Abstract

Accurate recognition of low-contrast targets in complex visual environments is essential for advanced intelligent machine vision systems. Conventional photodetectors often suffer from a weak photoresponse and a linear dependence of photocurrent on light intensity, which restricts their ability to capture low-contrast features and makes them susceptible to noise. Inspired by the adaptive mechanisms of the human visual system, we present a molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) phototransistor with tunable sensitivity, in which the gate stack incorporates a heterostructure diode—composed of O-plasma-treated MoS2 and pristine MoS2—that serves as the photosensitive layer. This configuration enables light-intensity-dependent modulation of the diode’s conductance, which dynamically in turn alters the voltage distribution across the gate dielectric and transistor channel, leading to a significant photoresponse. By modulating the gate voltage, the light response range can be finely tuned, maintaining high sensitivity to low-contrast targets while suppressing noise interference. Compared to conventional photodetectors, the proposed device achieves a 1000-fold improvement in sensitivity for low-contrast signal detection and exhibits significantly enhanced noise immunity. The intelligent machine vision system built on this device demonstrates exceptional performance in detecting low-contrast targets, underscoring its promise for next-generation machine vision applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intelligent machine vision applications, such as precision guidance, smart surveillance, and early warning systems, demand sensors that can generate significant and substantial electrical responses to faint variations in light intensity under complex lighting conditions1,2,3,4. However, conventional photodetectors based on photodiodes and phototransistors mainly rely on photogenerated carriers within junctions or channels to produce photocurrents5. Due to their weak photoresponse and the linear relationship between photocurrent and light intensity, these devices are inherently limited in their ability to capture the features of targets in low-contrast scenes and are highly susceptible to optical noise. To address these limitations, neuromorphic vision devices often employ long exposure times or repetitive imaging to enhance target contrast and suppress noise6,7,8,9. Nevertheless, such strategies struggle to accommodate rapidly changing scenes. Dynamic vision sensors (e.g., those proposed by Yang et al.) leverage combinations of multiple photodetectors and complex circuit architectures to extract image edge features10. However, these approaches unavoidably increase system complexity. Consequently, designing efficient and compact photodetectors capable of detecting low-contrast targets in challenging environments remains a significant challenge.

In the human visual system, the mechanism of light adaptation enables visual perception across complex lighting conditions (Fig. 1a). Specifically, cone cells and rod cells in the retina are responsible for detecting bright and dim light, respectively, and their sensitivities are dynamically tuned according to ambient light intensity11,12. Photoreceptive proteins, such as rhodopsin and photopsin, undergo synthesis or decomposition in response to changes in light intensity (Fig. 1a). This adaptive mechanism allows the human eye to achieve a global dynamic range exceeding 160 dB (a light intensity difference of approximately 108 times) while maintaining a local dynamic range of 40 dB (a light intensity difference of approximately 102 times) under specific conditions (Fig. 1b)13,14,15. By focusing on relative differences in light intensity rather than absolute illumination levels, the retina excels in recognizing low-contrast targets. Furthermore, it suppresses irrelevant noise signals outside specific intensity ranges, enhancing feature detection in complex dynamic environments. In contrast, conventional photodetectors lack such adaptive sensitivity, limiting their effectiveness in noise suppression and low-contrast detection (Fig. 1b).

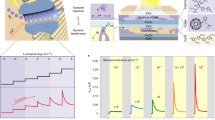

Bioinspired photodetector with tunable sensitivity. a The retina achieves efficient visual perception under varying illumination conditions through light adaptation. Rod and cone cells adjust their sensitivity via the synthesis and degradation of rhodopsin and photopsins. With increasing light intensity, retinal in rhodopsin and photopsins undergoes isomerization from 11-cis to all-trans, leading to the separation of retinal from opsins and the formation of inactive opsins. Cone cells express S/M/L opsins, which respond to short, medium, and long wavelength light, respectively. b Comparison of light responses among the retina, conventional photodetectors, and the bioinspired photodetector. Both the retina and the bioinspired photodetector enhance contrast and filter noise, whereas conventional photodetectors, limited by fixed sensitivity and a linear relationship between photocurrent and light intensity, struggle to effectively detect low-contrast targets

Mimicking the adaptive sensitivity of the human eye represents a promising strategy for achieving efficient low-contrast target detection. Compared to bulk materials, two-dimensional materials possess unique electrical and optoelectronic properties16,17,18, enabling the construction of van der Waals heterostructures with high detection sensitivity19,20,21,22,23.

Here, we report a molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) phototransistor with tunable sensitivity, wherein the key innovation lies in the integration of an oxygen plasma treated (O-plasma-treated) MoS2/MoS2 heterostructure diode as the photosensitive layer within the device gate. The dynamic adjustment of the diode’s electrical conductivity with light intensity alters the voltage distribution across the dielectric layer and channel of the transistor, resulting in a significant change in photoresponse. By modulating the gate voltage, the phototransistor achieves precise control over the photoresponse range, enabling high-sensitivity detection of low-contrast targets. Compared to conventional photodetectors, this device exhibits over 1000-fold improvement in detection sensitivity and demonstrates exceptional noise tolerance.

Results

Device design and characteristics

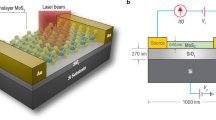

A tunable-sensitivity phototransistor was designed and fabricated using a layer-transfer method (Methods, Fig. S1). The device is based on a MoS2 field effect transistor (FET) with an O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 diode inserted within the gate stack. Specifically, graphite was used to form the Ohmic contact24, MoS2 as the channel, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) as the dielectric layer, and top and bottom protective layers. An O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 diode25,26,27was embedded between the h-BN dielectric layer and the bottom protective layer, serving as the photosensitive structure (Figs. 2a and S2). To elucidate the effects of O-plasma treatment on the composition and structure of MoS2, comprehensive characterizations of the MoS2 samples before and after treatment were performed. Cross-sectional high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) of the h-BN/MoS2/h-BN heterostructure reveals a well-defined layered structure. Mo and S are confined within the MoS2 layer, N aligns with h-BN, and oxygen is uniformly adsorbed on the cross-section (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the upper layer of the O-plasma-treated MoS2 becomes amorphous, confirmed by the presence of Mo, S, and O in energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping (Fig. 2c). For pristine MoS2, the S/Mo atomic ratio is approximately 1.95, consistent with the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results (Figs. 2d and S3), and the oxygen content is about 32%, mainly originating from adsorbed oxygen (Fig. S3). After oxygen plasma treatment, the total oxygen content in the sample increases significantly to 68%, with about 36% of the oxygen incorporated as lattice oxygen. Meanwhile, the Mo and S contents are around 18% and 14%, respectively, corresponding to an approximate molecular formula of MoO2S (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, plan-view HRTEM (Fig. S4), EDS (Fig. S4), and Raman characterizations (Fig. S5) further confirm the structural and compositional transition induced by O-plasma treatment.

Phototransistor with tunable sensitivity. a Schematic of the phototransistor, consisting of a MoS2 FET integrated with a photodiode. h-BN serves as both the dielectric and protective layer, while graphite is used as the contact and gate electrode. b Cross-section HRTEM image of the h-BN/MoS2/h-BN heterojunction and elemental maps of S, Mo, N, O for the heterojunction. c Cross-section HRTEM image of the Gr/ O-plasma-treated MoS2/h-BN heterojunction and elemental maps of S, Mo, N, C, O for the heterojunction. d, e O, S, and Mo atomic ratio for pristine and O-plasma-treated MoS2 samples. f Band structure of the device in the dark. g Band structure of the device under illumination. h Device symbol showing a diode inserted in the gate stack of the FET. i Transfer characteristics (IDS−VGS) of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor in dark and under varying 516-nm light intensities at VDS = 0.1 V

XPS valence band spectra reveal that the valence band maximum shifts from ~0.8 eV below the Fermi level in pristine MoS₂ to ~1.2 eV after plasma treatment (Fig. S6). Ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy measurements further show an increase in work function from ~4.3 eV for pristine MoS2 to ~4.7 eV O-plasma-treated MoS228. Theoretical calculations indicate that the bandgap widens with oxygen incorporation, increasing from 1.56 eV (MoS2) to 1.8 eV (MoO2S)29. Based on these experimental and theoretical results, schematic band diagrams for pristine and O-plasma-treated MoS2 were constructed (Fig. S7). The band alignment suggests the formation of a MoS2/O-plasma-treated MoS2 n/n− junction, which we experimentally validated by constructing both in-plane and vertical heterojunctions (Figs. S8 and S9). The working principle of the phototransistor with tunable sensitivity was shown in Fig. 2f, g. Under a negative gate bias (VGS), the O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 heterojunction is reverse-biased in the dark, causing most of the gate voltage to drop across the junction and keeping the MoS2 channel conductive (Figs. 2f and S10). Upon illumination, photogenerated carriers reduce the junction resistance, redistributing the gate voltage such that a larger portion is applied across the h-BN dielectric and MoS2 channel, thereby depleting the channel and turning the transistor off (Figs. 2g and S11). As the gate voltage becomes more negative, the voltage across the MoS2 channel increases further, enabling the device to shut off at lower light intensities, thus realizing tunable detection sensitivity. A new device symbol representing this structure is proposed (Fig. 2h).

Figure 2i shows the photoresponse behavior of the phototransistor. When the gate voltage is −2 V, the device shows only a slight current change at light intensities below 0.7 mW cm−2. However, within the light intensity range of 0.7–1.2 mW cm−2, the device exhibits a current change of nearly 107 times. In contrast, the current change in the O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 diode is only 1.6 times (Fig. S12). These demonstrate that our transistor can generate a non-linear relationship between photocurrent and light intensity, mimicking the retina system. To exclude the contribution of the MoS2 channel to the photocurrent, we conducted position-dependent illumination experiments, confirming that the dominant photoresponse originates from the O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 heterojunction (Fig. S13). In addition, the transistor behavior under light is different under different VGS, demonstrating a tunable photosensitivity by varying VGS.

Tunable-sensitivity optoelectronic characteristics

Figure 3 shows the detailed optoelectronic performance of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor. When a VGS of −9 V and a 100 ms light pulse are applied simultaneously, the device shows no obvious photoresponse when the light intensity is below 77 μW cm−2. However, when the light intensity further increases, the transistor current decreases abruptly. Once the light intensity surpasses 454 μW cm−2, the photoresponse of the device reaches saturation (Fig. 3a, b). This non-linear characteristic enables the device to effectively filter both strong-light and weak-light noise. In addition, by adjusting VGS, the device’s response range to light intensity can be tuned. For instance, when VGS = −7 V, the device exhibits a light response range of 392–1061 μW cm−2; whereas, at −5 V, the response range is adjusted to 748–2122 μW cm−2. Overall, the device can precisely distinguish light intensities within the range of 77–50000 μW cm−2 by changing VGS (Figs. 3b and S14).

Optoelectronic performance of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor. a Photo-response behavior of the device under 516-nm light pulses (pulse width: 100 ms) at varying light intensity (Pin) and gate voltage (VGS) pulse from 0 to −9 V (pulse width: 100 ms). VDS = 0.1 V. b Dependence of IDS on Pin under 516-nm light at different VGS. c Variation of the current ratio (tunable-sensitivity phototransistor: I0/Ilight; conventional phototransistor: Ilight/I0) as a function of the light intensity ratio (Pin/P0) at different VGS, where P0 represents the minimum detectable light intensity, and I0 is the corresponding current. d Comparison of responsivity (R = |ILight−IDark|/Pin) of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor and conventional phototransistor under different Pin

To further demonstrate the device’s ability to detect small changes in light intensity, we extracted the relationship between the current ratio and the light intensity ratio (Pin/P0) at different VGS (Fig. 3c). When the light intensity changes by 3–5 times, the current ratio of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor exceeds 104. In contrast, the current ratio of the conventional MoS2 phototransistor is about 5. This indicates that the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor has more than 1000 times higher capability in detecting small changes in light intensity compared to conventional photodetectors, and also outperforms previously reported gate-tunable phototransistors designed for contrast enhancement8,9,10,30,31,32,33,34,35 (Table S1). The tunable-sensitivity phototransistor also demonstrates a significantly higher responsivity compared to the conventional MoS2 phototransistor (Fig. 3d). Notably, as the light intensity increases, the responsivity of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor gradually decreases, which is similar to that of the human retina (Fig. 3d). In contrast, the conventional MoS2 phototransistor lacked this characteristic (Figs. 3d and S15).

Performance of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array

Figure 4a, b show a 3 × 3 photo sensor array based on tunable-sensitivity phototransistors, exhibiting good uniformity across all 9 transistors both in dark and under light conditions (Figs. 4c and S16). To demonstrate the ability to detect low-contrast targets, we input five sets of low-contrast signals of pattern “O” into both the conventional phototransistor array and the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array. The light-to-background intensity ratio of pattern “O” ranges from 1.2 to 2.1. For the conventional phototransistor array, the output current ratio is only 1.3 when the light-to-background intensity ratio is 1.2, and increases modestly to 1.7 at a ratio of 2.1, which is insufficient to produce a clear image. In contrast, the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array achieves a significantly higher current ratio of 3.4 under the same low-contrast condition (intensity ratio of 1.2), and up to 470 at an intensity ratio of 2.1, successfully enabling the recognition of a distinct “O” pattern. This demonstrates the superior performance of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor in low-contrast target detection (Fig. 4d). Additionally, the developed array exhibited outstanding noise filtering capability. When an image “L” with increasing surrounding noise is input to the conventional phototransistor array, the output image “L” gradually becomes blurred as the noise intensity increases, due to the wide response range of the conventional detector. In contrast, under a gate voltage of −5 V, the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array is selectively responsive to light intensities in the range of 748–2122 μW cm−2, making it immune to out-of-range light noise and allowing it to consistently produce a clear image (Fig. 4e).

Performance of tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array. a Optical image of a 3 × 3 phototransistor array (scale bar: 200 μm). b Magnified image of an individual sensor unit (scale bar: 10 μm). c IDS−VGS curves of the 9 phototransistors in dark and under 516-nm light at VDS = 0.1 V. d, e Comparison of input and output images, demonstrating the advantages of tunable-sensitivity phototransistor array in contrast enhancement (d) and noise filtering (e) compared with the conventional phototransistor arrays

Highly robust target recognition

The developed tunable-sensitivity phototransistor enables highly robust target recognition, demonstrated by integrating phototransistor arrays with an artificial neural network (ANN)-based intelligent machine vision system (Fig. 5a). An ANN model was employed to perform classification and recognition based on the image data generated by the phototransistor array. The ANN architecture consisted of an input layer, two hidden layers (the first with 128 neurons and the second with 64 neurons), and an output layer. The rectified linear unit (ReLU) was used as the activation function, and the cross-entropy function was used as the loss function. Conventional photodetectors capture all optical signals in the scene, making it challenging to distinguish low-contrast vehicle targets. On the other hand, by adjusting the gate voltage, our tunable-sensitivity phototransistor responds only to light signals within specific intensity ranges (Table S2). This capability allows accurate recognition of low-contrast vehicle targets in complex lighting conditions, whether under dim or bright lighting conditions, while effectively filtering out noise signals that interfere with target recognition.

Robust recognition of low-contrast targets. a Schematic of an intelligent machine vision system integrating tunable-sensitivity phototransistor arrays or conventional sensor arrays with an ANN. The tunable-sensitivity phototransistor enables precise extraction of low-contrast targets. b Imaging comparison using conventional phototransistor arrays and tunable-sensitivity phototransistor arrays. c Recognition accuracy of tunable-sensitivity phototransistors and conventional phototransistors after 100 training epochs at different average contrast conditions. d Tunable-sensitivity phototransistors exhibit high robustness in recognition under salt-and-pepper noise interference

For the low-contrast object recognition task, we selected 500 “bus” images from the CIFAR-100 dataset as positive samples, which were not included in the testing set. An additional 1000 images of other vehicles (e.g., motorcycles, bicycles, etc.) were selected as negative samples to establish a binary classification task (Methods). To evaluate the system’s ability to recognize low-contrast targets, we used 500 images of buses, each with a resolution of 32 × 32 pixels, that were not included in the training set as the test dataset. The test dataset consists of five sub-datasets, each containing 100 images, with the average image contrast gradually decreasing across the datasets (Figs. 5b and S17). Figure 5c shows the recognition accuracy after 100 training epochs for each dataset. The machine vision system based on the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor achieved an accuracy exceeding 90%. In contrast, the system based on conventional photodetectors achieved an accuracy close to zero (Fig. 5c).

To evaluate the reliability of the tunable-sensitivity phototransistor-based machine vision system under complex lighting conditions, we introduced salt-and-pepper noise with densities of 5%, 10%, 20% and 30% to 500 test images (Figs. 5b and S18). These 2000 noisy images were then input into the system for recognition. Even with a noise density of 30%, the system’s image recognition accuracy remained around 80% (Fig. 5d). These results highlight the superior robustness of our tunable-sensitivity phototransistor in low-contrast imaging, making it highly suitable for imaging tasks in complex lighting conditions.

Discussion

Inspired by the adaptive mechanism of the human retina, we developed a tunable-sensitivity MoS2 phototransistor by integrating an O-plasma-treated MoS2/MoS2 diode as the photosensitive layer within the gate stack. The device leverages the diode’s resistance variation with light intensity to adaptively adjust the voltage distribution across the channel, achieving a significant photoresponse. By tuning the gate voltage, the photoresponse range can be precisely controlled while maintaining high sensitivity to low-contrast targets within specific light intensity ranges. Compared to conventional photodetectors, the device demonstrates more than 1000-fold improvement in detecting low-contrast signals and significantly enhanced noise immunity. This innovation paves the way for the development of robust low-contrast target detection technologies in complex environments.

Materials and methods

Device fabrication

Step 1: Material preparation. Graphene, MoS2, and h-BN were exfoliated from bulk crystals using Scotch® tape and placed on a SiO2/Si substrate. Step 2: Heterostructure stacking. The h-BN as the top protective layer was picked up using a piece of propylene-carbonate (PPC), and the graphite as the source/drain electrodes, MoS2 as the channel, h-BN as the dielectric, MoS2 as the photosensitive layer, and h-BN as the bottom protective layer were then picked up in sequence. Step 3: Removing PPC. The stack was released at 130 °C on a surface of a 300-nm-thick SiO2 layer, which was grown on an n-doped silicon wafer (0.05-0.2 Ω·cm−1), followed by heating at 350 °C for 120 min in vacuum to remove the PPC. Step 4: Metal deposition. A polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) layer (495k MW, A4, MicroChem) was spin-coated at 2000 rpm on the substrate and baked at 190 °C for 5 min, and another PMMA layer (950k MW, A2, MicroChem) was then spin-coated at 4000 rpm and baked at 190 °C for 2 min. An undercut structure was created during the electron-beam lithography and developing processes. Subsequently, the h-BN on the graphite source/drain electrodes and MoS2 control group gate electrodes were removed using a reactive ion etching (CHF3 with a flux rate of 20 sccm; O2 with a flux rate of 4 sccm; pressure, 2.0 Pa; power, 100 W; etching time, 1 min). Then, metal contacts for source/drain (Ti/Au: 5/50 nm) and the control group gate were formed using electron-beam evaporation and lift-off processes. Step 5: O-plasma treatment of MoS2. The O-plasma-treated MoS2 was formed using an oxygen plasma treatment (O2 with a flux rate of 180 sccm; power, 200 W; time, 15 min) on the MoS2 gate without h-BN protection. Step 6: Gate formation. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was used as the medium to transfer the graphite layer onto the O-plasma-treated MoS2 to form the gate.

Characterization

Material and device characterizations were performed using an optical microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE LV100ND) and an AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon). Electrical and optoelectronic performance was measured using semiconductor analyzers (Agilent B1500A, Fs Pro, 100 kHz bandwidth), a probe station (Cascade M150), and a laser diode controller (Thorlabs ITC4001, with laser excitations of 516 nm) in a dark room at room temperature. The response time was measured using a semiconductor analyzer (Fs Pro, 100 kHz bandwidth).

Calculation of image contrast

Image contrast of grayscale images was calculated as36:

where θ(i,j) represents the grayscale difference between two neighboring pixels, and Pθ(i,j) denotes the probability distribution of the grayscale difference θ(i,j) across the image. In practical applications, the image is first expanded by adding a border of zero-grayscale pixels. Then, the grayscale differences between each pixel and its neighboring pixels (above, below, left, and right) are calculated.

Simulation of image recognition

An ANN was used to demonstrate the robustness of our sensor in detecting low-contrast targets. The optimal parameters were determined through multiple tests, as outlined below. The Flatten layer converts the input 32 × 32 image into a one-dimensional array, allowing it to be passed to the fully connected layers. The Dense layers consist of two layers: the first with 128 neurons and the second with 64 neurons, both employing the ReLU activation function. The output layer is a Dense layer with a sigmoid activation function. The validation split is set to 0.2, and the batch size is 25. Python was used to implement the ANN for recognition tasks. The CIFAR-100 database, shown in Fig. 5b, is an open-source dataset obtained from the website (https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html). The image pixels are 32 × 32, which meets the requirements of our hardware experimental measurements (Fig. 5b). Noise density = Nnoise/Ntotal, where Nnoise is the number of pixels randomly assigned to 0 or 255 (i.e., noisy pixels), and Ntotal is the total number of pixels in the image (32 × 32 = 1024 pixels).

Training process of ANN

Step 1: Forward propagation. Input images were passed through the network to generate predicted outputs. Step 2: Loss calculation. The predicted outputs were compared with ground-truth labels to compute the error. Step 3: Backpropagation. The network weights were updated based on the calculated error. Step 4: Optimization. The Adam optimizer was applied to perform gradient descent and iteratively minimize the loss.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhou, F. C. & Chai, Y. Near-sensor and in-sensor computing. Nat. Electron. 3, 664–671 (2020).

Chai, Y. In-sensor computing for machine vision. Nature 579, 32–33 (2020).

Ren, Q. Q. et al. Optoelectronic devices for in-sensor computing. Adv. Mater. 37, 2407476 (2025).

Long, Z. H. et al. Biomimetic optoelectronics with nanomaterials for artificial vision. Nat. Rev. Mater. 10, 128–146 (2025).

Wang, F. et al. How to characterize figures of merit of two-dimensional photodetectors. Nat. Commun. 14, 2224 (2023).

Roy, K., Jaiswal, A. & Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 575, 607–617 (2019).

Zhou, F. C. et al. Optoelectronic resistive random access memory for neuromorphic vision sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 776–782 (2019).

Zhu, Q. B. et al. A flexible ultrasensitive optoelectronic sensor array for neuromorphic vision systems. Nat. Commun. 12, 1798 (2021).

Liao, F. Y. et al. Bioinspired in-sensor visual adaptation for accurate perception. Nat. Electron. 5, 84–91 (2022).

Yang, Y. K. et al. In-sensor dynamic computing for intelligent machine vision. Nat. Electron. 7, 225–233 (2024).

Darmont, A. High Dynamic Range Imaging: Sensors and Architectures (SPIE, 2013).

Seetzen, H. et al. High dynamic range display systems. In Proc. ACM SIGGRAPH 2004 Papers 760–768 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2004).

Kalloniatis, M. & Luu, C. Light and dark adaptation. in Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System (eds Kolb, H. et al.) (University of Utah Health Sciences Center, 1995).

Burkhardt, D. A. Light adaptation and photopigment bleaching in cone photoreceptors in situ in the retina of the turtle. J. Neurosci. 14, 1091–1105 (1994).

Valeton, J. M. & van Norren, D. Light adaptation of primate cones: an analysis based on extracellular data. Vis. Res. 23, 1539–1547 (1983).

Long, M. S. et al. Progress, challenges, and opportunities for 2D material based photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1803807 (2019).

Konstantatos, G. Current status and technological prospect of photodetectors based on two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 5266 (2018).

Wu, P. S. et al. Next-generation machine vision systems incorporating two-dimensional materials: progress and perspectives. InfoMat 4, e12275 (2022).

Buscema, M. et al. Photocurrent generation with two-dimensional van der Waals semiconductors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3691–3718 (2015).

Liang, S. J. et al. Van der Waals heterostructures for high-performance device applications: challenges and opportunities. Adv. Mater. 32, 1903800 (2020).

Feng, S. et al. An ultrasensitive molybdenum-based double-heterojunction phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 12, 4094 (2021).

Zhang, Z. H. et al. All-in-one two-dimensional retinomorphic hardware device for motion detection and recognition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 27–32 (2022).

Wang, C. Y. et al. Gate-tunable van der Waals heterostructure for reconfigurable neural network vision sensor. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6173 (2020).

Feng, S. et al. A charge-coupled phototransistor enabling synchronous dynamic and static image detection. Adv. Mater. 37, 2417675 (2025).

Feng, S. et al. A photon-controlled diode with a new signal-processing behavior. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwac088 (2022).

Chen, M. K. et al. Stable few-layer MoS2 rectifying diodes formed by plasma-assisted doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 142110 (2013).

Dhall, R. et al. Charge neutral MoS2 field effect transistors through oxygen plasma treatment. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 195702 (2016).

Gao, T. et al. MoS2/MoOx heterojunction diode enabled via O2 plasma oxidation for photon-controlled rectification and nonvolatile memory applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 7, 4999–5007 (2025).

Shahrokhi, M., Raybaud, P. & Le Bahers, T. On the understanding of the optoelectronic properties of S-doped MoO3 and O-doped MoS2 bulk systems: a DFT perspective. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 9064–9074 (2020).

Kwon, J. I. et al. In-sensor multilevel image adjustment for high-clarity contour extraction using adjustable synaptic phototransistors. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt6527 (2025).

Hong, S. et al. Sensory adaptation and neuromorphic phototransistors based on CsPb(Br1–xIx)3 perovskite and MoS2 hybrid structure. ACS Nano 14, 9796–9806 (2020).

Huang, P. Y. et al. Neuro-inspired optical sensor array for high-accuracy static image recognition and dynamic trace extraction. Nat. Commun. 14, 6736 (2023).

Li, D. W. et al. Bidirectionally photoresponsive optoelectronic transistors with dual photogates for all-optical-configured neuromorphic vision. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2303198 (2023).

Wang, Y. R. et al. Dual-adaptive heterojunction synaptic transistors for efficient machine vision in harsh lighting conditions. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404160 (2024).

Wu, Q. Q. et al. Reticular photoelectrochemical transistor with biochemical metaplasticity. Adv. Mater. 37, 2504338 (2025).

Walkowski, S. & Szymas, J. Quality evaluation of virtual slides using methods based on comparing common image areas. Diagn. Pathol. 6, S14 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1200801), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62304226, 52188101, 62450124, 62125406), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024T170946, 2023M733574), the Excellent Youth Fund Project of Liaoning Province (2023JH3/10200003), the Outstanding Youth Fund Project of Liaoning Province (2025JH6/101100015), the Special Projects of the Central Government in Guidance of Local Science and Technology Development (2024010859-JH6/1006), the Special Research Assistantship Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (E455L502), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number GZB20230776, the Liaoning Provincial Key Laboratory of Public Opinion and Network Security Information System (d252453002), the Artificial Intelligence Technology Innovation Project of Liaoning Province (Grant No. 2023JH26/10300019), the Young Top-notch Talents of the National High-level Talent Special Support Program, the basic scientific research project of universities funded by the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education (LJ212510140016) and the Liaoning Province High-quality Industry-University Cooperation and Collaborative Education Project (241201160090747). The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Bing Yang and Dr. Honglei Chen from the Institute of Metal Research for their valuable support in HRTEM-EDS characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S., C.L., and H.C. supervised the project. R.H., S.F., D.J., and B.L. were equal major contributors. S.F. and R.H. performed device fabrication and measurement, assisted by B.L. and Y.S. D.J. performed stimulations of image sensors. R.H., S.F., B.L., C.L., and D.S. analyzed the data with discussions with G. Z. and Z.H. R.H., S.F., C.L., and D.S. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, R., Jia, D., Li, B. et al. Bioinspired phototransistor with tunable sensitivity for low-contrast target detection. Light Sci Appl 15, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02051-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-025-02051-1