Abstract

Piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers based on cantilever diaphragms have demonstrated promising electroacoustic efficiency and low-frequency sound pressure level (SPL). However, their total harmonic distortion (THD) significantly increases near the first resonant frequency, and high-frequency SPL (above 10 kHz) rapidly decreases due to the resonance frequency and bandwidth limitations, severely affecting sound quality. This work presents a piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker featuring a 2.7 µm-thick sputtered PZT film, comprising a cantilever diaphragm and four sets of Double-S actuators. The first resonance frequency of the cantilever diaphragm is 3.2 kHz, and the Double-S actuators introduce an additional resonance frequency at 21.3 kHz, addressing the issues of insufficient high-frequency SPL and poor THD performance. Testing on a 711-ear simulator reveals that, under 1–3 Vpp excitation, incorporating the Double-S actuators leads to an average SPL increase of 23 dB and an average THD reduction of 80% that remains below 0.6% across the 3.2–20 kHz range. Thus, both SPL and THD performance in the mid- to high-frequency range are improved. This work paves the way for the development of high-fidelity piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers, offering new opportunities to improve sound quality and extend the frequency range for in-ear applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing demand for high-performance miniature loudspeakers in consumer electronics, traditional dynamic loudspeakers encounter significant challenges in miniaturization1,2,3. Microelectromechanical system (MEMS) loudspeakers, which benefit from micromachining technologies, offer a promising solution due to their compact size, low power consumption, and cost-effectiveness4,5. Among various MEMS loudspeaker types6,7,8,9, piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers are particularly noteworthy for their high driving force and efficient electroacoustic conversion, making them especially well-suited for in-ear audio applications10,11,12,13.

Piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers based on cantilever diaphragms have gained significant attention due to the lower diaphragm stiffness, larger displacement, and higher low-frequency sound pressure level (SPL) if sealed with a polymer film14,15,16,17. Additionally, the cantilever diaphragm design effectively minimizes residual stresses in the diaphragm18. However, two key challenges remain. First, to meet low-frequency SPL requirements, the resonant frequency is typically designed below 6 kHz, which results in a sharp decline in high-frequency SPL, negatively impacting the clarity and detail of high-frequency sounds15,16,19,20. Second, piezoelectric hysteresis, residual stresses in the diaphragm, and nonlinear modes cause a significant increase in total harmonic distortion (THD) near the first resonant frequency16,20,21, making it challenging to achieve a THD below 3% across the entire frequency range22, which is a common requirement for commercial loudspeakers. These issues hinder the advancement of high-end piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers capable of delivering superior high-frequency fidelity.

To overcome these challenges, a common solution is to integrate both high-frequency and low-frequency units on the same chip to achieve SPL compensation and THD optimization23,24. For example, Y.-C. Chen et al. proposed a PZT piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker by dividing the chip area into mid-frequency and high-frequency units18. With an input voltage signal of 0.707 Vrms plus a 9 V bias, the loudspeaker achieved SPL ≥ 99.4 dB and THD ≤ 0.7% in the 8–13 kHz range. However, the THD was greater than 3% in the 6–8 kHz range, and SPL rapidly decreased beyond 13 kHz. H.-H. Cheng et al. introduced a PZT piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker featuring a high-frequency actuation unit resonating at 13.1 kHz and a low-frequency unit at 6.35 kHz22. Using a two-way driving method, the design achieved SPL ≥ 70 dB and THD ≤ 3% in the 5–13 kHz range. However, the two-way driving method was complex, and THD increased notably around 10 kHz.

In this paper, we propose a cantilever-diaphragm piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker based on Double-S piezoelectric actuators, utilizing a 2.7 µm-thick sputtered PZT film. Since 400 Hz is the typical frequency for human speech communication4, the frequency range discussed in this paper is from 400 Hz to 20 kHz. Recently we demonstrated that piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers with Double-S piezoelectric actuators achieved very low THD25. In this work, the proposed MEMS loudspeaker incorporates a cantilever diaphragm with a resonant frequency of 3.2 kHz in addition to four surrounding Double-S actuators. These actuators introduce additional resonant frequencies, particularly at 21.3 kHz, enabling SPL compensation and THD optimization in the target frequency range of 3.2–20 kHz. The excellent low-frequency characteristics of the cantilever diaphragm, combined with the introduction of Double-S actuators, make the proposed loudspeaker highly promising as an integrated MEMS loudspeaker optimized for a 400 Hz to 20 kHz frequency range. It has the potential to replace traditional, expensive dynamic and balanced armature loudspeakers in the future. Furthermore, the proposed design enables simultaneous driving of both the actuators and the cantilever diaphragm, significantly improving the efficiency of the piezoelectric diaphragm26.

Materials and methods

Device design and working principles

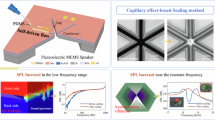

The schematic of the proposed piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker is shown in Fig. 1a, comprising four sets of Double-S actuators (each set with a length of 3.8 mm and width of 0.8 mm) and a cantilever diaphragm based on a cantilever beam structure (with a length of 3 mm). The effective area of the whole diaphragm is 28.3 mm², which consists of a stack of 320 nm Au/2.7 µm sputtered PZT/100 nm Pt/2.2 µm Si. The back of the cantilever diaphragm is surrounded by a 70 µm thick silicon frame to ensure stable diaphragm motion. The Double-S actuators and the silicon frame are connected via four joint beams. Notably, both the Double-S actuators and the cantilever diaphragm are free to deform vertically, as they both feature 20 µm-wide slits, which ensure that the slits can be fully etched. The top electrodes of the Double-S actuators are divided into two groups. When the applied voltages are in opposite phases, the two top electrode sections deform in opposite directions, resulting in Double S-shaped actuators that generates vertical displacement.

Compared to those cantilever diaphragm-based MEMS loudspeakers reported in the literature, e.g., in references14,15,16,19,20, the cantilever diaphragm of the loudspeaker proposed in this work is surrounded with a flexible edge connection provided by the vertically-deformable Double-S actuators, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Thus, this new MEMS speaker design can introduce smaller low-frequency resonant modes to enhance the low-frequency SPL. Meanwhile, the Double-S actuators can introduce multiple higher modes to improve mid-to-high frequency SPL, as demonstrated by the simulation results in the following subsection. More importantly, its flexible edge connection can greatly reduce the nonlinear response upon large diaphragm deformation needed for high SPL, resulting in low THD. Thereby, the proposed design can achieve high SPL with low THD in the entire audible frequency range.

The proposed loudspeaker involves several critical geometric parameters, including the layer thicknesses and size of the cantilever diaphragm, and the length and width of the Double-S actuators. The cantilever diaphragm mainly consists of the sputtered PZT layer and the elastic silicon layer offered by the device layer of silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafers. There exists an optimal thickness ratio between these two layers to maximize the diaphragm’s responsivity13. Meanwhile the overall thickness and area of the cantilever diaphragm must be chosen such that the in-ear size constraints and SPL requirement are balanced. Firstly, with available SOI wafers with the device layer thickness of 2.2 μm, the thickness of the PZT layer is set at 2.7 μm according to the optimal thickness ratio determination method reported in reference27. After that, the cantilever diaphragm’s length is set at 3 mm, yielding a resonant frequency at 3.2 kHz, which can greatly enhance the low-frequency SPL.

Each Double-S actuator is 3.8 mm in length to ensure large displacement and 0.8 mm in width to tailor the resonant modes. As the simulation results shown in Fig. 2, the Double-S actuators introduce a piston-like mode in the low-to-mid frequency range and an additional high-frequency resonant mode at 21.3 kHz, both of which contribute to enhanced broadband SPL.

The electrode design and working configuration of the proposed loudspeaker are illustrated in Fig. 1b. The cantilever diaphragm has an independent electrode (Electrode 1) and performs flexural motion in the d31 mode. The top electrodes of the Double-S actuators are divided into two parts: Electrode 2+ and Electrode 2-. Based on the combination of the excitation voltages applied to the Double-S actuators and the cantilever diaphragm, the proposed loudspeaker can operate in three different configurations. Config. A involves driving only the cantilever diaphragm, Config. B drives only the Double-S actuators, and Config. A + B drives both the diaphragm and the Double-S actuators simultaneously. It should be noted that in this work, when operating in Config. A + B, the driving voltages of Electrode 2+ and Electrode 1 are maintained in the same phase, and the complex phase relationships between the multi-electrodes are not discussed in this paper. By comparing the acoustic performance of Config. A + B and Config. A, the improvement in SPL and THD due to the introduction of Double-S actuators can be clearly observed.

Numerical simulation

For in-ear applications, the SPL is positively correlated with the air volume change generated by the diaphragm motion4,19. The air volume change is closely related to the diaphragm’s modes. Therefore, a Multiphysics FEM software (COMSOL 5.6a) is employed to simulate the diaphragm modes, normalized air volume change, and SPL in the IEC60318-4 standard 711 ear simulator15,28, as shown in Fig. 2. The proposed loudspeaker exhibits six characteristic modes, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Mode I is the piston mode introduced by the Double-S actuators, which can be realized in Config. B and Config. A + B, producing a large air volume change and SPL. Mode II is the torsional mode introduced also by the Double-S actuators, in which the diaphragm tilts about a fixed axis, generating relatively small air volume change and thus negligible SPL. Mode III is the drum mode introduced by the cantilever diaphragm, which can be realized in Config. A and Config. A + B, producing significant air volume change and SPL. Modes IV and V are the mid- to high-frequency modes introduced by the Double-S actuators, whose effects can be observed in Fig. 2b. Mode VI is the high-frequency mode introduced by the Double-S actuators, with a resonant frequency of 21.3 kHz, realizable in Config. B and Config. A + B, and producing significant air volume change and SPL.

Thanks to the additional modes introduced by the Double-S actuators, Config. A + B, compared to Config. A, exhibits additional resonance peaks at 0.9 kHz, 6.1 kHz, 11.8 kHz, and 21.3 kHz, as shown in Fig. 2b. Notably, the peaks at 0.9 kHz and 21.3 kHz have the most significant impact on the SPL in Fig. 2c, leading to a significant SPL enhancement, particularly in the frequency range of 3.2– 20 kHz.

Fabrication

The proposed piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker is fabricated on SOI wafers with a 2.2 μm-thick top silicon layer, a 1.1 μm-thick buried oxide (BOX) layer, and a 400 μm-thick silicon substrate. A ZrO₂ layer and a 100 nm Pt layer are sequentially deposited on a SOI wafer, where ZrO₂ serves as an insulation layer between the Pt and the silicon device layer. Subsequently, a 2.7 μm-thick PZT film is sputtered, exhibiting a measured d31 value of −55 pC/N.

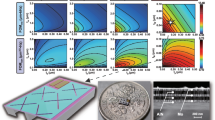

The process flow is illustrated in Fig. 3. The first photolithography step involves patterning the PZT layer to expose the platium (Pt) bottom electrode (Fig. 3a). Next, gold (Au) is sputtered and then patterned through a lift-off process (Fig. 3b. Subsequently, the PZT layer, Pt layer, and device Si layer are dry etched to form 20 μm-wide slits (Fig. 3c). A 3 μm-thick Parylene-C is then deposited to protect the front structures, preventing the Double-S actuators from being damaged during the cleaning process after release (Fig. 3d). A dual-back etching process is employed using deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) to form the 70 μm-thick silicon frame on the backside, which enhances the mechanical strength of the to-be-released microstructure and ensures the stable operation of the cantilever diaphragm (Fig. 3e, f. After that, the BOX layer in the SOI wafer is etched away using vapor-phase hydrofluoric acid. Finally, the front Parylene-C layer is etched away using O2 plasma, completing the release process (Fig. 3g). The SEM image of the cross-sectional view of the multilayer stack is shown in Fig. 3h.

a Wet etching the PZT layer. b Top electrode liftoff. c Dry etching the PZT layer, bottom electrode and top silicon. d Depositing Parylene-C. e The first back cavity etching. f The second back cavity etching and SiO2 etching. g Etching Parylene-C to release the device. h SEM image of the cross-sectional view of the multilayer stack

Several optical and SEM images of the fabricated MEMS loudspeaker are shown in Fig. 4a-d3, including the front view (Fig. 4a, d1), the backside view (Fig. 4c), and zoom-in images (Fig. 4b, d2, d3). Due to the design of the silicon frame, the cantilever diaphragm is able to be stably suspended with mechanical support from the Double-S actuators, as shown in Fig. 4a–c. Additionally, some residual traces of Parylene-C can still be clearly seen in Fig. 4d2. Furthermore, the slits are fully etched to ensure that the Double-S actuators and cantilever diaphragm can move under the constraints of the anchors and joint beams, as shown in Fig. 4b and d1. This careful fabrication process ensures optimal mechanical performance and precision in the final structure.

a Front image of the fabricated loudspeaker. b Zoom-in image of the Double-S actuator region. c Backside image of the fabricated loudspeaker. d1 SEM image of the front view. d2 d3 Zoom-in SEM images of d1. Surface profiles of e the cantilever diaphragm and f Double-S actuators without voltage excitation

To further understand the air leakage situation and stress control conditions of the proposed loudspeaker, the surface morphology of the released chip was characterized using a white light interferometer (Contour GT-IM, Bruker), as shown in Fig. 4e, f). First, the cantilever diaphragm exhibited an initially central upward warping, with the center being more than 40 µm higher than the surrounding substrate. This is likely due to the accumulation of residual stresses during the fabrication process. The considerable initial displacement of the cantilever diaphragm after release further exacerbated the air leakage issue. The Double-S actuators also showed localized warping after release, with the highest point about 25 µm above the substrate.

Results

Mechanical characterization

A laser vibrometer (OFV-534/5000, POLYTEC) is used to measure the dynamic vertical displacement of the microstructure of the piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker with an applied excitation voltage of 3 Vpp. Since the laser spot diameter is about 2 μm and the vertical displacement varies across the microstructure, four positions on one Double-S actuator and the diaphragm are selected for testing, as shown in Fig. 5a. Position 1 is at the joint beam position, Position 2 is located at the edge of the Double-S actuator, Position 3 is at the joint between the Double-S actuator and the substrate (anchor), and Position 4 is at the center of the cantilever diaphragm. These positions can effectively capture the movement characteristics of the entire microstructure.

Under Config. B, the frequency response of the peak-to-peak displacement at Positions 1, 2, and 3 from the 400 Hz to 20 kHz range is shown in Fig. 5b, which helps to understand the differences in mechanical vibration at different positions. First, Position 1 exhibits the largest peak-to-peak displacement across the entire frequency range, while Position 3 has the smallest peak-to-peak displacement, which is determined by the mechanical structure. Additionally, for Positions 1, 2, and 3, the peak-to-peak displacement increases with frequency in the 1 kHz to 20 kHz range, which is attributed to the mid-to-high frequency modes introduced by the Double-S actuators. This also confirms that the additional resonant modes introduced by the Double-S actuators indeed enhance the displacement levels at the mid- to high-frequencies. It is noteworthy that Position 2 does not exhibit significant displacement even under Mode I, as shown in Fig. 5b. This is believed to be caused by the residual stress-induced initial upward bending (see Fig. 4f) that constrains the dynamic displacement near Position 2.

Next, the frequency response of the peak-to-peak displacement at Position 4 for the three different configurations is shown in Fig. 5c, which helps to understand how much displacement improvement the introduction of the Double-S actuators can bring to the cantilever diaphragm. In Config. A (only driving the cantilever diaphragm), a resonance peak appears at 3 kHz, and the peak-to-peak displacement gradually decreases, which is consistent with the simulation results. In Config. B (only driving the Double-S actuators), the peak-to-peak displacement increases with frequency, aligning with the results in Fig. 5b. Although the test positions are different with that in Fig. 5b, the results still reflect the effect the Double-S actuators in improving the mid-to-high frequency displacement levels. Notably, in Config. A + B (simultaneously driving the cantilever diaphragm and Double-S actuators), the peak-to-peak displacement is the combination of the other two configurations: a resonance peak at 3 kHz and a displacement increases across the 5.6 kHz to 20 kHz range. This further demonstrates that the introduction of the Double-S actuators significantly improves the displacement levels of the cantilever diaphragm in the mid- to high-frequency range.

Acoustical characterization

The acoustical characterization of the piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker is performed in an ear simulator, as shown in Fig. 6a. The testing setup includes a computer, an acoustic analyzer (AAI-2718), a 711-ear simulator, an anechoic box, and the MEMS device under test (DUT). The acoustic analyzer is capable of sending two excitation voltages with a 180° phase difference and receiving signals from a standard microphone.

The SPL and THD of the proposed MEMS loudspeaker are tested in the frequency range of 400 Hz–20 kHz, with excitation voltages of 1 Vpp, 2 Vpp, and 3 Vpp. The SPL and THD are measured with all three distinct configurations, offering a comprehensive evaluation of the acoustic performance of the proposed MEMS loudspeaker and demonstrating the improvement in mid- to high-frequency SPL and THD brought about by the incorporation of Double-S actuators.

The tests are first conducted for Config. A, as shown in Fig. 6b, c. According to the SPL results in Fig. 6b, the first resonant frequency of the cantilever diaphragm is 3.2 kHz, which is consistent with the simulation results. In the frequency range of 3.2–20 kHz, the SPL decreases, affecting the high-frequency sound quality. Additionally, the cantilever diaphragm exhibits a smaller resonance peak around 0.9 kHz, which could be due to the coupling of the 0.9 kHz resonance peak from the Double-S actuators through the joint beam. Furthermore, between 400 Hz and 1 kHz, the SPL rapidly increases with frequency due to significant air leakage effects.

According to the THD results in Fig. 6c, the THD performance is poor across the 400 Hz–20 kHz range, with higher THD peaks at subharmonic and harmonic frequencies. This is primarily caused by piezoelectric hysteresis, film pre-stress, and nonlinear effects at resonance, which are common issues in cantilever diaphragms18,21.

Next, Config. B is tested. Based on the SPL results shown in Fig. 6d, a resonance peak appears at 900 Hz, which is consistent with the simulation results. As the frequency increases, the SPL shows a logarithmic frequency increase, which is due both to the mid- to high-frequency modes introduced by the Double-S actuators and to the positive correlation between SPL and frequency in the ear-simulator testing environment, which is also predicted by the simulation results. By comparing the SPL responses of Config. A and Config. B, it is observed that the cantilever diaphragm’s SPL in Config. A is higher around 3.2 kHz, while Config. B shows higher SPL in the 4–20 kHz range.

It is worth noting that the commonly observed SPL peak around 13.8 kHz, which is typically attributed to the acoustic resonance of the ear simulator15,19,27,28, is not present in either the simulation or experimental results of this study. This is believed to be attributed to the relatively wide (20 μm) slits in the proposed loudspeaker, which lead to significant air leakage. As reported in reference29, the SPL peak caused by the ear simulator becomes progressively less pronounced as the slit width increases, and nearly disappears when the width reaches 20 μm.

As shown in the THD results of Config. B in Fig. 6e, for excitation voltages of 1 Vpp or 2 Vpp, the THD is less than 0.5% in the 1–20 kHz range. For 3 Vpp excitation, the THD remains below 0.75% in the same frequency range. This improvement is mainly due to the multiple resonant modes introduced by the Double-S actuators in the mid- to high-frequency ranges, which significantly enhances the SPL. Meanwhile, the THD is readily given by19,22:

where \({\rm{p}}({\rm{f}})\) is the sound pressure at the fundamental frequency \({\rm{f}}\), and \({\rm{p}}({\rm{if}})(i\ne 1)\) is the sound pressure at the ith harmonic frequency. Thus, higher sound pressure at the fundamental frequency will lead to smaller THD. The flexible edge connection of the cantilever diaphragm effectively mitigates nonlinear responses under large deformations. In addition, the mass effect of the silicon frame further contributes to the shift of harmonic peaks. Additionally, there is a rapid drop-off in the THD near 16 kHz for excitation voltages between 1 Vpp and 3 Vpp, although the THD remains below 0.75%. This is believed to be caused by some secondary effects that will be further studied with more experimental investigation.

Finally, Config. A + B is tested. The results are compared with those of Config. A to analyze the improvement in SPL and THD due to the introduction of the Double-S actuators. According to the SPL results in Fig. 6f, two prominent resonance peaks are observed at 0.9 kHz and 3.2 kHz, along with a smaller peak near 12 kHz, which is consistent with the mode simulation. Furthermore, the SPL of Config. A + B is higher across the entire frequency range compared to Config. A, particularly in the 3.2–20 kHz range, where the SPL increases rapidly with frequency. The average SPL increases by 23 dB, with a 42.3 dB SPL improvement at 16 kHz under a 1 Vpp excitation voltage. In fact, the SPL across the entire frequency range in Config. A + B is approximately the sum of the SPL levels of Config. A and Config. B, which is consistent with the mechanical testing results shown in Fig. 5c.

As shown in Fig. 6g, the THD in Config. A + B is lower across the entire frequency range compared to Config. A, especially in the 3.2–20 kHz range, where the average THD is reduced to less than 0.6%, which is 20% of the original value. This improvement is mainly due to the rapid increase in SPL in the mid- and high-frequency ranges. The THD near 3.2 kHz is also significantly reduced compared to Config. A, but remains above 3%, primarily because the SPL at 3.2 kHz is predominantly generated by the cantilever diaphragm, so its THD is similar to those of Config. A. In fact, some interesting phenomena are observed in the THD frequency responses under different configurations. For example, a prominent THD peak near 500 Hz is evident in the proposed loudspeaker when operating in either Config. A or Config. B. Interestingly, when the loudspeaker operates in Config. A + B, a significant reduction in THD at the same frequency is observed. This phenomenon may be attributed to the complex coupling between the cantilever, the silicon frame and the Double-S actuators, especially when the Double-S actuators and the cantilever diaphragm are actuated simultaneously. This phenomenon needs further investigation.

Furthermore, when considering both SPL and THD simultaneously, the optimal performance of the loudspeaker under three different configurations can also be obtained. Under 1 Vpp excitation, Config. B achieves SPL ≥ 87 dB and THD ≤ 0.6% in the 4–20 kHz range, while Config. A + B performs that in the 3.55–20 kHz range. Under 2 Vpp excitation, Config. B achieves SPL ≥ 93 dB and THD ≤ 0.5% in the 4.25–20 kHz range, while Config. A + B performs in the 3.75–20 kHz range. Under 3 Vpp excitation, Config. B achieves SPL ≥ 96 dB and THD ≤ 0.9% in the 4.25–20 kHz range, while Config. A + B performs in the 3.75–20 kHz range. However, in all of the above cases, Config. A fails to meet the requirements.

Discussion

The acoustic performance of the piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker developed in this work is compared with those of existing piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers, as shown in Table 1. Taking SPL ≥ 80 dB, SPL ≥ 100 dB, THD ≤ 3% and THD ≤ 1% as the criteria separately22, this newly developed MEMS loudspeaker achieves both high SPL and low THD in the mid-to-high-frequency range, with a bandwidth extending above 12 kHz.

Furthermore, when considering both SPL and THD simultaneously, the proposed loudspeaker still exhibits a very wide bandwidth in the mid- to high-frequency range, as shown in Fig. 7. Whether considering SPL ≥ 80 dB and THD ≤ 3%, or higher performance with SPL ≥ 100 dB and THD ≤ 1%, the proposed loudspeaker outperforms state-of-the-art loudspeakers in terms of bandwidth. Compared to cantilever diaphragm designs, the proposed Double-S actuators-based loudspeaker demonstrates significant potential in optimizing SPL and THD in the mid-to-high frequency range, while also offering an extended bandwidth.

This not only means that the proposed loudspeaker can improve the sound quality of traditional cantilever diaphragms in the mid-to-high frequency range, but it also positions the loudspeaker as a potential alternative to expensive balanced armature for commercial applications, thereby driving the development of high-fidelity piezoelectric MEMS headphones.

In fact, the proposed piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker still has some limitations. On the one hand, due to significant air leakage issues, low-frequency SPL is limited, but this can be addressed by applying a layer of organic film. On the other hand, the Double-S actuators have relatively low stiffness, making them prone to damage under high voltage excitation, which can be resolved through further structural optimization.

Conclusion

In this work, we present a promising piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker for in-ear applications, utilizing Double-S actuators and a 2.7 μm thick sputtered PZT material. By introducing additional resonant frequencies through the Double-S actuators, significant improvements are made to the SPL and THD performance of the cantilever diaphragm in the mid- to high-frequency range (3.2–20 kHz). Specifically, the SPL is enhanced by an average of 23 dB, with a maximum increase of 42.3 dB at 16 kHz under 1 Vpp excitation. Meanwhile, the average THD is reduced to below 0.6%, representing just 20% of its original value. These improvements effectively address the previous limitations in sound quality in the mid- to high-frequency range.

Besides, a simple yet effective strategy for improving the full-frequency SPL and THD performance of piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers is introduced: by incorporating Double-S actuators or similar structures around a well-performing MEMS loudspeaker, it is anticipated that a fully optimized piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker across the entire frequency range can be realized. This approach offers a feasible direction for the development of high-end MEMS loudspeakers.

Furthermore, leveraging the cantilever diaphragm’s excellent low-frequency response, the proposed integrated loudspeaker demonstrates significant potential as an alternative to the complex and costly dynamic coil plus balanced armature systems, despite the current issue of air leakage. The integrated MEMS solution significantly reduces both the cost and assembly complexity, offering a non-traditional approach for the innovation and development of high-end high-fidelity in-ear audio devices.

References

Hwang, S-M, Lee, H-J, Hong, K-S, Kang, B-S & Hwang, G-Y New development of combined permanent-magnet type microspeakers used for cellular phones. IEEE Trans Magn 41, 2000–2003 (2005).

Huang, J H, Her, H-C, Shiah, Y C & Shin, S-J Electroacoustic simulation and experiment on a miniature loudspeaker for cellular phones. J Appl Phys 103, 033502 (2008).

Horowitz, S, Nishida, T, Cattafesta, L & Sheplak, M Development of a micromachined piezoelectric microphone for aeroacoustics applications. J Acoust Soc Am 122, 3428–343 (2007).

Wang, H et al. Review of Recent Development of MEMS Speakers. Micromachines 12, 1257 (2021).

Garud, M & Pratap, R MEMS audio loudspeakers. J Micromech Microeng 34, 013001 (2023).

Arevalo, A, Conchouso, D, Castro, D, Kosel, J & Foulds, IG. Piezoelectric transducer array microspeaker. In the 11th Annual International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS), p. 180–183 (IEEE, 2016).

Casset, F et al. A 256 MEMS membrane digital loudspeaker array based on PZT actuators. Procedia Eng 120, 49–52 (2015).

Wang, Y, Lv, T, Zhang, J & Yu, H Capillary effect-based selective sealing strategy for increasing piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker performance. Microsyst Nanoeng 10, 108 (2024).

Roberts, R. C. et al. Electrostatically driven touch-mode poly-SiC microspeaker. In IEEE Sensors Conference, p. 284-287 (IEEE, 2007).

Lu, L et al. A piezoelectric MEMS microphone with proof mass and its array. Sens Actuat A 377, 115735 (2024).

Zheng, Q et al. Thin ceramic PZT dual- and multi-frequency pMUT arrays for photoacoustic imaging. Microsyst Nanoeng 8, 1 (2022).

Wang, H, Feng, PXL & Xie, H. A dual-electrode MEMS loudspeaker based on ceramic PZT with improved sound pressure level by phase tuning. In the 34th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), p. 701-704 (IEEE, 2021).

Wang, H, Chen, Z & Xie, H A high-SPL piezoelectric MEMS loud loudspeaker based on thin ceramic PZT. Sens Actuat A 309, 112018 (2020).

Xu, L et al. A piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker with stretchable film sealing. In the 36th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), p. 673-676 (IEEE, 2023).

Ma, Y et al. A PZT MEMS loudspeaker with a quasi-closed diaphragm. Sens Actuat A 358, 114454 (2023).

Deng, N et al. Optimization of dual-electrode ratio and driving phase of piezoelectric MEMS Speakers for improving sound pressure level. Sens Actuat A 382, 116109 (2024).

Wang, Q et al. Obtaining high SPL piezoelectric MEMS speaker via a rigid-flexible vibration coupling mechanism. J Microelectromech Syst 30, 725–732 (2021).

Chen, Y-C et al. On the design of a two-way piezoelectric MEMS microspeaker based on a multi-shape cantilever array for high-frequency applications. J Micromech Microeng 33, 074001 (2023).

Liu, C et al. Ultrahigh-sensitivity piezoelectric AlN MEMS speakers enabled by analytical expressions. J Microelectromech Syst 31, 664–672 (2022).

Stoppel, F et al. New integrated full-range MEMS loudspeaker for in-ear applications. In the 31st IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), p. 1068-1071 (IEEE, 2018).

Gazzola, C, Corigliano, A & Zega, V Total harmonic distortion estimation in piezoelectric micro-electro-mechanical-system loudspeakers via a FEM-assisted reduced-order-model. Mech Syst Sig Process 222, 111762 (2025).

Cheng, H-H & Fang, W THD improvement of piezoelectric MEMS loudspeakers by dual cantilever units with well-designed resonant frequencies. Sens Actuat A 377, 115717 (2024).

Stoppel, F et al. Novel membrane-less two-way MEMS loudspeaker based on piezoelectric dual-concentric actuators. In the 19th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (Transducers), p. 2047-2050 (IEEE, 2017).

Cheng, H-H et al. Monolithic integration of PZT actuation units of various activated resonances for full-range MEMS loudspeaker array. In the 36th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), p. 685-688 (IEEE, 2023).

Zheng, Q et al. An ultra-low total harmonic distortion piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker with double-S unimorph actuators. In the 38th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), p. 799-801 (IEEE, 2025).

Cheng, H-H et al. On the design of piezoelectric MEMS microspeaker for the sound pressure level enhancement. Sens Actuat A 306, 111960 (2020).

Zheng, Q et al. An ultra-high low-frequency SPL piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker based on sputtered PZT. Sens Actuat A 389, 116551 (2025).

Gazzola, C, Zega, V, Cerini, F, Adorno, S & Corigliano, A On the design and modeling of a full-range piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker for in-ear applications. J Microelectromech Syst 32, 626–637 (2023).

Gazzola, C, Zega, V, Corigliano, A, Lotton, P & Melon, M A reduced-order-model-based equivalent circuit for piezoelectric micro-electro-mechanical-system loudspeakers modeling. J Acoust Soc Am 155, 1503–1514 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant 62350710218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QZ designed, fabricated, and characterized the devices and drafted the manuscript. KC, XM, ND, HC, and YC cooperated in the experiments, YL supervised the experiment, HX supervised the experiment and checked it for final submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Q., Cao, K., Ma, X. et al. SPL and THD improvement of a cantilever-diaphragm piezoelectric MEMS loudspeaker with Double-S actuators. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01031-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01031-0