Abstract

The paper introduces a microreactor with high thermal insulation properties, which has been developed for integration with standard planar-type solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) in portable power generation applications. While planar SOFCs offer high efficiency and energy density, their use has been largely limited to stationary applications due to challenges in thermal management and slow start-up times. Our microreactor overcomes these barriers by providing an effective thermal insulation system, allowing SOFCs to operate efficiently in a compact, portable format. We designed a cantilevered structure using yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) to minimize thermal conduction and combined it with a multilayer insulation (MLI) system to suppress thermal radiation loss. This flexible cantilevered structure prevents cracking under thermal stress and maintains high temperatures up to 700 °C, ensuring reliable operation. Additionally, the MLI system features an inherent safety mechanism: when the insulation structure is damaged by a drill, the loss of thermal insulation causes a rapid temperature drop, bringing the system below the hydrogen explosion threshold temperature within 5 minutes, thus preventing potential hazards. Our prototype successfully demonstrated handheld power generation using a button-type metal-supported SOFC, achieving a rapid start-up time of just 5 minutes and driving a motor. This breakthrough offers a new platform for miniaturized SOFC technology, bridging the gap between stationary and portable energy solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the societal deployment of edge devices such as artificial intelligence (AI), drones, and robotics has accelerated rapidly, increasing the demand for high-energy-density and high-efficiency power sources to operate them1. For example, in aerial devices like drones, enhancing energy density can significantly extend flight time and broaden application potential. Currently, lithium-ion batteries are widely used; however, their energy density is fundamentally limited by the theoretical capacity of active materials, making further improvements challenging2.

Handheld high-energy power sources can expand the range of potential applications, particularly portable usage. It seems inevitable that in the future, artificial intelligence, drones, and robots will become more prevalent in society. To support such remarkable technological development, environmentally friendly, compact, and high-density energy is required. The researchers have focused on solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), which are characterized by high energy efficiency, energy density, power density, and few restrictions on fuel types3. Most of the current research is focused on the practical applications of SOFCs as stationary power sources. Theoretically, the potential for an unprecedented miniaturization of SOFC could lead to a portable power source (1–20 W) with an energy density four times greater than that of existing lithium batteries, thereby meeting the energy needs of the next generation2,4. Furthermore, the ability of the SOFC power device to be refueled instantaneously could prove to be a substantial advantage. Nevertheless, no SOFC has yet been miniaturized to the extent that it can be held in the palm of the hand during operational conditions at high temperatures.

In previous studies, micro-SOFCs fabricated by MEMS (Micro Electro Mechanical Systems) process show potential for palm-sized SOFC. The micro-SOFC have thin cell membranes (<1 μm) with large areas have been demonstrated to high-performance attributable to reduced ion resistance at low temperature. However, micro SOFC has three main challenges for practical usage. Firstly, the thin cell membranes cause mechanical weakness and gas intermixing5. Secondly, the thermal expansion mismatch between substrate and micro-SOFC prevents the high operation temperature; the high operation temperature enables versatile fuel without coking. Finally, scaling up the electrochemically active area for high power output is challenging using MEMS process (high vacuum)6.

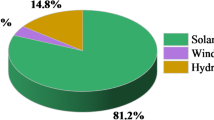

To address the limitations associated with micro-SOFCs, we propose the use of button-type SOFCs, which have been previously reported to offer high electrochemical performance and are generally simpler to fabricate than conventional planar cells. In modern systems, large planar cells are linked together in series using connections that serve as both electrical contacts and gas channels between each cell. These setups are called “stacks” and are organized to produce the needed voltage and power for various uses, such as portable power, transportation, localized power generation, or large-scale power generation (higher than 100 watts Fig. 1a). Small planar cells with high performance and quick start-up, especially metal-supported SOFC (MS-SOFC), have already been developed7. Consequently, the integration of these developed small planar cells into a microreactor can best approach to the small power portable industry (Fig. 1a). This distinction forms the core focus of our research. The step-by-step integration of the already developed planar (or button-type) SOFC technology within the microreactor is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1b.

a Schematic illustration of a microreactor designed to accommodate commercially available planar-type SOFCs typically used in stationary applications, highlighting the transition from large-scale to miniature power systems. b Exploded view and schematic cross-section of the microreactor showing its assembly method and internal structure

The key technologies for handheld SOFC are thermal insulation and thermal stress-relief structure. The high thermal insulation is required for thermally self-sustaining (Zhao et al.8) and keeping the outside temperature in a possible handheld range2. Subsequently, the thermal stress-relief structure is also important for steep temperature gradients (inside: 600 °C, outside: 100 °C), which damages the devices. In addition, the thermal stress-relief structure reduces start-up time without cracking.

This study demonstrates a potential approach for the development of the lightest handheld SOFC module for portable applications. This research introduces the concept of Micro-TAS to the field of independent SOFC system research for miniature/portable systems. Largely, Micro-TAS concept which is widely used in biomedical research9,10,11. The Micro-TAS system comprises electrochemical reaction chambers, inlets and outlets for reactant gases (fuel and oxygen), and a silver electrode serving as a current collector on a single ceramic substrate. Here we report an efficient and low-thermal-stress ceramic reactor design that can readily withstand rapid heating without compromising its structural integrity. The major challenge in the miniaturization of SOFC is the development of an efficient thermal management system. This issue can be effectively addressed through the application of multilayer insulation (MLI), which offers a promising approach for achieving thermal insulation in portable SOFC systems. Furthermore, the safety aspects of these devices are also addressed in relation to mechanical damage to the insulation structure, which can lead to a rapid temperature drop and prevent potential damage.

Results

Simulation of thermal stress distribution and heat flux analysis

To miniaturize SOFCs that operate at high temperatures, it is imperative to achieve high thermal insulation in order to maintain the desired operating temperature. However, achieving high thermal insulation introduces the challenge of thermal stress, necessitating the design of structures that can withstand these stresses. Therefore, three types of structures were designed: a cantilevered structure, a double-cantilevered structure, and a simple planar structure.

The thermal performance of cantilevered, double cantilevered, and planar structures under localized high-temperature conditions was evaluated, as shown in Fig. 2a–i. The temperature distributions in the thermal performance of cantilevered, double-cantilevered, and planar structures under localized high-temperature conditions were evaluated, as shown in Fig. 2a–i. The temperature distributions in Fig. 2a–c reveal that the cantilevered configuration (Fig. 2a) exhibits the most confined temperature gradient, particularly within the SOFC region. Even under an 800 °C heat source, the temperature variation remains minimal, facilitating safer and more stable reactor operation. In contrast, the double cantilevered (Fig. 2b) displays a broader temperature spread, and the fully planar structure (Fig. 2c) shows the most severe thermal gradient, indicating inefficient thermal confinement.

(a–c) Temperature distribution, (d–f) thermal stress distribution, and (g–i) thermal flux distribution. Boundary conditions were set at 800 °C for the center temperature and 20 °C for the circumference, and simulations were performed with the circumference fixed as a constraint condition. The average element size of the mesh was 0.5 mm, using absolute size

The corresponding thermal stress distributions are presented in Fig. 2d–f for the cantilevered, double cantilevered, and planar structures, respectively. The maximum thermal stress in the cantilever design is calculated to be 253 MPa, localized near the root of the outer perimeter of the beam. This is substantially lower than in the other two configurations. In the double-cantilevered structure (Fig. 2e), thermal stress peaks at 885 MPa, primarily concentrated at the corners and inner mounting regions due to constrained thermal expansion in the beam direction. The fully planar structure (Fig. 2f) exhibits the highest thermal stress, reaching 1131 MPa, uniformly distributed in the high-temperature core. Given the tensile strength of Macor® (~345 MPa), both the double cantilevered and planar structures would undergo material failure under an 800 °C thermal load, whereas the cantilevered structure remains mechanically viable.

The heat flux distributions, depicted in Fig. 2g–i, further underscore the superior thermal performance of the cantilever design. The maximum heat flux in the cantilevered structure (Fig. 2g) is 0.18 W/mm², with a beam cross-sectional area of 4.4 mm², resulting in a total heat transfer of 0.792 W. In the double-cantilevered structure (Fig. 2h), the heat flux is distributed over two beams, each experiencing a peak of 0.2 W/mm². The combined heat transfer across the 8.8 mm² cross-sectional area amounts to 1.76 W. The planar configuration (Fig. 2i) demonstrates the highest heat dissipation, with a maximum heat flux of 0.174 W/mm² and a total heat transfer of 8.15 W from the cell mounting area to the surroundings. Although the maximum heat flux is a bit lower than the cantilevered, that is because of the larger surface area of planar ceramics.

Therefore, the cantilevered support structure demonstrates a clear advantage in thermal stress mitigation and heat flux minimization. These factors are critical for the efficient and reliable operation of SOFC systems. The significantly lower thermal stress and reduced heat leakage in the cantilevered design position are highly favorable configurations for thermomechanical stability and energy efficiency in high-temperature electrochemical devices.

Evaluation of maximum operating temperature in cantilevered structure

To investigate how structural differences affect the maximum operating temperature, localized heating was applied to the samples. In Fig. 3a, a photograph of the fully planar structure subjected to localized heating is shown, where cracks can be observed after heating. The localized heating was achieved using a sputter-deposited microheater, with the heated area indicated by the red dashed line. Figure 3b presents an infrared image of the planar structure during heating, illustrating that the center was locally heated by the microheater. The maximum temperature reached was 353 °C, and the structure failed immediately after this point, as shown in Fig. 3c. This failure is attributed to the fixed nature of the planar structure, where a large thermal stress is generated due to the steep temperature gradient between the heated and unheated areas, ultimately leading to material failure. In contrast, the cantilevered structure exhibited a different behavior. Figure 3d shows a photograph of the cantilevered structure during heating, with the corresponding infrared image shown in Fig. 3e. The maximum temperature reached was 1011 °C. Although a thermal gradient and thermal expansion were observed at the cantilevered structure, it did not crack. This can be attributed to the flexibility of the cantilevered structure, which allows for some degree of movement, thereby alleviating thermal stress and preventing material failure. Finally, Fig. 3f compares the maximum operating temperatures of the structures, demonstrating that the cantilevered structure significantly improves heat resistance.

a Photograph of the planar structure after the heat resistance test, with black arrows indicating the locations of cracks, b Infrared image of the planar structure just before cracking, c Infrared image of the planar structure immediately after cracking, d Photograph of the cantilevered structure during the heat resistance test, e Infrared image of the cantilevered structure, and f Comparative chart of the maximum operating temperature between the planar structure and the cantilevered structure

Evaluation of electromotive force generation in a planar cell with cantilevered structure and microchannel

Drawing on previous experimental results, it has been demonstrated that the cantilevered structure exhibits superior heat resistance. Following this, we created a microchannel and installed a button cell to confirm the generation of EMF using hydrogen. Figure 4a shows a photograph of the microchannel fabricated by cutting Macor ceramics, and Fig. 4b is an enlarged image of the channel. The arrows indicate the direction of hydrogen flow from the inlet to the outlet. By placing a cell and glass ceramics on top of this channel, the channel was sealed, isolating the hydrogen and oxygen environments, as illustrated in Fig. 4c. Figure 4d shows a side view of the channel, with the width of the outlet and inlet being 0.5 mm.

a Photograph of the microreactor exterior. b Image of the flow channels designed for hydrogen passage, with arrows indicating the fuel flow direction between the inlet and outlet. c Photograph of the assembled reactor. d Cross-sectional image of the micro flow channels. e Infrared image of the SOFC when heated. f Time-series measurement of the electromotive force (EMF) showing the variation when hydrogen is introduced and stopped, with arrows indicating the switching points between “on” (hydrogen flow started) and “off”

By incorporating flow channels within the cantilevered structure, high heat exchange efficiency is expected due to the microchannel properties. As demonstrated in the previous section, the heat transfer coefficient increases dramatically as the size of the microchannel decreases. This increase is necessary to maintain the same Nusselt number, leading to a much more efficient removal of heat compared to larger-scale channels12. We observed this microchannel effect in the cantilevered structure’s microchannels, where the reduced channel size contributes to high heat exchange efficiency, enabling effective thermal management within the system. To predict the exchange efficiency, simulations were conducted. The simulation model is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, with the conditions listed in Supplementary Table T1. The results of the thermal distribution from the simulations, comparing structures such as the one cantilevered structure and end-supported structure, are shown in Fig. S2. The heat exchange efficiency was calculated as temperature efficiency, based on the temperature difference between the hydrogen inlet and the exhaust outlet, and the results are summarized in supplementary Fig. S3. For the cantilevered structure with inlet-to-outlet distances of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mm, a high-temperature efficiency of over 90% was achieved in each case. These values indicate a higher efficiency compared to the end-supported structure and the independent structure. Finally, EMF was measured by introducing hydrogen to the cantilevered structure (Supplementary Fig. S4). The cell installation area was heated using a burner, and hydrogen was introduced via a syringe pump. A metal mesh was placed over the cathode, which was connected to a silver wire above. Figure 4e illustrates the surface temperature profile of the cell obtained via infrared camera during the heating process. The temperature of the cathode’s outer region reached 500–600 °C. Although the center of the cathode appears cooler due to the metal mesh, it is likely at the same or higher temperature as the surrounding cathode area. Finally, Fig. 4f presents the EMF measurement results when hydrogen was introduced. When hydrogen was supplied, the EMF rose to ~1.0 V, and when the hydrogen supply was stopped, the EMF gradually decreased. These results indicate that the combination of the cantilevered structure and microchannel can successfully operate SOFCs.

Measurement of thermal stress in YSZ cantilevered structure by X-ray

Glass ceramics with excellent machinability offer ease of processing and low thermal conductivity, making them suitable for creating cantilevered structures that achieve high thermal insulation. However, these materials have drawbacks, including low mechanical strength and a thermal expansion coefficient that differs from that of the SOFC cells. To address these issues, we fabricated a cantilevered structure using 3YSZ ceramic because of its high toughness. Since SOFC cell electrolytes commonly use zirconia-based materials like 8YSZ, matching the thermal expansion coefficient of the cell is crucial. Therefore, constructing a cantilevered structure with 3YSZ, which has a thermal expansion coefficient close to that of the cell, offers significant advantages. Due to the difficulty of machining YSZ, we utilized a fiber laser to create the cantilevered structure. We then investigated whether the cantilevered structure in YSZ could alleviate thermal stress using X-ray analysis.

Figure 5a shows samples with stainless-steel heaters attached to both the planar structure and the cantilevered structure. Infrared microscopy images reveal that a thermal gradient forms when the heater is ignited in both structures (Fig. 5b, c). In the planar structure (Fig. 5b), the highest temperature is observed at the center, with a gradual decrease in temperature as the distance from the center increases. Conversely, in the cantilevered structure, while heat gradually changes across the cantilever, the central area and the cut-out sections of YSZ exhibit minimal heat transfer, resulting in lower temperatures in the outer regions. The measured heat stress at different points of the cantilevered ceramic is illustrated in Fig. 5d, and similar measurement points were considered for the planar structure. Figure 5e illustrates the relationship between thermal stress and measured maximum temperature at different points of the ceramics. In the cantilever structure, the thermal stress at various locations showed no significant changes, ranging from 39 MPa to 58 MPa at room temperature, and from 17 MPa to 66 MPa at 452 °C. In contrast, the planar structure exhibited a different pattern. While the thermal stress at the top, top-right, and bottom of the structure remained relatively stable, ranging from 33 MPa to 46 MPa at room temperature and from 35 MPa to 63 MPa at 382 °C, the thermal stress at the center and bottom-right increased significantly, from 30 MPa to 60 MPa at room temperature to 162 MPa to 225 MPa at 382 °C. Additionally, some of the samples with planar structure had cracks above 400 °C. These results correlate with previous findings obtained from glass ceramics, reinforcing the effectiveness of the cantilevered structure in managing thermal stress.

Photograph of a Planar structure and cantilevered structure heated at 200 °C, b thermal mapping in planar structure, c thermal mapping of cantilevered structure, d different measurement points in the cantilevered structure, and e plot of thermal stress against temperature of planar structure and cantilevered structure. The triangle markers indicate the measurement points at cantilevered structure, whereas circular markers represent measurement points from the planar structure

Designing and simulation MLI systems

Thermal management of an SOFC system is of paramount importance for its efficient operation and long lifetime, and the MLI approach was used here. MLI is a high-temperature insulation system that uses a series of highly reflective layers to deflect radiant heat13,14. Each layer functions primarily by reflecting thermal radiation and is therefore referred to as a ‘mirror’ throughout this study. The MLI approach is rarely studied. For example, Spinnler et al.15 conducted a theoretical and experimental analysis of a high-temperature insulation system using a variety of class mirror materials (steel, ceramic, and gold with low, intermediate, and high reflectivity) with and without different fibrous/microporous space materials (typically ceramics). Nevertheless, the employment of light organic-based mirror materials is scarce. Consequently, this investigation explores the development of lightweight and efficient self-standing thermal systems, which represent a crucial consideration for portable SOFC devices. The simulated data indicated that the highest temperature, reaching 800 °C, was recorded in the vicinity of the heater source, while the maximum temperature observed in the outer area, adjacent to the box, ranged between 80 °C and 25 °C (Fig. 6a). Additionally, it was observed that heat dissipation occurs in a vertical direction through the mirrors. It was observed that the sets of multilayer mirrors mounted in the box promote thermal insulation through radiation by limiting external heat dissipation. It is important to acknowledge that the thermal insulation system in the existing system is contingent upon a multitude of variables, including the thickness of the ceramic material, the emissivity of the ceramic reactor, the emissivity of the mirrors, the gap between each mirror and the fluid media within the box. Figure 6b depicts the resulting temperature profile against the applied power input to the attached heater in the ceramic reactor. The temperature was observed to reach 546 °C in the air atmosphere when 10 W was applied, while in the krypton medium, the temperature was recorded at 720 °C. It was observed that the multilayer mirrors mounted in the box promote thermal insulation through radiation, thereby limiting external heat dissipation. However, the insulation layer of mirrors situated in proximity to the center and the heater area undergoes heating, which gives rise to mild burning because of conduction at temperatures exceeding 600 °C. It is thus recommended that, in the future, a robust system be prepared by considering the use of thinner ceramics with low emissivity and lower thermal conductivity, alternative materials for mirrors as MLI systems, and inert low-thermal-conducting fluidic conditions within the SOFC box.

Electrochemical performance

Metal-supported SOFCs have great potential to fill the gap that exists in the conventional anode-supported SOFC. Metal-supported SOFCs can provide excellent electrochemical performance, fast start-up time, longer time stability, excellent mechanical strength, high robustness against vibration and redox cycles, enable reduction of material cost, and easy joining16,17,18. The integrated metal-supported SOFC into the ceramic reactor is illustrated in Fig. 7a. The electrochemical performance of the metal-supported cell was recorded at temperatures ranging from 480 to 630 °C. Figure 7b shows the electrical output of the integrated metal-supported SOFC in the microchannel reactor. The maximum power density (MPD) of the cell was measured to be 121, 93, 88, 62.7 and 24 mWcm−2 at 630, 605, 590, 525 and 480 °C, respectively. The OCVs were found to be 1.040, 1.042, 1.030, 1.111 and 1.121 V at 630, 605, 590, 525 and 480 °C, respectively. The OCV represents a quantitative measure of the tightness of the gas or fuel and therefore of the integrity of the seal, which is a critical issue for SOFC systems. A higher OCV ( > 1.0 V) value indicates that the metal-supported SOFCs were robustly fixed in the ceramic microreactors. The EIS spectra of the cells and their corresponding circuit fitting for testing at different temperatures are illustrated in Fig. 7c. At 630 °C, the total resistance and polarization resistance of the cells were observed to be 2.6 Ω cm² and 0.9 Ωcm², respectively. It is noteworthy to note from the DRT spectra (Fig. 7d) that high-temperature operations exceeding 525 °C exhibited a pronounced prevalence of high-frequency peaks. This phenomenon is linked to the transfer of O2− across the electrode/electrolyte interface, which appears to represent a predominant rate-limiting step within this temperature range19. However, the intermediate frequency peaks were also noted to be dominant particularly at 630 °C, which is related to the dissociation of O2 into 2Oads19,20.

As per the supplier information, metal-supported SOFCs demonstrated MPD of 2.5, 2, 1.34, and 0.7 W cm⁻² at operating temperatures of 750, 700, 650, and 600 °C, respectively, as illustrated in supplementary Fig. S6. Additionally, the OCVs were observed to be 1.130, 1.139, 1.146, and 1.154 V at 750, 700, 650, and 600 °C, respectively, which is an exceptionally high value21. It should be noted that the cathode of the metal-supported SOFCs was in-situ sintered during electrochemical testing conditions. To prevent metal oxidation, sintering must occur at a temperature below 900 °C18. The majority of studies have focused on in-situ sintering of the cathode during performance tests. However, due to the inherent limitations of the SOFC box in this system, it is not feasible to exceed a temperature of 650 °C. It is crucial to emphasize that the cathode layer of TAIYO YUDEN’s cell was not sintered. As a result, the sintering process was conducted at 750 °C for the duration of 1 hr. This necessitated the exposure of the metal-supported anode side of the cell to the reduced gas, which flowed continuously at a rate of ~5 ml/min (comprising 4% H₂ and 96% N₂) to prevent the oxidation of the metal support22. Meanwhile, the cathode side was maintained in airflow at a rate of 200 ml/min.

The electrochemical performance obtained in this study was relatively low compared to the values reported by TAIYO YUDEN. This difference is mainly due to incomplete or suboptimal sintering of the cathode. In our setup, the cathode was sintered separately at 750 °C, which is lower than the typical sintering temperature of ~900 °C needed to achieve good particle connectivity and optimal electrochemical activity. This lower temperature was chosen because the current reactor design cannot withstand higher temperatures without compromising the structural integrity of the MLI and polymer housing. Moreover, the sintering process was done without sealing the cell to separate the hydrogen and air environments. Attempting to fully seal the cell during sintering could damage it, and removing a pre-sealed cell from a separate setup often causes mechanical stress, bending, or even breakage. Such damage can result in gas leakage when the cell is later integrated into the ceramic reactor.

Despite these limitations, the cell still showed stable operation and open-circuit voltages above 1.0 V. We believe that the performance can be improved in future work by optimizing the cathode sintering process, using alternative sintering techniques, or redesigning the reactor to tolerate higher operating temperatures. This study highlights that proper cathode sintering is a key factor in achieving high electrochemical performance in metal-supported SOFCs.

Demonstration of quick startup and safety test

The typical startup time for planar-type SOFCs is reported to be in the range of 15–30 minutes, which is a considerable drawback for portable applications23,24. The rapid cold start-up and substantial changes in operating conditions demanded by mobile applications are thus incompatible with typical SOFCs operated at high temperature ranges, particularly above 600 °C. Recently, Jeong et al.25 have demonstrated the cold start-up within a five-minute timeframe for mobile applications. The entire assembly system, comprising ceramic plates on which planar-type SOFCs were affixed and sealed with mica sheets using screws, was constructed accordingly. The assembly in consideration appears to be of a greater mass than our own assembly systems, likely due to the incorporation of ceramic plates and metal screws. In our system, the entire assembly was constructed using organic-based MLI mirrors and a polymeric-based SOFC box, which can be utilized as an auxiliary power unit (APU). In supplementary video V1, we have demonstrated that the startup time was approximately five minutes, during which the temperature reached ~600 °C. During the operational phase of the motor, the entire assembly was manually handled while it was in use. It is noteworthy that the ability to comfortably handle the entire assembly with a bare hand is an indication that the MLI is functioning effectively at an elevated temperature of operation. In addition to its thermal insulation properties, the YSZ ceramic reactor with a cantilevered structure also exhibits high resistance to thermal stress.

When SOFCs are operated at temperatures exceeding 560 °C in a mobile setting, there is a risk of mechanical damage to the system. This may result in intermixing of hydrogen and oxygen, which could potentially lead to an explosion. It is therefore imperative to consider the safety of these portable devices. In consideration of the mechanical damage to the SOFC assembly, the drilling of the SOFC reactor was conducted as depicted in the supplementary video V2. The drilling was conducted when the internal temperature reached approximately 640 °C. As illustrated in the supplementary Fig. S7, a sudden drop in temperature was observed at the point of drilling on the SOFC box, reaching less than 550 °C within 50 seconds. This was well below the ignition temperature of hydrogen (574 °C)26. As the drilling progressed, the mirror became damaged, resulting in a further decrease in temperature due to thermal radiation loss across the entire assembly. This led to the operating motor being shut down due to the temperature dropping significantly. It should be noted that the drilling test alone does not constitute a complete safety evaluation. The test served as a preliminary proof-of-concept to show that damage to the insulation structure (e.g., from mechanical puncture) leads to a rapid thermal shutdown. To thoroughly investigate the system’s safety, several additional factors must be considered, which are included in this Supplementary Information as part of the future development plan.

Discussion

This study presents a potential methodology for the development of the lightest handheld SOFC module for portable applications using the small planar button cell27. A bespoke design was created using laser processing on YSZ sintered ceramic substrates, with the integration of a metal-supported SOFC, encompassing both fuel and oxygen inlets and outlets. The assembly was then integrated into a 3D-printed box with a heater and thermal couples. Finally, the electrochemical performance demonstrated, along with the ability to insulate the exterior of the module for a handheld handling device. Furthermore, this study presents a distinctive opportunity to significantly alter the thermal insulation of the SOFC box in ways that conventional techniques were unable to accomplish. The supplementary video V1 illustrates the functionality of a handheld SOFC in an operational state at an elevated temperature. The device demonstrates a startup time of less than five minutes, which is a crucial attribute for portable or any energy-related devices.

A comparison of the portable application with smaller planar SOFC cells reveals significant advantages in terms of ease of ceramic processing/ fabrication. The fabrication of smaller planar SOFCs can be achieved using simple pressing techniques, dip coating, or spin coating. This approach is presumed to be a more cost-effective alternative to conventional techniques. However, micro SOFCs necessitate the utilization of sophisticated and costly coating processes, such as sputtering or ALD, which are not feasible for large-scale cells6. Nevertheless, these processes can also be employed in the fabrication of small planar cells to enhance their performance28,29. In addition to its manufacturing capabilities, small SOFCs can provide the compactness and lightweight design necessary for integration into miniature systems. Additionally, small planar cells provide efficient thermal management, extended operational lifetime compared to the state-of-the-art Li ion battery systems, rapid start-up, and straightforward handling16.

The roll-to-roll (R2R) process is becoming increasingly prevalent in the fabrication of low-cost, large-scale structures, offering the potential for defect-free microstructures and high-performance SOFC devices30,31,32. Nevertheless, this technology can be readily and economically employed for small-scale planar SOFC technology, not only in the context of SOFC device fabrication but also in micro-space reactors with bespoke microchannel designs, which could potentially accelerate the growth of portable SOFC industries in the future.

The maintainability of thermal insulations can be readily achieved through the deployment of lightweight organic-based MLI, which appears to be an optimal solution for portable applications. An alternative option is the utilization of thermally durable organic materials-based MLI systems. The utilization of high-insulation, low-thermal-conductivity organic materials enables a brief start-up period for SOFCs, an overall lightweight system, and the provision of safety in the event of accidental structural damage to the system, as we demonstrated in the drilling test of SOFCs (Supplementary video V2). The advantages render smaller planar SOFC stacks particularly well-suited to portable applications, including mobile power units, portable generators, and even certain automotive applications.

The micro-space within the ceramic reactor offers several advantages, including the miniaturization of the system, an increased surface tension of the fluid flow path and a higher fuel flux. Additionally, the micro-space can be coated in silver, which serves as a current collector. The SOFC systems, which include the above-mentioned specifications, do not require additional components, thus offering an additional benefit for portable systems. Furthermore, the absence of additional metallic interconnectors in this system precludes the potential for performance degradation over time.

This work demonstrates the potential use of lightweight, thermally insulated handheld micro-spaced systems in conjunction with the integration of single small metal-supported SOFCs, which exhibit favorable electrical performance at low temperature operation. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to fully elucidate the role of fuel integration systems, stacks of small planar SOFCs, feedback control systems and real testing in a range of applications, including unmanned aerial vehicles, compact robotic devices and other low-power portable devices.

Materials and methods

Simulation of thermal insulation and stress in the designed ceramics

Thermal stress and heat flux simulations were conducted using the Autodesk Fusion 360® software. The cantilevered structure, double-cantilevered structure and planar structure were used for simulation models. The temperature was set to 800 °C (the center area) and the edge of the model was set to 20 °C. The material information is shown in Table T2.

In order to demonstrate the operational feasibility and compatibility of integrating planar SOFC into the ceramic reactor along with the microchannel for fuel fluid, a Macor® (Corning Inc.) was employed as the machinable ceramic material. The simple planar configuration with a cantilevered structure (with a thickness of 1.1 mm) was designed using Autodesk Fusion 360 with the objective of accommodating the planar-type SOFC. Fig. S1 (Supplementary information) illustrates the structure of the ceramic material utilized in the simulations. The machinable glass-ceramic was micromachined to fabricate the cell mount and microchannels (0.5 × 0.6 mm) for supplying fuel. Also, the length of the cantilever is 4 mm. To evaluate EMF and the thermal shock resistivity, A planar cell (The Fuel Cell Store, Product Code: 6201604) was integrated into the cantilevered structure. The cell area was heated by a butane gas burner. 95% hydrogen was supplied through the microchannel (5 ml/min). The EMF was measured using an electrical measuring device (Pine Research Instrumentation Inc., USA), and the surface temperature distribution of the device was monitored by an infrared camera.

Ceramic processing

Following the successful operational validation of electrolyte-supported cells in Macor® ceramics, the utilization of YSZ ceramics was undertaken, as it has been reported to possess high thermal stability, high mechanical strength, lower thermal conductivity, and a high degree of market availability33,34,35,36. The YSZ powders (TZ-3Y, Tosoh, Japan) were uniaxially pressed in a 67 mm circular die and sintered at 1350 °C for 2 hours. The thickness of the YSZ substrate was 0.3 mm. The obtained YSZ ceramic substrate was cut into the desired shape by fiber laser (SmartDIYs, LM110C), and the custom-designed channel path for fuel and oxygen gas was also created by the fiber laser. The laser cutting was performed at a laser speed rate of 500–200 mm/s under 100% power. Following laser processing, the YSZ substrates were rinsed with water to remove residual particles and debris, particularly those partially fused or lodged between the cut and uncut regions of the ceramic due to localized melting.

Measurement of thermal stress in YSZ cantilevered structure by X-ray

To evaluate the internal stress within the YSZ cantilevered structure, a series of fabrication and measurement procedures was conducted. First, a YSZ disk was fabricated by pressing 3.5 g of TOSOH 3YSZ powder at a pressure of 19.2 MPa. The pressed disk was then pre-sintered at 900 °C using a muffle furnace (MASUDA NMF-120B) to achieve the necessary mechanical strength for subsequent processing. Following the pre-sintering, flow channels were precisely etched into the disk using a UV laser (Acon Co., ALUV-5W). The disk was then fully sintered at 1400 °C in an electric furnace (Full Tech) to consolidate the structure. Next, a cantilevered structure was created on the sintered disk using a 30 W fiber laser (SmartDIYs, LM110C), which allowed for precise cutting and shaping of the structure. Following the creation of the cantilevered structure, a stainless-steel heater (SUS304) was fabricated and bonded to the disk using Aron ceramic bond (Toagosei) under 100 °C pressure for 5 minutes to ensure good adhesion. The entire assembly, now including the bonded stainless-steel heater, was heated to 600 °C using an electric furnace (Nittoka) to simulate the operational conditions. For the measurement of thermal stress, the stainless-steel heater was connected to a power supply unit (KIKUSUI PVVR401H). The temperature distribution was first recorded before the heater was energized. The heater was then powered using a constant voltage power supply, and as the temperature increased and reached equilibrium, the output was incrementally raised. Temperature measurements were taken at various power outputs (5 W, 10 W, 15 W, and 20 W) corresponding to heater temperatures of 100 °C, 200 °C, and 300 °C. The thermal stress generated in both structures is evaluated by X-ray analysis (Pulstec, Model: μ-X360J, Japan). The maximum temperature observed at the center of the structure was used as the reference point for analyzing the thermal stress distribution within the YSZ cantilevered structure.

Preparation of SOFC box with MLI

The box was produced using a specialized custom design, created with the assistance of high-temperature resin provided by the 3D printing instrument (Formlab, USA). Following the printing process, the box was subjected to washing and curing at 160 °C for a period of two hours in an oven. This innovative approach permits the integration of a microfabricated ceramic substrate within the box. The box incorporates both fuel and oxygen inlet and outlet ports, in addition to a dedicated channel for the silver film current collector. In order to maintain the temperature of the SOFC box and the thermal insulation outside of the box, a layer of three Al-coated polyimide films (UTC-025R-AANN, Orbital Engineering Inc.) was installed on the top and bottom sides of the ceramic reactors. A total of six mirrors were incorporated into the SOFC box, arranged in three layers on the top and three on the bottom. The spacing between mirrors was maintained at 2 mm.

Simulation and experimentation of the MLI system

In order to achieve the desired thermal insulation of the SOFC systems, organic-based MLI was employed in the 3D-printed box. The 3D-printed box consists of two halves where the ceramic microchannel reactor, heaters, and thermocouple were attached for thermal stress studies. This study examines the influence of thermal insulation on the number of mirror layers, with a focus on the comprehensive temperature profile, encompassing both internal reactor and external box conditions. The spacing between mirrors was assumed to be 2 mm. ANSYS Fluent was utilized for numerical simulation with a maximum mesh limited to ~900,000 tetrahedral mesh and double precision. The modes of heat transfer, namely, conduction (Qcond), convection (Qconv), and radiation (Qrad), were included in the simulation as well as material properties from the FLUENT database, as illustrated in supplementary Fig. S5. A comprehensive account of the simulation processes, parameters, and experimental details can be found in the supplementary information, where the details are discussed in greater depth.

Cell integration and its performance evaluation

The metal-supported SOFCs supplied by TAIYO YUDEN Japan were used in this study. More details about the supplied device can be found in the link (https://www.yuden.co.jp/en/product/solutions/ms_sofc/). The supplied SOFCs were integrated in the microfabricated YSZ substrate by glass sealant (supplied by SCHOTT, Germany) and heat-treated at 700 °C for 20 minutes. Thermal systems were employed, similar to MLI systems. The electrochemical performance of the microfabricated based planar SOFC reactors was performed in hydrogen (3 vol% H2O) as fuel and synthetic air as oxidant. Current-voltage curves and impedance measurements were performed by potentiostat (Pine Research, wave100, USA) in the temperature range of 480–630 °C in a different interval of temperature. The obtained impedance spectrum was analyzed using the Zsimpwin software. The polarization resistance of the cells was analyzed by DRTtools software in order to gain insight into the rate-limiting steps involved in the electrochemical processes37,38.

Conclusion

This study has effectively showcased a groundbreaking concept of Micro-TAS, which encompasses the development of reaction chambers, microchannels, and current collectors. An extremely straightforward and lightweight organic-based MLI system has been shown to be remarkably efficient for the thermal regulation of the overall systems. An internal temperature of ~600 °C was attained at the reactor’s core within 5 minutes. This can be comfortably held in the hand while the SOFC operates at elevated temperatures. The MLI structure not only provided high thermal insulation but also offered a safety feature where, in the event of damage, the system automatically cooled down. The design based on cantilevered-type ceramic reactors has been shown to be highly thermally stable. In this Micro-TAS, a basic type of small planar button cells was utilized and successfully demonstrated good performance. However, there is a significant need for further enhancement of electrochemical performance in future endeavors. Further investigation is required to fully elucidate the role of fuel integration systems, stacks of small planar SOFCs, feedback control systems and real testing in a range of applications, including unmanned aerial vehicles, compact robotic devices and other low-power portable devices.

References

Jayakumar, H. et al. Powering the internet of things. ISLPED '14: Proceedings of the 2014 international symposium on Low power electronics and design In: 375–380 (2014).

Bieberle-Hütter, A. et al. A micro-solid oxide fuel cell system as battery replacement. J. Power Sources 177, 123–130 (2008).

Wachsman, E. D. & Lee, K. T. Lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. Science 334, 935–939 (2011).

Muecke, U. P. et al. Micro solid oxide fuel cells on glass ceramic substrates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 3158–3168 (2008).

Baertsch, C. D. et al. Fabrication and structural characterization of self-supporting electrolyte membranes for a micro solid-oxide fuel cell. J. Mater. Res. 19, 2604–2615 (2004).

Tsuchiya, M., Lai, B.-K. & Ramanathan, S. Scalable nanostructured membranes for solid-oxide fuel cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 282–286 (2011).

Dewa, M. et al. Recent progress in integration of reforming catalyst on metal-supported SOFC for hydrocarbon and logistic fuels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 33523–33540 (2021).

Shao, Z. et al. A thermally self-sustained micro solid-oxide fuel-cell stack with high power density. Nature 435, 795–798 (2005).

Lim, Y. C., Kouzani, A. Z. & Duan, W. Lab-on-a-chip: a component view. Microsyst. Technol. 16, 1995–2015 (2010).

Jin, J. & Nguyen, N.-T. Manipulation schemes and applications of liquid marbles for micro total analysis systems. Microelectron. Eng. 197, 87–95 (2018).

Xu, X., Zhang, S., Chen, H. & Kong, J. Integration of electrochemistry in micro-total analysis systems for biochemical assays: recent developments. Talanta 80, 8–18 (2009).

Becht, M., Morishita, T. & Shiohara, Y. Thin film growth and surface analysis of CeO2 prepared by MOCVD. In: Advances in Superconductivity VIII (eds. Hayakawa, H. & Enomoto, Y.) 993–996 (Springer Japan, Tokyo, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-66871-8_224.

Zhou, Q. et al. Performance of high-temperature lightweight multilayer insulations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 211, 118436 (2022).

Tychanicz-Kwiecień, M., Wilk, J. & Gil, P. Review of high-temperature thermal insulation materials. J. Thermophys. Heat. Transf. 33, 271–284 (2019).

Spinnler, M., Winter, E. R. F. & Viskanta, R. Studies on high-temperature multilayer thermal insulations. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 47, 1305–1312 (2004).

Udomsilp, D. et al. Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells with exceptionally high power density for range extender systems. CR-PHYS-SC 1 (2020).

Dogdibegovic, E. et al. Scaleup and manufacturability of symmetric-structured metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 489, 229439 (2021).

Tucker, M. C. Progress in metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells: a review. J. Power Sources 195, 4570–4582 (2010).

Jiang, Z. et al. Electrochemical characteristics of solid oxide fuel cell cathodes prepared by infiltrating (La,Sr)MnO3 nanoparticles into yttria-stabilized bismuth oxide backbones. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 8322–8330 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. A broad stability investigation of Nb-doped SrCoO2.5+δ as a reversible oxygen electrode for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, F891 (2016).

Yamagishi, S., K, C. & Ito, D. Development of all-solid-state batteries and fuel cells using material technology from multilayer capacitors. Micromeritices 68, 9–20 (2025).

Dogdibegovic, E., Wang, R., Lau, G. Y. & Tucker, M. C. High performance metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells with infiltrated electrodes. J. Power Sources 410–411, 91–98 (2019).

Qin, X. et al. Solid oxide fuel cell system for automobiles. Int. J. Green. Energy 1, 10 (2022).

Hennessy, D. T. Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Development for Auxiliary Power in Heavy Duty Vehicle Applications. https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/progress09/v_j_2_shaffer.pdf (2010).

Jeong, H. et al. Advancing towards ready-to-use solid oxide fuel cells: 5 min cold start-up with high-power performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 7415–7421 (2023).

Yang, F. et al. Review on hydrogen safety issues: incident statistics, hydrogen diffusion, and detonation process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 31467–31488 (2021).

Yamada, T. et al. Small fuel cell portability. (2024).

Garbayo, I. et al. Full ceramic micro solid oxide fuel cells: towards more reliable MEMS power generators operating at high temperatures. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3617–3629 (2014).

Kim, K. J. et al. Micro solid oxide fuel cell fabricated on porous stainless steel: a new strategy for enhanced thermal cycling ability. Sci. Rep. 6, 22443 (2016).

Li, J., Bishop, S., Langdo, T. & Blackburn, B. Roll-to-Roll SOFC Manufacturing for Low Cost Energy Generation. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1515410 (2019).

Shin, J. et al. Suppression of processing defects in large-scale anode of planar solid oxide fuel cell via multi-layer roll calendering. J. Alloy. Compd. 812, 152113 (2020).

Kim, J. et al. Enhanced sinterability and electrochemical performance of solid oxide fuel cells via a roll calendering process. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 9958–9967 (2019).

Garvie, R. C., Hannink, R. H. & Pascoe, R. T. Ceramic steel?. Nature 258, 703–704 (1975).

Swain, M. V. Shape memory behaviour in partially stabilized zirconia ceramics. Nature 322, 234–236 (1986).

Hannink, R. & Kelly, P. & Muddle, B. Transformation toughening in zirconia-containing ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83, 461–487 (2000).

Hu, L., Wang, C.-A. & Huang, Y. Porous yttria-stabilized zirconia ceramics with ultra-low thermal conductivity. J. Mater. Sci. 45, 3242–3246 (2010).

Wan, T. H., Saccoccio, M., Chen, C. & Ciucci, F. Influence of the discretization methods on the distribution of relaxation times deconvolution: implementing radial basis functions with DRTtools. Electrochim. Acta 184, 483–499 (2015).

Saccoccio, M., Wan, T. H., Chen, C. & Ciucci, F. Optimal regularization in distribution of relaxation times applied to electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: ridge and lasso regression methods - a theoretical and experimental study. Electrochim. Acta 147, 470–482 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the following funding sources: JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Grant Numbers 23K26749 and 23K21047; the NEDO Project for the Promotion of Young Researchers in Industry-Academia-Government Collaboration; and the ERCA Innovative Research and Development Program (Young Researcher Category). This research was partially supported by joint research funds from Futaba Industrial Co., Ltd. and TAIYO YUDEN Co., Ltd. The authors would like to thank Prof. Ken-ichi Katsumata of Tokyo University of Science for his valuable advice regarding catalyst design and related discussions. The authors also acknowledge Futaba Industrial Co., Ltd. for their insightful suggestions on the device design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bishnu Choudhary: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and conceptualization. Gia Ginella Carandang: writing—review and editing, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. Shinichi Yamagishi, Saki Tada, Chie Kawamura: writing—review and editing, methodology, conceptualization. Yasuko Yanagida: project administration, writing, review and editing, conceptualization, and funding acquisition. Tetsuya Yamada: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choudhary, B., Carandang, G.G., Yamagishi, S. et al. A high-thermal-insulation and portable microreactor for integrating widely used planar-type SOFC and enabling handheld power generation. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01072-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01072-5