Abstract

Conventional diabetes management requires frequent invasive procedures such as finger-prick blood sampling and subcutaneous injections to coordinate glucose monitoring and medication. Here, we propose a novel, flexible, wearable, battery-free skin patch that synchronizes painless glucose monitoring and regulation capabilities with smartphone-mediated wireless control. This patch integrates bendable fluorescent hydrogel microneedles for minimally invasive glucose monitoring (50 to 450 mg/dL range) and thermoresponsive microneedles for metformin delivery. In diabetic mouse models, it accurately tracked interstitial glucose levels and, upon hyperglycemia detection, reduced blood glucose within 1 h (effects lasting 5–6 h). This system provides glucose monitoring with wireless data transmission and precise drug administration while eliminating pain, infection risk, and high costs. Its lightweight, disposable design offers a practical solution for improved diabetes care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus has reached epidemic proportions, affecting 537 million adults worldwide in 2021, with projections suggesting this will rise to 643 million by 20301,2. Prolonged hyperglycemia can lead to serious complications such as cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and retinopathy3. For patients with pancreatic dysfunction, maintaining glycemic control requires both continuous glucose monitoring and precise therapeutic intervention, currently achieved through painful fingerstick measurements (3–10 daily tests) or invasive subcutaneous continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems4,5. Patients face significant challenges, including painful procedures, frequent infections (12.3%), and prohibitive expenses with current technologies. Additionally, frequent monitoring and medication schedules can significantly disrupt patients’ daily lives, and improper dosages of drugs can also lead to the risk of hypoglycemia6. These unresolved challenges highlight the urgent need for miniaturized, cost-effective solutions that maintain precision while improving user compliance.

Presently, researchers are actively exploring the development of wearable systems that realize glucose monitoring and regulation7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In terms of glucose monitoring, researchers are focusing on minimally invasive methods, such as electrochemical detection using glucose oxidase and boronic acid-based fluorescent and colorimetric methods15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. To overcome challenges associated with external variables (e.g., temperature, pH) and to address issues like contamination and sample dilution, scientists have proposed directly analyzing interstitial fluid (ISF) beneath the skin24,25,26. Metal microneedles have been designed based on electrochemical sensing principles to achieve painless intradermal electrochemical biosensing27,28,29,30. However, due to the flexible nature of human skin and muscle, rigid microneedles may face issues with maintaining consistent contact during body movement, leading to measurement errors. Additionally, the constant relative motion between rigid microneedles and tissue may cause tissue damage. Another significant challenge with electrochemical sensors is their short lifespan, which increases maintenance costs31. Biosensors based on fluorescent and colorimetric methods are susceptible to interference from external light and sensor inaccuracies. Moreover, these systems typically require additional components like optical sensors, increasing their size and reducing wearability32,33.

Regarding glucose regulation, researchers have focused on developing pain-free drug delivery systems, where microneedle technology has garnered significant attention. Microneedles can pierce the skin and create microchannels through which the drug can diffuse into the tissue34,35,36,37. Since the micron-sized needles do not stimulate nerves in the skin, they cause minimal pain. At the current stage, precise control over the drug delivery process remains a critical area of research and is essential for achieving an effective glucose management system38,39,40,41. Furthermore, with the development of integrated circuits and wireless control technologies, although various automated blood glucose monitoring and regulation closed-loop systems have been developed, they still have the aforementioned problems and often rely on battery power, resulting in bulky equipment and poor portability42,43. Although closed-loop systems have great potential in diabetes management, there are still many challenges in miniaturization, improving accuracy, and reducing costs.

Herein, we propose a novel wearable, wireless, battery-free skin patch that synchronizes painless glucose monitoring and regulation capabilities for people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patch combines a glucose monitoring unit, glucose regulation unit, and wireless unit. The patch integrates bendable fluorescent hydrogel microneedles for minimally invasive glucose monitoring and thermoresponsive microneedles for metformin delivery. A flexible polymer substrate adheres to the skin, secured with medical tape, and operates wirelessly via smartphone. The glucose monitoring unit consists of a hydrogel microneedle array functionalized with 9-anthraceneboronic acid (9-ANB), which leverages the fluorescence response of 9-ANB to glucose44,45,46,47. The microneedles painlessly penetrate the skin’s shallow layers, rapidly absorbing ISF. The hydrogel’s 9-ANB reacts with glucose, producing measurable fluorescence changes under UV light. An integrated XYZ true color sensor within the flexible patch detects these changes, providing highly sensitive real-time glucose monitoring. The monitoring data is transmitted via Near Field Communication (NFC) to a smartphone, enabling users to track their glucose levels conveniently. The glucose regulation unit comprises thermoresponsive hydrogel therapy microneedles and a heater. When hyperglycemia is detected, energy is wirelessly transferred via NFC from the smartphone to the patch, activating the heater, which in turn triggers the release of metformin from the thermoresponsive microneedles, ensuring precise and timely drug administration. Our developed flexible, lightweight, low-cost, easily replaceable, wireless, and battery-free skin patch addresses issues related to pain, skin damage, bulkiness, and external environmental interference, effectively lowering blood glucose levels while avoiding the high costs and hypoglycemia risk associated with insulin therapy. Additionally, both the glucose monitoring and thermoresponsive therapy microneedles are easily replaceable, enhancing the convenience and cost-effectiveness for long-term use, offering a promising alternative for improved glucose control and enhanced quality of life for people with diabetes.

Results

Design and structure of the patch

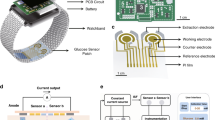

The wearable skin patch can fit closely onto the skin surface and can be fixed with medical tape, enabling wireless communication with a smartphone for real-time glucose monitoring and regulation (Fig. 1a). This integrated system automatically triggers on-demand drug release upon hyperglycemia detection (In this study, we set 250 mg/dL as the drug release threshold.)48,49, achieving precise glycemic control through its three functionally coupled components: a fluorescence-based glucose monitoring unit, a thermoresponsive drug delivery unit, and an NFC wireless control circuit (Fig. 1b). The glucose monitoring unit incorporates a 1.5 × 1.5 cm2 hydrogel microneedle array composed of PVP/PVA composite and functionalized with 9-anthraceneboronic acid (9-ANB) for glucose-responsive fluorescence detection, accompanied by a 365 nm μ-LED excitation source, a 410–480 nm filter which effectively mitigates interference from both the UV LED emission and variations in ambient light, and an XYZ true color sensor for fluorescence intensity quantification, along with embedded signal processing circuitry for real-time data conversion. Symmetrically configured, the drug delivery unit features an identical footprint hydrogel (PVP/PVA) microneedle array loaded with metformin and coated with thermoresponsive n-tridecanoic acid (phase transition at 42 ± 0.5 °C), activated by a thin-film heater (40 nm Cr and 200 nm Au) with precision temperature control. The functions of both units are wirelessly powered and controlled via an NFC module that interfaces with a smartphone, enabling an integrated approach to glucose monitoring and regulation.

a Schematic illustration of the application and use of the wireless skin patch. b Exploded view of the wireless skin patch, comprising a glucose monitoring unit, a glucose regulation unit, and a wireless control unit. The inset depicts the circuit diagram of the entire system. c The operational principle of the wireless skin patch on human skin, detailing the four steps: patch application, glucose sensing, drug delivery, and patch removal, completing one cycle of patch operation. d Optical image of the wireless skin patch. Scale bars, 1 cm. e Optical image of the data processing circuitry of the wireless skin patch. f Optical image of the sensing circuit and heater of the wireless skin patch. g Optical images of the wireless skin patch under mechanical deformation, demonstrating both inward and outward bending. Scale bars, 1 cm

The NFC control circuit facilitates wireless power delivery and data communication between a smartphone and the diabetes management patch. Figure 1b illustrates the circuit block diagram, while the detailed schematic and PCB layout are available in Figs. S1 and S2. Initially, the smartphone activates its NFC wireless power transfer functionality. Upon approaching the NFC control circuit’s antenna, the NFC chip generates an analog voltage output through its integrated energy harvesting functionality, powering itself, the MCU, the XYZ true color sensor, the UV excitation μ-LED, and the heater. The MCU establishes communication with the XYZ true color sensor through the I2C protocol, enabling sensor parameter configuration and sensing data acquisition. The primary function of the XYZ true color sensor is to convert captured light signals into XYZ tristimulus values, adhering to the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) 1931 color space standard. XYZ represents the tristimulus values of the human color vision system, facilitating standardized and precise representation of color information. During color sensor measurements, the MCU simultaneously controls the activation of the UV excitation μ-LED via switch S1. The μ-LED is directly powered by the NFC output supply voltage to ensure adequate optical power. Following the completion of color data measurement (taking approximately 50 ms), the MCU commands the color sensor to enter the Power Down state and deactivates the UV μ-LED to minimize power consumption. Subsequently, the MCU determines whether to activate the heater switch S2 based on pre-defined XYZ ratio thresholds (Supplementary Note 1). The acquired XYZ values from the color sensor are then transmitted to the NFC chip via the I2C protocol. By bringing the smartphone into proximity with the NFC antenna again, the color data stored within the NFC chip can be retrieved through NFC functionality.

The application procedure of the patch is illustrated in Fig. 1c. Designed as a flexible skin-adherent device measuring 3.7 × 2.3 × 0.3 cm and weighing 1.94 g, it features dual-sided circuitry that integrates data processing, sensing, and heater modules (Fig. 1d–f). The compliant materials and structural design ensure conformal contact with human skin during deformation (Fig. 1g). Through gentle pressure application, the 650-μm microneedles penetrate the epidermis in a minimally invasive manner to access glucose-containing interstitial fluid. The 9-ANB-functionalized sensing array emits blue fluorescence at approximately 450 nm when excited by 365 nm ultraviolet light, showing an inverse correlation between fluorescence intensity and glucose concentration. The fluorescence variations are detected by an XYZ true color sensor, processed, and wirelessly transmitted to a smartphone via NFC. Upon detection of hyperglycemia, the system activates the smartphone-powered heater to melt the thermoresponsive phase-change material coating on the drug-loaded microneedles, enabling rapid metformin release. Owing to the low cost, painless operation, and easy replaceability of the array, the patch supports a single-use paradigm—following one complete monitoring-regulation cycle, the array can be replaced for subsequent blood glucose management cycles.

Glucose monitoring unit

The glucose monitoring unit involves two critical steps: ISF absorption by microneedle array and fluorescence detection. The glucose concentration-responsive bendable hydrogel microneedles have a simple two-layer structure. To prepare the microneedles, we first prepared a microneedle precursor solution (PPA solution) containing PVP, PVA, and 9-ANB, and injected the solution into the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microneedle mold. The solution was dried fully to form the microneedle tip, and then the PVA solution was injected into the backing layer. After drying thoroughly again, the microneedle array is removed from the mold (Fig. 2a). Detailed information on the preparation of the microneedle array is available in Methods. The PVP has hydrophilicity and high mechanical strength, making the microneedle tip quickly absorb the ISF and have enough mechanical strength to pierce the skin. The PVA has good fluorescence enhancement ability, flexibility, and biocompatibility. The backing layer of the PVA base has good flexibility (Fig. 2b), achieving a tight fit to the skin. The tip and the base have different hardness. The rigid microneedle tips enable reliable epidermal penetration, while the compliant substrate maintains skin conformability. The microneedle array demonstrates remarkable mechanical strength, withstanding pressures up to 18.2 N (Fig. 2c) without significant risk of fracture. A single microneedle can withstand a pressure of about 0.2 N, much higher than the 0.045 N required to puncture the stratum corneum50,51. Notably, the incorporation of 9-ANB has a negligible impact on the mechanical strength of the microneedles (Fig. 2c). Under ultraviolet irradiation, 9-ANB exhibits a bright fluorescence emission typically in the blue-violet region, with an emission wavelength of around 400–450 nm (Fig. 2d). Upon interaction with glucose, the formation of a boric acid ester alters its electronic structure and vibrational characteristics, leading to a marked quenching of fluorescence intensity (Fig. S3). The 9-ANB hydrogel microneedles exhibit an excitation wavelength range of 250–370 nm, with a peak around 365 nm, and an emission wavelength range of 410–460 nm, peaking at approximately 450 nm (Fig. 2e). The fluorescence intensity of both 9-ANB solution and microneedles was measured after continuous excitation by a 28 mW μ-LED for durations ranging from 0.1 to 10 min. The 9-ANB solution retained over 89% of its initial fluorescence intensity (Fig. S4a), while the microneedles maintained more than 88% of their original signal (Fig. S4b). In the patch system, the μ-LED operates in pulsed mode during a single use cycle, with an activation period of approximately 1 s per measurement. This design ensures that UV excitation does not cause significant fluorescence decay during the measurement process. As shown in Fig. S5, mixing a 0.1 mmol/L solution of 9-anthraceneboronic acid with glucose solutions of varying concentrations resulted in distinct changes in fluorescence. The fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing glucose concentration. It is important to note that the slow water absorption of the microneedles causes the fluorescence intensity to be significantly influenced by the contact duration with ISF. We first investigated the temporal variation in the fluorescence spectrum of the microneedles at specific glucose concentrations. As shown in Fig. S6, higher glucose concentrations (0, 50, 250, and 450 mg/dL) led to a gradual decrease in fluorescence intensity along with a spectral red-shift. At a fixed glucose concentration, the fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing incubation time and stabilized after 15 min. Based on these findings, we selected 15 min as the standard incubation time for all subsequent experiments.

a Fabrication process of the glucose concentration-responsive bendable hydrogel microneedle array. b Optical image of the glucose concentration-responsive bendable hydrogel microneedle array. Scale bars, 25 mm. The inset shows an optical image of the microneedles bent at a 90° angle, demonstrating their flexibility. c Mechanical properties of blank PVP/PVA hydrogel microneedles compared with PVP/PVA/9-ANB hydrogel microneedles. d The absorption spectrum and fluorescence emission spectrum of the 9-ANB material. e 3D fluorescence profile of the PVP/PVA/9-ANB hydrogel microneedles. f In vitro characterization results of the glucose concentration-responsive bendable hydrogel microneedle array, including optical (Scale bars, 10 mm) and fluorescence microscopy images (Scale bars, 300 μm, n = 10). g The response of microneedle arrays to glucose and interfering ions. h SEM images of microneedles after dissolving upon insertion into a porcine skin model. Scale bars, 180 μm. i The color change of the microneedle array after absorbing rhodamine B solution. The inset shows an optical image of a 2.25 cm² microneedle array absorbing a Rhodamine B solution

In our patch design, the integrated XYZ true color sensor serves to measure the microneedle-emitted fluorescence and represent it digitally in the XYZ color space. To ensure selective detection, an optical filter (transmission range: 410–480 nm, Fig. S7a) is positioned between the microneedles and the color sensor to transmit the specific fluorescence signal. To investigate the shielding effect of the optical filter against ambient light interference, we compared the sensing data obtained with and without the integrated filter. As shown in Fig. S7b, under identical lighting conditions (standard laboratory lighting, 500 lux) and glucose concentration variations, the system with the filter exhibited a greater variation range in the Z value. Furthermore, when both systems were exposed to different lighting environments—including darkness, standard laboratory lighting, and direct desk lamp illumination (2000 lux)—it was clearly demonstrated that the system with the filter showed significantly less variation in the XYZ parameter in response to the same glucose concentration, as illustrated in Fig. S7C. Under the three lighting conditions, the variation range of the XYZ value without the filter was 3–10%, 3–17%, and 6–24%, respectively. In contrast, with the filter, the variation was significantly reduced to 0.4–1.3%, 0.7–1.3%, and 0.3–2%, respectively (Ranges calculated as max-min of X/Y/Z at a constant glucose concentration). Therefore, the optical filter effectively attenuates ambient light noise, thereby significantly mitigating its interference with sensing accuracy.

We also evaluated how the microneedle-ISF contact time affects the measurements from the XYZ true color sensor. As shown in Fig. S8a, the fluorescence signal evolved significantly during the incubation period and stabilized after 15 min across the tested glucose concentrations (50, 250, and 450 mg/dL). Moreover, the change in the sensor’s signal value (XYZ) at 10 min of incubation was smaller than that at 15 min (Fig. S8b). Therefore, a 15-min incubation time was established as the standard protocol for all subsequent measurements. The microneedle glucose sensor unit demonstrated robust capability for transdermal glucose measurement across a concentration range from 50 mg/dL (hypoglycemic level) to 450 mg/dL (above hyperglycemic level). Fluorescence spectra of the microneedles after exposure to PBS solutions with varying glucose concentrations were recorded. As clearly shown in Fig. S9, higher glucose concentrations led to a decrease in fluorescence intensity and a concomitant red-shift in the emission wavelength. The fluorescence intensity of microneedles under different glucose concentrations was analyzed by a series of optical images and an XYZ true color sensor. Under standard laboratory lighting conditions with a 15-min incubation period and the phone placed flush against the patch (the power of μ-LED :27 mW), the Z-value of the microneedle fluorescence response detected by the XYZ true color sensor decreased by approximately 13.7% as glucose concentration increased from 50 mg/dL to 450 mg/dL (hyperglycemic level, pH 7.3), as shown in Fig. 2f. Compared to the 10-min incubation (Fig. S8b), the 15-min period resulted in a more pronounced response to changes in glucose concentration. Furthermore, since the distance between the phone and the patch influences the power supply and consequently the μ-LED output, proper operation and distinguishable fluorescence changes require the separation to be within 3 mm. In addition to direct contact (0 mm), we evaluated system performance at distances of 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm, analyzing how μ-LED power and XYZ values respond to varying glucose concentrations. As illustrated in Figs. S10a–c, reducing the separation decreases μ-LED power, while at a given glucose concentration, the proportion of the Z-value increases significantly. Moreover, under constant excitation power, the trends in XYZ proportions remain consistent across all distances. Notably, closer distances result in a wider dynamic range of these proportional changes. Optical images of the microneedles under different excitation powers and glucose concentrations are also provided (Fig. S10d). These visually confirm that higher μ-LED power enhances fluorescence intensity and raises the Z-value proportion, whereas increased glucose concentration consistently reduces fluorescence across all power levels. The results demonstrate that the sensor remains effective in detecting glucose concentration across a range of operating distances. Through data fitting, we have established calibrated measurement standards for glucose concentration at various distances, enhancing the system’s applicability in diverse scenarios.

We further investigated the impact of external light direction and ambient conditions on sensor performance. Figure S11 provides a schematic of the experimental setup, where the light source was positioned either on the sensor side or the opposite side of the patch. When light entered from the microneedle side, the influence of different lighting conditions on the sensor signal under the same glucose concentration was more pronounced. Under stronger external light (Fig. S11a), the X and Y values increased (ranging from 1.5–10% and 3.5–12%, respectively), while the Z value decreased (ranging from 5.0–12%). However, when the microneedles were inserted into the skin (Fig. S11b), the variation in sensor data across different lighting conditions was significantly reduced, with a maximum fluctuation of 2% for Y and less than 0.5% for Z. This improvement can be attributed to the flexible patch structure, which ensures close contact with the skin and minimizes external light intrusion after insertion. To account for ambient light variations, we calibrated the relationship between the sensor’s XYZ values and glucose concentration under both dark and direct light conditions (Fig. S11c and S11d), establishing alternative calibration standards for glucose measurement. This allows selection of the appropriate calibration model based on the ambient light during use. Additionally, to further mitigate the influence of external light fluctuations, we designed and 3D-printed a flexible, lightweight, and opaque encapsulating structure for use with the patch (Fig. S11e). This structure can be attached when ambient light varies intensely, ensuring the patch operates in a dark environment. We also calibrated the relationship between the XYZ values and glucose concentration with the structure installed, providing another reliable calibration standard for glucose sensing.

PBS and glucose-supplemented PBS (250 mg/dL) solutions at different pH levels were applied to the microneedle array, with fluorescence spectra acquired after 15-minute incubation. As shown in Fig. S12a, while fluorescence intensity in PBS decreased with rising pH, the variation within the physiological ISF range (7.3–7.5)52 was minimal ( <1.2%). A similar trend was observed in Glu-PBS (Fig. S12b). Analysis demonstrated enhanced response to glucose concentration variations with increasing pH (Fig. S12c). Sensor measurements showed decreasing Z-values and increasing X-values with higher pH, though fluctuations remained below 0.5% within the ISF range (Fig. S12d). The responsiveness of X and Y values to glucose improved with pH elevation. The correlation between XYZ outputs and glucose concentration at pH 7.5 (Fig. S12e) showed <0.5% deviation from standard calibration, providing reliable reference for different pH conditions. Optical images (Fig. S12f) visually confirmed gradual fluorescence attenuation with increasing pH, alongside enhanced response to glucose changes. The system maintained excellent stability within physiological ISF pH variations, ensuring practical reliability.

We evaluated the fluorescence stability of the glucose-monitoring microneedles developed in this study. The microneedle array was exposed to excitation light (365 nm, 30 mW) for 30 seconds, taking 10 measurements every 5 days for 45 days. After continuous exposure, the microneedles retained 82% of their initial fluorescence intensity (Fig. S13), demonstrating considerable stability over the testing duration. Furthermore, we evaluated the fluorescence stability of the microneedles by testing samples aged for 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 days in both glucose-free solution and 250 mg/dL glucose solution. The results demonstrated that the microneedles maintained over 85% of their initial fluorescence intensity within 30 days (Fig. S14a), with response variation to glucose within 8% (Fig. S14b). We also confirmed that patches incorporating aged microneedles remained responsive to glucose concentration changes after storage, enabling post-storage calibration (Fig. S14c). Optical images visually corroborated these fluorescence characteristics (Fig. S14d). The specificity of the hydrogel microneedles was systematically evaluated by placing the microneedles in gelatin loaded with potential interferents (Na+ 145 mM, K+ 5.0 mM, Ca²+ 1.3 mM, uric acid 0.45 mM, ascorbic acid 0.1 mM, and lactic acid 2.2 mM) alongside glucose controls. Following 10-minute incubation at 37 °C, UV irradiation (365 nm, 30 mW) revealed exclusive fluorescence quenching (ΔF/F0 = 48 ± 1%) in glucose-exposed microneedles, while other analytes induced negligible signal variation ( <8%) (Fig. 2g). This confirms the 9-ANB’s selective binding to glucose. To simulate human tissue fluid composition, lactate Ringer’s solution supplemented with bovine serum albumin was utilized. Fluorescence spectra of both 9-ANB solution and microneedles were examined under exposure to PBS solutions and simulated tissue fluid containing varying glucose concentrations. The results confirmed that intrinsic tissue fluid components do not interfere with the glucose concentration-dependent fluorescence response of the microneedles (Figs. S15a and S15b). Furthermore, when the patch system was exposed to glucose-supplemented simulated tissue fluid (Fig S15c), the sensor’s XYZ values remained consistent with those presented in Fig. 2f, demonstrating maintained system stability. Additional validation through experiments in ex vivo porcine tissue pre-injected with different glucose concentrations yielded measurements comparable to those obtained in dark environments (Fig. S15d), further confirming sensor reliability in tissue-mimicking conditions.

The microneedles exhibit biocompatibility and are designed to dissolve in the body over time, eliminating the need for removal. For each measurement cycle, only the microneedle array requires replacement, while the circuit of the patch remains reusable. We investigated the dissolution process of the glucose-monitoring microneedles in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Upon partial dissolution of the microneedle tips, the PVA backing layer also gradually dissolved (Fig. S16). Figure 2h presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images that validate the extent of tip dissolution. Microneedles with an initial length of 650 μm reduced to approximately 150 μm after 1 h of insertion into a gelatin skin model. We assessed the water absorption capacity of the hydrogel microneedles by applying them to an agar surface infused with Rhodamine B and recorded the color changes of the microneedles through optical images and characterized the content of Rhodamine B using a spectrophotometer after 10, 20, and 30 min of contact. The water absorption capacity of the microneedles exhibited a time-dependent increase, concomitant with a gradual rise in Rhodamine B content, until reaching equilibrium at approximately 20 min (Fig. 2i). With fixed needle density and length, different areas of microneedle units were observed. All tested arrays exhibited uniform colorimetric changes during operation. Gravimetric analysis demonstrated a linear correlation between water absorption capacity and array surface area. The selected 1.5 × 1.5 cm microneedle array absorbed approximately 42 mg of water within 10 min and reached a saturated state of about 97 mg after 30 min (Fig. S17).

Glucose regulation unit

Glycemic control in diabetes management typically requires insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents. Our patch incorporates a thermally-activated microneedle array for painless metformin delivery, featuring a trilayer architecture: comprising a backing layer, needle tips, and a surface coating of n-tridecanoic acid film (melting point 42.0 ± 0.5 °C) that triggers release upon heating (Fig. 3a). Under the n-tridecanoic acid coating, the transparent microneedle array exhibits a white, semi-translucent appearance (Fig. 3b). Detailed fabrication parameters are provided in Methods (Fig. S18). The drug loading capacity can be adjusted according to actual requirements. To enhance drug release kinetics, we optimized the PVP: PVA ratio to increase the PVP content, thereby improving the microneedles’ hydrolysis capacity and accelerating their disintegration in ISF. While higher PVP content increased rigidity and brittleness, the microneedles retained sufficient mechanical strength for skin penetration, with a minimum fracture strength of 8 N (0.08 N per needle) — well above the 0.045 N required for stratum corneum penetration. Notably, the n-tridecanoic acid coating had negligible effects on mechanical properties (Fig. 3c).

a Fabrication process of the thermoresponsive microneedle array. b Optical image of the thermoresponsive microneedle array. Scale bars, 300 μm. c Mechanical properties of PVP/PVA hydrogel microneedles (PVP/PVA MN), PVP/PVA/Metformin hydrogel microneedles (PPM MN), and thermoresponsive microneedles (PPMT MN). d SEM image of PVP/PVA/Metformin hydrogel microneedles. Scale bars, 400 μm. e SEM image of a single PVP/PVA/Metformin hydrogel microneedle. Scale bars, 150 μm. f Surface morphology of PVP/PVA/Metformin hydrogel microneedles. Scale bars, 150 nm. g SEM image of a single thermoresponsive microneedle. Scale bars, 150 μm. h Surface morphology of the thermoresponsive microneedles. Scale bars, 150 nm. i FTIR of the thermoresponsive microneedles

SEM images reveal the morphology of the drug-loaded microneedle array (Fig. 3d), tip details (Fig. 3e), coated array (Fig. S19), and coating close-ups (Fig. 3g). The bare microneedle surface exhibits a smooth and dense structure (Fig. 3f), while the coated microneedles display a distinctly wrinkled surface layer (Fig. 3h). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy confirmed both the PVP/PVA hydrogel matrix composition (characteristic peaks at 2926 cm−1 for C-H stretching, 1646 cm−1 for PVP’s C = O, and 1080 cm−1 for PVA’s C-O) and successful metformin loading (drug-specific peaks at 3409 cm−1 N-H, 1377 cm−1 C-N, and 1189 cm−1 biguanide vibration) in the thermally responsive microneedles (Fig. 3i).

We evaluated the efficiency of the NFC-powered functionality, observing changes in voltage and current as the distance between the smartphone and the patch varied (Fig. 4a). The voltage remained relatively stable at approximately 3.4 V within a distance of 3 cm. The current was sufficient to meet the basic power requirements when the distance was less than 7 mm. Detection of hyperglycemia triggers the thermal actuation of the heater under a microneedle array. The detailed manufacturing method of the heater is introduced in Methods. Infrared thermography reveals that the heater, operating at 12 mW, uniformly increases in temperature from 30 °C to approximately 46 °C. Upon cessation, the temperature rapidly and uniformly decreases (Fig. 4b). The heater’s thermal performance varies with different power settings, typically reaching a stable maximum temperature within 7 s and cooling in 5 s. This demonstrates excellent heat generation and rapid thermal response (Fig. 4c). To ensure biosafety and achieve the threshold for drug release, the heater is set to operate at 12 mW, maintaining a temperature of approximately 46 °C for 5 s. We evaluated the dissolution process of the microneedle array in vitro to observe drug release during heating. Upon activation of the heater, the surface coating of tridecanoic acid on the microneedle array begins to melt from the center as the temperature rises, exposing the microneedle tips. After 10 s of heating, the white tridecanoic acid coating starts to melt from the center, revealing the transparent microneedles. By 20 s, the coating is completely melted, leaving the microneedles fully exposed (Fig. 4d). Figure 4e illustrates the temperature profile during the phase transition of the microneedle (MN) array, with the tip region reaching a peak temperature of 44 °C. The thermal imaging data reveal a rapid temperature increase within 10 s and up to 42 °C for the activation period. Infrared thermography revealed sustained temperatures exceeding 42 °C at the microneedle tips. The heating will be stopped once the layer is completely melted. As the coating melts, the tips of the microneedles gradually become exposed and dissolve. The fluorescence microscopy captured the temperature-activated dissolution dynamics of dye-loaded microneedles for simulating the release process of drugs in medium (medical ultrasound gel). The microneedle tips exhibited linear erosion at 20 ± 1 μm/s, with simultaneous radial diffusion of fluorescent cargo into the surrounding medium (Fig. 4f). Microneedle arrays loaded with varying masses (5, 10, and 15 mg) of fluorescent markers were inserted into medical ultrasound gel. Fluorescence intensity within the gel was quantified at predetermined time intervals (0, 10, 15, and 20 s) following thermal activation. Fluorescence monitoring showed that microneedle arrays loaded with different masses of fluorescent material exhibited consistent linear dissolution kinetics (approximately 0.062, 0.134, 0.156 a.u./s) in medical ultrasound gel. It was confirmed that the amount of drug released could be regulated by the drug loading amount (Fig. 4g).

a Relationship between the output voltage and current of the NFC energy supply module and the distance from the smartphone. b Thermal interface during the operation of the heater. The inset shows an optical image of the heater. Scale bars, 3 mm. c Heating and temperature recovery performance of the heater at different power levels. d Optical images of the melting process of the coating layer on the thermoresponsive microneedles. Scale bars, 3 mm. e The temperature variation on the microneedle surface. The inset displays the infrared thermal image of the microneedle array. f Fluorescence microscopy images depicting the drug release process from the thermoresponsive microneedles. Scale bars, 140 μm. g Real-time fluorescence quantification of microneedle drug release under thermal activation. h Fluorescence imaging and quantitative analysis of Cy3-metformin penetration in skin tissue

To investigate drug delivery efficacy, we loaded microneedle arrays with 5 mg of Cy3-metformin and applied the complete system to the dorsal skin of mice in the experimental group. We applied a solution containing the same amount of metformin drug on the backs of mice, and applied the patches without the therapeutic microneedles to the control group of mice. Both groups simultaneously activated the heat-triggered drug release function. Skin samples were collected at 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 h post-heating for fluorescence imaging analysis. In Fig. 4h, by analyzing the fluorescence intensities within the dermis layer and near the muscle layer, the Cy3-metformin administered through the microneedle patch exhibited a better subcutaneous penetration effect. At 0.5 h, the fluorescence intensity near the dermis and muscle tissues of the experimental group was higher than that of the control group. As time elapsed, the fluorescence intensity in the subcutaneous area of the experimental group increased faster than that of the control group, confirming the better drug delivery effect of the therapeutic microneedles.

Treating diabetic mice

To verify the patch’s ability to monitor glucose levels in living tissues and release metformin under hyperglycemic conditions for blood glucose regulation, we conducted in vivo experiments by applying the patch to the backs of diabetic mice (Fig. 5a). Supporting information Movie S1 is a video recording of mice wearing the patches and the operation of the patches. In Fig. 5b, to facilitate the visualization of microneedle fluorescence beneath the patch, we applied the microneedles directly to the back of a mouse, where blue fluorescence was observed under UV light. To monitor the drug release process powered by smartphone NFC on the mouse’s back, a temperature probe was positioned on the heater electrode, and infrared thermography was used to capture the changes in surface temperature (Fig. 5c). A marked increase in temperature was observed at the heating electrode, with the heater reaching approximately 46 °C. Due to the patch’s effective insulation, the external temperature increased by only around 6 °C (Fig. 5d).

a Set up an image of the glucose monitoring/regulation experiment using a diabetic mouse model. Scale bars, 7 mm. b Fluorescence image of the glucose monitoring unit microneedles applied to the back of a mouse. The inset shows an optical image of the microneedles in place. Scale bars, 10 mm. c Thermal interface of the skin patch in operation on the back of a mouse. Scale bars, 15 mm. d Temperature changes during the heating and cooling phases while the wireless skin patch is functioning on the back of a mouse. e–g In vivo results obtained using a skin patch and a glucometer (black, glucose concentration measured by the glucometer; red, relative fluorescence intensity of X, Y, and Z). h Blood glucose variations in mice during the glucose regulation process using the skin patch (n = 5). i H&E staining of mouse skin after microneedle insertion. Scale bars, 200 μm. j Immunofluorescence staining of mouse skin after microneedle insertion, detected on Day 1, Day 3, and Day 5, showing DAPI, CD206, and CD68. Green and red fluorescence indicate macrophages: green (M2 macrophages), red (total macrophages). Scale bars, 150 μm

We conducted experiments on 10 diabetic (db/db) mice under both fasting and postprandial conditions. First, commercial sensors were used to collect mouse tail venous blood to measure blood glucose. Blood glucose levels were first measured using a commercial sensor via tail vein blood collection. The patch was then applied to the dorsal region of each mouse. To account for the known physiological delay of interstitial glucose levels relative to blood glucose and the required incubation time for the microneedles to equilibrate with ISF, patch measurements were initiated 10 min after the commercial sensor readings. Smartphones use NFC to activate the circuit, which powers UV LEDs for fluorescence excitation and initiates color sensor measurements. Data is then sent back to the mobile interface. In all ten mice, the patch successfully measured and transmitted data. When blood glucose levels increased, the sensor detected a decreased proportion of Z-value alongside elevated proportions of X- and Y-values, demonstrating favorable tracking performance. This confirmed successful monitoring of murine blood glucose levels. (Fig. 5e–g).

Therapeutic effects are tested in vivo using 8–10 weeks-old diabetic (db/db) mice using a genetically derived diabetic animal model. After measuring fasting blood glucose levels in 20 mice, they were randomly divided into four groups. One group served as the blank control (Blank group), with mice allowed free access to food. Another group, the patch therapy group (Therapy group), had mice wearing the patch while also having free access to food. The positive control group remained fasting throughout the experiment, while the patch control group (Control group) wore the patch but also remained fasting. Blood glucose levels were strictly monitored by commercial blood glucose sensors throughout the study. In the blank group, blood glucose levels rapidly increased and remained elevated after the mice freely consumed food. In the therapy group, blood glucose levels initially rose following food intake, but once the patch detected high glucose concentrations, metformin release was triggered, resulting in a decrease in blood glucose in one hour, which remained low for 5–6 h. After the drug’s effect diminished, blood glucose levels began to rise again. The positive control group showed a continuous decrease in blood glucose due to fasting, while the control group, despite wearing the patch, did not trigger metformin release and exhibited glucose levels similar to those of the fasting group. This study demonstrates that the patch can effectively regulate blood glucose levels in db/db mice by triggering timely metformin release in response to hyperglycemia while maintaining drug retention under normoglycemic conditions. The glucose-responsive drug delivery system showed significant therapeutic efficacy in glycemic control (Fig. 5h). Furthermore, we evaluated the glycemic control effects of metformin administered via microneedle patch, oral gavage, and subcutaneous injection. The results demonstrated that microneedle-mediated transdermal delivery via the patch provided sustained blood glucose regulation over an extended period in mice (Fig. S20a). Histological analysis (H&E staining) of intestinal tissues after 7 days of treatment revealed mild intestinal inflammation in the oral metformin group, whereas no inflammatory response was observed in the microneedle patch group (Fig. S20b).

Histological analysis via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining demonstrated that the microneedles effectively penetrated murine skin to a depth of approximately 450 μm, with subsequent tissue regeneration completing within 2 h post-application. The tiny holes formed after the microneedles pierce the skin were observed, showing partial micropore closure at the 0.5-h timepoint and complete epidermal restoration by 2 h (Fig. 5i), confirming the transient nature of microneedle-induced skin perforations and the rapid healing capacity of the skin. Optical images from a top view confirmed that the mouse skin returned to its original state without injury after microneedle removal (Fig. S21). To rigorously assess the patch’s biocompatibility, we compared cell morphology and proliferation kinetics of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NIH-3T3) cultured with PDMS material (simulating skin-contact conditions) against blank controls. Quantitative analysis at 24, 48, and 72-h intervals demonstrated equivalent cell characteristic morphologies between groups. Calcein-AM/PI viability assays revealed comparable green fluorescence intensities (viable cells) in material-exposed cultures versus controls, with complete absence of red fluorescence (dead cells), conclusively establishing the non-cytotoxic nature of the patch materials (Fig. S22). To evaluate the biocompatibility of our microneedle, immunofluorescence staining was conducted to examine the distribution of activated macrophages. Anti-CD206 antibody was used to selectively identify M2 macrophages; anti-CD68 antibody was used for staining total activated macrophages; and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for counterstaining cell nuclei. Following microneedle treatment, the mouse skin was fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Total macrophages (red) and M2 macrophages (green) were visualized in Fig. 5j. On day 1, the infiltration of both total macrophages and M2 macrophages was observed due to microneedle penetration; additionally, a significant reduction in macrophage presence was confirmed on days 3 and 5 (Fig. S23), demonstrating the biocompatibility and reversibility of our microneedles following insertion.

Discussion

In our study, we have successfully developed a novel flexible, wearable, and battery-free skin patch that integrates real-time glucose monitoring and on-demand metformin therapy through a minimally invasive platform. The system features 9-ANB-functionalized sensing microneedles for precise glucose detection (50–450 mg/dL range) and thermoresponsive microneedles for controlled drug release, demonstrating rapid response to hyperglycemia in diabetic mouse models while maintaining stable glycemic control for 5–6 h per administration. In vivo studies confirmed the patch’s excellent biocompatibility and its ability to effectively regulate blood glucose levels, addressing key limitations of current diabetes management technologies through its pain-free operation with microneedles, wireless functionality, and low manufacturing cost. This innovative platform represents a significant advancement in closed-loop diabetes care, offering a comfortable, cost-effective, and clinically effective solution that could potentially improve the quality of life for millions of diabetes patients worldwide.

Materials and methods

Materials

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), Cy3-NHS ester, were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Tridecanoic acid and 9-anthraceneboronic acid were obtained from Shanghai Bepharm Co., Ltd. Anhydrous ethanol was supplied by Chengdu Jinshan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Metformin was procured from Chengdu Kowo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Optical filters were sourced from Shenzhen Infrared Laser Technology Co., Ltd. The AS73211-AQFM XYZ true color sensor was acquired from AMOSRAM. The 365 nm μ-LED was purchased from Shenzhen First μ-LED Electronics Co., Ltd. The Atmega328P microcontroller (MCU) was purchased from Microchip Technology Inc. The NFC chip (ST25DV04K) was obtained from STMicroelectronics, and the NMOS transistors (DMN1260UFA) were sourced from Diodes Incorporated. Diabetic mouse models (8-10 weeks old) and Balb/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Changzhou Cavens Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. Anti-CD206 (ab300621), anti-CD68 (GB113109), HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (GB23303), TSA (Cy3-Tyramide) (G1223), bovine serum, and PBS buffer were purchased from Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Blood glucose meters were obtained from Sinocare Inc.

Glucose sensing microneedle array preparation

The microneedles were fabricated by first preparing a 12 wt% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution through dissolving PVA powder in distilled water at 95 °C with continuous stirring at 300 rpm for 3 h until a homogeneous viscous solution was obtained. After cooling to room temperature, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added at a PVA to PVP mass ratio of 3:4 under continued stirring until complete dissolution to form a clear hydrogel solution. Separately, a 0.02 M solution of 9-anthraceneboronic acid was prepared in 52% ethanol. The two solutions were then mixed at a 1:1 volume ratio and stirred at 300 rpm for 20 min to ensure homogeneity. The resulting mixture was carefully loaded into PDMS molds through multiple aliquots, followed by centrifugation and vacuum treatment to eliminate air bubbles and ensure complete mold filling. The molds were subsequently dried at 35 °C for 24 h to form the microneedle tips. A PVA backing layer was then applied by casting pure PVA solution over the needle array and drying again at 35 °C for 24 h, yielding the final sensing microneedle array.

Glucose therapy microneedle array preparation

A 12 wt% PVA solution was first prepared using the method described for the sensing microneedle array. PVP was then added to the PVA solution at a mass ratio of 2:1 (PVA), and the mixture was stirred until the PVP was fully dissolved, resulting in a clear hydrogel solution. Metformin was subsequently added to the hydrogel solution to achieve a final concentration of 4 wt%. A double-layer microneedle structure was then fabricated using the previously described method. After the microneedles were formed, a coating of tridecanoic acid was applied by spraying the liquid onto the microneedles in a 45 °C incubator, forming a protective layer. The microneedles were then cooled to room temperature. The total mass of the microneedles is approximately 0.58 g. The drug loading capacity can be adjusted according to actual requirements by changing the drug concentration and the area of microneedles.

NFC control circuit preparation

Figure S1 presents the schematic diagram of the NFC control circuit. The MCU (Atmega328P) operates based on an 8 MHz internal oscillator to minimize component count and power consumption, with reserved programming and debugging interfaces. The NFC chip (ST25DV04K), compliant with ISO/IEC15693 and featuring energy harvesting capability, communicates with the MCU through the I2C protocol. The XYZ true color sensor (AS73211) is a low-power, low-noise integrated XYZ true color sensor. Leveraging its irradiance responsivity factor and conversion time, the AS73211 supports an extensive dynamic range of up to 3.43E + 10 (resolution multiplied by gain range). It achieves an accuracy of up to 24-bit signal resolution (internal via I2C and a 16-bit shifter) with an irradiance responsivity per count down to 0.5 pW/cm2. In the Power Down state, the power consumption of the AS73211 is negligible. The activation of the UV excitation μ-LED and the heater is achieved by controlling the switching of NMOS transistors (DMN1260UFA) through the MCU’s GPIO pins.

The entire NFC control circuit is fabricated using flexible printed circuit (FPC) technology (Fig. S2), employing a PI substrate with a thickness of 0.2 mm. The copper traces have a thickness of 35 µm, and the pad surfaces undergo a gold immersion process to prevent oxidation. The circuit includes two reserved pads for connecting the heater. The NFC antenna adopts a rectangular planar coil design with an inductance of approximately 3.774 µH. It resonates at 13.56 MHz in conjunction with the NFC chip’s internal 28.5 pF capacitor and an external parallel 8 pF capacitor, enabling wireless communication and power transfer for NFC functionality.

Heater preparation

A polyimide film substrate was cleaned sequentially with acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water, followed by nitrogen blow drying. A positive photoresist (S1813) was spin-coated onto the substrate at 4000 rpm for 30 s to achieve a 1.5 µm-thick layer, then soft-baked at 90 °C for 1 min. The serpentine electrode pattern was defined using UV photolithography with a mask and an exposure dose of 100 mJ/cm² for 5 s. The exposed photoresist was developed in MF-319 developer for 30 s, rinsed with deionized water, and dried with nitrogen. Following a hard bake at 120 °C for 2 min, a 40 nm chromium adhesion layer and a 200 nm gold layer were sequentially deposited using e-beam evaporation. The lift-off process was carried out in acetone with sonication to remove the unwanted metal and photoresist, leaving the serpentine electrode patterned on the polyimide film.

Glucose monitoring/regulation patch preparation

A flexible circuit board was fabricated using a polyimide substrate to serve as the base material. The fabrication process began with the application of photolithography and e-beam evaporation to define and deposit serpentine heating electrodes directly onto the polyimide surface, ensuring precise patterning and adhesion. After forming the electrodes, electronic components and integrated circuits (ICs) were soldered onto the flexible board to complete the circuit. To enhance biocompatibility and provide protective encapsulation, a layer of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was applied over the entire circuit using a molding process, which creates a uniform, conformal coating. Finally, microneedles were carefully embedded and adhered to specific, pre-defined regions of the encapsulated circuit, utilizing the adhesive properties of a hydrogel to secure the microneedles in place.

Characterization and measurements

Scanning electron microscopy was utilized to examine the structure and morphology of the materials (SEM, Zeiss Gemini 300). The output of NFC was evaluated using low-noise voltage/current preamplifiers (Stanford Research Systems Model SR560/570). The μ-LED luminaire’s light intensity was tested with an optical power meter (M100D, Thorlabs). Using a commercial meter, the temperature was measured (HM-TPK20-3AQF/W, HIKVISION). The microneedles’ fluorescence staining photographs were taken with an inversion fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71). The microneedles’ mechanical strength was tested using a texture analyzer (FTC TMS-PRO in the United States). Fourier infrared spectroscopy of glucose-regulated microneedles was measured using an FTIR spectrum (INVENIO, Bruker). Excitation and emission wavelengths of glucose monitoring microneedles were analyzed by a fluorescence spectrometer (Aqualog, Horiba). The absorption wavelength of the material was measured by a UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-5100, Metash).

Evaluation of drug delivery efficacy in mice

The conjugation was performed by first dissolving Cy3-NHS ester (1 mg) in anhydrous DMSO (100 μL), followed by the addition to metformin solution (10 mg in 1 mL PBS, pH 8.5) at 1:1–1:2 molar ratio (Cy3: metformin). After a 2-h reaction at 300 rpm (25 °C, light-protected), the conjugate was purified via a desalting column to remove free Cy3. Metformin was subsequently added to the hydrogel solution to achieve a final concentration of 4 wt%. A double-layer microneedle structure was then fabricated using the previously described method. We evaluated transdermal drug delivery in Balb/c mice (n = 6) by comparing microneedle versus the method without microneedles of Cy3-labeled metformin. Following dorsal hair removal, experimental mice received 5 mg drug-loaded microneedle arrays while controls were treated with an equivalent dose of drug solution. Both groups underwent simultaneous heat-activated release (37 °C). Skin samples collected at 0.5, 1, and 2 h post-treatment was analyzed by fluorescence imaging and quantified using ImageJ to assess drug penetration depth in dermal and muscle tissues.

Glucose monitoring in Mice

An animal experiment was conducted using 10 mice to compare blood glucose levels with interstitial fluid glucose concentrations under two different conditions: fasting (after 12 h of food deprivation) and postprandial (1 h after free feeding). Blood glucose levels were initially measured using a commercial glucometer with blood samples collected from the tail vein. Twenty minutes later, interstitial fluid glucose concentrations were monitored using a patch sensor applied to the skin. This setup allowed for a direct comparison of glucose measurements obtained from the commercial glucometer and the patch sensor, assessing the correlation between blood and interstitial fluid glucose levels under different physiological states.

Glucose regulation in Mice

Prepare a patch for this experiment which contains a treatment microneedle loaded with 15 mg of metformin. To evaluate the therapeutic effect of a patch on diabetic mice, 20 diabetic model mice were fasted for 8 h and then randomly divided into four groups (n = 5 per group): a blank control (Blank group), a patch therapy group (Therapy group), a positive control group, and a patch control group (Control group). In the blank control group, mice were allowed to freely feed after two fasting blood glucose measurements. In the patch therapy group, mice had two fasting blood glucose measurements taken, were allowed to freely feed, and were fitted with the patch immediately after feeding. The positive control group remained fasting throughout the experiment without any patch application, while the patch control group remained fasting and was fitted with the patch immediately after the second fasting blood glucose measurement. Blood glucose levels for all mice were measured every hour for 12 h using a commercial glucometer to monitor changes in blood glucose levels, allowing for a comparison of blood glucose dynamics and the assessment of the therapeutic effect of the patch among the different groups.

Discussion on the efficacy of metformin via patch microneedles, oral administration, and subcutaneous injection

This study was designed to evaluate the effects of metformin delivered via a patch microneedle (MN), oral administration, and subcutaneous injection. Patches loaded with 15 mg of metformin and metformin solutions (25 mg/mL in ultrapure water and 12.5 mg/mL in normal saline) were prepared. Twelve diabetic model mice were fasted for 8 h and then randomly divided into four equal groups: Control group (No treatment was administered; Oral drug group (Received 15 mg of metformin via oral gavage using the 25 mg/mL solution); Injected drug group (Received 15 mg of metformin via subcutaneous injection using the 12.5 mg/mL solution); MN group (Received metformin delivered via a microneedle patch). Throughout the experiment, the mice had free access to food. Blood glucose levels were monitored continuously for 12 h. After 7 consecutive days of repeated administration, intestinal tissue samples were collected from the Oral drug group and the MN group for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) sectioning and analysis.

Histological analysis of mouse skin

Skin samples were collected from the dorsal region of mice at three different time points: immediately after microneedle application (day 0), one day after application (day 1), and three days after application (day 3). The excised skin tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 h at room temperature. Following fixation, the tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections of 4–5 µm thickness were cut using a microtome, mounted on glass slides, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). The stained sections were then examined under a light microscope to evaluate histological changes and tissue responses over time following microneedle application.

Fluorescence analysis of mouse skin

For the biocompatibility test of microneedles, standard immunofluorescence protocols were followed. Skin samples were collected from the dorsal region of mice that had been treated with microneedles at three different time points: immediately after microneedle application (day 0), one day after application (day 1), and three days after application (day 3). The excised skin tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h and then dehydrated. The dehydrated tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks and sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm using a microtome. For immunofluorescence staining, the paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and treated with protease for antigen retrieval. After antigen retrieval, a blocking solution containing bovine serum albumin was applied to block non-specific binding sites. The sections were then incubated with a mouse anti-CD68 antibody at a dilution of 1:100 for 2 h at room temperature. Following a rinse in distilled water, a rabbit anti-CD206 antibody diluted 1:100 was incubated for another 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the sections were counterstained with DAPI to visualize cell nuclei. The stained sections were then examined under a fluorescence microscope to assess the biocompatibility of the microneedles.

Ethical statement

All diabetic model mice were provided with standard laboratory diets and water ad libitum. The animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions, maintained at 21 ± 2 °C with a 12-h light/12-hour dark cycle. All animal experiments, including the handling, care, and treatment of the mice, were conducted in strict accordance with the Animal Study Guidelines of Sichuan Cancer Hospital (Approval Number: SCCHEC-04-2024-013). Additionally, all procedures were designed and reported following the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 to ensure the welfare and ethical treatment of the animals used in the study.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References

Yang, X. et al. Global trends in burden of type 2 diabetes attributable to physical inactivity across 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1343002 (2024).

Bonnefond, A. et al. Monogenic diabetes. Nat. Rev. Dis. 9, 12 (2023).

Jyotsna, F. et al. Exploring the complex connection between diabetes and cardiovascular disease: analyzing approaches to mitigate cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes. Cureus 15, e43882 (2023).

Skyler, J. S. Diabetes mellitus: pathogenesis and treatment strategies. J. Med. Chem. 47, 4113–4117 (2004).

Nauck, M. A., Wefers, J. & Meier, J. J. Treatment of type 2 diabetes: challenges, hopes, and anticipated successes. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 9, 525–544 (2021).

Mosaku, K. et al. Depression, anxiety and quality of life among diabetic patients: a comparative study. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 100, 73–78 (2008).

Chen, X. et al. Preparation, properties and challenges of the microneedles-based insulin delivery system. J. Control. Release 288, 173–188 (2018).

Yang, G. et al. A self-powered closed-loop brain-machine-interface system for real-time detecting and rapidly adjusting blood glucose concentration. Nano Energy 93, 106817 (2021).

Shen, D. et al. Electrostatic-interaction-aided microneedle patch for enhanced glucose-responsive insulin delivery and three-meal-per-day blood-glucose regulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 4449–4461 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. “Smart” matrix microneedle patch made of self-cross linkable and multifunctional polymers for delivering insulin on-demand. Adv. Sci. 10, 2303665 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Glucose-responsive microneedle patch for closed-loop dual-hormone delivery in mice and pigs. Sci. Adv. 8, eadd3197 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. Integrated electronic/fluidic microneedle system for glucose sensing and insulin delivery. Theranostics 14, 1662–1682 (2024).

Liu, Y., Yang, L. & Cui, Y. A wearable, rapidly manufacturable, stability-enhancing microneedle patch for closed-loop diabetes management. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 112 (2024).

Li, X. et al. A fully integrated closed-loop system based on mesoporous microneedles-iontophoresis for diabetes treatment. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100827 (2021).

Turner, R. et al. A biocompatible enzyme electrode for continuous in vivo glucose monitoring in whole blood. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 1, 561–564 (1990).

Kenausis, G., Chen, Q. & Heller, A. Electrochemical glucose and lactate sensors based on “wired” thermostable soybean peroxidase operating continuously and stably at 37 °C. Anal. Chem. 69, 1054–1060 (1997).

Hu, Y. et al. A wearable microneedle patch incorporating reversible FRET-based hydrogel sensors for continuous glucose monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 262, 116542 (2024).

Russell, R. et al. A fluorescence-based glucose biosensor using concanavalin and dextran encapsulated in a poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogel. Anal. Chem. 71, 3126–3132 (1999).

Shibata, H. et al. Injectable hydrogel microbeads for fluorescence-based in vivo continuous glucose monitoring. PNAS 107, 17894–17898 (2010).

Invernale, M. et al. Microneedle electrodes toward an amperometric glucose-sensing smart patch. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 3, 338–342 (2014).

Mirzajani, H. et al. An ultra-compact and wireless tag for battery-free sweat glucose monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 213, 114450 (2022).

Abbasiasl, T. et al. A wearable touch-activated device integrated with hollow microneedles for continuous sampling and sensing of dermal interstitial fluid. Adv. Mater. 36, 2304704 (2024).

You, X. et al. Multi-groove microneedles based wearable colorimetric sensor for simple and facile glucose detection. Microchem. J. 190, 108570 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Bioresponsive microneedles with a sheath structure for H2O2 and pH cascade-triggered insulin delivery. Small 14, 1704181 (2018).

Dervisevic, M. et al. Transdermal electrochemical monitoring of glucose via high-density Silicon microneedle array patch. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2009850 (2022).

Pu, Z. et al. A thermal activated and differential self-calibrated flexible epidermal biomicrofluidic device for wearable accurate blood glucose monitoring. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd0199 (2021).

Ribet, F., Stemme, G. & Roxhed, N. Minimally invasive and continuous glucose monitoring sensor based on non-enzymatic porous platinum black-coated gold microneedles. Biomed. Microdevices 20, 137691 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Continuous monitoring of diabetes with an integrated microneedle biosensing device through 3D printing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 75 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Development of smartphone-controlled and microneedle-based wearable continuous glucose monitoring system for home-care diabetes management. ACS Sens 8, 1241–1251 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. A wearable, minimally-invasive, fully electrochemically-controlled feedback minisystem for diabetes management. Lab Chip 23, 421–436 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. An integrated wearable differential microneedle array for continuous glucose monitoring in interstitial fluids. Biosens. Bioelectron. 256, 116280 (2024).

Fang, H., Kaur, G. & Wang, B. Progress in boronic acid-based fluorescent glucose sensors. J. Fluoresc. 14, 481–489 (2004).

Heo, Y. et al. Long-term in vivo glucose monitoring using fluorescent hydrogel fibers. PNAS 108, 13399–13403 (2011).

Xiao, Y., Sung, H. & Du, J. 2017. Sugar-breathing glycopolymersomes for regulating glucose level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7640–7647 (2017).

GhavamiNejad, A. et al. Glucose regulation by modified boronic acid-sulfobetaine zwitterionic nanogels-a non-hormonal strategy for the potential treatment of hyperglycemia. Nanoscale 11, 10167–10171 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Glucose-responsive systems: glucose-responsive insulin and delivery systems: innovation and translation. Adv. Mater. 32, e1902004 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Assisted 3D printing of microneedle patches for minimally invasive glucose control in diabetes. Mater. Sci. Eng. C.Mater. Biol. Appl. 117, 111299 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Cross-linking-density-changeable microneedle patch prepared from a glucose-responsive hydrogel for insulin delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 4870–4882 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Glucose-responsive insulin patch for the regulation of blood glucose in mice and minipigs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 499–506 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Dual self-regulated delivery of insulin and glucagon by a hybrid patch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29512–29517 (2020).

Heifler, O. et al. Clinic-on-a-needle array toward future minimally invasive wearable artificial pancreas applications. ACS Nano 15, 12019–12033 (2021).

Valdastri, P. et al. Wireless implantable electronic platform for chronic fluorescent-based biosensors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 58, 1846–1854 (2011).

Tokuda, T. et al. CMOS image sensor-based implantable glucose sensor using glucose-responsive fluorescent hydrogel. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 3859–3870 (2014).

Yoon, J. & Czarnik, A. Fluorescent chemosensors of carbohydrates. A means of chemically communicating the binding of polyols in water based on chelation-enhanced quenching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 5874–5875 (1992).

Springsteen, G. & Wang, B. A detailed examination of boronic acid–diol complexation. Tetrahedron 58, 5291–5300 (2002).

James, T., Sandanayake, K. & Shinkai, S. Saccharidnachweis mit rezeptoren auf boronsäurebasis. S. Chen. Commun. 477, 2038–2050 (1996).

Franzen, S., Ni, W. & Wang, B. Study of the mechanism of electron-transfer quenching by boron-nitrogen adducts in fluorescent sensors. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107, 12942–12948 (2003).

Boyne, M. S. et al. Timing of changes in interstitial and venous blood glucose measured with a continuous subcutaneous glucose sensor. Diabetes 52, 2790–2794 (2003).

Cengiz, E. et al. A tale of two compartments: interstitial versus blood glucose monitoring. Diab. Technol. Ther. 11, S11–S16 (2009).

Shu, W. et al. Insights into the mechanics of solid conical microneedle array insertion into skin using the finite element method. Acta Biomater. 135, 403–413 (2021).

Sang, M. et al. Fluorescent-based biodegradable microneedle sensor array for tether-free continuous glucose monitoring with smartphone application. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh1765 (2024).

Keyvani, F. et al. Integrated electrochemical aptamer biosensing and colorimetric pH monitoring via hydrogel microneedle assays for assessing antibiotic treatment. Adv. Sci. 11, 2309027 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11674048), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC0143 and 2024YFFK0333), and Precision Radiation in Oncology Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province Open Fund (2024ROKF06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: R.L., Z.J., Y.C., L.X., Z.L., X.X., and M.C. Methodology: R.L., Z.J., Z.L., X.X., and M.C. Investigation: R.L., Y.C., L.X., X.X., and M.C. Visualization: R.L., Z.J., Y.C., Z.L., and X.X. Funding acquisition: Z.L., X.X., and M.C. Project administration: L.X., Z.L., X.X., and M.C. Supervision: L.X., X.X., and M.C. Writing—original draft: R.L. Writing—review & editing: R.L., Z.J., L.X., Z.L., X.X., and M.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval and informed consent were obtained from all participants and the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Research and New Medical Technology of Sichuan Cancer Hospital (SCCHEC-04-2024-013).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, R., Jiang, Z., Chi, Y. et al. A flexible wireless skin patch for synchronized glucose monitoring and regulation. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 23 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01138-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01138-4