Abstract

This study addresses the issue of traditional surface acoustic wave (SAW) tag failure under high-temperature conditions by proposing a SAW tag based on a multilayer structure of SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3. The structure has been simulated using the finite element method/wave-number domain analysis (FEM/WDA) approach, which reveal the effects of reflector topological parameters on the scattering characteristics of SAWs. Compared with Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3, the bulk wave scattering in the multilayer structure is reduced by 50%. In the micro-nanofabrication of the tag, a low-roughness, high-density SiO2 film is prepared using physical vapor deposition (PVD). Test results indicate that the tag exhibits a temperature coefficient of frequency (TCF) of −32.38 ppm/°C over a wide temperature range of 30–600°C. After undergoing thermal shock at 600 °C for 336 h, the time-domain reflection amplitude decreases by less than 1%, demonstrating that the SiO2 protective layer effectively suppresses the high-temperature decomposition of LiNbO3 and reduces the agglomeration rate of Pt electrodes. Experimental results confirm that the proposed high-temperature-resistant SAW tag maintains stable performance under prolonged exposure to 600 °C environments. The tag has been installed on the surface of a steel ladle in a steel plant, demonstrating excellent reliability in a vacuum degassing environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As industrial manufacturing advances toward intelligentization, radio frequency identification (RFID) technology is crucial in enabling precise equipment identification, optimizing manufacturing processes, and enhancing production efficiency. The demand for wireless identification and tracking of equipment in high-temperature environments exceeding 250 °C is increasing rapidly. For instance, in automotive painting lines, tags operate at 250 °C, in the metallurgical industry, tags used for steel slag ladles operate at temperatures exceeding 300 °C1,2. To date, no existing system has met the application requirements for identifying equipment such as ladles in vacuum refining furnaces or aluminum alloy molds with temperatures reaching 600 °C3,4,5.

Surface acoustic wave (SAW) tags based on piezoelectric substrates fundamentally differ from semiconductor-based RFID technologies by eliminating the need for continuous radiofrequency power supply. The fundamental principle of SAW RFID is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The SAW RFID reader emits electromagnetic waves that are directly converted into SAWs by the interdigital transducer (IDT). The SAW propagates through a reflector array, generating uniquely coded SAWs that subsequently return to the IDT. The IDT reconverts these pulses into encoded electromagnetic waves, which are then transmitted back to the reader6,7. The SAW tag is the most promising candidate in high-temperature identification and tracking applications. Existing SAW tags can withstand prolonged exposure to temperatures ranging from 200°C to 400 °C8.

SAW tags utilize a series of aligned metal electrode reflectors for pulse position encoding9. According to Shannon’s information theory, the encoding capacity depends on the product of the bandwidth occupied by the encoded information and the temporal duration of the information. Consequently, the device must use substrate with large electromechanical coupling coefficient, such as lithium niobate (LiNbO3, LN) single crystal. However, when the temperature exceeds 400 °C, the substrate begins to decompose10, and the low-resistivity metal electrodes start to agglomerate11, leading to a rapid degradation in device performance. Although recent advances in high-temperature SAW sensors have provided reference solutions for developing SAW RFID systems capable of operating at 600 °C12,13,14,15, such as LiNbO3/SiO2/Si structures12, SiO2/lanthanum gallium silicate (LGS) structures13, further breakthroughs in material systems and design challenges are required due to the following reasons:

-

1.

Substrates such as LGS, gallium phosphate (GaPO₄), and AlN/sapphire, which are used for high-temperature sensors, are unsuitable for SAW tag design due to their low electromechanical coupling coefficients16,17.

-

2.

Dielectric thin films such as SiO2 and Al2O3 can improve the temperature stability of substrates and metal electrodes12,13. However, the wave mode in delay-line structures using in SAW tags undergoes a transition from Rayleigh wave mode to dispersive waves, whose propagation loss suppression have to be especially considered.

-

3.

When SAW propagates through reflectors composed of only a few metal electrodes, strong bulk wave scattering occurs18. However, no systematic study has been conducted on the relationship between SAW scattering and the topological parameters of reflectors embedded within dielectric thin films.

In this research, a high-temperature-resistant layered structure based on a 128°YX-LiNbO3 substrate covered with a SiO2 dielectric protection layer has been proposed. A finite element method (FEM) model of the layered structure has been established to accurately analyze the SAW scattering characteristics with the protection layer. A series of micro-nano fabrication processes and high-temperature packaging have been explored. The responses of the tag have been systematically studied over a temperature range of 30°C to 600°C. The practical application tests indicate that SAW tags operating at 600°C have been realized.

Optimization design of SAW tags

The layered SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 SAW tag structure designed in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1b. This structure utilizes a 128°YX-LiNbO3 substrate with a high electromechanical coupling coefficient, facilitating the realization of SAW tags with a wide bandwidth. The electrodes are made of Pt metal, which has a Tammann temperature of up to 750 °C19. The SiO2 protection layer serves multiple functions: it suppresses the high-temperature decomposition of LN, reduces the agglomeration rate of Pt electrodes, and provides temperature compensation, thereby minimizing the center frequency shift of the SAW tag under high-temperature conditions. To design a high-performance SAW tag, it is essential to optimize the thickness of the SiO2 protective layer as well as the topological parameters of each set of reflectors.

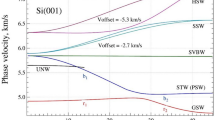

Determination of SiO2 thickness

When the SAW mode excited by the IDT contains spurious modes, these modes can cause energy attenuation and extra response distortion. In order to investigate all the modes excited by the IDT at different SiO2 thicknesses, a simulation model consisting of a multi-layer dielectric/IDT/substrate structure shown in Fig. 1c has been developed, where only the IDT structure is introduced. The model is surrounded by periodic boundary conditions, and fixed constraints are applied at the bottom to simulate the practical device being mounted in a package. In the model, the period of the Pt electrode is set to 3.87 µm according to the working frequency of tags, and the thickness is set to 100 nm for fabrication feasibility and compromise between high-temperature stability and device performance. Thinner electrodes suffer from poor adhesion, while thicker ones increase bulk wave scattering.

According to the simulated the admittance response of the IDT (see Fig. 1d), all the excited wave modes can be observed. When the SiO2 layer thickness is below 600 nm, a strong shear horizonal (SH) spurious mode mixes with the main mode of Rayleigh wave. When the thickness increases to 700 nm, the dominance of the Rayleigh wave is significantly enhanced, and the SH spurious mode amplitude rapidly decreases. Although a thicker SiO2 layer can further suppress the SH spurious mode, it significantly increases the thermal stress within the film during SiO2 fabrication, raising the risk of film cracking and causing the SAW mode to move further from the surface, which increases propagation loss.

SAW scattering of the reflector in the SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 layered structure

We have developed the finite element method/wave-number domain analysis (FEM/WDA) approach20, to analyze the Rayleigh wave scattering characteristics of the reflector embedded in the SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 layered structure. This method performs simulation by extracting the surface displacement field, in the reference model without the reflector, after applying appropriate absorbing boundaries and damping region configurations, the SAW reflection error is controlled to below 10⁻³. This accuracy is sufficient to distinguish the changes in reflection coefficient caused by variations in the reflector topological parameters.

SAW scattering comparison between layered SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 and Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 structures

The tag features a center frequency of 925 MHz. Simulations near the center frequency have been conducted to compare the SAW scattering characteristics of two structures: Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 and SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3, as shown in Fig. 2a. The reflector array is set with four open-circuit (oc) grids and fixed metallization ratio (mr) of 0.5. The results reveal that the bulk wave scattering of the SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 structure is 50% lower than that of the Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 structure. Bulk wave scattering causes SAW energy to leak into the substrate, weakening the reflection signal and increasing the excitation power needed for tag operation. Therefore, the SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 structure is more suitable for designing SAW tags.

Relationship between SAW scattering and metallization ratio

The relationship between the scattering parameters of the reflector array and frequency is investigated for different metallization ratios. The reflector array is set with four open-circuit grids, and the corresponding simulation results are shown in Fig. 2b, where different curves represent the results for varying metallization ratios. The results demonstrate that the reflection coefficient exhibits a decreasing trend with increasing metallization ratio while the transmission coefficient initially decreases and subsequently rises. Concurrently, bulk wave scattering progressively intensifies as the metallization ratio increases.

Relationship between SAW scattering and the number of electrodes

The frequency-dependent scattering parameters under varying reflector electrode numbers with an open-circuit grid are systematically investigated in Fig. 2c, with a fixed metallization ratio of 0.5. The data demonstrate that increased the number of electrodes enhances the reflection coefficient while reducing the transmission coefficient. For tag design, a higher reflection coefficient can be achieved by incorporating additional electrodes. Furthermore, at the central frequency, configurations with more electrodes exhibit reduced bulk wave scattering. These findings indicate that prioritizing reflector configurations with more electrodes during tag design effectively minimizes bulk wave losses and enhances overall performance.

Determination of topological parameters of reflectors in SAW tag

For SAW tags, the reflector is arranged along the SAW propagation path. Typically, to achieve consistent reflection peak amplitudes, the reflection coefficient Ri of the earlier reflector arrays will be lower than that of subsequent arrays, Ri+1. Considering the SAW propagation loss factor L (the two-way loss of SAW between reflector arrays), the ratio factor S of adjacent reflection peak amplitudes, and the transmission coefficient T of the reflectors, the reflection coefficient between adjacent reflectors satisfies the following equation:

If the reflection coefficient of the initial reflector is known, the reflection coefficients of subsequent reflectors can be calculated sequentially using Eq. (1). Alternatively, the reflection coefficient of the previous reflector can be calculated in reverse, given the reflection coefficient of the terminating reflector.

The reflector topological parameters of SAW tags are highly diverse, and the corresponding scattering parameter database is extensive. When determining the reflector topological parameters based on different reflection coefficients, optimization selection becomes crucial. As shown in Fig. 3, the scattering parameter curves for different numbers of reflectors, obtained through simulation, are plotted on a data distribution surface defined by the equation BS = 1-R2-T2, where BS represents bulk wave scattering. For example, as the number of reflectors increases, the range of reflection coefficient covered becomes larger, while the bulk wave scattering decreases.

In the low-loss optimization selection of the reflector topological parameters, the reflection coefficient of 0.18 for the first set of reflectors is used as a specific example for analysis. The surface corresponding to a reflection coefficient of 0.18 is plotted on the data distribution surface. This surface intersects with the data distribution surface, resulting in an intersection line R1 = 0.18. Next, the intersections of this line with the scattering parameter curves are observed, and it is found that the R1 = 0.18 curve intersects with the scattering parameter curves of 4oc, 5oc, and 6oc reflectors. This phenomenon indicates that the same reflection coefficient can correspond to different topological parameter combinations for different numbers of reflectors. Therefore, it is necessary to perform low-loss optimization on the reflector. Further analysis is conducted by comparing the bulk wave scattering at each intersection point. The intersection point with the lowest bulk wave scattering, corresponding to the 6oc reflectors, is chosen as the marker for the reflector topological parameter combination. Based on the reflection coefficient, transmission coefficient, and bulk wave scattering values at this marker, the corresponding reflector array period and metallization ratio are identified in the scattering parameter database, and these are determined as the structural parameters for the first set of reflectors. Next, based on the reflection coefficient and transmission coefficient of the first set of reflectors, the reflection coefficient for the second set of reflectors is calculated using Eq. (1), with an assumed value of 0.23. Similarly, the surface for a reflection coefficient is plotted, and it intersects with the data distribution surface to generate the curve R2 = 0.23. This curve intersects with the scattering parameter curves for the 5oc and 6oc reflectors. At this point, low-loss optimization is again performed, and the reflector topological parameters corresponding to the point with the lowest bulk wave scattering are selected.

By following the above method and repeatedly applying the process, the topological parameters for each set of reflectors in the SAW tag are determined one by one. The above analysis indicates that, under the same reflection coefficient conditions, the more electrodes the reflector has, the higher the transmission coefficient and the lower the scattering loss. Therefore, during the selection of reflector topological parameters, it is preferable to choose reflector combinations with more electrodes, as this will be more beneficial in improving the performance of the tag.

The SAW tag designed in this paper uses 128°YX-LiNbO3 as the substrate, with a 100 nm thick metal Pt electrode and a 700 nm thick SiO2 protective layer. The structural parameters of each set of reflectors are determined according to the simulation results of the scattering parameters and the optimization principles. The configurations of the SAW tag are concluded in Table 1.

Results and discussion

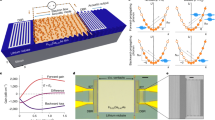

Fabrication of SAW tag

The LN substrate is pretreated, and the pattern is drawn using ultraviolet photolithography. Subsequently, a series of processes, including film deposition, stripping, dicing, bonding, fixing the substrate, and tag packaging, are carried out to fabricate the SAW tag.

The fabrication process of SAW tag is illustrated in Fig. 4a. A defect-free photoresist film is uniformly applied to the clean and dry LN wafer surface using the spin coating method. In general, the thickness of the photoresist is negatively correlated with the adhesion between the subsequent metal film growth and the substrate. However, excessively thick photoresist layers can cause difficulties in metal electrode deposition into the gaps during the film growth process, leading to an actual finger width smaller than the set value. Experiments have shown that for the deposition of a 100 nm thick metal film, setting the photoresist thickness to around 350 nm is most favorable for metal growth. A custom mask is used to fix the substrate on an x-y stage, and the corresponding pattern areas of the photoresist are exposed. After exposure, some of the photoresist undergoes a chemical reaction and hardens. The photoresist is then subjected to a hard bake to further solidify it. Afterward, a wet development process is used to chemically break down the unpolymerized remaining photoresist, resulting in a clear development of the device pattern.

After the precise transfer of the mask pattern onto the photoresist layer, metal electrodes are grown on the piezoelectric substrate surface through electron beam evaporation, with Ti and Pt metal films deposited sequentially. A 10 nm thick Ti layer is used as an adhesion layer, as it has strong diffusivity and can effectively ensure the integrity of the metal fingers during peeling. After the uniform metal film is grown on the surface, the excess photoresist and redundant metal on top are removed by lift off process, typically employing organic solvents such as acetone for cleaning. The substrate is then further cleaned in a plasma asher, resulting in the formation of the interdigitated transducer and reflector array patterns. We also attempted to fabricate Pt electrodes via sputtering deposition; however, the resulting electrodes exhibited poor pattern fidelity and incomplete lift-off characteristics.

In this study, two deposition processes, plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) and physical vapor deposition (PVD), are utilized in the growth of SiO2. As demonstrated in Table 2, the surface roughness of the films deposited by PVD is found to be significantly lower than that of PECVD, and the densification is superior, suggesting that the Rayleigh wave has a lower propagation loss during propagation. The PVD process entails the deposition of SiO2 through the physical bombardment of the target, with a low substrate temperature and minimal warming. This process circumvents the internal stress and thermal deformation mismatch issues associated with the high-temperature reaction of PECVD. Therefore, PVD is utilized in this study to deposit the SiO2 layer.

Subsequently, dry polishing and Chemical Mechanical Planarization (CMP) are employed to precisely thin the SiO2 layer to a thickness of 700 nm, achieving ultra-precision flattening of the SiO2 surface. The SiO2 on the pad of IDT is etched away using an overlay process to expose the electrodes for bonding. The prepared wafer is shown in Fig. 4b, the microscopic view of reflector of tag is shown in Fig. 4c.

Finally, dicing is performed to separate individual SAW RFID chips, which are bonded to a package made of kovar alloy packaging (Fig. 4d). To ensure reliable chip connections, we selected 1.25 mil (32 µm) gold alloy bonding wire, known for its excellent oxidation and creep resistance. Tensile tests at room temperature show a consistent break-off force above 20 g, meeting the mechanical requirements for high-reliability packaging. The packaging process is completed, resulting in the fully assembled SAW tag, the internal structure of tag is shown in Fig. 4e.

High-temperature performance testing of SAW tag

An automated high-temperature testing platform is developed to evaluate the performance of the SAW tag at different temperatures, as shown in Fig. 4f. This platform provides a programmable high-temperature environment, allowing for real-time measurement and automatic recording of data such as temperature, signal amplitude, and time delay during the heating and aging processes.

The experiment utilizes a Kejing OTF-1200X muffle furnace capable of operating temperatures up to 1200 °C with programmable temperature profiles. The tag, laser-welded onto high-temperature-resistant RF feedlines, is placed inside the furnace. The feedlines are directly connected to a Tektronix TTR500 vector network analyzer (VNA) for S11 parameter measurement and data acquisition via a computer. Ambient temperature is monitored using a K-type thermocouple and transmitted to the computer via a temperature data logger. Custom software is developed for automated data logging and visualization, enabling periodic recording of furnace temperature and S11 parameters. During high-temperature performance testing, the time delay and amplitude of the SAW tag’s reflection peaks are measured. Since conventional VNA only provides S11 parameters, an inverse Fourier transform is applied to the measurement results to extract the tag’s time-domain response.

The muffle furnace temperature is configured as follows: starting from ambient temperature, the system underwent heating followed by cooling back to ambient temperature for annealing. Subsequently, a second heating phase is executed, spanning 30 °C to 650 °C. Each temperature segment maintained a 1-h dwell time to ensure thermal equilibrium at the tag location within the furnace. Data are recorded at 5-min intervals throughout the process.

The measured frequency response S11 under varying temperatures is shown in Fig. 5a, b. As temperature increases, the center frequency of the S11 response exhibits a downward shift, with a total frequency deviation of approximately 10 MHz across the 600 °C temperature range. This confirms the effective temperature compensation provided by the positive frequency-temperature coefficient of SiO2. The temperature coefficient of frequency (TCF) is calculated as −32.38 ppm/°C based on the relationship between center frequency shift and temperature. Simultaneously, the amplitude fluctuation of S11 decreases significantly beyond 600 °C, indicating reduced energy reflection from the grating structures.

The time-domain response shown in Fig. 5c, d reveals five distinct peaks corresponding to the five reflector groups (excluding the peak at 0.4 μs, attributed to acoustic wave reflection at the IDT termination). Across temperatures up to 600 °C, the reflection amplitudes remain stable, a result of optimized low-loss reflector topological parameters. However, at temperatures exceeding 600 °C, the time-domain reflection amplitudes diminish, indicating increased insertion loss. The primary mechanism involves temperature-induced center frequency drift beyond the optimized bandwidth of the broadband reflectors, leading to reduced reflected energy. Additionally, prolonged testing caused significant oxidation in the copper cables of the high-temperature-resistant RF feedlines. Critically, this amplitude reduction does not signify irreversible material degradation in the SAW tag. The tag remains functional at 730 °C, and upon cooling to ambient temperature with the replacement of oxidized feedlines, the reflection amplitude recovers to its original high level.

To further investigate the performance of the tag under prolonged high-temperature conditions, a 600 °C high-temperature lifetime test was conducted. The experimental results, shown in Fig. 5e, indicate that over different time periods at 600 °C, the time-domain amplitude fluctuation of the tag remained below 1%. The SiO2 layer effectively protects the electrodes and substrate in high-temperature environments, providing strong evidence for the effectiveness and stability of the layered SAW tag structure proposed in this study. Compared with previously reported high-temperature-resistant delay line SAW device (Table 3), the SAW tags fabricated in this study not only withstand higher temperatures and longer durations but also exhibit enhanced stability after optimization of the reflector topological parameters. These advantages underscore the application potential of the proposed SAW tag.

Impact of SiO2 protective layer on Pt electrodes and LiNbO3 substrate at high temperatures

This study investigates the influence of the SiO2 protective layer on the structural integrity of Pt electrodes and LiNbO3 substrates. Comparative thermal shock testing at 600 °C is conducted on Pt electrode configurations with and without SiO2 protection. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is employed to analyze microstructural evolution. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, unprotected Pt electrodes subjected to 600 °C thermal shock for 168 h exhibit a transition from initial smooth morphology to dispersed spherical structures, accompanied by increased electrode width and continuous void formation, indicating severe Pt agglomeration.

For Pt electrodes protected by a 700 nm SiO2 layer, direct observation of Pt morphology via SEM is impeded by the SiO2 layer. To address this, SiO2 was selectively etched using an inductively coupled plasma (ICP) reactive ion etching system. Fluoride-based gases (e.g., CF4, SF6) are employed, where fluorine ions react with silicon to form volatile silicon tetrafluoride, which is subsequently evacuated by vacuum pumps. As shown in Fig. 6c, even after 168-h thermal shock testing at 600 °C, the SiO2-protected Pt electrodes retain their original smooth and intact morphology without structural degradation. These results confirm that the SiO2 protective layer significantly enhances electrode stability at high temperatures, effectively suppressing metal film agglomeration under thermal stress.

At the same time, the experiment investigates the effect of the SiO2 protective layer on the LiNbO3 material. Before and after the 600 °C thermal shock, the microstructure of the LiNbO3 without the SiO2 layer shows significant changes. As shown in Fig. 6d, e, the surface of the sample is smooth and flat before the shock, but after the shock, numerous bubbles appear on the surface, and the structure is altered. In contrast, the LiNbO3 with the SiO2 layer structure maintains a smooth and flat surface at 600 °C, with no noticeable defects, as shown in Fig. 6f. Since LiNbO3 piezoelectric substrate material is prone to phase transitions at high temperatures, which can degrade the tag performance, the experiment uses ICP to remove the SiO2 protective layer and performs physical phase analysis of LiNbO3 using an X-ray Powder Diffractometer (XRD).

Figure 6g presents the XRD analysis results of LiNbO3 substrates with and without SiO2 protection after thermal shock testing. For the unprotected LiNbO3 substrate, a new peak emerges at 2θ = 24.6°, which is indexed to the LiNb3O8 phase. In stark contrast, this characteristic peak is absent in the XRD pattern of the SiO2-protected LiNbO3 substrate. This result conclusively demonstrates that the SiO2 layer effectively suppresses high-temperature decomposition reactions in LiNbO3, thereby preserving its crystalline structural integrity.

Application analysis

The developed high-temperature-resistant SAW tag have been successfully implemented in ladle identification and tracking systems at a steel plant. As shown in Fig. 7a, the tag is electrically connected to high-temperature-resistant antenna via laser welding, forming SAW identifier mounted on the ladle surface (Fig. 7b, c). These ladles operate in a sustained 350 °C thermal environment and encounter temperatures up to 600 °C when processed through the vacuum degassing furnace.

Figure 8a, b demonstrates thermal imaging records of ladle surfaces exiting the vacuum degassing furnace, showing temperatures between 580 °C and 600 °C. As shown in Fig. 8c, d, identification antennas have been installed across multiple workstations, including converter tapping, hot repair, vacuum degassing furnace, and continuous casting. After one month of stable operation, the SAW tags consistently maintain reliable performance, fully validating the stability and reliability of the tags in harsh 600 °C molten metal environments. The application of these tags significantly reduces thermal loss during high-temperature molten metal transportation, demonstrating substantial long-term operational benefits.

Conclusion

To overcome the performance limitations of traditional RFID technology in high-temperature scenarios, SAW tags based on a layered SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 structure capable of stable operation in extreme environments up to 600 °C have been designed and fabricated. The FEM model reveals the impact of the reflector topological parameters on the SAW scattering characteristics. Specifically, by determining a 700 nm SiO2 protective layer thickness and combining it with the 100 nm Pt electrode, a balance between temperature compensation and electromechanical coupling performance was achieved. Experimental results show that the fabricated SAW tag exhibited excellent stability within a wide temperature range of 30 ~ 600 °C: the TCF is −32.38 ppm/°C, a reduction of 33 ppm compared to the −65 ppm/°C of the LN substrate tag without the SiO2 protective layer. After 336 h of thermal shock at 600 °C, the time-domain reflection amplitude decreases by less than 1%. This tag is installed on the surface of a steel ladle in a steel plant, demonstrating excellent performance in the 600 °C vacuum degassing environment and long-term high-temperature operation, significantly reducing heat loss during the molten metal transport process, thus validating its industrial practicality. This research provides an innovative solution for intelligent identification and tracking of equipment in high-temperature environments, and expands the application boundaries of SAW RFID technology through systematic material, design, and process optimization. Future work could further explore material systems compatible with even higher temperatures (such as 800 °C and above), optimize wide-band signal processing algorithms to enhance tag encoding capacity, and promote large-scale applications in various scenarios, thus providing stronger technical support for industrial smart manufacturing.

References

Pendar, M. R., Rodrigues, F., Pascoa, J. C. & Lima, R. Review of coating and curing processes: Evaluation in automotive industry. Phys. Fluids 34, 101301 (2022).

Meng, H. J. et al. Online recognition of manually spray-printed ladle numbers in complex dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 5020716 (2024).

Fachberger, R., Bruckner, G., Hauser, R. & Reindl, L. Wireless SAW based high-temperature measurement systems. Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and Exposition (2006).

Maufay, J. et al. Innovative NiAl electrodes for long-term, intermediate high-temperature SAW sensing applications using LiNbO3 substrates. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 16691–16698 (2023).

Floer, C. et al. SAW RFID devices using connected IDTs as an alternative to conventional reflectors for harsh environments. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 58, 1267–1274 (2020).

Plessky, V. P. & Reindl, L. M. Review on SAW RFID tags. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 57, 654–668 (2010).

Shi, R. C. et al. SAW tags with enhanced penetration depth for buried assets identification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 8863–8873 (2021).

Suresh, K. et al. A comparative survey on silicon based and surface acoustic wave (SAW)-based RFID tags: potentials, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 8, 91624–91647 (2020).

Plessky, V., Ostertag, T., Kalinin, V. & Lyulin, B. SAW-tag system with an increased reading range. in 2010 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS) 531-534 (IEEE, 2010).

Fachberger, R. et al. Applicability of LiNbO3, langasite and GaPO4 in high temperature SAW sensors operating at radio frequencies. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 51, 1427–1431 (2004).

Hieke, S. W. et al. On pinning-depinning and microkink-flow in solid state dewetting: Insights by in-situ ESEM on Al thin films. Acta Mater. 165, 153–163 (2019).

Baptiste, P. et al. LiNbO3/SiO2/Si POI heterostructure surface acoustic wave sensor for intermediate high temperatures. in 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Li, L., Peng, B., Yu, H. & Zhang, W. L. Temperature characteristics of langasite surface acoustic wave resonators coated with SiO2 films. Sens. Actuators A 279, 399–403 (2018).

Qiang, L., Yang, W. L., Chi, C., Li, H. Y. & Hong, X. Effect of SiO2 protective layer on LiNbO3 structured SAW resonators and temperature characteristics study. J. Micromech. Microeng. 33, 105014 (2023).

Shan, Q. C. et al. Fabrication of grooved LGS resonators based high temperature SAW sensors and analysis with FEM simulation. J. Micromech. Microeng. 32, 105005 (2022).

Nagmani, A. K. & Behera, B. A review on high temperature piezoelectric crystal La3Ga5SiO14 for sensor applications. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 69, 918–931 (2022).

Kim, T. et al. High-temperature electromechanical characterization of AlN single crystals. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 62, 1880–1887 (2015).

Han, T., Wang, W. B., Wu, H. D. & Shui, Y. A. Reflection and scattering characteristics of reflectors in SAW tags. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 55, 1387–1390 (2008).

Tiggelaar, R. M., Sanders, R. G. R., Groenland, A. W. & Gardeniers, J. G. E. Stability of thin platinum films implemented in high-temperature microdevices. Sens. Actuators, A 152, 39–47 (2009).

Zhang, Q. Z. et al. Wavenumber domain analysis of surface acoustic wave scattering from localized gratings on layered piezoelectric substrate. Ultrasonics 88, 131–136 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 12204305.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.T., R.S., and T.H. conceived the concept. Z.T., and R.S. performed the simulation analysis. Z.T., D.G., and H.L. contributed to the experiments and data analysis. Z.T., and C.L. carried out application analysis. All authors contributed through scientific discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Z., Shi, R., Guo, D. et al. A surface acoustic wave tag utilizing a multilayer structure of SiO2/Pt/128°YX-LiNbO3 for operation at 600 °C. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01084-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01084-1