Abstract

Despite the well-established adverse impact of del(11q) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the prognostic significance of somatic ATM mutations remains uncertain. We evaluated the effects of ATM aberrations (del(11q) and/or ATM mutations) on time-to-first-treatment (TTFT) in 3631 untreated patients with CLL, in the context of IGHV gene mutational status and mutations in nine CLL-related genes. ATM mutations were present in 246 cases (6.8%), frequently co-occurring with del(11q) (112/246 cases, 45.5%). ATM-mutated patients displayed a different spectrum of genetic abnormalities when comparing IGHV-mutated (M-CLL) and unmutated (U-CLL) cases: M-CLL was enriched for SF3B1 and NFKBIE mutations, whereas U-CLL showed mutual exclusivity with trisomy 12 and TP53 mutations. Isolated ATM mutations were rare, affecting 1.2% of Binet A patients and <1% of M-CLL cases. While univariable analysis revealed shorter TTFT for Binet A patients with any ATM aberration compared to ATM-wildtype, multivariable analysis identified only del(11q), trisomy 12, SF3B1, and EGR2 mutations as independent prognosticators of shorter TTFT among Binet A patients and within M-CLL and U-CLL subgroups. These findings highlight del(11q), and not ATM mutations, as a key biomarker of increased risk of early progression and need for therapy, particularly in otherwise indolent M-CLL, providing insights into risk-stratification and therapeutic decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The protein kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) functions as a tumor suppressor, is activated in response to double-stranded DNA breaks, and plays a crucial role in DNA damage response [1]. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), somatic mutations in ATM have previously been reported in 7–16% of cases [2,3,4,5,6,7], while the ATM gene, located in the q-arm of chromosome 11, is recurrently deleted in 10–24% of patients [3, 5, 6, 8,9,10]. Although del(11q) has long been recognized as a marker of poor prognosis in CLL and patients carrying this chromosomal abnormality frequently present with lymphadenopathy, face a higher risk of progression, and generally have an inferior prognosis [8, 9, 11,12,13,14,15,16], there are currently conflicting data on whether mutations in ATM with or without del(11q) are indicative of a poor clinical outcome.

In separate studies from the UK Leukemia Research Fund CLL 4 trial, patients with ATM mutations treated with chemotherapy exhibited shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to ATM-wildtype patients, though the differences did not reach statistical significance [7, 17]. Of note, reduced survival was observed only in cases with biallelic ATM inactivation, defined as an ATM mutation combined with del(11q) [7, 17]. In contrast, Austen et al. demonstrated inferior OS and treatment-free survival in patients with ATM mutations [18], while Nadeu et al. identified ATM mutations, irrespective of del(11q), as a biomarker of shorter time-to-first-treatment (TTFT) but not OS in patients with CLL [4, 19]. More recently, Nguyen-Khac et al. observed that, although ATM mutations were associated with shorter PFS in univariable analysis, this association was lost in multivariable models when accounting for other recurrent CLL mutations [20]. Conversely, Hu et al. reported that ATM mutations remained a significant biomarker for shorter TTFT in both univariable and multivariable analyses in treatment-naive patients with CLL [21].

In a recent study, we investigated the prognostic impact of nine recurrently mutated genes, ATM not included, in a large well-annotated series of pre-treatment samples from 4580 patients with CLL [22]. We evaluated the relative clinical importance of mutations within each gene in the poor-prognostic immunoglobulin heavy variable (IGHV)-unmutated CLL (U-CLL) and the more favorable-prognostic IGHV-mutated CLL (M-CLL) subgroups separately, focusing on early-stage patients and TTFT. Notably, we reported that these recurrently mutated genes carry different prognostic impact depending on IGHV gene somatic hypermutation (SHM) status, indicating the need for a more compartmentalized strategy to enable tailored management and care for patients belonging to the M-CLL and U-CLL subgroups.

In the present investigation, which includes 3631 patients with CLL, we aimed to investigate the clinical impact of somatic mutations and/or deletions of ATM, with particular consideration of IGHV gene SHM status and other gene mutations associated with CLL prognosis, focusing primarily on early-stage patients. To our knowledge, this represents the largest study to date that investigates the prognostic implications of ATM dysfunction in this patient population, aiming to provide a comprehensive evaluation of its role in disease progression in relation to other genetic features.

Materials and methods

Patient cohort and clinicobiological characteristics

The present study included pre-treatment samples from 3631 patients with CLL collected from 22 European centers (Supplementary Table S1). This is a subset from the previously described cohort of 4580 patients for whom ATM mutational data was available [22]. The sample collection period spanned from 1996 to 2020 and the median time from diagnosis to sample collection was 3 months (IQR 0-34, data available for 3572 cases, 98.7%). The clinicobiological features of the analyzed cohort are outlined in Table 1 and are highly similar to those of the larger cohort, with no statistically significant differences [22]. In summary, the patients had a median age of 64.7 years at diagnosis, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1 (63% male). Moreover, 2604 patients (72%) were in Binet stage A, 1502 (44%) were categorized as U-CLL, and 2122 patients (58%) required treatment during follow-up of which the majority were treated with either chemotherapy (41%) or chemoimmunotherapy (38%) at first line, while only 1% received targeted therapy. All cases were diagnosed according to the iwCLL guidelines [23]. Informed consent was obtained according to the Helsinki declaration and the study was approved by the local Ethics Review Committees.

Mutational analysis and variant classification

All cases had previously been assessed for coding sequence mutations in BIRC3, EGR2, MYD88, NFKBIE, NOTCH1, POT1, SF3B1, TP53, and XPO1 [22]. Mutation screening for ATM was conducted using next-generation sequencing (NGS) in >99% of cases, primarily through the utilization of targeted gene panel sequencing, while only 22 cases were analyzed by Sanger sequencing or resequencing arrays (Supplementary Table S1). For cases investigated using NGS-based methods, sequence alignment, variant calling and annotation were performed at each participating center using a variant allele frequency (VAF) threshold of ≥5% to classify mutated cases. Additionally, polymorphic variants with a max population allelic frequency of ≥1% in the gnomAD database (v4.0) [24] were excluded, and the remaining variants were further filtered to only retain exonic non-synonymous variants and small insertions or deletions. All ATM variants are reported based on the reference transcript NM_000051.3/ENST00000278616.8 (GRCh37).

ATM data were available from paired tumor/germline samples for 427 cases (11.8%), while tumor-only data were obtained for the remaining 3204 cases. Since the majority of sequencing results were derived from tumor-only analyses, capturing both somatic and germline variants, a hierarchical ranking system was implemented to classify all variants into categories of putative somatic or putative rare germline/predicted neutral (Fig. 1A). The classification of these variants was based on their max population allelic frequency ( > 0.001) in the gnomAD database (v4.0) [24], annotation in ClinVar [25], OnkoKB [26, 27], variant type (nonsense/frameshift or missense), pathogenicity predictions by AlphaMissense [28] and CADD (v1.7) [29], as well as data from CLL datasets with available germline information [2, 30, 31], and is detailed in Supplementary Table S2. For patients with multiple reported ATM variants, the variant with the highest hierarchical rank was assigned to each patient for subsequent analyses. If multiple variants fell within the same tier of the hierarchy, the variant with the highest VAF was prioritized.

A Hierarchical flowchart used to assign ATM variants to putative ‘germline/neutral’ or ’somatic/mutated’ categories. B Distribution of variant allele frequencies (VAFs) for ATM variants in each flowchart category, bar chart shows the proportion del(11q) positive cases for each category. C Distribution of VAFs for all variants assigned as ‘germline/neutral’ and ‘somatic/mutated’. D Graphical representation of amino acid changes and frequencies for all ATM variants in the cohort. Putative somatic variants are displayed above and putative germline/predicted neutral variants are shown below. *Confirmed germline by sequencing in published datasets [30, 31] and in unpublished data. **Four ATM variants, each observed in multiple patients and variably classified as either germline/neutral or somatic/mutated depending on the final step of the classification system, were reviewed and reassigned to a single classification category (Supplementary Table S2).

The IGHV gene SHM status was available for 3402/3631 (93.7%) patients and was assessed using PCR amplification and sequence analysis of IGHV-IGHD-IGHJ gene rearrangements, utilizing a 98% identity threshold to germline sequences to define M-CLL (<98% identity) and U-CLL (≥98% identity) patients as previously described [32, 33]. Chromosomal aberrations were identified primarily through fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and targeted probes for chromosomes 13q, 11q, 17p and 12 [11].

Statistical analysis

Correlations between ATM mutational status and clinicobiological variables were assessed using the chi-squared test. Two-sided Fisher’s exact tests were performed to assess co-occurrence of genomic alterations and p values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method for multiple testing. The primary endpoint for survival analysis was TTFT, calculated from the date of diagnosis until date of initial treatment or date of administrative censoring or death if untreated, with a median follow-up of 5.1 years (95% CI 4.7–5.5) and was available for 3598/3631 (99.1%) patients. Additionally, OS was assessed, calculated from the date of diagnosis to either the date of death or last follow-up. The cohort had complete OS data for all patients, with a median follow-up time of 13 years (95% CI, 12.2–13.6 years). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated to evaluate the effects of ATM mutations and/or del(11q) on TTFT and OS. Pairwise comparisons were performed to determine differences between subgroups by employing the Cox–Mantel log-rank test and p values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to account for multiple comparisons. Multivariable analyses using Cox proportional hazards models were employed to assess the prognostic strength of individual biomarkers. All statistical analyses were performed in R (v4.4.1) [34] and R studio (version 2024.04.0 + 735) [35]. Plots were created using ggplot2 (version 3.5.1), survminer (version 0.4.9), ComplexHeatmap (version 2.20.0) and Maftools (version 2.20.0) [36].

Results

Hierarchical ranking of somatic and germline ATM variants

A total of 445 ATM variants were identified across 362 patients in the cohort studied following mutational analysis and initial variant filtering. Among these, 309 variants (69%) were classified as putative somatic using our proposed hierarchical ranking system for ATM variant classification. To validate this approach, we reclassified all confirmed somatic mutations in samples with available germline information. Of the 27 confirmed somatic ATM mutations, 25 were consistently classified as somatic, while 2 were reclassified as predicted neutral based on multiple pathogenicity scores suggesting a neutral impact (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, among variants reported as rare germline based on prior studies, only 3/55 were predicted to be pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to the ClinVar database, all three cases harbored del(11q) on the alternate allele.

As the next step, we plotted the VAFs for all variants assigned to each category in the flowchart (Fig. 1B). Variants classified as putative germline/predicted neutral typically had VAFs centered around 50%, whereas putative somatic mutations displayed a broader distribution with the majority falling below 50% (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S2). These distinct VAF patterns became even more pronounced when pooling all samples with putative germline/predicted neutral or putative somatic mutations (Fig. 1C). Notably, variants with VAFs >50% were most often observed in tumors also harboring del(11q) (Fig. 1B, C). We identified 17 ATM variants classified as putative somatic with VAFs >60% in patients without del(11q) (Supplementary Table S2). For three of these cases heterozygosity status was available, revealing copy number-neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH) in all. For all subsequent analyses, all predicted germline/neutral ATM variants were re-categorized as ATM wildtype.

Frequency of ATM mutations and association with clinicobiological features

Based on our classification, ATM mutations were identified in 246/3631 (6.8%) patients, with 57 (23.2%) of these individuals carrying more than one ATM mutation. The mutations were distributed across the entire coding sequence of the ATM gene, with the p.R3008C (n = 7, collectively p.R3008C/H/L/S n = 13) and the p.K468fs (n = 10) as the most frequently affected positions (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, somatic missense mutations were primarily clustered toward the C-terminal region of the ATM protein, defined as the start of the FAT domain, while in contrast, somatic nonsense mutations were predominantly located in the N-terminal region (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. S1). Putative germline/neutral variants were evenly distributed throughout the entire length of the ATM protein (Fig. 1D).

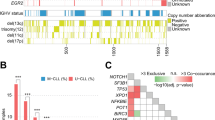

By combining our findings on ATM with sequencing data for nine other commonly mutated genes in CLL [22], ATM emerged as the fourth most frequently mutated gene, following NOTCH1, SF3B1, and TP53 (Fig. 2A). Mutations in ATM frequently co-occurred with other gene mutations, observed in 134 of 246 cases (54%). Among these, mutations in SF3B1 were the most common co-existing event, identified in 56 cases (23%, Fig. 2B). On the contrary, mutations in TP53 and MYD88 were rare occurrences in cases with ATM mutations, displaying mutual exclusivity (Fig. 2B, C). As expected, ATM mutations frequently co-occurred with del(11q) (112/246, 45.5%, Fig. 2B, C), while among cases with del(11q) (430/3631 cases, 11.8%), 112/430 (26.0%) carried ATM mutations. In addition, ATM mutations were significantly more frequent in U-CLL compared to M-CLL (p < 0.001), in patients with advanced stage at diagnosis (p < 0.001) and in those eventually in need of treatment (p < 0.001, Table 2). Notably, in U-CLL, ATM mutations were mutually exclusive with trisomy 12 and TP53 mutations (Fig. 3A, B), while SF3B1 and NFKBIE mutations were enriched in M-CLL (Fig. 3C, D).

A Overview of all 3631 CLL cases included in the study, sorted by frequency of mutations in 10 recurrently mutated genes. B Oncoplot showing detected mutations in recurrently mutated genes, IGHV somatic hypermutation status and chromosomal aberrations in 246 ATM-mutated cases. C Co-occurrence of recurrent gene mutations and chromosomal aberrations in the entire cohort. Odds ratios (OR) and BH-adjusted p values derived from two-sided Fisher exact tests. OR 0–1 indicates a trend towards mutual exclusivity, OR > 1 indicates a trend towards co-occurrence. U-CLL, CLL with unmutated IGHV genes, M-CLL, CLL with mutated IGHV genes.

A Oncoplot and (B) co-occurrence plot displaying recurrently mutated genes and chromosomal aberrations in 1502 U-CLL cases. C Oncoplot and (D) co-occurrence plot with recurrently mutated genes and chromosomal aberrations in 1900 M-CLL cases. Odds ratios (OR) and BH-adjusted p values derived from two-sided Fisher exact tests. OR 0–1 indicates a trend towards mutual exclusivity, OR > 1 indicates a trend towards co-occurrence. U-CLL CLL with unmutated IGHV genes, M-CLL CLL with mutated IGHV genes.

ATM aberrations and clinical outcome

We first evaluated the clinical impact of our ATM variant classification. Patients with putative germline/predicted neutral variants showed no significant differences in TTFT compared to ATM-wildtype cases while in contrast, cases with somatic ATM mutations displayed significantly shorter TTFT (Supplementary Fig. S2A–C). Results were also consistent when stratifying by del(11q) or limiting to Binet A cases (Supplementary Figs. S2D–F and S3), validating our re-categorization of germline/neutral variants with ATM-wildtype cases.

We assessed the clinical impact of ATM aberrations on TTFT by investigating del(11q), ATM mutations as well as bi-allelic ATM abnormalities (del(11q) and ATM mutations) independently in Binet A patients (2604/3631, 72% of the cohort). Here, any type of ATM abnormality resulted in significantly shorter TTFT when compared to ATM-wildtype cases (Fig. 4A). Among those with ATM mutations, no differences were detected when comparing missense versus nonsense/frameshift mutations (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S4) or when comparing mutations located in the C- versus N-terminal (Supplementary Fig. S5). We also investigated whether carrying multiple ATM mutations, as opposed to a single mutation, affected clinical outcome and found no evidence for a shorter TTFT in the overall cohort or in Binet A cases specifically (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. S6).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis using TTFT subdivided by (A) ATM aberration; somatic ATM mutation only, del(11q) only and combined ATM mutation and del(11q), (B) type of ATM mutation; frameshift/nonsense, missense/inframe indels with del(11q) displayed separately, and (C) comparing one versus multiple ATM mutations with del(11q) displayed separately.

As we previously have shown that the prognostic impact of recurrent gene mutations in CLL is highly dependent on IGHV gene SHM status [22], we investigated if ATM mutations affected clinical outcome when patients were stratified into the U-CLL and M-CLL subgroups, again focusing primarily on Binet stage A CLL. Among patients with unmutated IGHV genes, only those carrying del(11q) but not ATM mutations had a significantly inferior TTFT when compared to ATM-wildtype cases (Fig. 5A). The same analysis in M-CLL cases revealed instead that any ATM abnormality, either mono-allelic, with or without del(11q) or bi-allelic, resulted in significantly shorter TTFT (Fig. 5B).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis using TTFT in Binet stage A in (A) U-CLL and (B) M-CLL patients. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Cox–Mantel log-rank test. C Multivariable analysis using TTFT in Binet stage A CLL patients with U-CLL and M-CLL. U-CLL, CLL with unmutated IGHV genes, M-CLL, CLL with mutated IGHV genes. CI95, 95% confidence interval; * indicates a p value < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

Since mutations in ATM and SF3B1 often co-occurred, we also assessed if these aberrations in combination further affected TTFT. We noted no significant difference when comparing those carrying aberrations in ATM with or without an additional SF3B1 mutation (Supplementary Fig. S7). Furthermore, isolated ATM mutations (without other poor prognostic genetic markers) were rare, occurring in 1.2% of all Binet A cases and in 0.7% of Binet A M-CLL cases specifically. Of note, in Binet A patients, isolated ATM mutations did not have a significant impact on TTFT in either the U-CLL or M-CLL subgroups (Supplementary Fig. S8).

As the next step, we aimed to assess the specific contribution of ATM mutations on TTFT by employing a multivariable model. In addition to ATM mutations, the model included nine recurrently mutated genes [22], patient gender, age at diagnosis, del(11q) and trisomy 12 status, and IGHV gene SHM status. Patients carrying somatic mutations in TP53, or harboring del(17p), were combined as TP53 aberrant, while only cases carrying the hotspot mutation p.Y254fs/p.254* were considered mutated for NFKBIE [22]. Among Binet A cases, IGHV gene SHM status was the strongest significant biomarker of shorter TTFT, exhibiting the highest hazard ratio (Supplementary Fig. S9). In addition, mutations in SF3B1, EGR2, XPO1, TP53 aberrations, trisomy 12 and del(11q), but not ATM mutations, independently predicted shorter TTFT (Supplementary Fig. S9). In separate multivariable models for Binet A patients, stratified by IGHV status, mutations in SF3B1, TP53 aberrations, del(11q), trisomy 12 as well as EGR2 mutations were the only significant independent variables in U-CLL (Fig. 5C). For M-CLL patients, mutations in SF3B1, NOTCH1, XPO1, EGR2, trisomy 12 as well as del(11q) were significant biomarkers (Fig. 5C). ATM mutations had no independent significant effect on TTFT in either model.

Finally, we investigated the impact of different types of ATM mutations on OS across the entire cohort. Patients were stratified into four distinct groups based on their ATM status: ATM-wildtype, ATM-mutated, those carrying del(11q), and patients with biallelic alterations (del(11q) and ATM mutations). Any ATM aberration was associated with significantly reduced OS in the entire cohort and specifically among M-CLL patients. In contrast, within the U-CLL subgroup, only patients with del(11q) showed a significantly inferior outcome compared to those with wildtype ATM (Supplementary Fig. S10A–C). In multivariable analysis, del(11q), but not ATM mutations, emerged as a significant predictor of OS (Supplementary Fig. S10D–F).

Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic significance of ATM mutations in CLL and their impact within the context of IGHV gene SHM status and other CLL-associated gene mutations, using data from a large, well-characterized, multi-center European cohort. Given that a large proportion of cases in the studied cohort included tumor-only data, we developed a hierarchical ranking system which integrates published data from databases on both cancer-associated variants and variants present in normal populations, enabling the classification of mutations as putative somatic or germline/neutral. Using our classification, we could accurately assign variants in samples within our dataset with available germline information. Putative somatic variants exhibited markedly different VAF distributions compared to those classified as putative germline or predicted neutral, with the majority of somatic variants showing frequencies <50% while those with VAFs >50% were most often detected in patients with del(11q). Notably, we identified 17 variants classified as putative somatic in patients without del(11q), all exhibiting VAFs >60%. In three of these cases, the elevated VAFs were attributable to cnLOH, consistent with what has been previously reported in CLL [37]. Finally, in concordance with a previous report, somatic missense mutations were predominantly found at the C-terminal domains while frameshift and nonsense mutations mainly affected the N-terminal [38].

We used TTFT as the primary clinical endpoint to evaluate how our classification of ATM variants affected clinical outcome and found cases harboring putative somatic variants to have a significantly inferior outcome in univariate analyses compared to those carrying putative germline/neutral variants, with the latter group exhibiting results comparable to those of ATM-wildtype cases. While our flowchart seems to effectively distinguish patients with somatic mutations from those classified as germline/putatively neutral in our analysis of TTFT, we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that some of the variants classified as somatic might be rare pathogenic germline mutations or that variants classified as neutral may in fact impact prognosis through disruption of normal ATM function. Additionally, selected germline variants excluded from our analysis may still influence tumor development in CLL, as suggested by recent publications [30, 31]. Ultimately, as a result of our classification, 246/3631 (6.8%) patients of our cohort had ATM mutations, while 57/246 cases (23.2%) carried multiple ATM mutations. The frequency observed is slightly lower than reported in previous studies and might be attributed to differences in classification strategies and the potential inclusion of germline or predicted neutral variants in other studies.

We noted that mutations in ATM often co-occurred with other recurrent abnormalities in CLL, predominantly del(11q) (45.5%) and SF3B1 mutations (23%). The former combination is well-known in CLL [7, 18, 39, 40], but the latter has also been reported previously in CLL, where both these mutations are suggested to be late-occurring CLL driver events [3, 19]. Interestingly, the combination of ATM deletions and SF3B1 mutations results in a CLL-like disease in elderly mice leading to genome instability, dysregulation of CLL-associated processes and providing mechanistic evidence for disease development [41].

We observed distinct patterns of co-occurrence or mutual exclusivity among ATM-mutated patients when stratified by IGHV gene SHM status. In samples harboring ATM mutations, trisomy 12 and TP53 mutations were found to be mutually exclusive in the U-CLL subgroup, while instead, SF3B1 mutations were enriched in the M-CLL subgroup. Focusing specifically on Binet A cases, which amounted to almost three-quarters of the cohort (72%, 2604 patients), isolated ATM mutations were a very rare finding detected only in 1.3% of cases and in 0.7% of M-CLL cases. This suggests that ATM mutation alone, excluding del(11q), may not be a key driver of CLL progression, in contrast to what is known about the relationship between TP53 mutation and del(17p) [42].

In order to explore the relevance of mono- and bi-allelic abnormalities of the ATM gene, we evaluated the clinical impact of ATM aberrations by separately analyzing del(11q), ATM mutations, and bi-allelic ATM abnormalities in Binet A patients. In this analysis, any type of ATM abnormality resulted in inferior outcome compared to wildtype cases. More interestingly, differences became more evident when we investigated U-CLL and M-CLL subgroups separately. In Binet stage A U-CLL patients, only isolated del(11q) resulted in inferior TTFT when compared to ATM-wildtype cases. Here, bi-allelic ATM abnormalities were not significant, possibly explained by the relatively low number of cases. On the contrary, the same analysis in M-CLL cases revealed instead that any ATM abnormality, either mono-or bi-allelic, resulted in significantly shorter TTFT. Of note, harboring multiple ATM mutations compared to a single mutation did not result in inferior TTFT in the entire cohort or in Binet A cases only. Additionally, TTFT analysis revealed no differences when comparing somatic missense to nonsense/frameshift mutations, when investigating C- versus N-terminal mutations or analyzing mutations in ATM with or without an additional SF3B1 mutation.

As most patients with ATM mutations also carried other genetic alterations, we assessed the specific contribution of ATM mutations, independent of del(11q), on TTFT by employing a multivariable model in Binet A cases stratified by IGHV status. We found that in U-CLL, del(11q) and not ATM mutations were an independent marker of TTFT, suggesting that ATM mutations alone do not independently contribute to disease progression. Notably, del(11q) was a highly significant marker for TTFT, adding similar risk as SF3B1 mutations or TP53 abnormalities. For M-CLL cases, again del(11q) but not ATM mutations was a highly significant marker for TTFT, similar to SF3B1 mutations. These findings highlight the prognostic impact of this aberration for both subgroups of patients. Similar findings were observed when analyzing OS, with ATM mutations emerging as a significant biomarker of poor prognosis in univariable models. However, in multivariable models, whether applied to the entire cohort or stratified by IGHV status, del(11q), but not ATM mutations, was identified as a significant predictor of OS. These latter results should however be interpreted with caution, given the substantial variability in treatment strategies among patients from the different participating centers.

The current retrospective study has several limitations which mainly arise from the multi-center composition of the cohort. Even though a significant proportion of patient samples were sequenced using targeted gene panels, a smaller subset underwent whole-genome (WGS) or whole-exome sequencing (WES) contributing to methodological variability. Additionally, for cases sequenced using NGS-based techniques, sequence alignment, variant calling, annotation and initial variant filtering were conducted independently at each participating center. Moreover, most samples were derived from unsorted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and although unpurified CLL samples generally have high tumor content (>80%), mutations with VAFs near the 5% threshold could be missed, potentially underestimating the number of mutated cases. Finally, the proportion of cases requiring treatment seems slightly higher than in other published cohorts [43,44,45], likely explained by the long follow-up period (median 13 years) and the inclusion of samples from a clinical trial cohort.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that del(11q) significantly influences TTFT in CLL, impacting both the U-CLL and M-CLL subgroups. In contrast, somatic ATM mutations do not appear to have an independent prognostic impact in CLL. Isolated ATM mutations were rare, especially in M-CLL. Instead, ATM mutations often co-occurred with other poor-prognostic biomarkers, particularly del(11q) and SF3B1 mutations. Although del(11q) is strongly associated with a shorter TTFT, patients with this genetic aberration treated with chemoimmunotherapy can overcome the poor prognosis linked to del(11q), achieving prolonged OS [10]. Similar results are observed in ibrutinib-treated patients, where those with del(11q) were suggested to have a significantly longer PFS compared to patients without del(11q) [46,47,48]. Furthermore, relapsed/refractory patients with CLL carrying del(11q) were also shown to benefit from the combination venetoclax-rituximab compared to those receiving bendamustine and rituximab therapy [49]. These results highlight the need for large-scale, uniform cohort studies to better understand the overall prognostic and predictive roles of not only del(11q) and ATM mutations, but also other recurrent genetic abnormalities in CLL. Based on current evidence, we propose that del(11q), but not ATM mutations, should be considered a key factor in identifying patients at high risk for early disease progression and in determining therapeutic strategies. This is particularly important in the M-CLL subgroup, where del(11q) along with other recurrent mutations can help identify outlier cases with a poor prognosis despite otherwise indolent features.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lee J-H, Paull TT. Cellular functions of the protein kinase ATM and their relevance to human disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:796–814.

Puente XS, Beà S, Valdés-Mas R, Villamor N, Gutiérrez-Abril J, Martín-Subero JI, et al. Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2015;526:519–24.

Landau DA, Tausch E, Taylor-Weiner AN, Stewart C, Reiter JG, Bahlo J, et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 2015;526:525–30.

Nadeu F, Delgado J, Royo C, Baumann T, Stankovic T, Pinyol M, et al. Clinical impact of clonal and subclonal TP53, SF3B1, BIRC3, NOTCH1, and ATM mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2122–30.

Knisbacher BA, Lin Z, Hahn CK, Nadeu F, Duran-Ferrer M, Stevenson KE, et al. Molecular map of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and its impact on outcome. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1664–74.

Robbe P, Ridout KE, Vavoulis DV, Dréau H, Kinnersley B, Denny N, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of chronic lymphocytic leukemia identifies subgroups with distinct biological and clinical features. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1675–89.

Skowronska A, Parker A, Ahmed G, Oldreive C, Davis Z, Richards S, et al. Biallelic ATM inactivation significantly reduces survival in patients treated on the United Kingdom Leukemia Research Fund Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia 4 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4524–32.

Gunnarsson R, Isaksson A, Mansouri M, Goransson H, Jansson M, Cahill N, et al. Large but not small copy-number alterations correlate to high-risk genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a high-resolution genomic screening of newly diagnosed patients. Leukemia. 2010;24:211–5.

Gunnarsson R, Mansouri L, Isaksson A, Göransson H, Cahill N, Jansson M, et al. Array-based genomic screening at diagnosis and during follow-up in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:1161–9.

Goy J, Gillan TL, Bruyere H, Huang SJT, Hrynchak M, Karsan A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with deletion 11q have a short time to requirement of first-line therapy, but long overall survival: results of a population-based cohort in British Columbia, Canada. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:382–9.

Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–6.

Van Dyke DL, Werner L, Rassenti LZ, Neuberg D, Ghia E, Heerema NA, et al. The Dohner fluorescence in situ hybridization prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): The CLL Research Consortium experience. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:105–13.

Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, James MR, Benner A, Weilguni T, Bentz M, et al. 11q deletions identify a new subset of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia characterized by extensive nodal involvement and inferior prognosis. Blood. 1997;89:2516–22.

Stilgenbauer S, Bullinger L, Lichter P, Dohner H. Genetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: genomic aberrations and V(H) gene mutation status in pathogenesis and clinical course. Leukemia. 2002;16:993–1007.

Stankovic T, Skowronska A. The role of ATM mutations and 11q deletions in disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:1227–39.

Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Wang X, Faderl S, Ferrajoli A, Do KA, et al. Multivariable model for time to first treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4088.

Blakemore SJ, Clifford R, Parker H, Antoniou P, Stec-Dziedzic E, Larrayoz M, et al. Clinical significance of TP53, BIRC3, ATM and MAPK-ERK genes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: data from the randomised UK LRF CLL4 trial. Leukemia. 2020;34:1760–74.

Austen B, Powell JE, Alvi A, Edwards I, Hooper L, Starczynski J, et al. Mutations in the ATM gene lead to impaired overall and treatment-free survival that is independent of IGVH mutation status in patients with B-CLL. Blood. 2005;106:3175–82.

Nadeu F, Clot G, Delgado J, Martín-García D, Baumann T, Salaverria I, et al. Clinical impact of the subclonal architecture and mutational complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:645–53.

Nguyen‐Khac F, Baron M, Guièze R, Feugier P, Fayault A, Raynaud S, et al. Prognostic impact of genetic abnormalities in 536 first‐line chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients without 17p deletion treated with chemoimmunotherapy in two prospective trials: Focus on IGHV‐mutated subgroups (a FILO study). Br J Haematol. 2024;205:495–502.

Hu B, Patel KP, Chen HC, Wang X, Luthra R, Routbort MJ, et al. Association of gene mutations with time-to-first treatment in 384 treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2019;187:307–18.

Mansouri L, Thorvaldsdottir B, Sutton LA, Karakatsoulis G, Meggendorfer M, Parker H, et al. Different prognostic impact of recurrent gene mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia depending on IGHV gene somatic hypermutation status: a study by ERIC in HARMONY. Leukemia. 2023;37:339–47.

Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131:2745–60.

Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature. 2023;625:92–100. 2023 625:7993

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, Jang W, Rubinstein WS, Church DM, et al. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980–D985.

Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips S, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017:1–16.

Suehnholz SP, Nissan MH, Zhang H, Kundra R, Nandakumar S, Lu C, et al. Quantifying the expanding landscape of clinical actionability for patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:49–65.

Cheng J, Novati G, Pan J, Bycroft C, Žemgulytė A, Applebaum T, et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science. 2023;381:eadg7492.

Sc HubacHM, Maass T, Nazaretyan L, Röner S, Tin KirCHerM. CADD v1.7: using protein language models, regulatory CNNs and other nucleotide-level scores to improve genome-wide v ar iant predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52:1143–54.

Lampson BL, Gupta A, Tyekucheva S, Mashima K, Petráčková A, Wang Z, et al. Rare germline ATM variants influence the development of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1116–28.

Tiao G, Improgo MR, Kasar S, Poh W, Kamburov A, Landau DA, et al. Rare germline variants in ATM are associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31:2244–7.

Rosenquist R, Ghia P, Hadzidimitriou A, Sutton L-A, Agathangelidis A, Baliakas P, et al. Immunoglobulin gene sequence analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated ERIC recommendations. Leukemia. 2017;31:1477–81.

Agathangelidis A, Chatzidimitriou A, Chatzikonstantinou T, Tresoldi C, Davis Z, Giudicelli V, et al. Immunoglobulin gene sequence analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the 2022 update of the recommendations by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL. Leukemia. 2022;36:1961.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2024. https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 31 Oct2024).

Posit team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. 2024. http://www.posit.co/ (accessed 31 Oct2024).

Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28:1747–56.

Edelmann J, Holzmann K, Miller F, Winkler D, Bühler A, Zenz T, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals new recurrent genomic alterations. Blood. 2012;120:4783–94.

Barone G, Groom A, Reiman A, Srinivasan V, Byrd PJ, Taylor AMR. Modeling ATM mutant proteins from missense changes confirms retained kinase activity. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1222–30.

Navrkalova V, Sebejova L, Zemanova J, Kminkova J, Kubesova B, Malcikova J, et al. ATM mutations uniformly lead to ATM dysfunction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: application of functional test using doxorubicin. Haematologica. 2013;98:1124–31.

Austen B, Skowronska A, Baker C, Powell JE, Gardiner A, Oscier D, et al. Mutation status of the residual ATM allele is an important determinant of the cellular response to chemotherapy and survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia containing an 11q deletion. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5448–57.

Yin S, Gambe RG, Sun J, Martinez AZ, Cartun ZJ, Regis FFD, et al. A murine model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia based on B cell-restricted expression of Sf3b1 mutation and Atm deletion. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:283–296.e5.

Zenz T, Krober A, Scherer K, Habe S, Buhler A, Benner A, et al. Monoallelic TP53 inactivation is associated with poor prognosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a detailed genetic characterization with long-term follow-up. Blood. 2008;112:3322–9.

Chatzikonstantinou T, Scarfò L, Karakatsoulis G, Minga E, Chamou D, Iacoboni G, et al. Other malignancies in the history of CLL: an international multicenter study conducted by ERIC, the European Research Initiative on CLL, in HARMONY. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;65:102307.

Parikh SA, Rabe KG, Kay NE, Call TG, Ding W, Schwager SM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in young (≤ 55 years) patients: a comprehensive analysis of prognostic factors and outcomes. Haematologica. 2014;99:140–7.

Schlosser P, Schiwitza A, Klaus J, Hieke-Schulz S, vel Szic KS, Duyster J, et al. Conditional survival to assess prognosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2024;103:1613–22.

Kipps TJ, Fraser G, Coutre SE, Brown JR, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, et al. Long-term studies assessing outcomes of ibrutinib therapy in patients with Del(11q) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19:715–722.e6.

Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, Owen C, Ghia P, Tedeschi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study. Leukemia. 2020;34:787.

Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, Tedeschi A, Bairey O, Burger JA, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022;6:3440.

Seymour JF, Kipps TJ, Eichhorst BF, D’Rozario J, Owen CJ, Assouline S, et al. Enduring undetectable MRD and updated outcomes in relapsed/refractory CLL after fixed-duration venetoclax-rituximab. Blood. 2022;140:839.

Acknowledgements

This work was prepared on behalf of the European Research Initiative in CLL (ERIC) and the HARMONY Alliance. ERIC is a partner in the HARMONY Alliance, the EHA Specialized Working group on CLL and the ELN Work package 7 on CLL. This work was in part supported by; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro—AIRC, Milano, Italy (Investigator Grant #27566, P.I. Ghia Paolo) and Special Program on Metastatic Disease— 5 per mille #21198 program—P.I. Foà Roberto, G.L. Paolo Ghia, Gianluca Gaidano); ; “la Caixa” Foundation (Health Research 2017 Program HR17-00221); the American Association for Cancer Research (2021 AACR-Amgen Fellowship in Clinical/Translational Cancer Research, 21-40-11-NADE), the European Hematology Association (EHA Junior Research Grant 2021, RG-202012-00245), and the Lady Tata Memorial Trust (International Award for Research in Leukemia 2021- 2022, LADY_TATA_21_3223); the Hellenic Precision Medicine Network in Oncology; project ODYSSEAS (Intelligent and Automated Systems for enabling the Design, Simulation and Development of Integrated Processes and Products) implemented under the “Action for the Strategic Development on the Research and Technological Sector”, funded by the Operational Program “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014-2020) and co-financed by Greece and the European Union, with grant agreement no: MIS 5002462”; MHCZ—DRO (FNBr, 65269705), NV21-08-00237 and the project National Institute for Cancer Research (Program EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5102)—Funded by the European Union—Next- Generation EU; Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), “PI21/00983”, co-funded by the European Union; Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), “PI21/00983”, co- funded by the European Union; Fondo di Ateneo per la Ricerca (FAR) 2019, 2020 and 2021 of the University of Ferrara (GMR; AC), Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie- Linfomi e Mieloma ONLUS Ferrara (AC; GMR), BEAT Leukemia Foundation Milan Italy (AC); the Danish Cancer Society and the CLL-CLUE project under the frame of ERA PerMed; Cancer Research UK (ECRIN-M3 accelerator award C42023/A29370, Southampton Experimental Cancer Medicine Center grant C24563/A15581, Cancer Research UK Southampton Center grant C34999/A18087, and program C2750/ A23669); the Swedish Cancer Society (22 2448 Pj), the Swedish Research Council (2020-01750), Region Stockholm (ALF/FoUI-962423), and Radiumhemmets Forskningsfonder (194133), Stockholm; CGI-Clinics, a European Union’s Horizon 2022-2027 program under grant agreement 101057509.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BT and LM summarized, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the paper; BT performed bioinformatics/statistical analysis; MM, HP, FN, CB, SL, RM, DR, JK, JD, AER-V, RB, GMR, SB, LC, MaMa, ZD, PB, IR, FM, JM-L, JdlS, JMHR, MJL, MJC, KES, BE, AP, LB, FB, BT-V, FB-M, DO, FN-K, TZ, MJT, AC, MH-S, SP, KM, GG, CUN, EC and JCS provided samples, sequencing- and clinical data; PG, KS and RR designed the study, interpreted data and wrote the paper; all authors edited and approved the paper for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PG: Honoraria/advisory board: AbbVie, Acerta/AstraZeneca, Adaptive, ArQule/MSD, BeiGene, CelGene/Juno, Gilead, Janssen, Loxo/Lilly, Sunesis. Research funding: AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Sunesis; LS: advisory board AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen; RR: honoraria/advisory board: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Illumina, Janssen, Lilly and Roche; KS: honoraria/advisory board: AbbVie, Acerta/AstraZeneca, Gilead, Janssen. Research funding: AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen; PB: honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead and Janssen. Research funding from Gilead; GG: Advisory Board/Speaker’s bureau: Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Hikma, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly; LB: honoraria/advisory board: Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, BMS/Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Hexal, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics. Research funding: Bayer, Jazz Pharmaceuticals; GMR: honoraria from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Gilead and Janssen. Research funding from Gilead; CB: Honoraria/advisory board: AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly. CUN received research grants and/or honoraria from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Genmab, Beigene, Octapharma, MSD, Lilly, Synamics, CSL Behring, Takeda, Nofo Nordisk Foundation. The other authors declare no competing financial interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thorvaldsdottir, B., Mansouri, L., Sutton, LA. et al. ATM aberrations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: del(11q) rather than ATM mutations is an adverse-prognostic biomarker. Leukemia 39, 1650–1660 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02615-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-025-02615-5