Abstract

Background

Studies investigating the health effects of long-term exposure to air pollution generally rely on the outdoor air pollution exposure assigned at the residential address. By ignoring time activity, population exposure misclassification could potentially lead to loss of precision or bias in epidemiological studies.

Objective

We aimed to assess how residential-based air pollution exposures compared with “real” tracking-based exposures.

Methods

We conducted two tracking campaigns in Switzerland (CH) and the Netherlands (NL) with 686 participants followed for 2 weeks with GPS trackers whilst keeping time activity diaries. In addition, we simulated mobility and commuting tracks for the same subjects using agent-based modeling (ABM) with information from census and travel survey data to estimate mobility-integrated air pollution exposures. Exposures were calculated by overlaying residential address, measured (GPS) and modeled (ABM) tracks with annual average hourly NO2 and PM2.5 concentration surfaces.

Results

We found strong agreements between residential and tracking-based exposures in CH for both pollutants (R2 > 0.76) and NL for NO2 (R2 = 0.79), and weaker agreement in NL for PM2.5 (R2 = 0.56). Similarly, the agreement between ABM and tracking-based exposures was strong for NO2 (R2 > 0.77 in CH and NL), while for PM2.5 it was stronger in CH (R2 = 0.80) than in NL (R2 = 0.54). The highest correlations were between residential and ABM exposures (R2 > 0.96 for both pollutants). Using information commonly available even in large administrative cohorts, we found that exposures derived from the tracking campaigns agreed well with ABM in our two study areas.

Significance

Our study supports the use of residential exposures in epidemiological studies on long-term health effects of air pollution, whilst acknowledging that ABM, especially if the work location is known, can be a useful tool to estimate mobility-integrated exposures.

Impact statement

-

Our research supports the use of residential exposures in studies investigating the long-term health effects of air pollution, whilst acknowledging that agent-based modeling, especially if the work location is known, is valuable for estimating mobility-integrated exposures. Our findings are broadly applicable to air pollution epidemiology, in particular, studies of large populations that rely on exposure modeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution has been associated with various adverse health effects, including mortality.[1] A recent WHO report reported an estimated 4 million deaths annually due to long-term ambient air pollution globally [2,3,4]. In the Global Burden of Disease assessments, air pollution ranks as the most influential environmental exposure [5]. The evidence for these burden of disease assessments was primarily derived from epidemiological studies, especially on long-term air pollution exposure. A Panel appointed by HEI recently reviewed epidemiological studies of traffic-related air pollution (TRAP), addressing exposure assessment issues in detail [6,7,8]. The Panel primarily assessed how well specific methods assessed the outdoor concentration of TRAP, considering the spatial alignment of outdoor exposure as assigned to the residential address, for example, by assessing the spatial resolution of the address and exposure surfaces. Virtually all studies assigned outdoor concentrations to the residential address only [6, 7].

Studies investigating the associations between air pollution and health have shown that real personal exposure depends on the time spent in specific micro-environments [9, 10]. These real personal exposures to air pollution can be assessed directly, for example, by personal monitoring, or indirectly by combining time activity data with concentrations measured or estimated in important micro-environments[9]. Direct or indirect assessment of personal exposures is typically not used in large epidemiological studies. Direct assessment is too costly and logistically challenging due to the large numbers necessary to detect the effect of long-term air pollution on health. It is also not feasible to carry out indirect assessment because large studies, including studies using administrative databases [11, 12], only have information on the people’s home address and typically do not collect time activity data. There are some studies, including the Dutch PIAMA birth cohort and the Swiss SAPALDIA studies, set up specifically to investigate the health effects of air pollution, where information on the work and school addresses had been collected [13, 14].

Epidemiological studies on air pollution and other environmental exposures have been criticized for not taking into account time-activity patterns [15, 16]. Whilst it is understandable that epidemiological studies have relied on the residential address, the question remains as to how well exposure is assessed by focusing on the residential address only.

A comprehensive review of studies comparing residential-based air pollution exposures with time-activity integrated air pollution exposures showed that residential address-based air pollution exposure and mobility-integrated exposure were mostly highly correlated, but the number of studies is still limited [17]. Furthermore, studies used different methods to assess mobility-integrated exposure, and agreement differed somewhat, related to commuting patterns in the population. The few studies that have assessed time activity patterns and related mobility-integrated air pollution exposures are typically either empirical tracking studies in selected and often small study populations [18,19,20] or Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) studies that can be applied to larger populations based on time survey data [21, 22].

In this paper, we apply both approaches (GPS tracking and ABM) to investigate whether more sophisticated estimates of individual air pollution exposure, considering population mobility, are different from estimates based on the residential address location only. To achieve this, we use data collected in two purpose-designed tracking campaigns conducted in Switzerland (CH) and the Netherlands (NL), as part of the “Accounting for MOBility in AIR pollution exposure estimates in studies on long-term health effects” (MOBI-AIR) study. To assess the robustness of the findings, we performed the study in two countries with different commuting patterns. We captured mobility data of almost 700 participants using GPS trackers and time-activity diaries. In addition, we simulated mobility and commuting tracks for the same sample in both countries using ABM. The measured and modeled time-activity data were combined with detailed spatial-temporal air pollution data to enable calculation of residential, mobility integrated (using ABM) and tracking-based NO2 and PM2.5 exposure estimates for the individuals. These resulting exposures were then compared.

Materials and methods

Tracking campaign

We conducted tracking campaigns during 2022/23 in the region of Basel (cantons of Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft), Switzerland and across the Netherlands (mainly in the province of Utrecht), including 489 Swiss and 189 Dutch participants, collecting detailed information on their mobility patterns over a 2-week period using a purposely designed mobile phone study app and a GPS tracker [23]. The tracking campaigns included a baseline questionnaire and a time activity diary (TAD). The existing population-based COVCO-Basel cohort [24] was used for embedding this study and for recruitment in the Basel region (Switzerland), achieving a total of 489 participants (recruitment rate of 33% from the total of 1475 people invited by email). In the Netherlands, we used a combination of random sampling from the whole Dutch population and a more targeted approach, distributing leaflets around Utrecht, adding a 25 Euro voucher as an incentive, reaching a total of 189 participants.

Participants were asked to download the study app, in which they filled in a daily TAD during the 2 weeks of the tracking campaign. The study app also collected their location information every 3–4 min via the mobile phone integrated GPS. In addition, we asked the participants to carry a high-precision GPS tracker (location time stamp every 20 s) specifically developed for the study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Location points from the study app and the GPS tracker were combined and linked to both the corresponding TAD information and air pollution concentrations extracted from long-term hourly weekdays and weekends air pollution raster files (see Section “Exposure estimates”).

In the baseline questionnaire, participants were asked for details on the environment around their home, neighborhood, commuting behaviors, general health status, and sociodemographic aspects. Employed participants were asked to provide their work address information to assess the accuracy of the ABM analysis.

ABM

The ABM applied in this study has been described in detail elsewhere [25, 26] following the approach of Lu and Schmitz [21]. Depending on the profile of an individual (i.e., agent), an activity diary was created, which, starting from the home location, simulated activities such as commuting, work, shopping, and recreation, including the time spent at these locations and activities. Based on the Euclidean distance between the home and simulated work locations, the commuting mode (i.e., walk, bike, car, and public transport) was randomly determined, and the shortest route was subsequently calculated across the transport network. For each agent, a Monte Carlo simulation was applied to calculate 50 realizations, meaning that 50 random work locations were identified per agent, leading to 50 corresponding routes. The locations and routes were overlaid with hourly air pollution data, with different diurnal patterns for weekdays and weekends reflecting traffic flows, to calculate aggregated air pollution exposures. For each agent, the mean and standard deviation of air pollution concentrations of the 50 realizations were calculated. A simulation was performed comparing the mean of the distribution of the 50 ABM realizations vs. an assignment of a single random realization. Finally, for the subgroup of participants with known work address information provided in the baseline questionnaire in Switzerland and the Netherlands, we also performed ABM modeling, taking the work location into account.

Three main profiles were created for the agents: a residential, a homemaker and a commuter profile. The residential profile assumed the same activity during weekdays and weekend days for 24 h at the residential address location. The homemaker represented the non-working population with three sub-profiles simulating activities in an increasing activity space (1, 5 and 10 km buffer around residential address), with the same activity pattern during weekdays and weekend days. Lastly, the commuter profile consisted of 9 sub-categories (all, male, female, male (low, middle, high SES) and female (low, middle, high SES)). Commuting patterns for the different commuter profiles were based on the country-specific origin-destination matrices. In the Netherlands, we obtained data from the National Travel Surveys from Statistics Netherlands [27] covering the years 2011–2019. These annual surveys provide information on the daily mobility behavior of a sample of 40,000 randomly selected Dutch households. For each household, the survey asked details for one specific day, about the number of trips, geographical location and times of start and end for each trip and mode of transport. In Switzerland, we used origin-destination matrix data from the Structural Survey, a component of the census, which is based on interviews of 200,000 people each year. The Survey collected individual-level data covering similar details as in the Dutch survey, also for the period 2010–2019 [28]. The work location was randomly drawn in a destination municipality. Each participant in the campaign was designated the profile that best fit their demographic data collected in the baseline questionnaire.

Exposure estimates

Two different approaches were used for the exposure modeling. In Switzerland, we rescaled annual average PM2.5 and NO2 surfaces (100 × 100m) for the year 2016, from previously published spatiotemporal geostatistical models [29, 30] to long-term hourly weekday and weekend day surfaces following a method previously applied by de Nazelle et al. [31]. Measured daily PM2.5 and NO2 data respectively from 9 and 63 background monitoring stations were used to calculate ratios that were then applied to the long-term concentration surfaces using the formula:

Where: RatioAnnual-hr is the ratio of the air pollutant concentration measured at background monitoring station (BS) at time hr (hour 1 to 24 h averaged over a year, hour 1 to 24 h averaged for weekday and weekend); CBS-hr is the measured air pollution concentration averaged for each given hour per year; and CBS-annual is the annual average air pollution concentration at all background stations in Switzerland.

These diurnal ratios were then applied to the annual average air pollution surfaces using the following formula:

Where: CP-t is the time-adjusted prediction at point P and time t; and CP-annual is the annual average pollutant concentration predicted by the LUR model at point P.

For the Netherlands, Ndiaye et al. [32] developed maps of annual average hourly concentrations of PM2.5 and NO2 using land use regression models (supervised linear regression (SLR) and random forest (RF)) based upon air quality monitoring data (n = 544 for NO2; n = 227 for PM2.5) in the Netherlands and the neighboring countries Belgium and Germany. Spatial variations of the average hourly concentrations were modeled for the years 2016–2019 combined, for two seasons (cold and warm), and for two weekday types (weekend and weekdays). Predictor variables included information about land use, roads, meteorology, population and satellite retrievals and chemical transport model estimates. SLR and RF models performed similarly, with 5-fold cross-validation R2 for the hourly models between 0.50–0.78 and 0.24–0.62 for NO2 and PM2.5, respectively. For the purpose of this study, we used the hourly surfaces derived from the RF models.

Figure 1 shows a diagram with the different exposures calculated for the tracking campaign participants in both countries.

Schematic representation of the different air pollution exposures calculated for the tracking campaign participants in Switzerland and the Netherlands; for all participants, Residential (RES), mobility-integrated ABM (with simulated workplace) and GPS exposures; for a subset, also the mobility-integrated ABMkWP (with known workplace).

Statistical analysis

Residential (RES), mobility-integrated ABM simulated workplace (ABM) and tracking (GPS) exposures were evaluated on their agreement through Bland-Altman plots, and further compared using the coefficient of determination (R2) and visualized in scattergrams. For the purpose of this assessment, we defined correlation coefficients (R2) as weak (<0.16), moderate (>0.16–0.36), moderately strong (>0.36–0.64), strong (>0.64–0.81) and very strong (>0.81). All analyses were performed separately for the Basel and the Netherlands populations. Additionally, we compared ABM (using the mean of the 50 realizations) and ABM with a known workplace (ABMkWP). This analysis was performed on a subset of the participants from whom we received the work address from the baseline questionnaire (Fig. 1). Shortest routes were calculated from home to the known work locations, and exposures extracted. We also conducted a simulation comparing the mean of the 50 realizations with a single random exposure from the distribution of the 50 realizations.

Results

Tracking campaign populations

In both tracking campaigns, female participants were notably overrepresented (Table 1). The majority of participants were employed, while a smaller proportion consisted of retired individuals. Participants with higher levels of educational attainment and in elevated income brackets were also disproportionately represented. When compared to national demographic statistics, it is evident that the samples derived from the campaigns do not fully reflect the broader population structures of the respective countries. Participants of the tracking campaigns in both countries resided in more urbanized areas compared to the national population, with urbanicity scores [33] of 49.3 and 42.2 for the Swiss and Dutch campaigns, compared to 23.9 and 26.6 for the total Swiss and Dutch populations, respectively. Nonetheless, the campaigns captured a reasonable degree of variation, including individuals from younger and older age groups, participants with low to medium education levels and income, and those not engaged in formal employment. Additionally, we compared the residential-only air pollution exposures in the tracking campaigns with those in 2 cohorts used in our epidemiological pape [25]. For Switzerland, we used the Swiss National Cohort, which is a cohort based on the national census, from which we used those over 30 years for whom we could assign exposure (approximately n = 3.5 M). In the Netherlands, the EPIC-NL cohort was used (n = 33.475). In Switzerland, the tracking campaign has higher mean NO2 and PM2.5 exposures compared to those of the SNC (NO2, 22.25 vs 17.00 µg/m3; PM2.5, 15.05 vs 13.51 µg/m3), confirming the urban setting in the Swiss tracking campaign (Table 2). The comparison in the Netherlands shows almost identical residential-only exposure for the tracking campaign and the EPIC-NL cohort.

In the Dutch campaign, 22 of the initial 189 participants dropped out due to either problems with activating the GPS tracker or its being non-functional during the data collection period, leaving 167 participants with collected tracking data.

Comparison of ABM simulated workplace and tracking campaign exposures

We pairwise compared exposures derived from the tracking campaign (GPS), the ABMs simulated workplace (ABM) and known workplace (ABMkWP) and the exposures based on the residential location only (RES). Figure 2 shows the Bland Altman plots for the three NO2 and PM2.5 exposure comparisons (GPS vs. ABM; RES vs. GPS; RES vs. ABM), where each point represents a participant of the campaign. Figure 3 shows the corresponding scatter plots, including the correlation. In Table 3, exposure distributions of the different methods are shown for the two tracking campaign populations, including for a subset of participants for which the workplace location was known and where we could additionally compare exposures estimated by ABM with ABMkWP. For 86 participants in Switzerland, we were unable to assign a PM2.5 exposure as some routes and/or work locations from the 50 realizations calculated by ABM fell outside the Swiss PM2.5 modeling extent (i.e., Basel is a city lying on the border with France and Germany with frequent cross-border traffic).

Bland Altman plots showing comparisons between exposures for the Swiss and Dutch tracking campaign participants NO2 and PM2.5 (μg/m3) exposures based on the tracking data (GPS); ABM using simulated workplace (ABM) and the residential location only (RES). Blue line shows the mean difference, dotted red line 95% confidence limits for the difference, and yellow line the regression line, accompanied by slope and R2.

The Bland-Altman plots (Fig. 2) show that the mean differences between the three exposure metrics are small, and that for the majority of the points, the difference between exposure metrics is small. For some participants, fairly large differences are observed, especially when comparing tracking-based exposures with RES or ABM. The comparison of RES versus ABM for both NO2 and PM2.5 shows a systematic bias with R2’s of the regression lines between 0.51 and 0.74, and a positive slope (0.15–0.21) in both Switzerland and the Netherlands. At low concentrations, the ABM exposure was higher than the RES exposure and vice versa at high concentrations. This can be explained by the fact that participants who reside in a low-polluted area tend to have a higher overall exposure when mobility patterns are included (i.e., ABM), as the probability that they work in a higher-polluted area is increased. The opposite is observed for participants residing in a highly polluted area. The same pattern, although less strongly, can be seen in the comparison between RES and GPS, especially in Switzerland (R2 0.22–0.24 and slope 0.26–0.29). The Bland-Altman plots for the comparison between GPS and ABM do not show a clear systematic pattern of differences versus the mean exposure, meaning that the estimated concentrations from the two approaches are similar.

Strong correlations were found between the GPS and ABM exposures for NO2 (CH: R2 = 0.77; NL: R2 = 0.78) and moderate strong for PM2.5 (CH: R2 = 0.80; NL: R2 = 0.54) (Fig. 3). The relatively lower correlation for PM2.5 found in the Netherlands is likely due to the small range of exposures (between 11 and 14 μg/m3) making it more difficult to estimate agreement. Similar correlations were found in the comparison between GPS and RES-based exposures (NO2: R2 = 0.78–0.79; PM2.5 R2 = 0.56–0.76). The comparison between ABM and RES yielded the highest correlations of >0.96 for both NO2 and PM2.5.

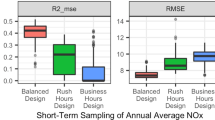

Comparison with ABM known workplace

For a subset of participants in both tracking campaigns (268 for NO2 and 201 for PM2.5 in CH, and 104 for both pollutants in NL), their work address information reported in the baseline questionnaire was taken into account in the exposure assessment. For both pollutants and both study areas, correlations between RES and both ABM exposures were strong to very strong (Fig. 4). The RES vs. ABMkWP correlations were slightly lower compared to those between RES and ABM exposures where the work location was probabilistically assigned (see Fig. 4). Correlations between the two mobility-integrated ABMs (ABM and ABMkWP) exposures were also very strong (R2 between 0.84 and 0.89), suggesting that ABM does a decent job in simulating the work address. Additionally, the very strong correlations between RES and ABMkWP (R2 between 0.81 and 0.90) give more weight to the robustness of the residential exposure. Lastly, we compared ABMkWP with GPS exposures. Similar to when using the full population (see Fig. 3), correlations were lower compared to the other three comparisons. The scatterplots illustrate higher variability in ABM modeled exposures with the known workplace compared to the simulated workplace, which includes averaging over 50 possible work addresses. The scatterplots of RES vs ABMkWP (Fig. 4) look more similar to the RES vs. GPS (Fig. 3) than the scatterplot of RES vs ABM. This is because both tracking and ABM know workplace use a specific track and work location for each individual, resulting in a similar “spread” in exposures between persons.

Simulation random instead of the mean of 50 realizations

To further evaluate the effect of taking the mean of 50 realizations of ABM simulated workplace in our main analysis on the agreement between RES and ABM exposure, we performed a simulation with the assignment of a single realization from the distribution of the 50 ABM realizations (Fig. S1). For the comparison with residential exposure, correlation using the mean of 50 ABM (also shown in Fig. 3) had a higher correlation than when using the single draw for all pollutant/country combinations. For example, the correlations for NO2 were reduced from 0.99 to 0.93 and from 0.95 to 0.78, respectively, in Switzerland and the Netherlands. The points in the scatterplot show more variability around the 1:1 in the single draw comparison. The resulting scatterplots are more similar to the ABM known workplace comparisons, but now for the full tracking population.

Discussion

We compared air pollution exposures based on the residential address with mobility-integrated air pollution exposures for almost 700 subjects in two tracking campaigns. For mobility-integrated exposures, we modeled exposures using ABM and assigned exposures as determined by the movements of individuals collected using the tracking data. In both tracking campaigns, conducted in two different study areas, very strong correlations were found between annual average residential exposure and mobility-integrated exposure for NO2 and PM2.5, both based upon observed tracking activity data and modeled ABM activity data. Furthermore, based on the same underlying air pollution data, the exposure levels—determined by the routes and time spent in specific locations—were very similar between both approaches. We did find a slightly smaller exposure contrast for ABM exposures (e.g., IQR = 4.93 µg/m3 for NO2 in NL; 11.03 in CH) compared to RES exposures (e.g., IQR = 5.93 µg/m3 for NO2 in NL; 13.94 in CH) (see Table 3). This can be explained by the phenomenon that subjects living in residential locations with high concentrations have a high probability of working in areas with lower concentrations and vice versa. Finally, we found that the residential exposure also correlated well with the mobility-integrated exposure based on actual time activity data in the tracking population.

Exposures estimated from tracking and ABM with known and simulated workplace

The two approaches used in this study, ABM and tracking, differ in multiple aspects. ABM is a modeling approach that can be applied to large populations. As ABM is based on large-time activity surveys, it is more representative of the total population than tracking studies. ABM, however, makes assumptions about activity patterns, e.g., that activity can be represented by a simple standard pattern (for weekdays, for weekend days), neglecting short-time variations. It also assumes that within “profiles”, activities are comparable between individuals. Tracking relies on actual measurements and can therefore only be applied for short periods in smaller populations. When tracking is used for estimating long-term exposures, we must assume that the activity over the duration for which tracks are available is representative of the long-term activity of individuals. It is likely that actual tracks over a year would show substantially more variation than what is measured over a short time span, but the general pattern of activity (home, work, commute/on roads) is possibly quite well represented. In both approaches, sensitive populations like the ill and elderly are likely not well represented; however, as these people tend to stay more at home, we likely underestimate the correlation for these groups.

The high correlation between tracking and ABM-based exposures supports the use of ABM modeling in large populations. The Bland-Altman plots comparing these exposures were very stable for both pollutants in the two study areas, meaning that the tracking and ABM-based concentrations were similar. However, the Bland-Altman plots do show a bias in that participants of our tracking campaigns residing in areas with relatively low ambient air pollution may experience elevated mobility-integrated exposure due to an increased likelihood of commuting to or working in regions with higher pollution levels. Conversely, participants residing in highly polluted areas are less likely to travel to environments with significantly higher pollution concentrations, resulting in comparatively lower total exposure when mobility is accounted for. For our study areas, however, we can conclude that air pollution exposures derived from the tracking campaigns were successfully modeled with ABM, which used information commonly available in cohorts and larger administrative cohorts (e.g., age, sex, socio-economic status and employment status). The lack of a gold standard for evaluating long-term personal exposure to outdoor-generated pollution complicates the assessment of how well the three exposure measures reflect true personal exposure.

ABM with simulated work location exposures, by design, also has more uncertainty compared to ABM with known work location. In addition, differences with residential exposures are smaller for ABM with a simulated work address. In general, ABM with a known work location is preferable and collecting work location data in cohort studies is advantageous. The high correlation between the two ABM approaches and the good correlation with tracking-based exposures, however, suggests that ABM with simulated work addresses provides a reasonable approach to estimate exposure beyond residential address in studies that do not have known work addresses.

Comparison with previous studies

Our observations are in line with several previous studies comparing residential and mobility-integrated exposures [13, 14, 34,35,36]. In all these studies, agent-based modeling was conducted using time surveys. Setton and co-workers documented that the agreement between residential and mobility-integrated exposure diminished with increasing time at work and with increasing distance between home and work locations [36]. A recent study using tracking data also reported high correlations for noise and PM2.5 [20]. Other studies have performed comparisons without ABM, thus based solely on exposure determined at the residential address location (home) vs. exposures including work address (work) and/or during commute. A study in Basel, Switzerland, compared exposure at the residential address with exposure whilst commuting and at the work/school address [14], indicating that, while there is room for improvement, it is reasonable to use exposure characterized at the residential address. A study in Montreal, Canada, showed that almost 90% of individuals had a lower 24-h daily average NO2 estimated at home compared to a mobility-integrated NO2 exposure [37]. Researchers in the Netherlands followed 269 adults with a GPS-enabled App for 7 days and compared the residential exposure only with a mobility-integrated PM2.5 exposure, concluding that the residential exposure was a good proxy for overall exposure to outdoor air pollution [20]. A study in Shenzhen, China, used cell phone data from more than 300,000 individuals to assess the impact of mobility on air pollution exposure. They concluded that while mobility impacted exposure on the individual level, it did not significantly impact exposures at the population level, in particular for larger studies [38]. A study in the UK compared population-weighted NO2, PM2.5 and O3 exposures at the residential address only with a combined residential and work exposure. They used a chemistry transport model to estimate rush-hour specific long-term averages and found only a small increase in population-weighted NO2 and PM2.5 exposures when including the work location (2 and 0.3%, respectively) [39].

Few studies have applied ABM to assess mobility-integrated air pollution exposures. Lu et al. used ABM to estimate exposures to NO2, incorporating work location and commuting patterns for the population of the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands. They found very high correlations between residential and mobility-integrated exposures (R2 > 0.93) [40].

Only a few studies were able to compare personal air pollution measurement data with residential and mobility-integrated exposures. Recently, Wei et al. compared personal measurements of PM2.5 and BC for 41 adults in the Netherlands with modeled home-based and mobility-based exposures [41]. They found that mobility-based exposures better represented personal measurements compared to home-based exposures, and that adjusting for the indoor-outdoor ratio was more important than adjusting for travel modes in improving the exposure assessment. A challenge in all direct personal monitoring studies is to assess individual long-term exposure and separation of indoor and outdoor sources. For acute health effect studies, direct personal exposure monitoring has been applied more often [42].

A recent review of air pollution exposure studies comparing residential and mobility-integrated exposures evaluated a number of epidemiological studies that compared health effects using the two approaches to evaluate exposures [17]. They found that the agreement between residential and mobility-integrated exposures was generally high (R > 0.8).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest study in terms of participants (n = 686), collecting 2 weeks of tracking data with detailed time activity. This allowed for a robust comparison between a number of approaches to determine exposures (residential, mobility-integrated with and without known workplace, real-time activity patterns) and to perform a thorough evaluation.

We conducted the tracking campaigns in two countries, broadening the applicability of our findings to similar demographic and geographical settings.

The participants of the tracking campaigns in both countries, however, were not representative of the full Swiss or Dutch populations, with overrepresentation in the 40–60 year old, higher education, high income and full-time worker groups. The overrepresentation of highly educated participants in the tracking study populations is in agreement with most exposure and epidemiological studies involving invited participation. Participants in both tracking campaigns also resided in more urbanized areas compared to the national population. The travel survey data, which we used to inform the ABM, were, however, specific to each country and more representative, which, given the high comparison between ABM and tracking, suggests that our tracking populations were not too unrepresentative.

Our findings apply to long-term air pollution exposure; we did not evaluate the impact of mobility on short-term exposure estimates. Our findings further apply to the studied pollutants, specifically NO2 and PM2.5. As NO2 is often considered a surrogate for traffic-related pollution, we suspect that qualitatively our findings apply to other traffic-related pollutants. If the spatial pattern of the pollutants differs substantially, however, results may be different.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the assessment of air pollution exposures at the residential address in epidemiological studies agrees well with more dynamic exposure assessments integrating time activity patterns based on tracking subjects and/or agent-based modeling. This agreement may be different in settings with different work and commuting patterns. Additionally, given the urban setting of this study, future studies should investigate whether our findings also apply to a more rural setting.

Data availability

The ABM modeling framework is free and open-source software under the MIT License and available at https://github.com/computationalgeography/agent_based_exposure_assessment.

References

Thurston GD, Kipen H, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes J, Brook RD, Cromar K, et al. A joint ERS/ATS policy statement: what constitutes an adverse health effect of air pollution? An analytical framework. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1600419.

WHO. Burden of disease from ambient air pollution for 2016 v2 2018. WHO, 2018.

Chen J, Hoek G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;143:105974.

Huangfu P, Atkinson R. Long-term exposure to NO(2) and O(3) and all-cause and respiratory mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;144:105998.

Murray CJ, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49.

Boogaard H, Patton AP, Atkinson RW, Brook JR, Chang HH, Crouse DL, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and selected health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2022;164:107262.

HEI Institute. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Selected Health Effects of Long-Term Exposure to Traffic-Related Air Pollution. Special Report 23. Boston: Health Effects Institute; 2022.

Patton AP, Boogaard H, Vienneau D, Brook JR, Smargiassi A, Kutlar Joss M, et al. Assessment of long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution: an exposure framework. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2025;35:493–501.

Duan N. Models for human exposure to air pollution. Environ Int. 1982;8:305–9.

Ott W, Wallace L, Mage D, Akland G, Lewis R, Sauls H, et al. The Environmental Protection Agency’s research program on total human exposure. Environ Int. 1986;12:475–94.

Di Q, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, Wang Y, Koutrakis P, Choirat C, et al. Air pollution and mortality in the medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2513–22.

Stafoggia M, Oftedal B, Chen J, Rodopoulou S, Renzi M, Atkinson RW, et al. Long-term exposure to low ambient air pollution concentrations and mortality among 28 million people: results from seven large European cohorts within the ELAPSE project. Lancet Planet Health. 2022;6:e9–18.

Ntarladima A-M, Karssenberg D, Vaartjes I, Grobbee DE, Schmitz O, Lu M, et al. A comparison of associations with childhood lung function between air pollution exposure assessment methods with and without accounting for time-activity patterns. Environ Res. 2021;202:111710.

Ragettli MS, Phuleria HC, Tsai M-Y, Schindler C, de Nazelle A, Ducret-Stich RE, et al. The relevance of commuter and work/school exposure in an epidemiological study on traffic-related air pollution. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;25:474.

Kwan M-P. From place-based to people-based exposure measures. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1311–3.

Steinle S, Reis S, Sabel CE. Quantifying human exposure to air pollution—Moving from static monitoring to spatio-temporally resolved personal exposure assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2013;443:184–93.

Hoek G, Vienneau D, de Hoogh K. Does residential address-based exposure assessment for outdoor air pollution lead to bias in epidemiological studies? Environ Health. 2024;23:75.

Ma J, Tao Y, Kwan M-P, Chai Y. Assessing mobility-based real-time air pollution exposure in space and time using smart sensors and GPS trajectories in Beijing. Ann Am Assoc Geogr. 2020;110:434–48.

Roberts H, Helbich M. Multiple environmental exposures along daily mobility paths and depressive symptoms: a smartphone-based tracking study. Environ Int. 2021;156:106635.

Wei L, Kwan M-P, Vermeulen R, Helbich M. Measuring environmental exposures in people’s activity space: the need to account for travel modes and exposure decay. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023;33:954–62.

Lu M, Schmitz O, de Hoogh K, Hoek G, Li QR, Karssenberg D. Integrating statistical and agent-based modelling for activity-based ambient air pollution exposure assessment. Environ Model Softw. 2022;158:105555.

Lu Y. Beyond air pollution at home: assessment of personal exposure to PM2.5 using activity-based travel demand model and low-cost air sensor network data. Environ Res. 2021;201:111549.

Kyriakou K, Flückiger B, Vienneau D, Probst-Hensch N, Jeong A, Imboden M, et al. GPS tracking methods for spatiotemporal air pollution exposure assessment: comparison and challenges in study implementation. Int J Health Geogr. 2025;24:17.

Jeong A, Galliker F, Imboden M, Keidel D, de Hoogh K, Vienneau D, et al. Residential exposure to greenspace and life satisfaction in times of COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis of 9444 participants from a population-based study in Basel-Stadt and Basel-Landschaft. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152:w30204.

Ndiaye A, Vienneau D, Flückiger B, Probst-Hensch N, Jeong A, Imboden M, et al. Associations between long-term air pollution exposure and mortality and cardiovascular morbidity: a comparison of mobility-integrated and residential-only exposure assessment. Environ Int. 2025;198:109387.

Schmitz O, de Hoogh K, Probst-Hensch N, Jeong A, Flückiger B, Lu M, et al. A computational framework for agent-based assessment of multiple environmental exposures. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2025; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00799-7. [Online ahead of print].

CBS, Statistics Netherlands. 2024 [cited 22 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/deelnemers-enquetes/personen/overzicht/onderweg-in-nederland.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Structural Survey. 2021 [cited 31 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/surveys/se.html.

de Hoogh K, Héritier H, Stafoggia M, Künzli N, Kloog I. Modelling daily PM2.5 concentrations at high spatio-temporal resolution across Switzerland. Environ Pollut. 2018;233:1147–54.

de Hoogh K, Saucy A, Shtein A, Schwartz J, West EA, Strassmann A, et al. Predicting fine-scale daily NO2 for 2005–2016, incorporating OMI satellite data across Switzerland. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:10279–87.

de Nazelle A, Seto E, Donaire-Gonzalez D, Mendez M, Matamala J, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, et al. Improving estimates of air pollution exposure through ubiquitous sensing technologies. Environ Pollut. 2013;176:92–9.

Ndiaye A, Shen Y, Kyriakou K, Karssenberg D, Schmitz O, Flückiger B, et al. Hourly land-use regression modeling for NO2 and PM2.5 in the Netherlands. Environ Res. 2024;256:119233.

de Hoogh K, Hoek G, Flückiger B, Bussalleu A, Vienneau D, Jeong A, et al. A Europe-wide characterization of the external exposome: a spatio-temporal analysis. Environ Int. 2025;200:109542.

Blanchard O, Deguen S, Kihal-Talantikite W, François R, Zmirou-Navier D. Does residential mobility during pregnancy induce exposure misclassification for air pollution? Environ Health. 2018;17:72.

Ntarladima A-M, Vaartjes I, Grobbee DE, Dijst M, Schmitz O, Uiterwaal C, et al. Relations between air pollution and vascular development in 5-year-old children: a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Environ Health. 2019;18:50.

Setton E, Marshall JD, Brauer M, Lundquist KR, Hystad P, Keller P, et al. The impact of daily mobility on exposure to traffic-related air pollution and health effect estimates. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2011;21:42–8.

Shekarrizfard M, Faghih-Imani A, Hatzopoulou M. An examination of population exposure to traffic-related air pollution: comparing spatially and temporally resolved estimates against long-term average exposures at the home location. Environ Res. 2016;147:435–44.

Yoo E-h, Pu Q, Eum Y, Jiang X. The impact of individual mobility on long-term exposure to ambient PM2.5: assessing effect modification by travel patterns and spatial variability of PM2.5. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2194.

Reis S, Liška T, Vieno M, Carnell EJ, Beck R, Clemens T, et al. The influence of residential and workday population mobility on exposure to air pollution in the UK. Environ Int. 2018;121:803–13.

Lu M, Schmitz O, Vaartjes I, Karssenberg D. Activity-based air pollution exposure assessment: differences between homemakers and cycling commuters. Health Place. 2019;60:102233.

Wei L, Donaire-Gonzalez D, Helbich M, van Nunen E, Hoek G, Vermeulen RCH. Validity of mobility-based exposure assessment of air pollution: a comparative analysis with home-based exposure assessment. Environ Sci Technol. 2024;58:10685–95.

van Nunen E, Hoek G, Tsai M-Y, Probst-Hensch N, Imboden M, Jeong A, et al. Short-term personal and outdoor exposure to ultrafine and fine particulate air pollution in association with blood pressure and lung function in healthy adults. Environ Res. 2021;194:110579.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the COVCO Basel Team, and in particular M. Witzig, N. Oswald, D. Keidel, and E. Schaffner. We acknowledge funding of COVCO-Basel by the Health Directorates of the cantons BS and BL.

Funding

This work was performed in the framework of the MOBI-AIR study, funded by the Health Effects Institute, grant agreement # 4972-RFA19-1/20-6. The authors declare no competing financial interest. Open access funding provided by University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT: Kees de Hoogh: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; Benjamin Flückiger: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; Nicole Probst Hensch: Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; Ayoung Jeong: Data curation, Writing—review & editing; Medea Imboden: Data curation, Writing—review & editing; Aletta Karsies: Data curation, Writing—review & editing; Oliver Schmitz: Data curation, Investigation, Writing—review & editing; Roel Vermeulen: Resources, Writing—review & editing; Kalliopi Kyriakou: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; Aisha Ndiaye: Data curation, Writing—review & editing; Youchen Shen: Data curation, Writing— review & editing; Derek Karssenberg: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; Danielle Vienneau: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; Gerard Hoek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The Dutch tracking campaign received an ethics exemption from the Medische Ethische Toetsingscommissie (METC) Utrecht, as no health-related data was collected from the participating subjects (WAG/mb/20/007879). The Swiss tracking campaign was approved by the Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (EKNZ) as it recruited from the EKNZ-approved ongoing COVCO-Basel study (Nr. 2020-00927 and Nr. 2021-01704, respectively). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the Dutch and Swiss tracking campaigns.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Hoogh, K., Flückiger, B., Probst-Hensch, N. et al. Comparison of residential and mobility-integrated air pollution exposures from tracking campaigns and agent-based modelling in Switzerland and the Netherlands. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00836-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00836-5