Abstract

We present an optomechanical device platform for characterization of rheological, optical and thermal properties of fluids on the micron scale. A suspended silicon microdisk resonator with a vibrating mass of 100 pg and an effective probing volume of less than a pL is used to monitor properties of different fluids at rest. By employing analytical models for fluid-structure interactions, thermo-optical effects and thermal diffusion, our platform determines the viscosity, density, compressibility, refractive index and thermal conductivity of the fluid, in a compact measurement setup. A single measurement takes as short as 70 μs, and the employed power can be less than 100 μW, guaranteeing measurement at rest and in thermal equilibrium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liquids are ubiquitous: they form the natural environment for life’s mechanisms and are manifesting themselves in diverse industrial processes and cutting-edge printing or bio-technologies. Recent advancements in micro- and nano-fluidic science and applications have spurred an increasing demand for fluid characterization at micro- and nano-metric length scale, aiming at rheological, optical, thermal and other properties of the fluids either “at rest” or “in flow”1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

For example, nano-rheometry provides insight into the intricate behavior of biological systems9,10, shedding light on how cells regulate viscosity for their functions11,12. But understanding interdependent biological mechanisms actually requires a concurrent assessment of diverse physical parameters of the biological fluid at small spatial scale3. Integrating different sensing modalities on a single fluidic device platform is hence of prime importance when designing nanofluidic devices for biophysical or biomedical research8,13. This is illustrated by the case of sweat sensing, where rheological, thermal and chemical properties need to be analyzed at the level of a single ductal pore. The evolution towards multimodal sensors serves other applications of nanofluidics as well such as chemical synthesis14,15, neuromorphic computing16,17, or liquid cooling, where rheological and thermal properties of the fluids must be monitored. The petroleum, oil and food sectors, where micro-rheometry already plays a pivotal role, are also potentially concerned. Of particular importance are measurements on samples with volume down to nanoliters or even picoliters, especially when testing fluids4 containing proteins18, DNA, or other scarce or expensive constituents of interest. Optomechanical sensors seem adequate to address small volumes, as an optomechanical balance has recently measured a droplet of liquid down to a volume of an attoliter19. Scientists across many disciplines have proposed a variety of sensors to analyze rheological, optical and thermal properties of fluids2,4,5,6,20, generally using a distinct sensor to measure each category of properties.

For example, most of micro-rheometers reported to date are merely capable of measuring the viscosity and density of fluids21,22,23,24,25,26. In these devices, the vibrations of a membrane or cantilever at frequencies up to hundreds of kHz are detected, for example through monitoring reflection of a laser beam of a few mW. At variance, micro-rheometers based on ultrasonic transduction operate at a few megahertz and can determine the density and compressibility of a fluid, but extracting viscosity from these measurements is challenging27. These probes can operate in passive mode, where the vibrating element is excited by thermal fluctuations21, or in active mode, for example, with piezoelectric22,23,24,25 excitation of the vibration. Although active sensors offer superior performance, their practical operation in harsh environments can be constrained by the incompatibility of electrical signals. Optically-operated rheometers are an alternative approach, which employ the photothermal actuation of a membrane or the tracking of microparticles trapped in optical tweezers26,28. Despite the bulky free-space optical setups and precision alignment that they require, these sensors excel in determining the viscosity28 along with the density of fluids26. However, they do not say anything about the compressibility, nor about the optical and thermal properties of the fluid.

Here we report a single integrated optomechanical sensor that determines at the same time the viscosity, density and compressibility (speed of sound) of the fluid, as well as its optical refractive index and thermal conductance. The sensing device is immersed in the fluid and incorporates a small footprint (16μm × 16μm) suspended silicon microdisk resonator, which characterizes the fluid within an effective probing volume of less than a picoliter, within a measurement time as short as 70 μs. The disk serves as an optomechanical resonator in the ultra-high frequency range29,30, which extracts the fluid viscosity, density and compressibility with high accuracy, by fitting measurements of its mechanical vibrations with analytical fluid-structure models31. The employed optical power can be as low at 50 μW, guaranteeing minimum disturbance to the fluid. In addition to micro-rheometry, the low power optical response of the disk enables measuring the refractive index of the fluid with a resolution of 4 × 10−6RIU. By increasing the optical power to 1 mW and fitting the thermo-optical response, we extract the thermal conductivity of the fluid surrounding the sensor with an accuracy better than 3%. Through simultaneous non-invasive measurement of the rheological, optical and thermal properties of fluids, and measurement time and power orders of magnitude smaller than those of conventional fluid sensors, the demonstrated platform holds promise for efficient multimodal characterization of liquids on the micron scale.

Concept and implementation

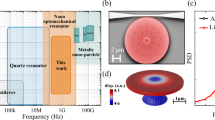

Let us start by illustrating the principle of the multiphysics measurement of the fluid by the disk. Figure 1a is a diagram of the interplay between the relevant physical degrees of freedom. The symbols M, O, and T correspond to the mechanical, optical, and thermal mode of the disk, respectively. As shown by the diagram, mechanical (M) and thermal (T) information is transferred to the optical mode (O), and then transduced onto the optical output signal. When the disk is immersed in the fluid, the rheological properties of the fluid impact the mechanical oscillations (M) of the disk, which modulate the optical mode (O) via optomechanical coupling and are imprinted onto the radio frequency (RF) components of the output light. A RF optomechanical spectrosocpy of the disk thus allows the rheological analysis of the fluid. In parallel, the thermal conductivity of the fluid influences temperature (T) variations in the disk, which induces variations in the refractive index and spectrally shifts the disk optical mode resonance (O). We can hence analyse the fluid’s thermal conductivity by performing a DC laser spectroscopy of the disk. Globally, RF and DC components of the detected output light hence provide access to rheological, optical and thermal properties of the liquid. Figure 1b–d shows numerical calculations of the velocity profile associated to the mechanical mode (M), electric field amplitude associated to the optical mode (O), and temperature profile (T) of the disk used in our implementation. Left (right) panels show the cross-section (top) views.

a Schematics of the physics involved. M and T influence O, which is optically read-out. Note the drawn reciprocal coupling between O and M (optomechanical force) and O and T (optical absorption), which can also be leveraged by the sensor. b–d Numerical modal simulations of a suspended silicon disk of radius 8 μm and thickness h = 220 nm in water, (b) radial displacement of the fundamental mechanical RBM of the disk, (c) electric field amplitude of an employed optical whispering gallery mode, (d) temperature distribution. Electron micrographs, (e) cross-section, (f) top-view of a suspended silicon disk of radius a = 8 μm and thickness h = 220 nm, adjacent to a tapered optical bus waveguide. Release holes were drilled through the disk to facilitate underetching of the BOX layer, but play a negligible role in relevant physical interactions. The inset provides a view of the pedestal after etching the top silicon disk. g Schematic representation of the measurement setup. PD: Photodetector. BS: Beam splitter. EDFA Erbium doped fiber amplifier, RFA Radio frequency amplifier, ESA Electronic spectrum analyser, ADC Analog-to-digital converter, FPC Fiber polarization controller

In our implementation, the disk has a radius R = 8 μm and is fabricated on a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer possessing a top silicon layer (< 100 >) of thickness h = 220 nm above a 1 μm thick buried oxide layer. Figure 1e shows a fabricated disk, after it was bisected in order to image the pedestal holding the structure. A top view of the disk resonator and its adjacent optical bus waveguide, positioned 200 nm away, is shown in Fig. 1f. Laser excitation and readout of the suspended disk are performed using near-field interaction between the bus waveguide and the disk optical mode. Grating optical couplers facilitate waveguide input and output coupling. Figure 1g presents a schematics of the measurement setup. The chip hosting the devices is placed within a custom decimeter-sized plastic pool, conveniently fillable with the fluid of interest using a syringe pump. Light from a fiber-coupled tunable laser excites the chip after passing through a fiber polarization controller (FPC). Another optical fiber collects the output light and is subsequently directed to both an RF (radio frequency) and a low-frequency (DC) detection unit via an asymmetric beam splitter (BS). In the RF path, the light is amplified by an erbium-doped amplifier (EDFA) before entering a fast photodetector whose electrical output is then amplified by an RF amplifier and analyzed by an electronic spectrum analyzer (ESA). The RF signal is analyzed to extract viscosity, density, and compressibility. Light in the DC path is in contrast detected by a slow photodetector, which provides the mean value of optical intensity and allows measuring the refractive index and thermal conductivity of the surrounding fluid. We provide here a system of coupled equations that model the behavior of the suspended disk surrounded by a fluid and enable these signal interpretations.

The first equation

is the equation of mechanical motion in the case of a harmonic oscillation (\(x=Re(\tilde{x}{e}^{j\omega t})\)), in absence of Langevin forces, and in presence of the fluidic force exerted by a compressible viscous liquid (\({\tilde{F}}_{fluid}=j\omega {m}_{s}\beta \tilde{x}\)). \({\omega }_{s}^{2}=\frac{{K}_{s}}{{m}_{s}}\) is the bare resonant angular frequency with Ks the vibration mode spring constant and ms the associated mass. β can be expressed in complex notation as follows:

with μ the liquid shear viscosity, ρ and ρs the density of liquid and solid, ks the mechanical wave vector in the bare solid resonator, k the acoustic propagation wave vector in liquid \(k=\frac{{\omega }_{s}}{c}\) with c the speed of sound in the liquid, J0(x) and H0(x) being Bessel and Struve functions. Expressions (1) and (2) were derived in ref. 31 and expressed in the compact form presented here in ref. 29.

The next equation

rules the evolution of the optical field a in the cavity, with Pbus the incident optical power in the adjacent waveguide, κ = κabs + κrad + κex the decay rate of the optical cavity mode, where κabs, κrad, κex are the absorption, scattering, and exchange loss rate, respectively. Δ = ωL − ωc is the laser to cavity detuning, and \({g}_{om}=-\frac{d{\omega }_{c}}{dx}\) is the parametric optomechanical coupling coefficient. The equation is written for a laser frequency far below the material bandgap, hence neglecting dispersion, such that a mere effective refractive index neff suffices in the description32.

The last equation

rules the heat propagation, with the thermal conductivity λ and volumetric heat source \(Q(r)=\frac{{P}_{abs}}{V}\), where Pabs = κabs∣a∣2 is the optical power absorbed within the disk of volume V. Let us now describe how these equations can be combined to analyze our experiments and locally obtain the multiphysical properties of the liquid.

Results

In order to demonstrate that our device and approach can lead to a multiphysical measurement of liquids, several binary water/glycerol mixtures of varying concentration are used as test liquids. Table 1 lists the tabulated mechanical, optical and thermal properties of each binary mixture. Here ρ, μ, c, n, λ stand respectively for the density, viscosity, sound velocity, optical refractive index and thermal conductivity of the liquid.

Let us first look at the RF part of the collected signal. Figure 2a shows the power spectral density (PSD) measured at the device output using the RF detection unit, when the disk is immersed in the water-glycerol solutions of distinct concentration. Mechanical resonances of the device appear in such spectrum. The frequency of the first radial breathing mode of the disk in air is 316 MHz, with a modal quality factor of 2200. After immersion in water, the mechanical oscillations are strongly damped by the liquid. With increasing glycerol concentration, the impact of viscous dissipation becomes more pronounced. It is accompanied by a frequency shift of the mechanical vibration towards lower frequency (Fig. 2a). The equations ((1), (2)) presented above enable us determining the frequency Ωm = Re(ω) and quality factor \({Q}_{m}=\frac{Re(\omega )}{2Im(\omega )}\) of the mechanical oscillation, where ω is the root of Eq. (1). As seen in Fig. 2b–c, this model predicts a similar trend for both Qm and Ωm as a function of glycerol concentration, which comes very close to the experimentally recorded trend. At high concentration (above 50%), the observed deviation in Ωm between model and measurement is attributed to the inability of the highly viscous liquid to penetrate uniformly beneath the disk (gap height 1 μm). This limitation could be avoided by increasing the height of the pedestal, which requires starting the fabrication from a thicker BOX layer, or by increasing the temperature to let the liquid penetrate this area, before bringing back the temperature at the initial room temperature value. It is worth noting that the sensitivity to the confined region beneath the disk can also offer an opportunity to explore surface tension effects in tight spaces33. At the same time, in contrast to Ωm, the evolution of Qm is well captured by our equations all over the explored range of concentration. Because the raw model of Eqs. (1), (2)) for mechanical oscillations does not fully reproduce the measured behavior at the highest glycerol concentration, we developed an algorithm to calibrate our model with data measured in air and in water (see the Supplementary information).

The waveguide is positioned 200 nm away from a silicon disk of radius 8 μm and thickness h = 220 nm that is immersed in a binary mixture of water/glycerol of varying concentration. The temperature is kept at 20 °C. a Measured power spectral density (PSD) around the 1st radial breathing mode (RBM). Measurements and raw model calculations for the RBM center frequency (b) and quality factor (c). d DC optical waveguide transmission spectra at low injected optical power. e DC optical transmission spectra at higher injected optical power into the waveguide (Pbus = 200 μW)

Let us now look at the DC optical intensity. By sweeping slowly the wavelength of the tunable laser at low power, the steady-state linear optical response of the device can be obtained. The spectrum calculated in the steady-state with Eq. (3) depends on the optical properties of the disk and its surrounding environment. The disk’s resonance wavelengths (λc) shift when changing the surrounding fluid, depending on the refractive index of the latter (n). The optical spectrum of the device exhibits many resonances, associated to distinct families of whispering gallery modes34 (see Fig. S1 of the Supplementary information). They have various penetration depth into the fluid, which can be used to extend the ability of our sensor to characterize surface adsorbed layers, like in plasmonic biosensing35,36. As seen in Fig. 2d, increasing glycerol concentration increases the refractive index of the liquid mixture and red-shifts a selected optical resonance. The shift in wavelength is linear in a range of more than 0.2 RIU, with a responsivity (S) of 45nm/RIU. The minimum detectable refractive index change attains 4 × 10−6RIU, using Δnmin = Δλmin × S, where Δλmin = ΔλFWHM × F37, with a measured optical line width of ΔλFWHM= 20 pm and F=1/100.

By running the same experiment with an increased laser power, we enter the non-linear regime for the optical response. Absorbed optical power within the resonator increases the temperature of the disk, which produces a red-shift of optical resonances, as a consequence of the thermo-optic effect. Solving Eqs. (3) and (4) at steady state requires finding roots of a polynomial, and a solution can be numerically approached in steps to find the optical response38. Figure 2e shows a typical response of the disk at higher power: the response exhibits a non-Lorentzian shape that is consistent with the optical transmission calculated from Eqs. (3) and (4) (see Supplementary information). The exact line shape depends on the thermal conductivity (λ) of the liquid, and an increase in thermal conductivity reduces its non Lorentzian nature.

Discussion

With these different measurements and models now implemented, the viscosity, density, compressibility, optical refractive index and thermal conductivity of the fluid are derived from the results of the RF and DC detection units. Extracted physical parameters for different water-glycerol solutions are shown in Fig. 3. In the viscosity data shown in Fig. 3a (inset), the accuracy is better than 2% for low (< 20%) concentration of glycerol in water. However, at higher concentration it is only of 30%. In Fig. 3b–d, we present the extracted density, sound velocity and compressibility (1/ρc2) of the liquid mixtures. The accuracy is about 10% for these parameters, and the resolution of the measurement is also of 10%. As illustrated in Fig. 3e–f, the measured refractive index and thermal conductivity show a high level of agreement with tabulated values, with accuracy better than 0.01% and 3%, respectively. At the same time, the resolution in the measurement of these two quantities is of 4 × 10−6 and 6 × 10−4. We observe that our optomechanical approach provides lower accuracy and resolution in the measurement of the mechanical properties of the liquid, as compared to its optical refractive index and thermal conductance. On top of the above-mentioned problem of un-proper filling by the most viscous liquids of the volume below the disk, our earlier research31 indicates that compressibility effects become significant at frequencies above 1 GHz, whereas within the operating frequency range of the device discussed here, compressibility accounts for only about 20% of the mechanical effect of the liquid onto the disk. This aspect negatively impacts the accuracy of our approach when it comes to determine the compressibility (and speed of sound) of the liquid. Employing a disk with a taller pedestal and smaller radius, hence even higher mechanical frequency, could enhance the accuracy of this specific measurement. Table 2 shows a comparison between the sensing results obtained with our approach and those obtained using other liquid sensing techniques. This comparison frames our findings within a broader context, illustrating the relative performances, advantages, and limitations of prior approaches. Our technique achieves accuracy levels comparable to prior techniques for each type of fluid measurement, but it is the only reported probe measuring all properties of interest of the fluid at the same time. This asset eliminates the need of multiple distinct technologies, and comes with an advantageous microscale footprint. The volume where the liquid properties are probed by the sensor sits in the picoliter range, but in the proof of principle experiments reported here, a much larger volume of liquid was actually dispensed. If precious liquids need to be saved, nano-dispensing methods will be required on top of our sensing technology.

a Viscosity, (b) density, (c) speed of sound, (d) compressibility, (e) refractive index, (f) thermal conductivity. A denser amount of points were taken in the analysis of the viscosity at small glycerol concentration, in order to gain better insight into the accuracy and resolution of our rheometer in this range. [A]43. [B]42. [C]44. [D]39,40. [E]41

As a last indicator of performance, we eventually investigate the minimum acquisition time of our disk sensor. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the RF detection unit utilized for measuring rheological properties is directly influenced by the optical power employed for the optomechanical measurement and by the integration time of the RF signal. In Fig. 4, the viscosity deduced from the analysis of mechanical frequency shift and quality factor is plotted against the optical power traveling in the bus waveguide and against the sweep time of the RF electronic spectrum analyser. The evolution of the spread of data in both panels of Fig. 4 indicates that a higher optical power and a longer integration time lead to better precision in viscosity determination. The viscosity determination can reach a precision better than 1%, which is for example good enough to distinguish pure water from saline water. Conversely, rapid measurements with a sweep time of 210 μs result in a unity uncertainty in the determined value. This underscores the importance of trade-off between acquisition speed and measurement accuracy28. Our minimum measurement time is dictated by our electronic spectrum analyzer, and can be further reduced with a high-speed and low noise oscilloscope. Our current shortest measurement time (70 μs) comes close to the record value for viscosity measurement (20 μs)28, with an accuracy that is, however, twice better. Such acquisition times of few tens of microseconds are orders of magnitude shorter than those of conventional rheometry systems. For higher optical power, the error bars of our viscosity sensing platform diminish significantly. The detection error decreases from 10% at 50 μW power to below 4% above 300 μW. Balancing the injected optical power level is crucial for accurate and reliable measurements of rheological properties of the liquid, while minimizing perturbation of the liquid temperature.

Conclusion

Our study presents an optomechanical method for the measurement of rheological, optical and thermal properties of liquids on the micron scale. By using a small suspended silicon disk as a passive probe, we achieve accurate measurements, while adding minimal disturbance to the investigated liquid. In particular, the use of a working power of 50 μW, leading to a temperature change of less than 0. 3 ∘C, preserves thermal equilibrium during measurements. By employing optomechanical transduction, we access to a wide range of fluid properties with a single microscale device, including viscosity, density, compressibility (hence speed of sound), optical refractive index and thermal conductivity. With a reported fast acquisition time down to 70 μs, these properties can all be tracked with high time resolution. This opens applicability of the method to multiple scientific domains encompassing thermodynamical transitions in liquid, wetting phenomena, and in situ monitoring of biomolecule solutions. Lastly, because the presented optomechanical sensor borrows to Photonic Integrated Circuits (PIC) and MEMS technologies, it leans itself to integration and portability, eventually making the approach adoptable by non-specialist end-users.

References

Puneeth, S., Kulkarni, M. B. & Goel, S. Microfluidic viscometers for biochemical and biomedical applications: a review. Eng. Res. Express 3, 022003 (2021).

Del Giudice, F. A review of microfluidic devices for rheological characterisation. Micromachines 13, 167 (2022).

Gu, Q. et al. Simultaneous nanorheometry and nanothermometry using intracellular diamond quantum sensors. ACS Nano 17, 20034–20042 (2023).

Salipante, P. F. Microfluidic techniques for mechanical measurements of biological samples. Biophys. Rev. 4, 011303 (2023).

Singh, P., Sharma, K., Puchades, I. & Agarwal, P. B. A comprehensive review on MEMS-based viscometers. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 338, 113456 (2022).

Toropov, N. et al. Review of biosensing with whispering-gallery mode lasers. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 42 (2021).

Souza, R. R. et al. A review of the advances and challenges in measuring the thermal conductivity of nanofluids. Nanomaterials 12, 2526 (2022).

Zhou, J. & Papautsky, I. Viscoelastic microfluidics: progress and challenges. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 6, 113 (2020).

Waigh, T. A. Advances in the microrheology of complex fluids. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 074601 (2016).

Mao, Y., Nielsen, P. & Ali, J. Passive and active microrheology for biomedical systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 916354 (2022).

Persson, L. B., Ambati, V. S. & Brandman, O. Cellular control of viscosity counters changes in temperature and energy availability. Cell 183, 1572–1585 (2020).

Budin, I. et al. Viscous control of cellular respiration by membrane lipid composition. Science 362, 1186–1189 (2018).

Trejo-Soto, C., Lázaro, G. R., Pagonabarraga, I. & Hernández-Machado, A. Microfluidics approach to the mechanical properties of red blood cell membrane and their effect on blood rheology. Membranes 12, 217 (2022).

Hou, X. et al. Interplay between materials and microfluidics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–15 (2017).

Liu, Y. & Jiang, X. Why microfluidics? merits and trends in chemical synthesis. Lab Chip 17, 3960–3978 (2017).

Robin, P. et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 379, 161–167 (2023).

Xiong, T. et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 379, 156–161 (2023).

Choi, S. & Park, J.-K. Microfluidic rheometer for characterization of protein unfolding and aggregation in microflows. Small 6, 1306–1310 (2010).

Sbarra, S., Waquier, L., Suffit, S., Lemaître, A & Favero, I. Optomechanical measurement of single nanodroplet evaporation with millisecond time-resolution. Nat. Commun. 13, 6462 (2022).

Jimenez, R. M. et al. A microfluidic strategy for accessing the thermal conductivity of liquids at different temperatures. Microchem. J. 193, 109030 (2023).

Payam, A. F., Trewby, W. & Voïtchovsky, K. Simultaneous viscosity and density measurement of small volumes of liquids using a vibrating microcantilever. Analyst 142, 1492–1498 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Piezoelectric-aln resonators at two-dimensional flexural modes for the density and viscosity decoupled determination of liquids. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 38 (2022).

Tiwari, S., Dangi, A. & Pratap, R. A tip-coupled, two-cantilever, non-resonant microsystem for direct measurement of liquid viscosity. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 34 (2023).

Toledo, J., Ruiz-Díez, V., Velasco, J., Hernando-García, J. & Sánchez-Rojas, J. L. 3d-printed liquid cell resonator with piezoelectric actuation for in-line density-viscosity measurements. Sensors 21, 7654 (2021).

Khan, M. et al. Online measurement of mass density and viscosity of pl fluid samples with suspended microchannel resonator. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 185, 456–461 (2013).

Oliva, P., Bircher, B. A., Schoenenberger, C.-A. & Braun, T. Array based real-time measurement of fluid viscosities and mass-densities to monitor biological filament formation. Lab Chip 19, 1305–1314 (2019).

Ledesma, E., Zamora, I., Yanez, J., Uranga, A. & Barniol, N. Single-cell system using monolithic PMUTS-on-CMOS to monitor fluid hydrodynamic properties. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 76 (2022).

Madsen, L. S. et al. Ultrafast viscosity measurement with ballistic optical tweezers. Nat. Photonics 15, 386–392 (2021).

Neshasteh, H. et al. Optomechanical micro-rheology of complex fluids at ultra-high frequency. Nat. Commun. 16, 407 (2025).

Gil-Santos, E. et al. High-frequency nano-optomechanical disk resonators in liquids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 810–816 (2015).

Neshasteh, H., Ravaro, M. & Favero, I. Fluid–structure model for disks vibrating at ultra-high frequency in a compressible viscous fluid. Phys. Fluids 35, 052008 (2023).

Sbarra, S., Allain, P. E., Suffit, S., Lemaître, A. & Favero, I. A multiphysics model for ultra-high frequency optomechanical resonators optically actuated and detected in the oscillating mode. APL Photonics 6, 8 (2021).

You, I., Yun, N. & Lee, H. Surface-tension-confined microfluidics and their applications. ChemPhysChem 14, 471–481 (2013).

Parrain, D. et al. Origin of optical losses in gallium arsenide disk whispering gallery resonators. Opt. Express 23, 19656–19672 (2015).

Neshasteh, H., Mataji-Kojouri, A., Akbarzadeh-Jahromi, S.-A. & Shahabadi, M. A hybrid photonic-plasmonic sensing platform for differentiating background and surface interactions using an array of metal-insulator-metal resonators. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 1621–1627 (2015).

Mataji-Kojouri, A., Ozen, M. O., Shahabadi, M., Inci, F. & Demirci, U. Entangled nanoplasmonic cavities for estimating thickness of surface-adsorbed layers. ACS Nano 14, 8518–8527 (2020).

Vollmer, F. & Yang, L. Review label-free detection with high-q microcavities: a review of biosensing mechanisms for integrated devices. Nanophotonics 1, 267–291 (2012).

Guha, B. et al. High frequency optomechanical disk resonators in III–V ternary semiconductors. Opt. Express 25, 24639–24649 (2017).

Hale, G. M. & Querry, M. R. Optical constants of water in the 200-nm to 200-μm wavelength region. Appl. Opt. 12, 555–563 (1973).

Physical properties of glycerine and its solutions (Glycerine Producers’ Association, 1963).

Bates, O. K. Binary mixtures of water and glycerol-thermal conductivity of liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. 28, 494–498 (1936).

Volk, A. & Kähler, C. J. Density model for aqueous glycerol solutions. Exp. Fluids 59, 75 (2018).

Cheng, N.-S. Formula for the viscosity of a glycerol- water mixture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47, 3285–3288 (2008).

Slie, W., Donfor Jr, A. & Litovitz, T. Ultrasonic shear and longitudinal measurements in aqueous glycerol. J. Chem. Phys. 44, 3712–3718 (1966).

Schmidt, A., Chiesa, M., Chen, X. & Chen, G. An optical pump-probe technique for measuring the thermal conductivity of liquids. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 064902 (2008).

Lazaro, R. C., Marques, C., Castellani, C. E. & Leal-Junior, A. Fbg-based measurement systems for density, specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity assessment for liquids. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 7657–7664 (2021).

Ferreira, R., Bilro, L., Marques, C., Oliveira, R. & Nogueira, R. Refractive index and viscosity: dual sensing with plastic fibre gratings. In 23rd International Conference on Optical Fibre Sensors, Vol. 9157, 1297–1300 (SPIE, 2014).

Pevec, S. & Donlagic, D. Multiparameter fiber-optic sensor for simultaneous measurement of thermal conductivity, pressure, refractive index, and temperature. IEEE Photonics J. 9, 1–14 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council through the ERC NOMLI project (770933).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neshasteh, H., Mataji-Kojouri, A., Le Fur, C. et al. Multiphysics optomechanical sensing of a liquid on the micron scale. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01095-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01095-y