Abstract

Objective

Pulse oximetry is used to guide critical clinical decisions in neonatology. We used a vital signs simulator to compare performance of two pulse oximetry systems in conditions not tested in standardized clinical verification studies.

Study design

We devised a set of simulated tissue translucency, perfusion, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and heart rate (HR) parameters to mimic challenging real-world neonatal data and applied them to two marketed pulse oximetry systems (Nellcor™ and Masimo®). At each combination of input parameters, we used the response from both systems to assess SpO2 error.

Results

The mean SpO2 error for Nellcor™ was below 1.1% across all parameters explored, while Masimo® showed significantly higher (p < 0.005) error at lower translucencies.

Conclusion

Significant performance differences can be observed when comparing pulse oximeters at low translucency and perfusion conditions. Patient simulators cannot replace clinical testing but provide a safe and cost-effective method for additional performance profiling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulse oximetry has become a standard of care for continuous monitoring in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and is used in a variety of contexts, including guiding resuscitation in the delivery room [1, 2], monitoring of oxygen saturation in the operating room, and more recently, to screen for critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) [3,4,5].

Further, pulse oximetry is used to guide careful titration of respiratory support in the first few days of life, when preterm neonates typically undergo a transition in physiology and an accurate evaluation of subclinical hypoxemia is critical for the evolving diagnostic and medical management. Preterm infants must maintain a tenuous balance when receiving supplemental oxygen, as small changes in the level of oxygenation have been associated with adverse outcomes such as retinopathy of prematurity, intraventricular hemorrhage and increased mortality [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Despite being widely used in neonatal clinical practice, there are specific characteristics of the neonate which can challenge the accuracy of pulse oximetry systems, including low tissue translucency, poor perfusion and motion artifacts [1, 9,10,11,12]. Low translucency conditions are mainly due to dark skin pigmentation or thick tissue sites (pulse oximetry sensors are typically positioned on the neonates’ hands or feet, as their digits are simply too small). Moreover, neonates, especially those born preterm, have proportionally lower blood pressures, including a pulse pressure only about 50% of the magnitude of adults [13]. These infants also have immature peripheral vascular autoregulation, with diminished distal blood flow, further complicated by thermoregulatory instability [14]. The net effect of these factors is a marked reduction in the signal to noise ratio in pulse oximeters readings, which is difficult to replicate in healthy adult subjects on whom these devices are traditionally clinically verified.

Current methods for accuracy verification of a pulse oximeter used on neonates, outlined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance [15] and by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 80601-2-61 standard [16], involve a controlled hypoxia study—limited to healthy adults for ethical and practical reasons—coupled with a convenience sampling study on neonates with arterial lines already in place for verification of clinical performance. These standardized methods are necessary to confirm the calibration curve for a pulse oximetry system [17], which is key for an accurate conversion from optical signals to peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) readings. However, they do not challenge the pulse oximetry systems over the entire space of possible neonatal signals; specifically, they do not assess accuracy of these systems in the above-mentioned low translucency and low perfusion conditions at varying saturation levels.

Patient simulators, designed to create synthetic signals that mimic human vital signs and equipped with extensive configuration options (including varying simulated vital parameters and various signal artifacts), may fill the gap between controlled standardized studies and uncontrolled real-world clinical settings without posing additional risks to fragile subjects. Simulators cannot replace standardized clinical testing, as they are unable to fully reproduce the actual tissue-sensor interface [17], which is essential to assess the clinical accuracy of pulse oximetry systems. However, simulators can be used to challenge and improve the design of these systems and may provide a streamlined, cost-effective method for supplemental pre-clinical verification of their performance [18].

In this work, a cohort of real-world pulse oximetry data gathered from the NICU was used to inform a bench test comparison of SpO2 monitoring performance of two widely used pulse oximetry systems in low-translucency and low-perfusion conditions representative of neonatal patients.

Methods

Pulse oximetry systems under test

This work compared the performance of the following two pulse oximetry systems:

-

(1)

Nellcor™ system: a Nellcor™ OxiMax™ N-600x patient monitor (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) coupled with a set of seven distinct DS100A-1 finger sensors.

-

(2)

Masimo® system: a Rad-97™ Pulse CO-Oximeter® (Masimo®, Irvine, CA) paired with a set of seven distinct RD SET™ DCI® finger sensors.

The number of tested finger sensors was chosen to provide a preliminary insight on performance variability within a pulse oximetry system.

Testing equipment

In pulse oximetry, simulators work by presenting pulse oximetry systems with optical signals appropriately designed to mimic the way in which the LED light emitted by a finger sensor is modulated when passing through real tissues before reaching the corresponding photodetector.

In this in silico study, we assessed how translucency, perfusion, peripheral oxygen saturation and heart rate (HR) impact on error in the SpO2 readings displayed on the tested systems.

We designed a set of test parameters (detailed in Table 1) encompassing, for each of the four variables of interest, a range of values aligned to those expected in the NICU population. We were specifically interested in simulating the most critical values that could be encountered in NICU patients, to challenge pulse oximetry systems performance in conditions not typically assessed in clinical verification studies under current regulatory requirements.

Test parameters were generated using a ProSim™ 8 Vital Signs Simulator (Fluke®, Everett, WA). A SPOT Light SpO2 Functional Tester (Fluke®, Everett, WA), consisting of an artificial finger on which the tested finger sensors were applied, was connected to the Simulator. Both Nellcor™ and Masimo® tested finger sensors had their calibration information encoded into the Simulator. Figure 1 provides an overview of the test setup.

Simulated parameters, selected based on real-world NICU data, were sent to the pulse oximetry system under test (pulse oximeter + connected finger sensor) via the Simulator and the SpO2 Functional Tester. A shielding enclosure ensured all testing equipment was protected from ambient light, which may cause signal artifacts. All parameters measured by the pulse oximetry system under test were then transferred to the data acquisition computer and stored for analysis.

Simulated clinical parameters

Translucency and perfusion parameters

Translucency and perfusion were the primary variables of interest for this testing.

Translucency represents the property of materials of allowing light to pass through them. In this work it was expressed in terms of % transmission (%T), a parameter approximately representing the percent amount of a sensor’s LED light that reaches the corresponding photodetector after passing through tissue (see Eq. (1) in the Supplementary Materials for further details). In a clinical setting, %T values depend on both tissue thickness and amount of melanin at monitoring sites, with lower %T typically associated to thick and darkly pigmented sites.

Perfusion is a variable representing the amount of blood in tissues, which varies in a pulsatile fashion. In this work, perfusion was defined in terms of % modulation (%MOD), an indicator of pulsatile optical signal strength that relies on correlation between the amount of light able to pass through tissues and hemodynamic changes [19,20,21].

Specifically, %MOD represents the percent ratio between the variable (due to attenuation of pulsing blood) and the constant (due to attenuation of other elements, like venous blood, water, bone, and melanin) components of the signal generated by a finger sensor’s LED light passing through a perfused tissue (see Eq. (2) in the Supplementary Materials for further details).

Simulated %T and %MOD parameters (Table 1) were selected based on the distribution of real-world data collected from NICU patients in two prior multicenter observational clinical studies. These studies were designed to follow FDA guidance [15] on verifying safe form, fit, and function of the OxySoft™ neonatal-adult SpO2 sensor (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) against reference CO-oximetry measurements of arterial oxygen saturation from convenience arterial lines. NICU data were collected using a Nellcor™ OxiMax N-600x patient monitor, equivalent to the one tested in the present work, paired to OxySoft™ neonatal-adult SpO2 sensors positioned on the neonates’ feet. Skin tone data were also collected from all NICU patients and categorized using a four-level scale.

These studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all local regulatory requirements and were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (IRB00000533) and the Timpanogos Regional Hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB00003926). Written informed consent, including consent to secondary use of clinical data for research purposes, was obtained from the subjects’ parents. All methods were performed in accordance with applicable governmental and institutional guidelines and regulations. The Supplementary Materials provide additional details on the equations and methods used to calculate %T and %MOD values from the reference NICU datasets and thus derive the set of simulated physiological parameters for testing.

SpO2 and heart rate parameters

Simulated SpO2 and HR parameters were selected based on supporting literature findings, as reported in Table 1. Of note, HR values were specifically selected to reproduce critical real-world conditions known to be challenging for pulse oximetry systems, such as cases of HR < 100 bpm, that usually prompt positive-pressure ventilation or other emergent interventions [22]. For all test cases the Simulator cardiac waveform was set to “Child Normal Sinus Rhythm” (NSR—Pediatric).

Testing procedure

For both Nellcor™ and Masimo® systems, all seven tested finger sensors were sequentially placed on the SpO2 Functional Tester, as the Simulator was cycled automatically through all the combinations of the parameters in Table 1. All simulated values were within the performance range of the Simulator [23]. Parameter variation was performed via a pre-programmed set of nested loops: %T varied most slowly, then %MOD, then SpO2, with HR varying in the innermost loop.

Pulse oximetry systems performance was tested in a best-case scenario, with the Simulator respiration and ambient-light artifacts kept inactivated and the system positioned in a light-shielded box to exclude any ambient-light artifact (Fig. 1). For each combination of parameters, data were collected from each finger sensor for 45 s. There were no predefined exclusion criteria for the collected data. Error-handling techniques were considered based on analysis of the collected data. Throughout all test runs, a fiducial mark was used to ensure finger sensors were consistently placed in the same position and orientation with respect to the SpO2 Functional Tester.

Performance metric

The mean SpO2 error (expressed as absolute value) was the performance metric for this test. For each combination of Simulator parameters, the mean SpO2 error for each system was calculated as the weighted average of the difference over all seven finger sensors between SpO2 values reported by the pulse oximetry systems and SpO2 values input from the Simulator (Eq. (3) in the Supplementary Materials).

A mean SpO2 error of 3% was selected as a threshold to identify potential performance concerns.

Statistical analysis of SpO2 error

An additional analysis was conducted to support a quantitative comparison between Nellcor™ and Masimo® systems across selected points of interest of a signal space defined by the primary variables (%T, %MOD).

First, the mean SpO2 error over a defined point of the (%T, %MOD) signal space was calculated for each individual finger sensor (Eq. (4) in the Supplementary Materials).

Then, for each test point, the seven estimates of the mean SpO2 error for the Nellcor™ system were compared to the same seven estimates for the Masimo® system using a t-test (allowing for unequal variances for the pulse oximeter type).

For this test, we did assume a normal distribution of errors across all test parameters for both systems, as well as a normal distribution of performance amongst the seven tested sensors.

Statistical analyses were run through the statsmodels Python package [24]. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 at 95% confidence level.

Results

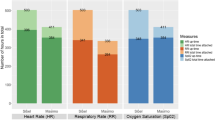

Figure 2 shows mean SpO2 errors for both Nellcor™ and Masimo® systems over the seven tested sensors as a function of the four test parameters. No error-handling techniques were needed on the data acquired from both systems.

Each inset graph has its lower-left vertex placed at the (%T, %MOD) coordinates corresponding to the settings for that subset of data acquisition. The colored circles in the inset graphs show the mean absolute value of SpO2 error as measured across the seven finger sensors at each individual setting of HR (inset graph, horizontal axis) and SpO2 (inset graph, vertical axis). Mean SpO2 error is color-coded according to the bar legend on the left of the Figure, with all instances exceeding the 3% threshold displayed in red. The distribution of benchmark clinical NICU data has been overlaid on the (%T, %MOD) space. Each datapoint (gray triangle) represents the median %T/%MOD value of a 10-min epoch of collected NICU data, while the blue shaded region represents their probability density. Deeper colors indicate a higher amount of datapoints in a specific signal space region. Periods of time that the sensor was disconnected or removed from the NICU patients were excluded from the analysis.

Datapoints in red represent the conditions where the mean SpO2 error exceeded the pre-defined threshold of 3%. All numerical results are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

The mean SpO2 error for the Nellcor™ system was ≤1.1% % across all parameters explored (0.23 ± 0.24% at %T > 1%; 0.17 ± 0.21% at %T ≤ 1%), suggesting consistent accuracy and repeatability even at the lowest translucency and perfusion settings. The Masimo® system performed well at higher translucencies (mean absolute error 0.33 ± 0.33% at %T > 1%); however, at the lower-translucency settings higher error was reported (2.79 ± 1.62% at %T ≤ 1%) as shown by the red datapoints in Fig. 2, particularly at lower SpO2 values, but roughly independently of heart rate. The highest reported mean SpO2 error was 1.1% for the Nellcor™ system and 6.4% for the Masimo® system.

To understand the challenging nature of the parameters used for this performance comparison, our reference data distribution derived from NICU clinical trials was overlaid to the same (%T, %MOD) signal space where the SpO2 error data were plotted. The NICU data were collected from 34 neonates (mean age 3.3 ± 2.3 days) with the following representation of skin tones: “extremely dark hue”: 1/34 (2.94%), “dark olive hue”: 8/34 (23.53%), “olive hue”: 15/34 (44.12%) and “very light hue”: 10/34 (29.41%).

Figure 2 shows that most of the benchmark NICU data fall in a region of the (%T, %MOD) signal space where both systems showed an average SpO2 error <1% (%T > 1%); however, considering the limited representation of neonates with darkly pigmented skin in the reference NICU dataset, it can be hypothesized that a wider real-world NICU distribution could further expand to the left of the plot (at %T < 1%), where the difference in SpO2 errors between the two pulse oximetry systems was found to be even higher.

A statistical comparison between mean absolute SpO2 errors for Nellcor™ and Masimo® systems was performed for regions of the (%T, %MOD) signal space selected based on the challenging nature of their parameters or on amount (or expected amount) of NICU data represented within them.

Results, reported in Table 2, show statistically significantly lower SpO2 errors (p < 0.005) for the Nellcor™ system across all tested points of the space, with more consistent differences between the two systems at low %T values.

Confidence intervals show relatively small variance of the difference between mean absolute SpO2 errors, particularly at higher %T and %MOD values.

Discussion

Since the first introduction of pulse oximeters to the NICU in the 1980s, they have become part of the standard of care and SpO2 is widely considered the “fifth vital sign” [25, 26]. Major professional bodies, including the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have endorsed the central role of continuous pulse oximetry monitoring in targeted oxygen saturation management during neonatal life support and in guiding judicious use of oxygen therapy during neonatal resuscitation, to avoid major morbidities that have been widely shown to be related to hypoxemia or hyperoxemia [2]. In agreement, consensus European guidelines recommend the use of pulse oximetry to monitor infants’ saturation during the first minutes after birth and to adjust oxygenation levels in neonates with respiratory distress syndrome [27].

Pulse oximetry is used throughout NICU hospitalization to manage many aspects of care including the titration of respiratory support and discharge readiness determination [1]. More recently, pulse oximetry has been used for the screening of CCHD in asymptomatic newborns [3, 4] and has demonstrated higher sensitivity compared to alternative strategies (such as prenatal screening and clinical examination) and a low false-positive rate [5].

In each of these use cases, the accuracy of pulse oximetry is vital; failure to intervene in a timely and appropriate manner could impact morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Although all currently available medical-grade pulse oximetry systems must comply with the same regulatory requirements, their real-world performance can vary significantly in conditions that are not typically tested in standardized clinical verification studies but which represent the most challenging portions (in terms of translucency and perfusion) of real-world NICU data distributions. Unfortunately, these challenging conditions are those in which pulse oximetry systems are relied upon most heavily in the clinical practice, as they are representative of instances of significant pathophysiology, such as critically ill neonates with poor perfusion. Although there has been increasing recognition of the limitations of pulse oximetry in recent years [28] (including for neonates, specifically [29, 30]), the overall awareness among health care providers of these potential technical deficiencies and of their impact on the direction or expediency of clinical intervention is still lacking.

In the last few decades, patient simulators have increasingly been used for supplemental bench testing of pulse oximetry system performance; however, as most of this work is done through manufacturer’s pre-market testing or routine inspection in hospital clinical engineering departments, published data is still scarce. Ganesh Kumar et al. recently tested SpO2 and pulse rate accuracy of six pulse oximeters using an SpO2 simulator and observed performance deterioration in over half of the tested devices in the presence of motion artifact and low perfusion conditions [18]. Although their study did not utilize neonate-specific parameters, their testing method parallels the one used in our study. The authors highlighted the ability of simulators to span a much wider range of variables and to achieve higher repeatability compared to what can typically be done in tests on volunteers in a simulated clinical setting. Further, they encouraged the use of simulators to challenge pulse oximeter performance in physiological or pathological conditions representative of specific patient populations. It is worth remembering, however, that while patient simulators can highlight areas of performance concern that would likely be confirmed in a clinical setting, they are not able to reproduce every facet of the complex physiological behaviors that occur in real subjects and other confounding factors.

In this work, we used a vital sign simulator coupled with a functional tester to investigate differences in the response of two pulse oximetry systems in non-clinically verified conditions representative of NICU patients. Over the entire set of test parameters, both Nellcor™ and Masimo® systems were found to perform within the combined accuracy specifications of each of the oximeters and of the Simulator [23, 31, 32], thus meeting performance requirements defined by current regulatory standards. However, when focusing on low translucency conditions (representative, per Fig. 2, of a consistent portion of a real-world NICU distribution), we observed that the two systems started to deviate in performance, with the Masimo® system reporting mean SpO2 errors up to 3.9% in specific areas of interest (Table 2) and up to 6.4% when looking at specific simulated low saturation conditions (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Materials).

Though current standards for pulse oximeters performance verification define a 4% threshold for SpO2 accuracy of these equipment when tested on healthy adults [15, 16], we set our threshold for mean SpO2 error to 3% considering that stricter requirements are currently being envisioned [33] due to a concern for pulse oximeters disparate performance in the clinical practice [28].

While recognizing that synthetic data can only partially reproduce the variability of a clinical setting, we believe the amount of red datapoints in Fig. 2 justifies the concern that, in critical conditions, some pulse oximeters may show inaccurate readings that, in turn, may lead to erroneous clinical decisions.

Based on recently updated recommendations on CCHD screening in newborns [34], a difference greater than 3% in SpO2 readings from two monitoring sites at SpO2 levels between 90% and 95% represents a condition for screen failure, and thus prompts additional clinical assessment.

Though the tested oximetry systems didn’t show mean SpO2 errors greater than 3% at SpO2 levels above 90%, we believe these new recommendations support our selection of a 3% mean SpO2 error as a suitable threshold to identify potential performance issues, as the magnitude of reported error shouldn’t exceed the quantity under investigation.

Our findings are further supported by results from a recent study by Gudelunas et al. on healthy adult volunteers with varying skin pigmentation, which also identified performance differences between Nellcor™ and Masimo® pulse oximetry systems [35]. The authors found that SpO2 error (defined in their study as the difference between SpO2 and oxygen saturation of arterial blood (SaO2)) for both devices was dependent on the combined effect of the amount of melanin, perfusion, and degree of hypoxemia. Specifically, they observed that in subjects with darkly pigmented skin and low perfusion, missed hypoxemia events (defined as SaO2 values < 88% and corresponding SpO2 values between 92% and 96%) were found in 30.2% of the Masimo® readings and in 7.9% of the Nellcor™ readings.

Interestingly, the hypoxia testing by Gudelunas et al. showed a dependence of SpO2 error on perfusion, whereas no correlation between SpO2 error and %MOD was observed in our testing with the simulator. This finding might be explained by the intrinsic nature of the simulation testing, that allows a satisfactory evaluation of the electro-optical response of pulse oximetry systems to changes in translucency but, as mentioned, is not able to adequately reproduce the physiological tissue-related variables at varying perfusion conditions, which also impacts the response and overall accuracy of this equipment.

Considering that low perfusion states are even more frequent and consequential in real-world NICU populations (as shown by the consistent amount of NICU data at %MOD < 1% in Fig. 2) and the role of pulse oximetry systems in the decision to apply oxygen supplementation in such cases, it should be noted again the importance of not relying solely upon simulator testing for equipment performance characterization. Further research on the optical properties of physiological tissues and their optical interactions with pulse oximetry probes may lead to the development of improved simulators able to adequately reproduce a comprehensive range of real-world subjects and is therefore highly encouraged.

This study was designed to pave the way for the development of new pre-clinical testing methods aimed to obviate some of the limitations of current verification testing required for regulatory approval of pulse oximeters. Due to its pilot nature, it presents some limitations. First, performance was compared in a best-case scenario; a simple heart rate rhythm was set, ambient light was excluded, and no respiratory or other artifacts were activated on the simulator. Second, the dimension of our reference real-world dataset was limited, and so was the representation of darkly pigmented subjects. In addition, skin pigmentation was not assessed using a standardized color scale or spectrophotometric measures (whose usefulness has been highlighted in several recent works [36, 37]), which would be beneficial to include in future studies. Further, as our reference data were derived from NICU patients, the varying contributions of skin thickness and melanin to translucency values during development, or low perfusion conditions typical of the delivery room (which could also impact the width of real-world neonatal data distribution, along both the %T and the %MOD axes) could not be accounted for. However, we expect future, larger, real-world datasets used to inform in silico testing will include greater diversity across more dimensions than those included in our reference sample. It is important to recall that current verification testing conducted per FDA and ISO requirements do not incorporate neonates at all. Third, the performance metric we used (mean SpO2 error), which was chosen for the sake of simplicity, is not the one defined in regulatory standards to determine pulse oximeter accuracy. However, as SpO2 accuracy is derived from both mean SpO2 error and its standard deviation, an increase in mean SpO2 error will also impact more complex performance metrics. Fourth, the sensors used in this bench testing (Nellcor™ DS100A-1 and Masimo® RD SET™ DCI® sensors) are not indicated for use on neonates but were chosen due to their compatibility with the selected simulator. Neonate-specific sensors may have different performance characteristics which, however, would not be expected to invalidate the main findings of this work.

Despite these limitations, our study highlights the role that in silico testing can have in pulse oximeters verification. Specifically, this work shows how simulators can be used to extend the range of tested clinical scenarios to include challenging edge cases where pulse oximeter accuracy is most challenged but also most critical in clinical decision making. Although pulse oximeters should not be used as the sole basis for diagnosis or treatment decisions, it remains intuitive that best care is achieved by having the most accurate measurements. Reliability demonstrated through expanded testing, including all clinical conditions of interest, could have a significant impact on both healthcare equity and costs.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware that pulse oximetry system performance may vary based on translucency and perfusion. This laboratory-based work compared SpO2 error between two commercially available pulse oximetry systems and identified a persistent performance difference between the two systems at low translucency values, which closely model the characteristics of real NICU patients.

While the current standard of clinical hypoxia testing for regulatory approval of oximeters may be sufficient to assess and verify device performance on many patients in many scenarios, such testing is not comprehensive and does not challenge the oximeters in the settings in which accuracy is most important. Further research in the use of synthetic data for bench testing in pulse oximetry is encouraged. Clinicians, manufacturers and regulators should consider the development of a standardized simulator-based pre-clinical testing method that spans a wide set of perfusion, absorption, and cardiovascular parameters aligned with real-world variability and not systematically reproducible in clinical settings. Such a joint effort would contribute towards more transparent and equitable healthcare and more dependable devices.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included in this article and in the Supplementary Materials. The code used to generate results is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

18 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02405-y

References

Dawson JA, Davis PG, O’Donnell CP, Kamlin CO, Morley CJ. Pulse oximetry for monitoring infants in the delivery room: a review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F4–7.

Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, Hoover AV, Kamath-Rayne BD, Kapadia VS, et al. Part 5: neonatal resuscitation: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142:S524–50.

Kemper AR, Mahle WT, Martin GR, Cooley WC, Kumar P, Morrow WR, et al. Strategies for implementing screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1259–67.

Engel MS, Kochilas LK. Pulse oximetry screening: a review of diagnosing critical congenital heart disease in newborns. Med Devices. 2016;9:199–203.

Thangaratinam S, Brown K, Zamora J, Khan KS, Ewer AK. Pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart defects in asymptomatic newborn babies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2459–64.

Carlo WA, Finer NN, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, Laptook AR, et al. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. N. Engl J Med. 2010;362:1959–69.

Stenson BJ, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Darlow BA, Simes J, Juszczak E, Askie L, et al. Oxygen saturation and outcomes in preterm infants—Boost Ii United Kingdom Collaborative Group—Boost Ii Australia Collaborative Group—Boost Ii New Zealand Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2094–104.

The Boost-II Australia and United Kingdom Collaborative G, Tarnow-Mordi W, Stenson B, Kirby A, Juszczak E, Donoghoe M, et al. Outcomes of two trials of oxygen-saturation targets in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:749–60.

Wackernagel D, Blennow M, Hellstrom A. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in preterm and term infants is insufficient to determine arterial oxygen saturation and tension. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:2251–7.

Poets CF, Wilken M, Seidenberg J, Southall DP, von der Hardt H. Reliability of a pulse oximeter in the detection of hyperoxemia. J Pediatr. 1993;122:87–90.

Hay WW Jr, Brockway JF, Eyzaguirre M. Neonatal pulse oximetry: accuracy and reliability. Pediatrics 1989;83:717–22.

Khoury R, Klinger G, Shir Y, Osovsky M, Bromiker R. Monitoring oxygen saturation and heart rate during neonatal transition. Comparison between two different pulse oximeters and electrocardiography. J Perinatol. 2021;41:885–90.

Vega-Barrera C, Muraskas J, Guo R, Ray B. The pulse pressure in a premature infant less than 37 weeks gestational age with a patent ductus arteriosus. Open J Pediatr. 2013;03:99–104.

Kissack CM, Weindling AM. Peripheral blood flow and oxygen extraction in the sick, newborn very low birth weight infant shortly after birth. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:462–7.

FDA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration—Pulse Oximeters—Premarket Notification Submissions [510(k)s]—Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Silver Spring, MD USA: FDA; 2013.

ISO. International Organization for Standardization—Medical electrical equipment Part 2-61: particular requirements for basic safety and essential performance of pulse oximeter equipment. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO; 2017.

Mannheimer PD. The light-tissue interaction of pulse oximetry. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:S10–7.

Ganesh Kumar M, Kaur S, Kumar R. Laboratory evaluation of performance of pulse oximeters from six different manufacturers during motion artifacts produced by Fluke 2XL SpO(2) simulator. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36:1181–91.

Sahni R. Noninvasive monitoring by photoplethysmography. Clin Perinatol. 2012;39:573–83.

Lima A, Bakker J. Noninvasive monitoring of peripheral perfusion. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1316–26.

Kroese JK, van Vonderen JJ, Narayen IC, Walther FJ, Hooper S, te Pas AB. The perfusion index of healthy term infants during transition at birth. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175:475–9.

Dawson JA, Saraswat A, Simionato L, Thio M, Kamlin CO, Owen LS, et al. Comparison of heart rate and oxygen saturation measurements from Masimo and Nellcor pulse oximeters in newly born term infants. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:955–60.

Fluke Biomedical; ProSim(TM) 8 Vital Signs Simulator Users Manual. Rev. 3, 2011. available at https://www.flukebiomedical.com/sites/default/files/resources/ProSim8_umeng0300.pdf.

Statsmodels version 0.14.1. available at: https://www.statsmodels.org/stable/index.html.

Chan ED, Chan MF, Chan MM. Pulse oximetry: understanding its basic principles facilitates appreciation of its limitations. Respir Med. 2013;107:789–99.

Mower WR, Sachs C, Nicklin EL, Baraff LJ. Pulse oximetry as a fifth pediatric vital sign. Pediatrics. 1997;99:681–6.

Sweet DG, Carnielli VP, Greisen G, Hallman M, Klebermass-Schrehof K, Ozek E, et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome: 2022 update. Neonatology. 2023;120:3–23.

Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2477–8.

Vesoulis Z, Tims A, Lodhi H, Lalos N, Whitehead H. Racial discrepancy in pulse oximeter accuracy in preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2022;42:79–85.

Foglia EE, Whyte RK, Chaudhary A, Mott A, Chen J, Propert KJ, et al. The effect of skin pigmentation on the accuracy of pulse oximetry in infants with hypoxemia. J Pediatr. 2017;182:375–7.e2.

Masimo. Rad-97™ Pulse CO-Oximeter Operator’s Manual—38281/LAB-9275D-0518. 2018.

Covidien. Nellcor N-600x Pulse Oximeter Operator’s Manual—Part No. 10074884 Rev C 2014-02. 2014.

FDA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration—Pulse Oximeters for Medical Purposes—Non-Clinical and Clinical Performance Testing, Labeling, and Premarket Submission Recommendations—Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Silver Spring, MD USA: FDA; 2025.

Oster ME, Pinto NM, Pramanik AK, Markowsky A, Schwartz BN, Kemper AR, et al. Newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease: a new algorithm and other updated recommendations: clinical report. Pediatrics. 2025;155:5.

Gudelunas MK, Lipnick M, Hendrickson C, Vanderburg S, Okunlola B, Auchus I, et al. Low perfusion and missed diagnosis of hypoxemia by pulse oximetry in darkly pigmented skin: a prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2024;138:552–61.

Verkruysse W, Jaffe MB, Lipnick M, Zemouri C. Challenges of subjective skin color scales: the case for the use of objective pigmentation measurement methods in regulatory pulse oximetry studies. Anesth Analg. 2024;139:e15–7.

Lipnick MS, Chen D, Law T, Moore K, Lester JC, Monk EP. et al. Comparison of methods for characterizing skin pigment diversity in research cohorts. medRxiv 2025; 2025.02.21.25322707.

Dawson JA, Kamlin CO, Vento M, Wong C, Cole TJ, Donath SM, et al. Defining the reference range for oxygen saturation for infants after birth. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1340–7.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Ilaria Pietta of Medtronic (Milan, Italy) in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

Funding

All work completed in this report was sponsored and funded by Medtronic. The authors had access to all data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors were not paid to write this article by the sponsor or any other agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BK and JD contributed to conception and design of testing, acquisition and analysis of data, and to writing of the manuscript. ZAV contributed to conception of the manuscript flow, interpretation of the data and to writing of the manuscript. SMG contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data. WA contributed to interpretation of the data. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for the accuracy or integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JD and SMG are full-time employees of Medtronic. BK (or his institution) received research support from Medtronic to conduct the bench testing. WA and ZV are paid consultants to Medtronic. Per Medtronic internal publication procedure, any undue influence, contribution or review from Medtronic employees who could indirectly benefit from publication of this work was prohibited. No one except the authors was entitled to approve for submission.

Ethical approval

IRB approval was obtained for the human subject portion of this study from the Western Institutional Review Board and the Timpanogos Regional Hospital’s Institutional Review Boards. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardian prior to any study procedures. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

King, B., Dove, J., McGonigle, S.J. et al. Identifying performance differences between two pulse oximetry systems in simulated critical neonatal conditions. J Perinatol 45, 1608–1614 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02364-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02364-4