the change in pixel count within the degradation mask (generated via GMM clustering) to assess noise removal effectiveness. Similar to recent ML-based heritage restoration studies41,42, we also considered evaluation perspectives that account for input variability and perceptual quality using SSIM-based analysis.

We compared our method against two baselines: (1) CycleGAN and (2) DDRM guided by a binarization mask generated via Otsu’s method-a widely used technique that minimizes intra-class variance in grayscale histograms. CycleGAN takes as input a downsampled image generated in the linear RGB space using the LANCZOS resampling algorithm. The restored image is then upsampled using bicubic interpolation, after which high-frequency components extracted from the original high-resolution image are added to enhance fine details. Given its simplicity and longstanding use in manuscript image processing, Otsu’s method provides a robust benchmark for evaluation.

For simulation-based evaluation, we used The Pillow Book, a Heian-era manuscript well-preserved and minimally degraded, making it ideal for controlled experiments. A total of 745 pages were annotated using LabelImg to isolate manuscript regions for clustering and evaluation (Fig. 3).

Synthetic degradation was introduced using NVlabs’ ocrodeg library (https://github.com/NVlabs/ocrodeg) algorithm from the InstructIR framework, mimicking real-world artifacts such as stains, smears, and mold. Degradation severity was divided into four levels for detailed comparison (Fig. 7).

Illustration of pseudo-degradation applied to a clean manuscript image for quantitative evaluation. (Left) Original clean page cropped from high-resolution scans of the Tsurezuregusa manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset) using LabelImg. (Right) Degraded image generated by the pseudo-degradation pipeline with stain intensity parameter set to 1.0. The simulated stains (highlighted in red boxes) reproduce realistic patterns of discoloration and surface contamination, enabling controlled evaluation of restoration performance under severe degradation conditions.

Color-space clustering segmented each image into three classes: background, black text and pseudo-degradation. The black text masks were extracted and applied to clean manuscript pages to create degraded inputs for restoration (Fig. 6).

In DDRM inference, images were resized to 1024 × 1024, and the number of reverse diffusion steps was reduced from 1000 to 20 for efficiency. The reverse process was guided by a conditional degradation mask with the guidance strength parameter η set to 0.5. The diffusion process employed a linear beta schedule with βstart = 0.0001, βend = 0.02, and 1000 total timesteps.

The detailed procedure for generating synthetic stains is summarized in the following pseudocode.

Algorithm 1

Pseudocode of the pseudo-degradation image generation pipeline

Application to real historical manuscripts

To assess real-world applicability, we applied our method to Tsurezuregusa, a classical manuscript written in the early Keichō era, which exhibits natural degradation such as stains, ink fading, and bleed-through. Unlike The Pillow Book, this manuscript contains both black and red text.

Color-space clustering was applied to produce four masks, including one for red text. The black text mask was used as conditional input to DDRM. To ensure visual consistency across pages with varying background textures, we replaced the backgrounds with a standardized texture extracted from The Pillow Book.

Following restoration, the red text mask was overlaid onto the restored image, achieving both textual clarity and color fidelity-an outcome that is difficult to obtain with traditional binarization-based methods.

Output and analysis of results

To assess the restoration performance, we applied synthetic stains to manuscript images at four intensity levels (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0) and compared the proposed clustering-based masking method with a binarization-based baseline (Fig. 8). In addition, we conducted a statistical evaluation at a representative intensity level using three metrics-PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS-reporting the minimum, maximum, average, and variance (Table 1).

Visualization and quantitative comparison of restoration performance under different levels of synthetic stain intensity using the The Pillow Book dataset. Pseudo-degraded manuscript images were generated by the proposed pipeline with increasing stain intensity (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0). The results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently achieves higher PSNR and SSIM values, and lower LPIPS scores than CycleGAN and the binarization-based DDRM, indicating superior restoration fidelity across all degradation levels. All input images were cropped from high-resolution scans of the The Pillow Book manuscript (National Institute of Japanese Literature, CODH dataset) using LabelImg.

Figure 9 presents qualitative results at the highest stain intensity (1.0), illustrating the superior restoration performance of the proposed method over the baseline.

Each row shows different samples from the dataset. The first column displays the clean reference image, the second shows the restoration by CycleGAN, the third presents results from DDRM guided by binarized images, and the fourth shows outputs generated by our proposed mask-guided DDRM. Red boxes highlight enlarged regions for detailed visual comparison, demonstrating that our method effectively restores fine character structures and suppresses background artifacts.

Across all stain intensity levels, the proposed method consistently outperformed the binarization-based DDRM (DDRM(Bin)) in both PSNR and SSIM, demonstrating improvements in visual quality and structural fidelity. Compared with DDRM(Bin), PSNR increased by approximately 10 dB, indicating a substantial enhancement in restoration quality. SSIM also improved by about 0.17, confirming superior preservation of structural details.

Compared with CycleGAN, the proposed method achieved an improvement of approximately 2 dB in PSNR and 0.09 in SSIM, indicating better structure-preserving capability than other models as well.

LPIPS scores were generally lower for the proposed method, reflecting higher perceptual quality. Overall, these results demonstrate the superior accuracy and robustness of the proposed approach across all evaluation metrics.

At the representative stain intensity level (Table 2), the proposed method achieved a maximum PSNR of 27.6 and an average of 24.83, markedly outperforming DDRM(Bin) (maximum 18.34, average 13.86) and surpassing CycleGAN in both maximum and average values. Similarly, SSIM values were higher with reduced variance, indicating greater stability and consistency.

Regarding LPIPS, the proposed method achieved a minimum score of 0.2498, lower than DDRM(Bin)’s 0.3711, indicating better perceptual similarity. It also achieved an average LPIPS of 0.2789 with a small variance of 0.0003, confirming both high perceptual fidelity and robustness in restoration.

At the representative stain level (intensity), the proposed method achieved a maximum PSNR of 27.6 and an average of 24.83, significantly outperforming the baseline (maximum 18.34, average 13.86). SSIM also showed higher maximum and average values with reduced variance, indicating greater stability and consistency. Regarding LPIPS, the proposed method achieved a minimum score of 0.2498-lower than the baseline value of 0.3711-indicating superior perceptual similarity. The method also yielded an average LPIPS of 0.2789 and a variance of 0.0003, demonstrating both high perceptual quality and robustness.

We applied our restoration framework to real historical images of Tsurezuregusa, which exhibit natural degradation such as stains, faded ink, bleed-through, and red text. Figure 10 provides a visual comparison of the original degraded input, the output of CycleGAN, DDRM guided by Otsu binarization, and the result of our proposed method.

Each row presents different pages from the original Tsurezuregusa dataset. The first column displays the degraded original manuscripts, the second shows results restored by CycleGAN, the third presents DDRM guided by binarized images, and the fourth shows outputs from our proposed mask-guided DDRM. Red boxes indicate enlarged regions for detailed visual comparison. Our method successfully recovers fine textual details while suppressing real degradation, such as stains and fading, demonstrating strong generalization from synthetic to real-world deterioration.

As shown across all rows in Fig. 10, the proposed method successfully preserves red annotations using an overlay-based strategy, unlike Otsu binarization, which removes all color information. Given that red ink often conveys editorial or semantic significance, preserving these annotations is important for historical integrity. Thus, our method enhances not only readability but also the scholarly utility of the manuscripts.

In the middle row of Fig. 10, background stains and smudges are effectively suppressed using a fixed reference background texture, resulting in visually clean and consistent outputs suitable for digital archiving. However, bleed-through artifacts-caused by ink from the reverse side of the page, remain more prominent than in the binarization result. This indicates a limitation in the current segmentation strategy for handling semi-transparent noise.

In the bottom row, the method preserves partially faded characters by maintaining essential stroke features. Additionally, lightly written marginalia-often excluded in conventional restoration-are restored, contributing to a more complete reproduction of the manuscript.

However, we also observed the emergence of new artifacts near the top of the page, where the model introduced worm-eaten-like patterns not present in the original. This appears to result from an interaction between the original texture and interpolation during the restoration process. Mitigating such artifacts remains a direction for future improvement.

To address the limitations of page-wise restoration, we further introduce a high-resolution patch-based strategy. Since diffusion models are typically trained on relatively small inputs (e.g., 128 × 128 pixels), directly processing full manuscript pages, which often exceed several thousand pixels in each dimension, leads to memory overflow and degradation in restoration quality.

Although the model was trained on 128 × 128-pixel patches due to hardware constraints, inference on larger 1024 × 1024 images remains feasible because the DDRM’s U-Net backbone is a fully convolutional network (FCN). In such architectures, convolutional kernels and upsampling layers are applied locally and uniformly across spatial dimensions, allowing the model to operate independently of input resolution. Moreover, the diffusion process itself is pixel-wise probabilistic and thus not directly constrained by image size. The incorporated self-attention layers-operating at spatial resolutions of 16 and 8-further contribute to scalable contextual modeling across multiple spatial levels. However, when directly applied to large pages, minor inconsistencies such as texture roughness or local discontinuities may occur, as the model was not explicitly trained on large-scale spatial dependencies.

To mitigate these limitations, our approach divides large manuscript images into overlapping patches of 128 × 128 pixels, each of which is independently restored using a diffusion model. To avoid visible seams at patch boundaries, we employ feather blending, where patch contributions are weighted by Gaussian masks that assign higher importance to central regions and gradually diminish toward edges. Moreover, text regions are emphasized by increasing their blending weights, ensuring faithful recovery of strokes.

In addition to text restoration, the high-resolution strategy also enhances the clarity of the background texture, enabling a more faithful reproduction of both characters and page surfaces. As shown in Fig. 11, the patch-based approach achieves sharper strokes, recovers faint characters, and yields smoother background reconstruction compared to page-wise restoration.

The patch-based approach enables detailed reconstruction by processing overlapping image patches, thereby preserving fine brushstroke structures and reviving faint or partially missing characters. Additionally, it reproduces the background texture with higher clarity, resulting in a sharper and more natural restoration of both text and manuscript background.

Red annotations, which often hold historical significance, are automatically detected and preserved from the original input to avoid undesired alteration. In addition, the system supports resumption from intermediate states, allowing efficient large-scale processing of manuscript collections.

Overall, this high-resolution patch-based restoration achieves three advantages over page-wise inference: (i) improved quality through alignment with training resolution, (ii) reduced memory consumption, and (iii) seamless reconstruction without boundary artifacts. As a result, the proposed framework enables large-scale, high-fidelity restoration of historical manuscripts, thereby enhancing their readability and scholarly value.

Discussion

This section discusses the objectives of the study, the extent to which they were achieved, the limitations of the proposed framework, directions for future work, and broader implications.

The primary aim of this study is to establish a restoration framework for ancient Japanese manuscripts that integrates color-space clustering with a pre-trained diffusion model. Traditional binarization methods often fail to retain faint strokes and inevitably discard valuable chromatic information, such as red annotations. This study addresses these shortcomings by combining color-space segmentation and guided diffusion.

Experimental results have confirmed that the proposed approach consistently outperforms conventional methods, achieving more than a 10 dB improvement in PSNR across all stain intensities. While this indicates improved structural fidelity and reduced pixel-level errors, its significance extends beyond numerical gains. By leveraging color-space distributions, the framework recovers characters that would otherwise vanish under threshold-based binarization. Crucially, the preservation of red annotations provides philological value for textual criticism, while the retention of faint strokes enhances readability for scholars.

At the same time, Several limitations remain. First, the suppression of bleed-through is still insufficient, reflecting a fundamental challenge in distinguishing semi-transparent ink from foreground text during clustering. The term semi-transparent ink refers to the ink that has partially soaked through the thin paper from the reverse side, making it faintly visible on the front. Because the ink is not completely opaque, it appears as a faint shadow on the surface, making it difficult for the algorithm to determine whether it belongs to the front or the back of the manuscript.

Furthermore, in areas where red and black text are close together, mask ambiguity can occur, leading to fragmented or misclassified strokes. We also considered integrating GMM with CNN-based segmentation methods. However, when GMM-generated masks are used as training data, the noise and misclassifications in those masks tend to propagate through the learning process, resulting in unstable classification performance. In degraded historical manuscripts, GMM alone cannot perfectly separate classes, and using its results as supervision may lead to accumulated errors. Moreover, creating high-quality annotated data manually would require considerable time and effort, making it impractical from a resource standpoint.

In addition, transformer-based models generally require large-scale training datasets, which are unavailable in our limited manuscript collection, potentially restricting their effectiveness.

When performing inference on high-resolution full-page images, local discontinuities such as visible seams or inconsistent textures at patch boundaries were sometimes observed. Slight differences in lighting and paper texture between pages also caused variations in color reproduction. These issues likely result from the model’s focus on local information, suggesting insufficient global structural understanding.

Moreover, clustering methods that rely solely on color-space features cannot fully account for physical factors such as the material properties of writing tools or the aging of inks. Addressing these limitations will require context-aware and multimodal segmentation approaches, such as integrating deep learning with spectral information and regional context to achieve more physically accurate restoration.

Future research should explore hybrid segmentation strategies combining deep learning, adaptive clustering, and human-in-the-loop corrections. Incorporating refinement modules-such as DDPM-based enhancement or user-guided feedback, could further improve perceptual quality. Moreover, developing evaluation metrics tailored to historical manuscripts, including readability-based criteria and OCR integration, would enable fairer and more practical assessments.

Another promising direction is the creation of benchmark datasets based on manual annotations of real degraded manuscripts. Such annotations would, in principle, enable more objective comparisons. However, since degradation patterns are inherently non-uniform and boundaries are often ambiguous, comprehensive annotation was impractical within the scope of the present study. As a more feasible alternative, partial annotations in limited regions or expert-assisted labeling could be employed to establish small-scale gold standards. In addition, conducting user studies with historians and calligraphy experts would provide human-centered evaluation of fidelity and readability, complementing quantitative metrics and bridging the gap between algorithmic performance and scholarly usability.

Taken together, this study extends beyond mere performance improvement. It redefines the role of AI in the preservation and interpretation of historical texts. Academically, it demonstrates a novel integration of diffusion models within digital humanities. Practically, it reduces the workload of experts and enables scalable processing of manuscript collections. Societally, it safeguards both textual and chromatic information, contributing to long-term cultural heritage preservation and promoting open accessibility. These implications align with global initiatives in heritage science and emphasize the cultural significance of AI-driven restoration.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary materials.The datasets used for training and evaluation, including Tsurezuregusa and The Pillow Book, were obtained from the ROIS-DS Center for Open Data in the Humanities (CODH) database.

Code availability

The custom code developed for data processing, color-space clustering, and DDRM-based restoration is not publicly available due to ongoing research and institutional restrictions. However, it can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request for academic research and verification purposes.

References

UNESCO. Memory of the World Programme. https://www.unesco.org/en/memory-world (2025).

Europeana Foundation. Europeana Collections. https://www.europeana.eu/en (2025).

Archives Portal Europe. Archives Portal Europe. https://www.archivesportaleurope.net (2025).

Akama, R. Digitization of classical Japanese books by Ritsumeikan University Art Research Center: On the ARC international model. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 65, 181–186 (2015).

Clanuwat, T., Lamb, A. & Kitamoto, A. End-to-end pre-modern Japanese character (Kuzushiji) spotting with deep learning. In Proc. IPSJ SIG Computers and the Humanities Symposium, 15–20 (Information Processing Society of Japan, 2018).

Clanuwat, T., Lamb, A. & Kitamoto, A. KuroNet: Pre-modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning. In Proc.15th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR,19) 607–614, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2019.00104 (IEEE, 2019).

Lamb, A., Clanuwat, T. & Kitamoto, A. KuroNet: regularized residual U-Nets for end-to-end Kuzushiji character recognition. SN Comput. Sci. 1, 177 (2020).

Fiorucci, M. et al. Machine learning for cultural heritage: a survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 133, 102–108 (2020).

Karadag, I. Machine learning for conservation of architectural heritage. Open House Int. 48, 23–37 (2023).

Stoean, R., Bacanin, N., Stoean, C. & Ionescu, L. Bridging the past and present: AI-driven 3D restoration of degraded artefacts for museum digital display. J. Cult. Herit. 69, 18–26 (2024).

Janković, R. Machine learning models for cultural heritage image classification: comparison based on attribute selection. Information 11, 12 (2019).

Cosovic, M., Jankovic, R. & Ramic-Brkic, B. Cultural heritage image classification. In Proc. Data Analytics for Cultural Heritage: Current Trends and Concepts 25–45 (Springer, 2020).

Grilli, E. & Remondino, F. Classification of 3D digital heritage. Remote Sens. 11, 847 (2019).

Belhi, A., Foufou, S., Bouras, A. & Sadka, A. H. Digitization and preservation of cultural heritage products. In Proc. IFIP Int. Conf. Product Lifecycle Management 241–253 (Springer, 2017).

Buragohain, D., Meng, Y., Deng, C., Li, Q. & Chaudhary, S. Digitalizing cultural heritage through metaverse applications: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Herit. Sci. 12, 295 (2024).

Tai, N. Digital archiving of the spatial experience of cultural heritage sites with ancient lighting. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 16, 45 (2023).

Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 9, 62–66 (1979).

Sauvola, J. & Pietikäinen, M. Adaptive document image binarization. Pattern Recognit. 33, 225–236 (2000).

Jain, A. K. Fundamentals of Digital Image Processing (Prentice-Hall, 1989).

Yang, Z. et al. Summary of document image binarization Preprints 1, https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202401.1534.v1 (2024).

Hanif, M., Tonazzini, A., Hussain, S. F., Khalil, A. & Habib, U. Restoration and content analysis of ancient manuscripts via color space based segmentation. PLoS ONE 18, 1–14 (2023).

Bianco, G. et al. A framework for virtual restoration of ancient documents by combination of multispectral and 3D imaging. In Proc. Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference 1–7 (DBLP, 2010).

Munoz-Pandiella, I., Andujar, C., Cayuela, B., Pueyo, X. & Bosch, C. Automated digital color restitution of mural paintings using minimal art historian input. In Proc. Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage 316–325 (Computers & Graphics, 2023).

Kaneko, H., Ishibashi, R. & Meng, L. Deteriorated characters restoration for early Japanese books using enhanced CycleGAN. Heritage 6, 4345–4361 (2023).

Wenjun, Z., Benpeng, S., Ruiqi, F., Xihua, P. & Shanxiong, C. EA-GAN: restoration of text in ancient Chinese books based on an example attention generative adversarial network. Herit. Sci. 11, 882 (2023).

Chen, S., Yang, Y., Liu, X. & Zhu, S. Dual discriminator GAN: restoring ancient Yi characters. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 21, 66 (2022).

Yalin, M., Li, L., Yichun, J. & Li, G. Research on denoising method of Chinese ancient character image based on Chinese character writing standard model. Sci. Rep. 12, 19795 (2022).

Sun, G., Zheng, Z. & Zhang, M. End-to-end rubbing restoration using generative adversarial networks. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.03743 (2022).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 6840–6851 (NeurIPS, 2020).

Song, J., Meng, C. & Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. In Proc. 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021).

Li, H. et al. Towards automated Chinese ancient character restoration: a diffusion-based method with a new dataset. In Proc. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-Sixth Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Fourteenth Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, 342–351 (AAAI Press, 2024).

Chen, Y., Zhang, A., Gao, F. & Guo, J. Ancient mural super-resolution reconstruction based on conditional diffusion model for enhanced visual information. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 205 (2025).

Wang, Y., Xiao, M., Hu, Y., Yan, J. & Zhu, Z. Research on restoration of murals based on diffusion model and transformer. Comput. Mater. Continua 80, 4433–4449 (2024).

Zhao, F., Ren, H., Su, Z., Zhu, X. & Zhang, C. Diffusion-based heterogeneous network for ancient mural restoration. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 206 (2025).

Kaneko, H., Yoshizu, Y., Ishibashi, R., Meng, L. & Deng, M. An attempt at zero-shot ancient documents restoration based on diffusion models. In Proc. 2023 International Conference on Advanced Mechatronic Systems (ICAMechS) 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Yoshizu, Y., Kaneko, H., Ishibashi, R., Meng, L. & Deng, M. Two-stage stains reduction with diffusion models for ancient Japanese manuscripts. In Proc. 2024 International Conference on Cyber-Physical Social Intelligence (ICCSI) 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Rizzi, A., Gatta, C. & Marini, D. A new algorithm for unsupervised global and local color correction. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 24, 1663–1677 (2003).

Huynh-Thu, Q. & Ghanbari, M. Scope of validity of PSNR in image/video quality assessment. Electron. Lett. 44, 800–801 (2008).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Zhang, R., Isola, P., Efros, A. A., Shechtman, E. & Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 586–595 (IEEE, 2018).

Güzelci, O. Z., Alaçam, S., Bekiroğlu, B. & Karadag, I. A machine learning-based prediction model for architectural heritage: The case of domed Sinan mosques. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 35, e00370 (2024).

Güzelci, O. Z. A machine learning-based model to predict the cap geometry of Anatolian Seljuk Kümbets. Period. Polytech. Archit. 53, 207–219 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding. The work was conducted under the supervision of Prof. Meng. The authors also acknowledge the ROIS-DS Center for Open Data in the Humanities for providing high-resolution manuscript datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. conceived the study, conducted the experiments, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. H.K. and R.I. provided technical advice on image processing methods. L.M. supervised the overall research and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshizu, Y., Kaneko, H., Ishibashi, R. et al. Restoration of ancient Japanese manuscripts via the diffusion denoising restoration model and color space-based masking. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02214-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02214-8