Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) cell culture systems better simulate the in vivo microenvironment by promoting intercellular interactions and functional expression, which are crucial for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. However, conventional two-dimensional (2D) culture platforms fail to mimic the spatial complexity of in vivo tissues, often resulting in altered cellular behavior and limited physiological relevance. In this research, we introduce a 3D cell culture platform based on a digital microfluidic (DMF) system. This platform integrates DMF electrode actuation with 3D-printed microstructure arrays, enabling precise capture and aggregation of cells within a defined 3D scaffold. While cells initially adhere in a 2D structure, they rapidly self-assemble into a 3D cell spheroid on the chip. The platform’s capabilities for droplet dispersion, fusion, and movement were validated using the 3D-printed DMF chip. The key parameters, such as applied voltage, microstructure height, and electrode spacing, were systematically investigated for their effects on droplet manipulation. Cell viability and proliferation assays in 24, 48, and 72 hours confirmed that the 3D microstructured scaffolds exhibit excellent biocompatibility and provide a microenvironment favorable for in vivo-like cell growth. Overall, this integrated DMF chip supports robust 3D cell growth and represents a versatile tool for applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Functional devices with 3D micro-nano structures have significant applications in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS)1, biomedical engineering2, tissue engineering3, new energy batteries4, microfluidic devices5, and flexible electronics6. In particular, 3D micro-nano structures are widely used to replicate the intricate architectures of tissues and organs, such as 3D cell culture scaffolds7. A 3D microstructured scaffold provides a supportive framework for microtissue cells, playing a crucial role in cell differentiation and proliferation8. The assembly of multilayer 3D cell structures relies on scaffolds to maintain spatial organization. An ideal microstructured scaffold supports the spatial distribution of cells within a three-dimensional (3D) architecture, offers mechanical stability, and facilitates efficient nutrient exchange and metabolic waste removal. Consequently, the development of 3Dmicrostructures cell culture scaffolds that closely simulate the in vivo cellular microenvironment has gained increasing research interest.

Microfluidic systems offer significant advantages in cell culture, including precise control, low reagent consumption, biomimetic environments, and automation, making them a promising alternative to conventional methods9. The small fluid volumes and unique physical properties at the microscale enable spatial control and gradient formation, facilitating the creation of 3D biomimetic microenvironments that mimic key physiological parameters such as extracellular matrix composition, flow rates, chemical gradients, pH, and temperature10,11. Unlike traditional cell culture methods, microfluidic-based cell culture provides continuous nutrient supply, efficient waste removal, automated liquid handling, and high-throughput capabilities12. As a result, microfluidic chips are increasingly being adopted as versatile platforms for advanced cell culture applications. For instance, María developed a microfluidic device with a central microchamber and two lateral microchannels, embedding cells in a 3D matrix gel for 3D cell culture to construct a tumor microenvironment13. Similarly, Jang et al. integrated microfluidics with 3D cell culture and bioassays, using continuous perfusion microfluidic channels to cultivate MC3T3-E1 cells for drug screening applications14. Microfluidic systems based on continuous sample infusion effectively simulate a dynamic in vivo microenvironment, with external pumps controlling fluid flow and nutrient input. This approach minimizes sample volume requirements and reduces reagent consumption. However, for scarce or expensive sample solutions, continuous sample infusion can lead to high operational costs. In contrast to channel-based microfluidics, digital microfluidics employs electrical forces to manipulate individual droplets, enabling precise and flexible control of cellular microenvironments15. By regulating droplet movement, DMF can fine-tune conditions for cell growth, including nutrient concentration, temperature, and chemical gradients16. For example, Fan et al. successfully achieved precise stem cell separation and culture using DMF chips17. By leveraging electrically driven droplet manipulation technology, cell distribution and growth conditions can be precisely controlled at the microscale, enabling the simulation of a more physiologically relevant in vivo microenvironment. Shang et al. developed a DMF chip to simulate the growth environment of tumor cells, offering precise control of nutrient and drug delivery while enabling real-time monitoring of cellular metabolic activities18. Despite these advantages, DMF technology faces a critical limitation: the lack of on-chip 3D structures, which restricts its application in 3D cell culture. Addressing this challenge requires the integration of DMF technology with 3D microstructured scaffolds to create a more physiologically relevant cellular microenvironment.

In recent years, research efforts have been made to integrate additive manufacturing with digital microfluidics to introduce 3D functionalities. For instance, Zhai et al.19 developed a DMF system incorporating 3D microstructures for single-cell culture, while Su et al.5 systematically reviewed recent advances in 3D-printed microfluidics, highlighting applications in constructing complex 3D fluidic channels. However, most of these studies have focused primarily on fabricating macroscopic fluidic channels or require multi-step processing approaches. To overcome the limitations of conventional fabrication methods in terms of structural complexity and manufacturing efficiency, there is a pressing need to develop a novel strategy capable of fabricating functional 3D microarchitectures in a single step, thereby enabling seamless integration of 3D cell culture scaffolds with droplet-based actuation.

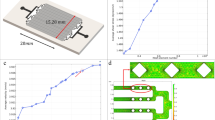

Herein, we present a digital microfluidic system for 3D spheroid culture, integrating micro-nano 3D printing technology to fabricate a 3D microstructure array on-chip. In contrast to existing DMF systems that often require multi-mask photolithography and sequential assembly for 3D structure integration, our approach enables single-step fabrication of a unified dielectric-fence-microstructure scaffold directly on electrode substrates. This not only eliminates the need for cleanroom facilities and complex alignment but also allows for customizable 3D microenvironments conducive to cell spheroid formation. Our platform thus represents a significant simplification and enhancement over current DMF-based 3D culture systems. Briefly, we developed an integrated 3D structure comprising a dielectric layer, fence, and microstructures using a single-step fabrication process on a substrate with chromium electrodes (Fig. 1a). Compared to traditional stereolithography techniques, this approach eliminates the complexities associated with multi-step operations, high costs, and low fabrication tolerances. To facilitate system control, we designed an electronic control system incorporating a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) and printed circuit board (PCB) for data transmission, signal generation, and individual electrode charging (Fig. 1b). The DMF system employes a sandwich structure, where the bottom plate, embedded with an electrode array, connects to the electronic control system and applies high- and low-voltage sine wave signals. The top plate is grounded, maintaining the sample droplets between the two plates. By loading cell suspension droplets at the inlet, we direct them to designated culture positions through electrode actuation (Fig. 1c). To validate the feasibility of the 3D-printed DMF chip for cell culture, we use MCF-7 cells as templates and successfully cultivate 3D cell spheroids on the chip and compared them with those grown on 2D plate structures, demonstrating the effectiveness of the 3D microstructures for spheroid culture (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, 3D printed structural material shows good biocompatibility for cells. With its one-step fabrication capability, robust droplet control, and efficient 3D spheroid generation, the developed DMF system holds significant potential for applications in drug screening, tissue engineering, organ-on-a-chip models, and other biological research fields.

Results and discussion

3D Microstructure fabrication on DMF chips

Conventional digital microfluidic chips are fabricated by integrating actuation electrodes and interconnecting wires onto a PCB or glass substrate. A layer of SU8 is then deposited on the electrodes using stereolithography to serve as the dielectric layer, followed by a Teflon layer on top of the SU8 to impart hydrophobicity and facilitate smooth droplet movement. These processes require cleanroom conditions and involve multiple fabrication steps, where failure in any single step can compromise subsequent procedures. In this study, we replace traditional stereolithography with projection stereolithography 3D printing, enabling the one-step fabrication of the dielectric layer, fence structure, and 3D microstructures directly on a chromium plate to form the DMF chip (Fig. 2a). This approach eliminates the need for complex procedures and skilled operations, as 3D printing allows direct fabrication of imported 3D structural models from a computer (Fig. 2b). The fabricated dielectric layer has a thickness of 15 μm while the dimensions of the fence structure are 10 × 10 × 20 μm. The cell culture chamber, formed by two layers of scaffolds, has (Fig. 2c) dimensions of 80 × 80 × 100 μm, with a scaffold cross-section of 20 × 20 μm. Adjacent culture chambers are interconnected, allowing for the exchange of cell culture media, oxygen, nutrients, and other essential substances. According to the above design, the developed 3D microstructure on the chip was shown in Fig. 2d. Then, more details of the chip were observed using SEM technology. As shown in Fig. 2e, f, the microstructures produced via 3D printing possess excellent surface quality and high resolution, confirming the suitability of 3D printing for fabricating complex microstructures.

a Photograph of the digital microfluidic chip. b Diagram illustrating the integrated dielectric layer thickness, fence structure, and 3D microstructures. c Dimensions of the 3D microstructures. d 3D microstructures on the chip. e SEM image of the 3D microstructures. f SEM image of the 3D microstructures at higher magnification

Droplet motion on DMF chip

DMF technology operates based on electrowetting-on-dielectric (EWOD)20. When an electric field is applied, the wettability of a droplet changes due to voltage variation between insulating substrates, altering its contact angle (Fig. 3a, b). The magnitude of the contact angle of on-chip droplets influences the droplets' deformation and movement. Experimental results show that the 3D printing materials used in this study are hydrophilic, whereas the fabricated microstructures exhibit hydrophobic properties. The measured contact angle is comparable to that of Teflon-coated glass (Fig. 1s, supporting materials). To enhance hydrophobicity, the 3D-printed surface is coated with Teflon. This treatment significantly increases the contact angle to 119.8° for planar structures and 131.5° for 3D microstructures, approaching superhydrophobic characteristics (Fig. 3c). Under an applied electric field, charge accumulation between the droplet and the dielectric layer creates a capacitive effect. This alters surface energy, modifies surface tension, and changes the contact angle. These interactions enable precise manipulation of discrete droplets, supporting fundamental DMF operations such as droplet transportation and splitting. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, a schematic representation of droplet transportation, splitting, and spreading over 3D microstructures on the chip is presented. Figure 3e–g depicts the dynamic changes of a droplet under an electric field. Initially, the droplets remain spherical. Upon voltage application, the contact angle of the droplet changes, propelling the droplet along the direction of the electric field lines (Video 1is-3s, supporting materials).

a Principle of electrowetting. b Droplet control under the influence of an electric field. c Contact angles of Teflon-modified 2D planar structures and 3D structures. d Schematic diagram illustrating droplet movement, splitting, and spreading over 3D microstructures. e–g Time-lapse images of droplet movement, splitting, and the dynamics of 3D microstructures on the chip (applied voltage: ~157 V, frequency: 2 kHz). Scale bar: 200 μm

According to the Yong–Lippmann equation21, the dielectric constant and thickness of the dielectric layer directly influence the driving force in DMF. The SU8 dielectric layer commonly used in conventional DMF chips has a dielectric constant of 3.122, while photosensitive resins typically range between 2.7 and 323. A higher dielectric constant improves resistance to breakdown, whereas an excessively thin dielectric layer increases the risk of failure. Considering the constraints of the 3D printing process, we selected a dielectric layer thickness of 20 μm to balance durability and performance. Additionally, the operational stability of the 3D-printed dielectric layer was also evaluated. When a 300 V driving voltage was applied for 500 ms to move a droplet, the dielectric layer remained intact. However, after applying a driving voltage of 220 V continuously for 20 minutes, the layer degraded, resulting in the electrode exposure and electrolysis (Video 4s, supporting materials). Therefore, to ensure reliable droplet movement and prevent material breakdown, the applied voltage should remain below 220 V whenever possible. This precaution not only protects the 3D printed dielectric layer but also safeguards cells moving on the electrode from potential damage.

Precise droplet manipulation on the chip

Precise droplet manipulation on the chip is essential for rapid droplet generation, efficient reactions, and reduced processing time. To evaluate chip performance, we compared droplet movement on three types of dielectric layers: SU8 material, photosensitive resin, and 3D microstructures. First, we examined how the height of the 3D microstructures affects the required voltage (Fig. 4a). The distance between the upper and lower plates directly influences the voltage needed for droplet movement. A smaller ratio of the distance between the plates to the height of the microstructure necessitates a higher applied voltage to move the droplet onto the microstructure. As shown in Fig. 4b, for a constant sample volume, the applied voltage required for droplet movement reaches 200 V at a height ratio is 3:1, while it decreases to 157 V at a ratio of 5:1. However, a higher ratio also affects droplet movement speed, which must be matched with the electrode dimensions and droplet size. Figure 4c illustrates the relationship between applied voltage and droplet speed for a fixed droplet volume. Droplet speed increases linearly with voltage. However, droplets move more slowly when transitioning from a planar surface to a microstructure than when moving on a planar surface. We also assessed the minimum voltage required for droplet movement across the three dielectric layers. The SU8 dielectric layer had the lowest threshold, with droplets responding at 25 V and moving smoothly at 46 V. In contrast, microstructures increased the voltage requirement, with droplets requiring 200 V to move on 3D microstructures with a 3:1 height ratio. Next, we evaluated droplet transport efficiency on different surfaces at 157 V (Fig. 4e). The round-trip times for droplets on the SU8 and 3D-printed planar structure were similar. However, transport times were longer on 3D microstructures. Notably, droplets took more time to move from the planar surface to the 3D microstructure than to return, which may be attributed to the resistance encountered by the droplets during their movement, which affects their response24.

a The ratio of the height of the microstructure to the height of the electrode (D/H). b The relationship between D/H and the applied voltage. c The relationship between the applied voltage and the movement speed. d The voltage range for droplet movement in SU8, 2D, and 3D structures. e The round-trip time of droplets moving in SU8, 2D, and 3D structures (Applied voltage:157 V). f The applied voltage for droplet and cell suspension movement in SU8, 2D, and 3D structures. g Deposition of cell suspensions (2 × 104 cells/mL) in 3D microstructures. h Fluorescence image of cells stained with Calcein AM (green, live) and PI (red, dead) within 3D microstructures (×20 objective). i SEM images of cells within 3D microstructures

During cell culture, droplets containing suspended cells are exposed to air to support respiration. While transport time is short, strong electric fields may still affect cell response and growth on the chip. We then mix F127 and cell suspension solution, which can reduce the movement voltage from 200 V to 160 V (Fig. 4f). This reduction is likely attributed to the surfactant properties of Pluronic F127, which can adsorb at the liquid–solid interface and reduce the interfacial tension. A lower interfacial tension facilitates a greater change in the contact angle for a given electrowetting voltage, according to the principles of EWOD25. Consequently, a lower applied voltage is sufficient to achieve the necessary contact angle change for droplet actuation. Further improvements were achieved by filling the electrode gap with silicone oil (1 µL), which facilitates smoother cell suspension movement on the DMF chip. Figure 4g presents an optical image demonstrating successful transport of the cell suspension (2 × 104 cells/mL) into 3D microwell structures from the planar structure (Fig. 3s, Video 5s in the supporting materials). To verify the precise distribution and attachment status of the cells within the 3D microstructures, fluorescence imaging confirmed that most cells were successfully localized within the microstructures (Fig. 4h), highlighting their efficient capture capabilities. Additionally, SEM images provide a detailed visualization of cell morphology and distribution within the 3D micro-wells (Fig. 4i).

Biocompatibility testing of 3D printed microstructures

After systematic studies, electrodes were utilized on the DMF chip to drive cell suspension solutions into 3D microstructures. The CCK-8 assay results (from three independent experiments, n = 3) showed the mean relative growth rate (RGR) and cytotoxicity levels of the 3D-printed microstructure scaffolds26 (Table 1s, supporting materials). The mean RGR values at 1 day, 2 days, and 3 days of culture were 87%, 93%, and 88%, respectively, with a consistent cytotoxicity level of grade 1 across all time points (p < 0.05 compared to control, one-way analysis of variance among groups (ANOVA), n = 3). These results indicate that the leachates from the 3D-printed microstructures exhibit no significant cytotoxicity.

To prevent interference from the intrinsic fluorescence of the 3D-printed materials, the microstructures were treated using an alcohol immersion method (Fig. 5a). Fluorescence intensity measurements at various wavelengths were compared across three different 3D printing materials, revealing that MED resin exhibited minimal fluorescence interference. Fluorescent imaging confirmed that the intrinsic fluorescence of the MED resin did not affect cell visualization (Fig. 5b). Figure 5c illustrates the changes in cell activity within the 3D microstructure scaffolds relative to the control group at the 24, 48, and 72 h time points. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in cell proliferation between the 3D structures and the control group at 24, 48, and 72 h (p < 0.05). It should be noted that the cell proliferation activity in the 3D structures remained above 85% at all time points assessed (specifically, 87% at 24 h, 93% at 48 h, and 88% at 72 h). These results clearly indicate that the 3D-printed microstructural scaffolds exhibit favorable biocompatibility without inducing significant toxic inhibition of cell growth. Notably, although slight reductions in activity relative to the control were observed at 24 and 72 h, the biological implications of these differences are limited, as cell viability consistently remained at high levels. In particular, at the 48 h time point, cell proliferation reached 93% in the 3D constructs, indicating that the cells adapted well to the 3D microenvironment and maintained a healthy proliferative state.

a Fluorescence images of three printed materials at varying wavelengths. b Fluorescence intensity of three printed materials across different wavelengths. c Proliferative activity of cells after 24, 48, and 72 h of culture. d Optical density (OD) values of cells cultured for 24, 48, and 72 h in 2D and 3D microstructures. Values are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3), Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 for comparisons between 2D/3D structures and the Control group at the same time point; ####p < 0.0001, ###p < 0.001 for comparisons between 2D/3D structures and the Control group at the different time point. e Fluorescence microscopy images of cells cultured in 3D-printed microstructures after 24, 48, and 72 h (Green: calcein AM labeled live cells; Red: PI marked dead cells). Cell concentration: 2 × 104 cells/mL; Scale bar: 100 μm

MTT assays further assessed cell proliferation on the scaffolds. As shown in Fig. 5d, cell density on the 2D planar surface was relatively low at 24 h. Cell density increased at 48 and 72 h, but the growth rate was significantly slower than in the 3D microstructures. To quantitatively assess the differences in cell proliferation, statistical analysis of the OD values was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. At 24 h, the OD value of the 2D structure was significantly lower than that of the Control group and the 3D structure. This trend continued at 48 h, with the 2D structure showing significantly reduced proliferation compared to both the Control and the 3D structure. By 72 h, the OD value for the 3D structure was significantly higher than that of the 2D structure and began to show a significant difference from the Control group, indicating robust late-stage proliferation. Additionally, a significant increase in cell density from 24 to 72 h was observed across all groups, confirming active proliferation over time. These statistical results unequivocally demonstrate that the 3D microstructured scaffolds provide a significantly more favorable environment for cell proliferation than the 2D planar surfaces. Fluorescence microscopy images of live cells cultured within the 3D microstructures at 24, 48, and 72 h are shown in Fig. 5e. Over time, the number of cells increased, and their morphology became more complex. PI (red) and Calcein AM (green) staining were used to label dead and live cells, respectively. The merged images illustrate the overlay of these markers, confirming the viability of cells in the 3D scaffolds. These findings demonstrate that 3D-printed microstructure scaffolds exhibit high biocompatibility, effectively support cell adhesion, and promote proliferation.

3D culture of cell spheroids on a chip

In a 2D cell culture system, cells grow on flat (typically plastic) culture dishes, where they adhere and spread within the dish. This method is cost-effective and easy to implement, making it widely used for studying cell behavior. However, its simplicity limits its ability to replicate the complex in vivo environment. Key biological processes such as cell signaling, chemical gradients, and 3D architecture are not accurately represented27. As a result, data obtained from 2D cultures may not reliably predict cellular behavior in vivo, leading to misleading or inconsistent outcomes28.

In digital microfluidic chips, cell adhesion and growth are not feasible in an oil-filled environment. The oil layer covering the hydrophobic surface prevents cell attachment. Figure 6a shows the morphology of cells immediately after seeding onto a 2D planar structure. Initially, the cells appear spherical and remain dispersed without forming connections. After 24 h, some cells begin to aggregate, eventually forming a monolayer. Figure 6b presents the behavior of cells cultured on 3D-printed microstructures over one and two days. At seeding, cells are evenly distributed in a spherical shape at the bottom of the microstructures. As time progresses, the distance between cells decreases, and they begin clustering toward the center. After 48 h, distinct cell aggregates form. Notably, the self-assembly of cells into spheroids within the 3D microstructures is primarily driven by cell–cell adhesion mechanisms and the physical confinement provided by the micro-wells29. The Teflon-coated hydrophobic surface minimizes cell-substrate adhesion, promoting cell–cell interactions and aggregation. Furthermore, the geometric constraints of the micro-wells facilitate the gathering of cells toward the center under gravity and mild fluidic forces, thereby accelerating spheroid formation30,31. With extended culture, these aggregates become denser as cells continue to cluster. Unlike the monolayer structure in 2D cultures, cells on 3D-printed scaffolds form multilayered spheroids, resembling in vivo tissue structures. Due to the presence of a siloxane film on the chip, cells in both 2D and 3D culture systems are unable to directly adhere to the microstructures32. Instead, they aggregate over time, forming spheroidal clusters. In addition, SEM images further illustrate the structural differences between 2D and 3D cell cultures. After 48 h on a 2D planar surface, cells remain dispersed and form a spherical monolayer. In contrast, cells in the 3D microstructures develop compact spheroids with stronger intercellular connections. The 3D scaffold provides structural support, making cells more responsive to morphological and physiological changes33,34.

Cell viability was assessed using live/dead staining after two days of culture. Live cells exhibited green fluorescence, while dead cells showed red fluorescence (Fig. 6c, d). Viability was significantly lower in the 2D system compared to the 3D microstructures, as the oil layer inhibited adhesion and growth, reducing overall cell activity. In contrast, cells in the 3D microstructures maintained higher viability. Most cells stained green, with only a small number appearing red. Dead cells were mainly concentrated in the center of cell aggregates, likely due to limited nutrient and oxygen availability, which reduced viability in these regions. These findings confirm that 3D-printed microstructures serve as effective scaffolds for cell growth. They exhibit good biocompatibility and have the potential to influence gene expression while enhancing intercellular communication35.

Conclusions

This work presents a 3D cell culture platform based on a digital microfluidic system. Utilizing micro-nano 3D printing technology, a dielectric layer-fence-array 3D microstructure was fabricated in a one-step process on a chromium electrode substrate. The platform demonstrated precise droplet manipulation and supported the formation of 3D cell spheroids, showing good biocompatibility and a favorable microenvironment for cell growth over 72 h. However, the current platform requires relatively high actuation voltages and may benefit from further optimization of material properties and microstructure design to enhance long-term culture stability and scalability. Future work will focus on integrating sensing capabilities, reducing operational voltage, and exploring more complex multi-culture models to better mimic in vivo conditions. The developed DMF chip holds significant potential for applications in drug screening, tissue engineering, and organ-on-a-chip research.

Materials and methods

Isopropyl alcohol (IPA), acetone and ethanol were purchased from Millipore. Pluronic F127 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, ON, USA). Silicone oil (1 cSt) was purchased from Clearco, USA. A549 and MCF-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). DMEM Medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin-EDTA and phosphate buffer solution (PBS) were purchased from Gibco. The CCK-8 assay kit and the live/dead cell staining kit were purchased from Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd.

3D printed DMF chip fabrication

The DMF chip consists of three components: a bottom glass plate patterned with chromium electrodes, a 3D printed layer, and a top glass plate coated with a layer of indium tin oxide. The on-chip electrode array was designed using CAD and patterned on the glass substrate to serve as the base. The 3D printed layer was fabricated on the bottom substrate using a high-precision 3D printer (nanoArch S130, BMF Precision, China). The photocurable resin used was MED resin (BMF Precision), which has a dielectric constant of approximately 2.8 and an initial contact angle of ~about 70° before Teflon coating. This layer comprises a thin layer-fence-3D microstructure array, with the fabrication process as follows: a 10-micron-thick dielectric layer was printed on the bottom substrate; the fence and 3D microstructure array were printed in a sequential manner, requiring precise alignment with the underlying electrodes on the dielectric layer. These structures function as a fence (patterned structure of 10 × 20 microns) to prevent droplet drift and as a microstructure array for 3D cell culture. The 3D printed layer and the top plate were coated with Teflon-AF (polytetrafluoroethylene) to create a hydrophobic layer, facilitating smooth droplet transport on the chip. Specifically, a 1% (w/v) solution of Teflon-AF was spin-coated at 3000 rpm for 30 seconds to achieve a uniform thin film with an approximate thickness of 50 nm, followed by baking at 80 °C for 10 minutes to cure the coating. The two plates were assembled face-to-face, with a layer of conductive adhesive tape of specific thickness serving as a spacer between the two plates.

DMF chip testing setup

The DMF system comprises four components: a DMF chip, a circuit control board, custom droplet control software, and a fluorescence microscope. The DMF chip is secured by a 3D printed support and a test rack. The PCB circuit board connects to the exposed electrodes on the chip via contact pads. The on/off control of the driving signals is managed by physical relays (HRS2H-SDC5V) on the PCB. A custom control program is employed to ascertain the position of the droplets and to automatically execute droplet operations (such as movement, merging, and splitting) by controlling the power switch. A signal generator is utilized to produce an alternating driving signal (0.5–10 Vrms, 2 kHz, sine wave), which is amplified and input to the electrodes. Brightfield and fluorescence imaging of the DMF chip is performed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, USA).

Preparation of 3D printed microstructure scaffold extraction solution

The 3D printed planar structures and the 3D microstructural scaffolds were sterilized by immersion in alcohol and subsequently exposed to ultraviolet light overnight in a sterile laminar flow hood. Following sterilization, both types of scaffolds were placed in RPMI-1640 culture medium (10% FBS, 1% antibiotics) within the laminar flow hood and incubated statically in a carbon dioxide-controlled incubator for 72 hours. After incubation, the culture medium was aspirated into centrifuge tubes and stored at 4 °C for later use. The volume of the leachate was added to the culture medium according to the national standard (GB/T 16886.11-1997), which specifies a surface area to extraction medium ratio of 3 cm²/mL.

Cell culture

The experiments utilized two types of cells: A549 cells for cytotoxicity and proliferation assays, and MCF-7 cells for both 2D and 3D spheroid cultures. These cells were maintained in DMEM growth medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen Canada, Burlington, ON), along with penicillin (100 IU/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and were cultured in a humidified incubator at 5% CO₂ and 37 °C. A549 and MCF-7 cells were passaged every 2–3 days at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells/mm². Prior to experimentation, the cells were cultured in standard polystyrene cell culture flasks until they reached confluence, at which point they were released using a 0.025% trypsin/EDTA solution. The cell suspension was centrifuged, and the cell pellet was washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then resuspended in fresh growth medium at an appropriate density. Cell counts and viability were quantified using a cell counter and a live/dead cell staining reagent (Invitrogen Canada).

Cell toxicity experiment

A549 cells in the logarithmic growth phase were digested with trypsin to prepare a single-cell suspension, which was then adjusted to a concentration of 2 × 10⁴ cells/mL. A volume of 100 μL of the cell suspension was transferred to each well of a 96-well plate. After incubating in a cell incubator for 4 hours to allow cell adhesion, the culture medium was replaced. The experiment was divided into three groups: Experimental Group 1 (leachate from 3D printed planar scaffolds), Experimental Group 2 (leachate from 3D printed microstructured scaffolds), and the Control Group (plain culture medium). Each group was set up with six technical replicates per independent experiment, and the entire experiment was repeated three times independently (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. After culturing the cells for 1, 2, and 3 days, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well under a laminar flow hood. The plate was then returned to the cell incubator and incubated in the dark for 2 h. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader. The RGR was calculated as follows: RGR = 100% × (mean absorbance of the experimental group/mean absorbance of the control group). The RGR of the experimental groups was rated according to the national standard (GB/T 16886.5-2003) as follows: Grade 0: RGR > 100%; Grade 1: 80% < RGR < 99%; Grade 2: 50% < RGR < 79%; Grade 3: 30% < RGR < 49%; Grade 4: 0% < RGR < 29%. Grades 0 and 1 indicate that the material leachate exhibits no cytotoxicity.

Cell proliferation experiment

The 3D printed planar and microstructured scaffolds were sterilized by immersion in alcohol, followed by overnight exposure to UV light in a laminar flow hood. The scaffolds were then retrieved and placed into a 96-well plate, with the blank group consisting of plain culture medium. A549 cells, cultured until over 80% confluence in a culture flask, were digested with trypsin to prepare a single-cell suspension and adjusted to a concentration of 2 × 10⁴ cells/mL. A volume of 200 μL of this cell suspension was added to each well of the 96-well plate. The experiment was performed with three independent replicates (n = 3). For each replicate, six technical replicates were included per group. After incubation in the cell incubator for 1, 2, and 3 days, the plates were removed, and 20 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well under the laminar flow hood. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). The plates were then returned to the incubator for an additional 2 hours in the dark. Following this incubation, the solution was gently mixed to ensure homogeneity, and bubbles were removed. Subsequently, 100 μL from each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Cultivation of 2D and 3D cell spheres

The 3D printed DMF chips were immersed in IPA solution for 24 hours, followed by rinsing with PBS and subsequent exposure to UV light for sterilization. At the beginning of each experiment, 0.05% Pluronic F127 (w/v) was uniformly mixed into the MCF-7 cell suspension. A volume of 0.8 μL of the cell suspension (1 × 10⁵ cells/mL) was then transferred onto the electrodes of the chip. By applying voltage to the electrodes, the cell suspension was directed to move across the electrodes until it reached the 3D microstructures. The DMF chip was subsequently incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 24, 36, and 72 hours. Cell images were acquired through the optical window using an optical microscope, and the number of distributed cells was quantified using ImageJ software. Following the cultivation period, cell viability was assessed using a Live/Dead Cell Staining Kit (Calcein AM/PI). The cells were stained with a PBS solution containing 40 μM Calcein AM and 100 μM PI, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. Subsequently, observation and image acquisition were performed using a fluorescence microscope equipped with 10× or 20× objectives. Viable cells (Calcein AM-positive) exhibited green fluorescence, whereas dead cells (PI-positive) displayed red fluorescence.

SEM imaging

The structural morphology and microstructure of the printed 3D microstructured arrays were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to SEM analysis, the 3D microstructured arrays were allowed to dry overnight in a natural environment and were subsequently coated with gold via sputter deposition. The samples were then analyzed at an acceleration voltage of 12 kV. The dimensions of the 3D microstructures were measured from the SEM micrographs using ImageJ software, with three measurements obtained for each sample.

For the scaffolds incubated with cells, the samples were washed with PBS and fixed overnight in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in PBS. Following fixation, the samples underwent dehydration in a series of ethanol solutions (50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%), and were then further air-dried to prepare them for SEM observation.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data are expressed as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10 statistical software and Excel 2020 software. Statistical analysis was performed using the ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test as well as the t-test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

References

Kamat, A. M., Pei, Y., Jayawardhana, B. & Kottapalli, A. G. P. Biomimetic soft polymer microstructures and piezoresistive graphene MEMS sensors using sacrificial metal 3D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 1094–1104 (2021).

McHugh, K. J. et al. Fabrication of fillable microparticles and other complex 3D microstructures. Science 357, 1138–1142 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Pharmaceutical electrospinning and 3D printing scaffold design for bone regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 174, 504–534 (2021).

Lu, X. et al. 3D microstructure design of lithium-ion battery electrodes assisted by X-ray nano-computed tomography and modelling. Nat. Commun. 11, 2079 (2020).

Su, R., Wang, F. & McAlpine, M. C. 3D printed microfluidics: advances in strategies, integration, and applications. Lab Chip 23, 1279–1299 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Three-dimensional flexible electronics using solidified liquid metal with regulated plasticity. Nat. Electron. 6, 154–163 (2023).

Abuwatfa, W. H., Pitt, W. G. & Husseini, G. A. Scaffold-based 3D cell culture models in cancer research. J. Biomed. Sci. 31, 7 (2024).

Islam, M. et al. Carbon fiber/microlattice 3D hybrid architecture as multi-scale scaffold for tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 126, 112140 (2021).

Ko, J. et al. Microfluidic high-throughput 3D cell culture. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2, 453–469 (2024).

Kim, H. et al. Recapitulated crosstalk between cerebral metastatic lung cancer cells and brain perivascular tumor microenvironment in a microfluidic co-culture chip. Adv. Sci. 9, e2201785 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. 3D printed microfluidic chip for multiple anticancer drug combinations. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 276, 507–516 (2018).

Nocera, G. M. et al. The VersaLive platform enables microfluidic mammalian cell culture for versatile applications. Commun. Biol. 5, 1034 (2022).

Coluccio, M. L. et al. Microfluidic platforms for cell cultures and investigations. Microelectron. Eng. 208, 14–28 (2019).

Jang, K., Sato, K., Igawa, K., Chung, U. -i & Kitamori, T. Development of an osteoblast-based 3D continuous-perfusion microfluidic system for drug screening. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390, 825–832 (2008).

Zhai, J. et al. Drug screening on digital microfluidics for cancer precision medicine. Nat. Commun. 15, 4363 (2024).

Ng, A. H. C., Li, B. B., Chamberlain, M. D. & Wheeler, A. R. Digital microfluidic cell culture. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 17, 91–112 (2015).

Pang, L., Ding, J., Liu, X.-X. & Fan, S.-K. Digital microfluidics for cell manipulation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 117, 291–299 (2019).

Shang, M., Soon, R. H., Lim, C. T., Khoo, B. L. & Han, J. Microfluidic modelling of the tumor microenvironment for anti-cancer drug development. Lab Chip 19, 369–386 (2019).

Zhai, J. et al. A digital microfluidic system with 3D microstructures for single-cell culture. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 6, 6 (2020).

Torabinia, M., Dakarapu, U. S., Asgari, P., Jeon, J. & Moon, H. Electrowetting-on-dielectric (EWOD) digital microfluidic device for in-line workup in organic reactions: a critical step in the drug discovery work cycle. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem. 330, 129252 (2021).

Oliveira, E., Doering, C. & Fouckhardt, H. Optimizing contact angle changes for droplet actuation by optoelectrowetting (OEW): a numerical multi-parameter analysis. Sens. Actuato. A: Phys. 365, 114835 (2024).

Sathyanarayanan, G., Haapala, M. & Sikanen, T. Interfacing digital microfluidics with ambient mass spectrometry using SU-8 as dielectric layer. Micromachines 9, 649 (2018).

Duangrit, N. et al. Terahertz dielectric property characterization of photopolymers for additive manufacturing. IEEE Access 7, 12339–12347 (2019).

Cheng, Z. et al. Superwetting shape memory microstructure: smart wetting control and practical application. Adv. Mater. 33, 2001718 (2021).

Rui, X., Song, S., Wang, W. & Zhou, J. Applications of electrowetting-on-dielectric (EWOD) technology for droplet digital PCR. Biomicrofluidics 14, 061503 (2020).

Sun, T. et al. Preparation of selectively decellular xenoskin and its biocompatibility. Chin. J. Reparative Reconstr. Surg. 24, 668–672 (2010).

Ryan, S.-L. et al. Drug discovery approaches utilizing three-dimensional cell culture. ASSAY Drug Dev. Technol. 14, 19–28 (2016).

Edmondson, R. et al. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay. Drug Dev. Technol. 12, 207–218 (2014).

Chowdhury, S. & Janorkar, A. V. Influence of structure–property relationships of polymeric biomaterials for engineering multicellular spheroids. Bioengineering, 12, 857 (2025).

Chan, Y. H. et al. Three-dimensional spheroid culture enhances multipotent differentiation and stemness capacities of human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells by modulating MAPK and NF-kB signaling pathways. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 17, 1810–1826 (2021).

Foty, R. A simple hanging drop cell culture protocol for generation of 3Dspheroids. JoVE 51, 2720 (2011).

Kapałczyńska, M. et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures – a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch. Med. Sci. 14, 910–919 (2018).

Do, A.-V., Khorsand, B., Geary, S. M. & Salem, A. K. 3D printing of scaffolds for tissue regeneration applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 4, 1742–1762 (2015).

Knight, E. & Przyborski, S. Advances in 3D cell culture technologies enabling tissue-like structures to be created in vitro. J. Anat. 227, 746–756 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Synergistic effect of hierarchical topographic structure on 3D-printed titanium scaffold for enhanced coupling of osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Mater. Today Bio 23, 100866 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515012751); Guangdong Special Support Plan (2023TQ07Z692); Specialized Areas of Key Importance in Ordinary Universities in Guangdong Province (2025ZDZX4037, 2023ZDZX3010); Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) (FDCT0168/2023/RIA3, FDCT004/2023/SKL); University of Macau (MYRG2023-00034-IME).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Lin, X., Li, H. et al. Integrated 3D microstructured digital microfluidic platform for advanced 3D cell culture. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01098-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01098-9